Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the impact of integrating the Social, Ecological, Technological Systems (SETS) keyword coding—which categorizes sustainability themes into social, ecological, and technological dimensions—into seafood consumption education programs. In this study, the SETS framework is utilized to conduct an analysis of the educational environment around the consumption of seafood in South Korea. Through the utilization of focus group interviews with industry professionals, the research reveals that the current educational framework on the consumption of seafood and dietary education has a substantial gap in its coverage. The study indicates a predominant focus on the social aspects (56.46%) of seafood consumption education among stakeholders, succeeded by the technological (28.26%) and ecological dimensions (15.28%). To enhance seafood dietary education, the study proposes two primary avenues: developing comprehensive seafood dietary education programs for diverse age demographics and establishing a training system for specialized professionals in seafood dietary education. Future research should refine the SETS approach and explore its broader application across food systems to further promote sustainable consumption.

1. Introduction

The importance of blue food in the development of sustainable international food supply networks has lately been brought to the attention of the international community. Fortune [1] released an article highlighting the significance of blue food and the necessity to re-evaluate sustainability. In June 2022, the second UN Ocean Conference officially inaugurated The Aquatic Blue Food Coalition, comprising prominent fishing states globally [2]. In research published in Nature, Golden et al. [3] analyzed the nutrient composition of 3753 aquatic species, assessing the nutritional value across seven categories, including shellfish, mollusks, and salmonids. The research determined that the nutritious value of seafood surpasses that of beef, pork, and chicken.

Scholars recognize blue food’s nutritional benefits and comparatively low greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting its environmental significance. Research by Poore and Nemeck [4] indicates that the production of 1 kilogram (kg) of protein results in emissions of 45 to 640 kg for cows, 51 to 750 kg for sheep, 20 to 55 kg for pigs, and 10 to 30 kg for poultry. Conversely, seafood obtained from fishing generates around 2.2 kg of greenhouse emissions for every 1 kg of protein [5], whereas aquaculture fish create 3.3 kg per 1 kg [6]. The international community underscores the significance of blue food for sustainable food production, eliminating hunger and malnutrition, mitigating climate change, and preserving biodiversity. In this study, we provide new insights into sustainable seafood practices by examining newly addressed SETS frameworks into seafood consumption education. While seafood is known for its relatively lower CO2 emissions compared to other protein sources, our research delves deeper into the unique aspect of addressing gaps in seafood consumption encourages policymaking. For instance, our analysis highlights how sustainable management in aquaculture can streamline production while mitigating environmental impact. These contributions not only affirm the environmental benefits of sustainable seafood but also expand the sustainability discourse by providing actionable strategies applicable across diverse contexts.

The Republic of Korea, bordered by the sea on three sides, has a longstanding tradition of high seafood consumption. According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [7] food balances, Korea’s per capita seafood supply in 2021 was 55.27 kg annually, one of the highest globally, surpassing Norway’s 50.18 kg, Japan’s 46.20 kg, and China’s 39.91 kg. As per Korea’s 2021 Food Supply Table report [8], the annual per capita net food supply by food category is 68.4 kg for seafood, encompassing fish and seaweed, surpassing 66.9 kg for rice, 66.2 kg for meat, and 38.3 kg for fruits, establishing its significance in the context of food supply. The yearly per capita net seafood supply increased from 36.7 kg in 2000 to 51.2 kg in 2010, reaching 68.4 kg in 2021. Seafood is crucial for nutritional provision among Koreans. It provides 19% of the daily protein intake per individual (30% from animal sources) and is a primary source of calcium, alongside milk. However, despite the significant role of seafood in the Korean diet, there is a notable deficiency in dietary education about sustainable seafood intake.

The Third Basic Plan for Dietary Education (2020–2024) [9] emphasizes promoting sustainable eating practices grounded in environmental stewardship, health, and mindfulness and outlines four tactics along with twelve goals aligned with the agricultural policy agenda. The seafood-related content in this strategy predominantly comprises event-oriented and ancillary elements, including seafood experience events, the management of Seafood Day, and the creation of seafood recipes. There is a gap between the understanding of education advocating for seafood consumption based on life cycle assessment and implementing sustainable dietary practices. The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs [9] and its affiliated organizations primarily oversee Korea’s regulation of dietary education, but the result is a significant deficiency in discussions around seafood, coupled with inadequate policy support from the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries.

South Korea’s substantial seafood consumption presents a unique opportunity to advance sustainability through targeted seafood education. By fostering consumer understanding of sustainable production methods, responsible sourcing, and waste reduction, seafood education can drive meaningful behavioral changes. These changes not only contribute to the environmental preservation of marine ecosystems but also support the long-term resilience of the seafood industry. Moreover, educating consumers on the broader implications of their choices enhances the integration of sustainability principles into everyday practices, thereby reinforcing systemic efforts to align South Korea’s consumption patterns with global sustainability goals.

Scholars expect the growing trend of seafood consumption avoidance among adolescents and the lack of seafood dietary education to impact future seafood consumption patterns. A survey by the Korea Maritime Institute (KMI) [10] on seafood consumption behavior among teenagers indicates that students acknowledge the nutritional value and importance of seafood; however, they refrain from consuming it due to factors such as its distinctive odor, challenges in consumption (bones, small bones, internal organs), and the lack of students’ taste in school meals. Therefore, this study aims to offer policy initiatives for enhancing seafood dietary education to promote sustainable fisheries, increase seafood consumption, and develop a healthy, environmentally conscious food culture.

To achieve this, we first assess the performance state of seafood education inside the existing dietary education framework, alongside the necessity for seafood dietary education. Second, we administer an agenda-setting analysis with a seafood dietary literature review worldwide to ascertain the challenges associated with seafood dietary instruction. Third, we perform a comprehensive focus group interview with experts regarding the survey results of nutrition educators, followed by a keyword structuring analysis grounded in the principles of the social, ecological, and technological systems (SETS) framework to recommend initiatives for enhancing seafood dietary education. The SETS concept is an effective framework for integrating theoretical components into projects. We can classify the information from focus group interviews by keywords within each SETS category. The SETS framework is an effective positioning instrument for translating theoretical aspects into real initiatives. The objective is to solidify implementation programs and policy initiatives focused on seafood for governmental policy implementation.

2. Literature Review

Blue food, which includes all edible aquatic organisms like fish, shellfish, and algae, is vital for youth nutrition due to its abundant nutrient profile, featuring elevated levels of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals essential for growth and development [3,11]. Prior research indicates that blue food can mitigate malnutrition and is a sustainable protein supply, with fish comprising at least 20% of the total protein intake for 3.2 billion individuals worldwide [11,12]. Notwithstanding these advantages, current trends reveal a decrease in seafood consumption among youth, mostly attributed to the perceived difficulties of preparation and the strong smell associated with seafood [3,13]. The decline in blue food consumption is troubling since it might result in a deficiency of critical nutrients that other protein sources may not sufficiently provide. Mitigating these challenges by advocating for simplified cooking procedures and minimizing odor through advanced processing techniques may facilitate the reintegration of blue food into the diets of younger generations, therefore guaranteeing them to obtain its whole nutritional advantages [14,15].

