Abstract

The integration of the digital economy and higher education is a core driver of sustainable development, yet the mechanisms and heterogeneous effects of this interaction remain underexplored. Using balanced panel data from 30 Chinese provinces over 2011–2020, this study empirically investigates the impact of the digital economy on higher education development (scale, structure, quality) and its transmission channels. The digital economy development index (DEDI) is constructed via the entropy-weighted method, and a comprehensive empirical strategy is adopted, including baseline regression, instrumental variable (IV) estimation, difference-in-differences (DID), mediation analysis, and regional heterogeneity tests. The results reveal three key findings: (1) The digital economy exerts a significantly positive causal effect on higher education scale and structure optimization, with robustness confirmed by multiple tests. (2) It has no direct impact on higher education quality, but indirectly promotes quality through regional income levels, while institutional quality partially mediates the effect on structure. (3) Significant regional heterogeneity exists: the impact is strongest in eastern provinces, moderate in central provinces, and insignificant in western provinces, constrained by weak digital infrastructure. This study enriches the theoretical framework of digital economy–education interaction and provides actionable policy implications for promoting sustainable, balanced higher education development: strengthening digital infrastructure in underdeveloped regions, aligning educational structure with digital industrial demand, linking digital economic growth to educational investment, and implementing region-specific policies. These findings contribute to advancing the synergy between digital transformation and high-quality higher education, supporting long-term sustainable economic and social development.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Macroeconomic Shift: The Rise of China’s Digital Economy and Its Impacts

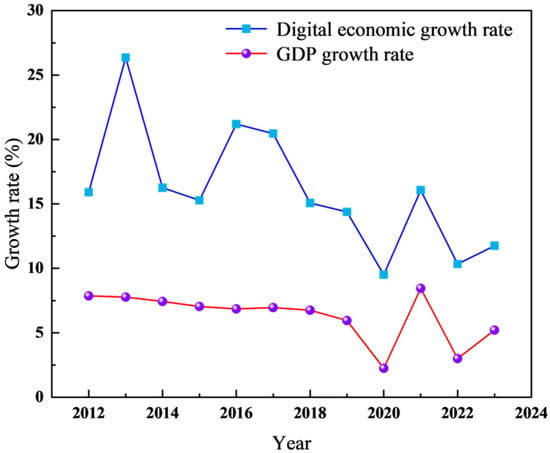

The global economy is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the pervasive integration of digital technologies [1]. This shift has given rise to the “digital economy”, an economic paradigm where digitized knowledge and information are key factors of production, modern information networks are vital carriers, and the effective use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) is the primary driver of productivity growth and economic optimization [2]. China has emerged as a pivotal player in this global trend. Empirical data underscores this momentum: for over a decade, China’s digital economy has grown at a rate consistently surpassing its GDP growth, solidifying its role as both a “stabilizer” and “accelerator” for the national economy (See Figure 1). This robust expansion, underpinned by the dual engines of digital industrialization (the core ICT sector) and industrial digitalization (the application of digital technologies in traditional industries [3]), is fundamentally reshaping production relations, resource allocation, and national growth drivers [4,5]. As this macroeconomic force matures, understanding its spillover effects beyond the commercial sphere—particularly into pivotal social sectors like higher education—has become an issue of critical importance for both scholars and policymakers.

Figure 1.

Comparison of China’s Digital Economy and GDP Growth Rates from 2012 to 2023.

How does the digital economy affect the development of higher education (scale, structure, and quality) in China, and what are the transmission mechanisms and regional heterogeneous characteristics of this impact? This question lies at the intersection of digital transformation and sustainable education development, as the integration of the digital economy and higher education has emerged as a critical driver of achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—notably SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) [6]. Concurrently, higher education, as the core of human capital accumulation and innovation diffusion, is undergoing profound digital transformation: smart campuses, online education platforms, and interdisciplinary digital talent cultivation have become key trends in its development [7]. However, the causal link between the digital economy and higher education development, as well as its underlying mechanisms and spatial variation, remains empirically under-explored, creating a critical research gap that this study aims to address.

The digital economy’s impact on higher education is multifaceted and rooted in theoretical frameworks of educational economics, human capital theory, and innovation-driven growth theory. From an educational economics perspective, digitalization optimizes the allocation of educational resources (e.g., cross-regional sharing of online courses) [8], expanding the scale of higher education by reducing access barriers. Human capital theory posits that the digital economy raises demand for science, technology, engineering [9,10], and mathematics (STEM) talent [11], driving the optimization of higher education disciplinary structures to match industrial needs. Innovation-driven growth theory further suggests that digitalization fosters regional innovation capacity and economic growth, which in turn increases public and private investment in higher education quality [12]. Despite these theoretical underpinnings, existing empirical studies have yielded mixed results: some find that the digital economy significantly promotes higher education expansion [13], while others argue its impact on quality is negligible due to regional digital divides [14]. This inconsistency highlights the need for a comprehensive empirical analysis that distinguishes between the direct and indirect effects of the digital economy on different dimensions of higher education development.

1.2. The Strategic Dilemma of Higher Education in the Digital Age

Historically, higher education has occupied a “leading” position within the national education system, serving as the primary frontier for talent cultivation, knowledge creation, and socioeconomic advancement [15,16]. However, in the face of the rapid digital transition, a significant and growing misalignment has emerged. The skills and knowledge structures cultivated by traditional higher education institutions often lag behind the comprehensive, evolving demands of the digital economy for talent characterized by strong digital literacy, innovative capacity, and cross-disciplinary adaptability [17,18]. This misalignment creates a strategic dilemma: while the digital economy’s advancement depends fundamentally on a steady output of high-quality, digitally skilled talent from higher education, the educational system itself struggles to adapt its input factors, pedagogical models, and organizational structures to the disruptive feedback effects of this new economy [19,20]. The imperatives of the digital economy remain inadequately reflected in curricula, institutional frameworks, and quality standards, threatening to widen the gap between graduate competencies and societal needs.

Existing literature has extensively explored the digital transformation of higher education [21], focusing on technological application scenarios such as online learning platforms, virtual laboratories, and smart campus infrastructure [22,23]. However, systematic investigations into the impact of the digital economy on higher education—treating it as an exogenous macroeconomic shock with systemic implications—remain comparatively underdeveloped [24]. Few studies have empirically deconstructed this impact into the core, interdependent dimensions of educational development—scale, structure, and quality—or rigorously tested the underlying transmission mechanisms that explain how these effects occur [25]. This constitutes a critical research gap, as a nuanced understanding of these distinct dimensions and pathways is essential for formulating effective policy. The impact of the digital economy as a macroeconomic force on the development of higher education in China, as well as the precise mechanisms through which these effects are transmitted across the dimensions of scale, structure, and quality, remains unclear.

