Abstract

Rapid urbanization has intensified ecological problems such as landscape fragmentation and biodiversity decline, underscoring the need to maintain regional ecological integrity. The construction of ecological security patterns and the optimization of ecological restoration areas are crucial for addressing these ecological issues. However, research on how to couple ecological security patterns with ecological risk assessment to scientifically identify priority areas for ecological restoration and guide spatially targeted restoration remains insufficient. To address this gap, we investigated Liaoning Province by integrating morphological spatial pattern analysis, landscape connectivity assessment, and ecosystem service hotspot analysis to identify ecological sources. We then applied the minimum cumulative resistance model and circuit theory to extract ecological corridors, constructing a comprehensive ecological security pattern. Integrating landscape ecological risk assessment with ecological security patterns established a conservation and restoration-oriented ecological security framework. The results show that the ecological security pattern comprises 40 ecological source patches and 89 potential ecological corridors. Ecological sources encompass a total of 17,628 km2 (approximately 12% of the province), primarily comprising water bodies, grasslands, shrublands, and forests. The ecological corridors span a total of 3533.9 km, with an average length of 39.7 km. We also identified 139 ecological pinch points and 109 ecological barrier points. Integrating these findings with landscape ecological risk zoning delineates ecological restoration zones, revealing a spatial pattern characterized by east–west differentiation and north–south continuity. This ecological conservation and restoration network provides a clear spatial guide and a robust scientific foundation for territorial spatial planning, ecological conservation, and restoration efforts.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, rapid population growth and increasingly intensive economic activities have driven a profound restructuring of land-use patterns worldwide. This restructuring has not only altered land cover but also significantly impacted regional material cycles, energy flows, and the provision of ecosystem services, thereby exerting continuous pressure on achieving sustainable development goals [1,2]. Against this backdrop, balancing economic growth with ecological protection has become a central issue in regional spatial governance and territorial optimization. To address this challenge, identifying key ecological patches and corridors based on ecological processes and constructing an integrated Ecological Security Pattern (ESP) is recognized as a crucial approach to mitigating human–environment spatial conflicts and safeguarding regional ecological security [3,4,5]. This research direction integrates concepts from landscape ecology, geography, and conservation biology, emphasizing the optimization of spatial configurations to enhance ecosystem stability and functional continuity, with both theoretical and practical significance.

The theoretical foundation for constructing Ecological Security Patterns (ESP) is deeply rooted in the “patch–corridor–matrix” concept of landscape ecology, as well as principles from island biogeography and metapopulation theory. Its core premise is that the spatial configuration of ecological patches, together with the structural connectivity of corridors, jointly determines the integrity and functional resilience of ecological networks [6,7]. Currently, ESP construction typically follows a three-step analytical framework: identification of ecological sources, construction of resistance surfaces, and extraction of ecological corridors, to recognize key ecological spaces and maintain their structural connectivity [7,8]. Among these, identifying ecological sources is a fundamental step. Early studies often directly designated land-use types, such as forests or grasslands, as ecological sources [9,10]; although straightforward, this approach fails to capture the multifunctionality of ecosystems comprehensively. With the advancement of ecological theory, researchers have increasingly adopted multi-indicator evaluation systems that integrate ecological sensitivity, ecosystem service supply capacity, and landscape connectivity, providing a more accurate representation of the composite value of ecological processes. This multi-criteria approach has become the current mainstream methodology [11,12,13,14]. However, existing studies often treat individual ecosystem services as independent layers when identifying ecological sources, neglecting their spatial coupling relationships and interaction mechanisms, such as trade-offs between provisioning and regulating services, or the spatial co-occurrence patterns of multiple service hotspots. Such simplifications may lead to an incomplete identification of key ecological areas, thereby affecting the scientific basis of subsequent corridor layouts and the overall effectiveness of the ecological network.

The construction of resistance surfaces aims to quantify the degree to which landscape heterogeneity impedes ecological processes such as species migration, gene flow, and energy exchange. Resistance values are typically assigned based on factors including ecological functional importance, land-use types, and the intensity of human disturbances [14,15]. As research on ESP has deepened, the objectives have gradually expanded from single-species protection or biodiversity maintenance to integrated goals encompassing the coordination of ecosystem services, ecological risk management, and enhancement of territorial spatial resilience, better aligning with the multidimensional demands of regional sustainable development [16,17,18].

Ecological corridors, as key structures connecting isolated ecological sources, play an irreplaceable role in facilitating species migration, maintaining genetic exchange, and enhancing landscape functional continuity [19]. Commonly used methods for corridor identification include the Least-Cost Path (LCP) model, circuit theory, and individual-based movement models. Circuit theory, drawing on concepts from electricity such as current, resistance, and voltage, simulates organism dispersal in heterogeneous landscapes based on random walk principles. Compared with the single optimal path generated by the LCP model, circuit theory can reveal potential multiple migration pathways and their probability distributions, thereby effectively identifying corridor width, ecological bottlenecks, and critical barrier points. This approach has become a prominent method in recent research on ecological security patterns [20].

The ESP represents a spatial configuration designed to maintain ecosystem stability and serves as an essential safeguard for the living environments of species. The optimization and long-term stability of this spatial structure are prerequisites for ensuring the effective functioning of ecosystems. Although an increasing number of studies have focused on constructing ESP, current research seldom incorporates the ecological risks embedded in landscape structures [21]. Consequently, a notable gap remains in methods that integrate landscape ecological risk information into ESP optimization, particularly those aimed at identifying priority conservation and restoration areas. Landscape ecological risk analysis, grounded in landscape pattern metrics, captures the degree to which a landscape mosaic deviates from an optimal configuration and thereby provides a new perspective for addressing this gap. Such analysis emphasizes regional spatiotemporal heterogeneity and scale effects, and it focuses on how specific spatial patterns express risks to ecological functions and processes. Consequently, methods for incorporating landscape ecological risk information into ESP optimization, especially for identifying priority conservation and restoration areas, remain insufficient.

