Abstract

Regenerative agroecology promotes a suite of methods that diversify farmers’ techniques, crops, and income-generating opportunities. Many low- and middle-income countries struggle with food insecurity, malnutrition, and poverty, relying on natural resources for their livelihoods. In Madagascar, we led agroecology interventions, sharing locally grounded technologies to increase productivity and regenerate biodiversity. We evaluated the short- and medium-term outcomes using a mixed-methods social science approach. We monitored a cohort of over 500 participants in 27 rural communities who trained in market vegetable farming and poultry husbandry between 2019 and 2025. For participants in market vegetable and poultry husbandry interventions, over half adopted new technologies, reporting positive experiences, though outcome achievement varied. Participants in the market vegetable interventions reported they had the knowledge and skills to practice sustainable agriculture, remarking that the hands-on demonstrations and practice facilitated learning, as well as the accessibility of resources for implementation. Women were 1.68× more likely to adopt vegetable farming than men (multinomial regressions, gender log odds = 0.53, p < 0.01), while there was no difference in genders in adoption of poultry husbandry (gender log odds = 0.28, p > 0.05). Most (95–98%, n = 1012) responded they were satisfied with the results of the interventions and would continue to use the skills they learned. Insights generated by this program evaluation led to the following recommendations and improvements: (1) more hands-on demonstrations compared to classroom presentations; (2) more frequent medium-term consultations with participants; (3) introducing microcredit mechanisms to combat cost-related barriers; (4) diversifying outreach approaches. Implementing these recommendations continues to improve outcomes as we scale our interventions.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, agriculture supplies food to a growing population and income for billions of people along the value chain. Almost 500 million smallholder farmers in Africa and Asia supply food for 70% of the population on those continents [1]. Smallholder farming is responsible for around 30% of total crop production and food supply [2] as well as 40–50% of global calorie production [3]. While traditional technologies still produce a vast amount of food for the world’s most marginalized populations, those strategies are becoming less productive due to soil erosion and climate change, among other factors [4]. The combination of vulnerable populations producing substantial amounts of the world’s food and risks associated with future global change leads us to investigate interventions to overcome these significant global challenges.

Among the highly successful interventions for combating food insecurity and malnutrition, improved technologies in market vegetable farming and poultry husbandry are often effective. Such interventions are culturally acceptable, diversify household food production and income, with the additional benefit of improving gender equity through access to supplemental income for women [5,6,7,8,9]. Regenerative agroecology approaches to farming and animal husbandry that are climate-smart are especially well suited for such interventions. Agroecology is a holistic field that fuses agricultural practices with ecological and social processes [10], with 10 guiding elements including on-farm biodiversity, recycling, synergies, and co-creation of knowledge [11]. Regenerative agriculture especially focuses on practices that increase soil health by minimizing soil disturbance (e.g., no-till agriculture), keeping soils covered with mulch and cover crops, and integrating animal husbandry [12]. A meta-analysis of over 500 studies found support for positive impacts on yields using agroecological practices, especially application of organic soil amendments like green manure and crop rotation [13]. In a systematic review of 47 studies, 16 demonstrated positive associations between agroecological practices and improved smallholder resilience and food security [14]. Case studies across different cultures and countries highlighted that agroecology approaches provide both ecological (biodiversity, nutrient cycling) and social (community networks, supportive policy) benefits essential for sustainable, climate-smart farming [15]. There is strong evidence that farm diversification promotes natural pest control, soil fertility, and other indicators of climate change adaptation [16]. Further, application of organic soil amendments significantly increase plant biomass in agroforestry settings compared to pastures, more closely mimicking natural ecosystems [17]. Agroecology training paired with other nutrition-sensitive interventions in Tanzania were also successful in increasing children’s dietary diversity and household food security [18]. Such approaches are low cost, promote soil health with multiple co-benefits, and require less space than intensive agriculture such as rice, commercial plantations, or cattle husbandry.

Madagascar is a renowned biodiversity hotspot, with numerous endemic species that are threatened with extinction [19]. Concomitantly, Madagascar is predominantly agrarian, with 70% of its population living below the international poverty line and experiencing intense food insecurity [20,21]. Malnutrition is high, with up to 49% of children stunted [22]. Despite these obstacles, the tropical climate and resilient farmers produce diverse crops, including some of the world’s most coveted species, like vanilla, cloves, and more [23,24]. The opportunities for regenerative agroecology approaches to inspire a productive, harmonious relationship between people and the agroecosystem lead many conservation and development organizations to share ecological intensification of agriculture with rural communities [25].

Research on program effectiveness highlights the need to align multiple goals and desired outcomes for positive impacts. For example, for smallholder farmers (approximately 80% of Madagascar’s population), improving agricultural outputs can be foundational to reducing food and financial insecurity [26]. Many conservation initiatives implement such livelihood development projects, and prioritizing alternative livelihood opportunities for local populations incentivizes conservation with local benefits in mind [27]. With climate change, it is crucial that farmers adapt their techniques to cope with potential shocks. Some farmers have yet to adopt climate-smart agriculture, especially because of a lack of training and resources, speaking to the need for diverse forms of support to improve agriculture and food security in Madagascar [28]. Reliance on a few staple crops, such as rice and vanilla, leaves many farmers vulnerable to natural disasters and market volatility [20]. Further, farmers’ productivity is often constrained by a lack of resources such as labor, materials, or disposable revenue to implement improved technologies; e.g., fencing agricultural fields to prevent cattle damage and investing in drought-tolerant crops and market access [29]. Comparing the outcomes of small-scale livelihood projects in eastern Madagascar showed that agricultural projects (e.g., farming, aquaculture, animal husbandry) ranked highly for improving community cooperation, strengthening community institutions, and improving food security [26]. It is therefore crucial to address the underlying issues, such as a lack of access to new technologies, to realize sustainable development in the agricultural sector.

In addition to program design, a large component of program success depends on implementation. Despite positive outcome attainment in some programs, in one case, 42% of participants reported no livelihood benefits [7], in part due to insufficient short- and medium-term project implementation, and a need for further capacity-building for local leaders to continue long-term implementation. Further, small-scale poultry rearing and egg production in Madagascar has the potential to diversify incomes and nutrition [30,31], but is limited by biosecurity—the prevention of diseases from negatively impacting flocks. Disease-related mortality is high, especially due to poor husbandry and lack of veterinary services, with 10–25% of income lost due to Newcastle disease [31,32]. Vaccination for Newcastle disease can protect the poultry population if vaccine coverage is at least ~40% over 5+ years [32], requiring sustained veterinary services. Traditional chicken husbandry involves limited feeding; chickens range freely and scavenge feed, limiting meat and egg production [33]. Understanding common problems through program evaluation allows practitioners to identify the barriers to outcome attainment and design novel solutions.

The Duke Lemur Center (DLC) SAVA Conservation program in northeast Madagascar focuses on community-driven interventions, with over 10 years of experience building sustained relationships with grassroots interest groups [34]. The DLC conducts a variety of interventions, such as environmental education, landscape restoration, sustainable agriculture and animal husbandry, fuel-efficient cooking stoves, and more. Listening deeply to the needs of local communities, the DLC co-creates interventions with the communities to address their needs. Among the interventions DLC promotes, the market vegetable gardening and poultry husbandry programs share improved techniques for smallholder farmers. These interventions are aimed at diversifying livelihoods, increasing food and financial security, and improving nutritional health, with social and conservation co-benefits.

