Abstract

The setting and scope of cooperation between geoparks and their partners significantly affect their professional development, overall sustainability of operation, the attractiveness of the area for visitors and economic stability. The article deals with the concept of cooperative management in the case study of the Banská Bystrica Geopark in the Slovak Republic, which presents a practical and realistic framework for the development of long-term partnerships, their mutual harmonisation and planning of common activities in accordance with the needs of a specific area. The application of these principles is described in the form of a case study, which represents a model educational product called “The Copper Yarn of the Spania Valley”. The resulting model confirms the importance sustainable approach, the importance of cooperation in the development of the product, which was created as a result of targeted cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and several regional partners, including the local government, professional institutions and stake-holders. The article points out the need to embed solid and clearly defined cooperation approaches into strategic documents at the national and regional levels, points out the need for state support and a clearly defined position of geoparks in the tourism system. The results could significantly contribute to their stability, sustainability and the effective functioning of partnerships in the territory of geoparks.

1. Introduction

1.1. Geopark

Geoparks are areas with significant geological heritage that play an important role not only in protecting inanimate nature, but also in developing education and raising awareness about mineral wealth and supporting sustainable development of regions. This is a modern approach to the use of natural resources, emphasizing the connection of geoscientific knowledge with specific tools for nature protection, environmental education, and tourism development. Geopark offer visitors an experiential way of learning about geological phenomena, thereby contributing to raising awareness of the importance of geological sciences in contemporary society [1]. Geoheritage refers to geological features of scientific, cultural, aesthetic or educational significance, while geoparks are designated areas that protect and promote these sites through sustainable development and tourism [2,3,4].

In such an area, geological heritage is linked to the natural, cultural, and intangible values of the region, thereby contributing to a better understanding of important social issues, such as the ecologically responsible use of nature, managing the consequences of climate change, or preventing natural hazards [5]. At the same time, geoparks support local communities and encourage the emergence of innovative local businesses, new jobs, and quality educational programs through geotourism [5,6,7,8]. The main objectives of geoparks are to protect geoheritage, increase public awareness and understanding of geoscience, and promote sustainable economic growth in local communities. Education acts as a cornerstone in achieving these three objectives, as it provides the necessary foundation for their implementation [9]. Geoparks serve as centres of sustainable development, integrating geological, ecological and cultural heritage into coherent frameworks that support local economies and protect natural resources. Geotourism, a distinctive feature of geoparks, emphasises responsible tourism practices that balance environmental protection with cultural appreciation [10]. In this context, micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises play an important role by offering products and services that showcase local heritage, thereby connecting visitors with the unique attributes of the region [11,12].

1.2. Geopark Management

Effective management of a geopark requires a precisely defined organizational structure with a legal basis in national legislation, which can ensure the implementation of measures for the protection, enhancement, and sustainable development of the territory [13,14,15]. Geopark management also covers various areas of activity, from scientific research and management of geological heritage to environmental education and the development of geotourism [16,17,18]. In today’s dynamic and interconnected world, sustainable development necessitates effective coordination among multiple stakeholders [19].

1.3. Cooperative Management

Cooperative management is a tool that allows these processes to be managed systematically. Its essence is the building of long-term partnerships, based on a common vision, shared goals, and mutual responsibility. This type of management goes beyond the framework of ordinary coordination and functions as a strategic means of supporting and developing relationships in general [20,21].

Many authors understand this concept in several ways. “Staatz (1983) [22] views cooperative management as joint decision-making within heterogeneous preferences. He emphasizes the need for a model of cooperation based on clearly defined group decision-making” [22]. “According to Veerakumaran (2006) [23], cooperative management is a complex decision-making process, with decisions being made at all levels of management. Building cooperative management in an enterprise represents a real challenge that managers have to deal with, and this process is influenced by several factors” [23]. According Fei decision-making should fully consider the demands of stakeholder groups so as to reach the optimal strategy of multi-level goals and strong associations. [24].

Cooperative management is based on a set of principles that reflect best processes in the practice of collaboration between diverse entities. These principles help to effectively manage joint initiatives in environments where it is necessary to coordinate multiple interests, respond to changing conditions, and ensure the long-term sustainability of joint decisions [25,26,27,28,29].

1.3.1. General Principles of Cooperative Management

Shared vision and shared goals. Cooperation is most effective when all involved partners have a clear and shared understanding of the goals. A shared vision guides the activities of the individual parties, helps to avoid misunderstandings, and increases the coherence between the individual steps.

Dialogue and cooperation between multiple actors and levels. An important part of cooperative management is the connection of different levels of government, from local government to national institutions, and their active exchange of information. Equally important is the involvement of actors from different sectors who contribute with their experience and knowledge.

Shared responsibility for decision-making and action. Managing cooperation requires that all parties involved share in the decisions and their results. Shared responsibility creates a balance between rights and obligations, thus promoting trust and equal participation of all participants.

Autonomy of individual participants. Although the collaboration is based on coordination, each partner maintains its own autonomy, ensuring respect for the individual needs, priorities, and ways of functioning of individual organizations.

Accepting different forms of knowledge. Effective cooperation requires accepting different forms of knowledge. In addition to professional and technical knowledge, local experiences and traditional knowledge also play an important role, enriching the decision-making process.

Focus on learning and adaptation. The ability to adapt to changing circumstances is essential for the long-term functioning of cooperation. Learning from one’s own experiences, the willingness to reflect and continuously adjust approaches are key to managing uncertainty and developing partnerships [26].

1.3.2. Aspects of Cooperation Management

Effective management of cooperation between companies requires an understanding of the basic areas that affect the entire cooperation process. These areas can be divided into four main stages that systematically cover the individual phases of cooperation from its inception to the evaluation of results [29]. Strategic management forms the basis for creating a cooperation strategy. It is preceded by a thorough analysis of the internal and external environment of the company and its goals. The task of this aspect is to design a cooperation strategy that will be in line with the direction of the company and at the same time take into account the goals and needs of partners. At the same time, it allows for the creation of a stable framework for long-term and sustainable cooperation [30,31]. Change management. When implementing cooperation, changes often occur in the internal setting of the organizational unit. This aspect focuses on managing organizational changes that are necessary when expanding or deepening cooperation initiatives. This includes, for example, adjusting structures, corporate culture, or management style. An important part is the ability to adapt to new forms of cooperation [30]. Project management Cooperation projects are time-bound activities that require coordinated planning and execution. Project management helps ensure that projects are properly planned, effectively implemented, and completed on budget and on schedule. It also helps minimize risks and supports the achievement of the established cooperation goals [30]. Process management. The basis of well-functioning cooperation is a clearly defined set of processes. Process management deals with their identification, simplification, and optimization. The goal is to ensure that cooperation activities run smoothly, are efficient, and provide real benefits to the parties involved. Every step of the cooperation should be measurable and under control [30]. Human resource management. People are a decisive factor in the success of cooperation. This aspect focuses on the involvement of employees in cooperation activities, their motivation, and the development of skills. Education, support for teamwork, and the creation of a suitable working environment contribute to ensuring that employees can effectively participate in common goals and contribute to sustainable cooperation [30]. Table 1 summarizes and clarifies the key areas of management that are part of the cooperation.

Table 1.

Basic areas of management influencing the cooperation process.

