Abstract

Using panel data for 30 provinces in mainland China (2013–2022), this research examines how artificial intelligence (AI) affects green innovation resilience (GIR) and the mechanisms through which this occurs. It tests industrial structure advancement and industrial structure rationalization as mediating channels, and evaluates threshold effects associated with public environmental concern and environmental regulation. The results indicate that AI is positively and significantly related to GIR, and the conclusion remains stable under multiple alternative specifications and robustness checks. Further analysis reveals that different dimensions of industrial structure upgrading play distinct roles. AI indirectly strengthens innovation resilience through the quantity and quality dimensions of industrial structure advancement, whereas industrial structure rationalization does not constitute an effective transmission channel, highlighting heterogeneity in technological–structural synergy. Moreover, the threshold effects of public environmental concern and environmental regulation differ markedly. Public environmental concern exhibits a critical threshold that needs to be maintained within a reasonable range, whereas stronger environmental regulation amplifies the technological dividends of AI in a staircase reinforcement pattern. Overall, this study systematically explores the mechanisms and boundary conditions through which AI drives green innovation resilience, providing new theoretical insights and empirical evidence for green transformation in the AI era.

1. Introduction

In the context of intensifying global climate governance and the concurrent pursuit of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality objectives, green innovation has increasingly been positioned as a pivotal approach to easing resource and environmental pressures and to reorienting the drivers of economic growth. Nevertheless, prior studies on green technological innovation have largely emphasized static gains in efficiency, with comparatively limited attention devoted to the robustness and adaptive capacity of innovation systems under volatile and uncertain conditions. According to tracking data released by Bloomberg New Energy Finance in the first quarter of 2024, mergers and acquisitions in the global clean technology sector increased by 67 percent year on year, with 54 percent involving asset restructuring triggered by failures in technological pathways [1]. These patterns suggest that technological path dependence and a lack of dynamic adaptability have become major bottlenecks in sustaining green innovation, highlighting the urgent need for scholars to redefine green innovation from a dynamic resilience perspective, moving beyond traditional productivity indicators. Some researchers have proposed the concept of green innovation resilience, which refers to the ability of a green innovation system to resist external shocks, maintain stability, adapt, recover, and even evolve to a higher functional state when facing disruptions [2]. In the current global context of economic slowdown, stagnant demand growth, and increasing technological barriers, green innovation resilience has become crucial for enterprises to transform risks into opportunities and achieve sustainable development [2]. The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, with its advantages in data processing, pattern recognition, and decision support, offers new approaches to enhancing green innovation resilience [3]. Thus, investigating how AI impacts green innovation resilience holds both significant theoretical value and practical relevance for the sustainable development of green innovation in China and globally.

A review of the literature reveals that scholars have examined the impact of AI on green technological innovation [4,5,6], green innovation efficiency [7,8], green investment [9], green finance [10,11,12], and green economic development [13,14]. However, most studies focus on AI’s direct impact on green innovation output, overlooking its dynamic role in shaping system resilience. AI can offer precise and efficient strategies for enterprises, enhancing their ability to respond, recover, and innovate in the face of complex environmental changes [15], thereby boosting green innovation resilience. Therefore, it is crucial to explore AI’s influence on provincial innovation resilience. From an industrial structure perspective, AI improves production efficiency, enhances industry scalability and innovation capabilities, promotes industrial advancement, and strengthens the capacity to address environmental challenges [16,17]. Furthermore, AI enables more efficient production processes, allowing for continuous adjustments in industrial structure and fostering greater rationality [18], which enhances resilience to external shocks. However, the mediating effects of industrial structure advancement and rationalization in the context of AI diffusion remain underexplored. Additionally, how the “dual pressure field” formed by public environmental concern and environmental regulation shapes AI’s role in green innovation resilience requires further investigation. Therefore, this study examines the threshold effects of public environmental concern and environmental regulation, analyzing their roles in AI’s influence on green innovation resilience.

In China, green innovation resilience is shaped by the diffusion of artificial intelligence technologies, ongoing industrial restructuring, and evolving practices of environmental governance. Over the past decade, the country has accelerated its transition from rapid growth to high-quality development, and provinces have shown pronounced differences in industrial bases, technological capacity, and energy-use patterns. Some regions have formed strong clusters of emerging industries and advanced manufacturing, supported by relatively sound digital infrastructure and faster progress in green technology research and application. In contrast, other regions remain dominated by resource- and energy-intensive industries, resulting in higher energy consumption and pollutant emissions and facing stronger constraints due to long-term dependence on traditional development paths. Meanwhile, provinces also vary substantially in their targets for energy saving and emission reduction, investments in pollution control, the composition of environmental regulatory instruments, and the level of public environmental concern. These disparities indicate distinct development trajectories as regions gradually shift from factor-driven and heavy-industry-based growth toward development led by innovation and green industries. Under this institutional and structural setting, the interplay among AI development, industrial upgrading, and environmental governance pressures influences how provincial green innovation systems absorb shocks and adjust to changing conditions. This context therefore offers a representative empirical basis for assessing how AI contributes to the strengthening of green innovation resilience.

This study uses panel data from 30 provinces in mainland China (excluding Tibet) from 2013 to 2022 to empirically explore AI’s direct impact on innovation resilience. It also examines whether this effect operates through two mediating channels: industrial structure advancement and industrial structure rationalization. Industrial structure advancement describes the extent to which a region’s industrial composition shifts from lower-end activities toward higher-end sectors, whereas industrial structure rationalization captures the degree of coordination and alignment in resource allocation among industries. Moreover, the analysis evaluates potential threshold effects associated with public environmental concern and environmental regulation. Public environmental concern represents the level of public attention to environmental protection and green innovation, while environmental regulation reflects the stringency of government constraints, implemented through regulatory requirements and governance actions targeting pollution emissions and resource-use behaviors. By integrating these tests, the study seeks to identify the mechanisms and boundary conditions under which AI influences green innovation resilience at the provincial level.

The findings of this research offer valuable insights for improving the theoretical framework of digital technology-enabled green transformation and optimizing regional innovation resilience enhancement strategies. Compared to existing literature, this study makes the following contributions: (1) In contrast to previous studies on static green innovation [4,5,6,7,8], this study introduces resilience theory into the study of AI and green innovation. It shifts the focus from static efficiency improvements to the dynamic stability of green innovation systems, providing a new perspective on how AI supports these systems. This offers a more comprehensive and dynamic theoretical framework for future research. (2) This study reveals the differential transmission path of industrial structure advancement and industrial structure rationalization. Different from the previous one-dimensional cognitive framework of industrial structure advancement [19], this study deconstructs the transmission mechanism from the dual dimensions of scale expansion (quantity) and value transition (quality). It systematically characterizes the progressive development logic of industrial structure from a low-level state to a high-level state and clarifies the role of industrial structure advancement. The research helps us understand the impact of different industrial structure changes on green innovation resilience, and provides a clear path for policymakers and enterprises. (3) This study identifies differentiated threshold effects of environmental regulation intensity and public environmental concern, offering a quantitative foundation for tailored policy design. It demonstrates that AI’s effect on green innovation resilience varies significantly under different environmental regulation intensities and levels of public concern. Thus, this research not only provides policymakers with a reference for designing region-specific policies but also offers strategic guidance to enterprises on how to leverage AI technology in response to varying environmental pressures.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Green Innovation Resilience

Organizations inevitably face shocks from both internal and external environmental changes during their development and operations. A central question is why some organizations fail during extreme events while others succeed [20]. Resilience provides an answer to this question. It refers to a system’s ability to absorb disturbances and reorganize itself to maintain essential functions, structure, identity, and feedback. Resilience encompasses four key aspects: tolerance, resistance, instability, and chaos [21]. Compared to organizations with lower resilience, those with higher resilience can strategically respond to external shocks, manage risks, and even achieve growth in the process.

