Abstract

As sustainability becomes more critical to corporate strategy and performance, firms, investors, and researchers must continue to refine methods for measuring and addressing the gap between rhetoric and reality. Closing this gap is crucial to ensuring that externally oriented ESG claims are supported by genuine internal actions that benefit both the firm and society at large. To address this issue, this study introduces a theoretically driven framework to assess the alignment (or lack thereof) between firms’ ESG policies and their actual implementation. By proposing a more granular and objective measure, we address a gap in the existing literature. Additionally, we empirically validate this framework using data from ASSET4, providing insights into the extent and persistence of this phenomenon using a sample of S&P 1500 firms from 2016 to 2022. Our results reveal that misalignment between internal actions and external endorsements in managing environmental and social issues is both significant and persistent across the years analyzed. Over 80% of the sample firms exhibit this misalignment, underscoring its prevalence within the sample. In more recent years, however, firms have shown a clear tendency to prioritize internal actions over initiatives aimed at externally endorsing their efforts. Building on the framework we propose to measure ESG policy–practice decoupling, along with the empirical analysis we conducted, we discuss its broader implications and outline several opportunities for future research.

Keywords:

ESG; policy–practice decoupling; internal actions; external actions; investors; stakeholders; ASSET4 1. Introduction

In response to growing stakeholder pressures, firms undertake an increasing number of voluntary environmental, social, and governance (ESG) actions. Responding to such pressures through ESG actions helps firms assure legitimacy in the eyes of investors and other stakeholders, granting firms access to crucial strategic resources (Bromley & Powell, 2012) [1]. Firms respond to stakeholder pressures through two types of ESG actions. Internal actions focus on achieving structural changes and often involve adopting widely accepted ESG practices, while external actions aim to secure endorsement from external constituents through effective communication of these actions (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016) [2].

Anecdotal evidence suggests that firms undertake external and internal ESG actions in many ways and to different extents, resulting in a gap between actual practices and proclaimed policies. Policies may be formally communicated but not effectively implemented or may differ significantly from what is practiced on the ground. This phenomenon is known as ESG policy practice decoupling (Tashman, Marano & Kostova, 2019) [3]. In Canada, for example, a group of investors filed a complaint with the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), the equivalent of the Security Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States of America (USA), against five Canadian banks that had publicly committed to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions while continuing to invest in companies that increased their polluting emissions (Baril, 2024) [4]. On the social level, some global car manufacturers, including General Motors, Tesla, Toyota, and Volkswagen, reportedly failed to meet their public commitment to reduce the use of Uyghur forced labor in their aluminum supply chains, as reported by the Human Rights Watch (2024) [5].

The alignment (or lack thereof) between a firm’s proclaimed ESG policies and their actual internal ESG practices is critical to the quality of the information provided to investors and other stakeholders for their evaluation of firm’s sustainable practices and respective performance. Indeed, more and more investors, especially institutional investors, are integrating ESG criteria into their investment decisions, leading to an increasing demand for such information (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018; Yucheng, Weijun, Zhao, & Zecheng, 2023) [6,7]. This information allows them to identify non-financial risks to which companies are exposed, triggering their engagement with invested firms to change practices, mitigate these risks, and protect their long-term investments (Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, & Yang, 2011) [8]. The potential gap between ESG policies and practices can also be linked and may take the form of ‘greenwashing’ or ‘brownwashing’. While greenwashing (or socialwashing) would consist of a company publicly embellishing its ESG intentions or policies relative to the practices it implements, ‘brownwashing’ is defined as the minimization that occurs during communication of actual ESG achievements (Kim & Lyon, 2015; Lyon & Montgomery, 2015) [9,10]. This misalignment can therefore bias investors’ and other stakeholders’ assessment of a firm’s ability to manage ESG issues.

Given the growing importance of ESG information in investment practices, and assuming that ESG policy–practice decoupling may be a strategic or an unintentional response to competing expectations from multiple stakeholders, it is crucial to develop frameworks that measure and assess the extent of ESG decoupling. In this article, we aim to address this issue. As such, we first reviewed the relevant literature to conceptualize ESG policy–practice decoupling, understand its implications for the usefulness of ESG information, and identify ways to observe the extent to which firms decouple ESG policies from practices. We then proposed a framework to measure ESG policy–practice decoupling. To validate our measurement framework, we relied on the ASSET4 ESG Ratings database from Thomson Reuters (Thomson Reuters EIKON, 2018) [11]. We then conducted content analysis and classification of the ASSET4’s ESG 633 data entries to identify the data points that capture internally focused actions and data points that measure externally focused actions for the three ESG dimensions. After applying several criteria to refine and categorize these data entries, we retained 151 data points representing internal and external actions across environmental, social, and governance dimensions; precisely, 22 data points representing internal actions and 19 data points representing external actions for the environmental dimension (E), 31 data points representing internal actions and 19 data points representing external actions for the social dimension (S), and 47 data points representing internal actions and 13 data points representing external actions for the governance dimension (G). To validate our framework to measure ESG policy–practice decoupling and assess the extent of this phenomenon, we collected ASSET4 data and calculated a decoupling index for the environmental and social dimensions using a sample of 1323 firms’ constituents of the S&P 1500 index, covering a period of seven years (2016 to 2022).

The proposed measure addresses a gap in the literature by providing a theoretically driven, quantitative framework to assess the alignment (or lack thereof) between the firms’ ESG policies and actual practices. By empirically validating this measure with ASSET4 data points, we reveal the extent and persistence of ESG policy–practice decoupling. Our framework provides important implications, offering a means to identify and assess this issue. For investors, it facilitates more informed decisions (Schiehll & Kolahgar, 2021) [12], helping to identify firms with genuine ESG commitments and encouraging positive corporate behavior. For firms, closing the gap between policy and practice can enhance ESG reporting, thereby protecting their reputation and financial standing in an increasingly sustainability-focused market. Policymakers can use our measures to strengthen regulations that promote meaningful ESG implementation, while also encouraging greater accountability across industries.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: We begin with a review of the relevant literature, providing the motivation and theoretical foundations for our proposed measurement framework. Next, we describe the framework for ESG policy–practice decoupling, outlining its development step by step. This is followed by an empirical validation of our measures where we employed the ASSET4 dataset to calculate the proposed decoupling index for the environmental and social dimensions of a sample of 1323 U.S. firms. In the final section, we discuss the practical implications of our findings and propose several directions for future research, highlighting opportunities to extend this line of inquiry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Why Do Firms Decouple ESG Policies from Practices?

