Abstract

The Maldives is one of the few atoll countries in the world, with an average elevation of just 1.5 m above sea level. The country faces the possibility of submersion, without adequate adaptation measures, if the current trends persist. The present study aimed to examine the societal context of observed differences in perceptions regarding climate change impacts in the two locations in atoll islands of the Maldives: Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi, situated in the southernmost and northernmost islands within the country, respectively. A questionnaire survey was conducted at both locations, with follow-up semi-structured interviews. With regard to Hithadhoo, a higher percentage of residents recognize the impacts of climate change and sea level rise (SLR) and are more likely to take individual actions and encourage government action. Residents of Kulhudhuffushi reported fewer observed impacts of climate change and SLR, with a significant majority not taking specific actions or relying more on broader measures. These findings highlight the differences in perceptions regarding and responses to climate change impacts between the two areas, which can be attributed to different environmental conditions, awareness levels, and socioeconomic factors, including culture and values. This also indicates the need for tailor-made strategies and policies for climate change adaptation in different regions of a single nation.

1. Introduction

The Maldives are one of the few atoll countries in the world, with land comprising approximately 1192 coral islands formed around 26 natural ring-like atolls spread over 90,000 square kilometers. With an average elevation of just 1.5 m above sea level, the Maldives face the possibility of submersion if current trends persist, requiring for adaptation measures where possible. The present study aimed to examine the societal context of observed differences in perceptions regarding climate change impacts in an administrative district and a city of the Maldives, Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi, located in the southernmost and northernmost islands within the country, respectively, to seek possible ways to improve the design and implementation of these measures. The hypothesis is that socio-economic, cultural and educational backgrounds play critical role in how people perceive the climate change impacts; however, currently, these aspects are not taken into full consideration. Despite the significance of tailor-made approaches to climate change adaptation in general, there are gaps in understanding and analyzing the different climatic, geological, and oceanographic characteristics of different atolls in the Maldives, the perceptions of residents and stakeholders, and appropriate adaptation measures that take into consideration these diverse conditions and perspectives. In-depth interviews with informants showed that there were distinct differences in perceptions regarding and responses to climate change impacts between the two areas studied due to different environmental conditions as well as awareness levels and socioeconomic factors, including cultures and values. Local climate change adaptation responses should consider diverse perceptions and the social constructs that form these views.

The Maldives are classified as a high-income country, with a GDP per capita of USD 24,809 in 2023 [1]. The national population was 515,132 in 2022 (composed of 382,639 Maldivian population and 132,493 foreigners) [2]. The country also faces the risk of medium-to-long-term sea level rise (SLR). Between 1992 and 2015, the annual averaged just under 4 mm. It has been suggested that this rate could increase to 6–12 mm annually under severe warming scenarios, potentially leading to an increase of 0.5–0.9 m by 2100. Without adaptation, coastal flooding can damage up to 3.3% of the total assets by 2050 during typical 10-year floods [3]. Therefore, the SLR and related flooding are major concerns for the Maldives. Maldives has a warm and humid tropical monsoon climate with an annual mean temperature of 28 °C [4].

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggests that the coastal impacts of SLR can be avoided by preventing new developments in exposed coastal locations. The Panel highlights that for existing developments, an arrangement of near-term adaptation options exists, including (i) engineered, sediment-based, or ecosystem-based protection; (ii) accommodation and land-use planning to reduce the vulnerability of people and infrastructure; (iii) advance through land reclamation; and (iv) retreat through planned relocation or displacements and migrations due to SLR [5]. According to Nakayama et al. (2022), the following four alternatives are identified as measures to address SLR in atolls [6]: (i) migration to developed countries, (ii) migration to other island states, (iii) land reclamation and raising, and (iv) the development of floating platforms.

The national policies of the Maldives to address climate change are outlined in the National Adaptation Program of Action (NAPA 2006) [7], Maldives Climate Change Policy Framework (MCCPF 2015–2025) [8], Update of Nationally Determined Contribution of the Maldives in 2020 [9], and Climate Emergency Act (Act No. 9/2021) ratified in 2021. The Maldivian Government is developing a new National Adaptation Program of Action (NAPA) with assistance from the UN Environment Program [10]. The Climate Emergency Act stipulates actions to address climate emergencies resulting from the rapid acceleration of the severity of the repercussions of climate change. It introduces an overarching legal framework, rules, regulations, and guidelines for addressing the adverse impacts of climate change, including monitoring, reporting, and verification, thus ensuring the sustainability of natural resources, overcoming negative impacts, and allocating funds for renewable energy sources. The Act also includes a complete framework for the ambitious plan of the Maldives to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2030 [11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Survey