In recent years, scholars have incorporated resilience into innovation research, exploring its impact on digital transformation [22], sector fluidity [23], organizational competitiveness [24], and corporate performance [25]. Building on the concept of innovation resilience, Wu et al. [2] introduced the concept of green innovation resilience. They defined it as the ability of a green innovation system to withstand external shocks, maintain system stability, adapt, recover, and even evolve into a higher functional state. Green innovation resilience emerges from theoretical reflections on the dynamic stability of innovation systems. Traditional innovation research has often been constrained by the efficiency–output paradigm (e.g., patent numbers, Research and Development (R&D) investment), overlooking system sustainability under complex environmental disturbances. The development of green innovation resilience is a dynamic process of evolution and self-adjustment, supported by capabilities such as recognition, response, recovery, and renewal [26]. This perspective underscores the core role of green innovation resilience in organizational sustainability and environmental adaptability. As global environmental issues intensify and the dual carbon goals are pursued, green innovation resilience has become a key driver of sustainable development. Thus, this study investigates the factors influencing green innovation resilience, aiming to promote long-term sustainable development by enhancing resilience and providing theoretical and practical guidance for green innovation management.

2.1.2. Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence has profoundly impacted the economy, society, and environment through its widespread application across various sectors. Compared to traditional computing models, AI significantly improves system efficiency and intelligence through its unique capabilities in learning, reasoning, and decision-making [27]. AI has revolutionized not only data processing and problem-solving but has also brought unprecedented technological innovation to many industries [28].

In the field of green innovation, AI’s application is particularly significant. It not only enhances the efficiency of green technology R&D but also accelerates the innovation process, driving advancements in energy management, pollution control, and providing new solutions to global environmental challenges [5,7,29]. Despite AI’s potential in green innovation, current research primarily focuses on its specific applications in environmental protection, energy management, and green technology development [30,31,32,33]. The essence of green innovation resilience lies in a system’s ability to maintain stability and recover rapidly under external shocks and uncertainties [2]. AI technology can improve the adaptability and recovery of innovation systems through continuous learning and self-optimization, enabling green technologies to respond swiftly to changes in the external environment or policy shifts, thus maintaining the sustainability and effectiveness of innovation [4]. However, existing literature has yet to systematically explore how AI contributes to green innovation resilience, particularly how it influences resilience under external factors such as policy changes and public concern. This remains a relatively underexplored area. Therefore, it is critical to investigate the mechanisms through which AI enhances green innovation resilience, especially in complex socio-economic and environmental contexts, where AI can play multiple roles in improving the resilience of green technologies.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. The Impact of AI on Green Innovation Resilience

In the context of rapidly advancing digital technologies, AI functions as a transformative tool that can enhance green innovation resilience through multiple pathways. Its key strength lies in strong capabilities in data processing, pattern recognition, and decision support [34], which position AI as an important enabler of green innovation. First, AI can speed up the R&D of green technologies and improve resource allocation, thereby lowering energy consumption and environmental risks [33]. For example, intelligent algorithms help enterprises optimize production processes, reduce material waste, cut emissions of greenhouse gases and conventional pollutants, and raise resource-use efficiency, which improves green innovation efficiency [35]. In China’s manufacturing sector, policies on carbon peaking and carbon neutrality emphasize environmental protection, energy efficiency, water efficiency, and pollution prevention and control in key industries; therefore, AI-driven process optimization can support a broad set of green innovation outcomes rather than only low-carbon improvements. When green innovation is exposed to external changes or policy adjustments, AI can help enterprises respond quickly by processing real-time information and generating more accurate forecasts. This capacity can lessen the adverse effects of shocks on the innovation system and strengthen recovery and adaptability. In addition, AI enables enterprises to refine innovation strategies continuously under shocks by relying on deep learning and self-optimization, which supports the long-term development of green technologies. AI can also facilitate cross-sector integration among energy, environment, and manufacturing, generating new solutions for green innovation and further reinforcing the resilience of green innovation activities [36]. Taken together, AI’s intelligent functions and self-optimization features can improve the adaptability and innovative capacity of green innovation systems and enhance overall performance. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

AI positively impacts GIR.

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Industrial Structure Upgrading

Industrial structure upgrading is widely regarded as a key channel through which AI can influence green innovation resilience, yet prior research often measures it as a single construct and may therefore overlook important internal differences. To capture this heterogeneity, this study distinguishes two dimensions of industrial structure upgrading, namely advancement and rationalization, and further separates advancement into “quantity” and “quality”. Changes in the quantity and quality of industrial structure advancement correspond to the notions of creative accumulation and creative destruction in innovation theory [37]. A higher share of the tertiary industry, which reflects the quantity dimension, does not fully represent the effects of technological paradigm shifts on green innovation. By contrast, the quality dimension reflects improvements in production factor efficiency and better captures the deeper drivers of technology-intensive development [38]. Industrial structure rationalization, in turn, relates to resource allocation efficiency. In a digital economy, AI can improve coordination along inter-industry linkages, and this type of synergy may strengthen innovation resilience more effectively than proportional shifts alone. This three-part view is consistent with the hierarchical perspective in system resilience research [39]. The quantity dimension supports scale effects, the quality dimension facilitates technological upgrading, and the rationalization dimension improves system coordination. Based on this framework, the study evaluates the roles of the quantity and quality dimensions of industrial structure advancement and of industrial structure rationalization in shaping the impact of AI on green innovation resilience.

The quantity of industrial structure advancement is reflected in the gradual shift in the industrial structure from the primary industry toward the secondary industry, together with the rising predominance of the tertiary industry [38,40]. Such changes increase the relative weight of technology-intensive and innovation-driven industries within the overall industrial system, which helps broaden resource inputs, expand market space, and strengthen financial support for green innovation [41]. As AI promotes industrial scale expansion and facilitates resource integration, it supports the scaling-up of green innovation in larger markets and improves its capacity to cope with risks and adjust to changing conditions [40]. In particular, the continued growth of the high-tech industry has widened the adoption of green technologies across more application areas and strengthened the resilience of the innovation system as a whole.

