Evaluation of Management Effectiveness of an Outstanding Marine Protected Area in Southwest Coast of Türkiye: On the Road to 30 by 30

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- A review of relevant literature and mainstream media focusing on the study area (mainly the news and articles about the meetings/stakeholder gatherings in Gökova publicized in local media and stakeholders’ websites)

- Project reports (conservation and research project reports that were made available online and ongoing projects’ progress reports obtained from project managers working in NGOs operating in Gökova)

- A self-assessment tool previously tested by the co-managers of the Gökova MPA

- Semi-structured interviews with the key stakeholders identified in the MP.

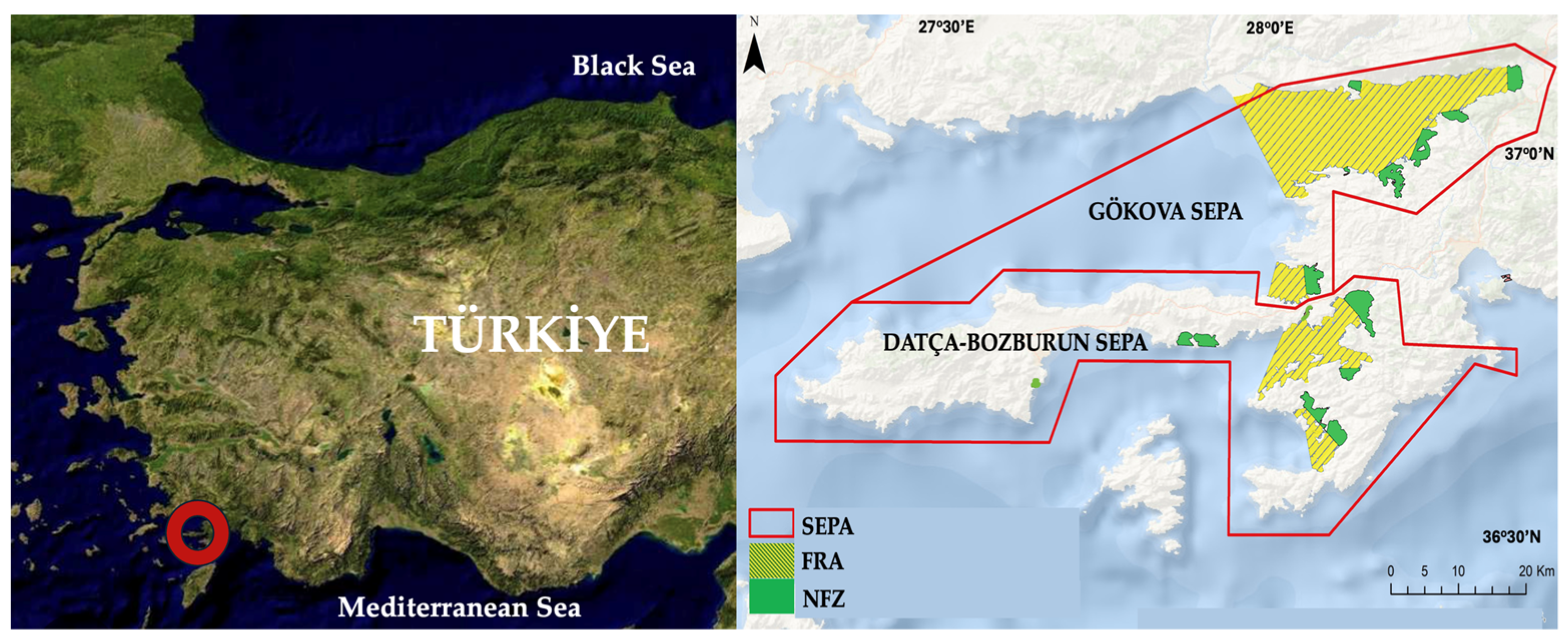

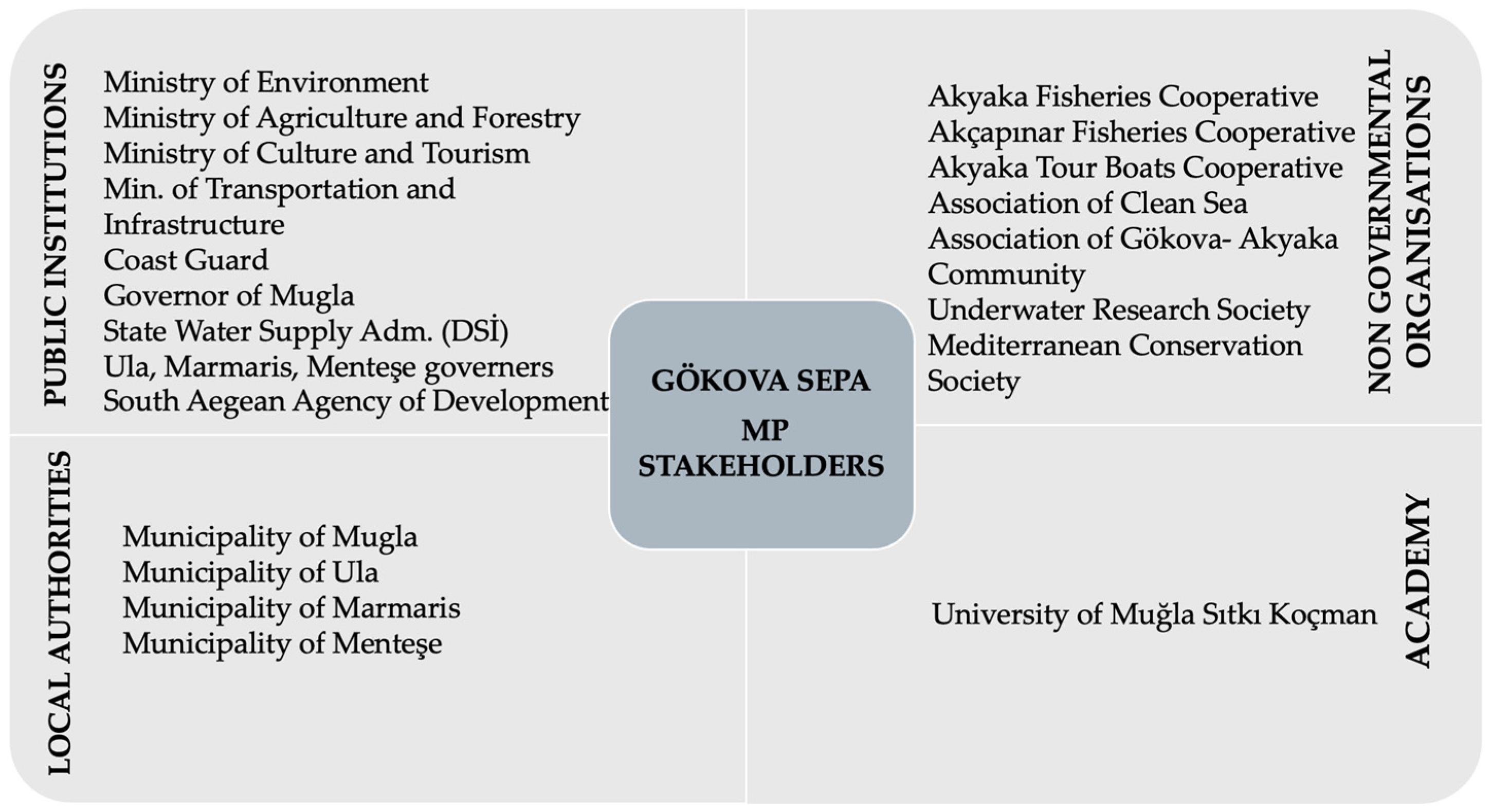

2.1. Study Area/Context

2.2. The Effectiveness and Durability Analysis of Gökova MPA with Blue Diagnosis Self-Assessment Tool

2.3. Gökova MP Implementation and Semi-Structured Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

- 1-

- Ministry of Environment Urbanization and Climate Change.

- 2-

- Local public institutions.

- 3-

- Municipalities.

- 4-

- NGOs.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. MP Activities Overview