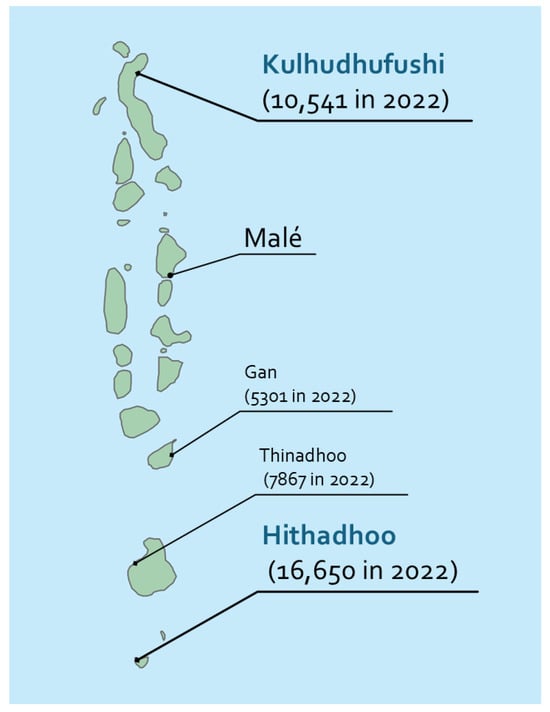

The Sasakawa Peace Foundation (SPF), Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation of Japan (GIF Japan), Maldives National University (MNU), and Tohoku University conducted a survey between December 2023 and January 2024 targeting four atolls where campuses of Maldives National University (MNU) are present: Kulhudhuffushi (population in 2022: 10,541), Gan (population: 5301, located in Haddhunmathi Atoll), Hithadhoo (population: 16,650, part of Addu Atoll), and Thinadhoo (population: 7867) [12]. There are 21 administrative divisions in the Maldives, including 17 atolls and four cities. City status, which requires economic growth and 10,000 or more residents, was conferred on four cities: Malé, Fuvahmulah, Kulhudhuffushi, and Addu City [13]. Addu City (total area of 15 km2) is a city on the Addu Atoll (local administrative code Seenu Atoll), the southernmost atoll of the archipelago, and the second-largest urban area in the country in terms of population. Hithadhoo is the primary administrative area among the six districts in Addu City, along with Maradhoo-Feydhoo, Maradhoo, Feydhoo, Meedhoo and Hulhudhoo. Kulhudhuffushi is the capital of Haa Dhaalu Atoll administrative division on Thiladhunmathi Atoll in the north of the Maldives.

This study analyzed three specific questions from a survey previously mentioned regarding resident perceptions regarding climate change and SLR. The three questions and their response options are listed in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. The entire survey examined the perceptions of residents outside of Greater Malé region of Hulhumalé, an artificial island in the Maldives, as a potential destination for domestic migration in the face of climate change and the results of this overall survey is analyzed in another article.

Table 1.

Items in the questionnaire.

Table 2.

Responses to the question “Impacts of climate change that you observe in your environment”.

Table 3.

Responses to the question Impacts of sea level rise that you observe in your environment.

Table 4.

Responses to the question Best way to avoid your personal risks under the threat of sea level rise.

The sample size was allocated proportionally based on the population, resulting in a total of 398 respondents across the four regions. The sample size and population distribution across atolls were determined through a systematic approach based on statistical and practical considerations. The total sample size of 398 respondents was calculated using a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% for the total population of the four surveyed regions (approximately 40,359 people). This sample size ensures statistical validity while remaining manageable for the field survey implementation. The questionnaire was validated by experts’ review, piloting and subsequent revisions and adjustments in terms of language and content. Trained enumerators from the MNU administered the survey in person to Maldivian nationals aged 18 years and older. The enumerators presented the questions orally, recorded the responses on-site, and provided clarifications when required to ensure accurate responses. The collected data were integrated and analyzed for this study. Statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.4.0). Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the differences between the two groups, and statistical significance was determined using the fisher.test() function in R. Fisher’s exact test was the most appropriate statistical test for this analysis for several important reasons. Unlike chi-squared tests, which rely on large sample approximations, Fisher’s exact test calculates exact probabilities and remains reliable even with small cell counts, which was the case for several response categories in our survey.

2.2. Follow-Up Interviews

Based on the results of the aforementioned questionnaire survey, significant statistical differences were observed in the responses from residents in Kulhudhuffushi, the northernmost location, and Hithadhoo, the southernmost location, among the four surveyed areas. Kulhudhuffushi and Hithadhoo in Addu City were selected because of their large population size of more than 10,000, after the capital Malé and Fuvahmulah. Based on the unique characteristics of oceanographic, geomorphological, ecological and socioeconomic features, island typology in the Maldives is suggested as the following: complete-protection urban islands such as Malé and Hulhumalé; high-protection rural islands; medium-protection rural islands; and low-protection rural islands. In addition, relatively uncommon islands, lagoon islands, natural islands, agricultural islands and resort islands, are categorized [3]. Kulhudhuffushi and Hithadhoo in Addu City represent the typical island types classed as medium-protection rural islands, outside of Greater Malé Region, worth being analyzed; these are characterized as rural rim islands with low-density housing and coastal protection along a significant portion of the premier such as the lagoon or ocean-facing side [3].