The quality of industrial structure advancement emphasizes higher technology intensity and greater factor efficiency within industries [38,40]. AI can speed up the growth of technology-intensive and innovative industries by supporting sustained technological progress and encouraging cross-industry integration [42]. It also enables enterprises to pinpoint promising breakthrough areas in green technologies, refine technological pathways and innovation processes, and raise both the efficiency and quality of green innovation through data analysis, pattern recognition, and optimization-based decision-making. As the technical content and added value of green technologies continue to increase [4,5,6,7,8], green innovation becomes better able to withstand economic fluctuations and market shifts, and it can remain resilient under policy uncertainty and competitive pressure [43]. In this way, AI supports a shift in the industrial structure toward more technology-intensive and efficient activities and strengthens adaptability and resilience in complex environments.

Moreover, industrial structure rationalization emphasizes stronger coordination across industries and more efficient resource allocation [44]. With the broader use of AI, enterprises can integrate resources along the industrial chain more effectively and improve the flow of information and technology. AI is especially relevant for resource allocation, as tools such as big data analytics, cloud computing, and machine learning can help reallocate inputs across industries and support green innovation within a more coordinated and orderly industrial system [45,46]. As industrial structure rationalization improves, green technologies are more likely to diffuse across industrial linkages, and innovation activities can become more efficient and effective overall [47]. When external shocks arise, including policy shifts and market volatility, industrial structure rationalization can also strengthen firms’ ability to adjust and can support green innovation resilience and long-term sustainable development. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a.

AI influences GIR through the quantity of industrial structure advancement.

H2b.

AI influences GIR through the quality of industrial structure advancement.

H2c.

AI influences GIR through the industrial structure rationalization.

2.2.3. Threshold Effect of Public Environmental Concern

As environmental issues attract greater attention worldwide, public environmental concern has increased markedly, reflecting stronger public focus on environmental protection and green innovation. When public environmental concern remains at a moderate level, it can provide stronger incentives for enterprises to undertake green innovation, especially in the context of AI applications [48]. With precise data analysis and intelligent decision support, AI enables firms to identify and respond more effectively to societal expectations for green innovation, which helps them adjust to external shocks [49]. A balanced level of public concern also encourages longer-term planning in environmental protection and green innovation, supporting sustained innovation and reinforcing the resilience of corporate green innovation systems. However, overly high public environmental concern may impose excessive pressure on enterprises [50]. Under such pressure, firms may prioritize short-term outcomes and reputational considerations, which can weaken the depth and sustainability of green innovation and reduce the long-run stability and adaptability of innovation systems. Public environmental concern therefore needs to stay within a reasonable range, since excessive attention may distort firms’ investment decisions and strategic choices in green innovation. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

The impact of AI on GIR is subject to a threshold effect of public environmental concern.

2.2.4. Threshold Effect of Environmental Regulation

Environmental regulation is a compulsory government instrument and typically imposes stronger constraints and clearer guidance than public environmental concern [51]. When environmental regulation is relatively weak, enterprises may lack sufficient external pressure to unlock the full potential of green innovation. Although AI can provide technological support and stimulate innovation, its contribution to green innovation resilience may remain limited in the absence of regulatory incentives. As environmental regulation becomes more stringent, enterprises must rely more heavily on innovative technologies to comply with tighter standards [52]. In this setting, AI can help firms respond to new regulatory requirements more effectively and can strengthen the adaptability and resilience of green innovation systems [53]. Stricter environmental regulation can also clarify innovation priorities and development targets for smart technologies [54,55]. Under stronger policy pressure, enterprises are more likely to apply AI to accelerate the development and deployment of green technologies, improving both innovation quality and efficiency [6]. Consequently, AI not only raises the efficiency of green innovation but can also support technological breakthroughs, which further enhances green innovation resilience. Therefore, tighter environmental regulation is expected to be associated with stronger green innovation resilience, supported jointly by regulatory pressure and technological innovation. Based on this logic, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

The impact of AI on GIR is subject to a threshold effect of environmental regulation.

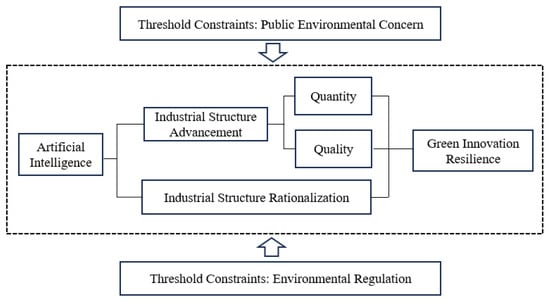

The theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Measurement and Data Source

3.1.1. Explained Variable

The explained variable in this study is green innovation resilience (GIR). According to resilience theory, green innovation resilience refers to the dynamic capacity of a system to maintain functional stability, adapt to changes, and evolve in response to external shocks. The core feature of green innovation resilience lies in a system’s ability to respond to and regulate fluctuations in innovation [56,57]. From a quantitative perspective, green innovation resilience reflects the adaptability of regional innovation systems to fluctuations relative to the overall national trend. Specifically, this is measured by comparing the deviation of each province’s green innovation level from the national average, which helps gauge its buffering capacity in response to environmental changes [2].

To quantify this multidimensional concept, this study adopts the measurement method proposed by Wu et al. [2], constructing a relative resilience index at the provincial level. This index measures green innovation resilience by calculating changes in the number of granted green invention patents in each province. Green patent codes are identified based on the green patent list published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and the volume of granted green invention patents for each province is collected from the National Intellectual Property Administration.

The specific measurement formulas are as follows:

where

- Ri denotes the green innovation resilience of region in year .

- and represent the number of granted green invention patents in region in years and , respectively.

- measures the observed change in granted green invention patents in region from year to year .

- and denote the number of granted green invention patents in the reference region in years and , respectively.

- ∆E captures the change in granted green invention patents in the reference region from year to year , and it is used as the benchmark for predicting the expected patent change for the research object.

To facilitate interpretation, the regional green innovation resilience index is further normalized as follows:

In this expression, refers to the estimated green innovation resilience for region in year . and denote the maximum and minimum values of regional green innovation resilience in the sample, respectively. After normalization, the index ranges from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate stronger resilience and values closer to 0 indicate weaker resilience.

3.1.2. Explanatory Variable

The explanatory variable is AI. The performance of next-generation AI technologies is shaped by multiple conditions, including the surrounding environment and the supporting capacity of complementary technologies [34]. Because single proxy measures, such as industrial robot density, may introduce measurement bias, this study constructs a composite index to capture the level of AI development. The index follows the “technological foundation–knowledge creation–industry transformation” framework and draws on the National Innovation Index Report 2020 and the measurement system proposed by Zhou et al. [58]. Using the entropy method, the index is built from three dimensions. Intelligent Environmental Foundation reflects supporting conditions such as the scale of research institutions, digital infrastructure, and talent reserves. Intelligent Technology Creation captures knowledge production and technology transfer, including scientific papers, patents, software revenue, and new product development. Intelligent Industry Competitiveness represents the operational efficiency of high-tech industries and the intensity of innovation investment. The specific indicators are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

AI measurement indicators.

