Abstract

The effectiveness of national energy transitions increasingly depends on public support for state-led measures; yet little is known about societal expectations regarding government assistance for renewable energy-oriented businesses. This study examines public expectations regarding state support for renewable-energy-oriented enterprises in Poland. Using a nationwide survey of 1000 adults (N = 974 valid responses), we developed a latent construct measuring attitudes toward pro-RES business policies. Overall public support is high (M = 3.73; median = 3.86). Women express significantly stronger support than men (median 3.86 vs. 3.71), and Baby Boomers score higher than younger generations (median 4.00 vs. 3.57–3.71). The most notable differences relate to respondents’ experience with RES: Individuals already using renewable energy at home report substantially higher support (M = 4.03) than non-users (M = 3.67). Similarly, those planning to adopt RES within three years show stronger approval (M = 4.07) compared with those not planning adoption (M = 3.43). Education, income, and place of residence do not significantly differentiate attitudes. The findings indicate broadly favorable public sentiment toward state-led support for green entrepreneurship, especially among specific demographic groups and those personally engaged in RES. These insights provide actionable guidance for designing socially legitimate and politically robust sustainability policies.

1. Introduction

Renewable energy production plays a crucial role in the global energy transition, serving as one of the primary pillars for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The steady increase in electricity demand observed since the early 1990s has led to a significant increase in greenhouse gas emissions and an intensification of adverse environmental impacts. Fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—remain the dominant energy sources in many developing countries, which poses a significant challenge in combating climate change [1].

Renewable energy sources (RES) are a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, as their exploitation involves minimal carbon dioxide emissions and other pollutants. As a result, they contribute to reducing the greenhouse effect, improving air quality, and reducing health risks for societies [2]. At the same time, RES play a significant role in diversifying the energy mix, increasing supply security, and reducing countries’ dependence on fossil fuel imports [3].

Transforming towards a low-emission economy, however, requires massive investments. Estimates indicate that investments of $7.3 trillion will be needed between 2010 and 2030, underscoring the magnitude of the decarbonization challenge [3]. To date, a significant portion of renewable energy project financing has relied on public funds, corporate bonds, and the capital of large institutional investors. However, fiscal constraints and rising national debt significantly reduce the ability to further support the transformation solely through public funds. Therefore, the private sector’s involvement, particularly through the development of project financing mechanisms, enables large-scale investments in renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal energy [1,4].

Energy is considered a catalyst for economic development, as it determines the functioning of the modern economy and influences all aspects of socioeconomic life. At the same time, traditional energy sources are a significant contributor to environmental degradation. Therefore, reducing fossil fuel energy consumption and replacing it with clean alternatives has become a global priority for political, administrative, and scientific efforts [5]. Diversifying RES reduces dependence on fossil fuel companies, curbs energy shortages, and mitigates the effects of climate change.

In this context, the importance of businesses is growing, increasingly becoming catalysts for developing a green economy. Companies implementing RES are crucial for reducing emissions and building modern, sustainable business models. Companies increasingly integrate renewable energy into their operations, recognizing the financial benefits of reduced operating costs and the reputational advantage of implementing strategies based on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and ESG criteria [6].

Green businesses are organizations focused on minimizing their environmental footprint by implementing waste reduction strategies, utilizing RES, and developing a circular economy. They enhance resource efficiency and promote pro-ecological consumption patterns, thereby strengthening competitiveness and accelerating the transition of economies towards green growth [7,8].

Public policy instruments play a significant role in this process. Subsidies, tax incentives, and regulations fostering technological innovation facilitate companies’ decisions to integrate renewable energy into their operations [9]. Companies supported in this way are more likely to implement modern energy models, such as systems combining renewable energy with storage technologies, which optimize distribution and increase the resilience of energy systems [10].

Changing consumer and stakeholder expectations are also increasingly crucial for implementing renewable energy. Customers are increasingly choosing products and services from companies that prioritize the environment and offer climate-friendly solutions [11]. This trend is evident in energy-intensive sectors such as manufacturing and construction, where integrating RES with artificial intelligence or the Internet of Things (IoT) enables improved operational efficiency and a reduced carbon footprint [12].

However, it is essential to remember that implementing renewable energy projects also presents challenges. While the benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions are well-documented, analyzing the entire life cycle of the installation is crucial. The production and disposal of renewable technology components, such as photovoltaic panels or wind turbines, generate environmental burdens that must be considered when assessing their full impact on the ecosystem [13]. This holistic approach enables companies to mitigate the adverse effects of their operations and develop long-term, sustainable development strategies that benefit both the company and the environment.

As a result, RES are gaining dual importance: on the one hand, they serve as a tool for mitigating global environmental problems, and on the other, they are a key element in building green enterprises, which can shape innovative, responsible, and competitive operating models.

While well-designed instruments such as feed-in tariffs, subsidies, or mission-oriented investments play a key role in advancing renewable energy [14,15], their long-term success also hinges on public trust and support. Citizens’ expectations are increasingly shaping the political acceptability of such interventions, especially those aimed at accelerating the green transformation of business. Social legitimacy is not determined solely by economic factors but by values such as environmental concern, perceived fairness, and institutional credibility [16,17]. In countries with a strong legacy of fossil fuel dependence, like Poland, this alignment becomes particularly challenging [18,19]. Without broad societal backing, even technically sound policies may face resistance or reversal—especially if their costs are perceived as unfairly distributed [20,21]. This paper addresses these challenges by examining how the Polish public assesses state support for green enterprises and which social factors influence the perceived legitimacy of such efforts.

Poland represents a particularly relevant case for studying public attitudes toward the state’s role in supporting renewable energy-oriented businesses, due to its unique combination of structural, political, and social factors. Although Poland is an economically developed EU member state, its energy system has long remained dominated by coal, and the pace of decarbonization has been slower compared with Western European countries. Regulatory instability, strong path dependence, and historically low institutional trust create a specific policy environment in which the legitimacy of green transformation measures cannot be taken for granted. At the same time, rapid growth in the share of RES in recent years, the emergence of prosumers, and rising public awareness have intensified societal debates about the direction and fairness of energy policies. These features make Poland a useful lens through which to examine how citizens evaluate governmental support for pro-RES enterprises, and how such evaluations may illuminate broader patterns relevant to both Western (more advanced) and Eastern (more coal-dependent) European countries.

Previous research on the social acceptance of RES has focused primarily on attitudes toward their use in households. Less research has examined how citizens perceive the state’s involvement in supporting businesses implementing pro-environmental solutions. However, the private sector is a key driver of the energy transition and the shift to a low-emission economy. The lack of in-depth knowledge about what society expects from the state to support pro-RES businesses hinders the design of effective and socially acceptable public policies.

This study aims to identify the strength of public support for policies promoting the use of RES by businesses in Poland, and which social groups demonstrate greater or lesser understanding and approval of such initiatives. The analysis includes both classic demographic variables, such as gender, age, education level, income, and place of residence, as well as experiences and plans related to the use of RES. This enables us to understand how social differences and individual experiences influence attitudes toward the state’s role in the green transformation of the economy.

This study offers a new perspective on the social dimension of the energy transition by moving beyond the dominant focus on household-level acceptance and examining the societal legitimacy of state-led support for green-oriented enterprises. While previous studies have extensively explored public attitudes toward the use of RES in private homes, far less attention has been paid to how citizens evaluate policy instruments directed at businesses—despite their central role in accelerating decarbonization, fostering technological innovation, and shaping the broader institutional environment of the energy transition. The theoretical construct developed in this study enables a coherent measurement of public expectations regarding diverse support instruments—financial (e.g., tax incentives), informational (e.g., educational campaigns, eco-labels), and symbolic-institutional (e.g., preferences in public procurement). By integrating insights from research on social legitimacy, institutional trust, and policy acceptability, the study extends prior knowledge and offers an empirically grounded framework for understanding how different social groups perceive the fairness, desirability, and political acceptability of state interventions aimed at promoting pro-ecological business activity.

