Abstract

The institutionalization of environmental courts enhances regional environmental enforcement efficacy, which in turn exerts intensified regulatory pressure on local pollution intensive enterprises. Empirical evidence confirms that such judicial mechanisms significantly improve the supply chain financing capacity of regulated firms through a green governance channel. This causal pathway operates via three interrelated mechanisms: increased environmental disclosure transparency, strategic recruitment of executives with environmental expertise, and systematic ESG performance upgrades. Collectively these adaptations enable polluting enterprises to achieve better supply chain financing conditions. Subgroup analysis identifies three dimensions of heterogeneous treatment effects. First, the financing enhancement effect is more pronounced among larger enterprises due to their greater resource allocation flexibility. Second, firms with gender-diverse leadership, particularly those employing female executives, demonstrate stronger responsiveness to environmental regulations. Third, enterprises operating in less technology intensive sectors benefit more substantially from compliance driven financing improvements, as their operational structures are more amenable to rapid environmental governance adjustments.

1. Introduction

The intensification of environmental regulatory stringency and the progressive escalation of environmental policies have subjected pollution-intensive enterprises to heightened financing constraints []. Financial intermediaries increasingly incorporate rigorous environmental risk evaluations into their credit assessment frameworks, consequently elevating the capital acquisition costs for these regulated entities []. Nevertheless, polluting enterprises remain indispensable actors in socioeconomic ecosystems, functioning as industrial cornerstones and primary economic growth engines in numerous regional contexts []. Under these circumstances, developing effective mechanisms to mitigate financing barriers for pollution-intensive firms while facilitating their transition toward sustainable operations emerges as a critical pathway to achieving high-quality economic development [,,,].

Supply chain financing offers polluting enterprises a new financing channel, alleviating their financing constraints. Supply chain financing enables enterprises to obtain funding through credit relationships with suppliers or customers during daily operations [,]. It may contribute to improving cash flow and capital turnover by extending payment cycles or accelerating collection mechanisms. Compared to traditional bank loans, supply chain financing generally avoids interest or collateral fees, reducing financing costs while offering greater flexibility []. Enterprises completing transactions without immediate cash payments via extended terms can allocate funds to urgent needs or business expansion []. According to information asymmetry theory and stakeholder theory, polluting enterprises adopting cleaner production methods can cultivate a more positive image among stakeholders, potentially improving their supply chain financing conditions []. Consequently, how strengthened environmental regulations affect polluting enterprises’ financing activities warrants further analysis to inform governmental efforts balancing economic development and environmental protection.

This study exploits the gradual establishment of municipal intermediate environmental courts as a quasi-natural experiment to empirically examine how environmental regulatory strengthening affects supply chain financing for polluting enterprises. We find that the enhanced environmental regulations driven by local environmental courts significantly improve supply chain financing for polluting enterprises, with more pronounced effects among larger enterprises, those with female executives, and less technologically intensive enterprises. The mechanism lies in environmental courts compelling polluting enterprises toward green governance, specifically enhancing environmental disclosure quality, appointing executives with environmental expertise, and improving ESG performance. Placebo tests address endogeneity concerns, while robustness checks using additional control variables and alternative sample periods confirm the relationship’s stability.

Our contributions are threefold. First, we extend existing environmental regulation research paradigms. While most studies focus on policy enactment and implementation effects, particularly how enterprises achieve pollution control or environmental targets under policy pressure, they largely neglect environmental judicial enforcement. This study systematically examines how environmental court establishments strengthen formal institutions, influencing enterprise financing behavior and providing new empirical insights for the “law and finance” literature. Second, we contribute to literature on antecedents of supply chain financing. Current research inadequately explores economic consequences of ecological legal system enhancements from a supply chain financing perspective, hindering comprehensive assessments of sustainable transition costs and social risks. By leveraging environmental court establishment as an exogenous shock, we demonstrate that strengthened legal enforcement functions as an effective mechanism compelling green governance to improve supply chain financing. This offers academia a new perspective on how environmental legal systems affect capital market development. Third, we provide novel evidence on the linkage between environmental justice and enterprise green transition. Existing literature emphasizes unidirectional constraints of environmental policies, whereas our judicial intervention perspective reveals a “pressure-transformation-incentive” cycle whereby strengthened regulations (judicial enforcement) improve financing conditions and incentivize proactive green transformation. This supplements environmental policy evaluation by incorporating judicial dimensions and verifies the dual regulatory role of legal instruments in promoting sustainability by constraining polluting behavior while incentivizing green transformation through market signals such as improved financing.

The remainder proceeds as follows: Section 2 reviews related literature and develops hypotheses on how environmental court affects polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing; Section 3 details research design, including data sources, variable definitions, and the triple-difference model; Section 4 presents empirical results (main effects, robustness tests, mechanism analysis, heterogeneity); Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Institutional Background

With the acceleration of industrialization and the sustained development of the global economy, the complexity and severity of environmental issues are continuously increasing. The growing prominence of problems such as air pollution, soil contamination, and the loss of biodiversity not only inflicts irreversible damage on natural ecosystems but also directly threatens human health and quality of life [,,]. In this context, enterprises as major contributors to these issues, have become a primary focus of regulatory efforts. China has repeatedly enacted relevant environmental protection laws to regulate corporate behavior. However, in practice, law enforcement officers face difficulties in applying these laws during the specific implementation of environmental legislation [,]. Firstly, the jurisdictional approach to environmental cases differs from traditional cases, as they cannot be simply categorized into criminal, civil, and administrative cases and assigned to corresponding personnel for trial. Secondly, the trial process of environmental cases often involves multidisciplinary expertise, but traditional legal practitioners, mostly with a liberal arts background, lack the professional competence required for handling environmental cases. This deficiency makes it challenging for them to grasp the appropriate application of laws during trials, leading to misjudgments and lenient sentences in environmental cases. Therefore, the phenomena of “non-compliance with laws despite their existence” and “difficulty in holding violators accountable” in China’s environmental judicial system require further resolution, and the effectiveness of environmental judicial functions needs further development.

