Abstract

Population aging and urbanization are two global phenomena posing severe challenges on the transport system given the diversity of personal, social, economic, and contextual aspects on which the life quality of the elderly depends. In this regard, the aim of this study consisted in the development of a composite index to assess the criticality level of seniors’ mobility dependence, which is intended as the combination of a mobility dependence index and of a risk index. The former expresses the influence of private mobility on the older people, while the latter indicates possible vulnerabilities affecting such a transport solution. Both the indices are, in turn, made of a series of weighted performance indicators which characterize the respective topic. The proposed index has been applied to the case study of some rural Northern Italian municipalities, leading to a ranking of those areas. To this end, the priorities of indicators have been defined through a multi-attribute evaluation procedure involving a panel of experts in the social, economic and transport field, to whom a structured questionnaire has been administered. In addition, great attention has been put on gender disparities in seniors’ driving availability and ability other than on their need of accessing healthcare services. The graphical representation of the index values has supported the analysis of results, which decision-makers, i.e., operators and institutions, can take advantage of to assess different scenarios of interventions and thus to develop incentive polices.

1. Introduction

Aging is a biological transformation which affects every human being, bringing limitations not only at a physical level but also at a social level. Indeed, such decline implies losses with respect to both an individual and a collective perspective, requiring inevitable adaptation to those changes. Despite this fact, older people inherently feel the need to search for a good and satisfactory life quality in terms of their autonomy and independence in managing and performing tasks, exceeding mere survival [1]. As mentioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) in [2], the aging process is influenced by a series of factors and their interactions, which include health, behavioral, personal, social, economic, and environmental factors. The combination of these factors strongly determines the speed of the decline, implying very heterogeneous conditions among the elderly, which increasingly vary with age.

Along with the rapid aging of population, the last century has been remarkably characterized by the global phenomenon of urbanization, which caused a greater concentration of inhabitants in cities. Both the extension of life expectancy and urban growth represent the successful results of healthcare, technological and economic development, but, at the same time, they jointly pose challenges to each country in accommodating the needs of the elderly [2]. As regards the need of travelling, the transport system plays a crucial role in serving the citizens of a specific territory since it contributes to the integration of areas according to an economic, social and recreational point of view. Notably, the following two properties of transport systems are acknowledged as factors influencing people’s life quality: mobility and accessibility. The former is related to the adopted transport mode, infrastructural features and the transport service quality, while the latter concerns distance, time and cost issues to reach a certain destination [1]. Those two concepts are fundamental when planning spaces and services in order to preserve users, and especially seniors, from isolation due to unfavorable individual or contextual circumstances. Such a risk of transport-related social exclusion is even more exacerbated in remote and low-density areas, for which the peculiar location and settlement sparsity can already constitute a barrier for seamless transfers [3]. As a matter of fact, older people living in remote communities face difficulties in healthy aging which are different from those experienced by urban residents, also because of a lack in transport options to move autonomously [4].

Therefore, bearing in mind the projections of the United Nations revealing a future tendency for a growing aging of the world population [5], decision-makers are urgently called to respond with age-friendly strategies to ensure the well-being of the elderly. In this respect, the WHO suggests the development of policies, services, infrastructures and settings according to the notion of “active ageing”, which means “the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age”. The adoption of such a leading approach is intended to achieve numerous objectives, like recognizing seniors’ potential, flexibly meeting their necessities, respecting their lifestyle, protecting the most vulnerable ones, and promoting their engagement in the community. To this end, “facilitation” is the key word that should guide planning activities, together with the imperative commitment to consider diversities [6] and to establish multisectoral collaboration. Yet, according to a system perspective, person-centered services are highly recommended not only to provide older people with primary medical care, but also to assist their social, civic and economic involvement. Furthermore, even the remaining segments of the population are meant to take advantage of the benefits deriving from the implementation of age-friendly measures, creating more balance within the whole society. Initiatives to guarantee seniors’ functional ability, i.e., the combination of individual capacity, environment and the interaction between the two, require the definition of indices and/or indicators, first to analyze the current situation and then to plan actions and assess the efficiency of the proposed solutions [2,7].

In line with previous attempts of constructing composite indices to measure multidimensional phenomena [8], this paper deals with the formulation of a synthetic index to assess the degree of criticality of seniors’ mobility dependence in a specific territory while referring to several aspects. More in detail, the developed index is made of two components, i.e., a mobility dependence index and a risk index. Both components are, in turn, a function of various parameters expressing, respectively, mobility and contextual characteristics, and possible vulnerabilities impacting transport demand. The aggregation of those influential aspects into a single index is aimed at sustaining local decision-makers to outline possible interventions in a comprehensive way. At a methodological level, data collection through the consultation of public sources and face-to-face interviews with the main stakeholders, in addition to the authors’ expertise, have served the quantification of the parameters composing the suggested index. Furthermore, a multi-attribute evaluation procedure has been performed to prioritize the index parameters based on the perspectives of a panel of experts in the social, economic and transport fields. Notably, the priorities of the parameters have been defined by administering a structured questionnaire to the members of such a panel. Outcome values permit to rank the examined territories according to the criticality level of seniors’ mobility dependence and, thus, to envision improvement strategies. The measurement of such an index has been accompanied by its graphical representation, which enables to effectively highlight critical circumstances on a visual support.

The structure of this paper considers, in Section 2, a literature review concerning existing indices or indicators to appraise the mobility potential of the elderly and/or in rural areas, stressing the added value of the index presented in this study. Section 3 contains an explanation of the methodology adopted to develop the critical mobility dependence index and to determine the values of its components, whereas Section 4 describes the case study to which the proposed index has been applied. Section 5 illustrates the obtained analytical and graphical results along with their discussion, through which some conclusions regarding policy implications have been drawn.

2. Literature Review

In this study, a literature review was performed in order to investigate different areas of the main topic, i.e., elderly mobility dependence, with a specific reference to rural areas. First, the key factors influencing elderly mobility dependence were examined with the objective of motivating the selection of the indicators included in the proposed index. In this respect, existing scientific contributions agree in stating that elderly mobility dependence is a multidisciplinary issue in which the influential factors are interrelated [9,10,11]. In the literature, influential factors are usually divided into recurrent categories, in which a variety of aspects are considered to create comprehensive evaluation frameworks. For instance, the authors of [12] refer to the framework proposed by the WHO in [13], suggesting that transportation difficulty among older adults represents a dependent variable which is a function of the dynamics occurring between intrinsic and external features. Indeed, the independent variables which transport difficulty depend on are related to personal, health, participation, and environmental factors. Analogous features have been taken into account in [14], which identifies the following three categories of factors as the most impacting ones on elderly mobility: personal factors, lifestyle and attitudinal factors and built environment factors. Generally, personal factors include age, gender, education, marital status, income, occupation, driver’s license ownership, and health, if not treated separately. The category related to behavioral aspects usually encompasses the household structure, the propensity towards different mobility modes, the feeling of safety and comfort when using public transport, and the level of participation in recreational activities. Lastly, environmental factors mainly refer to the population density of the residence location, land use, territorial accessibility, trust in other people, and the appropriateness of transport facilities. Among the mentioned factors, according to the research review performed in [15], age was found not to be the strongest factor affecting the mobility of old people because psychological and financial capabilities also definitely play an important role. Nonetheless, above all, the great heterogeneity which characterizes old age must be taken into account as differences can be registered within similar cohorts of people and even over time due to possible changes with respect to personal and contextual factors [16,17].

Secondly, previous research studies were analyzed to identify the factors that challenge senior mobility, making old people vulnerable users of the transport system. In this respect, much attention was paid in [17] not only to the elderly health status but also to the conditions of the road infrastructure since they are deemed a factor that severely leads to vulnerabilities among old road users. Analogously, the authors of [18] acknowledge the relevance of the built environment, especially in terms of visibility and safety, in potentially impeding the mobility of older adults as they face greater vulnerability to accidents and crimes than the rest of the population. Furthermore, according to [19], seniors are more vulnerable than younger people to seasonality and weather, which influence both their trip frequency and transport mode choices.

Thirdly, the literature was reviewed with the aim of discussing greater difficulties that living in rural areas poses on the elderly mobility as compared to urban contexts. Two problems were identified as the main disadvantages which affect seniors living in such geographical zones, i.e., driving cessation and a lack of public transport services. Notably, based on data collected in [20,21,22,23], older adults experience a very limited availability of adequate transport options to access healthcare and other essential services, which certainly detriments their life quality.

