Abstract

The cross-fertilization of video games and tourism has expanded in recent years, with digital narratives increasingly shaping real-world travel behavior, yet the mechanisms linking mythological video games to pre-trip travel intention remain underexplored. Using the Chinese mythological game Black Myth: Wukong as a case, this study examines how digital myth narratives relate to overseas audiences’ perceptions of, and travel intentions towards, Chinese tourist destinations in a cross-cultural context. Based on a large corpus of YouTube comments, we integrate topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and interpretable machine learning to identify semantic cues associated with travel intention. The results indicate that multidimensional perceptions elicited by digital myth narratives are associated with a gradual evolution of destination image from cognitive to affective and then intentional. Cultural symbol perception, cross-cultural understanding, aesthetic appreciation, and emotional resonance show positive relationships with travel intention and appear as important predictors in the model. SHAP analysis further suggests a nonlinear threshold effect, whereby the probability that a comment is classified as expressing travel intention increases when overall perception reaches a relatively high level. Embedding the cognition–emotion–intention path within a digital game context, this study provides empirical evidence on destination image and behavioral intention in digital narrative settings and offers implications for cross-cultural communication and sustainable tourism planning.

1. Introduction

In an era where digital media profoundly shapes cultural consumption and travel decisions, digital narrative content is emerging as a key driver influencing real-world travel behavior [1,2]. Within the global social media ecosystem, digital mythological narratives presented through myth-themed games, films, television, and short videos are gradually evolving from entertainment products into new channels for cross-cultural audiences to understand destination cultures, form mental imagery, and spark travel interest [3,4,5]. Particularly noteworthy is the 2024 release of the Chinese myth-themed Triple-A (AAA) game Black Myth: Wukong, which offers a prime example. Media and industry reports indicate the game garnered global attention immediately upon launch, with sales and concurrent players repeatedly breaking records [6,7], cementing its status as one of the most talked-about digital games in recent years. Driven by this digital wave, Shanxi Province—the game’s filming location—experienced a significant “cultural tourism boom” [8]. Visitor numbers to core attractions like the Yungang Grottoes and Yingxian Wooden Pagoda surged over 150% year-on-year [9], with online searches, hotel bookings, and actual visitor traffic all rising significantly [10]. This phenomenon confirms that video games rooted in Chinese mythology generate substantial “traffic diversion effects” in the real world [11], providing a representative cross-cultural case study for exploring how digital mythic narratives translate into tangible tourism behaviors.

Social media platforms exemplified by YouTube integrate visual storytelling, emotional interaction, and community discourse within a single ecosystem [12,13]. On one end, destinations are “visualized and narrativized” through videos [14]; on the other, comment sections feature real-time assessments and emotional expressions regarding risks, convenience, cost-effectiveness, cultural significance, and sustainability [15,16,17]. This creates a dynamic field of quantifiable and modelable “cognitive–emotional–intentional” decision-making chains [18,19]. Audiences first process cultural symbols and spatial imagery presented in the game, generating positive or negative emotional experiences. For some individuals, this manifests as explicit visitation intentions like “wanting to travel to a certain place”. Within the YouTube context dominated by non-Chinese comments (e.g., English), this chain itself carries distinct “cross-cultural” characteristics, offering a unique window to observe how overseas audiences imagine Chinese destinations through digital mythic narratives [20].

Despite progress in relevant fields, significant research gaps remain. First, while studies on social media and tourism behavior have confirmed the influence mechanisms of online content on destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions [21,22,23], most theoretical frameworks are grounded in functional experiences, service quality, or traditional marketing videos [24,25]. They pay scant attention to how digitally mythologized narratives—rich in symbolic meaning and emotional resonance—reshape destination appeal during the pre-trip phase [26]. Second, existing studies on film/game-driven tourism and UGC (User-Generated Content) predominantly employ linear regression or structural equation modeling, presupposing linear relationships between perceptions and intentions [27], while overlooking complex “nonlinear characteristics” and “cognitive thresholds” that may emerge in cross-cultural contexts. Third, while emotional contagion and cross-cultural studies highlight the roles of cultural distance and cultural identity, social media’s emotional amplification and algorithmic recommendation features are also shaping cross-subject, cross-platform emotional resonance [28,29,30,31]. However, systematic quantitative evidence remains scarce regarding whether and how such emotional resonance can translate into actual tourism intent. Particularly, few studies integrate these theories with interpretable machine learning [18], making it challenging to precisely quantify the marginal contribution of each cultural perception dimension to tourism intent. Therefore, a new analytical framework is urgently needed to systematically reveal how digital myth narratives drive cross-cultural tourism intent.

Against this backdrop, digital mythic narratives offer an ideal case study for understanding the coupling mechanism between “cultural transmission—cognitive and emotional processing—tourism intention”. On one hand, their narrative systems combine cultural depth with visual symbolism, capable of stimulating meaning recognition and emotional engagement with Chinese myths, landscape imagery, and religious symbols among diverse cultural groups within the global media context [32]. On the other hand, according to contemporary authenticity theory, cultural experiences are no longer passively consumed “object attributes”, but rather dynamically generated processes encompassing “pre-trip, on-site, and post-trip” phases [33]. Through myth-themed video games and the comment interactions they generate on YouTube, overseas audiences form emotional “presence” and value judgments around relevant landscapes and cultural imagery before ever setting foot in the destination. This pre-travel psychological accumulation constitutes a key antecedent in evaluating destination appeal and visitation intent [34].

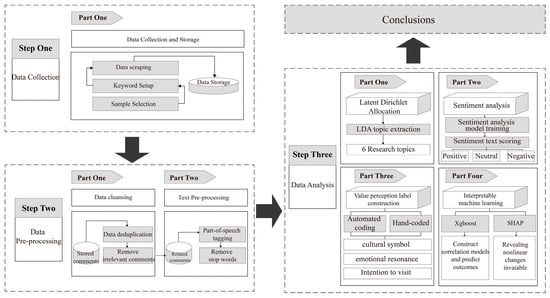

Based on the above issues, this paper attempts to advance research in three aspects: First, using Black Myth: Wukong as a case study, it clearly delineates and quantifies the cross-cultural “cognitive-affective-intentional” chain driven by digital mythic narratives. Second, it innovatively introduces the XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) and SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) explainable machine learning framework, overcoming the limitations of traditional linear models to not only identify key semantic dimensions but also reveal their “nonlinear threshold effects” on tourism intent. Finally, we contextualize the analysis within the mutually embedded relationship between digital mythic narratives and the Shanxi destination, discussing from a sustainable tourism perspective how digital mythic narratives can provide management insights for destination governance and cultural-tourism synergy. Accordingly, this paper utilizes YouTube’s large-scale cross-cultural comments as its core data source. By integrating LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and the XGBoost–SHAP methodology, it systematically uncovers the underlying mechanisms through which digital myth narratives influence latent tourism intentions. The specific research process and technical approach are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

YouTube video data processing flowchart.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Myth Narratives and Cross-Cultural Theoretical Research

In cultural tourism research, “cross-cultural” refers not only to geographical differences in tourists’ origins but also emphasizes cognitive disparities and emotional resonance between tourists and destination cultures in terms of values, symbolic meanings, experiential expectations, and interactive processes [35]. When encountering heterogeneous cultural content, audiences often rely on existing cultural schemas for understanding and categorization [36]. When cultural narratives align with their preexisting values, cognitive load is significantly reduced while emotional engagement increases, thereby enhancing destination image and potential travel intent [37]. This mechanism is particularly pronounced for narrative-centric content. Through the resonance effects of pseudo-social interactions and interest-based communities on social media, emotional involvement and value identification are amplified, making cultural narratives a crucial medium for fostering emotional resonance [38].