In the modern era in Addu Atoll, the British bases were first established on Gan during the Second World War as part of the Indian Ocean defenses. In 1956, the British established a Royal Air Force base on Addu as a strategic outpost during the Cold War, after they could not use the bases in Sri Lanka [14]. There were around 600 personnel permanently stationed in Addu, with up to 3000 during peak periods. Causeways were built by the British, connecting Feydhoo, Maradhoo and Hithadhoo islands. In the 1960s, under the leadership of Abdulla Afif Didi, who was elected president of the ‘United Suvadive Republic’, comprising Addu, Fuvahmulah and Huvadhoo, declared independence from the Maldives, which resulted in deployment of an armed fleet by Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir of the central government in Malé, who suppressed the rebellion. In 1976, the British force left, with the legacy of an airport, large industrial buildings, and a number of unemployed residents with good English skills [14]. This coincided with the development of the tourism sector in the late 1970s, which provided new employment opportunities for people from Addu in resorts and tourist shops in Malé. Currently, the major economic activities of Hithadhoo include fishing, masonary, business, carpentry and shipping. Hithadhoo is also home to Eydhigali Kilhi and Koattey protected area, encompassing one of the largest wetlands in the Maldives.

Kulhudhuffushi has been a key trading hub due to its large natural harbor, attracting merchants from nearby atolls. It was also known for its boat-building industry and skilled craftsmen, such as rope making and blacksmith works. The island played a significant role in regional politics and administration. In the past, it served as a center for governance in the northern Maldives [15]. Kulhudhuffushi was also famous for its mangrove ecosystem, which supported traditional livelihoods such as coir rope making and fishing [15]. In recent years, the island has undergone rapid development, including the construction of an airport in 2019, which improved connectivity, while the development led to the loss of its mangrove swamps, raising environmental concerns and civil protests against it.

To clarify the reasons for these differences, a semi-structured interview survey was conducted in August 2024 by the SPF and GIF Japan with support from the MNU. A total of 17 participants were interviewed, with an aim to interpret the reasons behind the different perceptions expressed in these two locations. The informants were selected by applying the snowball sampling method to cover broad representations of gender, age, occupation, and engagement in these two sites being studied. The series of interviews were qualitative in nature. The attributes of the interviewees are listed in Table 5. The interviewees were mostly associated with MNU, and were either enrolled as students, administrative officers, or faculty members, who had a profound understanding of the situation in these locations based on first-hand information and observations. Some informants lived in both places or were frequent visitors of both locations, as indicated in Table 5. The interviews were conducted anonymously, and the data were processed to ensure that no individuals could be identified. During the interviews, some questionnaire survey results were shared with the interviewees, who were encouraged to freely express their opinions regarding why the responses differed between the two regions. Climate and weather data were collected and disseminated by the Maldives Meteorological Service (MMS) through its five monitoring stations (Hulhule, Hanimaadhoo, Kadhdhoo, Kaadehdhoo and Gan) in the country. This study aims to supplement these observations by providing local perceptions on the actual impacts of climate change and potential solutions, which are grounded on the local realities.

Table 5.

Attributes of informants in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Survey

The survey results from Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi show notable differences in how residents of these two areas perceive and experience the impacts of climate change.

In Hithadhoo, a significant majority (97 respondents) reported experiencing increasing temperatures and heatwaves, whereas in Kulhudhuffushi, only 27 respondents reported the same issue, with most (93) not noting this impact. This contrast suggests that geographical or urban development differences may influence the experience of climate change at these locations. Figure 1 shows a map with details of Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi.

Figure 1.

Map showing details of Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi [11,16].

Regarding the impact of SLR, beach and coastal erosion emerged as the most commonly observed effects across both locations. However, this was more prominent in Hithadhoo (104 respondents) than in Kulhudhuffushi (23 respondents). Other SLR impacts, such as the salinization of groundwater, surge waves, and king tides, were reported by a smaller but notable portion of respondents in Hithadhoo (42–48 respondents), whereas very few respondents in Kulhudhuffushi (four to eight respondents) reported these issues.

Regarding adaptation strategies, interesting differences in how residents preferred to address SLR risks were observed. In Hithadhoo, the most popular response was encouraging stronger government measures (73 respondents), followed by building seawalls (35 respondents). In contrast, Kulhudhuffushi residents showed a stronger preference for rebuilding houses to increase the elevation (41 respondents), whereas few supported government intervention (four respondents) or seawall construction (three respondents). Notably, more respondents in Kulhudhuffushi (31) compared to Hithadhoo (11) provided ‘no specific action’ as their response, indicating possibly different levels of concern or urgency about SLR between the two study areas.

Other climate change impacts, such as water shortages, flooding, and biodiversity loss, were reported by relatively few respondents in both areas. However, more residents in Hithadhoo consistently reported experiencing these issues than those in Kulhudhuffushi. This pattern indicates that either Hithadhoo is more vulnerable to climate change impacts or its residents are more aware of and concerned about these issues.

