1. Introduction

Waste management is one of the key frontiers of environmental protection aimed at stopping climate change [

1,

2,

3]. To address the way waste should be managed and reused, the European Union (EU) passed the Waste Framework Directive in 2011 and amended it in 2019. Based on the European Environment Agency data [

4] as of 2021, approximately 49% of municipal waste and up to 64% of packaging is recycled. Germany is the leader in terms of recycling trend in Europe, with 70% of municipal waste recycled, and Austria follows just behind, while Romania is in the last place among EU countries with a municipal recycling rate of just 12% [

4]. However, taking a broader global perspective, around 2.01 billion tonnes of waste is produced annually, yet only around 33% is recycled [

5]. Although the United States is a big contributor to plastic waste generation, it also recycles quite a lot, and thus, it is not the leader of mismanaged plastic waste. In other continents, as of 2019, Venezuela and Uruguay in South America, Zimbabwe and Tanzania in Africa, and Malaysia and the Philippines in Asia did not properly recycle plastic [

6]. As of 2019, less than 10% of plastic waste was recycled there [

6]; when looking at newer statistics—OECD Global Plastics Outlook 2022 [

7]—the data shows no change in plastic reuse.

Recycling of waste provides several benefits, not only environmental but also economic. From an economic viewpoint, the reuse of waste can improve the allocation of market-scarce resources and diminish the effect of overconsumption. Overconsumption can fuel overproduction, and even if it does, the use of recycled matter can help to lower the use of scarce materials. Moreover, recycling can help address aesthetic concerns, as illegal dumps and legal landfills—while the latter adhere to strict environmental protocols—remain environmentally hazardous and visually unappealing, especially in tourist areas [

8,

9]. Apart from these advantages, there are also costs that must be borne mainly by the public. The above-mentioned benefits are actively facilitated through infrastructure, particularly the Recycling/Civic Amenity Sites (CASs)—which form a part of a broader initiative to promote the circular economy, where waste is minimised, and materials are reused or recycled as efficiently as possible [

10,

11]. These centralised, staffed facilities accept broader waste streams (fractions) excluded from regular doorstep collection—such as bulky items (e.g., furniture, mattresses, appliances—both electrical and non-electrical), hazardous waste (e.g., batteries [

12], paints, pesticides, e-waste [

13]), recyclable items (e.g., plastics [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], scrap metal, glass, wood [

19]), specialty materials (e.g., tyres [

20], construction and demolition [

21,

22], textiles [

23,

24]), and biodegradable waste (e.g., kitchen [

25], green [

26]). They are usually strategically located for resident accessibility and operate under strict guidelines for the collection and sorting of primarily recyclable materials. Many also run educational initiatives to inform the public about best recycling practices and waste reduction [

27,

28].

Within Poland’s municipal recycling and waste management system, the CAS-subsystem is classified as essential technical infrastructure, designated exclusively for collecting household segregated waste—both non-hazardous and hazardous. These facilities can be managed by either governmental or private entities, complying with EU and national recycling and waste management regulations and standards, ensuring that collected materials are processed in an environmentally friendly manner. Polish residents can transfer municipal waste to the CASs free of charge. However, for regular doorstep collection of municipal waste from households and property owners—or for the direct collection and treatment of commercial/special waste from businesses and institutions—each municipality implements additional solutions financed through residential waste fees (for household waste) and contractual waste charges (for business/institutional waste), respectively. The doorstep collection remains a mandatory household service for standard waste streams, while commercial waste requires separate contracts. Though doorstep and commercial aspects fall outside the scope of the CAS subsystem, they remain an integral element of the entire waste management system operating at the municipal level in Poland.