The pressure to behave in accordance with the normative beliefs of key stakeholders has long been acknowledged as a prerequisite for firms to obtain stability, legitimacy, and access to strategic resources (Oliver, 1991) [13]. While a firm’s exposure to compatible demands from multiple stakeholders remains unproblematic, exposure to competing, and sometimes conflicting, demands seems more challenging for individuals and organizations (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Lounsbury, & Micelotta, 2011) [14]. Pache and Santos (2010: 457) [15] emphasize that “organizations operate within multiple institutional spheres and are subject to multiple and contradictory regulatory regimes, normative orders, and/or cultural logics”. Further, as socially responsible investing (SRI) has gained popularity globally, the investors’ information needs and the firms’ disclosure practices have shifted from shareholder value creation to stakeholder orientation (Marquis, Toffel & Zhou, 2016; Schiehll & Kolahgar, 2024) [16,17]. With this shift in the mindset of the investors, informed investment decisions need accurate and credible ESG information on a firm’s sustainable policies and actual practices. Although ESG reporting is aimed at reducing information asymmetry between a firm and its external stakeholders, it can be used for the deceitful purpose of creating organizational façades or signaling purposes (Tashman, Marano & Kostova, 2019) [3].

The previous research investigating decoupling provides evidence that firms tend to publicize the adoption of prescribed governance mechanisms but symbolically implement them, and yet, they obtain legitimacy from the actors sponsoring such demands (Westphal & Zajac, 1998) [18]. Along this line, Marquis, Toffel and Zhou (2016) [16] provide evidence that under increased stakeholders pressures to report environmental impacts, firms tend to practice selective environmental disclosure. Along the same line, Testa, Boiral and Iraldo (2018) [19] examined firms’ proactive integration of environmental practices in response to institutional pressures and show that when demands are endorsed by different stakeholders (i.e., suppliers, customers, shareholders, and industrial associations), firms adopt such practices symbolically. Although insightful, these studies do not directly measure, document cross-sectionally, or fully capture the actual gap between implemented practices (internal actions) and proclaimed policies (external actions).

In today’s landscape, firms are increasingly required to improve and communicate their performance on ESG factors. This trend is driven by changes in societal expectations about a firm’s purpose and the growing awareness of environmental challenges and climate change from all stakeholders. Among these stakeholders, investors play a crucial role as primary constituent of the firm because they can be deeply impacted by these risks and because their ownership position allows them to engage with management through formal mechanisms to address these risks. As a result, institutional investors now integrate ESG criteria into their decisions as it enables them to identify and understand the non-financial risks companies face and take measures to mitigate or diversify these risks to protect the value of their investments (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018; Schiehll & Kolahgar, 2024) [6,17]. This evolution in investment practices has generated an increasing demand from investors for reliable information on ESG initiatives (Yucheng, Weijun, Zhao, & Zecheng, 2023) [7]. From the supply side, the incentives for firms to provide information about how ESG risks and opportunities are managed relies on the principle that lower information asymmetry impacts reputation, reduces the cost of capital (Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, & Yang, 2011) [8], and improves investment efficiency (Duong, Wu, Schiehll, & Yao, 2024) [20].

Building on the above, we argue that it is crucial to assess whether companies’ public and external commitments regarding their ESG risks and opportunities are supported by the effective implementation of practices.

2.2. Internal and External ESG Actions

Scholars suggest that firms implement two distinct forms of ESG actions to meet the demands of their multiple stakeholders, and decoupling occurs when ESG internal practices do not align with the image or external communication efforts regarding its ESG policies (Tashman, Marano & Kostova, 2019; Sauerwald & Su, 2019) [3,21]. In other words, the symbolic management of ESG issues can lead to externally focused ESG actions that are decoupled from internal ESG actions.

Along this line, the literature suggests that policies refer to formal guidelines, principles, or frameworks that firms communicate or claim to guide their actions and decisions. In the context of ESG, by publicly stating their policies, firms acknowledge and define their responsibility to specific ESG issues (Skjaerseth & Wettestad, 2009) [22]. Thus, policies are communication initiatives undertaken towards external stakeholders, which we will refer to as external actions. On the other hand, practices refer to internal actions and controls implemented internally to operationalize the established and/or communicated policies aimed at managing ESG risks and opportunities, commonly referred to as internal actions. Moreover, internal ESG actions often require significant changes to essential operating practices, standards, structures, and routines, or even long-term capital investments to adapt processes and the organizational culture. In contrast, external ESG actions are more frequently part of short- and medium-term efforts to establish trust between the company and its external environment (Eccles, Ioannou & Serafeim, 2014) [23]. This distinction highlights that ESG policy–practice decoupling can be a deliberate decision or an unintended consequence of multiple and competing stakeholders’ expectations.

Policy–practice decoupling suggests a disconnect or gap between what the policies dictate and how these policies are implemented in practice. This could indicate scenarios where organizations fail to effectively translate their policies into meaningful actions or where their practices diverge from the stated policies, possibly due to various factors such as organizational culture, resource constraints, or other operational challenges. Although ESG decoupling may allow companies to appear better to their stakeholders in the short term, in the long term, they could be penalized by a decline in the value of their shares (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016) [2]. This highlights the importance of a balanced approach, recognizing both the communication and the implementation of practices and processes in managing stakeholder interests. This conceptualization guides the framework we propose in the next section

2.3. Measuring ESG Policy–Practice Decoupling

To provide investors with information to assess a firm’s ESG risks and opportunities, independent rating agencies such as Kinder–Lydenberg–Domini (KLD), Thomson Reuters’ ASSET4, Vigeo, and Sustainalytics developed comprehensive methods to assess a firm’s ESG performance. The resulting scores and respective ratings reflect an aggregated measure that combines firms’ exposure to ESG risks and the initiatives taken by the firm to manage and minimize those risks (Madison & Schiehll, 2021) [24]. ESG scores, therefore, combine quantitative and qualitative criteria aimed to assess inputs, outcomes, controversies, and compliance with certain regulations. The resulting aggregate score therefore serves as an indicator of how well a company manages ESG risks and opportunities. In our study, we rely on individual data points from ASSET4 ESG scores because, in comparison with other rating systems, ASSET4 methodology more explicitly distinguishes between efforts related to external communication or disclosure, implemented practices, and resulting outcomes.