At the empirical level, the article presents nationally representative data for Poland, which enables the identification of the social cleavages shaping support for pro-RES business policies in a country undergoing a complex and uneven energy transition. The analysis not only documents the level of support across demographic and experiential groups but also provides evidence on which segments of society enhance or constrain the political feasibility of green industrial policies. This strengthens the empirical contribution of the study by addressing a gap in current research, which rarely examines public attitudes toward state support directed specifically at enterprises.

This study brings a new perspective to the literature on the social dimension of energy transition, shifting the focus from consumer attitudes toward using RES in households to the perception of the state’s role in promoting pro-ecological businesses. The theoretical construct developed in this study enables a consistent measurement of public expectations regarding various support instruments—financial (e.g., tax breaks), informational (e.g., educational campaigns, eco-labels), and symbolic-institutional (e.g., preferences in public procurement).

At the empirical level, the article presents representative data for Poland, enabling us to identify which social groups are more and less likely to support policies that favor pro-RES businesses. The obtained results broaden our understanding of the social determinants of climate policy legitimacy and provide a reference point for designing more inclusive and communicatively effective public instruments.

The article follows a typical structure, consisting of a theoretical, methodological, and empirical section. The theoretical section comprises an introduction and a literature review, which present the context of the energy transition, the role of pro-RES enterprises, and the conceptual foundations of the study. The methodological section describes the research approach, including the design, sample characteristics, and the method for measuring attitudes toward policies supporting RES. The empirical section presents the results of the analyses and their discussion. The article concludes with conclusions, public policy recommendations, and directions for further research.

While previous European public-attitude studies have focused predominantly on household-level adoption of RES and citizens’ willingness to support residential installations, far less is known about how the public evaluates state support for RES-oriented businesses. Existing research, therefore, provides only a partial picture of the social legitimacy of energy transition instruments. This study addresses this gap by shifting the analytical focus from private prosumption to expectations regarding public interventions that target enterprises. By developing a coherent latent construct of attitudes toward pro-RES business policies and examining demographic and experiential differences in a representative national sample, the paper offers a perspective that is largely absent from current European studies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Public Policies Supporting Pro-RES Enterprises

The contemporary energy transition depends heavily on the active role of governments and international institutions. Academic research consistently underlines that well-designed public policies are decisive in shaping the pace and structure of RES development, particularly in the private sector [14,15]. These policies include both direct financial tools—such as subsidies, tax exemptions, or preferential loans—and indirect instruments, including stable regulatory frameworks and market mechanisms that reward innovation.

Investment and operational subsidies help overcome the significant entry barriers that many RES enterprises face. As noted by Mazzucato and Semieniuk [14], early-stage public investment is crucial for guiding the market success of novel green technologies. Among the most impactful mechanisms are feed-in tariffs (FiTs), which provide RES producers with guaranteed electricity prices. Their effectiveness in boosting wind and solar deployment has been particularly visible in Germany, Spain, and Denmark [15]. FiTs are credited with enhancing income predictability and reducing investment risk, especially when implemented alongside complementary measures [22], although their long-term fiscal sustainability remains a topic of debate.

In the U.S., renewable portfolio standards and tradable green certificates create market-based incentives for utilities to invest in clean energy [23]. Meanwhile, mission-oriented investment strategies have gained prominence. Institutions such as Germany’s KfW and Brazil’s BNDES are increasingly viewed not only as financial intermediaries but also as strategic actors that channel capital toward long-term societal goals, including decarbonization [24,25].

These strategies are especially relevant for high-risk technologies, such as algae-based biofuels, which require support throughout the full innovation lifecycle—from R&D to commercialization and market integration [26]. As Mazzucato and Semieniuk [14] emphasize, effective innovation policy often relies on coordinated combinations of instruments tailored to national priorities.

The private sector also plays a growing role in driving renewable energy. Long et al. [10] describe emerging business models that combine renewable generation with energy storage, relying on both policy incentives and entrepreneurial flexibility. Recent studies further emphasize that the long-term viability of these hybrid systems depends on innovative value architectures that can monetize system flexibility and navigate regulatory and market complexities [27]. In China, centralized planning through Five-Year Plans has successfully integrated environmental objectives into national strategies. Lu and Wang [28] report that this alignment has accelerated corporate innovation and deployment of green technologies.

An equally important factor is workforce readiness. Arcelay et al. [12] emphasize that energy transitions require digital, engineering, and cross-sectoral skills—making education and training a vital part of public policy.

Cárdenas Rodríguez et al. [21] provide robust empirical evidence that capital subsidies and FiTs significantly boost private investment, especially in emerging markets. However, their effectiveness varies by context: weak institutions, poor regulatory enforcement, or political instability reduce the impact of instruments like quotas or green certificates.

Further studies from Southeast Asia confirm that policy bundles—rather than single tools—are more effective in encouraging private sector participation [22]. Similarly, Ritzenhofen and Spinler [29] show that regulatory uncertainty can undermine investor confidence, unless offset by long-term and well-calibrated FiT designs.

Poland presents a telling case of both potential and constraint. According to Szulecki [18], while support instruments such as auctions and EU funds were introduced, initial efforts were weakened by policy instability and resistance from the coal sector. Recent years have seen progress driven by EU climate goals, access to recovery funding, and increasing public awareness [7,30]. Still, concerns persist—especially regarding investor trust and the coherence of regulatory frameworks [1,5].

Green public procurement has also emerged as a relevant policy tool. As IRENA [31] notes, integrating sustainability into public tenders fosters market demand for green products and supports domestic innovation.

At the same time, critical voices raise concerns about universal approaches. Darwall [32] warns that international mandates promoting renewable energy may unintentionally limit energy access in developing countries with fragile power grids. Although this view comes from a skeptical think tank, it highlights the importance of aligning policy goals with local socioeconomic contexts.

Finally, the literature draws increasing attention to how RES policy intersects with digitalization and urban resilience. Khrais and Alghamdi [7] find that green e-business models can enhance both environmental performance and social cohesion. Likewise, Zeng et al. [8] demonstrate that decentralized energy systems are crucial for constructing climate-resilient cities.

In conclusion, the success of public policies in supporting RES hinges not only on the choice of instruments but also on their consistency, adaptability, and alignment with institutional and market realities.

In the context of accelerating the energy transition, advanced, integrated clean energy systems that combine generation, storage, and alternative energy carriers are becoming increasingly important. Hydrogen-based technologies, including fuel cell systems—especially high-temperature SOFCs—enabling highly efficient chemical energy conversion, are an example. Simultaneously, integrated thermoelectric desalination systems are being developed, capable of generating energy and producing potable water using low-temperature heat sources. Although these technologies are at various stages of commercialization, their growing presence in public debate is influencing narratives regarding the long-term feasibility of the energy transition and shaping social expectations of the state and businesses. Reference to such solutions enables us to better understand that policies supporting pro-RES enterprises apply not only to mature technologies but also to innovative systems that shape future energy models [33,34].

