Abstract

The development of new quality productive forces and the improvement of human capital have significantly improved people’s material and spiritual living standards. However, this has not brought people time affluence. Time poverty is related to lower happiness and physical health, and should be of concern. This paper theoretically analyzes the relationship among new quality productive forces, human capital level and time poverty, and conducts an empirical study based on the data from the Residents’ Life Time Allocation Survey from 2006 to 2021. The results show that more than 40% of individuals feel time poverty. Under the combined influence of new quality productive forces and human capital level, individual work time is still increasing, while leisure time is decreasing, which has contributed to increased time poverty. Individuals participate in more leisure activities in less leisure time, so they do not fully enjoy their leisure time. Moreover, with the improvement of new quality productive forces and human capital level, individuals are more inclined to participate in cultural appreciation, educating children, amateur learning, etc., activities. These activities are more like the extension of work time, so that people feel that leisure time is dominated. All these effects are significantly different in terms of gender, marital status, occupation, family size and income.

1. Introduction

Achieving sustainable development is urgently needed to address global issues. Promoting innovation, promoting economic growth, providing quality education to raise the level of human capital and eliminating all forms of poverty are the goals of sustainable development. In order to achieve sustainable development, countries need to achieve these goals one by one. However, in the process of development of each country, due to the differences in comprehensive national strength, there is a problem of sequencing in the realization of the goals, and there may be target conflicts in a certain stage of national development. As the largest developing country, China has experienced the coexistence of new quality productive force development, human capital level improvement and time poverty in the process of rapid economic development. In order to realize China’s sustainable development strategy, we should explore the main reasons for this phenomenon and take positive measures to deal with this situation. Over the past few decades, productivity has achieved a leap-forward development, and people’s material living standards have been greatly improved. However, material affluence has not been transformed into time affluence. More recently, most people are feeling persistent ‘time poverty’— they have too many things to do and not enough time to do them. Time poverty can, to a certain extent, harm people’s physical and mental health and well-being [1]. A survey by an Economic Observer correspondent shows that the average weekly working hours of employees in Chinese companies will still be growing in 2024. Since the reform and opening up, China’s productivity has achieved sustained and rapid growth. However, as China has entered a stage of high-quality development, traditional productivity has been unable to effectively solve the new major social contradictions. New quality productive forces have become an inherent requirement and an important focus for promoting high-quality development [2]. This also marks a new starting point for the development of China’s productive forces. According to the Seventh Population Census, the level of human capital of China’s residents has been rising, and the average number of years of education for people over 15 years old in 2020 was 9.91 years, 2.29 years longer than in 2000. However, data from the 2018 National Time Use Survey Bulletin show that the average labor time of participants in employed work activities has increased by 1 h and 24 min compared to 2008. The phenomenon of the coexistence of productivity development, rising levels of human capital and time poverty has emerged. As productivity levels and human capital levels rise, why do people experience time poverty? This has become a question worth considering.

Due to the negative consequences of time poverty, we need to analyze the reasons why time poverty appears in the development of new quality productive forces and the promotion of human capital to understand and reduce time poverty and promote human well-being. Given that time is a scarce resource, with only 24 h per person per day, the time poverty that people experience is often due to differences in the allocation and utilization of time. Therefore, this paper will explore how the level of new quality productive forces and human capital lead to increased time poverty from the aspects of the quality and quantity of time.

2. Literature Review

Time poverty describes the phenomenon of individuals not having enough time [3]. Some scholars use expressions such as ‘time pressure’, ‘time shortage’ and ‘time deficit’, but they all have the same connotation and can be explained from multiple perspectives of time utilization [4]. From the perspective of time length, time poverty refers to not having enough time to do other things (mainly leisure activities), and refers to overwork without leisure time [5,6]. From the perspective of time intensity, time poverty refers to the subjective feeling of insufficient time caused by high work intensity, fast pace of life and hurry [7]. From the perspective of time quality, time poverty refers to the fragmentation of time and the reduction of individual free time autonomy [8]. Many factors can contribute to time poverty, such as societal and institutional factors [3]. According to the definition of time poverty, the factors that affect the allocation of time may become the factors that cause time poverty.

Productivity level and human capital level are two important factors that determine and affect time allocation and utilization, so they are also important factors affecting time poverty. Productivity is the ability of human beings to create wealth. The characteristics of the productive forces of the natural form fundamentally determine the nature and development trend of the productive forces of the social form, which also determines the social formation. The new quality productive force is advanced productivity, which determines the socially necessary labor time and then has a decisive impact on the allocation of personal time. Under Marx’s theory of time, the development of new quality productive forces shortens the socially necessary labor time and provides the possibility of obtaining more free time [9]. Although, in theory, the development of productivity is conducive to shortening people’s working hours, in fact, with the development of new quality productive forces, digital technology is blurring the boundaries of traditional time division, and the length of time that individuals can control independently is gradually shrinking [10]. Some scholars have put forward the ‘Z’ hypothesis of the evolution of work time, which holds that work time decreases first, then increases, and finally decreases with the change in the social development stage [11].

The level of human capital is also one of the key factors affecting individual time use, and its changes regulate the individual’s living time allocation. Some survey data show that the level of human capital has an impact on working hours and leisure time. According to the data of the American Time Distribution Survey (ATUS), from 1965 to 2003, the leisure time of individuals with low human capital levels has increased greatly in the long run, with an average increase of 9 h per week [12]. From the data of the living time allocation survey of China, it is found that the higher the level of human capital, the longer the working hours and the less leisure time [13]. In addition, some researchers have found that as the level of human capital increases, people’s leisure time will not increase on average for all leisure activities, mainly in cultural activities, sports activities, reading and educating children and other activities. This is mainly affected by the social environment and personal values [14,15,16]. From the perspective of the mutual restriction and influence between various types of living time, when the level of human capital increases, leisure time can remain unchanged, but housework time decreases or work time increases [17]. However, some studies have shown that the decrease in market labor time mainly leads to an increase in leisure and entertainment time [18].

To sum up, first, existing studies have analyzed the relationship between productivity level, human capital level and time poverty, but there is a lack of research on new quality productive forces that will become an important force in promoting sustainable development. Therefore, based on the existing research, this paper further explores the relationship between new quality productive force level, human capital level and time poverty. Secondly, from the perspective of empirical research, on the one hand, when researchers discuss the problem of time poverty or time utilization, they mostly study it from a single type of time, such as work time or housework time. Because the time available to everyone every day is limited, the study for a certain type of time alone may lack the constraints of time limitation. This paper divides 24 h a day into four types of time to study and adds constraints to it to avoid such problems. On the other hand, the research lacks the study of the relationship between the three from the aspect of time quality, and this paper expands the research in this aspect. Thirdly, there are many studies on developed countries. This paper takes China as the main research object and increases the research on such problems in developing countries. As the fastest-growing and largest developing country, China’s research can provide a reference for other developing countries.

