Abstract

Rising temperatures, extreme precipitation events such as excessive or insufficient rainfall, increasing levels of carbon dioxide, and associated climatic factors will persistently impact crop growth and agricultural production. The warming temperatures have reduced the agricultural crop yields. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is the major food crop, which is particularly susceptible to the effects of climate change. It is very important to accurately evaluate the impacts of climate change on rice growth and rice yield. In this study, the rice growth during 1981–2018 (baseline period) and 2041–2100 (future period) were separately simulated and compared within the CERES-Rice model (v4.6) using high-quality weather data, soil, and field experimental data at six agro-meteorological stations in Hainan Province. For the climate data of the future period, the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios were applied, with carbon dioxide (CO2) fertilization effects considered. The adaptation strategies such as adjusting planting dates and switching rice cultivars were also assessed. The simulation results indicated that the early rice yields in the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s were projected to decrease by 6.2%, 11.8%, and 20.0% when the CO2 fertilization effect was not considered, compared with the results of the baseline period, respectively, while late rice yields would decline by 9.9%, 23.4%, and 36.3% correspondingly. When accounting for the CO2 fertilization effect, the yields of early rice and late rice in the 2090s increased 16.9% and 6.2%, respectively. Regarding adaptation measures, adjusting planting dates and switching rice cultivars could increase early rice yields by 22.7% and 43.3%, respectively, while increasing late rice yields by 20.2% and 34.2% correspondingly. This study holds substantial scientific importance for elucidating the mechanistic pathways through which climate change influences rice productivity in tropical agro-ecosystems, and provides a critical foundation for formulating evidence-based adaptation strategies to mitigate climate-related risks in a timely manner. Cultivar substitution and temporal shifts in planting dates constituted two adaptation strategies for attenuating the adverse impacts of anthropogenic climate change on rice.

1. Introduction

In the past decades, the global warming trend has become increasingly apparent, and agriculture is directly and indirectly affected by climate change [1,2]. Previous studies reported that a 1 °C rise in global mean surface air temperature translates into proportional yield penalties of 6.0% for wheat, 3.2% for rice, 7.4% for maize, and 3.1% for soybean [3]. Climate change has significant negative impacts on agricultural production, and food security has become a worldwide concern as the population increases. China has sustained 19% of the global population on merely 7% of the world’s cultivated land area, and thus, the stability of grain production in China is critical to guarantee national and even global food security [4,5]. Rice, as one of the three main grain crops, accounts for 30.4% of grain production in China. It has been reported that climate change has shortened rice phenology, which has further significantly reduced rice yields [6,7]. Across tropical and subtropical Asia, including southern China, post-heading heat episodes exceeding 35 °C currently impose a yield penalty of approximately 3% per 1 °C increment in rice, with field evidence from the Mekong Delta and South China attributing these losses to elevated pollen sterility and a contracted effective grain-filling duration [3]. Climate projections indicated that, by 2050, such thermal extremes are expected to affect 60% of rice-growing seasons, translating into a prospective 10–15% contraction in national rice output in the absence of widespread adoption of heat-tolerant cultivars or systematic shifts in sowing calendars [8]. Hainan Province served as a primary rice-producing region, with rice output constituting 87% of the total grain production. The tropical monsoon maritime climate, combined with the warming effects, poses great challenges to rice production in the region [9,10]. Therefore, exploring the climate change impacts on rice yields in Hainan Province is of great significance for regional food security.

At present, there are three main approaches for exploring the climate change impacts on crop growth and yield: field sampling survey, statistical analysis, and crop model simulation [11]. Field sampling surveys observe the effects of climate change on crops in the most intuitive way by monitoring meteorological factors and the changes in CO2 concentration. However, field sampling surveys are time-consuming and laborious, which are also subjective and are only applicable to a limited number of stations [12,13]. Statistical analysis involves separating trends in crop yields, followed by statistical modeling (such as univariate regression and multiple regression), and individually assessing the impact of climate factors on crop yields [14]. Previous studies have conducted many statistical analyses on the impacts of climate change on rice growth and rice yield. However, such statistical approaches can hardly capture the true causal effects of climate variability and change on rice performance as they are constrained by endogeneity, collinearity, and the absence of physiological processes. Process-based crop models, in contrast, integrate thermodynamic, hydraulic, and carbon-allocation routines that mechanistically capture phenological development, biomass partitioning, and spikelet fertility, thereby overcoming the purely correlational constraints of statistical approaches. When forced with bias-corrected climate projections derived from future emission scenarios, these models generate physiologically explicit, site-specific forecasts of rice performance under anticipated climates, a strategy now widely employed in climate-impact assessments. Crop models are computer simulation systems based on the mechanisms of crop growth processes, which can quantitatively describe the relationship between climate change and crop dynamic growth. Crop models have advantages in their robust mechanistic properties, strong extrapolation capabilities, and high reliability in forecasting crop yields under future climate scenarios [15,16,17].

The CERES-Rice model was embedded in the Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer (DSSAT), and it was widely used [18,19,20]. The high-quality input data are the key for ensuring the accuracy of the simulation results [21]. China’s national agricultural meteorological stations provide monitoring and data collection of crop growth and development processes, which offers reliable data for model simulations [22]. With these data, many researchers have applied the CERES-Rice model for investigating the impacts of climate change on crop yields in China [23,24,25]. Alejo applied the CERES-Rice model and found that, by the late twenty-first century, projected climate change would depress the likelihood of aerobic rice yield gains in the Philippines from 83% to 53%, whereas the probability of yield losses would rise from 15% to 77% [26]. Refinement of the sowing window has been demonstrated to be an efficacious lever for offsetting such losses; integrating the CERES-Rice model with downscaled daily meteorological forcing, Ansari et al. forecasted an 11.8% yield penalty for the second dry season of 2050 under RCP8.5 in the Keduang sub-catchment, Central Java, Indonesia [27]. Habib-ur-Rahman et al., employing the DSSAT modelling framework, projected future yield penalties of 15.2% for rice and 14.1% for wheat across five agro-ecological sites in Pakistan [28]. They further demonstrated that strategic adjustments in crop management practices including sowing date optimization, planting density modification, and improved water and nitrogen management can significantly enhance the productivity of the rice–wheat cropping system. Gunawat et al., deploying the DSSAT-CERES-Wheat model in the semi-arid tract of Western India, projected consistent yield contractions under both RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 across near- and long-term horizons, while concurrently demonstrating that synchronized shifts in sowing calendar and optimized planting density can substantially offset anticipated losses [29]. Integrating SWAT-DSSAT with a reservoir algorithm and bias-corrected CMIP6 SSP5-8.5 forcings, Sreeshna et al. projected end-century rice yield penalties of 13.2% in the wet season and 52.5% in the dry season across five Indian basins, driven by a 67% precipitation increase coupled with a 6 °C rise in mean temperature [30].