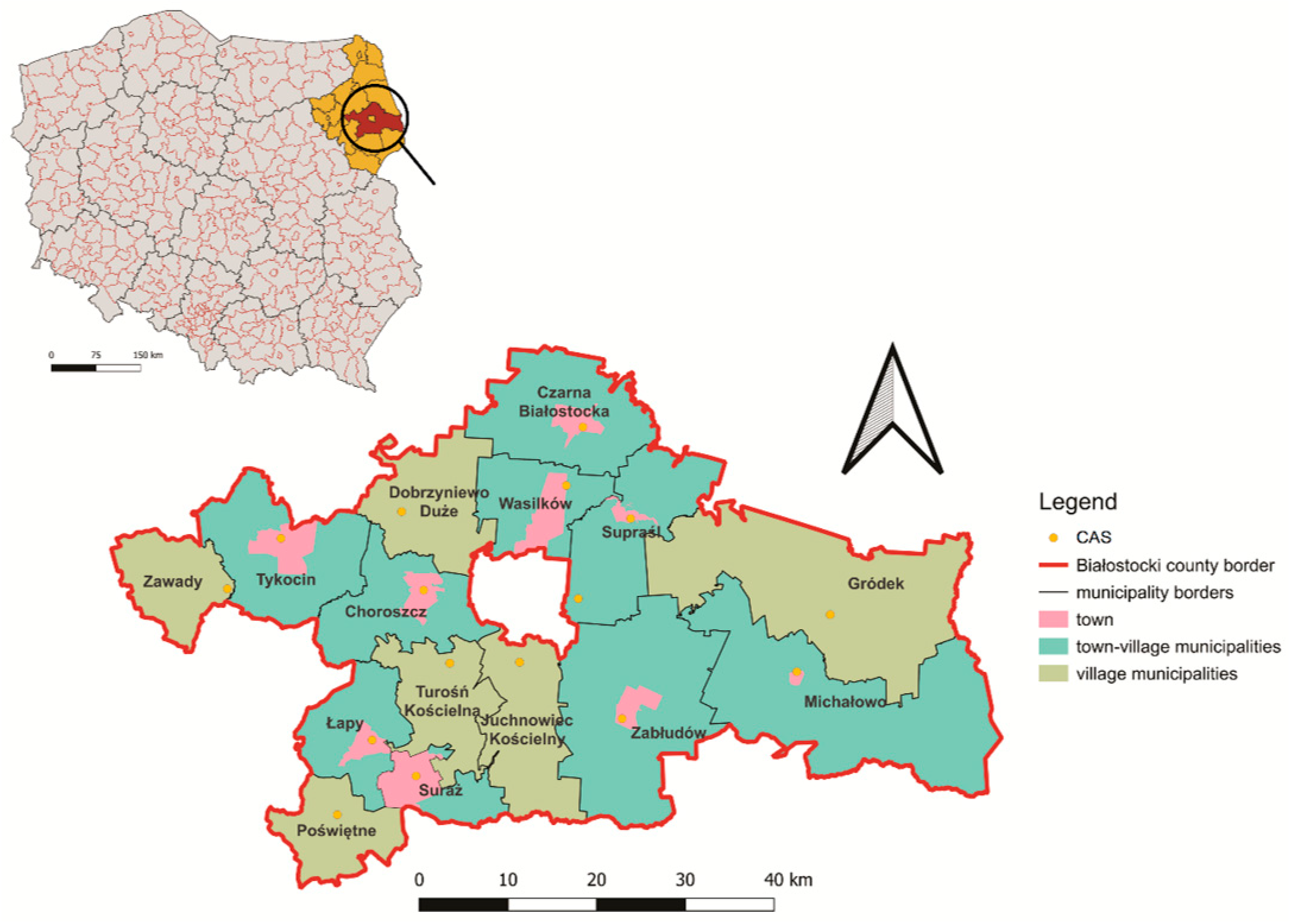

While CAS functions (what they are supposed to do) are clearly defined in Polish regulatory frameworks, their operational effectiveness, particularly during systemic transitions and within specific regional contexts, remains an underexplored area of empirical research, creating a significant knowledge gap. This case study focuses on one county in Poland—Białostocki county—and the CASs located within its municipalities. The primary objective was to determine the operational effectiveness of all facilities managed solely by the public administration units (the Municipal Offices) during the 2014–2018 transition period—a phase defined by regulatory overhaul and operational disruptions.

Although this study primarily evaluates the operational effectiveness of CASs, its findings provide critical insights into the broader sustainability of predominantly rural waste management systems. A multi-criteria assessment was employed, integrating compliance audits, infrastructure checks, and spatial analysis of waste type distributions (using a coded classification system) across local municipalities to evaluate CAS operations within this transitional context. This integrated approach directly connects socio-economic drivers (municipality profiles), material flows (waste composition patterns), and technical infrastructure to assess the operational viability of each facility. Consequently, the methodology provides a replicable framework for pinpointing the root causes of inefficient CAS operations.

The practical significance of these findings is twofold: they enable estimating the effectiveness of CASs during systemic transition while providing a diagnostic framework for sustainable policy and planning. By identifying operational weaknesses in the resident waste transfer process and creating a blueprint for efficient management based on retrospective analysis, this study offers evidence-based strategies to enhance the long-term environmental and economic sustainability of predominantly rural waste management. The developed tools enable local authorities to gauge the demand for CAS services and optimise the operational design of individual facilities, ensuring infrastructure investments directly support overarching sustainability goals.

3. Results

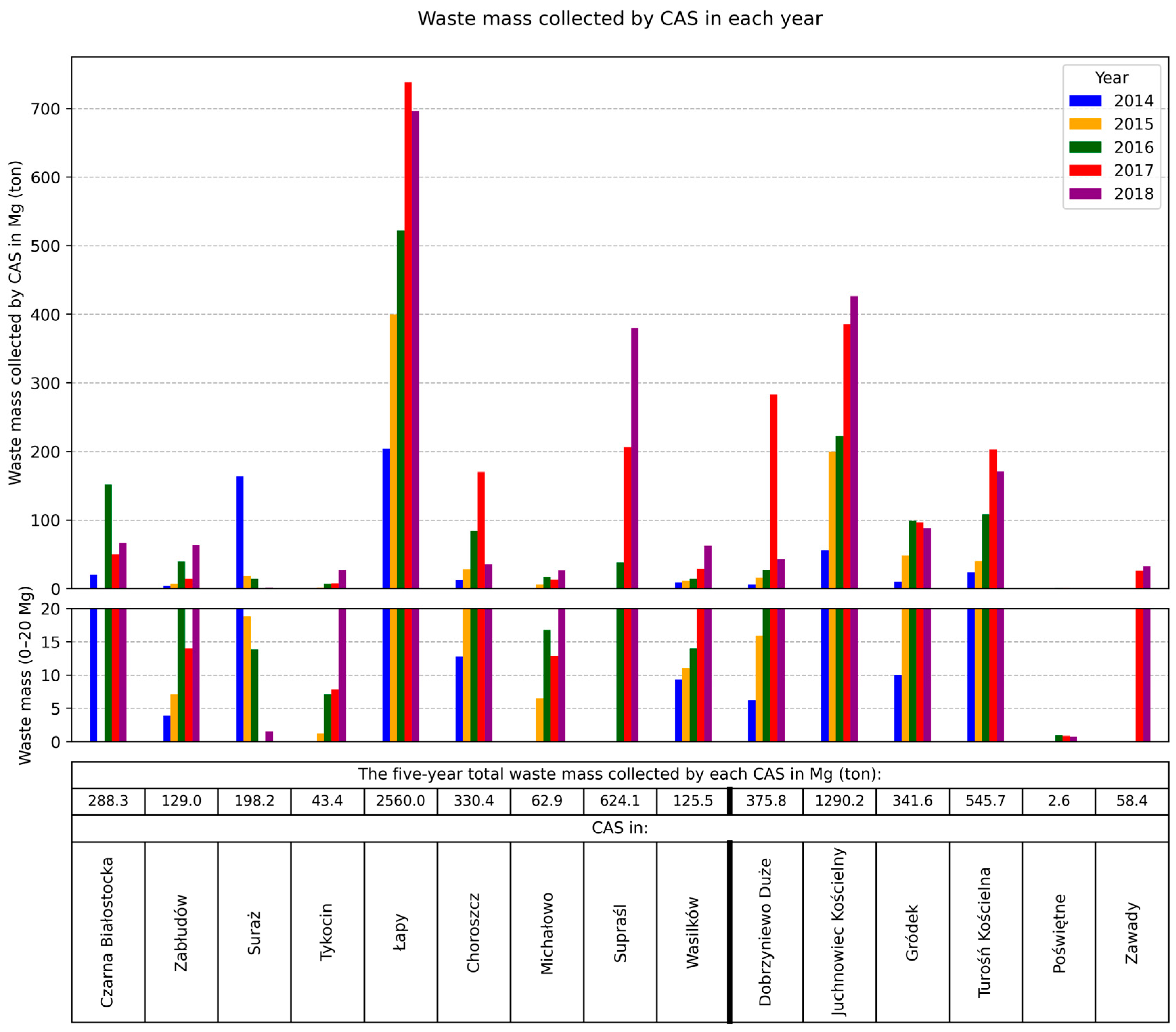

Figure 2 presents two complementary datasets for each CAS facility across municipalities: the annual waste mass totals (2014–2018), revealing yearly distribution patterns, and the 5-year waste mass totals (summary values per CAS facility). Both were calculated using 35 distinct, verified waste codes (

Figure 3), with one exception—Supraśl Municipality—where two CASs were aggregated into a single analytical unit.

