Abstract

Background: Understanding how Regional Innovation Systems (RISs) drive innovation outputs remains a central question in innovation studies. Most existing empirical research relies on linear or single-indicator models, which fail to capture nonlinear interactions among the key RIS dimensions—Firms, Knowledge, Government, and Economy. Methodology: This study proposes an integrated analytical framework that combines Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), CatBoost machine learning, and SHAP-based explainability to bridge theory-driven modeling with data-driven prediction. Using provincial panel data from China spanning 2011–2023, CFA is first employed to construct and validate four latent RIS dimensions. These latent constructs are then used as inputs in a CatBoost model to predict regional patent outputs, followed by SHAP analysis to quantify the marginal and interactive contributions of each dimension. Results: The CFA results confirm the reliability and validity of the four latent dimensions, establishing a robust structural foundation for the RIS. The CatBoost model achieves high predictive accuracy (log-transformed = 0.975, RMSE = 0.206), substantially outperforming traditional linear benchmarks. SHAP analysis indicates that the Firm dimension is the primary driver of innovation output, while Knowledge, Government, and Economy dimensions exhibit context-dependent moderating effects characterized by diminishing returns, threshold effects, and nonlinear synergies. Conclusions: By integrating latent-variable modeling with interpretable machine learning, this study develops a “CFA-CatBoost-SHAP” closed-loop paradigm for transparent and high-precision analysis of innovation mechanisms. This approach advances RIS theory by empirically validating its multidimensional structure, enriches the methodological toolkit for innovation research, and provides actionable insights for the design of targeted R&D and innovation policies.

1. Introduction

Innovation is widely recognized as a fundamental driver of regional competitiveness and economic growth. In the context of the knowledge economy and digital transformation, understanding how innovation outputs are generated at the regional level has become a core issue in innovation economics and regional development studies [1]. The Regional Innovation System (RIS) theory provides a systemic analytical framework for this purpose, emphasizing that innovation emerges from the interactive dynamics among firms, knowledge institutions, government, and the regional economy, rather than from isolated actors [2]. These four dimensions jointly shape regional innovation capacity through interlinked processes of knowledge creation, diffusion, institutional support, and market absorption.

Although RIS theory offers strong conceptual explanatory power, its multidimensional structure has not been sufficiently validated using integrated empirical frameworks. Existing studies largely rely on linear econometric models [3,4], which are limited in their ability to capture the nonlinear, threshold, and interaction effects that characterize real-world innovation systems. In practice, the marginal effects of firm R&D, knowledge supply, and government intervention often depend on regional economic conditions and institutional contexts, exhibiting pronounced nonlinearities and conditional dynamics [5,6]. This mismatch between theoretical complexity and empirical methods constrains a deeper understanding of RIS mechanisms.

Another key limitation concerns the measurement of RIS dimensions. Most studies directly use observable indicators—such as R&D expenditure, number of universities, or industrial output—to proxy innovation elements [7], without explicitly modeling the latent structures implied by RIS theory. While recent studies have introduced Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to explore mediating mechanisms among government support, knowledge supply, and firm innovation [8], these approaches remain largely static and exhibit limited predictive power and weak capacity for identifying nonlinear mechanisms.

Meanwhile, advances in machine learning—particularly gradient boosting tree-based models such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—have demonstrated strong performance in modeling nonlinear and high-dimensional relationships in innovation research [9,10]. However, these models are typically theory-agnostic and operate as “black boxes”, offering limited insight into the underlying innovation mechanisms. The recent development of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), especially the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) method based on Shapley values [11], enables the decomposition of model predictions into interpretable feature contributions, thereby creating new opportunities to bridge data-driven prediction with theoretical explanation.

Despite these advances, an integrated framework that simultaneously (i) validates the latent RIS structure, (ii) captures nonlinear innovation mechanisms, and (iii) provides interpretable policy-relevant insights remains lacking. In particular, few studies explicitly construct and validate the four core RIS dimensions—Firm, Knowledge, Government, and Economy—as latent variables and embed them within an interpretable machine learning framework.

To address this gap, this study proposes an integrated “CFA-CatBoost-SHAP” framework that systematically links RIS theory with data-driven prediction and mechanism interpretation. Specifically, CFA is first used to construct and validate the four latent RIS dimensions using provincial panel data from China spanning 2011–2023. These validated latent variables are then employed as inputs to a CatBoost model for rolling prediction of regional patent outputs. Finally, SHAP analysis is conducted to quantify the marginal contributions and nonlinear interaction effects of each RIS dimension.

Guided by this framework, the study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1: Can the four theoretical dimensions of RIS (Firm, Knowledge, Government, and Economy) be empirically validated as stable latent structures using CFA?

- RQ2: To what extent can these validated latent dimensions accurately predict regional patent outputs using nonlinear machine learning?

- RQ3: What are the relative contributions and interaction mechanisms of the four RIS dimensions as revealed by SHAP-based interpretability analysis?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews RIS theory, innovation output prediction models, and XAI applications. Section 3 describes the data, CFA modeling, CatBoost training, and SHAP analysis. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 discusses mechanism interpretation, regional heterogeneity, and policy implications. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

2.1. Evolution of RIS Theory and Its Four-Dimensional Mechanisms

Since its emergence in the 1990s, the RIS framework has been widely adopted to explain regional disparities in innovation performance by emphasizing that innovation is a systemic, interactive, and context-dependent process rather than the outcome of isolated firm activities [12]. From this perspective, innovation is understood as a collective and evolutionary process embedded in region-specific institutional arrangements, knowledge infrastructures, and economic environments, in which heterogeneous actors interact and co-evolve [13]. As a result, innovation systems cannot be adequately characterized by single-factor explanations, but require a multidimensional structural decomposition. Building on this systemic understanding, a substantial body of literature has converged on a four-dimensional structure of the RIS, comprising Firm, Knowledge, Government, and Economy [14,15].

