Abstract

This study develops an indicator system for provincial digital innovation in China from 2012 to 2022, drawing on four dimensions: actors, elements, environment, and outcomes. Its purpose is to identify the spatial evolution of China’s digital innovation network and reveal the mechanisms that drive this process. The findings contribute both to the scientific understanding of digital innovation dynamics and to policy practices aimed at enhancing regional coordination. We measure digital innovation using a modified gravity model, social network analysis, and a temporal exponential random graph model (TERGM). The results show a clear spatial pattern: digital innovation levels are higher in eastern provinces and lower in western regions, with a noticeable north–south divide. Spatial association intensity continues to increase, forming a distribution characterized by dense linkages in the east and sparse connections in the west. The spatial association network evolves steadily over time. Shanghai, Beijing, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian hold dominant positions and are more likely to form ties with other provinces. The network can be divided into four blocks: a two-way Overflow block, a primary beneficiary block, and two broker blocks. Its structure is shaped primarily by chain-like linkages, supplemented by localized closed structures. The network also displays reciprocity, connectivity, cyclicity, and temporal dependence. Its formation is jointly driven by economic development, marketization, and geographic proximity. They also provide practical guidance for regional sustainable development, optimizing innovation resource allocation, and enhancing the efficiency of China’s digital innovation network.

1. Introduction

In recent years, breakthroughs in frontier digital technologies—such as artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing, big data analytics, and blockchain—have catalyzed a new wave of technological transformation [1]. Within this context, digital innovation has emerged as a pivotal driver of the latest technological revolution [2]. By leveraging novel technologies, products, and business models, digital innovation facilitates the realignment and upgrading of production factors and industrial structures, exerting a disruptive impact on the broader socio-economic landscape and becoming a critical determinant of national competitiveness [3].

Digital innovation is broadly defined as the integrated application of both hardware-based digital infrastructures (e.g., Internet of Things devices) and non-hardware digital components (e.g., application programming interfaces) to generate novel products, services, and value propositions [1]. A key enabler of this process is its modular architecture, which supports high-volume data transmission and thereby underpins strategic objectives across industries, organizations, and societal domains. This modularity empowers diverse stakeholders to flexibly recombine digital resources—both hardware and software—enabling the rapid prototyping and deployment of adaptive, scalable, and context-responsive business models aligned with evolving societal needs [4]. Consequently, digital innovation has become a central engine for economic growth and structural transformation in nations worldwide.

While existing literature has accumulated substantial insights into digital innovation and its networked structures, critical gaps remain. Most studies continue to rely on single-dimensional indicators to measure the level of digital innovation, lacking a systematic and multidimensional evaluation framework capable of capturing the complex, multi-layered architecture and underlying mechanisms of digital innovation systems [5].

In the domain of digital innovation network evolution, prevailing methodologies—such as conventional panel regression models or Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP) analyses—are largely confined to static, attribute- and dyadic-level analyses. These approaches are insufficient for modeling the dynamic trajectories of network evolution, let alone uncovering endogenous structural effects and spatiotemporal interaction mechanisms inherent in digital innovation ecosystems [6].

From a spatial scale perspective, extant research predominantly focuses on localized analyses at the urban agglomeration or regional level. There remains a notable absence of systematic investigations that examine the nationwide configuration of digital innovation networks and track the temporal evolution of their “core–periphery” structural dynamics across macro-geographical scales [7].

China offers a compelling institutional laboratory for studying digital innovation within an evolving national innovation system [8]. Under the strategic framework of the “dual-circulation” development paradigm, the Chinese state has actively reshaped institutional arrangements—most notably through the construction of a unified national market—to accelerate digital innovation and secure leadership in frontier technologies [8]. This systemic push has yielded a highly uneven spatial landscape of digital development, characterized by dense cross-regional linkages rooted in industrial chain complementarities and scale-driven agglomeration economies.

The institutional commitment to digital transformation is further codified in key policy documents. The State Council’s 2023 Overall Layout Plan for Building a Digital China explicitly targets “major breakthroughs in digital technology innovation and globally leading application innovation by 2025,” positioning digital innovation as central to China’s ambition to become a “Cyber Power.” Similarly, the 14th Five-Year Plan for Digital Economy Development launches the “Digital Technology Innovation Breakthrough Project,” reflecting a deliberate strategy to lead the next technological revolution through state-coordinated innovation efforts [9].

Critically, China’s approach combines top-down strategic direction with decentralized policy experimentation. Initiatives such as the “East Data, West Computing” infrastructure program, Zhejiang’s “Mountain-Sea” digital enclaves, and “reverse innovation enclaves” established by inland provinces (e.g., Shaanxi and Gansu) in advanced eastern regions exemplify a novel form of spatially distributed innovation governance [10]. These institutional innovations enable peripheral regions to bypass traditional geographic constraints by embedding themselves into core innovation networks—effectively reconfiguring the spatial architecture of the national innovation system. From a theoretical standpoint, this institutionalized experimentation with spatially reconfigured innovation networks highlights the co-evolution of digital technologies, institutional design, and territorial governance. It underscores that addressing spatial inequities in digital innovation requires not only technological diffusion but also the deliberate orchestration of inter-regional collaborative infrastructures [11]. As such, analyzing digital innovation through the lens of spatially embedded network dynamics offers both empirical and conceptual leverage for understanding how state-led innovation systems can foster inclusive, multi-scalar technological advancement—a question of growing relevance beyond the Chinese context [12].

Guided by the “Actor–Element–Environment–Outcome” (A-E-E-O) framework, this study develops a comprehensive, multi-dimensional indicator system to evaluate provincial-level digital innovation in China, encompassing innovation actors, enabling elements, institutional-environmental context, and innovation outcomes. The study investigates how provincial characteristics and network structural factors jointly shape the evolution of digital innovation networks. To this end, interprovincial innovation flows are estimated using an enhanced gravity model, network topology and key hubs are analyzed via social network analysis (SNA), and dynamic network evolution is examined through Temporal Exponential Random Graph Models (TERGMs), capturing endogenous structural effects and exogenous drivers [13]. Empirical results reveal a pronounced core–periphery structure, with hub provinces driving innovation spillovers and peripheral provinces depending on connections to core nodes. TERGM analysis further demonstrates that both structural network mechanisms and provincial characteristics significantly influence tie formation and network evolution over time. This study makes three contributions: (1) advancing digital innovation measurement through a multi-dimensional, system-level framework; (2) integrating spatiotemporal network analysis to uncover structural interdependencies, diffusion pathways, and regional heterogeneity; and (3) applying TERGM to rigorously model dynamic network evolution, offering a methodological framework transferable to the study of innovation networks in other large, institutionally complex economies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the extant literature on digital innovation and innovation networks, situating our study within the broader theoretical discourse and justifying its empirical and conceptual feasibility. Section 3 outlines the research design, including the construction of the A-E-E-O indicator system, data sources, and methodological framework—particularly the integration of modified gravity modeling, social network analysis (SNA), and Temporal Exponential Random Graph Models (TERGM). Section 4 presents the empirical findings, detailing the spatiotemporal evolution of provincial digital innovation levels and the structural dynamics of the interprovincial innovation network. Section 5 discusses the research findings of the article, the limitations of this study, and the directions for future research. Section 6 summarizes the conclusions of the article and puts forward corresponding policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualization of Digital Innovation

Regarding the conceptualization of digital innovation, existing studies primarily fall into three perspectives: the process-oriented view, the outcome-oriented view, and an integrated perspective that combines both. From the process-oriented perspective, digital innovation is regarded as an innovative process in which new products and new production processes are created within the socio-economic system, thereby effectively enhancing production efficiency [14,15]. In contrast, the outcome-oriented perspective defines digital innovation as a process that leverages digital technology innovation and the digitization of physical components to deliver new products and services to society [16,17]. The integrated perspective acknowledges that the interdependence between the process and outcome of digital innovation has become increasingly complex and flexible [18]. Accordingly, some scholars argue that digital innovation consists of three core elements: digital technologies, innovation processes, and innovation outputs. Through digital innovation, digitization is realized, leading to the formation of new economic models or business forms [19].