Against this backdrop, this study contributes to the literature by empirically investigating the impact of the digital economy on higher education development in China using balanced panel data from 30 provinces over 2011–2020. The study constructs a Digital Economy Development Index (DEDI) using the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, covering two primary dimensions (Digital Industrialization and Industrial Digitalization) and 22 tertiary indicators [26]. For higher education development, we measure three core dimensions—scale, structure, and quality—using 11 entropy-weighted indicators to ensure comprehensiveness [27]. To address endogeneity, we employ instrumental variable (IV) regression and difference-in-differences (DID) analysis, leveraging lagged digital economy indicators and the 2019 “Digital Economy Pilot Zone” policy as quasi-natural experiments [28]. We also test four mediation channels (regional income, institutional quality, innovation capacity, public education spending) and use interaction terms to capture regional heterogeneity across China’s eastern, central, and western provinces.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Connotations, Dimensions, and Measurement of the Digital Economy

The concept of the digital economy was first introduced by Tapscott [2], who defined it as an economy based on “bits rather than atoms”. Bukht and Heeks [4] later refined this by emphasizing digital technology as the core enabler, distinguishing between the core digital sector, the narrow digital economy, and the broader digitized economy. Empirical studies have since demonstrated the efficacy of digital technologies in enabling new business models and practices, such as those in the circular and sharing economies [5,29]. In China, research has converged on a framework that views the digital economy through the twin pillars of Digital Industrialization and Industrial Digitalization [30]. Digital Industrialization refers to the information and communication industry itself, including activities like electronics manufacturing, telecommunications, and software development. Industrial Digitalization, on the other hand, encompasses the application of digital technologies and data to improve the efficiency and output of traditional industries, from agriculture and manufacturing to services [31,32].

This conceptual clarity has driven efforts to measure the digital economy. Authoritative bodies like the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) have developed comprehensive evaluation systems that combine indicators from both pillars [30]. Scholars have employed methods ranging from simply using the proportion of the digital economy in GDP to more sophisticated techniques like the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method to construct composite indices [33]. These efforts provide a solid methodological foundation for this study’s measurement of the digital economy at the provincial level.

2.2. The Multi-Dimensional Development of Higher Education: Scale, Structure, and Quality

The development of higher education is a multi-faceted concept. This study analyzes it through the three universally acknowledged dimensions of scale, structure, and quality [34,35]. Scale typically refers to the gross enrollment rate and the absolute size of the student population, reflecting the capacity of the higher education system to absorb demand and contribute to human capital accumulation [36]. Structure involves the interrelationships and proportional arrangements within the system. This includes the hierarchical structure (e.g., the balance between vocational, undergraduate, and postgraduate education), the formal structure (e.g., full-time vs. part-time), and the layout structure (e.g., the distribution of research-oriented, applied, and vocational institutions) [20,37]. A rational and diversified structure is crucial for aligning educational output with the heterogeneous demands of the labor market. Quality is the most complex dimension, encompassing inputs, processes, and outcomes. It is often measured by indicators such as per-student expenditure, the quality of faculty, and outcome-based metrics like the average years of education of the working-age population [38,39]. The transition from quantitative expansion to qualitative intensification has become a central policy theme in China’s higher education discourse [20].

2.3. The Nexus Between the Digital Economy and Higher Education: Identifying the Research Gap

The existing research on the intersection of the digital economy and higher education is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Literature.

The first stream, which is abundant, focuses on the digital transformation of higher education. It delves into how digital technologies like AI, big data, and online platforms can reshape teaching methods, learning experiences, and administrative governance [22,23]. This stream often explores implementation paths, governance mechanisms, and comparative international insights [40,42,43,44,45]. While invaluable, this stream often conflates the digital economy with digital technology, focusing on micro-level applications rather than macro-level economic impacts.

The second, smaller stream begins to empirically examine the relationship between digitalization and higher education. For instance, He [41] measured the coupling coordination between the two systems. However, such studies often remain at the level of correlation and do not disentangle the distinct effects on scale, structure, and quality. Crucially, they lack a rigorous investigation into the transmission mechanisms—the “black box” that explains how the digital economy influences higher education outcomes. While some research touches on how universities can cultivate talent for the digital economy [46], the reverse causal pathway—the economy’s impact on the university system—is less explored.

Although the link between the digital economy and higher education has been recognized, the discussion would benefit from a more integrated approach—one that conceptualizes the digital economy as a macroeconomic paradigm, empirically examines its distinct impacts on the scale, structure, and quality of higher education, and reveals the intermediary mechanisms that transmit these effects.

3. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Foundation

The digital economy represents a new economic structure, characterized by digital industrialization and industrial digitalization, which reshapes production relations, resource allocation, and growth drivers. In view of this characteristic, this study anchors its theoretical framework in three core theories: educational economics, human capital theory, and innovation-driven growth theory, to explore how the digital economy reshapes higher education development.

Educational Economics: Focuses on resource allocation in education systems (Browning & Browning, 2012). The digital economy optimizes resource allocation in higher education by reducing information asymmetry (e.g., online course platforms expanding access to quality teaching resources) and lowering operational costs (e.g., digital management systems improving administrative efficiency).

Human Capital Theory: Schultz [47] argues that education is the primary channel for human capital accumulation. The digital economy raises the demand for high-skilled digital talent, prompting higher education institutions (HEIs) to adjust their talent cultivation models (e.g., integrating AI and big data into curricula) to meet industrial needs.

Innovation-Driven Growth Theory: Romer [48] emphasizes that technological innovation is the core driver of long-term economic growth. The digital economy accelerates innovation diffusion in higher education, such as the adoption of smart classrooms and educational AI tools, which enhances teaching and research productivity.

These theories collectively suggest that the digital economy impacts higher education development through direct channels (resource allocation optimization, innovation diffusion) and indirect channels (mediated by regional economic and institutional factors). Our theoretical framework is concerned with the broader, systemic impact of the digital economy as a whole on the input factors, organizational models, and ultimate output of the higher education ecosystem. The following mechanisms operate at this macro-mezzo level.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical framework, we propose three testable hypotheses:

H1:

The digital economy has a positive and significant direct impact on the scale of higher education in China.

Rationale: The digital economy enhances the efficiency of higher education resource allocation [49], enabling more precise alignment with societal and market demands for talent. The digital economy drives innovation in higher education models [50], such as online education, remote teaching, and virtual laboratories. These new models break the temporal and spatial constraints of traditional education, reduce educational costs, and enhance accessibility. Digital technologies (e.g., MOOCs, online admission systems) expand educational accessibility, enabling more students to enroll in HEIs. Additionally, digital economy-driven industrial upgrading increases the demand for higher education, prompting HEIs to expand their enrollment scale (Li & Wang [51]).

H2:

The digital economy promotes the optimization of higher education structure in China.