2.2. Public Expectations and Social Legitimacy in Environmental Policy

Environmental concern is the primary source of social expectations and legitimacy in environmental policy [35]. It can take various forms, ranging from pro-ecological behavior and green consumption to a commitment to environmental protection, or limiting consumption and eliminating air travel. This concern also involves the engagement of institutions or the state in environmental protection, as well as initiatives such as clean supply chains and sustainable development. Moreover, pollution sources from energy production are a significant problem [17]. Pro-environmental behavior can be categorized into various forms, from a passive attitude resulting from the awareness of the importance of pro-environmental actions, through conscious purchasing of goods or services produced from ecological energy or raw materials, loyalty to producers, to active protests in the form of blockades of ships or roads. It should be emphasized that, as consumers increasingly choose green products, green energy is gradually changing cultural norms. Concern for the environment is becoming a cultural norm, not only in the purchase of energy or goods, but also through pro-ecological behavior observed in transportation, construction, and recycling.

It is worth noting that individual behavior exhibits different dynamics in response to various consequences of social changes; there is a shift in the environmental strategy of both government institutions and companies. This shift focuses on producing both profitable and ecologically sound goods [36]. It is worth noting that environmental movements first emerged in Western European countries over 50 years ago. In central European countries, greater ecological awareness appeared almost 20 years later. Therefore, cultural changes resulting from environmental awareness are less pronounced. It is worth noting that individual behavior exhibits different dynamics in response to various internal and external factors. The more initiatives are undertaken, and the more often individuals express their commitment to pro-ecological activities, the greater the probability they will adopt pro-environmental solutions [37]. It is also worth analyzing whether factors such as age, gender, level of education, or place of residence influence social attitudes. When presenting social expectations and describing social legitimacy in Poland, it is crucial to outline the specifics of Poland’s environmental conditions regarding energy production. Until 2024, Poland was a country where the energy mix was primarily based on coal. According to data collected by the EMBER agency [19], over the past 25 years, the share of coal and gas in the so-called energy mix has decreased from almost 100% to 50.3% (42.7% for coal and 7.6% for gas). The share of renewable energy resources (RES) reached 49.7%, comprising 30.1% from solar energy and 15.4% from wind farms. The state supports coal producers, and labor productivity in mines is among the lowest in the world. However, it is worth noting that traditional energy sources provide stable employment for hundreds of thousands of workers. Therefore, social expectations are also related to the fear of those employed in mines and their surroundings. Thus, the gradual transition from coal is an essential factor influencing social attitudes. Furthermore, it is worth citing IRENA reports [31], which indicate that while the costs of renewable energy resources in Poland are rapidly decreasing, they remain among the highest in the world. Therefore, fear of high energy prices will influence social behavior. The emergence of the middle class has influenced pro-environmental attitudes and awareness, highlighting that the extraction of fossil fuels causes environmental damage around extraction sites and is also considered a key factor in global warming. Poland remains one of the most polluted countries in the European Union.

Therefore, it is necessary to put forward a thesis that social expectations related to ecological innovations should be close to those associated with RES, because their use is innovative and ecological. Social expectations and legitimacy in environmental policy are directly influenced by state policy, institutions, and social norms. Institutions and social expectations are interdependent [16]. Institutions can be formal, resulting from law or external and internal regulations, or informal, resulting from norms or culture [38]. The former originates from state policy and established legal principles, while the latter results from the community’s perception of the institution’s activities and thus responds to social expectations.

Institutions are therefore formally and informally subject to three sources of pressure [39]: regulators (who create the law and can provide support), competitors and other organizations (whose actions should be imitated to mitigate risk), and social factors (which necessitate adaptation to social expectations). Institutions informally build relationships with the governmental (legal), competitive, and cultural environment. Therefore, a symbiosis exists between institutional policy and social expectations. The outcome of this symbiosis may be, among other things, support from the regulator.

It should therefore be assumed that society generally perceives pro-ecological and pro-environmental attitudes in a positive light. This, in turn, makes institutions ready to innovate in this area. An institution can possess social legitimacy if it undertakes actions that are desirable from the perspective of the norms and principles expected by society. When analyzing social expectations regarding environmental policies, it is worth considering the uncertainty concerning the costs of such policies. On the one hand, pro-environmental policies promote innovation and create new job opportunities. However, they pose risks, for example, through the need to incur higher costs associated with purchasing environmentally friendly products and services. For example, these dilemmas are evident in the European debate on developing the automotive industry and the European Union’s pursuit of climate neutrality. This discussion is even more interesting because research [20] has shown that consumers with greater knowledge about RES see more benefits. Therefore, the residents of the old European Union are more convinced than those from countries that joined the Union in this century.

2.3. Demographic Factors Influencing Pro-Environmental Attitudes

Given the dynamic development of the renewable energy market, research on the social determinants of consumer acceptance and willingness to participate in the energy transition is becoming increasingly important. The literature contains numerous studies analyzing the impact of demographic factors, such as age, gender, education, and income, on consumer attitudes towards the environment, including renewable energy solutions [40,41,42]. These analyses are crucial for understanding the social dimensions of the energy transition and provide a basis for market segmentation and for adapting communication and education strategies to specific consumer groups. As mentioned earlier, most studies focus on the conditions for social acceptance of renewable energy in the context of its use in households. Their results confirm that social attitudes towards renewable energy depend on demographic factors; however, the influence of some factors on pro-environmental attitudes and support for RES is often contradictory and context-dependent.

The relationship between income and pro-environmental attitudes is not clear-cut. Some studies indicate that higher incomes are associated with a lower propensity to engage in pro-environmental behavior, particularly in wealthier countries [43,44,45,46]. This may be due to a high, habitual level of consumption and resistance to reducing it, as well as a greater sense of security regarding resource availability among wealthy individuals [44,46]. Other studies, however, indicate that higher incomes may promote pro-environmental behavior, especially when combined with high income satisfaction [47,48]. In the context of renewable energy, higher incomes may increase willingness to pay for and use RES, but this effect is often moderated by perceived benefits, environmental concern, and social norms [49,50]. Ergun and Rivas [51] showed that an increase in income may reduce the share of renewable energy in energy consumption at low income levels, whereas once a certain threshold is exceeded, further increases in income lead to increased use of RES. This suggests that, in the case of low-income households, environmental attitudes and perceived control may be more important than income in predicting RES use [52].

Although higher levels of education generally translate into more environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors, including support for RES, this relationship is also complex and context-dependent. Studies conducted in China, Europe, and the Philippines have shown that more extended education periods increase the likelihood of pro-environmental actions, such as recycling, energy conservation, and a willingness to pay for green products [53,54,55,56]. At the same time, the relationship between education and attitudes towards RES is more diverse. Some studies confirm a correlation between higher education and greater awareness and willingness to consider renewable energy solutions [57,58,59], while others highlight greater complexity and ambiguity. For example, research conducted in the Czech Republic showed that although higher education increases the likelihood of having an opinion on RES, it does not necessarily predict whether that opinion will be positive or negative [60]. Ambiguous results are also reported in Colombia, where there is only weak evidence that environmental education promotes a higher level of environmental awareness, and the relationship between environmental education and understanding of RES is even weaker [61]. In general, higher education tends to promote pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, but its impact on pro-renewable energy attitudes is less direct and may depend on context, curriculum, and other social factors.

The relationship between age and pro-environmental attitudes, including those conducive to the development of RES, is equally complex and context-dependent. Some studies suggest that older individuals exhibit a greater pro-environmental commitment [62,63], whereas younger people tend to express stronger pro-environmental attitudes that do not always translate into concrete actions [62,64]. Regarding attitudes towards RES, younger people are generally more aware of and favorable towards renewable energy, a correlation often linked to higher levels of education and greater access to information [65,66]. Overall, previous studies indicate that age does influence pro-environmental and pro-RES attitudes, but the effect varies in magnitude. The diversity of results from different countries suggests that motivations and the type of behaviors or attitudes measured may depend on the cultural context.