Based on

Figure 3, the grouping and counting of the waste codes are as follows: sub-chapter (sub-group) 20 01 contains 18 codes, 20 02 contains 2 codes, 20 03 contains 1 code, 15 01 contains 6 codes, 16 01 contains 1 code, 17 01 contains 3 codes, 17 02 contains 1 code, 17 04 contains 2 codes, and 17 09 contains 1 code, resulting in a total of 35 distinct codes.

Figure 4 details the waste mass quantities (presented in

Figure 2) by the verified waste codes (

Figure 3) across two municipality administrative types, highlighting the dominant waste codes.

The resulting 5-year cumulative waste mass, derived from

Figure 2 and

Figure 4, collected by CAS facilities was: 4361.78 Mg (1 Mg = 1 metric ton) in nine town-and-village municipalities and 2614.25 Mg in six village municipalities.

The waste composition patterns—reflected in mass distribution per individual waste code (

Figure 4)—differed significantly between the town–village and village municipalities. This study documented 35 distinct waste codes across both types, with a markedly uneven distribution. The town-and-village municipalities dominated in the specific waste type 17 01 01 (2365.4 Mg vs. 377.1 Mg) and were the primary collectors for 16 01 03 (287.9 Mg vs. 58.6 Mg). Conversely, the village municipalities dominated in 17 09 04 (683.3 Mg vs. 250.0 Mg) and 17 01 07 (607.8 Mg vs. 195.0 Mg). The quantities were comparable for 20 03 07 (town-and-village: 615.2 Mg; village: 509.6 Mg) and 20 02 01 (town-and-village: 190.1 Mg; village: 190.5 Mg).

Notably, multiple waste types were exclusive to one municipality type. A waste code was classified as exclusive to one municipality type if its recorded mass was greater than zero in one type and exactly zero in the other. The following were found solely in the town-and-village municipalities (listed in descending order of mass): 17 01 02, 15 01 04, 17 04 05, 20 01 08, 15 01 10, 17 04 02, 20 01 34, and 20 01 33. Conversely, the following were only present in the village municipalities: 17 02 01, 20 01 01, 20 01 11, 20 01 21, 20 01 26, 20 01 27, and 20 01 40.

Additionally, multiple minimal-quantity waste types were present in one or both municipality types (e.g., 20 01 02, 20 01 10, 20 01 23, 20 01 28, 20 01 32, and 20 01 39). A minimum operational threshold was deliberately not specified to provide a complete inventory of all waste types. Consequently, the management approach for these minimal wastes differs fundamentally by hazardous status.

While non-hazardous waste in minimal quantities is typically excluded from infrastructure planning, its active monitoring is essential to identify emerging trends—such as rapid growth or high recycling/recovery potential—in alignment with mandated EU and national recycling targets. In contrast, hazardous waste in minimal quantities must be tracked rigorously regardless of mass due to its regulatory significance. Seven hazardous waste codes were documented: 20 01 35, 20 01 23, 15 01 10, and 20 01 33 (town-and-village); and 20 01 21, 20 01 26, and 20 01 27 (village).

Following standard legal and operational principles, management priority is typically assigned for non-hazardous waste types exceeding a minimum practical threshold, particularly those that are rapidly growing and/or possess high recycling or recovery potential. The Discussion section provides a detailed analysis of this potential, using our proposed distinctive and straightforward criteria for the years 2014–2018.

At individual CAS facilities, service scale (represented by household count served) drove both the annual and the 5-year waste mass (2014–2018;