3.2. Interview Survey

3.2.1. Impacts of Climate Change

Hithadhoo

- Increasing temperatures: Residents reported a noticeable increase in temperature in Hithadhoo. This change is attributed to deforestation and the urban heat island effect caused by development and construction. Removing large trees that lined roads contributed to a barren landscape, leading to higher temperatures.

- Shortage of water: Although Hithadhoo previously experienced water shortages, particularly during certain times of the year when rainwater was depleted, the situation improved with the introduction of desalination plants and a shift away from reliance on rainwater and groundwater. However, perceptions regarding water quality persist, with residents often preferring bottled water despite tap water meeting WHO standards.

- Flooding: Flooding is a frequent problem in Hithadhoo, particularly in low-lying areas. However, recent infrastructure improvements, including the development of robust sewage systems, have significantly reduced the incidence of flooding.

- Strong winds, rough seas, and storm surges: Hithadhoo, owing to its geographical location, is more vulnerable to rough seas and storms than Kulhudhuffushi. Strong winds can cause property damage, including damage to rooftops and trees. Storm surges have also affected fishing industries. Despite this vulnerability, storm surges in the south are generally less significant and rarely cause major damage.

- Loss of biodiversity: Hithadhoo has experienced a significant loss of biodiversity, primarily due to deforestation for development and housing. Forests that once provided traditional medicine have been cleared, leading to a decline in medicinal plants. Although some residents noted a decrease in the number of birds, it is not perceived as a major issue compared to other locations such as Malé.

Kulhudhuffushi

- Increasing temperatures: Although residents of Hithadhoo perceived a significant increase in temperature, this observation was less notable in Kulhudhuffushi. However, certain areas, such as poorly managed pooled areas and reclaimed land with limited tree cover, experience noticeable heat. The presence of more natural environments and vegetation in Kulhudhuffushi may have mitigated the temperature increase observed at Hithadhoo.

- Shortage of Water: Kulhudhuffushi has a greater capacity to produce water through well-established plants and systems. Residents still use rainwater for cooking; however, rainwater is boiled before use. Bottled water and water shipped from other islands supplemented the local water supply. The presence of mangroves may contribute to the improved water quality in Kulhudhuffushi.

- Flooding: Flooding is a common problem in Kulhudhuffushi, particularly during the rainy season. This problem has been exacerbated by inadequate drainage systems and poor road development. Residents noted that flooding had become more frequent and severe than they were during childhood.

- Strong winds, rough seas, and storm surges: Kulhudhuffushi experiences strong winds and rough seas, particularly during monsoons. These conditions can make travel to and from remote islands challenging and pose difficulties during emergencies. However, the reef structure of the island may provide some protection compared to Hithadhoo.

- Loss of biodiversity: Kulhudhuffushi has witnessed a decline in biodiversity, which is primarily attributable to land reclamation at airports and other development projects. The removal of mangroves, particularly those acting as buffer zones around airports, has also raised concerns regarding water quality and mosquito breeding. However, some residents believe that the impact of land reclamation on biodiversity has not yet been fully reported.

3.2.2. Impacts of SLR

Hithadhoo

- Salinization of groundwater: These sources provide a nuanced perspective on groundwater salinization in Hithadhoo. The interviewees suggested that the primary cause of groundwater salinization in Hithadhoo is not directly linked to SLR. However, the widespread use of septic tanks before the introduction of modern sewage systems was identified as the primary cause. These septic tanks have been contaminated with freshwater lenses for several years. One interviewee highlighted that residents no longer rely on groundwater because of the availability of desalinated water and the perception that bottled water is safer and more hygienic. Consequently, the impact of salinization may not be apparent to residents.

- King tides and floods: Hithadhoo has undergone significant improvements in infrastructure that have mitigated the impact of king tides and floods. The development of robust sewage systems has effectively addressed prevalent flooding issues in the past. Residents, including those whose houses were prone to flooding, reported that flooding is no longer a major concern. However, one interviewee highlighted the ongoing flood problems in a specific location, indicating that challenges may persist in certain areas.

- Beach and coastal erosion: Coastal erosion is a significant concern in Hithadhoo, particularly affecting beaches frequently used for recreation by residents. This erosion was readily noticeable, and its impact was visible to residents. Notably, the beaches of Hithadhoo are primarily sandy, making them more susceptible to erosion than the gravel beaches in Kulhudhuffushi.

Kulhudhuffushi

- Salinization of groundwater: Residents of Kulhudhuffushi reported a change in the smell of groundwater after the removal of the mangrove areas. This suggests a possible link between mangrove loss and groundwater quality, although the sources do not explicitly state that the water has become salinized. Despite this change, residents rely primarily on filtered water, rainwater (for cooking after boiling), and bottled water. These sources do not directly address the issue of groundwater salinization caused by SLR in Kulhudhuffushi.