Many previous studies only applied a single climate scenario to explore the impact of climate change on rice. The use of multi-climate model ensembles can provide better prediction quality. However, few previous studies have considered CO2 fertilization effects, which could increase the uncertainty of assessing the impacts of climate change on rice growth and yield. Most previous studies only simulated rice yields under future climate change, while few assessed the adaptive measures such as switching rice cultivars, adjusting planting dates, and optimizing water and fertilizer use and planting area [31]. Besides, many previous studies only focused on subtropical regions, while tropical regions were rarely involved. Hainan Province is located in the tropics, and the rice planting area accounts for 83.8% of the total grain area. However, the environmental temperature where rice grows is high, and the high-temperature threshold that is limiting the growth of rice may soon be reached, causing a potential risk of yield reduction. So far, the magnitude of this risk is not well investigated. Additionally, only a limited number of studies have investigated the impact of climate change on rice in Hainan Province. Since the temperature continues to increase, it is equally important to investigate the potential shifts in rice production in Hainan Province. Most studies conducted the impacts of climate change, but the adaptative measures were merely evaluated.

In this study, the impact of climate change on rice from 1981 to 2018 was assessed using the CERES-Rice model using soil and meteorological data from six agricultural experimental stations in Hainan Province. The rice yields were also simulated from 2041 to 2100 using the model, and adaptive measures were implemented. The main objectives were: (1) to calibrate and validate the CERES-Rice model using high-quality historical data from six agricultural experimental stations in Hainan Province; (2) to assess the potential impacts of future climate scenarios on rice phenology and yield, with consideration the CO2 fertilization effect; and (3) to assess the adaptation measures, such as adjusting rice planting dates and switching rice cultivars under future climate scenarios.

2. Data and Method

2.1. Study Area and Agricultural Meteorological Stations

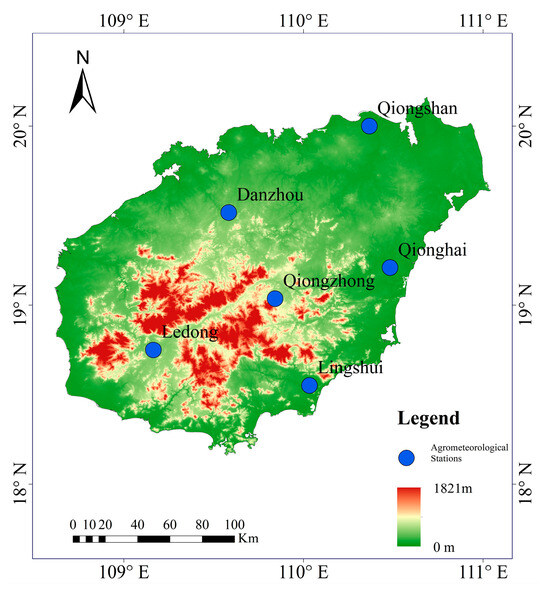

Hainan (18°10′–20°10′ N, 108°37′–111°03′ E) (Figure 1) is in the tropical monsoon climate zone, which falls within the tropical monsoon climate belt and exhibits a mean annual air temperature of 22~26 °C. This region is characterized by abundant rainfall, with an average annual precipitation of 2068.6 mm. The favorable climatic conditions provide an ideal environment for rice cultivation. Double-cropped rice is predominantly grown in this area, with the early rice season extending from February to June, whereas the late rice season spans June to November.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution map of agro-meteorological stations of the study area.

Comprehensive field management documentation including phenological observations and grain yield records covering the 1981~2018 period was assembled from six agro-meteorological stations strategically distributed across Hainan Province: Qiongshan, Danzhou, Qiongzhong, Qionghai, Ledong, and Lingshui.

These datasets were subsequently employed for the calibration and validation of the CERES-Rice model. Field agronomic data were compiled from the national network of agro-meteorological experimental stations administered by the China Meteorological Administration (CMA). Certified agro-meteorological observers strictly adhered to standardized protocols, conducting manual phenological surveillance and destructive harvests within designated micro-plots to guarantee temporal continuity, methodological homogeneity, and full traceability of all rice developmental and yield data [32].

Records from each station were screened and retained according to the following criteria: (1) the stations are located in the main rice-producing areas; (2) the same representative rice cultivar was grown for at least three years between 1981 and 2018; and (3) there were no pest and disease issues or extreme climate disasters across rice phenology, and the management measures were effective [33]. The selected rice growth years were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Metadata for experimental stations and selected cultivars employed in model calibration and validation are summarized below. The year in bold is the calibration year, and the other years are validation years.

2.2. The Introduction of CERES-Rice Model

The CERES-Rice model is widely used, incorporating models of 16 crops. Recently, it has been redesigned with a modular structure to improve efficiency and facilitate updates [34]. The new DSSAT-CSM includes several key modules: a soil module, a crop template module for simulating different crops, an interface for adding individual crop models, a weather module, and a module for light and water competition. This modular design allows for versatile applications, ranging from research adaptation to production simulation. The CERES-Rice model integrates environmental factors, genetics, and management practices to dynamically describe the crop growth process. It is capable of performing hundreds, or even thousands of simulations in a short period, making it a powerful tool for agricultural research and decision making. In terms of rice growth, the CERES-Rice model categorizes the rice growth cycle into two main stages: vegetative growth and reproductive growth. These phases are further divided into seven distinct stages: juvenile, floral initiation, heading, flowering, grain filling, maturity, and harvest. This detailed breakdown enables precise modeling of the rice growth process under various conditions. The phenology stage in the model was controlled by the accumulation of Growth Degree Days (GDD), and the definition was given as follows:

Tbase, Thigh, Topt represented the cardinal temperatures for rice development: base (lower threshold), optimum, and critical maximum temperature, and T is the observed temperature, respectively.

2.3. Input Data

2.3.1. Historical Meteorological Data

The meteorological data for the baseline period (1981–2018), including sunshine hours, daily maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation were acquired from the National Meteorological Science Data Centre (https://data.cma.cn). Hourly data are from national surface stations in China, including hourly observational weather variables such as temperature, pressure, relative humidity, moisture pressure, wind and precipitation. The data was processed using a standard procedure to obtain the daily meteorological data for the six agricultural meteorological stations.