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. The Mechanism Analysis of the Influence of New Quality Productive Forces and Human Capital Level on Individual Time Utilization

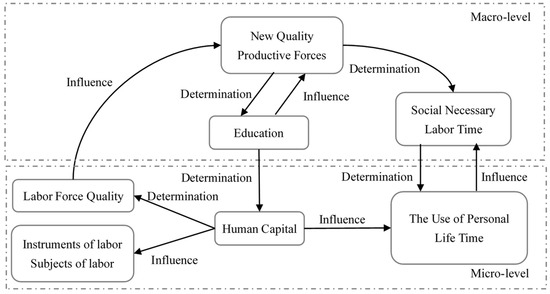

Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), has proposed that the new quality productive forces are primarily based on the transformation of laborers, the instruments of labor and the subjects of labor, as well as their optimal combination. A central hallmark of these forces is a significant increase in total factor productivity, and their defining characteristic is innovation, with a key focus on quality. In essence, they represent advanced productivity [19]. From the perspective of the historical process of the development of material productivity, new quality productive forces are a theoretical response to the fourth industrial revolution. The fourth industrial revolution is based on big data, cloud computing, the Internet of things, blockchain, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies as a breakthrough point, driving digital technology, life science and technology as the representative of the strategic emerging industries to achieve a leap in productivity [20,21]. The relationships between new quality productive forces, human capital level and time utilization are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The relationships between new quality productive forces, human capital and time utilization.

The development of productivity determines the way of labor and the pattern of labor, which also determines the working time and non-working time. The influence of productivity on time distribution and utilization mainly depends on the income effect and substitution effect. In the long run, the income effect is dominant, and the development of productivity will inevitably lead to the reduction of working time, but the whole process presents a ‘Z’ type, and the working time will experience a process of ‘decrease-increase-decrease’ [11]. The new productivity promoted by digital technology has improved production efficiency, but it will still cause an increase in working hours in a short time [22]. First, while the use of digital technologies has led to ‘automation’ and ‘intelligence’ in some tasks, in most areas, digital technologies have emerged as assistive technologies that enrich the way people work, thereby increasing labor time. Second, digital technology has a tendency to replace people’s labor in order to avoid unemployed workers spontaneously choosing to compress their necessary labor or extend the total labor time. Third, the part of the reduction in socially necessary labor time brought about by technological progress has not all been used for leisure; people have chosen to continue working. However, in the long run, with the further development of new productivity, people’s living standards have improved significantly. When people adapt to the new quality productive forces and lifestyle, their working hours will gradually decrease, and people will increase the time they actually spend on leisure.

The influence of human capital level on the utilization of life time mainly depends on its time economic value. The higher the level of human capital, the higher the time economic value. The opportunity cost of non-working hours is the amount of income reduction caused by giving up work. For workers with higher levels of human capital, non-market labor such as housework has higher opportunity costs, so they will devote more time to work. On the contrary, for workers with lower levels of human capital, the opportunity cost of non-market labor such as housework is lower, so they may be engaged in non-market labor such as housework [23].

Human capital and new quality productive forces are two factors that influence each other. The level of education development affects the level of new quality productive forces. Education can cultivate higher-quality workers, provide higher-tech labor materials, expand a wider range of labor objects and support higher levels of scientific and technological innovation. The development of new quality productive forces will promote the reform of education. The level of production development determines the purpose, content, method, means, scale and speed of education [24]. The development of education determines the level of personal human capital.

3.2. Time Utilization Model with New Quality Productive Forces and Human Capital

This paper extends Becker’s time allocation model [25] to study how the new quality productive forces and human capital level affect people’s time utilization. Wang extended the model to study the relationship between human capital level and time utilization [13]. This paper expands on his analysis by further extending. People’s essential time for life generally changes little, so the impact on work time, leisure time and housework time is analyzed. Mincer proposed that human capital level is an important factor affecting individual income [26]. The productivity level determines the income level of the society and further determines the individual income. Therefore, the wage is the function of the human capital level and the new quality productive force levels. denotes the level of human capital and denotes the level of new quality productive forces. Assume that there are two consumer goods and which, according to Becker’s theory, require market inputs and , and time and . Assuming that is leisure activity, it has a weak elasticity of time and market product substitution, and is housework activity, which has a higher elasticity of substitution. The production of these two consumer goods is represented by the CES production function, as shown in Equations (1) and (2); are alternative parameters.

The utility of the two types of goods to people is shown in Equation (3). The unit cost of the two types of goods is shown in Equations (4) and (5); and are the commodity prices, are unit cost and is assignment parameters.

The utility maximization decision is transformed into Equation (6).

where is the work time, is the total income, including labor and non-labor income. Due to the small change in the essential time for life, it is set to a fixed value; then, the remaining time of the day is . Solving the above maximization problem using the Lagrange multiplier method yields and . In order to facilitate the derivation, the influence of non-labor income is neglected here—that is, = . Since time spent on necessities of life is constant, focusing on the impact on work time and leisure time yields the impact on housework time. According to Shepard’s lemma, we can get the expression of work time and leisure time in Equations (7) and (8).

The derivatives of leisure time and work time on the level of human capital are shown in Equations (9) and (10).

The derivatives of leisure time and work time on the level of new quality productive forces are shown in Equations (11) and (12).

The impact of human capital can be obtained from Equations (9) and (10). Since , Equation (9) is greater than zero, so leisure time increases with the increase in the human capital level, and its increase is affected by the size of elasticity of substitution and . It can be seen from Equation (10) that the influence of human capital level on work time depends on the values of parameters , , and . The first term on the right side of the equation is negative, and the second term is positive. For groups with high economic value of time, the influence of is greater than , and they will choose to increase work time.

The impact of new quality productive forces can be obtained from Equations (11) and (12). In the short term, there may be a negative value of , which is mainly due to the improvement of a new productivity level, especially the application of digital technology, which will cause some people to be unemployed and cause a short-term decline in wage level caused by technological progress. However, in the long run, the value is positive, and technological progress will lead to the improvement of the whole productivity level, thus increasing the income of residents. From Equation (11), the first term on the right side of the equation is negative and the second term is negative in the short term and positive in the long term. Therefore, leisure time shows a tendency to decrease and then increase with the level of new quality productive forces. From Equation (12), the first term on the right side of the equation is negative, but the positive and negative values of the latter two terms depend on the values of parameters , , and . In the short term, since is negative, the second term is positive and the third term is negative. In the long run, since is positive, the second term is negative and the third term is positive. Therefore, the impact of new quality productive forces on work time depends on the influence of the three.

