Abstract

Based on niche theory, this study pioneered the application of the niche state-role model, suitability model, subgroup model, and overlap model in evaluating small-town communities, integrating both their endowment attributes and relational attributes. Taking Pingshan County, Hebei Province, China, as a case study, it revealed the evolution patterns of suburban small-town communities from 2000 to 2020. The results indicated significant changes in the comprehensive niche indices and rankings of small-town communities, though top-ranking towns remained relatively stable. Niche indices varied from dimensions, primarily manifesting a binary opposition between natural and humanistic factors. The overall suitability of small-town communities showed little change, but internal disparities gradually narrowed. The niche subgroups of small-town communities displayed a gradient distribution pattern: ecological functions significantly strengthened in the west of the county; population and economy functions continuously intensified in southeastern towns; while central-region towns maintained intermediate levels. Regarding niche overlap based on population and economy flows, the overall competitive intensity of small-town communities weakened, but competition among central region towns intensified. Regarding niche overlap based on ecology flows, the overall competitive intensity strengthened, with particularly notable changes in the central and eastern regions. Moreover, the spatial evolution of county-level small towns exhibited scale-dependent differences: while the macro-scale pattern remained relatively stable, the micro-scale pattern underwent significant changes, with the driving force gradually shifting from local endowments to factor flows.

1. Introduction

Small towns, a type of settlement intermediate between cities and rural areas, constitute a fundamental structural element within the urban–rural settlement system [1]. Continuous element flows between small towns foster their mutual dependence and symbiotic development, forming organically interconnected communities [2,3]. Small-town communities represent both the systemic integrity and the coopetitive relationships within the small-town system, and serve as a key platform for regional sustainable development and spatial governance [4,5,6].

The term “community” is a core concept in ecology, referring to an ecosystem formed by the competition and cooperation among biological populations and their interactions with the habitat [7,8,9]. It has since been applied to the study of town communities. Currently, research and policies on small-town communities domestically and internationally primarily focus on metropolitan areas, where small towns possess stronger developmental foundations and exhibit more pronounced transformation characteristics [10,11]. Research on economically underdeveloped areas and metropolitan peripheries remains inadequate, especially in the remote suburban areas of developing countries [12]. More than half of small towns in China are situated in the metropolitan fringe. As critical nodes for urban-rural factor exchange and rural service provision, they face significant constraints in resources, economy, and innovation endowments, making their transformation and governance an urgent priority [13]. Concurrently, small-town community research includes four key aspects: spatial structure [14,15], industrial structure [16,17], influencing factors [18,19], and optimization strategies [4,20]. Some studies employing cross-sectional data have uncovered significant regional and typological variations among these communities [8,21]. For instance, Meili et al. demonstrated that socio-economic heterogeneity of small-medium towns in Swiss was influenced by regional environments, industries, population size, and agglomeration, while inter-town connectivity intensity exhibited strong correlation with town typology [21]. Some panel data studies indicated small-town communities were undergoing differentiating development [15,22]. Gong et al. revealed, using the case of Jiangyin City in China, that the spatial pattern of the small-town communities transitioned from complete dispersion to small agglomeration and then to large agglomeration [15]. Hu et al. revealed, using the case of Guangxi Province in China, that a developmental gap existed between the southeastern and northwestern regions among small towns, with the overall disparity narrowing [22]. Existing research has remained predominantly material-function oriented, relying on statistical, regression, and cluster analysis, while it has afforded insufficient attention to inter-town factor mobility and co-opetition relationships. A particular shortcoming is the absence of methodologies that bridge endowments and relationship.

Niche theory serves as a pivotal methodology in urban community research. Initially proposed by American ecologist Grinnell, it explains how a species occupies a specific position within a community ecosystem and interacts with both the environment and other species through co-opetition [23]. Since the 1980s, scholars in both China and the West have pioneered the application of niche theory to urban community studies. They have constructed evaluation frameworks for urban community niches across economic and social dimensions, revealing adaptive, competitive, and symbiotic patterns within regional environments [24,25,26]. Methodologies encompass niche state-role model, breadth model, suitability model, and overlap model [27,28,29,30]. Data includes both static attribute data and dynamic relational data. Since the beginning of the 21st century, a small number of scholars have started to apply insights from urban niche research to the study of town communities [31,32]. However, there is relatively less empirical research on small-town niches, and it has not yet fully drawn upon the methods of urban niche studies.

In summary, prior studies on small-town communities have inadequately addressed the evolution patterns of those situated in remote suburban areas, while lacking methodologies to integrate endogenous endowments and relational dynamics. Although urban niche theory provides a novel analytical framework capable of effectively synthesizing regional functions and factor flows, its application to small-town community research remains markedly underutilized. This study applies niche theory to suburban small-town community research, selecting Pingshan County in Hebei Province, China, as the case area to address two primary objectives: (1) Establish a comprehensive niche evaluation framework for small towns by integrating their endowment attributes with relational attributes. This framework employs four analytical models—the niche state-role model, niche suitability model, niche subgroup model and niche overlap model—to assess functional capacity, environmental adaptability, subgroup dynamics, and competitive relationships within these communities. (2) Analyze the evolutionary patterns of small-town communities from 2000 to 2020 using these niche models, thereby summarizing developmental stages and identifying principal driving forces.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

