Abstract

Against intensifying climate risks, a paradox persists in green finance: high corporate awareness yet low green bond issuance. This study examines the impact of climate risk on green bond issuance using a final sample of 5958 bond issuances, which were issued by 469 unique A-share non-financial listed companies in China between 2016 and 2023. By integrating the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) into a Motivation–Capability–Triggers framework and employing Logit and Karlson–Holm–Breen (KHB) methods, we investigate the underlying mechanisms. The baseline results show a positive link between climate risk and issuance likelihood, confirming a motivation-incentive effect. Mechanism analyses reveal significant negative mediation through financing constraints, green innovation, and environmental reputation, highlighting a capability-constraint effect. Heterogeneity analysis finds a stronger effect in non-state-owned firms, non-heavily polluting industries, and firms in pilot zones or central/western China, indicating that policy signals and resource endowments act as key triggers to synergize motivation and capability. Our findings offer valuable insights for policymakers in designing motivation-stimulating and capability-compensating intervention strategies to help firms balance economic and environmental objectives.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a pressing global issue. Climate risk, arising from both climate change and the green transition, encompasses physical risk (e.g., asset damage and supply chain disruptions from extreme weather) and transition risk (e.g., policy tightening or technological innovation devaluing high-carbon assets). These risks significantly impact enterprises: physical risk directly threatens operational continuity and asset value, causing substantial losses [1]; transition risk increases compliance costs, weakens market competitiveness, and constrains green innovation and risk resilience [2,3,4,5]. Due to its systemic and complex nature, climate risk has evolved from a peripheral concern to a core corporate strategic issue. The ability to manage these risks has become essential for companies to achieve green growth [6], determining their survival and sustainable competitiveness.

China has integrated sustainable economic growth and high-quality development into its transition strategy, leveraging policies such as the 2016 Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System and the Guidelines on Strengthening Financial Support for Green and Low-Carbon Development to enhance the green financial framework. Green bonds, recognized for their environmental benefits and capital allocation efficiency, serve as key tools for low-carbon transition [7], directing capital toward climate response and corporate green innovation [8]. The market has expanded rapidly since 2016, with annual issuance growing from ¥201.8 billion to ¥683.3 billion by 2024, averaging 16.5% growth, and exceeding ¥800 billion in both 2022 and 2023 (Data source: The "White Paper on Green Bonds in China" released by the China Central Depository & Clearing Corporation (CCDC) in May 2025. https://www.chinabond.com.cn/yjfx/yjfx_zzfx/zzfx_nb/202410/P020250908587041560855.pdf, accessed on 3 November 2025). By end-2024, China’s CBI-aligned bonds reached ¥493.3 billion (Data source: The “China Bond Market Development Report” released by the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors(NAFMII) in May 2025. https://www.nafmii.org.cn/yj/scyjyfx/yjbg/2024yjbg/202505/P020250526543285002511.pdf, accessed on 3 November 2025), ranking third globally and underscoring its role in global green finance.

The academic community widely acknowledges the role of green bonds in promoting corporate sustainable development. Although certification may increase short-term costs, studies confirm that green bonds can ease financing constraints, drive green innovation, improve ESG performance [9,10], and enhance environmental reputation [11], thereby boosting long-term firm value. Paradoxically, despite these demonstrated benefits, corporate willingness to issue green bonds remains low glob-ally. This is starkly evident in China, where green bonds constitute less than 1% of a bond market exceeding RMB 100 trillion (Data source: The “China Bond Market Development Report” released by the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors(NAFMII) in May 2025. https://www.nafmii.org.cn/yj/scyjyfx/yjbg/2024yjbg/202505/P020250526543285002511.pdf, accessed on 3 November 2025). From 2016 to June 2024, only 14% of nearly 800 A-share listed companies that issued credit bonds engaged in green bond financing (Compiled manually based on Wind database), with such issuance representing a mere 3% of the total volume, revealing substantial untapped potential.

Existing research has categorized corporate motivations for issuing green bonds into economic, reputational, and regulatory aspects [12,13,14,15]. However, a critical gap remains: few studies have systematically examined how increasing climate risks influence issuance decisions. Although recent work begins to link climate awareness to issuance [14,16], it fails to resolve the core contradiction: why growing corporate attention to climate risks has not effectively translated into higher green bond issuance. This gap is particularly salient in the context of China’s rapidly evolving green finance market, where the interaction between climate risk, corporate capability, and policy triggers is complex and underexplored. The literature lacks a theoretical framework capable of simultaneously explaining the dual effects of motivational incentive and capacity constraint, especially using data spanning the critical formative period (2016–2023) of China’s green bond market.

To address this research gap, this paper introduces the Fogg Behavior Model to construct an integrated “motivation–ability–trigger” analytical framework [17], aiming to systematically explain the internal mechanisms through which climate risk influences corporate green bond issuance decisions. Based on bond issuance data from Chinese A-share non-financial listed companies from 2016–2023, this study first employs a Logit model to test the net effect of climate risk on the probability of green bond issuance. It then applies the KHB method to thoroughly examine mediating pathways involving financing constraints, green innovation, and ESG performance. Finally, heterogeneity analysis is conducted across dimensions such as corporate ownership, industrial pollution intensity, location in green finance reform pilot zones, and regional resource endowment.

Empirical results validate a “motivation–ability paradox.” Climate risk significantly increases issuance likelihood, confirming a motivation-incentive effect driven by compliance and reputation pressures. However, mediation analysis reveals a simultaneous capability-constraint effect, as climate risk tightens financing, suppresses green R&D, and lowers ESG ratings. Heterogeneity shows the incentive effect is stronger in non-SOEs, less polluting industries, and firms in pilot zones or central/western China, indicating that clear policy signals and resource endowments are key triggers that align motivation with ability.

This study provides a new theoretical perspective on the “high attention, low issuance” paradox by identifying and testing the motivation–capability paradox. It offers a scholarly basis for designing targeted green finance policies that stimulate motivation while compensating for capability constraints, thereby helping firms balance economic and environmental goals.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

As the global climate change agenda transitions from theoretical debate to a substantive economic challenge, the decision-making logic underlying corporate green bond issuance has correspondingly deepened [18,19,20]. This literature review systematically examines two core dimensions: the multifaceted drivers behind issuance decisions and the impact mechanisms of climate risk.

The decision to issue green bonds is shaped by dual motivations arising from internal firm attributes and external institutional-market pressures. Signaling theory explains how firms use green bonds to convey environmental commitments in information-asymmetric markets, enhancing reputation, reducing transaction costs, and aligning with long-term interests [11,21]. Financially, green bonds often carry a “green premium,” featuring lower interest rates than conventional bonds, which makes cost reduction a key economic incentive [22,23]. Firm-specific characteristics such as asset size, profitability, and liquidity further influence financing capacity and method selection, serving as predictors for market entry [24,25,26].

Beyond internal drivers, external pressures significantly influence corporate green financing behavior. To navigate competitive landscapes, secure institutional legitimacy, and fulfill ecological responsibilities, firms proactively adopt green practices to strengthen social endorsement and market positioning [27]. Simultaneously, growing sustainable investment demand motivates firms to issue green bonds to attract environmentally conscious investors, with empirical studies confirming investor preference as a major external driver [28]. Thus, green bond issuance functions not only as a tool for reputation building and financial optimization but also as a strategic response to external expectations—such as policy incentives and investor demand—and a vital mechanism for cultivating competitive advantage.