This study evaluated the efficacy of the DLC garden and poultry interventions, their short- and medium-term outcomes, and assessed how program design and implementation were related to achieving desired outcomes [35]. Program evaluations aim to provide insights to support program improvement decisions and address questions of a target audience, and this evaluation sought to be both formative, in that it will inform future intervention programming, and summative, because it aimed to understand the benefits of the program to participants and outcome achievement [35].

This study sought to answer the following questions:

- To what extent did the interventions achieve the desired short- and medium-term outcomes for participants?

- Were there differences in outcomes between genders and among different environmental regimes?

- What was the experience of participants in these interventions?

- What worked well, and how can the interventions be improved?

2. DLC-SAVA Regenerative Agroecology Intervention Design

Training was provided for farmers in a variety of regenerative agriculture techniques that can integrate a diversity of crops and domestic animals. In this study, we focus on two types of interventions: market vegetable gardening and farming, and poultry husbandry. We note that the DLC hosts more advanced workshops focused on improved rice production, aquaculture, agroforestry with perennial cash crops like vanilla and cloves, and more. These options were selected based on participatory planning with local communities through focus groups and key informant interviews. The DLC team members provide training and follow-up consultation with farmers, and are supported by the local farming associations, health workers, and community leadership. The communities were engaged with the DLC-SAVA Conservation program in different ways, such as long-term partnerships, assessing opportunities for each partner, and communities requesting training. The team met with local leaders to plan the projects, ask permission to conduct training and education, and announced workshops by gathering people for town hall meetings, sharing the dates and goals of the workshops. The dates and timings of the workshops were decided upon through consultation with the participants.

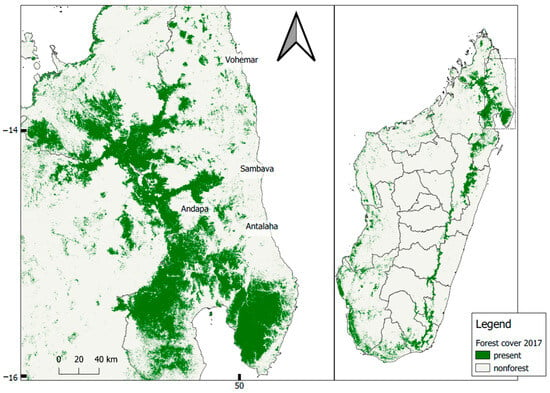

The communities span a heterogeneous landscape in the SAVA region. There are four main districts in the SAVA region: Sambava, Andapa, Vohemar and Antalaha. These districts represent quite unique agroecological opportunities and challenges (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Contexts of environmental regimes investigated across four districts of Madagascar in this study.

Figure 1.

Map of the SAVA region illustrating the locations of the districts as described in Table 1. Forest cover as of year 2017 map comes from [36]. Inset shows map of Madagascar with dashed box indicating the study area, and solid lines illustrating the limits of different administrative regions.

2.1. Market Vegetable Intervention

The market vegetable intervention training package used by the DLC-SAVA Conservation team was adapted from diverse sources [37,38,39,40]. The techniques include in situ composting, or sometimes called trench or lasagna gardening, which entails digging 60–80 cm deep and adding soil amendments in the form of compostable materials such as dry leaves (~70%), high-nitrogen green leaves (~20%), and a mix of char, ash, egg/snail shells (~10%), mixed, watered, and added to the planting beds, mixed with the original soil. This approach quickly adds organic matter and breaks up hardpan compaction. In addition, we teach polyculture, companion planting, cover cropping, crop rotation, compost and organic insect repellents. The first workshops used a “training-of-trainers” approach, held in 2019 with the DLC team who would later lead the workshops. Four of the co-authors (J.P.H, R. J. R., J. E., and R.N.J) received initial training in consultation with Peter Jensen and Lynn Van Norman of Terra Firma, International. As of the writing of this manuscript, the team led more than 40 workshops at 30 communities between 2019 and 2024, serving more than 950 participants. Workshops were announced via a town hall meeting as well as a snowball method, asking community leaders to spread the word and invite people.

The market vegetable workshops are typically held over five days (see Supplementary File S1 for the detailed curriculum). The sessions take place in the morning and late afternoon, with a break at midday. Shortly after (typically the following week), the team leads group planting sessions, rotating among participants to plant gardens in each of their yards. Such reciprocal group work, known as “fandriaka” in Malagasy, is a custom describing people coming together to work as a community on an individual’s project (e.g., garden or farmland). This labor is reciprocated among the participating members. While families still help one another through group planting, participants said such reciprocal group work is no longer a prevalent practice at the community level. Group planting sessions occurred in the mornings and participants contribute a cup of rice for lunch, with the main course provided by the trainers. Participants are offered incentives for adopting the new skills taught in the workshops. They are informed that upon successful follow-up evaluations, they can receive a watering can, a fuel-efficient cooking stove, and seeds for planting if they create their own gardens using the techniques they learned.

This manuscript uses a mixed-methods approach, with a quantitative analysis of monitoring data for 530 participants at 27 communities, and a formative and summative evaluation at one community, Ambodivoara, where a vegetable gardening workshop took place from 26–30 July 2022 with 35 participants.

2.2. Poultry Husbandry Intervention

Training in poultry husbandry was developed with and initially led by Dr. Rakotondramanana Rijaniaina Tsiry, a veterinarian from an agricultural services institution in Madagascar (Profis), and his assistant, Ando. Dr. Tsiry taught the DLC team the best practices for the common Malagasy breed. The main learning objectives are the construction of proper chicken coops and pens, producing a locally sourced and balanced diet, and biosecurity, especially focusing on disease prevention methods including vaccination. The workshop led by DLC at Ambodivoara took place over two days, from December 22nd–23rd 2022 with 36 participants (see Supplementary File S2 for detailed curriculum). The first workshops, including at Ambodivoara, were conducted through a series of lectures in a classroom, writing on a chalk board or flip charts, supplemented by a PowerPoint presentation, video projection, and a chicken vaccination demonstration. At Ambodivoara in 2023, the workshop took place in the afternoons. As in the market vegetable interventions, workshops were announced via a town hall meeting and a snowball method.

As incentives, the participants were promised four vaccinated chickens (three hens and one rooster) if they built an appropriate chicken coop by the follow-up. When chickens were distributed, the participants’ existing unvaccinated chickens were all vaccinated and new chickens were quarantined for the best chance of survival. Monitoring and evaluations were conducted across communities between June 2022 and June 2025.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Evaluations

The evaluation used a parallel mixed-methods approach and incorporated both quantitative assessments and qualitative data. Using a standardized assessment survey for each intervention, our team followed up with participants starting within three months of the workshop. The survey was designed to measure whether or not participants were adopting different technologies taught during the workshop. In addition, we conducted qualitative semi-structured key informant interviews and focus group discussions that allowed for an in-depth and exploratory approach to data collection beyond what we could glean from the participant monitoring. The evaluation surveys, semi-structured interview guides and focus group discussion guides were co-created and adapted with feedback from DLC and Malagasy collaborators. This ensured relevance to the DLC’s interests and goals and contextually appropriate questions.

3.2. Quantitative Evaluations

Beginning 3–5 months after the workshops were held, the trainers returned to the communities to locate workshop participants for follow-up evaluations. For participants who could be evaluated, the survey instrument consisted of an informed consent with verbal confirmation, and a series of questions asking whether or not participants adopted different technologies and approaches taught during the workshop (Supplementary Files S6 and S7). If participants did not adopt new technologies, we asked why, and what other training interventions they would be interested in attending in the future. If participants adopted new technologies, they were also asked how their results compared to the past, whether they were satisfied with their results, whether they would recommend the workshop to others, and if they had taught others the techniques they learned. If participants did teach others, we asked who they taught, and in the future, we plan to evaluate those secondary trainees. A Likert-scale was used to gauge how strongly participants agreed with statements such as, “The information gained during the workshop was useful,” and “I used the methods taught in the workshop and had good results.” After, we asked what other kinds of training or interventions participants sought if there would be training in the future.