As discussed above, we take the perspective that firms perform two distinct types of ESG actions to meet the demands of their multiple stakeholders, and decoupling occurs when firms publicly commit to sustainable practices and policies (external ESG actions) but fail to implement them effectively in their operations (internal ESG actions) (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016) [2]. Building on this perspective, we propose a framework to measure the alignment (or lack thereof) between a focal firm external and internal ESG actions, relying on the ASSET4 ESG database, which comprises 633 data entries aimed at assessing and rating firms’ overall ESG performance. ASSET4’s assessment is reflected in an aggregated ESG score derived from the scores of the three ESG dimensions and their respective categories (Thomson Reuters EIKON, 2018) [11]. More specifically, the categories of the environmental dimension are emissions, innovation, and resource use. The categories for the social dimension are workforce, community, human rights, and product responsibility. Finally, the categories for the governance dimension are management, shareholders, and CSR strategy (Thomson Reuters EIKON, 2018) [11]. Within these 10 categories, ASSET4’s reference guide outlines 633 data points employed to evaluate the ESG performance of a focal firm.

Our measurement framework builds on and extends the framework used by Hawn and Ioannou (2016) [2] to classify information into internal and external ESG actions. However, an important adaptation of Hawn and Ioannou’s (2016) [2] approach is necessary for two main reasons. First, these authors developed their study based on the 2014 version of the ASSET4 reference guide. Second, they used a broad measure that did not distinguish between actions undertaken to address issues within the specific ESG dimensions. Thus, our starting point is a more updated version of the ASSET4 reference guide, the one reflecting ASSET4’s methodology in 2016. Additionally, as discussed earlier, we propose a measure to assess decoupling between practices and policies for each of the ESG dimensions.

3. Framework Development: Concepts, Rationale, and Steps

3.1. Building on and Extending Hawn and Ioannou’s (2016) Framework

The ASSET4 methodology has significantly evolved since the 2014 version used by Hawn and Ioannou (2016) [2]. Indeed, in the 2016 version, the starting point for our proposed framework, there are 633 data entries, compared to the 900 that existed in the 2014 version. Our comparison suggests that the difference is primarily due to two factors: (1) the evolution of ESG issues and practices; and (2) the grouping of certain individual data points to avoid redundancy in measuring ESG practices. For example, the data point «SOEQDP025: Does the company claim to provide its employees with a pension fund, health care, or other insurance?», no longer exists as it has been integrated into the usual human resource management practices of companies.

Other differences are explained by the fact that some data points are more elaborate and precise in 2016. For example, in 2014, for the emissions reduction policy in the environmental dimension, the data element «ENERDP0011: Does the company have a policy to reduce emissions?» was replaced by «ENERDP0051: Does the company have a policy to improve emission reduction? The scope includes various forms of emissions to land, air, or water from the company’s core activities. Processes, mechanisms, or programs in place as to what the company is doing to reduce emissions in its operations. System or a set of formal documented processes for controlling emissions and driving continuous improvement».

In the social dimension, for example, there was a data point in 2014, «SODODP0012: Does the company have a work–life balance policy? And does the company have a diversity and equal opportunity policy?», which was broken down into several distinct elements, including «SODODP026: Does the company claim to provide flexible working hours or working hours that promote a work–life balance? (Programs or processes that help employees have a balance between their work and personal life. Includes flexible work arrangements such as telecommuting, flexible working hours, job-share, and reduced and compressed workweeks)» and «SODODP0081: Does the company have a policy to drive diversity and equal opportunity? (Program or practice to promote diversity and equal opportunities within the workforce. Includes information on the promotion of women, minorities, disabled employees, or employment from any age, ethnicity, race, nationality, and religion—consider information from the code of conduct mentioning diversity policy together with the reporting of violations)».

It is also worth noting that an updated set of data points were created to reflect ESG issues that were not considered in the 2014 framework, as used by Hawn and Ioannou (2016) [2]. In the social dimension, for example, practices related to employee welfare are captured, among others, by data points such as «SOPRDP087: Does the company claim to provide flexible working hours or working hours that promote a work–life balance? (Programs or processes that help employees have a balance between their work and personal life. Includes flexible work arrangements such as telecommuting, flexible working hours, job-share, and reduced and compressed workweeks)».

Similarly, in the environmental dimension, a new metric was included to capture the focal firm impact on biodiversity: «ENERDP019: Does the company report on its impact on biodiversity or on activities to reduce its impact on native ecosystems and species as well as the biodiversity of protected and sensitive areas?». Another example, within the governance dimension ASSET4 includes new data points to capture whether firms integrate ESG performance into executive incentive compensation, for example, «CGCPDP0013: Does the company have an extra-financial performance-oriented compensation policy? (The compensation policy includes remuneration for the CEO, executive directors, non-board executives, and other management bodies based on ESG or sustainability factors)».

It is also worth noting that Hawn and Ioannou’s (2016) [2] approach to measuring decoupling did not start with the full set of 900 data points included in the ASSET4’s methodology in 2014. Instead, they selected a smaller subset of 120 data points, which they identified as the most strategic, referred to as the “Strategic Framework”. From these 120 data points, they classified only 21 as internal ESG actions and only 24 as external ESG actions (Hawn and Ioannou, 2016) [2]. Further, these authors did not differentiate between actions across the three ESG dimensions. Our approach, in contrast, is more comprehensive and conservative. We start with the entire set of 633 data points presently used in the ASSET4’s ESG score methodology. Additionally, we propose measuring decoupling across the three ESG dimensions separately.

3.2. Classifying ASSET4 Data Points into Internal and External ESG Actions

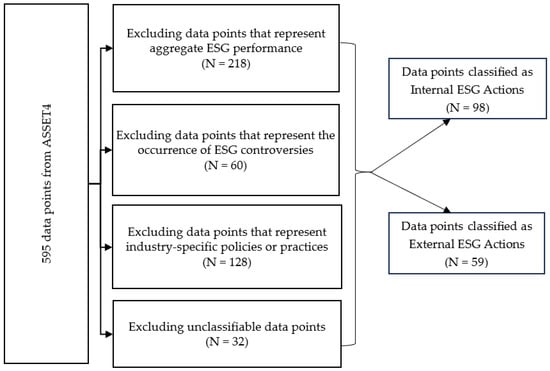

As discussed above, our starting point is the ASSET4’s 2016 reference guide, which classifies 633 data points into the three ESG dimensions. Our initial content analysis of these data points, within each dimension allowed us to identify 21 data points (across all three dimensions) that represent an aggregate score or rating outcome, derived from other raw data points. Three examples are: TRESGSESG, which is an aggregated overall company score based only on the self-reported information in the environmental, social and corporate governance pillars; TRESGCSESG, an overall company score based on the reported information in the environmental, social, and corporate governance pillars (ESG Score) with an ESG Controversies overlay; and ENSCORE, the Environment Pillar Score, which is the weighted average relative rating of a company based on the reported environmental information and the resulting three environmental category scores, and 17 data points indicating whether the company adheres (or not) to the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSD). These 38 data points were therefore excluded from our framework as they do not represent internal or external actions. Our starting point is the 595 data elements distributed among the three dimensions as follows: 180 data points related to the environmental dimension (E), 280 data points related to the social dimension (S), and 135 data points related to the governance dimension (G). In the next paragraphs, we describe step by step the content analysis criteria used to classify the 595 data points into internal and external ESG actions:

3.2.1. Step 1—Identifying Data Points That Represent Quantitative ESG Performance Measures

Given that our aim is to analyze the gap between ESG actions implemented and those aimed at external communication, this step is justified by the fact that we need to exclude data points representing outcomes. In other words, data points that are a result of combining other data entries do not represent internal or external ESG actions as defined above. A performance outcome reflects the result or impact of one or more actions and, as such, cannot be considered an action. Thus, a content analysis was conducted individually within each ESG dimension using the following keywords: “Total of”, “total amount”, “number”, “rate”, “percentage”, “hours”. These data points were classified as ESG performance indicators and consequently excluded from our framework. The number of performance measures identified is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Breakdown of ASSET4 data points by categories and ESG dimensions.