As the urgency of the climate crisis intensifies, corporate focus is shifting from broad social responsibility to specific and direct climate risks. Physical and transition risks have not only become key variables affecting long-term financial stability but have also transformed climate risk management from a passive compliance exercise into a strategic necessity vital for survival and competitiveness [29,30]. Against this backdrop, the role of green bonds as a financial instrument specifically designed to address climate risks is being re-evaluated by both academics and practitioners.

Compared to other common measures, green bonds offer companies a more structured and strategic response. Research indicates that rising climate risks are encouraging investors to shift capital toward green assets, thereby boosting demand for green investments and providing price stability [31]. Within this trend, green bonds demonstrate unique advantages: they can not only serve as a reliable safe haven during climate uncertainty [32], but also significantly outperform conventional “brown” bonds in the aftermath of climate disasters [33]. Furthermore, investment portfolios that include green bonds can effectively hedge against volatility induced by climate policy uncertainty, an effect particularly pronounced in emerging and developing markets [34]. For corporations, these characteristics make green bonds a comprehensive risk mitigation tool. By issuing green bonds, firms can finance specific projects that enhance their climate resilience—such as infrastructure upgrades and energy transition—thereby converting external risks into internal investment incentives [16,35,36,37]. Managers with strong climate awareness are more inclined to view green bonds as a proactive strategic choice rather than merely a passive financing tool [38].

However, the relationship between climate risk and issuance decisions is not simply one of linear promotion. Studies focusing on climate policy uncertainty reveal another aspect: although green bonds have the potential to mitigate uncertainty and generate positive policy effects [36], frequently changing policy frameworks and geopolitical risks may also suppress the expected benefits of green bonds [39]. This can lead firms to adopt a “wait-and-see” approach, delaying long-term financing commitments. The divergence between theoretical expectations and actual behavior underscores the complexity of the relationship between climate risk and green bond issuance, and suggests the presence of mediating pathways and critical boundary conditions that have not yet been fully uncovered.

Although existing research provides a crucial foundation for understanding the relationship between corporate climate risk and green financing behavior, significant gaps remain. First, most studies focus on testing direct effects, with relatively few investigating the mechanisms transmitting climate risk to financing decisions. Second, there is scarce research examining whether systematic differences exist across firm types and geographical locations. This lack of mechanistic and heterogeneity analysis limits a deeper understanding of the climate risk transmission channel. Therefore, this study adopts a micro-level corporate perspective to investigate the effect of climate risk on green bonds and its internal mechanisms, while also examining the roles played by firm ownership, industry attributes, and regional policies in this relationship.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

To systematically explain how climate risk influences corporate green bond issuance decisions, this study employs the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) as its theoretical framework. This model posits that behavior requires the convergence of three elements: motivation, ability, and triggers [17]. Within this theoretical framework, climate risk influences corporate decision-making through dual pathways. On one hand, increasing climate risk significantly enhances firms’ motivation to issue green bonds through channels such as policy compliance pressure and reputation restoration needs, making them more inclined to use this market-based instrument to address external challenges. On the other hand, climate risk objectively constrains firms’ executive capacity—it not only tightens financing channels and raises funding costs but also crowds out R&D resources, suppresses green innovation capability, and further undermines market credibility by lowering environmental performance. This misalignment between motivation and ability precisely explains the paradox of “high attention but low issuance” observed in current markets.

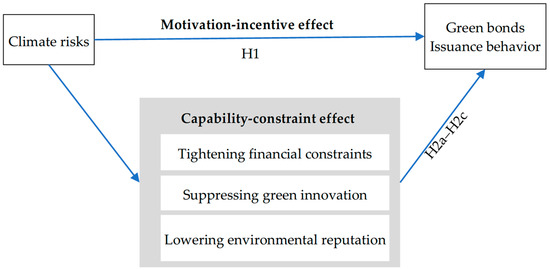

The crucial insight from the Fogg Behavior Model is that green bond issuance decisions can only be realized when firms simultaneously possess sufficient motivation, corresponding ability, and receive effective triggering signals at the right moment. Therefore, our research needs not only to identify the specific pathways of motivational incentives and capacity constraints but also to explore triggering conditions that can effectively align motivation with ability. Establishing this theoretical framework enables us to move beyond traditional single-path analyses and examine the intrinsic mechanisms through which climate risk affects corporate green bond issuance from a systemic perspective. It also provides a theoretical basis for subsequent differentiated policy design tailored to various firm characteristics. We summarize the theoretical analysis and construct a theoretical framework diagram, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework.

2.2.1. Motivation-Incentive Effect

With the rapid development of the global economy and society, the economic losses and systemic challenges brought by extreme climate change are becoming increasingly prominent, and have become a major issue that all countries must address. As core actors in economic activities, enterprises exhibit a high degree of sensitivity to climate risks [40]. At the corporate level, climate risk primarily refers to the possibility of damage that firms face from climate-related disasters, as well as the potential economic losses they may incur under extreme weather conditions. Such risks are long-term and cumulative in nature. They can not only drive-up compliance costs and weaken stakeholder confidence, but also pose a substantive threat to the continuous operation and financial health of enterprises.

In response to intensifying climate risks, firms have a variety of tools at their disposal, including internal capital allocation, conventional bank loans, or other non-public environmental investments. However, green bonds—debt instruments specifically designed to finance or refinance eligible green projects—possess unique signaling and certification effects, setting them apart from other environmental management approaches. Unlike internal funding or ordinary credit, the issuance of green bonds is inherently a public act, typically requires third-party certification, and strictly restricts the use of proceeds to green projects [11]. Such transparency enables firms to send a credible commitment about their green transition to the market and regulators [41], effectively distinguishing them from unverified self-promotion that may be perceived as “greenwashing.” Therefore, when companies face dual pressures from regulation and reputation, green bonds become a strategic choice to clearly demonstrate their determination to take climate action.

Specifically, elevated climate risk strengthens corporate motivation to issue green bonds mainly through two pathways: compliance pressure and reputation restoration needs. In terms of compliance, heightened climate risks are often accompanied by stricter environmental policies and low-carbon transition requirements. This gives firms stronger incentives to adopt verifiable financial instruments like green bonds to demonstrate compliance willingness and avoid regulatory penalties [31]. In terms of reputation, growing stakeholder concern over corporate environmental performance drives companies to use the public signal of green bonds to showcase their commitment to sustainable development. This helps rebuild or strengthen trust with investors and consumers [42], allowing firms to gain a differentiated competitive advantage in an era of climate uncertainty.

Based on the above mechanisms, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Climate risk is positively correlated with the likelihood of green bond issuance.

2.2.2. Capability-Constraint Effect

While climate risk enhances corporate motivation to issue green bonds, the actual execution of such issuance highly depends on the firm’s corresponding capability endowment. Firms facing varying levels of climate risk encounter different practical situations in terms of resource acquisition, technological transformation, and reputation maintenance, leading to differences in their objective capability to issue green bonds. This study identifies financing constraints, green innovation, and corporate ESG performance as the core mediating variables to reveal the potential constraint effects of climate risk on firms’ capability to issue green bonds.

Climate risk exacerbates corporate financing constraints by increasing financing costs and reducing capital availability. Firstly, climate risk significantly raises firms’ external financing costs and limits their access to capital. Physical risks, such as extreme weather events, directly damage the value of corporate collateral and their ability to operate as going concerns, undermining their debt repayment capacity [43]. Transition risks, like sudden policy changes, can strand high-carbon assets, raising investor concerns about the stability of future cash flows [44]. This risk reassessment process leads debt investors to demand higher risk premiums, directly increasing the cost of debt financing for firms.

