Abstract

This study explores a circular economy approach to agricultural waste transformation through an in-depth case study of Taiwan Enzyme Village Company. In response to global challenges related to food waste, resource inefficiency, and environmental degradation, the company has developed a low-energy fermentation system that converts surplus fruits and vegetable residues into a range of value-added products, including enzyme liquids, organic fertilizers, seed paper, and biodegradable packaging. The research employs the BS 8001 Circular Economy Principles as an analytical framework to evaluate the company’s operational model, stakeholder engagement, and environmental contributions. Findings reveal a highly localized and replicable circular system that emphasizes low-carbon production, community collaboration, and innovative reuse of biological resources. The study contributes practical insights for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) aiming to implement circular economy practices within the agricultural sector and highlights strategic pathways for sustainable rural development.

1. Introduction

Agricultural waste has become a critical environmental and economic issue in both developed and developing countries. According to the latest United Nations data, approximately 13% of food is lost from post-harvest to retail stages [1] and an estimated 931 million tonnes—about 19% of global food production—are wasted every year across households, food service, and retail sectors [2]. These updated figures highlight the scale of the challenge and underscore the importance of circular solutions for valorizing surplus agricultural resources. Food waste not only represents a significant loss of resources but also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, soil degradation, and inefficient land and water use [3]. In Taiwan, a significant portion of surplus fruits and vegetables is discarded due to market oversupply or cosmetic imperfections, highlighting the urgent need for more sustainable and value-driven waste management strategies [4]. The circular economy (CE) has emerged as a transformative model that seeks to reduce waste and keep materials in use for as long as possible through reuse, recycling, and resource regeneration [5,6]. Unlike the traditional linear economy model of “take, make, dispose,” circular economy thinking emphasizes systemic change across supply chains, encouraging innovation in product design, resource management, and business models [7]. In the agri-food sector, CE practices can convert agricultural waste into valuable products such as compost, bioenergy, packaging, and functional food ingredients, contributing to climate mitigation and sustainable production [8].

CE applications in East Asia showcase region-specific approaches emphasizing agri-waste valorization and household food waste recycling aligned with sustainability targets. In Japan, residential food waste recycling is fostered through diverse centralised, decentralised, and hybrid composting schemes implemented at municipal levels, involving incentives such as monetary subsidies for composting technologies, knowledge-sharing workshops, and reward programs that encourage participation and sustainable behaviors [9]. These initiatives integrate households as active stakeholders in composting processes, returning nutrient-rich compost to community gardens and farmers, thereby closing nutrient loops and enhancing local circularity. Taiwan’s CE focus in agriculture includes collective packaging waste recycling and incorporation of biowaste into bio-based products, demonstrating industrial symbiosis and enhanced resource efficiency [10]. In the context of developing South Asian countries, Bangladesh illustrates the challenges of food waste management, with prevalent traditional practices like composting and landfilling but increasing interest in advanced valorization techniques, such as anaerobic digestion and integrated biorefineries to produce bioenergy and high-value biochemicals, advocating a shift toward circular bioeconomy models to mitigate environmental impacts and support local economies [11]. Together, these East Asian examples underscore differentiated yet complementary pathways for CE adoption, pivoting on policy frameworks, technological adaptation, and localized stakeholder engagement to convert agri-food waste streams into valuable resources, highlighting scalable models for regional and global sustainability.

Despite growing interest in circular economy frameworks, practical implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) within the agricultural sector remains underexplored. Most existing research focuses on policy frameworks or macro-level models, with fewer studies examining how businesses operationalize CE principles in real-world production environments [12,13]. Furthermore, there is limited documentation of circular economy adoption in East Asian contexts, where traditional agricultural practices and industrial innovation coexist in unique ways.

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating the case of Taiwan Enzyme Village Company, a local enterprise that has integrated circular economy strategies into its enzyme production business. By utilizing surplus fruits and vegetables sourced from farmers and government surplus programs, the company produces enzyme liquids through a low-energy fermentation process and repurposes the resulting residues into organic fertilizer, biodegradable packaging, and other value-added products. The company also engages in carbon footprint certification and environmental education, reinforcing its commitment to sustainability. Through this case study, the paper examines how agricultural waste can be transformed into useful resources using circular economy principles, and evaluates the environmental, economic, and social outcomes of this transformation process. The findings provide new insights into business-led circular innovation in the agri-food sector and offer practical implications for policymakers, entrepreneurs, and sustainability practitioners seeking to promote waste reduction and resource efficiency.

This study contributes to circular economy research by documenting a grassroots, fermentation-based CE model in Taiwan’s rural agri-biotech sector, offering empirical insights into how SMEs adapt CE principles within low-energy biological systems. While most CE literature focuses on industrial-scale systems or policy frameworks, this study provides a micro-level analysis of a small enterprise that integrates waste valorization, product-level carbon accounting, and stakeholder-based sustainability assessment. Such context-specific evidence is limited in East Asia, and this case provides a unique addition by linking CE practices with rural development, technology choice, and brand-building in a community setting.

Recent studies provide strong evidence that food-industry by-products can be converted into high-value biomaterials through microbial processes. Ref. [14] showed that reground pasta waste can be used by purple phototrophic bacteria to produce polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), a family of biodegradable biopolymers relevant to sustainable packaging. Similarly, ref. [15] demonstrated that farinaceous residues can be transformed into volatile fatty acids (VFAs) through acidogenic fermentation, offering pathways for bio-based chemicals and compost-enhancing additives. These examples strengthen the scientific basis for the fermentation-driven valorization model described in this study, where food residues are repurposed into liquid organic fertilizers and other value-added products.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

This section reviews key literature on agricultural waste composition, circular economy principles, and resource recovery strategies. It provides the theoretical foundation to assess how Taiwan Enzyme Village applies circular approaches within both global and local sustainability contexts.