3.3. Qualitative Evaluations

To listen deeply and obtain a more nuanced understanding of short- and medium-term outcomes from participants, we conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with key informants in one community (see Supplementary Files S4 and S5 for individual interview guides). These interviews were held one year after the market vegetable intervention and six months after the poultry husbandry workshop. The interview guides were developed in English and translated into the local dialect of Malagasy (Tsimihety) by our collaborating peers from the SAVA university and the communities. Questions were adjusted during the translation process based on input from the translators and collaborators. The questions were piloted with two workshop participants. Members of the community forest management association helped arrange the interviews by contacting the randomly selected participants and arranging a time to meet. They would pick an interview venue and bring the interviewers/interviewees to the venue. Participants were given mobile telephone credit cards worth 2000 Malagasy Ariary (~USD 0.50) for their participation in individual interviews and 4000 Ariary (~USD 1.00) for focus groups.

Respondents were randomly chosen for recruitment from a list of participants in each workshop in this community using a random number generator. Initially, 10 participants (out of 35 for market vegetables and 36 for poultry husbandry) were chosen randomly from each workshop, but two from each group were not available and were not replaced. Interviews ranged in duration from 50–80 min to complete. Each interview was conducted in Malagasy in person and audio recorded. The recordings were later transcribed verbatim in Malagasy and translated to English by native speakers fluent in English.

3.4. Focus Groups

The focus group participants were those who participated in both the market vegetable and poultry husbandry interventions. They were asked about their experience in each workshop and a comparison of the two (see Supplementary Files S6 and S7 for focus group interview guides). Participants were selected based on availability. Each focus group took 2–2.5 h and was conducted in Malagasy in person and audio recorded. The recordings were later transcribed verbatim and translated to English for analysis.

3.5. Data Analysis

Follow-up evaluation data were analyzed using descriptive statistics as well as inferential statistics to test if different predictor variables were related to the adoption of new techniques (e.g., gender, age, communities or districts). Analyses included chi-squared tests on contingency tables and generalized linear models, implemented in the R statistical environment.

The transcripts of key informant interviews and focus groups were analyzed using NVivo v.14, a qualitative data analysis software, and then coded for themes [41]. A codebook was developed through a mixed deductive and inductive approach after the completion of data collection. Deductive codes are “preestablished and predefined sets of labels that are appropriate given the evaluation question” [35]. In this case, deductive codes in the codebook included codes for desired outcomes and program activities. Inductive coding emerged through consideration of the data and respondents’ “own way of categorizing their experiences” [35]. Inductive codes included themes respondents raised as barriers or facilitators to their outcome achievements such as accountability, cost, feasibility or applicability of teachings, memory, motivation, physical ability, and time.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Evaluations

4.1.1. Market Vegetable Interventions

More than 954 people were trained in market vegetable gardening and farming technologies in 30 communities. We were unable to evaluate 401 participants because they were not accessible, or lived in or moved to other communities too far to survey. Of the 549 participants surveyed, about half had made gardens (Table 2). Of those participants who made gardens, almost all adopted new technologies taught during workshops, generally, and more than half of adopters were women (167 women and 93 men). Women were significantly more likely to make a garden and adopt new technologies than men (multinomial regressions with three levels: (1) no garden, (2) a garden not following the techniques, (3) a garden following the techniques, Table 3, Figure 2). The odds of a woman adopting the new techniques were 1.68 higher than for men. There were no differences among the different environmental regimes.

Table 2.

Summary statistics on adoption of different technologies shared in workshops.

Table 3.

Results of binomial and multinomial regression analyses on adoption of different technologies in the market vegetable intervention. The value represents the regression coefficient, with standard error in parentheses and the * indicates a p value ≤ 0.05.

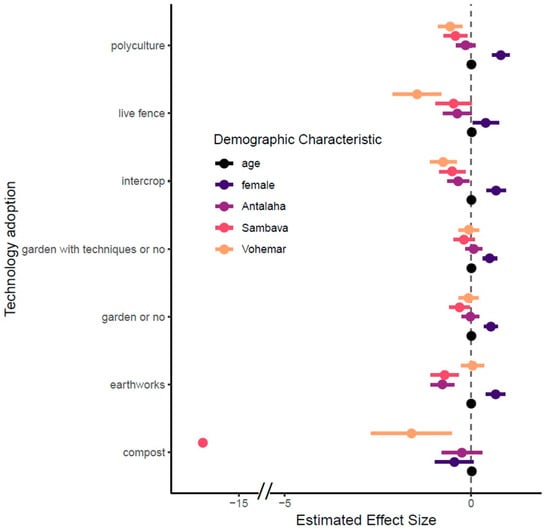

Figure 2.

Effect sizes of different demographic variables on the probability of adopting different market vegetable technologies. Note that for the districts, Andapa was considered the reference level for comparison, and male was the reference level for gender.

In analyses across the different technologies shared in the workshops, women were more likely to adopt than men for all except hot compost and live fencing (Figure 2, Table 3). Age had a marginal, positive effect for only one technology (polyculture, i.e., growing multiple crops in the same garden), and for some technologies, adoption in three of the districts was lower than expected given the baseline of Andapa. In general, respondents reported they somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that they learned new techniques and will continue to use them, though fewer reported they used the techniques and had good results (Table 2).

4.1.2. Poultry Husbandry Evaluations

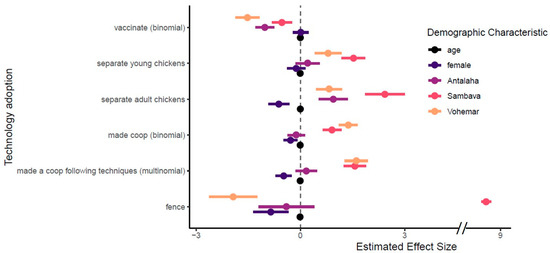

Over 824 people were trained in poultry husbandry technologies in 24 communities. We were unable to follow up with 450 participants because they were not accessible, or lived in or moved to other communities too far to be surveyed. Of the 498 participants surveyed, 44.6% (222) had made a chicken coop (Table 2), with more than half of those adopters using the new technologies taught during workshops, generally; less than half of adopters were women (49 women and 86 men). There was no effect of age, and no significant difference between genders in creating a chicken coop. In contrast, women were significantly less likely than men to make a chicken coop adopting the new technologies (multinomial regressions with three levels—no coop, a coop not following the techniques, a coop following the techniques), which also led to women being significantly less likely to separate adult chickens from the others (Figure 3, Table 4). There were also effects of the different environmental regimes; participants in Sambava and Vohemar districts were more likely to adopt than those from Andapa or Antalaha (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Effect sizes of different demographic variables on the probability of adopting different poultry husbandry technologies. Note that for the districts, Andapa was considered the reference level for comparison, and male was the reference level for gender.

Table 4.

Results of binomial and multinomial regression analyses testing the predictors of adopting different poultry husbandry technologies. Values represent the coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. * indicates p ≤ 0.05.

Separating adult and young chickens and feeding chickens two or more different foods were among the more commonly adopted technologies, while vaccinating and fencing a pen around the coop were less likely to be adopted (Table 2). Most respondents somewhat or strongly agreed they learned new techniques and will continue to use them, though less than a quarter said they agreed they were able to use the techniques (Table 2).