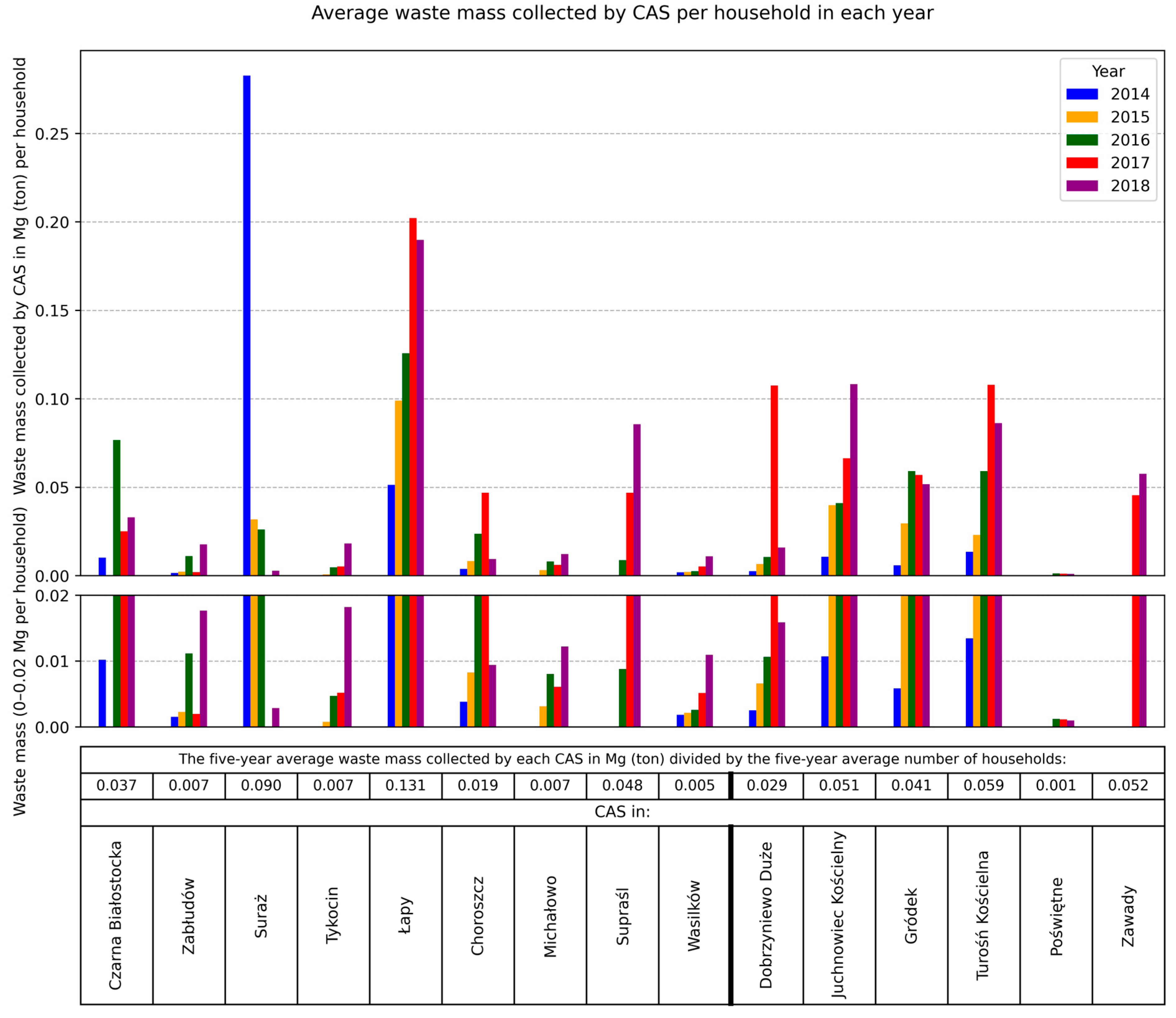

Figure 2), and the 5-year average waste mass. Furthermore,

Figure 5 presents two complementary datasets for each CAS facility across municipalities: the annual waste mass per household served (2014–2018), revealing yearly distribution patterns, and the 5-year OEI values (summary efficiency metrics). Using these facility-level 5-year OEI values (

Figure 5), operational efficiency was compared across two municipality types: the town-and-village and the village municipalities.

For the town-and-village municipalities, the calculated 5-year OEI values were as follows: 0.037, 0.007, 0.090, 0.007, 0.131, 0.019, 0.007, 0.048, and 0.005 Mg/household (

Figure 5). The μ = 0.351/9 = 0.0390 Mg/household, the σ ≈ 0.0419 Mg/household, and the corresponding OEI thresholds were as follows:

- –

Low: μ − σ = 0.0390 − 0.0419 = −0.0029 ≈ 0.00 Mg/household (alarmingly low value);

- –

High: μ + σ = 0.0390 + 0.0419 = 0.0809 Mg/household (exemplary high value).

Thus, the interpretation of the CAS thresholds in the town-and-village municipalities is as seen below:

- –

Low efficiency (≤0.00 t/household): Values ≤ 0 are impossible—in practice, the low threshold implies values close to zero (e.g., ≤0.01 Mg/household). This indicates very poor CAS utilisation (residents do not deliver waste, and CAS requires intervention). Such facilities are prioritised for optimisation because of ineffective collection.

Examples: Municipalities with values of 0.007 (Zabłudów, Tykocin, Michałowo) and 0.005 (Wasilków), as evident in

Figure 5, are based on the annual waste mass per household served collected at an individual CAS.

- –

High efficiency (≥0.0809 Mg/household): CAS is intensively used (residents actively deliver waste). Such facilities are identified as a best-practice model.

Examples: Municipalities have values of 0.090 (Suraż) and 0.131 (Łapy), as shown in

Figure 5.

- –

Medium efficiency corresponds to municipalities with values of 0.037 (Czarna Białostocka), 0.019 (Choroszcz), and 0.048 (Supraśl), as in

Figure 5.

For the village municipalities, the calculated 5-year OEI values were as follows: 0.029, 0.051, 0.041, 0.059, 0.001, 0.052 Mg/household (

Figure 5). The μ = 0.233/6 = 0.0388 Mg/household, the σ ≈ 0.0194 Mg/household, and the corresponding OEI thresholds were as follows:

- –

Low: μ − σ = 0.0388 − 0.0194 = 0.0198 Mg/household;

- –

High: μ + σ = 0.0388 + 0.0194 = 0.0582 Mg/household.

Thus, the interpretation of the CAS thresholds in the village municipalities is as seen below:

- –

Low efficiency (≤0.0198 Mg/household): Values ≤ 0.0198 indicate very poor CAS utilisation (suggesting both inadequate waste delivery to CAS and mandatory CAS intervention).

Examples: The municipality with a value of 0.001 (Poświętne), as evident in

Figure 5, is based on the annual waste mass per household served, collected at an individual CAS.

- –

High efficiency (≥0.0582 Mg/household): CAS has exemplary efficiency (which indicates active resident participation).

Examples: The municipality has a value of 0.059 (Turośń Kościelna), as shown in

Figure 5.

- –

Medium efficiency corresponds to municipalities with values of 0.029 (Dobrzyniewo Duże), 0.051 (Juchnowiec Kościelny), 0.041 (Gródek), and 0.052 (Zawady), as in

Figure 5.

To ensure full integration with the above results, the following anomalies and temporal accessibility schedules across municipalities were documented. CAS anomalies are as follows: Czarna Białostocka—CAS temporarily closed in 2015 (renovation); Suraż—CAS temporarily closed in 2017 (renovation); Tykocin—no CAS in 2014, with one stationary CAS operational from 2015; Michałowo—CAS operational in 2014 but zero waste collected; Supraśl—no CAS during 2014–2015 (mobile substitution services), with two stationary CASs operational from 2016; Poświętne—no CAS during 2014–2015 (mobile substitution services), with one stationary CAS operational from 2016; and Zawady—no CAS during 2014–2016, with one stationary CAS operational from 2017. Household count served anomalies are as follows: Zawady—no data for 2016. Temporal accessibility schedules (days and opening hours to residents, excl. statutory non-working days) are as follows: Czarna Białostocka (3 days/week: Mon 10–18, Wed and Sat 8–16); Zabłudów (2 days/week: Tue and Sat 10–16); Suraż (1 day/week: Wed 9–17, low-population justified); Tykocin (1 day/week: Tue 8–15 + 1st Sat/month 8–15); Łapy (5 days/week: Tue-Sat 7–15); Choroszcz (1 day/week: Sat 8–12); Michałowo (5 days/week: Mon-Fri 8–16); Supraśl (two sites, both 1 day/week: Sat 8–14); Wasilków (5 days/week: Mon-Fri 7–16 + Sat 7–14); Dobrzyniewo Duże (1 days/week: Sat 8–14); Juchnowiec Kościelny (5 days/week: Mon, Wed-Fri 8–16, Sat 7–14.30); Gródek (2 days/week: Tue 7–15, Thu 9–17); Turośń Kościelna (1 day/week: Sat 7–13); Poświętne (1 day/week: Thu 6–14 + 1st Sat/month 8–10); and Zawady (≥1 week/month: Mon-Fri 7:30–15:30).