2.2. Measuring Digital Innovation

Regarding the measurement approaches of digital innovation, they mainly include two types: single indicators and composite evaluation indices. In the case of single indicators, examples include the word count proportion of digital innovation–related keywords in corporate annual reports [20], using whether a firm applies for digital innovation patents within a year as a measure of digital innovation [21], the number of digital economies–related patents owned by a city [22], and the number of jointly filed digital innovation patents between cities [23]. In the case of composite evaluation indices, some scholars have constructed a comprehensive evaluation system encompassing digital embedding, environmental enablement, technological support, and information dependency [24], while others have developed an indicator system from three dimensions: digital innovation support, process, and output [25].

2.3. Impacts of Digital Innovation

Regarding the impacts of digital innovation, existing studies span multiple spatial scales, including firms, prefecture-level cities, urban agglomerations, and provincial regions. Overall, digital innovation can drive enterprises’ digital and intelligent transformation [26], reshape traditional models and processes of innovation and entrepreneurship, and generate new pathways for value creation and distribution [27], thereby fostering new-quality productive forces [28] and promoting high-quality economic development [29]. Some studies have also conducted preliminary explorations from a network perspective—for instance, conducting multi-scale analyses of the digital innovation network in the Yangtze River Delta region [30]; examining the evolutionary characteristics and influencing factors of digital technology innovation networks across three major urban agglomerations [7]; or investigating the impact mechanisms of digital innovation on new product development in manufacturing firms from the perspective of network embeddedness [31].

2.4. Research Gap

Overall, current research on digital innovation remains in its early stages, particularly studies from a network perspective are still insufficiently deep, and investigations into the evolutionary mechanisms of digital innovation networks remain scarce. Although existing studies have conducted certain analyses on digital innovation and its network structure, they still exhibit several limitations. First, regarding the measurement of digital innovation, most studies continue to rely on single indicators to assess the level of digital innovation; comprehensive indicator systems for digital innovation are relatively rare, making it difficult to fully capture the complex systemic characteristics of digital innovation [32]. Second, concerning the evolution of digital innovation networks, conventional methods such as panel regression models and QAP (Quadratic Assignment Procedure) analyses can only examine attributes and relational dimensions, failing to quantitatively depict the evolving spatial patterns, and are inadequate for disentangling endogenous structural effects and spatiotemporal interaction mechanisms within digital innovation networks [33]. Finally, in terms of spatial scale, most studies focus narrowly on urban agglomerations, conducting comparative analyses of single local regions or a few specific areas, thereby failing to reveal the “core–periphery” structural characteristics of digital innovation at the national scale and their evolutionary dynamics [34].

To address these gaps, this study aims to construct a comprehensive, multi-dimensional provincial-level digital innovation measurement framework and employ the Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model (TERGM) to systematically investigate the evolution and driving mechanisms of digital innovation networks. Specifically, this study will: Develop a multi-dimensional measurement framework that reflects the systemic characteristics of provincial-level digital innovation, providing a robust foundation for network analysis. Employ the TERGM to uncover structural dependence effects, endogenous network evolution mechanisms, and the influence of key driving factors on the formation of network ties. identifying the roles and dynamics of core and peripheral provinces within the digital innovation network. By addressing these aspects, this study seeks to advance understanding of both the measurement and network evolution of digital innovation, offering empirical insights for theory development and policy formulation.

3. Research Design

3.1. Construction of an Interprovincial Digital Innovation Indicator System

Constructing a scientifically sound indicator system for digital innovation requires a precise understanding of the concept’s intrinsic connotations. On the one hand, existing studies define digital innovation from process-oriented, outcome-oriented, and integrative perspectives, implying that the evaluation of digital innovation capability must incorporate multiple dimensions—including inputs, processes, and outputs—to ensure objective and comprehensive assessment [32]. On the other hand, mainstream frameworks for evaluating innovation capability typically follow the “threefold” categorization of innovation actors, innovation environment, and innovation outcomes. Building on this prevailing paradigm, this study further disaggregates innovation outcomes into innovation output and innovation performance, thereby establishing a digital innovation indicator system that better reflects the characteristics of the digital economy [35]. The specific element layer and indicator layer are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Digital Innovation Index Evaluation System.

Innovation actors include three aspects: government, enterprises, and research institutions. Innovation elements consist of labor, capital, and technological inputs within the digital industry. Regarding the definition of the digital industry, this study primarily draws on existing literature and selects two sectors from high-tech industries: “electronics and communications equipment manufacturing” and “computer and office equipment manufacturing” [36]. Innovation environment encompasses both hardware and software infrastructure. Hardware infrastructure refers to the scale of construction of new-generation infrastructure. Software infrastructure is assessed across five dimensions: financial environment, demand environment, supply environment, social environment, and market environment. Specifically, the financial environment is measured by the Digital Inclusive Finance Index released by Peking University; the demand environment is measured by total postal and telecommunications business volume; the supply environment is measured by the level of e-commerce development, specifically using the ratio of e-commerce sales to GDP; the social environment is measured by retrieving the frequency of digital economy–related keywords in provincial government work reports via the PKULaw database, thereby capturing policy attention toward the digital economy [37]; the market environment is measured by the ratio of technology market transaction value to GDP. Innovation outcomes encompass short-term benefits and long-term effects. For long-term effects, the level of enterprise digital transformation is measured using a keyword dictionary of “digital transformation”; the corresponding keyword frequency is calculated from listed companies’ annual reports and then aggregated by province of company registration [38].

3.2. Research Methodology

3.2.1. Entropy Weighting Method

The entropy weighting method, as an objective weighting approach, can effectively avoid subjective bias. First, the selected indicators are standardized. Then, the information entropy is calculated. After determining the weight of each indicator, the comprehensive score of provincial digital innovation is obtained by multiplying the weights with the standardized data.

3.2.2. Modified Gravity Model

In measuring spatial association, the gravity model is employed to examine the degree of spatial linkage in digital innovation. Following existing studies [39], the model is modified by using the proportion of the digital innovation index as the gravitational coefficient. The formula is:

In the equation, denotes the intensity of spatial association in digital innovation between provinces and ; is the correction coefficient, defined as the proportion of province digital innovation development scale within the total digital innovation development scale of provinces and ; represents the digital innovation index; denotes population size; denotes GDP; denotes per capita GDP; and represents the spherical distance between the provincial capital cities of provinces and . Based on this, a spatial association matrix is constructed using the modified economic gravity model. To create a binary adjacency matrix for the digital innovation network, a threshold equal to the row-wise mean of the association matrix is applied: a link is assigned a value of 1 if the interprovincial association exceeds the threshold, and 0 otherwise.