The results of studies conducted to date seem more conclusive regarding gender. Research in various countries indicates that women demonstrate higher environmental concern and stronger pro-environmental attitudes, and are more likely to engage in pro-environmental activities than men [67,68,69,70]. This relationship is observed both in general attitudes towards the environment and in specific behaviors such as recycling, reducing plastic consumption, and supporting environmental policies [68,71]. Studies focusing strictly on attitudes towards RES also show gender differences: women are often more supportive of renewable energy implementation and more sensitive to environmental issues related to energy production and consumption [70,72].

Existing literature also confirms the link between place of residence and pro-environmental attitudes, including support for RES. As with other demographic factors, this link depends on additional elements, among which authors highlight the local context and attachment to the place of residence. Studies show that strong emotional or social ties to the place of residence lead to greater involvement in pro-environmental activities and a more positive attitude towards RES, particularly among residents who feel responsible for their surroundings and the community in which they live, including in the context of adverse environmental impacts [73,74,75,76,77,78]. Local experiences with energy projects and how residents perceive their impact on the landscape and economy also influence attitudes towards RES. Attachment to the regional landscape and community identity can foster both support for and resistance to RES, depending on whether projects are perceived as enhancing or disrupting the character and values of a given place [79,80,81,82]. Moreover, attachment to place may be more critical in rural areas, where social ties and connection to nature are stronger, although it is also relevant in urban areas, especially in terms of social relations [73,78,83].

In line with this body of work, our study focuses on five demographic determinants: age, gender, education, income, and place of residence, as well as experience-related factors that capture current and planned use of RES in households. This combination allows us to examine both who is more supportive of pro-RES business policies and how direct engagement with RES may reinforce or moderate group differences in attitudes.

2.4. Public Attitudes Toward Pro-RES Policies

Value systems, perceptions of benefits and risks, and trust in institutions responsible for the energy transition shape these attitudes. Public attitudes toward pro-renewable energy source (pro-RES) policies refer to the degree of social approval for governmental strategies that promote the development of renewable energy. They represent a declarative evaluation of the legitimacy and desirability of energy policy directions, encompassing both cognitive beliefs and emotional reactions. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior, attitudes toward pro-RES policies are key predictors of behavioral intentions, reflecting the cognitive–normative dimension of support for energy transformation [84].

Public interest and engagement are fundamental to the success of the renewable energy transition. Growing knowledge about renewable sources often results from media coverage and public information campaigns that promote support programs, such as “My Electricity, Clean Air, or Prosumer” [85]. Research indicates that citizens are more likely to accept policies based on incentives and education, but tend to react negatively to restrictive policies, such as carbon taxes and emissions trading systems [86]. Therefore, public perceptions play a key role in determining the feasibility and acceptability of energy policies, as people evaluate potential costs, benefits, and social consequences [87].

Several interrelated factors, including media coverage, educational levels, cultural values, and economic conditions, shape attitudes toward policies that support RES. Favorable media coverage strengthens support for RES, while information focusing on costs or technological limitations can generate skepticism. Education fosters understanding and acceptance of the energy transition, and cultural values and local identity also play a role. In regions traditionally associated with the fossil fuel industry, new RES investments can be perceived as a threat to jobs and heritage. Support increases when renewable energy policies deliver tangible economic benefits, although concerns about job security and high upfront costs remain barriers to full acceptance [88].

Research also indicates that the public is more likely to positively evaluate renewable energy policies than those related to, for example, nuclear energy. Furthermore, citizens prioritize environmental protection and energy security over economic or social factors [89]. Even among renewable energy supporters, the costs of transition influence cautious attitudes toward various policy measures. Public preferences depend on the type of policy, the degree of government intervention, and the perceived fairness and effectiveness of the proposed solutions [90].

In democratic systems, public attitudes have a powerful influence on the pace and direction of energy transition. Strong public support gives politicians the impetus to take ambitious action, while skepticism or divided opinions lead to caution and limited action [84]. In response, governments are increasingly employing participatory processes and transparent decision-making to enhance trust and the long-term legitimacy of their energy policies. Engaging the public through dialog, education, and consultation fosters a sense of shared responsibility, understanding, and sustained commitment to renewable energy initiatives [91]. Open communication and citizen participation strengthen public acceptance, making energy policies socially justifiable and politically feasible [92,93].

2.5. Hypotheses Development

Differences in attitudes toward policies supporting RES (pro-RES) based on demographic factors constitute an important area of research in the social and environmental sciences. Demographic characteristics have already been the subject of numerous studies on attitudes toward RES.

However, the direction and strength of these relationships are not always consistent, and their effects often appear to be context-dependent.

For example, Karytsas and Theodoropoulou [94], reviewing the literature on individuals’ awareness of RES, confirmed the existence of differences between respondent groups based on gender, age, education, the education level of the household head, pro-environmental behavior, type of work, interest in the environment, and technical knowledge. According to their findings, men, younger individuals, and those with higher education demonstrate greater awareness of RES. Individuals with higher incomes are also more aware of the energy transition processes [40].

Similar research was conducted by Szakály et al. [65] in 2019 among a sample of 1002 people in Hungary. They found that overall awareness of RES was higher among better-educated, more affluent individuals, those working in professions requiring intellectual activity, and those who valued a healthy lifestyle and environmental protection. These studies also indirectly indicate that younger individuals had higher awareness levels. Eluwa and Siong [95] emphasize the significant role of education in differentiating attitudes among various demographic segments, suggesting that greater awareness stemming from education fosters more proactive engagement in energy conservation efforts.

Other studies, however, suggest that in wealthier societies, higher income levels may reduce pro-environmental engagement, which can be linked to a high level of consumption and a lower perceived need to change existing habits [43,44,46].

A similar inconsistency can be found in the case of education. While some studies show that individuals with higher education are more aware of and supportive of RES [57,58], others indicate that education increases the likelihood of having an opinion about renewable energy rather than determining whether that opinion is positive or negative [60,61].

Interesting results are also presented by Oh et al. [84], who analyzed attitudes toward policies supporting energy transition—from nuclear power to RES—in a 2019 sample of 1020 respondents in Korea. They confirmed significant differences between sociodemographic groups. Individuals around 40 expressed the highest support, those with higher education, above-average income, and those from higher social classes. In these groups, transitioning to RES was perceived as a desirable direction for energy development. However, support for pro-RES policies declined among individuals for whom energy bills constitute a greater financial burden, indicating that attitudes toward energy transition are strongly linked to respondents’ economic situation and social status.

The above studies suggest that attitudes toward pro-RES policies vary according to demographic factors. However, based on the above as well as the literature review presented in Section 2.3, it can be assumed that although attitudes toward policies supporting RES vary according to demographic factors, the nature of these relationships often depends on contextual variables such as social norms, local experiences, and cultural background. Therefore, the analyses based on the regional context seem to be especially valuable.

This supports the research hypothesis:

H1:

Attitudes toward pro-RES policies vary across demographic groups, including age, gender, education, income, and place of residence.

Just as demographic characteristics shape attitudes toward renewable energy, previous experience with renewable technologies may influence public support for energy policies.

The concept of behavioral transfer suggests that individuals who already engage in ecological practices—such as installing solar panels, using heat pumps, or purchasing green energy—are more inclined to support other sustainable initiatives. Poortinga et al. [96] found that adopting one pro-environmental behavior increases the likelihood of adopting other pro-environmental behaviors. This dynamic is often linked to the development of an environmental identity, reinforcing long-term ecological preferences. As shown by Otten et al. [97], individuals with stronger environmental self-concepts are more likely to make sustainable choices and to support policies aligned with their values and experiences.