4.2. Qualitative Program Evaluations

4.2.1. General Overview of Interventions

Sixteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants in one of the communities (eight in market vegetables, eight in poultry husbandry) and two focus group discussions were conducted with three participants each. We recognize that this limited sample size is not representative of the views of all participants in the program, but rather illustrates deep insights and nuanced information from a subset of those who were trained. Participants were asked about their perceptions concerning workshop logistics, such as methods of announcement and materials provided. Although the workshops were announced in town hall meetings typical for the culture and the community, seven participants learned about it through other means (43%). Of these, three people were approached by local community leadership who were announcing the workshop throughout the village, while four had been informed by other community members (snowball method), or saw the workshop happening, or saw people on their way to or from the workshop and inquired about it. Three participants had missed the first one or more days of the workshop because they had not heard about it (19%), and one participant remarked that there was low attendance at workshops because “not even half of the people heard about the workshop.”

When asked what people felt was the most effective way to announce future workshops, all respondents felt the approach used was appropriate (town hall meetings), which is standard practice. Of the three participants who mentioned timing, they suggested the workshop should be announced one day, two days, or two weeks before the workshop. Four respondents said that subsequent workshops would likely be well attended because “it is easier to convince people since they have already seen others benefit from it.” In addition to announcing workshops through a community meeting, one respondent suggested posting announcements in public spaces, while another suggested showing people a video announcement.

4.2.2. Market Vegetable Interventions

Generally, participants were pleased with the materials provided, mentioning tools used during the workshop, such as machetes and spades, or calendars of agricultural season, notebooks and pens for note-taking. Each participant was given a notebook and pen for note-taking in each workshop. One respondent who had not yet vaccinated their chickens said, “If I want to vaccinate my chickens I can because I wrote down the information in my notebook.” Participants also shared notes with each other, with one mentioning, “if we could not see what the facilitators wrote, we asked other participants who could take notes to lend us their notebooks for us to write the notes at home.”

Two respondents mentioned how helpful the agricultural calendar given during the market vegetable workshop was, with one saying they became more interested in gardening because “[the trainers] gave me a calendar that tells me you can grow these kinds of crops at this time of the year and you can grow other kinds of crops at other times of the year.” One participant praised the gardening workshop equipment, saying, “the spades that we used in the workshop were not the same as the spades we use in daily life. They were tough, and the machetes used to cut the hay into pieces were good as well.”

4.2.3. Poultry Husbandry Interventions

Participant Motivation

Of the eight KIIs with participants from the market vegetable intervention, seven respondents said they participated in the workshop because they wanted the security of food and income that comes with growing their own vegetables (88%). They hoped to “no longer have to buy vegetables and.... also have some to sell.” When asked why they attended the workshop, some said, “because I am a farmer” and felt motivated to improve their craft and pursue better outcomes (n = 3, 37.5%). One respondent stated they were motivated to improve their skills to teach others.

Respondents were asked to speak about their experience with the market vegetable workshop. All respondents reported a positive experience in the market vegetable workshop. One stated, “in general, it was wonderful and worthwhile,” and another said, “everyone could learn from their teaching techniques.” When asked if anything was missing from the workshop, one respondent said, “We learned lots of things in the training that could have taken months and long hours every day...It did not take long, but we could learn many things. That is why I say it was just right.” The location for the training was selected based on participatory selection of a volunteer, who offered a corner of his yard as the training venue. All respondents were pleased with the selection of the site saying, “it was comfortable because it was not too far and not too close to the streets. It was good.”

Respondents generally appreciated the incentives, such as seeds and watering cans given to those participants who adopted the new techniques. One mentioned, “I…need the watering can because if it does not rain for 3 days in a row, I will have to water my vegetables. It is great that they gave us these materials” (see also Supplementary File S9 Selected Quotes, SQ1). Seven of the respondents mentioned receiving a watering can from DLC (88%), while one had not because they were not in the village during distribution, despite having completed the criteria to receive one. One respondent also requested more seeds, saying, “sometimes we want to grow things here but there is a time when we do not have any money. So, what I want is for you to give us seeds if possible.”

Respondents were asked to comment on the suitability of the workshop’s time duration, the seasonal timing, and the time commitment required to accomplish the teachings. All respondents felt the workshop was appropriately timed (n = 8 KIIs, n = 6 participants in focus groups, 100%, SQ2, 3). Most respondents were satisfied with having the training in July and August (n = 11, 79%, SQ4, 5), while three respondents felt March would be a better time for a workshop because that is when they are preparing their gardens (SQ6). Some respondents noted the time they were able to dedicate to applying their new skills was limited (n = 7). One noted, “it takes too long because you have to wait for the compost elements to decompose…That is what I really do not like about the workshop, that it takes too long and requires too much effort” (see also SQ7).

The training aimed to increase knowledge and skill attainment as well as feelings of self-efficacy to act upon the workshop teachings. Medium-term outcomes included whether a respondent has changed their behavior as a result of the workshop. An emerging outcome was perceived improvements in crop productivity as a result of implementing the new technologies. Another emergent outcome was the cascade or snow-ball effect of participants sharing the skills they learned teaching others.

Hot Compost and in Situ Composting

There were clear gains in knowledge and skills regarding both hot compost and in situ composting, with mixed gains around self-efficacy and behavior change. Some respondents who mentioned composting reported they enjoyed learning about it (n = 5), with two saying, “the most important part of the workshop…was compost-making techniques.” In contrast, others were not interested in it (n = 3). The majority of the respondents who mentioned composting felt they had the knowledge and skills to do it (n = 8); e.g., “I also learned that everything is of some use like kitchen scraps, banana skins, and so on because we can use them [for compost].” Despite the perceived value, respondents felt it required too much labor and time, instead preferring in situ composting (e.g., SQ8, 9), and personalizing/adapting the technologies according to their preferences; e.g., “the training was good, but it is up to you to pick the parts you can do. If it was a journey, it is up to you to make it quicker.”

Several respondents valued learning about in situ composting and reported feelings of self-efficacy, with 100% (n = 8 participants in KIIs) saying it was one of the most important lessons gained from the workshop (e.g., SQ10). Three participants said that before learning about in situ composting, they practiced shifting agriculture, including transforming forest into farms, seeing no alternative (n = 3). Participants who used in situ composting felt it improved their output, reporting they felt their land was becoming more productive when they practiced skills taught in the workshop (SQ11).

One respondent directly compared hot compost and in situ compost, saying, “If you are in a hurry to farm, [hot compost] will take too long. But there is another one … where [the trainer] added the components directly into the soil [in situ composting] … I think it is good for farming.” In situ composting was difficult for some, however, because of the effort required. One participant responded, “it sounds simple, but it is tiring to do because you tear all the leaves into pieces. It tires me out.” Creating compost can be facilitated through reciprocal group work (SQ12).

Intercropping

There were clear gains in knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy regarding intercropping. While all four participants who mentioned intercropping understood the concept and felt they could implement the technique, only one had adopted the technique while two participants conveyed they were not interested in adopting (50%, e.g., SQ13, 14). Some were still open to revisiting the topic, however (SQ15). We note that we draw a distinction between intercropping—planting multiple crops in the same garden bed—and polyculture—planting different crops in the same garden, though not necessarily in the same bed. This suggested that, although respondents report skills gained and feelings of self-efficacy, behavior change outcomes were mixed.