Within this structure, the Firm dimension represents the micro-level innovation actor, capturing firms’ R&D investment behavior, absorptive capacity, and collaborative innovation activities [16,17]. Its core function lies in transforming knowledge inputs into commercially viable innovation outputs. Empirical evidence further indicates that firm-level innovation performance is highly contingent on external knowledge coupling and often exhibits nonlinear spillover and learning effects [18]. The Knowledge dimension corresponds to the regional knowledge infrastructure, including universities, public research institutes, and innovation intermediaries. It reflects the supply-side conditions of knowledge creation, diffusion, and recombination, which directly shape the accessibility and efficiency of technological opportunities within a region [13], and thus provides the cognitive and technological foundations for firm-level innovation. The Government dimension characterizes the institutional and policy environment of the RIS. Through fiscal incentives, regulatory arrangements, and strategic coordination, governments influence both the direction and intensity of innovation activities [19]. Importantly, existing studies suggest that policy effects are frequently nonlinear and context-dependent, implying that government intervention does not necessarily translate into proportional innovation outputs under all conditions. The Economy dimension captures the macro-level economic foundation of regional innovation, including market size, industrial structure, openness, infrastructure, and digital development [20,21]. This dimension shapes the demand-side conditions and resource-carrying capacity of innovation systems, thereby affecting the long-term sustainability and scalability of innovation activities.

From a theoretical standpoint, these four dimensions do not operate as interdependent factor groups, but jointly constitute a structurally interdependent and dynamically coupled system. Their influences on innovation output are therefore expected to be transmitted through latent mechanisms, involving cross-dimensional complementarities, threshold effects, and nonlinear feedback loops. However, most existing empirical studies still rely on direct observable proxies and impose linear specifications, which limits their ability to uncover the underlying latent structure and complex interaction mechanisms implied by RIS theory.

2.2. Development of Innovation Output Prediction Models and Methodological Evolution

Forecasting and explaining innovation outputs have long been central concerns in innovation economics and regional policy research. Traditional studies have predominantly relied on econometric approaches—such as Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), fixed-effects panel models, and penalized regressions, including Ridge or Lasso regression—to estimate input–output relationships and marginal effects [22,23]. While these methods provide strong theoretical interpretability and clear causal inference under classical assumptions, their strict reliance on linear functional forms substantially constrains their ability to capture the nonlinear interactions, heterogeneous effects, and cross-dimensional synergies inherent in RIS.

This methodological limitation has directly motivated a progressive shift toward nonlinear machine learning and XAI approaches. Consequently, recent research has increasingly transitioned from purely econometric modeling to data-driven machine learning frameworks for innovation output prediction. For example, Zhao et al. [24] employed stacking ensemble models to analyze the relationship between provincial digital economy indicators and firm-level patent outputs in China, finding significant spatial heterogeneity and nonlinear coupling between regional digital infrastructure and firm innovation performance. Espinosa-Blasco et al. [25] constructed a predictive model for innovation subsidy allocation using a combination of genetic algorithms and Random Forest, based on 1252 R&D&I subsidy cases from 807 firms in the Valencia region of Spain, systematically identifying key factors influencing firms’ subsidy amounts. Although these studies demonstrate the superior predictive performance of machine learning approaches, they remain largely performance-oriented and provide limited insight into the structural mechanisms through which latent RIS dimensions jointly shape innovation outputs at a theoretical level.

2.3. Explainable Artificial Intelligence and RIS Mechanism Identification

With the expanding application of machine learning in innovation studies, the “black-box” nature of many algorithms has increasingly constrained their theoretical interpretability and policy relevance. Although such models often exhibit strong predictive performance, their opacity limits the identification of causal mechanisms underlying innovation dynamics. XAI has therefore emerged as a critical methodological paradigm aimed at unveiling the internal decision logic of complex models and enhancing their scientific interpretability. Among existing XAI techniques, SHAP, grounded in cooperative game theory, quantifies each feature’s marginal contribution to model outputs through Shapley values [11]. Beyond identifying global feature importance, SHAP further captures heterogeneous, nonlinear, and interaction effects at the local (sample-specific) level.