2.3.2. Future Climate Scenario Data

Simulations of rice growth under SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, corresponding to low, medium, and high radiative forcing pathways, were selected from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6) [35,36]. These pathways represent a range of plausible future climate trajectories based on varying levels of greenhouse gas emissions and socio-economic development. To provide robust climate projections, data from five atmospheric circulation models were utilized: GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2-0, and UKESM1-0-LL [37,38,39,40,41]. These models were selected for their comprehensive representation of climate dynamics and excellent ability to provide detailed climate projections under the selected SSP scenarios. The climate data from these models underwent bias correction and downscaling to 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution through the Scenario Model Intercomparison Program as part of the CMIP6. This process ensured that the climate data were in consistency with observed climate patterns and suitable for regional climate impact assessments (see Table A1 for details). The processed climate data were subsequently used to extract daily weather data for six agricultural meteorological stations [42,43,44]. This step was crucial for generating site-specific climate inputs required for the simulation of rice growth under future climate conditions.

2.3.3. Soil Data

In this study, the required soil data for each agro-meteorological station was obtained from the China Soil Science Database (http://vdb3.soil.csdb.cn). This database provided comprehensive soil information, including soil particle size, color, type, slope, runoff curve numbers, pH, fertility, organic matter content, and cation exchange capacity [45]. The soil data were recorded in grid format, allowing for spatially explicit analysis. To acquire the relevant soil properties for each agro-meteorological station, the geographic coordinates of the stations were used to extract the corresponding soil attributes from the gridded dataset. This approach ensured that the soil data were spatially consistent, thereby enhancing the accuracy and relevance of the soil data for the study.

2.3.4. Field Management Data

The field management data included the rice phenology (sowing date, emergence date, transplanting date, flowering and maturity date), cultivar, and yield [46]. Field agricultural observations were managed and recorded by professional agricultural managers, thus improving the reliability of model simulation results.

2.4. Model Calibration, Validation

The well calibrated CERES-Rice model could enhance the simulation results. In this study, the model was calibrated using Generalized Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation (GLUE). It is a tool that adjusts genetic parameters of crop cultivars to match the simulated phenological periods (flowering and maturity) and yields using observations. The calibrated crop genetic parameters and the datasets of other years for cross-validation. The assessment of the model is a comprehensive evaluation of the simulation capability and performance of the model. It is an effective method for measuring the accuracy of simulation results against observations. In this study, the data of one year was applied for model calibration, and the data of other two years was used for the validation (Figure 2). Rice phenology and yields were tested using the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) and Prediction Deviation (PD).

where, Si and Oi are the simulated and observed value, is the observed data mean value, and n is the number of comparisons.

Figure 2.

The detailed workflow of assessing the climate change and adaptative measures on rice growth and rice yield using DSSAT.

2.5. Evaluation of Climate Change Impacts

The climate change impacts were evaluated using the stepwise regression, and the factors included mean daily temperature, daily precipitation, and mean daily solar radiation, on yield variability. The impact of the CO2 fertilization effect on rice yields was also assessed [47]. When considering CO2 concentrations, the CO2 fertilization effect was assessed by comparing the simulation results for the 2090s (2081–2100) period relative to the baseline (1981–2018) under three future scenarios. The comparison formula is given as follows:

In the equation, Ya represented the simulated rice yields under the future time period, Yb represented the rice yields under the baseline period, and the variable Yd represented the change compared to baseline period.

2.6. Evaluation of Adaptative Measures

The IPCC proposed several adaptation strategies to address climate change impacts. These strategies include modifying sowing dates, changing crop cultivars, developing new crop varieties, and enhancing field management practices including nutrient inputs, water management, and phytosanitary interventions. Among these, switching to high-temperature-tolerant rice cultivars and adjusting planting dates are two commonly applied adaptations. These two strategies were selected in this study to assess the effectiveness of adaptive measures in mitigating the impact of high temperatures on rice yields.

To ensure successful adaptation when switching rice cultivars, it is essential to maintain similar climatic conditions, particularly in terms of temperature and solar radiation, between the original and selected sites. Therefore, high-yielding rice cultivars with high temperature tolerance were sourced from other sites that share comparable climatic characteristics with the selected sites. The simulation was conducted by strictly controlling other influencing factors, such as temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation, to remain constant. Additionally, the effectiveness of adjusting planting dates was also evaluated.

To optimize the planting dates, the effects of shifting planting dates on rice yields were systematically evaluated. Specifically, planting dates were adjusted both earlier and later by increments of 5 days, up to a maximum shift of 30 days. The simulation results were then compared against those obtained using the current planting dates for the selected stations. For each rice cultivar, the optimal planting date was determined as the one that maximized rice yield while also ensuring yield stability, a critical indicator of rice production resilience in the face of climate change.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Change Scenarios

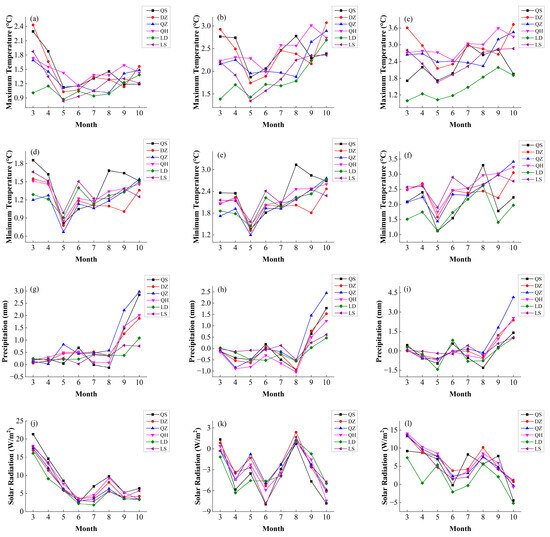

Table 2 showed the ensemble mean changes in annual average maximum and minimum temperature, precipitation and solar radiation during future periods 2050s (2041–2060), 2070s (2061–2080), and 2090s (2081–2100) compared to the baseline period (1981–2018) under SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 at six stations in Hainan Province. Figure A1 showed the ensemble mean of monthly average changes in climate variables during the period (2041–2100) relative to the baseline (1981–2018) of six stations under three SSPs scenarios.

Table 2.

Changes in ensemble mean of annual average maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation and solar radiation under SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 relative to the baseline.

As indicated in Table 2, the ensemble mean of annual average maximum temperature increased 1.01, 1.58, and 1.64 °C under SSP1-2.6, 0.94, 2.12, and 3.69 °C under SSP3-7.0, 0.96, 2.59, and 4.64 °C under SSP5-8.5, in the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s, respectively. As shown in Figure A1a–c, the increasement in maximum temperatures under the three scenarios mainly occur in March, April, July, August, September, and October, respectively.