- King tides and floods: Kulhudhuffushi faces recurring challenges from king tides and floods. These events have become more frequent and severe than in the past, with flooding occurring even during non-monsoon seasons. The sources attribute this problem to ineffective drainage systems and road development, which have not been adequately addressed. The removal of mangroves, which act as natural buffers against flooding, has likely exacerbated this problem.

- Beach and coastal erosion: Although coastal erosion is a concern in Kulhudhuffushi, sources indicate that it is less severe than in Hithadhoo. This is attributed to the predominantly gravel beaches of the island, which are more resistant to erosion than the sandy beaches. However, residents have observed changes in the shape of the island owing to land reclamation and sand erosion caused by waves. The construction of a ring road has also led to the cutting down of trees, potentially increasing the vulnerability of the island to wind and erosion.

3.2.3. Best Way to Avoid Personal Risk of SLR

Hithadhoo

- Building sea walls: Opinions regarding seawalls in Hithadhoo were divided. Some participants acknowledge their role as visible symbols of protection that are easily understood and promoted by politicians. However, others argue that seawalls are unsustainable, demanding constant height increases to cope with SLR. An alternative is to allow waves to flow naturally through the islands.

- Land reclamation: Residents perceive land reclamation in Hithadhoo primarily as a method of expanding available land instead of a coastal defense strategy. Some residents, particularly those involved in environmental advocacy, oppose land reclamation because of its adverse effects on marine ecosystems. They highlight the significant costs involved in rebuilding homes and advocate for government assistance in tackling this challenge as a public concern. Conversely, others maintain that land reclamation is essential due to the limited land availability of the island.

- Rebuilding houses to increase elevation: Elevating existing houses is not widespread in Hithadhoo, although newer hotels are being constructed at higher elevations as safety measures. High rebuilding costs and limited land availability have been cited as obstacles. Residents who encountered flooding in the past implemented preventive measures based on their experiences, such as building causeways and walkways for water drainage.

- Encourage government action: Hithadhoo residents express strong conviction that the government should be more active in addressing climate change and SLR. They perceive a dearth of government investment and support in their regions, leading to feelings of neglect and a desire for intensified government involvement. This expectation stems from the belief that the government is responsible for allocating resources appropriately and providing solutions to climate-change-related issues.

- No specific action: The sources do not explicitly mention residents selecting no specific action to address SLR.

Kulhudhuffushi

- Building sea walls: Kulhudhuffushi residents generally deem sea walls ineffective, especially on beaches where their structural integrity is questioned. They believe that natural protective measures such as mangroves provide superior defense.

- Land reclamation: Land reclamation is a contentious topic in Kulhudhuffushi. Although some view it as a solution to land scarcity, others oppose it vehemently because of its negative ecological consequences. Community organizations have actively campaigned against mangrove reclamation, highlighting the significance of preserving natural habitats.

- Rebuilding houses to increase elevation: Elevated houses are gaining popularity in Kulhudhuffushi. Modern structures are often constructed at high elevations. Residents take precautions such as employing sandbags to protect their homes from flooding. Elevation is considered when constructing new houses, although there is no indication that existing houses are being rebuilt solely for elevation purposes.

- Encourage government action: Although Kulhudhuffushi residents anticipate government support, they exhibit a robust sense of self-reliance and willingness to take the initiative. They actively engage in community-based endeavors to address environmental concerns, reflecting their beliefs in autonomously generating solutions. The strong sense of ownership and dedication of the community to safeguarding its islands contributed to this proactive approach.

- No specific action: The sources do not explicitly mention residents selecting no specific action to address SLR. However, one interviewee stated that residents seem less concerned about the impacts of SLR, as they have already implemented land reclamation, and houses are generally built inland.

3.2.4. Explanations for Differing Attitudes Towards Government Action on Climate Change

These sources highlight a distinct difference in attitudes toward climate change between Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi residents.

The Reliance of Hithadhoo on Government Action

Several factors contribute to the tendency of Hithadhoo residents to expect and rely on government action:

- Perception regarding government responsibility: The residents in Hithadhoo feel a sense of entitlement to government assistance and view it as their right as taxpayers. They believed that government funds were not adequately allocated to their regions, leading to a sense of neglect and frustration. This perception was likely influenced by the historical involvement of the central government in development projects in Addu and the feeling of abandonment after the departure of the British Royal Air Force.

Higher education and awareness: Hithadhoo has a higher concentration of educated residents who are more aware of their rights and the role of the government in addressing climate change. They tend to be more vocal in demanding government action. In terms of learning outcomes, regional disparities are stark. For instance, cognitive achievement levels in English language skills (grade 4 and grade 7) are considerably higher in Malé, followed by those in the Seenu Atoll and the Gnaviyani Atoll being well above the rest of the country, while most other atolls perform poorly, including Haa Dhaalu Atoll. Statistically the regional disparities are less, but gaps still exist, and the Malé, Seenu and Gnaviyani atolls display the best performance [17].