2.1. Composition of Global Agriculture Waste

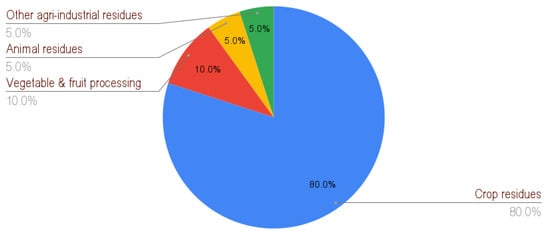

Agricultural waste originates from diverse sources, each presenting unique challenges and resource potentials. This food waste is frequently left in the field or openly burned, contributing to environmental degradation [16]. Some vegetable and fruit waste—including peels, spoiled produce, and unused parts from food processing—is often discarded despite its high nutrient content [17]. And some food waste comprises animal residues (e.g., manure and bedding materials) and other agri-industrial waste, such as leftover seeds and processing water from food factories [18]. Understanding the proportional composition of these waste types is essential for selecting appropriate recycling or reuse strategies. For instance, Taiwan Enzyme Village primarily utilizes vegetable and fruit waste—the second-largest category globally—to produce value-added products such as enzyme liquids and organic fertilizers.

Figure 1 summarizes the global composition of agricultural residues and food processing waste, categorized by source and approximate share of total volume. Crop residues—such as straw, husks, and stalks—constitute the largest category, accounting for around 80% of total agricultural waste. Vegetable and fruit processing waste contributes an estimated 10%, consisting mainly of peels, trimmings, and cosmetically rejected produce. Animal residues, including manure and bedding materials, and other agri-industrial by-products such as wastewater and residual packaging, each account for approximately 5% of the total [18]. This categorization provides a useful framework for identifying suitable recycling or valorization strategies based on waste type and material characteristics.

Figure 1.

Global Agricultural Waste Composition Source: [18].

2.2. Circular Economy and Agricultural Waste Valorization

The CE concept has gained substantial attention over the past decade as a regenerative economic model designed to address environmental challenges and resource scarcity [19]. In the context of agriculture, CE aims to close nutrient and energy loops, minimize external inputs, and reduce waste while enhancing productivity and ecosystem services [20]. Recent studies suggest that agricultural systems are particularly well-suited for CE integration due to the biological nature of resources and the potential to valorize by-products such as manure, crop residues, food waste, and biomass into fertilizers, bioenergy, and new materials [21]. However, the implementation of CE in agriculture remains limited due to technological barriers, fragmented supply chains, and inconsistent regulatory frameworks [13,22,23].

Agricultural waste includes a broad range of organic materials such as surplus fruits and vegetables, post-harvest residues, and food processing by-products. Globally, such waste represents both an environmental burden and an underutilized resource [24]. Effective resource recovery strategies—such as composting, anaerobic digestion, and biotransformation—have shown potential to convert waste into valuable outputs like organic fertilizers, biofuels, bioplastics, and animal feed [25,26,27,28]. Particularly, fermentation-based transformation of surplus produce has emerged as a promising approach for creating functional food ingredients, enzymes, and plant-based health products [29]. This method not only adds value to materials that would otherwise be discarded but also aligns with sustainability goals through energy efficiency and low emissions. The reuse of fermentation residues (e.g., pomace) for agricultural and packaging applications further exemplifies the CE principle of cascading resource use [30,31].

2.3. Circular Economy Enterprises and Local Innovation in Agri-Food Systems

The shift toward CE implementation is increasingly being led by private enterprises that embed CE principles into their operations through process innovation, sustainable product design, and multi-stakeholder collaboration [32]. In the agri-food sector, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often adopt circular business models that involve local sourcing, closed-loop production, by-product reuse, and product life cycle extension [33]. Despite these promising approaches, agri-based SMEs commonly face barriers such as limited access to capital, low public awareness of circular products, and unclear or fragmented regulatory environments [13]. Scholars have called for more detailed case studies to better understand how such firms develop and scale CE practices, especially in emerging or transitional economies. Tools like ISO 14067 [34] and product-level carbon footprint certification can further strengthen market legitimacy and environmental accountability [35]. However, practical pathways for aligning CE strategies with carbon neutrality goals—particularly in agricultural contexts—remain underexplored in the literature.

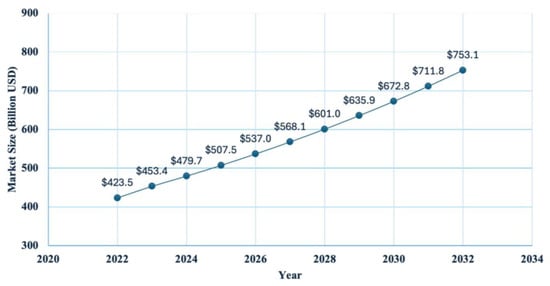

The economic outlook for waste management and circular economy initiatives is expanding rapidly. As illustrated in Figure 2, the global waste management market is projected to grow from USD 453.4 billion in 2023 to USD 711.7 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.80% [36]. This substantial growth is driven by heightened awareness of environmental issues, increasing volumes of e-waste, and the growing need for sustainable resource management across residential, industrial, and agricultural sectors. The trend highlights the critical role of waste valorization—including organic recycling, bio-based production, and zero-waste strategies—as a key component of global circular economy transitions.

Figure 2.

Global Waste Management Market Trend (2022–2032) [35].

In alignment with these global trends, Taiwan has also advanced its CE agenda, particularly under the “5+2 Industrial Innovation Plan,” which promotes green energy, smart machinery, and circular economy development [37]. The island’s agri-food sector is gradually transforming in response to escalating food waste, climate vulnerabilities, and rising expectations for sustainability. A growing number of local firms have explored waste valorization through biotechnology, enzyme fermentation, and organic recycling innovations. Nevertheless, few academic studies have captured how SMEs in Taiwan operationalize CE principles at the grassroots level [38]. In this context, case-based analysis—such as that of Taiwan Enzyme Village—offers valuable insights into the practical, community-driven application of circular strategies. Such enterprises not only reduce agricultural waste and generate value-added products but also work collaboratively with farmers, civil institutions, and local consumers to foster low-carbon production and rural sustainability.

This study differs from existing CE and agri-waste research by documenting a grassroots, fermentation-based CE model in a rural East Asian context, supported by carbon footprint accounting and a stakeholder materiality assessment. Whereas prior studies often focus on large-scale industrial systems or policy-level CE analyses, this case highlights how SMEs operationalize CE principles through low-energy biological processes and diversified revenue structures. This perspective contributes new insights into the micro-level implementation of CE in rural agri-biotech enterprises.

