Abstract

Soil degradation in arid ecosystems is a major threat to sustainable development and food security, especially under accelerating climate change. Kazakhstan, where more than 70% of agricultural land suffers from salinisation, erosion, and humus loss, offers a representative case for studying climate-driven degradation. This study quantitatively assessed the influence of air temperature, precipitation, aridity index, and extreme climatic events on soil properties in the arid regions of western Kazakhstan (Atyrau and Mangystau). The analysis integrated long-term meteorological time series (1941–2023) with field and laboratory data (1967–2024) into a harmonised dataset of 1330 records. Principal component analysis (PCA) identified four degradation gradients explaining 73.6% of total variance, while Random Forest and SHAP algorithms quantified variable importance. Mean annual temperature, frequency of arid years, and aridity index were the strongest predictors of humus, salinity, pH, and CO2 parameters, with climate factors accounting for up to 30% of soil variability. The findings demonstrate that climatic stressors are the main drivers of soil degradation in arid zones, with climate factors explaining up to 30% of the variability in key soil properties (humus, salinity, pH, and CO2)—a substantial proportion that underscores their dominant role relative to local geochemical and anthropogenic influences. The proposed hybrid PCA—Random Forest/SHAP framework provides a robust tool for analysing climate–soil interactions and supports the design of adaptive land-use strategies to achieve Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) in Kazakhstan and other arid regions.

1. Introduction

Soil degradation in the arid and semi-arid regions of the world represents one of the most serious threats to sustainable development, food security, and the preservation of ecosystem services in the 21st century. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization [], approximately 25% of the global land area has already undergone various forms of degradation, while arid lands now cover almost 40% of the Earth’s surface, providing livelihoods for more than two billion people. Recent global assessments indicate that the combined impact of climate change and anthropogenic land-use transformation has affected over 5 million km2 of land, underscoring the magnitude and accelerating pace of degradation processes [].

Central Asia is widely recognised as one of the world’s most vulnerable regions, where more than 60% of the land is already experiencing varying degrees of degradation, including salinisation, wind erosion, and desertification []. Kazakhstan, the largest country in the region, is under particular pressure: around 75% of its agricultural land exhibits signs of degradation, with more than 35 million hectares affected by salinisation and about 24 million hectares by wind erosion []. These processes have been further exacerbated by a recorded rise in air temperature, declining precipitation, and an increase in extreme weather events [].

Within the broader context, the western regions of Kazakhstan—the Atyrau and Mangystau provinces—warrant special attention. The Atyrau region, influenced by the Caspian Sea, is characterised by widespread salinisation and sodicity, affecting roughly 40% of its agricultural land []. The Mangystau region, by contrast, experiences extreme aridity, very low precipitation (below 150 mm per year), and a high frequency of dust storms (up to 25 days annually), making it one of the most climatically vulnerable areas in Central Asia [,].

Despite the substantial body of research accumulated to date, studies of soil degradation in Central Asia have often focused on individual processes such as salinisation [], deflation [], or erosion [] or on analyses of climate trends [] conducted in isolation from soil characteristics. In other regions with comparable climatic and landscape conditions (for example, arid and semi-arid zones of northern China, Iran and Middle East), multiple studies have examined the interactions between climatic variables and soil properties, and to the application of modern statistical and machine learning methods capable of interpreting complex, non-linear relationships [,,,].

The aim of this study is therefore to quantitatively evaluate the contribution of climatic factors—air temperature, precipitation, aridity index, and extreme climatic events—to soil degradation in the arid regions of western Kazakhstan. To achieve this, we employed integrative data-analysis techniques: classical principal component analysis (PCA) to identify latent degradation gradients, and interpretable machine learning (Random Forest with SHAP analysis) to attribute and quantify the contribution of climatic predictors.

The scientific novelty of this work lies in the combined application of PCA and SHAP, which allows for the simultaneous identification of structural axes of degradation and the elucidation of non-linear mechanisms of climate–soil interactions. The results obtained offer valuable insights for the implementation of Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) strategies and for promoting sustainable land-use practices in Kazakhstan and other arid regions of the world.

