Visual Quality Assessment of Rural Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Analysis and Subjective Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Participant Selection

2.3. Image Acquisition

2.4. Eye-Tracking Experiment

2.4.1. Experimental Equipment and Venue Selection

2.4.2. Eye Movement Indicator Selection

2.5. Subjective Questionnaire Evaluation

2.5.1. Landscape Characteristic Factor Selection

2.5.2. Questionnaire

2.6. Experimental Procedure

- (1)

- Preparation stage: This stage included checking and calibrating the eye-tracking device, laptop computer, and other experimental equipment; guiding participants to be seated; and explaining the complete experimental procedure and precautions clearly and concisely.

- (2)

- Experimental stage: This stage included two components, eye movement data collection and subjective questionnaire evaluation. First, after wearing the eye-tracking device, participants viewed 2 warm-up images presented by the projector, and then viewed 54 experimental images played in random order, with each image displayed for 8 s, separated by 2 s blank screens to eliminate visual aftereffects. After completing the eye movement task, participants were guided to the laptop computer to complete the scenic beauty and landscape characteristic factor evaluation questionnaire for the samples.

- (3)

- Conclusion stage: After participants completed all experiments, they were thanked and given small gifts, and then they were guided to leave.

2.7. Data Analysis Methods

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Eye Movement Data Analysis

3.1.1. Analysis of Eye Movement Indicator Values for Different Photographs

3.1.2. Analysis of Eye Movement Indicator Differences Among Different Rural Types

3.2. Analysis of Subjective Perception Data

3.2.1. Analysis of Scenic Beauty Evaluation Results

- (1)

- Analysis of High Scenic Beauty Samples

- (2)

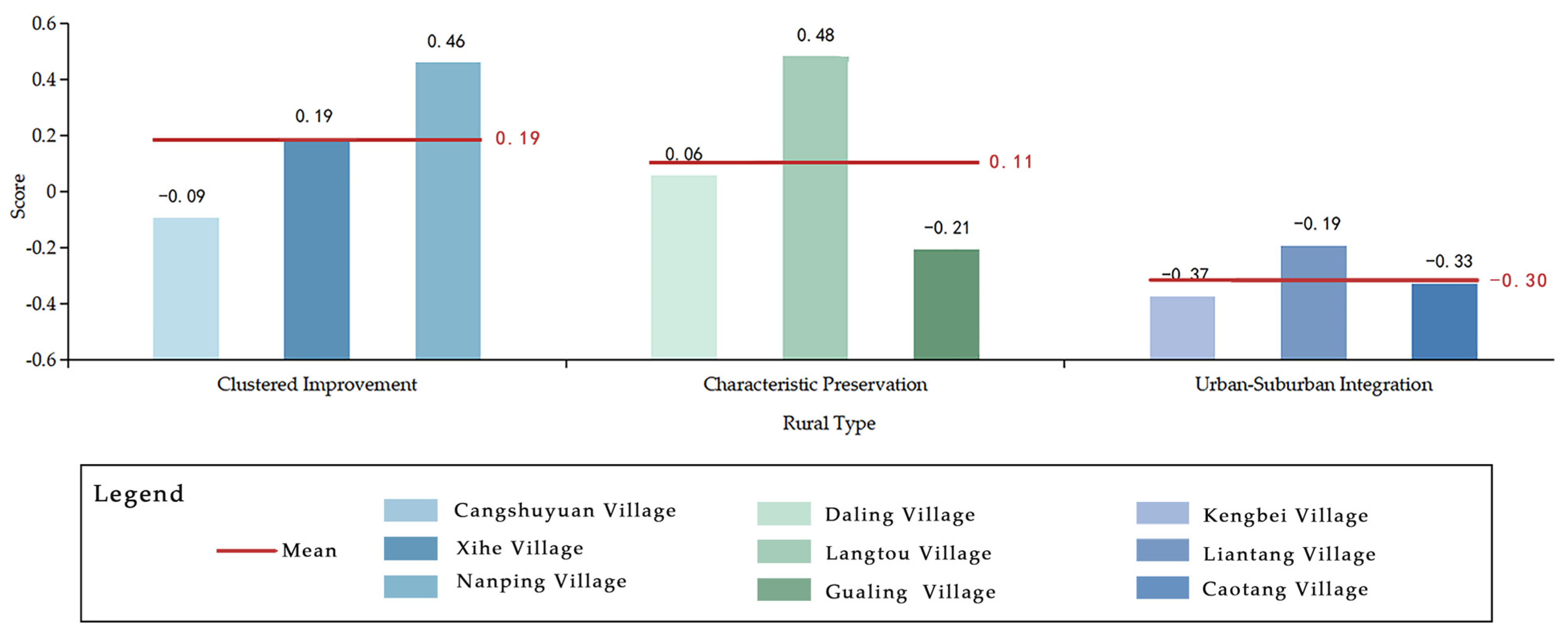

- Scenic Beauty Analysis of Different Rural Types

3.2.2. Landscape Characteristic Factor Evaluation Results Analysis

- (1)

- High Landscape Characteristic Factor Sample Analysis

- (2)