Given the dilemmas in environmental legal systems, the environmental court system emerged as a crucial legal force in regulating the efficiency of regional environmental law enforcement. With its specialized review process and efficient judgment efficiency, environmental courts have significantly enhanced the enforcement capacity of environmental justice, playing a pivotal role in advancing the establishment of an ecological legal system. Specifically, the enforcement advantages of environmental courts are as follows, primarily manifested in higher professionalism, efficient trials, clear jurisdiction, and stringent penalties.

(1) The establishment of environmental courts enhances the professionalism of the trial process for environmental litigation cases. Traditionally, Chinese legal practitioners, mostly with a liberal arts background, lack sufficient knowledge in environmental science, leading to potential misjudgments during trials due to professional limitations. The establishment of environmental courts has prompted courts to prioritize environmental backgrounds when recruiting practitioners and strengthen environmental professional knowledge training for existing practitioners, thereby enhancing the professionalism of court trials for environmental litigation cases. For instance, the Liaoning Provincial High People’s Court specifically selected talents capable of handling environmental cases when establishing its environmental court and established a corresponding environmental talent team to adequately prepare for enhancing environmental law enforcement capabilities.

(2) The establishment of environmental courts facilitates efficient trials of environmental litigation cases. Unlike the separate trial approach for administrative, criminal, and civil cases, environmental courts have institutionally clarified the consolidated trial of environmental litigation cases, pioneering the “three-in-one” and “two-in-one” centralized trial models (i.e., unifying environmental-related administrative, criminal, and civil cases for centralized adjudication by professional trial institutions), thereby significantly improving the trial efficiency of environmental litigation cases. For example, at the end of 2023, the Datong Environmental Court implemented a “two-in-one” centralized trial model for a case involving “the use of prohibited fishing nets during the fishing ban period” within its jurisdiction, with a collegiate panel composed of judges from both civil and criminal departments swiftly conducting the trial and sentencing the involved individuals. Additionally, environmental courts can promptly halt environmental violations, integrating the trial and enforcement of environmental litigation cases. For instance, at the end of 2022, the Beijing Environmental Court accepted a lawsuit filed by the Miyun District Tax Bureau against a local enterprise for discharging sewage and immediately ordered the enterprise to cease pollution and imposed a fine upon accepting the case.

(3) The establishment of environmental courts enhances the clarity of territorial jurisdiction for environmental cases. Some environmental resource cases may possess cross-regional characteristics, leading to ambiguous territorial jurisdiction and affecting law enforcement. The establishment of environmental courts aids in centralized jurisdiction and governance of cases, resolving issues of mutual shirking of responsibility and lack of recourse in pollution cases spanning administrative boundaries. For example, Hunan Province has clearly delineated environmental resource cases based on watersheds and ecological functional zones, effectively addressing cross-administrative boundary challenges in water pollution control within the province.

(4) Environmental courts can impose stricter penalties on polluting enterprises. Environmental courts have formally enhanced the stringency of penalties for polluting behaviors, imposing higher pollution costs on enterprises through the implementation of a “daily penalty” system. For severely polluting enterprises, environmental courts may even mandate a cessation of operations or relocation outside the region to strictly curb environmental pollution. For instance, Wynca, a top 500 manufacturing enterprise in China and a large listed company, was ordered by the Dongying Environmental Court to suspend operations and rectify, and fined RMB 22.74 million for directly discharging wastewater into watersheds and illegally dumping it in Shandong and Jiangsu provinces.

2.2. Literature Review of Enterprise Supply Chain Financing

In the globally uncertain business landscape, robust and resilient supply chain management has become a critical pillar of corporate core competitiveness, offering significant value in enhancing enterprises’ dynamic capabilities [,,,]. Supply chain financing, as a critical financing source for enterprises, demonstrates differential access structurally influenced by ownership nature and asset scale. Research indicates state-owned enterprises and large enterprises exhibit significant advantages in supply chain financing due to institutional privileges and asset collateral capacity, whereas private enterprises and small–medium enterprises face dual constraints of restricted financing channels and high costs [,]. This disparity originates from state-owned enterprises’ stronger risk resilience and reputational capital, enabling them to maintain stable supply chain credit relationships amid market volatility [,]. Notably, asset structure mismatch may further deteriorate financing conditions, forming a vicious cycle hindering high-quality enterprise development [].

Information transparency theory offers new perspectives for addressing supply chain financing. Enterprises can effectively reduce information asymmetry through optimizing annual report readability and enhancing disclosure frequency and quality, thereby improving supply chain financing conditions []. External information intermediaries such as analyst coverage also strengthen stakeholder recognition and trust, creating a virtuous financing cycle [,]. Notably, emerging technologies like blockchain are proven to enhance transparency and reshape supply chain operations, albeit they may introduce new market dynamics []. Corporate governance research reveals that controlling shareholders’ expropriation of minority interests undermines investor confidence and worsens overall financing environments [,].

From an upper echelon theory perspective, executive characteristics profoundly impact supply chain financing. Risk-tolerant executives tend to explore diversified financing channels, while broad decision-making horizons indirectly enhance financing capacity through improved governance [,,]. Executive professional reputation and social capital prove equally vital, where favorable reputation signals positive attributes, while social networks based on alumni or regional ties serve as supply chain funding channels [,]. Institutional economics research further indicates that regional cultures such as merchant associations and Confucianism subtly influence supply chain financing environments by shaping business ethics and trust mechanisms [,,].

Simultaneously, the external policy environment, such as low-carbon regulations, critically shapes supply chain strategies and their financial stability by balancing environmental goals with economic pressures [].

Overall, existing research predominantly explores antecedents of enterprise supply chain financing from institutional arrangements, information environments, corporate governance, and cultural perspectives, yet rarely examines differentiated impacts through the lens of strengthened environmental law enforcement capability.

2.3. Research Hypothesis

Enterprises failing to effectively implement environmental measures or neglecting regulatory requirements face not only substantial fines but also significant brand reputation damage. This dual risk compels enterprises to accelerate green transformation through adopting advanced environmental technologies, optimizing production processes, and reducing pollutant emissions, thereby gradually aligning with sustainable development models under legal and market pressures []. In this process, environmental courts function as catalysts compelling enterprises to fundamentally reevaluate and adjust production models to meet increasingly stringent legal requirements and evolving societal expectations [].