3.2. Comparison of MEA Results 2021 and 2022

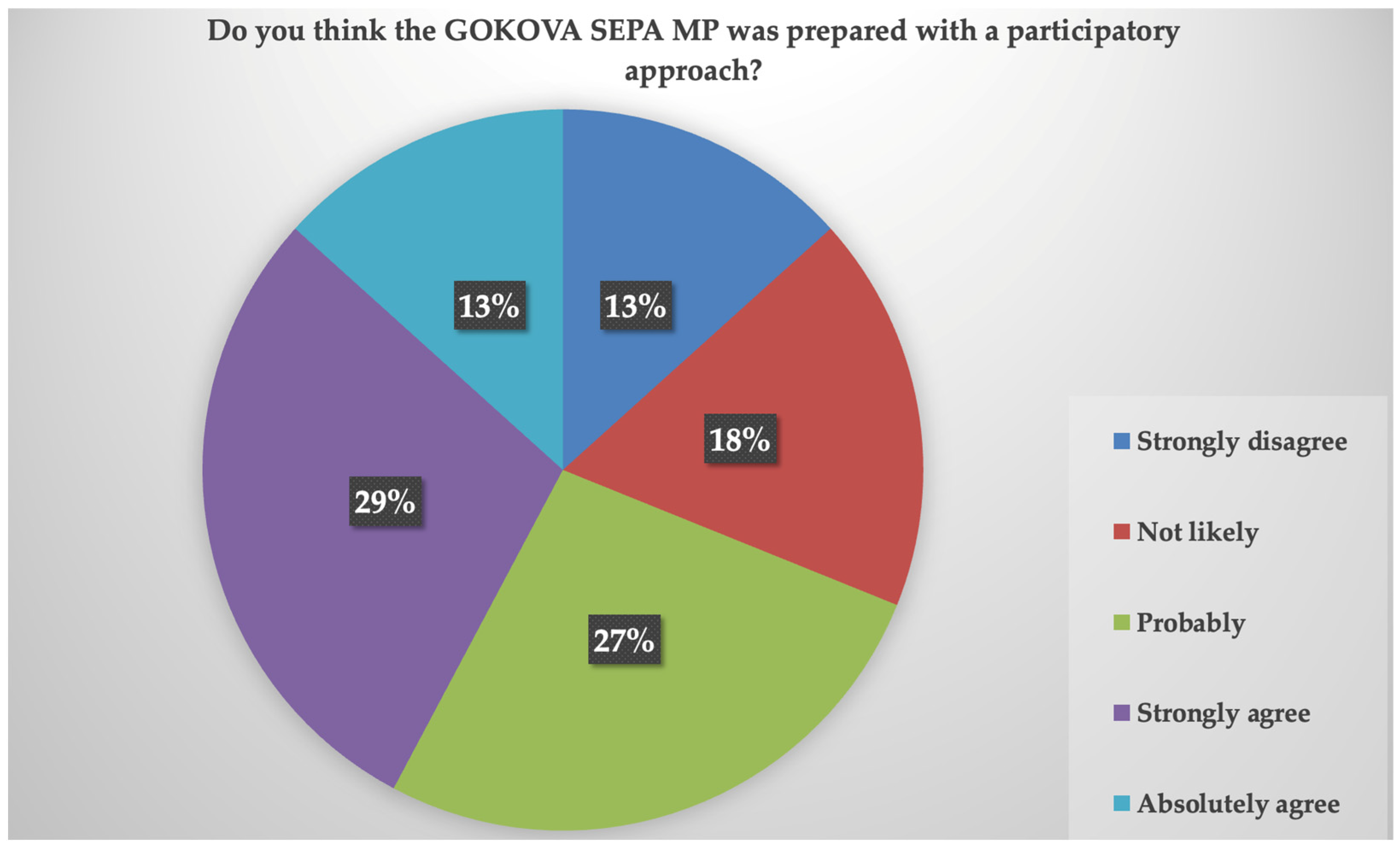

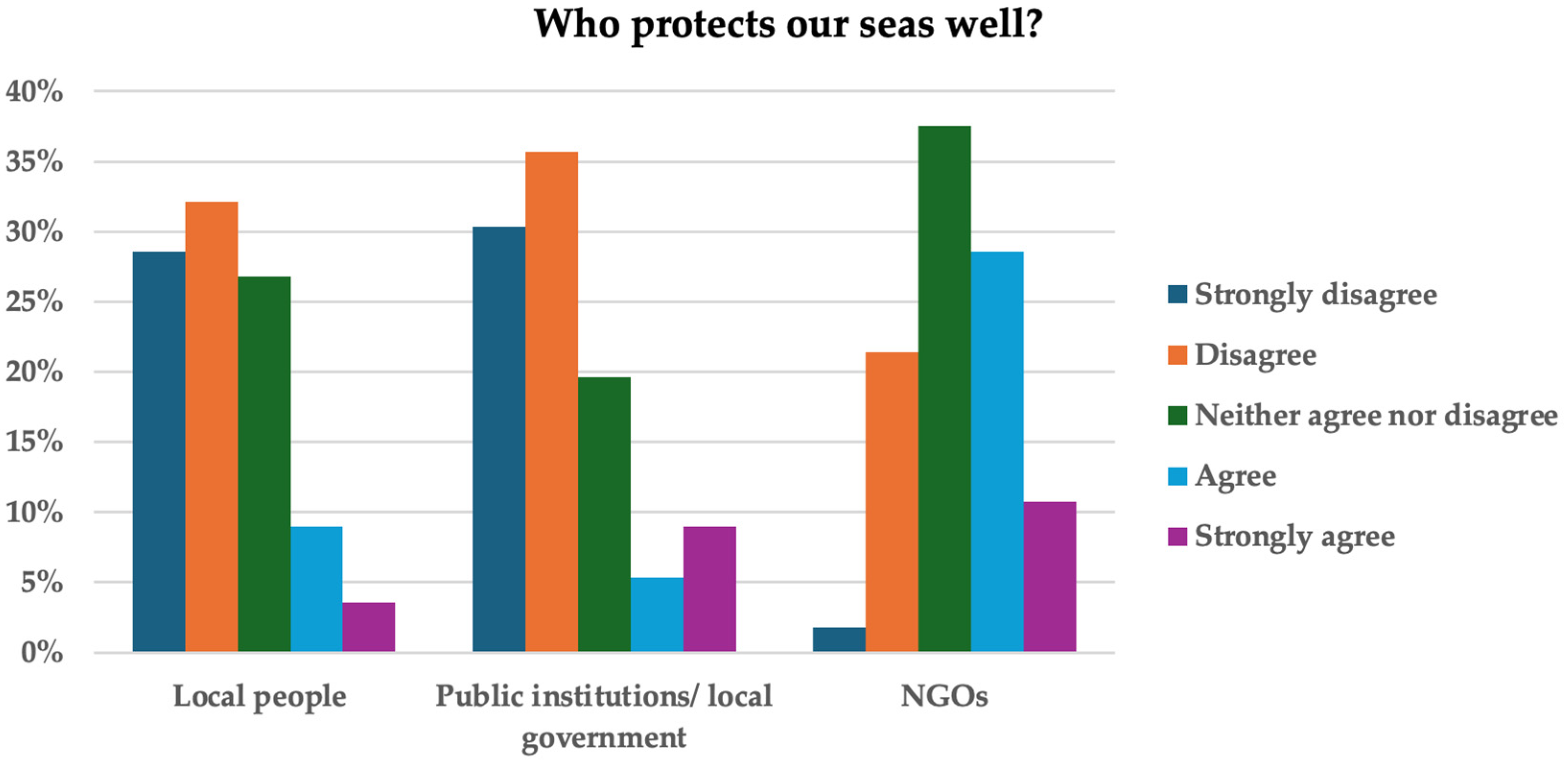

3.3. Interviews

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations

- -

- Creating an enabling environment for central governmental organizations’ local units by giving them full authority anchored in relevant legislation and by-laws to implement national conservation policies at the local level,

- -

- A continuous capacity building plan developed for both central and local government departments,

- -

- Anchoring MPAs into legislation and ensuring that the MPs are legally binding providing its inclusion into performance assessments of institutions in charge,

- -

- Including preliminary investigations to determine stakeholders’ perceptions and attitudes into MP preparation workflow,

- -

- Monitoring and evaluation of each MP carried out regularly and in a timely manner. Providing the transparency of these meetings by announcing the course and sharing the outcomes,

- -

- Setting joint action and active communication between NGOs and other key stakeholders as a condition to reach grant funding and necessary permissions,

- -

- Sharing the findings from research and project outputs with the community and other stakeholders on a regular basis and providing an enabling environment for their input,

- -

- Creating business plans that include alternative revenue streams to ensure the MPAs financial sustainability and anchoring them in MPs budget and action plan,

- -

- Allocating a certain part of the revenues obtained from the use of natural resources (museum visits, beach sun loungers, umbrella uses, tour boats, etc.) to the institutions and organizations that carry out nature conservation activities and reporting in a transparent manner, visible to citizens,

- -

- Establishing a common database on the studies carried out in MPAs, encouraging researchers, NGOs and institutions to use this mechanism effectively. Sharing the project and the program outputs, lessons learned, visuals, maps, etc. In this database which would be accessible to encourage citizen science.

- -

- Future studies should consider integrating more diverse data sources and participatory methodologies, such as conducting interviews with a broader range of stakeholders, and perform reassessment with consistent evaluators to enable meaningful comparisons overtime and minimizing potential bias.

- -

- Expanding the response options in the assessment tool to include scaled or qualitative responses that can offer a more comprehensive MEA.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| BD | Blue Diagnosis |

| B-W | Best-Worst analysis |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| DNCN | Directorate of Natural Conservation and Natural Parks |

| GBF | Global Biodiversity Framework |

| GDPNA | General Directorate for Protection of Natural Assets |

| FRA | Fisheries Restricted Area |

| MEA | Management Effectiveness Assessment |

| MoECC | Ministry of Environment Urbanisation and Climate Change |

| MoAF | Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry |

| MPA | Marine Protected Areas |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organisation |

| NFZ | No Fishing Zone |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SEPA | Special Environmental Protected Areas |