The global dissemination of digital mythic narratives is unfolding within this dynamic process. Content centered on mythic figures, narrative conflicts, or philosophical metaphors, when reimagined through modern visual expressions and digital technologies, enhances the “translatability” of symbols. This enables audiences from diverse cultural backgrounds to discover comprehensible and relatable meaning structures within complex cultural connotations [39]. However, the symbolization and commercialization of mythic narratives may also spark debates about “cultural dilution” and “landscape commodification”, thereby exerting bidirectional effects on destination appeal and tourism intent [40]. In other words, digital mythic narratives do not merely amplify cultural appeal; they may also reshape cross-cultural audiences’ judgments of cultural authenticity—a perception widely regarded as a crucial antecedent to cultural tourism intent [41].

From a cross-cultural perspective, audiences exhibit significant cultural heterogeneity in their cognitive-affective structures toward the same destination. Lee et al. found that distinct cultural groups often develop markedly divergent cognitive and affective intentions toward identical destinations [42]. This divergence has been validated through a mixed-methods approach combining UGC and questionnaires, and has been shown to correlate strongly with travel intent. Multilingual online reviews similarly reveal that language serves both as a communication channel and a meaning-making framework. Differences in risk perception, emotional responses, and cultural symbolism across language-specific reviews alter travel expectations and destination appeal [43]. This demonstrates that the “translatability” and “resonance” of cultural narratives jointly determine whether and to what extent travel intent can be successfully stimulated.

The key contribution of cross-cultural theory in cultural tourism lies in elucidating the hierarchical chain structure: “cultural distance-value alignment-emotional response-behavioral intention [44]”. Cultural distance not only influences destination image by moderating risk perception and stereotypical expectations [45], but may also directly impact travel intention [46]. Therefore, the formation of cross-cultural tourists’ intentions is not based on simple judgments of functional attributes but involves a comprehensive evaluation process encompassing cultural understanding, value alignment, and emotional projection [47]. Within this framework, the influence of digital mythic narratives extends beyond mere cultural transmission, directly connecting to the deep mechanisms of tourism behavior [48]. When audiences effectively process cultural symbols within mythic narratives and emotionally resonate with them, this transformation “from cognition to empathy” significantly enhances destination appeal and travel willingness [49].

2.2. Destination Attractiveness and Visit Intent

Destination attractiveness and visit intention are core concepts in tourism behavior research, shaped by the combined influence of cognitive image, affective image, and value assessment [50]. Among these, destination satisfaction is regarded as the key psychological link connecting tourist perceptions, value judgments, and subsequent behaviors [51]. Its mechanism often manifests during the evaluation phase following the conclusion of the “on-site experience [52,53]”. In recent years, extensive research has validated the significant positive correlation between “destination image and behavioral intention” across diverse contexts [50,54], emphasizing the pivotal role of emotional experiences. Findings indicate that highly arousing positive emotions—such as pleasure, awe, and nostalgia—substantially enhance tourists’ preference for and intention to visit a destination, while negative experiences like crowding, noise, or unfair service inhibit the conversion of behavioral intent [55]. In this sense, tourists’ judgments of destination attractiveness can be viewed as the combined outcome of cognitive evaluation and emotional response.

As social media has become a crucial channel for tourists’ “pre-trip intention formation”, the generation of destination appeal and visitation intent has shifted from the “on-site experience” to the “media exposure stage”. Existing research indicates that UGC on social platforms is altering tourists’ cultural expectations and risk perceptions through mechanisms such as “information credibility—emotional response—social endorsement [56]”, thereby influencing their anticipated structure of destination appeal and visitation intent. Particularly in travel videos and media narratives, statistically significant correlations exist between audience emotional responses and interactive behaviors toward virtual scenes and subsequent real tourist traffic [40].

For digital cultural content exemplified by digital myth narratives, this “pre-trip shaping effect” is especially critical. Digital mythic narratives integrate cultural symbols, emotional cues, visual aesthetics, and value imaginings, enabling audiences to construct preliminary mental images of a destination’s culture, nature, and spatial qualities upon encountering the content. Simultaneously, thematic focus, cultural symbols, and emotional expressions in YouTube comments largely reflect audiences’ implicit judgments of a destination’s appeal and latent travel intentions [21]. In other words, the cultural significance, aesthetic impact, or emotional resonance experienced within mythic narratives often internalizes as interest in the destination before actual travel occurs, subsequently influencing whether audiences will incorporate it into future travel decisions [57].

From a sustainable tourism perspective, this image of intent—shaped by pre-trip perceptions and emotional resonance—not only impacts short-term visitor growth but also determines whether a destination can achieve long-term development in alignment with its cultural and environmental carrying capacity [55,58]. Against this backdrop, the cultural authenticity, meaning interpretation, and emotional resonance embodied by digital myth narratives in cross-cultural communication hold promise for expanding new source markets and solidifying the psychological foundation for sustainable tourism development by enhancing destinations’ cultural appeal and perceived value [59].

2.3. Application of Social Media Text Mining in Tourism Research

As digital media increasingly influences tourism decision-making processes, social media has become a critical data source for understanding tourists’ perceptions, emotional responses, and behavioral intentions [60,61]. Compared to traditional questionnaires or interviews, UGC from platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter offers characteristics such as scalability, multilingualism, and real-time accessibility. This enables researchers to capture dynamic shifts in tourist experiences, destination perceptions, and behavioral intentions through online reviews, short videos, and live-stream comments [42,62]. Multimodal texts like online reviews and comment streams not only document tourists’ immediate reactions but also reflect the mental images and behavioral tendencies formed after engaging with digital cultural content [63,64]. This trend has propelled tourism research toward a paradigm shift from “structured surveys” to “open-ended perception mining”, providing a crucial foundation for exploring the intrinsic logic linking cultural narratives, emotional resonance, and travel intentions [25].

In recent years, text mining has evolved from simple word frequency statistics and co-occurrence analysis to integrated frameworks encompassing topic models, sentiment analysis, pre-trained language models, and knowledge graphs. This progression has enabled the extraction of three-dimensional clues—cognition, emotion, and intention—from user-generated content (UGC) [65], revealing the mechanisms underlying image formation and evolution [66]. Research objectives have shifted from “phenomenon description” toward “mechanism explanation and predictive modeling”. For instance, comments under YouTube travel videos can reconstruct thematic lineages of city and scenic area images, providing quantitative foundations for tourism positioning and cultural interpretation [67]. Simultaneously, UGC textual signals have proven effective in predicting tourist volumes, destination demand, and intention trends [25]. When thematic structures and sentiment metrics are jointly input into machine learning models, their explanatory power regarding satisfaction, reputation, and travel intent significantly increases [68]. In cross-cultural and multilingual contexts, text mining further reveals differences among linguistic communities in thematic preferences, sentiment thresholds, and value orientations—differences that influence tourists’ perceptions of destination images and the formation of behavioral intentions [21]. Simultaneously, destination management organizations’ (DMOs) social media content and interaction strategies influence cross-cultural audiences’ cognitive perceptions and emotional attitudes through mechanisms such as information quality, social presence, and pseudo-social interaction [69].

In summary, while existing research has confirmed the predictive value of UGC for tourism intention, the current literature framework still faces challenges in explaining the cross-cultural impact of digital myth narratives. As mentioned earlier, most studies remain focused on the functional experiences of generic marketing videos, failing to delve into how “digital myth narratives”—imbued with deep cultural metaphors—trigger unique psychological processing mechanisms. Furthermore, the review in Section 2.2 and Section 2.3 reveals that mainstream methodologies predominantly rely on linear regression assumptions. This paradigm struggles to capture the potential “cognitive threshold” in intention formation—specifically, the specific intensity of cultural perception and emotional resonance required among audiences to trigger the nonlinear shift from “passive viewing” to “behavioral intention”. Finally, the absence of interpretable machine learning frameworks often limits quantitative validation of the “cognition-emotion-intention” chain to correlational descriptions, failing to reveal the marginal contributions of specific features.