The influence of comprehensive human capital and new productivity on work and leisure time mainly depends on the influence of each parameter. Therefore, we further study the degree of influence through empirical research.

4. Variables and Data

4.1. Variable Selection

The level of New Quality Productive Forces. The ‘new quality productive forces’ have provoked extensive discussions in Chinese society and attracted a great deal of attention from foreign media. On the basis of an in-depth study of its theoretical connotation, some researchers have tried to measure the level of new quality productive forces in China. Based on the existing measurement results, this paper divides the new quality productive forces into different stages of development, which is used as the measurement indicator of the new quality productive force levels in this paper.

Searching for the literature containing ‘new quality productive forces’ in the title of core journals in China Knowledge Network as of June 2024, more than 1000 articles were found, among which 33 articles measured the new quality productive force levels, and researchers use different indicators and methods to measure. Fifteen articles (See Table 1) give the measurement results, which basically covered the measurement dimensions mentioned in the above 33 articles and can reflect the development level of China’s new quality productive forces. Based on these measurement results, the method of change point detection (ruptures’s Pelt algorithm) is used to divide the stages of the development of the new quality productive forces. Change point analysis is a method for detecting structural changes in time series. Change points divide time series into different parts. By identifying the change points of the time series of new quality productive force levels in 33 studies, it is found that 2017 and 2020 are two change points, and the calculation of the literature generally starts from around 2011. Therefore, this paper believes that the development of new quality productivity has experienced four stages of development, namely, before 2011, 2012–2017, 2018–2020 and 2021–2024. Ren argues that at the two points when China’s economy enters the new normal and enters the new era of socialism, the level of new quality productive forces undergoes a large change [27], which further validates the correctness of the choice of change points in this paper.

Table 1.

Data source of new quality productive forces stage division.

The Level of human capital. Human capital is the sum of knowledge, skills, physical strength and the ability to acquire information possessed by laborers. However, due to the limitation of survey data, only data on the educational level of laborers can be obtained, so the educational level is used as a proxy variable for human capital. Human capital measurement methods based on education level are also frequently used in research [28]. The level of education is highly correlated with human knowledge, skills and the ability to acquire information, and indicators such as years of education and school enrolment have also become more commonly used as proxies for human capital.

Time poverty. Time poverty refers to the lack of individual time. Some scholars use the ‘time poverty line’ to assess it. We first assess the time poverty status of residents based on whether the sum of their weekly paid work, housework and commuting time exceeds 64 h [29,30,31]. In four consecutive surveys, 43.02%, 36.96%, 45.11% and 43.54% of the residents face time poverty, with an average proportion of 42.18%, revealing that nearly half of the population is suffering from time poverty. Time poverty is a complex phenomenon, which cannot be fully reflected only by using the ‘time poverty line’. Therefore, we select indicators in the two dimensions of quantity and quality of time allocation, and deeply explore the impact of the development of new quality productive forces and the improvement of human capital level on individual time poverty. At the quantitative level of time, we selected four variables: work time, essential time, housework time and leisure time, aiming to analyze their changing trends. The time selected in this paper is the average daily time calculated by . In terms of time quality, we focus on the quality of leisure time, and we conduct an in-depth exploration into the richness of leisure activities and personal leisure preferences. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of variables.

Control variables: gender, age, marital status, income, household size, occupation. See Table 2.

4.2. Data Source

The main object of this paper is China. China is the largest developing country. It is experiencing rapid economic and technological development. The problem of time poverty is prominent. Studying China’s problems can provide references for other developing countries. The data for this paper comes from the Residents’ Life Time Allocation Survey, which was conducted in 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 by the Leisure Economy Research Centre of the Renmin University of China. Although the survey data is affected by survey methods, implementation process and sample size, compared with the census data, it may be insufficient in reflecting the population characteristics. However, by improving the survey methods, the representativeness of the sample is gradually enhanced, and effective samples can be obtained for research under financial and time constraints. The sampling method of the survey data in this paper is multi-stage random sampling. This method has high sampling accuracy, small sampling error, strong sample representativeness, and can also save costs and improve efficiency. The corresponding effective sample sizes are 1657, 1106, 830, and 1597, respectively. The questionnaire adopts a self-filling structure, which consists of a tripartite structure. The first part contains the respondents’ fundamental elements, such as gender, age, income and education level, etc. The second part includes two daily time allocation tables for weekdays and weekends, including 29 activities, 15 of which are leisure activities. Each table regards every 10 min as a unit; as a result, a day is divided into 144 time periods, and the respondents are required to fill in the unique items in each time period. The third part collects information about the respondents’ involvement in specific activities. The questionnaire is filled in by the respondents themselves, which is the expression of their real thoughts. Thus, the survey data are ensured to be true, objective and accurate.

4.3. The Changes in Residents’ Various Life Times

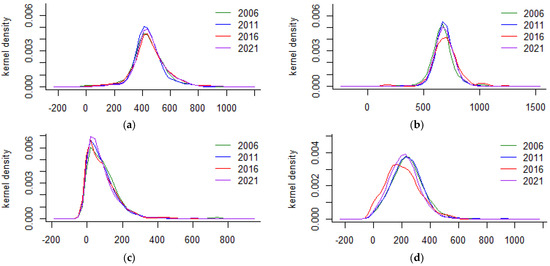

Figure 2 shows the kernel density (Gaussian kernel estimation) of residents’ living times in four survey years. It can be seen that in the past 15 years, from the perspective of the average daily work time, the main peak position of the kernel density curve has shifted slightly to the right, and the height of peak is gradually increasing, which shows that residents’ work time have increased slightly, and the difference in work time between residents is gradually narrowing. From the perspective of the average daily life essential time, the height of peak has an upward trend, while the main peak position has not changed, which indicates that the essential time required by residents has basically not changed, but the difference in life essential time between residents has narrowed. From the average daily housework time, the main peak position has shifted slightly, the height of the peak has gradually increased and there is a clear right trail, indicating that residents’ housework time has a slightly increased trend; the difference between residents’ housework time is gradually narrowing, but some residents’ housework time is still longer. From the average daily leisure time, the main peak position has shifted to the left, and the height of the peak has a downward trend, indicating that residents’ leisure time has a decreasing trend, and the difference in leisure time between residents has an expanding trend.