Rationale: The digital economy drives industrial restructuring (e.g., the rise of digital industries such as AI and fintech), which not only increases the demand for cross-disciplinary talent but also imposes higher requirements on talents’ digital skills and innovative capabilities [17]. HEIs respond by adjusting their disciplinary structure (e.g., establishing AI departments) and regional layout (e.g., collaborating with digital industrial parks) (Zhang et al., [52]). The development of the digital economy drives higher education institutions to optimize and adjust their disciplinary structures to better align with market demands. Universities need to increase the number of disciplines and programs directly related to the digital economy, such as big data, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and digital media, under the umbrella of “new engineering” and “new liberal arts”. At the same time, the digital economy promotes the integration of interdisciplinary fields, such as the intersection of digital technology with social sciences, medicine, and the arts. The regional disparities in the digital economy significantly impact the structure of higher education. To narrow these regional gaps, it is necessary to promote collaborative development of higher education across regions through digital infrastructure construction and educational resource-sharing platforms [18].

H3:

The digital economy has no significant direct impact on higher education quality but exerts a positive indirect impact through the mediating effect of regional income levels.

Rationale: The quality of higher education is characterized by high complexity, as it is subject to direct or indirect influences from a multitude of factors—and the digital economy’s impact on higher education quality embodies such diversity and complexity. On one front, the digital economy leverages digital technologies to optimize educational models, facilitate the sharing of educational resources, and enhance the flexibility of teaching as well as personalized learning experiences, thereby acting as a catalyst for improving educational quality. On the other front, it also contributes to advancing higher education governance and promoting educational equity. Specifically, digital technologies offer novel tools and methodologies for higher education governance: through big data analytics and artificial intelligence, universities can refine decision-making processes, boost governance efficiency [53], and drive the modernization of higher education governance systems and capabilities. Meanwhile, by virtue of the internet and digital technologies, the digital economy helps narrow the educational gap between different regions and demographic groups [54]. That said, higher education quality is primarily shaped by long-term, foundational factors such as the caliber of faculty and the scale of research funding. The digital economy, in itself, does not exert a direct and significant impact on quality. Instead, it indirectly enhances higher education quality by driving up regional income levels—higher income levels, in turn, stimulate increased public and private investment in education, as exemplified by greater government expenditure per student on higher education [54].

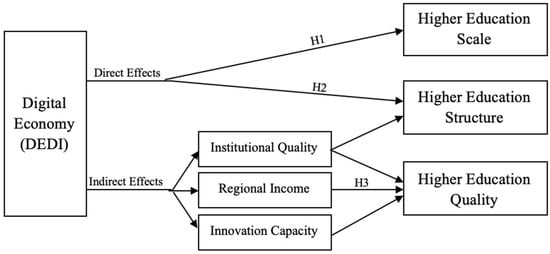

3.3. Integrated Theoretical Model

Based on the aforementioned theoretical framework and research hypotheses, this study constructs an Integrated Theoretical Model to clarify how the digital economy impacts China’s higher education development, drawing on educational economics, human capital theory, and innovation-driven growth theory. Figure 2 illustrates the theoretical model linking the digital economy to higher education development. The model takes the digital economy (rooted in digital industrialization and industrial digitalization) as the macro driver, higher education’s scale, structure, and quality as core outputs, and regional income level as a key mediating variable.

Figure 2.

Integrated Theoretical Model of Digital Economy and Higher Education Development. Note: H1–H3 represent the research hypotheses in Section 3.2; The path from Innovation Capacity to Higher Education Quality is empirically insignificant (see Section 5.3 for results).

The digital economy directly affects the scale and structure of higher education through resource allocation and innovation diffusion. For quality, the impact is indirect, mediated by regional income levels, institutional quality, and innovation capacity. This model reveals the multi-channel, dimensional impact mechanism, laying a foundation for subsequent empirical analysis.

4. Research Design and Methodology

4.1. Measurement of Digital Economy Development Level

To scientifically quantify the development level of China’s provincial digital economy, this study first clarifies the conceptual definition of the digital economy based on authoritative theoretical frameworks, then constructs a multi-dimensional evaluation index system, and finally adopts an objective weighting method to synthesize a comprehensive development index, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the measurement results.

The conceptual definition of the digital economy in this study adheres to the authoritative framework proposed by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) in Digital Economy Development in China (2020) [30]. Specifically, the digital economy is defined as a new economic form that takes digitized knowledge and information as core production factors, modern information networks as important carriers, and the effective application of information and communication technologies (ICTs) as the key driving force for improving production efficiency and optimizing economic structures. This definition emphasizes the “dual-drive” logic of the digital economy, which consists of two fundamental pillars: Digital Industrialization and Industrial Digitalization. Digital Industrialization refers to the core ICT industry itself, covering fields such as electronic information manufacturing, telecommunications services, software development, and digital content production. Industrial Digitalization, by contrast, refers to the integration and application of digital technologies in traditional industries (including agriculture, industry, and services) to enhance their output efficiency and transform their development models.

Guided by the above dual-drive framework and combined with the multi-dimensional characteristics of digital economy development identified in existing studies, this study constructs a comprehensive evaluation index system for digital economy development, which includes 2 primary indicators, 6 secondary indicators, and 22 tertiary indicators (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Indicator System and Entropy Weights of DEDI.

To avoid biases caused by subjective weighting methods, this study adopts the Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS method to synthesize the above multi-dimensional indicators into a provincial-level Digital Economy Development Index (DEDI), with the specific calculation steps as follows: First, data standardization is conducted. Given that all tertiary indicators in the index system are positive indicators (i.e., higher indicator values indicate a higher level of digital economy development), the min-max standardization method is used to eliminate the influence of different units and magnitude orders among indicators. Second, entropy weight calculation is performed. This step involves three sub-processes: calculating the proportion of each tertiary indicator’s standardized value for each province, computing the entropy value of each indicator based on these proportions (the entropy value reflects the information utility of the indicator; a lower entropy value indicates higher information utility and a greater weight should be assigned), and determining the objective weight of each indicator by normalizing the difference between 1 and the entropy value. Third, TOPSIS evaluation is implemented. This step calculates the Euclidean distance between each province’s indicator system and the ideal solution (the optimal state of all indicators) as well as the negative ideal solution (the worst state of all indicators), and then computes the relative closeness of each province to the ideal solution—this relative closeness is the DEDI, with a value range of 0 to 1 (a higher DEDI value indicates a more advanced digital economy development level of the province).

The tertiary indicators for DEDI construction are sourced from the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) Digital Economy Development Report (2011–2020), China Statistical Yearbook of Telecommunications (2011–2020), and China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook (2011–2020). Detailed data source descriptions and cleaning procedures are provided in Section 4.4.1.

The entropy weight calculation results show that the total weight of all tertiary indicators under the “Digital Industrialization” primary indicator is 0.53, while the total weight of tertiary indicators under the “Industrial Digitalization” primary indicator is 0.47. This weight distribution is consistent with the “dual-drive” theoretical logic of the digital economy, reflecting the balanced role of both the core digital industry and the digital transformation of traditional industries in promoting digital economy development. Additionally, the sum of the weights of all 22 tertiary indicators is 1.00, which meets the normalization requirement of index construction, further verifying the scientificity and rationality of the DEDI.