Addressing these theoretical and methodological limitations, this study integrates LDA topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and the XGBoost–SHAP framework to answer three core questions:

RQ1: What key perceptual and emotional patterns does digital mythic narrative evoke across cultures? Do these patterns contain semantic cues related to destination appeal?

RQ2: How do different perceptual dimensions influence potential tourism intent? Does this influence exhibit nonlinearity and cognitive threshold effects?

RQ3: Based on the cognitive-emotional structure of digital myth narratives, how can destination managers optimize the integration of digital content with local experiences to enhance destination appeal and travel intent?

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Preprocessing

3.1.1. Data Sources

This study selected YouTube as the core data source for analyzing the cross-cultural dissemination of Chinese mythological IP (Intellectual Property). As one of the world’s most influential cross-cultural video-sharing platforms, YouTube’s interactive mechanisms authentically reflect how audiences from diverse cultural backgrounds perceive and emotionally respond to cultural content. Particularly in the dissemination of highly narrative and emotionally charged cultural products, comment sections form a “field of meaning negotiation”, often containing expressions of cultural understanding, value judgments, emotional resonance, and travel-related imaginings.

Focusing on the Chinese mythological game “Black Myth: Wukong”, this study collected relevant video comments via the YouTube Data API from December 2022 to May 2025. This timeframe comprehensively covers the critical period from the release of core gameplay footage to the game’s official launch (20 August 2024) and subsequent public discourse. To ensure representativeness and diversity, a stratified sampling strategy was adopted. Forty videos with over 100,000 views and high comment activity were selected as data sources. Sample content spans official trailers, gameplay commentary, story animation clips, and travel vlogs (Table 1), maximizing coverage across diverse audience segments.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of YouTube video data sources.

Addressing the multilingual nature of YouTube comments, this study established a clear language processing strategy. To accurately capture non-native perspectives from “cross-cultural” audiences and avoid semantic biases or cultural context loss introduced by machine translation, non-English comments were not translated. Instead, strict screening criteria were applied: only English comments (including international users expressing views in English) were retained, while Chinese and other language comments were excluded. This strategy leverages English as a global lingua franca to effectively define the international audience. Subsequently, during data cleansing, promotional content, duplicate texts, and anomalous symbols were removed. Regarding ethics and compliance, this study strictly adhered to YouTube’s data usage policies, collecting only publicly available content. To protect user privacy, all user IDs were anonymized before analysis. The final cleansed dataset provides a robust and highly reliable foundation for subsequent theme identification, sentiment feature extraction, and value perception label construction.

3.1.2. Data Preprocessing

YouTube comment texts exhibit characteristics such as multilingualism, fragmentation, and symbolic expressions. To ensure the effectiveness of topic modeling and sentiment analysis, this study systematically performed data cleaning and text standardization on the raw data, primarily involving the following steps:

First, to guarantee data integrity and thematic relevance, comment samples underwent preliminary screening. Empty comments, content containing only emojis or URLs, duplicate texts, and clearly irrelevant advertisements or noise comments were excluded to ensure interpretable text semantics and analytical representativeness. Second, linguistic standardization was performed. All texts were unified to lowercase to eliminate formatting variations. Subsequently, word segmentation and stopword filtering were applied: continuous text was divided into recognizable semantic units, and high-frequency function words like “a”, “an”, “the”, and “with” were removed to reduce noise. To further reduce semantic redundancy and feature dimension sparsity, stemming techniques were applied to merge derived words into their root forms (e.g., “running” to “run”). This minimized semantic dispersion and enhanced clustering and sentiment classification accuracy. Finally, text normalization is performed, including correcting spelling errors, expanding abbreviations, standardizing numerical formats, and converting special symbols and emoticons into standard semantic tags for machine recognition and feature extraction.

Through these steps, non-standard elements and noise in the text are significantly reduced, while semantic consistency and feature density are markedly enhanced. The processed text data provides high-quality input for LDA topic clustering and VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner) sentiment analysis, laying a solid foundation for subsequent machine learning modeling.

3.2. Text Feature Extraction

3.2.1. LDA Topic Modeling

LDA is a probabilistic topic discovery method capable of extracting semantic themes from large-scale YouTube comments. The model assumes each text consists of a mixture of multiple topics, with each topic comprising a set of terms weighted by distinct probabilities. By statistically analyzing co-occurrence patterns of words, LDA infers latent topics from large-scale text data and assigns corresponding topic weights to each document, thereby revealing the perceived focus and semantic hierarchy of the text.

In this study, LDA identifies the semantic dimensions through which overseas audiences construct preliminary perceptions of Chinese culture and destinations when encountering digital myth narratives. This cognitive structure determines subsequent emotional responses and travel intentions, forming the first link in the “cognition-emotion-intention” chain. The LDA model was constructed using Python 3.12’s Gensim library. To ensure reproducibility, key hyperparameters were set as follows: document-theme density (α) and theme-word density (η) were both set to “auto”, enabling the model to automatically learn optimal asymmetric priors based on corpus characteristics. Training iterations were set to 10 to ensure convergence. The model training process included the following steps: First, a document-term matrix was constructed from the preprocessed corpus. Multiple models were then trained across varying numbers of topics (K values). To determine the optimal topic count, the C_V (Coefficient of Variation) consistency metric was employed as the evaluation criterion [68]. The C_V metric combines sliding-window normalized pointwise mutual information (NPMI) with cosine similarity, demonstrating superiority over traditional perplexity metrics in measuring the semantic interpretability of topics. By comparing C_V scores across different K values, the optimal number of topics—balancing semantic interpretability and model stability—is selected as the final parameter setting.

Following model training, high-frequency keywords and representative comments for each theme underwent analysis and manual validation. Themes were named and interpreted based on their semantic characteristics, covering key perceptual dimensions of overseas audiences in cross-cultural communication contexts. LDA not only serves a technical role in semantic induction but also provides the foundational key variables for analyzing how digital myth narratives shape cross-cultural destination imagery. This establishes a structured data framework for subsequent sentiment recognition, value recognition identification, and behavioral intention modeling.

3.2.2. Sentiment Analysis

In the cross-cultural dissemination of digital mythic narratives, emotional responses serve as the pivotal psychological mechanism linking “cognitive perception” to “travel intent”. High-arousal positive emotions—including awe, amazement, and delight—are often regarded as crucial precursors driving cultural interest, cultural affinity, and travel intentions. The visual tension, heroic archetypes, and symbolic conflicts within mythic narratives enable audiences to project emotions onto real destinations during content consumption, thereby enhancing destination appeal.

To capture these emotional cues, this study employed VADER for sentiment analysis of the text. VADER is a hybrid lexicon-based and rule-based analysis tool designed for social media texts. It effectively identifies common informal expressions in comments—such as emoticons, punctuation emphasis, capitalization shifts, and internet abbreviations—making it particularly suited for unstructured, emotionally rich text scenarios like YouTube comments. By weighting lexical sentiment values and contextual modifiers, VADER outputs four sentiment scores for each comment: Positive, Negative, Neutral, and Compound Polarity Score. The compound value comprehensively reflects the overall sentiment orientation, ranging from −1 to +1. To ensure classification accuracy and reproducibility, this study employs VADER’s standard threshold parameters: When compound ≥ 0.05, it is classified as positive sentiment; when compound ≤ −0.05, it is classified as negative sentiment; and when −0.05 < compound < 0.05, it is classified as neutral sentiment. By statistically analyzing the proportion of comments across different sentiment categories and the distribution of compound values, this study delineates the emotional response patterns of overseas audiences when encountering digital myth narratives, visual symbols, and cultural imagery. This analysis not only reveals audience emotional resonance patterns in cross-cultural communication contexts but also reflects emotional consensus and differentiated reception pathways for digital mythic narratives in international settings. Through sentiment analysis, the immediate emotions evoked by digital narratives are transformed into quantifiable variables, providing a crucial intermediate layer for constructing a “cognition-emotion-intention” pathway model.