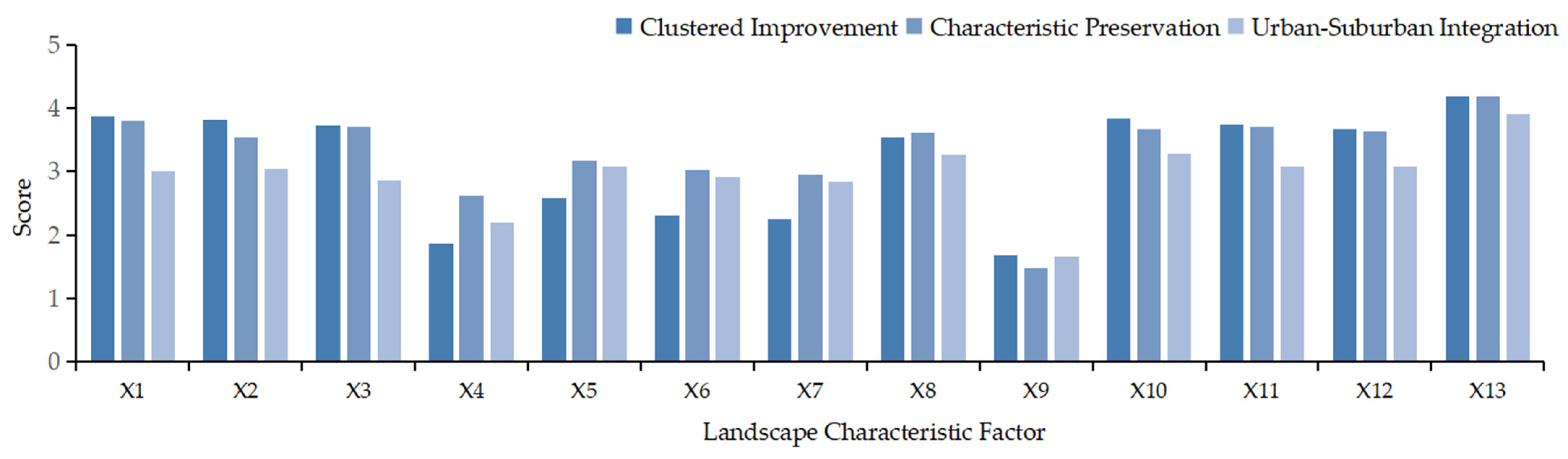

- Landscape Characteristic Factor Analysis of Different Rural Types

3.3. Correlation Analysis and Regression Analysis Between Objective and Subjective Measures

3.3.1. Correlation Analysis and Regression Analysis of Eye Movement Indicators and Scenic Beauty

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis and Regression Analysis of Landscape Characteristic Factors and Scenic Beauty

3.3.3. Correlation Analysis and Regression Analysis of Landscape Characteristic Factors and Eye Movement Indicators

- (1)

- Regression analysis of landscape characteristic factors and total fixation count: Using eight landscape characteristic factors (X5, X6, X7, X8, X10, X11, X12, and X13) as independent variables and total fixation count as the dependent variable for multiple stepwise regression analysis, the results in Table 12 show that only two landscape characteristic factors, X6 (preservation integrity of architectural style) and X12 (landscape element richness) (R2 = 0.368), significantly influenced total fixation count.

- (2)

- Regression analysis of landscape characteristic factors and total fixation duration: Using seven landscape characteristic factors (X5, X6, X7, X8, X11, X12, and X13) as independent variables and total fixation duration as the dependent variable for multiple stepwise regression analysis, the results in Table 12 show that only two landscape characteristic factors, X6 (preservation integrity of architectural style) and X12 (landscape element richness) (R2 = 0.48), significantly influenced total fixation duration.

- (3)

- Regression analysis of landscape characteristic factors and total saccade duration: Using eight landscape characteristic factors (X5, X6, X7, X8, X10, X11, X12, and X13) as independent variables and total saccade duration as the dependent variable for multiple stepwise regression analysis, the results in Table 12 show that only three landscape characteristic factors, X5 (building texture), X6 (preservation integrity of architectural style), and X12 (landscape element richness) (R2 = 0.428), significantly influenced total saccade duration.

- (4)

- Regression analysis of landscape characteristic factors and pupil diameter enlargement count: Using eight landscape characteristic factors (X1, X2, X3, X4, X6, X7, X10, and X12) as independent variables and pupil diameter enlargement count as the dependent variable for multiple stepwise regression analysis, the results in Table 12 show that only two landscape characteristic factors, X2 (vegetation coverage) and X4 (water environment) (R2 = 0.233), significantly influenced pupil diameter enlargement count.

- (5)

- Regression analysis of landscape characteristic factors and total blink count: Using four landscape characteristic factors (X10, X11, X12, and X13) as independent variables and total blink count as the dependent variable for multiple stepwise regression analysis, the results in Table 12 show that only X12 (landscape element richness) (R2 = 0.095) significantly influenced total blink count.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

4.1. Discussion

- (1)

- Analysis of Differences Between Eye Movement Behavior and Subjective Perception

- (2)

- Analysis of Eye Movement Behavior and Landscape Characteristic Factors’ Influence on Scenic Beauty

- (3)

- Analysis of Landscape Characteristic Factors’ Influence on Eye Movement Behavior

- (4)

- Eye-Tracking Experiment Optimization and Prospects

- (5)

- Limitations and Prospects of the Study Population

4.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- Eye-Tracking Experiments and Subjective Evaluation Results Show High Consistency

- (2)

- Significant Differences Exist in Visual Quality Among Different Rural Types

- (3)

- Total Saccade Duration is an Important Eye Movement Indicator for Predicting Scenic Beauty

- (4)

- Landscape Characteristic Factors Have Significant Influence on Eye Movement Behavior

4.3. Optimization Strategies

- (1)

- Enhance Color Richness of Rural Landscapes

- (2)

- Enhance Element Richness of Rural Landscapes

- (3)

- Protect Overall Architectural Styles and Enhance Building Textures

- (4)

- Enhance Overall Landscape Visual Quality of Urban–Suburban-Integration Rural Areas

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Village Types | Village Name | Basic Overview of the Village |

|---|---|---|

| Clustered improvement | Cangshuyuan Village | The village is located approximately 50 km from downtown Guangzhou, with convenient transportation. It preserves numerous buildings from the Ming and Qing dynasties, fully showcasing the traditional architectural style of Lingnan villages. In recent years, it has actively promoted cultural tourism development and established a base of flower cultivation. Plans are underway to introduce small-scale horticultural attractions such as courtyard flower displays and potted-plant experiences. |

| Xihe Village | The village is located approximately 10 km from the Conghua urban area and has convenient transportation. With flower cultivation as its primary industry, the village has actively developed modern sightseeing agriculture, leisure agriculture, and educational tourism, creating signature projects such as the “Nine-Mile Flower Street”. Leveraging the platform of the Ten Thousand Flowers Garden, it promotes rural tourism development. The village has been honored with titles including “China’s Beautiful Leisure Village” and “National Key Village for Rural Tourism”. | |

| Nanping Village | The village has a forest coverage rate exceeding 80%, earning it the reputation of a “natural oxygen bar”. It actively promotes eco-tourism, offering Zen-inspired experiences and pastoral leisure activities. Its specialty agriculture draws numerous visitors and is centered on lychee, longan, and green plum fruits. Recent efforts to develop homestays, farm-to-table dining, and specialty agricultural product sales have boosted residents’ incomes. The village has earned multiple honors, including “China’s Most Beautiful Village” and “National Forest Village”. | |

| Characteristic preservation | Daling Village | The village is located approximately 30 km from downtown Guangzhou and ranks among the city’s ten most renowned surrounding ancient villages. Its layout remains remarkably intact, preserving numerous traditional Lingnan-style buildings that form a characteristic “fishbone-pattern” street network. Recognized for its rich historical and cultural heritage alongside pristine natural surroundings, it has been designated a “China Historical and Cultural Village”—the sole recipient of this honor in Guangzhou to date. |

| Langtou Village | Located approximately 40 km from downtown Guangzhou, this village is one of the largest preserved traditional Cantonese settlements in Guangdong Province. It has been included in the “National Register of Traditional Villages in China” and designated as one of the “Sixth Batch of China’s Historical and Cultural Villages”. The village has gradually emerged as a popular destination for rural tourism in Guangzhou due to its rich historical and cultural resources and collection of ancient buildings. | |