3.2.3. Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis (SNA) is employed to systematically examine China’s interprovincial digital innovation network and its structural characteristics. Overall network properties—such as network density and hierarchy—are calculated alongside individual-level metrics—including degree centrality and closeness centrality—to comprehensively characterize the structural features of the digital innovation network. The specific indicators and corresponding formulas are presented in Table 2. Furthermore, blockmodeling is applied to analyze the spatial clustering pattern of the digital innovation network. The network is partitioned into four block types: “primary beneficiary blocks,” “net senders,” “brokers,” and “two-way Overflow” [40], thereby clarifying the functional roles of individual provinces within the network. Additionally, motif-based analysis is conducted to investigate the micro-structural properties of the digital innovation network. In Table 2, the total number of relationships (L) in the interprovincial digital innovation network represents the observed ties, with each tie indicating collaboration between two provinces. These network measures were computed using UCINET. The number of optimal paths was determined via UCINET’s shortest path algorithm, minimizing interprovincial digital innovation differences or cumulative “distance,” while spherical distances were calculated in GIS using the geographic coordinates of provincial capitals.

Table 2.

Indicator Description of Network Characteristic Analysis.

3.2.4. Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model

The Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model (TERGM) treats multi-temporal networks as a single integrated system during simulation, thereby simultaneously accounting for the effects of structural dependence, temporal dependence, actor relationships, and network embedding on the evolution of digital innovation networks [41]. Compared with static ERGMs or QAP analyses, TERGM can explicitly model network dynamics over time and disentangle both endogenous structural effects and exogenous covariate influences, providing a more accurate and nuanced understanding of network evolution [41]. For the observed network at time , denoted as , the probability function is formulated as:

In the above equation, denotes the probability of observing a particular network realization; represents the vector of network statistics included in the model, which capture key structural features of the network; is the parameter vector corresponding to these statistics; and is the normalizing constant that ensures the probability remains within the interval [0, 1].

This study sets the time interval to one year and examines the digital innovation network from 2012 to 2022. The dependent variable is the presence or absence of a linkage between provinces in the digital innovation network: if two provinces are connected, the value is 1; otherwise, it is 0. The explanatory variables comprehensively consider temporal effects, endogenous factors, and exogenous factors, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model Variable.

The specific specifications are as follows: First, structural analysis of the digital innovation network reveals characteristics such as reciprocity, transitivity, and connectivity. Therefore, four variables—edge effect (edges), mutual effect (mutual), two-path effect (towpath), and cyclicity effect (cripple)—are selected to investigate the network’s evolution from the perspective of structural dependence. Second, given that stability (stability) and variability (variability) reflect temporal dependence and align with the dynamic evolutionary nature of the digital innovation network, these are incorporated into the model to capture the network’s evolutionary mechanisms. Third, from the perspective of actor-related effects, sender and receiver effects for each provincial node are considered, focusing on three key factors: marketization level, economic development level, and digital industry agglomeration. Specifically, marketization level is measured using provincial-level marketization indices from the China Marketization Index Database; economic development level is proxied by per capita GDP from the China Statistical Yearbook; and digital industry agglomeration is measured following existing studies [42] by calculating the location quotient based on employment in information transmission, software, and information technology services relative to total urban employment. Finally, under the frameworks of homophily and co-network effects, provinces are categorized into four major regions—Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern—and geographic adjacency among them is analyzed. By explicitly modeling the temporal variation in these covariates and structural effects, the TERGM captures the dynamic influence of evolving provincial attributes and network structure on the development of the digital innovation network across 2012–2022.

3.3. Sample Selection and Data Sources

Due to data availability, this study focuses on 30 provinces in China from 2012 to 2022 (Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan are excluded due to incomplete data). The data are primarily sourced from two channels: (1) Official statistical publications, including the China Statistical Yearbook, China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook, and provincial and municipal statistical yearbooks; (2) Database platforms or websites, including the EPS Data Platform, CNINFO (Juchao Information Network), PKULaw Database, and the China Marketization Index Database. For isolated missing values in the indicator dataset, linear interpolation is applied to fill gaps. The spherical distances between provincial capital cities are calculated using ArcGIS 10.8 software.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Spatial Characteristics of Digital Innovation Levels

4.1.1. Spatial Distribution of Digital Innovation Levels

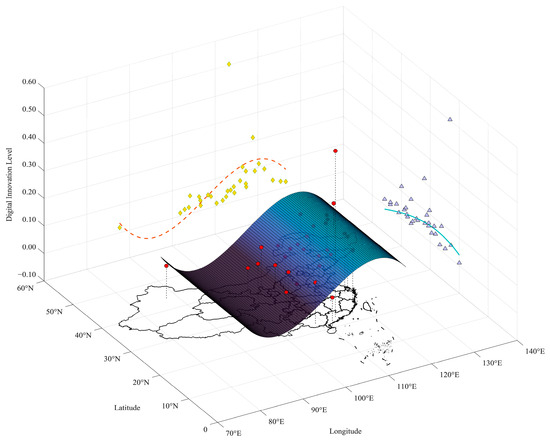

Overall, China’s interprovincial digital innovation level increased from 0.0356 in 2012 to 0.0984 in 2022, indicating that China’s digital innovation system has maintained high resilience despite external technological restrictions, with sustained improvement in innovation capacity. Across the four major regions, the ranking is: Eastern (0.1306) > Central (0.0482) > Western (0.0391) > Northeastern (0.0286), demonstrating the absolute dominance of the eastern region in digital innovation. Using MATLAB 2024a to visualize the spatial distribution trend of interprovincial digital innovation levels across China from 2012 to 2022 (Figure 1), we observe a distinct “southeastern bulge—western depression—tail uplift” pattern. This reflects a clear development gradient characterized by higher levels in the east and lower levels in the central and western regions. In terms of north–south disparity, digital innovation levels exhibit a gradual increase from north to south, with pronounced regional divergence [43]. The underlying causes are as follows: The eastern region benefits from robust economic foundations, a concentration of high-tech industries, and substantial investments in new infrastructure, all of which provide a solid base for digital innovation. In contrast, the northeastern region remains dominated by heavy industry, with relatively rigid institutional frameworks and limited openness; compounded by population outflow and weak market demand, its capacity for digital innovation has been constrained. The central and western regions started later in digital innovation and lag significantly behind the east in terms of talent and other critical resources, yet they are actively exploring development pathways tailored to their local contexts. At the provincial level, the top five provinces in digital innovation are Guangdong (0.5032), Jiangsu (0.2133), Beijing (0.1171), Zhejiang (0.1127), and Shandong (0.0984)—all located in eastern China. The bottom five provinces are Guizhou (0.0186), Xinjiang (0.0186), Inner Mongolia (0.0147), Qinghai (0.0114), and Hainan (0.0108); except for Hainan, all belong to western China. Detailed annual data on digital innovation levels for each province (municipality) and sub-region are available upon request.

Figure 1.

Distribution Trends of Digital Innovation in China’s Provinces from 2012 to 2022. Note: The red dots in the figure represent the level of digital innovation and development; the yellow diamond and purple triangle represent the values projected onto 60° N and 140° E, respectively; the orange curve and blue curve represent the fitting curves in the east-west direction and the north-south direction, respectively; the surface above the map extends from the fitting curve in the east-west direction, which can clearly show the spatial distribution trend of digital innovation.