A larger value of the composite index indicates a higher level of AI development. Data are sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook on High Technology Industry, the China Statistical Yearbook, the China Environment Statistical Yearbook, and various local statistical yearbooks.

3.1.3. Mediating Variables

The mediating variable in this study is the level of industrial structure upgrading, which is measured across two dimensions: industrial structure advancement and industrial structure rationalization.

This variable represents the extent of transformation and upgrading in industrial structures, and therefore requires consideration of both the direction of structural evolution and the efficiency of resource coordination. Accordingly, a dual-channel measurement system is employed, combining industrial structure advancement and industrial structure rationalization to capture the structural changes induced by the integration of AI technologies.

(1) Industrial Structure Advancement (ISA):

Industrial structure advancement plays a critical role in optimizing and upgrading industrial systems by following economic development principles to achieve hierarchical leaps in industrial structure. According to Clark’s law, an increase in the share of non-agricultural industries is often considered an indicator of structural advancement. Common metrics include the industrial structure hierarchy coefficient, the Moore index, and the proportion of high-tech industries. However, traditional approaches primarily focus on changes in industrial scale, which may overestimate quantitative growth and overlook essential factors such as technological intensity and improvements in factor efficiency [38]. In reality, the process of advancement involves two stages: first, the dynamic adjustment of industrial proportional relationships; and second, a systematic leap in total factor productivity. True structural upgrading from scale expansion to efficiency-driven occurs only when high-productivity industries dominate [38]. Drawing on Yuan and Zhu [38] and Xia et al. [40], this study evaluates both the quantitative growth and qualitative improvements of industrial structure advancement, with a focus on the differentiated transmission mechanisms through which AI penetration influences green innovation resilience.

The quantitative aspect of industrial structure advancement (ISA1) is captured by the industrial structure hierarchy coefficient, which reflects the evolution of the three major industries based on relative changes in their shares:

In this formula, represents the proportion of the m-th industry in the GDP of region i at time t, reflecting the evolution from a primary-industry-dominated structure to one dominated by secondary and tertiary industries. This index quantifies the quantitative aspect of industrial structure advancement.

For the qualitative aspect of industrial structure advancement (ISA2), we define it as the weighted product of the proportion of each industry and its labor productivity:

where represents the labor productivity of the m-th industry in region i at time t, and is the number of employees in that industry. An averaging method is applied to eliminate dimensional units, ensuring that the qualitative indicator of industrial structure advancement is unitless. Relevant data are sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook.

(2) Industrial Structure Rationalization (ISR):

Industrial structure rationalization refers to the dynamic process of strengthening coordination and increasing the level of integration among industries. It reflects the degree of coordination between industries and resource efficiency, serving as a measure of the coupling between factor inputs and outputs [19,59]. This study uses the Theil index to measure the degree of industrial structure rationalization in each province. The Theil index is advantageous because it captures structural deviations in both industrial output and employment, while also accounting for differences in the economic status of industries. The formula is:

The industrial structure Theil index reflects the output and employment structures of the three major industries. A value of 0 indicates an equilibrium in the industrial structure, whereas non-zero values indicate deviations from equilibrium and thus an irrational industrial structure.

3.1.4. Threshold Variables

(1) Public Environmental Concern (PEC). Following Zhou and Ding [60], this study measures public environmental concern using the Baidu Index. Specifically, the keyword “environmental pollution” is selected, and the daily average number of searches for this term is used as a proxy for public environmental concern [60]. Moreover, the keyword “environmental pollution” is used because it captures a broad range of environmental issues in public discourse and provides a stable and representative search pattern in the Baidu Index, while combining multiple keywords may introduce noise and reduce measurement consistency.

(2) Environmental Regulation (ER). Building on Guo et al. [61], this study uses the ratio of industrial pollution control expenditure to industrial added value to measure environmental regulation. On the one hand, industrial pollution control expenditure directly reflects measures taken by governments and enterprises to improve environmental quality, indicating the strength of environmental regulation. On the other hand, by normalizing this expenditure against industrial added value, differences in regional and industrial scale are taken into account, providing a more objective evaluation of regulatory intensity. This method is easy to implement and has strong policy relevance, helping to assess how environmental regulation affects industrial development. Data on industrial pollution control expenditure and industrial added value are sourced from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook and the China Statistical Yearbook.

3.1.5. Control Variables

(1) R&D Intensity (RI). R&D intensity is widely used to reflect a region’s innovation capacity. Higher RI can help enterprises adjust to external shocks and recover more quickly, which supports the development and diffusion of green technologies. In this study, RI is measured as the ratio of internal R&D expenditures to regional GDP for each province, and its relationship with green innovation resilience is examined. Data are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook.

(2) Industrialization Level (IL). Industrialization level is often linked to stronger technological capability and higher production efficiency, which can reinforce green innovation and system resilience. A higher IL may also promote the transformation and application of green technologies and improve industries’ responsiveness to environmental and sustainability requirements. This study measures IL by the ratio of industrial output value to GDP for each province and evaluates its effect on green innovation resilience [62]. Data are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook.

(3) Human Capital Level (HCL). Human capital is a key input for innovation, especially for technological R&D and implementation. A more skilled workforce can enhance firms’ innovation capacity, support the development and adoption of green technologies, and strengthen the resilience of the innovation system. This study measures HCL as the ratio of higher education graduates to the total population in each province and tests its effect on green innovation resilience [19]. Data are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook.

(4) Technology Market Level (TML). Technology market activity is an important driver of technological innovation and can contribute to green innovation resilience. A more developed technology market facilitates the commercialization and diffusion of new technologies, which improves the stability and adaptability of the green innovation system [63]. This study measures TML by the ratio of technology transaction value to GDP for each province and analyzes its effect on green innovation resilience. Data are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook.

(5) Tax Burden Level (TBL). Tax burden influences firms’ incentives to invest in innovation and technological R&D [64]. A moderate TBL may encourage R&D spending and support green innovation resilience, whereas an excessive burden can weaken innovation incentives and reduce the system’s responsiveness. This study measures TBL as the ratio of tax revenue to GDP for each province and examines its effect on green innovation resilience. Data are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook.

3.2. Selection of Econometric Models

This study uses SPSS 25.0 to address missing values in the dataset by employing linear trend interpolation for data imputation. For model selection in the panel data analysis, STATA 15.0 software is used, and both the F-test and the Hausman test are applied to identify the most suitable model for the data structure. The analysis reveals the presence of heteroscedasticity and serial correlation in the panel data, common challenges in econometric analysis that can bias estimates if unaddressed. Tests confirm significant heteroscedasticity (χ2(30) = 226.11, p < 0.001) and serial correlation (F(29, 234) = 3.42, p < 0.01), which may compromise the reliability of standard estimators. To address these issues, this study adopts feasible generalized least squares (FGLS). The FGLS method improves the consistency and efficiency of the estimates by adjusting for heteroscedasticity and serial dependence in the data, ensuring that the regression results are robust and reliable. This approach provides credible empirical evidence on the impact of AI on green innovation resilience.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the descriptive statistical analysis for the variables GIR, AI, RI, IL, HCL, TML, TBL, ISA1, ISA2, ISR, PEC, and ER. Supplementary descriptive tables reporting the provincial distributions of AI and GIR in 2022, as well as provincial average levels of key variables over 2013–2022, are provided in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Results of the descriptive statistical analysis.