| PA | Protected Area |

| WDPA | World Database on Protected Areas |

References

- Beverton, R.J.; Holt, S.J. On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Population, 3rd ed.; Fish & Fisheries Series; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1993; pp. 370–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.; Potts, T.; Jackson, E.; Burdon, D.; Atkins, J.; Hastings, E.; Fletcher, S. Linking Ecosystem Services of MPAs to Benefits in Human Wellbeing? In Coastal Zone Ecosystem Services. Studies in Ecological Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 9, pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.B.; Page, G.G.; Ochoa, E. The Analysis of Governance Responses to Ecosystem Change: A Handbook for Assembling a Baseline. In LOICZ Reports & Studies; GKSS Research Center: Geesthacht, Germany, 2009; pp. 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, S.C.; Tupper, M.H.; Ridley, J.M. The three screen doors: Can marine “protected” areas be effective? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Significance and Diversification of Marine Protected Areas in Coastal Marine Management: Key Issues in Scaling Up Marine Management the Role of Marine Protected Areas; The World Bank, Environment Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 36635, pp. 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tempesta, M.; Otero, M.D. Guide for Quick Evaluation of Management in Mediterranean MPAs; WWF: Rome, Italy; IUCN: Malaga, Spain, 2013; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lubchenco, J.; Grorud-Colvert, K. Making waves: The science and politics of ocean protection. Science 2015, 350, 382–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, D.K.; Ducarme, F.; Gallon, S. Towards Assessing Management Effectiveness of Mediterranean MPAs; MedPAN: Marseille, France, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at Its Tenth Meeting; COP10 on Biological Diversity, Nagoya; UNEP. 2010; 8p. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-10/cop-10-dec-02-en.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Gomei, M.; Abdulla, A.; Schröder, C.; Yadav, S.; Sanchez, A.; Rodriegez, D.; Abdel Malek, D. Towards 2020: How Mediterranean Countries Are Performing to Protect Their Sea. MedMPA Project, WWF. 2019; p 36. Available online: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_towards_2020_how_mediterranean_countries_are_performing_to_protect_their_sea.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- CBD. Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity 15/4: Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Fifteenth Meeting—Part II, Montreal, Canada, 7–19 December 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Grorud-Colvert, K.; Sullivan-Stack, J.; Roberts, C.; Constant, V.; Hosta e Costa, B.; Pike, E.P.; Kingston, N.; Laffoley, D.; Sala, E.; Claudet, J.; et al. The MPA Guide: A Framework to Achieve Global Goals for The Ocean. Science 2021, 373, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, E.; MacCarthy, J.; Hameed, S.; Harasta, N.; Grorud-Kolvert, K.; Stack, J.; Claudet, J.; Costa, B.; Gonçalves, E.; Villagomez, V.; et al. Ocean protection quality is lagging behind quantity: Applying a scientific framework to assess real marine protected area progress against the 30 by 30 target. Conserv. Lett. 2024, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, L. Marine Protected Areas in Colombia: Advances in conservation and barriers for effective governance. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 125, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Morrison, C.; Watling, D.; Tuiwawa, M.V.; Rounds, I.A. Conservation in tropical Pacific Island countries: Why most current approaches are failing. Conserv. Lett 2012, 5, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Chen, M.; Zeng, C.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zou, C.; Ye, S.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, L. Assessing the management effectiveness of China’s marine protected areas: Challenges and recommendations. Ocean Coast. Manag 2022, 224, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboğlu, G.; Güçlüsoy, H.; Bizsel, K.C. Marine Protected Areas in Turkey: History, Current State and Future Prospects. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas, Micnas, Morocco, 23–25 March 2005; pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- MoECC. Special Environmental Protected Areas Management Plans. 2024. Available online: https://tvk.csb.gov.tr/yonetim-planlari-i-4551 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- MoECC. News: The First Management Plan Monitoring Meeting Held in Mugla. 2 January 2024. Available online: https://mugla.csb.gov.tr/Gökova-ozel-cevre-koruma-bolgesi-yonetim-plani-toplantisi-haber-285898 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- MedPAN. MPA Success Story: Gökova, an Example of Co-Management with Small Scale Fishers to Restore the Marine Ecosystem. 