1. Introduction

Universities play a central role in national and regional innovation ecosystems. Their scientific and technological innovation efficiency (STI) is increasingly important for regional high-quality development [

1]. This is especially true for architecture-related disciplines. Universities do more than create knowledge. They also support technology transfer and commercialization. In addition, they cultivate talent. Together, these functions help drive industrial upgrading, urban sustainability, and green transformation. Therefore, the ability of universities to convert research inputs into useful outputs can shape regional development trajectories [

2].

However, several challenges remain. Large disparities in economic foundations, resource endowments, and policy environments lead to substantial cross-provincial differences in STI. Many evaluation approaches still emphasize output volumes. They often ignore the full input–output–efficiency process, which can obscure true innovation performance. Architecture-related innovations are receiving increasing attention. Examples include sustainable construction, digital building technologies, and urban renewal. However, empirical evidence remains limited. In particular, few studies systematically examine how STI in these fields contributes to regional high-quality development [

3,

4].

With global competition in innovation intensifying, universities have assumed a more prominent position within national innovation systems. Their STI has therefore attracted sustained attention from both academic researchers and policymakers. Beyond knowledge transmission, creation, and diffusion, universities function as key engines of regional industrial upgrading and high-quality development. Existing research on university STI has developed along two main lines. One strand focuses on efficiency comparisons across different types of universities. The other examines cross-regional disparities in innovation efficiency. Regarding institutional differences, scholars have adopted a variety of analytical approaches to evaluate STI across university categories. Liu et al. [

5] propose a two-stage framework of “knowledge creation” and “knowledge transformation.” Using a shared-input DEA model, they measure industry–university–research collaborative innovation efficiency in China and identify clear regional contrasts. Gong et al. [

6], based on panel data for universities from 2009 to 2018, distinguish between outbound and inbound open innovation. Their results show that outbound openness significantly improves university innovation efficiency. For inbound openness, collaboration with domestic universities and foreign institutions is associated with higher efficiency in invention patents and scholarly publications, respectively. These relationships are further strengthened by absorptive capacity. Using a difference-in-differences design, Jiang et al. [

7] analyze panel data from 62 universities between 2009 and 2016 to evaluate China’s 2013 reform of the science-and-technology evaluation system, which emphasized “quality, efficiency, and contribution”. The reform increased both the output and quality of basic research but reduced applied research outputs. The effects were more pronounced in better-resourced pilot universities and operated mainly through human-capital incentives, higher R&D intensity, and industrialization-oriented project allocation. The reform also contributed to improved technology transfer.

Building on this strand of research, a growing body of literature documents pronounced regional disparities in university innovation efficiency. Using panel data from China’s coastal provinces and cities between 2005 and 2017, Wang et al. [

8] apply spatial econometric methods to examine these differences. Their results show that universities’ technological innovation capability generates significant positive spatial spillover effects, which are even stronger than the direct effects. In contrast, fixed asset investment, urbanization, and government size mainly exert direct influences, while trade openness produces both direct and spillover effects.

Focusing on a more localized context, Yang et al. [

9] analyze 34 universities in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and construct networks of patent application and transformation. They identify strong spatial spillovers in patenting activities. Government funding and local economic prosperity do not show significant positive effects, whereas moderate institutional distance is associated with higher patent output. The study further reveals two key channels of patent transformation: the strategic reallocation of internal resources and close collaboration with the surrounding regional innovation ecosystem.

Meanwhile, research on regional high-quality development has expanded rapidly. Many studies emphasize that disparities in economic foundations, industrial structures, and factor endowments are major sources of uneven development across regions. To capture these differences, scholars have developed multidimensional indicator systems and examined development mechanisms from perspectives such as factor allocation efficiency, industrial competitiveness, and spatial spillovers [

10]. Spatial econometric evidence further suggests that high-quality development exhibits clear spatial effects. It not only promotes economic growth directly but also generates spillover effects that help reduce interregional development gaps [

11].

Research on university STI has developed along two main strands. The first strand focuses on institutional differences and efficiency measurement. Many studies employ methods such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA), and multi-stage input–output models to compare innovation performance across universities or regions [

12]. This line of research focuses on knowledge-creation efficiency and knowledge-transformation efficiency. It also examines the role of open innovation and the impact of science-and-technology policy reforms on university outcomes. Overall, these studies suggest that STI performance is strongly shaped by resource endowments, governance structures, and innovation models [

13,

14].

The second strand highlights spatial heterogeneity and regional development dynamics. Empirical evidence shows that STI exhibits pronounced spatial disparities and generates spillover effects through collaboration networks, patent transfer, and regional innovation systems [

15]. Research on regional high-quality development reports similar patterns. Development levels vary substantially across regions due to differences in industrial structure, ecological constraints, economic foundations, and digitalization capacity [

16]. To capture these disparities, scholars commonly construct multidimensional indicator systems covering labor quality, industrial upgrading, ecological governance, and digital infrastructure. Spatial econometric analyses further indicate that high-quality development produces spillover effects that help reduce interregional gaps over time [

17].

Despite these contributions, several limitations remain. First, many studies rely on output-based or single-dimensional indicators, which do not fully capture the efficiency dimension of university innovation activities [

18]. Second, regional heterogeneity is often discussed descriptively, with limited use of rigorous empirical identification strategies [

19]. Third, relatively few studies examine how STI—especially in architecture-related disciplines—functions as a mechanism shaping regional high-quality development [

20].

More fundamentally, existing research tends to combine efficiency measurement and regression analysis in a largely descriptive manner. Innovation efficiency is often treated as a static performance indicator, and its effects are assessed only after the fact. This approach implicitly assumes that efficiency gains translate uniformly into development outcomes across regions. It pays limited attention to how efficiency operates as an active transmission mechanism that links university innovation activities to regionally differentiated economic, industrial, and ecological development processes. As a result, the pathways through which efficiency improvements are converted into tangible regional impacts remain insufficiently explored.