Figure 2.

The kernel density distribution of residents’ living time from 2006 to 2021. (a) Work time; (b) Essential time; (c) Housework time; (d) Leisure time.

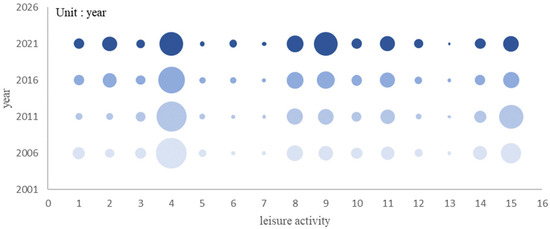

Figure 3 shows the change in the average participation time of residents participating in 15 leisure activities in four survey years. The average participation time is obtained by calculating the average time of residents’ participation in leisure activities on the rest day. In the four survey years, residents spent more time watching TV, walking in the park, participating in other recreations, rest and other leisure activities, and less time watching exhibitions and participating in public welfare activities. From the perspective of the change of participation time, the time for residents to read newspapers, watch film and drama performances and participate in other recreations has gradually increased. The time for residents to watch TV, listen to the radio, visit relatives and friends and participate in other leisure activities has gradually decreased.

Figure 3.

The average participation time of residents’ leisure activities from 2006 to 2021. Notes: 1–15 represent acquiring cultural and scientific knowledge, reading newspapers, reading books, watching television, listening to radio, watching film and drama performance, watching exhibitions, walking in the park, other recreations, physical exercise, rest, educating children, public welfare activities, visiting relatives and friends, other leisure activities, respectively. The color of the dots represents the year of the survey, and the size of the dots represents the time to participate in leisure activities.

5. An Empirical Analysis

5.1. The Impact on Various Types of Life Time

5.1.1. SUR Regression

This paper studies the influence of new quality productive forces and human capital level on work time, life essential time, housework time and leisure time, and seeks the reasons for personal time poverty. Since the unobservable factors of the individual affect the four types of life time at the same time, the disturbance terms of the four equations are related, and the time available to each person is 1440 min per day. Therefore, we consider using constrained seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) to improve the efficiency of estimation. We impose constraints on the coefficients of human capital level and new quality productive force levels according to the proportion of various types of time in the survey. The model constructed is shown in Equation (13), and the symbols in the equation are explained in Table 2. The dependent variable is logarithmically processed, and the estimation results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimation results of SUR model.

It can be seen from Table 3 that the level of new quality productive forces and human capital has an impact on work time, essential time, housework time and leisure time. With the improvement of the education level of workers, people’s work time and leisure time have increased, housework time has decreased and the essential time for life has not changed. Under the condition of controlling gender, age, work occupation, marital status, household size and household income, the education level of workers increased by a level, people’s work time increased by 0.014%, housework time decreased by 0.126% and leisure time increased by 0.053%.

The impact of the level of new quality productive forces on work time shows an ‘inverted U-shape’ (the development stage of new quality productive forces corresponding to the highest point is 3). Before 2020, with the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces, personal work time is in a stage of rapid increase. After 2020, with the improvement of the level of new quality productive forces, personal working hours are still increasing, but the rate of the increase gradually declined. Therefore, when the level of new quality productive forces develops to a certain extent, personal work time will decrease. Currently, Chinese people are still in the stage where personal working hours are increasing. The level of new quality productive forces has a positive impact on the essential time of life and housework time. The level of new quality productive forces increases by one level, the essential time of people’s lives increases by 0.005% and the time of housework increases by 0.113%. Why does housework time not decrease with the increase in new quality productive force levels? Some scholars have pointed out that although the level of productivity has increased, and various machines have emerged to replace human beings in housework, there are more household appliances, and the time spent on their maintenance, sorting and repair will increase, which increases some invisible housework time [32]. The impact of the level of new quality productive forces on leisure time presents a ‘U-shape’ (the lowest point corresponding to the development stage of new quality productive forces is 3). Before 2020, with the increase in the level of new quality productivity, personal leisure time was in a stage of rapid decrease. After 2020, with the improvement of the level of new quality productive forces, although personal leisure time is still decreasing, the rate of the decrease gradually declined. Therefore, when the level of new quality productive forces develops to a certain extent, personal leisure time will increase. At present, Chinese people are still in the stage where personal leisure time is decreasing, with an average decrease of 0.078%.

To sum up, under the effect of new quality productive force levels and the human capital level, individual work time shows an increasing trend, while in non-working hours, the time for housework and leisure tends to decrease. The increase in work time and the decrease in leisure time are some of the reasons why people feel time poverty.

5.1.2. Robustness Test of the Impact on Various Types of Life Time

The tail processing and IV (instrumental variable) approach are used to verify the robustness of the basic model. The main independent variables were tailed at the 5% level, and the regression results are shown in Table 4. The results show that the parameter estimation and significance of the variables have not changed significantly, indicating that the results of the basic model are robust.

Table 4.

Estimation results of tailings processing.

SUR regression analysis may have endogenous problems. First of all, there may be other factors affecting work and leisure time, but this paper does not take those factors into account. These factors will lead to errors in the causal effect of regression coefficient estimation. Secondly, there may be a reverse causal effect. Changes in personal time allocation may prompt people to obtain higher education and enhance human capital. Moreover, the allocation of time, especially leisure time, has an impact on labor productivity [33], which in turn has an impact on new quality productive forces. These problems will lead to the inconsistency of estimation. In this paper, the compulsory education system is used as an IV of human capital. The compulsory education system causes a difference in the number of years of education received by residents. Fang et al. verified that the compulsory education law can be used as IV of education level [34]. The full-time equivalent of research and development personnel is selected as the IV of new quality productive forces. The core of new quality productive forces is innovation. The number of R&D personnel represents the power of innovation and is not directly related to personal time allocation. The first-stage regression results show that the regression coefficients of the education level and new quality productivity to instrumental variables are significant, and the F values are 1299.65 and 4523.32, respectively, so there is no problem with weak instrumental variables. The second-stage regression results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

SUR regression results (IV).

Compared with Table 3, the direction and significance of the coefficient of the new quality productive forces and human capital level estimated by the IV have not changed, but the magnitude of the coefficient is different, and the coefficient is relatively large. The human capital level of workers increased by a level, people’s work time increased by 0.344%, housework time decreased by 2.711% and leisure time increased by 1.217%. The impact of the level of new quality productive forces on work time still presents an ‘inverted U-shape’ (the highest point is 3). The level of new quality productive forces has a positive impact on the essential time and housework time. The level of new quality productive forces has increased by a level, people’s essential time has increased by 0.009%, and housework time has increased by 0.210%. The impact of the level of new quality productive forces on leisure time is still ‘U-shaped’ (the lowest point is 5).