3. Methodology

This study employs a qualitative approach to examine how Taiwan Enzyme Village implements CE practices. The methodology includes three components: (1) multi-source data collection to ensure triangulation; (2) thematic analysis to identify patterns in waste transformation and environmental impact; and (3) application of the BS 8001:2017 CE framework, supported by three analytical lenses. These steps provide a structured basis for evaluating the company’s circular strategies in both theory and practice.

3.1. Data Collection

This study draws upon multiple qualitative data sources collected between January 2023 and June 2024 to ensure triangulation and enhance analytical robustness. The primary dataset is derived from the Taiwan Enzyme Village Circular Economy Implementation Report, finalized in December 2023, which documents the company’s strategies, operational model, production volumes, product innovations, and carbon-related goals between 2021 and 2023. These internal materials provided the foundational understanding of how the enterprise organizes its circular production system and manages waste streams.

To place the case within a broader analytical context, additional information was gathered from academic literature, market research studies, ISO standards such as ISO 14067, and government databases related to carbon emissions and sustainable agriculture. These secondary sources helped situate Taiwan Enzyme Village within global trends in circular economy development and agri-waste valorization.

Further evidence was collected from publicly available materials, including the company’s official website, product certifications, promotional brochures, and public presentations. These sources were cross-verified through independent media coverage and industry platforms to ensure credibility and reduce potential bias. All data were reviewed in accordance with ethical guidelines, with appropriate attribution and explicit permission from the case organization where required.

All data were reviewed under ethical guidelines with proper attribution and the permission of the case organization where required. To enhance data credibility, all company-provided documents—including production records, carbon certification files, and waste input logs—were cross-verified with field visits and publicly available materials. Representativeness was ensured by covering the company’s full operational cycle, including waste sourcing, fermentation, product development, packaging, and stakeholder engagement activities. Interviews and observations were conducted across different time periods between 2023 and 2024, ensuring that the data reflect routine operations rather than isolated events. The combination of internal records, external validation sources, and multi-time-point observations strengthens both the reliability and representativeness of the empirical evidence.

The empirical component of this case study was guided by three operational objectives: first is to document the waste transformation processes and product pathways used by Taiwan Enzyme Village; second, to assess the company’s environmental and operational performance using CE principles and carbon footprint indicators; and finally, to evaluate stakeholder perceptions through a structured materiality assessment. These objectives provided a clear basis for selecting data sources, analytical methods, and evaluation criteria, and ensured alignment between the case evidence and the study’s research aims.

3.2. Data Analysis

The collected materials were analyzed using a manual thematic analysis approach. Through iterative reading and coding, key themes were inductively identified, categorized, and refined. The analysis emphasized patterns and meanings relevant to circular economy implementation and environmental performance.

Five analytical categories structured the interpretation:

Waste Input Types: Agricultural waste materials were categorized based on type and origin (e.g., surplus fruits, vegetable trimmings, fermented residues).

Process Mapping: A stepwise flow of waste transformation-from raw input to final product-was visualized to identify process efficiencies and material recovery patterns.

Output Typologies: The study distinguished between primary products (e.g., enzyme-based liquid products) and secondary outputs (e.g., organic fertilizer, molded packaging, seed paper), offering insights into material cascading and value retention.

Circular Impact Scoring: A qualitative scoring system (scale 1–5) assessed each CE intervention in terms of environmental benefit, technological innovation, economic potential, and feasibility, based on internal reports and published data.

Micro-LCA Simulation: For selected products, simplified product-level emission estimates were conducted following ISO 14067 principles, using carbon emission factors from the Taiwan EPA database. This provided indicative carbon savings from avoiding waste, replacing chemical fertilizers, or eliminating plastic packaging.

3.3. Research Validity and Replicability

To enhance the rigor of the empirical design, the study incorporates several validity safeguards. Internal validity was strengthened by triangulating company reports, public documents, and field-based observations, ensuring consistency across independent data sources. External validity was addressed by clearly defining the boundaries of the case and focusing on processes that are representative of similar rural CE enterprises in Taiwan. Although the study does not test hypotheses, key constructs—such as waste input categories, product outputs, carbon footprint indicators, and stakeholder priorities—were operationalized through structured coding and measurement procedures. Replicability was improved by specifying the analytical steps used in thematic coding, carbon boundary assumptions, and the design of the stakeholder questionnaire.

3.4. Analytical Framework

To systematically interpret the CE practices of Taiwan Enzyme Village, this study adopts the BS 8001:2017 Circular Economy Framework, which outlines six interconnected principles to guide organizations in embedding CE across operations, decision-making, and innovation processes. These six principles—System Thinking, Innovation, Stewardship, Value Optimization, Transparency, and Collaboration—were used to evaluate the alignment of the company’s actions with internationally recognized CE strategies. Figure 3 presents the visual structure of the BS 8001 principles. These six principles serve as a foundation for designing and assessing CE strategies across industries, emphasizing whole-system integration, stakeholder engagement, and multi-value generation.

Figure 3.

BS 8001:2017 Circular Economy Principles.

To operationalize the analytical framework and guide the interpretation of the case, this study applies four interrelated lenses that structure the thematic evaluation. The first lens examines the company’s waste transformation pathways, focusing on how agricultural residues move through successive stages of processing to become diverse value-added outputs. By linking upstream surplus collection with downstream applications such as enzyme liquids, molded packaging, and organic fertilizers, this lens highlights system thinking and resource stewardship through material cascading and recovery.

The second lens classifies the company’s activities into recognized circular economy process typologies. These include: (i) recycling, such as converting enzyme residues into molded pulp packaging; (ii) upcycling, including the development of enzyme-enhanced coffee products; (iii) cascading reuse, illustrated by the multi-stage utilization of fermentation waste; and (iv) biorefinery-oriented models that convert biomass into enzyme solutions. These practices reflect value optimization and demonstrate how materials are cycled through multiple productive uses.

The third lens evaluates carbon and resource impacts through simplified product-level estimations following ISO 14067 methodology, incorporating emission factors from Taiwan’s Environmental Protection Administration. This assessment supports transparency by aligning with the company’s carbon footprint disclosures and third-party verification processes.