At last, existing research studies were analyzed to investigate methods to assess the travel potential of users while considering the inclusion of people in the senior age group and/or rural areas as the reference living context. Regarding the former feature, because of the increasing aging of the global population, the scientific research has accordingly devoted more attention to issues concerning the transport needs of older people, as testified in many articles (e.g., [24,25,26,27,28]). Furthermore, this review dealt with scientific papers which analyze users’ travel potential considering both private and public transport capabilities through various, and often interrelated, concepts, like mobility, accessibility and car dependence. Indeed, despite the different denomination, those notions jointly contribute to determine the actual travel potential of people since they encompass multiple transport solutions.

For the sake of clarity, Table 1 summarizes the key aspects according to which reviewed papers were examined with the aim of highlighting the novelty of the approach proposed in this study. To that end, previous studies were classified based on their possible explicit reference to the elderly and/or to rural areas in the development of the respective travel potential index or indicator. In addition, Table 1 reports the main dimensions investigated in such research studies in terms of the transport modes considered and, possibly, of activities generating travel needs. Finally, additional details on the adopted methodologies, limitations and the obtained results are shown in Table 1 in the form of brief notes. The drawbacks characterizing the analyzed contributions motivated the construction of the composite index suggested in this paper, which is able to aggregate mobility and accessibility factors while explicitly taking into account possible fragilities for the movements of seniors.

In line with the evidence reported in [29], the spatial dimension was considered in [30] as the main feature to define indicators assessing and monitoring initiatives to foster age-friendly communities according to some interconnected urban life domains, including transport. The reason for this study was the aim of overcoming the lack of quantifiable measures which was observed in the framework reported in [2]. In recent years, this latter contribution drafted by the WHO was further enriched with additional indicators, whose scope was then extended in [31] to create an evaluation framework also suitable for rural areas. In further detail, such an adaptation considers differences in the level of urbaneness and country income, underlining the impact of the characteristics of the local context. Despite the attempt for a greater discretization of the territories, the indicators developed in [31] for the transport sector still encompass a limited series of aspects influencing seniors’ travel opportunities, mainly referring to the availability of public transport services.

As regards more articulated approaches to evaluate the mobility patterns of the elderly, researchers in [32] developed a composite index named Service Accessibility/Transport Disadvantage Index (SATDI), which consolidates various aspects of service and public transport accessibility. Indeed, the SATDI includes, on one hand, two components representing destination remoteness in terms of distance along the road network and accessibility to services relevant for seniors’ independence and life quality. On the other hand, the index encompasses two components estimating the effectiveness of public transport and the older people’s residential proximity to such transport service. The scope of the study was targeted to non-metropolitan areas of Australia, whose spatial analysis was enabled by the visualization of the SATDI through interactive georeferenced maps. Rural Australia represents the case study which has been investigated also in [33], with the aim of testing the common belief that its inhabitants apparently experience very few mobility and accessibility problems thanks to high vehicle ownership levels (and low petrol price). To this end, a “Travel needs index” is proposed, including the following factors in the equation: the percentage of households with no vehicles, the percentage of households with one vehicle, the percentage of journeys to work by public transport, and a standardized score called ARIA (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia), which in turn expresses the remoteness of rural areas from service centers of different entity, on the basis of road distance. Such index has been computed using mainly census data and considering arbitrary weighting to determine the possibility that household members do not have always access to a car in case of vehicle sharing. The obtained results show that the perception of a lack of transport-related problems in rural areas is not entirely correct, although it is hard to predict in relation to location, trends and socio-economic factors. In this respect, the influence of demographic variables has been discussed by the author of [33], but it has not been explicitly taken into account in the developed index. Moreover, counter-intuitive findings revealed by the study, like the relatively lower level of car ownership in remote areas, demand to perform more specific examinations at local level in order to grasp the actual degree of mobility deprivation.

A spatial-based methodology analogous to the one adopted in [32], has been used in [34], where the authors succeeded in identifying hotspots of transport disadvantage and forced car dependence in rural Ireland through the spatial intersection of socioeconomic indicators and the use of Geographical Information System (GIS) techniques. Similarly, car dependence in Munich, Germany, has been assessed in [35] according to a quantitatively approach and merging three main aspects, i.e., car use, car ownership and lack of public transport. To that purpose, the calculation of a Car Dependence Factor (CDF) has been followed by the application of multi linear regression to the most recent traffic and census data to identify socio-spatial predictors. Referring to a traffic zone scale, the CDF considers car ownership as an indicator for car usage, and the accessibility of opportunities, in terms of access to both points of interest and public transport. CDF turned out to be higher in rural areas than in urban regions, thus indicating a greater car dependence, which translates into high car ownership and lower opportunities without car access. Limitations in the study have been underlined with respect to the omission of time-related features of public transport, e.g., the frequency of bus services, and the reduced number of considered points of interests. Based on the reported outcomes, the authors of [35] advocate a decrease in car dependence to foster more equity among inhabitants and they suggest the inclusion of specific contextual variables to better capture their relationship with car dependence.

Further research efforts to develop composite indices for rural areas have been made in the past like, for instance, in [36], where the “transport-related welfare” of rural Wales is expressed by a synthetic index combining both mobility and accessibility factors, while considering public transport dependence as the inverse of car ownership. Such summary measure has been computed at parish level through dichotomous indicators, assuming equal weight to all the factors, although indirectly attributing a different importance to the examined public transport services on the basis of their frequency. High- and low-scoring areas have been then visualized on a map exhibiting their respective ability to communicate, but no specific reference neither to older people nor to trips to medical facilities were included. Finally, referring to a wider set of alternative transport modes, the study illustrated in [37] has been performed with the objective of appraising the elderly transport potential in some rural areas of Serbia. Analyses have been carried out based on data collected through a household survey specifically designed for rural settlements, examining the mobility characteristics of older inhabitants according to different accessibility levels of those zones. Notably, accessibility has been related to the most significant facilities for seniors acknowledged in the literature, i.e., food shops, health centers and post offices/banks, and to the transport network. The transport potential has been then estimated for a single individual and for a certain trip destination, considering personal, transport-related and environmental conditions in the formulation. The results showed that, even though the mobility of the investigated rural elderly population is quite low, remarkable discrepancies can be noted by varying the accessibility level of settlements, underlining the great impact of age and of the driving license possession on mobility.

Notwithstanding existing indicators and indices permit to capture a variety of factors influencing the movement of older people and/or in rural areas, limitations in the reviewed scientific contributions have been encountered with respect to the extent of the considered contextual and personal characteristics. As reported in the following section, the index of seniors’ critical mobility dependence suggested in the present paper addresses the inclusion of further dimensions, which describe the consequences of residential density, territorial connections, technological advancements of private vehicles, seniors’ need of medical services, and gender differences on the elderly transport potential and, thus, on their interaction with the surrounding environment. In addition, the weights attributed to the indicators composing the proposed index have been determined through the rigorous application of a multi-criteria evaluation approach.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of reviewed articles.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of reviewed articles.

| Reference | Older People | Rural/Remote Areas | Dimensions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | Yes | No | Accessibility to public transport by walking, private cars (limited to parking spaces for disabled people) |

|

| [31] | Yes | Yes | Accessibility to public transport |

|

| [32] | Yes | Yes | Accessibility to public transport and essential services |

|

| [33] | No | Yes | Mobility (availability of transport resources) and accessibility to service centers |

|

| [34] | No | Yes | Private mobility |

|

| [35] | No | No | Private mobility (car ownership) and spatial accessibility to public transport and points of interest |

|

| [36] | No | Yes | Private mobility |

|

| [37] | Yes | Yes | Accessibility to public transport and essential services, private mobility (driving license possession) |

|

3. Methods

Like mentioned, the aim of this study has consisted in the construction of an index of seniors’ critical mobility dependence to analyze, on one hand, mobility needs and trends of the elderly related to a specific territory and, on the other hand, the vulnerabilities which can possibly influence individual travel choices and, more in general, the travel patterns of the whole community. Given the variety of aspects affecting such topic and the heterogeneous conditions characterizing the inhabitants and the transport dynamics of rural environments, the development of the proposed index required an interdisciplinary methodology which involved the following steps:

- Identification of necessary data, based on the issue at hand, local knowledge, availability of public data and evidences coming from the literature, using a transport-centric approach;

- Data collection according to the proper scope, in line with the extent of the study area;

- Transformation of data into information, through the implementation of synthetic indicators and the comparison over time;

- Definition of composite indices, on the basis of the adoption of scientific methods and previous literature outcomes;

- Visualization and analysis of results, by means of graphical representation.