The assessment of operational infrastructure across all county CASs, conducted via a direct stock-take of ten key technical infrastructure indicators, revealed significant disparities in both equipment and service levels, resulting in a clear ranking (

Table 1). Choroszcz achieved the highest score (first place, 8/11 pts), while Wasilków ranked the lowest (fifth place, 4/11 pts). A significant majority of CASs (13 of the 16 physical sites) scored in the mid-range (6–7 pts), indicating a common basic operational capacity but also a consistent gap to full infrastructural adequacy (maximum score).

A comparative analysis of basic infrastructural gaps in the mid-score range (excluding the universally absent crusher (h) and sorting line (i)) revealed key differences between municipality administrative types. Among the town-and-village CASs, the most frequently missing element was the weighing device (e), absent in five CASs (all except Supraśl). The displayed regulations (a) were also missing in four CASs (Supraśl, Czarna Białostocka, and Tykocin). A key positive finding was the consistent presence of core physical infrastructure (c, d, f, g) and service level compliance (j), with Michałowo as the sole exception due to its lack of an aggregate-construction waste area (g). Crucially, these CASs were limited primarily by the absence of a management element (e), and secondarily by missing operational control elements, notably regulations (a) and, in Suraż, a security camera system (b).

Among the village CASs, the weighing device (e) was also the most common gap, absent in all five CASs. The CASs achieving a total of 7 pts lacked only this management element (e), possessing all other operational control, core physical infrastructure, and service level elements (a–d, f, g, j). Those scoring 6 pts had further deficiencies: both Poświętne and Turośń Kościelna lacked (e), with Turośń Kościelna also lacking (a) and Poświętne lacking (b). Crucially, all village CASs maintained a full set of core physical infrastructure (c, d, f, g) and service level compliance (j).

4. Discussion

The complementary structuring of the same waste data, presented in the

Supplementary Materials, reveals a clear path for waste management policy of CASs. The overview from

Figure S2 is essential for strategic prioritisation at the regional (county) level, identifying which waste codes have the largest mass and thus the greatest potential impact for recycling or recovery initiatives. Subsequently, the detailed view in

Figure S1 enables targeted action at the local (municipality) level by pinpointing the specific municipalities that are the primary sources of these strategic waste streams. This facilitates differentiated policies at the municipal level, such as organising tailored collection systems or conducting focused inspections in the municipalities that contribute most significantly to the county’s overall waste challenge.

4.1. Forecasting Waste Recycling/Recovery Potential at CASs Under National Policy: An Analysis of Socio-Economic Drivers in Białostocki County

The distinct waste code patterns observed between the town-and-village and the village municipalities at the CASs in Białostocki county (

Figure 4) necessitate tailored infrastructure strategies. This becomes evident when evaluating the CAS-collected waste against Poland’s overarching recycling policy benchmarks [

46]. Although the policy provides a comprehensive framework for a municipality’s total waste, our analysis applies its metrics specifically to the subset collected by CASs. This focused approach allows for the isolation of the recycling/recovery potential inherent to the CAS subsystem from the overall outcome of the entire municipality’s integrated system.

Our analysis of the 35 documented waste codes is structured around the policy’s two primary categories for mandatory, maximum recycling and recovery targets (2014–2018). First, waste codes that count toward the recycling and preparation for re-use target (14% in 2014, rising to 30% in 2018) include ten codes identified in our results (15 01 01, 15 01 02, 15 01 04, 15 01 06, 15 01 07, 20 01 01, 20 01 02, 20 01 39, 20 01 40, and 20 01 99). Under Section 3(1) of that regulation [

46], these codes are applied to calculate the mandatory rate for paper, metals, plastics, and glass. The regulation stipulates that for code 15 01 06, only components consisting of paper, metal, plastic, glass, and multi-material packaging are eligible, while for code 20 01 99, only paper, metal, plastic, and glass components are accounted for. For example (

Figure 4), the prevalence of codes (in descending mass order) 15 01 04, 15 01 01, 15 01 07, 15 01 02, and 15 01 06, and a small share of code 20 01 02 in the town-and-village municipalities, is directly relevant for this target, as these codes represent readily recyclable materials from more concentrated sources. Conversely, the prevalence of codes 20 01 99, 20 01 39, 20 01 01 and 20 01 40 in the village municipalities also contributes significantly to the target. However, achieving it is more complex. Despite being segregated, their commingle composition (diverse in content) and often low-value material composition necessitate reliance on energy recovery rather than high-value recycling for a substantial portion of the material.

Second, waste codes that count toward the recycling, preparation for re-use, and other recovery target (38% in 2014, rising to 50% in 2018) comprise seven codes identified in our results (17 01 01, 17 01 02, 17 01 07, 17 02 01, 17 04 02, 17 04 05, and 17 09 04). These codes are applied under Section 3(3) of that regulation [

46] for calculating the mandatory rate for non-hazardous construction and demolition waste. For example (

Figure 4), the dominance of code 17 01 01 in the town-and-village municipalities is highly conducive to achieving this target. However, the dominance of codes 17 09 04 and 17 01 07 in the village municipalities, while equally important from a regulatory standpoint, nonetheless complicates target achievement, as it necessitates reliance on energy recovery rather than high-value recycling.

The remaining 18 codes (e.g., other codes of the type 20 01 XX—where ‘XX’ denotes variable digits specifying the waste type within the 20 01 subgroup—along with 15 01 10, 16 01 03; details can be found in

Figure 4) fall outside these mandatory mass-based targets. They were not a primary focus of the national 2014–2018 targets, so their management follows other waste hierarchy principles and depends on local infrastructure capabilities, though they may still hold inherent recycling value.

While non-hazardous waste in minimal quantities is typically excluded from infrastructure planning, it requires active monitoring to identify emerging trends, such as rapid growth (a significant year-over-year (YoY) increase) or the presence of strategic materials. This includes high recycling value materials (e.g., paper/paperboard, metals, plastics, and glass) subject to the 2014–2018 recycling and preparation for re-use mandate, as well as moderately valuable recycling materials (e.g., non-hazardous construction and demolition waste), subject to the parallel recovery mandate.

The analysis per individual municipality and municipality type, quantified in

Table 2 and

Table 3, provides concrete evidence of this compositional divide and its impact on recycling/recovery potential. The total five-year mass of waste codes subject to the mandatory targets (Groups 15/20 and 17) collected at CASs in the town-and-village municipalities was more than double that of the village municipalities (~3113 Mg vs. ~1748 Mg). Furthermore, the theoretical recycling mass—calculated by applying the average percentage rates (19.6% and 43%) to the total five-year mass—highlights the scale of the disparity (contrast): town-and-village CASs would need to process ~1299 Mg to meet targets, compared to ~733 Mg for village CASs.