13 March 2024. Available online: https://medpan.org/en/resource-center/mpa-success-story-gokova-example-co-management-small-scale-fishers-restore-marine (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- UNEP. The Benefits of Ecosystem Restoration: 11 Lessons Learned from an Analysis of 5 European Restoration Initiatives; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medfund. Annual Report. 2021; pp. 13–28. Available online: https://themedfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Annual-report-2021_The-MedFund.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E. The Global 200: Priority Ecoregions for Global Conservation. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2002, 89, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, V.; Erdem, M. Combating illegal fishing in Gökova MPA (Aegean Sea), Turkey. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Underwater Research, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, 19–21 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- SAYS. Protected Areas Management System. Available online: https://says.csb.gov.tr/citizen (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Ünal, V.; Kızılkaya, Z. A Long and Participatory Process Towards Successful Fishery Management of Gökova Bay, Turkey. In From Catastrophe to Recovery: Stories of Fishery Management Success; Krueger, C.C., Taylor, W.W., Youn, S.J., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜİK. Gökova ÖÇKB ilçe ve Mahallelerinin Demografik Yapısı, 2018. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Adrese-Dayali-Nufus-Kayit-Sistemi-Sonuclari-2018-30709 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- TVKGM. Gökova Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgesi Yönetim Plani 2020–2024, T.C. Çevre Ve Şehircilik Bakankiği Tabiat Varliklarini Koruma Genel Müdürlüğü. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/tabiat/editordosya/DigitalKopya24mart2020.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- TÜİK. Gökova ÖÇKB ilçe ve Mahallelerinin Demografik Yapısı. 2022. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Adrese-Dayali-Nufus-Kayit-Sistemi-Sonuclari-2022-49685 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Okus, E.; Yuksek, A.; Yılmaz, İ.; Aslan-Yilmaz, A.; Demirel, N.; Karhan, S.; Demir, V.; Zeki, S.; Yokes, B.; Tural, U.; et al. The threats on the biodiversity of Gökova SEPA and solutions for a sustainable environment. In Proceedings of the Medcoast 07, The Eighth International Conference on the Mediterranean Coastal Environment, Alexandria, Egypt, 13–17 November 2007; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kıraç, C.O.; Orhun, C.; Toprak, A.; Veryeri, N.O.; Galli-Orsi, U.; Ünal, V.; Erdem, M.; Çalca, A.; Ergün, G.; Suseven, B.; et al. Gökova Özel Çevre Koruma Bölgesi Kıyı ve Deniz Alanları Bütünleşik Yönetim Planlaması. In Proceedings of the Türkiye Kıyıları Ulusal Konferansı (KAY Türk Milli Komitesi), Trabzon, Türkiye, 27 April–1 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kıraç, C.; Ünal, V.; Veryeri, O.; Güçlüsoy, H.; Yalçıner, A. Gökova’da Yürütülen Kıyı Alanları Yönetimi Temelli Projeler Envanteri ve Korumada Verimlilik. Türkiye’nin Kıyı ve Deniz Alanları IX. In Proceedings of the Ulusal Kongresi, Hatay, Türkiye, 14–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette, 2010, 2/1 Numaralı Ticari Amaçlı Su ürünleri Avcılığını Düzenleyen Tebliğde Değişiklik Yapılmasına Dair Tebliğ, Tebliğ no: 2010/25, Sayı: 27637, 10 July 2010. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2010/07/20100710-17.htm (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Official Gazette, 1995, Su Ürünleri Yönetmeliğinde Değişiklik Yapılmasına Dair Yönetmelik, Sayı: 22223, 10 March 1995. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2004/02/20040215.htm#3 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Official Gazette, 2016, 4/1 Ticari Amaçlı Su ürünleri Avcılığının Düzenlenmesi Hakkında Tebliğ, Tebliğ no: 2016/41, Sayı: 29828, 11 September 2016. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/BSGM/Lists/Duyuru/Attachments/64/4-1-Numaral%c4%b1-Ticari-Ama%c3%a7l%c4%b1%20-Su-%c3%9cr%c3%bcnleri-Avc%c4%b1l%c4%b1%c4%9f%c4%b1n%c4%b1n-D%c3%bczenlenmesi-Hakk%c4%b1nda%20Tebli%c4%9f.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Official Gazette, 2020, Amatör ve Ticari Amaçlı Su Ürünleri Avcılığının Düzenlenmesi Hakkındaki Tebliğler, 5/1, 5/2, Sayı: 31221, 22 August 2020. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2020/08/20200822-8.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Official Gazette, 2022, Amatör ve Ticari Amaçlı Su Ürünleri Avcılığının Düzenlenmesi Hakkındaki Tebliğler, 5/1, 5/2, Sayı: 31949, 10 September 2022. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2022/09/20220910-5.htm (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- GDPNA. Gökova Natural Protected Areas Ecological Base Research Report (Gökova Doğal Sit Alanları Ekolojik Temelli Bilimsel Araştırma Raporu); Çevre ve Şehirclik Bakanlığı, Tabiat Varlıklarını Koruma Genel Müdürlüğü: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016; 198p. [Google Scholar]