1.4. The Importance of Cooperative Management in Regional Development, Tourism, and Environmental Management

Cooperative management plays a crucial role in addressing interconnected challenges in areas such as regional development, tourism, and environmental protection. These territories are characterised by a high degree of complexity and constant change, which require active coordination between diverse actors. The connection of public institutions, local governments, business entities, and communities creates the basis for the effective management of both social and ecological systems [30,32,33,34]. From the perspective of regional management, cooperative management represents a way to link decision-making at different levels from local to national and create joint solutions that take into account the needs of all stakeholders. This approach also allows for flexible responses to changing conditions and supports long-term sustainability of development [26,35,36]. In the field of tourism, cooperative management has proven effective in reducing pressure on ecosystems that are attractive for tourism, but also sensitive. An example from Northern Wisconsin demonstrates that collaboration between public authorities, local residents, and other stakeholders can create a balance between the economic benefits of tourism and the protection of natural values. Planning based on assumed development scenarios as part of cooperative management helped to ensure that decisions were based on different perspectives and interests and were sustainable in the long term [26,37,38].

When pointing out the positive aspects of the application of cooperative management in a geopark, it is also very appropriate to point out the possible negative aspects, which are often unavoidable. In this relationship, the following situations may arise that have an adverse effect on the overall intention of sustainable goals, which are the essence of the existence of geoparks. When creating partnerships and mutual cooperation, a situation may arise where a partner will show an effort for leadership, which is not possible in an equal relationship of partners from the perspective of cooperative management. Another negative aspect may be the general lack of interest of potential partners in participating in the functioning of the geopark. There may be a misunderstanding of common goals and visions on the part of the partner. Another factor is the possible misuse of know-how between partners, and it is also necessary to mention the risk of hidden competition. An overview of negatives and positives is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Positive and negative aspects of the application of cooperative management.

1.5. Geoparks in Slovakia

Geoparks in Slovakia represent a significant initiative aimed at protecting and presenting the country’s geological heritage, supporting environmental education and sustainable development of regions. This concept was officially adopted in 2000, when the government of the Slovak Republic approved the “Concept of Geoparks in the Slovak Republic”, thus Slovakia joined the global trend of creating geoparks under the auspices of UNESCO [39]. Currently, four geoparks have been established in Slovakia as part of the national network: the Malé Karpaty Geopark, the Novohrad-Nógrád Geopark, the Banská Bystrica Geopark, and the Banská Štiavnica Geopark. These geoparks serve as platforms for integrating natural heritage protection with local development, supporting geotourism and providing space for environmental education and research. Their activities are coordinated by the Interdepartmental Commission of the Geopark Network of the Slovak Republic, which was established in 2015 as an advisory body to the Minister of the Environment of the Slovak Republic [40].

The article deals with a case study on the territory of one of the national geoparks, namely the Banská Bystrica Geopark. The Banská Bystrica Geopark was established as a regional initiative aimed at protecting and presenting the rich mining, technical and natural heritage of central Slovakia. Compared to other Slovak geoparks, such as the Malé Karpaty Geopark or Novohrad–Nógrád, its partnership network is not as significantly developed or systematically presented in publicly available sources. Nevertheless, the geopark relies on cooperation with selected public institutions, regional self-government and community organizations, which play an important role in supporting geotourism, developing infrastructure and promoting the region. The article will describe its current management and product status in the introductory part. In the final part of the article, the Banská Bystrica geopark will be used again to apply the model, pointing out its advantages compared to the current state.

The main objective of the article is a new approach in geopark management towards formal and managed partnerships. The conceptual framework that guides this study is based on the principles of cooperative management and its implementation in the functioning of geoparks and their sustainability. The main focus of the study is the identification of partners, the creation of a model of cooperation based on the principles of cooperative management and pointing out the benefits for each partner who enters into a partnership with a geopark. The theoretical model is applied to the Geopark Banská Bystrica through a case study and the creation of a geotourism product.

The methodology created in this way is intended to eliminate the gaps in the management of geoparks:

- The relationship between management and partners is not clearly defined.

- The benefits resulting from the cooperation between geoparks and partners are not clearly explained.

- Partners do not have a relationship with geopark products.

- The importance of partners is not enshrined in strategic documents.

2. Materials and Methods

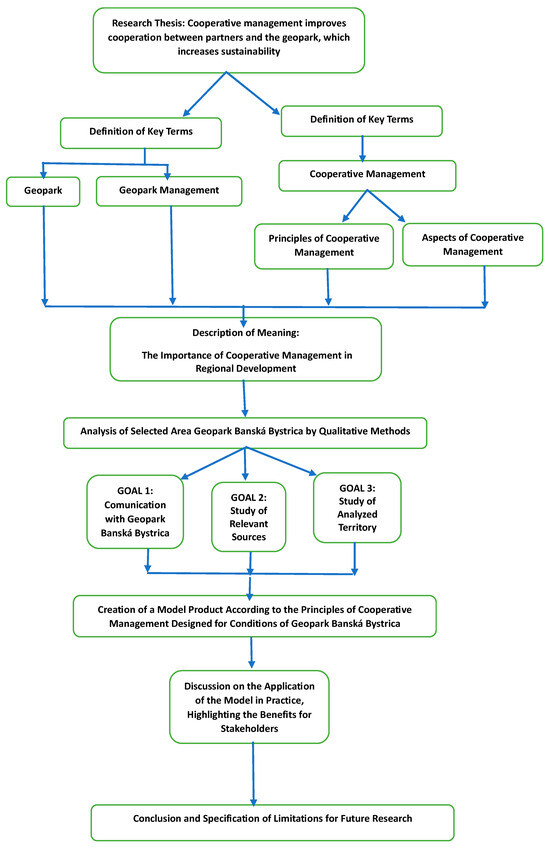

Geoparks in Slovakia collaborate with various components and at multiple levels. This cooperation is based on the delivery of a certain service, which the geopark subsequently offers to its visitors in the form of a created geotourism offer. We cannot speak directly about cooperative management in the true sense of the word. It is a certain form of partnership, which, however, is not equal and the geopark is superior to its management. Before the actual work, an overview of the issue will be made through literature and case studies with similar issues. First of all, it is necessary to signal the current state of geoparks and their partnerships. The result of the analysis will be a scheme where partners and their roles will be identified, as well as their relationship to the geopark management. Then a critical analysis will be carried out where the strengths and weaknesses of such cooperation will be identified. Based on the results of the analysis of the current state, a model of cooperation between the geopark and its partners based on cooperative management will be designed, where the weaknesses of the current state will be eliminated. The result should be cooperation where individual components gain not only benefits, but also a sense of full-fledged partnership and not just the position of a subcontractor. Subsequently, an analysis of the cooperative management model was made, where the strengths and weaknesses of such cooperation will be described. We assume that compared to the current state, the cooperative model will contain a minimum number of weaknesses. The next step will be to apply the model to an existing geopark and create a product that would point out the advantages of cooperative management directly in practice. All partners who have something to offer in a given product and of course the management of the geopark would be involved. The application of the model will be in the territory of the Bystrica geopark, which has partners as well as existing geotourism product. Figure 1 display the scheme of the research design.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the research design.