3.2.2. Step 2—Identifying Data Metrics Representing ESG Controversies

According to the ASSET4 methodology, an ESG controversy refers to a specific event that may lead to a significant negative reaction from stakeholders due to its implications (Thomson Reuters Eikon, 2018) [11]. These events can include violations of environmental standards, forced labor scandals, corruption cases, or other incidents that harm the focal firm’s reputation but also reflect its performance regarding how it is managing stakeholders’ interests. Similarly to other ESG rating agencies, the Thomson Reuters ESG scores assess the severity and frequency of these events, as well as how companies respond to them, to provide an overall evaluation of the ESG risk associated with a given company. Despite their importance in the process of measuring firms’ ESG performance, controversies often arise when companies face external criticism of the media related to their sustainability practices, labor conditions, or corporate governance. These events are viewed as reactions from stakeholders, including consumers, activists, and investors, who challenge a company’s practices. As such, controversies are considered as neither external nor internal ESG actions and will not be included in the set of data points we retain for our proposed measure of ESG policy–practice decoupling. The number of data points related to ESG controversies is presented in Table 1.

3.2.3. Step 3—Identifying Data Metrics That Are Industry-Specific

We aim to identify actions that are common or applicable in a general way to all types of companies, regardless of their industry. This choice was made so that the data points we retain to measure the gap between policies and practices do not create a sectoral bias. By doing so, we exclude pre-established industry specific differences in the set of data points and ensure the cross-sector comparability of our proposed measure of ESG decoupling. To illustrate, we would not have been able to properly assess the decoupling of a company in the pharmaceutical industry with the tobacco industry, as they have specific and different ESG criteria and data points. Thus, we have decided to identify and not include in our framework data points listed by ASSET4’s reference guide that are specific to an industry (e.g., weapons, mining, tobacco, pharmaceuticals, etc.). We retain in our measurement framework only the data items representing internal and external ESG actions that are applicable across industries. The number of industry-specific data points excluded is presented in Table 1.

3.2.4. Step 4—Identifying Data Metrics Representing Internal Actions

As previously indicated, internal actions must represent initiatives under the control of the company and result from the adoption and/or implementation of operational practices, changes, or standards aimed at improving the company’s environmental or social performance. For example, practices implemented to improve working conditions, employee safety and recruitment, the use of renewable energy, or waste management. These actions are identified by the implementation or adoption of “initiatives”, “practices”, or “tools” related to the three ESG dimensions. The number of data points representing internal ESG actions, as defined earlier in our methods and according to our content analysis criteria, is presented in Table 1.

3.2.5. Step 5—Identifying Data Metrics Representing External Actions

In contrast, external ESG actions are defined as initiatives by the company aimed at claiming the adoption of policies or transmitting information to external stakeholders to seek external endorsement of their sustainable practices. These external actions are therefore linked to keywords such as “publish”, “announce”, “declare”, “describe”, “report”, “claim”, and “disclose”. Content analysis based on the descriptions of the data points presented in ASSET4’s reference guide allowed us to identify the external nature of these actions. In a second step, each data point was further analyzed to ensure that it is truly a voluntary action aimed at communicating ESG elements to external stakeholders. The number of data points representing external ESG actions is presented in Table 1.

3.2.6. Step 6—Identifying Other Data Points

Having excluded the data elements representing aggregated ESG scores, adherence to UNSD, performance measures, controversies, and industry-specific information, we identified certain data points that we could neither classify as internal actions nor classify as external actions objectively, as they do not meet the predefined criteria, for example, «ENERDP089: Is the company aware that climate change can represent commercial risks and/or opportunities?—development of new products/services to overcome the threats of climate change to the existing business model of the company—some companies take climate change as a business opportunity and develop new products/services» or «SOEQDP037: Has there been a strike or an industrial dispute that led to lost working days?».

In sum, the data points classified in the ‘other’ category generally reflect situations where awareness or acknowledgment does not translate into actionable practice. More precisely, in the first example, a company being aware of a particular state of affairs does not represent an actionable ESG practice or an externally focused effort to communicate with stakeholders. This awareness is more of a recognition rather than a proactive communication strategy. In the second example, the occurrence of strike days is not indicative of an internal structural action or a voluntary disclosure of social data. Instead, it simply reflects a situation that may affect a firm without implying any deliberate effort to communicate or manage external relations.

Figure 1 presents a flow chart that summarizes the steps described above. Table 1 presents the number of items in each category resulting from our classification of the 595 data points from ASSET4’s reference guide, which was our starting point to operationalize a measure of ESG policy–practice decoupling. Our data collection, therefore, will focus on 98 internal ESG actions and 59 external ESG actions. The data collection aims to: (1) assess the coverage and availability of data to determine the presence or absence of these actions within each firm in the sample; (2) measure the level of internal and external ESG actions for each firm during the analysis period (2016 to 2022); and (3) calculate a decoupling index to reflect the gap between the levels of internal and external ESG actions undertaken by each firm. By collecting and analyzing these data, we aim to gain insights into the ESG practices of the firms in our sample and validate our proposed framework for measuring ESG policy–practice decoupling.

Figure 1.

Steps in the classification process.

4. Empirical Validation of the Proposed ESG Decoupling Index Using ASSET4

4.1. Sample

We drew our sample from firms listed in the S&P 1500 index, which covers approximately 90% of the market capitalization of U.S. stocks. It is therefore a representative index that is closely followed by a significant number of investors. We began the sampling process by identifying all firms included at least once in the S&P 1500 index during the period covered by our analysis (2016 to 2022). The next step was to identify their inclusion in the ASSET4 ESG dataset and the availability of the selected data items (see Table 1) described above. The result is a target sample of 1506 companies. Due to missing data in the ASSET4 dataset, we had to exclude 183 firms from our target sample. The final sample therefore consists of 1323 firms for the period from 2016 to 2022. Table 2 summarizes the steps of our sampling process.