The ensemble mean of annual average minimum temperatures increased by 0.97, 1.53, and 1.56 °C under SSP1-2.6, 0.92, 2.08, and 3.49 °C under SSP3-7.0, and 0.93, 2.53, and 4.42 °C under SSP5-8.5, in the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s, respectively. Figure A1a–f illustrated that the ensemble mean of monthly average minimum and maximum temperatures at each station have similar trends, with the ensemble mean of monthly average minimum temperature showing smaller increases than the ensemble mean of monthly average maximum temperature. Moreover, the increases in minimum temperatures were mainly concentrated in March, April, June, August, September, and October.

Under the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, the ensemble mean of annual average precipitation showed varying degrees of increase in the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s; the detailed data can be seen in Table 2. Figure A1a–c,g–i showed that the ensemble mean change in monthly average precipitation exhibited an opposite trend from that of the maximum temperature. The increases in precipitation were mainly concentrated in June, September, and October.

The solar radiation increased by 1.33, 6.20, and 7.21% under SSP1-2.6, changed by −2.32, −2.90, and 0.24% under SSP3-7.0, and increased by 0.28, 3.50, and 6.91% under SSP5-8.5, in the 2050s, 2070s, and 2090s, respectively (Table 2). As shown in Figure A1, the solar radiation (j, k, l) exhibits an opposite trend from that of precipitation (g, h, i), and the spatial distribution of the mean changes in monthly mean solar radiation (j, k, l) is similar to the maximum temperature (a, b, c). In addition, the solar radiation increased mostly in May, June, and October.

3.2. Model Calibration and Validation

In Figure 3, the NRMSE between calibrated and validated results (flowering, maturity and yield) and the observed data using the CERES-Rice model were 5.9, 4.2, and 5.3%, respectively. The results indicated that the Prediction Deviation (PD) was uniformly distributed within the ±15% error line.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of flowering durations (a), maturity durations (b), and yield (c). The solid lines represent the 1:1 line, and the broken lines refer to the error with ±15%.

Table 3 presented the genetic parameters of rice cultivars at each station following calibration and validation. In conclusion, the CERES-Rice model simulation results were well and can be applied for simulating the dynamic growth of rice at each station in Hainan Province.

Table 3.

Calculated genetic parameters for selected rice cultivars.

3.3. Impacts of Climate Change on Rice Phenology

Figure 4 showed the simulation results of rice flowering duration at six stations in Hainan Province. Figure 4a,c,e represented the ensemble average of flowering duration of early rice, which was advanced by 3.2 to 13.2 days under SSP1-2.6, and accelerated by 2.5 to 22.8 days under SSP3-7.0, and advanced by 2.6 to 27.3 days under SSP5-8.5. Figure 4b,d,f illustrated the flowering duration for late rice. It was evident that there was significant variation in flowering duration between stations. The flowering duration varied by −3.7 to 1.6 days under SSP1-2.6, and varied by −6.6 to 6.6 days under SSP3-7.0, and varied by −7.0 to 9.5 days under SSP5-8.5. In addition, Figure 4b,d,f showed that the Ledong station was delayed by 1.6, 6.6, and 9.5 days and the Qionghai station was advanced by 3.7, 6.6, and 7.0 days under three SSPs, respectively. These two stations exhibited the most pronounced differences in the changes of late rice flowering duration compared to all other stations.

Figure 4.

Change in flowering durations in the 2050s, 2070s and 2090s under SSP1-2.6 (a,b), SSP3-7.0 (c,d) and SSP5-8.5 (e,f) compared to the baseline.

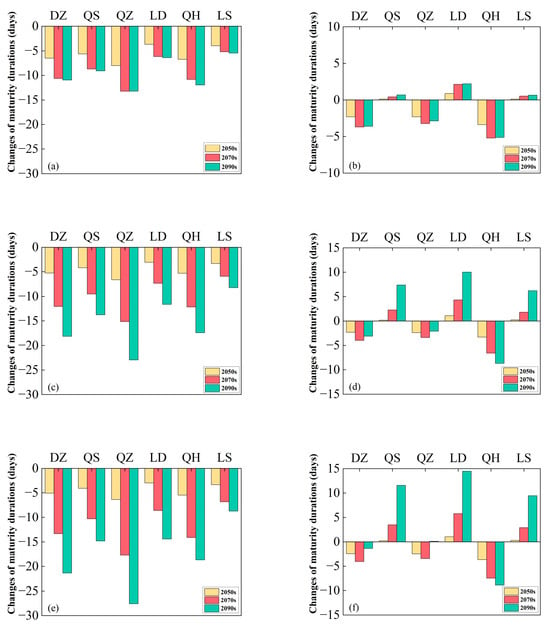

Figure 5 showed the simulation results of rice maturity duration at six stations in Hainan Province. Figure 5a,c,e represented the ensemble average of maturity duration of early rice, which was advanced by 3.6 to 13.2 days under SSP1-2.6, by 3.0 to 23.0 days under SSP3-7.0, and by 3.0 to 27.6 days under SSP5-8.5. Figure 5b,d,f represented the ensemble average of maturity duration of late rice, which was changed by −5.2 to 2.2 days under SSP1-2.6, by −8.7 to 10.0 days under SSP3-7.0, and by −8.9 to 14.5 days under SSP5-8.5. In addition, it can also be obtained from Figure 5b,d,f that the Ledong and Qionghai stations also showed the most significant contrast in changes of late rice maturity duration among all the stations.

Figure 5.

Change in maturity durations in the 2050s (2041–2060), 2070s (2061–2080) and 2090s (2081–2100) under SSP1-2.6 (a,b), SSP3-7.0 (c,d), and SSP5-8.5 (e,f) compared with the baseline.

3.4. Future Climate Change Impacts on Rice Yields

Figure 6 showed the changes of yield for three future periods relative to the baseline (1981–2018) under three SSPs, neglecting the effects of CO2 fertilization. All of these changes showed a significant downward trend in yield, except for SSP1-2.6, which showed a smaller reduction in yield of early rice. Figure 6a,c,e illustrated the ensemble average of yield of early rice, under three SSPs. The ensemble average of yield of early rice was changed by −7.2% to 3.7% under SSP1-2.6, with an increase of 1.2% to 3.7% at Qiongzhong, Ledong, Qionghai, and Lingshui stations, with a decrease which varied from 7.1% to 33.9% under SSP3-7.0, and a decrease which varied from 2.7% to 42.0% under SSP5-8.5. Figure 6b,d,f represented the ensemble average of yield of late rice, which decreased by 3.1% to 25.1% under the SSP1-2.6, 5.0% to 66.9% under SSP3-7.0, and 5.1% to 74.8% under SSP5-8.5. In conclusion, the reduction in rice yields under three SSPs increased in a sequential manner, with the greatest reduction occurring at Qiongshan station.

Figure 6.

Change in yields in the 2050s, 2070s and 2090s under SSP1-2.6 (a,b), SSP3-7.0 (c,d), and SSP5-8.5 (e,f) compared with the baseline.