This study aims to present a comprehensive analytical framework for constructing ESP and landscape ecological risk. Specifically, the study includes: (1) quantifying four key ecosystem services: water conservation, soil retention, carbon storage, and habitat quality using the InVEST model; (2) identifying core ecological source areas by combining Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) with ecosystem service hotspots; (3) constructing a multi-factor integrated resistance surface and applying the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model along with circuit theory to extract ecological corridors, while precisely identifying ecological pinch points and barrier points; and (4) coupling landscape ecological risk assessment with ecological security pattern results to propose ecological priority protection zones. This analytical framework provided scientific guidance for the protection, restoration, and strengthening of ecological security patterns in Liaoning Province.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

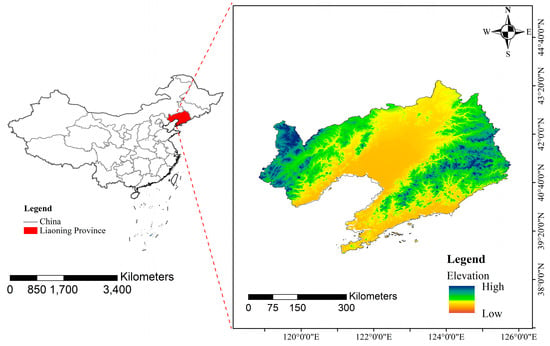

Liaoning Province is located in northeastern China (Figure 1). Its terrain is mainly composed of plains and hills, with gentle coastal tidal wetlands along the shoreline and mountainous and hilly areas inland. The province’s northeast is traversed by the remaining ranges of the Changbai Mountains and the Songhua River system. At the same time, the Liaodong Peninsula and the western Liaoning Plain form the main agricultural zones. As the northernmost coastal province of China, Liaoning occupies a strategically vital position adjacent to the Korean Peninsula and serves as a crucial passage connecting the Beijing–Tianjin region to Northeast Asia. It plays a key role in maintaining China’s national defense, food, ecological, energy, and industrial security, as well as in driving the comprehensive revitalization of the Northeast region.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the Liaoning Province. Data source: Based on administrative boundary data from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center (RESDC); figure drawn by the authors.

However, ecological issues such as land desertification and salinization are prominent in western Liaoning, severely constraining agricultural productivity and ecological quality. Meanwhile, the rapid urban expansion of cities such as Shenyang and Dalian has exerted continuous pressure on surrounding forest, wetland, and grassland ecosystems. Ecological spaces are being increasingly encroached upon, and portions of the original natural ecosystems have been degraded, leading to sharp declines in biodiversity and posing threats to the sustainable development of the region. Therefore, constructing and optimizing the ecological security pattern of Liaoning Province, while identifying potential ecological risks, has become an urgent task. Thus, Liaoning Province is selected as a case study to illustrate the application of the comprehensive analytical framework.

2.2. Data Source and Processing

In this study, we collected a wide range of spatial data to assess the ecosystem service functions within the study area. The data included land use data, climate and environmental data, topographic data, soil data, and other ecological datasets, as detailed in Table 1. Within the ArcGIS platform, the spatial resolution of the soil data was increased from 1000 m to 30 m using a resampling method. All spatial data were standardized to a resolution of 30 m × 30 m.

Table 1.

Research data of this study.

2.3. Research Framework

This study develops a novel, comprehensive research framework (Figure 2), which is implemented through an integrated approach that combines MSPA, a thorough evaluation of ecosystem service functions and hotspot analysis, the MCR model, and corridor extraction based on circuit theory, to identify and evaluate the ecological security pattern in Liaoning Province.

Figure 2.

Research Framework. Data Source: Authors’ own work.

The core innovation of this research framework lies in integrating landscape ecological risk assessment into the traditional “ecological source–corridor” security pattern construction framework. This approach overcomes the limitations of previous studies, which often focused on analyses of structure and function, and enables a systematic evaluation of the interrelationships among “ecosystem services, landscape connectivity, and ecological risk assessment.” Consequently, it establishes a more practically oriented ecological security pattern informed by landscape ecological risk assessment, while providing direct scientific support for prioritizing ecological conservation and restoration efforts.

2.3.1. Identification of Ecological Sources

In identifying ecological source areas, this study quantitatively evaluated ecosystem service hotspots and integrated landscape connectivity analysis to systematically determine core regions with key ecological functions [20,21]. Small, scattered patches with limited ecological influence [3] were excluded when their area was less than 10 km2, considering their relatively low contribution to the regional ecological security pattern and the challenges associated with long-term management [10,22]. For small patches that were spatially clustered, a merging strategy was applied to enhance the spatial continuity and structural integrity of the ecological sources.

(1) Ecosystem Services Function Assessment

- (1)

- Water yield

The water yield module in the InVEST 3.14.2 model was used to simulate water yield based on the Budyko water-heat coupling balance hypothesis and annual average precipitation data. The annual water yield Yjx for a grid x in land use type j in the study area is calculated as follows [7]:

where Ajx is the annual actual evapotranspiration in grid x of land use type j, in mm; Px is the annual precipitation in grid x, in mm.

Yjx = (1 − Ajx/Px)Px

- (2)

- Habitat quality

Based on the habitat quality module in the InVEST model, the habitat quality index is calculated according to the sensitivity of landscape types and the intensity of external threats, with values ranging from 0 to 1. The formula for calculating the habitat quality index is as follows [11]:

Qxj = Hj{1 − [Dxjz/(Dxjz + kz)]}

In the formula: Qxj is the habitat quality index of grid x in land use type j; Hj is the habitat suitability of land use type j; Dxj is the level of stress experienced by grid x in land use type j; k is the half-saturation constant, usually taken as half of the maximum value of Dxj; z is the normalization constant, typically set to 2.5.

- (3)

- Soil retention

The soil conservation amount is calculated based on the modified Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), and the formula is as follows [12,13]:

A = R × K × L × S × (1 − C × P)

In the formula, A is the soil conservation amount, in t/(hm2·a); R is the rainfall erosivity factor, in MJ/(hm2·a); K is the soil erodibility factor, in t·h/(MJ·mm); L is the slope length factor; S is the slope steepness factor; C is the cover and management factor; P is the erosion control practice factor.

- (4)

- Carbon storage

This study employed the InVEST model to assess regional ecosystem carbon storage. The model comprises a series of interconnected submodules that simulate the effects of land-use/land-cover changes on ecosystem service functions. In the carbon storage module, the system classifies the carbon stock of each land-use type into four fundamental carbon pools: above-ground biomass carbon, below-ground biomass carbon, soil carbon, and dead organic matter carbon. By integrating land-use maps with the corresponding carbon-density parameters of each category, the model generates the spatial distribution pattern of carbon storage.

Based on the classification of land use type, the average carbon density for different land-use types is calculated, and the formula is as follows [18,23]:

Ctotal = Cabove + Cbelow + Csoil + Cdead

Based on the carbon density of different land-use types and land-use data, the total carbon stock for each land-use type in the study area is calculated as follows:

Ctotali = (Cabovei + Cbelowi + Csoili + Cdeadi) × Ai

In the formula, Cabovei, Cbelowi, Csoili, and Cdeadi represent the average carbon density for each land-use type. Ai is the area of each land use type, and Ctotali is the total carbon stock for each land use type.

(2) Hotspot analysis

Identifying ecological sources serves as the fundamental basis of ecological conservation and restoration, with its key objective being the precise localization of strategic areas essential for maintaining ecosystem stability and biodiversity. Ecological hotspot areas, geographic units characterized by high ecosystem service capacity or rich biodiversity, represent priority targets for protection efforts. Incorporating hotspot analysis enables the effective identification of ecological sources that play a pivotal role in service provision and biodiversity maintenance, thereby offering a sound scientific foundation for conservation planning.