| Gualing Village | The village lies approximately 40 km from downtown Guangzhou and stands as one of the city’s oldest existing hometowns of overseas Chinese. It has been included in China’s Traditional Villages Register and designated as both a Guangdong Provincial Historic Village and a Guangzhou Municipal Cultural Heritage Site. The village serves as a living specimen for studying modern defensive architecture, and water–village settlement patterns. Its unique combination of watchtowers, canals, and overseas Chinese heritage is unparalleled in the Pearl River Delta region. | |

| Urban–suburban integration | Kengbei Village | The village is located 15 km from Zengcheng’s urban center and is adjacent to Kengbei Station on Guangzhou Metro Line 21. In recent years, the village has restructured its industrial base, gradually expanding into sectors such as hardware, plastics, and manufacturing. By integrating culture, agriculture, and tourism, it has driven rural industrial development, significantly boosting villagers’ incomes. Furthermore, leveraging the Guangzhou Eastern Intermodal Hub project, the village is accelerating improvements in both rural industries and public services. |

| Liantang Village | The village enjoys convenient transportation, being adjacent to the ring expressway. Currently, it is embracing a new development opportunity—the Guangzhou Eastern Intermodal Hub for Road and Rail Transport has been established in Zhongxin Town, with the village falling within its scope. Positioned as a demonstration project that integrates transportation corridors, hubs, and industries, the hub represents a comprehensive distribution system, a modern logistics platform, and a manufacturing supply chain service platform, providing new momentum for the development of Liantang Village. | |

| Caotang Village | The village is located approximately 30 km from downtown Guangzhou and has a comprehensive infrastructure. Benefiting from the industrial spillover effects of the Economic and Technological Development Zone and the Guangzhou Automobile Corporation Motor base, some villagers engage in non-agricultural work, resulting in an economic structure characterized by a “half-urban, half-rural” profile. Concurrently, traditional agriculture (rice cultivation, floriculture, and fishpond farming) is gradually transitioning toward leisure agriculture and sightseeing/picking activities (strawberry farms and eco-farms). |

Appendix A.2

| Evaluation Criteria | Indicator Definition | 1 Point | 2 Point | 3 Point | 4 Point | 5 Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 Plant species | A collective term for plant categories such as trees, shrubs, herbaceous plants, and vines that constitute specific landscape spaces and possess ornamental or ecological functions. | None or very few plant species | Few plant species | Moderate number of plant species | High number of plant species | Very high number of plant species |

| X2 Vegetation coverage | The percentage of total area occupied by the vertical projection of vegetation within a specific region. | 0–20% | 20–40% | 40–60% | 60–80% | 80–100% |

| X3 Vegetation stratification | The vertical stratification and combination of different plant structures (such as trees, shrubs, herbaceous plants, and groundcovers) within a landscape. | No stratification | Single-layered, with no vertical variation; flat appearance | Few layers, with weak vertical variation; lackluster visual effect | Moderate layering, with some vertical variation; acceptable visual effect | Rich layering, with strong vertical variation; good visual effect |

| X4 Aquatic environment | Indicates the ecological and environmental status of a body of water. | No water present, or severe water pollution | Poor ecological condition, with slight pollution | Moderate ecological condition, with basic aesthetic appeal | Good ecological condition, with relatively harmonious environment | Excellent ecological condition, with unified and harmonious environment |

| X5 Building texture | The texture and organization created by the spatial composition, form, materials, and scale combinations of the building structure itself. | No buildings present, or very poor building texture | Poor building texture | Moderate building texture | Good building texture | Very good building texture |

| X6 Preservation of architectural style | The degree to which historical buildings retain their original characteristics, spatial form, and visual style. | No buildings present, or building architecture in very poor condition | Poor preservation of architectural character | Moderate preservation of architectural character | Good preservation integrity of architectural character | Excellent preservation integrity of architectural character |

| X7 Historical character of buildings | Refers to the unique attributes of architecture that embody and reflect the cultural, technological, and aesthetic characteristics of a specific historical period through its form, materials, craftsmanship, or function. | No buildings present, or buildings lack historical character | Weak expression of architectural/historical character | Moderate expression of architectural/historical character | Good expression of architectural/historical character | Excellent expression of architectural/historical character |

| X8 Road Coordination | Refers to the degree to which a road is integrated visually, ecologically, and functionally with surrounding natural and cultural landscapes, thereby enhancing overall aesthetics and user experience. | No roads present, or very poor road coordination | Poor coordination of roads | Reasonable coordination of roads | Good coordination of roads | Excellent coordination of roads |

| X9 Farmland texture | Refers to the characteristic textures and patterns formed by elements such as the shape and scale of farmland, as well as the spatial arrangement of crops, reflecting regional agricultural production patterns and natural conditions. | No farmland present, or very poor farmland texture, lacking overall aesthetic | Disorganized texture; bland visual effect | Patterned texture with acceptable visual effect, but lacking aesthetic appeal | Clear and regular texture with good visual effect, possessing aesthetic appeal | Clear and artistically rich texture with strong visual impact; highly aesthetic |

| X10 Landscape spatial stratification | Refers to the orderly arrangement of landscape elements to form a three-dimensional visual structure with a clear distinction between foreground and background with a hierarchical order of dominance. | No stratification; lacking depth and dimensionality; poor visual effect | Limited stratification, with weak depth and dimensionality; plain visual effect | Moderate stratification, with some depth and dimensionality; acceptable visual effect | Rich stratification, with strong depth and dimensionality; good visual effect | Very rich stratification, with excellent depth and dimensionality; outstanding visual effect |

| X11 Landscape color richness | Visual diversity created by various natural and artificial elements in a landscape, manifested in light, hue, and color saturation. | Monotonous single color; dull and boring | Limited colors; bland and lacking appeal | Some color variation; harmonious but unremarkable | Rich colors; harmonious, with visual impact | Very rich colors; natural, with strong aesthetic appeal |

| X12 Landscape element richness | The degree of diversity in the types, forms, and functions of the natural and artificial elements that constitute a landscape. | Monotonous elements, lacking diversity | Limited elements; overall relatively plain landscape | Moderate element diversity; overall acceptable landscape visual effect | Moderate element diversity; overall acceptable landscape visual effect | Very rich elements; overall outstanding landscape visual effect |

| X13 Sanitation conditions | Refers to the cleanliness of the landscape space. | Extremely poor sanitation conditions | Poor sanitation conditions | Reasonable sanitation conditions; no evident accumulation of trash | Good sanitation conditions; no trash along sidewalks | Excellent sanitation conditions; very clean and tidy |