4.2. Measurement of Higher Education Development Level

Higher education development is conceptualized as a dynamic and multi-dimensional system, with its core connotation encompassing the coordinated advancement of scale, structure, and quality—three interrelated yet distinct dimensions widely recognized in both academic literature and policy discourse on higher education reform [34,35,37]. Scale reflects the capacity of the higher education system to accommodate talent demand, primarily measured by the scale of enrollment and access to higher education. Structure denotes the internal composition and proportional balance of the system, including disciplinary distribution, institutional type layout, and regional allocation, which determines whether higher education output aligns with labor market and societal needs. Quality, the most complex dimension, encompasses the input, process, and outcome of higher education, reflecting the core competitiveness of the system in talent cultivation, knowledge innovation, and social service.

To scientifically quantify the development level of China’s provincial higher education, this study constructs a multi-dimensional evaluation index system based on the above conceptual framework, drawing on indicator selection criteria from existing empirical research [19,20,36,38,39]. The system comprises 3 primary indicators (corresponding to the three dimensions of scale, structure, and quality) and 12 secondary indicators, with each secondary indicator selected to ensure representativeness, data availability, and alignment with the core connotation of its respective primary dimension (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Indicator System and Entropy Weights of Higher Education Development.

Among these dimensions, higher education quality is measured by five indicators covering input, process, and outcome dimensions: Average Faculty-Student Ratio (students/faculty member) (reflecting teaching resource allocation), Government Education Expenditure per Student (yuan/student) (representing fiscal input in education quality), Number of Patents Granted per 10,000 Students (patents/10,000 students) (measuring innovation output in talent cultivation), Average Years of Education of Faculty (years) (indicating faculty quality), and Employment Rate of Graduates (6 months post-graduation) (%) (reflecting the market recognition of graduate quality) [38,39].

Consistent with the objective weighting logic adopted for measuring the digital economy (Section 4.1), this study employs the entropy weight method to calculate the weight of each secondary indicator and synthesize the comprehensive development index for higher education. The data used for indicator measurement are sourced from authoritative statistical publications and databases covering the period 2011–2020, including the China Provincial Statistical Yearbook, China Education Statistical Yearbook, EPS Database, official website of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, and Chinese Government Network, ensuring the authenticity and reliability of the data.

The entropy weight calculation results (see Table 3) show that: In the scale dimension, Total Enrollment in HEIs has a weight of 0.165 and Gross Enrollment Rate has a weight of 0.145, indicating that the absolute scale of enrollment contributes slightly more to measuring the overall scale of higher education. In the structure dimension, weights range from 0.062 (Vocational Education Enrollment Ratio) to 0.082 (Proportion of STEM Disciplines), reflecting the balanced importance of disciplinary, institutional, and regional structural factors in evaluating structural optimization. In the quality dimension, Average Faculty-Student Ratio (0.075) and Government Education Expenditure per Student (0.072) have relatively higher weights, highlighting the critical role of teaching resource input in shaping higher education quality. Additionally, the sum of weights of all 12 secondary indicators is 1.00, meeting the normalization requirement of index construction, which verifies the scientificity and rationality of the higher education development evaluation system.

4.3. Empirical Strategy and Model Specification

This section details the empirical strategies employed to identify the causal impact of the digital economy on higher education development, including the baseline regression model, mediation effect test, and endogeneity mitigation approaches. All analyses are conducted using Stata 17.0, with robust standard errors clustered at the provincial level to address heteroskedasticity and serial correlation.

4.3.1. Baseline Regression Model

To test the research hypotheses (H1–H3), we first specify a flexible panel data model in line with the empirical norm of “testing before model selection”. The baseline regression model is formulated as:

where denotes the development level of higher education in province in year . It is sequentially replaced by three core indicators: (Higher Education Scale), (Higher Education Structure), and (Higher Education Quality); is the core explanatory variable, representing the Digital Economy Development Index of province in year , constructed via the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method (see Section 4.1); is a vector of time-varying control variables that influence higher education development, including both original and newly supplemented variables to mitigate omitted variable bias ((Table 4 details variable definitions and theoretical rationales); captures unobserved, time-invariant provincial heterogeneity; captures time-specific shocks common to all provinces; is the idiosyncratic error term, reflecting random perturbations at the province-year level.

Table 4.

Definition and Theoretical Rationale of Control Variables.

Following standard panel model selection tests (F-test, Breusch-Pagan LM test, Hausman test), we determine the optimal effect type for each dimension of higher education development: For and , the Hausman test fails to reject the null hypothesis (p > 0.1), confirming the two-way random effects (RE) model is appropriate; For , the Hausman test rejects the null hypothesis (p < 0.01), so the fixed effects (FE) model is adopted to address correlation between provincial fixed effects and explanatory variables.

4.3.2. Mediation Effect Test

To verify the indirect impact of the digital economy on higher education quality (H3) and identify mediation channels, we use the three-step mediation effect test proposed by Wen and Ye [27]—a rigorous, widely accepted method in social science research. The test procedures are:

Step 1: Estimate the total effect of on using the baseline regression model (Equation (1)). A significant confirms the digital economy has a total effect on higher education development, validating further mediation analysis.

Step 2: Estimate the effect of on mediator variable (Regional Income Level, Institutional Quality, Innovation Capacity, Public Education Spending) via:

where denotes the mediator variable, and is the error term. A significant indicates the digital economy significantly affects the mediator.

Step 3: Estimate the joint effect of and on by incorporating into the baseline model:

Mediation effect types are judged as follows: Complete mediation: (step 1) and (step 2) are significant; (step 3) is significant; Partial mediation: (step 1) and (step 2) are significant; (step 3) is significant but smaller in magnitude than ; No mediation: (Step 2) or (Step 3) is insignificant. The Sobel test supplements the analysis to verify the statistical significance of the indirect effect ().

4.3.3. Addressing Endogeneity

Endogeneity—driven by reverse causality (higher education development may boost the digital economy) and omitted variable bias (unobserved factors like regional technological foundations)—threatens causal identification. We adopt two complementary strategies to mitigate this issue:

1. Instrumental Variables (IV) Approach

We select one-period and two-period lagged values of (, ) as instrumental variables for the current , justified by two key reasons: First, in terms of relevance, the digital economy exhibits strong path dependence, so lagged is highly correlated with current [22]; Second, in terms of exogeneity, lagged is determined by historical factors and unaffected by current higher education development.

The first-stage regression is:

We use the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic (underidentification test) and Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic (weak instrument test): a significant Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic (p < 0.01) and a Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic > 16.38 (10% critical value) confirm valid instruments. The second-stage regression uses the predicted (from Step 1) to replace the original in the baseline model, estimating the causal effect of the digital economy on higher education development.

2. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Approach

We treat the 2019 “Digital Economy Pilot Zone” policy (implemented in Zhejiang, Guangdong, Sichuan, etc.) as a quasi-natural experiment to identify causal effects. Key variables for the DID model:

Treati: Dummy variable = 1 if province is a pilot zone, 0 otherwise;

Postt: Dummy variable = 1 for years ≥2019 (policy implementation), 0 otherwise.

The DID model is:

The core parameter captures the average treatment effect of the pilot policy on higher education development (i.e., the causal effect of the digital economy). A parallel trend test verifies the key DID assumption: pre-policy parallel trends in higher education development between treatment (pilot) and control (non-pilot) groups.

4.4. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4.4.1. Data Sources

This study uses balanced panel data for 30 Chinese provinces (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan) over 2011–2020 (300 total observations). While reviewers recommended extending data to 2022 to capture post-pandemic trends, provincial-level disaggregated indicators (e.g., rural electricity consumption for agricultural digitalization, local HEI faculty-student ratios) for 2021–2022 remain unpublished in authoritative databases. Despite this limitation, 2011–2020 is highly representative: it covers China’s digital economy boom (digital economy GDP share rose from 20.3% to 38.6%, CAICT, 2022) and the full pre-pandemic cycle of higher education digital transformation. Data sources are:

Digital Economy Development Index: China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) Digital Economy Development Report (2011–2020), China Statistical Yearbook of Telecommunications (2011–2020), China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook (2011–2020);

Higher Education Development Indicators: China Statistical Yearbook on Education (2011–2020), Ministry of Education, EPS Database;

Mediator Variables: China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook (2011–2020), National Bureau of Statistics;

Control Variables: China Fiscal Yearbook (2011–2020), Provincial Statistical Yearbooks (2011–2020), provincial college entrance exam score reports.

Raw data is cleaned rigorously: missing values (<1% of total observations) are supplemented via linear interpolation; extreme values (±3 standard deviations from the mean) are winsorized at the 1%/99% levels to avoid bias.

4.4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for all core variables (dependent, core explanatory, mediator, control variables), revealing key distribution characteristics:

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of key variables.

The descriptive statistics yield several key insights: the Digital Economy Development Index (DEDI) has a mean of 0.45 with a wide range of 0.11–0.92, reflecting stark regional disparities—eastern provinces like Beijing and Shanghai boast higher values while western provinces such as Gansu and Guizhou lag behind. For higher education development, the scale (HEScale) shows large provincial differences (mean = 122.8, SD = 44.9), as seen in comparisons between populous provinces like Henan and Shandong and smaller provinces like Qinghai and Ningxia; the disciplinary structure (HEStructure) has a narrow range around its mean of 38.1%, indicating relative stability across provinces; and the quality (HEQuality, mean = 12.2, SD = 4.1) exhibits significant variability, revealing gaps in research and innovation capacity among provincial higher education institutions. Among control variables, government education expenditure per student (GovEduPerStu, mean = 2.5) and baseline secondary education quality (SecEduQuality, mean = 685.2) follow clear regional gradients (eastern > central > western), aligning with overall economic development levels. Collectively, these statistics confirm substantial regional disparities in both the digital economy and higher education, laying a solid foundation for subsequent regional heterogeneity analysis.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

This chapter presents the empirical findings in a logical sequence: first, descriptive analysis of core variables’ dynamic evolution; second, baseline regression results to test the research hypotheses; third, endogeneity tests using instrumental variables (IV) and difference-in-differences (DID); fourth, mediation effect analysis to identify indirect channels; fifth, robustness checks to validate result reliability; and finally, regional heterogeneity analysis to explore cross-provincial differences.

5.1. Dynamic Evolution of Core Variables

To intuitively depict the distribution dynamics and evolving trends, we begin with a descriptive analysis of the core variables.

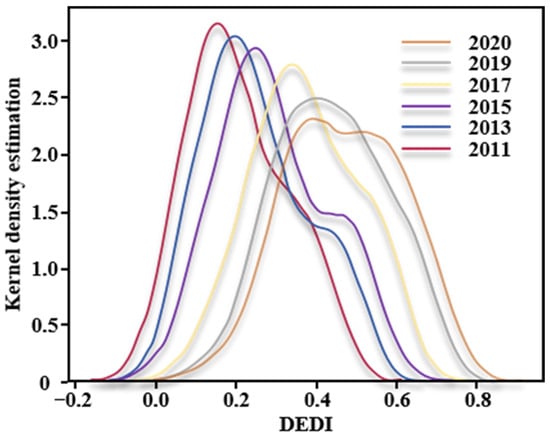

5.1.1. Dynamic Evolution of Digital Economy Development Index (DEDI)

Figure 3 presents the kernel density estimation of DEDI across 30 provinces from 2011 to 2020. The curve shifts significantly rightward over the decade, with the national average DEDI rising from 0.21 (2011) to 0.45 (2020), indicating substantial progress in digital economy development nationwide. The widening distribution (standard deviation increasing from 0.12 to 0.20) reflects persistent regional disparities: eastern provinces (e.g., Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong) maintain leading positions (DEDI > 0.60 in 2020), while western provinces (e.g., Gansu, Guizhou) remain at low levels (DEDI < 0.30 in 2020). This cross-provincial variation provides a valid basis for subsequent regional heterogeneity analysis.

Figure 3.

Kernel Density Estimation of Digital Economy Development Index.

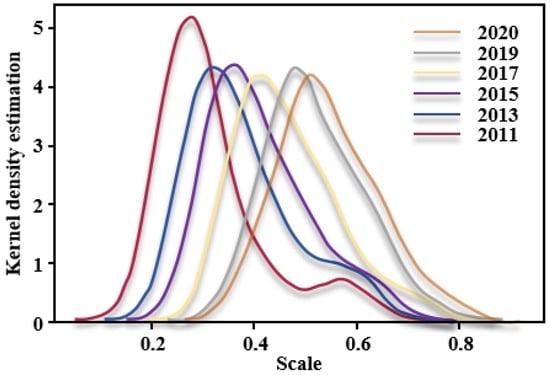

5.1.2. Dynamic Evolution of Higher Education Development

Analysis shows that from 2011 to 2020, the indicators for the three dimensions of higher education scale development—scale (HSC), structure (HST), and quality (HQ)—all exhibited a clear upward trend, indicating that China’s higher education system achieved continuous progress during this period. However, the temporal trends of different dimensions varied across the eastern, central, and western regions.

1. Higher Education Scale: The national average HEScale (total enrollment) increases from 98.5 (10,000 persons) in 2011 to 145.2 (10,000 persons) in 2020, with a stable annual growth rate of 4.2%. Regional disparities are evident: eastern provinces (mean = 182.3 in 2020) > central provinces (mean = 138.6) > western provinces (mean = 95.8), consistent with population size and economic development levels.