Given the constraints of limited conservation resources, integrating source identification with hotspot analysis allows decision-makers to focus on critical areas that simultaneously exhibit the characteristics of ecological hubs and hotspots. This approach supports the optimization of resource allocation and enhances the overall effectiveness of ecological protection.

This study used the Getis-Ord Gi* hotspot analysis method in ArcGIS 10.8 to identify ecological system service function hotspot areas in Liaoning Province. This method primarily identifies hotspot areas by spatially clustering high and low value data. It can eliminate highly fragmented and small-area regions in the data and further identify tightly connected high hotspot regions as potential ecological sources.

(3) Landscape Connectivity Analysis

In the construction of ecological networks, landscape connectivity serves as a key indicator for evaluating the efficiency of ecological flows and the smoothness of species migration. High connectivity not only facilitates species dispersal and the continuous operation of ecological processes but also enhances the stability of urban ESP [24,25,26,27].

In this study, ecological sources were first preliminarily screened based on an area threshold. Subsequently, landscape connectivity was quantitatively assessed using the Conefor 2.6 platform. During data processing, cropland, construction land, and other areas with intensive human activity were assigned as background values, whereas natural ecological land types—including forests, grasslands, shrublands, wetlands, and water bodies—were classified as foreground elements. Utilizing the eight-neighborhood analysis tool in Guidos Toolbox V2.0, landscape categories across Liaoning Province were systematically identified, and core landscape areas were extracted as the candidate range for potential ecological sources.

Subsequently, the Integral Index of Connectivity (IIC) and the Probability of Connectivity (PC) indices, proposed by Pascual-Hortal and Saura [28], were employed to evaluate the landscape connectivity of these ecological sources. Core patches with dPC > 1.5 were identified as key ecological sources, while the remaining patches were classified as potential ecological sources.

In the formula, n represents the total number of ecological patches; aᵢ denotes the area of patch i; nlᵢⱼ is the number of links in the shortest path between patches i and j; pᵢⱼ indicates the maximum product probability of all possible paths between patches i and j; and Aᴸ represents the total landscape area.

2.3.2. Construction of Ecological Resistance Surface

The theoretical foundation of the MCR model is based on the spatially heterogeneous effects of landscape resistance on ecological flow processes. The model assumes that ecological processes such as species migration and gene exchange are strongly influenced by resistance gradients formed by underlying surface characteristics. In this study, the MCR surface was constructed using ArcGIS 10.8. By quantifying the cumulative resistance from ecological source patches to target areas, the model identified the optimal paths and potential spatial patterns of ecological corridors.

Based on a systematic review of relevant literature and a comprehensive consideration of the region’s natural geographic features and the intensity of human activities, a multi-dimensional ecological resistance evaluation system was developed. This system incorporates four dimensions: land cover, ecological stress, socio-economic conditions, and topographic factors. Five indicators were selected for resistance assessment: land-use type, elevation, slope, population density, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI).

To minimize information loss that may result from categorical classification, all indicators were first normalized. Then, indicator weights were determined according to literature frequency statistics [29,30,31,32], taking into account the actual conditions of the study area and existing research findings(Table 2). Finally, the indicators were superimposed to generate a comprehensive regional ecological resistance surface. The formula for the MCR model is as follows:

Table 2.

Evaluation system of ecological resistance indicators in Liaoning Province.

2.3.3. Extraction of Ecological Corridors

Based on the established resistance surface, this study employed Circuitscape V4.0.5, grounded in circuit theory, to simulate ecological flow dynamics at the landscape scale. This model effectively captures the random-walk behavior of species movement and can infer potential migration pathways through multi-path simulations, particularly in the absence of field-based observational data [32].

Furthermore, ecological corridors were delineated using the “Linkage Mapper V2.0.0” tool in ArcGIS, with a current density threshold of 5 km applied for corridor identification [33,34]. Within ecological networks, pinch points represent critical nodes that support species movement and maintain landscape connectivity, making them priority areas for ecological conservation. Barrier points, by contrast, refer to zones that impede the exchange of species between ecological patches. By evaluating the improvement in ecological flow following the removal of such barriers, regions that exert a decisive influence on overall landscape connectivity can be identified. Previous studies have confirmed that eliminating barriers between ecological source areas can effectively enhance the integrity and coherence of landscape structure [35].

In this study, the Linkage Mapper extension module and Circuitscape software V 4.0.5 were jointly applied, together with the identified ecological sources and the constructed resistance surface, to systematically delineate both key and potential ecological corridors within the study area. By calculating the ratio of cost-weighted distance to the least-cost path (CWD: LCP), the connectivity efficiency of each corridor was quantitatively evaluated. Lower CWD: LCP values indicate higher corridor connectivity performance. Furthermore, the identified corridors were categorized into high- and low-quality classes using the natural breaks classification method, thereby establishing a quality grading system for corridors.

Building on this foundation, the Pinchpoint Mapper tool within the Linkage Mapper Toolbox V2.0.0 was employed in the “all-to-one” analysis mode to locate ecological pinch points along these corridors. After multiple iterations of radius parameter testing and drawing on findings from previous studies [36], the analysis width for corridors was set to 1000 m to enhance ecological relevance. The simulated current density values were then reclassified using the natural breaks method, and areas with the highest current density were extracted as critical ecological pinch points.

For barrier identification, the Barrier Mapper tool within the Linkage Mapper Toolbox V2.0.0 was utilized to detect critical regions that obstruct species migration. After repeated trials and validation with relevant literature [37], both the search radius and step length were set to 1100 m, allowing the identification of ecological barrier points within the study area.

In this study, the landscape connectivity index is used to identify ecological sources, the MCR model is employed to construct the minimum resistance surface, and circuit theory is applied to optimize the corridor network structure. Each method undertakes a distinct analytical task within the workflow, collectively forming a coherent technical pathway composed of “sources–resistance–corridors.”

2.3.4. Landscape Ecological Risk

To analyze the spatial distribution pattern and regional differences in ecological risk, this study adopted the grid-based assessment framework proposed in [38], dividing the entire study area into regular grids of 20 km × 20 km, resulting in 1276 valid assessment units. After calculating the landscape ecological risk index for each unit, the Kriging interpolation tool in ArcGIS 10.8 was used to generate a continuous spatial distribution map of ecological risk. Finally, the ecological risk levels of the study area were classified into five categories using the natural breaks method, namely: low ecological risk, relatively low ecological risk, moderate ecological risk, relatively high ecological risk, and high ecological risk.

Based on the actual conditions of the study area, three core evaluation indicators were selected: the landscape disturbance index (Eᵢ), landscape fragility index (Fᵢ), and landscape loss index (Rᵢ) (Table 3 and Table 4). These indicators were used to construct a landscape ecological risk assessment model, which is calculated using the following formula:

Table 3.