Secondly, the aggravation of financing constraints directly weakens a firm’s ability to successfully issue green bonds. Although labeled as “green,” green bonds are still a type of debt financing instrument. Their issuance spreads and subscription rates are significantly influenced by the firm’s overall credit profile [11]. When climate risk triggers high-risk premiums for a firm, the actual cost of issuing any bonds, including green bonds, becomes prohibitively expensive, potentially leading to failed issuance. Therefore, even with strong motivation, prohibitively high issuance costs and weak market demand can leave firms willing but unable to proceed.

In summary, by tightening financing constraints, climate risk creates objective financial barriers to corporate green bond issuance. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a.

Financing constraints exert a suppressing mediating effect in the relationship between climate risk and the likelihood of green bond issuance.

A sufficient pipeline of eligible green projects is a prerequisite for the successful issuance of green bonds [45], and a company’s level of green innovation is the key foundation for building this project reserve. However, climate risk may inhibit corporate investment in green innovation, thereby undermining the project foundation necessary for issuing green bonds.

Although some studies suggest that environmental regulation can incentivize green technology innovation and propose that climate risk, by intensifying regulatory pressure, may yield dual benefits of improving environmental performance and creating an “innovation compensation” effect [30,31], its inhibitory effect might be more prominent in the context of high climate uncertainty. On one hand, cash flow volatility and financial distress induced by climate risk can directly crowd out a firm’s R&D funding [46]. On the other hand, faced with significant survival pressure, corporate management’s risk appetite tends to become more conservative, favoring investments that generate quick cash flow. This often leads to the reduction or delay of strategic, long-term, and high-risk investments like green innovation [47].

Insufficient green innovation capability, in turn, directly challenges the core requirements for green bond issuance. The prospectus for a green bond must clearly specify detailed information about the eligible projects and their environmental benefits. If a company lacks substantive green innovation projects to support the issuance, it will face high disclosure costs or even the dilemma of having no eligible projects to fund. This can raise investor concerns about “greenwashing,” severely damaging the bond’s market appeal and the likelihood of a successful issuance [48].

Therefore, by suppressing green innovation, climate risk may erode the very foundation for corporate green bond issuance from its source.

Hypothesis 2b.

Green innovation exerts a suppressing mediating effect in the relationship between climate risk and the likelihood of green bond issuance.

With the growing influence of socially responsible investing and ESG investing, the role of ESG rating agencies has become increasingly prominent [49], making ESG factors a critical element in corporate sustainable operation and capital allocation decisions [50]. A firm’s ESG performance reflects its existing achievements in environmental, social, and governance aspects. A high ESG score helps a company build a green reputation and establish investor trust, thereby stabilizing its external financing channels [10]. High climate risk directly exposes a firm’s vulnerability in environmental management, potentially leading to negative records such as environmental fines or pollution incidents, which can lower its ESG rating [51]. Although firms can engage in active management, climate risk often forces management to divert limited resources from long-term ESG capacity building to addressing short-term operational shocks. This resource crowding-out effect can lead to a decline in the ESG rating.

A decline in ESG performance, in turn, directly undermines investor confidence in subscribing to green bonds. Growing evidence indicates that strong ESG performance can reduce the issuance spread of green bonds [10]. Conversely, if a firm with a low ESG rating, particularly poor environmental performance, attempts to issue a green bond, the market is likely to perceive a misalignment between its actions and its substance, severely questioning its credibility. This decline further weakens investor confidence, damages the firm’s green reputation, and ultimately impairs its ability to issue green bonds.

High climate risk exposes firms to direct operational and financial vulnerabilities. Inadequate responses can significantly lower their ESG scores, especially in the environmental dimension. While proactive measures—such as establishing a robust climate risk management framework, clarifying transition strategies, and improving disclosure quality—can mitigate this decline, climate risk often compels firms to reallocate limited resources to short-term operational survival. This shift crowds out resources originally earmarked for enhancing ESG performance, leading to an overall drop in ESG metrics [51]. Such a decline further erodes investor confidence, harms the corporate green reputation, and ultimately weakens the firm’s capacity to issue green bonds.

Therefore, by impairing ESG performance, climate risk deprives firms of the crucial reputational capital necessary for issuing green bonds. Based on this logic, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2c.

ESG performance exerts a suppressing mediating effect in the relationship between climate risk and the likelihood of green bond issuance.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data

This study selects 2016 as its starting point because China’s green bond market was launched in July 2015 and was subsequently systematized by the “Green Bond Issuance Guidelines” issued by the National Development and Reform Commission on December 31, 2015. The initial sample comprised 9102 bond issuance records from Chinese A-share listed companies spanning 2016 to 2023.

To ensure data quality and research relevance, a systematic screening process was applied:(1) Exclusion of companies listed for less than one year or under Special Treatment (ST/*ST) status to remove the influence of abnormal financial conditions; (2) Removal of financial firms (Industry Code J) due to their distinct business models and financing characteristics;(3) Exclusion of 2084 observations from industries that had no green bond issuance throughout the entire sample period, aiming to focus on market participants actually engaged in green financing and thus more precisely identify the marginal effects of climate risk on issuance decisions;(4) Deletion of records with missing core variable data.

The screening process described above resulted in the exclusion of 3144 observations, yielding a pooled cross-sectional data sample consisting of 5958 observations, which comprised 225 green bonds and 5733 traditional bonds. These bonds were issued by 469 listed companies, accounting for 8.61% of all A-share listed companies. Among these issuers, 96 firms issued at least one green bond during the sample period.

Table 1 presents the industry distribution of green bonds versus traditional bonds in the sample, where “G” represents green bonds and “T” represents traditional bonds. The specific industries corresponding to the industry codes are shown in the Appendix A. From a temporal perspective, the issuance of green bonds increased from 3 in 2016 to 46 in 2023, showing an overall upward trend and indicating gradual market development and acceptance. However, compared to the substantial annual issuance volume of traditional bonds, the scale of green bonds remains relatively small.

Table 1.

Industry Distribution of Green Bond versus Traditional Bond Issuance.

A closer look at the industry distribution reveals a high degree of concentration in green bond issuance. Sector D44 (Production and Supply of Electric Power and Heat Power) stands out as the primary contributor, issuing 92 green bonds, accounting for 40.9% of the total green bonds. This is largely because this sector plays a central role in the energy transition and possesses a substantial number of eligible renewable energy projects. Additionally, sectors such as N77 (Ecological Protection and Environmental Governance) and C38 (Manufacture of Electrical Machinery and Apparatus) also demonstrate a relatively higher propensity to issue green bonds.

However, when comparing it with traditional bond issuance data, we observe a striking contrast in several major traditional bond-issuing sectors. For instance, in sectors such as C26 (Manufacture of Raw Chemical Materials and Chemical Products), C39 (Manufacture of Computers, Communication and Other Electronic Equipment), and K70 (Real Estate), the number of green bonds issued is disproportionately low compared to their traditional bond volumes. As an example, sector K70 issued 1101 traditional bonds but only 11 green bonds. This contrast suggests that although many firms face climate risks and transition pressures—thus having the “motivation” to issue green bonds—their actual “capacity” to do so is constrained by factors such as financing constraints, technological path dependence, or a lack of eligible projects. These constraints ultimately hinder their final issuance decisions.