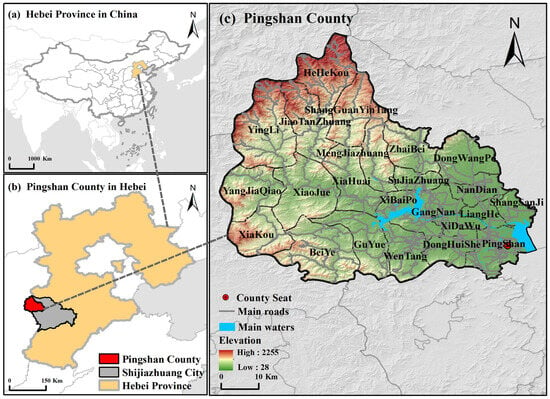

Located in the western periphery of Shijiazhuang City, Hebei Province, Pingshan County shares its western border with Shanxi Province and lies approximately 46 km east of Shijiazhuang’s urban core (Figure 1). The county spans the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains, covering a total administrative area of 2648 km2 with mountainous terrain accounting for 73.8% of its land area. Since 2000, Pingshan County has undergone distinct developmental phases—industrialization, urbanization, and ecological conservation—accompanied by rapid evolution and restructuring of its small-town communities. As of 2020, Pingshan County’s administrative framework consisted of 23 towns, with Pingshan Town functioning as the county seat. The county achieved a Gross Regional Product (GRP) of CNY 24.8 billion, with a per capita GDP of CNY 49,706. Demographic statistics showed a permanent resident population of 423,333 and an urbanization rate of 51.95%, which fell below both the national and provincial averages. The annual per capita disposable income registered CNY 11,229 for rural residents and CNY 34,181 for urban residents, indicating ongoing urban–rural income inequality.

Figure 1.

Location of Pingshan County in China.

Currently, Shijiazhuang City’s per capita GDP remains below the national average, rendering it a relatively weak provincial capital with limited capacity to radiate development towards Pingshan County. In 2025, the State Council approved the Shijiazhuang Metropolitan Area Development Plan, which notably excluded Pingshan County while designating it as a key ecological function zone. This status reaffirms Pingshan’s role as a typical suburban county where small-town communities evolve mainly through endogenous growth. Therefore, this study selects Pingshan County as a representative case to investigate the evolution patterns of suburban small-town communities. In this context, “small towns” refer specifically to administrative towns, of which Pingshan County administers a total of 23.

2.2. Data Sources

This study integrated three primary datasets at the small-town scale: socio-economic statistics, land use information, and transportation network data. Socio-economic data were sourced from the Pingshan Statistical Yearbook, Hebei Provincial Township Economic Yearbook, and the decennial National Population Census [33,34,35,36]. Land use data originated from 30 m resolution annual land cover data “https://zenodo.org/records/12779975 (accessed on 20 November 2025)”, which classify land into nine standardized categories: cropland, forest, shrub, grassland, water, wetlands, permanent ice/snow, impervious surfaces, and bare land. Transportation network data were obtained from two leading Chinese geospatial data platforms: the Peking University Geospatial Data Platform “https://geodata.pku.edu.cn/index.php (accessed on 20 November 2025)” and the Resources and Environmental Science Data Center, CAS “https://www.resdc.cn/data.aspx?DATAID=237 (accessed on 20 November 2025)”. Digital elevation model were obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud based on 30 m ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) products “https://www.gscloud.cn/search (accessed on 20 November 2025)”. All data were selected for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020.

2.3. Research Method

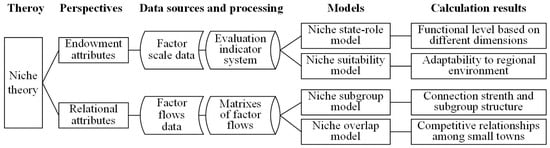

This study selected four models: the niche state-role model, niche suitability model, niche subgroup model, and niche overlap model (Figure 2). The niche state-role model was used to analyze the multidimensional functional levels and evolution of small towns, and the niche suitability model was employed to assess their adaptation to the regional environment and quantify gaps relative to an ideal state [27,28,37]. Both models were computed based on factor-scale data by constructing an indicator system for factor evaluation, and aimed to reveal the resource occupancy status and development potential of the studied towns. The niche subgroup model was utilized to analyze the subgroup relationships of element flow network, and the niche overlap model was used to reveal the competition and cooperation among small towns regarding regional resources [30,37]. Both models were computed based on factor–relationship pair data by constructing a factor flow matrix, and they aimed to reveal the internal competitive dynamics and functional clusters within the small-town communities.

Figure 2.

Methodology framework.

2.3.1. Niche Models Based on Factor Scale

- (1)

- Evaluation indicator system of niche factor

The niches of small towns encompass multiple dimensions, representing the diverse functions and values of small towns. Based on the multidimensional hypervolume niche model, the niche of each small town is conceptualized as the development space and potential shaped by multidimensional environmental factors [37]. In this study, adhering to the principles of objectivity, comprehensiveness, and ensuring data availability and measurability, nine indicators spanning five fundamental dimensions were selected. The entropy weight method [38] was employed to calculate the weight of each indicator (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation indicator system of niche factors of small-town communites.

- (2)

- Niche state-role model

The niche state-role model entails calculating the “state” (the status at a specific time point) and “role” (the average rate of change over a time period) to derive a comprehensive niche index [37]. The study used data in 2010 and 2020 for state quantification, and calculated the role based on the average change rates during 2000–2010 and 2010–2020. Computational formulas were provided in Equation (1). The comprehensive niche index (Equation (2)) aggregated weighted niche dimensions. A higher value signifies a stronger position within the community hierarchy, greater resource dominance, and enhanced operational efficiency. Conversely, a lower value reflects reduced resource utilization efficacy.