Calculation formulas of landscape ecological risk indices. Data source: Formulas and Definitions.

Table 4.

Parameter Setting for Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment. Data source: Authors’ own work.

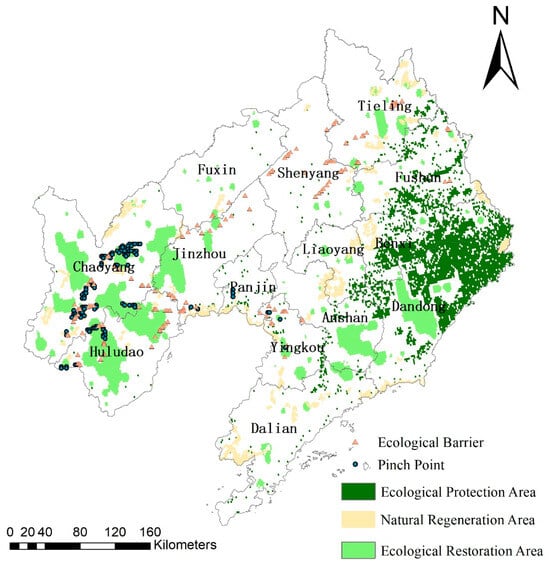

2.3.5. Identification of Priority Ecological Restoration Areas

This study integrated the spatial distribution of landscape ecological risk, ecosystem service function levels, and ecological source identification results to construct the ecological security pattern of Liaoning Province and delineate corresponding priority conservation zones through spatial overlay analysis.

Specifically, low-risk and relatively low-risk landscape ecological risk zones were spatially overlaid with the top 30% of areas in ecosystem service function values to identify priority ecological conservation areas, which serve as the core regions for maintaining regional ecological security. Meanwhile, areas identified as high-risk zones based on landscape pattern indices were designated as ecological restoration areas. These patches may exhibit deficiencies in quality or structure but possess high potential for ecological restoration and conservation value.

In addition, small ecological patches (areas smaller than 5 km2) and transitional zones located between core areas and restoration zones were classified as auxiliary regeneration areas. Although their ecological functions are relatively limited, these areas play an important role in enhancing landscape connectivity, providing habitats for small mammals and birds, and serving as critical ecological linkages within regions of intense human activity.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Ecosystem Services and Ecological Hotspots

Using the InVEST model, this study calculated water yield, carbon storage, habitat quality, and soil retention. The spatial distributions of these ecosystem services are shown in Figure 3. Among them, Fushun, Benxi, Dandong, and Anshan exhibit strong water-yielding capacities. In addition, due to the relatively high vegetation coverage in Fushun, Benxi, Dandong, Anshan, and parts of Yingkou compared with other cities, the corresponding soil retention, carbon storage, and habitat quality indices are also relatively high.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of key ecosystem service functions in Liaoning Province (a) water yield, (b) carbon storage, (c) habitat quality, (d) soil retention. Data source: Authors’ own work.

Chaoyang and Huludao rank next, with certain areas showing relatively high soil retention, habitat quality, and carbon storage values. In regions with dense vegetation cover, such as forests and grasslands, soil retention performance is significantly better than in bare or sparsely vegetated areas. High-value zones of habitat quality are mainly concentrated in wetland and forest regions, where human disturbances are minimal and environmental quality remains high. Similarly, wetlands and forests also show high levels of carbon storage due to dense vegetation cover, which enables more effective climate regulation.

The four types of ecosystem services were standardized and then summed through an overlay operation. The results of this computation were again standardized to obtain the final spatial distribution map of ecosystem service functions in the study area (Figure 4a). From the perspective of landscape types, forests and wetlands exhibit high values across all four ecosystem services, effectively regulating climate and providing abundant ecological resources. Areas with moderate ecosystem services are primarily composed of grasslands and farmland, widely distributed in Chaoyang, Huludao, and Dalian. Regions with lower ecosystem service values are mainly found in Shenyang, Jinzhou, Fuxin, and Panjin, where vegetation coverage is low and human disturbance is high.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of ecological hotspot areas in Liaoning Province (a) ecosystem service; (b) ecosystem service hotspot. Data source: Authors’ own work.

The Getis-Ord Gi* tool in ArcGIS 10.8 was applied to analyze the spatial clustering of ecosystem functions in Liaoning Province, identifying ecological hotspots (Figure 4b). A hotspot represents an area where data values are significantly higher or lower than those of neighboring regions, exhibiting spatial aggregation of high or low values. The spatial distribution of hotspots and cold spots in Liaoning Province is shown in Figure 4b. The ecological function hotspots are mainly concentrated in Dandong, Fushun, Benxi, Anshan, and parts of Liaoyang and Yingkou.

3.2. Identification of Ecological Sources in Liaoning Province

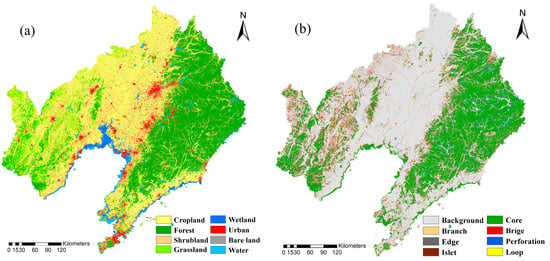

3.2.1. Ecological Source Identification Based on MSPA

The relationship between the extracted ecological sources and land-use types was analyzed to reveal how land-use patterns influence source distribution and ecological connectivity. In this study, land-use data from 2023 were used to perform the MSPA, as shown in Figure 5a. In Liaoning Province, land-use classification primarily includes cropland, forest land, shrubland, grassland, wetland, construction land, bare land, and water bodies. Among these, grassland has the highest proportion at 45.34%, followed by forest land at 29.3%, cropland at 16.3%, wetland at 0.74%, and water bodies at 2.55%.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of ecological sources based on MSPA. ((a). land use type; (b). analysis results of MSPA). Data source: Land-use data from the Data Sharing and Service Portal; MSPA results calculated by the authors.

Based on the MSPA, seven types of ecological landscape areas were identified (Table 5), with a total area of approximately 500,208.20 km2. Among them, the core area was the largest, covering about 40,502.16 km2, accounting for 27.33% of the total ecological landscape area (Figure 5b). The edge area forms the outer boundary of the core area and serves as a transition zone between the core and adjacent non-ecological landscapes; the islet area represents small patches of non-ecological land within core regions. These two types account for 5.84% and 1.56% of the total ecological landscape area, respectively.

Table 5.

Area proportions of MSPA landscape types in the study area. Data source: Authors’ own work.

Isolated patches, which are sporadically distributed across the study area, comprise approximately 1.9% of the total ecological landscape area. The branch, bridge, and loop zones all contribute to ecological connectivity. A smaller number of these zones indicates weaker connectivity, greater obstruction to ecological flows and processes, and less favorable conditions for biodiversity. Specifically, branches, which connect the core area to other ecological landscapes, account for 2.42% of the total area; bridges, which connect multiple core areas, account for 2.67%; and loops, representing shortcut corridors for species migration within core areas, cover the smallest area—approximately 2500 km2, or 1.68%.