This study addresses this gap by explicitly reframing scientific and technological innovation efficiency as a transmission process that is both discipline-embedded and regionally mediated. Rather than treating efficiency as a standalone outcome, this study conceptualizes it as a transmission mechanism. Specifically, efficiency links research inputs to development-relevant outputs under heterogeneous regional and disciplinary conditions. By doing so, the study moves beyond the conventional paradigm of method combination and offers a process-oriented perspective on how and why university innovation efficiency contributes to regional high-quality development.

From a theoretical perspective, this study also contributes to the expansion of regional innovation theory into the interdisciplinary field of architecture-related disciplines. Traditional regional innovation frameworks are mainly developed for manufacturing sectors and high-technology industries. They also often focus on generalized university innovation systems. These frameworks typically assume that innovation diffuses through relatively standardized industrial channels. Architecture-related disciplines differ fundamentally from this assumption. Innovation in these fields is strongly project-based. It is also deeply embedded in specific local contexts. Moreover, architecture-related innovation is subject to intensive institutional, regulatory, and planning constraints. These characteristics shape how innovation is generated, transmitted, and absorbed at the regional level. As a result, the pathways through which architectural innovation affects regional development differ from those observed in manufacturing- or laboratory-based disciplines.

By focusing on architecture-related disciplines, this study extends regional innovation theory in two important directions. First, the analysis shifts the focus away from abstract innovation outputs. Instead, it emphasizes engineering-oriented innovation processes. These processes are directly embedded in regional production systems, urban space, and infrastructure development. Second, the study highlights the importance of discipline-specific characteristics in shaping innovation efficiency. The regional impact of university innovation is therefore not discipline-neutral. It depends on how closely academic knowledge is connected to local industrial structures, construction activities, and governance contexts.

In doing so, this study advances a more differentiated understanding of regional innovation systems. Universities are viewed not only as generic producers of knowledge, but also as discipline-embedded innovation actors. Their innovation efficiency and development effects vary systematically across academic fields. This theoretical extension helps bridge regional innovation theory with studies in architecture and engineering. It provides a more nuanced explanation of how innovation efficiency is translated into regional development outcomes. In particular, it clarifies why efficiency gains in applied, engineering-oriented disciplines are more likely to generate observable improvements in regional high-quality development.

Architecture-related disciplines are singled out in this study for two main reasons. First, they are inherently engineering-oriented and strongly applied. Second, they are closely aligned with key dimensions of regional high-quality development. Unlike many basic or purely theoretical disciplines, architecture and engineering research is directly embedded in regional production systems. This embedding occurs through construction activities, infrastructure investment, urban renewal, and environmental governance. As a result, innovation outputs in these fields—such as green building technologies, digital construction methods, and sustainable infrastructure solutions—can be translated more rapidly into tangible regional outcomes. These outcomes include industrial upgrading, energy efficiency improvement, and ecological performance enhancement. Consequently, improvements in innovation efficiency within architecture-related disciplines are more likely to generate immediate and observable effects on regional development than efficiency gains in disciplines with weaker local industrial linkages.

To address these issues, this study develops a unified analytical framework that links STI efficiency to regional high-quality development. First, an indicator system is constructed to measure both universities’ STI and regional development performance. A composite development index is then derived using province-level panel data. Second, the non-oriented DEA–SBM (Slack-Based Measure) model is applied to evaluate university innovation efficiency and to identify spatial disparities across regions. Third, the estimated STI scores are incorporated into a two-way fixed-effects regression model. This step allows us to examine the impact of innovation efficiency on regional development. Robustness checks and heterogeneity analyses are conducted to ensure the stability of the results.

Building on the literature on university innovation systems and regional development, this study conceptualizes STI as a key transmission mechanism. Through this mechanism, universities transform research inputs into effective outputs and regional development gains. Compared with output-based indicators, efficiency-oriented measures provide a more accurate assessment. They capture universities’ net contributions by accounting for both input utilization and output performance.

First, higher university STI reflects more efficient transformation of research resources. It strengthens knowledge creation and technology transfer. These processes generate innovation spillovers that support industrial upgrading, ecological improvement, and digital transformation at the regional level. Therefore, improvements in university innovation efficiency are expected to promote regional high-quality development.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Universities’ scientific and technological innovation efficiency has a positive effect on regional high-quality development.

Second, regional disparities in economic foundations, absorptive capacity, and industrial structure may condition the effectiveness with which efficiency gains are translated into development outcomes. In regions with limited resources or ongoing structural transformation, efficiency gains matter more. This is often the case in many central and western provinces. Improved efficiency helps ease key constraints. It also improves the allocation of production factors. As a result, the marginal impact on regional development becomes stronger. In contrast, in regions with mature innovation ecosystems, the impact of efficiency may operate more through spillover and structural rebalancing channels.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The positive impact of universities’ STI on regional high-quality development exhibits significant regional heterogeneity.

Finally, architecture-related disciplines play a distinctive role in linking university innovation to regional development, as their research outputs—such as green construction technologies, digital building methods, and sustainable infrastructure solutions—are closely aligned with regional development goals. Efficiency gains in these disciplines are therefore expected to have a particularly strong developmental effect.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Efficiency improvements in architecture-related university innovation exert a particularly strong influence on regional high-quality development.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it advances an efficiency–mechanism perspective. Unlike output-based evaluations, efficiency is treated as a transmission process rather than a performance indicator. Second, the study integrates efficiency measurement with causal identification. By combining DEA–SBM and a two-way fixed-effects model, efficiency differences are explicitly linked to regional development outcomes. Third, the study highlights the discipline-specific role of architecture-related innovation. Because of its applied and project-based nature, efficiency gains in this field are more likely to generate observable regional impacts.