Together, these analytical lenses provide a structured basis for understanding how circular economy principles are embedded in Taiwan Enzyme Village’s operations. Section 5 further applies the BS 8001 principles to the company’s practices, drawing on qualitative coding and triangulated data sources.

3.5. Impact–Attention Matrix of Circularity

The questionnaire was designed to serve as a materiality assessment tool to identify the sustainability issues most relevant to Taiwan Enzyme Village’s stakeholders. Its purpose was not to test statistical hypotheses but to complement the qualitative case analysis by capturing stakeholder priorities across economic, environmental, and social dimensions. The results were integrated into the discussion to highlight which areas of circular practice carry the greatest perceived impact and attention, thereby strengthening the relevance and practical applicability of the case findings.

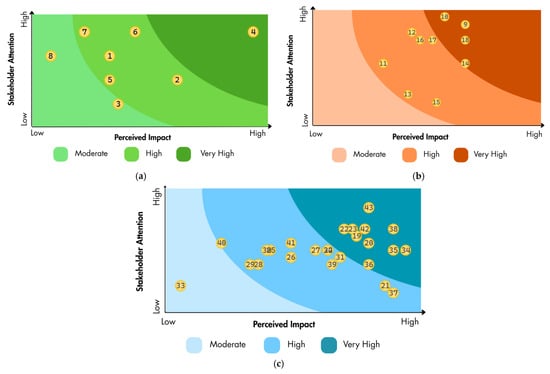

To evaluate the alignment between stakeholder priorities and organizational impact across CE themes, a materiality assessment was conducted using a structured questionnaire-based survey. The assessment followed a dual-axis framework that considers both (1) stakeholder attention and (2) perceived organizational impact for a wide range of sustainability-related topics.

A total of 43 items were included in the questionnaire, categorized into three key circularity dimensions: Economic (Items 1–8), Environmental (Items 9–18), and Social (Items 19–43). Each question asked respondents to rate the importance of the issue (“Stakeholder Attention”) and its level of impact on Taiwan Enzyme Village’s operations (“Perceived Impact”) using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Low to 5 = Very High).

Two stakeholder groups participated in the survey: internal management personnel and external stakeholders such as consumers, suppliers, and local community members. Responses were collected anonymously and averaged to generate position coordinates for each issue on the materiality matrix.

The resulting scatter plots provide a visual representation of priority areas for the company, helping to identify key topics that are simultaneously high in stakeholder attention and operational impact. To improve clarity and granularity, separate materiality matrices were constructed for each dimension (economic, environmental, and social).

3.6. Carbon Footprint Boundary and Data Sources

The product-level carbon footprint estimations follow ISO 14067: 2018 guidelines, using a cradle-to-gate system boundary. The assessment includes raw material sourcing, fermentation and processing operations, packaging, and transportation to the point of sale, while downstream use-phase emissions are excluded due to negligible variation across consumers. Emission factors were taken from the Taiwan EPA greenhouse gas database (2023 version) and supplemented with Ecoinvent 3.9 for materials not covered domestically. Electricity emissions are based on Taiwan Power Company’s 2023 grid factor. Activity data, such as ingredient quantities, energy use, packaging weights, and transport distances, were obtained directly from Taiwan Enzyme Village’s production records. This combination of standardized emission factors and company-specific activity data ensures consistency and transparency in the carbon calculations.

4. Case Description: Taiwan Enzyme Village

Taiwan Enzyme Village serves as the central case for this study, offering a rich example of CE implementation in the agri-biotech sector. As a regionally embedded SME, the company demonstrates how localized innovation, low-energy production, and waste valorization strategies can converge to support both environmental and social sustainability. This chapter provides a detailed account of the company’s background, operational model, and alignment with international CE standards. Through this case, the study illustrates how a circular business can evolve organically from community-based initiatives, while addressing global sustainability goals at the micro-enterprise level.

4.1. Company Background

Taiwan Enzyme Village is a small-to-medium enterprise (SME) based in central Taiwan, founded with the mission of converting agricultural and food waste into high-value bio-based products through natural fermentation. While operating as a commercial entity, the company’s practices are deeply rooted in CE principles, particularly in the realm of waste-to-resource innovation.

Over the years, the enterprise has gained recognition for its integration of traditional fermentation techniques with sustainable waste management, positioning it as a distinctive model within Taiwan’s agri-processing sector. Rather than relying on imported technologies or external formulations, Taiwan Enzyme Village prioritizes local innovation. It has independently developed a portfolio of enzyme-based products using indigenous microbial methods and agricultural by-products. This localized strategy not only creates value from underutilized biomass but also empowers rural communities to develop sustainable products rooted in regional knowledge and materials. In doing so, the company presents a viable pathway toward environmental sustainability and community-based economic resilience.

4.2. Circular Economy Model Overview

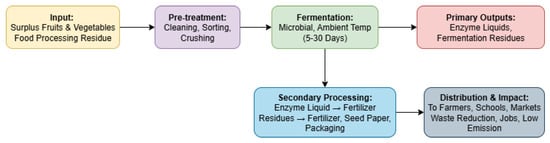

Taiwan Enzyme Village’s circular economy model centers on aerobic and anaerobic fermentation processes that transform surplus or rejected agricultural produce—such as fruit peels, vegetable trimmings, and fermented liquids—into a range of value-added products, including enzyme-based liquid supplements for agricultural and household use; organic biofertilizers; eco-friendly cosmetic ingredients; and compostable materials such as seed paper and molded packaging. The company’s production follows a closed-loop model in which by-products from fermentation are reintegrated into the system through composting, thermal reuse, or packaging innovation, ensuring minimal waste generation. As depicted in Figure 4, the process begins with the sourcing of agricultural residues from local farms and cooperatives. These materials undergo sorting and pre-treatment before being naturally fermented at ambient temperature for 5 to 30 days.

Figure 4.

Circular Process Flow of Agricultural Waste Transformation at Taiwan Enzyme Village.