In the formula, denotes the niche value of the -th indicator for the -th small town; represents the standardized value reflecting the current development status of the -th indicator for the -th small town; signifies the standardized value reflecting the development potential of the -th indicator for the -th small town. denotes the comprehensive niche value for the -th small town, and the niche values range from 0 to 1; signifies the weight assigned to the -th indicator. is a dimensional conversion coefficient.

- (3)

- Niche suitability model

Niche suitability measures the proximity between the actual niche and the optimal niche, thereby reflecting a small town’s environmental adaptation capacity. A value closer to 1 indicates that the town’s actual development is more aligned with its ideal state. The calculation formula is provided as follows:

In the formula, denotes the niche suitability for small town . represents the absolute difference between the actual niche and the optimal niche for that factor. Here, the actual niche is the observed value of factor for small town , while the optimal niche is defined as the maximum value of factor observed across all small towns. is the minimum absolute difference from the optimal niche observed (closest to optimal), and is the maximum absolute difference from the optimal niche observed (farthest from optimal). is a model parameter, which takes values within the interval [0, 1].

2.3.2. Niche Models Based on Factor Flows

- (1)

- Matrixes of niche factor flows

This study constructed three 23 × 23 multi-valued directed matrixes representing population, economic service, and ecological service flows, respectively. Each matrix captures the intensity of factor exchanges between pairs of small towns [37].

① The population flow matrix was established by a modified gravity model [39], based on registered population data, industrial output value, and spatial distance of small towns.

In the model, denotes the population flow intensity from small town to small town , represents the gross industrial output value, and signifies the spatial distance between the two towns.

② The economy flow matrix was constructed by the gravity model [40]:

In the formula, denotes the Location Quotient for each industry; represents the number of employees in industry in small town ; signifies the total number of employees in small town ; is the total number of employees in industry across Pingshan County; and is the total number of employees across all industries in Pingshan County. denotes the external economic value of the small town, represents the total number of employees engaged in basic economic activities in the small town, and signifies the economic value generated by the basic economic activities in the small town. denotes the economic service flow intensity from small town to small town , represents the industrial output value of the basic economic activities, and signifies the actual distance between the two towns.

③ Ecology flow refers to the intensity of ecological service element movements such as biological migration, material exchange, and energy flow between small towns. The Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) model was used to extract the largest ecological source areas within each town as starting points [41]. The Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model was then employed to calculate the cost distance surface of these ecological sources [42], and finally, the gravity model was applied to derive the ecology flow matrix [43]:

In the formula, denotes the ecological service flow intensity from town to town ; and represent the area of the ecological source in the town and the total area of the town , respectively; signifies the average minimum cumulative resistance between the ecological source of town and town . With reference to existing studies [37], the weights and resistance values for each resistance layer were ultimately assigned as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Weight coefficient of each resistance layer and corresponding resistance value.

- (2)

- Niche subgroup model

Niche subgroups refer to groupings formed by small towns based on the relational states of niche factors. Analyzing these subgroups offers a micro-scale lens through which the spatial organization and evolutionary dynamics of small-town communities can be elucidated. Within the framework of social network analysis, community detection models function as instrumental tools for identifying such cohesive subgroups, based on the strength of small-town node connections [44]. Accordingly, this study applied the Concor algorithm, a specific method of community detection model, to investigate the distribution patterns of niche subgroups across varying conditions of factor flow [45].

- (3)

- Niche overlap model

Niche overlap refers to the overlap in niche volumes between small towns, signifying their niche similarity and reflecting respective resource utilization patterns and competitive relationships. Where niches overlap, competitive exclusion effects arise; conversely, completely disjunct niches preclude competition, thus ensuring each town maintains a stable niche [37]. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, denotes the niche overlap index, which ranges from 0 to 1. A higher value indicates greater niche proximity between small towns and for a specific factor flow, signifying stronger competitive pressure. represents the normalized value of the factor flow.

3. Results

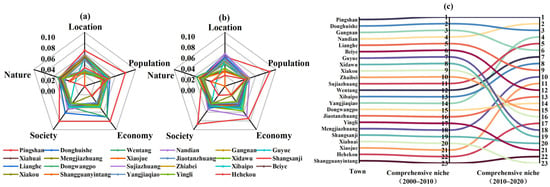

3.1. Evolution of Niche Indices in Small-Town Communites

The niche indices of small towns across distinct dimensions are presented in Figure 3a and Figure 3b, respectively. Regarding natural factors, inter-town differences in niche indices were relatively minor and remained largely consistent over time. For locational factors, disparities between small towns gradually narrowed. In the population and society dimension, Pingshan Town exhibited the highest niche index, with a widening disparity relative to other towns, whereas inter-town differences among the remaining towns progressively decreased. Within the economy dimension, Pingshan Town recorded the highest niche index, while Nandian Town demonstrated the most rapid growth. Collectively, these patterns reflect a regional transition from polarized development toward gradient development. The analysis reveals substantial divergence in dimensional niche patterns across Pingshan’s small-town communities, with varying magnitudes of change observed among different dimensions. Notably, Pingshan Town maintains dominant niche advantages across demographic, social, and economic dimensions—a phenomenon largely attributable to its county-seat status and superior administrative positioning. Although Nandian Town has accelerated its industrial and transportation development, emerging as a secondary economic center that partially closes the development gap with Pingshan, it continues to exhibit significant constraints in demographic attractiveness.

Figure 3.