The MSPA results were further imported into the Conefor software V2.6 to calculate the landscape connectivity indices. Areas corresponding to the top 30% of dPC and dIIC values (as defined by Equations (6) and (7) were extracted and identified as ecological source areas, as illustrated in Figure 5.

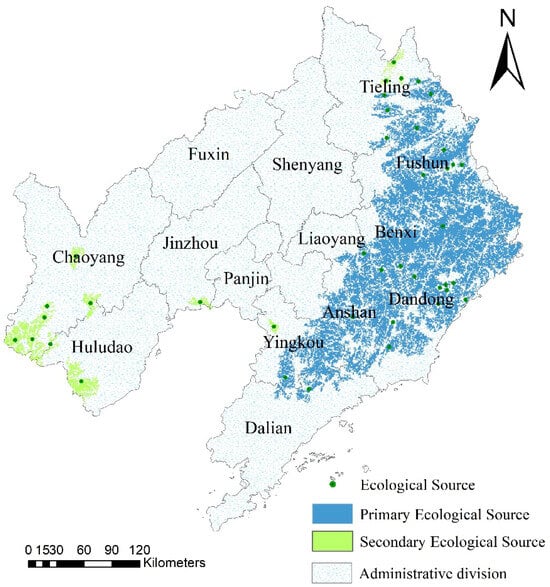

3.2.2. Identification of Ecological Sources Considering the Spatial Relationships of Ecosystem Services

By overlaying the ecosystem service hotspot areas with the landscape connectivity zones derived from MSPA, the spatial relationship between ecological functions and structural connectivity was examined. Overall, at the macro scale, larger patches within Liaoning Province generally exhibit higher levels of connectivity. Given that the dPC index is positively correlated with ecological connectivity (i.e., higher dPC values indicate better connectivity), this study employed the Conefor software V2.6 to conduct the landscape connectivity assessment and ultimately identified 40 core ecological patches as ecological source areas.

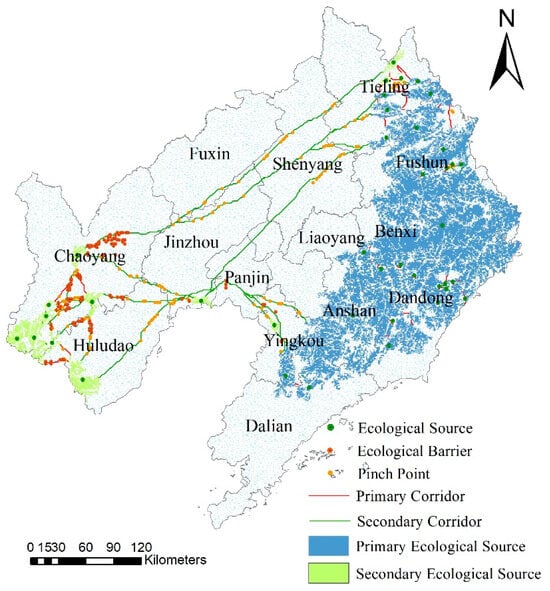

The total area of ecological sources in Liaoning Province was 17,628 km2, accounting for 12% of the province’s total area. Based on the regional conditions, patches with dPC > 1.5 were classified as primary ecological sources, comprising 29 patches with a total area of 16,128 km2. Areas with dPC < 1.5, indicating relatively weak ecological connectivity, were categorized as secondary ecological sources, including 11 patches with a total area of 1499.4 km2. These can serve as potential ecological source areas (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Extraction results of ecological sources in Liaoning Province. Data source: Authors’ own work.

The ecological sources were mainly distributed across Dandong, Fushun, Anshan, Benxi, Chaoyang, Huludao, Jinzhou, and Yingkou. The dominant land use types in these regions are forest, shrubland, and water bodies. Overall, the ecological source patches are relatively few in number and spatially scattered.

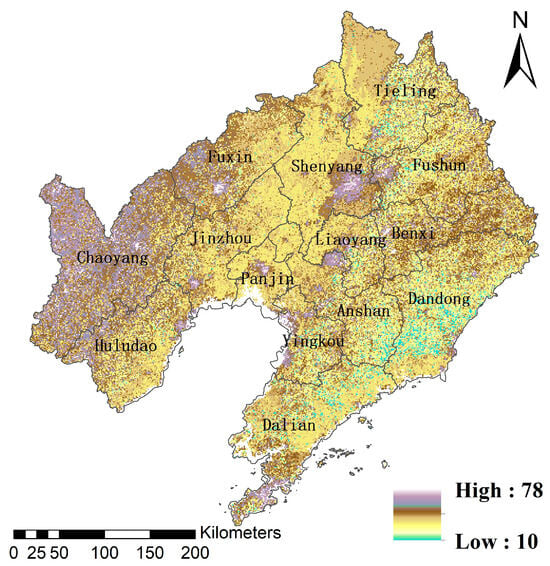

3.2.3. Spatial Distribution of the Ecological Resistance Surface

The comprehensive ecological resistance surface was constructed using five environmental factors: land use type, NDVI, elevation, slope, and population density (Figure 7). Its spatial distribution exhibits clear east–west heterogeneity. The ecological resistance surface of Liaoning Province is shown in Figure 7, with resistance values ranging from 10 to 78.

Figure 7.

Construction of ecological resistance surface in Liaoning Province. Data source: Authors’ own work.

Overall, areas in the southwest with intensive human activity exhibit significantly higher resistance values than those in the northeast, with high-resistance zones scattered sporadically across the southwest. This pattern is primarily influenced by vegetation cover and topography. Regions with higher resistance are mainly distributed in Chaoyang, Fuxin, and parts of Shenyang, Huludao, and Dalian.

Detailed analysis indicates that lower vegetation coverage, higher elevation, and steeper slopes correspond to higher resistance values. These conditions often create ecological chain effects, where such areas are less capable of supporting rich biodiversity, exhibit poor connectivity, and render ecosystems more susceptible to external pressures and disturbances.

3.2.4. Ecological Corridors and Key Ecological Nodes

- (1)

- Construction of Ecological Corridors

By simulating the flow of electric current within a circuit, key nodes and optimal paths of ecological corridors can be identified, thereby maximizing connectivity and ecological efficiency. In this study, the Linkage Mapper tool was employed to generate the shortest-distance corridors, and the extracted ecological corridors of Liaoning Province are shown in Figure 8. The ecological security pattern (ESP) of Liaoning Province comprises 89 ecological corridors with a total length of 3533.9 km and an average length of 39.7 km. The longest corridor measures 404.8 km, connecting two ecological sources located in Chaoyang City and Tieling City.