The increasing focus on blue food, or aquatic food sources, among the global population is indisputable. Recent occurrences highlight this tendency, such as the United Nations (UN) Ocean Conference in 2022 and the establishment of The Aquatic Blue Food Coalition, a worldwide alliance of more than 20 nations committed to promoting sustainable aquatic food systems. The collaboration seeks to tackle issues like climate change, overfishing, and starvation by advocating for sustainable aquaculture and fisheries management techniques [2]. Studies have repeatedly shown that blue food possesses greater nutritional value than terrestrial meats. Golden et al. [3] extensively investigated 3753 aquatic animal species, demonstrating that several blue foods have higher levels of critical nutrients such as iron, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids than terrestrial alternatives. Research by Allison et al. [16] and Tlusty et al. [17] emphasized the capacity of blue foods to mitigate micronutrient deficiencies, especially among at-risk groups. These findings correspond with Fortune’s [3] endorsement of integrating blue food into sustainable food systems, highlighting its capacity to enhance global food security and nutrition.

Additionally, the Blue Food Assessment, an extensive analysis of aquatic food systems, released a series of publications by Allison et al. [16], emphasizing the diverse advantages of blue food. The work emphasized the significance of blue food in enhancing livelihoods, fostering biodiversity, and alleviating climate change. Hilborn et al.’s evaluation indicated that blue food produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions than terrestrial animal production, rendering it a more sustainable alternative for satisfying the increasing world protein demand.

Furthermore, Gephart et al. [18] indicated that altering eating patterns to incorporate blue food might markedly diminish the environmental repercussions of food production, especially regarding land utilization and freshwater usage. This change may benefit human health since scholars have linked the intake of blue food to a decreased risk of chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [19]. The scientific evidence endorsing the importance of blue food in global sustainability is substantial and diverse. Researchers widely acknowledge blue food as an essential element of sustainable food systems due to its superior nutritional profile, environmental advantages, and ability to tackle food security and public health issues. As recent events and research endeavors have demonstrated, the increasing focus on blue food in the global society indicates a hopeful transition toward a more sustainable and equitable food future.

In addition to its remarkable nutritional content, the scientific community and international policy forums are highly acknowledging blue food’s environmental benefits. Seminal research by Poore and Nemecek [4] highlighted the significant disparity in greenhouse gas emissions between seafood and livestock production. Their study indicated that one kilogram of beef protein produced emissions up to 100 times higher than those of specific fish species. This significant disparity highlighted the capacity of blue food to alleviate the environmental consequences of food production, especially regarding climate change. Parker et al. [5] conducted a thorough meta-analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from wild-caught fisheries, further substantiating these findings. Their study examined over 1000 fisheries worldwide and verified that wild-caught seafood often had a lower carbon footprint than most livestock products. Small pelagic fish, such as anchovies and sardines, are the most environmentally sustainable choices, exhibiting much reduced greenhouse gas emissions compared to larger predatory fish.

Clarke et al. [20] comprehensively analyzed life cycle assessments for different farmed fish species in aquaculture. The study showed that aquaculture’s carbon footprint varies significantly based on species and production techniques. Nevertheless, they discovered that several farmed fish, including tilapia and pangasius, exhibit reduced greenhouse gas emissions compared to terrestrial animals such as beef and pork. However, it is essential to recognize that certain intensive aquaculture operations, especially those using carnivorous fish, may exert greater environmental consequences due to the issues associated with feed production and waste management [16]. The cumulative data from this research underscore the vital contribution of blue food in alleviating climate change and fostering sustainable food production [21,22]. Altering eating habits to incorporate blue food can substantially diminish carbon footprints and foster a more sustainable future [23]. It is crucial to recognize that the environmental effect of blue food production varies and that sustainable techniques in wild-caught fisheries and aquaculture are vital for optimizing the environmental advantages of this important food source [24].

The connection between Korea and seafood embodies a distinctive contradiction. Despite FAO [7] data continuously positioning Korea among the greatest per capita seafood eaters worldwide, a further analysis uncovers a troubling trend: a notable deficiency in thorough nutritional instruction for this vital food category.

This disparity is especially notable considering seafood’s cultural relevance and nutritional value in the Korean diet. The 2021 Food Supply Table, a comprehensive assessment of food consumption trends in Korea, highlights the preeminence of seafood in the Korean diet. The research indicates that the average Korean annually consumes more fish than grains (rice), meat, and fruits, underscoring the significance of seafood in fulfilling nutritional requirements and cultural inclinations [25]. Nonetheless, despite its significance, the dietary education initiatives of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, including “The Third Basic Plan for Dietary Education (2020–2024)”, inadequately encompass sustainable seafood intake [9]. This exclusion is especially troubling in light of the increasing worldwide focus on sustainable food systems and the distinct issues confronting Korean fisheries.

National statistics from South Korea (Republic of Korea) reveal a noticeable decline in seafood consumption among younger demographics over the past decade. Peer-reviewed studies, such as Lee and Baek [26], attribute this trend to factors including changing dietary preferences, increased accessibility to alternative protein sources, and limited knowledge of seafood’s nutritional and sustainability benefits [27]. Addressing this shift through targeted educational campaigns could help reverse this trend and promote sustainable consumption patterns.

An increasing antipathy to seafood among Korean adolescents exacerbates the deficiency in extensive seafood knowledge. As mentioned before, a study by the KMI [10] revealed that although adolescents acknowledge the nutritional benefits and significance of seafood, they frequently eschew it due to factors such as the perceived pungent odor, challenges associated with managing bones and internal organs, and unappealing culinary preparations in school meals [10]. If neglected, this tendency may significantly impact the future of seafood consumption in Korea, potentially resulting in decreased demand and jeopardizing the viability of the fishing sector.

The lack of comprehensive seafood education in Korea is a wasted opportunity to foster healthy and sustainable eating practices and a possible risk to the long-term sustainability of the nation’s seafood sector. A comprehensive and multifaceted strategy is required to resolve this duality, including educational programs for consumers of all ages, enhancements in seafood processing and preparation techniques, and promoting sustainable fishing practices. By confronting these difficulties, Korea can guarantee that its abundant seafood history continues to be an integral component of its culinary culture and fosters a more sustainable and equitable food system. Ultimately, the importance of seafood in a balanced diet is well established, especially because of its high levels of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vital for cardiovascular and cognitive health [28]. Notwithstanding this, seafood intake remains inadequate in most areas, including Korea.

The Third Basic Plan for Dietary Education (2020–2024) emphasizes general dietary habits but offers limited focus on the integration of seafood sustainability education. Recent studies, such as Kang’s [29], highlight the importance of including specific modules on sustainable seafood practices within dietary education frameworks. Furthermore, reports from Nichifor et al. [28] suggest that incorporating sustainability-focused content in dietary plans can significantly enhance environmental awareness among consumers.

To sum up, seafood education is a vital driver of sustainability, as it inevitably leads to consumers who make informed choices about the products that are there to support and encourage sustainable practices. The use of scholarly works like Stephen et al. [30] and Prasanna et al. [31] illustrates that well-targeted educational outreach can reduce waste, stimulate sustainable sourcing, and empower better long-term resource management. Following this trail, our research brings forth a new blend of insights by showing the interdisciplinary nature of the relationship between behavioral science and sustainable seafood practices [32]. These novel contributions consequently further the field of seafood education’s possibilities and at the same time offer a holistic formula to solve the main hurdles of sustainable development in the seafood industry [33].