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Baseline Regression

Table 3 reports the regression results for the impact of AI on green innovation resilience.

Table 3.

Regression results of the impact of AI on provincial GIR.

The regression results in Models 1-1 and 1-2 of Table 3 show that the coefficient of AI is positive and statistically significant, indicating that higher levels of AI development are associated with higher levels of green innovation resilience. This association suggests that AI is correlated with stronger adaptability and resilience within green innovation systems.

4.2.2. Robustness Test

To ensure the stability of the baseline regression results, robustness tests are conducted from four perspectives.

(1) Instrumental Variables Method. Following Luo [22], the one-period lag of AI is used as an instrumental variable for current AI, and a two-stage least squares regression is employed to address potential endogeneity.

(2) Difference-in-Differences (DID). The DID method is used to mitigate potential endogeneity by identifying the net effect of AI-related policies on green innovation resilience [65]. The central and western regions are treated as the experimental group, the eastern region as the control group, and the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan issued by the State Council in 2017 is used as an external policy shock to construct the DID model.

(3) Sample Deletion. To reduce the influence of administrative particularities and extreme economic gradients, four economically developed municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing) and four less developed autonomous regions (Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Xinjiang, Ningxia) are excluded from the sample, and regressions are re-estimated using the remaining subsample.

(4) Winsorization. To minimize the influence of outliers, key variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles before regression [2].

The results of the robustness tests, presented in Table 4, show that AI continues to have a significant and positive impact on green innovation resilience across all specifications, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Table 4.

Results of robustness tests.

4.3. Mediation Effect Regression Results Analysis

4.3.1. The Mediation Effect of Industrial Structure Advancement

To assess the mediation effect of industrial structure advancement, this study separates it into quantitative and qualitative dimensions. For the quantitative dimension, we estimate three equations. We first examine whether AI affects the quantitative dimension of industrial structure advancement, then test whether the quantitative dimension influences green innovation resilience, and finally include both AI and the quantitative dimension in the same model to evaluate their joint effects on green innovation resilience (Models 2-1, 2-2, and 2-3). We apply the same procedure to the qualitative dimension by estimating the corresponding three models (Models 3-1, 3-2, and 3-3). Table 5 reports the results.

Table 5.

Regression results of the mediation effect of industrial structure advancement.

In Model 2-1, AI shows a positive and significant effect on the quantitative dimension of industrial structure advancement (β = 0.192, p < 0.01). Model 2-2 indicates that the quantitative dimension is positively associated with green innovation resilience (β = 0.852, p < 0.01). When AI and the quantitative dimension are entered together in Model 2-3, the quantitative dimension remains significant (β = 0.678, p < 0.01), and AI also remains significant (β = 0.356, p < 0.05). This pattern suggests partial mediation, and thus Hypothesis H2a is supported. Overall, the evidence indicates that AI strengthens green innovation resilience partly by improving the quantitative dimension of industrial structure advancement.

For the qualitative dimension, Model 3-1 shows that AI significantly increases the qualitative dimension of industrial structure advancement (β = 0.539, p < 0.01). Model 3-2 further shows that the qualitative dimension is positively related to green innovation resilience (β = 0.142, p < 0.05). In Model 3-3, the qualitative dimension remains weakly significant (β = 0.109, p < 0.1), and AI remains significant (β = 0.427, p < 0.01), which also indicates partial mediation. Hypothesis H2b is therefore supported, suggesting that AI enhances green innovation resilience partly through the qualitative dimension of industrial structure advancement.

We further verify these mediation effects using the Bootstrap method with 5000 replications and a 95% confidence interval. The confidence intervals are [0.030, 0.681] for the quantitative dimension and [0.009, 0.187] for the qualitative dimension. Because neither interval includes zero, both mediation effects are statistically significant.

4.3.2. The Mediation Effect of Industrial Structure Rationalization

To evaluate the mediation effect of industrial structure rationalization, we estimate three models. We first test whether AI affects industrial structure rationalization, then examine whether industrial structure rationalization is associated with green innovation resilience, and finally include both AI and industrial structure rationalization to assess their joint effects on green innovation resilience (Models 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3). The results are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Regression results of the mediation effect of industrial structure rationalization.

Model 4-1 shows a significant negative relationship between AI and the industrial structure rationalization index (β = −0.311, p < 0.01). Because a higher value of this index indicates a larger deviation from an equilibrium industrial structure, the negative coefficient suggests that AI is linked to lower structural deviation and more efficient resource allocation. Model 4-2 indicates that industrial structure rationalization has no significant effect on green innovation resilience (β = −0.283, p > 0.1), implying that coordination improvements may not translate into stronger resilience in the short run. In Model 4-3, AI remains positively and significantly associated with green innovation resilience (β = 0.476, p < 0.01), while industrial structure rationalization remains insignificant (β = −0.031, p > 0.1). Therefore, Hypothesis H2c is not supported.

One possible explanation is the time-lag feature of industrial structure rationalization [44,47]. Coordination adjustments typically occur gradually, and the effects of AI may not be fully captured by changes in industrial structure rationalization within the sample period, which weakens the expected mediating role. In addition, constraints on inter-regional factor mobility may limit AI’s ability to improve cross-regional resource allocation, making it harder for structural optimization to translate into higher system resilience and thereby reducing the contribution of industrial structure rationalization.

4.4. Threshold Effect Analysis

4.4.1. Threshold Effect Test

Based on Hansen’s threshold model [66], this study examines the threshold effects of public environmental concern and environmental regulation on the impact of AI on green innovation resilience. The bootstrap resampling method with 500 replications is employed. The results show that both public environmental concern and environmental regulation pass the single-threshold test but fail the multiple-threshold test. The test results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of threshold effect test.

4.4.2. Threshold Regression Results

This study examines the threshold effects of public environmental concern and environmental regulation using the corresponding threshold regression models. Table 8 reports the estimated results.

Table 8.

Regression results of threshold effect.

Model 5-1 indicates that AI has a nonlinear relationship with green innovation resilience as public environmental concern increases, which supports Hypothesis H3. When public environmental concern is below the threshold, the estimated coefficient on AI is 1.718 (p < 0.05), suggesting a significant positive effect on green innovation resilience. After public environmental concern exceeds the threshold, the coefficient falls to 0.568 (p > 0.1) and becomes statistically insignificant. This pattern points to a moderate range in which social supervision complements technological innovation, whereas excessive public environmental concern may weaken the longer-term contribution of AI to green innovation resilience.