Within the context of RIS research, SHAP provides a particularly suitable analytical tool for translating theoretically defined latent dimensions into empirically interpretable mechanisms. At the global level, SHAP enables a systematic comparison of the relative contributions of Firm, Knowledge, Government, and Economy to regional innovation outputs such as patenting. At the local level, it reveals nonlinear interaction patterns across dimensions that are difficult to detect using traditional linear econometric frameworks. For instance, strong firm–knowledge coupling may generate disproportionately large innovation gains, whereas weak or unbalanced configurations often yield limited marginal effects. Recent studies further demonstrate that SHAP-based interpretation facilitates the empirical reconstruction of theoretical mechanisms by mapping abstract constructs onto quantifiable marginal effects [26].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

To systematically capture the mechanisms through which the four RIS dimensions affect innovation outputs, this study constructs a high-quality panel dataset covering 31 provinces in mainland China (excluding Taiwan, Macau, and Hong Kong) from 2011 to 2023. Data are primarily sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics and publicly available statistical yearbooks [27], and key indicators are selected based on prior studies to ensure temporal and spatial continuity and comparability. To latentize the RIS theoretical dimensions, ten core indicators representing the four dimensions—Firm, Knowledge, Gov, and Econ—are chosen. Each indicator directly corresponds to theoretical assumptions and innovation mechanisms:

- Firm dimension: Measured by full-time equivalent R&D personnel, R&D expenditure, and the number of R&D projects, capturing firms’ innovation capacity and R&D intensity. Firm R&D activities not only directly drive patent generation but also influence knowledge diffusion through technology accumulation and collaborative networks, reflecting the micro-level driving role of the latent variable.

- Knowledge dimension: Measured by the number of universities and full-time faculty, reflecting regional knowledge supply capacity and research infrastructure. These indicators reflect the ability to create knowledge and cultivate talent, indirectly enhancing firm innovation performance and supporting patent output.

- Gov dimension: Measured by local government expenditures on science & technology and education, quantifying policy incentives and resource allocation intensity. Government policies promote collaborative innovation between firms and knowledge institutions by providing funding support and optimizing institutions.

- Econ dimension: Measured by per capita GDP and the value added of the secondary and tertiary industries, reflecting the regional economic base and industrial structure. These indicators provide market absorption capacity and industrial support for innovation activities, forming a positive feedback loop between innovation and economic development.

Due to limitations in domestic enterprise statistics, Firm dimension indicators are primarily drawn from industrial enterprises above a designated size. These enterprises dominate innovation inputs and patent outputs, effectively reflecting overall regional innovation capacity while reducing noise from data fluctuations in small and medium-sized enterprises, thereby enhancing the stability of latent-variable construction and machine learning prediction models.

Given that firm R&D investment typically exhibits a lag of approximately 1 year in patent outputs [28], this study adopts a strategy in which features in year T predict patent applications in year , maintaining temporal correspondence between innovation inputs and outputs. Furthermore, given significant regional heterogeneity in economic development, research capacity, and policy environments, provinces are incorporated into the model as dummy variables to control for regional fixed effects, ensuring robust estimation of the impact of the four RIS dimensions. To ensure continuity and cross-regional comparability of the panel data, missing values are imputed using linear interpolation. Numerical features are standardized to eliminate scale differences that could affect latent-variable construction and machine learning model performance. In contrast, categorical features are encoded to meet algorithmic requirements, such as those of CatBoost. These preprocessing steps enhance numerical stability and ensure the reliability of latent variable construction, nonlinear relationship capture, and SHAP interpretability analysis. Ultimately, this study constructs a high-quality panel dataset spanning 31 provinces and 13 years, systematically capturing the dynamic characteristics of the four RIS dimensions and providing a solid data foundation for latent-variable modeling, CatBoost prediction, and SHAP-based mechanism interpretation. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of all indicators.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and variable mapping of the four latent dimensions of the RIS.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To validate the theoretical structure of the four RIS dimensions, this study employs CFA, a theory-driven approach that specifies the latent structure a priori and allows direct empirical testing of hypothesized measurement models. Let denote the vector of observed indicators and the vector of latent variables. In CFA, each observed variable is restricted to load solely on its theoretically assigned latent factor, such that

where all cross-loadings on non-target factors are fixed to zero to ensure construct distinctiveness.

Unlike Exploratory Factor Analysis, which freely estimates all loadings, CFA imposes the structural assumption that measurement errors are mutually uncorrelated:

while permitting latent constructs to correlate through an unrestricted covariance matrix:

Under these conditions, the model-implied covariance matrix is expressed as

where denotes the diagonal matrix of measurement error variances.

Parameter estimation proceeds by minimizing the difference between the sample covariance matrix S and the model-implied covariance matrix , thereby ensuring that the estimated model reproduces the empirical covariance structure as closely as possible. Given the potential non-normality, regional heterogeneity, and varying sample sizes in the provincial panel data, this study adopts the Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) estimator, which provides robust and stable parameter estimates without relying on multivariate normality. Model fit is assessed using , CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and AGFI. A factor loading threshold of is applied to ensure meaningful linkage between indicators and latent constructs. The validated latent variables serve as high-quality inputs for subsequent CatBoost prediction and SHAP-based mechanism analysis.

3.3. CatBoost Modeling

To achieve high-precision prediction of regional patent outputs based on the four validated RIS latent variables, this study employs the CatBoost algorithm, a GBDT method with strong capability in modeling nonlinear relationships and high-order interactions. CatBoost iteratively fits weak learners to the negative gradients of a predefined loss function. Let denote the observed patent output and the prediction at iteration t. The objective function is defined as:

The model is updated by:

where is the t-th decision tree and is the learning rate. Compared with conventional GBDT, CatBoost introduces ordered boosting and symmetric tree structures, which effectively reduce prediction shift and overfitting, ensuring stable estimates of nonlinear effects among RIS dimensions.

Given the large regional disparities in patent counts, a logarithmic transformation is applied to stabilize variance and suppress outlier effects:

This transformation improves residual distribution and facilitates the interpretation of marginal effects. To simulate real-world forecasting scenarios and mitigate temporal shocks, a rolling forecast strategy is adopted. At each time t, the model is trained using data from years and predicts patent outputs for year :

The minimum training window is set to five years to ensure sufficient learning of nonlinear structures. Historical patent counts are excluded to avoid bias from time-series autocorrelation, allowing the model to identify the independent nonlinear effects of RIS latent variables.