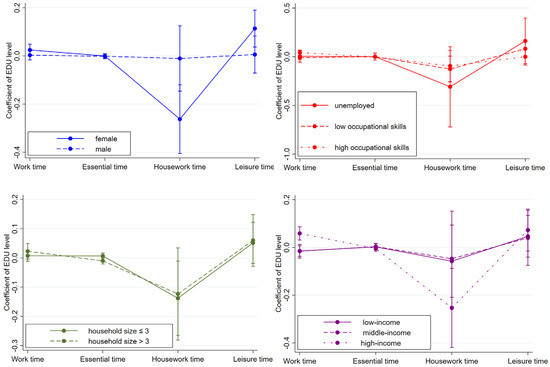

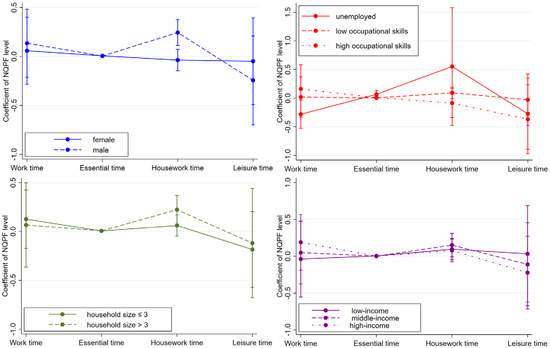

5.1.3. Heterogeneity Analysis of the Impact on Various Types of Life Time

Due to different individual characteristics, the impact of human capital and new quality productive force levels on various types of life time of individuals is also different. Therefore, we further study this impact by grouping according to gender, occupation, household size and income level. The results are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Group analysis of the impact of human capital level on various types of life time.

Figure 5.

Group analysis of the impact of new quality productive force levels on various types of life time.

From Figure 4, it can be seen that with the improvement of human capital level, women reduce more housework time than men, but increase more work time and leisure time than men. This suggests that women are more likely to feel time poverty as their human capital levels rise, as this frees them from housework but puts them into market labor. In terms of work occupation, with the improvement of human capital level, compared with the employed, the unemployed reduce more housework time and increase more leisure time. Compared with individuals with low occupational skills, individuals with high occupational skills have more reduction in housework time, but more increase in work time, and less increase in leisure time. Therefore, individuals with high occupational skills may feel the most time poverty, followed by individuals with low occupational skills, and the unemployed feel the least time poverty. In terms of household income, with the improvement of human capital level, the individual’s housework time of higher-income households decreases the most, and the work time also increases the most, but the increase in leisure time is less different from that of middle-income households and low-income households. There is little difference in the distribution of the four types of life time between middle-income households and low-income households. This reflects that those individuals in high-income households feel more serious time poverty. The impact of human capital level on various types of life time is basically no difference in household size.

It can be seen from Figure 5 that with the improvement in new quality productive forces, women’s leisure time decreases more than men’s, while work time and housework time increase more than men’s, especially housework time. This shows that the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces first brings more housework and market labor to women, so women feel more time poverty. In terms of work occupation, with the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces, compared with the employed, the unemployed had increased housework time, but their work time has decreased more, so the total working hours have increased less. Compared with individuals with low occupational skills, individuals with high occupational skills have the most reduction in leisure time and the most increase in work time. Therefore, in terms of work occupation, individuals with high occupational skills still feel the greatest time poverty. In terms of household size, with the improvement of new quality productive force levels, individuals from larger household sizes increase more housework time. In terms of household income, with the improvement of new quality productive forces, the leisure time of the individuals in higher-income households decreases the most, and the work time also increases the most, followed by middle-income households, and the smallest increase in low-income households, which reflects that high-income households feel greater time poverty.

5.2. The Influence on the Richness and Preference of Leisure Activities

5.2.1. Poisson Regression and Multinomial Logit Regression

This part explores the causes of time poverty from the perspective of time quality. In the study of the quantity of time, the time is divided into four categories, work time, essential time, housework time and leisure time. Because of the first three types of time, for people engaged in fixed activities for basic life, the length of time increases regardless of whether the quality of time is good or bad, which will negatively impact time poverty, so the study of its quantity can explore its impact on time poverty. Leisure time is for rest, entertainment, relaxation, the pursuit of personal interests and hobbies, etc. The influence of its quantity and quality is quite different—for example, having long leisure time, but the quality of leisure time is poor—and will also increase time poverty. Therefore, the exploration of time quality is carried out from the quality of leisure time. Mattingly et al. defined time quality in terms of contamination and fragmentation [35]. Contamination refers to whether the main activities carried out over a period of time are affected by other activities; fragmentation means the main activity is fragmented into a number of distinct episodes. This definition is widely used by subsequent researchers, and this paper also uses this definition to study the quality of leisure time. The richness of leisure activities and preference for leisure activities are selected to study. The richness of leisure activities refers to the number of activities involved in leisure time. When the leisure time is certain, more activities are involved; to a certain extent, this shows that people cannot concentrate on completing an activity within a period of time, so the degree of fragmentation of leisure time is higher. Preference of leisure activities is the activity that someone participates in the longest during their leisure time. According to preference of leisure activities, it can be judged whether leisure time is affected by the extension of other time activities. The level of new quality productive forces and human capital not only affects the length of workers’ work and leisure times, but also affects the content of leisure time activities. An in-depth study of this impact is needed to explore the reasons for personal time poverty. The leisure time of weekdays is greatly affected by individual work, which cannot fully reflect the utilization of leisure time by individuals. Therefore, the leisure time of weekends is selected. Leisure time in the questionnaire contains 15 activities. Whether an individual participates in an activity is judged by whether he or she has time for each activity, with participation recorded as 1 and non-participation recorded as 0. The number of leisure activities an individual participated in is obtained by summing the results of participation in each of the 15 activities, which represents the richness of leisure activities. The variable is a non-negative integer, so the Poisson model is used to study the impact on the richness of leisure activities. The results are shown in Table 6. The 15 leisure activities in the questionnaire were merged and classified. Acquiring cultural and scientific knowledge, reading newspapers and reading books were merged into ‘amateur learning’. Watching TV and listening to the radio were merged into ‘watching TV’. Watching film and drama performances and watching exhibitions were merged into ‘Cultural appreciation’. Walking in the park and physical exercise were merged into ‘sport’. Other recreations, rest, public welfare activities and other leisure activities merged into ‘other activity’. Educating children and visiting relatives and friends were each in their own categories. Taking the one that individuals spend the longest time in seven activities as their leisure preference, the leisure preference variable is a categorical variable of 1–7; the multinomial logit model is used to study the impact on individual leisure preference. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of the impact on the richness of leisure activities and leisure preferences.