Model 5-2 shows a similar nonlinear pattern for environmental regulation intensity, supporting Hypothesis H4. When environmental regulation is below the threshold, the coefficient on AI is 1.267 (p < 0.01), indicating a significant positive effect. Once environmental regulation rises above the threshold, the coefficient increases to 2.077 (p < 0.05), implying that the effect of AI becomes stronger under more stringent regulation. This finding aligns with the Porter Hypothesis, which argues that strict and predictable environmental regulation can induce innovation offsets, and it highlights the co-evolution between policy regulation and technological progress in the AI context.

5. Discussion

This study systematically explores the mechanisms and boundary conditions through which AI drives green innovation resilience, providing new theoretical insights and empirical evidence for green transformation in the AI era.

With regard to Hypothesis H1, empirical evidence shows that AI is positively associated with green innovation resilience, and this relationship proves to be robust across a range of robustness checks, including instrumental variable estimation, difference-in-differences analysis, and sample exclusion. These results are consistent with earlier studies highlighting the role of digital technologies in supporting green innovation and resilience [2,22], as well as research emphasizing AI’s contribution to system resilience [10]. Beyond confirming existing findings, the results indicate that AI enhances green innovation resilience not only through efficiency gains, but also by improving adaptability, recovery capacity, and continuity within innovation systems. The persistence of this effect after excluding municipalities and autonomous regions further suggests that the benefits of AI extend across regions and may support technological leapfrogging in less developed areas.

For Hypotheses H2a and H2b, the analysis indicates that AI affects green innovation resilience through two distinct dimensions of industrial structure advancement, namely quantity and quality. This outcome is in line with prior research on industrial intelligence and structural upgrading [40]. From a quantitative perspective, the diffusion of intelligent equipment and technologies creates scale effects and cost reductions, which facilitate the spread of green technologies and strengthen system resilience. From a qualitative perspective, AI raises total factor productivity and accelerates creative destruction by reallocating resources from less efficient activities toward more innovative sectors, thereby enhancing innovation capacity and adaptability. In contrast, Hypothesis H2c is not supported, as industrial structure rationalization does not emerge as a significant mediating mechanism. This result may reflect time lags in structural coordination processes [44,47] and constraints on cross-regional factor mobility, which limit the immediate translation of coordination improvements into stronger innovation resilience. Together, these findings deepen understanding of the differentiated pathways through which AI-driven structural upgrading influences green innovation resilience.

Regarding Hypotheses H3 and H4, the results reveal asymmetric threshold effects of environmental governance factors on the relationship between AI and green innovation resilience. As noted by Zhou and Ding, different forms of public attention can generate heterogeneous impacts [60]. When public environmental concern remains at a moderate level, reputational pressure encourages firms to strengthen green innovation, reinforcing the positive role of AI in enhancing resilience. However, once public concern exceeds the threshold, stricter disclosure requirements and intensified scrutiny may discourage high-risk green innovation, weakening AI’s positive association with resilience. In contrast, environmental regulation shows a progressively strengthening effect. When regulatory intensity passes a critical threshold, stricter pollution control requirements motivate firms to adopt AI-based monitoring and green technologies, while subsidies and technical standards help reduce uncertainty in AI applications. This pattern supports the Porter Hypothesis in the context of AI [67,68,69] and implies that effective policy design should evolve with technological development, moving from compliance-oriented approaches toward incentives that promote innovation.

In summary, this study goes beyond a conventional linear framework by identifying asymmetric pathways through which AI contributes to green transformation. The effects of AI operate partly through structural upgrading, yet they are also shaped by the threshold characteristics of environmental governance. These findings provide theoretical support and practical guidance for fostering a collaborative green innovation ecosystem based on the interplay among technology, structure, and institutions.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

Using panel data for 30 provinces in mainland China over 2013–2022 (excluding Tibet due to missing observations), this study evaluates the impact of AI on green innovation resilience and examines the underlying mechanisms. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) AI significantly enhances green innovation resilience. This result remains robust across several checks, including instrumental variables, difference-in-differences, sample deletion, and winsorization. The evidence indicates that AI contributes to green technological innovation and environmental sustainability by strengthening the adaptive capacity and resilience of green innovation systems. It also provides cross-regional support for the resilience-enhancing role of digital technologies and extends the technology-driven dimension of green innovation resilience research.

(2) Industrial structure advancement acts as a mediating channel, whereas industrial structure rationalization does not. AI promotes green innovation resilience through both the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of industrial structure advancement. By contrast, the pathway through industrial structure rationalization is not significant, suggesting that coordination improvements have not yet become an effective transmission channel for AI to enhance green innovation resilience. This finding reveals a structural pathway through which AI drives green transformation and offers more fine-grained evidence for understanding the technology–structure coupling mechanism.

(3) Public environmental concern shows a threshold effect in the relationship between AI and green innovation resilience. When public environmental concern exceeds a critical level, the effect of AI on green innovation resilience is no longer significant, implying that public environmental concern needs to be kept within a reasonable range. The result deepens the discussion on how public scrutiny affects innovation systems and highlights the nonlinear influence of public participation in green governance.

(4) Environmental regulation also exhibits a threshold effect. The results indicate a stepwise strengthening pattern, in which stronger environmental regulation beyond a certain threshold amplifies the positive effect of AI on green innovation resilience. This provides new AI-based evidence supporting the Porter Hypothesis and offers policy insights into how environmental regulation and digital technologies can reinforce each other.

6.2. Recommendations

(1) Promote the application of AI to enhance green innovation resilience. Governments and enterprises should give greater priority to AI in green innovation and make full use of its strengths in big data analysis, prediction, and intelligent decision support. These applications can raise the efficiency of green technology R&D and improve adaptive capacity. Governments can further encourage the broader adoption of AI in environmental protection and green technology development, particularly where AI can help stabilize green innovation systems under environmental and market uncertainty. At the same time, policy support should be increased for forward-looking green technology projects and for deeper integration between AI and green innovation.

(2) Promote industrial structure advancement to strengthen green innovation resilience. Governments should intensify support for industrial structure upgrading, with a focus on fostering green industries through technological innovation. AI can facilitate industrial optimization, improve both the quantity and quality dimensions of industrial structure advancement, and help green technology innovation overcome key bottlenecks. Enterprises should expand R&D investment, adopt AI and other frontier technologies, and support the continuous upgrading of green innovation systems.

(3) Guide public environmental concern toward a balanced level to improve the role of AI. Governments and social actors should enhance public environmental awareness while keeping public environmental concern within a reasonable range to avoid negative effects from excessive pressure. Environmental policy promotion and awareness raising should be strengthened to guide the public to participate in green innovation and to enhance environmental understanding. At the same time, public opinion guidance should also reduce the risk of excessive focus on a single environmental issue, so that AI can continue to contribute positively to green innovation resilience.

