The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Understanding Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products

2.1.1. Functional Value

2.1.2. Social Value

2.1.3. Conditional Value

2.1.4. Emotional Value

2.2. Brand Attitude

2.3. Brand Trust

2.4. Digital Customer Engagement

2.5. Purchase Intention

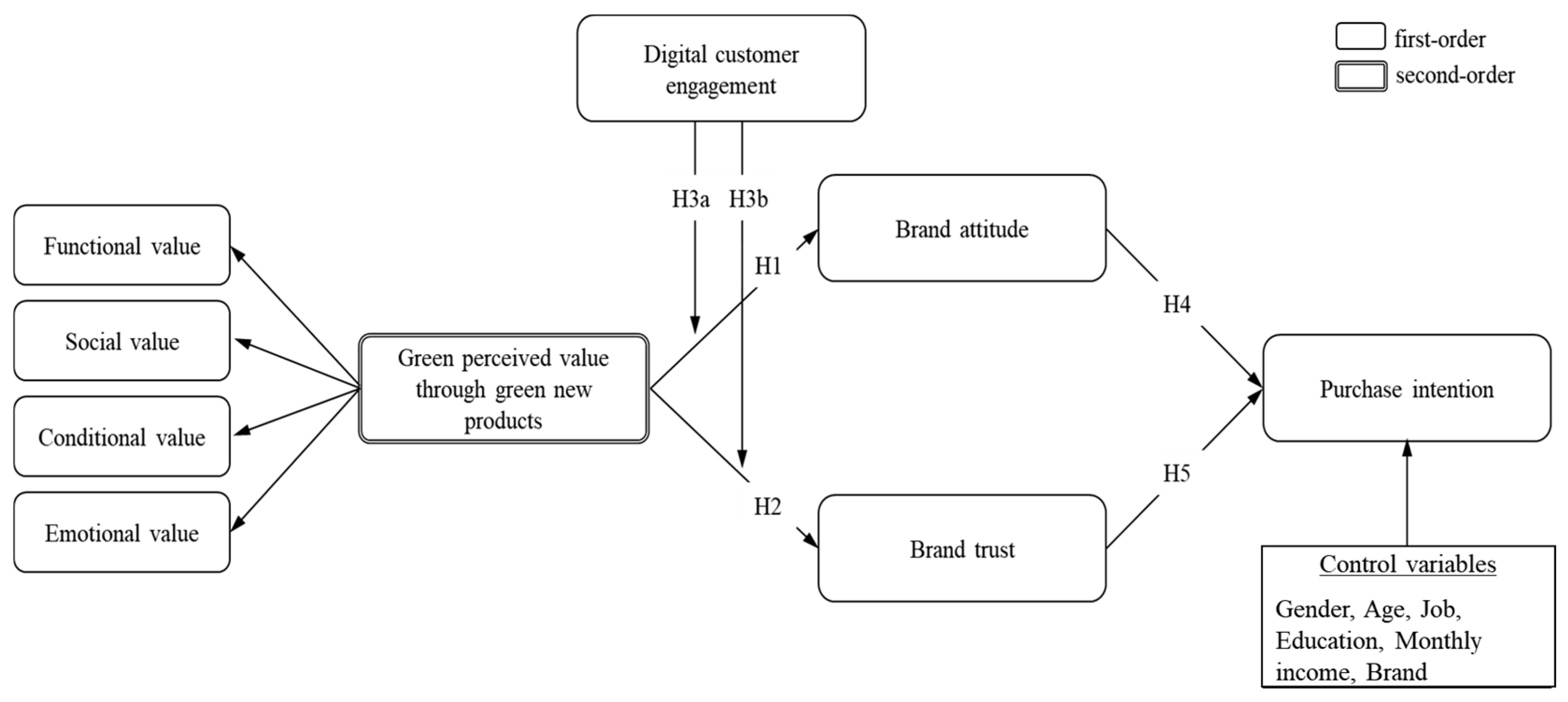

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Green Perceived Value, Brand Attitude, and Brand Trust

3.2. Digital Customer Engagement as a Moderator

3.3. Brand Attitude and Brand Trust as Drivers of Purchase Intention

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Context and Sample Collection

4.2. Analysis Methods

4.3. Measurement

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Validity and Common Method Bias Test