Two main outputs result from this process. The first is an enzyme-rich liquid that is bottled and distributed as a multipurpose cleaning or soil-enhancing product. The second consists of fermentation residues, which are further processed into organic fertilizers, seed paper, or molded packaging. This system exemplifies material cascading and resource circularity, aligning with the principles of value optimization and low-carbon design emphasized in BS 8001:2017. Its low-energy, community-integrated setup offers a replicable model for rural or semi-urban regions transitioning toward circular economy practices.

Figure 4 provides a visual overview of the company’s circular production system, illustrating how surplus fruits and vegetables move through sequential stages of pre-treatment, natural fermentation, and secondary processing. The diagram highlights the two principal outputs—enzyme liquids and fermentation residues—and shows how these are further transformed into fertilizers, seed paper, and molded packaging. By mapping the complete pathway from input sourcing to final distribution and community impact, the figure clarifies the material cascades and closed-loop flows that underpin Taiwan Enzyme Village’s circular economy model.

4.3. Certification and Standards Alignment

Taiwan Enzyme Village underscores its technological independence through the development and ownership of probiotic strain LE36, for which it holds both domestic and international patents. This proprietary capability safeguards the company’s innovation capacity and product quality, while also offering a model for other SMEs seeking to develop circular economy solutions grounded in localized technological expertise.

To strengthen the credibility and traceability of its circular practices, the company aligns its operations with several environmental standards and frameworks. It applies ISO 14067 for product carbon footprint assessment, conducting carbon accounting for selected products, particularly those marketed as “zero-waste” or “carbon-smart.” Although not formally certified under BS 8001, the company structures its processes around the standard’s core principles, including transparency, value optimization, and stewardship. In addition, Taiwan Enzyme Village complies with relevant Taiwanese environmental and food safety regulations governing enzyme-based consumer goods and organic fertilizers.

Through this combination of proprietary innovation, regulatory compliance, and alignment with internationally recognized sustainability frameworks, Taiwan Enzyme Village demonstrates a credible and scalable approach to circular economy implementation within the agricultural biotechnology sector.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents an integrated evaluation of Taiwan Enzyme Village’s CE performance, drawing upon field data, carbon footprint records, and alignment with BS 8001:2017 principles. Five interrelated dimensions structure this assessment: CE principle application, resource utilization, product valorization, environmental and economic outcomes, and knowledge dissemination. The section is aligned with the analytical lens established in Section 3.

5.1. Application of Circular Economy Principles (BS 8001:2017)

As shown in Table 1, Taiwan Enzyme Village operationalizes the six CE principles of BS 8001 in practical, locally grounded ways. These principles—system thinking, innovation, stewardship, value optimization, transparency, and collaboration—serve as a compass for the firm’s waste valorization, stakeholder engagement, and sustainability commitments.

Table 1.

Application of BS 8001 Principles in Taiwan Enzyme Village.

This table demonstrates the firm’s embedded circular practices and synergistic use of the BS 8001 and ISO 14067 frameworks [39].

5.2. Agricultural Waste Utilization and Production Efficiency

Taiwan Enzyme Village demonstrates an effective and scalable model of agricultural waste valorization within a circular economy framework. Based on 2023 operational data, the enterprise processes approximately 40–60 tons per year of surplus agricultural residues specifically for its enzyme fermentation and circular product lines, sourced from traditional markets, farms, and local community collection programs [40]. These waste streams—comprising fruit peels, vegetable trimmings, and fermentation by-products—are subjected to controlled aerobic and anaerobic fermentation cycles lasting 30 to 90 days, alongside additional raw ingredients used in cosmetic and related product categories.

This biological transformation yields both bio-based liquids and solid derivatives. The system maintains high processing efficiency, with a resource conversion rate exceeding 85% while relying on minimal synthetic additives. Its low-impact design further benefits from ambient-temperature fermentation and greywater reuse, significantly lowering energy and water consumption. Importantly, residual biomass that remains after fermentation is repurposed into compostable packaging materials such as seed paper and molded pulp containers.

By closing resource loops and cascading material use, Taiwan Enzyme Village’s process not only diverts waste from landfills but also enhances material recovery, aligns with BS 8001 principles, and contributes to a low-carbon, resource-efficient production model.

5.3. Product Valorization and Carbon Footprint Reduction

Building on its efficient use of agricultural waste, Taiwan Enzyme Village implements a multi-tiered valorization strategy designed to maximize resource recovery and foster product innovation. This approach is reflected in both the primary fermentation liquids and the secondary outputs derived from residual biomass, all of which align with circular economy principles such as lifecycle thinking, value optimization, and waste minimization.

The company’s core products are enzyme-rich fermentation liquids sold in 750 mL and 50 mL formats. These liquids serve multiple applications, including agricultural use as plant growth enhancers, personal care formulations such as skincare treatments, and eco-friendly household cleaning. Both product sizes have undergone ISO 14067 carbon footprint certification, with calculated emissions of 1.4 kg CO2e for the 750 mL bottle and 200 g CO2e for the 50 mL bottle, demonstrating the firm’s commitment to transparent climate accountability [40]. The carbon hotspot analysis indicates that raw material sourcing accounts for 60.36 percent of total emissions, manufacturing contributes 39.49 percent, and downstream activities such as transport, use, and disposal account for less than one percent.

In addition to its primary offerings, Taiwan Enzyme Village also valorizes fermentation residues into a series of secondary products. Organic fertilizers made from microbial sludge are supplied to organic farms, supporting soil health and sustainable farming practices. Other residues are transformed into biodegradable packaging materials, including seed paper and molded pulp products. These materials are fully compostable and regenerative; when buried in soil, seed paper can germinate and produce new plants, illustrating a circular and biologically restorative design.

Further environmental improvements arise from process innovations within the production system. The company employs high-pressure spiral filling systems to improve material efficiency and incorporates recycled fruit-pulp paper into packaging design. These measures collectively contribute to an overall 3.5 percent reduction in product-level emissions [39], reinforcing the firm’s emphasis on low-carbon design and resource efficiency.

Together, these interconnected valorization strategies constitute a product-service system rooted in sustainability and circularity. By transforming agricultural waste into marketable, low-carbon goods, Taiwan Enzyme Village effectively closes material loops across successive production stages and exemplifies practical circular economy implementation in the agricultural biotechnology sector.