2. Methodology

This chapter presents the methodological framework of the study. It integrates indicator construction, composite evaluation, efficiency measurement, and econometric analysis into a coherent analytical process. An indicator system is developed to capture both universities’ scientific and technological innovation efficiency and regional high-quality development. The indicators are refined through data preprocessing and expert consultation. A composite index of regional development is then constructed using a hybrid weighting strategy that combines entropy weighting and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), followed by aggregation through the TOPSIS method. University innovation efficiency is measured using a non-oriented DEA–SBM model under constant returns to scale. This approach generates province-level panel data on innovation performance. The estimated efficiency scores are subsequently incorporated into a two-way fixed-effects regression framework to examine their impact on regional development. Robustness checks and heterogeneity analyses are conducted to support the empirical results. The overall technical route of the study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

To balance objectivity and expert judgment, the final indicator weights are obtained by combining entropy-based weights and AHP-based weights with equal importance. The entropy method reflects the information

Content and dispersion of the data, while AHP incorporates expert assessments of the relative importance of each dimension. This hybrid approach helps reduce the limitations associated with relying on a single weighting method.

2.1. Indicator System

This study constructs an indicator system for universities’ STI and regional high-quality development. The design prioritizes validity, data availability, comparability, and robustness. The framework is developed through an iterative “literature–data–expert–statistics” cycle.

In the first stage, informed by existing research and the availability of national statistical yearbooks, a pool of candidate indicators is assembled. This includes inputs and outputs at the university level (e.g., full-time R&D personnel, architectural and engineering research funding, publications, patent authorizations, and research projects) as well as dimensions of regional development (e.g., industrial upgrading, ecological sustainability, and digital transformation). To capture the specific role of architecture-related disciplines, indicators relating to green building patents, construction technology research projects, and digital construction outputs are emphasized.

In the second stage, all candidate indicators are standardized in definition and subjected to consistency checks. Conversion to common units or normalization is applied where needed, while redundancy and multicollinearity are controlled using correlation diagnostics and variance inflation factors.

In the third stage, a two-round Delphi method is employed with 10 experts specializing in higher-education management, regional economics, architecture-related innovation, and S&T statistics [

21]. Experts rate indicators in terms of importance, measurability, and comparability. Retention thresholds are set based on mean values and coefficients of variation, while consensus is assessed through Kendall’s coefficient of concordance. After two rounds of feedback, the final set of indicators and hierarchical structure is confirmed [

11]. For the subjective weighting component, theAHP is implemented based on expert judgment. The expert panel consists of 10 specialists with backgrounds in higher-education management, regional economics, architecture-related innovation, and science-and-technology statistics, drawn from universities, research institutions, government agencies, and international organizations. This composition ensures both disciplinary relevance and practical policy experience. For each judgment matrix, consistency is examined using the consistency ratio (CR), and all matrices satisfy the standard requirement of CR < 0.10, indicating acceptable internal consistency of expert judgments.

To integrate objective data properties with expert judgment, a hybrid weighting method is adopted: entropy weighting provides the objective component, AHP offers the subjective component (with consistency validation), and the two are combined into composite weights [

22]. Subsequently, polarity corrections and directional alignment are performed on all indicators, followed by robust preprocessing for extreme values and minor missing data.

Through this process, the study establishes an indicator system that is both theoretically informed and practically applicable. By embedding architecture-related dimensions within the broader STI framework, the system provides a reliable foundation for subsequent composite evaluation and econometric analysis.

2.2. Data Sources, Indicator Design, and Composite Index Construction

To reduce potential overlap and endogeneity bias, the regional high-quality development index excludes all direct university-level innovation outputs. These include university patents, academic publications, and research projects. In this study, STI measures innovation efficiency at the university level. By contrast, the regional development index captures broader structural, ecological, and digital conditions at the regional level. Some innovation-related indicators are included in the regional index, such as green patents and digital economy metrics. However, these indicators are measured only at the aggregate regional level. They do not refer to university-specific outputs. This design ensures a clear conceptual and statistical separation between the dependent and explanatory variables. Based on these principles,

Table 1 summarizes the final structure of the regional high-quality development index. It reports each dimension, its main content, and the corresponding weight. All indicators are defined at the regional level and remain distinct from university-level innovation measures.

The empirical analysis covers 31 provincial-level regions in mainland China for the period 2012–2023. The data are drawn from multiple official national statistical publications, including the China Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, and the Statistical Compendium of Science and Technology in Higher Education Institutions. These yearbooks are published annually by the National Bureau of Statistics of China and relevant government agencies and provide authoritative and consistent data for regional and university-level analysis. Before proceeding to measurement, all datasets are subjected to a series of treatments—definition harmonization, polarity correction, and robust preprocessing for outliers and missing values—to ensure consistency across provinces and comparability over time.

To ensure consistency and replicability, indicators related to architecture-related disciplines are extracted following unified classification and aggregation rules across all data sources. In this study, architecture-related disciplines include architecture, civil engineering, construction engineering, urban and rural planning, and related engineering fields. This definition is consistent with the disciplinary classifications used in the Statistical Compendium of Science and Technology in Higher Education Institutions and China’s national discipline coding standards.

When extracting university-level innovation inputs and outputs, only data explicitly classified under these architecture-related and engineering-oriented categories are retained. Architecture-related disciplines are defined according to national disciplinary classifications. They include architecture, civil engineering, construction engineering, and urban and rural planning. Regional indicators are derived from sector-level statistics on construction and digital infrastructure. All extraction rules are applied uniformly across provinces and years to ensure comparability and to avoid subjective selection of indicators.

Regional high-quality development is proxied by a composite index emphasizing three dimensions: technological advancement, ecological governance, and digital enablement. STI is modeled from an input–output perspective to reflect the role of universities. Inputs include full-time R&D personnel and university research funding. Outputs capture knowledge and technological outcomes, such as publications, patent authorizations, and research projects. For architecture-related disciplines, special attention is given to green-building patents, Building Information Modeling (BIM)-based research projects, and digital construction innovations. These outputs reflect the sector’s specific contribution to sustainable regional development. The process of indicator selection and weighting follows the procedure outlined in Chapter 3. A pool of potential indicators is assembled on the basis of literature and data availability. Two rounds of Delphi consultation with experts are then conducted to refine the list, after which a hybrid weighting strategy is implemented that combines entropy-based objective weights and analytic hierarchy process subjective weights. The expert panel is composed of 10 specialists from universities, research institutions, government agencies, and international organizations, ensuring both representativeness and global perspectives (see

Table 2). The regional high-quality development indicators are summarized in

Table 3.