4.1.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Spatial Association in Digital Innovation

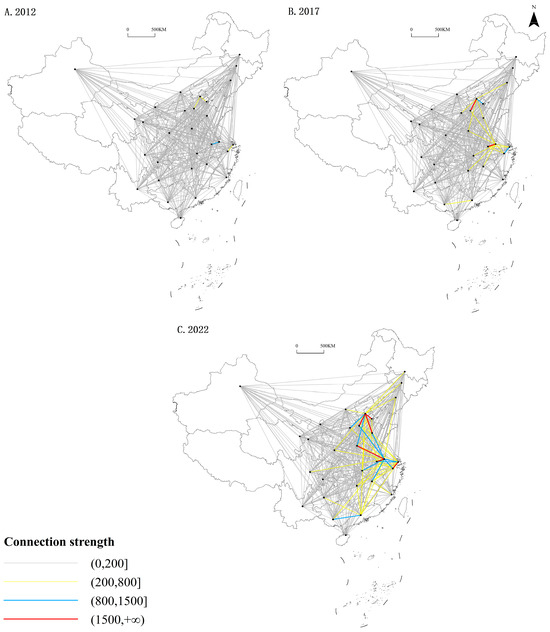

After measuring the intensity of interprovincial digital innovation linkages in China using the modified gravity model, ArcGIS 10.8 software was employed to generate spatial maps depicting the linkage intensity for the years 2012, 2017, and 2022, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Regional Digital Innovation Spatial Association Diagram in China.

It can be observed that China’s interprovincial digital innovation network has evolved toward a multi-core, denser, and more complex structure. The linkage intensity among the eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions has gradually strengthened, shifting from localized linear collaboration centered on the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) and Yangtze River Delta (YRD) regions, to localized areal cooperation, and ultimately to nationwide areal collaboration. This evolution highlights the radiating and driving effects of advantaged regions such as BTH and YRD, as well as the catching-up progress of central, western, and northeastern regions under the promotion of the “Digital China” strategy and regional coordinated development policies [7]. The overall enhancement in regional linkage intensity indicates intensified cross-regional flows of digital resources and growing collaborative activities based on digital innovation and application. The “radiation-diffusion effect” continues to release spatial potential energy associated with digital innovation disparities, thereby amplifying interregional connectivity. Moreover, strong digital innovation linkages are predominantly concentrated in the eastern region, suggesting that digital innovation is more strongly influenced by geographic proximity—for instance, between Shanghai and Zhejiang, or Beijing and Tianjin.

Specifically, in 2012, the overall spatial association of digital innovation was relatively weak, with only strong internal linkages observed within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region, Anhui-Jiangsu, and Shanghai-Zhejiang—exhibiting a “localized collaboration” pattern. In contrast, collaboration levels in central, western, and northeastern regions remained low. By 2017, spatial associations in digital innovation had gradually strengthened. The previously localized collaborations began to diffuse outward, evolving into a regional areal cooperation pattern centered on North China and the Yangtze River Basin. In southern China, initial signs of digital innovation linkage emerged within Guangdong-Guangxi. By 2022, with the continuous refinement of the digital innovation network and the implementation of provincial-level digital economy development plans and policies, the mobility of resources, talent, and technology continued to rise. A new national collaboration framework had taken shape, centered on key provinces and municipalities—including Beijing, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Guangdong—with surrounding regions driving nationwide coordination. The demonstration effect of the interprovincial digital innovation network became increasingly pronounced.

4.2. Structural Characteristics of the Digital Innovation Network

4.2.1. Overall Network Structural Characteristics

The structural characteristics of China’s interprovincial digital innovation network are analyzed using five key metrics: network connectivity, number of ties, network density, network hierarchy, and network efficiency. As shown in Table 4, the network connectivity remains consistently at 1 throughout the period, indicating no isolated nodes and confirming significant spatial linkages among all provinces. The number of ties in the digital innovation network experienced a sharp decline in 2016, followed by a trough and subsequent recovery in 2019. This pattern may be attributed to China’s economic transition into a “new normal” around 2015, compounded by external pressures from the Trump administration’s technological restrictions—particularly in critical “chokepoint” technologies—that temporarily disrupted domestic digital innovation collaboration. Nevertheless, China’s economy demonstrated strong resilience, and the central government increasingly emphasized self-reliance and controllability, especially after the 19 th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which prioritized domestic collaboration as a driver of digital innovation. The trend in network density closely mirrors that of the number of ties. Network hierarchy remains generally low; however, following the State Council’s August 2013 release of the “Broadband China” Strategy Implementation Plan, targeted digital cooperation between eastern and western regions triggered a pulse-like increase in hierarchy [9]. From 2016 onward, hierarchy rose from 0.1290 to 0.2424 and stabilized thereafter, reflecting an overall upward trend. This suggests that a small number of core cities play a dominant role in the network, while simultaneously expanding collaboration channels for peripheral provinces to access core regions. Network efficiency remains relatively stable overall, exhibiting only minor fluctuations.

Table 4.

Overall network structure.

4.2.2. Individual Network Structural Characteristics

We further analyze the specific roles of each province within the network by calculating degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The Centrality of Provincial Digital Innovation Networks in 2022.

Degree centrality is used to assess whether a provincial node occupies a central position within the network. The top five provinces in terms of degree centrality are Shanghai (93.10), Beijing (86.21), Jiangsu (86.21), Zhejiang (65.52), and Fujian (62.07)—all located in eastern China. This indicates that eastern provinces, leveraging their unique economic advantages and well-developed new infrastructure, have become central hubs of digital innovation and exert significant agglomeration (or “siphoning”) effects on other regions. Notably, the three provinces/municipalities of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai all rank among the top five, underscoring the core position of the Yangtze River Delta region within China’s digital innovation network. The bottom five provinces in degree centrality are Ningxia, Shanxi, Liaoning, Anhui, and Shandong. Except for Shandong, all belong to central, western, or northeastern China.

Closeness centrality measures the extent to which a provincial node is less dependent on or controlled by other provinces. The top five provinces in closeness centrality are identical to those in degree centrality: Shanghai (93.10), Beijing (86.21), Jiangsu (86.21), Zhejiang (65.52), and Fujian (62.07). Additionally, Gansu and Hubei—both exceeding the mean value of 63.10—also play central roles within the digital innovation network, indicating efficient connectivity with other provinces. The bottom five provinces in closeness centrality remain Ningxia, Shanxi, Liaoning, Anhui, and Shandong.

Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which a provincial node acts as an “intermediary” or “bridge” within the entire digital innovation network. The top five provinces in betweenness centrality are Beijing (15.19), Shanghai (14.26), Jiangsu (12.11), Zhejiang (5.32), and Fujian (4.97)—all located in eastern China. This indicates that eastern provinces not only occupy core positions in the digital innovation network but also leverage their advantages to facilitate linkages with other regions, playing a strong mediating role that contributes significantly to the overall cohesion and structural evolution of the network.

4.2.3. Block Model Analysis

To clarify the subgroup structure and interrelationships within China’s interprovincial digital innovation network, the CONCOR algorithm in UCINET software was employed. Setting the maximum partition depth to 2 and the convergence criterion to 0.2, the 30 provinces were divided into four blocks in 2022, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Block model of Digital Innovation Network.

Block 1 comprises three provinces: Beijing, Tianjin, and Inner Mongolia—all located in northern China.

Block 2 includes five provinces: Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hubei, and Shanghai; except for Hubei, all are situated in the eastern coastal region.

Block 3 consists of eleven provinces: Heilongjiang, Jilin, Shanxi, Gansu, Liaoning, Ningxia, Shandong, Xinjiang, Hebei, Qinghai, and Shaanxi—primarily concentrated in northeastern China and the Yellow River Basin.

Block 4 also contains eleven provinces: Guangxi, Hunan, Chongqing, Henan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangdong, Anhui, Hainan, Jiangxi, and Sichuan; except for Henan, these are mainly located in the Yangtze River Basin and the Pearl River Basin.