Niche indices based on different dimensions and comprehensive niche ranking of small-town communites. (a) Niche indices based on different dimensions during 2000–2010. (b) Niche indices based on different dimensions during 2010–2020. (c) Comprehensive niche ranking.

The comprehensive niche indices of small towns in Pingshan County demonstrated substantial ranking variations from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 3c). The developmental pattern of small-town communities exhibited dynamic characteristics, with Pingshan Town, Donghuishe Town, Gangnan Town, and Nandian Town maintaining their dominant positions throughout the study period. Notably, Pingshan Town consistently ranked first in the niche index rankings, while other towns experienced significant fluctuations in their relative positions, suggesting intensified competitive pressures.

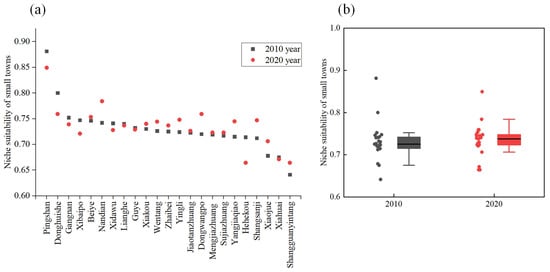

3.2. Evolution of Niche Suitability in Small-Town Communites

Figure 4 illustrates the niche suitability of small-town communities in Pingshan County. Between 2010 and 2020, niche suitability values ranged from 0.64 to 0.88 and from 0.66 to 0.85, with mean values of 0.73 and 0.74, respectively. Overall, the development level of small-town communities remained relatively stable, while the disparities among them diminished. In particular, nine towns experienced a continuous decline in niche suitability from 2010 to 2020—most of which were concentrated in the eastern part of the county. In contrast, the remaining 14 towns, largely situated in the western and central regions, exhibited an upward trend in suitability. Leading towns—including Pingshan, Donghuishe, Gangnan, and Xibaipo—showed a marked decline in niche suitability rankings, whereas the other towns demonstrated significant improvement.

Figure 4.

Niche suitability of small-town communites in 2010 and 2020. (a) Scatter plot. (b) Box plot.

3.3. Evolution of Niche Subgroups in Small-Town Communities

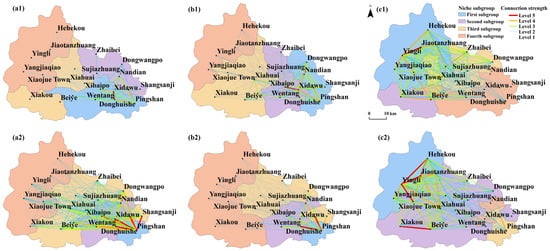

Based on the niche subgroup model, the small-town communities in Pingshan county were divided into four subgroups. The results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Niche subgroups of small-town communities based on different niche factor flows. Niche subgroups based on population flows in 2010 (a1) and 2020 (a2). Niche subgroups based on economy flows in 2010 (b1) and 2020 (b2). Niche subgroups based on ecology flows in 2010 (c1) and 2020 (c2).

From the perspective of population flow (Figure 5(a1,a2)), in 2010, the distribution of niche subgroups exhibited clear north–south and east–west disparities. By 2020, the four subgroups demonstrated a distinct gradient distribution pattern along a southeast–northwest axis. The spatial configurations of the first, second, and third subgroups underwent significant changes, whereas those of the fourth subgroup remained relatively stable. These shifts suggest a trend of population concentration in small towns located in the southeastern part of the county, a weakening attractiveness of central regions to population inflow, and the persistence of developmental disadvantages in western regions. From the perspective of economy flows (Figure 5(b1,b2)), the spatial domains of the first and second subgroups underwent significant contraction, with their geometric centers shifting southeastward. Conversely, the spatial range of the fourth subgroup expanded notably. This spatial reorganization indicates a widening disparity in the economic niche among small-town communities, manifesting as an intensifying divergence between the eastern and western regions, as well as between the southeastern and northeastern parts of the county. Analysis of ecology flows (Figure 5(c1,c2)) revealed a distinct spatial reorganization: the first subgroup underwent a pronounced displacement toward the northwestern region. Concurrently, the second subgroup exhibited significant expansion, primarily encompassing the central and southwestern areas. In contrast, both the third and fourth subgroups experienced marked spatial contraction, becoming concentrated in the southeastern zone. This spatial reconfiguration indicates a significant intensification of imbalance among the ecological niche subgroups of small-town communities. Consequently, the ecological service functions of towns in the western and central parts of the county were substantially enhanced, while those in the eastern region demonstrated a clear decline.

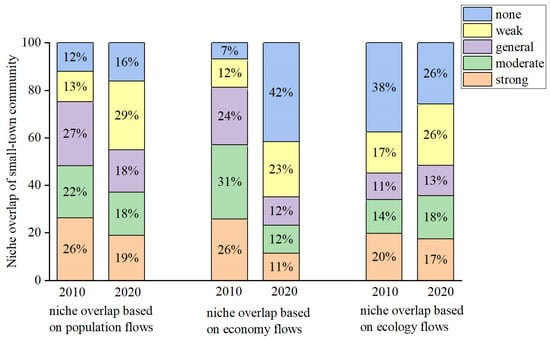

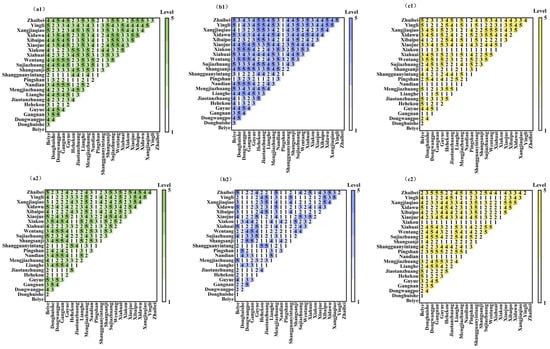

3.4. Evolution of Niche Overlap in Small-Town Communities

The niche overlap among small towns in Pingshan County was quantified and categorized into five distinct levels (Figure 6 and Figure 7), representing, in descending order of intensity: strong competition, moderate competition, general competition, weak competition, and no competition.