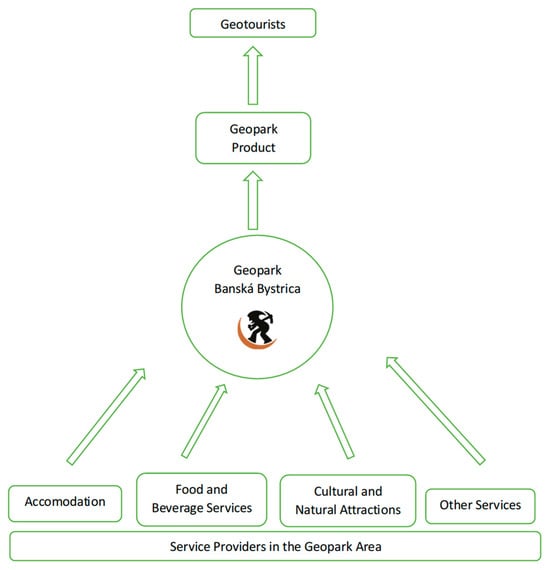

The methodology of this article is based on the knowledge of the current state of geopark management. Geoparks in Slovakia collaborate with various components and at multiple levels. This cooperation is based on the delivery of a certain service, which the geopark subsequently offers to its visitors in the form of a created geotourism offer. We cannot speak directly about cooperative management in the true sense of the word. It is a certain form of partnership, which, however, is not equal and the geopark is superior to its management. The current state of such management, which cooperates with its partners, is shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that it is a cooperation, but the involvement of partners in the final product of the geopark is minimal, or even partial. The model presents the cooperation and relationships between partners and the geopark in creating a product. At the lowest level are the service providers in the Geopark area, who are divided into the following categories:

Figure 2.

The current model of cooperation and product creation: geopark versus entity in the territory.

- Accomodation.

- Food and Beverage Services.

- Cultural and Natural Attractions.

- Other Services.

All these categories of services provide their service to the geopark, which is shown by arrows pointing to the central entity—Geopark Banská Bystrica. Subsequently, the geopark creates the resulting product and provides it to the market and to visitors to the geopark. The relationship between Geopark Banská Bystrica and the partners is a partnership, but it is clear that the partners are not on the same level. Only the geopark has access to the product. The partners do not have the opportunity to enter the product, nor do they have the opportunity to enter its creation. Although the product is the result of combining regional services, geological heritage, and educational elements, which are managed under the banner of the geopark, for the partners, it is a foreign product, and therefore, they do not have responsibility for its sustainability.

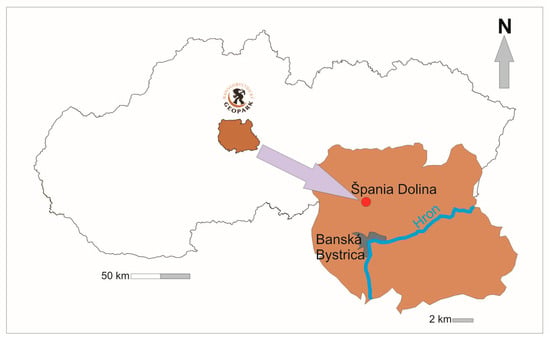

3. Analysis of the Selected Area

The Banská Bystrica Geopark is an area with a highly developed geological and mining heritage, situated in the central part of Slovakia. Figure 3 shows the territory of the geopark within the Slovak Republic. The region is characterized by a diverse geological structure and a rich history of mining of minerals, especially copper, gold and silver, in areas such as Špania Dolina, Staré Hory and Ľubietová. The city of Banská Bystrica, together with Kremnica, was one of the important economic centers, where the famous merchant families of Thurz and Fugger operated, which played a key role in the export of precious metals [41]. The Banská Bystrica Geopark is a place where remarkable technical monuments associated with the mining tradition of the region meet, including a number of preserved objects, such as shafts, smelters, sluice gates, entrances to galleries and a historical water management system with a total length of approximately 40 km. In addition to the industrial heritage, the geopark is also interesting for its cultural and ethnographic value, represented by traditional forms of rural and urban architecture in localities such as Banská Bystrica and Kremnica. An important element of local identity is also the Špaňodolin lace, known for its long-standing craft tradition. In this way, the geopark connects natural wealth with historical and cultural heritage, creating space for environmental education, sustainable tourism and regional development [42].

Figure 3.

Geopark territory and Spania Dolina as a product’s place.

4. Results

The analysis of the selected area represents a comprehensive view, which is carried out with the aim of effectively developing geotourism in the municipality of Špania Dolina through the creation of an experiential and educational product. The choice of Banská Bystrica Geopark as a model area is based on its exceptional historical and natural potential, particularly in relation to its mining heritage and preserved landscape structure. At the same time, it is a geopark whose cooperation has not yet been systematized into a complex product, creating space for the design of an effective solution with a direct practical impact. The proposal is based on the principle of mutual synergy and cooperation, not competition, which is the key philosophy of cooperative management. Each partner enters the process with their own competencies, experience, and infrastructure, thereby jointly creating value for the entire region.

The proposal includes four main cooperations with the municipality of Špania Dolina, the Pension Klopačka, the Center for Folk Art Production (CFAP), and the Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood. Each of these entities brings unique strengths, from accommodation and gastronomic services to the professional interpretation of mining heritage, as well as craft traditions and self-governing support for the development of the territory. Their mutual connection creates space for the creation of a comprehensive educational package called “Copper Thread of the Špania Dolina”, which offers visitors an authentic experience associated with learning about the cultural and natural values of the site. The entire proposal for cooperation and product solution is also based on the principles of cooperative management, which emphasizes balanced partnership, clearly divided tasks, joint planning, effective communication and long-term continuity of cooperation as tools to increase the quality and sustainability of development initiatives in the area.

The cooperation model of the Banská Bystrica Geopark is built on the principle of connecting diverse actors in the area to create stable and functional partnerships, and represents key regional partners with whom the geopark develops strategic cooperation in the field of geotourism, cultural heritage, crafts and community development. Each of the partners contributes to the common vision with their own resources, knowledge, and specific background, thus creating a synergistic basis for the creation of the proposed educational product “Copper Thread of the Špania Dolina”.

4.1. Actors of Cooperation with the Banská Bystrica Geopark

4.1.1. The Village of Špania Dolina

The village of Špania Dolina is located approximately 14 km north of the center of Banská Bystrica, in the picturesque mountainous environment of the Starohorské vrchy. Thanks to rich deposits of copper ore, often with an admixture of silver, Špania Dolina was famous in the past as an important mining center throughout Europe. Although systematic mining is documented from the 11th to 12th centuries, archaeological research has shown that ore was processed in this area as early as the Eneolithic period. The village has preserved a number of unique mining heritage, folk architecture and customs that reflect the character of traditional life in mountain mining settlements [43].

The proposed cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and the municipality of Špania Dolina is built on the principle of public-community partnership, connecting the interests of the local government and the strategy of the geopark in the field of protection and presentation of natural and cultural heritage.

Its goal is:

- Involvement of the municipality in the development of geotourism—through joint event planning, program routing and support of accompanying activities in the municipality.

- Strengthening local identity—through the presentation of mining and craft traditions, use of public spaces and cooperation with the community.

- Sharing information—on visitor numbers, infrastructure and needs of the area as a basis for planning geopark activities.

- Technical and organizational support—including making municipal property accessible and cooperation in event logistics.

- Regular communication and coordination—using a common platform for planning, solving challenges and developing cooperation.

4.1.2. Pension Klopačka

Pension Klopačka is located in the center of the historical mining village of Špania Dolina, which represents one of the most important places in the Banská Bystrica Geopark in terms of cultural and natural heritage. It is an architecturally valuable building that used to serve as a call tower for miners. Today, it has been completely renovated and provides accommodation, catering and social spaces. Its strategic location, historical authenticity and available capacities create ideal conditions for cooperation with the geopark [44]. The aim of the cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and Pension Klopačka is to create a long-term strategic partnership that will support the development of geotourism, informal education and regional development.

For this partner, the cooperation is oriented towards:

- Expanding the active scope of the geopark in one of its key locations with significant historical and geological potential.

- Ensuring quality facilities for organizing educational and experiential activities of the geopark, including accommodation, social spaces, catering, also the unique traditional mining dish called ”štiarc”.

- Connecting geological and cultural heritage through innovative forms of tourism with an emphasis on experience and knowledge.