As shown in Table 6, within the digital innovation network comprising 30 provinces, there are 219 spatial association ties in total: 53 are intra-block ties and 166 are inter-block ties. This clearly demonstrates significant spatial association and spillover effects in digital innovation. Specifically:

Block 1 exhibits 15 spillover ties, with 3 internal ties. It receives 42 external ties and sends out 12 external ties. The actual proportion of internal ties is lower than the expected proportion, indicating active exchange between Block 1 and other blocks. Thus, Block 1 is classified as a “Two-way Overflow” block.

Block 2 has 14 internal ties, receives 82 external ties, and sends out 25 external ties. The actual proportion of internal ties significantly exceeds the expected proportion, indicating that this block primarily functions as a primary beneficiary block of innovation flows. Therefore, it is identified as a “Primary beneficiary block” block.

Block 3 accounts for 83 spillover ties, including 14 internal ties. It receives 15 external ties and sends out 69 external ties. The expected proportion of internal ties is higher than the actual proportion, suggesting relatively weak internal innovation collaboration but strong outward spillovers. Hence, Block 3 is categorized as a “Broker” block.

Block 4 contains 22 internal ties, receives 27 external ties, and sends out 60 external ties. Similar to Block 3, its actual internal tie proportion is lower than the expected value, indicating limited internal cohesion but active external linkage. Thus, Block 4 is also classified as a “Broker” block.

These findings highlight the heterogeneous roles played by different regional clusters in China’s digital innovation network, reflecting complex patterns of knowledge diffusion, structural brokerage, and asymmetric dependency across space.

To clarify the relational patterns among blocks, the network density value of the 2022 digital innovation network—0.2517—is used as a threshold. If the density within or between any pair of blocks exceeds 0.2517, the corresponding cell in the density matrix is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned 0. This transforms the density matrix into an image matrix (Table 7).

Table 7.

Density matrix and image matrix.

It can be observed that the diagonal elements of Blocks 1 and 2 in the image matrix are 1, indicating that a “club effect” emerges within these two blocks—i.e., strong internal connectivity and self-reinforcing innovation linkages. Specifically:

Block 1, as a “bidirectional spillover” block, not only maintains internal ties but also exhibits mutually beneficial relationships with other blocks. This may stem from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei economic circle’s concentration of digital innovation resources, which simultaneously radiates influence across the country. Meanwhile, Inner Mongolia—being the province bordering the most neighboring regions—naturally facilitates broader inter-regional interactions.

Block 2, as the “primary beneficiary block” block, demonstrates the highest degree of internal cohesion and primarily receives spillovers from Block 4, along with limited inflows from Blocks 3 and 4. This reflects its role as a core beneficiary within the national network.

Blocks 3 and 4, both classified as “broker” blocks, serve as intermediaries in the digital innovation network. Their primary function is to receive digital innovation ties from Block 1 and subsequently relay or spill them outward to Blocks 1 and 2. Notably, since Blocks 1 and 2 are predominantly located in eastern China, this pattern further underscores the strong agglomeration (or “siphoning”) effect of eastern regions in digital innovation—acting as both sources and sinks of innovation flows, while brokers in central, western, and northeastern regions facilitate their spatial diffusion.

This structural configuration reveals a hierarchical yet interconnected digital innovation ecosystem: core clusters in the east absorb and redistribute innovation, while peripheral broker regions mediate cross-regional knowledge flows, thereby enhancing overall network integration and resilience.

4.2.4. Motif Structural Characteristics

Motif analysis enables the examination of the micro-structural characteristics and organizational patterns within a network. Using the Fanmod software, we measured the triadic and tetradic motifs in China’s digital innovation network for the years 2012, 2015, 2018, 2021, and 2022. Based on frequency, the top five motifs in each period are selected and presented in Table 8. The “ID” column follows the standard motif numbering system used in Fanmod, which is based on the universally adopted classification framework [44]. Each ID corresponds to a unique triadic or tetradic motif, and its specific structural pattern is illustrated in the “Motif” column of Table 8.

Table 8.

Features of Digital Innovation Network Model from 2012 to 2022.

In terms of motif frequencies, motifs numbered 164 and 18,568 appear most frequently and dominate across the observed periods, indicating that these two motifs represent key structural patterns in China’s digital innovation network.

Motif 164 reflects a configuration where collaboration between two provinces relies heavily on a third province acting as an intermediary—i.e., a “broker.” This aligns closely with the block model results, which identify multiple provinces (particularly in Blocks 3 and 4) serving brokerage roles.

Motif 18,568 represents a star-like structure in which one province acts as a central hub, connecting directly to three other provinces in digital innovation linkages. This motif underscores the presence of core provinces that function as pivotal nodes in the network, driving coordination and resource flows.

Together, these dominant motifs reveal that China’s digital innovation network is characterized by both centralized hub-and-spoke dynamics and broker-mediated indirect collaboration, highlighting the coexistence of hierarchical concentration and distributed intermediation in its micro-structure.

From the perspective of motif significance within the network, the evolution of China’s digital innovation association network exhibits a structural pattern characterized by “chain-like structures as the dominant form, supplemented by closed structures.”

Specifically, the frequencies of triadic motif 164 and tetradic motif 18,568 both peaked in 2018. Although their frequencies declined thereafter, they have remained dominant. In the triadic structures, the rising frequencies of motifs 46 and 238 indicate a growing role of closed (i.e., reciprocated or triangular) configurations. In the tetradic structures, motifs 18,568, 18,572, and 2202 consistently rank among the top five in frequency. However, the combined frequency of motifs 18,572 and 2202 never surpasses that of motif 18,568, further confirming that the network is primarily driven by chain-like structures with closed structures playing a secondary role.

This pattern remains pronounced in 2022, where motifs 164, 6, and 18,568 continue to dominate.

Closed structures—typically involving reciprocal or tightly knit collaborations—can transcend administrative boundaries and foster multi-regional, multi-industry innovation communities. However, they may also lead to path dependence and structural lock-in, potentially constraining the network’s diversity and inclusiveness. In contrast, chain-like structures emphasize the vertical transmission of information, technology, and innovation resources across regions. This facilitates sequential coordination and functional specialization among provinces, thereby supporting the high-quality development of the digital innovation network.

4.3. Evolutionary Mechanisms of the Digital Innovation Network

4.3.1. Empirical Results of the TERGM

The Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model (TERGM) is employed to estimate and fit China’s interprovincial digital innovation network from 2012 to 2022, with results presented in Table 9. Smaller values of AIC and BIC, along with a larger Log Likelihood value, indicate better model fit. In Table 9, Model 1 serves as the baseline model, incorporating only the number of edges and exogenous drivers. Models 2, 3, and 4 sequentially introduce structural dependence variables, temporal dependence variables, and additional exogenous covariates, respectively. It can be observed that Model 4 achieves the best overall fit.

Table 9.

Empirical Results of the TERMG of Digital Innovation Network.

From the perspective of structural dependence effects: The edge effect (edges), analogous to the intercept in traditional linear regression, is consistently and significantly negative across Models 1 to 4, indicating that establishing digital innovation collaborations entails non-negligible costs or barriers [45]. The mutual effect (mutual) is significantly positive, suggesting that when province initiates a digital innovation linkage with province j, province j is also likely to reciprocate. This reciprocity plays a crucial role in facilitating the formation and stabilization of the digital innovation network. The cyclic closure effect (ctriple) is consistently and significantly negative, implying that closed triadic structures (i.e., fully connected triangles) are not prevalent. This reflects discontinuities and imbalances in digital innovation collaboration, potentially signaling a “Matthew effect”—whereby already well-connected provinces accumulate further advantages while less-connected provinces lag behind. The two-path connectivity effect (two path) is significantly positive, indicating that provinces frequently act as intermediaries, transmitting digital innovation ties through indirect paths. This suggests that the network relies heavily on brokerage roles rather than exhibiting a clear “multi-core” structure with multiple dense, self-contained clusters.