5.4. Environmental, Economic, and Social Outcomes

Taiwan Enzyme Village’s valorization approach extends beyond product development to generate tangible benefits in three key areas:

Environmental Impact: Diverting organic waste from landfills to fermentation mitigates methane emissions, while the substitution of biofertilizers for synthetic nitrogen reduces nutrient pollution risks in surrounding ecosystems. Low-input microbial processes also allow energy and water conservation through ambient temperature operations and greywater reuse.

Economic Performance: In fiscal year 2023, Taiwan Enzyme Village reported a gross profit of NT$19 million, generated through a diversified portfolio that includes enzyme-based consumer products, cosmetic applications, agricultural inputs, regenerative packaging, experiential courses, and community-based educational services [39]. These multiple revenue streams, rather than agricultural waste processing alone, underpin the company’s financial performance. Certifications like ISO 14067 enhance brand credibility and strengthen competitiveness in climate-conscious markets.

Social Contributions: Taiwan Enzyme Village’s social impact is demonstrated through direct employment creation, rural revitalization activities, and community-oriented programs. In 2022, the enterprise purchased 83,353 kg of government-commissioned surplus fruits and vegetables and 673 kg of additional produce, enabling farmers to avoid losses and reducing the company’s procurement costs by NT$416,765. The enterprise currently employs 12 production personnel and plans to recruit more than 10 additional technicians as part of its upcoming facility expansion, supporting local job creation and encouraging youth to return to agricultural work.

The company also undertakes extensive social-welfare efforts, including organizing community events such as the “One-Day Tour of Picking Lotus Roots”, hosting free public film screenings to promote local agricultural narratives, and donating masks, enzyme liquids, soaps, and essential supplies to hospitals and social-welfare organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. It collaborates with NGOs to donate proceeds from market stalls to disadvantaged children and sponsors local road races, cycling tours, and cultural activities. These actions illustrate the company’s role as an anchor institution in the region, contributing to local resilience, social cohesion, and community well-being.

Taiwan Enzyme Village functions as a regional living lab for circular economy education, engaging schools, NGOs, universities, and community groups through hands-on learning and outreach activities. These initiatives support BS 8001’s emphasis on systemic learning and help disseminate CE innovation in rural Taiwan. Table 2 summarizes the core outcomes of the company’s circular economy model across six dimensions.

Table 2.

Summary of Circular Economy Outcomes at Taiwan Enzyme Village.

The outcomes summarized in Table 2 illustrate how Taiwan Enzyme Village integrates environmental, economic, social, and educational objectives into a coherent circular economy model. By combining product innovation, community engagement, and transparent governance practices, the company demonstrates that rural enterprises can advance CE principles while delivering tangible benefits across multiple dimensions.

5.5. Case Insights and Global Context

The case of Taiwan Enzyme Village reveals how a small-scale, community-rooted enterprise can operationalize CE principles through biological innovation, low-carbon processes, and inclusive governance. Building upon the BS 8001 framework and ISO 14067 practices, the firm exemplifies regenerative system thinking, localized material cycling, and performance accountability in a rural context [39].

A defining characteristic is its cascading valorization model: agricultural residues are sequentially transformed into fermented enzyme liquids, organic fertilizers, and biodegradable packaging. This closed-loop system reflects the regenerative aims of the CE paradigm and addresses multiple sustainability goals simultaneously—reducing methane emissions, displacing synthetic fertilizers, and creating value-added bio-products with minimal energy input. Unlike linear agro-industrial systems that rely on resource-intensive operations, the village’s fermentation-based processes demonstrate a low-input, high-yield alternative that emphasizes environmental resilience and rural revitalization.

In theoretical terms, Taiwan Enzyme Village aligns with the “restorative biological cycle” in CE literature, where waste is seen not as a burden but as a starting point for continuous material reuse [41]. The partial adoption of ISO 14067 and traceability tools further indicates a growing institutional capacity to monitor and disclose environmental impact—an essential attribute in CE maturity models.

To situate this local model within a broader global context, a comparative review of similar enterprises is presented in Table 3. These examples span multiple continents and include companies such as Lystek (Canada), which valorizes biosolids into fertilizer and biogas; and TCI (Taiwan), which derives functional ingredients from crop by-products. Taiwan Enzyme Village fits within this ecosystem of innovation but distinguishes itself through grassroots engagement and fermentation-based processes, rather than high-tech infrastructure or large-scale industrial systems.

Table 3.

Global Examples of Circular Economy Companies Using Agricultural or Organic Waste.

The case also surfaces challenges faced by rural SMEs in scaling circular innovations. Constraints include reliance on informal waste collection networks, manual operations, limited access to government subsidies, and regulatory ambiguity surrounding bioproduct classification. Nevertheless, enabling factors such as long-term community partnerships, mission-driven leadership, and transparent communication have compensated for these gaps. In summary, the Taiwan Enzyme Village case highlights a replicable, inclusive, and resilient CE pathway. Its value lies not only in technology or profit, but in its demonstration that small firms—especially in the Global South—can lead sustainability transitions through systemic thinking, local empowerment, and material innovation.

5.6. Impact–Attention Matrix Analysis Results

The Impact–Attention Matrix was employed to visually map and compare the relative priorities of sustainability-related issues across the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. By plotting each assessment item according to its perceived impact on Taiwan Enzyme Village’s operations (x-axis) and the level of stakeholder attention it receives (y-axis), the matrix provides a clear framework for identifying which topics require the most strategic focus. Each matrix corresponds to one of the three sustainability dimensions—economic, environmental, and social. The positioning of each topic in the matrices is based on averaged Likert-scale responses (1 to 5) from internal and external stakeholders. The items plotted in each graph offer valuable insights into the strategic alignment and visibility of various circular economy efforts within the Taiwan Enzyme Village context. This approach allows for the recognition of issues that are both operationally significant and of great concern to stakeholders, thereby guiding resource allocation and decision-making. Figure 5a–c present the resulting matrices for all three dimensions, illustrating how the 43 assessment items are distributed across zones of moderate, high, and very high perceived impact.

Figure 5.

(a): Impact–Attention Matrix for Economic Aspects. (b): Impact–Attention Matrix for Environmental Aspects. (c): Impact–Attention Matrix for Social Aspects.