Table 2.

Sample description.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

After collecting and analyzing the ASSET4 individual data points we retained in our proposed framework to measure ESG policy–practice decoupling, we decided to focus our empirical analysis on the environmental (E) and social (S) dimensions. This choice is based on our observation that the data points for the governance (G) dimension show relatively limited variance between the sample firms. We attribute this finding to the more established and regulated nature of corporate governance practices, often framed by standards and guidelines imposed by stock exchanges and other corporate governance regulatory bodies (Westphal & Zajac, 1998; Satta, Parola, Profumo & Penco, 2007) [18,25]. As a result, firms have much less discretion regarding governance related practices and respective communication, compared to social and environmental related issues. We, therefore, focus our analysis on the dimensions where there is a higher level of management discretion for potential policy–practice decoupling between implemented practices and communicated policies.

In Table 3 and Table 4 below, we present the number of observations available per individual data point, reflecting internal and external actions related to the environmental and the social dimensions, respectively. Each individual data item is identified by its ASSET4 code, its environmental issue category, and the classification into internal (I) or external (E) actions, resulting from the framework we proposed in the previous section. The “Present” column (value = 1) refers to the application or implementation of the internal or external action by the focal firm, while the “Absent” column (value = 0) represents the number of observations where there is an absence or a lack of implementation of the respective internal or external actions by the focal firm. Finally, the “Missing” column presents the data that has not been collected in the ASSET4 dataset for the respective action.

Table 3.

Firm-year observations by data point—environmental dimension (2016–2022).

Table 4.

Firm-year observations by data point for the social dimension (2016–2022).

In our subsequent analysis, which aims to calculate and validate our measure, we use only individual data points, or actions, with a percentage of “Missing” values below 50%. As a result, four data items reflecting external actions and one data item reflecting an internal action related to the environmental dimension were excluded from our calculations. These data items are identified in gray in Table 3, below. Our calculations, therefore, proceed with 19 internal actions and 22 external actions for measuring decoupling within the environmental dimension. For the social dimension, the data items with more than 50% of missing data are identified in gray in Table 4. Therefore, the calculations for policy–practice decoupling within the social dimension will include 31 metrics of internal actions and 19 metrics of external actions.

Table 5, panels A and B, present the temporal distribution of our observations by individual data item for the environmental dimension, while Table 6, panels A and B, present the temporal distribution for the individual data items used to measure decoupling within the social dimension.

Table 5.

Distribution by data point and by year—environmental dimension. Panel (A): Firm-year observations for internal actions in the environmental dimension. Panel (B): Firm-year observations for external actions—environmental dimension.

Table 6.

Distribution by data point and year—social dimension. Panel (A): Firm-year observations for internal actions—social dimension. Panel (B): Firm-year observations for external actions—social dimension.

The data presented in the tables above reveals a dynamic over time as well as a pronounced variation between the types of actions, named internal and external E&S actions in our measurement framework. More important, the temporal distribution of our observations clearly shows significant variations within issue categories, indicating that certain issues, either in the environmental or the social dimension, receive comparatively more attention than others. This highlights the shifts in the intensity and focus of efforts that firms allocate to the same type of action or within action categories over multiple years. It shows that firms change the effort dedicated to different dimensions or categories over time, within both the social and environmental dimensions, suggesting that decoupling is dynamic and may be driven by firm specific or contextual factors. The documented variation also reflects a notable evolution in the number and type of actions implemented over time, probably in response to the changing expectations of stakeholders throughout the period covered by the data. Together, the data corroborate the importance of measuring and assessing policy–practice decoupling, understanding its implications, and demonstrate the feasibility of our proposed approach to measuring ESG decoupling. In the following section, we present the results from our calculations.

5. Calculating the Decoupling Index

In this section, we calculate the proposed decoupling index to validate our measurement framework and observe whether firms decouple E&S practices from policies and the extent to which they do so. It is worth noting that a more detailed description of what is measured by each individual data point included in the set of internal and external actions can be found at the Thomson Reuters EIKON’s (2018) [11] reference guide. Let us also recall that, similar to Hawn and Ioannou (2016) [2] and Bothello, Ioannou, Porumb and Zengin-Karaibrahimoglu (2023) [26], the alignment (or lack thereof) between internal and external E&S actions is assessed by a composite index resulting from the aggregation of a set of dichotomous data items reflecting whether the focal firm applies the specific action. Individual data items with the value 1 represents the presence, and 0 when the focal firm does not apply the respective action. For more details, please see Table 5 and Table 6 above.

As explained above, we retained 22 data points as external actions and 19 as internal actions within the environmental dimension, while 19 data points were classified as external actions and 31 as internal actions within the social dimension. We then calculated Cronbach’s alpha statistics for each type of action to assess whether the items measure the same underlying construct. Given the binary nature of our data, we calculated Cronbach’s alphas using the Kuder–Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20), which is specifically designed for dichotomous variables (George & Mallery, 2003) [27]. Furthermore, because our dataset spans 7 years (2016–2022), we first calculated Cronbach’s alpha for each year to evaluate potential differences in reliability over time. The results indicated that the relationships among the items and the internal consistency were stable across years. Based on this stability, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha for the pooled data across all years. Using the pooled data, we obtained Cronbach’s alphas of 0.841 for the external actions index and 0.891 for the internal actions index within the environmental dimension. Within the social dimension, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.759 for the external actions index and 0.892 for the internal actions index. In both cases, Cronbach’s alpha statistics indicate very good internal consistency and reliability of the measures (George & Mallery, 2003) [27].

As shown in Table 1, in our proposed framework, the theoretical maximum number of internal actions is different from the theoretical maximum number of external actions, both for the environmental and the social dimensions. As described in the methods section, this discrepancy arises because of the different number of underlying data points for each type of action (i.e., internal and external). As such, it would be inappropriate to directly compare the nominal gap between, for example, 22 external environmental actions and 19 internal environmental actions. To account for these variations and ensure comparability, we normalize the actual number of internal and external actions implemented by the focal firm against the maximum theoretical number of internal or external actions applicable, according to our framework. The final composite decoupling index, which aims to reflect the difference between a focal firm’s specific efforts on external and internal actions undertaken in a specific year, is then computed as the difference between the normalized values of internal and external actions. This allows for a consistent and fair comparison despite the differing number of data items in each type of action. Thus, the components of our decoupling index are as follows:

and

where

T_ExtAct_Dimension_Norm(i,t) is the normalized sum of external actions implemented in a dimension (environmental or social) by a firm i for the year t.