Appendix A.3

| Photo Number | Total Fixation Count | Total Fixation Duration (s) | Total Saccade Duration (s) | Pupil Diameter Enlargement Count | Total Blink Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 14.1 | 5.65 | 0.9 | 10 | 1.33 |

| P2 | 16.7 | 6.06 | 0.99 | 25 | 1.67 |

| P3 | 16.3 | 5.49 | 0.98 | 16 | 1.41 |

| P4 | 17.7 | 5.99 | 1.25 | 7 | 2.04 |

| P5 | 17.4 | 6.17 | 1.09 | 26 | 1.93 |

| P6 | 17.6 | 5.89 | 1.19 | 1 | 1.74 |

| P7 | 18.1 | 6.65 | 1.21 | 44 | 1.74 |

| P8 | 16.1 | 6.93 | 1.08 | 4 | 1.96 |

| P9 | 18.7 | 6.51 | 1.17 | 54 | 2.26 |

| P10 | 16.2 | 5.76 | 1 | 32 | 1.78 |

| P11 | 14.5 | 5.57 | 0.9 | 45 | 1.7 |

| P12 | 17.1 | 6.41 | 1.08 | 27 | 2 |

| P13 | 17.2 | 6.53 | 1.06 | 19 | 1.81 |

| P14 | 16.2 | 5.55 | 1.02 | 50 | 1.41 |

| P15 | 16.6 | 6.55 | 1.02 | 13 | 1.52 |

| P16 | 14.2 | 4.81 | 0.95 | 36 | 1.15 |

| P17 | 16.5 | 6.16 | 1.03 | 38 | 1.63 |

| P18 | 17.1 | 6.1 | 1.07 | 3 | 1.22 |

| P19 | 15.1 | 5.35 | 0.94 | 6 | 1.22 |

| P20 | 15.2 | 5.42 | 0.93 | 2 | 1.19 |

| P21 | 13.2 | 5.92 | 0.81 | 17 | 1.41 |

| P22 | 14.6 | 5.6 | 0.94 | 27 | 1.59 |

| P23 | 16.9 | 5.83 | 1.08 | 17 | 1.48 |

| P24 | 14.7 | 5.46 | 0.92 | 21 | 1.48 |

| P25 | 14.2 | 5.22 | 0.86 | 7 | 1.37 |

| P26 | 17.6 | 5.92 | 1.14 | 13 | 2.22 |

| P27 | 13.9 | 5.17 | 0.85 | 3 | 1.3 |

| P28 | 15.0 | 5.69 | 0.9 | 14 | 1.26 |

| P29 | 13.3 | 4.59 | 0.85 | 18 | 1.52 |

| P30 | 13.2 | 5.02 | 0.89 | 11 | 1.52 |

| P31 | 16.1 | 5.77 | 1.06 | 3 | 1.67 |

| P32 | 13.8 | 5.44 | 0.92 | 11 | 1.44 |

| P33 | 11.7 | 4.26 | 0.75 | 9 | 1.3 |

| P34 | 14.9 | 5 | 0.96 | 10 | 1.67 |

| P35 | 15.4 | 5.38 | 1 | 11 | 1.63 |

| P36 | 13.6 | 4.87 | 0.84 | 7 | 1.33 |

| P37 | 14.6 | 5.12 | 0.91 | 4 | 1.26 |

| P38 | 14.2 | 4.81 | 0.93 | 12 | 1.48 |

| P39 | 15.0 | 5.38 | 0.86 | 18 | 1.31 |

| P40 | 14.5 | 5.51 | 0.98 | 21 | 1.44 |

| P41 | 15.5 | 5.31 | 1.01 | 11 | 1.96 |

| P42 | 13.8 | 4.82 | 1.05 | 8 | 1.63 |

| P43 | 15.0 | 4.96 | 1 | 2 | 1.48 |

| P44 | 16.9 | 5.78 | 1.16 | 15 | 1.85 |

| P45 | 15.8 | 5.51 | 0.99 | 16 | 1.44 |

| P46 | 13.6 | 5.36 | 0.87 | 10 | 1.56 |

| P47 | 12.2 | 4.68 | 0.74 | 4 | 1.15 |

| P48 | 12.9 | 4.84 | 0.8 | 7 | 1.59 |

| P49 | 18.5 | 5.84 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.89 |

| P50 | 14.8 | 5.48 | 1.02 | 1 | 1.59 |

| P51 | 14.3 | 4.86 | 0.95 | 5 | 1.7 |

| P52 | 13.4 | 4.95 | 0.88 | 2 | 1.37 |

| P53 | 12.9 | 5.15 | 0.87 | 2 | 1.67 |

| P54 | 12.3 | 4.66 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.44 |

Appendix A.4

| Photo Number | SBE Mean | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | X11 | X12 | X13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | −0.68 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.11 | 1.22 | 3.56 | 3.89 | 3.89 | 2.67 | 1.00 | 2.11 | 2.56 | 2.33 | 3.56 |

| P2 | −0.03 | 3.67 | 3.89 | 3.78 | 3.56 | 3.11 | 3.22 | 3.00 | 3.44 | 1.33 | 3.89 | 3.22 | 3.78 | 3.89 |

| P3 | −0.20 | 3.67 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 3.83 | 3.33 | 3.50 | 3.17 | 3.33 | 3.50 |

| P4 | −0.03 | 4.17 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 4.17 | 4.17 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.17 |

| P5 | 0.31 | 4.17 | 4.33 | 3.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 4.17 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 3.83 |

| P6 | 0.07 | 3.89 | 4.22 | 4.11 | 1.44 | 2.44 | 2.33 | 2.00 | 4.33 | 1.67 | 4.00 | 3.56 | 3.67 | 4.44 |

| P7 | 0.87 | 4.83 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.50 | 4.17 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 2.83 | 1.17 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 |

| P8 | 0.60 | 2.56 | 1.78 | 2.56 | 1.33 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.56 | 4.33 | 1.33 | 3.22 | 3.89 | 3.22 | 4.56 |

| P9 | 1.11 | 4.56 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 3.67 | 3.11 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 3.89 | 2.67 | 4.22 | 4.67 | 4.56 | 4.56 |

| P10 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.00 | 1.17 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.17 | 3.67 | 1.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 4.17 |

| P11 | −0.59 | 3.56 | 3.44 | 3.56 | 4.11 | 1.78 | 1.67 | 1.56 | 3.22 | 2.44 | 2.56 | 2.67 | 3.11 | 4.00 |

| P12 | 0.91 | 4.50 | 4.33 | 4.67 | 1.67 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 4.33 | 1.67 | 4.50 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 4.67 |

| P13 | −0.03 | 4.44 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 3.00 | 4.22 | 4.33 | 4.22 | 3.67 | 1.56 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 4.11 | 4.00 |

| P14 | 0.24 | 4.17 | 3.83 | 4.33 | 4.50 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 1.17 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.33 | 4.50 |