Natural Pest Repellent

There were mixed gains in knowledge and skills regarding natural pest repellent with high gains in behavior change. Some participants wanted additional training (n = 2, 33%). Respondents regularly struggle with pests and appreciated having alternatives to insecticides, saying:

I did not expect them to teach about organic natural pest repellent. These days we have problems with insects, and many of our crops are just dying. I thought they were going to suggest using chemical insecticides … but they said to use green leaves as a natural insect repellent. Not only does this organic natural insect repellent kill the insects, but it will also help our crops grow better.

Many began to use chili peppers, as taught in the workshop, because they are available in abundance and respondents felt they were effective (SQ16). Four participants (67%) reported using natural insect repellents as taught in the workshop successfully, while one said they tried it but found it ineffective (17%). This suggests respondents valued natural insect repellents and the teachings led to behavior change.

Poultry Husbandry

A primary motivation for participants in the poultry husbandry workshop was the financial security chickens provide. Respondents reported raising chickens to eat and to sell during times of financial challenges. Respondents reported chickens are mostly eaten during celebrations and raising them means avoiding a financial shock during holidays (n = 12, 86%, e.g., SQ17).

Most participants saw chicken husbandry as a financial investment (n = 8 KIIs and 4 focus groups, 86%). One gave examples of how chicken husbandry helps achieve long-term goals and overcome financial shocks:

I can cope with difficulties. For [children’s] education for example. I have a chicken that has 10 chicks… When they are big, the amount I get from [selling] these chickens can support a child’s education. Apart from that, I can buy goods from the money that I get from [selling] chickens. I do not have to worry in case of difficulties. I was sick not too long ago, and I was in bed when I asked someone in my house to sell the chickens [for medical expenses].

Many also expressed that they had limited interest in consuming chickens outside of special occasions (SQ18), preferring to breed their chickens to sell rather than consuming the chickens themselves. Only one participant said that they raise chicken to eat, not to sell.

Participant Experience

Respondents were asked to speak about their experience with the poultry husbandry workshop, including which topics they found the most and least interesting and how they felt about what they had learned. Respondents generally had a positive experience; all reported they learned new skills from the workshop (n = 14, 100%, e.g., SQ19). One stated, “when the training was finished, I understood what they taught us well. I bought chicks to put what I learned into practice.”

Location

Unlike the garden workshop, which was conducted outside, the poultry husbandry workshop was held in a house used by the local community leadership to host their activities. Most respondents said the venue for the workshop was comfortable and did not have any recommendations for improvement (n = 8 KIIs and 2 focus groups, 91%). Some respondents named limitations with the venue (n = 4, 36%), with five reporting complaints about the location such as low light, hot conditions, and enough chairs (SQ20–23). This suggests that while the venue was appropriate for most respondents, it also had its limitations.

Incentives

At the time of the data collection, follow-up evaluations were still ongoing and as such, respondents had not yet received the four chickens promised to them if they built a coop. Though the incentive is desirable, it is likely insufficient alone to facilitate adopting new technologies. For example:

I am not the only one to say that we need your support to improve chicken husbandry. We have a different level of life. Some are rich enough to make a good chicken coop that has different sections, wooden floors, and made of metal sheets. Some are poor and cannot do anything, like me. It is very difficult for a poor woman like me to do something good, so they should give more support to help us achieve it. They promised to give us chickens if we can make a modern chicken coop, but that will be difficult for me if I do not get any support.

This suggests that incentives like offering chickens cannot overcome large barriers, like cost, which restrict participants’ abilities to implement the new technologies. It is crucial that such interventions fulfill their commitments to communities (SQ24). We note that upon completion of the evaluations, all participants who created chicken coops and pens received the three hens and one rooster, as promised. To date, over 200 farmers received chickens from DLC, and in many cases, if those chickens died or were stolen, they were replaced.

Timing

Respondents were asked to comment on the suitability of the duration of the workshop and the seasonal timing of the workshop. All respondents felt the workshop was appropriately timed (n = 14, 100%, SQ25, 26). Most respondents were satisfied with having the training in December (n = 11, 85%), with one saying it was a suitable time because “[chicken] diseases come in January,” and by having the workshop in December “we [will] already have medicine against chicken diseases… so our chickens will not get sick.” Alternately, two respondents felt December is a difficult time to hold a workshop because it is a time of high agricultural labor investment, and suggested September or October as a better time, while another suggested March, during the rainy season when chicks’ survival rates drop. Three respondents said time was a limiting factor (n = 3, 75%, SQ27). Only one participant reported, “it is not something that takes too much time to achieve” (n = 1, 25%).

Chicken Coops

All respondents who commented on chicken coops reported short-term outcome achievements, reporting knowledge gain in how to create a chicken coop, with different sections to separate chickens by age (n = 14, 100%), and mixed gains around self-efficacy and behavior change. One respondent proudly stated, “I feel like I have the skills in chicken husbandry now because… I know…the importance of the cleanliness of the chicken coop. I also know about growing green leaves [for feed], giving clean water to the chicken, and making different sections in the chicken coop.” A respondent recounted the new knowledge gained from the workshop, saying, “the facilitators taught us that the chicken coop should be clean…I did not clean the coop before,” and reported positive outcomes, saying that since they began cleaning their coop weekly they have noticed fewer pests on their chickens. Two respondents (14%) mentioned adding sections to their coop, saying, “There are sections in the chicken coop…I did not have that before. I also did not know that the small chicks should be in a section where they can get sunlight. That has changed how I manage my chicken husbandry.” These direct statements in the qualitative surveys support the quantitative surveys which demonstrated the causal effect of the intervention on adopting new chicken coop designs.

Respondents were interested in learning about how to build or improve their chicken coops. Though in the KIIs and focus groups, we did not specifically ask how many respondents improved or created chicken coops, four respondents mentioned not having a chicken coop at all (n = 4, 29%). Six respondents (43%) mentioned having a coop but being dissatisfied with it, expressing sentiments such as, “the one they taught at the workshop [during a video presentation] has a wooden floor and there is wire netting at the top. But I do not have the resources to make one like that. I just made a simple one.” Five respondents (36%) asked for demonstrations of how to build a coop, saying, “… they [should] do what they did with the garden workshop. They should [demonstrate] what they taught, showing everybody what they taught in the workshop and not just theoretically.”

Chicken Feed

There were challenges to gaining knowledge and skills regarding chicken feed, with mixed gains around self-efficacy and behavior change. There were several cases of behavior change, such as participants beginning to provide more nutritious feed and clean water for the chickens. Two respondents mentioned, “they also taught us to give clean water to the chickens. We did not know about those things before. We did not know that chickens also need to drink.” Another respondent noted:

I used old traditional chicken husbandry techniques before…. Sometimes they would not get any food at all. I did not know about grinding corn and mixing the corn powder with some salt and many other types of chicken food. After the workshop, I am doing my best to give new food.

While about half of respondents reported finding value in the skills taught overall (SQ28), the other half expressed shortcomings (n = 7, 50%), saying they felt it was confusing and would like a review (e.g., SQ29). The participants in one focus group (n = 3) reported that while some of the ingredients recommended for chicken feed are locally available, others are too expensive. For example, peanuts and corn were reportedly too expensive, so they only feed their chickens with rice husks or uncooked rice, which is also challenging during periods of food insecurity. Because of financial barriers, participants felt unable to adopt these new skills and reported low self-efficacy. Several participants were confused about how to make chicken feed (e.g., SQ30), reporting that there was no demonstration. One participant noted “they taught about the grams of corn powder and soybean powder needed. To make sure everyone understands what they mean by grams, they should demonstrate it.”