Figure 8.

Distribution of ecological corridors. Data source: Authors’ own work.

Among them, there are 47 primary corridors with a total length of 368.45 km—the shortest primary corridor measures 1.16 km, the longest reaches 44.55 km, and the average length is 7.84 km. Additionally, there are 42 secondary corridors, totaling 3165.48 km in length. The shortest secondary corridor measures 1.16 km, the longest extends 404.87 km, and the average length is 75.37 km. Spatially, the northern and eastern regions exhibit shorter and denser corridors due to the larger area and higher number of ecological sources distributed across these zones.

- (2)

- Key Ecological Nodes

Using the results generated by the Pinchpoint Mapper tool, a total of 139 ecological pinch points were identified in this study (Figure 9). Spatially, these pinch points are mainly concentrated between secondary ecological sources and along secondary ecological corridors. Their formation mechanism lies in the fact that these areas function as “bottlenecks” in ecological processes. Although their natural substrate is generally more fragile than that of primary corridors, they bear crucial ecological connectivity functions. Once subjected to human disturbance or natural stress, they can easily evolve into the most sensitive and vulnerable links within the system.

Figure 9.

Distribution of ecological pinch points and ecological barrier points. Data source: Authors’ own work.

In addition, the Barrier Mapper tool identified 109 ecological barrier points, which show a similar spatial distribution pattern, mainly located around secondary ecological sources and corridors in southwestern Liaoning. This pattern is closely tied to regional environmental conditions: the landscapes in southwest Liaoning are dominated by low mountains, hills, coastal plains, and sandy lands, forming a relatively fragile ecological background. Moreover, large stretches of farmland have fragmented natural habitats into isolated patches. Secondary corridors crossing agricultural landscapes are often obstructed by farmland, creating ecological barriers.

Compared to eastern Liaoning, where vegetation coverage is high and ecological structure is stable, southwestern Liaoning exhibits higher ecological sensitivity and weaker self-recovery capacity. Secondary ecological sources in this region are often small forest, grassland, or wetland patches with fluctuating ecological functions. The secondary corridors connecting these sources are typically narrow and poorly continuous, with low resistance to disturbance. Consequently, species migration in southwestern Liaoning faces greater resistance, and ecological restoration in this region is more complex and challenging.

3.3. Construction of the Ecological Security Pattern

3.3.1. Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment in Liaoning Province

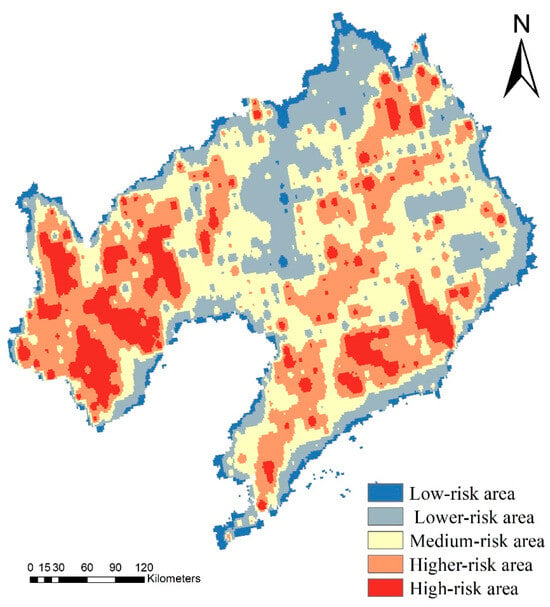

The ecological risk index (ERI) was calculated for each landscape ecological risk unit. The results were spatially interpolated and fitted using ordinary kriging, followed by standardization. Based on the natural breaks (Jenks) method, ecological risk levels were classified into five categories: low risk (0–0.39), relatively low risk (0.39–0.50), moderate risk (0.50–0.58), relatively high risk (0.58–0.68), and high risk (0.68–1). Accordingly, Liaoning Province was divided into corresponding ecological risk zones, and the spatial distribution of ecological risk levels for 2023 was obtained (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Comprehensive Ecological Risk in Liaoning Province. Data source: Authors’ own work.

The high-risk areas are mainly concentrated in most parts of Chaoyang and Huludao, as well as local areas in Anshan, Dandong, and Tieling. These regions are likely to experience severe ecological disturbances, such as land-use changes and intensive human activities, leading to low landscape stability and high ecological risk. The relatively high-risk areas are widely distributed, covering parts of Fuxin, Jinzhou, Liaoyang, Yingkou, and Dalian, along with local regions of Shenyang, Fushun, and Benxi. These areas exhibit moderately high ecological risks, characterized by weakened landscape integrity and reduced resistance to disturbances. The moderate-risk zones appear as patchy distributions interspersed among the higher-risk regions, showing medium-level ecological risk and relatively stable landscape functions, though they still require attention. The relatively low-risk areas are mainly distributed in parts of Shenyang, Benxi, and Panjin, where ecosystems are less disturbed and landscape stability is relatively strong. The low-risk areas, mostly located along the provincial edges—such as coastal zones and mountainous margins—cover relatively small areas but maintain well-preserved ecosystems with low overall risk levels.

3.3.2. Delineation of Priority Restoration Areas in Liaoning Province

As shown in Figure 11, the ecological restoration zoning of Liaoning Province exhibits an overall east–west differentiation and north–south extension pattern, resulting in a belt-like spatial structure. The assisted regeneration zones are the most widely distributed, covering nearly the entire Liaohe Plain and the Bohai coastal region. These areas serve as key “ecological stitching zones” for enhancing landscape connectivity in the future. Overall, the eastern region—dominated by the remnants of the Changbai Mountains—features extensive dark-green ecological conservation zones, representing the province’s most critical areas for water conservation and biodiversity maintenance. Similarly, the western Nuruerhu–Yanshan mountain system forms a continuous dark-green belt that functions as a windbreak, sand-fixation barrier, and ecological shield preventing the southward expansion of the Horqin Sandy Land. The central Liaohe Plain and the Bohai coastal belt are primarily characterized by assisted regeneration zones, which correspond to regions with intensive agriculture and urbanization, where habitats are highly fragmented.

Figure 11.

Identifying Ecological Priority Restoration Areas in Liaoning Province. Data source: Authors’ own work.

The ecological conservation zones are mainly distributed in eastern and western Liaoning, the Fushun–Xinbin junction area, and the Qinglong River Gorge in Chaoyang. The ecological restoration zones are primarily located in northwestern Liaoning, the Liaohe Estuary, the Liaodong Peninsula, and the Pulandian area of Dalian. The assisted regeneration zones are concentrated in the alluvial plains extending from Shenyang, Anshan, and Panjin to Yingkou, as well as in the Bohai coastal aquaculture pond clusters of Huludao and Jinzhou.