Model performance is evaluated using rolling averages of standard metrics:

where includes MSE, RMSE, MAE, , and MAPE. This rolling prediction framework ensures robust generalization while accurately capturing the nonlinear contributions and interaction mechanisms among the four RIS latent dimensions, providing a reliable basis for subsequent SHAP-based interpretability analysis.

3.4. SHAP Explainable Analysis

To uncover the mechanisms through which the four RIS latent variables affect patent outputs, this study employs SHAP to decompose and interpret the predictions of the CatBoost model. SHAP, grounded in cooperative game theory, quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature—here, the RIS latent variables constructed via CFA—to the model’s prediction. Let the predictive model be ; the predicted value can be expressed as the sum of feature contributions:

where is the baseline prediction (sample mean), and represents the contribution of the j-th latent variable to the prediction. According to Shapley theory, is computed as:

This formula measures the average marginal effect of a feature across all possible subsets, ensuring symmetry, fairness, and additivity, thereby providing mathematically rigorous interpretability. To improve computational efficiency, this study employs the TreeExplainer algorithm, which efficiently approximates Shapley values in tree-based models while maintaining global consistency and local accuracy. The algorithm reduces computational complexity from exponential to polynomial, making SHAP analysis feasible for long-panel data in CatBoost models.

The SHAP analysis in this study involves three layers of interpretability:

- Global Interpretation: By calculating the mean absolute SHAP value for each latent variable, the overall importance of each dimension in predicting patent outputs is assessed, providing a ranking basis for subsequent analysis.

- Local Interpretation: At the level of individual samples (province or year), Force Plots or Waterfall Plots visualize the positive and negative contributions of latent variables, quantitatively capturing their effects under specific conditions.

- Interaction and Nonlinearity Analysis: SHAP Dependence Plots are used to visualize interactions and nonlinear relationships among latent variables, revealing complex coupling mechanisms that inform both policy design and theoretical interpretation.

It is noteworthy that SHAP analysis is integrated into the closed-loop design of CFA-derived latent variables and CatBoost outputs. This design ensures that the model not only achieves high-precision predictions but also quantifies the marginal contributions and interaction effects of latent variables, thereby realizing a natural integration of theory, methodology, and empirical evidence.

4. Results

4.1. CFA Results and Evaluation of Latent Variable Structure

To evaluate the validity and reliability of the four RIS latent dimensions—Firm, Knowledge, Gov, and Econ—a CFA was conducted. As reported in Table 2, the model demonstrates strong overall goodness-of-fit. Key fit indices, including CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.993, and AGFI = 0.991, all exceed commonly accepted thresholds, jointly confirming the adequacy of the latent RIS structure. Although RMSEA = 0.092 slightly exceeds the conventional cutoff of 0.08, this deviation is acceptable given the model’s complexity and the high intercorrelations among latent variables. Similarly, the relative chi-square ( = 4.435) indicates an acceptable global model fit, further supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Goodness-of-fit statistics for the CFA model of the RIS.

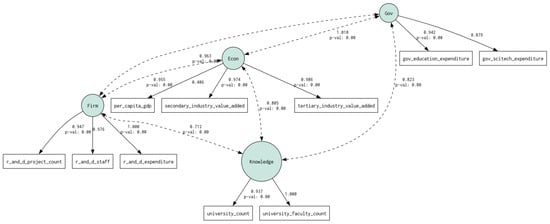

Turning to the factor loadings, all standardized loadings of observed indicators on their corresponding latent constructs are statistically significant (p < 0.001) and exhibit substantial magnitudes, indicating strong convergent validity and internal consistency (Figure 1). Specifically, the Firm dimension shows near-unit loadings, suggesting that it effectively captures enterprise-level innovation capability. The Knowledge dimension also exhibits consistently high loadings, confirming the stability of universities and research institutions as measures of regional knowledge creation. The Gov dimension demonstrates significant loadings, validating the pivotal role of policy and fiscal support in shaping innovation environments. Within the Econ dimension, industrial value added has a higher loading than per capita GDP, implying that regional industrial vitality is more sensitive to innovation outputs than aggregate income level.

Figure 1.

CFA model results of the RIS.

Examining the inter-latent correlations, all associations are positive and statistically significant, highlighting the interconnected nature of the four RIS dimensions. Notably, the correlations between Firm–Gov (r = 0.963), Firm–Econ (r = 0.955), and Knowledge–Gov (r = 0.823) are particularly strong, aligning closely with the synergistic interaction mechanisms proposed in RIS theory. In addition, all latent variances are significant (p < 0.001), supporting adequate discriminant validity among the dimensions.

4.2. Machine Learning Prediction Performance Driven by CFA-Derived Latent Variables

To evaluate the predictive effectiveness of the four RIS latent dimensions extracted via CFA in explaining patent outputs, this study compares multiple machine learning models within a rolling forecasting framework. The models include Decision Tree, Random Forest, LightGBM, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, and CatBoost. All models utilize the CFA-derived latent variables as input features and are trained and tested under identical temporal windows to ensure comparability. Given the substantial variation in patent output across Chinese provinces—where coastal regions report tens of thousands of annual applications while inland provinces may record only a few hundred—direct modeling with raw values would render the models overly sensitive to outliers and induce heteroscedasticity. To mitigate this issue, the dependent variable (patent output) was transformed logarithmically.