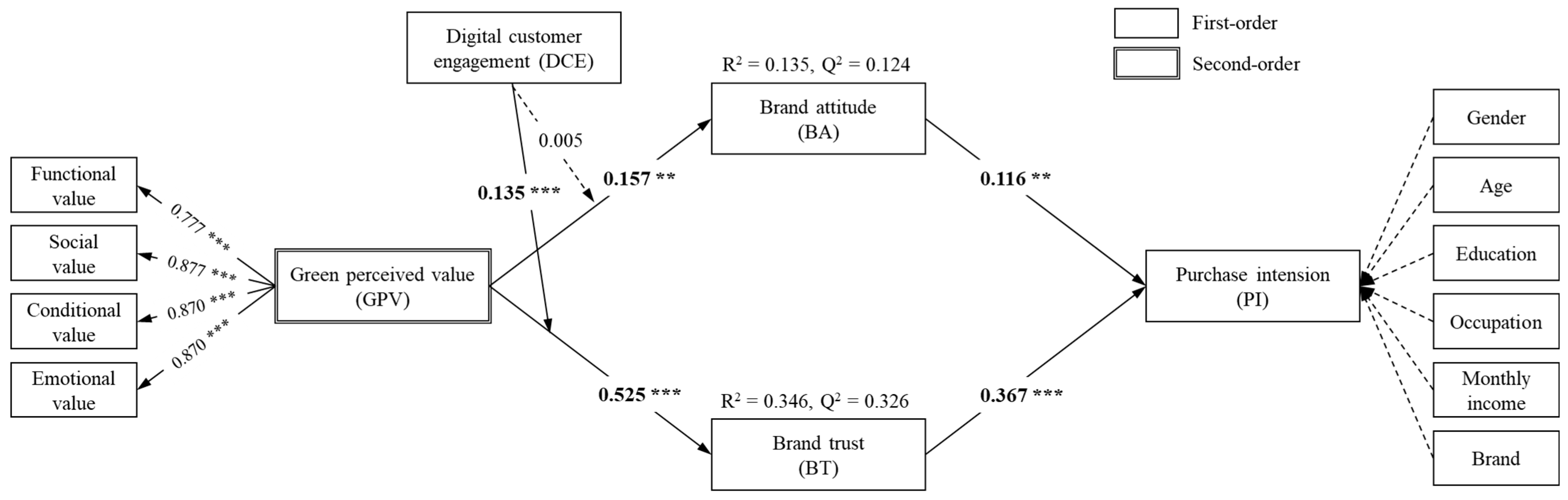

5.2. Structural Model Assessment Using PLS-SEM

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Managerial Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winston, A. Luxury brands can no longer ignore sustainability. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2016, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Athwal, N.; Wells, V.K.; Carrigan, M.; Henninger, C.E. Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Sung, Y.H. Luxury and sustainability: The role of message appeals and objectivity on luxury brands’ green corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2022, 28, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Adıgüzel, F.; Amatulli, C. The role of design similarity in consumers’ evaluation of new green products: An investigation of luxury fashion brands. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-C.A. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming consumers’ intention to purchase green products: Role of social media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalu, G.; Dasalegn, G.; Japee, G.; Tangl, A.; Boros, A. Investigating the effect of green brand innovation and green perceived value on green brand loyalty: Examining the moderating role of green knowledge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D.; Russo, I. Marketing a new generation of bio-plastics products for a circular economy: The role of green self-identity, self-congruity, and perceived value. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Magrizos, S.; Rubel, M.R.B.; Rizomyliotis, I. Green consumerism, green perceived value, and restaurant revisit intention: Millennials’ sustainable consumption with moderating effect of green perceived quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2807–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Pool, J.K. Brand attitude and perceived value and purchase intention toward global luxury brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Lee, Z.; Ahonkhai, I. Do consumers care about ethical-luxury? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry Jr, J.F.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joenpolvi, E.; Mortimer, G.; Mathmann, F. Driving consumer engagement for circular luxury products: Two large field studies on the role of regulatory mode language. J. Consum. Behav. 2025, 24, 886–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Bag, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Fattah, F.A.M.A.; Gani, M.O.; Rana, N.P. The new wave of AI-powered luxury brands online shopping experience: The role of digital multisensory cues and customers’ engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenraam, A.W.; Eelen, J.; Van Lin, A.; Verlegh, P.W. A consumer-based taxonomy of digital customer engagement practices. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 44, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, H.; Tuli, N. Digital customer engagement: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Aust. J. Manag. 2025, 50, 220–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngobo, P.V. What drives household choice of organic products in grocery stores? J. Retail. 2011, 87, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Jabeen, F.; Tandon, A.; Sakashita, M.; Dhir, A. What drives willingness to purchase and stated buying behavior toward organic food? A Stimulus–Organism–Behavior–Consequence (SOBC) perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S. Luxury and sustainable development: Is there a match? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vock, M. Luxurious and responsible? Consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility efforts by luxury versus mass-market brands. J. Brand Manag. 2022, 29, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.-N.; Michaut, A. Luxury and sustainability: A common future? The match depends on how consumers define luxury. Lux. Res. J. 2015, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, S.D.; Kang, J. New luxury: Defining and evaluating emerging luxury trends through the lenses of consumption and personal values. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 31, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Towards green loyalty: Driving from green perceived value, green satisfaction, and green trust. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflih, M.; Iswanto, B.; Purbayati, R. Green loyalty of Islamic banking customers: Combined effect of green practices, green trust, green perceived value, and green satisfaction. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2023, 40, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M. How does digital media engagement influence sustainability-driven political consumerism among Gen Z tourists? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2441–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.Á. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudayah, S.; Ramadhani, M.A.; Sary, K.A.; Raharjo, S.; Yudaruddin, R. Green perceived value and green product purchase intention of Gen Z consumers: Moderating role of environmental concern. Environ. Econ. 2023, 14, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrikulu, C. Theory of consumption values in consumer behaviour research: A review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangroya, D.; Nayak, J.K. Factors influencing buying behaviour of green energy consumer. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rosenberger, P.J., III. Reevaluating green marketing: A strategic approach. Bus. Horiz. 2001, 44, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D.; Li, J. The intention to adopt electric vehicles: Driven by functional and non-functional values. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-H. The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.-N.; Valette-Florence, P. Which consumers believe luxury must be expensive and why? A cross-cultural comparison of motivations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo-Rios, V.; Shukla, P. The effects of masstige on loss of scarcity and behavioral intentions for traditional luxury consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, B.; Rangel-Pérez, C.; Fernández, M. Sustainable strategies in the luxury business to increase efficiency in reducing carbon footprint. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Klarmann, C.; Strehlau, S.; Godey, B.; Pederzoli, D.; Neulinger, A.; Dave, K.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R. What is the value of luxury? A cross-cultural consumer perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, S.; Hamelin, N.; Khaled, M. Consumer values, motivation and purchase intention for luxury goods. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. Personal value vs. luxury value: What are Chinese luxury consumers shopping for when buying luxury fashion goods? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Sreen, N.; Das, M.; Chitnis, A.; Kumar, S. Product specific values and personal values together better explains green purchase. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R. Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles: Effects of product user stereotypes and self-image congruence. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; da Costa, M.F.; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer antecedents towards green product purchase intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Lourenço, T.F.; Silva, G.M. Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, S.; Sivakumar, V. Understanding the effect of personal and social value on attitude and usage behavior of luxury cosmetic brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.; Saura, J.R.; Santos, C.R. Revisiting the impact of perceived social value on consumer behavior toward luxury brands. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.S.; Muehlegger, E. Giving green to get green? Incentives and consumer adoption of hybrid vehicle technology. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Could environmental regulation and R&D tax incentives affect green product innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120849. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, V.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, R.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, V. Impediments to adoption of green products: An ISM analysis. J. Promot. Manag. 2014, 20, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.A.; Schokkaert, E. Identifying the warm glow effect in contingent valuation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 45, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Bilharz, M. Green energy market development in Germany: Effective public policy and emerging customer demand. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Wang, Y.; Ali, A.; Akhtar, N. Path to sustainable luxury brand consumption: Face consciousness, materialism, pride and risk of embarrassment. J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Nunes, M.F. Vegan luxury for non-vegan consumers: Impacts on brand trust and attitude towards the firm. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-Cheon Yim, M.; L. Sauer, P.; Williams, J.; Lee, S.-J.; Macrury, I. Drivers of attitudes toward luxury brands: A cross-national investigation into the roles of interpersonal influence and brand consciousness. Int. Mark. Rev. 2014, 31, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Hwang, J. Luxury marketing: The influences of psychological and demographic characteristics on attitudes toward luxury restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Phau, I.; Aiello, G. Luxury brand strategies and customer experiences: Contributions to theory and practice. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5749–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fionda, A.M.; Moore, C.M. The anatomy of the luxury fashion brand. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.; Saunders, C. Power and trust: Critical factors in the adoption and use of electronic data interchange. Organ. Sci. 1997, 8, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Goode, M.M. Online servicescapes, trust, and purchase intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Tarun, M.T. Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: A mediating role of green trust. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Xia, L. How does green advertising skepticism on social media affect consumer intention to purchase green products? J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C. Digital communication, value co-creation and customer engagement in business networks: A conceptual matrix and propositions. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 1643–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, A.; Wilson, H. Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes, J.M.; Flatten, T.C.; Brettel, M. Content strategies for digital consumer engagement in social networks: Why advertising is an antecedent of engagement. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kfairy, M.; Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Khatib, A.W.; Alrabaee, S. Social commerce adoption model based on usability, perceived risks, and institutional trust. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 3599–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabivi, E. The Role of Social Media in Green Marketing: How Eco-Friendly Content Influences Brand Attitude and Consumer Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J.; Chen, K.-S.; Wang, Y.-Y. Green practices in the restaurant industry from an innovation adoption perspective: Evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Jin, B.; George, B. Consumers’ purchase intention toward foreign brand goods. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chailan, C. Art as a means to recreate luxury brands’ rarity and value. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, C.; McKechnie, S.; Chhuon, C. Co-creating value for luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Kumar, V.; Fuxman, L.; Mohr, I. Climate change risks, sustainability and luxury branding: Friend or a foe. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 115, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, P.H.; Hillebrand, B.; Kok, R.A.; Verhallen, T.M. Green new product development: The pivotal role of product greenness. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2013, 60, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, I.U.; Ji, S.; Yeo, C. Values and green product purchase behavior: The moderating effects of the role of government and media exposure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Factors affecting sustainable luxury purchase behavior: A conceptual framework. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damberg, S.; Saari, U.A.; Fritz, M.; Dlugoborskyte, V.; Božič, K. Consumers’ purchase behavior of Cradle to Cradle Certified® products—The role of trust and supply chain transparency. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8280–8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, C.B.; Tao, L. Timely or considered? Brand trust repair strategies and mechanism after greenwashing in China—From a legitimacy perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: From the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatis, S.P.; Pollard, M.; East, R.; Tsogas, M.H. Green marketing and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour: A cross-market examination. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Silva, A.R.; Bioto, A.S.; Efraim, P.; de Castilho Queiroz, G. Impact of sustainability labeling in the perception of sensory quality and purchase intention of chocolate consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Pol. 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A key link between corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.A.d.M.; Alfinito, S.; Curvelo, I.C.G.; Hamza, K.M. Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1070–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, S. Conceptualizing the evolution and future of advertising. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A.T. A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Developing business customer engagement through social media engagement-platforms: An integrative SD logic/RBV-informed model. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 81, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Makkonen, H.; Kaur, P.; Salo, J. How do ethical consumers utilize sharing economy platforms as part of their sustainable resale behavior? The role of consumers’ green consumption values. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B. Digital Trust: Social Media Strategies to Increase Trust and Engage Customers; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Macky, K. Digital content marketing’s role in fostering consumer engagement, trust, and value: Framework, fundamental propositions, and implications. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, V.; Lo Presti, L. Stay in touch! New insights into end-user attitudes towards engagement platforms. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Lunardo, R.; Benoit-Moreau, F. Sustainability of the sharing economy in question: When second-hand peer-to-peer platforms stimulate indulgent consumption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 125, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisathan, W.A.; Wongsaichia, S.; Gebsombut, N.; Naruetharadhol, P.; Ketkaew, C. The green-awakening customer attitudes towards buying green products on an online platform in Thailand: The multigroup moderation effects of age, gender, and income. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.; Warshaw, P. Technology acceptance model. J. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Steiner, G.A. A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in Kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.; Braunsberger, K. I believe therefore I care: The relationship between religiosity, environmental attitudes, and green product purchase in Mexico. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L. A comparison of two types of price discounts in shifting consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, P.; Ramsey, E.; Williams, J. Trust considerations on attitudes towards online purchasing: The moderating effect of privacy and security concerns. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, U.; Baig, S.A.; Hashim, M.; Sami, A. Impact of social media marketing on consumer’s purchase intentions: The mediating role of customer trust. Int. J. Entrep. Res. 2020, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Kushwah, S.; Salo, J. Why do people buy organic food? The moderating role of environmental concerns and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, B. Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/long-live-luxury-converge-to-expand-through-turbulence (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Shao, J. Sustainable consumption in China: New trends and research interests. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T.; Lu, Q.; Wong, C.; Thirumaran, K.; Adegbite, E.; Kendall, W. The impact of value perceptions on purchase intention of sustainable luxury brands in China and the UK. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Pak, A.; Roh, T. The interplay of institutional pressures, digitalization capability, environmental, social, and governance strategy, and triple bottom line performance: A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5247–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 1997, 44, 174–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahng, Y.; Kincade, D.H. Retail buyer segmentation based on the use of assortment decision factors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Ranking the 10 Most Popular Luxury Brands Online IN 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2023/06/20/ranking-the-10-most-popular-luxury-brands-online-in-2023 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crede, M.; Harms, P. Questionable research practices when using confirmatory factor analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, M.-J.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Consumers’ attention, experience, and action to organic consumption: The moderating role of anticipated pride and moral obligation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Siu, N.Y.; Barnes, B.R. The significance of trust and renqing in the long-term orientation of Chinese business-to-business relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Evaluation of reflective measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Radomir, L.; Moisescu, O.I.; Ringle, C.M. Latent class analysis in PLS-SEM: A review and recommendations for future applications. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Thyagaraj, K. Impact of brand personality on brand equity: The role of brand trust, brand attachment, and brand commitment. Indian J. Mark. 2015, 45, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J. Green brand positioning in the online environment. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, T.T.A.; Vo, C.H.; Tran, N.L.; Nguyen, K.V.; Tran, T.D.; Trinh, Y.N. Factors influencing Generation Z’s intention to purchase sustainable clothing products in Vietnam. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummerus, J.; Liljander, V.; Weman, E.; Pihlström, M. Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Choi, T.-M.; Shen, B. Green product development under competition: A study of the fashion apparel industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, A. Impacts of consumer innovativeness on the intention to purchase sustainable products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Chen, Y.-J. The impact of green marketing and perceived innovation on purchase intention for green products. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, M.; Nezakati, H.; Sidin, S.M.; Yee, W.F. Consumer’s intention of purchase sustainable products: The moderating role of attitude and trust. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 7, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, I.; Porter, A.J.; Diriker, D. Harnessing digitalization for sustainable development: Understanding how interactions on sustainability-oriented digital platforms manage tensions and paradoxes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, R.; Paul, J.; Koles, B. The role of brand experience, brand resonance and brand trust in luxury consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Park, C.; Fracarolli Nunes, M.; Paiva, E.L. (Mis) managing overstock in luxury: Burning inventory and brand trust to the ground. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, J. Electric vehicle development in Beijing: An analysis of consumer purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 314 | 54.90 |