- Exposure to external influences: Historically, Hithadhoo residents have had greater exposure to external influences, including migration and business activities. This exposure has broadened their perspectives and raised their expectations of government services and responses to climate change.

- Urbanized lifestyle: The more urbanized environment of Hithadhoo may contribute to a greater reliance on government services and infrastructure, leading to higher expectations of government intervention in addressing climate change-related issues.

The Self-Reliance and Community Action of Kulhudhuffushi

Kulhudhuffushi residents contrastingly demonstrated a strong preference for self-reliance and community-led initiatives. Interviewees attributed this to the following:

- Strong community bonds and sense of ownership: Kulhudhuffushi residents exhibit a strong sense of community and attachment to their islands. This connection fosters the desire to protect the environment and their ways of life through their own efforts.

- A history of independent problem solving: Kulhudhuffushi has a history of addressing local issues independently and fostering a culture of self-reliance. Residents have actively campaigned against environmentally damaging projects, such as mangrove reclamation, showing their commitment to protecting their islands through their own actions.

Limited government presence and perceived inefficiencies: The limited presence of the central government in Kulhudhuffushi, coupled with perceived inefficiencies in government-led projects, may have contributed to a sense of self-reliance. Residents may feel that they can address their issues more effectively than relying on government intervention.

- Island-oriented mentality: The smaller size and more isolated location of Kulhudhuffushi may contribute to a greater focus on local issues and solutions. Residents may also feel more connected to their immediate environment and empowered to act. One of the interviewees who was familiar with both Kulhudhuffushi and Hithadhoo suggested that the population in Kulhudhuffushi seem to have less experience of migration than Hithahoo, and they are less likely to evaluate events in their immediate surroundings comparing to other areas.

Based on the analysis in these sections, a summary of the results of the interview survey is shown in Table 6. Aspects on climate change impacts, SLR response and community response are described in relation to Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi.

Table 6.

Summary of the results of the follow-up interviews.

4. Discussion

In this section, based on the results presented, the recommended climate change adaptation measures are discussed for the two locations focused on in this study.

4.1. The Impacts of Climate Change Are Exacerbated by Rampant Developments

In both locations, Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi, the climate change impacts seem to be exacerbated by development activities and associated changes in the environments. For instance, from the observations in Hithadhoo, a significant increase in temperature was felt due to deforestation and the urban heat island effect. On the other hand, in Kulhudhuffushi, the temperature rise was less pronounced, and it was better mitigated by natural vegetation. The recorded mean temperatures were 28.2 °C observed at MMS station in Gan (close to Hithadhoo) and 28.5 °C at MMS station in Hanimaadhoo (close to Kulhudhuffushi) according to the data obtained from MMS by the authors. The measured mean temperature was slightly higher in the north, and the apparent temperature and sensible temperature were felt differently in two locations being studied. Furthermore, biodiversity loss was observed in both locations due to deforestation resulting in a decline in medicinal plants and other species in Hithadhoo, and in Kulhudhuffushi, a decline in biodiversity was pointed out as being primarily due to airport development and associated mangrove removals. In addition to actual temperature rise, extreme weather events and subsequent floodings are felt strongly due to urban development in these islands. In particular, large-scale reclamation projects are affecting the vegetation on the coastlines, resulting in higher temperature and heat. Ongoing reclamation projects in Hithadhoo are affecting the ecosystems, including the corals and the circulation of waters. Ongoing reclamation projects should take into account environmental safeguarding measures. In addition to the environmental impact assessments already carried out, careful monitoring and scientific assessments will be crucial.

4.2. Flood Control and Water Resource Management Are Perceived as Adaptation Priority

Measures should focus on several key areas of action to protect urban communities and natural ecosystems. Infrastructure development is critical to strengthening and expanding seawalls to shield urban areas and vital infrastructure from rising seas and extreme weather events. This includes upgrading urban drainage systems to better handle increased flooding and to ensure that cities remain functional during severe weather conditions. Adapting to climate change requires both individual- and community-based initiatives, particularly in coastal areas. Homeowners should be encouraged to make their properties more resilient through elevation- and flood-proofing measures to withstand regular flooding and extreme weather events. At the community level, local initiatives, such as coastal erosion management through natural solutions, including mangrove planting, can provide adequate protection for coastlines.

Water security is another crucial focus, with initiatives to develop sustainable water storage solutions and desalination facilities to combat freshwater scarcity and salinization. These technical solutions should be complemented by public awareness campaigns designed to promote water conservation practices among urban residents, thereby ensuring more efficient use of limited water resources.

Water security presents a significant challenge in Kulhudhuffushi, reflecting the broader issue faced by several Maldivian islands due to climate change [18]. Learning from successful implementation on other islands, including Nolhivaranfaru, Foakaidhoo, Maduvvari, and Dharavandhoo, the adoption of integrated water resource management (IWRM) systems can provide a solution. These systems effectively combine rainwater, groundwater, and desalinated water sources during dry periods [19]. Furthermore, the implementation of enhanced rainwater-harvesting systems, which have been successful in several atolls by expanding the water collection capacity of public buildings [18], can significantly improve the water security of Kulhudhuffushi.