| P15 | 0.68 | 3.78 | 2.78 | 3.56 | 1.33 | 4.33 | 4.11 | 4.11 | 4.22 | 1.33 | 3.44 | 3.78 | 3.67 | 4.44 |

| P16 | −0.82 | 3.22 | 3.22 | 2.78 | 3.33 | 1.67 | 1.56 | 1.44 | 2.11 | 3.00 | 2.67 | 2.56 | 2.56 | 3.22 |

| P17 | 0.02 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 3.83 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 4.17 | 1.00 | 4.17 | 4.17 | 4.00 | 4.33 |

| P18 | 0.26 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.17 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 3.67 |

| P19 | −0.33 | 3.56 | 3.00 | 3.56 | 1.33 | 2.56 | 2.11 | 1.78 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 3.22 | 4.11 |

| P20 | −0.18 | 3.22 | 2.67 | 3.44 | 3.78 | 2.78 | 2.44 | 2.44 | 3.44 | 1.33 | 3.44 | 3.11 | 3.22 | 4.00 |

| P21 | −0.45 | 2.17 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 2.67 | 2.33 | 2.50 | 3.83 |

| P22 | −0.04 | 2.78 | 2.89 | 2.44 | 1.22 | 4.11 | 4.11 | 4.11 | 3.67 | 1.44 | 3.44 | 2.78 | 3.33 | 4.00 |

| P23 | −0.41 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 3.17 | 1.17 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.67 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 4.00 |

| P24 | −0.54 | 2.50 | 2.33 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 2.67 | 1.00 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.50 |

| P25 | 0.19 | 3.44 | 4.11 | 2.78 | 4.44 | 2.78 | 2.22 | 2.22 | 2.67 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.56 | 3.56 | 4.33 |

| P26 | 0.63 | 1.89 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 4.00 | 4.44 | 4.44 | 4.56 | 4.11 | 1.22 | 4.00 | 3.11 | 3.44 | 4.33 |

| P27 | −0.67 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 2.33 | 2.17 | 3.67 | 2.33 | 3.00 | 2.67 | 3.00 | 3.83 |

| P28 | 0.15 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.17 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 3.83 |

| P29 | −0.79 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.67 | 1.22 | 3.78 | 3.67 | 3.56 | 3.11 | 1.22 | 1.56 | 2.00 | 1.78 | 3.78 |

| P30 | −0.66 | 2.83 | 3.67 | 2.50 | 1.17 | 2.50 | 2.33 | 2.00 | 2.17 | 3.83 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.50 |

| P31 | −0.21 | 3.11 | 4.00 | 3.44 | 3.89 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 3.56 | 3.33 | 1.67 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 3.78 | 4.11 |

| P32 | −0.35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.17 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 3.17 | 2.67 | 4.17 |

| P33 | −0.59 | 3.78 | 4.00 | 3.78 | 1.56 | 1.89 | 1.33 | 1.56 | 3.67 | 1.89 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 3.44 | 3.89 |

| P34 | −0.81 | 3.56 | 3.56 | 3.11 | 2.44 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 2.00 | 3.56 | 2.78 | 2.44 | 2.56 | 3.22 |

| P35 | −0.05 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 4.17 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.33 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.17 | 4.00 |

| P36 | −0.23 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.00 | 2.33 | 2.17 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 4.00 |

| P37 | −0.17 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.00 | 1.83 | 1.67 | 1.67 | 2.67 | 1.17 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.67 | 4.17 |

| P38 | −0.36 | 4.33 | 3.78 | 3.89 | 3.33 | 1.67 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 4.00 | 1.56 | 3.78 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 4.22 |

| P39 | −0.62 | 3.22 | 2.67 | 3.00 | 1.22 | 2.67 | 2.33 | 2.11 | 3.56 | 1.11 | 2.89 | 2.89 | 2.78 | 4.33 |

| P40 | 0.27 | 3.89 | 3.44 | 3.56 | 1.22 | 3.89 | 3.44 | 3.56 | 3.89 | 1.22 | 3.56 | 3.78 | 3.67 | 4.22 |

| P41 | −0.52 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.50 | 3.17 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 4.00 |

| P42 | 0.16 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.83 | 3.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 3.33 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 4.00 |

| P43 | 0.23 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.83 | 1.00 | 3.83 | 3.33 | 3.50 | 4.33 |

| P44 | 0.96 | 4.22 | 3.89 | 4.33 | 1.22 | 3.56 | 3.00 | 2.78 | 4.22 | 1.78 | 4.22 | 4.11 | 4.22 | 4.44 |

| P45 | 0.52 | 4.67 | 4.50 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.83 | 1.17 | 4.50 | 4.67 | 4.17 | 4.33 |

| P46 | −0.18 | 4.44 | 4.22 | 4.11 | 4.11 | 2.56 | 2.22 | 2.00 | 3.11 | 1.33 | 3.78 | 3.89 | 3.78 | 3.89 |

| P47 | −0.02 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 3.17 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 4.33 |

| P48 | −0.34 | 3.67 | 4.22 | 4.00 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.44 | 3.78 | 3.67 | 3.44 | 4.33 |

| P49 | 0.70 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.00 | 3.33 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 4.00 | 1.17 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 |

| P50 | 0.71 | 4.22 | 4.89 | 4.44 | 1.22 | 2.33 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 4.11 | 1.56 | 4.44 | 4.22 | 4.11 | 4.44 |

| P51 | 0.00 | 4.33 | 4.56 | 4.33 | 2.44 | 1.56 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 2.00 | 3.44 | 4.22 | 3.56 | 3.78 | 4.11 |

| P52 | 0.34 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 1.33 | 2.67 | 2.33 | 2.67 | 3.83 | 1.67 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 4.50 |

| P53 | 0.50 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 2.83 | 3.83 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.17 | 3.83 | 4.50 |

| P54 | 0.52 | 3.89 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 1.22 | 2.78 | 2.33 | 2.11 | 3.78 | 1.22 | 3.78 | 4.00 | 3.56 | 4.22 |