| Male | 258 | 45.10 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 20 | 7 | 1.22 |

| 20–30 | 193 | 33.74 |

| 30–40 | 294 | 51.40 |

| 40–50 | 61 | 10.66 |

| More than 50 | 17 | 2.97 |

| Education degree | ||

| High school or below | 146 | 25.52 |

| Undergraduate degree | 310 | 54.20 |

| Master’s degree or above | 116 | 20.28 |

| Job | ||

| Student | 21 | 3.67 |

| Public servant | 30 | 5.24 |

| Private business | 53 | 9.27 |

| Office worker | 376 | 65.73 |

| Housewife | 23 | 4.02 |

| Other | 69 | 12.06 |

| Monthly income (RMB) | ||

| 5000 (and below) | 74 | 12.94 |

| 5001–10,000 | 205 | 35.84 |

| 10,001–30,000 | 182 | 31.82 |

| 30,001–50,000 | 86 | 15.03 |

| 50,001 (and above) | 25 | 4.37 |

| Brand | ||

| Burberry | 67 | 11.71 |

| Chanel | 76 | 13.29 |

| Dior | 55 | 9.62 |

| Gucci | 66 | 11.54 |

| Hermès | 66 | 11.54 |

| Louis Vuitton | 67 | 11.71 |

| Rolex | 37 | 6.47 |

| Prada | 58 | 10.14 |

| Tiffany | 40 | 6.99 |

| Versace | 40 | 6.99 |

| Total | 572 | 100 |

| Construct | Items | Mean | SD | SFL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green perceived value * | FV1 | 3.517 | 1.237 | 0.720 |