- Supporting sustainable forms of tourism and increasing visitor numbers to the area in accordance with the principles of nature protection and cultural identity, at the same time, it is expected that the cooperation will contribute to a more effective use of the potential of the municipality of Špania Dolina as a model location for the development of geotourism within the Banská Bystrica Geopark.

4.1.3. The Centre of Folk Art Production (CFAP)

The Centre of Folk Art Production (CFAP) is a state institution that has been dedicated to the protection, support and development of traditional crafts and folk art production in Slovakia since 1945. Its activities focus on searching for bearers of traditional skills, documentation of craft techniques, professional advice, exhibitions, creation of educational programs and certification of products. CFAP actively cooperates with craftsmen across Slovakia and its goal is to preserve and transfer traditions into the current social context [45]. The aim of the cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and the Centre of Folk Art Production (CFAP) is to create a long-term and value-based partnership that connects the natural and cultural heritage of the region through activities focused on crafts, traditions and geotourism. The basis of this cooperation is a common interest in preserving the identity of the territory, supporting craftsmen and providing meaningful experiences for visitors.

The specific goals of the cooperation are as follows:

- Include traditional crafts in the geopark offer as part of the intangible cultural heritage of the area.

- Create new forms of educational and creative activities suitable for schools, families, tourists and professional groups.

- Make the craft tradition of the region visible as part of the geotourism experience, with an emphasis on its connection with the local environment, history and raw materials.

- Support the sale and presentation of craft products from local and certified producers.

- Preserve and develop unique techniques such as bobbin lace, with an emphasis on the regional identity of Španá Dolina and the involvement of the local community.

4.1.4. The Herrengrund-Špania Dolina Mining Brotherhood

The Herrengrund-Špania Dolina Mining Brotherhood is a civic association founded in 2003 with the aim of renewing and developing the more than one hundred-year-old mining traditions in the Špania Dolina region. The association is dedicated to collecting, restoring and preserving monuments related to mining activities and the history of copper mining in this area. As part of its activities, the Brotherhood operates the Copper Museum, which offers visitors an exhibition of minerals, the history of mining and ore processing, as well as interactive elements, such as the opportunity to mint a replica of a historical coin by hand [46]. The aim of the cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and the Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood is to jointly contribute to the preservation and presentation of the mining heritage of Špania Dolina and, at the same time, to enrich the geotourism offer with authentic experiences connected with history, community and traditions.

The cooperation is aimed at:

- Connecting geology and mining with the cultural heritage of the region through experiential programs,

- Involving the brotherhood in guiding and educational activities within the Mining Nature Trail, the Copper Museum and geopark events,

- Creating a strong local partnership that connects the community, history and geotourism potential of the area, developing educational programs for schools and interest groups, with an emphasis on historical-geological interpretation and direct contact with the bearers of tradition.

4.2. Contractual and Formal Arrangements for Cooperation in the Conditions of the Slovak Republic

To ensure systematic, transparent and long-term sustainable cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and individual partners, it is necessary to create a clear and legally enforceable framework of relations. This framework is built on a series of contractual documents that regulate the competences of the parties involved, the scope of cooperation, the method of communication, promotion and sharing of outputs. Contracts are also a tool for building trust, effective planning and preventing potential misunderstandings. Table 3 summarizes all applicable contracts within the framework of cooperative relationships in a geopark based on mutual benefits.

Table 3.

Basic contracts within the framework of cooperative relationships in a geopark based on mutual benefits.

All proposed forms of cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark and the involved partners are based on a common value base, which does not emphasize profit, but on long-term social benefit. The aim of the geopark is to raise awareness of the exceptional natural and cultural values of the region, their protection and support of meaningful regional development. Cooperation is about complementing and connecting the strengths of individual partners. The geopark perceives these relationships as a tool of mutual benefit, each partner contributes to the cooperation with its resources, knowledge or infrastructure and at the same time gains visibility, professional support and the opportunity to develop its activities in a new context. This principle of mutual synergy becomes the basis for the creation of the proposed educational package, which is the result of a common vision, interconnected capacities and shared values. In this process, the Geopark not only fulfills a coordinating and professional function, but also creates a space in which individual entities become partners in building an attractive, valuable and sustainable product for the public.

4.3. Proposal for an Educational Product “Copper Thread of Špania Dolina”

Based on the partnerships described above, the professional background of individual entities and clearly defined contractual frameworks, a comprehensive proposal for an interactive educational package called Copper Thread of Špania Dolina is being created. This package is the result of cooperation between the Banská Bystrica Geopark, the municipality of Špania Dolina, the Klopačka Guesthouse, the Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood, the Copper Museum and the CFAP, with each of the partners playing a specific role in its realization and implementation. The main ambition of the package is to connect the cultural and natural heritage of the region in the form of experiential education, and at the same time offer visitors a unique geotourism product that connects education, traditions, movement in the landscape and community value. The following section elaborates on the content, structure and mechanism of operation of this product, including its technical, content and organizational aspects.

The educational package Copper Thread of Španej Dolina is a comprehensive program designed for visitors who want to learn about the unique natural, technical and cultural heritage of this mining village in the form of experiential learning. Its goal is to create a modern and engaging geotourism product that combines knowledge with fun and emotion through games, questions and interaction. The package connects the most important stops in Španej Dolina, such as Klopačka, the Mining Astronomical Clock, the Copper Museum, the Maximilian Heap, the Daily Imperial Gallery, the Ludovík Shaft and the exhibition of Španej Dolina lace into one logically connected route. At each location, visitors first answer questions and only then discover the stories, connections and cultural context of the given place.

The main intention is to create a comprehensive, coherent and experiential-educational program that can appeal to diverse groups of visitors and raise awareness of the exceptional mining history and geological heritage of Španej Dolina.

The specific goals of the educational package are:

- Expand and make tof he educational packagee geotourism offer more attractive through an authentic combination of natural and cultural heritage, thereby increasing visitor interest in the site.

- Strengthen educational and outreach activities that will allow visitors to gain a deeper understanding of the historical, geological and cultural contexts in the region.

- Support the preservation of traditional crafts (such as Špaňodolinská lace), regional gastronomy (regional food called “štiarc”) and mining traditions through cooperation with local partners.

- Create a sustainable tourism model that contributes to the economic development of the region without negatively impacting its natural and cultural values.

- Increase regional identity and local pride through high-quality and professionally prepared educational activities that are accessible to all target groups.

From a sustainability perspective, the package serves not only as an educational tool, but also as a tool for regional development. It strengthens awareness of the location, increases the attractiveness of the region, supports local service providers and connects natural and cultural heritage into a comprehensible and experiential product suitable for the modern visitor.

Sharing the experience and community involvement of visitors. Within the modern approach to cultural and educational products, digital feedback and active sharing of experiences also play an important role, which naturally support the promotion of the region and build a community around the place and its stories. While completing individual stops, participants can document interesting moments in the form of photos, short videos, observations or stories. They can then publish these on social networks (e.g., Instagram, Facebook) using the official hashtag #MedenanitSpanejDoliny. This simple form of interaction: strengthens the personal connection of the visitor with the place, supports a viral form of marketing through personal recommendations and serves as feedback for the game organizers and partners. To encourage active participation, each share with the hashtag will be automatically entered into a monthly draw for small prizes such as thematic regional souvenirs, free entry to the Copper Museum or a discount on the traditional Štiarc meal at the Klopačka Guesthouse. In addition, each participant who publishes a post using the hashtag will receive a 15% discount coupon for their next visit or product within the geopark. The discount can be used when playing again, purchasing souvenirs or in partner establishments. A selection of the most creative posts will be regularly presented on the official channels of the Banská Bystrica Geopark as a form of appreciation and motivation for other visitors. This community element not only supports the spread of awareness, but also creates a personal connection between the visitor and the place and strengthens their return.