3.5. Impacts of CO2 Fertilization Effect on Rice Yield

Figure 7 showed the simulation results for the rice yield with the CO2 fertilization effect considered at each station. For the early rice cultivars (a, c, e), the ensemble average of rice yield in the 2090s increased from 6.5% to 18.1%, 20.3% to 60.0%, and 27.0% to 79.5% under the SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively. For the late rice cultivars (b, d, f), the ensemble average of yield in the 2090s increased from 6.3% to 7.5%, 18.1% to 22.9%, and 19.7% to 30.0% under SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively. For Danzhou, Qiongzhong, Ledong, Qionghai and Lingshui stations, the CO2 fertilization effect was found to be capable of completely offsetting the negative impacts. Therefore, under future scenarios, the CO2 fertilization effects could be reduced.

Figure 7.

Change in yield in the 2090s under SSP1-2.6 (a,b), SSP3-7.0 (c,d), and SSP5-8.5 (e,f) compared with the baseline, without (green) and with (yellow) CO2 fertilization effects.

3.6. Simulation of Adaptation Measures

As illustrated in Table 3 and Figure 6, the early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 and the late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 reduced most at the Qiongshan station under future scenario, with 42% and 74.8%, respectively. Therefore, these two rice cultivars were selected for further analysis in this study. The objective of this conduction is to assess the effectiveness of adaptive measures of adjusting planting dates and switching rice cultivars under the 2090s.

Planting-date sensitivity was evaluated by systematically shifting the sowing window ±30 days in 5-day increments. As illustrated in Figure 8, the rice yield showed a non-linear relationship under the 2090s. The details changes were as follows: when the planting date was advanced by 30 days, the ensemble average of yield of early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 at the Qiongshan station reached maximum, increasing by 11.4%, 21.2%, and 35.4% under the three SSPs, during the 2090s, respectively. For the late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 at Qiongshan station, the ensemble average of yield reached maximum when planting date was delayed by 30 days. This yield increased by 4.6%, 22.7%, and 33.3% under three different scenarios, respectively.

Figure 8.

Change in rice yields of Tezhanxian25 (red) and BoIIyou15 (green) cultivars in the 2090s (2081–2100) under SSP1-2.6 (a), SSP3-7.0 (b), and SSP5-8.5 (c) at Qiongshan station. The numbers in the x-axis represent earlier and later days compared with current normal planting dates. The dots indicated the average value of the multi-model results.

As shown in Figure 9, the rice yield showed a significant increasing trend in the 2090s. The detailed changes were as follows: switching from the early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 at Qiongshan station to cultivar IIyou128 at Danzhou station would increase the ensemble average of rice yield by 29.3%, 43.6%, and 57.0% under SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively.

Figure 9.

The simulated yields of No. 1 and 7 cultivars during the 2090s under SSP1-2.6 (a), SSP3-7.0 (b), and SSP5-8.5 (c) with current rice cultivar (green) and replaced one (red). The numbers in x-axis represented the rice cultivars. The dots indicated the average value of simulated rice yields.

Replacing the BoIIyou15 (Qiongshan station) with Boyou225 (Lingshui station) would increase yield by 38.6% and 64.0% under the SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5, respectively. The ensemble average of yield remained essentially unchanged under SSP1-2.6. This indicated that switching rice cultivars can effectively increase rice yield to some extent, facing the potential challenge from climate change.

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate Change Impact Analysis

As illustrated in Figure 3, the model validation of the CERES-Rice model indicated that NRMSE was below 10%, demonstrating the model performed well with high accuracy. This was comparable in comparison with previous findings of Xu, of which the error of simulated flowering, maturity, and yields were 13.3%, 11.4%, and 15.3%, respectively [48]. Consequently, the model calibration presented in this study was more closely aligned with the actual observations of rice growth.

With regards to change in rice phenology, the ensemble average of flowering and maturity durations were advanced by an average of 9.60 and 9.90 days for early rice, respectively. Regarding late rice cultivars, the flowering duration was delayed by an average of 0.1 days and the maturity duration was projected to advance by an average of 0.2 days. Our findings were in agreement with the results reported by Bai, which showed that for single rice, the flowering duration was delayed by 0.3 days per 10a−1, and the maturity duration was delayed by 1.4 days per 10a−1 [49]. For double-rice, the flowering duration was advanced by 0.7–0.8 days per 10a−1, and the maturity duration was advanced by 0.2–1.1 days per 10a−1.

In this study, the average projected changes in flowering duration for late rice were delays and advances of 3.2 and 4.3 days at Ledong and Qionghai stations, respectively. Meanwhile, the average projected changes in maturity duration for late rice were delayed and advanced by 4.7 and 5.8 days, respectively. The phenological differences between these two stations were significant. Therefore, among the five general circulation models, we selected the UKESM1-0-LL model, which exhibited the most pronounced differences in simulated phenological results in the 2090s under the SSP1-2.6 scenario. The relationship between changes in rice phenology and climate factors was ultimately clarified by calculating the monthly average maximum and minimum temperatures during the rice-growing season at the six stations.

As illustrated in Figure 10, significant differences in monthly average maximum and minimum temperatures were observed among most stations. For example, the Qiongshan station exhibited higher average monthly maximum and minimum temperatures compared with that of Qiongzhong station, yet the phenological changes showed an opposite trend. This apparent discrepancy suggested that climate change significantly impacted rice phenology. To describe this phenomenon, the CERES-Rice model introduced the concept of GDD and divided the rice growth duration into different stages, such as flowering duration and maturity duration. When temperature increases, the heightened high-temperature stress speeds up the accumulation of Growing Degree Days (GDD), which subsequently results in alterations to the phenological stages of rice, most notably during the flowering and maturity periods.

Figure 10.

Monthly mean maximum temperature (a) and minimum temperature (b) in UKESM1-0-LL climate model in the 2090s under SSP1-2.6.

When not considering the CO2 fertilization, rice yield under the future scenario was projected to be reduced by an average of 12.5% and 23.9% for early and late rice, respectively. The findings of this study were also consistent with the finding of Osborne, who demonstrated that, in the absence of CO2 fertilization, rice yields would decrease by 9.7% in the 2020s, 1.5% in the 2050s, and 20.9% in the 2080s under Scenario A2 [50]. The results indicated that six stations in Hainan Province exhibited a significant decline in the ensemble average yield under three SSPs.

Among these, the Qiongshan station recorded the most significant yield reduction under SSP5-8.5 with the IPSL-CM6A-LR model simulating the most severe decline among the five general circulation models. Among the five general circulation models, the rice yield simulated by the IPSL-CM6A-LR model exhibited the most substantial decline.