- Economic Aspects (Items 1–8)

In the economic dimension, only community economic contributions (Item 4) appears in the Very High perceived impact zone, indicating it is a top priority with strong stakeholder attention. Most other items fall into the High zone, such as financial performance and climate-related finance (Item 2), anti-corruption policies (Item 6), corporate governance and ethics (Item 1), local procurement strategies (Item 5), and legal actions related to monopoly or antitrust (Item 7), showing substantial importance but slightly lower impact than Item 4. Local employment and wage equality (Item 3) and tax transparency (Item 8) are positioned in the Moderate zone, suggesting they are seen as relevant but comparatively less critical.

- Environmental Aspects (Items 9–18)

Within the environmental dimension, emissions management (Item 10), energy efficiency and renewable energy use (Item 9), and waste reduction and recycling (Item 18) occupy the Very High perceived impact zone, marking them as environmental priorities. The High zone includes items such as sustainable raw material sourcing (Item 14), water resource management (Item 17), pollution prevention (Item 16), and biodiversity and habitat conservation (Item 12), reflecting considerable importance. Meanwhile, environmental compliance (Item 11), life cycle assessment of products (Item 13), and climate change adaptation strategies (Item 15) are in the Moderate zone, suggesting these issues receive moderate attention and perceived impact compared to others.

- Social Aspects (Items 19–43)

In the social dimension, several items—such as employee health and safety (Item 19), product safety and quality (Item 20), customer satisfaction and engagement (Item 22), community engagement and development (Item 23), human rights protection (Item 42), and transparency in communication (Item 43)—are located in the Very High perceived impact zone, indicating critical significance to stakeholders. The High zone contains a broad cluster, including training and development (Item 21), diversity and inclusion (Item 36), fair labor practices (Item 35), supplier responsibility (Item 38), and data privacy (Item 34), reflecting strong but slightly lower prioritization. In contrast, items such as philanthropic activities (Item 33), consumer education (Item 40), volunteering initiatives (Item 41), and cultural heritage promotion (Items 28–30) fall in the Moderate zone, showing moderate perceived impact and stakeholder attention compared to the highest-ranked social topics.

The Impact–Attention Matrix findings provide a strategic lens for identifying priority areas where organizational efforts can deliver the greatest value in alignment with stakeholder expectations. By mapping each item according to both its perceived impact and stakeholder attention, the analysis highlights issues that warrant immediate action and resource allocation, such as community economic contributions, emissions management, and employee health and safety. These insights are particularly valuable for the Taiwan Enzyme Village case, as they inform decision-making on sustainability initiatives, help balance economic, environmental, and social objectives, and guide the integration of stakeholder-driven priorities into long-term circular economy strategies.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how Taiwan Enzyme Village implements a CE model to convert agricultural waste into value-added products through microbial fermentation. Drawing on the BS 8001 framework, the findings show how the company integrates system thinking, value optimization, and stewardship into a practical, low-carbon production model. By redirecting surplus fruits and vegetables into enzyme liquids, organic fertilizers, and regenerative packaging, the enterprise demonstrates how biological processes can support material circularity within a rural context. The case highlights three main insights. First, the company’s multi-output valorization approach illustrates how SMEs can achieve resource efficiency by connecting waste management, product innovation, and community collaboration. Second, the use of carbon footprint accounting and an impact–attention materiality assessment strengthens transparency and helps align environmental actions with stakeholder expectations. Third, the study contributes to CE literature by documenting a grassroots, fermentation-based model that links restorative biological cycles with local economic resilience and brand development in an East Asian setting. Importantly, the results indicate that CE strategies act as a system-level framework that complements, rather than replaces, the role of technological capabilities such as microbial strains, fermentation processes, and product development techniques. The effectiveness of Taiwan Enzyme Village’s model emerges from the interaction between management principles and appropriate technological choices. The impact–attention matrix further identifies priority areas—emissions management, energy use, waste reduction, community economic contribution, and product safety—that can guide SMEs in prioritizing CE initiatives with limited resources. These findings offer practical relevance for rural enterprises seeking to strengthen environmental performance while maintaining economic viability.

This case study has limitations. It focuses on a single enterprise, which restricts generalizability, and the carbon footprint assessment uses simplified boundaries based on available datasets. Future research could compare similar enterprises across different regulatory settings and perform full life cycle assessments to provide more comprehensive environmental estimates. Even with these limitations, this study shows that locally rooted SMEs can play a meaningful role in advancing circular bio-innovation by combining waste valorization, transparent reporting, and community-oriented practices within a structured CE framework. Future research may also examine how policy incentives, financial mechanisms, or digital tools could support the scaling of such rural CE models, enabling better comparison across regulatory and industrial contexts