Biosecurity

There were clear gains in knowledge and skills regarding biosecurity, especially in the administration of vaccinations, with mixed gains around behavior change. After the training, many respondents valued vaccinations but found them expensive, and some expressed regrets that their chickens were not vaccinated in the demonstration (SQ31).

The intervention taught how to safely administer vaccines. Attaining such independent skills is important, since veterinary services are inaccessible in the remote countryside (SQ32, 33). Less than half of the respondents are not vaccinating (n = 6, 43%), and those who are see the benefits: “I vaccinated my chickens but not all of them. The unvaccinated ones became sick. But now I vaccinate the chickens as soon as they reach two weeks old.”

Cost

All respondents who mentioned cost felt it was a barrier to them implementing the teachings from the workshop (n = 10, 100%). The main barriers are the perceived costs related to chicken feed and construction of the chicken coop and fences, with one saying, “If we cannot change the food [simplify the chicken feed], we will not be able to feed our chickens every day.” Of the respondents who felt cost was a barrier, four reported the chicken coops were the most expensive, one reported fencing, three reported vaccines, and three said chicken feed.

Comparing Interventions

Eight people were identified who participated in both the market vegetable and poultry husbandry workshops. Of those, six participated in two focus groups conducted with three participants each. To assess overall preferences, focus group participants were asked which workshop they would prefer if they could only attend one. The majority of respondents preferred the chicken husbandry workshop (n = 4, 67%), because chickens have a higher income generating potential than gardens. One said, “if I [sell] three garden beds of green leafy vegetables, the money from that cannot buy a chicken.” One said they also prefer learning about chicken husbandry “because it is harder [than gardening] so I want to learn more about it so that I can find a way to make it beneficial.” The two respondents who preferred the gardening workshop said, “because we rely on farming here. Our life depends on farming, whether it is vanilla or rice or gardening. So, if I had to choose, I would prefer to attend a gardening workshop.”

During the focus groups, respondents were asked to compare incentives between the two workshops. All respondents across both focus groups felt they were more motivated to carry out the teaching from the workshop due to the incentives (n = 6, 100%), supporting the value of incentives to the success of the program. Three respondents said all incentives were equally preferred (50%). One said, “they are all important, but I prefer chickens…because they taught us in the workshop that we can use plastic bottles if we do not have a watering can” (n = 1, 17%). Two (33%) preferred the gardening workshop incentives, with one saying, “the watering can and fuel-efficient stove are the most important to me because they are not something that I [can] create. If I want to have chickens, I can buy them when I have money.”

5. Discussion

This study sought to assess the efficacy of a development intervention aimed at increasing knowledge and skills in market vegetable gardening and poultry husbandry. We operated under a logical framework that focuses on empowering farmers in northeast Madagascar to apply regenerative agroecology practices. Our desired outcomes included (a) adoption of regenerative agriculture technologies, (b) gender equity in adoption, and (c) motivation to continue using the new technologies with improved results. The indicators we used were quantitative (the proportion of participants adopting new technologies, comparison of the likelihood of adopting new techniques between genders and among bioclimatic zones), and qualitative (the perceptions of participants about the training they received, their ability to employ the techniques themselves, and how the training affected their behavior). Our activities include training workshops with hands-on practice, monitoring and evaluation of adoption, and analysis of correlations from quantitative data and interpretations of causation from the qualitative data. Within this framework, our results explore the variable uptake of new technologies by over 500 participants.

Based on quantitative assessments, we found that 30–50% of the participants monitored adopted the technologies shared in the workshops. More women adopted gardening than men, though there was no difference between genders in adoption of poultry husbandry. There was no effect of age. There were differences in adoption of poultry husbandry techniques among environmental regimes. Using qualitative evaluations, we listened deeply to participants to understand the perceived benefits as well as the limitations of the workshops performed. When considering experience and outcome attainment, the gardening workshop performed well and reached desired outcomes. Reasons included the value of gardening for local livelihoods, the use of demonstrations and hands-on practice sessions, as well as the accessibility of required resources for behavior change. Although participants had generally positive experiences in both workshops, the poultry husbandry training had limitations. For example, knowledge and adoption of chicken coop construction and the creation of chicken feed were hindered by cost barriers and some reported they found the explanation unclear. Despite the limitations, participants reported gains from the lessons on biosecurity and explanations of how to construct a chicken coop and keep it clean.

Overall, the market vegetable intervention achieved the desired short-term outcomes. Our evidence shows that the curriculum was clear and informative, and respondents felt motivated to practice what they learned. Almost 60% of participants trained adopted new techniques and 90% of adopters stated their results were better than with their previous techniques. Women were significantly more likely to adopt new vegetable farming techniques than men. Though age had only a marginal effect on the likelihood of adopting polyculture, anecdotally we note older participants were generally more motivated to participate in workshops and adopt new techniques. Older participants noted that they have many years of experience farming, but they notice changes in productivity which they attribute to declining soil quality and changing climates. They also stated that they are interested to participate in workshops because they see their past techniques are no longer productive and they want to improve for themselves and for their families.

Evidence shows that participation in the workshop increased knowledge and skills, with understanding and adoption especially high for in situ composting (95% of adopters). Most respondents reported a change in behavior with variable adoption of different techniques. In particular, in situ composting was one of the most commonly adopted technologies, which is the incorporation of compostable materials into the soil as a direct amendment. When compared to hot composting, in situ composting was preferred because it was perceived to be faster; rather than waiting three months and turning the compost pile every two weeks, participants appreciated that they could add the amendments directly before planting and immediately plant afterwards. Similarly, case studies in Tanzania revealed that demonstration and hands-on practice of in situ composting methods involving direct application of crop residuals and manures to the fields produced high yields of quality vegetables and the methods were readily adopted [42]. We observed moderate adoption of rainwater capturing earthworks, like small swales and pocket ponds around the garden beds. While some participants did not perceive a need for such earthworks, others remarked at how effective they were for harvesting rainwater directly in the garden. Women were more likely to adopt earthworks than men, and it likely helped to decrease the workload of watering the garden. Adoption of new agricultural technologies was increased when participants perceived advantages related to climate change adaptation and for soil productivity [43]; in this case, adapting to more seasonal and unpredictable rainfall by capturing rainwater in the garden. Other practices, such as intercropping and the creation of hot compost, were least often adopted. For intercropping, women were significantly more likely to adopt than men, but those farmers who did not adopt expressed they were less likely to use the practice due to habit and preference for growing each crop in its own bed. For hot compost, participants expressed less interest because of the added labor required to turn the pile every two weeks and the long time investment (~three months).

These results also mirror the findings from similar agricultural development projects in Madagascar. For example, because market vegetables are a staple food and source of income in this setting, the workshops were well attended and methods readily adopted. As pointed out in other livelihood development projects, interventions must match the interests of local participants for the benefits to be long-lasting [26]. Further, because the interventions addressed both food and income security, participants reaped multiple benefits, which is important for adoption [6,7]. Such interventions are especially empowering for women, with knock-on effects for nutritional health in mothers and infants [6,7,8]. It is, however, noteworthy that more than 40% of participants did not adopt new techniques, reporting they did not have time or materials (30% of respondents). Similarly, in agricultural interventions in eastern Madagascar, ~50% of participants perceived benefits only during the projects, while the other half felt benefits were ongoing post-intervention [26]. We also note that the process of conducting follow up evaluations is a source of encouragement for participants, and receiving incentives upon successful completion of gardens and chicken coops is an important motivator. The evaluations are not only for data collection, but also an opportunity to deliver agricultural extension services like advice and hands-on demonstrations to reinforce skill development. Building relationships among trainers and participants is an important part of the success of this program. Thus, by addressing multiple dimensions of livelihood challenges, the market vegetable interventions are likely to be a sustainable solution to real-world problems in low- and middle-income countries.