3.2.3. Value Perception Tagging System Development

To further explore how digital myth narratives shape cross-cultural tourism intentions at the value level, this study constructed a tagging system covering value cognition and tourism intentions based on prior literature review and corpus pre-reading. This system formed a feature set comprising 16 semantic dimensions, serving as input variables for the subsequent XGBoost model (Table 2). Drawing on research in cross-cultural tourism, cultural identity, symbolic consumption, and media effects, this paper categorizes comment content related to destination cognition and value evaluation into the following dimensions: Emotional Resonance (ER), Travel Motivation (TM), Mythological Understanding (MU), Cultural Identity (CI), Religious Culture (RC), Aesthetic Appreciation (AA), Cultural Experience (CE), Social Media Impact (SMI), Curiosity Effect (CE 1), Cultural Symbol (CS), Value Perception (VP), Authenticity Perception (AP), Cultural Connectivity (CC), Cultural Value (CV), Heritage Appeal (HA), and Cross-Cultural Understanding (CCU). These dimensions collectively represent the cultural significance, aesthetic experiences, and behavioral drivers embodied within digital myth narratives.

Table 2.

Examples of comment-level semantic labeling.

In practical implementation, the ER feature is represented by the composite sentiment score calculated using the VADER sentiment analysis tool, reflecting the overall emotional orientation and intensity of comments as a continuous variable. The remaining 15 semantic dimensions are automatically extracted based on keywords and semantic rules. First, relevant literature and typical comment phrases are referenced to construct corresponding keyword lists and fixed collocation dictionaries for each dimension. Subsequently, Python scripts scan all comments line by line. When any expression from a dimension’s dictionary appears in the text, that dimension is marked as 1; otherwise, it is marked as 0. This process generates a set of binary semantic features at the comment level.

The visit intention label is represented by variable y2, whose identification rules are strictly constrained to handle edge cases. y2 is automatically assigned a value of 1 only when a comment simultaneously contains expressions indicating travel behavior (e.g., “visit”, “travel to”, “go to”) and specific Chinese place names or location terms (e.g., “China”, “Shanxi”, “Temple”). To eliminate ambiguity, this study established a “metaphor filtering rule”: texts expressing solely in-game virtual experiences (e.g., “play the game”) or employing ‘journey’ metaphors (e.g., “emotional journey”, “journey to the west” referring to the original novel’s plot) are labeled as 0. This ensures y2 exclusively reflects explicit potential travel intent directed toward the real world. Ultimately, 16 semantic features were input as independent variables and y2 as the dependent variable into an XGBoost classification model to characterize the associative mechanism between digital myth narrative semantics and travel intent.

It is particularly noteworthy that this study exclusively employed an automated coding strategy based on dictionaries and rules, without manual annotation of the large-scale dataset or formal consistency statistical testing. While strict rule-setting partially mitigates ambiguity, purely automated rules may exhibit recognition biases for highly contextual comments containing irony or implicit intentions. This constitutes a primary limitation of this study and points to a key direction for future research: incorporating deep learning models or conducting large-scale manual verification to enhance label accuracy.

3.3. Model Construction and Interpretability Analysis

To systematically examine the influence of digital myth narratives on tourism intent across cultural contexts, this study constructs a behavioral intention prediction framework using a gradient boosting model. First, the topic distribution vectors from the LDA model, VADER sentiment scores, and fundamental metadata of reviews are integrated to form a structured feature matrix, reflecting the multidimensional textual characteristics of cross-cultural reviews. Subsequently, using rule-based extracted tourism intention labels as the target variable, XGBoost was employed for classification modeling after feature matrix construction. XGBoost, with its efficient nonlinear fitting capabilities and strengths in feature interaction identification, is well-suited for revealing complex coupling relationships among perceived characteristics, emotional features, and tourism intention.

The selection of XGBoost over traditional ensemble models like Random Forest or AdaBoost is primarily based on the following considerations: First, as an engineered implementation of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT), XGBoost employs a second-order Taylor expansion of the loss function, achieving higher convergence accuracy compared to AdaBoost, which utilizes only first-order derivatives. Second, its built-in regularization terms (L1/L2) effectively prevent overfitting, making it particularly suitable for the high-dimensional and sparse text data in this study. Finally, XGBoost provides native support for weighting imbalanced data (scale_pos_weight), which is crucial for handling the scarce travel intention samples in this research.

During modeling, all features were standardized before input and split into training and testing sets at an 8:2 ratio. To achieve optimal model performance and prevent overfitting, hyperparameters were systematically tuned using grid search combined with 5-fold cross-validation. The final optimal parameter combination was determined as follows: max_depth was set to 4 to strictly control model complexity; learning_rate was set to 0.05, paired with n_estimators = 200 to achieve smooth convergence; subsample and colsample_bytree were both set to 0.8. Additionally, to further suppress noise interference, the model incorporates strong regularization constraints (reg_lambda = 3.0, reg_alpha = 1.0) and a minimum leaf node weight (min_child_weight = 5). Model performance is evaluated using metrics such as Accuracy, F1-score, and ROC-AUC to ensure robust and reliable predictions.

To enhance model interpretability and theoretical clarity, SHAP analysis was employed to quantify the marginal contribution of features to travel intent. The SHAP method, grounded in game theory-based feature attribution, explains the direction and magnitude of a feature’s positive or negative impact at both global and individual levels. This framework thus quantifies and visualizes the hierarchical relationship between “cognition-emotion-intention”, providing visual evidence for understanding how digital myth narratives influence cross-cultural tourism intent through emotional arousal and cultural meaning construction.

4. Results

4.1. Data Overview

This study collected a total of 40,500 video comments related to “Black Myth: Wukong” on the YouTube platform between December 2022 to May 2025. After text cleaning, duplicate removal, language normalization, and irrelevant content filtering, 35,017 valid comments remained. Further excluding samples lacking semantic features or with unidentifiable tourism intent labels yielded 31,274 comments containing complete features and y2 labels for subsequent XGBoost–SHAP model analysis. Subsequent filtering based on travel-related keywords such as “visit”, “travel”, “China”, “place”, “temple”, and “mountain” identified 4324 comments with potential travel intent, accounting for approximately 8.1% of the total comments.

Time-series analysis revealed an explosive growth in comment volume around the game’s official launch in August 2024, exhibiting a classic media exposure-driven pattern. This indicates that the release of digital content rapidly sparked concentrated discussions among cross-cultural audiences. Semantic analysis showed that comment content evolved from early evaluations of game technical performance and visual effects to deeper themes like cultural symbols, narrative implications, and value interpretations. Numerous comments referenced the original Journey to the West, mythological imagery, literary allusions, and film/TV adaptations, transforming the gaming experience into a process of re-encountering and emotionally resonating with traditional Chinese culture. This interaction demonstrates that Black Myth: Wukong has transcended the entertainment consumption context of traditional gaming products. Its digital mythic narrative has formed a communicative space within the global public sphere, one possessing cultural symbolism, emotional resonance, and potential for value interpretation. As relevant studies indicate, digital media is facilitating a “digital revival” or “recontextualization” of cultural content and narratives [70]. Notably, some commentaries spontaneously link game scenes and mythic imagery to real-world geographical spaces, such as expressions of interest in temples, mountains, natural landscapes, or cultural heritage sites. This “place association” bridging virtual and real spaces semantically reveals a shift from aesthetic awe or cultural curiosity toward latent travel intent, providing clear signals for subsequent thematic identification and behavioral intention modeling.