Table 3 presents the overall performance of each model under the rolling forecast design. The single Decision Tree yielded the weakest results (MSE = 0.121, = 0.931), indicating its limited capacity to capture nonlinear and interactive effects among latent variables. The Random Forest improved predictive accuracy through its ensemble mechanism ( = 0.960). LightGBM further reduced the RMSE (0.252) and increased (0.964), demonstrating the advantages of gradient boosting in modeling complex nonlinear relationships. Gradient Boosting and XGBoost achieved similar performance levels ( = 0.970–0.971, RMSE = 0.225–0.224). However, CatBoost outperformed all other models across all evaluation metrics ( = 0.975, RMSE = 0.206, MAPE = 1.510%), underscoring its superior ability to handle CFA-derived latent features and capture intricate nonlinear and interaction effects.

Table 3.

Predictive performance of machine learning models based on CFA-derived RIS latent variables.

These findings validate the effectiveness of integrating CFA-based latent variable construction with CatBoost modeling. The CFA stage structurally aggregates enterprise, knowledge, government, and economic characteristics through factor loadings, generating high-quality, theory-grounded inputs that enhance model interpretability. Meanwhile, CatBoost—through its ordered boosting mechanism and symmetric tree structure—efficiently captures nonlinear interactions among latent variables while remaining robust to outliers. Building on this high-accuracy predictive foundation, the subsequent SHAP explainability analysis will quantify the marginal contributions of each latent variable to patent output, reveal nonlinear threshold effects and cross-dimensional interaction mechanisms, and thus establish a theory–method–empirics integration loop that offers actionable insights for regional innovation policy design.

4.3. Validation of Nonlinear Modeling Advantages: Comparison Between CatBoost and Conventional Linear Econometric Models

To evaluate the predictive advantage of CatBoost over conventional linear econometric approaches, this study compares its performance with four widely used linear models: OLS, Ridge Regression, Generalized Least Squares (GLS), and Panel OLS. All models are estimated using the same four CFA-derived RIS latent dimensions (Firm, Knowledge, Gov, Econ) as inputs, and predictions are generated within an identical rolling forecast framework to ensure comparability and robustness. The predictive performance metrics are summarized in Table 4. The linear models achieve MSE values ranging from 0.386 to 0.388, with 0.780, suggesting that they primarily capture the general linear trends between the RIS dimensions and regional patent outputs. Incorporating regional fixed effects into Panel OLS does not improve performance; on the contrary, it performs worse (MSE = 0.542, = 0.697), highlighting its limited adaptability to intertemporal structural changes. These results indicate that linear specifications may fail to fully account for the complex and potentially nonlinear interactions among RIS components. In contrast, CatBoost achieves a substantial improvement in predictive accuracy, with MSE = 0.043, = 0.975, and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) = 1.510%. This corresponds to an approximate 89% reduction in prediction error relative to OLS. The results demonstrate that CatBoost effectively captures intricate nonlinear interactions and hierarchical dependencies among the RIS dimensions, which linear models inherently overlook. These findings further suggest that regional innovation output is influenced by the nonlinear coupling mechanisms of multiple RIS dimensions rather than by simple additive linear effects.

Table 4.

Comparative predictive performance between CatBoost and conventional linear econometric models.

4.4. SHAP Explainability of Nonlinear and Interaction Effects

Although the CatBoost model achieves high predictive accuracy, its “black-box” nature obscures how the RIS latent dimensions drive regional innovation outputs. To address this, we apply SHAP, grounded in cooperative game theory, to decompose model predictions at both global and local levels, thereby providing interpretable insights into the contributions and interactions of latent variables.

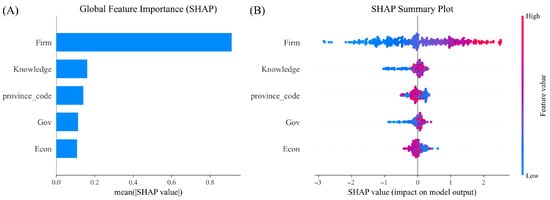

4.4.1. Global Contribution: Systemic Dominance of the Firm Dimension and Hierarchical Moderation Mechanisms

Figure 2A reports the mean absolute SHAP values () for the four RIS latent dimensions, quantifying their relative contributions to patent output prediction. The Firm dimension exhibits the highest (0.913), followed by Knowledge (0.162), province_code (0.141), Gov (0.114), and Econ (0.108). This indicates that enterprise-level innovation is the primary driver of regional patent outputs, while Knowledge and Gov primarily act as modulators whose contributions vary across provinces. In contrast, Econ exerts minor but threshold-like effects, providing background support once Firm and Knowledge effects are accounted for.

Figure 2.

Global SHAP contribution and univariate effect distribution of RIS latent variables. (A) SHAP bar plot; (B) SHAP summary plot.

To further understand how each dimension influences predicted outputs across their observed ranges, Figure 2B visualizes the univariate SHAP value distributions. This plot reveals that Firm exhibits a positive monotonic relationship with predicted patent outputs. Meanwhile, the SHAP distributions of Knowledge and Gov are more dispersed, reflecting substantial regional heterogeneity. Econ’s limited magnitude suggests its influence is more contextual than direct. The relatively high SHAP value of province_code further confirms that innovation dynamics are spatially stratified and path-dependent.