From Table 6, the level of human capital has a positive impact on the richness of leisure activities. The level of education of individuals increases by a level, and the number of leisure activities they participate in increases by 1.05. The higher the level of human capital is, the more leisure activities individuals participate in, which is similar to the research of Stalker et al. [36]. Warde et al. use ‘cultural omnivorousness’ to explain why individuals with high human capital levels have greater preferences for different leisure activities [37]. The influence of the level of new quality productive forces on the richness of leisure activities presents a ‘U’ type (the development stage of new quality productive forces corresponding to the lowest point is 0). Therefore, with the development of new quality productive forces, individuals will participate in more leisure activities.

To sum up, in the process of improving the level of new quality productive forces and human capital, the leisure activities that individuals participate in are becoming increasingly abundant, but do not bring real relaxation. On the one hand, with the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces and human capital, individual leisure time has decreased, but the number of leisure activities involved has increased, which has increased the utilization rate of leisure time, but may cause the fragmentation of leisure time and a decline in leisure time quality. Individuals participate in multiple leisure activities at the same time, and there may be conflicts of goals, so that they feel that time is insufficient [38]. Moreover, when leisure time is divided into multiple activities, people cannot fully engage in each activity and lack deep leisure experience, thus affecting the overall quality of leisure time. On the other hand, a high human capital level generally corresponds to high income and high status. Although people have more choices, they are more anxious about their status. Therefore, they usually cannot really enjoy leisure activities [39]. Some studies have shown that “acceleration“ is the basic feature of modern society, including the acceleration of science and technology, the acceleration of social change and the acceleration of life pace, which forces people to speed up the pace of life. This kind of acceleration brings more choices to individuals. For example, the leisure activities involved are more abundant, but it also brings uncertainty. People find themselves in an unstable state, and their social status may change at any time. Therefore, people cannot appreciate the joy of leisure activities but feel the time poverty [40].

From the perspective of leisure preference, with the improvement of human capital level, people’s leisure preference is ranked as ‘cultural appreciation, educating children, amateur learning, sport, visiting relatives and friends, watching TV and other activity’. With the improvement of the level of new quality productive forces, people’s leisure preferences are ranked as ‘other activity, cultural appreciation, educating children, amateur learning, sport, visiting relatives and friends and watching TV’. As Adorno pointed out, in the context of a highly industrialized society, the boundaries between work and leisure may be more blurred, which will lead to the function and connotation of ‘leisure time’ being defined by ‘work’ rather than an independent field of behavior [41]. Under the effect of the improvement of new quality productive force levels and the human capital level, people are more inclined to participate in leisure activities such as cultural appreciation, educating children, and amateur learning. Such leisure activities have the function of improving human capital. Therefore, this type of leisure activity is likely to be an extension of work time and not entirely dependent on people’s subjective choices. Therefore, their leisure time has a contamination problem: it is not pure leisure time.

Due to the fragmentation and contamination of people’s leisure time, the quality of people’s leisure time is relatively poor, which is also an important reason for people’s time poverty.

5.2.2. Robustness Tests of the Influence on the Richness and Preference of Leisure Activities

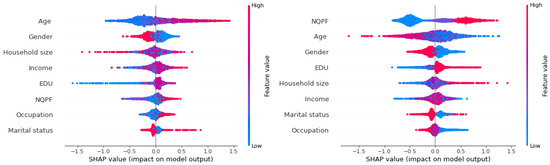

The SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanation) and IV approach are used to verify the robustness of the basic model. SHAP is a game-theory-based method for decomposing model predictions into the aggregate of the SHAP values, and it can reflect the marginal contribution of features. It can analyze the role of different features in the prediction process of the machine learning model [42], and it is widely used in the explanation of various models [43].

Using the SHAP model, leisure richness and leisure preference are processed. The number of leisure activities participated in greater than its mean (2.86) is denoted as 1, and less than its mean is denoted as 0. Among the seven types of leisure activities, people’s leisure preference for watching TV and visiting relatives and friends are denoted as 0, and the other is denoted as 1. LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine) is used to classify the richness and preference of leisure activities.

The left and right figures of Figure 6 represent the effects on the richness of leisure activities and preference in leisure activities, respectively. The SHAP values of the human capital level imply that the impact of human capital level on the richness of leisure activities shows an increasing trend with increasing education level, and people with high human capital level are more inclined to participate in leisure activities that can improve the level of human capital, such as amateur study. The SHAP values of new quality productive force levels imply that the impact of new quality productive force levels on the richness of leisure activities also shows an increasing trend with increasing new quality productive force levels. The higher the level of new quality productive forces, the more people are inclined to participate in leisure activities that can improve the level of human capital.

Figure 6.

Beeswarm plot of the effects on the richness and preference of leisure activities.

Poisson and multinomial logit regression analysis may also have endogenous problems. The IV method is still used to solve the endogenous problem, and the IV of new quality productive forces and human capital level is consistent with the above. The first-stage regression results are the same as above, and there are no weak instrumental variables. The second-stage regression results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

IV results of the impact on the richness of leisure activities and leisure preferences.

Compared with Table 6, the direction a of the influence coefficient of the new quality productive forces and human capital level estimated by the IV has not changed, but the t magnitude of the coefficient is different. From the perspective of the richness of leisure activities, the level of human capital of individuals increases by a level, and the number of leisure activities they participate in increases by 3.40. The influence of the level of new quality productive forces on the richness of leisure activities presents a ‘U’ type (the lowest point is also 0). From the perspective of the preference of leisure activities, with the improvement in human capital level, people’s leisure preference is ranked as ‘cultural appreciation, amateur learning, educating children, sport, other activity, visiting relatives and friends and watching TV’. With the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces, people’s leisure preferences are ranked as ‘other activity, educating children, cultural appreciation, sport, amateur learning, visiting relatives and friends and watching TV’.