1.1. Study Area

1.1.1. Physical and Geographical Context

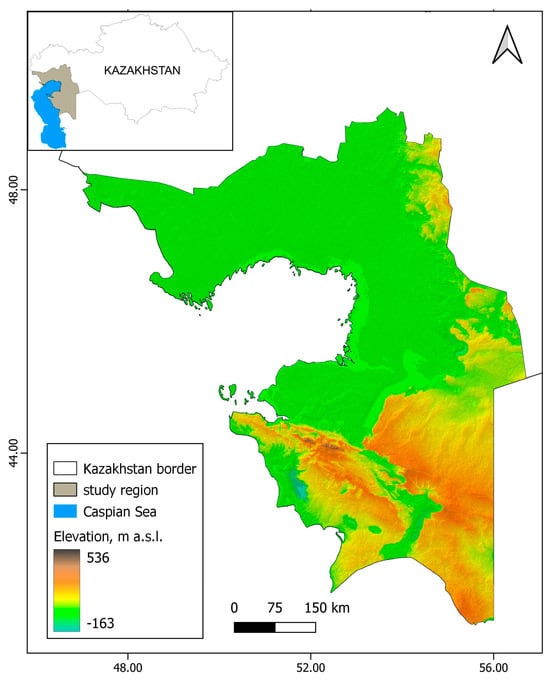

The study area encompasses the western regions of Kazakhstan—the Atyrau and Mangystau provinces (Figure 1), which are characterised by extremely arid climatic conditions and high vulnerability to climate-driven degradation processes []. The Atyrau region lies within the Caspian Depression and is distinguished by its predominantly flat topography, comprising alluvial-deltaic plains of the Ural River basin. The geological structure consists of alternating marine and continental sediments, which contribute to the formation of saline and sodic soils. The soil cover is represented mainly by Gypsisol, calcic, sodic and Solonchak calcic sodic soils [] with a small presence of Cambisol calcaric, sodic soils in the northern part of the Atyrau Region, Fluvisol gleyic, coastal soils along the Caspian Sea shoreline, as well as solonetzes and solonchaks that are strongly affected by groundwater and secondary salinization processess [,].

Figure 1.

Study region.

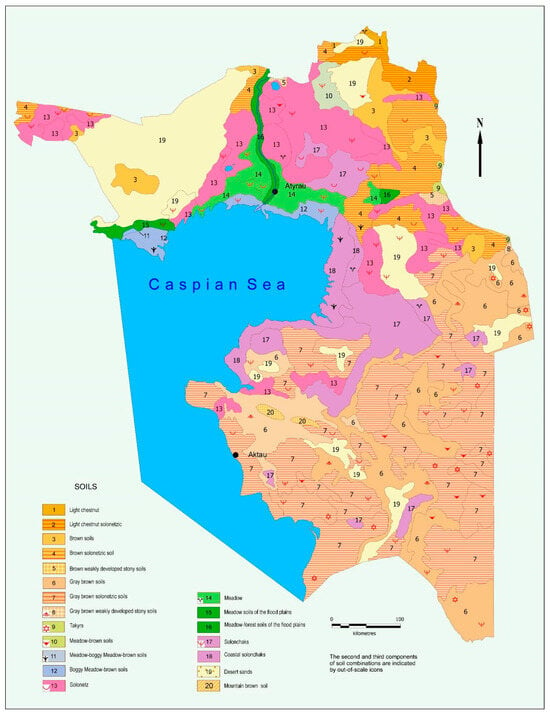

The Mangystau region exhibits a more complex geological and geomorphological structure, represented by carbonate plateaus, residual landforms, and karst basins []. Its geological foundation is composed mainly of Cretaceous and Palaeogene carbonate formations, which, when combined with extreme aridity, result in soils of low natural fertility. The dominant soil types include Gypsisol calcic, sodic and Solonchak calcic, sodic soils, Solonchaks, Solonetzes, and Vertisols takyrik soils, all of which contain very low levels of organic matter. Land-use in the region is primarily associated with pastoral livestock grazing and the oil and gas industry, both of which impose substantial anthropogenic pressure on fragile ecosystems. The spatial distribution of soil types is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Soil map of the study area.