The IPSL-CM6A-LR model data from 1981 to 2100 at Qiongshan station under the SSP5-8.5 scenario were employed as a case study to analyze the impact of climate factors (daily average temperature, daily average precipitation, and daily average solar radiation) on rice yields using the stepwise regression method.

For early rice cultivar,

For late rice cultivar,

Tavg represented the daily average temperature, P represented the significance level, and the variable r represented the correlation coefficient.

Equations (5) and (6) indicated that the daily average temperature was negatively correlated with the rice yield. Furthermore, an increase in temperature was associated with a significant decrease in rice yield. In summary, the impacts of rising temperature on rice yields can be attributed to two primary mechanisms: Firstly, elevated temperatures tend to shorten the rice growth cycle, particularly during the flowering and grain-filling stages. When the daily average temperature surpasses 35 °C, the flowering phase is negatively affected [51]. This impacts the activity of pollen and the efficiency of pollination, thereby reducing fertilization rates and seed formation. Secondly, during the grain-filling stage, when temperatures exceed 35 °C, the distribution and translocation of assimilates are disrupted, resulting in inadequate seed filling and accelerated maturation. Consequently, this diminishes the grain weight and overall yield. Altogether, the detrimental impacts of elevated temperatures on both the reproductive and ripening stages play a substantial role in reducing rice yields.

When the CO2 fertilization effect was considered, the ensemble average of yield was projected to be increased by an average of 29.4% and 17.7% under future scenarios for early and late rice, respectively. The findings of this study aligned with those of Zhang, who found that when considering the impact of CO2 fertilization, the yield of double-cropped rice would increase by 2.6%, 1.8%, −2.0%, and 0.1% under three SSPs [52]. This was due to the fact that elevated CO2 levels can stimulate photosynthesis by providing more CO2 for the key enzyme involved in fixation. This would increase the rate of CO2, and the general amount of organic compounds produced by photosynthesis increases. Additionally, elevated CO2 concentrations led to a reduction in stomatal conductance, which in turn enhanced Water Use Efficiency (WUE) in C3 plants while also facilitating greater CO2 uptake. Enhancing WUE is especially advantageous for rice cultivation, given that rice is often grown in environments with limited water availability.

4.2. Effectiveness of Adaptative Measures

The results indicated that advance and delay of the planting date by 30 days for early and late rice was an effective method to increase rice yields. The ensemble average of yield of early and late rice were projected to increase by an average of 22.7% and 20.2%, respectively. Lv et al. demonstrated that optimizing the planting date was predicted to increase 3%, 7%, and 11% for single-season rice yield for the 2030s, 2050s and 2070s in central China, respectively [53]. Yoon and Choi demonstrated that the optimal planting date of Korean rice could be delayed by 30 and 55 days, resulting in an increase of 8% and 6–13% for rice yield under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, respectively [54].

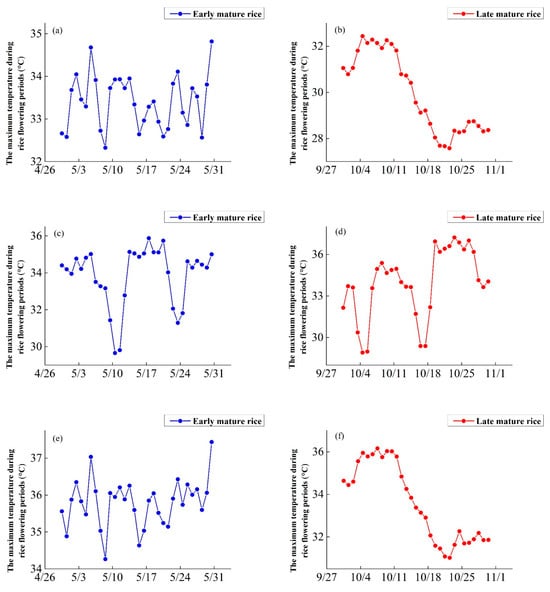

The rice flowering period was sensitive to high temperature stress. Before the adjustment, the flowering dates of the early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 and the late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 at Qiongshan station were 14 May and 2 October, respectively. For early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 at Qiongshan station, the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period were 33.9 °C, 35.1 °C, and 36.3 °C under three SSPs, respectively. For late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 at Qiongshan station, the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period under three scenarios were 30.8 °C, 33.8 °C, and 34.4 °C, respectively. When the planting date was advanced by 30 days, the flowering dates of early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 and the late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 at the Qiongshan station were 30 April and 19 October, respectively. For early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25, the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period were 32.7 °C, 34.4 °C, and 35.6 °C under three SSPs, respectively. For late rice cultivar BoIIyou15, the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period under the three scenarios were 28.6 °C, 32.2 °C, and 32.1 °C, respectively (Figure 11). In summary, the maximum temperatures during the rice flowering period were all significantly reduced following the adjustment of the planting date. Therefore, adjusting the planting date of rice would improve rice yields by reducing the adverse effects of high-temperature stress during the crucial growth stage, as well as by altering the total amount and distribution of rainfall and solar radiation.

Figure 11.

Changes of the ensemble average of the maximum temperature during flowering periods in the 2090s (2081–2100) under SSP1-2.6 (a,b), SSP3-7.0 (c,d), and SSP5-8.5 (e,f), respectively.

Moreover, replacing with rice cultivars that have greater tolerance to high temperatures would increase rice yields. This was evidenced by an average increase of 43.3% and 34.2% in ensemble average of yield for early and late rice under future scenarios, respectively. Our findings supported previous findings, where Li et al. found that the early rice yields increased by 16.8% and 16.5 at the Wugang station, middle rice yields by 19.6% and 13.2% at the Huaihua station, and late rice yields by 11.8% and 25.1% at the Changde station by switching rice cultivars under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, respectively [55]. Guo et al. [31] demonstrated that switching to more heat-tolerant rice cultivars resulted in an improvement of 14.57% and 19.1% at the Shaoxing and Pingyang stations.

As illustrated in Table 4 and Table 5, switching from the early rice cultivar Tezhanxian25 at the Qiongshan station to the early rice cultivarIIyou128 at the Danzhou station would decrease the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period: decreased by 0.3 °C, 0.2 °C, and 0.7 °C under three SSPs. Switching from the late rice cultivar BoIIyou15 at Qiongshan station to the late rice cultivar Boyou225 at Lingshui station would decrease the ensemble average of the maximum temperatures during the flowering period: decreased by 0.1 °C, 0.8 °C, and 0.4 °C under the three scenarios, respectively. A possible reason explaining such increases in rice yield is that switching cultivarsIIyou128 and Boyou225 rice cultivars with a shorter growing season can reduce high temperature stress and increase dry matter accumulation by making full use of heat resources.