Thus, this literature review consolidates current research on seafood dietary education, pinpoints deficiencies, and suggests a complete framework for improving seafood education in Korea.

3. Diagnosis of the Current Educational Landscape

Despite the nutritional benefits of blue food, adolescents globally demonstrate strong preferences for fast food options, which poses a significant challenge to seafood dietary education efforts. Research shows that 30–40% of adolescents consume fast food at least once per week [34], while seafood consumption remains low among this demographic. This preference is driven by various factors including taste, convenience, peer influence, and aggressive marketing by fast food companies [35].

The effectiveness of dietary education programs in changing adolescent food preferences remains a complex challenge. Traditional nutrition education alone has shown limited success in changing established food preferences [36]. However, multicomponent interventions that combine education with hands-on experiences, environmental changes, and family involvement have demonstrated more promising results. Altintzoglou et al. [37] found that seafood educational interventions incorporating practical cooking experiences increased seafood acceptance among adolescents by approximately 25–30%. Similarly, Verhage et al. [38] reported significant improvements in attitudes toward seafood consumption when school-based interventions combined nutrition education with repeated taste exposure.

Nevertheless, the question of long-term effectiveness remains valid, as sustained behavior change requires addressing broader sociocultural and economic factors that influence food choices [39]. This underscores the need for comprehensive approaches that not only educate about the benefits of seafood but also address the systemic barriers to healthy food choices.

An extensive examination of current dietary education programs uncovers several benefits and problems. Lee et al. [26] studied curriculum, textbooks, and educational materials, discovering that although these sources reference seafood, they frequently do not prioritize or successfully include it in comprehensive nutritional education programs. Insufficient attention may lead to the underconsumption of seafood despite its acknowledged health advantages [26]. For instance, Kim and Lee [40] executed a countrywide survey of nutrition educators in Korea, examining their knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to seafood instruction. The survey identified many obstacles, such as insufficient training for educators and inadequate resources to facilitate successful seafood instruction. Educators also indicated facing cultural and financial obstacles that impede encouraging seafood eating among students [40].

Choi et al. [41] conducted focus group interviews with various professionals, including nutritionists, educators, policymakers, and industry representatives, to investigate the determinants of seafood consumption trends in Korea. The discussions highlighted intricate obstacles, including misunderstandings regarding seafood safety, elevated prices, and restricted availability in some places. The specialists underscored the necessity for focused educational initiatives and legislative measures to overcome these obstacles. Moreover, international research offers significant insights into the issues and possibilities of enhancing seafood consumption. For instance, Tlusty et al. [17] investigated the influence of food-based dietary recommendations (FBDGs) on seafood consumption in the United States, concluding that the mere inclusion in FBDGs does not inherently lead to heightened consumption. This finding highlights the necessity for more focused and efficient instructional practices. Further, Casillas et al. [42] examined the use of evidence-based dietary guidelines to enhance cardiovascular health, highlighting the need for culturally tailored dietary treatments. The researchers determined that this method may be advantageous in Korea, where cultural food preferences and customs markedly impact dietary patterns.

The ecological sustainability of seafood is an essential factor in nutritional education. For example, the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior [43] emphasized the necessity of including sustainability factors in dietary guidelines and indicated that sustainable seafood offers a substantial supply of nutrients while reducing environmental effects, rendering it a vital element of a sustainable diet.

The SETS paradigm provides a comprehensive method for analyzing and resolving the interrelated elements affecting seafood consumption. Ostrom [44] emphasized the significance of integrating social, ecological, and technical factors in the formation of food systems and habits of eating. Thus, the current study uses the SETS framework to pinpoint leverage areas for intervention and formulate policy suggestions that tackle the fundamental reasons for the existing seafood dietary education deficiency. It emphasizes the necessity for a thorough and varied strategy for seafood dietary education in Korea. Our research formulates actionable suggestions for the Korean government’s “Fourth Basic Plan for Dietary Education (2025–2029)” by assessing the educational environment, surveying nutrition educators, conducting expert interviews, and employing the SETS framework. These initiatives will enhance sustainable fisheries, invigorate seafood consumption, and cultivate Korea’s health-conscious, ecologically aware, and culturally pertinent balanced diet.

4. Research Design

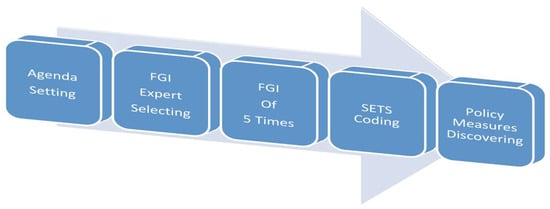

This research relies on the social, ecological, and technological systems (SETS) paradigm. This academic paradigm acknowledges the interrelation of social, ecological, and technical systems and their impact on intricate phenomena such as seafood consumption and education. Using the SETS paradigm, we sought to encompass the varied viewpoints of stakeholders and attain a comprehensive knowledge of the elements influencing seafood consumption trends and educational requirements, illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research methodological framework.

We implemented a qualitative study design, employing expert focus group interviews as the principal data-gathering technique. This method facilitated a comprehensive examination of the subject and promoted active engagement among participants, possibly resulting in the development of novel ideas and viewpoints. The study employed a selective sample technique to choose people with varied skills and positions within the seafood and education sectors, guaranteeing diverse perspectives and experiences. The six specialized groups comprised of the following:

- Policy Advisor. A representative from the Presidential Committee on Agriculture, Fisheries, and Rural Affairs, offering insights into policy recommendations and potential areas for seafood industry intervention.

- Fishery Policy Researcher. A professor specializing in fishery policy research, offering an academic perspective on the regulatory and economic aspects of seafood consumption.

- Education Researcher. A food and nutrition education professor contributing expertise on educational approaches and strategies for promoting healthy eating habits.

- Citizen Group Representative. A representative from a citizen group dedicated to food education in the agricultural sector, bringing a grassroots perspective and highlighting the role of community engagement in promoting sustainable food practices.

- Research Institute Fellow. A policy researcher from the Korea Rural Economic Institute focusing on seafood distribution policies, providing an understanding of the market dynamics and supply chain considerations.

- Government Official. A high-ranking official from the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries responsible for seafood consumption education policies, providing insights into the government’s perspective and policy priorities.

4.1. Focus Group Interview Process

We conducted five focus group interviews between October 2022 and February 2023. Each interview lasted about two hours and adhered to a semi-structured format. A moderator guided the talks, ensuring all participants articulated their perspectives. We audio-recorded the interviews and transcribed the recordings with the participants’ permission for further examination. We presented initial findings to the participants to guarantee a proper depiction of their perspectives and request input on our interpretations. Table 1 shows the focus group interview agenda.

Table 1.

Focus group interview agenda.

4.2. Keyword Content Analysis via Sociological, Ecological, and Technological Systems (SETS) Coding

Our researchers uploaded the transcripts into Dedoose, a web-based platform for qualitative data analysis, for keyword content analysis. Dedoose’s text mining functionalities helped systematically discover and categorize essential words and phrases within the transcripts, enabling effective analysis of the conversation material and discerning reoccurring themes and trends.