References

- Zhang, Y.X.; Qi, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.Z. The Strategic Focus and Advancement Path to Building Livable, Workable and Harmonious Villages under the Background of Comprehensive Rural Revitalization. J. Changchun Norm. Univ. 2024, 43, 14–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Su, Y.T. Promoting Rural Construction: Key Issues and Practical Approaches. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 42, 53–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.B. Rural Ecological Revitalization: Overall Objectives, Key Tasks and Promotion Countermeasures. Huxiang Forum 2023, 36, 45–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, X.Z.Y. Documentary Heritage in the Digital Age: Experience and Prospect on the International Protection of Digital Heritage. Lib. Constr. 2024, 6, 122–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J. Integrating Heritage and Environment: Characterization of Cultural Landscape in Beijing Great Wall Heritage Area. Land 2024, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L. Rural Cultural Revitalization and the Protection and Utilization of ICH—Based on Rural Development Data Analysis. Cult. Herit. 2019, 3, 1–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Davies, S.N.G.; Lorne, F.T. Trialogue on Built Heritage and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurkovich, M.; Gyurkovich, J. New Housing Complexes in Post-Industrial Areas in City Centres in Poland Versus Cultural and Natural Heritage Protection—With a Particular Focus on Cracow. Sustainability 2021, 13, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.W. Guiding the Ecological Development of Green and Beautiful Guangdong with Xi Jinping Thought on Ecological Civilization. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 50, 75–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, X. An Aesthetic Approach and Scientific Guidelines for Advancing China’s Rural Greening and Beautification in the New Era. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 5–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.D.; Fu, W.C.; Li, W.; Lin, S.Y.; Dong, J.W. Landscape Visual Evaluation of Qishan National Forest Park Based on GIS and SBE Method. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2015, 30, 245–250. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M.Y.; Gao, F.; Hao, P.Y.; Dong, L. Evaluation of Plant Design of Linear Parks Based on Semantic Differential Method. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2013, 28, 185–190. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Bai, Z.C.; Lv, G.Y.; Tang, X.Q. Visual landscape quality of scenic road: Applying image recognition to decipher human field of view. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 2817–2837. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; An, J.F.; Zhang, J.; Shi, H.Q.; Gao, Y.; Xue, J.Y.; Li, C.H.; Mohi-ud-din, G. Quantitative Evaluation of the View of the Landscape Using a Visibility Analysis Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Chamberlain, B. In Pursuit of Eye Tracking for Visual Landscape Assessments. Land 2024, 13, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.Y.; Sun, M.K.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.D. Research Progress on the Application of Eye Tracking Technology in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 79–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.X.; Lu, B.C.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.X. Research Progress and Application of Eye-Tracking Technology in Built Environment. South Archit. 2025, 6, 33–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Dong, W.H.; Zhang, W.J. Research on Influencing Factors of Built Environment Perception in Neighborhoods: Evidence from Behavioral Experiment. City Plan. 2022, 46, 99–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.K.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhou, J.W.; Li, X. A Tentative Research of Restorative Environmental Evaluation of Community Parks Based on Eye Movement Analysis. South Archit. 2022, 6, 93–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Yin, M.; Cao, L.L.; Sun, S.Q.; Wang, X.Z. Predicting Emotional Experiences through Eye-Tracking: A Study of Tourists’ Responses to Traditional Village Landscapes. Sensors 2024, 24, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.H.; Sun, Y. Using a Public Preference Questionnaire and Eye Movement Heat Maps to Identify the Visual Quality of Rural Landscapes in Southwestern Guizhou, China. Land 2024, 13, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Luo, T.; Wang, Y.Y.; Fan, X.L.; Zhao, C. Study on the Perceptual Features of Urban Landscape Elements Based on Visual Attention and Aesthetic Preference. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.B. Landscape Quality Evaluation of Wetland Park Based on AHP Method—Taking Bilianhu Wetland Park in Zhaoqing, Guangdong Province as an Example. Landsc. Urban Hortic. 2024, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Fan, R. Landscape Visual Evaluation of Zijin Mountain National Forest Park. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2017, 32, 277–283. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tan, Z.M.; Chen, S.Q.; Cui, L.C. The Experience Evaluation of Urban Landscape of Historical & Cultural Blocks Based on Eye-Tracking: A Case Study of Yongqingfang, Guangzhou. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 54–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.F.; Man, X.B.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, Y.F.; Li, H.Y.; Yin, C.H.; Lin, Z.M.; Fan, J.X. Visual Quality Evaluation of Historic and Cultural City Landscapes: A Case Study of the Tai’erzhuang Ancient City. Buildings 2025, 15, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.Y.; Abu Bakar, S.; Maulan, S.; Yusof, M.J.M.; Mundher, R.; Zakariya, K. Identifying Visual Quality of Rural Road Landscape Character by Using Public Preference and Heatmap Analysis in Sabak Bernam, Malaysia. Land 2023, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.T.; Wang, K.P.; Li, S.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, H.; Ding, H.R.; Chen, Y.F.; Liu, C.H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.L. Analysis and Optimization of Landscape Preference Characteristics of Rural Public Space Based on Eye-Tracking Technology: The Case of Huangshandian Village, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.G.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.Q. Evaluation of Cognition of Rural Public Space Based on Eye Tracking Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Deng, W. A Review and Prospect of Rural Landscape Research: A Domestic and International Perspective. J. Mt. Res. 2025, 43, 286–302. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.L. Recognition and assessment method of rural landscape characters for multi-type and multi-scale collaborative transmission: Taking the Horgin Right Front Banner, Inner Mongolia of northern China as an example. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2022, 44, 111–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Bian, Z.X.; Wang, S.M. Analysis of rural landscape patterns around large and medium cities—Taking Shenyang City as an example. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Regul. 2020, 41, 223–230. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wei, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, H.C. Clustering Research on Eco-Rural Landscape Design Demand Based on KANO Model Analysis: Taking Rural Settlements in Yangtze River Delta Region as an Example. Mod. Urban Res. 2024, 8, 120–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Qiao, J.J.; Wang, W.W.; Zhu, X.Y.; Dun, Y.J. Study on Village Classification and Development Strategies under the Background of Rural Revitalization—A Case Study of 3 Towns in Fengqiu County, Henan Province. Areal Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 154–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.R.; Fu, W.C.; Zhu, Z.P.; Dong, J.W. Analysis of Advantages and Disadvantages of Panorama Presentation Technology in Landscape Visual Evaluation. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 53, 584–593. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.S.; Shen, S.Y.; Zhan, W. Research on Experience Evaluation of Cultural Landscape of Zhang Guying Village Based on SD and Eye Movement Analysis. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 98–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Deng, H.F. Evaluation of Forest Landscape Quality in Spring Based on Semantic Segmentation of Landscape Elements in PSPNet Deep Learning Network. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2024, 39, 231–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Chen, Y.Q. Dynamic Perception of Landscape Along Beijing-Qinhuangdao Railway in the Central Urban Area of Beijing. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 105–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Lavdas, A.A. Potential of Eye-Tracking Simulation Software for Analyzing Landscape Preferences. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; Dong, J.Y.; Weng, Y.X.; Dong, J.W.; Wang, M.H. Audio-visual interaction evaluation of forest park environment based on eye movement tracking technology. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 69–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.H.; Wu, M.Y.; Ma, Y.M.; Qu, H.Y. A Review of Eye Tracking Researches in Landscape Architecture Field. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2021, 36, 125–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.Z.; Wu, Y.F.; Qu, Q.X.; Guo, F.; Jiang, H.; Fan, X.X. The Research on Using Performance for Smart Touch Devices Based on Physiology and Eye Tracker Metrics. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2020, 25, 166–172. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; de la Fuente Suárez, L.A.; Gonzáles-Santos, L.; Barrios, F.A. Observation of environments with different restorative potential results in differences in eye patron movements and pupillary size. IBRO Rep. 2019, 7, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamedani, Z.; Solgi, E.; Hine, T.; Skates, H. Revealing the relationships between luminous environment characteristics and physiological, ocular and performance measures: An experimental study. Build. Environ. 2020, 172, 106702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.H.; Zhao, J.W. Evaluation on Aesthetic Preference of Rural Landscapes and Crucial Factors. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 47, 231–235. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Yan, L.J.; Yang, W.K.; Fang, T. Assessment of Landscape Visual Quality for Rural Residential Environment: Zhejiang Province as a Case. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2015, 27, 813–821. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.Y.; Yang, F.R.; Li, Z.; Shi, P.F.; Zhang, S.W. The Satisfaction Evaluation and Obstacle Factor Analysis of Villagers in Rural Landscape of Guangxi: A Case Study of Northern Villages in Beiliu City. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 87–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, W.F.; Yang, J.J. Scenic Beauty Evaluation and Influencing Factors Analysis of Urban Forest Parks. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 106–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.N.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.H.; Li, F.Z.; Li, X. Study on the Visual Evaluation Preference of Rural Landscape Based on VR Panorama. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2016, 38, 104–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.J.; Wu, C.C. The Scenic Beauty Features and the Ascension Paths of Beautiful Rural Landscape in the North of Anhui Province. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2017, 44, 1032–1037. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.C. Research on the Rural Landscape from the Perspective of Differentiation of Resident and Tourist Perceptions: Taking the Villages of Changdang Lake Tourist Resort as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.M.; Feng, M.L. Factor Analysis of Rural Landscape Evaluation Based on the Tourists’ Perception: A Case Study of Shushan Village in Suzhou. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2022, 37, 253–258. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, H.J. Influence of Familiarity to Urban Parks Environment on Landscape Preference: A Case Study of Mengqing Park, Shanghai. J. China Urban For. 2018, 16, 30–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.H.; Lin, Y.J. The Effect of Landscape Colour, Complexity and Preference on Viewing Behaviour. Landsc. Res. 2019, 45, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zheng, Y.F.; Cai, J.H.; Huang, H.J.; Li, H.L.; Ma, Y. Research of Evaluation Models and Thresholds for Park Landscaping Techniques Based on Eye Movement Analysis: A Case Study Based on Borrowing Scenery and Framing Scenery Methods. South Archit. 2025, 6, 88–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.T.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, L. Perceptions and Design of Women-friendly Public Spaces in Community: An Eye-tracking Experiment from a Gender Perspective. Int. Urban Plan. 2025, 40, 41–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Xia, L.; Wu, Y. Investigating the Visual Behavior Characteristics of Architectural Heritage Using Eye-Tracking. Buildings 2022, 12, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.F.; Han, L.W.; Mi, W.Y. From Traditional Villages to Rural Heritage: Implication, Characteristics and Value. Urban Dev. Stud. 2023, 30, 47–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.R.; Li, B.H.; Chen, X.X.; Dou, Y.D. Research on the Paths of Differentiated Protection and Revitalization of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of “Three-Wheel Drive”: A Case Study of Four Typical Traditional Villages in Hunan Province. Hunan Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2022, 45, 53–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Visual landscape quality evaluation of suburban forest parks in Taiyuan based on the AHP method. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2023, 43, 188–200. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.W.; Huang, Z.S.; Zhang, Y.B.; Liu, Y.F.; Pang, M. Landscape Scenic Beauty of Traditional Dong Minority Villages in Southeast of Guizhou Province. Chin. J. Ecol. 2019, 38, 3820–3830. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.T.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.K.; Meng, H.; Zhang, T. Visual Behaviour and Cognitive Preferences of Users for Constituent Elements in Forest Landscape Spaces. Forests 2022, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.G.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, M.Q. Multidimensional exploration of landscape preferences in rural squares: An empirical inquiry relying on electroencephalography, eye-tracking and Perceived Restorative Scale. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Yu, Q.L.; Yang, C.X. A Kansei-inspired product design approach for the Liao Dynasty Pagoda: Bridging cultural heritage and physiological signals. J. Eng. Des. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Liu, Y.R.; Huang, W.C.; Han, J. Analysis methods for landscapes and features of traditional villages based on digital technology—Taking Xiaocuo Village in Quanzhou as an example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 13–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.G.; Chen, H. The visual landscape evaluation of Taiping street historical and cultural district based on emotional cognition and eye-tracking. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2025, 45, 218–228. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.L. A study of the tactics for landscape transformation of traditional villages in the backdrop of beautiful countryside construction. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 43, 9–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.Q. The “Yan Town Ancient Street” rural landscape construction—The planning and design of suburban rural landscape of Fangezhuang Village of Yanqi Town in Beijing. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 32, 28–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 10 | 33.3% |