4.4.2. SHAP Dependence Analysis: Nonlinear Marginal Effects and Interaction Structures of Latent Variables

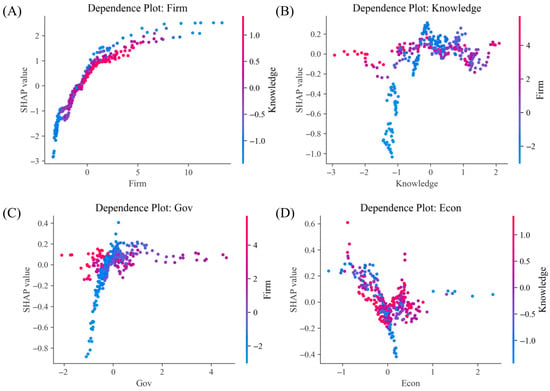

Figure 3 presents SHAP dependence plots for the four core RIS dimensions, providing a detailed view of nonlinearities and cross-dimensional interactions. Key insights are summarized as follows:

Figure 3.

Nonlinear marginal effects and interaction mechanisms among RIS latent variables. (A) Firm SHAP dependence plot with Knowledge interaction; (B) Knowledge SHAP dependence plot with Firm interaction; (C) Gov SHAP dependence plot with Firm interaction; (D) Econ SHAP dependence plot with Knowledge interaction.

- Firm exhibits a saturated growth pattern: SHAP values increase with Firm up to approximately +2 and then plateau, indicating diminishing marginal returns. Interaction analysis shows that Knowledge moderates Firm’s effect, such that in high-knowledge environments, systemic collaboration partially substitutes for the direct contribution of Firm.

- Knowledge demonstrates a threshold effect: low Knowledge levels correspond to negative SHAP values, reflecting a “knowledge trap”, whereas moderate to high levels contribute positively with diminishing increments. Interactions with Firm suggest that strong firms can alleviate low-Knowledge constraints, while excessive Knowledge may reduce marginal gains due to redundancy in highly developed contexts.

- Gov shows a threshold transition within the range . Below zero, increases in Gov sharply enhance SHAP values, indicating compensatory policy effects; above this threshold, the effect stabilizes. Interaction with Firm reveals a substitution mechanism, where stronger firms rely less on government support, highlighting a dynamic balance between institutional guidance and firm autonomy.

- Econ displays asymmetric threshold effects: moderate economic conditions may suppress innovation outputs (negative SHAP), whereas lower or higher values enhance performance. Knowledge further amplifies Econ’s positive contributions, forming a synergistic coupling mechanism within the RIS.

These patterns collectively reveal a network of nonlinear, substitutive, and synergistic interactions among the latent dimensions, underscoring the multi-level and adaptive dynamics of regional innovation systems.

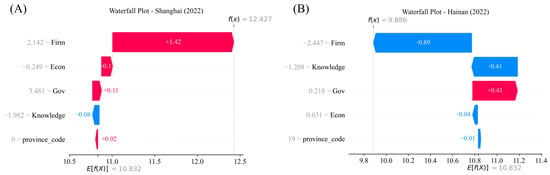

4.4.3. Waterfall Analysis: Mechanism Heterogeneity Across Typical Regions

To illustrate regional heterogeneity in RIS mechanisms, Shanghai and Hainan are selected as representative high- and low-innovation regions. SHAP Waterfall plots are used to decompose the contributions of RIS latent dimensions to patent output in 2022.

- Shanghai: As shown in Figure 4A, Shanghai exhibits a firm-dominated pattern. The Firm dimension contributes most positively, confirming that enterprise innovation serves as the primary driver. Econ and Gov exert moderate positive effects, functioning more as amplifiers than as core drivers. Knowledge contributes weakly negative effects, suggesting limited marginal impact within a mature innovation environment. This pattern reflects a stable, firm-centered RIS structure supported by favorable economic and institutional conditions.

Figure 4. SHAP waterfall analysis of regional mechanisms: Shanghai vs. Hainan. (A) Shanghai (2022) SHAP waterfall plot; (B) Hainan (2022) SHAP waterfall plot.

Figure 4. SHAP waterfall analysis of regional mechanisms: Shanghai vs. Hainan. (A) Shanghai (2022) SHAP waterfall plot; (B) Hainan (2022) SHAP waterfall plot. - Hainan: Figure 4B reveals a contrasting pattern for Hainan. Both Firm and Knowledge contribute negatively, indicating insufficient endogenous capacity and limited knowledge support. Gov contributes positively, highlighting the compensatory role of policy in a low-innovation context. Nevertheless, overall output remains constrained, demonstrating that government intervention alone cannot fully offset structural weaknesses in endogenous innovation.