(4) Strengthen environmental regulation to reinforce AI’s contribution to green innovation resilience. The results suggest that when environmental regulation exceeds a threshold, the positive effect of AI on green innovation resilience becomes stronger. Governments should therefore strengthen environmental regulation and refine relevant policies so that regulatory instruments support green innovation more effectively. Policymakers should also tailor measures across regions and industries and adopt flexible regulatory approaches where appropriate. In addition, governments can guide enterprises to use AI to improve environmental protection technologies, enhance adaptability in green innovation, and strengthen the resilience of innovation systems. Support for environmental innovation should be sustained, including the wider use of AI tools in green technology development to further enhance the resilience of the green innovation system.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides useful insights into the impact of AI on green innovation resilience, it has several limitations. First, the empirical analysis relies on data from China, so future work could broaden the sample to other countries or regions and conduct cross-national comparisons to assess whether the AI–green innovation resilience relationship differs across political and economic settings. Second, this study mainly examines the mediating roles of industrial structure upgrading and the threshold effects of public environmental concern and environmental regulation, and it does not explicitly incorporate other potential determinants of green innovation resilience, such as firms’ technological innovation capabilities or green financing conditions. Finally, because resilience formation is inherently dynamic and unfolds over time, future research could use longer time spans or higher-frequency panel data to produce more detailed and policy-relevant findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y., W.L., S.T. and X.L.; methodology, L.Y. and S.T.; software, L.Y. and S.T.; resources, W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.Y.; funding acquisition, W.L. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72174137; Funding recipient: W.L.), Shanxi Province Basic Research Program (Industrial Development Category) Joint Funding Project (Grant No. 202303011222001; Funding recipient: W.L.), and the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation Project of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 21YJA630060; Funding recipient: X.L.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GIR | Green Innovation Resilience |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| ISA | Industrial Structure Advancement |

| ISR | Industrial Structure Rationalization |

| PEC | Public Environmental Concern |

| ER | Environmental Regulation |

| RI | R&D Intensity |

| IL | Industrialization Level |

| HCL | Human Capital Level |

| TML | Technology Market Level |

| TBL | Tax Burden Level |

Appendix A

This appendix provides additional descriptive information on the sample and key variables to complement the main empirical analysis. Table A1 and Table A2 report the provincial distributions of artificial intelligence (AI) development levels and green innovation resilience (GIR) in 2022, respectively, illustrating cross-provincial variation in the core outcome and explanatory variables. Table A3 presents the provincial average values of AI, GIR, and other key variables over the period 2013–2022, offering an overview of long-run trends and structural patterns. These supplementary tables are intended to enhance transparency and contextual understanding of the data, while the main text focuses on hypothesis testing and causal inference.

Table A1.

Provincial Distribution of AI Development Levels in China in 2022.

Table A1.

Provincial Distribution of AI Development Levels in China in 2022.

| Province | DE | Province | DE | Province | DE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.586 | Zhejiang | 0.442 | Hainan | 0.051 |

| Tianjin | 0.144 | Anhui | 0.208 | Chongqing | 0.165 |

| Hebei | 0.190 | Fujian | 0.206 | Sichuan | 0.308 |

| Shanxi | 0.082 | Jiangxi | 0.167 | Guizhou | 0.095 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.115 | Shandong | 0.399 | Yunnan | 0.131 |

| Liaoning | 0.150 | Henan | 0.234 | Shaanxi | 0.197 |

| Jilin | 0.087 | Hubei | 0.241 | Gansu | 0.071 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.096 | Hunan | 0.246 | Qinghai | 0.089 |

| Shanghai | 0.312 | Guangdong | 0.817 | Ningxia | 0.074 |

| Jiangsu | 0.610 | Guangxi | 0.125 | Xinjiang | 0.069 |

| Province | DE | Province | DE | Province | DE |

| Beijing | 0.586 | Zhejiang | 0.442 | Hainan | 0.051 |

Table A2.

Provincial Distribution of GIR Levels in China in 2022.

Table A2.

Provincial Distribution of GIR Levels in China in 2022.

| Province | DE | Province | DE | Province | DE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.871 | Zhejiang | 0.496 | Hainan | 0.773 |

| Tianjin | 0.027 | Anhui | 0.761 | Chongqing | 0.540 |

| Hebei | 0.579 | Fujian | 0.754 | Sichuan | 0.418 |

| Shanxi | 0.313 | Jiangxi | 0.000 | Guizhou | 0.202 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.830 | Shandong | 0.742 | Yunnan | 0.726 |

| Liaoning | 0.579 | Henan | 0.171 | Shaanxi | 0.497 |

| Jilin | 1.000 | Hubei | 0.841 | Gansu | 0.404 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.671 | Hunan | 0.663 | Qinghai | 0.491 |

| Shanghai | 0.863 | Guangdong | 0.520 | Ningxia | 0.584 |

| Jiangsu | 0.504 | Guangxi | 0.548 | Xinjiang | 0.761 |

| Province | DE | Province | DE | Province | DE |

| Beijing | 0.871 | Zhejiang | 0.496 | Hainan | 0.773 |

Table A3.

Provincial Average Levels of AI and GIR during 2013 to 2022.

Table A3.

Provincial Average Levels of AI and GIR during 2013 to 2022.

| Variables | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIR | 0.254 | 0.482 | 0.162 | 0.528 | 0.425 | 0.539 | 0.349 | 0.543 | 0.510 | 0.571 |

| AI | 0.099 | 0.107 | 0.111 | 0.119 | 0.131 | 0.140 | 0.151 | 0.165 | 0.181 | 0.223 |

| RI | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.012 |

| IL | 0.345 | 0.337 | 0.317 | 0.303 | 0.305 | 0.303 | 0.298 | 0.288 | 0.308 | 0.319 |

| HCL | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.027 |

| TML | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.035 |

| TBL | 0.087 | 0.089 | 0.088 | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.083 | 0.079 | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.064 |