T_IntAct_Dimension_Norm(i,t) is the normalized sum of internal actions implemented in a dimension (environmental or social) by a firm i for the year t.

N indicates the theoretical maximum number of external or internal actions in each dimension.

indicates the sum over actions within a dimension from n = 1 to n = N, of external or internal actions implemented by firm i for the year t, in one of the analyzed dimensions (E or S).

ExtAct_Dimension(n,i,t) represents the value assigned to data points reflecting external action n implemented by firm i for the year t, in the analyzed dimension. The value is 1 if the action was implemented (Present) and 0 if the action was not observed (Absent).

IntAct_Dimension(n,i,t) represents the value assigned to data points reflecting internal action n implemented by firm i for the year t in the analyzed dimension. The value is 1 if the action was implemented (Present) and 0 if the action was not observed (Absent).

To Illustrate, for the environmental dimension, a given firm W might implement, according to ASSET4 dataset, 11 external actions and 5 internal actions. We would thus have 11 external actions applied out of 22 possible (theoretical) external actions, multiplied by 10, and 5 internal actions applied out of 19 possible internal actions, multiplied by 10. The purpose of multiplying by 10 is to present the index on a scale from 0 to 10.

5.1. Decoupling Index: Environmental Dimension

As explained above, to account for the difference between the maximum number of internal and external actions and ensure comparability, we first normalize the index values for each type of action before calculating the difference between external and internal actions. Hence, the decoupling index for the environmental dimension can be represented by the following equation, which can take values between −10 and +10:

Table 7 above presents the descriptive statistics of the decoupling index calculated for the environmental dimension in our sample by year (2016 to 2022), using the proposed framework. When analyzing these results, several key insights emerge.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the decoupling index—environmental dimension.

When comparing the maximum and minimum values across the years, we observe that the maximum values decrease with a peak at 3.80 in 2016 and reaching a level of 2.44 in 2022, while minimum values increase from −5.69 in 2016 to −6.53 in 2021. It is worth recalling that positive values in our decoupling index reflect greater efforts on external actions relative to internal actions within the same dimension. Conversely, negative values reflect the opposite, greater levels of internal actions than external action. This evidence suggests that, on average, over time, firms shifted from symbolic management of environmental performance to more substantial internal changes, which were not necessarily the focus of external communication efforts. Our data also shows that, on average, our sample firms switched from greenwashing or socialwashing to brownwashing, suggesting that, along our period of analysis, an increasing number of firms dedicated less effort to communicate externally the environmentally related actions they implement internally. This is somewhat also corroborated by the sample mean values, which are predominantly negative during the years of analysis, ranging from −0.74 in 2016 to −1.42 in 2021. Similarly, the median goes from 0 in 2016 to a negative value of −0.81 in 2022, suggesting a rising trend in brownwashing over time. Finally, the standard deviation of our decoupling index remains relatively stable around 1.4, with a slight increase from 1.29 in 2016 to 1.44 in 2020, before stabilizing around 1.41 in the latter years. Our data show that the dispersion of our environmental decoupling index among the firms in our sample is quite constant, suggesting that there is persistence in the decoupling behavior along the years of analysis.

In summary, the results documented in Table 7 suggest that decoupling between external and internal actions related to the management of environmental issues is significant both in magnitude and in its persistence over time. This highlights the importance of proposing objective measures of decoupling and the need for a systematic approach to improve the alignment of environmental policies and practices within firms. Given the trends revealed by our data, we further examine the temporal distribution of our observations by type of decoupling. We therefore classified sample firms into the following three (3) subgroups:

- We classified the group of firms with a decoupling index = 0 as ‘neutral’. As such, this category includes the firms that show, according to our measure, a balance between internal and external actions, or that did not implement any data metrics constituting internal and external actions for a given year.

- We classified the group of firms with a decoupling index < 0 as ‘brownwashing’. This category therefore includes the firms for which the level of internal action is greater than their external action within the same dimension.

- Finally, we classified the group of firms presenting a decoupling index > 0 in the environmental or social dimension, respectively, as ‘greenwashing’ or ‘socialwashing’. This category comprises the sample firms for which the level of effort on external actions exceeds the effort on internal actions.

As shown in Table 8, about 12% of firms in our sample engage in ‘greenwashing’, while about 75% of firms engage in ‘brownwashing’. Thus, according to our framework and data collected from ASSET4, most firms in our sample implement more internal actions relative to the efforts dedicated to external actions. Moreover, the distribution across the three subgroups is dynamic over time. We can observe that in the years 2016 to 2017, a great proportion of firms belong to the ‘neutral’ category; these firms either present no decoupling or simply had not implemented internal and external actions as coded by ASSET4. From 2018 onward, this proportion declines. We cannot rule out the possibility that this trend is influenced by improvements in ASSET4’s coverage and data collected, as explained in our methodology section. Worth noting, however, is that the proportion of firms engaged in ‘greenwashing’ has remained constant throughout the period, while the proportion of firms engaging in ‘brownwashing’ increased by 61% from 2016 to 2021. In short, our results suggest that, on average, more than 70% of firms in our sample engage in some type of decoupling in the environmental dimension during the period of our analysis. These results underscore the pervasiveness of this phenomenon, suggesting that it is an important area for further research.

Table 8.

Distribution across different types of decoupling—environmental dimension.

5.2. Decoupling Index: Social Dimension

As previously described, our proposed measure of policy practice decoupling for the social dimension comprises 31 individual data points reflecting internal actions and 19 individual data points reflecting external actions. Thus, the decoupling index for the social dimension can be represented by the following equation:

The descriptive statistics for this index are presented in Table 9 below:

Table 9.

Descriptive statistics of the decoupling index—social dimension.

Similarly to the environmental dimension, Table 9 reveals that the maximum values of the decoupling index within the social dimension show a continuous decline, ranging from 3.77 in 2016 to 1.95 in 2021 and 2022. In contrast, the minimum values remain stable and negative, ranging from −4.26 in 2016 to −4.99 in 2021, before a slight improvement to −4.79 in 2022. These trends suggest that, on average, our sample firms exert greater effort on external actions than on actions they apply internally on the social front. Conversely, there are also firms whose external social-related actions are at a lower level when compared to actions they implement internally to mitigate social-related issues. Interesting is also the fact that when comparing the maximum values of the decoupling indices for the social dimension to that of the environmental dimension (Table 7), we observe that, for most of the seven years covered in our analysis, the difference between external and internal actions is relatively higher in the social dimension compared to the environmental dimension.