This psychological mechanism is supported by empirical research. Cárdenas Rodríguez et al. [21], using financial microdata from OECD and non-OECD countries, found that direct involvement with renewable energy technologies—mainly when supported by instruments like feed-in tariffs or capital subsidies—improves perceptions of policy effectiveness and encourages investment. Familiarity with such technologies builds trust in public interventions and openness to systemic change.

Regional studies confirm this pattern. For instance, Stanisławska [98], analyzing data from households in Lower Silesia, found that those already using photovoltaic panels were significantly more likely to view public RES policies as legitimate and beneficial. Gajdzik et al. [99] further support these findings in their study on Polish prosumers. They observed that individuals who adopt renewable energy technologies at home tend to exhibit a broader spectrum of ecological behaviors and associate their energy choices with greater energy independence and economic stability. More than half of the surveyed prosumers regularly engage in environmentally friendly practices, suggesting a strong link between personal experience with RES and support for broader sustainability initiatives. Gázquez-Abad et al. [17] demonstrate that increasing consumer environmental awareness prompts firms to integrate sustainability into their long-term strategic planning, particularly in the agri-food sector. This alignment between consumer values and institutional responses further reinforces public support for ecological transformation.

Although Oh et al. [84] did not directly study RES adoption, they showed that support for energy transition policies is strongly linked to institutional trust and perceived fairness—factors often reinforced through personal engagement with renewable technologies.

In a broader policy context, Mazzucato and Semieniuk [14] argue that green transitions succeed when innovation policy aligns with public values. Likewise, Sokołowski and Heffron [100] emphasize that legitimacy, fairness, and real-world relevance are crucial to preventing energy policy failure. From this perspective, individuals using RES at home are more likely to view such policies as just and effective.

Therefore, we propose that household adoption of renewable energy solutions increases support for pro-RES policies—not only due to environmental concern, but through personal experience with the benefits of clean technologies.

With this in mind, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Attitudes toward pro-RES policies differ depending on whether individuals currently use renewable energy solutions at home.

The Rogers model appears to describe the specifics of H3 most effectively. The analysis of the group subject to research included both intentions to use RES in the future and the current situation, i.e., actual use of RES at the time of the study. This allowed for a market-specific approach to H3. Rogers [101] classified consumers in a way that best represented the attitudes of different consumer groups based on their current activities and plans to use new products or services. Five consumer groups have been identified: innovators, early adopters, late adopters, late majority, and laggards. The first two groups warrant a more detailed description. This is because these groups are the first to have consumer experience, and they were the ones who used RES at the time the research was conducted. Five consumer groups have been identified: innovators, early adopters, late adopters, late majority, and laggards. The first two groups warrant a more detailed description. This is because these groups are the first to have consumer experience, and they were the ones who used RES at the time the research was conducted.

Innovators are the first group. It is the least numerous (approx. 2.5%). It is characterized by, among other things, openness to market novelties, a willingness to experiment, and is driven by curiosity or the desire to be first. It is characterized by, among other things, openness to market novelties and a willingness to experiment, driven by curiosity or the desire to be first. People with higher social status and higher income dominate the group of innovators. Innovators are usually better educated and possess greater-than-average knowledge. Pioneers are more likely to take risks and are ideal partners for companies launching new products or services. Innovators are crucial because their attitude determines the chances of a product or service entering the market. Above-average knowledge, above-average risk-taking ability, and curiosity are crucial. These three features allow for experiments that are not necessarily purely commercial. This group is most open to modern technologies, and its attitude to innovation is very positive. Consumers from this group seem to be the natural group that will implement RES.

The next group, significantly larger, is early adopters (one in six consumers is an innovator or early adopter). Unlike innovators, their decisions are guided by the benefits of purchasing a product or service. A completely new aspect is the awareness of decision-making. Individuals in this group observe innovators, monitor information about products or services, analyze risks, and search for the best solution. They are not impulsive in their behavior and can postpone decisions to wait for a more beneficial offer. This group, therefore, represents the most educated customers. An important characteristic is their willingness to share opinions and experiences. This is a group of consumers whose behavior and attitudes determine widespread adoption of a product or service, and whose attitude toward new products is positive. Consumers from this group seem to be a group whose attitudes towards renewable energy will be dictated by economic benefits.

In addition to the traditional Rogers model, the behavioral approach is worth mentioning [102]. Social attitudes depend, among other things, on whether someone has been previously engaged in similar activities. Individuals who have previously been active in ecology or have taken steps towards pro-ecological behavior are more likely to adopt renewable energy. Gajdzik et al. [99] perceive this problem similarly yet differently, assessing the benefits that prosumers derive as much higher. It is these benefits that drive pro-ecological behavior. This is likely due to the third group described by Rogers, which seeks benefits when making ecological decisions.

In addition to the abovementioned approaches, state policy is a significant factor influencing attitudes. Worek et al. [103] drew attention to specific aspects of assessing state policy on energy transformation. An interesting observation is the high level of trust in local governments and communities, as well as a noticeable shift in the perception of environmental awareness.

Barriers to developing distributed energy and RES include extremely low levels of public trust, generally and in the state, and an underdeveloped social capital. According to the authors, knowledge transfer should occur at the local level, involving the participation of leaders.

This allowed us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H3:

Attitudes toward pro-RES policies differ depending on individuals’ plans to adopt renewable energy solutions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

The research presented in this article is part of a broader project dedicated to analyzing citizens’ attitudes toward RES and the social acceptance of instruments supporting the development of the green transition in Poland. In particular, this study focuses on citizens’ opinions regarding public support for enterprises using RES, including such measures as tax incentives, product labeling, educational campaigns, and preferences in public procurement.

The choice of Poland as the country of study was intentional. Poland is among the countries where the energy transition process is still progressing more slowly than in many other EU member states, and the system of incentives and legal regulations promoting the use of RES by businesses remains fragmented and unstable. Unlike in Western European countries, where subsidy and tax relief systems are well developed, in Poland, the scale of RES adoption often depends on citizens’ initiatives, consumer attitudes, and social pressure. Therefore, understanding public opinion on supporting companies that use RES is critical, as it helps assess the potential social acceptance of incentive mechanisms and market preferences.

The study was conducted in the second half of 2024 using the CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing) technique. The research team developed a standardized questionnaire based on previous studies on social acceptance of RES and pro-environmental support policies. The questionnaire was validated and reviewed by experts specializing in the social aspects of renewable energy.

The study was conducted by a specialized research company with a nationwide online panel of respondents. The sample consisted of 1000 adult Polish citizens, selected using quota sampling to reflect the demographic structure of the population by age, in accordance with data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland. The sampling design aimed to ensure social representativeness and thus obtain a reliable picture of nationwide attitudes toward supporting RES. After verifying data quality (including completion time and response consistency), 974 properly completed questionnaires were qualified for further analysis.

3.2. Sample Description

Table 1 summarizes the variables used in the analysis. It includes demographic characteristics of respondents (generation, gender, education level, place of residence, and household net income). Additionally, variables related to the use and plans for RES, as well as attitudes toward RES policies, are included. This allows for identifying relationships between the respondents’ characteristics and their opinions and behaviors regarding renewable energy.

Table 1.

Description of variables used in the analysis.