Table 4.

Changes in ensemble average of the maximum temperature during flowering of early rice.

Table 5.

Changes in ensemble average of the maximum temperature during flowering of late rice.

4.3. Uncertainty and Prospective

Consistent with prior model-based climate-impact appraisals, the present study is constrained by several epistemic and parametric uncertainties that propagate through the simulation chain. The main sources of uncertainty are threefold. Firstly, the limited number of agro-meteorological stations increases the uncertainty in the simulation results, even though we have used high-precision national-level agro-meteorological station data. Secondly, although coupling five general circulation models with the CERES-Rice model under three SSPs significantly reduced the uncertainty related to climate change, the use of a single crop model remains a significant contributor to the uncertainty in the study’s results. Lastly, the simplifications and limitations of the CERES-Rice model, such as its less-than-ideal simulation of pests and diseases, soil properties, and extreme weather patterns, constitute another source of uncertainty in the model simulations. In the future, multi-models with various climatic data can be integrated, and the ensemble of model simulation could better explain and predict the impacts of climate change on rice growth and rice yield.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the CERES-Rice model was calibrated using high-quality data from six agro-meteorological sites in Hainan and subsequently evaluated with an independent 20% hold-out dataset (RMSE ≤ 6% for anthesis, ≤9% for yield). The configured model was then applied to explore plausible shifts in rice phenology and yield in the 2050s (2041–2060), 2070s (2061–2080) and 2090s (2081–2100) relative to the 1981~2018 (baseline) under three SSPs. The results showed that high temperature stress affected the growth of rice, causing the reduction of rice yield. For early rice, the flowering was advanced by 7.80, 9.70, and 11.10 days, and the maturity was advanced by 8.10, 10.10, and 11.30 days. This was accompanied by a reduction of yield by 2.5%, 18.5%, and 16.6% under three SSPs. For late rice, the flowering was advanced by 0.70, 0.20, and 0.80 days, and the maturity was advanced by −1.30, −0.10, and 0.90 days, with the yield reduced by 12.60%, 27.90%, and 31.30% under three SSPs. The integration of crop models with machine learning algorithms and their assimilation with remote sensing models is essential and could be applied to reduce the model uncertainty. This approach will enable the provision of a more holistic and detailed analysis of agricultural systems for decision-makers.

Author Contributions

Y.G., R.Y. and W.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization; J.N., R.M., W.M.W.W.K. and J.S.: Investigation, Software, Data Curation, Visualization; W.Z., B.Y. and J.G.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing; J.L. and M.C.: Validation, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42271317) and the Innovation Research Team Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (Grant No. 422CXTD515), the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2024AFB321), the Open Funding of State Environmental Protection Key Laboratory of Monitoring for Heavy Metal Pollutants (Grant No. KLMHM202423).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed information about the five GCMs used in this study.

Table A1.

Detailed information about the five GCMs used in this study.

| Model | Research Institution | Resolution Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| GFDL-ESM4 | Geophy Fluid Dynamics Laboratory | 288 × 180 |

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | Institute Pierre-Simon Laplace | 144 × 143 |

| MPI-ESM1-2-HR | Max Planck Institute for Meteorology | 384 × 192 |

| MRI-ESM2-0 | Meteorologocal Research Institute, Japan Meteorologocal Agency | 320 × 160 |

| UKESM1-0-LL | National Centre for Atmospheric Science, and Met Office Hadley Center | 192 × 144 |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Changes in ensemble mean of monthly average maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation and solar radiation from March to October during 2041–2100 under SSP1-2.6 (a,d,g,j), SSP3-7.0 (b,e,h,k) and SSP5-8.5 (c,f,i,l) relative to the baseline.