We chose manual content keyword coding to maintain interpretative flexibility and stay attentive to the particular vocabulary and jargon used by expert stakeholders. Despite their potency, machine learning algorithms may falter in comprehending the contextual subtleties and specialized terminology inherent in conversations, thus resulting in misinterpretations or oversimplifications of the data. We selected manual human-oriented content keyword coding over machine-learning text mining owing to numerous significant criteria. First, human knowledge facilitates sophisticated comprehension and contextual interpretation of material, frequently beyond the capabilities of contemporary machine learning algorithms. Our approach guarantees that the keywords represent the desired significance and pertinence within the specific academic and professional environment. Also, manual coding provides more flexibility and adaptability in addressing complicated and multidisciplinary study subjects where standard methods may be inadequate. Ultimately, hand coding enhances engagement with the material, promoting comprehensive and reflective examination, crucial for generating high-quality, dependable, and legitimate research results. Consequently, manual human-centric content keyword coding offers a more rigorous and accurate methodology for this research.

In accordance with the human-centric content keyword coding process, we categorized the keywords in Dedoose software according to the SETS framework rules, dividing them into social, ecological, and technical categories [45]. The coding features of Dedoose enhanced the organizing and management of qualitative data, allowing us to align the varied viewpoints of participants with the SETS framework and discern their main areas of emphasis. Dedoose’s quantitative analysis tools allowed us to calculate term frequency (TF) percentages for the coded data, offering a numerical depiction of the proportional importance assigned to each SETS category by various expert groups. This calculation facilitated a more impartial assessment of participants’ viewpoints and priorities. Concurrently, we endeavored to uphold a reflective methodology throughout the study process, recognizing our inherent biases and preconceptions and their possible impact on the research design and interpretation of results.

SETS systematically categorizes many techniques and interventions for seafood consumption management, considering their social, ecological, and technical aspects. This classification aids in comprehending the complex nature of seafood consumption and formulating comprehensive control strategies. SETS, revised according to the guidelines by Chang et al. [46], is a classification framework designed to control seafood consumption. It further categorizes the three overarching aspects (social, ecological, technological) into more detailed classifications.

The “social” part of the framework comprises three categories. Social aspects (S1) encompass strategic planning, administration, and public health, including national dietary guidelines, public health services, and institutional oversight of fish consumption. It entails fostering collaboration among relevant departments and forming public–private partnerships. Knowledge transfer (S2) emphasizes disseminating information and expertise about nutritional deficiencies, reactions, and the benefits of seafood consumption while supplying essential information to communities and other departments. The final category, norms and informal practices (S3), encompasses optimal management techniques and recommendations, including economic considerations such as budgetary assistance, resource allocation, and cost–benefit analysis related to seafood consumption management.

The ecological dimension also has three subcategories. Ecological aspects (E1) focus on conserving and restoring fishery resources and marine ecosystems, prioritizing ecosystem health, biodiversity, and habitat restoration. Eco-friendly food infrastructure (E2) pertains to green infrastructure and ecological engineering methodologies that employ sustainable technologies and techniques. Lastly, ecological services (E3) oversee the environmental advantages of ecological services concerning fish consumption.

In the final dimension (technological) of the framework, we find technical aspects (T1), which encompass sophisticated aquaculture techniques, innovative design standards, and digital technology for seafood traceability and online commerce. In T2 section, nutritional research in aquaculture involves the examination of the correlation between dietary practices and illnesses and enhancing aquaculture systems via systematic monitoring and maintenance. The final element is technical solutions (T3), which concentrates on technical innovations for seafood management, encompassing research and development in processing, storage, new product creation, establishing information-sharing platforms, and applying technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR) for seafood experiences.

Thus, our research seeks to deliver an in-depth analytical result of the existing seafood consumption education trend in South Korea and to pinpoint possible avenues for future enhancement.

5. Results

To obtain a deeper comprehension of the complex nature of educating expert staff on seafood dietary practices, we utilized the social, ecological, and technological systems (SETS) framework to examine the viewpoints of many stakeholders. This method elucidates the intricate social, ecological, and technical interactions in seafood dietary education. The average scores reveal a primary emphasis on the social dimensions (S1, S2, S3), succeeded by the technological (T1, T2, T3) and ecological (E1, E2, E3) dimensions (Table 2). Our SETS finding indicates that although the respondents recognize the significance of technological and ecological aspects, they predominantly emphasize the social features of seafood consumption and education.

Table 2.

Term frequency (TF) ratio heatmap of keywords in SETS coding with focus group interviews.

The emphasis placed by different stakeholders varied significantly across dimensions. For example, the policy advisor (Advisory Board Member) primarily focused on S1 (strategic planning, readiness, management, reaction, public health), accounting for 39.74% of their contributions. Similarly, the education researcher emphasized S1 with 28.31%, underscoring the importance of policy-level interventions and public health considerations in the comprehensive management of seafood consumption from a societal viewpoint. Conversely, the fishery policy researcher exhibited a strong interest in S3 (norms and informal practices, economic elements), attributing 24.00% to this dimension. This suggests an inclination toward exploring the regulatory framework, economic implications, and the interplay between formal and informal practices influencing seafood consumption trends. Thus, the findings highlight distinct focal points across stakeholder groups, reflecting diverse priorities in seafood consumption management. In addition, the government official, collaborating with the policy advisor and education researcher, significantly focused on S1 (29.05%), underscoring the governmental viewpoint on the strategic planning and control of seafood consumption, presumably prioritizing policy development and execution.

In contrast, the citizen group and research institute fellow strongly concentrated on T2 (20.73% and 22.17%) (nutrition, aquaculture), shown by the warmer hues in Table 2. This result indicates participants’ focus on a pragmatic and implementation-driven viewpoint, highlighting the significance of nutritional studies, aquaculture methodologies, and the technological elements necessary for sustainable seafood production and consumption. Their principal emphasis on T2 (nutrition, aquaculture) indicates a pragmatic and implementation-focused approach, underscoring the significance of nutritional research, aquaculture methodologies, and the technological dimensions of guaranteeing sustainable seafood production and consumption.

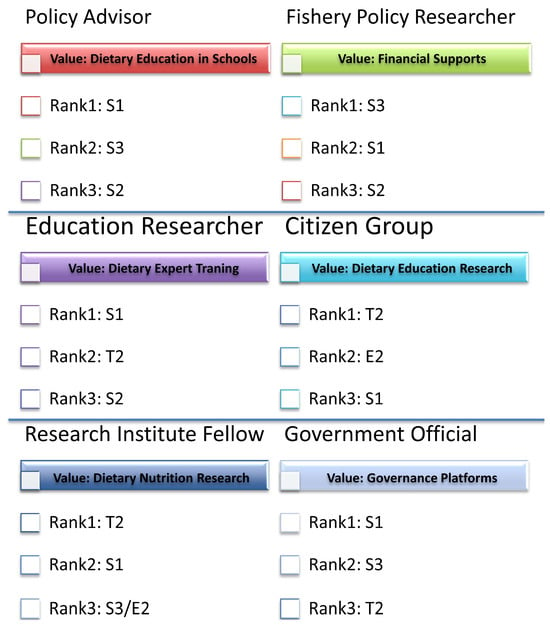

The heatmap further illustrates discrepancies within each SETS group. For example, although individuals prioritize social dimensions, variations exist in the subcategories highlighted by each expert group (S1, S2, and S3). The heatmap facilitates the identification of supplementary focal topics for each expert group. For instance, the citizen group (20.73% on T2) and research institute fellow (22.17% on T2) predominantly concentrated on T2; however, they have a moderate interest in S2 (knowledge and know-how transfer) and T3 (technical solutions). This analysis of the focus group interviews enabled us to comprehend significant outcomes derived from quantitative and qualitative methodologies to propose potential future policy initiatives. Figure 2 illustrates the results of the focus group discussions.