In Table 9, the mean values of the decoupling index are systematically negative throughout the period, increasing from −0.63 in 2016 to −1.62 in 2021, before decreasing to −1.33 in 2022. This confirms that, just like in the environmental dimension, there is a trend towards brownwashing in the decoupling related to management of social issues. Again, when comparing the mean and standard deviation of the social decoupling index, we observe that in the years 2016 and 2017, decoupling was, on average, low and approached perfect alignment. However, starting in 2018, the gap is wider, followed by a slight recovery or improvement in 2022. Specifically, in 2021, the mean value reached its lowest level (−1.62). Surprisingly, the standard deviation remains relatively stable around 1.1, suggesting moderate dispersion of the social decoupling index among our sample firms. We interpret these statistics as evidence of a certain consistency and persistence of decoupling in the social dimension.

In summary, the results show that decoupling in the management of social issues is important and persistent, with notable variations again among firms in the sample and along the years covered in our analysis. Just as with the environmental dimension, these results corroborate the relevance of measuring and studying this phenomenon. In the following paragraphs, we will analyze the distribution of firms among the three decoupling categories. As explained above, these categories were named the neutral, the brownwashing, and the socialwashing categories (Kim & Lyon, 2015) [9]. The distribution among these categories for the social dimension is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Distribution across different types of decoupling—social dimension.

We observe that very few firms in our sample present a balance or did not apply the ASSET4 data items we retained in our framework to measure internal and external actions related to social matters. More precisely, less than 5% of firms from 2017 to 2021 are classified as ‘neutral’, followed by an important increase to 19% in 2022. Additionally, we can observe an increasing trend in the frequency of ‘brownwashing’ from 2020 to 2021. Overall, more than 80% of sample firms in our sample, in each single year, are in a situation of misalignment between internal and external actions related to the management of social issues, with most firms presenting a situation where, according to our index, efforts dedicated to internal actions are greater than the initiatives to endorse these actions externally. This trend can be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic created unprecedented challenges for businesses, and the economic and operational pressures they faced likely shifted their focus to enhance internal labor practices and employee welfare without respective external actions.

Table 10 also suggests that the proportion of firms engaging in ‘socialwashing’ within the social dimension decreased from 2016 to 2020, reaching stable levels in 2021 and 2022. This trend aligns with the various awareness campaigns on social issues such as equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), as well as the increased media coverage on social issues and heightened stakeholders’ expectations regarding firms’ social impact. In any case, our results suggest that most of the firms in our sample are in a situation of misalignment between the actions aimed at managing social issues, but the tendency appears to be that they have dedicated greater efforts to internal structural adjustments than to actions or communications aimed at external stakeholders.

6. Discussion

6.1. Recognizing and Measuring ESG Decoupling

In a society undergoing constant change, profit-driven firms are confronted with a growing array of conflicting external pressures, generating ambiguity and complexity in how to respond to stakeholders’ demands. Policy–practice decoupling, known as the gap between firms proclaimed policies and their actual implementation, can be viewed as firms’ strategic response to this complexity. Despite the potential appeal of ESG decoupling as a means to maintain legitimacy in the eyes of multiple stakeholders, without assuming full costs of responsible practices, a growing body of studies demonstrates how such behavior may negatively impact firms’ reputation and performance. Marquis, Toffel, and Zhou (2016) [16] demonstrate that intensified stakeholder pressure to report environmental impacts often leads firms to engage in selective environmental disclosure, revealing only favorable information while concealing poor performance. Similarly, Testa, Boiral, and Iraldo (2018) [19] find that in response to institutional pressures, firms may adopt symbolic compliance by showcasing environmental commitments that are not fully aligned with their actual practices. Extending this notion of decoupling, Michelon and Rodrigue (2015) [28] observe that firms targeted by socially oriented activism tend to increase their disclosure levels, even when the disclosed information was not explicitly demanded by shareholder proposals, further highlighting a strategic response to external pressures rather than substantive performance improvement. The previous research, however, has employed broad measures of ESG decoupling, without directly measuring or fully capturing the gap between implemented practices and proclaimed policies. We propose a theoretically driven framework for assessing ESG policy–practice decoupling and an empirical measure of ESG decoupling using data from ASSET4. Our approach offers a granular and quantitative measure, based on secondary data and a systematic comparison between the actions a focal firm undertakes to achieve structural changes (internal actions) and actions aimed at securing endorsement from external constituents (external actions). This framework allows for a better understanding of the extent and the nature of ESG decoupling across firms and different industries, providing both researchers and practitioners with a powerful tool to assess firms’ ESG performance more accurately. In the following paragraphs, we outline our contributions and highlight opportunities for future research.

6.2. Practical Implications

Investors often rely on corporate sustainability reports to evaluate firms’ ESG performance, but these reports can be misleading if firms overstate their commitment to responsible practices. Our proposed measure can help investors detect discrepancies between a firm’s proclaimed ESG policies and its actual practices, allowing for more informed investment decisions. A significant gap between ESG policies and practices may signal reputational risks, regulatory concerns, or operational inefficiencies, all of which could have downstream financial consequences. Investors can thus better assess a firm’s long-term performance by identifying the dimensions and sources of ESG decoupling. Investors can also use our decoupling index to identify firms to directly engage with (i.e., shareholder activism) and influence these firms to take substantial steps toward aligning their ESG policies with actual internal practices.

Policymakers can use our measure to identify areas for enforcing compliance with public policies or corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards. It could help to identify contexts or ESG issuess in which firms have more discretion to misrepresent their commitments, leading to stricter regulatory oversight. Further, by tracking this misrepresentation, policymakers can create incentives for firms to align their actions with their stated goals, contributing to better societal outcomes (e.g., environmental impact, labor practices). Finally, at the firm level, managers can leverage our measures to track and improve internal practices, ensuring that their firm’s values and actions are better aligned with public commitments.

6.3. Directions for Future Research

Our measurement framework, and respective validation from the ASSET4 data, also aims to encourage future empirical research on ESG policy–practice decoupling. Future research should seek to understand when and why some ESG policies remain symbolic while others become implemented. While we agree that competing expectations of stakeholders and investors create complexity for firms in deciding which actions to undertake, we show that not all ESG practices create the same level of ambiguity, nor do all firms respond with the same degree of decoupling. Thus, different combinations of source or type of stakeholder pressure, firm characteristics, and features of the policy being adopted may lead to similar degrees or persistence of ESG policy–practice decoupling. Such research will better inform investors and policymakers about the drivers of and contexts that encourage or deter ESG decoupling. Additionally, our measure holds potential for future qualitative and quantitative studies to explore the consequences and drivers of such misalignment. Another fruitful direction for future research would be to examine sustainability convergence across industries and time periods, investigating the mechanisms through which ESG policies, practices, and outcomes become aligned or maintain distinct trajectories. Perhaps there are different paths that explain similar levels of decoupling or recoupling.