4.3. Localized Planning Is Essential but Lacks Capacity and Scientific Basis

The present analysis suggests that climate change adaptation measures in the Maldives must be highly localized, taking into consideration the unique environmental and cultural characteristics of each island community. There are several ways in which locality should be reflected in adaptation strategies. First, infrastructure development should be customized. For instance, in urban areas such as Hithadhoo in Addu, infrastructure development should prioritize urban resilience, such as reinforced sea walls, advanced drainage systems, and climate-proof urban planning. Investments should consider dense populations and economic activities, with a focus on minimizing the disruptions caused by flooding and extreme weather.

Notably, in rural and less urbanized areas, such as Kulhudhuffushi, adaptation strategies should emphasize flexible, low-impact solutions that align with the reliance of the community on natural resources. Examples include mangrove restoration for coastal protection, community-based flood prevention methods, and sustainable housing designs.

In the current national climate adaptation policies, local councils are responsible for planning and implementing relevant measures; however, there is a lack of capacity and scientific basis at the local level. In particular, in Hithadhoo, in terms of responses to climate change, the expectations for strong government interventions are high, and residents view this type of assistance as a taxpayer rights. However, in Kulhudhuffushi, the islanders tend to be more self-reliant and prefer community-led solutions. The level of delegation and budget allocations are essential, and local councils need to be equipped with adequate resources to address climate change impacts. Kulhudhuffushi is among the multiple cities that participate in the UN Making Cities Resilient 2030 (MCR2030) program [20], and this could be one of the vehicles through which to provide the much needed financial and technical input to the City. Adaptive and inclusive policy frameworks must be pursued to ensure that the geographic and social differences across the islands are considered.

4.4. Socio-Economic, Cultural and Educational Backgrounds Affect the Acceptability of Climate Change Adaptation Measures

Community engagement and cultural sensitivity must be promoted. In Hithadhoo in Addu City, an urban area, individuals holding political positions are more likely to advocate for government-led initiatives. In this context, adaptation measures should involve participatory planning to ensure that policies are transparent and supported by scientific research. Collaboration between local authorities and community leaders can help ensure that measures are well received and effectively implemented. Additionally, initiatives should focus on existing industries in respective locations; for instance, adaptive fishing practices should be promoted in Kulhudhuffushi, considering the primary means of livelihoods for the residents. Government support can be provided in a manner that complements community initiatives instead of overriding them.

Public awareness and education play vital roles in adaptation to climate change. Communities should be empowered through increased awareness of climate change impacts and encouraged to take proactive measures that combine traditional and modern adaptation practices. The level of awareness on climate change differed in Hithadhoo and Kulhudhuffushi, which could affect the acceptance and effectiveness of the local approach to climate change adaptation [21]. Educational programs should be established to enhance understanding of environmental changes and build community resilience. These approaches need to be tailored to local contexts; for instance, in Hithadhoo in Addu, the emphasis is on urban infrastructure and governmental action, whereas Kulhudhuffushi benefits from a more community-driven, self-reliant approach.

5. Conclusions

Locality in the Maldives is central to adaptation to climate change. Strategies should acknowledge the social dynamics and environmental features of each island to ensure that the measures are practical, culturally appropriate, and environmentally sustainable. Through these measures, the Maldives can build a resilient nation that respects the diversity of its island communities while effectively addressing climate change challenges. Effective climate change adaptation measures on the remote islands in the Maldives are crucial because of the vulnerability of the country to SLR, increased flooding, and other environmental challenges associated with climate change. Remote islands, which often have limited resources and infrastructure, require tailored strategies to build their resilience. The following are key adaptation measures: A comprehensive approach is recommended for Hithadhoo in Addu that focuses on infrastructure development, water security, environmental conservation, and community involvement. Key measures include reinforcing seawalls, upgrading drainage systems to combat flooding, and developing sustainable water storage and desalination facilities. Public awareness campaigns and policies promoting water conservation are vital. Additionally, conservation efforts, such as mangrove restoration and coral reef protection, are essential for biodiversity and natural defense against climate change. In Kulhudhuffushi, adaptation measures prioritize coastal management and water security, encouraging resilient property designs, such as elevated buildings and flood-proofing. Natural solutions such as mangrove planting and dune restoration have been emphasized over large-scale reclamation. The water management system of the island should adopt an IWRM and enhanced rainwater harvesting. Community-based education and awareness programs are vital for promoting proactive adaptation measures with a focus on self-reliance and local environmental conservation. In both locations, adaptation strategies must be tailored to the specific needs of each community, with Addu focusing on urban resilience and government-led efforts and Kulhudhuffushi emphasizing community-driven, nature-based solutions. A decentralized approach to governance that incorporates local feedback and cultural sensitivity is essential for effective and sustainable adaptation policies across the Maldives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; methodology, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; software, M.N.; validation, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; formal analysis, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; investigation, M.M. and A.S.; resources, M.M., A.S., R.A.R. and A.K.; data curation, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., A.S., R.A.R., A.K. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.M., A.S., R.A.R., A.K. and M.N.; visualization, M.M., A.S. and M.N.; supervision, M.M. and M.N.; project administration, M.M. and A.S.; funding acquisition, M.M., A.S. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, KAKENHI grant number 24K03174, and Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation Japan. The authors express their sincere appreciation for their generous support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The questionnaire survey was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of GIF Japan on 8 November 2023, in accordance with the research ethics guidelines of GIF Japan. Ethical review and approval were waived for the interview survey as the interviews were conducted anonymously and thus did not require convening ethics review board approval, according to the research ethics regulations of GIF Japan.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The data is archived by the institutions of the authors, but it is not publicly available due to privacy of the informants.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (SPF), Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation Japan (GIF Japan), MNU staff members, and informants who participated in the survey. The authors greatly appreciate the assistance provided by Yusuke Goto, Yuto Kunitake, Moeri Matsuda, and Kazuma Taiko, Visiting Fellow of GIF Japan, Keiko Kikuchi, Research Assistant of GIF Japan, and Sushrut Royyuru, Intern of SPF.