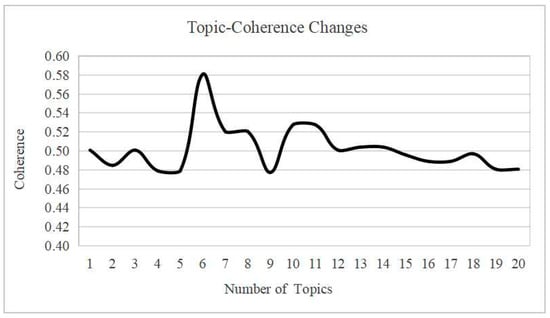

4.2. Perceptual Clustering Analysis Results

To comprehensively identify the primary perceptual structures of overseas audiences within digital myth narratives, this study employs LDA topic modeling based on the cleaned corpus described in Section 3.1. Following the aforementioned methodological framework, the model processes pre-treated English comments as input, sequentially fitting topics with K values ranging from 2 to 20, and evaluates topic coherence using the C_V metric. Results indicate that when K = 6, C_V coherence reaches its global maximum of 0.58 (Figure 2). This setting ensures both semantic distinctiveness and interpretability of themes. Therefore, K = 6 is determined as the final model parameter for subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

C_V coherence-topic number curve.

Based on expert input and LDA model outputs, this study summarizes the model results into the following six themes, identifying 10 representative keywords for each theme (Table 3). The six latent themes ultimately identified are: “Recognition of Cultural Symbols and Mythological Narratives”, “Emotional Expectation and Travel Intention”, “Construction of National Image and Cultural Identity”, “Religious Symbolism and Spiritual Visiting Intention”, “Value Learning and Cross-Cultural Resonance”, and “Natural Aesthetics and Experiential Imagination”. These themes systematically reveal the audience’s multi-layered perceptual structure—from recognizing cultural symbols, emotional anticipation, and value learning, to constructing national image, interpreting religious symbols, and imagining natural aesthetics. They also directly or indirectly point to travel-related interests and intentions in multiple instances. Overall, within the YouTube comment context, Black Myth: Wukong is constructed as a composite narrative medium integrating cultural symbols, emotional triggers, and travel imagination. This demonstrates that beyond entertainment consumption, digital mythic content potentially influences cross-cultural audiences’ attitudes toward and travel intentions for related destinations, providing empirical evidence for understanding how digital mythic narratives promote sustainable tourism.

Table 3.

Results of topic concept extraction for YouTube comments.

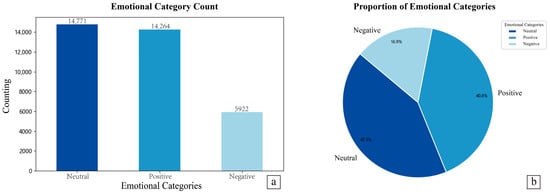

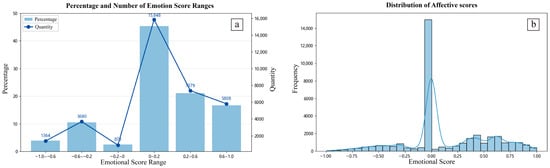

4.3. Sentiment Analysis Results

Based on the compound scores obtained from the VADER-based sentiment analysis tool, this study characterized the overall emotional distribution of the sample comments. Results indicate that sentiment scores predominantly cluster within the 0 to 0.2 range, suggesting that most audiences express attitudes with a neutral to slightly positive emotional tone. After categorizing sentiments according to VADER’s default thresholds, neutral comments accounted for 42.3%, positive comments for 40.8%, and negative comments for only 16.9%, indicating an overall positive sentiment bias (Figure 3). Comparisons across different sentiment intervals reveal that positive sentiment (compound > 0) comments exceed 60% of the total, with a significant proportion persisting above 0.6. This indicates that digital myth narratives consistently evoke strong positive emotional responses across cultural contexts, fostering a degree of emotional aggregation among audiences (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of sentiment categories in YouTube comments: (a) counts and (b) proportions.

Figure 4.

Distribution of VADER sentiment scores: (a) proportions and counts by score interval and (b) overall score histogram.

Further analysis of the relationship between sentiment and latent travel intent reveals that while comments explicitly mentioning travel plans or specific destinations are relatively limited in the corpus, a substantial number exhibit a chained emotional structure: “aesthetic awe-cultural reverence-expression of interest”. These expressions encompass evaluations of visual texture, scene construction, and mythic imagery—including awe, admiration, curiosity, and nostalgia—reflecting audiences’ intense emotional investment in cultural symbols and virtual landscapes. In light of existing tourism behavior theories, which identify high-arousal, positive-valence emotions as precursors to travel intent, this emotional pattern can be interpreted as corresponding to the early stages of intention formation—even when not yet articulated as explicit travel decisions in the text.

From a semantic co-occurrence perspective (Table 4), positive emotions primarily cluster around terms like “visuals”, “culture”, and “mythology”, indicating widespread appreciation for visual aesthetics, cultural imagery, and narrative depth. Negative emotions concentrate on words such as ‘delay’ and “optimization”, revealing concerns among some audiences regarding release timing and version optimization. Further comparison of average sentiment scores across semantic categories reveals that comments containing cultural terms like “myth”, “culture”, and ‘meaning’ consistently exhibit significantly higher emotional scores than those dominated by technical issues. This indicates that content related to cultural symbolism and meaning construction more readily elicits emotional resonance. This characteristic demonstrates that digital mythic narratives exhibit a pronounced “culture-driven emotional effect” in cross-cultural communication.

Table 4.

Examples of VADER-based sentiment scores and classifications for YouTube comments.

Overall, the cross-cultural emotional responses to Black Myth: Wukong in YouTube comments exhibit a complex blend of aesthetic depth and cultural resonance. The emotions evoked transcend simple pleasure or curiosity, forming a multifaceted aesthetic experience that combines cultural depth with visual impact. This emotional structure provides a crucial foundation for subsequent destination interest and travel intent formation.

4.4. XGBoost Model Results

Building upon the extraction of thematic, emotional, and value-based features described above, this study further constructs an XGBoost classification model to evaluate the predictive power of different perceptual dimensions on travel intent. The model uses the 16 semantic variables constructed in Section 3.2.3 as independent variables, with the text label y2 (indicating whether the text contains travel or tourism intent) as the dependent variable.

During model training, the data was randomly split into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio, comprising 25,019 and 6255 samples, respectively. Considering that travel intention samples (y2 = 1) accounted for approximately 4.5% in both sets, significant class imbalance existed. To mitigate class imbalance and prevent model over-bias toward the majority class, this study set scale_pos_weight = 12.74 based on the original sample distribution, assigning a higher weight to the minority class in the loss function. Compared to oversampling methods like SMOTE, this weighting strategy preserves the semantic distribution of the original corpus while enhancing the model’s focus on the minority class without compromising sample authenticity.

Test results indicate that after scanning various classification thresholds, the optimal threshold is 0.80. To comprehensively evaluate the model’s generalization capability and mitigate overfitting risks, Table 5 presents a comparison of performance metrics between the training and test sets. The results show that the model’s metrics on the test set are highly consistent with those on the training set, indicating good model fit and strong generalization ability.

Table 5.

Performance comparison between training and test sets.

Furthermore, to further analyze the model’s specific performance on the minority class (travel intent), Table 6 presents the confusion matrix at the optimal threshold. Among the 6255 samples in the test set, the model successfully identified 109 comments with clear travel intent (True Positives). Calculations based on the matrix data reveal that the model achieves an impressive specificity of 0.980, indicating exceptional robustness in filtering non-target reviews with an extremely low false positive rate. Although the sensitivity stands at 0.388, this is primarily attributable to the relatively strict classification threshold adopted in this study to prioritize precision. In the context of an extremely imbalanced dataset and complex semantic environment, the model adopted a “conservative strategy”, prioritizing the high reliability of identified travel intent over pure coverage.

Table 6.

Confusion matrix of the XGBoost model on the test set.