From the perspective of temporal dependence effects: The stability effect is significantly positive, while the variability effect is significantly negative. This indicates that the evolution of China’s digital innovation network exhibits not only path dependence—where existing ties persist and reinforce themselves—but also path creation, wherein new connections are actively forged despite historical patterns. Digital innovation actors continuously strengthen their capabilities and economic competitiveness through collaboration, thereby overcoming prior barriers to cooperation and establishing novel linkages. Additionally, policy-driven initiatives—such as eastern regions’ support programs for western provinces—may catalyze the formation of new pathways atop the existing network structure, further enriching and refining the architecture of the digital innovation network.

This dual dynamic—simultaneous reinforcement of established ties and intentional creation of new ones—reflects a hybrid evolutionary mechanism that balances institutional inertia with strategic adaptation, enabling the network to evolve in response to both internal innovation momentum and external policy stimuli.

From the perspective of sender and receiver effects:

Sender Effects: Economic development level (pgdp) is significantly negative, indicating that provinces with higher economic development are less likely to initiate digital innovation linkages. This may reflect that economically advanced provinces possess sufficient internal innovation resources to sustain local collaboration, reducing their need to seek external partnerships [46]. Neither marketization level (market) nor digital industry agglomeration (lndigital) exhibits significant effects, suggesting that these factors exert limited proactive influence on driving interprovincial innovation cooperation. In other words, higher marketization or industrial clustering does not necessarily translate into outward-oriented collaborative behavior.

Receiver Effects: Both marketization level (market) and economic development level (pgdp) show significantly positive associations, implying that provinces with higher marketization levels and stronger economies are more likely to attract incoming digital innovation ties. A mature market environment and robust economic infrastructure facilitate efficient resource allocation and enhance the attractiveness of these regions as partners for innovation collaboration [47]. Digital industry agglomeration (lndigital) remains insignificant, potentially because concentrated digital industries tend to prioritize intra-regional collaboration over cross-provincial linkages—thus limiting their role in attracting external innovation flows.

These findings highlight an asymmetry in the drivers of digital innovation network formation: while developed and marketized regions act as strong “receivers” of innovation ties, they are less inclined to serve as “senders”—a pattern consistent with the notion of “core–periphery” dynamics and self-reinforcing regional advantages.

Homophily measures the probability that provinces with similar attributes within China’s four major regions form digital innovation linkages. As shown in Model 4, the homophily coefficient exhibits a negative relationship but is not statistically significant, indicating that provinces within the same regional group are less likely to collaborate on digital innovation—suggesting the absence of broad-based coordinated development within these regional blocs.

From the perspective of co-network effects, the geographic adjacency coefficient is significantly positive, implying that spatial proximity plays a critical role in facilitating the formation of digital innovation partnerships. Provinces located closer to each other are more likely to establish collaborative ties, reflecting the persistent influence of geographic distance as a key determinant of innovation network structure—even in the context of digitally mediated collaboration.

4.3.2. Model Diagnostics

The robustness of the TERGM framework in analyzing the evolution of China’s digital innovation network is comprehensively confirmed through robustness checks—including MPLE, varying temporal intervals, alternative thresholds, and prediction of the 2022 network—along with goodness-of-fit diagnostics and ROC curve analysis.

- (1)

- Robustness Checks

To assess the robustness of the TERGM estimation, this study employs four alternative specifications:

Method 1: The TERGM is re-estimated using the Maximum Pseudo-Likelihood Estimation (MPLE) method, yielding Model 5.

Method 2: The temporal interval of the network is extended to 2, 3, and 4 years, respectively, generating Models 6, 7, and 8.

Method 3: A new network is constructed using a threshold set at 80% of the row-wise mean of the original adjacency matrix, resulting in Model 9.

Method 4: The model is trained on data from 2012 to 2021 and used to predict the 2022 network structure, producing Model 10.

Table 10 summarizes all robustness checks relative to the baseline Model 4. It can be observed that across all alternative specifications, the estimated coefficients remain highly consistent with those in Model 4 in terms of both sign and statistical significance, confirming the robustness of the findings presented in this study.

Table 10.

Robustness test.

- (2)

- Goodness-of-fit test

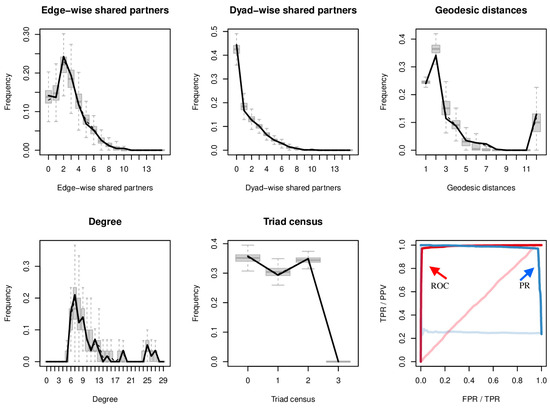

To assess the validity and applicability of the TERGM in capturing the observed network structure, a goodness-of-fit (GOF) test is further conducted [41]. We select five key network statistics for comparison: Edge-wise shared partners, Dyad-wise shared partners, Geodesic distances, Degree, Triad census.

Based on Model 4, we simulate 1000 networks and visualize their structural features (Figure 3). It is evident that the observed values of these key network statistics fall predominantly within the interquartile range (box) of the simulated distributions, indicating that Model 4 provides a good fit to the empirical network.

Figure 3.

Results of goodness of fit test (fit within sample).

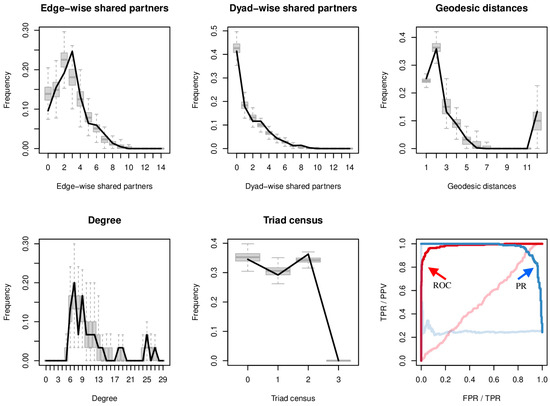

Additionally, in Figure 4, subplot FPR/TPR displays the ROC curve (red line), which lies close to the top-left corner of the plot—a strong indicator of high model discrimination and overall goodness-of-fit.

Figure 4.

Results of goodness of fit test (extra-sample extrapolation).

Furthermore, using the interprovincial digital innovation network from 2012 to 2021 as training data, we predict the 2022 network structure (Figure 4). The results demonstrate that the TERGM-simulated network structure successfully captures the underlying evolutionary mechanisms of the real-world network, confirming its effectiveness in modeling dynamic network processes over time.

These diagnostic checks collectively affirm the robustness, reliability, and predictive power of the TERGM framework in analyzing China’s evolving digital innovation network.