Figure 2.

Ranking of SETS based on focus group members.

The SETS classification and analysis offer a thorough and nuanced comprehension of the complex nature of seafood dietary instruction. Our research emphasizes the significance of social factors in enhancing seafood consumption and dietary education.

6. Discussion

Incorporating blue food, especially fish, into the diets of K–12 students exemplifies a complex strategy for enhancing health and sustainability, analyzed via the social, ecological, and technological systems (SETS) framework. This paradigm offers an in-depth analysis of the intricate interactions among social, ecological, and technical elements that affect seafood consumption and its effects on youth health [47]. We conducted focus group interviews with experts to explore the significance of seafood intake for the health of the youth generation. The interviews obtained insights from a diverse cohort of six specialists, including professionals such as nutritionists, marine biologists, policy researchers, environmental scientists, educators, and technologists. The classification of these findings within the SETS framework offers comprehensive knowledge of the diverse advantages of seafood consumption.

The social aspect of eating seafood transcends personal dietary selections, involving wider community interactions and cultural traditions [48]. Experts emphasized the significance of seafood in promoting community involvement and social togetherness [32]. They highlighted how traditional seafood recipes unite families and communities, fostering shared cultural experiences and strengthening social connections. Shared seafood dinners can enhance familial relationships and cultivate social ties among classmates, thus contributing to the social development of K–12 adolescents [49]. Furthermore, educators emphasized the significance of integrating seafood-related subjects into school curricula to enhance students’ understanding of seafood’s nutritional and ecological advantages [50]. Rising seafood demand can boost coastal communities’ economies, creating a positive feedback loop that sustains local livelihoods and food security [51].

From an ecological standpoint, conscientious seafood consumption corresponds with environmental stewardship objectives [52]. Sustainable fishing techniques and effectively managed aquaculture businesses can preserve marine biodiversity and ecological integrity in everyday life [53]. Experts highlighted the importance of students as environmental stewards, urging them to make educated decisions on seafood consumption to guarantee the survival of marine resources. Educating K–12 children on the ecological consequences of their food selections helps foster a generation of environmentally aware customers who see the need to preserve aquatic resources. Marine biologists and environmental scientists put high value onto the need for sustainable fishing techniques and aquaculture to preserve marine biodiversity. They offered insights on how prudent seafood intake might enhance the health of aquatic ecosystems [54]. This understanding can foster more sustainable consumer habits and bolster conservation initiatives, therefore maintaining the long-term health of marine ecosystems [55].

The technological aspect of seafood consumption includes production, processing, and distribution advancements [56]. Advanced aquaculture methods have enhanced the efficiency and sustainability of seafood production, potentially alleviating the strain on wild fish populations [57]. Food technology has enhanced seafood products’ safety, quality, and shelf life, making them more accessible to a wider population [58]. Moreover, digital platforms and educational technology provide novel opportunities for conveying knowledge on the advantages of seafood and sustainable practices, enabling students to make educated dietary decisions [56,59].

Scholars have demonstrated significant health advantages of eating seafood for K–12 students [60]. Seafood, abundant in omega-3 fatty acids, premium proteins, vitamins, and minerals, is essential for children’s cognitive development, immunological function, and general growth [61]. Researchers have linked consistent seafood eating to better mental health outcomes and higher academic achievement in kids [62]. Moreover, health professionals emphasized the capacity of seafood to reduce the risk of chronic illnesses, boost mental well-being, and improve academic achievement in pupils [63]. Integrating seafood into adolescent diets might foster enduring good-eating practices, decreasing the likelihood of chronic illnesses later in life [64].

In the study’s analytical process, SETS coding delineates a qualitative data analysis approach employed to classify and examine data based on the interconnections and interdependencies among social, ecological, and technological systems [65] in the context of seafood consumption education in South Korea. This method is especially beneficial in research on complex systems and their dynamics. This study employed SETS coding to examine the content of focus group interviews with specialists in seafood dietary education. Utilizing SETS coding, the researchers methodically analyzed the data to discover significant themes and patterns within each area [66]. This method offered an extensive comprehension of the diverse aspects affecting seafood dietary education and assisted in developing specific enhancement strategies. Therefore, it is vital to include the SETS guideline in nutritional education by promoting the consumption of blue foods. This broad view of SETS is crucial for formulating successful educational programs and initiatives encouraging sustainable and healthy seafood eating patterns [33].

The focus group interviews demonstrated a thorough comprehension of the significance of blue food consumption for youth health within the SETS framework, highlighting the interrelated social, ecological, and technological factors affecting seafood consumption among K–12 students. The focus group interview with seafood consumption specialists highlighted the requirement for structured seafood dietary instruction in K–12 institutions. The research issued by Korea Presidential Committee on Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Policy [67] indicates a substantial deficiency in the existing educational framework, as 67.1% of K–12 schools in South Korea do not provide seafood dietary knowledge, while just 25.6% provide limited training. This finding underscores an urgent need to incorporate seafood knowledge into the educational curriculum.

Experts highlighted numerous critical areas for enhancement, highlighting the need for nutrition and balanced diet instruction concerning seafood. Examining the focus group material, classified by SETS keywords, found “nutrition and balanced diet of seafood” as the most often referenced element, followed by “safe seafood, proper consumption”, “seafood cooking and consumption tendency”, and “sustainable fisheries and clean marine environment”. Experts unanimously advocated creating specialized textbooks and instructional resources centered on seafood nutrition and dietary education to address these deficiencies. Additional notable recommendations encompassed targeted nutrition education for seafood, diversity of empirical educational programs, augmented budgetary support for seafood in school meals, and the advocacy for incorporating high-quality fish in school meal offerings.

The advantages of incorporating seafood into K–12 meals are evident, although other barriers require attention. These encompass guaranteeing fair access to high-quality fish products, surmounting cultural obstacles to seafood consumption, and tackling issues related to environmental toxins. Future research on seafood consumption and nutritional education should create culturally relevant interventions to enhance seafood intake across student groups and investigate novel methods to integrate seafood into school lunch programs.

The highlighted limitations encompass the absence of specialized educational resources, inadequate student engagement, and logistical barriers in culinary and experiential activities. These barriers highlight the necessity for a cooperative strategy among educational institutions, the seafood sector, and governmental bodies to provide the essential infrastructure for successful seafood dietary education. Building a governance platform could encourage debates on constructing this well-organized infrastructure, with outcomes translated into tangible policy [68]. Creating and disseminating specialized educational resources, developing varied experience programs, and augmenting support for seafood school meals are essential measures for improving seafood dietary education [69]. The Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries must spearhead the commercialization of the planned enhancements to guarantee the effective execution of these efforts.