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-M.H., S.H.L. and A.K.S.; methodology, A.K.S.; software, A.K.S.; validation, Y.-M.H. and A.K.S.; formal analysis, S.H.L.; investigation, S.H.L.; resources, Y.-M.H.; data curation, Y.-M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.-M.H. and S.H.L.; visualization, Y.-M.H. and S.H.L.; supervision, Y.-M.H. and S.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, due to Exempt Review Categories for Human Research (Announcement No. 1010265075).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-92-5-138167-0. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Food Waste Index Report 2024: Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; ISBN 978-92-807-4139-1. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food Waste within Food Supply Chains: Quantification and Potential for Change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-T. Turning Food Waste into Value-Added Resources: Current Status and Regulatory Promotion in Taiwan. Resources 2020, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyal, K. Sustainable Waste Management in the Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Rep. 2023, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarthur, E.; Heading, H. How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change. Ellen MacArthur Found 2019, 1, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Singh, R.; Kamma, S.; Tripathi, M.; Sharma, M. Transformation of Agro-Waste into Value-Added Bioproducts and Bioactive Compounds: Micro/Nano Formulations and Application in the Agri-Food-Pharma Sector. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, A.C.; Ishida, A. An Overview of Residential Food Waste Recycling Initiatives in Japan. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-L.; Wong, F.-M. Recent Developments in Research on Food Waste and the Circular Economy. Biomass 2024, 4, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Ghosh, M.K.; Islam, T.; Bilal, M.; Nandi, R.; Raihan, M.L.; Hossain, M.N.; Rana, J.; Barman, S.K.; Kim, J.-E. Sustainable Food Waste Recycling for the Circular Economy in Developing Countries, with Special Reference to Bangladesh. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in Supply Chain Redesign for the Circular Economy: A Literature Review and a Multiple Case Study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, A.; Palhas, M.; Villano, M.; Fradinho, J. Valorization of Reground Pasta By-Product through PHA Production with Phototrophic Purple Bacteria. Catalysts 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, A.; Palhas, M.; Villano, M.; Reis, M.A.M.; Fradinho, J. Unlocking the Potential of Food Industry By-Products: Sustainable Volatile Fatty Acids Production via Mixed Culture Acidogenic Fermentation of Reground Pasta. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 526, 146633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, N.; Narzari, R.; Gogoi, L.; Bordoloi, N.; Hiloidhari, M.; Palsaniya, D.R.; Deb, U.; Gogoi, N.; Kataki, R. Valorization of Agricultural Wastes for Multidimensional Use. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Najda, A.; Sharma, R.; Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Sharma, R.; Manickam, S.; Kabra, A.; Kuča, K.; Bhardwaj, P. Fruit and Vegetable Peel-Enriched Functional Foods: Potential Avenues and Health Perspectives. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 2022, 8543881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134329-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sverko Grdic, Z.; Krstinic Nizic, M.; Rudan, E. Circular Economy Concept in the Context of Economic Development in EU Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlles-delaFuente, A.; Abad-Segura, E.; González-Zamar, M.-D.; Cortés-García, F.J. An Evolutionary Approach on the Framework of Circular Economy Applied to Agriculture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgilevich, A.; Birge, T.; Kentala-Lehtonen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Pietikäinen, J.; Saikku, L.; Schösler, H. Transition towards Circular Economy in the Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, G.D.A.; De Nadae, J.; Clemente, D.H.; Chinen, G.; De Carvalho, M.M. Circular Economy: Overview of Barriers. Procedia Cirp 2018, 73, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.; Patil, B.; Srinivasaiah, D. Establishing a Circular Economy Framework in the Agro-Waste to Ethanol-Based Supply Chain in Karnataka, India. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1232611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.P.; Liberal, Â.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Ferreira, I.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Fernandes, Â.; Barros, L. Agri-Food Surplus, Waste and Loss as Sustainable Biobased Ingredients: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Kumar, V.; Ganeshan, P.; Rajendran, K.; Giri, B.S.; Gómez-García, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sindhu, R. Sustainable Biorefinery Approaches towards Circular Economy for Conversion of Biowaste to Value Added Materials and Future Perspectives. Fuel 2022, 325, 124846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tong, L.; Guo, Y.; Shu, T.; Li, X.; Bai, B.; Nie, X. Research on Transforming Food Waste into Valuable Products. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Renewable Energy and Development, Chengdu, China, 23–25 April 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 766, p. 012061. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.S.K.; Pfaltzgraff, L.A.; Herrero-Davila, L.; Mubofu, E.B.; Abderrahim, S.; Clark, J.H.; Koutinas, A.A.; Kopsahelis, N.; Stamatelatou, K.; Dickson, F. Food Waste as a Valuable Resource for the Production of Chemicals, Materials and Fuels. Current Situation and Global Perspective. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 426–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Koutinas, A.; Gathergood, N.; Arshadi, M.; Matharu, A. Food Waste: Challenges and Opportunities for Enhancing the Emerging Bio-Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Exploitation of Food Industry Waste for High-Value Products. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Singh, A.; Sharma, R.; Malaviya, P. Conversion of Food Waste into Energy and Value-Added Products: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1759–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Walraven, N.; Stark, A.H. From Food Waste to Functional Component: Cashew Apple Pomace. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7101–7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14067:2018; Greenhouse gases — Carbon footprint of products — Requirements and guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Wu, P.; Xia, B.; Wang, X. The Contribution of ISO 14067 to the Evolution of Global Greenhouse Gas Standards—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Future. 2024. Waste Management Market Research Report Information by Waste Type, Service, End User, and Region—Forecast Till 2032. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/waste-management-market-21342 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- MOEA, (Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taiwan). Taiwan’s 5+2 Industrial Innovation Plan Overview; MOEA: Taiwan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, A.K.; Hong, Y.-M. Circular Economy Implementation in an Organization: A Case Study of the Taiwan Sugar Corporation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS 8001:2017; Framework for Implementing the Principles of the Circular Economy in Organizations. BSI: London, UK, 2017.

- Taiwan Enzyme Village Co., Ltd. Taiwan Enzyme Village 2023 ESG Sustainability Report; Taiwan Enzyme Village Co., Ltd.: Taiwan, China, 2023; Available online: https://enzyvillage.com/index-lang3.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Al-Hamamre, Z.; Saidan, M.; Hararah, M.; Rawajfeh, K.; Alkhasawneh, H.E.; Al-Shannag, M. Wastes and Biomass Materials as Sustainable-Renewable Energy Resources for Jordan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fwusow Industry Co., Ltd. Sustainability Report 2023; Fwusow Industry Co., Ltd.: Taiwan, China, 2023; Available online: https://esg.fwusow.com.tw/download.php?lang=en&tb=1&cid=-1 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Iogen Corporation Cellulosic Ethanol and Advanced Biofuels 2023. Available online: https://www.iogen.com/company (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Lystek International About Lystek 2023. Available online: https://www.lystek.com/about/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Remondis. REMONDIS Sustainability Report 2023; Remondis: Lünen, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.remondis-australia.com.au/fileadmin/user_upload/remondis-australia-2022/11_about/4_sustainability/11.3_REMONDIS_Australia_Sustainability_Report_2023_August2024.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Sistema.bio. Our Impact: Clean Energy and Circular Agriculture; Sistema.bio: Mexico, India, 2023; Available online: https://takachar.com (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Takachar Waste to Value Through Biochar Technology 2023. Available online: https://www.tci-bio.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2023-TCI-SUSTAINABILITY-REPORT-2.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- TCI Co., Ltd. Corporate Sustainability Report 2023; TCI Co., Ltd.: Taiwan, China, 2023; Available online: https://sistema.bio/who-we-are/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).