- Blueseeds. Developed by BlueSeeds, with the Financial Support of the MAVA Foundation. 2021. Available online: https://blueseeds.org/en/tools/management-assessment-tool-marine-protected-areas/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Forman, E.H.; Gass, S.I. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: An Exposition. Oper. Res. 2001, 49, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/MAP, and PlanBleu. State of the Environment and Development in The Mediterranean. SoED, UNEP/MAP, Plan Bleu Regional Activity Center, Nairobi. 2020; 309p. Available online: https://planbleu.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SoED_full-report.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Louviere, J.J. Best-Worst Scaling: A Model for the Largest Difference Judgements; Working Paper, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.C.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Holmes, G.; Laffoley, D.; Stolton, S.; Wells, S.M. Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Medfund. News: Medfund Supports Co-management of Gökova MPA in Turkey. 27 January 2020. Available online: https://themedfund.org/en/news/the-medfund-octroie-un-nouveau-soutien-financier-d1-million-deuros-pour-les-aires-marines-protegees-de-la-mediterranee/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- MCS, Akdeniz Koruma Derneği. Mediterranean Conservation Society Annual Report. Available online: https://akdenizkoruma.org.tr/storage/LJzw5Kl5O0Lkt9nJs3NHeDOJLdx0Y58OR13UWp93.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- ELSP, Endangered Landscape and Seascape Programs, Gökova Bay to Cape Gelidonya, Turkiye. Available online: https://www.endangeredlandscapes.org/project/gokova-bay-to-cape-gelidonya/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for Türkiye from the World Database on Protected Areas. September 2024. Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Giglio, V.J.; Moura, R.L.; Gibran, F.Z.; Rossi, L.C.; Banzato, B.M.; Corsso, J.T.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Motta, F.S. Do managers and stakeholders have congruent perceptions on marine protected area management effectiveness? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Business owners/managers (hotels, restaurants, cafes, etc.) | 11 | 18.97 |