Per information asymmetry theory, financiers often lack comprehensive understanding of enterprises’ actual conditions []. For polluting enterprises specifically, uncertainties regarding environmental compliance and governance levels typically lead suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders to adopt conservative risk assessments. Consequently, supply chain financing costs increase while accessibility decreases. However, as polluting enterprises enhance environmental governance and information transparency, they effectively reduce information asymmetry and improve supply chain credibility []. Signaling theory and stakeholder theory further suggest that proactive green governance behaviors signal positive attributes to stakeholders and respond to their expectations, thereby strengthening trust and support []. Although environmental risk exposure constrains value creation capacity for polluting enterprises [], proactive environmental responsibility may constitute a strategic investment that reduces future risks and enhances long-term performance [,]. Furthermore, constrained by social norms, stakeholders with socially responsible investment principles may prefer providing funding to enterprises demonstrating active green governance, even accepting potential short-term financial trade-offs. Based on this analysis, we propose:

Hypothesis 1a:

The establishment of regional environmental courts improves supply chain financing for polluting enterprises.

Given that polluting enterprises may face significant uncertainties under stricter environmental regulations, stakeholders such as suppliers and customers may make negative judgments based on projected environmental risks and performance during the process of polluting enterprises seeking supply chain financing. For instance, they may anticipate a decline in the future operating performance and poor environmental performance of pollution-intensive enterprises, leading to an inability to repay debts and pay interest on time []. Consequently, stakeholders like suppliers and customers may impose more stringent requirements on pollution-intensive enterprises in terms of fund delivery, accounts receivable recovery, and other aspects, ultimately exacerbating the supply chain financing situation of polluting enterprises [,,]. Moreover, if pollution-intensive enterprises cease relevant pollution emission behaviors in their production processes to avoid environmental penalties, it may lead to a halt in their own operational and production activities, placing them in a disadvantageous position of contract default. They may even face major financial crises such as a broken capital chain and bankruptcy, adversely affecting their supply chain financing. Based on this, we propose the following competitive hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1b:

The establishment of regional environmental courts inhibits supply chain financing for polluting enterprises.

Therefore, empirical testing is needed to verify the relationship between environmental courts and supply chain financing of polluting enterprises.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Source

We select China’s A-share listed enterprises from 2008 to 2023 as the research sample. Following the “Environmental Information Disclosure Guidelines for Listed Enterprises” issued by China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection, industries including thermal power, steel, cement, electrolytic aluminum, coal, metallurgy, chemicals, petrochemicals, building materials, papermaking, brewing, pharmaceuticals, fermentation, textiles, leather, and mining are classified as polluting industries. We define enterprises whose principal operations fall within these polluting industries as polluting enterprises.

Furthermore, we manually compile data on regional environmental court establishments from multiple sources including China Justice Net and municipal court websites, while obtaining enterprise control variables from CSMAR. The study excludes samples with missing data, financial and real estate enterprises, and ST enterprises. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% level on both tails, yielding 23,448 enterprise-year observations.

3.2. Variable Description

The dependent variable is enterprise supply chain financing (SCF), measured as the ratio of accounts payable, notes payable, and advances from customers to total assets []. The explanatory variable is the interaction term (E_P) of municipal environmental court establishment (Envir_Court) and the polluting enterprise dummy (Pollu). Control variables include enterprise size (Size), firm age (Firm_Age), book-to-market ratio (BM), employee scale (Staff), cash ratio (Cash), asset-liability ratio (Leverage), profitability (Profit), ownership concentration (Top_1), and board size (Boardsize). Year and enterprise fixed effects are controlled. Variable definitions are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable Definition.

3.3. Model Setting

We employ a triple differences approach for empirical testing, with all regression coefficient standard errors adjusted for double clustering at the enterprise and year levels.

where SCFi,t denotes supply chain financing obtained by enterprise i in year t; E_Pi,t represents the core explanatory variable, specifically the interaction term between Envir_Courti,t (indicating establishment of an intermediate-level environmental court in enterprise i’s locality in year t − 1) and Pollui,t (the dummy variable for polluting enterprises); Controlsi,t signifies the control variables detailed in Table 1. We controlled for dummy variable of environmental courts (Envir_Court), enterprise fixed effects, and year fixed effects to avoid estimation bias. Our focus is on coefficient β1. If β1 is positive, it indicates that environmental courts significantly improves supply chain financing for polluting enterprises, supporting Hypothesis 1a; otherwise, Hypothesis 1b holds.

SCFi,t = β0 + β1E_Pi,t + β2Envir_Courti,t + Controlsi,t + ∑Yeart + ∑Enterprisei,t + εi,t

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

We select China’s A-share listed enterprises from 2008 to 2023 as the research sample Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the variables. The dependent variable enterprise supply chain financing (SCF) shows a mean of 0.169, standard deviation of 0.117, minimum of 0.009, and maximum of 0.546, indicating significant cross-enterprise variation in supply chain financing. Means of Envir_Court and Pollu imply intermediate environmental courts were established in cities hosting approximately 26.1% of enterprises, with 18.5% identified as polluting enterprises, providing sufficient sample variation for examining environmental regulation effects on polluting enterprises’ SCF. Additional variables exhibit means consistent with prior studies: enterprise size (Size) at 22.214, growth opportunity (Growth) at 0.165, return on assets (ROA) at 0.035, listing age (Firm_Age) at 10.188, cash ratio (Cash) at 0.155, leverage ratio (Leverage) at 0.446, largest shareholder ownership (Top_1) at 35.163%, state-owned enterprise status (SOE) at 0.430 (indicating approximately 43.0% state-owned enterprises in the sample), tangible asset ratio (Tangible) at 0.928, and proportion of independent directors (Indeboard) at 37.271%, indirectly affirming data reliability.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.2. Benchmark Regression

Table 3 presents benchmark regression results examining intensified environmental regulation and supply chain financing for polluting enterprises. Column (1) controls solely for year and enterprise fixed effects. Column (2) incorporates enterprise characteristic control variables. Column (3) further adds enterprise governance control variables. Results demonstrate consistently positive and significant coefficients for the interaction term E_P, indicating that establishing local environmental courts significantly improves supply chain financing for polluting enterprises, thereby validating Hypothesis 1a.