Figure 6.

Niche overlap of small-town communities.

Figure 7.

Niche overlap of small-town communites based on different niche factor flows. Niche overlap based on population flows in 2010 (a1) and 2020 (a2). Niche overlap based on economy flows in 2010 (b1) and 2020 (b2). Niche overlap based on ecology flows in 2010 (c1) and 2020 (c2).

From the perspectives of population flow-based and economy flow-based niche overlap, the number of small-town pairs characterized by strong and moderate competition continuously decreased between 2010 and 2020, whereas the number of pairs with weak or no competition increased significantly (Figure 6). Small towns with higher competition levels shifted from spatially dispersed distributions to a concentration in central county areas. In contrast, towns with weaker competition transitioned from clustering in southeastern and northwestern zones to eastern and northwestern regions in terms of population flows (Figure 7(a1,a2)). Regarding economy flows, towns with weaker competition moved from eastern and northwestern regions to southeastern and northwestern areas (Figure 7(b1,b2)). Collectively, the competitive spatial structure of small-town communities evolved from fragmentation toward agglomeration, with significantly intensified competition in central towns.

From the perspective of ecology flow-based niche overlap, the number of small-town pairs with strong competition and no competition decreased from 2010 to 2020, while the number of pairs with moderate and weak competition significantly increased (Figure 6). Specifically, in 2010, towns with stronger competition mainly located in the central and western parts. In contrast, towns with weaker competition were concentrated in the eastern and southwestern regions. By 2020, small towns with stronger and weaker competition with others were also concentrated in the western and eastern regions (Figure 7(c1,c2)). This indicates that the overall competitive intensity within small-town communities is gradually increasing, especially between the eastern towns and others, whereas the competitive dynamics between the western towns and others remained relatively stable.

4. Discussion

Significant disparities were observed across niche dimensions within small-town communities in Pingshan County. Compared to economic, demographic, and social factors, niche indices derived from natural and locational factors exhibited less pronounced variations and limited inter-town variance. This pattern indicates that humanistic drivers primarily govern niche evolution in these communities. Nevertheless, heterogeneity in niche indices persisted even among these humanistic factors. From the perspective of population and society factor, the niche indices changes showed similarities. The niche index advantage of Pingshan Town demonstrated persistent strengthening. While disparities among other small towns diminished, a significant gap with Pingshan Town endured, revealing a polarized development pattern. Notably, economic niche indices exhibited a distinct gradient distribution. This pattern reflects the accelerated economic development observed in specific towns—notably Nandian Town and Xiadawu Town—which substantially narrowed their gap with Pingshan Town. Furthermore, niche subgroups defined by population and economy factor flows displayed significant spatial congruence. These observations point to tightly coupled interconnections among the demographic, economic, and social development of small towns, with an especially robust linkage observed between population and social development. This phenomenon can be largely attributed to the considerable influence of the administrative hierarchy within which these towns are situated. In the Chinese context, the allocation of basic public services—both in terms of quantity and quality—is predominantly determined by a settlement’s administrative rank. Consequently, key commercial and public amenities, including high-tier schools, hospitals, banking institutions, and telecommunications infrastructure, are overwhelmingly concentrated in county seat [46]. Furthermore, driven by the scale effects inherent to economic activities, the spatial distribution of such service facilities demonstrates a strong tendency toward co-location [47]. As a result, settlements endowed with a higher administrative status benefit from significant first-mover advantages, creating a virtuous cycle that attracts further commercial clustering. They also exert a pronounced steering effect on the directional flows of people, capital, goods, and services. This finding is corroborated by Zhang et al., who confirmed that county seat exhibited the most substantial pull on population, commodities, and services within a county’s boundaries [48,49].

The spatial evolution of niche in small-town communities exhibited scale-dependent characteristics. At the macro scale, distinct regional disparities emerged among the eastern, central, and western zones. Small towns in the western region demonstrated significant advantages in natural and ecological dimensions, whereas those in the eastern region excelled in demographic, economic, and social aspects. In contrast, small towns in the central region consistently occupied intermediate positions across most niche dimensions. This observation aligns with previous studies highlighting spatial imbalances and scale-specific variations in the development of small-town communities [50,51,52]. The formation of this spatial pattern stems from the interaction between natural environments and anthropogenic factors. Nevertheless, macro-scale configurations are predominantly governed by natural environmental conditions—such as topography, hydrology, and soil. Given the inherent stability of these environmental factors, the resulting macro-patterns exhibit considerable persistence over time. This principle finds parallel in research on China’s population distribution, where scholars have similarly demonstrated that the long-term stability of macro-scale population patterns is fundamentally constrained by natural environmental frameworks [53].