Tasks of individual partners. The successful implementation and long-term sustainability of the educational package Copper Thread of the Španej Dolina is the result of cooperation between several partners, who together create a functional, professionally covered and authentic geotourism product. Each of the subjects brings specific competencies, capacities and local ties to the project, which are key to the quality of the overall experience. The Banská Bystrica Geopark is the main coordinator, professional guarantor and initiator of the educational product. It ensures: methodological management and content creation of quizzes, explanatory texts and educational materials, design and development of digital and printed forms of the game (application, visitor diary), overall coordination of partners and schedule of activities, marketing communication and promotion of the package through its own communication channels (web, social networks, printed materials), ensuring visual identity and graphic outputs (maps, certificates, posters), evaluating feedback and suggestions for improving the product.

The municipality of Špania Dolina represents a public territorial partner that provides: access to and marking of public locations and spaces (e.g., Halda Maximilián, galleries, nature trail), cooperation in organizing events and accompanying activities in the municipality (e.g., Lace Days, Miners’ Day), support of logistics and permitting processes in the implementation of events, ensuring communication with local residents and stakeholders, participation in promoting the project and sharing outputs through municipal communication channels.

Pension Klopačka Klopačka, as a partner accommodation and gastronomic facility, plays an important role in both the experiential and operational parts of the package. Its tasks include: providing spaces for the beginning and end of the route (registration, evaluation, certificates), distributing printed materials and tools for participants, participating in the gastronomic part of the package (tasting traditional Štiarc food), making the exhibition of Špania Dolina lace available in the guesthouse, and handing over souvenirs and rewards to participants.

The Center for Folk Art Production CFAP provides professional support for the craft part of the project, especially in the field of bobbin lace. Its tasks are: professional consultation and guarantee in the presentation of Špania Dolina bobbin lace as an intangible cultural heritage, cooperation with local craftsmen and bobbin lace instructors, organization of accompanying creative workshops and craft demonstrations in the case of events, design and assistance in the certification of craft products as geoproducts, cooperation in the design of thematic souvenirs (e.g., miniatures of lace patterns).

The Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood Civic Association covers the professional interpretation of mining history and traditions in Špania Dolina. As part of the project, it provides: access and interpretation in the premises of the Copper Museum, the involvement of other mining sites—Šachta Ľudovíka, Denná cisárska štôlňa and the Mining Educational Trail, conducting commented tours and involving authentic elements (period objects, interactive demonstrations), expert consultations on mining topics, historical data and local terminology, the creation of thematic supplements and printed materials with a mining motif.

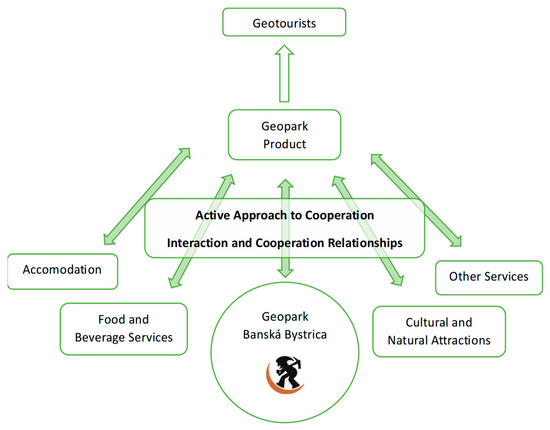

Figure 4 presents the model of functioning of the Banská Bystrica Geopark, which emphasizes the role of the Active Approach to Cooperation and Cooperation Relationships as key elements. The Banská Bystrica Geopark, as well as the regional partners (Service Providers), are on the same level. The main difference from the previous model lies in the creation of one layer: “Active Approach to Cooperation/Cooperation Relationships.” The interaction between the Geopark Banská Bystrica and each category of regional partners is mutual—they are guided by double-sided arrows that pass through the “Principles of Cooperation”. These arrows symbolize active, mutual and two-way interaction relationships. The Geopark not only accepts the offer of partners, but also actively cooperates with them, while the partners influence the Geopark. This is co-creation. The resulting product not only comes directly from the geopark but is the output of an Active Approach to Cooperation. It is the product of joint efforts and coordination between the Geopark and its partners, which is illustrated by arrows pointing from the interaction relationships to the product. The goal of this entire cooperative mechanism is to create an attractive and comprehensive product that will successfully address and satisfy the target group of geotourists. Advantages of this model: All partners are involved in the creation of the product, they see the benefits it brings to each partner, they feel full responsibility for its sustainability. The model shows that a sustainable and successful product is not just the sum of services, but the direct result of actively managed, interactive, and two-way cooperative relationships between the Geopark and its regional partners.

Figure 4.

Proposal for an effective cooperation model and product creation: geopark versus entity in the territory.

5. Discussion

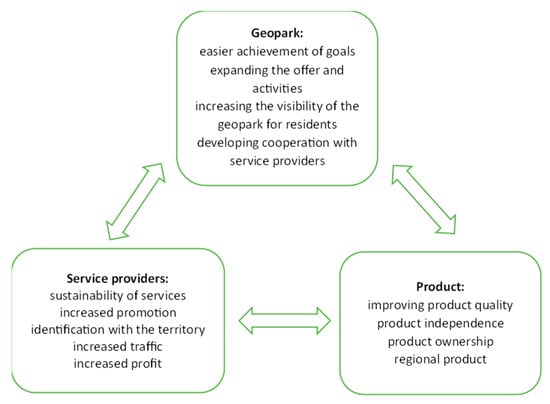

The benefits of cooperation between the municipality of Špania Dolina and the Banská Bystrica Geopark represent several strategic advantages that strengthen its position and contribute to more effective functioning in the region. The main benefits of the geopark are listed below. The importance of the benefits of cooperation mentioned below is also identified by the leading and respected author Brilha and his team in their research, where they say how important it is for the management structure to be able to effectively ensure integrated development of the territory and connect geopark staff, the entire community, and stakeholders [46]. The benefits can be divided between the geopark, the service provider (stakeholder) and the service recipient (tourist). This relationship and its impact on individual components can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The cycle of relationships and impacts of the active geopark-service providers-tourist approach.

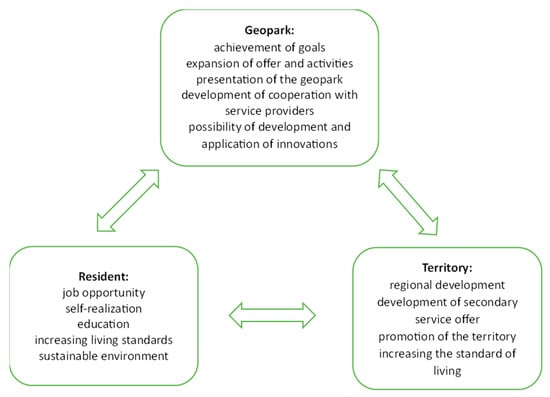

The benefits of cooperative management can also be seen inside the geopark, where it affects the geopark, the residents and the territory. Specific benefits can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The cycle of relationships and impacts of the active geopark-resident-territory approach.

Obtaining a strong territorial partner. Cooperation with the municipality of Špania Dolina provides the geopark with a stable and legitimate public partner that has a direct impact on the management of the territory. Thanks to the self-governing status of the municipality, it is possible to more effectively implement the geopark’s activities into the local environment and align them with the municipal spatial plans and development plans [47].