This study is valuable since it investigated enhancement strategies via extensive focus group interviews with seafood dietary education professionals. The global imperative for seafood dietary education is becoming apparent; nonetheless, academic research is lacking in addressing this problem. Consequently, the answers presented in this study necessitate thorough assessment and contemplation in future policy formulation. The study team performed content analysis utilizing SETS coding derived from focus group interviews and recommended two policy actions to enhance seafood dietary education.

6.1. Future Direction for Improving Seafood Dietary Education 1: Development of Seafood Dietary Education Programs

The objective of seafood dietary education is to comprehend seafood’s origins and production methods, and its importance from environmental, social, and cultural viewpoints. Consequently, it is essential to methodically examine the necessity of seafood dietary education as an eco-friendly blue food, its importance and objectives, the target audience, and the location, content, and methods of instruction.

The seafood dietary education program (Table 3) comprises internal school and external out-of-school programs. The educational curriculum has four groups: preschoolers, elementary school students, middle school students, and high school students. The extracurricular curriculum encompasses adults, including parents, and specialized groups, such as nutrition educators and dietary instructors, resulting in six categories. The K–12 class hours aimed at enhancing seafood dietary habits are the suggested minimum duration necessary for a fundamental comprehension of the fishing business, the health and nutritional benefits of seafood, environmental sustainability, and culinary practices, including seafood. Few programs in K–12 schools and extracurricular dietary education courses focus on seafood. All focus group specialists concurred that expanding class hours, similar to agriculture sector ones, would face significant limitations. Addressing this situation requires progressively more talks on class hours and subject areas per topic and gathering insights from educational authorities and experts in relevant sectors.

Table 3.

Six programs of seafood dietary education.

Among the six suggested seafood dietary education initiatives, experts delineated the one targeting elementary school students, emphasizing rigorous nutritional education throughout the life cycle. Table 4 indicates the vision and instructional objectives of the curriculum for primary school students.

Table 4.

Vision and objectives of seafood dietary education program for elementary school students.

Table 5 presents the titles and details of programs for elementary school students that promote health, environmental awareness, and a fundamental understanding of fishing villages, a key part of the blue food seafood industry, and the seafood produced there.

Table 5.

Content structure of seafood dietary education program for elementary school students.

First, the basic program aims to provide a correct understanding of the seafood we eat and the lives of people engaged in seafood-related occupations through education on the process of seafood reaching the table and jobs related to the sea and seafood. Second, the health program emphasizes the need for education on why we should consume seafood from a health and nutritional perspective through stories of healthy seafood. Additionally, “The World of Seafood Cooking” class aims to allow students to practice cooking with seafood and experience its taste with all five senses. Third, the environmental program seeks to enhance knowledge of the seriousness of concerns such as climate change, marine pollution, and the depletion of marine resources through the “Protecting the Clean Marine Environment and Marine Resources” course. It also seeks to acknowledge the significance of sustainable food consumption. The “How to Eat Seafood Safely” course focuses on deboning fish and eating seafood more safely and conveniently through practical exercises. Finally, the consideration program aims to understand the traditional food culture of fishing villages and recognize them as spaces for life, resting, tourism, experience, and leisure through the “Old Culture Remaining in Fishing Villages” and “Experiencing Fishing Villages and Seafood” classes.

6.2. Future Direction for Improving Seafood Dietary Education 2: Training Specialized Personnel for Seafood Dietary Education

The culture of seafood dietary education, which ensures health and environmental sustainability as blue food, may benefit South Korea and the worldwide community. Activating seafood nutritional instruction necessitates training expert individuals committed to this educational endeavor. Currently, the dietary education program of the Korea National Network for Dietary Education, managed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs in South Korea, lacks seafood-related instruction and a cadre of specialist teachers. We recommend the following strategies for educating specialist workers in internal and external educational programs within South Korea’s existing educational framework.

Initially, it is imperative to collaborate with local educational authorities to facilitate the incorporation of seafood dietary education into the vocational training programs for newly appointed or existing nutrition educators in K–12 institutions. Achieving this objective requires pre-preparing dietary textbooks for nutrition educators and incorporating seafood-related competency development into the job training programs of local educational authorities. The present work training solely encompasses instruction on the National Education Information System (NEIS), administration of school lunch budgets, and cleanliness and safety protocols to avert food poisoning. Institutions should enhance nutritional education regarding the consumption of blue food fish according to this strategy. Considering the diverse physical, chemical, and biological hazards linked to seafood, alongside the contentious discharge of radioactive water from Fukushima and the extensive precautions required in preparing and handling seafood for school meals, it is imperative to enhance the training curriculum for nutrition educators.

Second, training specialists for seafood nutritional instruction in extracurricular activities necessitates a novel decision-making governance structure. When the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries successfully initiates a project to train specialists in seafood dietary education, it must formulate a mid- to long-term business plan, develop a specialized training program, and designate an institution accountable for appointing, operating, and overseeing the educational instructor team. We suggest the National Federation of Fisheries Cooperatives or the Korea Fisheries Infrastructure Promotion Agency as accountable entities. The National Federation of Fisheries Cooperatives, as a representative entity of the fisheries sector, is suitable for advancing the specialized personnel training initiative, given the significance of seafood dietary education and the scale and symbolism of the implementing institution. The Korea Fisheries Infrastructure Promotion Agency, which facilitates the training of marine interpreters, can contemplate expanding and restructuring the marine interpreter training program to incorporate seafood nutrition instruction. The “Marine Interpreter” program is a specialized training initiative that offers professional interpretation of marine resources, fisheries, fishing towns, and ports for visitors visiting these areas. Thus, a complete and multifaceted approach to seafood dietary education is essential for promoting Korea’s sustainable and health-conscious seafood consumption culture.

6.3. Limitations of the Research

This research outlines a number of methodological issues that need to be recognized. A limitation of the study is the small sample size of experts subjected to the focus group interview, which although diverse in professional backgrounds, might miss some perspectives of the seafood education domain. The use of qualitative research enabled us to delve into the participant’s experiences in the context of seafood education, but at the same time, it made us not able to infer the findings to the statistically larger populace. We also have the SETS framework coding process that kept the whole thing systematic, while human subjectivity is embedded in it and is thus capable of shading the theme categorization. The study confined itself to South Korean contexts and may not tell us anything about findings that might be obtained in other cultural settings with other seafood consumption patterns and that might be equally significant to the South Korean one. Moreover, the absence of reflection from the direct experience of students and consumers points out that the beneficiaries of the seafood education programs who can bring in a greater variety of ideas will miss out in the discussion. Ultimately, the investigation will offer theoretical program frameworks which will promote educational approaches without proof of the implementation effectiveness; thus, the need for subsequent intervention studies becomes obvious to verify the proposed educational approaches.

7. Conclusions

This study undertook a comprehensive examination of the current state of seafood consumption education within South Korea. Employing the social, ecological, and technological systems (SETS) framework as an analytical lens, the research aimed to pinpoint critical policy variables crucial for fostering healthier dietary habits, with a particular focus on engaging younger generations. The SETS framework allowed for a holistic understanding of the interconnected factors influencing seafood consumption education, considering societal norms and structures, environmental sustainability, and technological advancements in the seafood industry and educational delivery.