4. Discussion

4.1. Construction and Significance of the Ecological Security Pattern

This study systematically constructed the ecological security pattern of Liaoning Province by integrating multiple key elements, including ecological sources, resistance surfaces, corridors, and nodes [9,16]. On this basis, a further overlay analysis with the landscape ecological risk assessment was performed to pinpoint risks arising from the landscape morphology of the ecological sources. In contrast to other approaches, this study is distinctive in its incorporation of not only landscape structure but also morphological attributes, thereby enhancing the scientific validity of the findings. The results reveal a distinct spatial pattern characterized by east–west differentiation and north–south extension. Ecological sources are mainly distributed in the mountainous forest regions of eastern and western Liaoning. These areas serve not only as hotspots of ecosystem services but also as core ecological patches identified through MSPA, providing essential functions such as water conservation, biodiversity maintenance, and carbon sequestration.

In contrast, the central Liaohe Plain and Bohai coastal areas exhibit high ecological resistance and severe corridor fragmentation, corresponding closely to zones of intensive agricultural activity and urbanization. This spatial pattern highlights a critical issue: the ecological connectivity between the eastern and western ecological highlands has been disrupted by human activity in the central region.

A total of 89 ecological corridors were identified in this study, the longest of which connects Chaoyang City and Tieling City, along with 139 ecological pinch points, which provide vital spatial guidance for restoring these disrupted linkages. Moreover, areas with high landscape ecological risk values significantly overlap with regions of high ecological resistance and concentrations of ecological barriers, particularly in Chaoyang and Huludao. This indicates that these zones should be prioritized for ecological protection and restoration efforts.

The integration of landscape ecological risk assessment with conventional ecological security pattern analysis enhances the identification of landscape risks in ecological source areas, thereby supporting the systematic optimization of ecological restoration strategies. The ecological security pattern established in this study not only delineates the “arteries” and “capillaries” of Liaoning’s ecological network but, more importantly, identifies its vulnerable points and bottlenecks, providing a robust scientific foundation for implementing differentiated ecological protection strategies.

4.2. Recommendations for Optimizing the Ecological Security Pattern

Based on the above findings, this study proposes three recommendations for optimizing the ecological security pattern of Liaoning Province:

- (1)

- Prioritize conservation in the ecological source areas of eastern and western Liaoning (ecological protection zones). Development and construction activities should be strictly restricted, and the principle of “protection first” must be adhered to. Efforts should focus on strengthening the protection of natural forests and expanding nature reserves to maintain the stability of core ecological functions. For the auxiliary regeneration zones in the central Liaohe Plain, ecological restoration should be prioritized. Measures such as constructing green infrastructure, promoting ecological agriculture, and planning ecological buffer zones and urban forests within urban agglomerations can gradually reduce ecological resistance and repair fragmented habitats.

- (2)

- Focus on the 139 identified ecological pinch points and 109 ecological barriers, particularly those within the fragile ecosystems of southwestern Liaoning. Combined engineering and biological measures should be implemented to improve connectivity. In agricultural landscapes, ecological pinch points can be enhanced through the establishment of ecological ditches, shelterbelts, and small wetland parks, creating “stepping stones” for species migration. For barrier points that impede connectivity, constructing eco-bridges, wildlife corridors, or similar infrastructure is recommended to mitigate obstruction.

- (3)

- Strengthen cross-administrative ecological governance. Many ecological corridors and source areas identified in this study extend across multiple municipal boundaries. A province-level coordination mechanism for ecological corridor protection and restoration should therefore be established to ensure unified planning and implementation of cross-regional ecological projects, avoiding “disconnection” caused by administrative fragmentation.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

The resistance surface constructed in this study is primarily based on static factors, including land use type, NDVI, elevation, slope, and population density. It does not incorporate linear elements such as highways and railways as independent resistance factors. This omission is primarily due to the practical challenges associated with obtaining comprehensive, consistent, and spatially precise vector data for linear infrastructure across the entire province at a regional scale. Secondly, this study presents a static snapshot of the ecological security pattern at a specific point in time.

However, ecosystems are inherently dynamic and are continuously influenced by human activities and climate change [22]. The current research does not capture the spatiotemporal evolution trajectory of the ecological security pattern or its response mechanisms to natural and anthropogenic drivers. Therefore, future research efforts will integrate multi-source transportation and infrastructure data to achieve differentiated resistance characterization of linear barriers. Additionally, the introduction of long-term remote sensing time-series data and socio-economic scenario simulations will facilitate the dynamic monitoring and trend prediction of ecological security patterns, thereby enhancing the study’s predictive capacity and applicability to planning.

5. Conclusions

The ecological security pattern of Liaoning Province exhibits a distinct spatial differentiation characterized by a “barrier in the east and west, fragmentation in the center.” A total of 40 key ecological sources were identified, covering an area of 17,628 km2; 89 ecological corridors with a total length of 3533.9 km; as well as 139 ecological pinch points and 109 ecological barrier points. The mountainous regions of Dandong, Fushun, Benxi, and Anshan in the east, along with Chaoyang and Huludao in the west, serve as critical ecological source areas and ecosystem service hotspots, forming the dual ecological “screens” that safeguard the province’s ecological security.

The results indicate that the vulnerability of Liaoning’s ecosystem lies not only in the isolation of ecological sources but also in the connectivity between them, particularly in the secondary corridors that traverse agricultural landscapes and fragile ecosystems in the central and western regions. These corridors and their associated key nodes act as bottlenecks for ecological flows and represent priority areas for future ecological restoration and spatial optimization.