As anticipated, to this end, data coming from different sources and referred to multiple dimensions have been selected according to some basic principles, i.e., availability, representativeness, granularity, upgradability, replicability, and comparability, which contributed to ensure the methodology robustness. More in detail, the main consulted sources were the databases of the national institute of statistics, of the regional administrative entity, of the Italian Ministry of Transport, and of a few public transport providers. Accordingly, data retrieved from such sources referred, e.g., to the demographic and social characteristics of people, territorial and economic aspects and transfers by mode and purpose.

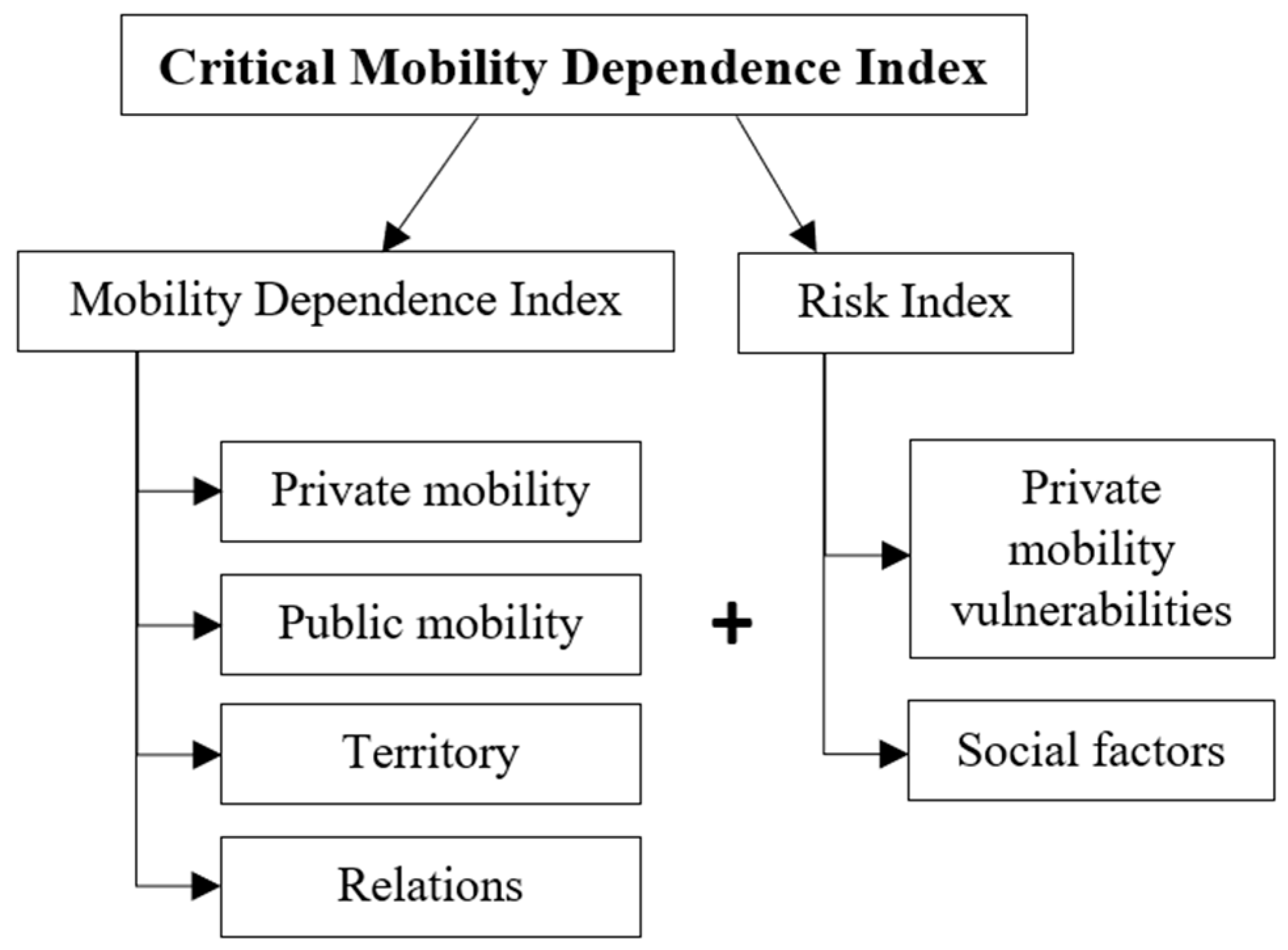

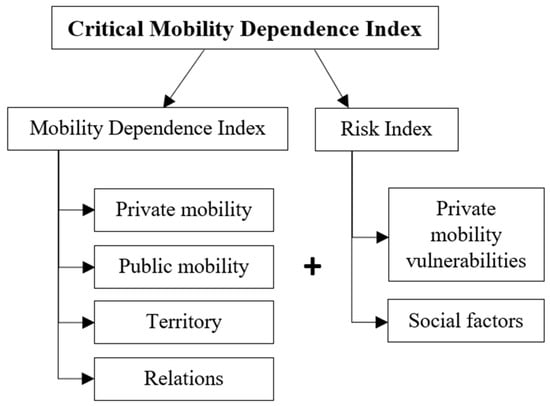

The suggested criticality index considers two components, which are a mobility dependence index and a risk index. Each of them has been developed using a two-level approach: indeed, they are both composed by the weighted sum of a series of indices, which in turn are made of multiple prioritized indicators. All the components of the developed composite index are schematically represented in Figure 1, while an explanation of every single parameter is reported in the following.

Figure 1.

Schematization of the parameters of the developed composite index.

As far as the mobility dependence index is concerned, its main level includes four indices which relate to the factors listed below:

- (A)

- Private mobility;

- (B)

- Public mobility;

- (C)

- Territory;

- (D)

- Relations.

The index referring to private mobility encompasses five indicators which, first of all, account for the availability of vehicles and of driving licenses per person ( and ) and household ( and ). As a matter of fact, the concurrent possession of a means of transport and of the ability to use it is cannot be taken for granted among older people, who are then forced to rely on alternative transport solutions or on relatives with the necessary driving authorizations. In addition, an indicator expressing the weighted average age of vehicles has been inserted in the private mobility index not to treat their environmental sustainability, but to capture the driving assistance degree provided by technological tools implemented on vehicles. This aspect turns out particularly relevant when dealing with seniors’ mobility, due to the impact of the physical decline on their driving capabilities.

The index concerning public mobility consists of two indicators, which refer to common concepts of public transport planning, i.e., service availability with respect to space and time. The former () has been expressed in terms of the number of houses located in a catchment area defined within a 500-m distance from bus stops, while the latter () is intended as the number of bus trips serving the examined municipality compared to the ones available in the whole study area.

The index related to the territory is meant to represent the opportunity of the elderly to travel without a motorized means of transport like, for example, cycling or walking. To this end, an indicator expressing the compactness of the municipal territory () has been included, suggesting to calculate such parameter as the ratio between its minimum and maximum distance. Indeed, it sounds reasonable to consider that greater opportunities for the existence and the employment of soft mobility paths are present in more compact municipalities rather than in wider ones. Further indicators grouped in the territorial index are aimed at describing the sparsity of houses (), inhabitants (), the distance of between dwellings and hospitals, or other services (e.g., post offices, banks, education centers) ( and ), and the availability of commercial services throughout the analyzed territory (). An additional indicator has been included to consider the number of inhabitants per km2 () as a measure of the extent to which the population concentration per surface unit can influence the territorial offer in terms of resources, infrastructures, services, and so on.