Given the varying institutional pressures across countries, future research should examine how different regulatory, societal, and cultural contexts influence the level of ESG decoupling. For example, countries with stronger regulatory frameworks and sustainability standards may exert pressure on firms to avoid or reduce the potential misalignment between internal and external actions. Understanding how different types of institutional pressures (e.g., government regulations, industry norms, or societal expectations) interact with the ESG decoupling at the firm level can shed light on why firms in some countries are more prone at implementing substantial (as opposed to symbolic) ESG practices than others. Thus, important avenues for future research are to understand when sustainability policies remain symbolic and when they are genuinely implemented. What role do institutional pressures play in this behavior? Are firms that are more strongly influenced by regulatory or investor pressures more likely to take substantial ESG actions? Alternatively, do firms with strong internal governance mechanisms tend to overcome the gap and implement their environmental- and social-related policies more effectively?

While our approach proposes a quantitative measure of decoupling, we acknowledge that our framework does not account for the potential variability in the materiality of ESG issues across industries, which could be addressed by incorporating weight to issues within the same dimension. Future research could explore methodologies to account for industry-specific materiality while maintaining conceptual rigor. Future research could also benefit from incorporating qualitative insights to better understand the managerial-level factors behind the decoupling behavior. This includes investigating the motivations and perceptions of decision-makers within organizations. For instance, are managers under pressure to make symbolic ESG commitments to appease stakeholders’ pressure, or do they genuinely intend to implement those policies but face internal or external barriers? We also suggest future researchers to move beyond the drivers of decoupling and to try to understand what the consequences of circumstantial or persistent ESG decoupling are. We believe that one of the most pressing areas for future research is to examine whether capital markets penalize (or not) firms whose ESG commitments are seen as symbolic, and if so, what is the magnitude of this penalty? Conversely, do firms that close the ESG gap (i.e., recouple) or demonstrate genuine implementation outperform those that fail to do so? Researchers can also explore whether the market continues to reward firms that persist in ESG decoupling. Are firms that maintain a gap between their ESG claims and actual practices still able to secure long-term investments, or do investors gradually withdraw from such firms due to concerns over reputational risks and non-compliance?

6.4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the measures proposed in this study fill a gap in the existing literature by offering a quantitative, more granular, and theoretically driven framework to assess the alignment (or lack thereof) between a firm’s ESG policies and their actual implementation. By providing empirical validation with data from the ASSET4 for a sample of firms in the S&P1500, we also provide a picture of the extent and persistence of this phenomenon. We offer a first step to equip both researchers and practitioners with a measurement framework that allows us to identify and eventually exert influence to mitigate such behavior. As discussed above, our framework holds significant implications for various stakeholders—firms, investors, and policymakers. For investors, the proposed measure offers a more accurate means of identifying firms with genuine ESG commitments, enabling better-informed decisions and the promotion of positive corporate behavior. For firms, understanding and addressing this gap will not only enhance their ESG information but also protect their reputational and financial standing in an increasingly sustainability-conscious market. Policymakers can use our insights to strengthen regulations and frameworks that promote substantial implementation of ESG practices across industries. More broadly, our data also highlights the importance of more ESG accountability, urging firms to align their actions with their publicly stated goals. Our hope is that our framework spur further inquiries into the motives and the implications of ESG policy–practice decoupling, aiming to decode the complex dynamics at play between stakeholders’ expectations and firm’s actions.

Author Contributions

This article is a joint work of both authors. A.G.S.L. and E.S. contributed equally to the development of the research idea, the literature review, research methods, data collection, data analysis, and to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from ASSET4 environmental, social, and governance (ESG) data (now part of Refinitiv). https://www.refinitiv.com/en/sustainable-finance/asset4 (assessed on 10 September 2024) But restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license from HEC Montréal, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge valuable comments from participants of the research workshop at HEC Montréal and thank Mohamed Jabir for his assistance in data accessibility through the Laboratoire de calcul et d’exploitation des données (LACED) of HEC Montréal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Ioannou, I. Mind the gap: The interplay between external and internal actions in the case of corporate social responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashman, P.; Marano, V.; Kostova, T. Walking the walk or talking the talk? Corporate social responsibility decoupling in emerging market multinationals. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baril, H. (2024, 9 Janvier). Les Banques Canadiennes Accusées D’écoblanchiment, La Presse, Section Affaires. Available online: https://www.lapresse.ca/affaires/2024-01-09/plainte-deposee-a-l-amf/les-banques-canadiennes-accusees-d-ecoblanchiment.php (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Human Rights Watch 2024. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/fr/news/2024/02/01/chine-des-constructeurs-automobiles-impliques-dans-le-travail-force-douighours (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucheng, J.; Weijun, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zecheng, J. ESG disclosure and investor welfare under asymmetric information and imperfect competition. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Li, O.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Lyon, T.P. Greenwash vs. Brownwash: Exaggeration and Undue Modesty in Corporate Sustainability Disclosure. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson Reuters Eikon 2018, Thomson Reuters ESG Scores. Available online: https://www.thomsonreuters.com/content/dam/openweb/documents/pdf/tr-com-financial/methodology/corporate-responsibility-ratings.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Schiehll, E.; Kolahgar, S. Financial materiality in the informativeness of sustainability reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Raynard, M.; Kodeih, F.; Lounsbury, M.; Micelotta, E.-R. Institutional Complexity and Organizational Responses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 317–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiehll, E.; Kolahgar, S. Common ownership and investor-focused disclosure: Evidence from ESG financial materiality. In Strategy and the Environment; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.; Zajac, E. The Symbolic Management of Stockholders: Corporate Governance Reforms and Shareholder Reactions. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.K.; Wu, Y.; Schiehll, E.; Yao, H. Environmental and social disclosure, managerial entrenchment, and investment efficiency. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2024, 20, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwald, S.; Su, W. CEO overconfidence and CSR decoupling. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2019, 27, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjaerseth, J.; Wettestad, J. A framework for assessing the sustainability impact of CSR. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe: Rhetoric and Realities; Barth, R., Wolff, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, N.; Schiehll, E. The Effect of Financial Materiality on ESG Performance Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, G.; Parola, F.; Profumo, G.; Penco, L. Corporate governance and the quality of voluntary disclosure: Evidence from medium-sized listed firms. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2007, 12, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothello, J.; Ioannou, I.; Porumb, V.-A.; Zengin-Karaibrahimoglu, Y. CSR decoupling within business groups and the risk of perceived greenwashing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 3217–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Michelon, G.; Rodrigue, M. Demand for CSR: Insights from shareholder proposals. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2015, 35, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).