The coexistence of a high AUC (0.898) and moderate F1 score (0.430) must be interpreted in light of the data distribution characteristics in this study. AUC primarily reflects the model’s ability to rank positive and negative samples, with the high score of 0.898 indicating excellent discrimination capability in distinguishing “presence or absence of travel intent”. Whereas the F1 score is significantly impacted by the extreme scarcity of positive samples (comprising only 4.5%). Under such severe class imbalance, the model inevitably introduces some false positives while attempting to capture minority class samples, thereby limiting improvements in precision and F1 scores. In exploratory text mining research, achieving an F1 score above 0.4 and an AUC close to 0.9 on such an imbalanced dataset demonstrates the model’s successful capture of effective behavioral tendency signals, indicating significant predictive efficacy and research value.

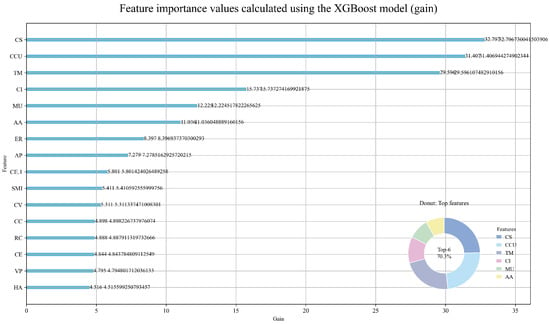

Feature importance results further reveal the relative contributions of different semantic dimensions to travel intent. Ranking based on the gain metric (Figure 5) reveals that CS is the most critical predictor, exhibiting the highest model importance with a gain value of 32.79—far surpassing other features. This indicates that the probability of being classified as “intending to travel” significantly increases when reviews contain distinct mythical symbols, character imagery, or cultural allusions, reflecting the strong appeal of digital myth narratives across cultural audiences. Second and third in importance were CCU and TM, with gain values of 15.73 and 12.23, respectively. This indicates that deepening understanding of cultural content and explicit expression of travel motivation also significantly increase the likelihood of a text being identified as a “potential travel intent” comment. Additionally, features such as CI, MU, and AA played relatively important roles in the model. Notably, the top six features (CS, CCU, TM, CI, MU, AA) collectively accounted for 70.3% of feature importance. Most of these features relate to cognitive processing, cultural meaning construction, and aesthetic experience, indicating that travel intent generation stems not from a single emotion but is jointly driven by cultural symbol recognition, cross-cultural meaning comprehension, and visual aesthetic evaluation.

Figure 5.

Feature importance (gain) of semantic variables in the XGBoost classification model, with the top six features highlighted in the inset plot.

Analyzing both model performance and feature importance distribution reveals that the digital mythic narrative of Black Myth: Wukong not only enhances cultural image perception but also elevates latent tourism interest at the semantic level. On one hand, the high weights of CS, CCU, and TM indicate that positive aesthetic responses to scenes, visuals, and atmosphere increase the probability of reviews being classified as “expressing tourism intent”; On the other hand, reviews containing semantic cues such as cultural identity, cross-cultural understanding, and mythological symbols are more likely to be identified by the model as texts extending “from pure gaming experience to destination imagination and value assessment”. In summary, the formation of tourism intent is not driven by a single emotional response but by a composite mechanism jointly driven by “mythical imagery, cultural cognition, and destination evaluation”.

4.5. SHAP Explanation Analysis

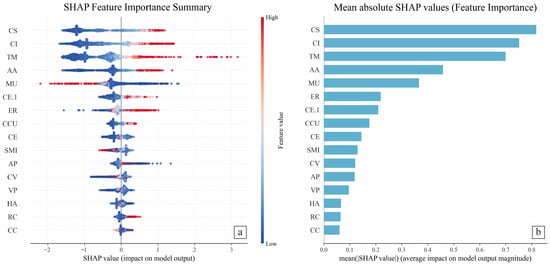

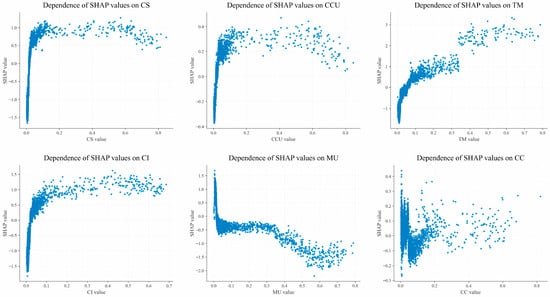

To further elucidate the relationship between the model’s decision-making mechanism and its features, this study employs the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) method to quantify the marginal contribution of different features to predicting tourism intent. First, based on the SHAP beeswarm plot and global importance bar chart (Figure 6), we comprehensively examined the direction and magnitude of each feature’s contribution to the model output. Subsequently, through the SHAP dependence plot (Figure 7), we analyzed the dependency relationship between key features and their SHAP values, thereby identifying the potential “high perception and high intention” conversion zone.

Figure 6.

SHAP-based feature importance. (a) Beeswarm summary plot of SHAP values. (b) Bar chart of mean absolute SHAP values for all features.

Figure 7.

SHAP dependence plots for key predictors (CS, CCU, TM, CI, MU and CC).

In the SHAP beeswarm plot, sample distributions exhibit distinct intensity-dependent patterns. Specifically, for key dimensions like CS, TM, CI, and AA, low-value samples predominantly cluster in regions where SHAP values approach zero or are slightly negative. This indicates that when perception levels are low, their contribution to the model predicting “travel intent” is limited and may even slightly reduce the prediction probability. Conversely, when these features have higher values, samples exhibit a more concentrated distribution in the positive SHAP range. This suggests that stronger cultural symbolism, travel motivation, cultural identity, and aesthetic appreciation significantly increase the probability of a review being classified as “indicating travel intent”. Overall, the pattern of “low values being relatively silent while high values significantly driving” stands out. This suggests that in cross-cultural communication contexts, perceptions on a single dimension must reach a certain intensity before they noticeably propel the formation of travel intent.

At the specific dimension level, high-value samples for CS, AA, and ER are predominantly concentrated in the positive SHAP value range. This indicates that when audiences strongly resonate with the visual aesthetics, contextual atmosphere, and emotional expression of mythic narratives, reviews are more likely to extend from mere game evaluations to expressions of interest in the destination. In the low-perception range, however, the influence of these characteristics on predictive outcomes is relatively limited. High-value samples for CCU and CE also demonstrate significant positive contributions, indicating that deeper audience engagement in understanding cultural connotations and experiencing narrative worldviews enhances their tendency to extrapolate virtual experiences into real-world travel intent. These patterns quantitatively validate the effectiveness of the “cognitive–emotional–intentional” psychological chain, where deep cognitive processing and highly aroused emotional resonance provide critical support for behavioral intent.

The SHAP dependence plot further reveals the nonlinear threshold effect of feature influence. The CS dependence plot indicates that at lower value ranges, SHAP values generally approach zero or remain negative. However, as CS levels gradually increase to the mid-to-high range, SHAP values distinctly shift to positive and exhibit a steep upward trend. This suggests that the driving effect of cultural symbol perception on travel intention is not linearly cumulative but features a distinct “inflection point”. Similar trends emerge for CI and TM features: SHAP values increase with higher feature levels, further validating the positive role of cultural identity and travel motivation in intention formation. The dependency pattern for MU is more complex: SHAP values are predominantly negative at low levels, gradually turning positive as MU increases, but exhibit significant fluctuations in the intermediate range—particularly near MU = 0.5—suggesting this feature’s influence may be modulated by interactions with other characteristics.