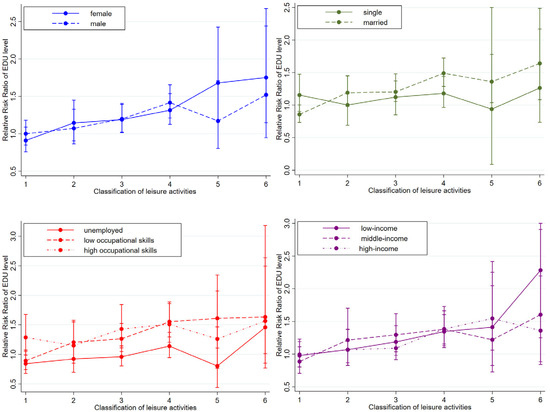

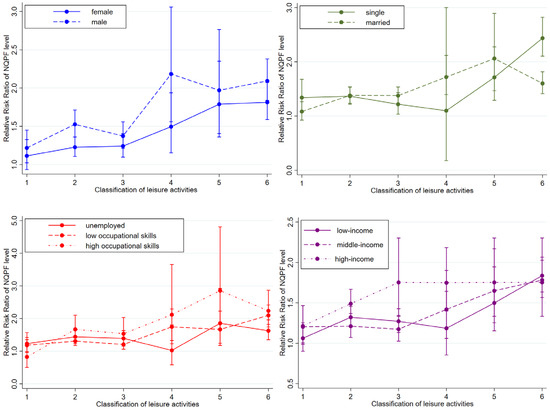

5.2.3. Heterogeneity Analysis of the Influence on the Preference of Leisure Activities

Due to different individual characteristics, the impact of human capital and new quality productive force levels on leisure preference is also different. Therefore, we further study this impact by grouping according to gender, marital status, occupation and income level. The results are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Group analysis of the impact of human capital level on leisure preference. Note: 1–6 denotes other activity, visiting relatives and friends, sport, amateur learning, educating children and cultural appreciation, respectively.

Figure 8.

Group analysis of the impact of new quality productive force levels on leisure preference. Note: 1–6 denotes visiting relatives and friends, amateur learning, sport, educating children, cultural appreciation and other activity, respectively.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that with the improvement of human capital level, compared with men, women prefer to educate their children, and the activities of educating their children may cause physical and mental fatigue, so women are more likely to feel time poverty. In terms of marital status, with the improvement of human capital, married individuals have a higher preference for various leisure activities than single individuals, especially for educating children and cultural appreciation activities. In terms of work occupation, with the improvement of human capital level, the employed have a higher preference for various leisure activities than the unemployed, and individuals with higher occupational skills prefer amateur learning activities, while individuals with lower occupational skills prefer to educate their children. In terms of household income, with the improvement of the human capital level, individuals from high-income households prefer to educate their children and engage in amateur learning activities, individuals from middle-income households prefer amateur learning, sports and visiting activities, while individuals from low-income households prefer cultural appreciation activities.

It can be seen from Figure 8 that with the improvement of the level of new quality productive forces, men’s preference for all kinds of leisure activities is higher than that of women. In terms of marital status, with the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces, married individuals still have higher preferences for a number of leisure activities compared to single individuals, especially for educating children and cultural appreciation activities. In terms of work occupation, with a higher level of new quality productive forces, individuals with higher occupational skills have a higher degree of preference for various leisure activities (excluding visiting relatives and friends), and prefer amateur learning, educating children and cultural appreciation activities. Individuals with lower occupational skills prefer to educate their children. In terms of household income, with the improvement in the level of new quality productive forces, individuals in families with higher incomes have higher preferences for various leisure activities. Individuals in higher-income families prefer educating children, sports and amateur learning activities. Individuals in middle-income families prefer educating children and cultural appreciation activities, while individuals in low-income families prefer other recreational activities.

In summary, women, married individuals, individuals with higher occupational skills and individuals with higher household income are more inclined to participate in leisure activities such as amateur learning, educating children and cultural appreciation. This also shows that the leisure activities people choose at this stage may be an extension of work, thus their leisure time has a contamination problem and the quality of leisure time is poor.

6. Discussion

The coexistence of new quality productive force development, human capital level improvement and time poverty not only exists in China, but also in other developing countries such as India. The core of new quality productive forces is innovation. This paper uses the ‘India Innovation Index’ released by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) as a representative indicator of India’s new quality productive forces and combines India’s time use survey data (2019) to analyze India’s 35 states. The results are shown in Table 8. It can be seen that with the improvement of education level, work time gradually increases, leisure time gradually decreases and housework time decreases, but leisure time will increase when education level reaches a higher level. By improving the innovation level, working time shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing, while leisure time shows a trend of decreasing first and then increasing. The trend of housework time is not obvious, but it also shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing. This is similar to the situation in China. This also shows that the development of new quality productive forces is conducive to reducing time poverty.

Table 8.

The results of India.