Table 3.

Benchmark Regression.

Based on the results of OLS regression analysis, the capacity of enterprises to obtain supply chain financing exhibits a series of systematic characteristics, profoundly reflecting the dynamic alignment between their financing strategies and internal and external conditions. Specifically, enterprises with high growth potential (characterized by high revenue growth rates) and high profitability efficiency (high ROA) are more likely to be perceived as high-quality investment partners due to the positive signals they convey to suppliers and customers. This makes them attractive partners and helps secure better credit terms. In contrast, larger companies benefit from steadier cash flow and diverse financing options. This reduces their reliance on supply chain financing and demonstrates a clear financing substitution effect. Risk profiles also shape financing behavior. High risk firms with high leverage turn to supply chain financing when traditional credit is constrained. Credit advantaged firms including state owned enterprises or those with substantial fixed assets access financing more easily through government guarantees or asset collateral. Additionally, corporate governance structures also play a pivotal role. Firms with concentrated ownership adopt more cautious financial policies. They may prefer internal funding and maintain reasonable levels of supply chain debt.

4.3. Robust Test

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

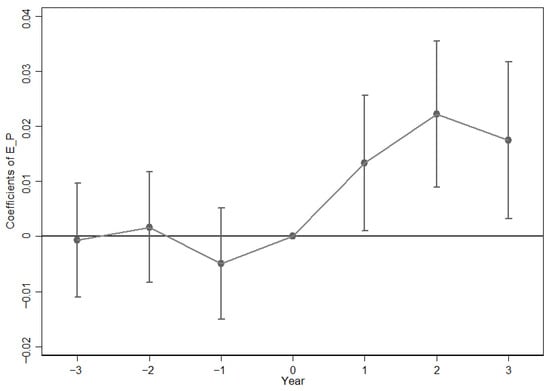

The triple-difference model employed in this study relies on the parallel trends assumption, implying that prior to the establishment of municipal environmental courts, the difference in supply chain financing between polluting and non-polluting enterprises was insignificant. However, following the progressive establishment of city-level environmental courts, polluting enterprises exhibited significantly different supply chain financing levels compared to non-polluting enterprises. Temporal dummy variables spanning three years before and after court establishment were constructed to examine dynamic effects. Figure 1 indicates statistically insignificant coefficients for E_P in pre-establishment years (Year = −3, −2, −1), whereas post-establishment years (Year = 1, 2, 3) show significant coefficients, confirming satisfaction of the parallel trends assumption.

Figure 1.

Parallel Trend Test.

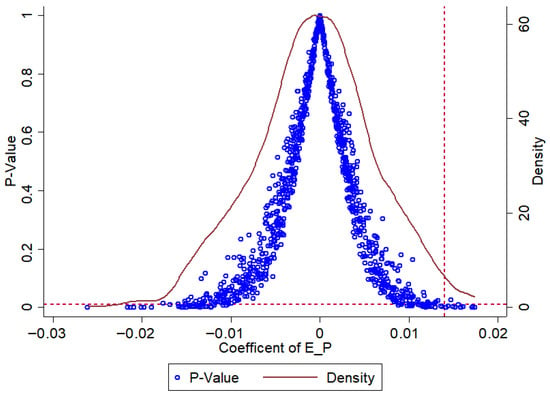

4.3.2. Endogenous Test: Placebo Test

This section further implements a placebo test to alleviate endogeneity concerns regarding the relationship between intensified environmental regulation from court establishment and enterprise supply chain financing []. Specifically, random dummy assignments for court establishment status and timing were applied to each city, maintaining identical annual establishment counts versus actual data. Regression analysis was then performed on these pseudo-samples to obtain coefficients for the interaction term between the dummy court variable and polluting enterprise dummy. After 1000 simulation iterations, kernel density distributions and p-values were reported (Figure 2). Results demonstrate simulated coefficients centered near zero with significant deviation from the true coefficient, indicating that the identified effect of court establishment on polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing is unlikely coincidental, thereby mitigating endogeneity concerns for the main findings.

Figure 2.

Placebo Test.

4.3.3. Endogenous Test: Propensity Score Matching

Previous studies have regarded the establishment of environmental courts as a random event. However, some scholars may still harbor concerns about the strong correlation between the court establishment and urban resource endowments, thereby raising endogeneity concerns regarding the empirical results of this paper. Cities with established environmental courts and those without may differ in terms of economic development and environmental conditions. These differences could potentially lead to systematic disparities in the levels of trade credit financing faced by enterprises. To address these potential endogeneity issues, we employ the propensity score matching (PSM) method. We first match the samples of cities with established environmental courts and then conduct regression analysis.

Specifically, we use urban GDP and its growth rate, the proportion of the secondary industry, the proportion of the tertiary industry, fiscal surplus, and the proportion of foreign investment in GDP as matching variables. We then apply the 1:1 nearest—neighbor matching principle to conduct propensity score matching on the samples. Regression analysis is conducted on the matched samples. As shown in column (1) of Table 4, the coefficient of E_P is 0.037 and is significant at the 1% level. In addition, as presented in column (2) of Table 4, we further introduce urban industrial wastewater discharge, industrial sulfur dioxide emissions, and industrial smoke (dust) emissions as matching variables. It is found that the coefficient of E_P is 0.065 and remains significant at the 1% level. Overall, the results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 effectively alleviate concerns about the endogeneity in the relationship between the establishment of environmental courts and supply chain financing.

Table 4.

Endogenous Test: Propensity Score Matching and Counterfactual Test.