The selection of demographic variables (gender, age, level of education, income, and place of residence) aligns with established research practices regarding consumer attitudes towards the environment, including renewable energy solutions. These factors are among the characteristics commonly used in research, and previous studies show that they influence environmental attitudes and energy-related behaviors. Furthermore, examining these variables is particularly important because existing literature reports context-dependent effects of sociodemographic factors on support for renewable energy policies. The inconsistent findings across studies underscore the need to reassess the role of these factors in different national settings.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the study sample. It includes information on the demographic structure of the respondents (generation, gender, education level, place of residence, net household income), as well as their experiences and plans related to using RES. The presented numbers and percentages assess the sample’s representativeness and provide a reference point for further statistical analyses. The sample is dominated by Generation X (29.77%), women (51.44%), respondents with secondary education (36.76%), living in towns with up to 20,000 inhabitants (44.35%), and achieving a monthly net household income between PLN 5000 and PLN 10,000 (50.82%). Furthermore, most respondents do not currently use RES at home (79.98%) and do not plan to do so in the next three years (42.09%).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

3.3. Construct Definition and Composition

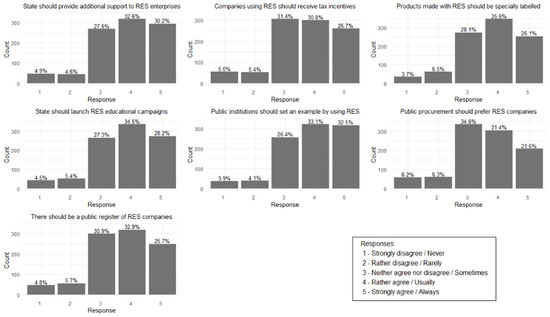

Figure 1 presents the distribution of respondents’ responses to the seven questions comprising the “Public attitudes toward pro-RES policies” construct, assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1—“strongly disagree/never,” 5—“strongly agree/always”).

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses to survey items comprising the RES attitudes construct.

The results indicate that attitudes toward policies supporting RES are mostly positive—responses at levels 4 and 5 predominate, indicating a high level of acceptance for pro-RES activities. Extreme support concerns additional government support for RES enterprises, the introduction of tax breaks for companies using RES, and special labeling of products manufactured using RES. High support was also noted for educational campaigns, led by example by public institutions, and favoring RES companies in public procurement. The most diverse opinions were expressed regarding the maintenance of a public register of enterprises operating in the RES sector. Positive attitudes also dominate in this case. Overall, the results confirm that respondents demonstrate broad acceptance for various forms of supporting pro-RES policies, with particular emphasis on instruments that strengthen enterprises and make it easier for consumers to identify RES-derived products.

3.4. Construct Reliability and Validation

The seven items described above were combined to form the “Public attitudes toward pro-RES policies” construct. Each respondent’s composite score was calculated as the arithmetic mean of their responses to the seven items. Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that the items could be meaningfully combined into a single construct. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in a value of 0.94, indicating a high level of internal consistency. These findings demonstrate that the construct is valid and reliable, providing a solid foundation for subsequent statistical analyses.

3.5. Methods

Because the assumption of normal distribution of the constructed dependent variable, measuring attitudes toward pro-RES policies, was not met, nonparametric statistical tests were used to analyze differences in attitudes across the studied characteristics. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in median attitudes between independent groups of respondents (e.g., generations, genders, RES users, and those planning to use RES). In cases where the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated significant overall differences, the Dunn’s test, a nonparametric post hoc comparison, was used to identify which specific pairs of groups differed in attitudes precisely. These methods enabled the reliable identification of population segments that differed in their level of support for government policies promoting energy transition.

4. Results

4.1. Empirical Results of Public Attitudes Toward Pro-RES Policies

Respondents generally expressed positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies. The overall level of support was moderately high, with a median of 3.86 and a mean of 3.73. Most participants favored initiatives promoting renewable energy, as reflected by the central 50% of scores falling between 3.00 and 4.43. Although individual responses varied somewhat (standard deviation equal to 0.91), the overall pattern indicates broad approval of policies supporting renewable energy development.

To further explore public support for pro-RES policies, attitudes were examined across key demographic characteristics and respondents’ current use and plans to adopt RES. This analysis enables the identification of population segments that are either supportive or opposed to initiatives that promote renewable energy.

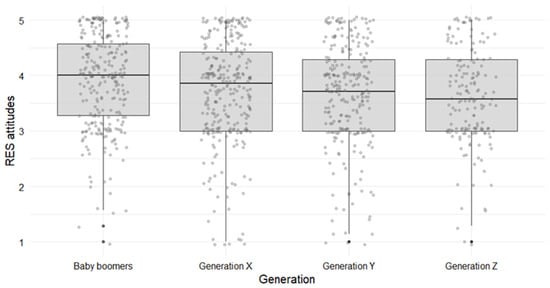

4.2. Differences in Public Attitudes by Age

Figure 2 shows the distribution of RES attitudes by generation. Baby Boomers have slightly higher median RES attitudes scores, which gradually decline through Generation Z. The interquartile range is similar across generations, indicating comparable variability. Older generations tend to hold more positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies.

Figure 2.

Distribution of RES attitudes by generation.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of RES attitudes across different generations, along with the results of the Dunn post hoc test, which show significant differences in attitudes between groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed substantial differences in RES attitudes between the generations. Baby Boomers scored significantly higher than Generations Y and Z, while there was no significant difference between Generation X and the other groups. Support for policies promoting renewable energy is slightly lower among the younger generations (Generations Y and Z), while the older generations, especially the Baby Boomers, are more positive.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by generation.

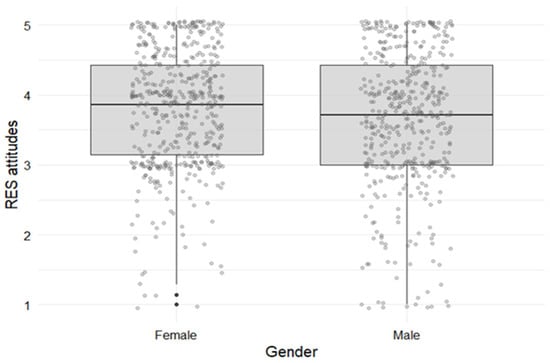

4.3. Differences in Public Attitudes by Gender

In the next step, we examined the effect of gender on RES attitudes. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the RES attitude construct for male and female respondents. The higher mean and median values suggest that women tend to be slightly more positive towards pro-RES policies. Furthermore, women’s attitudes are less dispersed than those of men, suggesting a more homogeneous outlook among female respondents.

Figure 3.

Distribution of RES attitudes by gender.

As shown in Table 4, the results of the statistical tests indicate significant differences in attitudes towards pro-RES policies between men and women. Females scored significantly higher than males. These findings are consistent with the distribution shown in Figure 3. Women tend to exhibit slightly more positive attitudes and greater response consistency, as reflected in their lower standard deviation. Both groups had large sample sizes (female: N = 501; male: N = 473), which provided sufficient statistical power to detect these differences. These results are consistent with previous research, which shows that women tend to exhibit higher environmental concern and stronger support for pro-environmental and RES-related policies.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by gender.

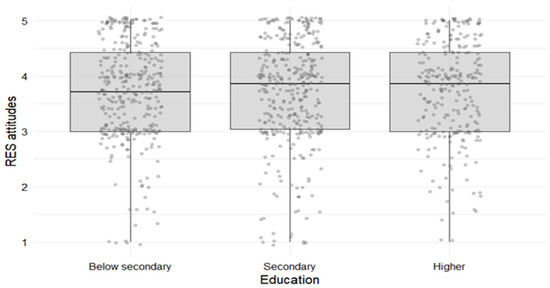

4.4. Differences in Public Attitudes by Education

Figure 4 and Table 5 show the distribution and summary of attitudes toward RES by respondents’ level of education. The interquartile ranges are similar across all three groups, and the spread of responses shows no major outliers or asymmetries that would suggest differences by education. The box plots illustrate that attitudes toward RES are broadly distributed across all education levels, with a concentration of responses around the values 3–4.5. A closer examination of the relationship between means and medians reveals a distinct pattern. In the below-secondary group, the median (3.71) is slightly lower than the mean (3.73), indicating that most respondents rated pro-RES policies below the average. In contrast, the medians (both 3.86) in the secondary and higher education groups exceed the means (3.70 and 3.75, respectively), suggesting that most respondents rated policies above the average.