The findings of our investigation revealed a significant and concerning deficiency in the existing educational framework concerning seafood consumption. While some efforts are underway, they appear to lack the depth, breadth, and strategic coherence necessary to effectively shape dietary behaviors. A key discovery was the distinct prioritization of the social dimensions of seafood consumption education among stakeholders. This emphasis primarily revolves around legislative measures related to food safety and labeling, addressing public health concerns associated with seafood intake (such as nutritional benefits and potential risks) and the overarching regulatory landscape governing the seafood industry. Following the social dimension, the technical aspects, including seafood processing, distribution, and culinary applications, and the ecological dimensions, concerning sustainable fishing practices, aquaculture, and the environmental impact of seafood production and consumption, received comparatively less attention.

This observed prioritization of social factors suggests a current focus on the governance and health implications of seafood consumption. While crucial, the relative neglect of technical and ecological dimensions may result in a less complete understanding among the populace, particularly younger individuals, regarding the journey of seafood from its source to their plates and the broader environmental context. This imbalance could hinder the development of informed and sustainable seafood consumption habits.

Our analysis showed that while the ecological dimension could not achieve rank 1 based on six groups’ interviews, its subcategories—highlighting the impacts of Earth’s changing climate—emerge as more significant than the dietary habits related to seafood consumption. This observation emphasizes the growing importance of sustainable ecological practices in shaping seafood consumption trends. Furthermore, stakeholders consistently highlighted the ecological dimension as more critical than the technical dimension, underscoring its role in addressing broader systemic challenges. However, this study focuses on the policy elements that aim to educate and encourage seafood consumption—a localized consideration within the expansive domain of dietary education policies.

Thus, these findings offer significant insights for politicians and educators to improve seafood education campaigns and advocate for sustainable seafood eating habits. Future research might investigate the ecological dimensions, examining the environmental consequences of various seafood production techniques and consumption trends and creating educational materials highlighting the interrelation of social, ecological, and technological factors in seafood consumption.

Author Contributions

C.-Y.H. provided direction for this research work and participated in this research. C.-Y.H. and H.-D.L. performed the literature review and collected relevant data, and both authors wrote the manuscript. In addition, C.-Y.H. and H.-D.L. searched for and collected data for the cross case study; they also searched for and collected the literature and evidence. C.-Y.H. revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fortune. The World Needs to Redefine Sustainability in the Blue Food Sector. 2022. Available online: https://fortune.com/2022/06/29/un-ocean-conference-world-environment-ocean-sustainability-blue-food-sector-fishing-aquaculture-fiorenza-micheli/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Environmental Defense Fund. The Aquatic Blue Food Coalition Formally Launches at the UN Ocean Conference; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.edf.org/media/aquatic-blue-food-coalition-formally-launches-un-ocean-conference (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Golden, C.D.; Koehn, J.Z.; Shepon, A.; Passarelli, S.; Free, C.M.; Viana, D.F.; Allison, E.H. Aquatic Foods to Nourish Nations. Nature 2021, 598, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts Through Producers and Consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.W.; Blanchard, J.L.; Gardner, C.; Green, B.S.; Hartmann, K.; Tyedmers, P.H.; Watson, R.A. Fuel Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of World Fisheries. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.R.; Alleway, H.K.; McAfee, D.; Reis-Santos, P.; Theuerkauf, S.J.; Jones, R.C. Climate-Friendly Seafood: The Potential for Emissions Reduction and Carbon Capture in Marine Aquaculture. BioScience 2022, 72, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO & WHO; Berest, D.; Norwegian Institute of Marine Research. Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on the Risks and Benefits of Fish Consumption: Meeting Report. In Proceedings of the Food Safety and Quality Series, Rome, Italy, 9–13 October 2023; Volume 28. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379356/9789240100879-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Statistics Korea. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Survey in 2023|Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery|Press Releases; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2024; Available online: https://sri.kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20102040000&bid=11709&act=view&list_no=431430 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Korea Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. The 3rd (2020~2024) Basic Plan for Dietary Education; Korea Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- KMI (Korea Maritime Institute). Survey on Seafood Consumption Behavior Among Teenagers; KMI: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report 2022 Summary. MSC International—English. Available online: https://www.msc.org/about-the-msc/reports-and-brochures/annual-report-2021-22-summary (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Muringai, R.T.; Mafongoya, P.L.; Lottering, R. Climate Change and Variability Impacts on Sub-Saharan African Fisheries: A Review. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 29, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.I.; Wassénius, E.; Jonell, M.; Koehn, J.Z.; Short, R.; Tigchelaar, M.; Wabnitz, C.C. Four Ways Blue Foods Can Help Achieve Food System Ambitions Across Nations. Nature 2023, 616, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Seafood. A Wider View: It’s Blue Food’s Time. Responsible Seafood Advocate. 2021. Available online: https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/a-wider-view-its-blue-foods-time/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kvaroy Arctic. National Seafood Month: How the Blue Foods We Eat Today Will Impact Our Tomorrow. 2021. Available online: https://www.kvaroyarctic.com/blog/national-seafood-month-how-the-blue-foods-we-eat-today-will-impact-our-tomorrow (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Allison, E.H.; Barange, M.; Bene, C.; Bianchi, G.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Crona, B.I.; Yagi, N. Harnessing Blue Foods for a Sustainable Future. Nature 2023, 614, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Tlusty, M.F.; Fiorella, K.J.; Golden, C.D.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Fanzo, J. The Potential of Aquatic Foods to Improve Nutrition and Food Security in the Global South. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100471. [Google Scholar]