4.3.4. Endogenous Test: Counterfactual Test

To dispel concerns that the establishment of environmental courts does not constitute a quasi—natural experiment and to address endogeneity concerns regarding the relationship between environmental courts and supply chain financing of polluting enterprises, we employ counterfactual test for verification. Specifically, the cities are ranked based on the total annual emissions of industrial wastewater, SO2, and soot. It is assumed that the cities with the highest pollutant emissions establish environmental courts. Moreover, the number of simulated environmental court establishments each year is set to be equal to the actual number of establishments. The regression results are shown in column (3) of Table 4. Under these artificially set experimental conditions, environmental courts do not have a significant mitigating effect on supply chain financing. This further alleviates concerns about the endogeneity in the relationship between environmental court and supply chain financing.

4.3.5. Including More Control Variables

We further incorporate additional enterprise-level control variables (current ratio, Current; quick ratio, Quick; board size, Boardsize; CEO-chair duality indicator, Duality) and regional-level controls (natural logarithm of local GDP, GDP; and natural logarithm of local population, Popu) into the baseline regression model (1). Results are reported in columns (1)–(3) of Table 5. The findings indicate that controlling for these enterprise characteristics and regional features does not alter the robustness of the relationship between environmental court establishment and supply chain financing for polluting enterprises, suggesting the commonality of intensified environmental regulation in improving polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing.

Table 5.

Robust Test: Including More Control Variables.

4.3.6. Replace Dependent Variable

We use the cash turnover ratio as a proxy variable for supply chain financing. The cash turnover ratio is calculated as the sum of the inventory turnover days and the accounts receivable turnover days minus the accounts payable turnover days. A lower cash conversion cycle (Cash_Turn) indicates a stronger supply chain financing capacity of the enterprise. The relevant regression results are presented in column (4) of Table 5. It can be observed that E_P significantly suppresses Cash_Turn, which suggests that environmental courts has improved cash turnover ratio of polluting enterprises.

4.3.7. Sample Range Changing

We additionally examine the robustness of the baseline relationship between intensified environmental regulation and polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing by excluding potentially confounding samples, as shown in Table 6. Specifically, column (1) excludes enterprises in China’s four direct-administered municipalities (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing). Column (2) removes samples from economically advanced provincial-level units (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, and Shandong Provinces). Considering the prolonged financial crisis impact, column (3) excludes 2008–2010 samples. Accounting for COVID−19 influences, column (4) omits 2020–2021 samples. Based on the consistent E_P coefficients across Table 5 columns, we infer that altering spatiotemporal sample scopes does not affect the relationship between environmental court establishment and polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing, confirming Hypothesis 1a’s robustness.

Table 6.

Robust Test: Sample Range Changing.

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.4.1. Improvement of Environmental Information Disclosure Quality

As independent judicial bodies, environmental courts conduct impartial and transparent adjudications on environmental issues, safeguarding public legal rights. Their establishment increases penalties for non-compliant enterprises, elevating legal risks and liabilities []. When disclosing environmental information, enterprises may recognize such disclosure not only as a legal obligation but also as critical to their reputation and long-term development. Consequently, they voluntarily increase disclosures to mitigate potential penalties from concealed negative information []. This motivates proactive fulfillment of environmental disclosure obligations, enhancing accuracy and compliance.

From an information asymmetry perspective, improved environmental disclosure quality helps polluting enterprises alleviate informational disadvantages in financing. During industrial chain operations, stakeholders such as suppliers and clients often lack comprehensive insight into an enterprise’s actual operations. For polluting enterprises specifically, uncertainties regarding environmental compliance may lead partners toward conservative risk assessments [,]. Such information asymmetry may exacerbate supply chain financing difficulties for polluting enterprises amid strengthened environmental regulation. Therefore, enhancing environmental governance and data transparency allows enterprises to demonstrate genuine environmental performance, reduce information asymmetry, and strengthen stakeholder trust.

Based on this analysis, we posit that intensified environmental regulation through local environmental courts improves environmental disclosure quality for polluting enterprises, thereby facilitating supply chain financing. To test this mechanism, we regress environmental disclosure quality (E_Dis) from CSMAR against our explanatory variable E_P. Results in column (1) of Table 7 confirm that environmental court establishment significantly enhances disclosure quality for polluting enterprises.

Table 7.

Mechanism Analysis: Green Governance Effect.

4.4.2. Hiring Executives with Environmental Backgrounds

Historically, enterprises prioritized economic efficiency and industry experience over environmental awareness when selecting management personnel []. However, the emergence of environmental courts has significantly increased legal risks for enterprises, particularly polluting enterprises facing environmental penalties, litigation, and reputational damage. This compels polluting enterprises to adjust management strategies toward environmentally sustainable practices.

Executives with environmental credentials typically possess specialized backgrounds in environmental science, law, or management []. Such expertise enables them to navigate complex regulatory requirements, effectively mitigate environmental risks, optimize compliance costs, improve green technology deployment, and institutionalize environmental awareness within enterprises. These adjustments enhance regulatory compliance while strengthening sustainable development capabilities and corporate reputation. Consequently, hiring environmentally credentialed executives may improve sustainable operations and enhance financing market competitiveness. Additionally, environmentally credentialed executives often possess established communication channels with environmental organizations. Through professional networks, enterprises gain timely access to regulatory developments and market expectations. This informational advantage supports strategic decision-making while building trust with investors, thereby improving financing market credibility.

Based on this analysis, we posit that intensified environmental regulation through local environmental courts promotes the hiring of environmentally credentialed executives by polluting enterprises, thereby improving supply chain financing. Executive background data from CSMAR were manually consolidated with supplementary sources (Sina Finance, Wind) to identify environmental credentials. Subsequent regression of EP_Execu (ratio of environmentally credentialed executives) on E_P yields results in column (2) of Table 7. The significantly positive E_P coefficient at the 5% level indicates that environmental court establishment promotes the hiring of environmentally credentialed executives by polluting enterprises.

4.4.3. Enhancing Sustainable Development Capability

In contemporary society, public scrutiny of corporate social responsibility and environmental impact has intensified, extending beyond governmental regulation to encompass heightened expectations from consumers, investors, and other stakeholders [,,]. Enterprises failing to address environmental challenges may face reputational damage and consumer boycotts, directly compromising market position and brand value. Consequently, to maintain competitiveness, polluting enterprises are compelled to actively improve environmental performance for sustainable transformation, aligning with societal sustainability expectations. Enterprises demonstrating superior sustainability performance typically alleviate financing constraints [,]. This primarily stems from their enhanced operational and financial governance, which builds trust among capital providers. Consequently, business partners offer more favorable financing terms and longer-term capital support []. Therefore, we contend that intensified environmental regulation through local environmental courts promotes sustainability in polluting enterprises, thereby improving supply chain financing.