| Fishermen | 6 | 10.34 |

| Governmental organizations | 19 | 32.76 |

| NGO representatives | 6 | 10.34 |

| Academics | 6 | 10.34 |

| Residents in Gökova Bay | 10 | 17.24 |

| Total | 58 | 100.00 |

| 2021 | 2022 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current (50%) | Resilience (40%) | Potential (10%) | Total Score | Current (50%) | Resilience (40%) | Potential (10%) | Total Score | |

| Environment | 50 | 30 | 6.7 | 86.7 | 50 | 10 | 0 | 60 |

| Finance | 16.7 | 32 | 0 | 48.7 | 0 | 24 | 3.3 | 27.3 |

| Stakeholders | 10 | 20 | 3.3 | 33.3 | 20 | 20 | 3.3 | 43.3 |

| Human resources | 50 | 40 | 0 | 90 | 33.3 | 16 | 0 | 49.3 |

| Innovation | 50 | 0 | 10 | 60 | 50 | 0 | 10 | 60 |

| Axis/Category | Indicator | 2021 | 2022 | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment/Resilience | Coordinated activities | Conservation activities are coordinated to increase their individual positive impact on the environment | Conservation activities are not necessarily coordinated relative to their final goal (e.g., protection of seagrass meadows: reducing simultaneously pressures from wild anchoring, pollution and bottom-trawling). | Conservation objectives are not specifically tied to the necessary activities. The institutions partially fulfill their responsibilities and not necessarily related to the MP or its vision. |

| Environmental education | Existing good-quality environmental education program, with known results | Little or no existing awareness-raising programs. | Awareness raising programs are built around project requirements, and extensively focusing on “pollution” component lacking an ecosystem-based approach including biodiversity at the time of the assessment | |

| Environment/Potential | Citizen science | Some monitoring activities are carried out by members of the general public | A participatory approach is not considered or structured. | No structured citizen science practice in place |

| Finance/Current | Financial strategy | Existing financial strategy in relationship to the conservation objectives of the MP, including a business plan for the entire duration of the MP (i.e., 10 years). | No financial planning linked to conservation objectives. | Financial strategy and business plan are partially done by the NGO, not included in the MP and/or public institutions’ budgets |

| Finance/Resilience | Self-funding | Existence of self-financing mechanisms (e.g., donations, mooring rights, visitor fees, concession fees). | No self-financing. | There isn’t a self-financing mechanism in the MPA level, and it is not covered in the MP |

| Alternative funding | Financial opportunities in the MPA? Do you know of any possible financial partners in the area? Which ones? | Little alternatives or visible opportunities in the area. No known possible financial partner in the area. | Financial alternatives are limited to the NGOs network and primarily from project grants | |