The regional high-quality development indicator system is structured in a hierarchical manner, spanning first-, second-, and third-level dimensions. The labor-force quality dimension captures both income returns and talent supply. It includes per capita GDP, average wage, and the share of employment in the tertiary sector, as well as the proportion of highly educated population, education expenditure intensity, and student composition. The industrial development dimension focuses on digitalization and structural upgrading. Key indicators include enterprise informatization, the share of strategic emerging industries, and industrial robot density. This dimension also reflects the growing role of construction-related technologies in industrial transformation. The ecological environment dimension measures environmental quality and green development. It covers forest coverage, environmental protection expenditure intensity, and inverse pollution indicators. The share of green patents, particularly in construction and building technologies, is used to capture green innovation output. Material and intangible production conditions represent the physical and digital foundations of regional development. These indicators include transportation and communication infrastructure, energy efficiency and carbon intensity, pollution treatment capacity, per capita patent grants, new product R&D expenditure, the digital economy index, and enterprise digitalization.

This framework is comprehensive in coverage and logically structured, making it suitable for benchmarking regional differences and for tracing the evolution of structural change over time. By embedding architecture-related dimensions such as green building and digital construction into the index, the system ensures that the contributions of architecture disciplines are explicitly recognized in measuring the efficiency–development nexus.

2.3. Integrated Evaluation and Econometric Analysis

Following the establishment of the indicator framework and the determination of weights, the analysis advances through a three-stage pipeline: composite evaluation → efficiency assessment → effect identification. First, the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is employed to generate a regional composite development index in a multi-indicator setting [

20]. Second, a non-oriented SBM model under the assumption of constant returns to scale is used to evaluate universities’ relative innovation efficiency and to decompose input redundancies and output shortfalls [

23]. These efficiency scores are then incorporated into a two-way fixed-effects model. The model controls for both region and year effects. It is used to estimate the impact of STI on regional high-quality development. Robustness and heterogeneity tests are conducted to validate the results.

2.3.1. Deriving the Regional Development Composite Index

TOPSIS is adopted to synthesize regional development levels for three main reasons. (i) It allows the aggregation of indicators expressed in heterogeneous units without relying on a predefined utility function. (ii) It directly integrates the composite weights derived from entropy and AHP, thus balancing objective information and expert judgment. (iii) It produces a relative closeness measure to the ideal solution, which facilitates both interregional comparisons and temporal tracking [

24].

After normalization, we obtain

. With weights

, the weighted value is given by

. The positive and negative ideal solutions are then defined as:

The Euclidean distances of each region to these ideals,

and

, are computed, and the relative closeness is:

A larger corresponds to a higher level of regional development. This approach is particularly suitable for capturing cross-regional disparities in domains such as green building, sustainable construction, and digital infrastructure—dimensions closely related to architecture-related disciplines.

2.3.2. Assessing Universities’ STI Efficiency

University R&D processes involve multiple inputs and outputs and often present inefficiencies characterized by redundant inputs or insufficient outputs. To avoid the radial DEA assumption that inputs and outputs expand or contract proportionally, this study applies the SBM model under constant returns to scale [

25].

For a given decision-making unit

, denote the input vector as x

o (e.g., dedicated R&D personnel, investment in architecture-related and technological research) and the output vector as

(e.g., academic publications, patents in sustainable construction, externally funded projects). Let

and

represent the input and output matrices for the sample,

the intensity vector, and

and

the slack variables for input redundancy and output shortfall. The corresponding SBM model is formulated as:

In this setting, and correspond to the numbers of input and output variables, while and denote the observed input and output for unit . The efficiency score reflects relative performance, with values approaching 1 indicating higher efficiency. By separating inefficiency into input redundancy and output shortfall, the SBM framework offers concrete diagnostic value for monitoring and enhancing STI processes in universities, particularly within architecture-related disciplines of research and innovation.

It should be noted that the efficiency evaluation is conducted at the provincial level, where each province is treated as a decision-making unit aggregating universities within its jurisdiction. As provinces differ substantially in the number, size, and resource endowment of universities, a higher aggregate output does not necessarily imply higher efficiency. The DEA–SBM framework addresses this concern by evaluating efficiency in a relative sense, comparing each province’s input–output configuration against the best-performing frontier rather than absolute output levels.

Moreover, by estimating both constant returns to scale (CRS) and variable returns to scale (VRS) specifications, this study explicitly distinguishes pure technical efficiency from scale effects. The CRS–VRS comparison allows us to identify whether observed inefficiencies stem primarily from suboptimal resource utilization or from scale-related constraints associated with the size of the provincial higher-education system. Robustness tests suggest that scale advantages exist in some provinces. Nevertheless, pure technical efficiency remains the primary driver of STI performance. This pattern is particularly evident in architecture-related disciplines. Efficiency scores thus capture relative resource utilization rather than institutional size.

2.3.3. Identifying the Impact of STI on Regional Development

To evaluate the effect of universities’ STI on regional development, a two-way fixed-effects regression is applied, controlling for unobservable, time-invariant regional heterogeneity (e.g., geographical and institutional factors) and capturing common macro shocks with year effects [

26]:

In this model, denotes the composite development index of province in year ; is the measured efficiency score; and is the control variable set, including factors such as industrial structure, trade openness, per capita income, government intervention, environmental regulation, and population density. The terms and capture province- and year-specific fixed effects, while is the disturbance term. Unlike random-effects specifications, the fixed-effects approach yields consistent estimates when unobserved, time-invariant factors correlate with explanatory variables. Empirically, standard errors are clustered at the provincial level, and a Hausman test is performed to justify the model choice. To reduce simultaneity bias, the STI variable is lagged in some specifications, and heterogeneity is further explored through subgroup estimations and interaction terms. It should be noted that a potential bidirectional relationship may exist between universities’ STI and regional high-quality development. Higher STI supports regional development through spillovers and upgrading. Meanwhile, more developed regions offer conditions that further strengthen universities’ innovation efficiency.