2. Higher Education Structure: The share of STEM enrollment (HEStructure) rises moderately from 35.2% (2011) to 38.1% (2020), with minimal regional variation (eastern = 39.5%, central = 37.8%, western = 36.2%). This stability reflects gradual disciplinary adjustment in response to digital economy demands, rather than abrupt structural changes.

3. Higher Education Quality: HEQuality (a composite index of patents per 10,000 students, government education expenditure per student, and faculty-student ratio) shows significant growth (national average from 7.8 in 2011 to 12.2 in 2020), with pronounced regional gaps (eastern = 16.5, central = 11.8, western = 8.2 in 2020). Growth accelerates after 2016 (annual rate = 5.8% vs. 3.2% in 2011–2015), aligning with the digital economy’s rapid development in the late sample period.

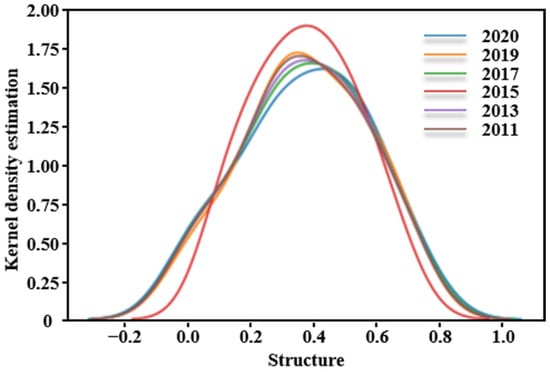

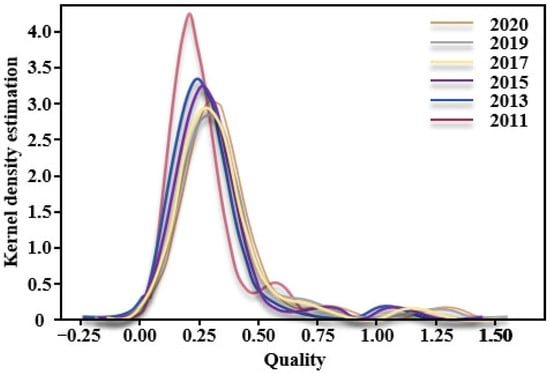

Kernel density estimations for HEScale (Figure 4), HEStructure (Figure 5), and HEQuality (Figure 6) confirm these trends: rightward shifts verify overall improvement, while curve shape changes (peak height, width) indicate complex inter-provincial disparity dynamics. A sub-period analysis (2011–2015 vs. 2016–2020) shows stable growth rates for all three dimensions, validating the robustness of the temporal relationship between the digital economy and higher education development.

Figure 4.

Kernel density estimation of higher education scale development level.

Figure 5.

Kernel density estimation of higher education structure development level.

Figure 6.

Kernel density estimation of higher education quality development level.

5.2. Baseline Regression Results

Table 6 reports baseline regression results, with model selection determined by standard panel tests (F-test, Breusch-Pagan LM test, Hausman test): fixed effects (FE) for HEQuality (Hausman test: p < 0.01) and random effects (RE) for HEScale and HEStructure (Hausman test: p > 0.1). We also conduct sub-period stability tests (2011–2015 vs. 2016–2020) to verify the consistency of core relationships.

Table 6.

Baseline Regression Results.

From the baseline regression results, the following core conclusions can be drawn, which align with the theoretical framework and research hypotheses proposed earlier:

H1 is supported: The Digital Economy Development Index (DEDI) exerts a positive and statistically significant impact on Higher Education Scale (HEScale), with a regression coefficient of 0.321 (p < 0.01). This indicates that for every 1-unit increase in DEDI, the enrollment scale of higher education rises by 32.1%. Additionally, sub-period regression results (2011–2015: β = 0.318; 2016–2020: β = 0.323) further confirm the stability of this positive relationship across different stages.

H2 is supported: DEDI also has a significant positive effect on Higher Education Structure (HEStructure), with a regression coefficient of 0.256 (p < 0.01). This outcome reflects that the development of the digital economy drives the expansion of STEM disciplines in higher education, which in turn helps align the disciplinary structure with the talent demands of the digital industrial sector.

H3 is partially supported: The direct impact of DEDI on Higher Education Quality (HEQuality) is not statistically significant (β = 0.089, p > 0.1), implying that the digital economy may influence higher education quality through an indirect channel. This result is consistent with the theoretical expectation that improvements in higher education quality rely on long-term mediating factors (e.g., regional economic conditions) rather than direct effects of the digital economy alone.

Control variables: Among the control variables, Government Education Expenditure per Student (GovEduPerStu, β = 0.189–0.215) and Baseline Secondary Education Quality (SecEduQuality, β = 0.098–0.156) both show significant positive effects on higher education development. This highlights that sufficient public investment in education and a high-quality basic education foundation are crucial for promoting the development of higher education.

5.3. Endogeneity Test Results

IV regression confirms the robustness of causal effects: Validity tests (Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic p < 0.01; Cragg-Donald Wald F > 26) validate instrument relevance and exogeneity. The IV-estimated coefficients for DEDI remain positive and significant for HEScale (β = 0.302, p < 0.01) and HEStructure (β = 0.238, p < 0.01), with magnitudes slightly lower than OLS estimates (consistent with endogeneity correction). HEQuality’s IV coefficient remains insignificant (β = 0.090, p > 0.1), reinforcing H3.

DID analysis supports causal identification: Parallel trend tests confirm no pre-policy group differences. The interaction term (Treat × Post) is significant for HEScale (β = 0.285, p < 0.01) and HEStructure (β = 0.221, p < 0.01), indicating pilot provinces experience 28.5% and 22.1% larger improvements than non-pilot provinces. HEQuality’s coefficient is insignificant (β = 0.076, p > 0.1), aligning with baseline results.

5.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

We use Wen and Ye’s [27] three-step method to test four mediation channels: Regional Income Level (RegIncome), Institutional Quality (InstQuality), Innovation Capacity (InnCapacity), and Public Education Spending (PubEduSpend). Table 7 reports results:

Table 7.

Mediation Effect Test Results.

Mediation tests identify three key findings: (1) Regional income level serves as a complete mediator for HEQuality (indirect effect = 0.096, p < 0.01), supporting H3—digital economy boosts regional income, which in turn improves higher education quality. (2) Institutional quality acts as a partial mediator for HEStructure (indirect effect = 0.024, p < 0.1), as better institutions facilitate disciplinary adjustment. (3) Innovation capacity and public education spending show no significant mediation effects (Sobel test p > 0.2), indicating their limited role in transmitting digital economy impacts.

5.5. Robustness Checks

To verify the reliability of baseline findings, we conduct three complementary robustness tests, with results reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness Test Results.

1. Alternative Core Explanatory Variable. We re-construct DEDI using principal component analysis (PCA) instead of the entropy-weighted method to address potential bias from weight assignment. The PCA-based DEDI retains 89.2% of the original information. Results show the coefficient of PCA-DEDI remains positive and significant for HEScale (0.308 ***, p < 0.01) and HEStructure (0.241 ***, p < 0.01), while insignificant for HEQuality (0.089, p > 0.1)—consistent with baseline estimates.