The last index influencing mobility dependence is composed by four indicators investigating traffic flows both among the examined municipalities and to the different services, with a major focus on the medical ones. As far as the former are concerned, the entity of intermunicipal connections () has been evaluated with respect to the total amount of observed transfers, assuming that journeys are performed using motorized private or public means of transport when covering a distance which is larger than the maximum extent of the considered municipal territory. In regard to the latter, two more indicators ( and ) have been included in the index concerning traffic relations to account for the number of trips towards, respectively, hospitals and other services (e.g., post offices, banks, education centers) as compared to the total amount of transfers. Finally, as anticipated, the intensity of trips towards specialized healthcare centers () has been estimated confronting the number of registered accesses to specialist visits with the total amount of requests for medical examinations. The joint analysis of indicators concerning intermunicipal transfers and those leading to specialized medical centers enables the attainment of insights about seniors’ mobility derived by healthcare needs. Similarly to the case of intermunicipal connections, specialized medical hubs are supposed to be situated outside the residential areas and, thus, their access is performed employing motorized vehicles. Therefore, it can be concluded that such index is intended to capture the volume of displacements that are inevitably carried out using motorized mobility solutions.

In summary, the four indices illustrated above permit, on one side, to quantify the availability of the elderly of private and public transport alternatives and, on the other side, to capture their need of motorized and non-motorized transfers.

An analogous approach has been adopted to define the elements composing the risk index and their relative indicators. Notably, the risk index consists of two indices referring to the following aspects:

- (E)

- Private mobility vulnerabilities;

- (F)

- Social factors.

As regard the former, possible fragilities affecting private mobility in the examined territories have been expressed through a few indicators referring to the possession of the driving license among men and women ( and ) confronted to the total population of the same gender, the average age of vehicles (), and the average age of driving licenses among male and female according to a certain age range ( and ).

With respect to social factors, two indicators have been taken into consideration, i.e., the aging indicator (), which defines the percentage of the population over 65 years old, and a femininity indicator (), which accounts for the numerosity of women in the whole population.

The implementation of gender-related indicators plays a significant role in the construction of the composite index due to the fact that the distribution of driving licenses and of the number of inhabitants per age remarkably varies between male and female. Indeed, statistical data reveal that the majority of older people are women, while driving authorizations are possessed mostly by men. The combination of these two tendencies entails a non-negligible reduction in private mobility per household as age increases. In this regard, as underlined in [38], recognizing gender gaps in elderly mobility is essential to support transport planners and policy makers in the development of dedicated initiatives that can actually address the needs of specific target groups.

The selection of information relevant to the examined topic has resulted in the construction of the index reported in Equation (1):

where is the index of seniors’ critical mobility dependence for the municipality i and and are, respectively, the mobility dependence index and the risk index for the same municipality. More in detail, in accordance to the denomination used in the description of the various components, the formulation of the former is indicated in Equation (2):

where A, B, C, and D, and , , , and are, respectively, the weights for the indices and the relative indicators. With regard to the risk index, it has been defined as shown in Equation (3):

where E and F, and and are, respectively, the weights for the indices and the relative indicators.

Since data necessary to feed the equations has different measurement units, a normalization process has been carried out to make information comparable. Notably, a linear normalization has been adopted associating a value equal to 100 to the most outstanding municipality with respect to a certain indicator, based on a direct scale of performances. On the contrary, when referring to an inverse scale, the same mark has been assigned to the worst-performing municipality in relation to the indicator at hand. In both cases, the performances of a specific municipality against the remaining indicators have been then proportionally reparametrized.

The prioritization of the indices and the relative indicators have been performed using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method, which is a multi-attribute decision-making technique developed by professor T.L. Saaty in the 1970′s [39]. According to the principles of such method, a dedicated hierarchical decision model has been created to determine the weights of both the components of the index of seniors’ critical mobility dependence index, i.e., the mobility dependence index and the risk index. In addition, a panel of experts belonging to the social, economic and transport context of the study area has been actively engaged in the evaluation procedure, by administering them a structured questionnaire. Indeed, such survey was aimed at collecting preferences of the experts on the relative importance of the considered decision elements using pairwise comparisons. For this purpose, the Saaty’s 1–9 rating scale has been adopted and the consistency among judgements has been guaranteed by limiting the inconsistency ratio below the recommended threshold value of 0.1 [40]. A similar assessment approach has already been used in further multi-actor transport-related studies as reported in [41,42].

As a last step, the final values of all indices have been further normalized to obtain the corresponding rankings.