References

- Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Hao, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, L. Recently amplified arctic warming has contributed to a continual global warming trend. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Schlenker, W.; Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 2011, 333, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.T.; Yao, Y.T.; Bassu, S.; Ciais, P.; et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, Y. China’s food security challenge: Effects of food habit changes on requirements for arable land and water. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Wu, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Z. Arable land and water footprints for food consumption in China: From the perspective of urban and rural dietary change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ge, Q. Spatiotemporal changes of rice phenology in China under climate change from 1981 to 2010. Clim. Change 2019, 157, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tao, F. Modeling the response of rice phenology to climate change and variability in different climatic zones: Comparisons of five models. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 45, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Su, P.; Wang, J.A. Global spatial distributions of and trends in rice exposure to high temperature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kumar, A.; Barman, M.; Pal, S.; Bandopadhyay, P. Impact of climate variability on phenology of rice. In Agronomic Crops: Volume 3: Stress Responses and Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suepa, T.; Qi, J.; Lawawirojwong, S.; Messina, J.P. Understanding spatio-temporal variation of vegetation phenology and rainfall seasonality in the monsoon Southeast Asia. Environ. Res. 2016, 147, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizumi, T.; Yokozawa, M.; Nishimori, M. Parameter estimation and uncertainty analysis of a large-scale crop model for paddy rice: Application of a Bayesian approach. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2009, 149, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.D.A. Sampling designs, field techniques and analytical methods for systematic plant population surveys. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2000, 1, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCravy, K.W. A review of sampling and monitoring methods for beneficial arthropods in agroecosystems. Insects 2018, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.A.R.; Alam, K.; Gow, J. Exploring the relationship between climate change and rice yield in Bangladesh: An analysis of time series data. Agric. Syst. 2012, 112, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.; El-Hendawy, S.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Tahir, M.U.; Mubushar, M.; dos Santos Vianna, M.; Ullah, H.; Mansour, E.; Datta, A. Sensitivity of the DSSAT model in simulating maize yield and soil carbon dynamics in arid Mediterranean climate: Effect of soil, genotype and crop management. Field Crops Res. 2021, 260, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bryant, C.R.; Fu, Y. Impacts of climate and phenology on the yields of early mature rice in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquel, D.; Cammarano, D.; Roux, S.; Castrignanò, A.; Tisseyre, B.; Rinaldi, M.; Troccoli, A.; Taylor, J.A. Downscaling the APSIM crop model for simulation at the within-field scale. Agric. Syst. 2023, 212, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darikandeh, D.; Shahnazari, A.; Khoshravesh, M.; Yousefian, M.; Porter, C.H.; Hoogenboom, G. Optimizing rice management to reduce methane emissions and maintain yield with the CSM-CERES-rice model. Agric. Syst. 2025, 224, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, W.; Bryant, C.R. Quantifying spatio-temporal patterns of rice yield gaps in double-cropping systems: A case study in pearl river delta, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Ines, A.V.; Han, E.; Cruz, R.; Prasad, P.V. A comparison of multiple calibration and ensembling methods for estimating genetic coefficients of CERES-Rice to simulate phenology and yields. Field Crops Res. 2022, 284, 108560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesino-San Martín, M.; Olesen, J.E.; Porter, J.R. A genotype, environment and management (GxExM) analysis of adaptation in winter wheat to climate change in Denmark. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 187, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhou, Y. Urbanization effect on trends of extreme temperature indices of national stations over mainland China, 1961–2008. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2340–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Fang, Q.; Ge, Q.; Zhou, M.; Lin, Y. CERES-Rice model-based simulations of climate change impacts on rice yields and efficacy of adaptive options in Northeast China. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Xu, Y.; Lin, E.; Yokozawa, M.; Zhang, J. Assessing the impacts of climate change on rice yields in the main rice areas of China. Clim. Change 2007, 80, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Miao, Y.; Batchelor, W.D.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Kang, S. Improving high-latitude rice nitrogen management with the CERES-rice crop model. Agronomy 2018, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, L.A. Assessing the impacts of climate change on aerobic rice production using the DSSAT-CERES-Rice model. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 12, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Lin, Y.P.; Lur, H.S. Evaluating and adapting climate change impacts on rice production in Indonesia: A case study of the Keduang subwatershed, Central Java. Environments 2021, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib-Ur-Rahman, M.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, A.; Hasnain, M.U.; Alharby, H.F.; Alzahrani, Y.M.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Hakeem, K.R.; Ahmad, S.; Nasim, W.; et al. Impact of climate change on agricultural production; Issues, challenges, and opportunities in Asia. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 925548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawat, A.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, A.; Dubey, S.K. Assessment of climate change impact and potential adaptation measures on wheat yield using the DSSAT model in the semi-arid environment. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 2077–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeshna, T.R.; Athira, P.; Soundharajan, B. Impact of climate change on regional water availability and demand for agricultural production: Application of water footprint concept. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 3785–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, W.; Du, M.; Bryant, C.R.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H. Assessing potential climate change impacts and adaptive measures on rice yields: The case of zhejiang province in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, F. Single rice growth period was prolonged by cultivars shifts, but yield was damaged by climate change during 1981–2009 in China, and late rice was just opposite. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, W.; Ge, Q. Impact assessment of climate change on rice yields using the ORYZA model in the Sichuan Basin, China. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 2922–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsina, J.; Humphreys, E. Performance of CERES-Rice and CERES-Wheat models in rice–wheat systems: A review. Agric. Syst. 2006, 90, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beusen, A.; Doelman, J.; Van Beek, L.; Van Puijenbroek, P.; Mogollón, J.; Van Grinsven, H.; Stehfest, E.; Van Vuuren, D.; Bouwman, A. Exploring river nitrogen and phosphorus loading and export to global coastal waters in the Shared Socio-economic pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 72, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, F. Global gridded GDP data set consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, J.P.; Horowitz, L.W.; Adcroft, A.J.; Ginoux, P.; Held, I.M.; John, J.G.; Krasting, J.P.; Malyshev, S.; Naik, V.; Paulot, F.; et al. The GFDL Earth System Model version 4.1 (GFDL-ESM 4.1): Overall coupled model description and simulation characteristics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS002015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurton, T.; Balkanski, Y.; Bastrikov, V.; Bekki, S.; Bopp, L.; Braconnot, P.; Brockmann, P.; Cadule, P.; Contoux, C.; Cozic, A.; et al. Implementation of the CMIP6 forcing data in the IPSL-CM6A-LR model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS001940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.A.; Jungclaus, J.H.; Mauritsen, T.; Baehr, J.; Bittner, M.; Budich, R.; Bunzel, F.; Esch, M.; Ghosh, R.; Haak, H.; et al. A higher-resolution version of the max planck institute earth system model (MPI-ESM1. 2-HR). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2018, 10, 1383–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukimoto, S.; Kawai, H.; Koshiro, T.; Oshima, N.; Yoshida, K.; Urakawa, S.; Tsujino, H.; Deushi, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hosaka, M.; et al. The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: Description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2019, 97, 931–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Rumbold, S.; Ellis, R.; Kelley, D.; Mulcahy, J.; Sellar, A.; Walton, J.; Jones, C. MOHC UKESM1.0-LL Model Output Prepared for CMIP6 CMIP Historical. 2019. Available online: https://ipcc-browser.ipcc-data.org/browser/dataset/6974/0 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T. Improving simulations of extreme precipitation events in China by the CMIP6 global climate models through statistical downscaling. Atmos. Res. 2024, 303, 107344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.B.; Stuart, S.; Sood, A.; Stone, D.; Rampal, N.; Lewis, H.; Broadbent, A.; Thatcher, M.; Morgenstern, O. Dynamical downscaling CMIP6 models over New Zealand: Added value of climatology and extremes. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 8255–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.; Syktus, J.; Trancoso, R.; Chapman, S.; Wasko, C.; Evans, J.P.; Thatcher, M.; Di Virgilio, G.; Stassen, C. Substantial increases in future precipitation extremes—Insights from a large ensemble of downscaled CMIP6 models. npj Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, J.-L.; Song, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, A.-X.; Zhang, G.-L. Mapping high resolution national soil information grids of China. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Yu, W.; Feng, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Identification and characteristics of combined agrometeorological disasters caused by low temperature in a rice growing region in Liaoning Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L. Response of rice yield traits to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration and its interaction with cultivar, nitrogen application rate and temperature: A meta-analysis of 20 years FACE studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-C.; Wu, W.-X.; Ge, Q.-S.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Y.-M.; Li, Y.-M. Simulating climate change impacts and potential adaptations on rice yields in the Sichuan Basin, China. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2017, 22, 565–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, H.; Tao, F.; Hu, Y. Impact of warming climate, sowing date, and cultivar shift on rice phenology across China during 1981–2010. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, T.; Rose, G.; Wheeler, T. Variation in the global-scale impacts of climate change on crop productivity due to climate model uncertainty and adaptation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 170, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Mahat, J.; Shrestha, J.; KC, M.; Paudel, K. Influence of high-temperature stress on rice growth and development. A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Niu, B.; Liu, D.L.; He, J.; Pulatov, B.; Hassan, I.; Meng, Q. Impact of climate change and planting date shifts on growth and yields of double cropping rice in southeastern China in future. Agric. Syst. 2023, 205, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ye, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, F. Climate change impacts on regional rice production in China. Clim. Change 2018, 147, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, P.R.; Choi, J.-Y. Effects of shift in growing season due to climate change on rice yield and crop water requirements. Paddy Water Environ. 2020, 18, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Ge, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, C. Simulating climate change impacts and adaptive measures for rice cultivation in Hunan province, China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2016, 55, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.