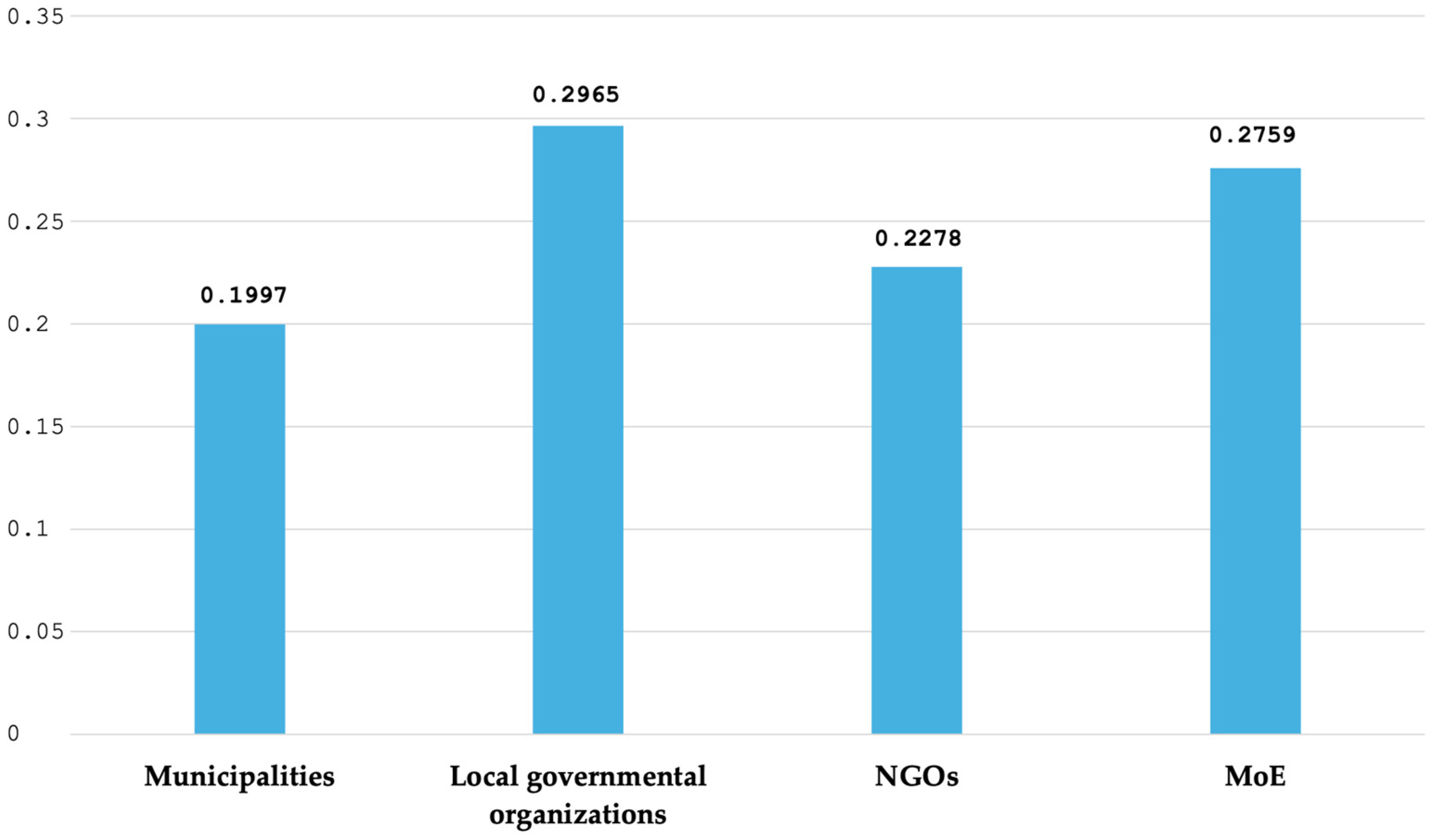

| Partnerships/Current | Social acceptability | Local partners represent <50% of partners. Local actors question the legitimacy of the MPA. Conservation measures are not considered to be legitimate. | At least 50% of partners are local (see Figure 1). The MPA is perceived positively by local actors. Conservation measures are accepted. | This question wasn’t understood well during the assessment in 2021; therefore, a negative answer was given. Partnership refers to the stakeholder’s relevance to the area rather than the funding organizations’ origin, which caused ambiguity. |

| Team/Current | Staff | The management team adapted in number to the activities defined in the MP. Structured team, with specialized job descriptions. Organizational chart respected in day-to-day activities. Recruitment of volunteers during the high season to face the increase in pressures on the MPA. | Insufficient number of employees to carry out management activities. Distribution of roles not respected. | The question was answered considering the NGOs human resources, which is object to change and limited by the project grants. Within the national authorities there isn’t specifically assigned staff to administer MP activities, except for the agreement between NGO and the GDPNA |

| Team/Resilience | Autonomy | Relevant, clear and balanced distribution of tasks. | Superposition of skills. Distribution of tasks sometimes misunderstood by team members. | As above. The authority in various areas is overlapping due to a lack of structured allocation of tasks and responsibilities. As stated in the survey results, 30% of public institution staff thinks that they have limited influence and are not able to take initiative |

| Maturity | The members of the team stay in place for a long time (permanent positions) and are not constantly replaced. Good working relationships, valuing results and individuals, ability to resolve conflicts. | Regular turnover of team members. | There is a high turnover rate both in the NGOs and national authorities’ organizational structure. | |

| Internal communication | Weekly and structured team meetings (with meeting reports). Use of operational communication channels | Difficult internal communication, non-existent communication channels, little transparency. | In the scope of the MP and the communication channels between actors are proved to be insufficient as a steering committee was not in place and there wasn’t any regular monitoring and reporting system between the institutions at the time of both assessments |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kok, F.; Sisman-Aydin, G. Evaluation of Management Effectiveness of an Outstanding Marine Protected Area in Southwest Coast of Türkiye: On the Road to 30 by 30. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051905

Kok F, Sisman-Aydin G. Evaluation of Management Effectiveness of an Outstanding Marine Protected Area in Southwest Coast of Türkiye: On the Road to 30 by 30. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051905

Chicago/Turabian StyleKok, Funda, and Goknur Sisman-Aydin. 2025. "Evaluation of Management Effectiveness of an Outstanding Marine Protected Area in Southwest Coast of Türkiye: On the Road to 30 by 30" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051905

APA StyleKok, F., & Sisman-Aydin, G. (2025). Evaluation of Management Effectiveness of an Outstanding Marine Protected Area in Southwest Coast of Türkiye: On the Road to 30 by 30. Sustainability, 17(5), 1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051905