4. Case Study

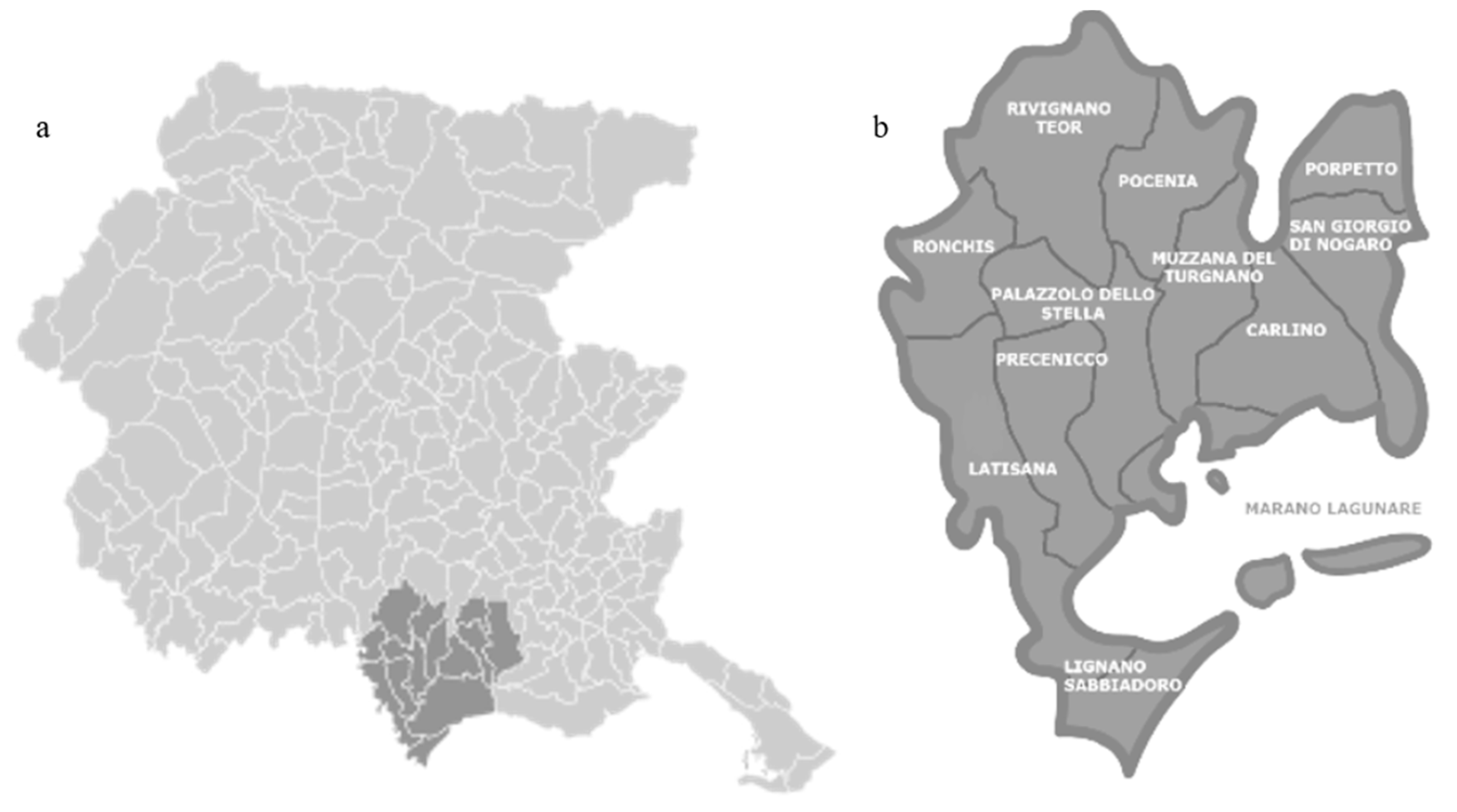

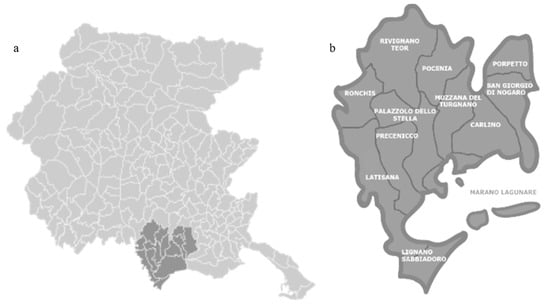

The composite index developed to assess the criticality degree of seniors’ mobility dependence has been applied to the case study of the coastal municipalities of Friuli, which is a part of the northeastern Italian Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia (Figure 2a). Notably, as reported in Figure 2b, the following nine municipalities are included: Carlino, Latisana, Lignano Sabbiadoro, Marano Lagunare, Muzzana del Turgnano, Palazzolo dello Stella, Pocenia, Porpetto, Precenicco, Rivignano Teor, Ronchis, and San Giorgio di Nogaro. Even though those municipalities fall under the same categorization at administrative level, they remarkably differ among each other in territorial extension, residential sparsity and land use destination. With respect to this latter characteristic, significant disparities occur between the municipalities located on the coast and the ones in the hinterland, as transport dynamics are influenced, respectively, by tourism seasonality and by agricultural and industrial activities. However, in general terms they all represent rural municipalities which, according to statistical data, are associated by common phenomena like the low population density, demographic decline, aging of inhabitants, decrease in service supply, and capillarity of the road network and of its related public transport services. Indeed, the population density of only three out of these nine municipalities is more than 200 inhabitants/km2.

Figure 2.

Considered municipalities of Friuli Venezia Giulia Region (a) and their denomination (b).

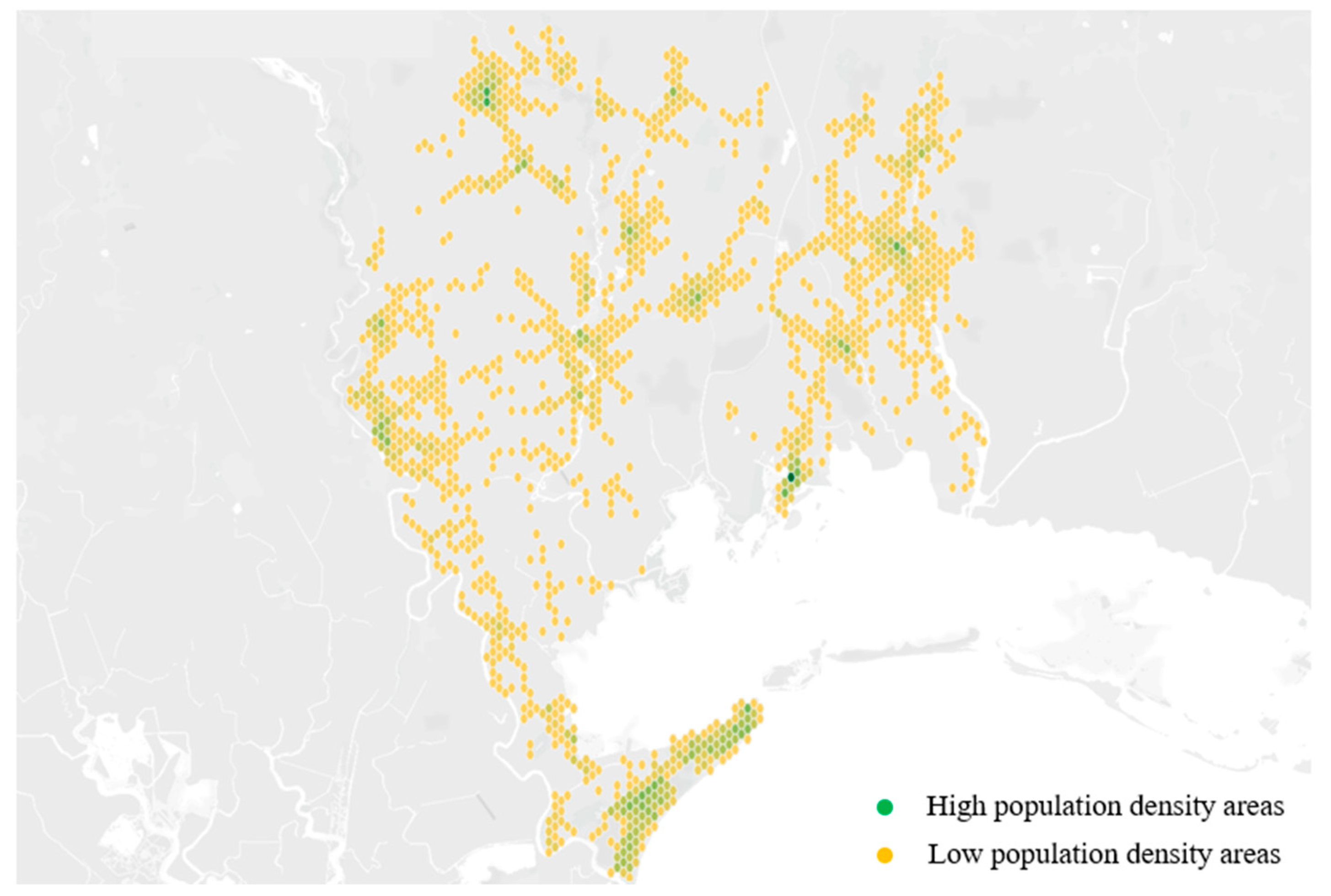

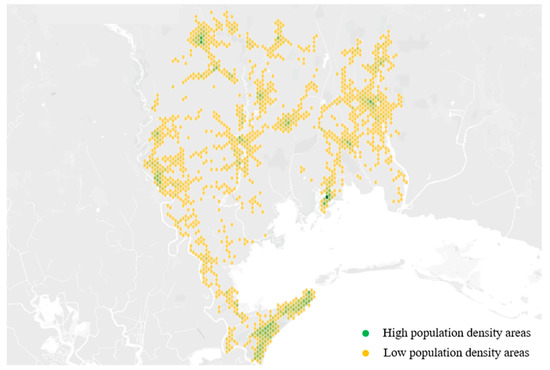

Figure 3 shows the residential distribution over the considered territory. The color of dots ranges from yellow to green with the increase in the number of houses per km2. It can be noted that greater values of such parameter are registered near the center of the most populated municipalities, and that the distribution of dwellings is not uniform over the territory but it follows the road network configuration.

Figure 3.

Residential distribution over the study area.