Overall, the distribution characteristics of the sample indicate that the green bond market is still in its early stages of development. Participation is structurally imbalanced, and penetration remains particularly low in many key transition sectors. This underscores the urgency and importance of theoretically and empirically investigating the underlying constraining factors.

3.2. Variable Definitions

Green bond dummy. Following the approach of Cicchiello et al. (2022) [52], we construct a dummy variable greenbond to capture a firm’s decision to issue green bonds. This variable takes the value of 1 if the bond is a green bond, and 0 otherwise.

Corporate climate risk. Drawing on existing research [5], we measure this using “Management Climate Attention (MCA)”. The construction of this indicator is based on textual analysis of the “Management Discussion and Analysis” section in the annual and semi-annual reports of Chinese A-share listed companies. The specific construction process is as follows: First, 45 core words closely related to climate risk—including air pollution, air quality, carbon dioxide, and carbon emissions—are selected as seed words. Then, the word2vec model is trained using these seed words to build a more comprehensive expanded dictionary. In the text processing stage, Python (version 3.10)’s “jieba” library is used for word segmentation in all sentences, and Chinese stop words are removed. Simultaneously, the “gensim” library helps identify more specific phrases in the documents, and all numbers and punctuation marks are cleared. Based on this, the frequency of words from the expanded dictionary in each document is counted, their relative frequency is calculated, and an adjusted term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) indicator is further constructed. The MCA index [53] synthesized through the above machine learning method effectively captures a firm’s objective recognition, subjective attention level, and strategic response intention towards external climate risks, thereby providing a key analytical basis for understanding corporate behavior in addressing climate challenges.

Mechanism variables. Drawing on the hypotheses and previous studies [19,20,21], this study focuses on three mechanism variables: financing constraints, green innovation, and ESG performance.

This study focuses on three mechanism variables: financing constraints, green innovation, and ESG performance. This study employs both the SA index and the WW index to measure corporate financing constraints. The SA index, proposed by Hadlock and Pierce (2010) [54], is constructed using firm size and age—two relatively exogenous and less manipulable variables. This effectively mitigates endogeneity concerns and is particularly suitable for measuring long-term, structural financing constraints. The WW index, developed by Whited and Wu (2006) [55], is based on the Euler investment equation and incorporates multiple financial dimensions such as cash flow, leverage, and dividend payments, making it more sensitive to short-term fluctuations in financing constraints. Using both indicators allows for a comprehensive assessment of different dimensions and underlying mechanisms of financing constraints, thereby enhancing the robustness of the findings. This approach is consistent with prior research [56].

The WW index is calculated as follows:

where CF represents net cash flow from operating activities divided by total assets; DivPos is a dummy variable that equals 1 if cash dividends were distributed in the current period, and 0 otherwise; Lev denotes the long-term debt-to-assets ratio; Size is the natural logarithm of total assets; ISG refers to the industry’s average sales growth rate, with industry classification following the guidelines from the China Association of Public Companies (using a two-digit code for manufacturing industries and a one-digit code for others); SG represents the firm’s sales growth rate.

The SA index is calculated as follows:

where Size refers to the natural logarithm of total assets; Age represents the firm’s age.

Corporate green innovation is gauged following the research by Amore and Bennedsen [57], using patent data, specifically the number of green invention and utility model patents applied for or granted to the firm. To mitigate skewness due to large cross-firm variation, all patent counts are transformed by adding one and taking the natural logarithm.

ESG performance is assessed using annual ratings published by China Securities Index Co., Ltd., a provider authorized by the Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong stock exchanges. The rating system is constructed top-down, incorporating China’s disclosure context and corporate characteristics. It includes 3 first-level pillar indicators, 16 s-level theme indicators, 44 third-level issue indicators, nearly 80 fourth-level underlying indicators, and over 300 underlying data indicators. By integrating intelligent algorithms such as semantic analysis and natural language processing (NLP), the system leverages a big data platform for ESG. This framework combines international standards with factors specific to the Chinese context.

In the empirical analysis, the green innovation and ESG performance variables are lagged by one period. This serves two purposes. First, it mitigates endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality, as current green bond issuance decisions may influence future innovation and ESG outcomes. The lag ensures the temporal precedence of cause over effect, strengthening causal inference [58]. Second, it aligns with inherent time lags—such as those between R&D investment and patent grants or between the implementation of environmental measures and their reflection in ESG ratings—allowing the model to more accurately capture the mechanisms’ influence.

Control variables. Building on existing research regarding corporate motivations for issuing green bonds, this study selects control variables from two dimensions: bond characteristics and firm characteristics. For bond characteristics, and based on prior studies examining factors that influence corporate green bond issuance [24,59], we control for three variables: bond issuance term, issuance size, and coupon rate.

At the firm level, a firm’s resource endowment significantly influences its strategic choices and constrains its actions [60]. This implies that a firm’s financial condition directly affects its financing capacity, risk tolerance, and long-term strategy, thereby influencing its decision to issue green bonds. Furthermore, ownership structure shapes corporate governance efficiency, strategic orientation, and risk-taking capacity [61,62,63], and is therefore also expected to affect the green bond issuance decision. Accordingly, drawing on the existing literature [24,25], we control for the following firm-level variables: profitability (roa), leverage ratio (leverage), market performance (tobinsQ), and the shareholding percentage of the top ten shareholders (top10). Detailed definitions for all variables are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variables Descriptions.

3.3. Data Sources

This study utilizes data from the following leading sources to ensure comprehensive and reliable coverage. Corporate climate risk is measured by the Management Climate Attention (MCA) index. The MCA data are sourced from the Global Climate Risk Integrated Database (GCRID), jointly maintained by the Carbon Neutrality and Climate Finance Laboratory at the CAS Virtual Economy and Data Science Research Center. Corporate financial data are obtained from the Wind database. Bond-specific characteristics are sourced from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research database (CSMAR). Data on green patents are obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services Platform database (CNRDS). ESG rating data are sourced from Sino-Securities Index Information Service.

3.4. Research Design

3.4.1. Baseline Model

This study employs a logit model, suitable for the binary dependent variable, to examine the incentive effect of climate risk on green bond issuance. The model specification, which builds upon the approach of Zhao et al. (2025) [64], is presented in Equation (3):

Here, ϕ represents the logistic cumulative distribution function, is the intercept, and the core explanatory variable, corporate climate risk, is measured by mca. The model incorporates a set of control variables (), detailed in Table 2, along with dummy variables for the issuer’s industry and the bond’s issuance year; ε denotes the random disturbance term. A statistically significant and positive estimate for would support Hypothesis 1, indicating a net incentive effect of climate risk.

3.4.2. KHB Method

This study utilizes mediation analysis to examine whether climate risk affects green bond issuance through the channels of corporate financial constraint, ESG performance, and green innovation. Given the binary nature of the dependent variable, standard mediation techniques for linear models are susceptible to bias. To address this methodological issue, we adopt the Karlson–Holm–Breen (KHB) method [65,66], which is specifically developed for nonlinear probability models. The KHB method enables an unbiased decomposition of the total effect into direct and indirect components by systematically comparing a full model (that includes the mediator variables) with a reduced model (that excludes them).

Building on the baseline model in Equation (3), the KHB decomposition involves estimating two nested models:

(1) Reduced model. This model excludes the potential mediator variables and is identical to Equation (3). The coefficient β1 for mca in this model captures the total effect.