ESG criteria comprehensively evaluate enterprise performance across environmental, social, and governance dimensions, serving as key sustainability indicators [,]. To test this mechanism, we measure sustainability using ESG performance (ESG), following Gillan, Koch and Starks [] and Sun, et al. []. Regression results in column (3) of Table 7 show a statistically significant E_P coefficient of 1.325 at the 1% level, confirming that environmental court establishment enhances ESG performance in local polluting enterprises.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Enterprise Size

Large enterprises typically possess superior financial resources, enabling greater investment in green technology R&D and application []. Compared to small enterprises, large enterprises implement environmental facility upgrades and technical modifications more readily while absorbing associated costs []. Such enterprises execute large-scale investments to accelerate green transformation and meet stringent environmental standards [].

Second, larger enterprises exhibit stronger technological innovation and managerial expertise [,]. Their established R&D departments swiftly adopt emerging environmental technologies and management methods. Effective application of green technologies and optimized management are critical for regulatory compliance. Large enterprises leverage these advantages to implement systematic green reforms, achieving superior environmental compliance. Conversely, small enterprises face constraints in green technology adoption due to limited R&D capabilities, resulting in less pronounced transformation outcomes [].

Furthermore, large enterprises prioritize brand image protection as reputation directly impacts market competitiveness and consumer trust []. Concerns over reputational damage and penalties drive proactive green governance []. Their environmental investments serve dual purposes: regulatory compliance and avoidance of public backlash. Consequently, large enterprises allocate more resources toward green technologies and sustainability, demonstrating stronger environmental governance under regulatory pressure. Small enterprises exhibit weaker motivation due to limited reputational exposure. Therefore, we posit that intensified environmental regulation through local environmental courts disproportionately improves supply chain financing for large polluting enterprises.

To examine this size-based heterogeneity, we categorize enterprises by total assets relative to annual industry averages. Enterprises exceeding annual industry mean asset values constitute the large enterprise subsample; others form the small–medium enterprise subsample. Results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8 demonstrate a significantly positive E_P coefficient for large enterprises, exceeding that of small enterprises. This confirms that environmental court establishment more substantially improves supply chain financing for large polluting enterprises.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity Analysis.

4.5.2. Female Executive

Female executives typically demonstrate stronger social responsibility and long-term planning capabilities in decision-making [,], potentially influencing corporate environmental strategies. Existing research indicates female leaders prioritize corporate social responsibility and sustainability [], aligning closely with environmental courts’ objectives. Following environmental court establishment, female executives may more actively support environmentally protective measures, reflecting both personal values and organizational sustainability concerns [,].

Additionally, female executives often demonstrate more inclusive leadership styles that facilitate stakeholder collaboration [,]. Under regulatory pressure, enterprises require effective communication with governmental agencies, environmental organizations, and the public to develop compliant environmental strategies. Female executives’ relational strengths may secure greater societal support during policy implementation [].

Furthermore, female executives exhibit heightened sensitivity to risk management and prudence in long-term investments [,]. Increased compliance risks and societal scrutiny following environmental court establishment may prompt female executives to advance green governance [,], enhancing sustainability and supply chain financing. Therefore, we posit that intensified environmental regulation improves supply chain financing for polluting enterprises with female executives.

To test this joint effect, we categorize enterprises based on female executive presence. Enterprises with female executives constitute the female executive subsample; others form the non-female executive subsample. Results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 8 show a significantly positive E_P coefficient for female executive enterprises exceeding that of non-female executive enterprises. Thus, environmental court establishment more substantially improves supply chain financing for polluting enterprises with female executives.

4.5.3. Technology Intensive Industry

Non-technology-intensive enterprises typically feature simpler production processes and technical configurations than technology-intensive enterprises [], resulting in divergent responses to environmental regulations. First, non-technology-intensive enterprises generally operate with lower technological complexity and capital intensity []. Such enterprises primarily rely on infrastructure and labor rather than advanced technologies and equipment []. Consequently, environmental improvements seldom require large-scale technological upgrades or equipment replacements. Environmental court pressures focusing on pollution reduction, resource efficiency, and waste management prove easier and more cost-effective to implement in non-technology-intensive enterprises [].

In addition, non-technology-intensive enterprises demonstrate heightened responsiveness to corporate image maintenance in competitive markets []. Operating in highly contested environments, these enterprises require positive reputations to attract consumers and investors []. Thus, they may proactively adopt environmental measures to gain competitive advantages. Additionally, non-technology-intensive enterprises face greater financing constraints []. Compared to technology-intensive counterparts, they encounter more difficulties accessing traditional financing channels and capital markets [], increasing their reliance on supply chain relationships. Environmental court establishment heightens partner scrutiny of environmental risks, making environmental performance a critical factor for securing supply chain financing. Therefore, to mitigate regulatory risks and obtain financing, non-technology-intensive enterprises exhibit stronger incentives for proactive green governance.

Technology-intensity-based subsample results appear in columns (5) and (6) of Table 8. The E_P coefficient remains statistically significant at the 1% level for non-technology-intensive enterprises. Moreover, this coefficient exceeds that of technology-intensive enterprises. Thus, intensified environmental regulation through environmental courts more substantially promotes green governance and sustainability in non-technology-intensive enterprises, consequently improving their supply chain financing.

5. Conclusions and Implication

5.1. Conclusions

This study examines how intensified environmental regulation through local environmental courts affects supply chain financing for polluting enterprises. Exploiting the quasi-natural experiment of intermediate environmental courts’ staggered establishment across prefecture-level cities, we find that regulatory intensification significantly improves polluting enterprises’ supply chain financing. Our main results withstand multiple endogenous and robustness tests including parallel trend assessments, propensity score matching, and placebo examinations.