| FV2 | 3.516 | 1.076 | 0.706 | |

| FV3 | 3.376 | 0.983 | 0.702 | |

| FV4 | 3.490 | 1.072 | 0.728 | |

| SV1 | 3.505 | 1.065 | 0.766 | |

| SV2 | 3.507 | 1.020 | 0.747 | |

| SV3 | 3.288 | 1.082 | 0.722 | |

| CV1 | 3.441 | 1.020 | 0.704 | |

| CV2 | 3.521 | 1.037 | 0.704 | |

| CV3 | 3.371 | 0.982 | 0.711 | |

| EV1 | 3.348 | 0.979 | 0.772 | |

| EV2 | 3.505 | 1.083 | 0.718 | |

| EV3 | 3.607 | 1.110 | 0.757 | |

| Functional value | FV1 | 3.517 | 1.237 | 0.891 |

| FV2 | 3.516 | 1.076 | 0.881 | |

| FV3 | 3.376 | 0.983 | 0.876 | |

| FV4 | 3.490 | 1.072 | 0.893 | |

| Social value | SV1 | 3.505 | 1.065 | 0.831 |

| SV2 | 3.507 | 1.020 | 0.867 | |

| SV3 | 3.288 | 1.082 | 0.866 | |

| Conditional value | CV1 | 3.441 | 1.020 | 0.840 |

| CV2 | 3.521 | 1.037 | 0.852 | |

| CV3 | 3.371 | 0.982 | 0.734 | |

| Emotional value | EV1 | 3.348 | 0.979 | 0.837 |

| EV2 | 3.505 | 1.083 | 0.888 | |

| EV3 | 3.607 | 1.110 | 0.886 | |

| Brand attitude | BA1 | 3.077 | 1.009 | 0.843 |

| BA2 | 2.743 | 1.128 | 0.843 | |

| BA3 | 2.680 | 1.028 | 0.852 | |

| BA4 | 3.178 | 1.168 | 0.893 | |

| Brand trust | BT1 | 3.589 | 0.920 | 0.806 |

| BT2 | 3.633 | 1.008 | 0.889 | |

| BT3 | 3.652 | 0.996 | 0.805 | |

| BT4 | 3.659 | 0.985 | 0.876 | |

| Digital customer engagement | DCE1 | 2.549 | 1.229 | 0.817 |

| DCE2 | 2.399 | 1.204 | 0.829 | |

| DCE3 | 2.484 | 1.137 | 0.835 | |

| DCE4 | 2.495 | 1.159 | 0.847 | |

| DCE5 | 2.486 | 1.145 | 0.856 | |

| Purchase intention | PI1 | 3.920 | 0.755 | 0.836 |

| PI2 | 3.858 | 0.745 | 0.828 | |

| PI3 | 3.766 | 0.688 | 0.852 | |

| PI4 | 3.747 | 0.791 | 0.747 |

| Construct | GPV | BA | BT | DCE | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPV * | 0.722 | ||||

| BA | 0.332 | 0.858 | |||

| BT | 0.569 | 0.247 | 0.845 | ||

| DCE | −0.741 | −0.352 | −0.438 | 0.841 | |

| PI | 0.475 | 0.210 | 0.410 | −0.396 | 0.817 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.923 | 0.880 | 0.865 | 0.896 | 0.834 |

| Composite reliability | 0.934 | 0.918 | 0.909 | 0.924 | 0.889 |

| rho_A | 0.924 | 0.881 | 0.866 | 0.898 | 0.845 |

| AVE | 0.521 | 0.736 | 0.714 | 0.707 | 0.667 |

| HTMT < 0.85 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Path | Coefficient | t-Value | p-Values | R2 | f2 | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| GPV→BA | 0.157 | 2.724 | 0.006 | 0.135 | 0.023 | Support |

| GPV→BT | 0.525 | 10.739 | 0.000 | 0.346 | 0.189 | Support |

| BA→PI | 0.116 | 2.788 | 0.005 | 0.194 | 0.025 | Support |

| BT→PI | 0.367 | 7.825 | 0.000 | 0.153 | Support | |

| Moderation effects | ||||||

| DCE GPV→BA | 0.005 | 0.161 | 0.872 | Reject | ||

| DCE GPV→BT | 0.135 | 3.497 | 0.000 | Support | ||

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| GPV→BA→PI | 0.018 | 1.729 | 0.084 | |||

| GPV→BT→PI | 0.193 | 5.965 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, M.-J. The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094106

Liu X, Kim T-H, Lee M-J. The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094106

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xuan, Tae-Hoo Kim, and Min-Jae Lee. 2025. "The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094106

APA StyleLiu, X., Kim, T.-H., & Lee, M.-J. (2025). The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement. Sustainability, 17(9), 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094106