(2) Full model. This model introduces the hypothesized mediator variable (), as specified in Equation (4):

Here, the coefficient measures the direct effect of mca on green bond issuance, after accounting for the pathway mediated by . The coefficient captures the effect of the mediator itself.

The KHB method quantifies the indirect (mediation) effect of mca through as the difference . Its key advantage is the correction of bias arising from scale heterogeneity between the reduced and full models. Specifically, incorporating a mediator reduces the unexplained variance of the latent outcome variable, resulting in a smaller scale parameter (the standard deviation of the error term) in the full model () than in the reduced model (), i.e., . This scale difference invalidates a direct comparison of coefficients (), as it conflates the true mediation effect with scale-induced bias. The KHB method overcomes this by comparing the scaled coefficients, with the unbiased decomposition being mathematically equivalent to calculating .

The KHB method reports two key estimators: the confusion ratio and the percentage of confusion. The confusion ratio reflects the ratio of the total effect to the direct effect, while the percentage of confusion indicates the proportion of the mediation effect of mediator relative to the total effect. In the empirical analysis, the specific proxy variables for financing constraints, green innovation, and ESG performance (as defined in Table 2) are substituted for the “mediator” term in Equation (4). For brevity, this paper reports only the total effect, direct effect, indirect (mediation) effect, confusion ratio, and percentage of confusion. A negative percentage of confusion implies a negative mediation effect of the selected mediator. All mediation tests are implemented using the KHB command in Stata 16.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables. The dependent variable, greenbond, has a mean of 0.038, indicating that only 3.8% of the bond issuance observations in the sample are classified as green bonds. This low proportion suggests that the green bond market is still in a nascent stage of development and has not yet become a mainstream financing tool for Chinese listed companies.

Table 3.

Summary Statistics.

The corporate climate risk, measured by mca, has a mean value of 0.025 and a standard deviation of 0.021. This indicates significant variation in climate risk among firms. The variable ranges from 0.001 to 0.109, with the maximum value exceeding four times the mean, suggesting that a small subset of companies demonstrate substantially higher climate risk.

The mediation variables exhibit distinct characteristics. Financing constraint indicators show negative means, consistent with theoretical expectations. The SA index demonstrates greater variability and a wider value range, reflecting methodological differences in its construction. Regarding ESG performance indicators, ESG displays moderately high overall levels with limited cross-firm variation, showing relative strength in social and governance dimensions despite notable internal disparities in social performance, while environmental performance shows weaker overall results with significant inter-firm differentiation. Green innovation indicators exhibit low patent averages with high concentration—most firms have minimal output while innovation is dominated by a few firms, demonstrating a characteristic right-skewed distribution.

4.2. Baseline Result

To test Hypothesis 1, we estimate a Logit regression based on Equation (3), with results reported in Table 4. Model 3 serves as the baseline, including only the core explanatory variable without any control variables. As we progressively incorporate bond characteristics, firm-level controls, and dummy variables for both industry and issuance year, the model’s shows a gradual improvement. This suggests that the added variables collectively explain a meaningful portion of the variation in green bond issuance. After including the full set of controls and accounting for industry and year effects using dummy variables, the coefficient on corporate climate risk remains positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. This result indicates that firms exposed to higher climate risk are significantly more likely to issue green bonds, providing support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 4.

The effect of MCA on corporate green bond issuance.

These findings align with risk management, signaling, and compliance motivation perspectives established in the literature. First, the results support the view of scholars such as Huang Et Al. (2018) and Flammer (2021) that firms perceive climate risk as a long-term, substantive financial threat [11,67]. To mitigate this risk and meet compliance requirements, firms are motivated to issue green bonds, thereby raising dedicated funds for green transition, investing in emission-reduction technologies, or building adaptive infrastructure, which reduces their climate vulnerability. Second, as discussed by Flammer (2021), green bond issuance serves as a proactive market signal [11]. It demonstrates a firm’s commitment to managing climate risk and pursuing sustainable development to investors, regulators, and the public, which helps build a green reputation.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Instrumental Variable Regression

A potential bidirectional causality may exist between corporate climate risk and green bond issuance decisions. Stronger climate risk exposure compels firms to undertake substantial green innovation investments [3], which in turn leads to an enhanced propensity to issue green bonds. Conversely, green bond issuance may itself promote the implementation of environmentally friendly projects [11], potentially reducing a firm’s exposure to climate risk. This endogeneity issue could bias the baseline regression results. To address this challenge, an instrumental variable (IV) approach is adopted, following the methodology outlined by [68].

Specifically, drawing on the approaches of Wang Et Al. (2023) and Tian Et Al. (2024) [3,69], the average corporate climate risk (avermca) at the provincial level in the same year is employed as the instrumental variable. This design satisfies the two key conditions for a valid instrument. First, the instrument must be correlated with the endogenous variable. Firms within the same province face highly similar regulatory environments, physical risk exposure, and market competition pressures [3]. Climate risks exhibit a strong common trend through mechanisms such as information spillover and supply chain transmission, thus meeting the relevance condition. Second, the instrument must satisfy the exclusion restriction. The provincial average climate risk is an aggregate macro-level variable, which is expected to influence an individual firm’s green bond issuance decision only indirectly through its impact on the firm’s own climate risk exposure. There is no evidence suggesting that the average climate risk of other firms in the province directly affects a specific firm’s decision to issue green bonds, thereby fulfilling the exclusion restriction.

Table 5 presents the results of the two-stage IV regression. The coefficient of mca in the second-stage regression Column (2) is positive and statistically significant, providing further evidence that climate risk incentivizes firms to issue green bonds.

Table 5.

Robustness checks: addressing endogeneity with instrumental variables (IV).

4.3.2. Sample Alteration

To validate the robustness of the findings, this study conducts robustness checks through sample alteration, with the results reported in Table 6. Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) is applied to the bond sample. As a non-parametric technique, CEM coarsens continuous variables into meaningful intervals prior to matching, thereby minimizing model dependence and improving covariate balance [70]. This approach achieves multivariate balance between green bonds and conventional bonds, effectively reducing the influence of confounding factors in causal inference. Compared to Propensity Score Matching, CEM offers distinct advantages: it avoids functional form assumptions during matching, mitigates the “insufficient overlap in propensity scores” problem, and reduces model dependence bias [71]. These properties make CEM particularly suitable for contexts with substantial distributional differences in bond and firm characteristics.

Table 6.

Robustness checks: alternative samples.

The matching strategy employs multiple covariate sets and methods to ensure robustness. Column (1) uses the full set of control variables, while Column (2) adopts a parsimonious set containing key bond characteristics (term, amount, rate) and fundamental firm financial indicators (roa, leverage, tobinsQ). Columns (3) and (4) further present one-to-one matching results based on the full and core variable sets, respectively. Additionally, we apply Propensity Score Matching (PSM) using control variables as matching characteristics, with kernel matching Column (5) and radius matching Column (6). The estimated coefficients of climate risk remain statistically significant at least at the 10% level across all specifications, consistently supporting our main findings.

To address potential confounding effects from industry heterogeneity, a manual sample reduction approach is implemented. The sample in Column (7) is restricted to industries with more than 10 green bond issuances. Column (8) further narrows the focus to “high-green-intensity” industries, defined as those where green bonds account for over 5% of the total bond issuance within the industry. The sustained statistical significance across these specifications demonstrates that the positive effect of climate risk on green bond issuance robustly withstands changes in sample composition, firmly supporting the hypothesis.