Deepening the relationship with the local community. The municipality plays a key role in connecting the geopark with residents and local actors, such as associations, craftsmen and entrepreneurs. Such a connection helps build trust, creates space for participation and supports a positive perception of the geopark as an initiative that takes into account the needs of local people. The Collaborative Process component shows that stakeholders are interrelated, and the Village Government has carried out various socialization activities, and open discussion also supports collaboration between stakeholders internally in the village and with external stakeholders. The outcome component shows that it is essential to formulate tourism development that can have a more optimal economic impact on the community and this opinion is also represented by the author Nuh and his team [48,49].

More effective planning and coordination. Through regular exchange of information on visitor numbers, infrastructure status, community expectations and seasonal needs, it will be possible to plan and adapt geopark activities to local conditions more precisely. At the same time, this will avoid organizational conflicts and increase the quality of prepared events.

Strengthening the regional significance of the geopark. Špania Dolina is considered one of the iconic cities of the Banská Bystrica region, thanks to its exceptional mining history, preserved urbanism and natural environment. The active operation of the geopark in this location increases its prestige, representativeness and ability to reach a wider audience from visitors to professional and institutional environments.

Benefits of cooperation for the municipality Špania Dolina bring several advantages that support its visibility, community development and sustainable use of cultural and natural potential. The main benefits of this cooperation are listed below.

Increasing the visibility of the municipality and its value potential. Cooperation with the Banská Bystrica Geopark will ensure wider promotion of Španá Dolina through its communication channels such as the website, social networks, information materials and exhibitions. This will increase awareness of the historical and natural values of the village not only among visitors, but also in the professional and development environment. The village is thus placed in a wider geographical and thematic context as an example of a well-preserved and active area with cultural heritage.

Development of community tourism. The Geopark supports forms of tourism that emphasize experience, education and respect for the local environment. The visitor population is not focused on mass commercial products, but on smaller thematic groups, schools, families and experts. This type of tourism is in line with the character of Španá Dolina and at the same time creates opportunities for the involvement of local craftsmen, guides, service operators and residents in activities with meaningful content.

Cooperation in the creation of programs and events. As part of the partnership with the Geopark, the municipality can actively participate in the preparation of programs, exhibitions, guided tours or educational activities. This means not only the opportunity to present local topics and personalities, but also to directly influence the content and format of events so that they correspond to the community and local conditions. This process also supports civic engagement and a co-ownership approach to organized activities.

Support for the sustainable development of the municipality. Cooperation with the geopark creates a framework for the implementation of projects that combine the protection of natural and cultural heritage with educational, social and economic functions. These can include activities such as revitalization of public spaces, restoration of small monuments, creation of community exhibitions, support of traditional crafts or environmental education. Such initiatives strengthen the long-term sustainability of the village as a living space that preserves its character while offering a quality of life to residents and visitors. As an example, it is necessary to mention a significant study promoted in his article [48] by the author Shahhoseini and his team. He applied the study to the territory of Qeshm National Geopark, Iran, where he found that increasing employment opportunities is one of the most significant impacts of geotourism and according to the survey, 81% of people are very satisfied with the development of this industry in the region. Another significant positive impact of geotourism development is the creation of ethnic and cultural pride among local residents. Cultural capital turned out to be the most influ-ential variable. The survey findings also showed that the promotion and development of geotourism in Qeshm requires more organized programs and a stronger contribution from local communities [50].

Cooperation with Pension Klopačka opens up new possibilities for the Banská Bystrica Geopark in the field of organizing activities. The main benefits of this cooperation are listed below.

Obtaining quality facilities without the need for investment in infrastructure. Cooperation with Pension Klopačka allows the geopark to carry out activities in an already existing, functional and culturally valuable space. This way, the geopark avoids demanding investments in the construction or reconstruction of its own facility. Pension Klopačka represents a “natural epicenter” of local stories of mining, crafts, geology, and its architecture and location are beneficial for education and tourism.

Strengthening the presence of the geopark in an important location. Špania Dolina is one of the most important areas of the Banská Bystrica Geopark due to its historical, geological and touristic significance. Cooperation with the Klopačka Guesthouse will provide the geopark with a solid foundation for organizing geotourism activities, such as nature trips, excursions and experience programs. It will also allow for deeper cooperation with the local community and the development of sustainable forms of tourism directly in the region.

Creation of a new information and educational center. A smaller information center may be created in the guesthouse premises, which will introduce visitors to the ideas of the geopark through exhibitions and interactive elements. This will also fulfill an educational, informational and promotional function.

Presentation of the geopark in an authentic environment. The implementation of geotourism activities directly in the premises of the historical building of the Klopačka Guesthouse allows the geopark to be presented not only as a natural, but also as a cultural and historical space. Visitors will thus learn about the geological and mining heritage directly on the site, which is historically connected to this heritage. The connection of natural content with architecture, local history and the atmosphere of the former mining environment increases the experiential, authenticity and educational effect of geotourism.

The expected benefits of cooperation for Klopačka also bring several advantages for the guesthouse itself. The main benefits of this cooperation are listed below.

Increased occupancy throughout the year. An important factor in the protection of any site is the number of visitors. The author Drápela and his team described a case study conducted in the Bohemian Paradise Geopark [51], where they point out the imbalance in the number of visitors to sites that suffer from excessive time tourism in the main season. On the other hand, more than half of the geopark is not so often visited by tourists, although there are also very attractive geosites. In the most visited sites, nature is damaged due to overloading of the tourist infrastructure, while elsewhere there is pressure from municipalities to increase the number of tourists [52]. Cooperation with the geopark will allow Penzión Klopačka to target new groups of visitors, such as school groups, professional excursions or thematic groups, which usually carry out their activities outside the main tourist season (e.g., April–June, September–November). At the same time, it is possible to organize educational, gastronomic events, workshops, etc. This will contribute to expanding the clientele and increasing the occupancy of the facility throughout the year.

Addressing new target groups. Closely related to the previous point. Cooperation with the geopark will expand the clientele of the Klopačka Guesthouse to include visitors who prefer a meaningful and value-oriented stay over classic relaxation. These include mainly schools, universities, interest and professional groups, but also individual guests with an interest in nature, geology, geotourism, or traditional culture and crafts.

Free promotion through the geopark’s communication channels. As an official partner of the geopark, the Klopačka Guesthouse will receive a benefit in the form of free promotion through the geopark’s communication channels, which include a website, social networks, and printed materials such as maps, brochures, and leaflets. Social networks have become the glue and bind each actor so that they function as a basic element to form a good collaboration [53,54].

Increasing awareness of the historical value of the facility. The Klopačka Guesthouse, as a former mining facility, has a high cultural and historical value, which, however, is not always sufficiently known to the general public. Thanks to cooperation with the geopark, this value can be communicated more effectively to visitors and the local community. The Geopark can help with the professional creation of information boards, interactive panels, accompanying texts, and thematic exhibitions that will present the story of Klopačka in the context of the mining history of Španá Dolina and the region.

Expected benefits for the Banská Bystrica Geopark of cooperation with the Center for Folk Art Production (CFAP) represents a significant opportunity to enrich the geotourism offer with elements of intangible cultural heritage. The main benefits of this cooperation are listed below.

Expansion of the program offer with intangible cultural heritage. Cooperation with CFAP will allow the geopark to expand its offer of activities to include the area of intangible cultural heritage, represented by traditional crafts and craft techniques. These activities build on local historical traditions and at the same time bring visitors a new dimension of knowledge, based on practical experience and skills. Including crafts in geotourism programs strengthens the complexity of the geopark’s offer and creates greater diversity for different types of visitors.