These regional patterns illustrate the heterogeneous mechanisms underpinning RIS performance and align with the broader SHAP findings. In particular, they demonstrate how local conditions shape the relative contributions of Firm, Knowledge, Gov, and Econ, providing a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms that distinguish high- and low-performing regions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Nonlinear Structural Mechanisms of RIS

This study provides a mechanism-oriented interpretation of RIS by integrating CFA-derived latent constructs with CatBoost prediction and SHAP explainability. Consistent with complex adaptive systems theory, innovation output emerges from the dynamic interactions and nonlinear coupling of Firm, Knowledge, Gov, and Econ, rather than from linearly additive effects. Across regions, the Firm dimension constitutes the primary driving force, whereas Knowledge and Gov predominantly act as conditional modulators, and Econ functions as a contextual amplifier. Importantly, the functional roles of these dimensions are context- and phase-dependent rather than fixed. For instance, the Knowledge dimension exhibits a capability-matching mechanism: innovation is constrained when knowledge inputs are insufficient relative to firms’ absorptive capacity, while excessive knowledge supply without corresponding firm capability generates diminishing returns. This underscores the principle that knowledge becomes productive only when aligned with firms’ capacity to transform it into innovation outputs. Government intervention operates through a threshold-dependent and substitutive mechanism. In early stages of regional development, policy support compensates for weak firm capabilities, promoting innovation where endogenous capacity is limited. As firms strengthen over time, the marginal effect of government support diminishes and may even crowd out market-driven innovation. This demonstrates that Firm–Gov interactions are dynamically substitutive, reflecting adaptive balancing between institutional guidance and firm autonomy rather than permanent complementarity. The Econ dimension does not exert a uniform positive influence; instead, it acts as a nonlinear amplifier that enhances firm-driven innovation only when specific economic thresholds are exceeded. This indicates that the regional economic environment primarily modulates the efficiency and scalability of innovation processes rather than functioning as an independent innovation engine. These mechanisms collectively highlight that the efficiency and adaptability of regional innovation systems do not result from the expansion of any single dimension in isolation. Instead, they emerge from the dynamic coordination and phase alignment among Firm, Knowledge, Gov, and Econ.

5.2. Regional Heterogeneity, Contextual Dependence, and Evolutionary Pathways

Beyond the general mechanisms, we observe strong regional heterogeneity in RIS configurations, reflecting different evolutionary stages. In mature regions, innovation systems tend to exhibit firm-centered self-organization, with diminishing reliance on direct government intervention. In contrast, less-developed regions depend more heavily on government compensation, particularly where firm capabilities and knowledge infrastructure remain weak. These observations suggest that China’s provincial RIS does not converge toward a single equilibrium; rather, multiple coexisting evolutionary pathways emerge, shaped by both endogenous capacities and exogenous institutional conditions. Crucially, these differentiated patterns are not solely determined by technical inputs. Evidence from Sánchez (2025) indicates that technology perception and adoption are strongly conditioned by organizational culture, sectoral structure, and the broader economic environment [29]. This insight complements our findings by explaining why provinces with similar levels of RIS inputs may nonetheless exhibit divergent innovation outcomes. In other words, innovation performance reflects not only the accumulation of knowledge and resources but also context-dependent assimilation processes, including institutional alignment, sectoral fit, and absorptive capacity. This perspective clarifies why identical policy instruments can generate heterogeneous effects across regions. From an evolutionary standpoint, regional RIS development can be conceptualized as progressing along three typical stages, which may coexist spatially rather than sequentially: (i) Policy-driven systems, dominated by external compensation mechanisms that offset weak endogenous capabilities. (ii) Synergistic expansion systems, where innovation is jointly driven by firms and knowledge institutions, reflecting balanced internal and external resource mobilization. (iii) Market-led systems, in which firm self-organization becomes the primary driver, supported but not dictated by policy or institutional frameworks.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the contributions of this study in integrating CFA, CatBoost, and SHAP to elucidate the latent mechanisms of regional innovation systems, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study relies on provincial-level aggregated data, which may obscure intra-regional heterogeneity and micro-level firm dynamics. Consequently, some fine-grained mechanisms, such as firm-level absorptive capacity or city-level knowledge spillovers, might be underrepresented. Future research could leverage firm-level or city-level panel data to refine mechanism identification and capture local innovation processes more accurately. Second, while the combination of CatBoost and SHAP reveals robust nonlinear associations, machine learning inference remains inherently non-causal. The identified patterns should therefore be interpreted as structural regularities rather than definitive causal relationships. Subsequent studies could incorporate causal inference approaches, such as instrumental variables, difference-in-differences designs, or structural causal models, to enhance the causal interpretability of the observed mechanisms. Third, potential endogeneity and dynamic interdependencies among RIS latent dimensions cannot be fully ruled out. For instance, firm innovation, knowledge generation, and policy support are likely to mutually reinforce each other over time. Although CFA reduces measurement error and SHAP clarifies functional contributions, disentangling feedback loops remains challenging. Finally, this study focuses primarily on the Chinese provincial context, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other institutional or regional settings. Despite these limitations, the proposed CFA-CatBoost-SHAP framework provides a replicable, theory-guided pathway for linking latent theoretical constructs with nonlinear, interpretable predictive models. It lays a methodological foundation for future computational studies of regional innovation systems, offering both analytical rigor and practical relevance for understanding complex, multi-dimensional innovation processes.