4.3.3. Alternative Model Specifications

Table 7 presents robustness checks using alternative models to assess the reliability of the baseline regression findings. Columns (1) and (2) report estimates from the Probit model without and with industry and year dummy variables, respectively. Columns (3) and (4) present results from the Linear Probability Model (LPM) without and with industry and year dummy variables, allowing a systematic comparison of how model specification affects the coefficient of the core explanatory variable. Timoneda (2021) notes that when the proportion of observations in one category of the dependent variable is less than 25%, an LPM with dummy variables may yield more accurate probability predictions than maximum likelihood methods [72]. However, the inclusion of industry and year dummy variables can introduce estimation bias [58,73,74]. Following Dutordoir Et Al. (2024) [28], we therefore re-estimate the relationship using LPM. Columns (5) and (6) show Relogit regression results without and with industry and year dummy variables, respectively. Since green bonds represent only a small fraction of total bond issuance, traditional logistic regression coefficients may be biased. The Relogit model addresses this by adjusting estimates using prior information about the distribution of rare events in the population, thereby improving the performance of the Logit model in such contexts [75]. Across all model specifications, the core explanatory variable shows a statistically significant positive effect at the 5% level, confirming that the promoting effect of climate risk on corporate green bond issuance remains robust under various estimation approaches.

Table 7.

Robustness Checks: alternative models.

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.4.1. Financing Constraints

To comprehensively capture the mediating role of financing constraints in the relationship between climate risk and green bond issuance, this study adopts complementary measurements using both the SA index and the WW index [54,55]. This dual-measurement strategy jointly characterizes the potential inhibitory effect of financing constraints from two dimensions: long-term structural and short-term dynamic perspectives.

The mediation test results, presented in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8, show statistically significant negative mediating effects at the 1% level for both the SA and WW indices. For the SA index, the total effect of climate risk is 14.578, the direct effect is 17.039, and the indirect effect is −2.46 (representing −16.88% of the total effect). For the WW index, the indirect effect accounts for −16.05% of the total effect. These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 2a, confirming the presence of a suppressive mediating role of financing constraints in this relationship.

Table 8.

Mechanism analysis: financing constraints and green innovation.

The findings indicate that the dominant direct positive effect of climate risk on green bond issuance is partially offset by a suppressive mechanism through financing constraints. Rising climate risk exacerbates firms’ financing constraints as investors and creditors perceive it as a signal of financial vulnerability, leading to credit rationing or higher risk premium demands [44], thereby increasing financing costs. Since green bond issuance typically requires ample financial resources and stable market confidence [76], heightened financing constraints inhibit both the willingness and ability of firms to issue green bonds. This validates the theoretical mechanism that climate risk not only directly incentivizes green bond issuance but also generates a significant suppressive effect by exacerbating financing difficulties.

4.4.2. Green Innovation

To examine the mediating role of green innovation, this study employs the granted and application numbers of green invention patents and green utility model patents to measure corporate green innovation capability from different perspectives. These indicators effectively distinguish between innovation types and stages, allowing for a precise capture of in-house green R&D outcomes. The mediation test results in Columns (3) to (6) of Table 8 show statistically significant negative mediating effects at the 10% level for all variables, confirming green innovation as a critical transmission channel. Specifically, the indirect effects account for −15.71% (G_invent), −9.10% (G_utility), −14.06% (A_invent), and −6.19% (A_utility) of the total effects, with invention patents exhibiting stronger suppression than utility model patents. All indicators demonstrate a consistent suppressive mediation pattern, supporting Hypothesis 2b.

Although climate risk generally promotes green bond issuance overall, this relationship is mediated through the green innovation mechanism. According to risk management theory, firms prioritize strategies with greater certainty when expected values are comparable [77]. Green innovation requires long-term resource commitment without immediate returns, leading to reduced investment under climate uncertainty [47], thereby lowering green innovation activity, particularly deep-level green innovation. As green bond issuance relies on credible innovative projects, diminished innovation capacity may raise investor skepticism regarding corporate environmental commitment, ultimately undermining the ability to issue green bonds.

4.4.3. ESG Performance

This study examines the mediating role of corporate ESG performance by conducting separate tests on the overall ESG score and its individual dimensions (Escore, Sscore and Gscore). The KHB estimation results in Table 9 show a statistically significant negative mediating effect for the overall ESG score at the 5% level, with an indirect effect of −1.938, accounting for −11.22% of the total effect, thus supporting Hypothesis 2c. Dimension-specific tests reveal a significant effect only for the social dimension (Sscore), while the environmental (Escore) and governance (Gscore) dimensions show insignificant indirect effects.

Table 9.

Mechanism analysis: ESG performance.

These findings indicate that corporate ESG performance exerts a suppressive mediating effect in the climate risk-green bond issuance relationship. Although firms with advanced environmental management typically enjoy debt financing advantages [78], and strong ESG performers are more likely to issue green bonds [79], high climate risk undermines corporate ESG performance [51]. This degradation weakens firms’ credibility and attractiveness in the green bond market, as investors prefer companies with sound environmental records [80]. Consequently, by degrading ESG performance, climate risk invites investor skepticism regarding sustainability commitments, thereby undermining the attractiveness and likelihood of green bond issuance.

The significant mediating role of Sscore, compared to the non-significance of Escore and Gscore, can be explained by their distinct transmission mechanisms. Climate risk directly impairs operational continuity, supply chain stability, and occupational safety—core components of social performance—making Sscore a highly sensitive channel that rapidly undermines stakeholder trust. In contrast, environmental performance (Escore) is itself a primary target of climate risk, resulting in potential collinearity that masks its independent mediating effect. Governance performance (Gscore), being influenced by numerous factors beyond climate risk, plays a weaker role in this specific pathway.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Ownership Nature

Given the diverse ownership structures of Chinese enterprises, with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) playing a pivotal role in the national economy [5], this study examines the relationship between climate risk and green bond issuance across ownership types. Using ownership nature data from the CSMAR database, firms are categorized into SOEs and non-SOEs for separate regression analysis. The results in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 10 show statistically significant coefficients at the 1% level. The regression reveals a higher coefficient of climate risk’s impact on green bond issuance for non-SOEs (68.497) relative to their state-owned counterparts (43.037).

Table 10.

Heterogeneity Analysis.

This indicates that non-SOEs exhibit greater responsiveness to climate risk and a stronger motivation to utilize green bond financing. The disparity can be attributed to external triggers: non-SOEs face stricter market supervision and greater environmental compliance pressure. Climate risk intensifies scrutiny from investors and consumers regarding corporate environmental behavior, leading non-SOEs to issue green bonds as a signal of environmental commitment, to alleviate legitimacy pressures, and to maintain market competitiveness. In contrast, SOEs benefit from inherent institutional ties with the government, often gaining access to more green investment support when adapting to regulatory changes [81]. When confronted with climate risk-induced operational difficulties and default risks, implicit government backing through subsidies and credit guarantees significantly mitigates investor concerns about debt default in SOEs [82]. Consequently, SOEs demonstrate a relatively weaker motivation to issue green bonds specifically in response to such external pressures.