Possibility of cooperation with a professional institution with a long-standing tradition. CFAP, as an institution with long-term experience in the field of documenting, supporting and protecting crafts, represents a valuable partner for the geopark. His professional background, experience in organizing exhibitions, teaching workshops and cooperating with certified manufacturers create space for high-quality event preparation. The Geopark will thus gain access to methodological materials, contacts with verified craftsmen and know-how, which will enable it to organize professionally led activities with high added value.

Support for local traditions and identity of the area. One of the significant benefits of cooperation is also the strengthening of local cultural identity. Traditional techniques, such as bobbin lace of Špania Dolina, are a unique element of the cultural heritage of the region. Their inclusion in the educational and tourist activities of the geopark allows for their preservation, revival and dissemination among visitors and local residents. It helps to raise awareness of the value of intangible cultural heritage. The author Fiorentino [53] discusses the consequences of the loss of historical and cultural testimonies, which have a direct impact on the territory and its local communities. This leads to the loss of social cohesion, identity values and resources that come from sustainable tourism. Although international action frameworks (Hyogo Framework for Action, Sendai Framework for Action and the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals) emphasize the importance of recognizing the relationship between heritage, society and territory, a strategic and sustainable vision of participatory conservation and protection is still needed at the local level [55].

Increasing attractiveness for new target groups. Cooperation with CFAP expands the target audience of the geopark to include visitors who would otherwise not be primarily interested in purely geologically focused activities. This increases the accessibility and openness of the geopark to the wider public. Traditional craft techniques, creative workshops and craft demonstrations are particularly attractive for families with children, school groups, as well as for interest groups focused on folk art, mining history and regional traditions. Such diversification of the offer increases the social impact of the geopark.

The cooperation between the CFAP and the Banská Bystrica Geopark brings several advantages for the CFAP institution itself and its craftsmen. The main benefits of this cooperation are listed below.

Expansion of sales points for certified products and creation of space for new geoproducts with a craft basis. Cooperation with the geopark opens up new opportunities for the CFAP and its certified producers to sell products outside of traditional brick-and-mortar stores. Sales points within the geopark points, such as information centers, accommodation facilities or thematic events, will make it possible to bring authentic craft products closer to visitors directly in the region. At the same time, space is created for the creation of new types of geoproducts—for example, products with landscape, geology or traditional patterns that connect the craft with the story of the territory.

Strengthening the economic stability of the craftsmen involved in the cooperation and creating demand for authentic, handmade production. By increasing the presentation and sale of craft products, the visibility and demand for the work of specific craftsmen also increase. Geotourism programs create a space for the encounter between the craftsman and the visitor, which strengthens the personal dimension of the craft and increases its perceived value. This demand helps craftsmen to stay in practice, motivates them to further develop and creates the basis for sustainable income from an activity that has cultural and social significance.

Making traditional crafts visible directly in the field. Unlike galleries or craft centers in cities, cooperation with a geopark brings the opportunity to present crafts in the natural context of the landscape where they historically originated. The visitor can thus get to know traditional creation not only as a final product, but as a process linked to natural resources, location, way of life and cultural environment. This makes the craft part of the landscape and its story, which significantly increases its educational and experiential potential.

Supporting the preservation and generational transmission of craft techniques. Activities implemented in cooperation with the geopark allow presenting craft techniques as a living part of the region, not just as a historical memory. Workshops, creative workshops and demonstrations allow conveying skills to the younger generation and at the same time arouse interest in learning traditional techniques. In the context of geotourism, this is an exceptional tool for connecting natural and cultural heritage and a way to ensure the long-term preservation of craft skills such as lacemaking, pottery, carving or processing of natural materials.

Cooperation with the Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood brings several advantages to the Banská Bystrica Geopark, especially in the area of professional interpretation of mining heritage and expansion of the experience offer. The following section lists the specific benefits that this cooperation brings to the geopark.

Acquiring a professional partner for the interpretation of mining heritage. The Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood represents an important partner in the area of interpretation and presentation of the history of mining in the region. Thanks to its long-standing presence, personal connection with the local environment and the preservation of traditional forms of guiding, the brotherhood is able to convey historical information in an engaging and authentic way.

Increasing the value of the geotourism offer. Cooperation with the brotherhood allows the geopark’s geotourism offer to be expanded by a significant cultural and community dimension. By including the Copper Museum and the Mining Educational Trail in the structure of the geopark’s experience programs, the complexity of the offer increases. Visitors have the opportunity to perceive not only geological processes, but also their historical and social contexts. Communities are pivotal in the successful execution of diverse development programs within geopark [56].

Access to verified information from the field of mining and history. The Herrengrund Mining Brotherhood manages valuable historical spaces, collections and objects related to the mining past of Španá Dolina—for example, insignia, equipment or artifacts related to copper mining. Thanks to this, the geopark has the opportunity to draw on accurate and trustworthy sources when creating information panels, educational materials or guide texts. This increases the quality of the interpretation, strengthens the local context and brings visitors content that is professional, but at the same time close to the place where they are.

Expected benefits for Herrengrund open up new possibilities for development and strengthening of its activities. This section presents the main benefits that the brotherhood can gain through the partnership.

Increased attendance and awareness of the brotherhood’s activities. Cooperation with the geopark will provide the brotherhood with greater visibility and reach a wider audience. Including the Copper Museum and the Mining Trail in the official programs of the geopark will increase the number of visitors, which will contribute to greater interest in the brotherhood’s activities and the mining history of Španá Dolina. Thanks to promotion via the web, printed materials and joint events, the perception of the brotherhood as an active bearer of cultural heritage will be strengthened.

Financial and organizational maintenance of the activity through participation in tourist packages. A higher number of visitors means greater interest in the brotherhood’s activities, which creates a prerequisite for regular participation in regional tourism. Such activities can become a stable source of income that the brotherhood can use to cover operating costs, maintain facilities, or organize its own cultural events. At the same time, they provide a framework for long-term planning and increase the financial and organizational sustainability of their activities.

Greater continuity and relief from organizational burden. Thanks to cooperation with the geopark, the Mining Brotherhood can receive support in organizing its activities. The geopark will help with promotion, reservations, and technical support, thus relieving the brotherhood of time-consuming and administrative tasks. Members will then be able to devote more time to the essential interpretation, guiding visitors, and caring for collections and traditions. Such support will also contribute to greater stability and regularity of their activities.

6. Conclusions

Given the wide range of activities that geoparks undertake, from education and popularization of science and nature protection to the development of geotourism, their activities require stable and multi-source financial security. Slovakia still lacks a unified system of state support for geoparks. Funding is therefore often dependent on the initiative of local actors, project grants, support from local governments, or partner organizations. This model leads to significant differences in the economic stability of individual geoparks and also affects the scope and quality of their activities.

The educational product Copper Thread of the Španej Dolina represents a unique example of how the cultural and natural heritage of the region can be connected with modern forms of education and sustainable tourism in an authentic, experiential, and above all, sustainable way. It is based on synergy between professional institutions, local government, community actors, and the business environment, with each partner contributing to the cooperation with its specific resources and knowledge. The package is the result of comprehensive planning, field analysis, and a value-based approach to the territory. Its aim is not only to engage the visitor, but above all to deepen their relationship with the place, support the knowledge of local identity, and create a space for community development. It is the combination of education, interactive discovery, and experience of the place that makes the package a functional tool for environmental and cultural awareness, suitable for a wide range of visitors. At the same time, the product provides a new impetus for regional development, increases visitor numbers outside the main season, addresses new target groups, supports local craftsmen, raises awareness of historical values, and offers space for further expansion and updating.