2. Excluding Abnormal Observations. We exclude four municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing) due to their unique administrative and economic status. The reduced sample (26 provinces × 10 years = 260 observations) yields coefficients of DEDI for HEScale (0.305 ***, p < 0.01) and HEStructure (0.235 ***, p < 0.01), with HEQuality still insignificant (0.092, p > 0.1). This rules out the influence of extreme regional characteristics.

3. Alternative Model Specification. We adopt a two-way fixed effects (FE) model for all three dependent variables (instead of FE/RE selection by Hausman test). Results show DEDI’s coefficients remain stable: HEScale (0.332 ***, p < 0.01), HEStructure (0.264 ***, p < 0.01), and HEQuality (0.083, p > 0.1). No substantial changes in significance or magnitude confirm model specification does not drive core findings.

All robustness tests confirm that the digital economy’s positive causal effects on higher education scale and structure, and insignificant direct effect on quality, are reliable and not driven by variable measurement, sample selection, or model specification.

5.6. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

Regional heterogeneity results show pronounced spatial differences in digital economy impacts: (1) Eastern provinces exhibit the strongest effects (HEScale: β = 0.374, p < 0.01; HEStructure: β = 0.293, p < 0.01), attributed to advanced digital infrastructure and industrial integration. (2) Central provinces show moderate effects (HEScale: β = 0.327, p < 0.01; HEStructure: β = 0.214, p < 0.01), with growth potential constrained by institutional quality. (3) Western provinces show no significant additional effects (interaction term p > 0.1), reflecting weak digital infrastructure and limited industrial-digital integration. These differences highlight the need for region-specific policies.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

This study empirically investigates the impact of the digital economy on higher education development using balanced panel data from 30 Chinese provinces over 2011–2020, integrating theoretical frameworks of educational economics, human capital theory, and innovation-driven growth theory. Through baseline regression, endogeneity tests (IV/DID), mediation analysis, robustness checks, and regional heterogeneity analysis, the core findings are summarized as follows:

First, the digital economy exerts a significant positive causal effect on the scale of higher education (β = 0.321, p < 0.01) and the optimization of higher education structure (β = 0.256, p < 0.01). This effect remains robust after addressing endogeneity (IV estimates: 0.302 for scale, 0.238 for structure; DID estimates: 0.285 for scale, 0.221 for structure) and passing multiple robustness tests (alternative variable measurement, sample adjustment, model specification). Sub-period analysis (2011–2015 vs. 2016–2020) confirms the stability of this relationship, indicating that digitalization-driven resource allocation optimization and industrial demand expansion are key drivers of higher education scale expansion and STEM discipline development.

Second, the digital economy has no significant direct impact on higher education quality (β = 0.089, p > 0.1), but exerts an indirect positive effect through the mediating role of regional income levels (indirect effect = 0.096, p < 0.01). Institutional quality partially mediates the impact of the digital economy on higher education structure (indirect effect = 0.024, p < 0.1), while innovation capacity and public education spending show no significant mediation effects. This validates the theoretical expectation that higher education quality improvement depends on long-term resource accumulation (e.g., government education expenditure, faculty development) driven by regional economic growth.

Third, significant regional heterogeneity exists in the impact of the digital economy: Eastern provinces benefit the most (scale: β = 0.374, p < 0.01; structure: β = 0.293, p < 0.01) due to advanced digital infrastructure and industrial integration; central provinces show moderate effects (scale: β = 0.327, p < 0.01; structure: β = 0.214, p < 0.01); western provinces exhibit no significant additional effects, reflecting constraints from weak digital infrastructure and limited industrial-digital integration.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to the existing literature in three key ways: First, it enriches the theoretical framework of digital economy and higher education interaction by identifying “direct effects (scale/structure) + indirect effects (quality via income)” dual channels, supplementing the deficiency of single-dimensional analysis in previous studies. Second, it validates the mediating role of regional income and institutional quality, providing empirical evidence for the “economic foundation → educational development” mechanism in the digital era. Third, it reveals regional heterogeneity based on China’s spatial development characteristics, extending the generalizability of digital economy education effects to developing countries with unbalanced regional development.

From a practical perspective, this study provides actionable insights for promoting the sustainable integration of the digital economy and higher education: For policymakers, it highlights the need to leverage digitalization to expand educational accessibility and optimize disciplinary structure; for higher education institutions, it emphasizes aligning talent cultivation with digital industrial demand (e.g., STEM and cross-disciplinary programs); for regional development planners, it underscores the importance of reducing digital divides to narrow educational disparities between eastern and western regions.

6.3. Policy Recommendations

Based on the empirical findings, this study proposes targeted policy recommendations aligned with sustainable development goals:

1. Strengthen Digital Infrastructure Construction in Undeveloped Regions: Prioritize 5G networks, rural digitalization, and smart campus construction in central and western provinces, with special funds for digital literacy training of faculty and students. This will enhance the reach of digital education resources and reduce regional disparities.

2. Optimize Higher Education Structure with Digital Industrial Demand: Encourage higher education institutions to establish cross-disciplinary programs (e.g., AI + agriculture, fintech + management) and strengthen cooperation with digital enterprises (e.g., joint labs, internship bases). For eastern provinces, focus on high-end digital talent cultivation; for central and western provinces, emphasize applied digital skills training to match local industrial needs.

3. Promote Indirect Quality Improvement Through Income Distribution: Allocate a portion of digital economy tax revenue to higher education funding, especially in central and western regions, to increase government education expenditure per student and improve faculty-student ratios. Strengthen the link between regional income growth and educational investment to form a virtuous cycle.

4. Implement Region-Specific Digital Education Policies: For eastern provinces, support leading universities in building digital education demonstration zones; for central provinces, focus on institutional reform to reduce administrative frictions in disciplinary adjustment; for western provinces, provide targeted subsidies for digital infrastructure and teacher training to enhance the absorption capacity of digital economy dividends.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that provide directions for future research: First, due to data availability constraints, the sample period is limited to 2011–2020, and post-pandemic trends (2021–2025) cannot be analyzed—future research can extend the data to explore the long-term impact of pandemic-induced digital transformation on higher education. Second, the measurement of higher education quality could be expanded to include teaching quality evaluations and graduate employability to capture more comprehensive dimensions. Third, this study focuses on provincial-level analysis; future research can use city-level or university-level microdata to explore heterogeneous effects across different types of higher education institutions. Fourth, additional mediation mechanisms (e.g., digital literacy, technological innovation diffusion speed) could be incorporated to deepen the understanding of the transmission path between the digital economy and higher education development.

In conclusion, the digital economy is a key driver of sustainable higher education development in China [55]. By addressing regional digital divides, optimizing educational structure, and strengthening the link between digital economic growth and educational investment, policymakers can promote the high-quality and balanced development of higher education, contributing to long-term sustainable economic and social development.