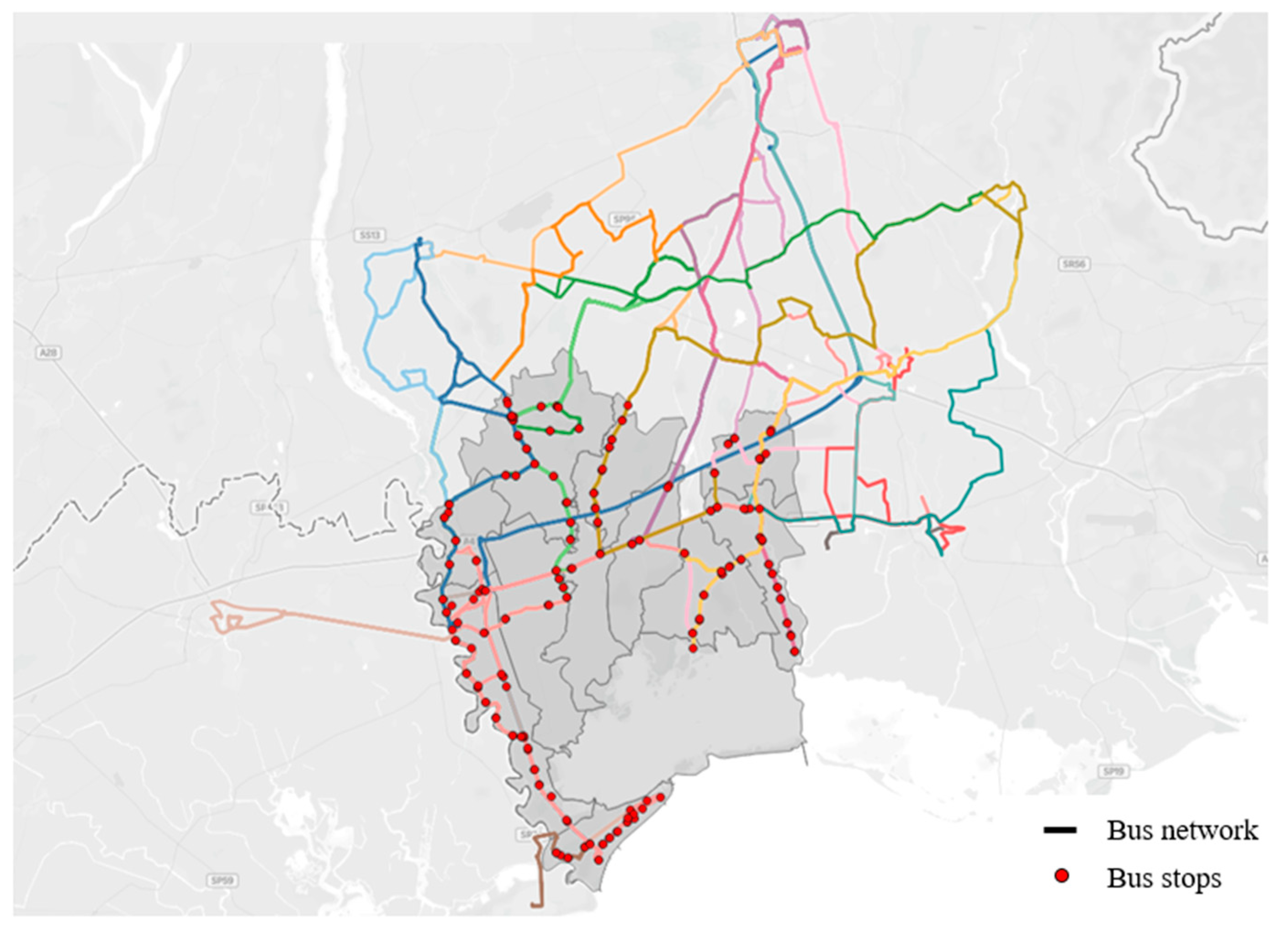

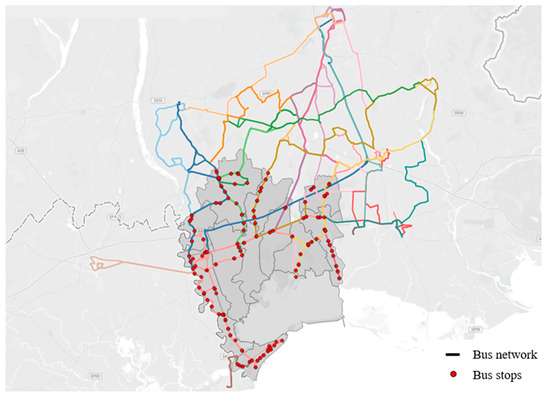

As regard the spatial capillarity of the public transport network, Figure 4 shows the itineraries of bus lines (differently colored lines) and the bus stops (red dots) in the considered study area.

Figure 4.

Public transport network in the study area.

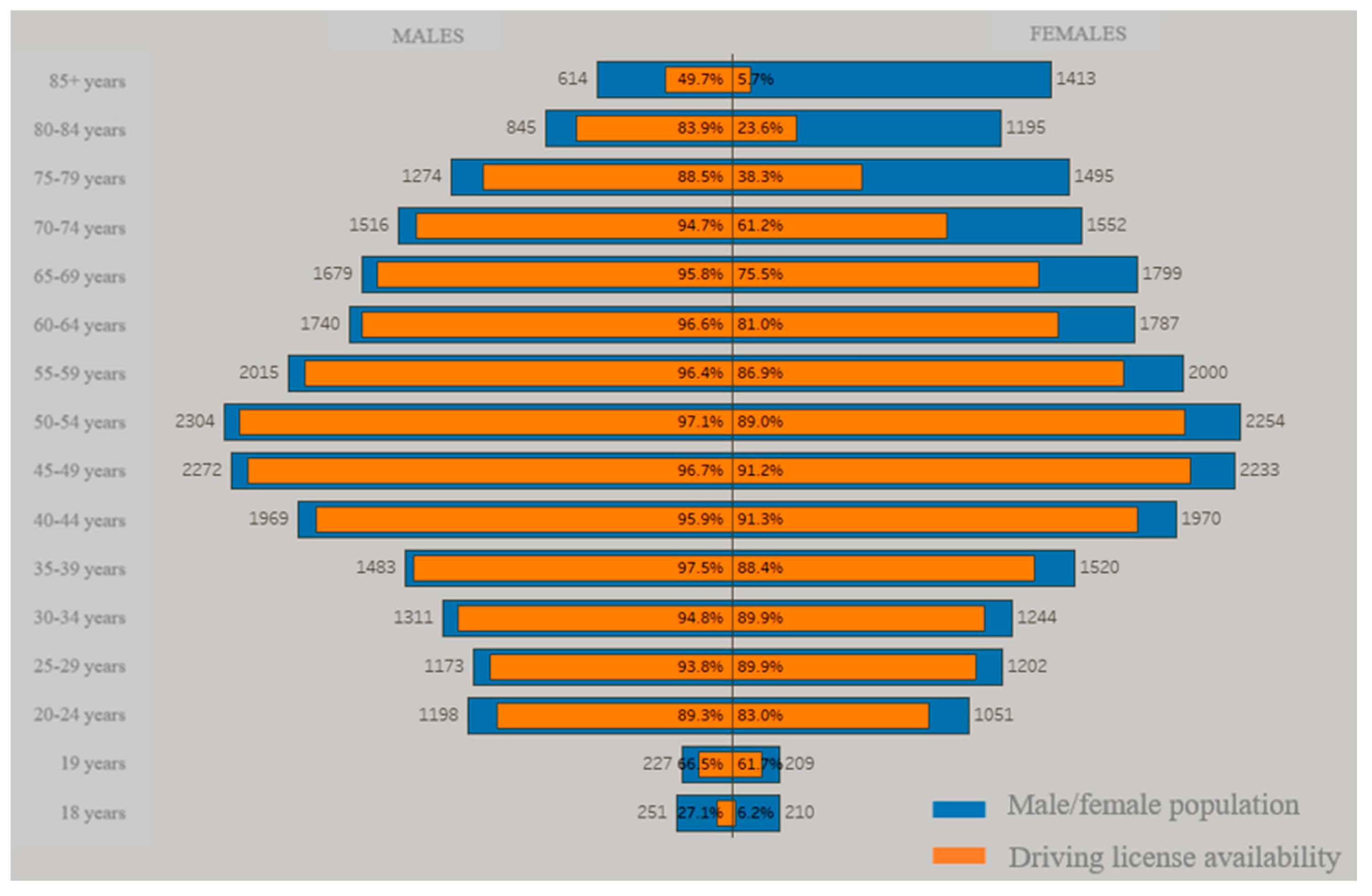

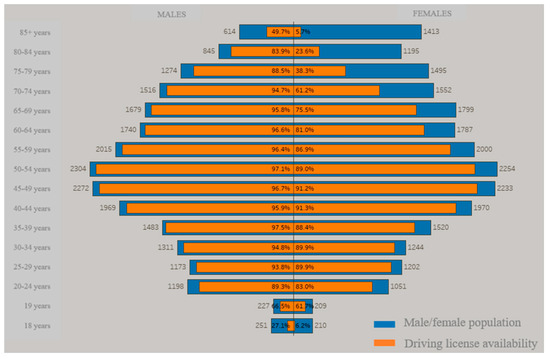

Figure 5 consists of a pyramid chart which displays two interesting aspects:

Figure 5.

Age and driving license distributions.

- -

- the distribution of male and female with respect to different age segments (blue bars);

- -

- the corresponding availability of driving licenses (orange bars).

It is quite evident that the older the age, the lower is the proportion of driving licenses over the population, especially for females.

To complete the context overview of the study area, it is underlined that some issues exist regarding the movements both to services and hospitals, and inside each municipality, especially without using any motorized vehicle.

The insights retrieved from the consulted data, which are partially represented in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, definitely motivate the validity of the selected case study for the application of the proposed index. Indeed, the great sparsity of dwellings, the limited number of available bus lines and stops, the high percentage of old people and of non-drivers among senior females, and the poor accessibility to service facilities make the inhabitants of the considered municipalities very vulnerable to mobility dependence issues.