4.5.2. Industrial Pollution Characteristics

To examine heterogeneity in the relationship between climate risk and corporate green behavior across industries with varying pollution intensities, a subsample analysis is conducted by classifying firms based on their status as heavily polluting industries. The classification criterion follows the Industry Classification Management List for Environmental Verification of Listed Companies and the Guidelines for the Industry Classification of Listed Companies (revised in 2012). Using industry classification data from the CSMAR database, sample firms are divided into heavily polluting and non-heavily polluting groups for separate regression analysis (The Industry Classification Management List for Environmental Verification of Listed Companies issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China, and the Guidelines for the Industry Classification of Listed Companies (2012 Revision) issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission. The designated industry codes for heavily polluting firms mainly include B06, B07, B08, B09, C17, C19, C22, C25, C26, C28, C29, C30, C31, C32 and D44).

The regression results presented in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 10 indicate a higher coefficient for mca on green bond issuance within the non-heavily polluting industry group compared to its heavily polluting counterpart. Non-heavily polluting firms exhibit a stronger green behavioral response to climate risk. Since these firms typically fall outside the core scope of stringent environmental regulations, climate risk acts as a salient external pressure, compelling them to adopt proactive green practices. Such practices help secure legitimacy, address stakeholder preferences, and enhance ecological competitiveness [27]. The marginal reputational benefits and potential market returns derived from these actions are particularly significant for this group, thereby strengthening their motivation to issue green bonds. Conversely, heavily polluting firms operate under existing stringent environmental regulations, where green behaviors are often driven by compliance as a defensive strategy. Coupled with high transition costs, significant asset specificity, and the substantial financial outlays required for fundamental process transformation, these constraints severely limit their capacity to issue green bonds, resulting in a lagged response despite facing potentially stronger external pressures.

4.5.3. Green Finance Policy

As a national institutional arrangement, green finance policy significantly guides corporate environmental behavior and financing decisions. Firms located within policy implementation zones benefit from clearer guidance and stronger financial subsidies, prompting more proactive pursuit of green development goals [83]. Since 2017, the State Council has established multiple Green Finance Reform Pilot Zones to explore replicable institutional innovations through regional trials. Based on this policy context and following the approach of [84], the sample is divided into pilot and non-pilot zone groups according to the firm’s registration location and policy timeline for subsample regression analysis.

Results in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 10 show a coefficient of 39.959 for the non-pilot zone group, compared to 123.527 for the pilot zone group, indicating a significantly stronger promoting effect of corporate climate risk on green bond issuance within pilot zones. This suggests that the pilot zones, as a critical institutional supply, reduce transaction costs and uncertainties associated with green bond issuance by providing clear policy guidance, unified project certification standards, and supporting incentives [85]. Consequently, firms facing climate risk can more readily translate risk perception into substantive financing actions. The findings highlight that the institutional environment is a key factor determining market efficiency in responding to climate risk. Therefore, advancing green finance requires not only market-based risk pricing mechanisms but also streamlined policy transmission channels through optimized institutional design to incentivize corporate green transition.

4.5.4. Regional Disparities

Significant disparities in regional economic development levels across China may influence corporate behavioral responses to climate risk. To examine these differential impacts, firms are categorized into Eastern, Central, and Western regional subsamples based on their registered provinces, following the approach of Zhao Et Al. (2023) [86], for separate regression analyses.

Results in Columns (7) to (9) of Table 10 indicate that firms in the Eastern region exhibit significantly lower responsiveness to climate risk compared to those in the Central and Western regions. This divergence can be attributed to the Eastern region’s mature market economy and developed environmental regulatory framework, where firms typically possess established environmental management and risk response mechanisms, requiring only marginal adjustments within existing systems when facing new climate risks. In contrast, the Central and Western regions, characterized by relatively lagging economic development and evolving institutional environments, impose weaker environmental constraints on firms. Consequently, firms in these areas necessitate more substantial behavioral adaptations to address emerging climate pressures, manifesting as higher response intensities. These findings align with the institutional economics perspective that the maturity of the institutional environment significantly shapes how market actors respond to external shocks [87]. It also indicates the need for differentiated policy guidance tailored to regional institutional development levels during the green transition.

4.6. Further Analysis

To thoroughly examine the impact of corporate climate risk on the intensity of green bond issuance, this study constructs a regression model based on a balanced panel dataset of A-share listed firms from 2016 to 2023. Firms that never issued any bonds during the sample period are excluded. The core dependent variable, green bond issuance intensity, is measured through three dimensions: the absolute number of green bonds issued annually (bond_count), the ratio of the number of green bonds to total bonds issued (issuance_ratio), and the proportion of green bond financing amount in total bond financing (proceeds_ratio). These metrics capture the frequency, structural preference, and capital allocation intensity of green financing, respectively. The econometric model specified in Equation (5) is employed for analysis, where the dependent variable is issuance intensity (intensity) measured by the three indicators, the core explanatory variable is corporate climate risk (mca), and control variables are included to mitigate omitted variable bias. Industry and year fixed effects account for unobserved heterogeneity and macroeconomic shocks.

The selection of control variables comprehensively considers factors influencing green bond issuance, covering basic firm characteristics, financial conditions, and governance structure. Basic firm characteristics control for the number of employees (employees) and firm age since listing (age), accounting for developmental stage and resource endowment. Financial conditions include price-to-earnings ratio (PE), Tobin’s Q (tobinsQ), current ratio (current), leverage ratio (leverage), and return on total assets (roa) to capture profitability, market valuation, liquidity, and capital structure. Governance structure is controlled Via board size (board) and the shareholding ratio of the top five shareholders (top5), measuring corporate governance strength and ownership concentration. Ownership nature (soe) is also included to account for systematic differences between SOEs and non-SOEs in environmental objectives and financing constraints, facilitating a clearer identification of the net effect of climate risk on green bond issuance intensity.

To ensure the reliability of subsequent regression results, this study begins by conducting stationarity tests on the panel data. Following the method of Shobande and Asongu (2022) [88], we employ the LLC and Fisher-type panel unit root tests for all continuous variables. Variables with deterministic trends, such as state-ownership and firm age, as well as the board size variable which exhibited minimal variation during the observation period, are excluded from testing. Initial unit root tests on the three green bond issuance dependent variables indicated non-stationary series, which aligns with the expectation that such variables are often subject to structural breaks caused by macro-policy shifts [89]. Accordingly, we introduce a structural break in the year 2020, coinciding with the release of the pivotal Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue (2020 Edition). The subsequent tests controlling for this break show that all three dependent variables reject the null hypothesis of a unit root at the 1% significance level (p-values < 0.01), confirming their stationarity (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Unit Root Test.

To capture the structural change induced by the 2020 Green Bond Catalogue and its impact on the core transmission mechanism, we extend the baseline model. Following related literature, a time dummy variable (post) is constructed, equaling 1 for 2020 onward and 0 otherwise. To test if the policy altered the pathway from corporate climate risk (mca) to issuance behavior, we introduce the interaction term post × mca. This allows the coefficient of mca to vary by policy period, distinguishing its differential impact before and after the regulatory shift. Results are shown in columns (4) to (6) of Table 12, where the interaction term’s significance reveals the policy’s moderating effect.

Table 12.

Further Analysis: The Impact of Climate Risk on Green Bond Issuance Intensity.

Columns (1)–(3) show that mca is positively and significantly associated with all three measures of green bond issuance at the 1% level. A one-unit increase in mca corresponds to an increase of about 2.182 in issuance count, 90.304 percentage points in the issuance ratio, and 103.256 percentage points in the proceeds ratio. When the policy dummy is added Columns (4)–(6), post × mca is significantly positive throughout. Meanwhile, the significance of mca diminishes, especially for the ratio-based measures. This pattern does not indicate a weaker role for climate risk. Instead, it suggests the policy’s pivotal function was to activate and clarify the previously ambiguous link between climate risk and green financing choices. By establishing unified standards, the policy enabled markets to price climate risk more effectively and gave firms a clearer basis to align financing decisions with risk management.