This order-of-magnitude difference underscores the critical role of town-and-village municipalities in achieving regional targets but also reveals the fundamental complexity of the waste composition in village municipalities, where a higher proportion of the mass comprises challenging, commingled materials. This quantitative disparity is a direct result of profound qualitative, socio-economic differences in waste composition, as detailed in the code-specific analysis (

Figure 4,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

This compositional divergence dictates recycling/recovery potential. The town-and-village municipalities, acting as commercial-service hubs, collected larger quantities for most codes in Group 15 (packaging waste) at CASs, sourced from supermarkets, shops, and restaurants, resulting in homogeneous packaging waste loads highly suitable for recycling. This effect is amplified by higher population density, which intensifies consumption and increases packaging waste generation per square kilometre. Conversely, the village municipalities, characterised by agricultural self-sufficiency, deposited more waste from specific Group 20 codes (separately collected, non-packaging waste of a commingled composition). These heterogeneous loads originate from repair work, agriculture, and bulky item disposal. For example, code 20 01 99 acts as a catch-all for difficult-to-sort items like complex commingled waste, bulky items, textiles, soiled plastics and pieces of furniture. Furthermore, codes 20 01 40 (metals) and 20 01 39 (plastics)—comprising various types and grades—often originate from equipment repair and agricultural operations, such as broken tools, wire, fencing, machinery parts, and agricultural plastics (e.g., silage wrap, tunnel sheeting, and fertiliser bags). This results in a commingled waste that presents major sorting challenges. This composition pattern is also mirrored in Group 17 (construction and demolition waste), where the town-and-village municipalities predominantly generate clean, homogeneous loads (e.g., 17 01 01) from large-scale projects, contrasting with the mixed, heterogeneous loads (e.g., 17 09 04) from small-scale agricultural and renovation activities in the village municipalities.

This disparity stems from their fundamental socio-economic differences: the commercial-service character of town-and-village municipalities yields homogeneous, high-recycling-value waste, whereas the agricultural-self-sufficiency of village municipalities results in heterogeneous, challenging-to-recycle waste. The homogeneity of waste significantly facilitates recycling into high-quality secondary outputs with minimal processing, directly supporting mandated recovery targets. Conversely, the complex, commingled composition of the waste from village municipalities presents considerable challenges, necessitating advanced, cost-intensive sorting and pre-processing before recovery.

These distinct waste patterns dictate the need for tailored operational strategies and infrastructure priorities at the CASs in each municipality type. Consequently, our findings argue for moving beyond a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model. For the town-and-village municipalities, policy should leverage high-quality, homogeneous loads (Groups 15 and 17) through investments in efficient processing capacity. For the village municipalities, investments must target advanced sorting capabilities to manage complex, heterogeneous loads (Groups 20 and mixed 17). This diagnostic approach provides a predictive framework for tailoring CAS operations to local socio-economic realities. By aligning infrastructure with the specific waste composition driven by these socio-economic drivers, CASs can more effectively support national recycling targets. The identified relationships between socio-economic profiles and waste composition patterns allow for forecasting recycling/recovery potential in other municipalities with similar CAS characteristics, making this a transferable model for regional policy planning.

4.2. Structurally Differentiated CAS Model Aligned with Municipality Type for Białystok County

The OEI provided a clear measure of waste collection efficiency per household served at individual CAS facilities across both town-and-village and village municipalities (

Figure 5). The poorly operating CAS facilities in Wasilków, Zabłudów, Tykocin, and Michałowo (town-and-village), alongside Poświętne (village), required optimisation to achieve the high-efficiency benchmarks set by Łapy and Turośń Kościelna, respectively. The solutions implemented during the 2014–2018 period should have been based on three optimisation pillars: adjusting opening days/hours, eliminating anomalies, and deploying targeted education in these five municipalities. Łapy demonstrated that a 5-day CAS operation maximised efficiency for the town-and-village municipalities, whereas a maximum 2-day operation ensured cost-effectiveness (rationalising CAS operating costs) for the village municipalities. Education initiatives should have directly targeted municipality-specific systemic issues—such as poor temporal access, geographic coverage gaps, low resident awareness of CAS locations/functions, high CAS maintenance costs, opaque application processes, and either cumbersome paperwork requirements or resistance to digitisation—all of which frustrate residents and reduce CAS utilisation. Critically, these initiatives should have been tailored to each municipality’s size. Wasilków, exhibiting temporal overcapacity, should have optimised operations by reducing Saturday hours to 8–12. Zabłudów and Tykocin, showing low and critical temporal access, respectively, should have progressively expanded to 3 days before reaching 5 days. Michałowo should have maintained existing access levels, while Poświętne should have increased service from critical access (4h/week) to a functional minimum of 2 days (one weekday + Saturday). Crucially, most municipalities should have improved low resident CAS awareness through universal methods: consultation points, targeted leaflets, and SMS reminders. Implementing real-time reporting would have prevented anomalies such as Michałowo’s 2014 zero-waste incident. Complementarily, preventing service disruptions during CAS renovations (as observed in Czarna Białostocka and Suraż) required systemic measures, such as establishing temporary replacement facilities. In Tykocin’s case of temporal access deficit, adaptive infrastructure deployment was essential, and mobile CAS services should have been deployed as transitional infrastructure during the implementation of a 5-day operation to resolve historical service interruptions. In Zabłudów, a temporary mobile CAS should have been implemented to support systemic reorganisation and maintain service continuity during access expansion. Moreover, it can only be theoretically postulated that inadequate organisation of standardised on-site waste handover procedures at CAS receptions may have contributed to reluctance in utilising these services. Potential inconsistencies in service delivery—such as unpredictable waiting times, unclear sorting requirements, or inconsistent staff assistance—could deter compliance. This hypothesis regarding operational gaps in the human interface dimension remains unverified but warrants examination through structured resident surveys.

Summarising, the optimal solution proposed for Białystok county is a structurally differentiated CAS model aligned with municipality type, operating on a fixed weekly schedule with mandatory Saturday coverage, with service days allocated as follows: 5 days (including Saturday) for town-and-village municipalities, and 2 days (including Saturday) for village municipalities—enhanced through more frequent OEI reporting and locally tailored resident education. Its efficiency and cost effectiveness (verified by OEI) derive from adaptive flexibility, replacing rigid uniformity with strategic calibration to local needs and capacities.