| Female | 20 | 66.6% | |

| Major | Landscape architecture | 10 | 33.3% |

| Non-landscape architecture | 20 | 66.6% | |

| Education level | Associate degree | 13 | 43.3% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 | 23.3% | |

| Graduate degree or above | 10 | 33.3% | |

| Frequent exposure to rural landscapes | Yes | 22 | 73.3% |

| No | 8 | 26.6% | |

| Eye Movement Indicator | Definition and Significance |

|---|---|

| Total fixation count | Refers to the total number of times participants’ gaze stays within the stimulus area during the experiment. The higher the fixation count, the richer the landscape information and the stronger the attraction, eliciting more sustained attention and exploration from participants [40]. |

| Total fixation duration | Refers to the total duration of participants’ gaze staying within the stimulus area during the experiment. Longer fixation duration indicates richer landscape information and stronger attraction, eliciting more sustained attention and exploration from participants [41]. |

| Total saccade duration | Refers to the total time spent on rapid eye movements between two fixation points during the experiment. Longer saccade duration indicates that participants engage in broader spatial scanning when exploring the landscape, reflecting higher cognitive involvement and interest level, thus demonstrating higher attractiveness [42]. |

| Pupil diameter enlargement count | Refers to the total number of times the pupil diameter changes during the experiment, directly reflecting the degree of interest in viewing. The more frequent the pupil diameter enlargement, the more it indicates heightened psychological attention and stronger emotional response [43]. |

| Total blink count | Refers to the total number of blinks during the experiment. Generally, the more relaxed observers are when viewing, the more likely they are to blink [44]. |