The spatial pattern of small-town niches, however, demonstrated notable transformations at the micro scale. Within the eastern region, a distinct north–south differentiation emerged, with towns in the south substantially enhancing their comprehensive competitiveness and overtaking those in the north. A similar north–south divergence was apparent in the western region, where southern towns initially exhibited demographic and economic advantages, although these are gradually eroding. By contrast, the ecological competitiveness of northern towns in the west proved markedly stronger. Spatial differentiation in the central region presented greater complexity. The population-related niche competitiveness declined markedly, while the advantage in the ecological environment significantly strengthened. In terms of the economic dimension, the niche displayed both north–south and east–west differentiation. Furthermore, intense competitive interactions were observed among central towns and between them and external towns across population, economic, and ecological dimensions. These towns underwent the most pronounced niche shifts, underscoring their role as the principal drivers of change in the overall niche structure of the small-town communities. Notably, Driven by factors such as a relatively low baseline of economic development, institutional reforms, and flourishing international trade, the period from 2010 to 2020 witnessed accelerated urbanization in China (with an average annual growth rate of 1.39%) accompanied by rapid economic expansion (GDP growing at an average annual rate of 7.3%) [34,35,54]. This phase facilitated swift restructuring among niche subgroups within small towns. In contrast, against the backdrop of moderated economic growth (GDP averaging 5.5% from 2020 to 2024) and weakened population mobility (averaging 0.78% annual growth), the micro-spatial configurations of small towns are expected to evolve only gradually or remain largely stable in the near future [55]. Concurrently, overlap model analysis indicated an overall decline in competitive relationships among small towns, reflecting a dynamic equilibrium shaped by the interplay of their endowment attributes and relational attributes. Accordingly, in formulating regional development policies, local governments could consider adopting the following tailored strategies: prioritizing economic advancement in eastern towns, supporting ecological conservation in western towns, guiding central towns to strengthen their distinctive functions, and fostering multifunctional cluster development. Such a differentiated approach is expected to enhance the efficacy of regional development. Moreover, the implementation of cross-regional compensation mechanisms could help narrow disparities in resident income and social services, thereby promoting greater regional equity.

Additionally, the demographic, social, and economic evolution of small-town communities in Pingshan County exhibited a monocentric pattern anchored on Pingshan Town. This observation diverges from studies documenting a transition from monocentric to polycentric configurations in both plains and mountainous small-town communities [56,57,58]. Such divergence may be due to the fact that small towns are at different stages of development. Crucially, extant research provides no compelling evidence that polycentricity inherently enhances or impedes economic development.

A comprehensive analysis of results derived from multiple niche models revealed a staged evolutionary process within small-town communities. During the initial stage, limited inter-town factor flows resulted in niches being predominantly shaped by local comprehensive endowments, accompanied by generally low levels of niche competition. For instance, in the mountainous western part of Pingshan County—rich in natural and ecological resources—small towns exhibited higher natural niche indices and distinct comparative advantages. By contrast, the eastern plains, characterized by flat terrain and abundant water resources, provided more favorable conditions for socioeconomic development and supported a larger population, leading to significant advantages in humanistic niches. Owing to pronounced endowment disparities between the eastern and western parts of the county, small-town niches demonstrated a gradient distribution pattern with clearly differentiated suitability levels. As regional transportation and economic conditions advanced, factor flows among small towns intensified. Consequently, niche development came to be jointly influenced by local endowments and factor flows. On the one hand, increased factor flows mitigated the constraints imposed by local endowments, intensified niche competition, and reshaped niche index rankings, suitability, subgroup structures, and overlap degrees. On the other hand, these flows enabled complementary advantages among towns, moderated competitive interactions, and reduced suitability disparities within the small-town communities. This transition reflects a shift in the dominant driver of niche evolution—from one primarily governed by local endowments to one increasingly steered by factor flows. Some studies also reveal that the evolution and reconstruction of small towns are significantly influenced by material and immaterial flows [59,60,61]. However, Talandier et al. argues that the territorial capacity of utilizing multi-scale flow systems is a decisive factor in the evolution of small towns in rural areas [62].

Due to limitations in obtaining fine-grained spatiotemporal data for small towns, this study has to rely on proxy indicators to construct the factor flow matrix. Although this method has been widely applied to the studies on urban communities and could deduce the strength or trend of interaction among small towns, it may not fully capture the actual dynamics of inter-town factor flows. Furthermore, since the small-town communities in Pingshan County primarily rely on endogenous development, this paper does not analyze the impact of extra-county flows on these towns. However, with globalization and informatization, local socio-economic activities as well as the flows of materials and energy are increasingly embedded within extensive spatial networks. Tele-connections exert some influence on certain small towns, particularly their connections to urban centers.

For future research, it is necessary to supplement data on small-town enterprise linkage networks (including production and sales networks, technology collaboration networks, and financial network data), resident mobile signaling data, and social survey data. Using this enriched dataset, we will reconstruct the niche factor flow matrix and conduct dynamic studies of small towns. Drawing on flow-based territorial analysis, the research will analyze inflows and outflows of population, economy, material, and energy, along with their interactions, to assess the influence of urban centers on the evolution of small-town communities.

5. Conclusions

Taking Pingshan County in Hebei Province, China, as a case study, this research pioneered the application of four analytical models—the niche state-role model, suitability model, subgroup model, and overlap model—to evaluate the evolution of small-town communities from 2000 to 2020. Our findings revealed distinct evolution patterns and regularities within these suburban settlements. The results demonstrated significant shifts in both the comprehensive niche indices and relative rankings of small-town communities over the study period, although the highest-ranked towns maintained notable stability. Niche indices varied from dimensions, primarily manifesting as a binary opposition between natural and humanistic factors. While the overall suitability of small-town communities showed minimal change, internal disparities gradually narrowed, indicating a trend toward regional equilibrium. The niche subgroups exhibited a clear gradient distribution pattern: ecology functions strengthened markedly in western Pingshan, population and economy functions intensified progressively in southeastern towns, while central-region towns maintained intermediate functional levels. Analysis of niche overlap based on population and economy flows indicated a weakening of overall competitive intensity, though competition among central region towns intensified. Conversely, niche overlap based on ecology flows showed strengthened competitive intensity overall, with particularly pronounced changes observed in central and eastern regions.