Figure 4.

Distribution of RES attitudes by education.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by education.

Further statistical analysis supports this observation. There are no significant differences in attitudes toward pro-RES policies among different educational groups. Respondents with below-secondary, secondary, and higher levels of education exhibit very similar mean and median scores (3.73, 3.70, and 3.75 for the mean, respectively), and comparable standard deviations. All groups share the same statistical group, confirming the absence of significant differences. These results suggest that educational attainment does not significantly influence attitudes towards pro-RES policies. However, median values suggest that respondents with a higher level of education may assess pro-RES policies slightly more positively than those with a below-secondary level of education.

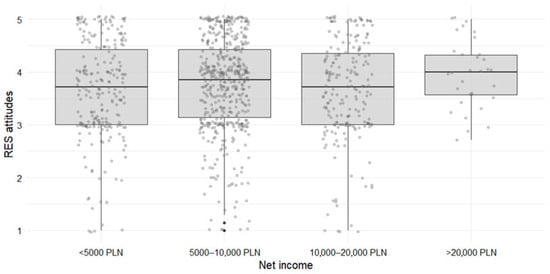

4.5. Differences in Public Attitudes by Net Income

Figure 5 and Table 6 present the distribution and summary of RES attitudes by respondents’ net income. Income consistently emerges as one of the most influential determinants in the deployment of renewable energy sources, as numerous studies demonstrate that stronger economic conditions directly stimulate RES investment and adoption [104,105]. From the box plots, the distributions of RES attitudes among respondents earning less than 20,000 PLN are similar. People who earn 5000 to 10,000 PLN have slightly more positive attitudes towards RES policies, as indicated by the higher median score (3.86 compared to 3.71 for respondents from groups one and three). The smallest group consists of respondents earning above 20,000 PLN. They rate pro-RES policies notably higher, as shown in the graph.

Figure 5.

Distribution of RES attitudes by net income.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by net income.

Although slight variations in mean and median scores exist across income groups, no statistically significant differences are observed. Respondents earning less than 5000 PLN, between 5000 and 10,000 PLN, between 10,000 and 20,000 PLN, and over 20,000 PLN show mean scores of 3.66, 3.77, 3.66, and 3.97, respectively, with comparable standard deviations. The smallest income group (>20,000 PLN) is relatively underrepresented, which limits the statistical power to detect differences. Overall, all groups share the same statistical group, confirming the absence of significant differences in attitudes toward pro-RES policies across income levels. Our findings suggest that the relationship between income and pro-RES attitudes is not straightforward, which aligns with previous research showing mixed effects of income on pro-environmental behavior.

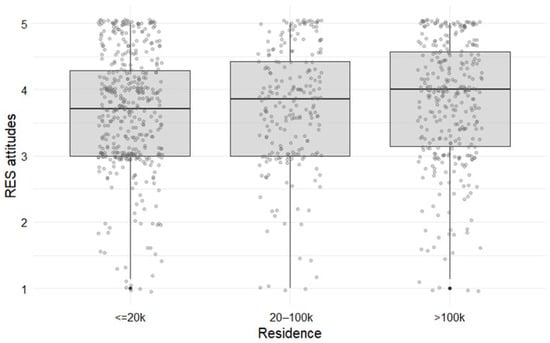

4.6. Differences in Public Attitudes by Size of Place of Residence

Figure 6 and Table 7 show that respondents from larger settlements tend to express more positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies. This is reflected in the gradual increase in mean and median values across residence groups (mean: 3.68 for settlements of ≤20 k, 3.73 for settlements of 20–100 k, and 3. for settlements of >100 k). Figure 6 shows that the box plots for successive settlement sizes are positioned slightly higher, illustrating this upward trend. At the same time, the interquartile range is visibly narrower for respondents living in settlements of up to 20,000 inhabitants. Statistics confirm that pro-RES policy ratings are slightly less varied in this group than among respondents from larger settlements (standard deviation: 0.89 for ≤20 k, 0.90 for 20–100 k, and 0.93 for >100 k). This suggests that attitudes in smaller settlements are more homogeneous, whereas residents of larger towns and cities have a broader range of attitudes toward pro-RES policies.

Figure 6.

Distribution of RES attitudes by residence.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by residence.

Although the small differences in variability are observable, the overall spread of attitudes appears similar across all groups. Figure 6 suggests a slight upward trend across settlement sizes, but statistical tests reveal no significant differences between groups. This indicates that the size of the place of residence does not have a statistically meaningful effect on attitudes toward RES policies.

The analyses presented in Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4, Section 4.5 and Section 4.6 aimed to test Hypothesis H1, which stated that attitudes toward pro-RES policies vary across demographic groups, including age, gender, education, income, and place of residence. The results provide partial support for this hypothesis.

Statistically significant differences were found between generational and gender groups. Older respondents and women expressed more positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies. In contrast, no significant differences were observed across educational levels, income groups, or places of residence. Although slight descriptive trends were noted, such as somewhat higher mean and median values among respondents with higher income or those living in larger settlements, these variations did not reach statistical significance. Overall, the findings suggest that both generation and gender play a meaningful role in shaping attitudes toward RES policies, while other demographic characteristics appear to have no statistically significant impact.

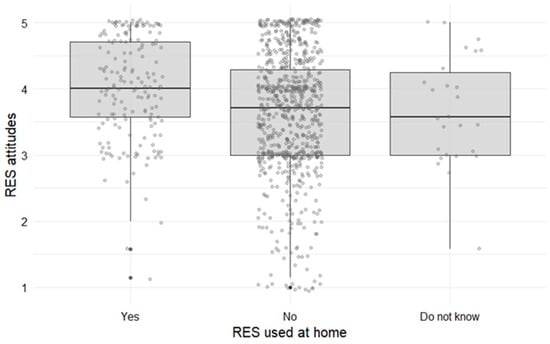

4.7. Differences in Public Attitudes by RES Use at Home

Figure 7 and Table 8 present the distribution and summary of respondents’ attitudes toward RES, depending on whether they use RES at home. The data reveal clear differences between the groups. Respondents who reported using RES at home expressed more positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies, with a mean score of 4.03 and a median of 4.00. Their ratings are also more concentrated, as indicated by a narrower interquartile range, suggesting more consensus within this group. In contrast, those who do not use RES at home showed lower mean and median values (3.67 and 3.71, respectively) and a visibly wider spread of responses. The group also displays more extreme values, which points to greater internal variability in attitudes. Respondents who were unsure whether RES was used in their households reported the lowest mean and median values, suggesting the least favorable attitudes toward pro-RES policies. However, their response distribution is similar to that of respondents who do not use RES. Overall, as shown in Figure 7, personal use of RES appears to be associated with more positive attitudes.

Figure 7.

Distribution of RES attitudes by RES used at home.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by RES used at home.

Figure 7 shows that a large share of respondents declare not using RES at home, despite expressing generally positive attitudes toward renewable energy. This discrepancy indicates a clear opportunity for public policy, as targeted governmental support could help convert these favorable attitudes into higher household-level RES adoption.

The statistical test results in Table 8 confirm that these differences are significant. People who use RES at home scored the highest, indicating a more favorable attitude toward pro-RES policies. Those who did not use RES at home scored significantly lower, while respondents who were unsure did not differ significantly from either group. These findings suggest that direct experience with renewable energy technologies is associated with more positive attitudes toward RES-related policies.