Overall, SHAP analysis reveals that digital myth narratives exhibit a significant threshold effect on tourism intention across cultural contexts. When dimensions like cultural symbol recognition, identity recognition, travel motivation, and emotional resonance are low, their impact on travel willingness is limited. However, when multiple perceptions are simultaneously activated and exceed specific intensity thresholds, their positive contribution to model output markedly increases, exhibiting a nonlinear “threshold-like” characteristic. This finding provides crucial micro-level evidence for understanding how digital narratives transform “audiences” into “potential tourists”.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

This study systematically examines the intrinsic connections between Black Myth: Wukong—a Chinese digital mythological narrative—and its ability to stimulate travel intentions across cultural contexts. It achieves this by integrating thematic modeling, sentiment analysis, and explainable machine learning models. Findings reveal that digital mythic narratives transcend mere entertainment texts, simultaneously serving as vital conduits for cultural cognition, emotional resonance triggers, and destination imagination among global audiences. This discovery complements existing research on digital game cultural presence [71], extending its influence from “cultural participation” to “potential tourism behavior [72]”.

Semantically and emotionally, cross-cultural commentary follows a progressive logic: “mythic symbol recognition—construction of Chinese identity and local imagery—reflection on spirit and values—aesthetic appreciation of nature and travel imagination”. This indicates that a significant portion of the audience does not stop at superficial entertainment evaluations when assessing the game. Instead, they actively juxtapose the virtual scenario with the real “China”, demonstrating extended interest. XGBoost–SHAP results further reveal the nonlinear nature of this association: travel intent only exhibits a significant leap when dimensions like cultural symbol perception, aesthetic appreciation, cross-cultural understanding, and emotional resonance reach a certain intensity. This implies that digital mythic narratives can function as either a long-term reservoir for travel intent or, below a certain threshold, remain merely as one-off topics and emotional consumption [73,74].

5.1.1. The Translatability and Emotion-Driven Mechanisms of Digital Myth Narrative Symbols

This study validates the “translatability” of Chinese digital mythic narratives in cross-cultural contexts. Black Myth: Wukong successfully elicits emotional resonance among global audiences through its unique mythic narrative symbols. Sentiment analysis reveals that comments involving “cultural symbols” exhibit significantly stronger positive emotional responses than technical discussions, indicating that symbolic identification is a key factor significantly correlated with travel intent. This process aligns closely with the “symbolic recoding” mechanism in cultural communication theory [75]. Mythic imagery deeply embedded in Chinese cultural contexts is translated through game narratives into symbolically readable texts with cross-cultural resonance. Overseas audiences then recode these texts through their own experiential frameworks, values, and emotional lenses. Uniquely, this emotional resonance transcends abstraction, frequently co-occurring with spatial imagery like “temple” and “mountain”. This indicates that some audiences have directed their emotions toward specific natural and cultural settings, completing a psychological transition from “China in the story” to “China in a real place”. This offers a new perspective on how digital mythic narratives can influence travel intent at the front end.

5.1.2. The Nonlinear Influence of Perceptual Dimensions on Tourism Intentions

The results from XGBoost and SHAP analysis indicate significant nonlinear and threshold characteristics between different perceptual dimensions and tourism willingness. Among all features, variables such as CS, CCU, TM, CI, MU, and AA contributed the majority of the model’s explanatory power, consistent with previous findings. SHAP analysis further reveals a “cognitive threshold effect”: merely low levels of cultural symbol perception or emotional resonance are insufficient to predict higher tourism intention probabilities. Only when audiences develop medium-to-high intensity perceptual experiences regarding the connotations, visual aesthetics, and emotional resonance of mythic symbols does tourism intention leap from “potential possibility” to “identifiable behavioral inclination”. This nonlinear structure theoretically corrects traditional linear assumptions, indicating that digital mythic narratives exert a layered effect on tourism behavior—only high-quality, high-intensity cultural perception combinations serve as the critical switch for predicting behavioral intent. This aligns strongly with the “quality-first” logic emphasized in sustainable tourism [76].

5.1.3. The Transformation Path from Virtual Mythical Scenarios to Sustainable Destination Experiences

Based on the nonlinear structural characteristics of “cognition-emotion-intention” and the critical importance of key features revealed by this study, this paper proposes specific practical pathways for destination managers and cultural content producers. First, model results indicate that CS and AA are the primary drivers of tourism intent. This suggests that the core force propelling intention conversion is not merely IP check-ins, but rather the combined effect of “mythical imagery—cultural understanding—aesthetic atmosphere”. Therefore, when attracting gaming traffic, destinations should transcend superficial visual replication. Instead, they should systematically design tour experiences that resonate with the game’s narrative logic, focusing on elements frequently perceived in the game with high gain value (e.g., details of ancient architecture, specific landscape aesthetics). This approach satisfies audiences’ deep-seated expectation for a “sense of mythic presence” and constructs a narratively coherent experiential space.

Second, given that CCU ranks as the second most important feature in the XGBoost model, overseas audiences’ comprehension of cultural connotations directly impacts conversion rates. This indicates that mere landscape display is insufficient to retain international visitors; destinations must prioritize enhancing multilingual guided tours and in-depth cultural interpretation systems. Through “accessible and relatable” cultural translation, we lower cognitive barriers and cultural discounts in cross-cultural communication. This helps overseas visitors transform their initial curiosity about the game into a deeper appreciation and respect for local cultural heritage, thereby converting traffic into retention.

Finally, the “threshold effect” revealed by SHAP analysis indicates that intent only undergoes significant leaps when perceived intensity surpasses a certain level. Therefore, destination managers should treat the high-exposure period following a game’s release as a critical “pre-trip window”, establishing collaborative mechanisms with game developers and content creators. It is recommended to embed sustainable narratives about ecological conservation and cultural heritage respect into early promotional content—for example, translating in-game combat spectacles into introductions to real mountain ecosystems and mythical traditions. This strategy not only enhances perceived intensity to cross the intention threshold but also guides potential visitors toward responsible tourism attitudes before travel. This approach mitigates risks from excessive commercialization and promotes the long-term sustainable development of the destination’s image.

5.2. Conclusions

This study leverages large-scale YouTube comment data, integrating LDA topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and the XGBoost–SHAP explainable machine learning framework to uncover the associative mechanisms linking Black Myth: Wukong to latent tourism intentions across cultural contexts. The overall findings provide preliminary empirical evidence for understanding the relationship between digital mythic narratives, cross-cultural perceptions, and tourism willingness.

Findings indicate that thematic and sentiment analysis reveal Black Myth: Wukong is constructed within a cross-cultural context as a multi-layered perceptual structure comprising cultural symbol recognition, national and urban image construction, spiritual and religious imagery, value learning, and natural aesthetic imagination. Semantic cues such as “mountain” and “temple” effectively bridge virtual experiences with real-world Chinese destinations. More critically, the model confirms a nonlinear “threshold effect” in tourism intention formation: intention emergence does not result from simple linear accumulation of emotions. Instead, a significant leap occurs only when the perceived intensity of key dimensions—such as CS, CCU, and AA—reaches medium-to-high levels.

This finding indicates that deep cultural resonance and high-quality aesthetic experiences are essential prerequisites for transforming “audience attention” into “visitor intent”. For destination managers, this implies moving beyond superficial IP symbol displays to build spatially coherent experiential systems with narrative continuity. By refining cross-cultural interpretation systems and immersive interactions, destinations can effectively harness the emotional energy generated by digital myths, converting it into sustained interest in local cultural resources and responsible visitation behaviors.

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study demonstrates innovation in data scale and methodological integration, several limitations remain that require addressing in future research.

First, the static textual features constructed from cross-sectional data fail to capture the temporal dynamics of sentiment polarity, thematic focus, and intention expression influenced by game release schedules, public opinion events, and platform topic evolution. Future work should employ time-series modeling and sentiment evolution analysis to observe whether cultural perceptions and travel intent vocabulary exhibit clustering, decay, or shifts around major milestones and explore the coupling between these dynamics and real-world tourism demand fluctuations.