To mitigate concerns of reverse causality, several empirical strategies are employed in this study. First, a two-way fixed-effects model is adopted to control for unobserved, time-invariant regional characteristics as well as common time shocks that may jointly affect STI and regional development. Second, the core explanatory variable—universities’ STI—is introduced in lagged form in the regression specifications, ensuring that current regional development outcomes are explained by prior-period innovation efficiency rather than contemporaneous values. Third, placebo tests are conducted by replacing the lagged STI variable with its future (lead) values; the estimated coefficients on these lead terms are statistically insignificant, suggesting that future STI does not predict past regional development.

Taken together, these results indicate that the main findings are unlikely to be driven by reverse causality. Nevertheless, a fully dynamic feedback mechanism between university innovation efficiency and regional development cannot be completely ruled out.

3. Illustrative Examples

3.1. Evaluating Universities’ STI Efficiency from the Architecture Perspective

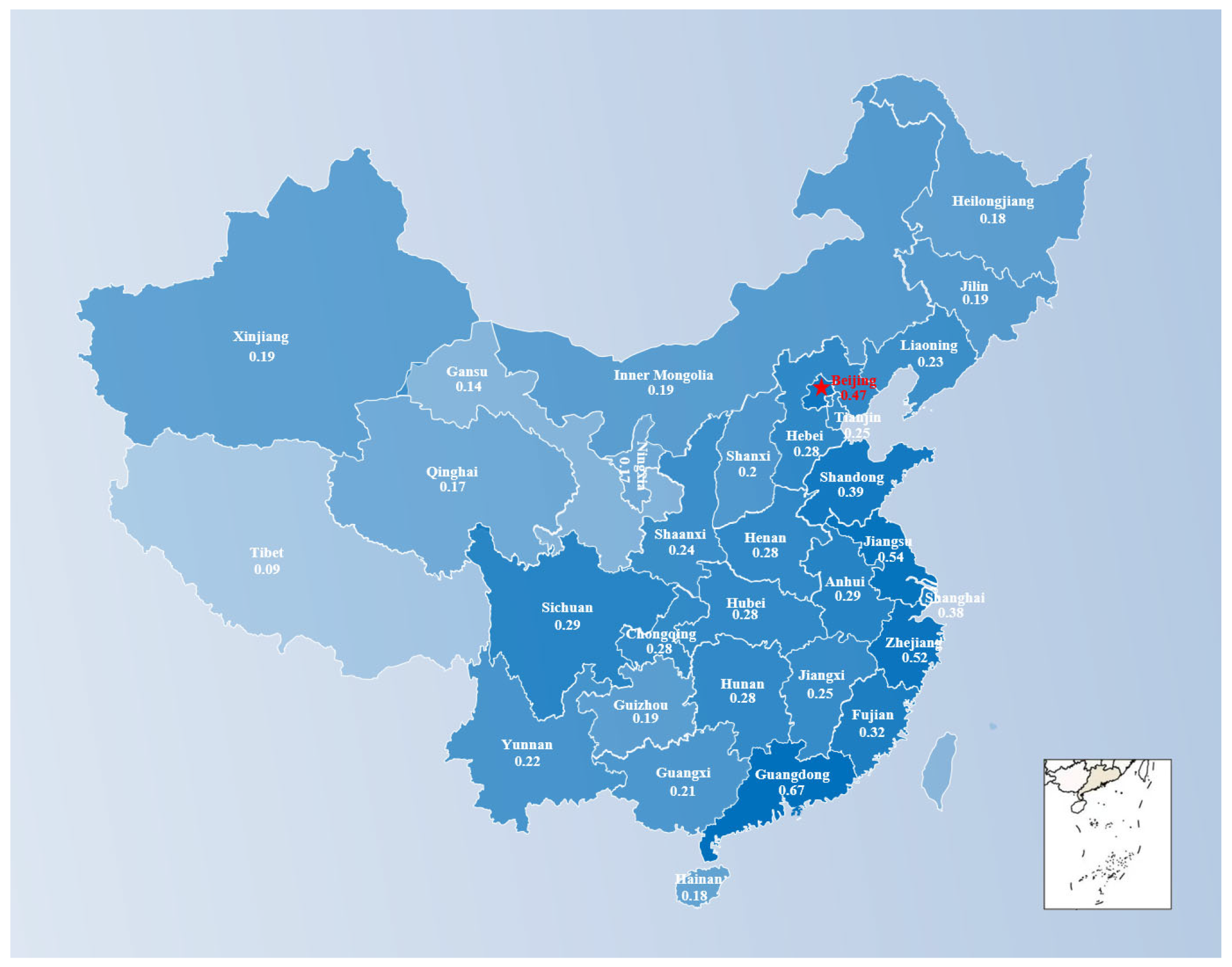

This section evaluates provincial STI efficiency and summarizes its evolution over the sample period, with the results illustrated in

Figure 2. Between 2012 and 2023, the regional high-quality development index increased steadily across China, indicating overall progress in structural upgrading, ecological governance, and digital transformation.

Clear spatial differences are observed. Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Beijing constitute the leading group, supported by concentrated innovation resources, mature industrial chains, and well-developed innovation ecosystems. Shandong, Shanghai, Fujian, and Sichuan form an upper–middle tier, benefiting from strong manufacturing foundations, high external openness, and substantial inputs in science and technology. In contrast, many provinces in the central, western, and northwestern regions (such as Qinghai, Ningxia, Gansu, and Tibet) remain at relatively lower levels. Nevertheless, most of these regions exhibit gradual convergence over time, driven by improvements in infrastructure, the diffusion of digital technologies, and increased investment in environmental governance.

From a component perspective, coastal provinces maintain clear advantages in industrial upgrading and digitalization. Central and western regions, by comparison, have shown notable recent improvements in human capital accumulation, education expenditure, and infrastructure development. Ecological indicators have generally improved nationwide.