Conflicts of Interest

Miko Maekawa received funding from the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (SPF) as an employee of SPF. Akiko Sakamoto and Mikiyasu Nakayama received funding from the Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation Japan (GIF Japan), another funder of this research, as employees of GIF Japan. Both SPF and GIF Japan are research institutes in Japan that implement mostly self-financed research projects, and thus, both organizations played roles in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results through their dedicated researchers. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Bank, Indicator. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Maldives Bureau of Statistics (Ministry of Housing, Land & Urban Development). Population Dynamics in the Maldives: An Analysis from Census 2022. 2023. Available online: https://census.gov.mv/2022/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Population_Census-2022_Report-Updated-130324.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- World Bank Group. Maldives Country Climate and Development Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/41729 (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- World Bank Group. Climate Change Knowledge Portal, Maldives. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/maldives/climate-data-historical (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group II—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Fact Sheet—Responding to Sea Level Rise. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FactSheet_SLR.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Nakayama, M.; Fujikura, R.; Okuda, R.; Fujii, M.; Takashima, R.; Murakawa, T.; Sakai, E.; Iwama, H. Alternatives for the Marshall Islands to cope with the anticipated sea level rise by climate change. J. Disaster Res. 2022, 17, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Energy and Water, Republic of Maldives. National Adaptation Programme of Action. 2007. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/mdv01.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ministry of Environment and Energy, Republic of Maldives. Maldives: Climate Change Policy Framework (2015–2025). 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/maldives-climate-change-policy-framework-2015-2025 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ministry of Environment, Update of Nationally Determined Contribution of Maldives. 2020. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Maldives%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contribution%202020.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Technology, Republic of Maldives, Project Advancing the National Adaptation Plan of the Maldives (NAP Maldives). Available online: https://www.environment.gov.mv/v2/en/project/25592 (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Maldives Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Yearbook of Maldives. 2023. Available online: https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/yearbook/2023/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Technology, Maldives. Climate Emergency Act to Achieve Carbon Neutrality in Maldives by 2030. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/2-4%20Maldives%20-%20Ahmed%20Ali.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Arai, E.; Imaizumi, S. (Eds.) 35 Chapters for Getting to Know the Maldives; Akashi Shoten: Chiyoda-ku, Japan, 2021. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Discover Addu, 2025. Discover Addu—The Southern Splendor of Maldives. Available online: https://www.discoveraddu.com/about-addu/history/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Masveriya, Z. Kulhuduffushi: Culture, and History. Available online: https://zuvaanmasveriya.com/hdh-kulhudhuffushi/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Base Map: Map of the Republic of Maldives by Ziansh, Wikimedia Commons. 2024. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maldives_location_map.svg (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Aturupane, H.; Shojo, M. Enhancing the Quality of Education in the Maldives Challenges and Prospects; Discussion Paper Series Report No. 51, South Asia: Human Development Unit, The World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/905361468279355462/pdf/679180NWP00PUB07903B0Report00No-510.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Deng, C. Assessing Impacts of Rainfall Patterns, Population Growth, and Sea Level Rise on Groundwater Supply in the Republic of the Maldives. Master’s Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. On Tap: How the Maldives Is Restoring Water Security on Its Most Vulnerable Outer Islands. 2022. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/maldives/tap-how-maldives-restoring-water-security-its-most-vulnerable-outer-islands (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- National Disaster Management Authority. Making Cities Resilient (MCR). Available online: https://ndma.gov.mv/en/making-cities-resilient-mcr (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Pisor, A.; Lansing, J.S.; Magargal, K. Climate change adaptation needs a science of culture. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2023, 378, 20220390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).