Second, while the XGBoost–SHAP framework demonstrates strong predictive performance and interpretability, its variables primarily derive from text mining and dictionary/rule-based automatic coding—indirect indicators insufficient for comprehensively characterizing individual-level psychological mechanisms. Future research could retain the advantages of large-scale text analysis while incorporating deep learning models or conducting extensive manual validation. Integrating questionnaire surveys, experiments, and interviews could further capture variables such as “perceived cultural distance”, “cultural pride/shame”, “game immersion”, “aesthetic preferences”, and “existing perceptions of China” into the model. This would enable comparisons of pathway differences across cognitive–emotional–intentional chains among groups from diverse cultural backgrounds and identify representative sub-segments of the audience.

Finally, from a broader perspective, with the rise of AIGC (Artificial Intelligence Generated Content), virtual immersive experiences, and multi-platform narrative universes, individual game IPs are increasingly embedded within cross-media, cross-contextual chains. This study captures only one link in this chain, having yet to systematically examine the synergies and tensions between digital myth narratives and their various carriers—such as film and television dramas, short videos, virtual communities, and offline festivals. Future research could employ cross-media comparisons to assess the extent to which such synergies promote responsible cultural consumption and sustainable tourism practices, thereby gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the structural role digital myths play in global cultural dissemination and sustainable tourism development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and R.T.; methodology, Y.X.; software, Y.X. and R.T.; validation, Y.X., Z.G. and X.W.; formal analysis, R.T.; investigation, Y.X.; resources, Z.G.; data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, R.T.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, Y.X.; project administration, Z.G.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Arts Project of National Social Science Fund of China “Research on the Artistic Presentation and Overseas Dissemination of Chinese Classic Mythology IP”] grant number [25BH193]; [Jiangsu Province Degree and Postgraduate Education Teaching Reform Project under grant] grant number [JGKT25_C034]; [Jiangsu Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Programme under grant] grant number [KYCX25_1480].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dubois, L.-E.; Griffin, T.; Gibbs, C.; Guttentag, D. The impact of video games on destination image. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Scholl-Grissemann, U.; Peters, M.; Messner, N. Leveraging minority language in destination online marketing: Evidence from Alta Badia, Italy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, L.-E.; Gibbs, C. Video game–induced tourism: A new frontier for destination marketers. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Shi, S.; Filieri, R.; Leung, W.K. Short video marketing and travel intentions: The interplay between visual perspective, visual content, and narration appeal. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Buhalis, D.; Weber, J. Serious games and the gamification of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Times. Black Myth: Wukong Has Global Gamers Abuzz. China Daily. 2 October 2024. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202410/02/WS66fccd50a310f1265a1c5f4f.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Zheng, Y. Sensational Video Game “Black Myth: Wukong” Ignites Cultural Tourism Boom in N China’s Shanxi. People’s Daily Online. 27 August 2024. Available online: https://en.people.cn/n3/2024/0827/c90000-20210885.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- App2Top. After the Release of Black Myth: Wukong, Tourists Became Interested in China’s Attractions. Available online: https://app2top.com/news/after-the-release-of-black-myth-wukong-tourists-became-interested-in-chinas-attractions-270739.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Yicai. Tourists Throng Real-World Settings Used in Black Myth: Wukong. Yicai Global. 26 August 2024. Available online: https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/tourists-flock-to-real-life-spots-from-black-myth-wukong (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- People’s Daily Online. ‘Black Myth’ Video Game Sparks Tourism Surge in China’s Shanxi. People’s Daily Online. 6 September 2024. Available online: https://en.people.cn/n3/2024/0906/c98649-20215911.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Rainoldi, M.; Van den Winckel, A.; Yu, J.; Neuhofer, B. Video game experiential marketing in tourism: Designing for experiences. In Proceedings of the ENTER22 e-Tourism Conference, Virtual, 11–14 January 2022; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, E.; Mitra, S.; Turel, O. Motivational impacts on intent to use health-related social media. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020, 60, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Amézaga, C. The impact of YouTube in tourism destinations: A methodological proposal to qualitatively measure image positioning—Case: Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Moreno, S.; González-Fernández, A.M.; Munoz-Gallego, P.A.; Casaló, L.V. Understanding engagement with Instagram posts about tourism destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 34, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeloye, D.; Makurumidze, K.; Sarfo, C. User-generated videos and tourists’ intention to visit. Anatolia 2022, 33, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, D.; Spence, P.R.; Van Der Heide, B. Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, I.A.; Stylidis, D.; Andriotis, K.; Thickett, A. Does user-generated video content motivate individuals to visit a destination? A non-visitor typology. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 13567667241268369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Jordan, E.J.; Kline, C.; Knollenberg, W. Social return and intent to travel. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, L. Factors influencing social media users’ continued intent to donate. Sustainability 2020, 12, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. Development of Chinese ethnic minorities animation films from the perspective of globalisation. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Martin-Moreno, O. Topics and destinations in comments on YouTube tourism videos during the Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoycheff, E.; Liu, J.; Wibowo, K.A.; Nanni, D.P. What have we learned about social media by studying Facebook? A decade in review. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Quintero, A.M.D. Understanding the effect of place image and knowledge of tourism on residents’ attitudes towards tourism and their word-of-mouth intentions: Evidence from Seville, Spain. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P. eWOM platforms in moderating the relationships between political and terrorism risk, destination image, and travel intent: The case of Lebanon. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Dong, N.; Hu, F. Tourism demand forecasting using short video information. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 109, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, N.; Leković, M. Video game induced tourism—A critical literature review. BizInfo Blace 2025, 16, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboalganam, K.M.; AlFraihat, S.F.; Tarabieh, S. The impact of user-generated content on tourist visit intentions: The mediating role of destination imagery. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A. Praising pop emotions: Media emotions serving social interests. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.R.; Cárdenas, D.A.; Yang, Y. Perceived cultural distance and international destination choice: The role of destination familiarity, geographic distance, and cultural motivation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Park, J.; Baek, Y.M.; Macy, M. Cultural values and cross-cultural video consumption on YouTube. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z. Affective agenda dynamics on social media: Interactions of emotional content posted by the public, government, and media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, O.; Rusu, C.; Rusu, V.; Matus, N.; Ito, A. Tourist experience considering cultural factors: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly, J.; Canavan, B. The emergence of authenticity: Phases of tourist experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 109, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.; Gruzd, A.; Hernández-García, Á. Social media marketing: Who is watching the watchers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chang, S.-L. User-orientated perspective of social media used by campaigns. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Correia, M.B.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. Instagram as a co-creation space for tourist destination image-building: Algarve and Costa del Sol case studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. In The Political Nature of Cultural Heritage and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 469–490. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Marzuki, A.; Rong, W.; Ran, X. An empirical application of the consumer-based authenticity model in heritage tourism of the George Town historic district, Penang, Malaysia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhua, Y.; Tianyi, C.; Chengcai, T. The Impact of Tourism Destination Factors in Video Games on Players’ Intention to Visit. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 15, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Alam, M.M.D.; Malik, A.; Tarhini, A.; Al Balushi, M.K. From likes to luggage: The role of social media content in attracting tourists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesgin, M.; Taheri, B.; Murthy, R.S.; Decker, J.; Gannon, M.J. Making memories: A consumer-based model of authenticity applied to living history sites. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3610–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Park, S. A cross-cultural anatomy of destination image: An application of mixed-methods of UGC and survey. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Udomwong, P.; Fu, J.; Onpium, P. Destination image analysis and marketing strategies in emerging panda tourism: A cross-cultural perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2364837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Isa, S.M.; Yao, Y.; Xia, J.; Liu, D. Cognitive image, affective image, cultural dimensions, and conative image: A new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 935814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Fang, T.; Wang, H.; Tang, G.A. How does cultural distance affect tourism destination choice? Evidence from the correlation between regional culture and tourism flow. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 166, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]