4.3. Disparities in Technical Infrastructure Scores and the Mid-Range CAS Cluster in Białystok County

The ranking presented in

Table 1 reveals a clear hierarchy of operational capability among the CASs, characterised primarily by a cluster of mid-range scores (6–7 pts) and a universal lack of advanced processing equipment (crushers and sorting lines), which limits potential revenue generation and improved recycling rates across the county. The widespread absence of the key management element—the weighing device (e)—is a critical operational failure, as it prevents the accurate measurement of inbound waste, the most basic metric for managing and improving any waste transfer operation. This absence was the primary constraint that prevented most CASs from scoring higher.

The analysis reveals two key distinctions: Firstly, the pattern of missing elements shows that while both groups shared a common lack of the management element (e) and operational control elements (a, b), the town-and-village CASs were distinguished by an isolated critical deficiency in their otherwise complete core physical infrastructure (c, d, f, g). This was exemplified by the absence of an aggregate-construction waste area (g) in Michałowo, a significant exception that qualified the group’s overall consistency. Secondly, the score distribution shows that the most striking distinction was the extreme disparity in scores within the town-and-village CASs, which contained both the county’s top performer (Choroszcz, 8 pts) and its most struggling facility (Wasilków, 4 pts). This contrasts sharply with the village CASs, which demonstrated a homogeneous score distribution clustered in a narrower band (5–7 pts) and no deficiencies in core physical infrastructure.

Ultimately, the CAS operational framework (2014–2018) succeeded in establishing basic standards but failed to progress towards efficiency and value-added operations. While the town-and-village group demonstrated relative consistency, it was not immune to critical gaps in core infrastructure, as exemplified by Michałowo. This group embodies a paradox of excellence and profound struggle, necessitating targeted investments to address advanced elements for mid-range facilities and fundamental operational control elements for its lowest performers. The village group, though more consistent, still requires investment to bridge gaps in management elements such as weighing devices. Therefore, the core difference lies not only in the type of deficiencies, but also in the wide disparity between the highest and lowest scores and the unexpected presence of a core infrastructure gap within the town-and-village group.

4.4. Verification of Forecasts, Contemporary Relevance, and Future Implications

The analysis presented in this study, based on data from 2014 to 2018, provides a detailed diagnostic framework and forward-looking projections for optimising CAS operations in Białostocki county. Given the natural evolution of waste management systems and policies over time, it is pertinent to consider the contemporary relevance of these findings, to verify the projections made, and to examine the system’s trajectory in the years since the study period.

4.4.1. Verification of Projections and Model Validation

A critical phase following any prognostic study is the empirical validation of its forecasts against subsequent reality. Our projections were built on identifying persistent systemic drivers: the entrenched socio-economic profiles of municipalities (commercial service versus agricultural self-sufficiency), as well as their tangible manifestations in divergent waste infrastructure, institutional models, and resulting waste stream composition. While the model’s qualitative validity is demonstrated by its robust diagnostic and prescriptive utility (as operationalised in the policy recommendations in

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.5), its quantitative validation through direct comparison with post-2018 outcomes represents the logical next step.

Such longitudinal validation is inherently an applied process, integrated into the operational cycle of the waste management system itself. The detailed municipality-level data that are required are generated by the same infrastructural components (e.g., calibrated weighing devices, digital mass-flow tracking) whose critical deficiencies have already been diagnosed. Consequently, the possibility for precise, empirical verification depends on the implementation of the improvements that this analysis advocates. This creates a cyclical relationship whereby the study’s recommendations enable the future assessment of its own forecasts.

Inference on the current trajectory (2024–2025): In the absence of comprehensive, updated municipal datasets for a formal quantitative test, the system’s likely trajectory can be inferred based on stable drivers and external pressures. The sustained regulatory impetus from the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) [

51,

52] and the European Green Deal (EGD) [

53], combined with the inherent stability of the core socio-economic drivers documented herein, strongly suggests that the structural challenges and inefficiencies we identified remain highly pertinent. Consistent with our diagnosis, broader national and regional reports continue to highlight infrastructural gaps in sorting and data collection as primary bottlenecks to meeting recycling targets. This indicates that progress, if achieved, is likely incremental and heterogeneous, aligning with our projection of a trajectory constrained by systemic, context-sensitive barriers.

Therefore, this study provides both the necessary baseline and the practical means for future validation. The methodological toolkit developed herein—the OEI, infrastructure scoring, and compositional waste analysis—constitutes a definitive instrument for measuring change. The explicit ‘next step’ is the repeated application of this toolkit by municipal authorities using the most recent operational data. This would enable a formal assessment of the following:

- –

The evolution of efficiency gaps between different municipal types;

- –

Progress in remedying the critical infrastructure deficits identified;

- –

Shifts in waste composition in response to evolving socio-economic conditions and policy measures.

Thus, the present analysis establishes the diagnostic benchmark, delivers the analytical metrics, and provides a complete blueprint for ongoing performance tracking and forecast validation. It frames the verification of projections not as a limitation but as an essential, applied continuation of the research, bridging academic modelling with the practical needs of system management and policy adjustment.

4.4.2. Assessing the Current Trajectory and Broader Context

Based on regulatory evolution and the persistence of structural drivers, we can assess the system’s likely trajectory and its alignment with broader sustainability goals. First, in the context of intensified EU regulation, Poland’s implementation of the EU CEAP and the EGD has significantly elevated recycling and sustainability targets since 2018. This heightened regulatory pressure amplifies the relevance of our findings. Specifically, it demonstrates that the infrastructure and operational gaps we identified (e.g., the absence of weighing devices and sorting lines) represent critical bottlenecks not just for compliance, but for achieving these more ambitious national and EU goals. Consequently, our case study offers a detailed, evidence-based example of the on-the-ground challenges that must be overcome to meet overarching directives such as the Waste Framework Directive and the CEAP itself. Second, regarding the persistence of structural drivers, the fundamental socio-economic profiles that drive waste composition divergence remain largely unchanged. Therefore, the core argument for a differentiated, context-sensitive policy approach—a key practical lesson for policymakers—is more pertinent than ever. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ mandate is ill-suited to address the inherent disparities we documented. This lesson extends beyond this county to other regions with similar rural-urban mixes, highlighting the broader applicability of our findings. Third, with respect to the impact of external shocks, it is important to acknowledge that recent global events, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic, may have introduced temporary disruptions to waste generation patterns and collection systems. While such events can cause short-term fluctuations, they do not alter the underlying structural drivers identified in this study. Our analysis provides the essential pre-pandemic baseline required to isolate and evaluate the effects of such shocks in future research, further underscoring the value of our longitudinal framework. Fourthly, regarding the pathway for assessment and improvement, defining ‘improvement’ requires clear metrics. If measured against the structural inefficiencies we diagnosed, progress is likely incremental and uneven. The methodological toolkit developed herein provides municipal authorities with precisely the metrics needed for ongoing self-assessment and priority-setting. Applying this toolkit to the most recent data is the definitive next step for measuring progress, a task for which our study provides the complete blueprint.