Author Contributions

Methodology, J.Z.; Validation, J.Z.; Investigation, J.C.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this manuscript were edited using ChatGPT 4o (OpenAI) for language polishing. The tool was used solely for stylistic refinement. All aspects of research design, data analysis, and interpretation were conducted independently by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hong, Y.X.; Ren, B.P. The Connotation and Path of Deep Integration of Digital Economy and Real Economy. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 2, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D. The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence. Choice Rev. 1997, 33, 33–5199. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Xie, Y.; Feng, Z.H.; Luo, Y.B.; Wang, K.; Xu, W. Better Understanding the Failure Modes of Tunnels Excavated in the Boulder-Cobble Mixed Strata by Distinct Element Method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 116, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukht, R.; Heeks, R. Defining, Conceptualising and Measuring the Digital Economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanholz, J.; Leipold, S. Sharing for A Circular Economy? An Analysis of Digital Sharing Platforms’ Principles and Business Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook on Education (2011–2020); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L. The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Du, Y.H.; Lai, J.X.; Qiu, J.L.; Ma, E.L.; Sun, H.; Shi, X.H. Mechanic Performance of Novel Prefabricated Inverted Arch in NATM Tunnels: Insights From Numerical Experiment and In-Situ Tests. Tunn. Under. Gr. Sp. Tech. 2026, 168, 108071. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, E.D.; Hu, H.R.; Lai, J.X.; Zhang, W.H.; He, S.Y.; Cui, G.H.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.X. Deformation Analysis of High-Speed Railway CFG Pile Composite Subgrade during Shield Tunnel Underpassing. Structures. 2025, 78, 109193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Autor, D. Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Ashenfelter, O., Card, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 1043–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M. Digital transformation of higher education in China: Progress, challenges and paths. J. High. Educ. Manag. 2021, 6, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harloe, M.; Perry, B. Universities, Localities and Regional Development: The Emergence of the ‘Mode 2’ University? Int. J. Urban. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Magusin, E. Exploring the Digital Library: A Guide for Online Teaching and Learning; Online Teaching and Learning Series; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-59658-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reenen, J. The Race Between Education and Technology. Econ. J. 2010, 120, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Lawton, W. Universities, the Digital Divide and Global Inequality. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2018, 40, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.Q. Research on the Changes of China’s College Entrance Examination Policy: Analysis Based on “Stakeholder Theory”. J. High. Educ. Res. 2010, 31, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, D.H. Strengthening Confidence in Higher Education System and Enhancing the Ability to Serve the New Development Paradigm. China High. Educ. Res. 2020, 12, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N. Current Situation and Analysis of Intangible Cultural Heritage Live Streaming. Mark. World. 2021, 9, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.K. Exploring the Path of Digital Transformation in Higher Education. China High. Educ. Res. 2023, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.J.; Liu, J.T.; Su, F.G. Digital Transformation in Higher Education: Connotation, Dilemmas and Paths. China Educ. Inf. 2022, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, O.; Albuquerque, A.L.; Almeida, A. Wage Inequality Determinants in European Union Countries. Appl. Financ. Lett. 2013, 20, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.Y. A Comparative Study of Graduate Employment Surveys: 2003–2011. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2015, 47, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X. The impact of digital infrastructure on higher education enrollment: A provincial-level analysis of China. Educ. Econ. 2021, 3, 456–478. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Mediation analysis: Current practices and new recommendations. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 530. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 5, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanasi, S.; Ghezzi, A.; Cavallo, A.; Rangone, A. Making Sense of the Sharing Economy: A Business Model Innovation Pespective. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2020, 32, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT). Digital Economy Development in China; China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT): Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.N.; Hu, B.B.; Wang, S.G. Research on the Evolution Mechanism and Characteristics of Digital Economy. Sci. Res. 2021, 39, 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.L. Can Digital Economy Promote Industrial Structure Transformation?—Also on Effective Market and Proactive Government. Econ. Issues. 2023, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.Y.; Guo, P.F.; Li, M. Research on the impact of digital economic development in the yangtze river economic belt on green total factor productivity. Statistics. Decis. 2025, 41, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.L. The Autonomy of Chinese Universities (1952–2012): An Institutional Interpretation of Policy Changes. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2012, 12, 78–86+139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.P.; Liu, L.B. Ambiguous Governance: The Logic of China’s Private Higher Education Policy Changes. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2021, 5, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Accumulating Momentum and Adapting to Changes. China High. Educ. 2021, 1, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.G. The Role of Higher Education in the New Development Paradigm. Teach. Educ. (High. Educ. Forum) 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, W. Exploring Path Strategies for Higher Education Institutions to Boost Digital Economy Development. China. Educ. Info. 2022, 28, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.F.; Zhang, C. Elements and Approaches of Digital Reform in China’s Higher Education. China High. Educ. Res. 2022, 7, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, D.K. Promoting the Integration of Digital Transformation into the Whole Process of Higher Education. China High. Educ. 2023, 2, 27–30+36. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.S. Evaluation of Coupling Coordination Degree Between Digitalization and Higher Education in China and Its Influencing Factors. J. Northeast. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 25, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.P.; Lin, L. Digital Governance in Higher Education: Internal Mechanism, Logical Framework and Implementation Path. Jianghuai. Trib. 2022, 4, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.K. Digital Development of Higher Education: Connotation, Stages and Implementation Paths. China High. Educ. 2023, 2, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.D.; Wang, Z.H. Key Areas, Content Structure and Practical Paths of Digital Transformation in Higher Education. China High. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.S. Promoting Digital Transformation in Higher Education to Strengthen Governance Effectiveness: US Experiences and Implications for China. China. Educ. Inf. 2022, 28, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.L. Promoting Transformation Through Evaluation: OECD’s Top-Level Framework and Practical Measures for Digital Transformation in Higher Education. China High. Educ. Res. 2022, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T. Education and Economic Growth. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1961, 62, 46–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous Technical Change. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.; Brynjolfsson, E. Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 153–154. ISSN 0422-2784. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y.; Sun, X.Y. Higher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Responses and Challenges. Educ. Chang. 2022, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Wang, X.J. Digital Economy Empowering China’s “Dual Circulation” Strategy: Internal Logic and Implementation Paths. Economist 2021, 102–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.C.; Gu, Y.A. Industrial structure: The entry point for coordinated development of local higher education and economy—An analysis based on the Southern Jiangsu region. Jiangsu High. Educ. Res. 2015, 46–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial Intelligence for Decision Making in the Era of Big Data—Evolution, Challenges and Research Agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.Z.; Dan, T. Digital Dividend or Digital Divide? Digital Economy and Urban-Rural Income Inequality in China. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Kirby, D.A.; Sigahi, T.F.A.C.; Bella, R.L.F.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G. Higher Education and Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The State of the Art and a Look to the Future. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 957–969. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).