The findings reaffirm that climate risk incentivizes green bond issuance and provide deeper insights into corporate financial responses to climate change. Firms facing elevated climate risk not only increase the quantity of green bond issuances but also undergo a fundamental transformation in their financing structures. This elevated issuance intensity reflects a strategic reallocation of capital to hedge against climate risk and signal commitment to sustainable development, aligning with research indicating that markets reward firms adopting forward-looking environmental strategies [90]. The results also support the view that climate policy pressures motivate firms to actively utilize the green bond market [91]. Thus, the climate risk-driven increase in issuance intensity represents a strategic capital restructuring aimed at building long-term competitiveness in the transition to a low-carbon economy.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Based on data from Chinese A-share listed companies from 2016 to 2024, this study empirically examines how climate risk influences corporate green bond issuance decisions. The main findings are threefold. First, climate risk exerts a significant motivation-incentive effect, as firms facing higher climate risk show a statistically significant increase in green bond issuance probability. This robust result aligns with the Porter Hypothesis [92], indicating that policy compliance pressure and reputation repair needs motivate issuance, consistent with Guesmi Et Al. (2025) and Luo and Lyu (2025) [20,93]. Second, mechanism analysis reveals a parallel capability-constraint effect, whereby climate risk undermines issuance capability through intensified financing constraints, suppressed green innovation, and lowered ESG performance [44,47,51], highlighting the complex interplay of motivational and capability constraints. Third, heterogeneity analysis shows the weaker incentive effect of climate risk in SOEs, heavily polluting industries, firms in non-pilot zones, and companies in eastern China. This pattern is attributable to inherent financing advantages [81], higher transition cost, or a lack of targeted policy support. Overall, these findings emphasize that climate risk does not influence corporate green bond issuance in a simple linear manner, but operates through dual pathways of motivation and constraint. The institutional context—integrating ownership structure, industry characteristics, and external policy environment—acts as a key triggering mechanism that moderates how climate risk translates into corporate action [84].

Informed by the Fogg Behavior Model, this study proposes an integrated policy framework to enhance the net incentive effect of climate risk through synergistic motivation-incentive, capacity-compensation, and targeted trigger approaches. This framework strengthens firms’ internal motivation and external capability, transforming climate risk from an external challenge into a decisive driver of corporate green finance behavior and China’s dual carbon goals. It consists of three core components:

First, regarding motivational incentives, policy design should shift the driving force for green bond issuance from external compliance pressure to cultivating intrinsic reputational capital and long-term competitive advantages. Policies should aim to create market-based incentive mechanisms that enable outstanding ESG performance to directly enhance corporate financial performance. Policymakers must move beyond traditional instruments and effectively leverage market forces. For instance, when promoting frameworks such as TCFD, the objective should extend beyond mere disclosure compliance to actively fostering a “green premium” effect. This would allow companies with high-quality disclosures and excellent green performance to gain tangible benefits such as lower financing costs and higher market valuation, thereby encouraging a transition from passive compliance to proactive initiatives [94]. Simultaneously, regulatory agencies should be encouraged to facilitate lower issuance interest rates for enterprises demonstrating continuous improvement in their ESG ratings, thus directly transforming environmental performance into financing advantages. Alternatively, measures such as prioritizing government green procurement or providing targeted tax incentives [95] could be implemented, enabling ESG-leading companies to secure more orders and profits in their core business operations, thereby forming a virtuous cycle where ESG improvement and revenue growth reinforce each other.

Second, in terms of capacity compensation, targeted policies should be implemented to address key capacity constraint pathways—namely financing constraints, innovation bottlenecks, and ESG performance challenges. To alleviate financing constraints, support such as interest subsidies and credit guarantees should be directed to enterprises with genuine transition willingness and capacity [96], coupled with reasonable carbon tax policies, while linking support levels to the feasibility of transition plans. To tackle weak innovation links, governments should build innovation ecosystems by establishing R&D centers, providing tax incentives [97], or setting up Public–Private partnership platforms [98], thereby reducing corporate innovation costs. To address declining ESG performance, rating agencies should be encouraged to develop dynamic assessment methodologies that promptly translate corporate green efforts into rating improvements [99]. To ensure the effective operation of ESG value realization mechanisms, climate objectives must be embedded into corporate decision-making systems through governance structure reforms. Regulatory authorities should issue relevant policy guidelines encouraging listed companies to incorporate key environmental indicators—such as carbon reduction target completion rates and green bond fund utilization efficiency—into executive performance evaluations and compensation systems [100], thereby aligning long-term green strategies with short-term management interests. Simultaneously, listed companies should be guided to establish sustainability committees led by independent directors at the board level, clarifying their oversight responsibilities for climate risk management and green investment decisions [99], thus structurally ensuring that green financial instruments serve substantive transition.

Third, heterogeneity analysis indicates that the incentive effect of climate risk is weaker in state-owned enterprises, highly polluting industries, non-pilot zone firms, and enterprises in eastern regions. This pattern can be attributed to their inherent financing advantages, higher transition costs, or lack of targeted policy support. Overall, these findings emphasize that the institutional context—integrating ownership structure, industry characteristics, and external policy environment—acts as a key triggering mechanism that moderates how climate risk translates into corporate action. Therefore, we recommend that in terms of targeted triggering, a differentiated policy transmission mechanism based on heterogeneity should be constructed. For state-owned enterprises with insufficient motivation due to financing advantages, regulatory mandates such as incorporating green performance into assessment requirements [100] can convert potential benefits like reputational capital into immediate incentives. For heavily polluting industries facing high transition costs and capacity limitations, guidance-based support—such as providing clear green credit standards and transition pathways [101]—can reduce technological barriers, while strengthening the implementation of green credit policies through unified and operational rules, establishing sound credit industry constraints and incentive mechanisms, and clarifying the legal responsibilities of borrowing enterprises, banks, and financial institutions. For enterprises in regions with weak policy support, governments should act as builders of innovation ecosystems—for instance, allocating fiscal resources to support the establishment of innovation centers and offering tax incentives to firms investing in green technologies [97]. Establishing Public–Private partnership (PPP) platforms for green technology pilot testing [98], supported by quantified ecological compensation [102] and transparency mechanisms, can enhance actionable policy signals and guide green investment through the policy environment [86]. By precisely matching triggering mechanisms with group characteristics, synergy between motivation and capacity can be achieved.

The main contributions of this study are threefold. First, it innovatively introduces the Fogg Behavior Model to construct an integrated “Motivation–Ability–Trigger” framework, revealing the dual impact of climate risk on corporate green bond issuance: while creating motivational incentives through policy and reputational pressures, it simultaneously imposes capacity constraints by exacerbating financing difficulties, suppressing green innovation, and lowering environmental performance. This framework extends behavioral theory from the individual to the corporate financial decision-making level, clarifying the decision-making dilemma caused by the mismatch between motivation and ability observed in prior research.

Second, using KHB mediation analysis, the study precisely identifies three key capacity-constraining pathways: climate risk not only increases financing costs and crowds out R&D resources—thereby weakening project pipelines—but also creates new compliance barriers by triggering ESG rating downgrades and raising “greenwashing” concerns. These findings provide mechanistic evidence explaining the global paradox of “high climate awareness but low green bond issuance.”