The spatial evolution of small-town niches in Pingshan County demonstrated notable scale-dependent variation. At the macro scale, niches exhibited clear regional differentiation—eastern, central, and western—and remained relatively stable in spatial pattern. At the micro scale, however, the spatial configuration of small-town niches underwent considerable reorganization, with the most marked transformations occurring among central region towns. These shifts constituted the primary driver of niche pattern of small-town communities. Furthermore, the niche evolution process followed distinct developmental stages, characterized by a transition in dominant influences from local endowment to factor flows.

Compared with traditional approaches based solely on endowment data, this study integrates both endowment and relational data, providing a new framework and methodology of research on the evolution patterns of small-town communities. It not only elucidates the competitive and cooperative relationships within small-town niches but also delineates the subgroups and their dynamics. This approach significantly advances our understanding of the dynamism and operational mechanisms of small towns, particularly through the lens of interactions between factor scale and factor flow. Methodologically, the proposed framework exhibits reduced reliance on data precision while demonstrating high operationalizability. This makes it especially well-suited for investigating endogenously developing small-town communities, whose evolution is primarily driven by internal resource conditions and factor flows, with minimal external interference. Furthermore, the approach offers a replicable methodological framework for niche evaluation and governance research, applicable to small towns across diverse regional contexts.

Author Contributions

P.X.: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Z.L.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Hebei Provincial Social Science Fund (Project No. HB23SH023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.L.; Li, H.B.; Yuan, Y. Evolution paths and the driving mechanism of the urban-rural scale system at the county level: Taking three counties of Jiangsu province as an example. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 2392–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, J.S. Evolution process and characteristics of multifactor flows in rural areas: A case study of Licheng Village in Hebei, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, E. From central place to network model: Theory and evidence of a paradigm change. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2010, 98, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, P.; Elis, V.; Müller, B.; Yamamoto, K. Peripheralisation of small towns in Germany and Japan—Dealing with economic decline and population loss. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Growe, A. Research on small and medium-sized towns: Framing a new field of inquiry. World 2021, 2, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.H.; Hu, Z.C.; Zhao, Z.F.; Fang, B.X. A review of research on the development of small towns in suburban areas of metropolitans based on the evolution of rural-urban relationship. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2024, 42, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susur, E.; Hidalgo, A.; Chiaroni, D. The emergence of regional industrial ecosystem niches: A conceptual framework and a case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B.; Frey, D.; Moretti, M. The origin of urban communities: From the regional species pool to community assemblages in city. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, F.; Egermann, M.; Betsch, A. The role of niche and regime intermediaries in building partnerships for urban transitions towards sustainability. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guin, D. Contemporary perspectives of small towns in India: A review. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Mitra, A. Shedding light on unnoticed gems in India: A small town’s growth perspective. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.H.; Zhou, L.; Wang, W.; Miao, Y. Spatial relationship between “townizaton” and transportation advantage of small towns in the Yangtze River Delta region. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.X.; Pang, L. The Research Progress and Prospect of Small Town Development and Planning in China since 2000. Urban Rural. Plan. 2022, 1, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dou, Y.Q.; Liu, X.G.; Gong, Z. Multi-hierarchical spatial clustering for characteristic towns in China: An Orange-based framework to integrate GIS and Geodetector. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, X.L.; Tao, J.Y.; Li, H.B.; Zhang, Y.R. An evaluation of the development performance of small county towns and its influencing factors: A case study of small towns in Jiangyin City in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Land 2022, 11, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Q.; Lu, J.Y.; Zhang, M.D.; Niu, F.Q. Evaluation of service function of small towns in China from the perspective of borrowed size and agglomeration shadow: A case study of southern Jiangsu Province. Prog. Geogr. 2022, 41, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartsara, S.I. Definition of a new type of tourism niche-The geriatric tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, L.S.; Yang, P.F.; Ye, J.Q.; Fu, Y.Y. Research on the spatial distribution and influencing factors of small towns under the mountain-sea spatial pattern. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 13, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Q.; Qi, W.; Liu, S.H. Spatial distribution and driving factors of small towns in China. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.H.; Peng, Z.W. Research on the spatial evolution and mechanism of small town agglomeration in metropolitan area: A case study of Fengcheng area in Shanghai. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2019, 5, 8–15. Available online: https://www.shplanning.com.cn/archive/detail/id/772.html (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Meili, R.; Mayer, H. Small and medium-sized towns in Switzerland: Economic heterogeneity, socioeconomic performance and linkages. Erdkunde 2017, 71, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.X.; Liu, B.L.; Yan, Z.Q.; Ma, C.X. Construction and empirical research of an evaluation system for high-quality development of small towns in Guangxi under the new development concept. Land 2024, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, J. Barriers to distribution as regards birds and mammals. Am. Nat. 1914, 48, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qiu, L.; Wang, H.M.; Zhi, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhong, Y.C.; Wang, T. Realizing individual positioning in urban agglomeration under competitive-cooperative networks of niche. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.L.; Wang, R.S.; Tao, Y.; Gao, H. Urban population agglomeration in view of complex ecological niche: A case study on Chinese prefecture cities. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 47, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.G.; Cui, M.R. A new insight to investigate the developmental resilience of Chengdu-Chongqing twin-city economic circle based on ecological niche theory. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 4213–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L. The ‘niche’ city: A multifactor spatial approach to identify local-scale dimensions of urban complexity. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, L.; Soberón, J.; Christen, J.A.; Soto, D. On the problem of modeling a fundamental niche from occurrence data. Ecol. Model. 2019, 397, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, J.; Zhao, Y.J.; Shuai, C.M.; Wang, J.J.; Yi, T.; Cheng, J.H. Assessing the international co-opetition dynamics of rare earth resources between China, USA, Japan and the EU: An ecological niche approach. Resour. Policy 2023, 82, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planka, E.R. Niche overlap and diffuse competition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 2141–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.W.; Xiao, L.S.; Chen, X.J.; He, Z.C.; Guo, Q.H.; Vejre, H. Spatial restructuring and land consolidation of urban-rural settlement in mountainous areas based on ecological niche perspective. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.D.; Huang, A.M.; Yang, D.W.; Lin, J.Y.; Liu, J.H. Niche-driven socio-environmental linkages and regional sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. 2000. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. 2010. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. 2020. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Population Statistical Bulletin. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yang, H.Y.; Zeng, D.; Li, M.M.; Wu, Y.W.; Fan, X.N.; Tong, D. Urban niche in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area from the perspective of multiple space of flows. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 1983–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Tong, Y.; Zou, W. The evolution and a temporal-spatial difference analysis of green development in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Gu, Z.; Li, J. Analysis of the China’s interprovincial innovation connection network based on modified gravity model. Land 2023, 12, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.C.; Zhang, L.Y.; Huang, S.H. Spatial structure and characteristics of tourism economic connections in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 1370–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Feng, X. Urban green space pattern in core cities of the greater bay area based on morphological spatial pattern analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Guo, C.X.; Zhao, M.Y.; Yang, Z.G.; Guo, M.Y.; Wu, B.Y.; Chen, Q.L. Integrating morphological spatial pattern analysis and the minimal cumulative resistance model to optimize urban ecological networks: A case study in Shenzhen City, China. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Tang, Z.Y.; Yu, L.; Guo, C.; Tang, M.X.; Yang, Z.P. Collaborative construction of ecological network in urban agglomerations: A case study of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 8223–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S.; Goldberg, M.; Magdon-Ismail, M.; Mertsalov, K.; Wallace, A. Defining and discovering communities in social networks. In Handbook of Optimization in Complex Networks; Thai, M.T., Pardalos, P.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.A.; Younis, M.S.; Latif, S.; Qadir, J.; Baig, A. Community detection in networks: A multidisciplinary review. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 108, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Operating characteristics of the factor flow networks in rural areas: A case study of a typical industrial town in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.N.; Yu, T.F.; Xie, Y. Characterizing the spatial organization of urban functions using a distance-based colocation quotient approach: With special reference to Beijing. Habitat Int. 2025, 163, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, M.X.; Liang, C. Urbanization of county in China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1241–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.Y.; Qiao, W.F.; Hu, X.L.; Huang, X.J. The evolution modes of town-villages construction pattern of typical counties: A comparative case study of three counties in Jiangsu province. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 2954–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, I.V.; Tulla, A.F.; Zamfir, D.; Petrisor, A.L. Exploring the Urban Strength of Small Towns in Romania. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 152, 843–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónus, G.; Lörincz, L. Rural-urban flows determine internal migration structure across scales. Cites 2025, 163, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.X.; Luo, J.; Kong, X.S.; Sun, J.W.; Gu, J. Characterising the hierarchical structure of urban-rural system at county level using a method based on interconnection analysis. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Peng, R.X.; Zhuo, Y.X.; Cao, G.Z. China’s changing population distribution and influencing factors: Insights from the 2020 census data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán Uriel, J.; Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. Urban Horizons in China: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Intervention in a Country Marked by the Heihe-Tengchong Line. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes; Siew, G., Allam, Z., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Urban Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Shi, Y.W.; Li, X.J.; Zhu, J.G.; Hu, X.Y. Distribution and spatiotemporal evolution of settlement systems in rural industrialized areas: Cases of Changyuan City and Xinxiang County, Henan Province. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.Z.; Jia, K.; Liu, G.J.; Xiong, C.R. Fractal characteristics and influencing factors of market-town system in Xuanwei City of Yunnan. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Li, X.R.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, C.H.; Luo, G.J.; Bai, X.Y. Spatial Structure Integration of Rural Settlements in Karst Mountains Based on Settlement′s Evolution: A Case of Houzhaihe Area. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2016, 36, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, S.S.; Sun, Z.R.; Guo, R.; Zhou, K.; Chen, D.; Wu, J.X. The functional evolution and system equilibrium of urban and rural territories. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1203–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, P.; Mayfield, L.; Tranter, R.; Jones, P.; Errington, A. Small towns as ‘sub-poles’ in English rural development: Investigating rural–urban linkages using sub-regional social accounting matrices. Geoforum 2007, 38, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, B.; Argent, N.; Baum, S.; Bourke, L.; Martin, J.; Mcmanus, P.; Sorensen, A.; Walmsley, J. Local—If Possible: How the Spatial Networking of Economic Relations amongst Farm Enterprises Aids Small Town Survival in Rural Australia. Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talandier, M.; Donsimoni, M. Industrial metabolism and territorial development of the Maurienne Valley (France). Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.