In summary, the proposed framework demonstrates reliable performance and good applicability within the defined methodological scope and data conditions, effectively supporting the identification of ecological sources, corridors, and priority protection zones. Future ecological governance should shift its focus beyond traditional individual patches to adopt a systematic strategy that maintains overall network connectivity. Priority should be given to the restoration and protection of critical corridors and vulnerable nodes, thereby enhancing the province’s overall ecological security and capacity for sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y. and S.Y.; methodology, R.Y., H.W. and Y.L.; formal analysis, R.Y., B.X. and S.Y.; investigation, S.Y. and G.L.; resources, G.L. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and R.Y.; supervision, D.X. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem Restoration, Ministry of Ecology and Environment (2023-05); Development Fund of the Key Laboratory of Water and Sediment Sciences, Ministry of Education (SS202301); Special Fund for Science & Technology Infrastructure Resources Survey (2022FY100301).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are derived from interviews conducted with relevant stakeholders.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Zhou, C.H. Review of the Studies on Ecological Security. Prog. Geogr. 2005, 24, 8–20, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.D.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.L.; Tao, H.Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.P.; Wang, Y.Y.; Guo, Y.C. Ecological security as the key to sustainable development in mining resource-based cities: A case study from China on evolutionary pattern, influencing factors, and future trends. Habitat Int. 2025, 166, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.T.; Wu, Y.W.; Yuan, H.W.; Gong, J.Z. Agglomerations of Eastern China Construction and Optimization Strategies of Ecological Security Pattern in Mega Urban. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 7344–7357, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Peng, J.; Liu, Y. Construction of ecological security pattern in Yunfu City based on the framework of “Importance-Sensitivity-Connectivity”. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 471–484, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Tang, H.; Liang, X.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Z.J.; Guan, Q.F. Using ecological security pattern to identify priority protected areas: A case study in the Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, S.Q.; Dong, J.Q.; Liu, Y.X.; Meersmans, J.; Li, H.L.; Wu, J.S. Applying ant colony algorithm to identify ecological security patterns in megacities. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 117, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Zhou, D.M.; Jiang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Q.H.; Jia, Y.Y. Spatiotemporal evolution pattern of water yield service of ecosystems in the Shule River Basin, Northwest China, integrating future climate and land use changes. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Xian, Q.; Huang, Q.Y.; Yang, C.; Shu, J.Y.; Yao, C.Y.; Pan, H.Y. Research on ecological security pattern based on the paradigm of “portray-assessment-construction-validation”—Minjiang River Basin as an example. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, M.Q.; Hu, M.M.; Xia, B.C. Integrating ecosystem services and landscape connectivity into the optimization of ecological security pattern: A case study of the Pearl River Delta, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 76051–76065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Chen, J.J.; Huang, R.J.; Feng, Z.H.; Zhou, G.Q.; You, H.T.; Han, X.W. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern Based on the Importance of Ecological Protection-A Case Study of Guangxi, a Karst Region in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtbozorgi, F.; Hedayatiaghmashhadi, A.; Dashtbozorgi, A.; Ruiz-Agudelo, C.A.; Fürst, C.; Cirella, G.T.; Naderi, M. Ecosystem services valuation using InVEST modeling: Case from southern Iranian mangrove forests. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 60, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Yang, Y.C.; Guo, Z.C. Ecological security pattern construction and optimization in Arid Inland River Basin: A case study of Shiyang River Basi. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 5915–5927, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.L.; Xin, W.X.; Mao, X.P.; Shao, D.L.; Chen, Q.W.; Zhu, Y.J.; Han, F.P. Trade-off relationships of ecosystem services for soil retention carbon sinks in the Loess Plateau of China. Land Use Policy 2025, 158, 107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.G.; Lin, Y.L.; Zhao, J.S.; Chen, G.P.; He, W.C.; Lv, Q.Z. Identification of key areas for the ecological restoration of territorial space in Kunming based on the InVEST model and cireuit theory. China Environ. Sci. 2023, 43, 809–820, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Huang, T. Multi-scale transformation and evolutionary factors of ecological security patterns in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.S.; Zou, Y.T. Construction of an ecological security pattern based on ecosystem sensitivity and the importance of ecological services: A case study of the Guanzhong Plain urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.C.; Wu, W.J.; Guo, J.; Ou, M.H.; Pueppke, S.G.; Ou, W.X.; Tao, Y. An evaluation framework for designing ecological security patterns and prioritizing ecological corridors: Application in Jiangsu Province, China. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2517–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.Z.; Wang, H.; Lyu, X.; Li, X.B.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Lu, Y.T.; Zhao, X.L.; Qu, T.F.; et al. Construction and optimization of ecological security patterns in Dryland watersheds considering ecosystem services flows. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.D.; Fahrig, L.; Henein, K.; Merriam, G. Connectivity is a vital element of landscape structure. Oikos 1993, 68, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Jia, Y.Y. Construction and evolution of river basin ecological network based on circuit theory and MSPA: A case study of Dawen River Basin. Ecol. Model. 2025, 510, 111364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, H.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Wu, J.S. Research progress and prospect on regional ecological security construction. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 407–419, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, R. Priority conservation zoning for future karst areas based on the construction of a multi-perspective ecological security pattern. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Wen, Z.F.; Wu, S.J.; Bi, Y. Identification and optimization of ecological security pattern in the Chengdu-Chongqing Economie Zone. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 973–985, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Z.X.; Yang, S.; Zhu, B.K.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, J.H. Identification of key ecological restoration areas based on ecological security patterns and territorial spatial ecological restoration zoning: A case study of the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River in China. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 84, 126793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.u.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X. Integrating the MCR and DOI models to construct an ecological security network for the urban agglomeration around Poyang Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, P.; Ferrari, J.R.; Lookingbill, T.R.; Gardner, R.H.; Riitters, K.H.; Ostapowicz, K. Mapping functional connectivity. Ecol. Indic. 2009, 9, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.F.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.D.; Li, Y.R.; Zhang, L.X. Identification and optimization of ecological corridors in the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 512, 145676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Hortal, L.; Saura, S. Comparison and development of new graph-based landscape connectivity indices: Towards the priorization of habitat patches and corridors for conservation. Landsc. Ecol. 2006, 21, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.W.; Zhang, S.P.; Xu, Q.X.; Dai, J.F.; Huang, G.L. Construction of Cross basin Eeological Security Patterns Based on Carbon Sinks and Landscape Connectivity. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 5844–5852, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Yang, J.Q.; Zhu, L.; Sun, L.P. Identification of Ecological Priority Areas Based on Nested-Scale Analysis: A Case Study of Metropolitan Nanjing, China. Land 2025, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.F.; Liu, Z.S.; Li, S.J.; Gao, Z.J.; Sun, B.W.; Li, Y.X. Identification of key areas of ecological protection and restoration based on the pattern of ecological security: A case of Songyuan City, Jilin province. China Environ. Sci. 2022, 42, 2779–2787, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.Y.; Ye, H.Y. Identification of ecological networks in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area based on habitat quality assessment. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 10430–10442, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhuona, S.; Yiyang, J.; Dongmei, Z.; Xin, H.; Jing, J.; Xiaoyan, Z.; Jun, Z. Constructing an ecological security pattern by integrating ecosystem service values and ecological sensitivity: A case study of the Hexi Region, China. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2026, 29, 101070. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, P.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Ning, S. Multilevel Green Space Ecological Network Collaborative Optimization from the Perspective of Scale Effect. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.Y.; Fang, W.; Zheng, J.N.; Tang, X. Identification of key areas for ecological restoration of national land space. Beijing Surv. Mapp. 2025, 39, 327–333, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.J.; Su, J.; Hu, X.J.; Xu, K.H.; Zhu, M.L.; Liu, L.Y. Comprehensive identification of eco-corridors and eco-nodes based on principle of hydrological analysis and Linkage Mapper. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 2995–3009, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.J.; Xu, Q.L.; Yi, J.H.; Zhong, X.C. Integrating CVOR-GWLR-Circuit model into construction of ecological security pattern in Yunnan Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 81520–81545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Z.X.; Liu, B.; Guan, D.Y. Landscape ecological risk assessment for the black soil region in Northeast China based on land use change. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2025, 56, 140–155, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.