We further identify mechanisms through which environmental courts improve supply chain financing: compelling polluting enterprises to disclose higher-quality environmental information, appoint executives with environmental expertise, and enhance sustainability practices. Heterogeneity analyses reveal stronger green governance effects among large enterprises, enterprises with female executives, and non-technology-intensive enterprises.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

We provide a novel perspective on the application of information asymmetry theory to corporate behavior. When pollution-intensive enterprises encounter environmental risks, capital providers may lack a comprehensive understanding of their environmental risk management practices, leading them to demand higher financing costs as compensation. However, with the further intensification of environmental regulations, firms are compelled to embark on green transformation to enhance their environmental performance and management systems, making their environmental risk information more transparent and reliable. This transparency elevates the firm’s social standing and market credibility, thereby reducing financing costs. Upon acknowledging the efforts and accomplishments of firms in green transformation, capital providers can better assess their long-term risks and stability, and are thus inclined to offer more advantageous financing conditions.

We also make a contribution to the application of stakeholder theory in micro-level corporate governance. Stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance for firms to consider the interests of all relevant stakeholders. When environmental regulations are tightened, pollution-intensive enterprises face pressures from diverse stakeholders. By proactively improving their environmental performance, firms not only meet societal and customer expectations but also foster trust relationships with investors. This transformation assists firms in developing a positive social image and reputation within the industrial chain, thereby improving supply chain financing. It also empowers firms to more effectively manage environmental risks, mitigate potential environmental litigation and penalties, and ultimately enhance financial stability.