Focusing on architecture-related disciplines, eastern regions display stronger performance in construction digitalization, green-building practices, and industrial upgrading. Central and western regions, meanwhile, have accelerated progress in workforce training and infrastructure development related to sustainable construction.

Table 4 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The regional high-quality development index (NQP) and universities’ STI exhibit substantial cross-provincial variation, indicating pronounced heterogeneity across regions. Although some variables display relatively wide ranges, no abnormal values are observed. To mitigate the influence of potential outliers, all variables are subjected to robust preprocessing, including winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles, ensuring the stability of subsequent regression results.

From a temporal perspective, the composite index for China as a whole and its four macro-regions shows a clear upward trend. The eastern region consistently maintains the highest level and fastest growth. The central and western regions advance steadily and gradually converge toward the national average, whereas the northeast experiences modest recovery amid fluctuations (see

Figure 3).

Consistent with these dynamics, universities’ STI efficiency also demonstrates considerable cross-provincial heterogeneity. Efficiency frontiers are concentrated in several northern and eastern provinces. Many non-frontier regions exhibit clear inefficiencies. These inefficiencies often take the form of redundant R&D funding combined with insufficient outputs, including publications, patents, and completed research projects.

Over time, STI efficiency has improved steadily across the country. This trend reflects better financial management, more optimized project portfolios, and more effective technology transfer mechanisms. In architecture-related disciplines, universities are increasingly aligning research inputs with concrete outcomes. These outcomes include green-construction patents, BIM-driven projects, and digital design outputs. As a result, the gap between inputs and outputs has gradually narrowed. To identify the influence of STI on regional high-quality development, a two-way fixed-effects regression is applied. The dependent variable is the composite index of regional development, while the core explanatory variable is universities’ STI efficiency. Control variables include industrial structure, openness to trade and investment, economic development level, government intervention, environmental regulation, and population density. To reduce simultaneity and potential reverse causality, the STI measure is lagged in selected specifications. In addition, cluster-robust standard errors are reported, and subsample analyses are carried out to investigate regional heterogeneity, with particular attention to construction- and architecture-related contributions to regional development.

3.2. Regression Analysis and Spatial–Temporal Visualization from the Architecture Perspective

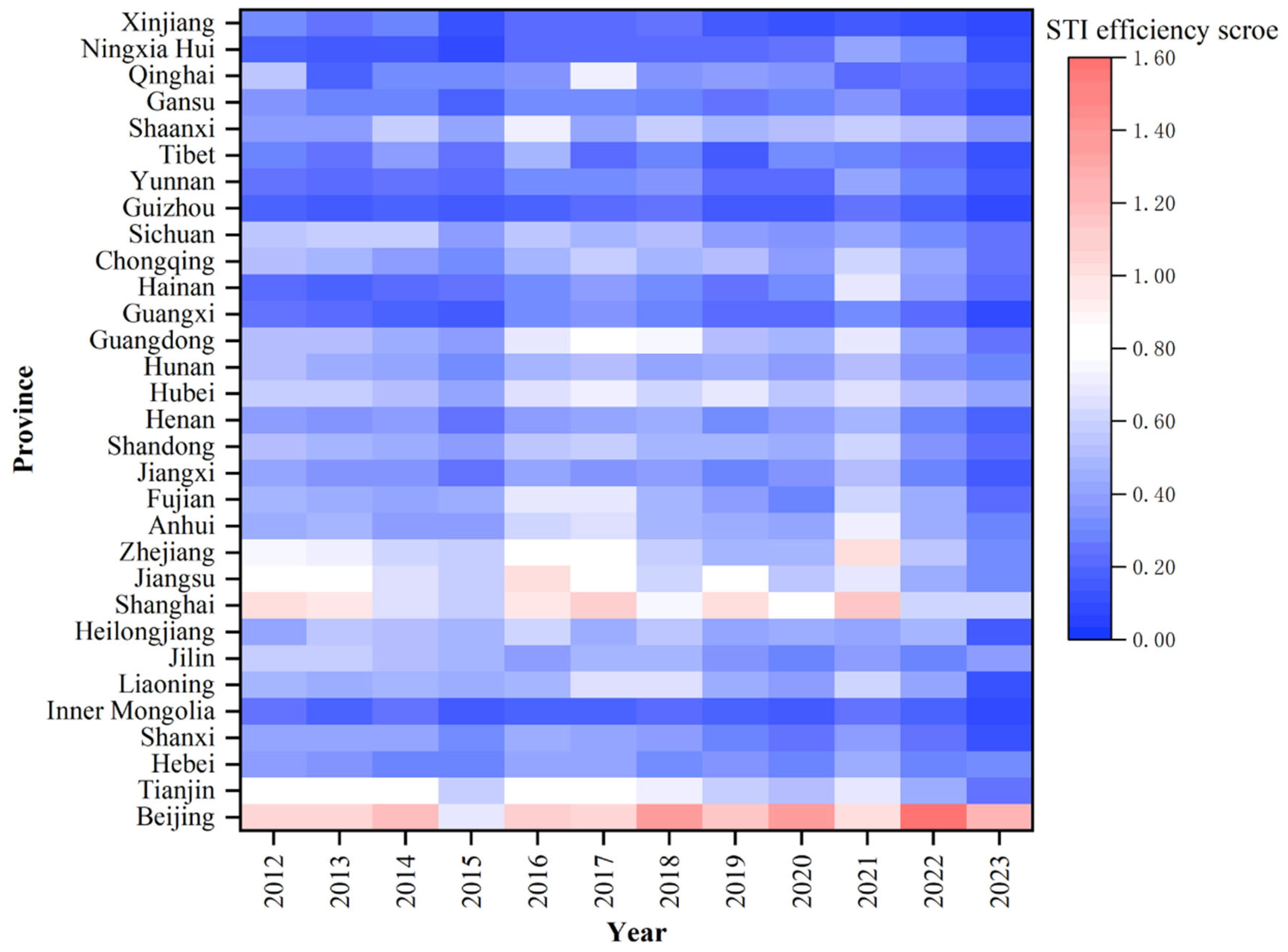

Building on the composite index constructed earlier, this section examines the statistical linkage between universities’ STI and regional development outcomes, while also providing a spatio-temporal overview that highlights efficiency differences across provinces. As illustrated in

Figure 4, efficiency frontiers are consistently concentrated in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, where universities frequently approach or reach maximum efficiency. Most provinces in central, western, and northeastern China remain in the middle-to-lower range, though many have shown steady improvement in recent years, reflecting progress in governance capacity, resource allocation, and investment strategies. A handful of provinces display short-term fluctuations, suggesting that shifts in funding structure or project portfolios can temporarily influence efficiency levels. In architecture-related disciplines, leading provinces convert resource endowments into stronger innovation outputs, such as green-building patents, BIM-related research, and construction technology transfer. This reinforces their frontier positions.