5. Results and Discussion

The methodology included in the previous chapter has been applied to the examined case study. Notably, the judgements expressed by the engaged panel of experts on the relative importance of indices and indicators through pair-wise comparisons have been implemented in the respective decision model, enabling the computation of the weight of each element. Such resulting priorities are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Weights of indices and indicators.

Together with public data and information available on request about the performances of municipalities according to the selected indicators, such priorities have been implemented in the Equations (1)–(3) in order to compute the index of seniors’ critical mobility dependence. Final results are shown in an analytical form in Table 3. The value of the aggregated index suggests a ranking of the municipalities with respect to the criticality level of mobility dependence of the elderly, which decision makers can exploit to develop and assess improvement interventions and policies.

Table 3.

Values of the proposed indices.

High values in the MDI indicate that a certain municipality is characterized by great private and public mobility capabilities, and, at the same time, by a significant need of transfers to access the examined services. On the contrary, low values in the MDI suggest poor mobility capabilities over the territory of the considered municipality, but also a limited need of transfers thanks to the availability of services in close proximity. Intuitively, high values in the RI mean that a municipality presents a great risk of reduced users’ mobility capabilities, with reference to both individual and collective transport solutions, while low values in the RI express the low risk for a territory of having inhabitants losing their mobility capabilities. Therefore, synthesizing the contribution of the MDI and the RI, high values in the CMDI are associated to territories where the users’ mobility capabilities are fundamental for the fruition of services but they are severely threatened by risk factors, whereas low values in the CMDI stand for areas in which services are more accessible and seniors’ mobility capabilities are less influenced by risk factors.

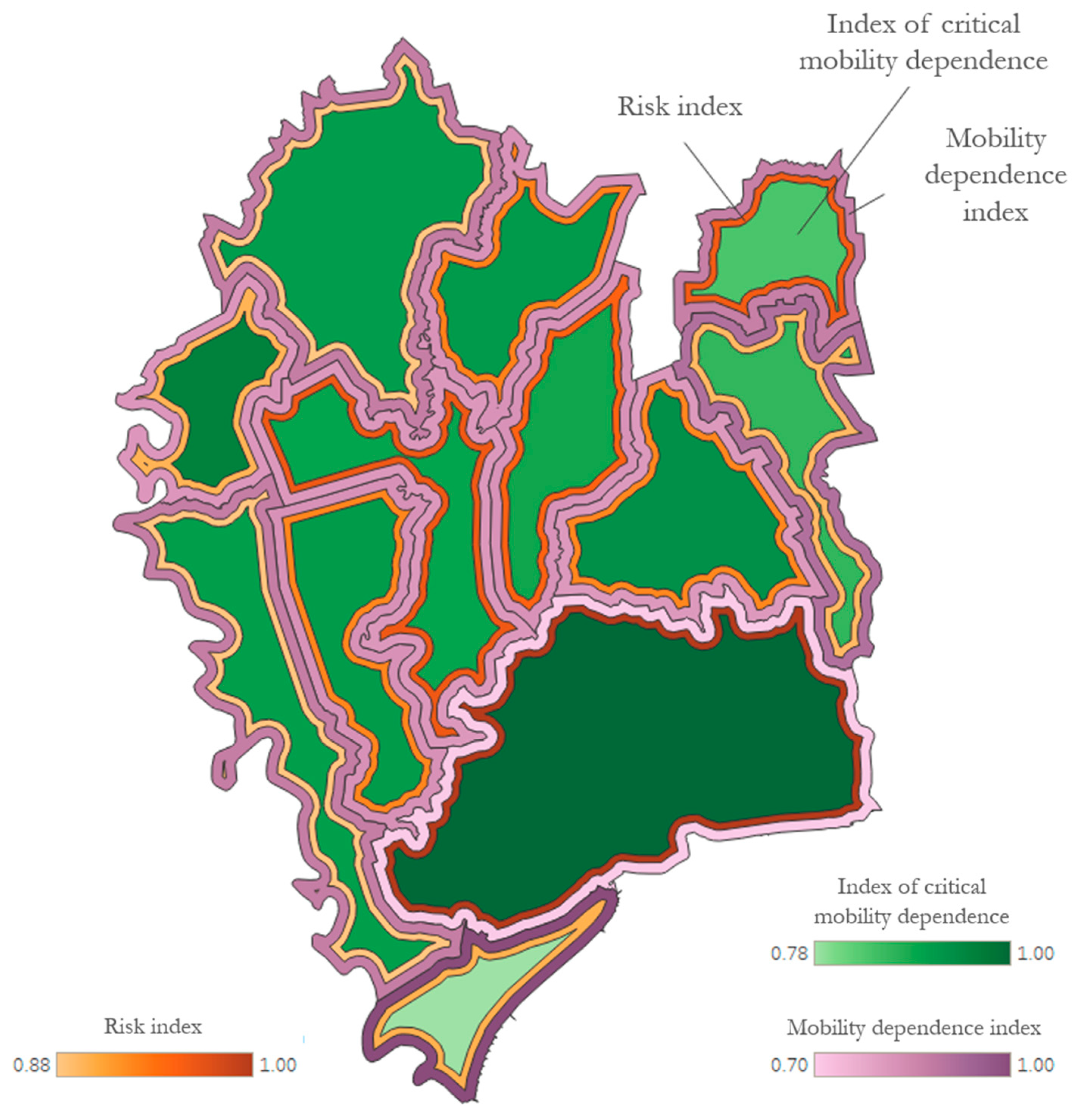

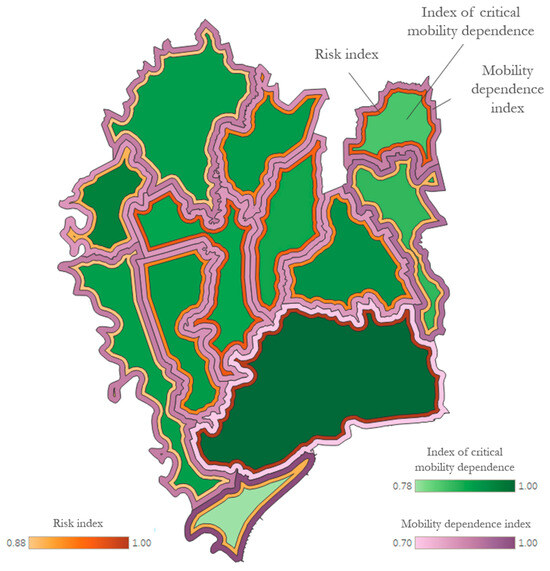

As reported in Figure 6, results have been graphically represented to support their analysis, even in light of effectively delivering the outcomes to decision makers. More in detail, in Figure 6 the three proposed indices are shown for each municipality in the following way: the color of the outer border illustrates the mobility dependence index, the color of the inner border refers to the risk index, while the color of the area enclosed by this latter indicates the index of critical mobility dependence. It can be observed that the worst situation occurs in the municipality of Marano Lagunare, where both the mobility dependence index and the index of critical mobility dependence assume high values. Such condition is due to both its unfavorable position with respect to hospitals and the primary services, and to critical values in population indicators. Figure 5 enables the comparison among all municipalities, which stresses their great diversity, as mentioned above.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the developed indices.

The analysis of results can contribute to the identification of the most critical situations in terms of dependency from the use of motorized vehicles, other than some weaknesses referred to the use of private cars or to public transport availability. These factors depend on social, economic and land use aspects which generate mobility needs and which can represent critical issues for older people. In addition, the developed index of critical mobility dependence can be used for the assessment of scenarios of interventions and, therefore, to determine the effects of different incentive policies on users. The definition of scenarios needs to consider the local territorial dynamics through the consultation of the main stakeholders and the analysis of transport processes, and to include also the employment of technological solutions to share mobility information for a better arrangement of services.