5.3. Practical Implications

Our research also provides policy insights for government and industry. First, governments should establish green transition funds providing low-interest loans or grants alongside tax incentives for environmental investments to alleviate financial burdens. Second, governments must prioritize assistance for small–medium and non-technology-intensive enterprises by establishing technical platforms, offering training programs, and encouraging technology transfers from large enterprises to reduce technical costs and financing difficulties. Additionally, governments should strengthen regulatory evaluation and transparency through specialized agencies monitoring enterprise green governance effectiveness while regularly publishing progress reports to enhance credibility and public participation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y., G.S. and X.H.; Methodology, K.Y., G.S. and X.H.; Software, K.Y. and G.S.; Validation, K.Y., G.S., X.H. and Y.W.; Formal Analysis, K.Y., G.S., X.H. and Y.W.; Data Curation, K.Y., G.S. and X.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.Y., G.S. and X.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.Y., G.S. and X.H.; Supervision, K.Y., G.S., X.H. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Project under grant 23NDJC237YB; the Outstanding Innovative Talents Cultivation Funded Programs 2022 of Renmin University of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yao, S.; Pan, Y.; Sensoy, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Cheng, F. Green credit policy and firm performance: What we learn from China. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Can the green finance policy force the green transformation of high-polluting enterprises? A quasi-natural experiment based on “Green Credit Guidelines”. Energy Econ. 2022, 114, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; He, P. Can public participation constraints promote green technological innovation of Chinese enterprises? The moderating role of government environmental regulatory enforcement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Su, Y. New media environment, environmental regulation and corporate green technology innovation:Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, H.; Sun, G.; Tao, J.; Lu, C.; Guo, C. Speculative culture and corporate high-quality development in China: Mediating effect of corporate innovation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H. Food Culture and Sustainable Development: Evidence from Firm-Level Sustainable Total Factor Productivity in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Lin, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, N.; Xiong, P.; Li, H. Cultural inclusion and corporate sustainability: Evidence from food culture and corporate total factor productivity in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelino, M.; Ferreira, M.A.; Giannetti, M.; Pires, P. Trade Credit and the Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 36, 775–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Gong, G.; Huang, X.; Tian, H. The Interaction Between Suppliers and Fraudulent Customer Firms: Evidence from Trade Credit Financing of Chinese Listed Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 179, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D.; Menichini, A.M.C. Trade credit, collateral liquidation, and borrowing constraints. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 96, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Pan, Y.; Tian, G.G.; Zhang, P. CEOs’ hometown connections and access to trade credit: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 62, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Garcia Lara, J.M.; Tribo, J.A. Unpacking the black box of trade credit to socially responsible customers. J. Bank. Financ. 2020, 119, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Ding, L.; Xiong, Z.; Spicer, R.A.; Farnsworth, A.; Valdes, P.J.; Wang, C.; Cai, F.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; et al. A distinctive Eocene Asian monsoon and modern biodiversity resulted from the rise of eastern Tibet. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Kong, D. The Real Effect of Legal Institutions: Environmental Courts and Firm Environmental Protection Expenditure. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 98, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Ren, L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, X. Punishment or deterrence? Environmental justice construction and corporate equity financing––Evidence from environmental courts. J. Corp. Financ. 2024, 86, 102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Gu, W.; Zhuang, W.; Gao, M.; Chan, C.C.; Zhang, X. Coordinated planning model for multi-regional ammonia industries leveraging hydrogen supply chain and power grid integration: A case study of Shandong. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Zeng, H.; Cong, X. Adjustment strategies and chaos in duopoly supply chains: The impacts of carbon trading markets and emission reduction policies. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, M. The impact of blockchain on carbon reduction in remanufacturing supply chains within the carbon trading market: A chaos and bifurcation analysis. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 20329–20362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X. Understanding the relationship between coopetition and startups’ resilience: The role of entrepreneurial ecosystem and dynamic exchange capability. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2025, 40, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Qian, J.; Qian, M. Law, Finance, and Economic Growth in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 77, 57–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirguc-Kunt, A. Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. J. Bank. Financ. 2006, 30, 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, M.; Burkart, M.; Ellingsen, T. What You Sell Is What You Lend? Explaining Trade Credit Contracts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 1261–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.C.; Jones, S.; Hasan, M.M.; Zhao, R.; Alam, N. Does strategic deviation influence firms’ use of supplier finance? J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2023, 85, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albring, S.; Banyi, M.; Dhaliwal, D.; Pereira, R. Does the Firm Information Environment Influence Financing Decisions? A Test Using Disclosure Regulation. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franco, G.; Vasvari, F.P.; Vyas, D.; Wittenberg-Moerman, R. Debt Analysts’ Views of Debt-Equity Conflicts of Interest. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 571–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H.V.; Wolfenzon, D. A theory of pyramidal ownership and family business groups. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 2637–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. Law and finance. J. Political Econ. 1998, 106, 1113–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsila, A. Trade Credit Risk Management: The Role of Executive Risk-Taking Incentives. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2016, 42, 1188–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Tree, D.R. Executives’ horizon and trade credit. Account. Financ. 2024, 64, 1135–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Nguyen, D.; Dao, M. Pilot CEOs and trade credit. Eur. J. Financ. 2021, 27, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Xiang, C.; Gao, R. Reputation is golden: Superstar CEOs and trade credit. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2024, 51, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, X.; Long, Z. Confucian Culture and Trade Credit: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 53, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Lu, C.; Sun, G.; Zhang, C.; Guo, C. Regional culture and corporate finance: A literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ke, J.; Ding, Y.; Chen, S. Greening through finance: Green finance policies and firms’ green investment. Energy Econ. 2024, 131, 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmke, M.; Opp, M.M. A Theory of Socially Responsible Investment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2024, 92, 1193–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, C.; Dutta, S.; Li, Y. Resolving Information Asymmetry: Signaling, Endorsement, and Crowdfunding Success. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, C.S.; Sharfman, M.P.; Uysal, V.B. Corporate Environmental Policy and Shareholder Value: Following the Smart Money. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2017, 52, 2023–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Green Bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Fitzgibbons, S.; Pomorski, L. Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Aziz, N.; Sui, H. Exploring the role of trade credit in facilitating low-carbon development: Insights from Chinese enterprises. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Ma, F.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. Game-theoretic analysis for an emission-dependent supply chain in a ‘cap-and-trade’ system. Ann. Oper. Res. 2015, 228, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.H.; Dhanorkar, S. How institutional pressures and managerial incentives elicit carbon transparency in global supply chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 697–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Granot, D.; Granot, F.; Sosic, G.; Cui, H. Incentives and Emission Responsibility Allocation in Supply Chains. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 4172–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J. Sustainability Uncertainty and Supply Chain Financing: A Perspective Based on Divergent ESG Evaluations in China. Systems 2025, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.W.; Walls, J.L.; Dowell, G.W.S. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strat. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, C.; Ow-Yong, K. Factors influencing corporate governance disclosures: Evidence from Alternative Investment Market (AIM) companies in the UK. Eur. J. Financ. 2012, 18, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Environmental and Social Disclosures and Firm Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, A.; Iyengar, R.J.; Zampelli, E.M. Performance choice, executive bonuses and corporate leverage. J. Corp. Financ. 2012, 18, 1286–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Yin, Y. The impact of directors’ green experience on firm environmental information disclosure: Evidence from China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 18, 1559–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and Social Responsibility: A Review of ESG and CSR Research in Corporate Finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Guo, C.; Li, B.; Li, H. Cultural inclusivity and corporate social responsibility in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, C. Culture and Sustainability: Evidence from Tea Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Zheng, S.; Guo, C. Regional cultural inclusiveness and firm performance in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Tang, D.Y.; Zhong, R. The Effects of Mandatory ESG Disclosure Around the World. J. Account. Res. 2024, 62, 1795–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y. Interest rate marketization and corporate social responsibility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 83, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Hu, X.; Sun, G. Sustainability Uncertainty and Digital Transformation: Evidence from Corporate ESG Rating Divergence in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Guo, C.; Ye, J.; Ji, C.; Xu, N.; Li, H. How ESG Contribute to the High-Quality Development of State-Owned Enterprise in China: A Multi-Stage fsQCA Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Wang, F.; Usman, M.; Gull, A.A.; Zaman, Q.U. Female CEOs and green innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrank, J.; Kijkasiwat, P. Impacts of green innovation on small and medium enterprises’ performance: The role of sustainability readiness and firm size. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2024, 7, e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, R.; Fang, M. Mapping green innovation with machine learning: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.; Klepper, S. A reprise of size and R & D. Econ. J. 1996, 106, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soete, L. Firm Size and Inventive Activity—Evidence Reconsidered. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1979, 12, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingbani, I.; Salia, S.; Hussain, J.G.; Alhassan, Y. Environmental Tax, SME Financing Constraint, and Innovation: Evidence From OECD Countries. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qian, C.; Chen, G.; Shen, R. How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir)responsibility. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1338–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Hossain, M.; Alam, M.S.; Goergen, M. Does board gender diversity affect renewable energy consumption? J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Funk, P. Beyond the Glass Ceiling: Does Gender Matter? Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. Br. Account. Rev. 2015, 47, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Diversity, Gender, Strategy and Decision Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xie, F. Do women directors improve firm performance in China? J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, R.; Yousfi, O.; Loukil, N.; Omri, A. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, P.B.; Vieito, J.P.; Wang, M. The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 42, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Marchica, M.-T.; Mura, R. CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 39, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernile, G.; Bhagwat, V.; Yonker, S. Board diversity, firm risk, and corporate policies. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 127, 588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Dutta, D.K.; Park, K. Technology-intensive ventures, R&D capability and innovation success: Impact of firm lifecycle stage and CEO involvement. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2023, 35, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Hou, F.; Cai, X. How do patent assets affect firm performance? From the perspective of industrial difference. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 33, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Fu, Y.; Xie, R.; Liu, Y.; Mo, W. The effect of GVC embeddedness on productivity improvement: From the perspective of R&D and government subsidy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 135, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhou, K. Does Firm’s Value Matter with Firm’s Patent Quality in Technology-Intensive Industries? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 1587–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xue, N.I.; Wan, L.C. When less is more: The numerical format effect of tourism corporate donations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2025, 110, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-F.; Li, H.; Liang, S. Any reputation is a good reputation: Influence of investor-perceived reputation in restructuring on hospitality firm performance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 92, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, J.; Jang, S. The determinants of aggressive share buybacks: An empirical examination of U.S. publicly traded restaurant firms. Tour. Econ. 2024, 30, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewally, M.; Gordon, R. Financial impact of partnerships on hospitality firms. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 95, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).