7. Conclusions

According to the survey data, more than 40% of individuals feel the effects of time poverty. Under the combined influence of new quality productive forces and human capital level, people’s work and life essential time show an increasing trend, while housework and leisure time are gradually decreasing. The increase in working hours and the decrease in leisure time aggravate individuals’ time poverty. This effect varies in terms of gender, occupation, family size and income. Women [44], individuals with higher occupational skills, individuals with larger household sizes or individuals with higher household incomes have greater time poverty. However, with the further development of new quality productive forces, people’s working hours will be reduced and leisure time will be increased. Based on our findings, we suggest that new quality productive forces should be vigorously developed to create more leisure time for people. Secondly, in the process of improving the level of new quality productive forces and human capital, the leisure activities that people participate in become more and more abundant. But individuals participating in more leisure activities in less leisure time may lead to a decline in the quality of leisure time, and the development of new quality productive forces driven by digital technology has also brought a lot of uncertainty to people’s work and life, such that people cannot really enjoy leisure time, which is also the cause of people’s time poverty. Therefore, we suggest that people should arrange leisure activities to avoid the decline of leisure experience caused by participating in multiple activities and improve their ability to cope with uncertain risks in the process of improving the level of human capital. Individuals should focus on learning diverse skills and use fragmented time for lifelong learning to improve productivity and speed to adapt to new technologies. Third, the higher the level of new quality productive forces and human capital, the more people tend to participate in cultural appreciation activities, educating their children and amateur learning activities. This phenomenon is more likely to occur in women, married individuals, individuals with higher occupational skills or individuals with higher household income. Such leisure activities are more like an extension of working hours which gives people a sense that leisure time is continuously dominated by working hours. So, we suggest that people should plan their own leisure time and transform leisure time into free time to realize the all-round development of individuals. We encourage individuals to conduct self-examination and interest exploration and actively plan leisure time to ensure that leisure activities are both in line with personal development needs and can bring pleasure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W. and Z.D.; methodology, Z.D.; software, Z.D.; formal analysis, Q.W. and Z.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.D.; writing—review and editing, Q.W. and Z.D.; supervision, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the: (i) National Social Science Foundation of China: ‘Research on Promoting the Domestic Demand via the Leisure Consumption’ (Grant Number: 21ATJ004), (ii) National Social Science Foundation of China: ‘Research on ICT Capital Accounting Based on Macro and Micro Data Integration’ (Grant Number: 20BTJ002), (iii) Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation Project ‘Improvement of rolling annual price index estimation method based on mismatched projects’ (Grant Number: 2021MS01023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent were waived due to the use of retrospective and de-identified data. This study adhered to the guidelines set forth by the National Science and Technology Ethics Committee of China.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are in Chinese and are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whillans, A.V.; Dunn, E.W.; Smeets, P.; Bekkers, R.; Norton, M.I. Buying time promotes happiness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8523–8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiushi Commentary. Understanding new quality productive forces and accelerating their development. Qiushi J. 2024. Available online: https://subsites.chinadaily.com.cn/Qiushi/2024-05/11/c_985265.htm (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Giurge, L.M.; Whillans, A.V.; West, C. Why time poverty matters for individuals, organisations and nations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.M.; Yang, S.T.; Kong, X.S.; Liu, Z.Z.; Ma, R.Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, X.Y.; Cao, P.L.; Bao, R.J.; et al. Conceptualization of time poverty and its impact on well-being: From the perspective of scarcity theory. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 32, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardasi, E.; Wodon, Q. Working long hours and having no choice: Time poverty in Guinea. Fem. Econ. 2010, 16, 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.R.; Masuda, Y.J.; Tallis, H. A measure whose time has come: Formalizing time poverty. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazdins, L.; Welsh, J.; Korda, R.; Broom, D.; Paolucci, F. Not all hours are equal: Could time be a social determinant of health? Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.A. Time and wealth: The role of time and temporalities for sustainable patterns of consumption. Time Soc. 2001, 10, 367–385. Available online: https://tas.sagepub.com/content/10/2-3/367 (accessed on 5 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.P. Research on new quality productive forces empowering common prosperity in the perspective of Marx’s theory of time. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Afanasov, N.B. The Time-Pressure Paradoxes in the Digital Age. In Voprosy Filosofii; Institute of Philosophy: Moscow, Russia, 2020; pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.D.; Yang, H.Q. An Evolution Model and Contemporary Characteristic on Working Time. Res. Econ. Manag. 2012, 12, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, M.; Hurst, E. Measuring trends in leisure: The allocation of time over five decades. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 969–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Wei, J.J. A Study on the Inequality of Leisure Time in Beijing. Soc. Sci. Beijing 2017, 9, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Borodulin, K.; Laatikainen, T.; Lahti-Koski, M.; Jousilahti, P.; Lakka, T.A. Association of age and education with different types of leisure-time physical activity among 4437 Finnish adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.E.; Song, Y.J. Time or money: The relationship between educational attainment, income contribution, and time with children among Korean fathers. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Calero, J. The non-monetary effects of education on leisure: Analysis of the use of time in Spain. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2019, 36, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronau, R. Leisure, home production, and work--the theory of the allocation of time revisited. J. Political Econ. 1977, 85, 1099–1123. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1837419 (accessed on 5 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, D.; Lee, J.; Hamermesh, D.S. A gift of time. Labour Econ. 2013, 24, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. Understanding Xi’s Quotes on New Productive Forces. Xinhuanet, 2024. Available online: https://english.news.cn/20240202/02e54dbeac9442dba89228084974819b/c.html (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Liu, W. Scientific understanding and practical development of new quality productive forces. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 59, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Jiang, N.; Kuang, X. Towards an accurate understanding of ‘new quality productive forces’. Econ. Political Stud. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.B. The paradox between scientific and technological progress and acquisition of free time. J. Dialectics Nat. 2023, 45, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.Y. The Time Allocation of Chinese; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.X. Further deepening education reform to promote the development of new quality productive forces. Chin. J. Distance Educ. 2024, 44, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. A theory of the allocation of time. Econ. J. 1965, 75, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H. Human Capital and Income Inequality. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2018, 23, 554–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.P. The logic of the modern transformation of productivity to form new quality productive forces. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Glawe, L.; Wagner, H. Is schooling the same as learning?—The impact of the learning-adjusted years of schooling on growth in a dynamic panel data framework. World Dev. 2022, 151, 105773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.L.; Marinho, E. Time poverty in Brazil: Measurement and analysis of its determinants. Estud. Econ. 2012, 42, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nackerdien, F.; Yu, D. Defining and measuring time poverty in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2022, 40, 560–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiznado Aitken, I.; Palm, M.; Farber, S. Exploring the interplay of transportation, time poverty, and activity participation. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 26, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C. Exploring the mystery of the coexistence of economic prosperity and time pressure—An economic analysis to the division of labor based on shadow work and technological progress. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, D.; Wei, X.; Wu, D.; Cui, N.; Nijkamp, P. Leisure time and labor productivity: A new economic view rooted from sociological perspective. Economics 2019, 13, 20190036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Eggleston, K.; Rizzo, J.A.; Rozelle, S.; Zeckhauser, R.J. The Returns to Education in China: Evidence from the 1986 Compulsory Education Law; NBER Working Paper No. 18189, National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, M.J.; Bianchi, S.M. Gender Differences in the Quantity and Quality of Free Time: The U.S. Experience. Soc. Forces 2003, 81, 999–1030. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3598184 (accessed on 5 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Stalker, J.G. Leisure diversity as an indicator of cultural capital. Leis. Sci. 2011, 33, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, A.; Gayo-Cal, M. The anatomy of cultural omnivorousness: The case of the United Kingdom. Poetics 2009, 3, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, J.; Evangelidis, I.; Aaker, J. Pressed for time? Goal conflict shapes how time is perceived, spent, and valued. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ma, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.; van Prooijen, J.W.; Dong, M.; Yuan, Y. Why do we never have enough time? Economic inequality fuels the perception of time poverty by aggravating status anxiety. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 63, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, H.; Trejo-Mathys, J. Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, T.W. Critical Models; Lin, N., Translator; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning. 2019. Available online: https://originalstatic.aminer.cn/misc/pdf/Molnar-interpretable-machine-learning_compressed.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Wang, Q.Y.; Jiang, Y.Y. Leisure time prediction and influencing factors analysis based on LightGBM and SHAP. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers YV, D.M. Time poverty: Conceptualization, gender differences, and policy solutions. Soc. Philos. Policy 2023, 40, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).