6. Conclusions

In a context where the mobility of elderly people may become a problematic issue due to increasing aging and limited public transport service capillarity, the proposed composite index may contribute to the identification of the most critical situations in a given study area. Notably, on one hand, it allows to consider multiple dimensions of mobility and of the territory in a synthetic and yet quite exhaustive way, and, on the other hand, it is based on data which is publicly available and continuously collected. In this regard, such data were preferred over other information in order to ensure transferability and repetitiveness over time. The suggested index has been developed with the objective of creating a ranking of rural areas in terms of existing criticalities for seniors’ mobility, which can be used to define a priority list of measures to increase their life quality. The results of the study are intended to be shared with local service operators and institutions to define possible scenarios of interventions and, thus, to assess the effects of different policies on older people. The provision of incentives may address the modernization of the car fleet, the driving license renewal for female users, the creation of flexible transit services, and a more age-friendly access to healthcare services. In this regard, both a more capillary distribution of medical services and changes in the visit reservation system, are meant to promote independent access to hospitals among the elderly. Last but not least, some guidelines for land use management may arise from the proposed analysis, which even further segments of the population can take advantage of. However, other than suggesting the lines of actions just mentioned, a greater availability of data regarding both the transport offer and the personal characteristics of seniors could assist policy makers in better understanding the relationship between mobility and the evolution of the social system in a certain area. For instance, on one hand, feeding the composite index with more accurate information on the extensions of cycle paths and on the actual supply of alternative transport services like taxis and car rental with driver, could give useful insights of seniors’ transfer potential and, thus, highlight possible necessary interventions. On the other hand, a deeper investigation on the technological skills of the elderly could provide decision makers with a more precise overview of the capability of old people to access services, both using modern vehicles or through digital platforms, indicating a specific direction for practical countermeasures.

With respect to existing contributions, the strengths of the study consist, first, in the comprehensiveness of the suggested index, given by the variety of the dimensions included in the equation, and, secondly, in the adoption of a robust method to prioritize the considered components. In contrast, the main limitations of the study are related to a few methodological aspects, that should be overcome in order to enhance the validity of the developed formulation and the transferability of the approach to further applications. Indeed, future developments of the proposed study may focus, on one side, on the definition of a more articulated normalization procedure for the performances of the municipalities against the selected indicators and, on the other side, on verifying whether and how this approach may be adopted to face seniors’ mobility issues also in the peripheral areas of large cities. Additional research may lead to the definition of some ranges for the composite index values, which could be associated to a corresponding level of service of accessibility according to the seniors’ perspective. Finally, further investigations should evaluate the feasibility of providing the latest environmentally-sustainable mobility solutions to the elderly, in line the ultimate goal which the transport sector strives for.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L. and P.Z.; methodology, G.L. and P.Z.; validation, P.Z.; formal analysis, P.Z. and C.C.; investigation, P.Z.; writing – original draft preparation, G.L. and C.C.; writing – review and editing, C.C.; visualization, P.Z. and C.C.; supervision, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Regional Department of Infrastructure and Territory—Regional and local public transport service of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region for sharing the data which fed the equations of the developed composite index.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Paolo Zaramella collaborated with the company Deimos Engineering Srl and he is now retired. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Therefore, all the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Aguiar, B.; Macário, R. The need for an Elderly centred mobility policy. Transp. Res. Proc. 2017, 25, 4355–4369. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shergold, I.; Parkhurst, G. Transport-related social exclusion amongst older people in rural Southwest England and Wales. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, E.; Menec, V.; Keefe, J. Age-Friendly Rural and Remote Communities: A Guide; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Kaplan, M.A.; Inguanzo, M.M. The social, economic, and public health consequences of global population aging: Implications for social work practice and public policy. J. Soc. Work Glob. Community 2017, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bernetti, G.; Longo, G.; Tomasella, L.; Violin, A. Sociodemographic groups and mode choice in a middle-sized European city. Transp. Res. Rec. 2008, 2067, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. Methods for constructing composite indices: One for all or all for one. Riv. Ital. Econ. Demogr. Stat. 2013, 67, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, S.C.; Porter, M.M.; Menec, V.H. Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odufuwa, B.O. Vulnerability and mobility stress coping measures of the aged in a developing city. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 13, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Khalek, F.A.; Barthod, C.; Marechal, L.; Benoit, E.; Perrin, S.; Godiard, B. Toward a person-centred, multidisciplinary method to assess the vulnerability of the elderly. In JETSAN 2021—Colloque en Télésanté et Dispositifs Biomédicaux—8ème Édition; Université Toulouse III—Paul Sabatier [UPS]: Toulouse, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Awuviry-Newton, K.; Ofori-Dua, K.; Newton, A. Understanding transportation difficulty among older adults in Ghana from the perspective of World Health Organisation’s healthy ageing framework: Lessons for improving social work practice with older adults. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 51, 416–436. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, N.; PourJafar, M.; Soltani, A.; Ranjbar, E. A Systematic Review of the Factors Affecting Elderly Mobility in Urban Spaces. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Urban Plan. 2023, 33, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Busari, A.A.; Oluwafemi, D.O.; Ojo, S.A.; Oyedepo, J.O.; Ogbiye, A.S.; Ajayi, S.A.; Adegoke, D.D.; Daramola, K.O. Mobility dynamics of the elderly: Review of literatures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 640, 012077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Páez, A. The mobility of older people: An introduction. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, D.; Attard, M.; Ison, S. Old age: What are the main difficulties and vulnerabilities in the transport environment? In Transport, Travel and Later Life; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Wachs, M.; Levy-Storms, L.; Brozen, M. Transportation for an Aging Population: Promoting Mobility and Equity for Low-Income Seniors; Mineta Transportation Institute: San José, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Böcker, L.; van Amen, P.; Helbich, M. Elderly travel frequencies and transport mode choices in Greater Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Transportation 2017, 44, 831–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, G.; Fields, N.; Cronley, C.; Parekh, R.; Magruder, K. Ageing in a low-density urban city: Transportation mobility as a social equity issue. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, A.; Hine, J. Rural transport–Valuing the mobility of older people. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, J.W. Aging and mobility in rural and small urban areas: A survey of North Dakota. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2011, 30, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Yu, Z. Investigating mobility in rural areas of China: Features, equity, and factors. Transp. Policy 2020, 94, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Strawderman, L.; Adams-Price, C.; Turner, J.J. Transportation alternative preferences of the aging population. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M.; Burrow, M. An investigation into the factors influencing travel needs during later life. J. Transp. Health 2018, 11, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Wretstrand, A. What’s mode got to do with it? Exploring the links between public transport and car access and opportunities for everyday activities among older people. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 14, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelaki, E.; Maggi, E.; Crotti, D. Mobility impact and well-being in later life: A multidisciplinary systematic review. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 86, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra Muñoz, J.; Duboz, L.; Pucci, P.; Ciuffo, B. Why do we rely on cars? Car dependence assessment and dimensions from a systematic literature review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, K.; Moridpour, S.; De Gruyter, C.; Saghapour, T. Elderly sustainable mobility: Scientific paper review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davern, M.; Winterton, R.; Brasher, K.; Woolcock, G. How can the lived environment support healthy ageing? A spatial indicators framework for the assessment of age-friendly communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugel, E.J.; Chow, C.K.; Corsi, D.J.; Hystad, P.; Rangarajan, S.; Yusuf, S.; Lear, S.A. Developing indicators of age-friendly neighbourhood environments for urban and rural communities across 20 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.; Norman, P. Quantifying service accessibility/transport disadvantage for older people in non-metropolitan South Australia. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2018, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutley, S. Indicators of transport and accessibility problems in rural Australia. J. Transp. Geogr. 2003, 11, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Benevenuto, R.; Caulfield, B. Identifying hotspots of transport disadvantage and car dependency in rural Ireland. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.; Durán-Rodas, D.; Pajares, E. Exploring a quantitative assessment approach for car dependence. J. Transp. Land Use 2023, 16, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutley, S.D. Accessibility, mobility and transport-related welfare: The case of rural Wales. Geoforum 1980, 11, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazinić, B.R.; Jović, J. Mobility and transport potential of elderly in differently accessible rural areas. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Yao, M.; Ritchie, S.G. Gender differences in elderly mobility in the United States. Transp. Res. A Pol. 2021, 154, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini, C.; Longo, G.; Padoano, E.; Zornada, M. An AHP-based method to assess the introduction of electric cars in a public administration. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2017 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Milan, Italy, 6–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caramuta, C.; Giacomini, C.; Longo, G.; Montrone, T.; Poloni, C.; Ricco, L. Integration of BPMN modeling and multi-actor AHP-aided evaluation to improve port rail operations. Transp. Res. Proc. 2021, 52, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).