| Rural Type | Total Fixation Count | Total Fixation Duration (s) | Total Saccade Duration (s) | Pupil Diameter Enlargement Count | Total Blink Count | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Clustered improvement | 15.13 | 2.02 | 5.41 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.14 | 9.17 | 7.83 | 1.60 | 0.23 |

| Characteristic preservation | 15.91 | 1.44 | 5.81 | 0.69 | 1.02 | 0.09 | 10.11 | 7.69 | 1.63 | 0.31 |

| Urban–suburban integration | 14.57 | 1.42 | 5.33 | 0.45 | 0.92 | 0.10 | 11.50 | 6.67 | 1.48 | 0.24 |

| Source | Dependent Variable | Within-Groups Sum of Squares | Mean Square | p | F | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural type | Total fixation count | 138.936 | 2.724 | 0.061 | 2.963 | 0.104 |

| Total fixation duration | 15.885 | 0.311 | 0.029 | 3.782 | 0.129 | |

| Total saccade duration | 0.639 | 0.013 | 0.051 | 3.147 | 0.110 | |

| Pupil diameter enlargement count | 2804.778 | 54.996 | 0.64 | 0.451 | 0.062 | |

| Total blink count | 3.467 | 0.068 | 0.194 | 1.696 | 0.017 |

| Source | Dependent Variable | Within-Groups Sum of Squares | Mean Square | p | F | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural type | Scenic beauty | 10.872 | 0.213 | 0.006 | 5.752 | 0.184 |

| Source | Dependent Variable | Within-Groups Sum of Squares | Mean Square | p | F | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural type | X1 | 30.266 | 0.593 | 0.002 | 7.092 | 0.218 |

| X2 | 38.925 | 0.763 | 0.03 | 3.752 | 0.128 | |

| X3 | 34.004 | 0.667 | 0.003 | 6.627 | 0.206 | |

| X4 | 91.085 | 1.786 | 0.246 | 1.441 | 0.053 | |

| X5 | 46.585 | 0.913 | 0.15 | 1.972 | 0.072 | |

| X6 | 50.225 | 0.985 | 0.079 | 2.665 | 0.095 | |

| X7 | 51.404 | 1.008 | 0.09 | 2.521 | 0.090 | |

| X8 | 18.555 | 0.364 | 0.2 | 1.66 | 0.061 | |

| X9 | 37.682 | 0.739 | 0.728 | 0.319 | 0.012 | |

| X10 | 16.317 | 0.32 | 0.015 | 4.56 | 0.152 | |

| X11 | 14.98 | 0.294 | 0.001 | 8.558 | 0.251 | |

| X12 | 13.569 | 0.266 | 0.001 | 7.588 | 0.229 | |

| X13 | 5.299 | 0.104 | 0.016 | 4.462 | 0.149 |

| Total Fixation Count | Total Fixation Duration | Total Saccade Duration | Pupil Diameter Enlargement Count | Total Blink Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenic beauty | 0.510 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.543 ** | −0.151 | 0.481 ** |

| Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Scenic beauty (R2 = 0.295; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| Total saccade duration | 0.543 | 4.660 | <0.001 | 1 | 1 |

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | X11 | X12 | X13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenic beauty | 0.443 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.151 | 0.310 * | 0.216 | 0.235 | 0.528 ** | −0.125 | 0.719 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.769 ** | 0.731 ** |

| Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Tolerance | Beta | |||

| Scenic beauty (R2 = 0.698; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X11 | 0.542 | 5.061 | <0.001 | 0.527 | 1.898 |

| X13 | 0.314 | 2.81 | 0.007 | 0.484 | 2.064 |

| X5 | 0.167 | 2.03 | 0.048 | 0.889 | 1.125 |

| Indicator | Total Fixation Count | Total Fixation Duration | Total Saccade Duration | Pupil Diameter Enlargement Count | Total Blink Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.253 | 0.06 | 0.24 | −0.360 ** | 0.144 |

| X2 | 0.181 | −0.033 | 0.194 | −0.411 ** | 0.152 |

| X3 | 0.263 | 0.084 | 0.244 | −0.395 ** | 0.144 |

| X4 | 0.227 | 0.073 | 0.172 | −0.396 ** | 0.109 |

| X5 | 0.304 * | 0.536 ** | 0.284 * | 0.253 | 0.23 |

| X6 | 0.316 * | 0.568 ** | 0.311 * | 0.355 ** | 0.258 |

| X7 | 0.307 * | 0.557 ** | 0.309 * | 0.348 * | 0.262 |

| X8 | 0.328 * | 0.404 ** | 0.296 * | 0.113 | 0.231 |

| X9 | 0.005 | −0.098 | −0.009 | −0.155 | 0.115 |

| X10 | 0.419 ** | 0.259 | 0.452 ** | −0.300 * | 0.342 * |

| X11 | 0.431 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.447 ** | −0.258 | 0.314 * |

| X12 | 0.517 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.521 ** | −0.308 * | 0.418 ** |

| X13 | 0.276 * | 0.304 * | 0.297 * | −0.239 | 0.364 ** |

| Standardized Coefficient | t | Significance | Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Total fixation count (R2 = 0.368; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X12 | 0.518 | 4.65 | <0.001 | 1 | 1 |

| X6 | 0.317 | 2.849 | 0.006 | 1 | 1 |

| Total fixation duration (R2 = 0.48; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X6 | 0.568 | 5.628 | <0.001 | 1 | 1 |

| X12 | 0.397 | 3.927 | <0.001 | 1 | 1 |

| Total saccade duration (R2 = 0.428; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X12 | 0.602 | 5.34 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 1.111 |

| X6 | 1.286 | 2.905 | 0.005 | 0.058 | 17.118 |

| X5 | −1.007 | −2.268 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 17.225 |

| Pupil diameter enlargement count (R2 = 0.233; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X2 | −0.301 | −2.253 | 0.029 | 0.842 | 1.187 |

| X4 | −0.277 | −2.072 | 0.043 | 0.842 | 1.187 |

| Total fixation count (R2 = 0.095; Sig. < 0.01) | |||||

| X12 | −0.308 | −2.339 | 0.023 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Q. Visual Quality Assessment of Rural Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Analysis and Subjective Perception. Sustainability 2026, 18, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010161

Li Y, Luo H, Sun S, Wang K, Zhao Q. Visual Quality Assessment of Rural Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Analysis and Subjective Perception. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010161

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yu, Hao Luo, Siqi Sun, Kun Wang, and Qing Zhao. 2026. "Visual Quality Assessment of Rural Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Analysis and Subjective Perception" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010161

APA StyleLi, Y., Luo, H., Sun, S., Wang, K., & Zhao, Q. (2026). Visual Quality Assessment of Rural Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Analysis and Subjective Perception. Sustainability, 18(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010161