The entire proposal is based on the principles of cooperative management, which provides a framework for long-term partnership, coordination, and effective management of cooperation between the involved entities. Its essence is not to achieve profit for partners, but is based on a balanced and equal relationship, on the use of mutual values of stakeholders, mutual support, and awareness of the added value of this relationship, which will result in the development of the given territory. In the future, it seems important to embed cooperative approaches in strategic documents at the national and regional levels. Better support from the state and a clearly defined position of geoparks in the tourism system could significantly contribute to their stability and the effective functioning of partnerships in the territory.

The proposed model, after active consultation with representatives of the Banská Bystrica Geopark, will be gradually applied. Its activities at the level of cooperation will acquire formal and structured lines, and the level of cooperation will acquire a coordinated and managed character. By applying and subsequent gradual feedback from all stakeholders, a methodological manual for cooperation management in the geopark will be prepared, which will have general lines and will provide a guiding and advisory platform for geoparks in the Slovak Republic. The manual will serve as a general material for geoparks within the Slovak Republic as a model of instructions for cooperation of emerging and already existing geoparks. Since geoparks have lacked such material so far, the topic of the article is the first concrete step towards creating and sharing valuable information for the introduction of an effective model of cooperation between entities in the geopark, which provides mutual benefits. After applying the model, the subject of further research in the near future is primarily the analysis of measurable outputs such as attendance, the number of future formal cooperation agreements concluded, and the active approach of all stakeholders.

Other entities are those that also fulfill the main goals of the geopark, such as education, protection, promotion in geosciences, and regional development. It would be appropriate to identify key groups of entities according to these goals, and what geoparks actually have done. The next step in development will be to address educational institutions with the aim of starting cooperation in the form of active involvement of students in practice. From their portfolio, we would select: educational institutions such as a university focused on the study of geosciences, conservation institutions such as State nature protection, promotion of geosciences, e.g., destination organization of the tourism, regional development, e.g., local producers. Educational institutions are very important subjects in general in fulfilling the function of a geopark. When expanding the model and designing a general methodology applicable to geoparks, it is necessary to highlight the position of educational institutions in this process. Since education at any level is key.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and E.K.; validation, C.D.; formal analysis, L.B.; investigation, E.K.; resources, C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was supported by VEGA 1/0328/25, Strategy for the effective and sustainable use of Earth Resources within the Slovak Republic, with an emphasis on the Raw Materials Policy of the EU& by the Horizon 2020 project, no. 101180341 Interregional EU innovation Hubs for the circularity and green supply of Raw Materials to achieve the resilience of the main underdeveloped regions specialised on the critical industrial value chain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the management of the Banská Bystrica Geopark for their friendliness and helpful approach to the topic “about the current state of management in geopark”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFAP | The Centre of Folk Art Production |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

References

- Eder, W.; Patzak, M. Geoparks—Geological attractions: A tool for public education, recreation and sustainable economic development. Episodes 2004, 27, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.G.; Queiroz, D.S.; Mucivuna, V.C. Geological diversity fostering actions in geoconservation: An overview of Brazil. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2022, 10, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, B.; Németh, K. Spatial decision-making support for geoheritage conservation in the urban and indigenous environment of the Auckland Volcanic Field, New Zealand. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2023, 530, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, B.; Németh, K.; Procter, J.N. Visitation rate analysis of geoheritage features from earth science education perspective using automated landform classification and crowdsourcing: A geoeducation capacity map of the Auckland volcanic field, New Zealand. Geosciences 2021, 11, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Global Geopark 2025. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks/about (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Zouros, N. The European Geoparks Network: Geological heritage protection and local development. Episodes 2004, 27, 165–171. Available online: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/258100233_The_European_Geoparks_Network_Geological_heritage_protection_and_local_development (accessed on 21 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Holubčík, M.; Soviar, J. Identification of Elements of Strategic Management of Selected Methods And Tools as a Basis for Management of Cooperation. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Górnośląskiej 2023, 4, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, M.; Justice, S.; Olsbo, R.; Balzarini, P.; Magagna, A.; Viani, C.; Selvaggio, I.; Kiuttu, M.; Kauhanen, J.; Laukkanen, M.; et al. ERASMUS+ Strategic Partnerships between UNESCO Global Geoparks, Schools, and Research Institutions: A Window of Opportunity for Geoheritage Enhancement and Geoscience Education. Heritage 2022, 5, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Watanabe, T. A new partnership framework for education with geoparks at its core: A proposal through the evaluation of the school education program in Shikaoi, Japan. Geotourism/Geoturystyka 2024, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šambronská, K.; Matušíková, D.; Šenková, A.; Kormaníková, E. Geoturism and Its Sustainable Products in Destination Management. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningtiyas, L.; Rambe, S.; Cahyana, A. Typology of Stakeholder Interaction and Factors Influencing the Management of Ijen Crater Nature Tourism Park. J. Ilm. Telsinas Elektro Sipil Dan Tek. Inf. 2025, 8, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, I.; Iksanov, R. Directions of legislative regulation of activities on creation and organization of geoparks. Vestnik Bashkir Inst. Soc. Technol. 2022, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Ciobanu, C.; Andrășanu, A.; Marin, S. Geoproducts. Local Stories Included in International Branding. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excel. 2025, 19, 3792–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatyinszki, S.; Kálmán, B.G.; Dávid, L.D. The Role of Geoparks in Sustainable Tourism Development. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2025, 59, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouros, N.; Valiakos, I. Geoparks Management and Assessment. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2010, 43, 965–977. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303286685_Geoparks_management_and_assessment (accessed on 21 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Geopark Management Toolkit. Governance and Management 2025. Available online: https://www.geoparktoolkit.org/governance/#GM4 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Vasiliev, D.; Bornmalm, L.; Stevens, R. The Potential Role of Geoparks in Nature Positive Agenda. In Proceedings of the SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference EXPO Proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 1–7 July 2024; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichinadze, T. Planning of Geopark and Its Perspectives in the Caucasus on the Example on the Racha Region. In Proceedings of the 20th SGEM International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 16–25 August 2020; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendel, V.; Soviar, J.; Vodák, J. Creation of Corporate Cooperation Strategy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attolba-Aquino, R.; Castañeda, M. Implementation and Effectiveness of Sustainable Cooperative Management Practices. J. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 3, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staatz, J.M. The cooperative as a coalition: A game-theoretic approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1983, 65, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerakumaran, G. COCM 511–Management of Cooperatives and Legal Systems. Course Materials; Faculty of Dryland Agriculture and Natural Resources, Ethiopia Mekelle University: Mekelle, Ethiopia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, S.; Han, X.; Wang, W.; Li, H. A Study of the Dynamic Evolution Game of Cooperative Management by Multiple Subjects Under the Forest Ticket System. Forests 2025, 16, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Berkes, F.; Doubleday, N. Adaptive Co-Management: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232273249_Adaptive_comanagement_Collaboration_learning_ad_multi-level_governance (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Meythi, M.; Martusa, R.; Rukmana, A. Institutional strengthening of youth organization towards green economy. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Econ. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janamjam, C.; Rabanes, P.J. Digital Transformation in Cooperative Management: The Case of Multipurpose Cooperatives. J. Manag. World 2025, 2025, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risal, N. Cooperative Management; Advance Saraswati Prakashan: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vodak, J.; Soviar, J.; Lendel, V. Identification of the Main Aspects of Cooperation Management and the Problems Arising from their Misunderstanding. Komunikacie 2014, 16, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agussalim, A.; Achmad, A. Cooperatives: Problems and Sustainable Strategy Management. J. PenKoMi Kaji. Pendidik. Dan Ekon. 2025, 8, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Anggoro, D.; Ramadhan, H.; Ngindana, R. Public Private Partnership in Tourism: Build Up a Digitalization Financial Management Model. Policy Gov. Rev. 2022, 6, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]