5. Discussion

This study advances the methodology for analyzing large-scale innovation networks by integrating entropy-weighted measurement, modified gravity modeling, SNA, and TERGM, providing a systematic assessment of the evolutionary characteristics and driving mechanisms of China’s interprovincial digital innovation network. The findings reveal pronounced regional disparities and a multi-core network structure, similar to patterns observed in other complex innovation systems, yet the configuration of core provinces and their spillover mechanisms is distinctive. Previous studies indicate that preferential attachment, triadic closure, and link memory play critical roles in the formation of innovation hubs [33].

Moreover, the interplay of endogenous and exogenous factors shapes network formation. Reciprocity, connectivity, and triadic closure strengthen network cohesion, while provinces with high digital industry concentration are more proactive in initiating ties, and highly developed or highly marketized provinces preferentially receive external links [48]. This asymmetry highlights the importance of institutional and industrial heterogeneity in emerging innovation systems.

Compared with international evidence, China’s multi-core network structure demonstrates the effectiveness of regional innovation policies and infrastructure investment in fostering multiple active innovation hubs rather than a single dominant center. These findings enrich the theoretical understanding of digital innovation network evolution, provide empirical support for regional collaborative innovation policy, and underscore the necessity of integrating structural, institutional, and industrial factors when analyzing innovation networks in emerging economies. Despite these contributions, several limitations remain. First, although TERGM offers superior accuracy in capturing temporal network evolution compared to ERGM—effectively addressing the issue of temporal dependence in longitudinal network data—it still operates on binary networks. Future research could extend TERGM to incorporate weighted networks, thereby enhancing precision in modeling the intensity and heterogeneity of interprovincial digital innovation linkages [49]. Second, the digital innovation network structure constructed in this study is based on an aggregated index comprising four dimensions. Future work could evaluate the network structures derived from each individual dimension (e.g., actors, elements, environment, outcomes) and compare them with the overall composite network. Such an approach would help uncover regional disparities in digital innovation across different functional dimensions and facilitate the design of a more balanced, complementary national digital innovation network architecture [50].

Third, while this study focuses on the provincial level—a choice motivated by data availability and comprehensiveness, which enables a holistic assessment of regional digital innovation performance and overcomes prior limitations of narrowly scoped regional analyses—the relatively large spatial scale may obscure fine-grained identification of core nodes or sub-regional hubs. Future research could refine the analytical unit by shifting from composite indices to single-dimensional indicators, such as digital innovation patents, further categorized into design, utility model, and invention patents—or differentiated between foundational versus applied innovation. Moreover, scaling down the analysis to the city level nationwide would allow for a more granular and precise mapping of the spatial hierarchy and structural dynamics within China’s digital innovation network [33].

These extensions would not only enhance methodological rigor but also provide actionable insights for policymakers aiming to foster coordinated, multi-tiered, and spatially optimized digital innovation ecosystems.

6. Conclusions and Policy Suggestions

6.1. Conclusions

This study measures interprovincial digital innovation levels in China from 2012 to 2022 using the entropy weighting method, constructs a spatial association matrix via a modified gravity model, examines the evolutionary characteristics of the digital innovation network through social network analysis (SNA), and investigates its driving mechanisms using a Temporal Exponential Random Graph Model (TERGM). The key findings are as follows:

(1) During the study period, significant regional disparities exist in both the spatial distribution and spatial association of interprovincial digital innovation. Spatially, digital innovation exhibits a clear pattern of higher levels in eastern China and lower levels in central and western regions, with pronounced north–south divergence. The digital innovation network has evolved toward a multi-core, denser, and more complex structure, with provinces and municipalities such as Beijing, Jiangsu, and Shanghai—located in eastern China—serving as core nodes.

(2) Overall, the number of ties, network density, and network efficiency in China’s interprovincial digital innovation network first declined and then increased over time; network hierarchy shows a consistent upward trend, indicating that certain core cities increasingly dominate the network structure. At the individual level, eastern provinces—particularly those in the Yangtze River Delta region—occupy central positions and exhibit stronger connectivity with other regions. Blockmodeling results reveal that the digital innovation network comprises three functional block types: “primary beneficiary block”, “bidirectional spillovers”, and “brokers”. Significant spillover effects exist among these blocks: the “primary beneficiary block” block is concentrated in the Yangtze and Pearl River basins; the “bidirectional spillover” block consists of Beijing, Tianjin, and Inner Mongolia; while the two “broker” blocks are primarily located in central, western, and northeastern China.

(3) The evolution of China’s interprovincial digital innovation network is jointly driven by endogenous and exogenous forces. Among endogenous effects, reciprocity, connectivity, and transitivity facilitate network formation, while provinces exhibit strong temporal dependence—maintaining path dependency while simultaneously engaging in path creation. Provinces with higher economic development levels or marketization degrees are less likely to initiate cooperation, whereas those with higher digital industry agglomeration are more likely to send out ties. Conversely, provinces with higher economic development and marketization levels are more receptive to incoming innovation ties, while those with higher digital industry concentration are less likely to receive external collaborations. Moreover, geographic proximity remains a critical determinant in shaping the formation of digital innovation linkages.

6.2. Policy Suggestions

In summary, China’s provincial digital innovation exhibits significant regional disparities and structural characteristics in its spatial patterns, interconnection structures, and evolutionary mechanisms. These findings not only uncover the internal drivers and external influencing factors of digital innovation but also provide practical insights for enhancing regional coordination, optimizing the allocation of innovation resources, and promoting the efficient functioning of innovation networks. Building upon these conclusions, we propose the following policy recommendations to further strengthen China’s digital innovation capacity and advance high-quality regional development.

(1) Deepen multi-level coordination mechanisms to enhance the resilience of spatial interconnection networks. The spatial network of provincial digital innovation in China is characterized by a functional division among “primary beneficiary,” “two-way overflow,” and “broker” blocks, highlighting the need for cross-tier coordination to bolster network resilience. Regional digital innovation alliances should be established with core primary beneficiary regions—such as the Yangtze River Delta—at the center, leveraging the strategic layout of computing-power network hubs to deeply integrate the R&D capabilities of eastern provinces with application scenarios in central and western regions. For example, drawing on Shandong’s dual-hub collaboration model, “digital innovation enclaves” could be created between Jinan and Qingdao, aligning computing resource allocation with the digital transformation needs of traditional industries in western China and thereby reducing dependence on geographic proximity. At the same time, the hub functions of two-way overflow regions—such as Beijing and Tianjin—should be activated to accelerate the integration of data factor markets. Through synergistic operations between national and regional data platforms, administrative barriers can be dismantled, achieving a dynamic balance between path dependence and path creation.

(2) Restructure factor allocation rules to enhance collaborative incentives in highly marketized regions. To address the insufficient motivation for external collaboration among highly marketized provinces, institutional innovation should be employed to facilitate the efficient flow of innovation factors. In regions with advanced digital innovation capabilities, mechanisms for data ownership confirmation and tradability must be expedited, and privacy-preserving computing technologies—enabling data usability without compromising confidentiality—should be widely promoted to unlock technological resources in market-driven areas. For instance, outcomes from interprovincial collaborations could be incorporated into local government performance evaluation systems; targeted tax incentives could be introduced in digital innovation partnerships, offering proportional tax reductions to enterprises or regions that export digital technologies. Moreover, the government should play a guiding role in addressing critical bottlenecks—such as semiconductors and industrial software—by having central ministries coordinate “challenge-based” innovation programs that mandate joint applications from technologically advanced eastern provinces and application-rich central/western provinces, thereby fostering technological complementarity and resource sharing.