In general, the poultry husbandry intervention achieved many of the desired short-term and medium-term outcomes. Almost 45% of participants trained adopted new techniques, especially building a chicken coop (61% of adopters) and separating the adults from younger chickens (30%). While men and women did not differ in their likelihood of making a chicken coop, women were significantly less likely to build the coop according to the standards shared in the workshops than men, because the labor investment of building a chicken coop is especially challenging for women, as revealed by the qualitative results. Our results show that participation increased knowledge and skills in how to create a chicken coop and biosecurity focused on chicken health, hygiene, and vaccinations. Building the chicken coop was a crucial step in the training that distinguishes the intensified approach from traditional husbandry practices because the chickens are secured at night in a clean space protected from the elements. Separating younger and older chickens is also key because it decreases competition for food and speeds growth. These clear advantages may be the main reason the techniques were adopted. In contrast, most participants reported in semi-structured interviews that they lacked the knowledge or financial ability to produce balanced chicken feed as they were instructed, and about 74% of participants are providing a mixed diet. The production of chicken feed is also challenging because of the quantity required and access to enough raw materials for daily feed (e.g., corn, beans, cassava, peanuts, other protein sources). For populations facing challenges of food security, having enough food for the household is already challenging, and the added burden of feeding a flock of chickens is prohibitive. For these reasons, some techniques were more likely to be adopted than others, which can assist in future workshops to emphasize the importance of those techniques less frequently adopted.

The poultry husbandry intervention was limited in changing behaviors for some of the respondents. While many respondents had or wanted chickens, they felt unable to build a chicken coop due to financial constraints; however, respondents with coops reported making more of an effort to clean it and generally provide their chickens with clean water and a more nutritious diet. This suggests respondents are willing to make changes but face barriers such as cost. Outcomes and perceived benefits for other chicken husbandry interventions in eastern Madagascar similarly found mixed results; while almost 50% of respondents reported benefits were ongoing, almost 50% said that benefits were only perceived during the time of the project and almost 90% said the projects delivered none or only some of the expected benefits [26]. As found in other parts of Madagascar and South Africa, many small-scale producers are not achieving their potential productivity due to input costs (e.g., high-quality feed), as well as low access to training about new techniques [31,44]. Therefore, training interventions are only one element of an enabling environment to encourage positive change; financial investment is needed to put the acquired knowledge into action.

Financial and labor limitations prevented respondents from being able to achieve medium-term outcomes in chicken husbandry and, to a lesser extent, in their gardening, as seen in similar cases in Tanzania [43]. Despite limitations, people’s desire for improvement and willingness to engage with the DLC is a substantial facilitating factor and should be harnessed through continued engagement. This willingness is seen when several respondents stated that they want to engage in workshops whenever possible and will make room in their schedules to participate. Incentives also encouraged these positive outlooks.

We examined short- and medium-term outcomes following training in regenerative agroecology principles and technologies. Long-term outcomes, such as changes in yields, income, nutritional status, soil health, and on-farm biodiversity are the next phase of our focus in evaluating the impacts of our interventions. For a subset of participants, we conducted pre-intervention household interviews that measured indicators of socioeconomics, agricultural productivity for subsistence compared to market integration, food security, dietary diversity, and nutritional health of mothers and infants. We also assessed indicators of soil health including soil respiration (a measure of microbial life), compaction, texture, and other metrics. Our design entails repeated post-intervention measurements of these parameters at annual intervals for five years to test for changes over time compared to pre-intervention and compared to control individuals who did not adopt the new technologies. Such research is timely because few studies examine outcomes beyond exit interviews, and those that do follow longitudinal cohorts often demonstrate the improvements in livelihoods and soil health [17]. As of the writing of this article, we are in the fourth year of our cohort study and plan to conduct the final resample in 2026. While practical aspects of agroecology such as particular methods and an emphasis on no harm to the environment have predominated, more adoption is needed in the social and economic dimensions for true adoption of agroecological elements in society [45].

Recommendations

From this study, several recommendations were developed directly from respondent requests or through observation and analysis of best practices to overcome the mentioned barriers. Suggested recommendations include basic adjustments in the lessons and logistics as well as future interventions to combat cost-related barriers. Some of these recommendations have already been adopted as the DLC continues to adaptively manage this community-driven conservation intervention.

Multiple respondents suggested building a chicken coop together during the workshop for hands-on practice. We have since adopted this suggestion, using the reciprocal group work tradition we applied to market vegetable gardening and farming. This allows all participants to see first-hand and practice making a coop, building new skills and confidence in their abilities; further, a subset of participants then have an ideal coop, which can serve as a model for others in the community to replicate. The experience also allows facilitators to explain what adaptations can be made to chicken coops to meet different needs. Because respondents reported confusion concerning the instructions on preparing chicken feed, the trainers have since included demonstrations on how to make the chicken feed using easily understandable measurements (e.g., number of spoons, cups, or handfuls rather than grams or kilograms), resulting in increased understanding and adoption.

In some previous development projects, around half of participants expressed they only received benefits during the lifetime of the project, and they felt no sustained impacts of the project [26]. To overcome such limitations, the DLC regenerative agroecology intervention program involves a training phase and an extended follow-up consultation/evaluation phase, emphasizing sustained contact over time—in this case, around six years. Participants who demonstrate their adoption of new methods regularly receive incentives such as seeds, farming tools like watering cans, shovels and machetes, and chickens. The intervals between training and follow-up range from 2–4 months, allowing participants time to practice methods from the workshop. Return visits for reinforcement and advanced workshops as well as repeated monitoring and personalized consultations continue routinely three to six times per year per community. During the intervals between visits, however, participants expressed that they had questions that were not answered during the training or group work, such as best placement of gardens or chicken coops and how to handle pest insects. To address this gap, the DLC is considering several options for sustained contact with participants.

- 1.

- Help hotline: A designated telephone number of a trainer distributed to the participants, lead farmers, and workshop facilitators so participants can call or text with questions regarding the implementation of workshop teachings. Mobile phone and internet connectivity are increasingly accessible in rural settings, and using these networks can facilitate information spread for rural development [46].

- 2.

- Designated point of contact: One or more workshop participants who excel during training can be designated as a point of contact for the participants to direct their questions. The DLC has adopted this technique to elect lead farmers at the end of training sessions, such that these local leaders can assist with training and lead group work after the trainers leave the community. These lead farmer and “training of trainers” approaches have proven effective in other East African countries such as Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Cameroon, and Malawi [47], extending the post-intervention outcomes for years [48].

- 3.

- Farmer field schools: Demonstration gardens in the community that include the market vegetable and chicken husbandry elements taught in the workshops. Lead farmers can manage these community demonstration gardens where participants can revisit the lessons learned and teach others in the community, facilitating information flow through farmer networks. These methods have proven successful in other settings [49], and the DLC team has adopted the farmer field school approach, co-creating a space with the participants during training at a selected site as part of the reciprocal group work tradition. Advanced workshops and follow-up visits are hosted at these field schools, as well as maintenance techniques.