Regression outcomes are reported in

Table 5. Using the regional high-quality development composite index as the dependent variable, STI shows a consistently positive and statistically significant effect. In baseline regressions without controls, the STI coefficient is already positive and robust. When urbanization (URB), industrial structure (IN), enterprise activity (ENT), per capita income (PGDP), openness (OPEN), government intervention (GOV), and environmental regulation (ER) are included, the positive effect of STI persists, underscoring its contribution to development quality. Control variables generally behave as expected: URB, ENT, PGDP, and OPEN are mostly positive, highlighting the roles of agglomeration, firm activity, economic strength, and openness; IN is negative under several models, consistent with concerns that dependence on traditional industries constrains upgrading; GOV and ER show unstable signs, reflecting regional and temporal variation in governance effectiveness. Results remain robust when extreme values are trimmed or the sample is split into early (2013–2017) and later (2018–2023) subperiods, with stronger effects observed in the latter, suggesting cumulative impacts of efficiency gains.

Regional heterogeneity is further examined in

Table 6. Across all four macro-regions, STI retains a positive and significant effect. Coefficients are larger in the Central and Eastern regions, while Western and Northeastern provinces show smaller but still significant effects. These differences align with regional factor endowments and development stages: in areas facing resource constraints or structural transformation, efficiency improvements are more easily converted into development gains; in more advanced eastern provinces, efficiency effects manifest through structural rebalancing and spillover channels. For architecture-related disciplines, efficiency gains in the East are often linked to digital construction and sustainable building technologies, whereas in the Central and Western regions, contributions stem from improved training pipelines and infrastructure for construction innovation. Control variables vary in sign and significance across subregions, indicating context-specific dynamics shaped by industrial bases, openness, and policy frameworks.

Overall, universities’ STI exerts a stable and significant positive influence on regional high-quality development, with clear spatial heterogeneity and evidence of cumulative strengthening over time. These findings highlight the role of architecture-related innovation—particularly green construction, digital building technologies, and applied research outcomes—in shaping regional growth trajectories. The next section extends the analysis through robustness checks and mechanism exploration.

3.3. Robustness Verification and Discussion from the Architecture Perspective

To enhance the credibility of the findings and ensure that the interpretations hold across different settings, a series of robustness checks are carried out from four perspectives.

The regional high-quality development index is recalculated under alternative weighting schemes—including hybrid, equal-weight, and purely entropy-based methods—and using different normalization techniques. Across all variants, STI maintains a positive and significant coefficient. Although effect sizes vary slightly, the changes remain within an interpretable range, suggesting that the observed impact is not an artifact of weighting or scaling procedures.

- 2.

Efficiency estimation strategy.

Alternative DEA models are tested, such as variable returns to scale (VRS) and bootstrapped DEA. The non-oriented SBM is compared against radial DEA, and the composition of outputs is adjusted by alternately focusing on publications, patents, or project counts. In all cases, STI continues to show a significant positive association with the development index. The CRS–VRS comparison further indicates that while certain regions face scale-related constraints, improvements in pure technical efficiency remain the primary driver of gains. For architecture-related disciplines, this implies that efficiency advances in construction-oriented patents, BIM-based projects, and digital design outputs contribute substantially to regional performance, even in contexts with uneven resource scales.

- 3.

Sample design and inference approach.

On the sampling side, robustness is confirmed by excluding municipalities or the largest provinces, trimming extreme values at both 1st/99th and 5th/95th percentiles, and switching between balanced and unbalanced panels. On the inference side, province-clustered robust standard errors are the baseline, and Driscoll–Kraay corrections are applied to address potential cross-sectional dependence. Statistical significance remains unchanged. To mitigate simultaneity and reverse causality, STI variables are lagged; results remain consistent. A placebo test substituting STI with its one-period lead yields no significant effect, undermining the hypothesis that “development mechanically precedes efficiency.”

- 4.

Heterogeneity and mechanisms.

Subgroup regressions reveal stronger effects in provinces where factor endowments are constrained or structural transitions are actively underway, and somewhat smaller yet positive impacts in resource-rich regions with mature innovation systems. Interaction terms between STI and proxies for digital infrastructure, industrial upgrading, and green governance all return broadly positive coefficients. This implies that greater absorptive capacity—through mechanisms such as digital construction platforms, improved IP protection, and revenue-sharing arrangements—magnifies the developmental impact of efficiency. Sensitivity checks that replace the dependent variable with specific index subcomponents or a principal-component factor also confirm robustness. Specifications with spatial-lag terms reveal stable core effects alongside meaningful spatial spillovers.

Taken together, evidence across index definitions, efficiency models, sampling strategies, and mechanism tests consistently underscores that enhancing universities’ STI is a powerful lever for promoting regional high-quality development. For architecture-related disciplines, efficiency gains in green construction research, sustainable building practices, and digital innovation translate more readily into tangible improvements in development quality, provided that institutional mechanisms for absorption and diffusion are well designed.

3.4. Discussion

This section discusses the empirical findings from an interdisciplinary perspective, with a particular focus on the distinctive characteristics of innovation efficiency in architecture-related disciplines and the broader applicability of the results.