| ISA1 | 2.350 | 2.363 | 2.389 | 2.410 | 2.427 | 2.443 | 2.448 | 2.443 | 2.435 | 2.425 |

| ISA2 | 1.125 | 1.172 | 1.300 | 1.404 | 1.459 | 1.517 | 1.577 | 1.619 | 1.512 | 1.486 |

| ISR | 0.186 | 0.174 | 0.155 | 0.144 | 0.140 | 0.133 | 0.120 | 0.100 | 0.109 | 0.128 |

| PEC | 4.436 | 4.714 | 4.688 | 4.689 | 4.821 | 4.775 | 4.628 | 4.619 | 4.638 | 4.617 |

| ER | 51.984 | 62.180 | 41.324 | 46.325 | 30.571 | 23.777 | 22.965 | 15.531 | 12.661 | 9.450 |

References

- BloombergNEF. Clean Energy Investment Trends Q1 2024; Bloomberg Finance LP: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, C.; Wang, G. The impact of green innovation resilience on energy efficiency: A perspective based on the development of the digital economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 355, 120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halbusi, H.; Al-Sulaiti, K.I.; Alalwan, A.A.; Al-Busaidi, A.S. AI capability and green innovation impact on sustainable performance: Moderating role of big data and knowledge management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sahut, J.M. Artificial intelligence, digital finance, and green innovation. Glob. Financ. J. 2025, 64, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Z. The impact of artificial intelligence on green technology cycles in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R.; Li, Q.; Srivastava, M.; Zheng, Y.; Irfan, M. Nexus between green technology innovation and climate policy uncertainty: Unleashing the role of artificial intelligence in an emerging economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J. The impact of artificial intelligence on green innovation efficiency: Moderating role of dynamic capability. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Can enterprise green technology innovation performance achieve “corner overtaking” by using artificial intelligence? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.J.; Zhu, N. Online public opinion attention, digital transformation, and green investment: A deep learning model based on artificial intelligence. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.; Zhao, X.; Dong, K.; Wang, J.; Sharif, A. Can artificial intelligence technology innovation boost energy resilience? The role of green finance. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhang, W. Green finance: The catalyst for artificial intelligence and energy efficiency in Chinese urban sustainable development. Energy Econ. 2024, 139, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F. Finance with a Purpose: FinTech, Development and Financial Inclusion in the Global Economy; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Mohsin, M. Role of artificial intelligence on green economic development: Joint determinates of natural resources and green total factor productivity. Resour. Policy 2023, 82, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumayli, A.; Mahdi, W.A.; Alamoudi, J.A. Analysis of nanomedicine production via green processing: Modeling and simulation of pharmaceutical solubility using artificial intelligence. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 51, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Hussain, J.; Abass, Q. An integrated analysis of AI-driven green financing, subsidies, and knowledge to enhance CO2 reduction efficiency. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J. How does industrial intelligence affect carbon intensity in China? Empirical analysis based on Chinese provincial panel data. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Gonzalez, E.S. Understanding the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in improving environmental sustainability. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhu, Q. Innovation in emerging economies: Research on the digital economy driving high-quality green development. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Shao, X.; Liu, W.; Kong, J.; Zuo, G. The impact of the pilot program on industrial structure upgrading in low-carbon cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, J.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Approaches for resilience and antifragility in collaborative business ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Deng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H. The impact of digital transformation on green innovation: Novel evidence from firm resilience perspective. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; de Oliveira, R.T.; Rizvi, S. How sector fluidity (knowledge-intensiveness and innovation) shapes startups’ resilience during crises. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2024, 22, e00500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chin, J.Y.T.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Building maritime organisational competitiveness through resource, innovation, and resilience: A resource orchestration approach. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 252, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R.; García-Morales, V.J. The key role of innovation and organizational resilience in improving business performance: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yu, L. Research on the influence mechanism and characteristics of innovation resilience on high-tech industry innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2022, 39, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, F.; Magistretti, S. Artificial intelligence in innovation management: A review of innovation capabilities and a taxonomy of AI applications. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 76–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Machado, I.; Magrelli, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial intelligence in innovation research: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Technovation 2023, 122, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Ma, D. Artificial intelligence and green development well-being: Effects and mechanisms in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Intelligent energy management and operation efficiency of electric vehicles based on artificial intelligence algorithms and thermal energy optimization. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 55, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Adewuyi, O.B.; Luwaca, E.; Ratshitanga, M.; Moodley, P. Artificial intelligence-based forecasting models for integrated energy system management planning: An exploration of the prospects for South Africa. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, T.L.; Pasupuleti, J.; Kiong, T.S.; Koh, S.P.J.; Yusaf, T. Energy management strategies, control systems, and artificial intelligence-based algorithms development for hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 1380–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Feng, S.; Li, K.; Chang, R.; Huang, R. Unveiling the effects of artificial intelligence and green technology convergence on carbon emissions: An explainable machine learning-based approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Chin, T.; Papa, A.; Pisano, P. Artificial intelligence augmenting human intelligence for manufacturing firms to create green value: Towards a technology adoption perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 213, 124013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Song, L. Artificial intelligence adoption and corporate green innovation capability. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, F.; Guo, J.; Hu, G.; Song, Y. Can artificial intelligence technology improve companies’ capacity for green innovation? Evidence from listed companies in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 143, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhu, C. Do national high-tech zones promote the transformation and upgrading of China’s industrial structure? China Ind. Econ. 2018, 8, 60–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Han, Q.; Yu, S. Industrial intelligence and industrial structure change: Effect and mechanism. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y. Can the application of artificial intelligence in industry cut China’s industrial carbon intensity? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 79571–79586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.C.; Laurell, C.; Ots, M.; Sandström, C. Digital innovation and the effects of artificial intelligence on firms’ research and development: Automation or augmentation, exploration or exploitation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Jie, W.; He, H.; Alsubih, M.; Arnone, G.; Makhmudov, S. From resources to resilience: How green innovation, fintech and natural resources shape sustainability in OECD countries. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yuan, W.; Jiang, J.; Ma, T.; Zhu, S. Asymmetric effects of industrial structure rationalization on carbon emissions: Evidence from thirty Chinese provinces. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Zhang, H.; Dai, N.; Song, Y.; Chen, H. Artificial intelligence in sustainable energy industry: Status quo, challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Pu, Y.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Employing artificial intelligence and enhancing resource efficiency to achieve carbon neutrality. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Boamah, V.; Lansana, D.D. The influence of industrial structure transformation on urban resilience based on 110 prefecture-level cities in the Yangtze River. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.R.; Carvalho, L.C. AI-driven participatory environmental management: Innovations, applications, and future prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.; Lu, J.; Ren, H.; Wei, J. The role of AI capabilities in environmental management: Evidence from USA firms. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, S. Artificial intelligence and public environmental concern: Impacts on green innovation transformation in energy-intensive enterprises. Energy Policy 2025, 198, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, L.; Hossain, M.E.; Haseeb, M.; Ran, Q. Unveiling the trajectory of corporate green innovation: The roles of the public attention and government. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Feng, X.; Tian, L.G.; Tu, Y. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation and enterprise performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 68, 105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Dong, H.; Cao, H. The effect of digital economy and environmental regulation on green total factor productivity: Evidence from China. Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 62, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, T.; Liu, B.; Zhou, M. Can digital transformation enhance corporate ESG performance? The moderating role of dual environmental regulations. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, K.; Sun, R.; Wang, T. Can strict environmental regulation reduce firm cost stickiness? Evidence from the new environmental protection law in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Digital technology innovation and corporate resilience. Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 63, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, J. A novel multi-criteria decision making method to evaluate green innovation ecosystem resilience. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, D.; Xia, N. Green development effects of artificial intelligence: Technological empowerment and structural optimization. Mod. Econ. Sci. 2023, 45, 30–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wang, M.; Li, M. Low-carbon policy and industrial structure upgrading: Based on the perspective of strategic interaction among local governments. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ding, H. How public attention drives corporate environmental protection: Effects and channels. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 191, 122486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Meng, X.R. U-shaped relationship between environmental regulation and the digital transformation of the Chinese coal industry: Mechanism and moderating effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, J. Digital finance and green technology innovation: A dual path test based on market and government. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]