6. Conclusions

This study develops and implements an integrated CFA-CatBoost-SHAP framework to examine RISs, offering a coherent analytical pathway from latent structural identification to the interpretation of nonlinear mechanisms. By combining CFA for theoretically grounded latent constructs, gradient-boosted machine learning for high-accuracy prediction, and SHAP-based explainability for transparent decomposition of model outputs, the framework bridges theory-driven constructs with data-driven insights, effectively addressing the complexity inherent in multi-dimensional and context-dependent innovation systems. Unlike conventional linear econometric approaches, this framework simultaneously captures latent multidimensional structures, nonlinear effects, and cross-dimensional interactions, while maintaining interpretability. This dual capability—improving predictive performance and translating “black-box” outputs into mechanism-oriented explanations—constitutes its core methodological contribution. By uncovering threshold effects, substitution relationships, and synergistic interactions among RIS dimensions, the framework provides empirical evidence for the adaptive, multi-level dynamics of regional innovation systems. From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the necessity of stage-sensitive and context-aware innovation governance. Early-stage regions derive the greatest benefit from institutional support and capacity building, intermediate regions rely on coordinated interactions between firms and knowledge infrastructures, and mature regions are primarily driven by market-oriented mechanisms within stable innovation environments. Collectively, these insights underscore that effective innovation policy cannot follow a uniform logic; instead, it must be differentiated, adaptive, and aligned with both regional development stage and systemic configuration.

Author Contributions

M.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. T.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Y.L.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. S.X.: Conceptualization, Software, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Talent Research Startup Foundation of Hainan Normal University (Nos. HSZK-KYQD-202518 and HSZK-KYQD-202430), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 825QN308), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62562030).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5 Mini) in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mei Yang is employed by Anhui Jianyang Information Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kraus, S.; McDowell, W.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E.; Rodríguez-García, M. The role of innovation and knowledge for entrepreneurship and regional development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2021, 33, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhao, K. Navigating the innovation policy dilemma: How subnational governments balance expenditure competition pressures and long-term innovation goals. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Bing, Y. Strategic leadership, environmental optimisation, and regional innovation performance with the regional innovation system coupling synergy degree: Evidence from China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.J.; Kim, B.H. Analyzing the Dynamic Efficiency and Critical Factors of the Regional Innovation System: A Case Study of Korea. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2025, 48, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C. Government R&D investment, knowledge accumulation, and regional innovation capability: Evidence of a threshold effect model from China. Complexity 2021, 2021, 8963237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, P. The Impact and Effectiveness of Innovation Policy: Evidence from Middle-Income Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stundziene, A.; Pilinkiene, V.; Vilkas, M.; Grybauskas, A.; Lukauskas, M. The challenge of measuring innovation types: A systematic literature review. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Johar, M.G.M. Government support, employee structure and organisational digital innovation: Evidence from China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Ni, H. Prediction of patent grant and interpreting the key determinants: An application of interpretable machine learning approach. Scientometrics 2023, 128, 4933–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, P.; Liu, X. Patent lifetime prediction using LightGBM with a customized loss. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, E.; Kilintzis, P.; Komninos, N.; Anastasiou, A.; Martinidis, G. Assessment of smart technologies in regional innovation systems: A novel methodological approach to the regionalisation of national indicators. Systems 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeranattapong, T.; Pickernell, D.; Simms, C. Systematic literature review paper: The regional innovation system-university-science park nexus. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 2017–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, C.; Ruggiero, N. How do dimensions of institutional quality improve Italian regional innovation system efficiency? The Knowledge production function using SFA. J. Evol. Econ. 2022, 32, 591–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Cui, X.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Firdaus, R.R. Impact of industry-university-research collaboration and convergence on economic development: Evidence from chengdu-chongqing economic circle in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, L.S.; Soares Echeveste, M.E.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Gularte, A.C. Open innovation in regional innovation systems: Assessment of critical success factors for implementation in SMEs. J. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 10, 1597–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Vicente-Oliva, S.; Pérez-Pérez, M. The relationship between R&D, the absorptive capacity of knowledge, human resource flexibility and innovation: Mediator effects on industrial firms. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, S.; Zhou, H.; Wei, X. Nonlinear impact of the interaction between internal knowledge and knowledge spillover on patent quality: Evidence from China’s provincial high-tech industry. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z. Investigating the Impact of Innovation Policies and Innovation Environment on Regional Innovation Capacity in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, K.; Xu, H. Multinational Corporations and Technological Innovation Development of China’s High-Tech Industries: A Heterogeneity-Based Threshold Effect Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Song, P.; Gao, C.; Yang, D. Economic openness, innovation and economic growth: Nonlinear relationships based on policy support. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, D.; Jurowetzki, R. Modeling for Inferential Statisticians-A Hands-On Application in the Prediction of Breakthrough Patents. In Financial Econometrics: Bayesian Analysis, Quantum Uncertainty, and Related Topics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 427, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Rubilar-Torrealba, R.; Chahuán-Jiménez, K.; de la Fuente-Mella, H. Analysis of the growth in the number of patents granted and its effect over the level of growth of the countries: An econometric estimation of the mixed model approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Wang, P. Predictive Framework for Regional Patent Output Using Digital Economic Indicators: A Stacked Machine Learning and Geospatial Ensemble to Address R&D Disparities. Analytics 2025, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Blasco, M.; Penagos-Londoño, G.I.; Ruiz-Moreno, F.; Vilaplana-Aparicio, M.J. New Insights on the Allocation of Innovation Subsidies: A Machine Learning Approach. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 2704–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, R.; Zhou, L. Spatial Differentiation in the Contribution of Innovation Influencing Factors: An Empirical Study in Nanjing from the Perspective of Nonlinear Relationships. Buildings 2025, 15, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. National Data. 2025. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Li, S.; Zhu, P. The Impact of R&D Subsidies on Innovative Output of Enterprises. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2019, 8, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.G.N. How entrepreneurs perceive technology in the digital era: From aversion to adoption. Ceniiac 2025, 1, e0002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).