First, the results highlight the unique role of architecture-related disciplines in regional innovation systems. Architecture-related disciplines differ fundamentally from science-oriented or laboratory-based fields. They are application-driven and deeply embedded in regional production systems. Their innovation activities are closely linked to construction practice, urban development, infrastructure provision, and green transformation. These activities depend heavily on local demand, regulatory frameworks, and implementation capacity.

As a result, innovation efficiency in architecture-related disciplines reflects more than the productivity of knowledge creation. It also captures how effectively academic knowledge is transformed into regionally relevant technological and organizational outcomes. This characteristic helps explain why improvements in universities’ innovation efficiency in architecture-related fields are more directly associated with regional high-quality development. The effects are particularly evident in industrial upgrading, ecological performance, and digital construction.

Second, from an interdisciplinary comparative perspective, the efficiency–development linkage identified in this study differs in nature from that typically observed in more basic or science-intensive disciplines. In fields such as mathematics or fundamental physics, innovation outputs usually involve long time lags. Their spatial anchoring is relatively weak. Regional spillovers often emerge slowly through human capital mobility or national research networks. By contrast, innovation in architecture-related disciplines follows much shorter feedback loops. Research outputs are quickly incorporated into local construction projects, technical standards, and policy-oriented demonstration programs. This structural feature strengthens the link between university innovation efficiency and regional development outcomes. It also highlights the need to consider disciplinary heterogeneity when applying regional innovation theory. By embedding efficiency in a discipline-specific and regionally grounded context, this study moves beyond frameworks that treat university innovation as a homogeneous input to regional growth.

The empirical results show clear spatial heterogeneity. Eastern regions exhibit higher innovation efficiency, while western regions remain at lower levels. This difference is partly driven by the uneven distribution of architecture-related universities and related disciplinary resources. Eastern provinces host a dense concentration of high-ranking universities with strong programs in architecture, civil engineering, and urban planning. These institutions are often embedded within well-developed disciplinary clusters. They benefit from advanced research platforms and close collaboration with industry. They also have greater access to large-scale construction projects and urban renewal initiatives. These conditions facilitate the efficient transformation of research inputs into applied innovation outputs. As a result, innovation efficiency in architecture-related disciplines in eastern regions reflects more than scale advantages. It also captures the presence of mature institutional arrangements and supportive industrial environments that enable effective knowledge application.

Beyond documenting regional heterogeneity, the results also shed light on the differentiated mechanisms through which innovation efficiency in architecture-related disciplines affects regional development.

In eastern coastal regions, where architecture schools, design institutes, and construction enterprises are densely concentrated, innovation efficiency primarily operates through technology deepening and industrial upgrading channels. High-efficiency universities are embedded in mature innovation ecosystems characterized by strong market demand, advanced digital construction platforms, and well-established green-building standards. Under such conditions, efficiency improvements are translated into development outcomes mainly via the diffusion of digital construction technologies, sustainable building practices, and high-value-added engineering services. Policy implications for these regions therefore lie less in expanding resource inputs and more in strengthening interregional spillovers, technical standardization, and cross-regional innovation alliances.

In contrast, central regions exhibit stronger marginal effects of innovation efficiency largely because architecture-related innovation is absorbed through project-based and demand-driven mechanisms. Ongoing infrastructure expansion, urban renewal, and public construction programs create immediate application scenarios for university-generated knowledge. Even modest improvements in innovation efficiency can thus generate disproportionately large development gains, as efficiency-enhanced research outputs are rapidly embedded into construction projects and policy-oriented initiatives. This mechanism explains why estimated coefficients are larger despite these regions not occupying the efficiency frontier.

For western regions, the role of innovation efficiency is more closely linked to capacity building and bottleneck alleviation. Architecture-related universities in these areas often face constraints in market access, institutional coordination, and talent retention. Efficiency improvements therefore contribute primarily by reducing input redundancy, improving project completion rates, and strengthening the basic innovation–application interface. While short-term development effects may appear weaker, such efficiency gains constitute a necessary foundation for long-term regional upgrading. Correspondingly, policy design should prioritize talent support, demonstration projects, and cross-regional collaboration to enhance absorptive capacity.

By contrast, the stronger marginal effects of innovation efficiency on regional high-quality development observed in central regions do not necessarily imply higher absolute efficiency levels, but rather reflect differences in resource endowments and absorptive capacity. In many central provinces, ongoing infrastructure expansion, urban redevelopment, and public investment programs generate substantial demand for architecture-related innovation. Under such conditions, incremental improvements in university innovation efficiency can yield disproportionately large development effects, as efficiency gains are rapidly absorbed through project-based implementation and policy-driven construction initiatives. This mechanism helps explain why central regions exhibit larger estimated coefficients despite not occupying the efficiency frontier, highlighting the importance of considering regional development stages when interpreting spatial heterogeneity.

Third, the findings also bear implications for the international relevance of the proposed mechanism. Although the empirical analysis is based on Chinese provincial data, the underlying logic is not country-specific. Regions with a strong concentration of architecture schools and engineering-oriented universities often share similar institutional features. These regions include Greater London, the Boston metropolitan area, Zurich, and Singapore. They typically show close university–industry linkages. Knowledge transfer is often project-based. Policy coordination in urban development and sustainable construction is also strong.

In such contexts, innovation efficiency in architecture-related disciplines functions as a key transmission channel. It links academic research to regional competitiveness and sustainability outcomes. While institutional settings differ across countries, the core efficiency-based mechanism is likely to persist. This is especially true in regions where architecture-related innovation is closely aligned with local development agendas.

Finally, this discussion underscores the theoretical contribution of reframing innovation efficiency as an active mechanism rather than a descriptive performance indicator. By situating efficiency within specific disciplinary structures and regional environments, the study moves beyond conventional “efficiency–outcome” correlations and advances regional innovation theory toward a more nuanced understanding of how universities influence development through differentiated innovation pathways. This perspective is particularly relevant for applied and interdisciplinary fields, where the alignment between academic innovation and regional needs plays a decisive role in shaping development trajectories.