These results support Hypothesis H2, which stated that attitudes toward pro-RES policies differ depending on whether individuals currently use renewable energy solutions at home.

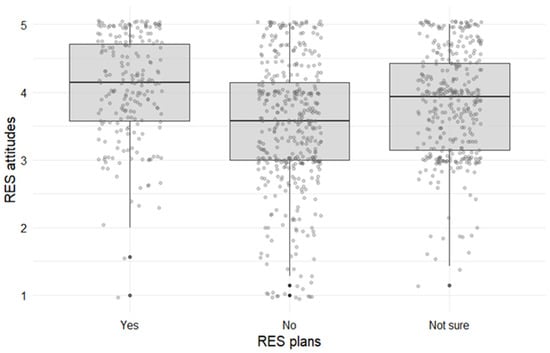

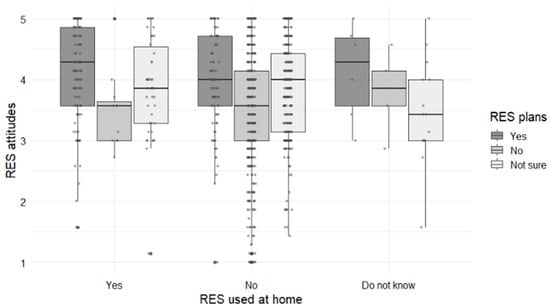

4.8. Differences in Public Attitudes by Planned RES Use

Figure 8 and Table 9 present the distribution and summary of respondents’ attitudes toward RES according to their plans to use them. Depending on future plans for RES use, the distribution of attitudes shows some noticeable differences. The boxplot for respondents planning to use RES is clearly higher than the others, indicating more positive attitudes. Those who do not plan to use RES show weaker attitudes overall. However, it is worth noting that their responses are the most dispersed, with considerable variability and numerous outliers.

Figure 8.

Distribution of RES attitudes by RES plans.

Table 9.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by RES plans.

The data reveal clear and statistically significant differences between groups. Respondents who plan to use RES in the future expressed the most positive attitudes, with a mean score of 4.07 and a median of 4.14. Those who do not plan to use RES reported the lowest mean and median values (3.47 and 3.57, respectively). Respondents unsure about their future RES use fell between these two groups, with mean and median scores of 3.82 and 3.93, and were significantly different from both groups.

These findings suggest that attitudes toward pro-RES policies vary significantly depending on respondents’ future plans for RES. Individuals intending to adopt RES demonstrate the most favorable attitudes, whereas those not planning to use RES are the least supportive, and those who are uncertain occupy an intermediate position. These results support hypothesis H3, which stated that attitudes toward pro-RES policies differ depending on individuals’ plans to adopt renewable energy solutions.

4.9. Combined Effects of Current and Planned RES Use on Public Attitudes

Previous analyses have shown that people’s attitudes toward pro-RES policies differ depending on whether they currently use RES and plan to do so in the future. Until now, these factors have been examined separately. In this section, we analyze attitudes toward pro-RES policies among individuals with different plans for using RES, considering separately those who currently use RES, those who do not, and those who are undecided. Within each group, statistical tests were conducted to compare attitudes toward pro-RES policies. However, it should be emphasized that for the last group (those who are unsure whether they currently use RES) the results are purely indicative and may not accurately reflect reality due to the very small sample sizes.

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of RES attitudes based on whether respondents currently use RES at home and their future plans for RES use. It can be observed that, regardless of current RES use, those who plan to adopt RES in the future exhibit clearly higher attitudes toward pro-RES policies than the other groups. Respondents who do not plan to use RES show weaker support for pro-RES policies, although it is worth noting that this group has the most dispersed responses. Those who are unsure about their future RES use generally exhibit attitudes that fall between those of the other groups. An exception is the group of respondents who are uncertain both about current RES use and plans. However, due to the very small sample size of this group, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 9.

Distribution of RES attitudes by RES used at home and RES plans.

Table 10 presents the basic descriptive statistics and the results of statistical tests comparing attitudes toward pro-RES policies based on planned RES use, separately for users and non-users. Among those currently using RES, individuals planning to continue report significantly more positive attitudes than those who do not intend to continue. Current users not planning further use may be less satisfied with RES, which could lead to a more negative stance toward other RES-supportive policies. Those uncertain about their plans fall between these two groups and do not differ significantly from either in their evaluation of such policies.

Table 10.

Descriptive statistics of RES attitudes by RES used at home and RES plans.

The next group consists of individuals not currently using RES. Approximately half of them plan to use RES or are unsure about future use. Both subgroups exhibit significantly more positive attitudes toward pro-RES policies than those who do not plan to use RES in the future.

Among the surveyed respondents, 26 were unsure whether they currently use RES. In this group, those who plan to use RES in the future or are uncertain also report higher attitudes toward pro-RES policies. However, statistical tests did not reveal significant differences in attitude depending on the plans. It should be noted that the small sample sizes in the respective subgroups (6, 5, and 13) limit the reliability of the statistical tests, and the observed patterns should be interpreted with caution, as they may not accurately reflect the population.

5. Discussion

The results indicate that public support for state-led pro-RES business policies in Poland is generally high, with notable differences across gender, generations, and experiences related to RES.

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, it extends public-attitude research beyond the well-studied domain of household RES adoption, addressing an overlooked but increasingly important dimension of the energy transition: societal expectations regarding state support for green-oriented enterprises. Second, it provides one of the first systematic analyses in Central and Eastern Europe that measures attitudes toward business-focused RES policies using a validated latent construct, rather than the single-item indicators commonly found in previous studies. Third, by comparing demographic groups and individuals with varying levels of personal engagement with RES, the study offers nuanced evidence that helps explain which segments of society perceive pro-RES business policies as legitimate and why.

Based on our survey results, we identified interesting patterns in attitudes toward renewable energy policies in Poland. Comparing these results with those of previous studies enables a more comprehensive understanding of how public acceptance of government actions supporting renewable energy development varies across demographic groups and is influenced by prior experiences.

The comparative analysis of demographic factors revealed a clear and consistent pattern. Among all examined characteristics, only gender and generation significantly differentiated attitudes toward pro-RES policies. Women expressed more positive evaluations than men, and Baby Boomers scored higher than Generation Y and Z. In contrast, education, household income, and place of residence did not produce statistically significant differences, despite minor descriptive trends. These findings suggest that support for state-led RES business policies is shaped more by value- and experience-related factors than by structural socioeconomic characteristics.

Our research results only partially confirmed our hypothesis H1, which assumed that attitudes toward policies supporting RES differed based on demographic characteristics. These differences were found to be significant only for age and gender. However, there were no differences in education, income, or place of residence. This indicates that while demographic factors shape public opinions on pro-RES policies to some extent, not all are significant.

Women and older people expressed the most positive attitudes toward government actions supporting companies using RES. This result aligns with previous studies, which emphasized that women are more likely to exhibit pro-environmental attitudes stemming from a greater concern for the environment and future generations [40,84,88]. In the context of gender, we can therefore speak of a persistent pattern: women, regardless of their level of education or place of residence, are more likely to value actions promoting climate protection and are more likely to support government initiatives in this area.

However, more interesting conclusions emerge when analyzing intergenerational differences. Unlike many previous studies, in which younger people were more likely to declare support for the development of RES [65,106], in this study, older generations—especially Baby Boomers—were more favorable towards pro-RES policies. Older people more often associate the state with a guarantor of order and stability, and therefore are more willing to accept its interventions in the economy and the environment. In contrast, younger generations, who are more individualistic and distrustful of institutions, may be less enthusiastic about top-down policies—even if they support the idea of energy transformation.