- Gephart, J.A.; Davis, K.F.; Edwards, P. Environmental Impact of Dietary Change: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125862. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, D.; Block, R.; Mousa, S.A. Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout Life. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.J.; Griffin, R.A.; Domoney, E.; Smith, H.C.M.; Tilsley, L.J.; Ellis, C.; Daniels, C.L. Low-Impact Rearing of a Commercially Valuable Shellfish: Sea-Based Container Culture of European Lobster Homarus Gammarus in the United Kingdom. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2023, 15, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabre, I.; Rodriguez, L.O.; Smallwood, J.M.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Alcamo, J.; Antonarakis, A.S.; Stenseth, N.C. Actions on Sustainable Food Production and Consumption for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandh, S.A.; Malla, F.A.; Qayoom, I.; Mohi-Ud-Din, H.; Butt, A.K.; Altaf, A.; Ahmed, S.F. Importance of Blue Carbon in Mitigating Climate Change and Plastic/Microplastic Pollution and Promoting Circular Economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, S.; Esteve-Llorens, X.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Carbon Footprint and Nutritional Quality of Different Human Dietary Choices. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.E.; D’Abramo, L.R.; Glencross, B.D.; Huyben, D.C.; Juarez, L.M.; Lockwood, G.S.; Valenti, W.C. Achieving Sustainable Aquaculture: Historical and Current Perspectives and Future Needs and Challenges. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 578–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y. Trends in Seafood Consumption and Factors Influencing the Consumption of Seafood Among the Old Adults Based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009~2019. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 51, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Baek, E. Diagnosis of Koreans’ Seafood Consumption: Problems and Policy Tasks in Supply and Demand Estimation. J. Korean Isl. 2024, 36, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Rimm, E.B. Fish Intake, Contaminants, and Human Health: Evaluating the Risks and the Benefits. JAMA 2006, 296, 1885–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichifor, B.; Zaiț, L.; Timiras, L. Drivers, Barriers, and Innovations in Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B. A study on the history and future direction of fishery science in Korea. J. Fish. Mar. Sci. Educ. 2021, 33, 1140–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.D.; Porter, J.; Lawrence, M. Healthy and environmentally sustainable food procurement and foodservice in Australian aged care and healthcare services: A scoping review of current research and training. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, S.; Verma, P.; Bodh, S. The role of food industries in sustainability transition: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbede, I.O.; Fakoya, K.A.; Adewolu, M.A.; Jolaosho, T.L.; Adebayo, J.A.; Oshodi, E.; Sanni, L.O.; Olagunju, O.F.; Akanbi, O.R.; Abikoye, O. Understanding the social–ecological systems of non-state seafood sustainability scheme in the blue economy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2721–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmery, A.K.; Alexander, K.; Anderson, K.; Blanchard, J.L.; Carter, C.G.; Evans, K.; Fischer, M.; Fleming, A.; Frusher, S.; Fulton, E.A.; et al. Food for all: Designing sustainable and secure future seafood systems. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, I.; Stewart, A.W.; Hancox, R.J.; Beasley, R.; Murphy, R.; Mitchell, E.A. Fast-food consumption and body mass index in children and adolescents: An international cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. What is the status of food literacy in Australian high schools? Perceptions of home economics teachers. Appetite 2018, 108, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G.; Peralta, L.R. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintzoglou, T.; Skuland, A.V.; Carlehög, M.; Sone, I.; Heide, M.; Honkanen, P. Providing a food choice option increases children’s liking of fish as part of a meal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhage, C.L.; Gillebaart, M.; van der Veek, S.M.C.; Vereijken, C.M.J.L. The relation between family meals and health of infants and toddlers: A review. Appetite 2018, 127, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Misra, A.; Gupta, N.; Hazra, D.K.; Gupta, R.; Seth, P.; Agarwal, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Jain, A.; Kulshreshta, A. Improvement in nutrition-related knowledge and behaviour of urban Asian Indian school children: Findings from the “Medical education for children/Adolescents for Realistic prevention of obesity and diabetes and for healthy aGeing” (MARG) intervention study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, H. An Analysis of Exchange Rate Pass-through of Imported Seafood in Korea. Ocean. Policy Res. 2023, 38, 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.; Kim, J. The Relationship of Consumer Anxiety of Food Hazard, and Food Consumer Information Literacy with Dietary Life Satisfaction. J. Rural. Dev. 2020, 43, 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Casillas, A.; Brown, A.; Li, Z.; Heber, D.; Norris, K.C. Precision Nutrition and Racial and Ethnic Minority Health Disparities. In Precision Nutrition; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D.; Heller, M.C.; Roberto, C.A. Position of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior: The Importance of Including Environmental Sustainability in Dietary Guidance. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, E.H.; Constantino, S.M.; Centeno, M.A.; Elmqvist, T.; Weber, E.U.; Levin, S.A. Governing Sustainable Transformations of Urban Social-Ecological-Technological Systems. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; David, J.Y.; Markolf, S.A.; Hong, C.Y.; Eom, S.; Song, W.; Bae, D. Understanding Urban Flood Resilience in the Anthropocene: A Social–Ecological–Technological Systems (SETS) Learning Framework. In The Anthropocene; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- de Loyola González-Salgado, I.; Rivera-Navarro, J.; Díez, J.; Gravina, L. School principals’ perceptions of adolescents’ eating behaviors in two Spanish cities: A qualitative study based on the neo-ecological theory. Appetite 2025, 194, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P. Cultural influences on dietary choices. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 88, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.A.; Leahy, D.; Patlamazoglou, L.; Bristow, C.; McGlinchey, C.; Boyle, C. Belonging, identity, inclusion, and togetherness: The lesser-known social benefits of food for children and young people. In Food Futures in Education and Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli Pisetti, A. We Are What We Eat: Unsustainable Food and Diet in America; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Veitayaki, J. Securing coastal fisheries in the Pacific: Critical resources for food, livelihood and community security. Dev. Bull. 2021, 56, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak, R.; Dauriach, A.; Jouffray, J.B.; Folke, C.; Österblom, H.; Bebbington, J.; Bengtsson, F.; Causevic, A.; Geerts, B.; Grønbrekk, W.; et al. Evolving perspectives of stewardship in the seafood industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 671837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Pecl, G.T.; Evans, K.; Green, M.; McCormack, P.C.; Novaglio, C.; Trebilco, R.; Bax, N.; Brasier, M.J.; et al. Safeguarding marine life: Conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 65–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, N.; Samat, N.; Lee, L.K. Insight into the relation between nutritional benefits of aquaculture products and its consumption hazards: A global viewpoint. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 925463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Vallarasu, K. Environmental Conservation and Sustainability: Strategies for a Greener Future. Int. J. Multidimens. Res. Perspect. 2023, 1, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.L.; Langellotti, A.L.; Torrieri, E.; Masi, P. Emerging technologies in seafood processing: An overview of innovations reshaping the aquatic food industry. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azra, M.N.; Okomoda, V.T.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Breeding technology as a tool for sustainable aquaculture production and ecosystem services. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 679529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto de Rezende, L.; Barbosa, J.; Teixeira, P. Analysis of alternative shelf life-extending protocols and their effect on the preservation of seafood products. Foods 2022, 11, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, G.E.; Buro, D.; Palmer-Keenan, D.M. Recommendations for integrating evidence-based, sustainable diet information into nutrition education. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trondsen, T.; Braaten, T.; Lund, E.; Eggen, A.E. Consumption of Seafood—The Influence of Overweight and Health Beliefs. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Desai, S.S.; Mane, V.K.; Enman, J.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P.; Matsakas, L. Futuristic Food Fortification with a Balanced Ratio of Dietary ω-3/ω-6 Omega Fatty Acids for the Prevention of Lifestyle Diseases. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship Between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Olivares, M.; Mohatar-Barba, M.; Fernández-Gómez, E.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Mediterranean Diet and the Emotional Well-Being of Students of the Campus of Melilla (University of Granada). Nutrients 2020, 12, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. Enhancing Adolescent Food Literacy Through Mediterranean Diet Principles: From Evidence to Practice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A. Resilience of urban social-ecological-technological systems (SETS): A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Cook, E.M.; Berbés-Blázquez, M.; Cheng, C.; Grimm, N.B.; Andersson, E.; Barbosa, O.; Chandler, D.G.; Chang, H.; Chester, M.V.; et al. A social-ecological-technological systems framework for urban ecosystem services. One Earth 2022, 5, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Presidential Committee on Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Policy. 수산식품의 식생활교육 활성화 방안 연구. 2023. Available online: https://dl.nanet.go.kr/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Baporikar, N. (Ed.) Infrastructure Development Strategies for Empowerment and Inclusion; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, M.B.; Thilsted, S.H.; Kjellevold, M.; Overå, R.; Toppe, J.; Doura, M.; Kalaluka, E.; Wismen, B.; Vargas, M.; Franz, N. Locally-procured fish is essential in school feeding programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. Foods 2021, 10, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).