Community-based credit systems have been used for rural development in over a dozen countries with over one million participants, overcoming barriers with accessing banks and other credit institutions [50]. Such Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs) can combat cost barriers because participants can take small loans to purchase materials for building a chicken coop or fencing and providing diversified diets. Profits generated by the income from improved farming and chicken husbandry are reinvested in the farmers’ personal savings accounts, paid out in annual cycles. In an example from Zanzibar, rural households increased their consumption expenditure (an indicator of disposable income or wealth) by as much as 38% by participating in VSLAs. The DLC is piloting VSLAs in six communities with almost 200 members, and finding preliminary results to support the effectiveness of such microfinance interventions. Therefore, we recommend expanding interventions in microfinance to assist farmers in overcoming financial obstacles to adopting new technologies.

To announce the upcoming workshops, the DLC team respected traditional methods such as calling townhall meetings and using a snowball technique to inform potential participants via word-of-mouth. Respondents reported that they felt this approach was appropriate; despite this, we observed that many potentially interested participants had not been notified about the program and we were not able to reach all the community members who were interested in the interventions. We adapted by making multiple announcements several days in advance to raise awareness about the upcoming training opportunities. In addition, one effective method of public announcements we adopted is posting flyers in public spaces with information about the training date, time, and location. We found this dramatically increases the number of participants in workshops, and is potentially more equitable because it does not rely on social networks or presence at the townhall meeting.

Two respondents requested a pamphlet summarizing the teachings. One specified, “we need a book so that we can see pictures showing us what to do. The book should show pictures strengthening what we were taught in the workshop,” One respondent reported that they were not able to take or read notes because they had not attended school, and we recognize that illiteracy is common in this setting. We are currently designing training manuals which emphasize pictographic representations of the material taught during the workshop which we can print and deliver, as well as short video guides we can distribute on DVDs to deliver to participants as pedagogical materials which can be used and shared.

6. Conclusions

Across both intervention types, adoption of new technologies varied between 30–60%. In some cases, 90–100% of respondents reported positive outcomes of the workshops and applying the new technologies. Adoption rates were low, however, for technologies that were labor intensive. Many respondents from the market vegetable intervention reported achieving both short- and medium-term outcomes but had varied interests in and propensities to adopt different technologies (e.g., 49% adopted in situ composting while only 4% adopted hot composting). Respondents’ gains were due to demonstrations, practice, and the accessibility of required resources for implementation, particularly in situ composting. Women were 1.68 times more likely to adopt market vegetable gardens than men. Some respondents felt cost was a barrier preventing them from creating a fence around the garden, though the training emphasized the fence should be made of live branches freely obtainable around the community.

The poultry husbandry intervention did not achieve as many of the short- and medium-term outcomes as the market vegetable intervention, though gains were still indicated especially in knowledge and skill for building a chicken coop and providing vaccinations. Women were 0.62 times less likely to fully adopt new technologies in poultry husbandry than men. Cost and labor investments were notable barriers for the participants, especially women, because acquiring and assembling the materials required for a chicken coop and fencing were difficult and therefore many participants had not built a coop. Improvements can be made in the explanation of creating chicken feed, as well as demonstration with hands-on practice for building a coop and creating chicken feed.

With these results, we fill gaps in the literature related to gender equity in rural development projects, and shed new light on the probability of adopting new agroecology technologies in rural Madagascar. The DLC is improving the approach to delivering these interventions for communities around the SAVA region to improve food and income security, as well as develop professional skills in agriculture. Through this program, farmers engage in peer-to-peer exchange which facilitates information transfer, solidarity, and helps forge stronger communities. Many of the participants in interventions are creating their own farming associations, and the DLC team is facilitating them to formalize the associations and gain legal status. Through sustained partnerships with communities, the DLC is forging long-term collaborations with communities best positioned to be stewards of the precious natural resources in Madagascar.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411134/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.H., D.N. and N.W.R.; Methodology, J.P.H., D.N., R.J.M., R.J.R. (Rasoavanana Julice Rauchilla), R.C., J.E., R.A.F., P.J., M.E., E.C., A.V., N.G., R.J.R. (Randriamarozandry Jean Roméo), R.N.J., J., Z.R.O. and N.W.R.; Formal analysis, J.P.H., D.N. and N.W.R.; Investigation, J.P.H., D.N., R.J.M., R.J.R. (Rasoavanana Julice Rauchilla), R.C., J.E., R.A.F., P.J., M.E., E.C., A.V., N.G., R.J.R. (Randriamarozandry Jean Roméo), R.N.J., J. and Z.R.O.; Resources, J.P.H.; Data curation, J.P.H., D.N. and J.E.; Writing—original draft, J.P.H. and D.N.; Writing—review & editing, J.P.H., D.N., R.J.M., R.J.R. (Rasoavanana Julice Rauchilla), R.C., J.E., R.A.F., P.J., M.E., E.C., A.V., N.G., R.J.R. (Randriamarozandry Jean Roméo), R.N.J., J., Z.R.O. and N.W.R.; Visualization, J.P.H.; Supervision, J.P.H. and N.W.R.; Project administration, J.P.H. and D.N.; Funding acquisition, J.P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support of the Duke Bass Connections program, the General Mills, the Kathryn B. McQuade Foundation, The Duke Endowment, and the Triangle Center for Evolutionary Medicine.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Duke University (protocol code 2020-0599, 9 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study using the statements are provided with the survey instruments in the Supplementary Materials.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are available from the first author upon reasonable request from the corresponding author under conditions of a data use agreement as per Duke University IRB guidelines.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Malagasy government for allowing us to conduct these interventions and research (Madagascar Ministry of Public Health permit #073/MSANP/SG). We thank the Malagasy Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Ecosystems for facilitating our research, and the community leadership at Ambodivoara for assistance and welcoming us in their town. We also recognize the valuable contributions of numerous field assistants without whom this work would not be possible. Many thanks to Rakotondramanana Rijaniaina Tsiry and assistant Ando, as well as Peter Jensen and Lynn Van Norman, for training our DLC team in methods we adapted for our interventions, and Emilien Razafindrabozy and Andriantinefiarijaona Ardhilles for assistance. This is Duke Lemur Center publication # 1643.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fanzo, J. From big to small: The significance of smallholder farms in the global food system. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Mehrabi, Z.; Jarvis, L.; Chookolingo, B. How much of the world’s food do smallholders produce? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samberg, L.H.; Gerber, J.S.; Ramankutty, N.; Herrero, M.; West, P.C. Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 124010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. IPCC Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Keding, G.B.; Msuya, J.M.; Maass, B.L.; Krawinkel, M.B. Relating dietary diversity and food variety scores to vegetable production and socio-economic status of women in rural Tanzania. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakstad, M.M.; Mosha, D.; Bellows, A.L.; Canavan, C.R.; Chen, J.T.; Mlalama, K.; Noor, R.A.; Kinabo, J.; Masanja, H.; Fawzi, W.W. Home gardening improves dietary diversity, a cluster-randomized controlled trial among Tanzanian women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Antoinette, P.M.; Uddin, N. Impact and cost-effectiveness of women’s training in home gardening and nutrition in Bangladesh. J. Dev. Eff. 2016, 8, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, A.; Pandey, P.; Nielsen, J.; Pries, A.; Spiro, D.; Davis, D.; Quinn, V.; Haselow, N. Combining Home Garden, Poultry, and Nutrition Education Program Targeted to Families with Young Children Improved Anemia Among Children and Anemia and Underweight Among Nonpregnant Women in Nepal. Food Nutr. Bull. 2017, 38, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Abril, A.; Alajajian, S.; Rohloff, P.; Proaño, G.V.; Brewer, J.; Jimenez, E.Y. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Research Network: A Home Garden Intervention Improves Child Length-for-Age Z-Score and Household-Level Crop Count and Nutritional Functional Diversity in Rural Guatemala. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 640–649.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliessman, S. Defining agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]