4.4.3. The Value of This Baseline and Its Practical Applications

Rather than diminishing its relevance, the time elapsed since 2018 underscores the critical importance of this baseline analysis. Our study provides three key contributions. First, it establishes a diagnostic benchmark against which future changes in CAS efficiency and waste composition can be measured. Second, it offers a transferable methodological toolkit—integrating the OEI, infrastructure scoring, and waste compositional analysis—enabling continuous efficiency evaluation at municipal and regional levels. Third, it delivers practical, evidence-based arguments to support tailored infrastructure investments and community engagement strategies, directly addressing the operational needs of municipal authorities and the strategic objectives of policymakers.

To conclude, this analysis provides the essential basis for understanding and improving waste management in predominantly rural regions. The intensified regulatory landscape confirms that the challenges we identified remain pressing. The optimised, differentiated CAS model we propose offers a practical, scalable pathway forward that aligns with contemporary EU sustainability ambitions. By providing a concrete diagnostic framework, actionable recommendations, and a clear progress-tracking methodology, this study offers a concrete basis for advancing the circular economy in similar socio-economic contexts.

4.5. Policy Implications and Practical Applications

The findings from Białostocki county yield several critical lessons for waste management policy and practice in the Polish context. For central institutions, our study demonstrates that achieving national recycling targets requires moving beyond uniform, ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches towards differentiated policy instruments that recognise the distinct challenges of town-and-village versus village municipalities.

For municipal authorities, the OEIs and infrastructure scoring system developed in this study provide a practical diagnostic toolkit for prioritising investments and optimising service delivery. Specifically, authorities in town-and-village municipalities should focus on leveraging their homogeneous, high-quality waste streams through investments in efficient processing capacity for packaging materials. Conversely, village municipalities require targeted support for advanced sorting capabilities to manage their complex, heterogeneous waste streams, potentially through regional partnerships. Furthermore, the widespread absence of weighing devices represents a critical data gap that undermines effective management; addressing this should be an immediate priority for all municipalities.

At the community level, our findings underscore that resident education must be tailored to local contexts. In village municipalities, education should focus on basic separation techniques, while in town-and-village municipalities, initiatives can shift focus to promoting high-quality recycling of specific material streams.

This case study demonstrates that contextual intelligence—understanding and responding to local socio-economic realities—is as crucial as technological solutions for achieving sustainable waste management in Poland. The optimised CAS model provides a ready-to-implement framework for other predominantly rural regions in the country, demonstrating how evidence-based, differentiated approaches can effectively meet national environmental goals across diverse local contexts.

5. Conclusions

The study results indicate that optimising the CAS network in Białostocki county during a period of frequent legislative changes was the primary challenge for decision-makers (mayors and municipal councils), who were responsible for strategy formulation, fund allocation, technology selection, and regulatory enforcement within the waste management system.

The effectiveness of Poland’s recycling policy is inherently linked to local municipal contexts. This study demonstrates that the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is insufficient. Achieving national targets requires infrastructure investments that are precisely tailored to the specific waste patterns driven by socio-economic profiles of different municipality types: leveraging the high-quality, homogeneous packaging waste from the commercial-service character of town-and-village areas and addressing the complex, heterogeneous waste from the agricultural-self-sufficiency of village areas through advanced sorting and recovery technologies. The role of CASs is pivotal, and their operation must be optimised accordingly using the differentiated model (5-day vs. 2-day operations) validated by the operational efficiency indicator (OEI) to transform this fundamental socio-economic divergence from a challenge into an opportunity for the entire waste management system.

These findings carry significant practical relevance for developing more effective waste management strategies. The optimal CAS solution—integrating municipality-tailored operations (5/2-day scheduling for town-and-village/village municipalities, respectively), continuous monitoring via the OEI, and localised education—provides a replicable framework for other predominantly rural regions. This approach delivers efficiency (confirmed by OEI reporting) through adaptive flexibility, replacing rigid uniformity with needs-based differentiation. Furthermore, the evidence-based ranking of CAS infrastructure—which revealed critical gaps, most notably the widespread absence of weighing devices—offers municipal authorities a clear diagnostic tool for prioritising investments and improving service delivery.

For community engagement and public policy, the study underscores that successful waste management requires contextual intelligence. The documented socio-economic drivers of waste divergence between municipality types highlight the need for tailored education programmes and policy frameworks. Rather than applying uniform regulations, policymakers should develop differentiated instruments that recognise the distinct challenges and opportunities in town-and-village versus village contexts.

The evidence-based ranking of CAS by the operational infrastructure elements confirmed significant disparities in equipment and service levels, with total scores ranging from 4 to 8 out of a maximum of 11 pts. This indicates that while the infrastructure at many CASs was sufficient for basic collection, it lacks the advanced equipment required to optimise their role as efficient and controlled transfer facilities within the broader municipal system. In particular, the absence of a weighing device (e) to quantify incoming waste, a sorting line (i) to segregate materials, and a crusher (h) to reduce volume creates bottlenecks in waste handling and represents a critical missed opportunity to increase value through pre-processing (e.g., sorting or compaction) before waste is sent to final processing facilities. Therefore, strategic investments should focus on technologies that optimise the collection and transfer process, such as weighing devices for data collection and basic sorting lines to reduce contamination before waste is forwarded for final processing.

For future research, several promising directions emerge. Extending the temporal analysis to include post-2018 data would reveal how CAS operations have evolved under Poland’s implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan. Applying the developed assessment methodology to other regions would test its transferability and identify additional contextual factors affecting CAS performance. Furthermore, investigating the role of digital technologies in enhancing CAS operational efficiency and exploring more sophisticated community engagement models would provide valuable insights for advancing sustainable waste management practices.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates that enhancing the sustainability of predominantly rural waste management requires adopting differentiated, evidence-based approaches that align infrastructure and operations with local socio-economic contexts. By moving beyond uniform mandates to strategies that leverage the distinct characteristics of different municipality types, decision-makers can transform socio-economic divergence from a systemic obstacle into a cornerstone of efficient and sustainable waste management, thereby contributing significantly to both national recycling targets and broader environmental sustainability goals.