(3) Establish a resilience assessment framework for spatial interconnection networks to mitigate path dependence risks. China’s provincial digital innovation network is predominantly chain-like, supplemented by limited closed-loop structures, and exhibits high concentration around core nodes. This necessitates a resilience governance system encompassing monitoring, early warning, and recovery mechanisms. If core eastern regions—such as Beijing and Jiangsu—exert excessive control over the entire digital innovation network, they may inadvertently suppress innovation incentives in other regions and weaken overall network resilience. We therefore recommend proactively identifying monopolistic tendencies in primary beneficiary blocks and monitoring the spatial concentration of critical digital technologies. These leading regions should be encouraged to co-develop backup collaboration channels with broker provinces—including Gansu, Hubei, and Sichuan—and routinely allocate a share of digital projects to central and western areas. Additionally, data disaster recovery centers should be established at key nodes in central and western China to alleviate lock-in effects and systemic risks associated with geographic proximity, thereby steering the network toward a multicentric, grid-like structure and enhancing the stability of China’s digital innovation ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.Z.; Conceptualization, M.X.; Writing—original draft, M.X., Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z.; Data curation, Y.Z., M.X.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z., M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund Project, grant number: 25BJY045; Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund Project of the Ministry of Education, grant number: 23YJA790105.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hodapp, D.; Hanelt, A. Interoperability in the era of digital innovation: An information systems research agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2022, 37, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Henfridsson, O.; Kallinikos, J.; Gregory, R.; Burtch, G.; Chatterjee, S.; Sarker, S. The next frontiers of digital innovation research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2024, 35, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, M.Z.; Alsabban, A. Industry-4.0-enabled digital transformation: Prospects, instruments, challenges, and implications for business strategies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.; Teoh, S.Y.; Yeow, A.; Pan, G. Agility in responding to disruptive digital innovation: Case study of an SME. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; Sun, Y. Ambidextrous knowledge accumulation, dynamic capability and manufacturing digital transformation in China. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 2275–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, P.; Cranmer, S.J.; Desmarais, B.A. Temporal exponential random graph models with btergm: Estimation and bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 83, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.E.; Shi, L.; Bao, H.; Cao, X.; Wang, S.; Lu, L. Comparative study on evolution of digital technology patent innovation network in three urban agglomerations. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Yimamu, N.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Irfan, M.; Hao, Y. Digitalization and sustainable development: How could digital economy development improve green innovation in China? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 1847–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Huang, C. The Impact of Digital Economy Development on Improving the Ecological Environment—An Empirical Analysis Based on Data from 30 Provinces in China from 2012 to 2021. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T. East Asian authoritarian developmentalism in the digital era: China’s techno-developmental state and the new infrastructure initiative amid great power competition. Asian Surv. 2024, 64, 942–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, H.; Malmberg, A.; Maskell, P. Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004, 28, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.M. Geographies of production II: A global production network A–Z. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Yang, Z.; Lam, F.; Tam, S.W.; Yang, W.; Li, Y. Scientific and technological innovation cooperation network of the Greater Bay Area in South China: A social network analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.G.; Dos Santos, B.L.; Zheng, Z. Digital innovation as a fundamental and powerful concept in the information systems curriculum. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrell, T.; Pihlajamaa, M.; Kanto, L.; Brocke, J.; Uebernickel, F. The role of users and customers in digital innovation: Insights from B2B manufacturing firms. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Henfridsson, O.; Lyytinen, K. The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanmir, S.F.; Cavadas, J. Factors affecting late adoption of digital innovations. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershina, R.; Soppe, B.; Thune, T.M. Bridging analog and digital expertise: Cross-domain collaboration and boundary-spanning tools in the creation of digital innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital innovation management: Reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Rao, M.; Zhang, P. Too much teamwork? The effect of corporate collaboration culture on breakthrough innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 78, 106913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Huo, Y. Impact of digital technology innovation on carbon emission reduction and energy rebound: Evidence from the Chinese firm level. Energy 2025, 320, 135187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, T. The spatiotemporal evolution of digital technology innovation and multidimensional mechanism of digitalization. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 182, 103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wen, L.; Wu, Y.; Perera, S.C. How does digital technology reshape the boundaries of intercity innovation collaboration? Evidence from China. J. Reg. Sci. 2025, 65, 1379–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, P.; Holzmann, P. Digital sustainable entrepreneurship: A business model perspective on embedding digital technologies for social and environmental value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloini, D.; Latronico, L.; Pellegrini, L. The impact of digital technologies on business models: Insights from the space industry. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2022, 26, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanin, D.; Rosenfield, R.; Mahto, R.V.; Singhal, C. Barriers to entrepreneurship: Opportunity recognition vs. opportunity pursuit. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.; Kraus, S.; Syrjä, P. The shareconomy as a precursor for digital entrepreneurship business models. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2015, 25, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Xie, T.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L. Digital economy: An innovation driver for total factor productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Lai, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Lai, X. Does public data openness accelerate new quality productive forces? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Exploring regional innovation growth through a network approach: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Manelli, L.; Frattini, F.; Bogers, M.L. The digital transformation of the innovation process: Orchestration mechanisms and future research directions. Innovation 2022, 24, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund, A.; Wagner, H.T.; Beimborn, D.; Weitzel, T. Digital innovation: Review and novel perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinilli, A.; Gao, Y.; Scherngell, T. Structural dynamics of inter-city innovation networks in China: A perspective from TERGM. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2024, 24, 707–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Z.; Gang, Z.; Yongmin, S. Progress and prospect of research on innovation networks: A perspective from evolutionary economic geography. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bican, P.M.; Brem, A. Managing innovation performance: Results from an industry-spanning explorative study on R&D key measures. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020, 29, 268–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Passiante, G.; Barberio, G.; Innella, C. Digital innovation ecosystems for circular economy: The case of ICESP, the Italian circular economy stakeholder platform. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2021, 18, 2050053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, C. Quantitative mapping of the evolution of AI policy distribution, targets and focuses over three decades in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yuan, F.; Wu, F.; Yu, S. Digital transformation and management earnings forecast. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ye, X. Spatial correlation networks characteristics and influence mechanisms of the resilience of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration: A complex network perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zeng, S. Evolution of the Spatial Network Structure of the Global Service Value Chain and Its Influencing Factors—An Empirical Study Based on the TERGM. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, S. Do fintech applications promote regional innovation efficiency? Empirical evidence from China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, M. Spatiotemporal pattern evolution and multidimensional driving mechanism of digital innovation in China: Evidence from digital economy patent applications. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Milo, R.; Shen-Orr, S.; Itzkovitz, S.; Kashtan, N.; Chklovskii, D.; Alon, U. Network motifs: Simple building blocks of complex networks. Science 2002, 298, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ding, Z.; Cao, Z.; Wu, K.; Wang, R. Evolution characteristics and driving forces of urban collaborative innovation networks in the Yangtze River Delta. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Q.; Song, Y.; Xin, Y. How cross-regional collaborative innovation networks affect regional economic resilience: Evidence from 283 cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 215, 124057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Yan, T.; Cao, X. The impact of digital infrastructure on regional green innovation efficiency through industrial agglomeration and diversification. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Towards innovation resilience through urban networks of co-invention: A case study of cities in China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 974219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caimo, A.; Gollini, I. A multilayer exponential random graph modelling approach for weighted networks. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2020, 142, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Hu, W.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Mapping an innovation ecosystem using network clustering and community identification: A multi-layered framework. Scientometrics 2020, 124, 2057–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).