1.1.2. Climatic Background

Both provinces experience a sharply continental climate, though with notable regional distinctions. In the Atyrau region, the Caspian Sea exerts a moderating influence, producing milder winters and slightly higher annual precipitation (180–250 mm year−1). Precipitation is strongly seasonal, with maxima in spring and autumn. Temperatures vary considerably between years, with periodic occurrences of extremely hot summers and severe winter frosts [,].

The Mangystau region, by contrast, experiences an even more severe and arid climate, where annual precipitation rarely exceeds 150 mm, accompanied by high interannual variability. Summer air temperatures frequently surpass +40 °C, while winters remain cold and largely snow-free. The area is further characterised by a high frequency of droughts, dry winds, and dust storms (up to 20–25 days year−1), making climatic stress a dominant driver of soil degradation []. Previous studies in this region have mainly focused on assessing drought frequency [], aeolian dust and sand-storm processes [] and salinization dynamics under arid conditions []. However, these studies largely relied on meteorological and remote-sensing observations without detailed integration of soil datasets.

1.1.3. Current Challenges

Soil degradation processes in the study regions result from a complex interplay of natural and anthropogenic factors. In the Atyrau region, the primary challenges are salinisation and sodicity, caused by rising groundwater levels and inefficient irrigation practices []. In Mangystau, deflation and wind erosion predominate, intensified by vegetation degradaton and overgrazing pressure []. Additional disturbances stem from oil and gas extraction and associated infrastructure development, which further transform soil and landscape systems [].

Collectively, the Atyrau and Mangystau provinces constitute contrasting yet complementary model territories for examining climate-driven soil degradation. The combination of distinct geological settings, extreme aridity, and strong anthropogenic impacts makes this area a unique natural laboratory for analysing climate–soil interactions and developing adaptive strategies for sustainable land-use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Data

Two principal datasets were used for the analysis:

- (1)

- climatic time series obtained from meteorological stations in the Atyrau and Mangystau regions covering the period 1941–2023, and

- (2)

- soil data collected by the U.U. Uspanov Kazakh Research Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry, complemented by field surveys and laboratory analyses undertaken between 1967 and 2024.

The following climatic predictors were selected: mean annual air temperature (ann_temp, °C), annual precipitation (ann_prec, mm), temperature and precipitation trends calculated using the moving average method (temp_trend, prec_trend), the de Martonne aridity index (IDM), binary indicators of abnormally hot (is_hot_year) and dry years (is_dry_year), and an integrated temperature–precipitation interaction index (temp_prec_interaction), calculated as the product of standardized annual mean temperature and annual precipitation (temp_prec_interaction = z_ann_temp x z_ann_prec). This suit of variables represents the key climatic drivers of degradation processes in arid ecosystems.

Temperature and precipitation are fundamental regulators of water and carbon balance []; their long-term trends capture gradual climatic shifts [], while the aridity index serves as a well-established measure of climatic stress affecting soils and vegetation []. Extreme years, identified following ETCCDI recommendations, represents climatic anomalies that heighten degradation risk []. The inclusion of the temp_prec_interaction variable enables the analysis of non-linear synergetic effects that are critical for the processes such as humus depletion, salinisation, and erosion []. All climatic indicators were synchronised with the year of soil sampling, ensuring the comparability of climatic and soil datasets.

Soil data were obtained through field sampling and laboratory verification across 266 sampling sites, comprising more than 1330 individual soil profiles covering the main soil types of the study region—solonetzes, solonchaks, and arenosols. Samples were taken from genetic horizons and subsequently analysed under controlled laboratory conditions.

Four key variables were selected as indicators of soil degradation: humus content (%), total soluble salts (%), pH, and CO2 content (%). These parameters are highly sensitive to aridification and thus serve as diagnostic markers of the principal degradation mechanisms.

- Humus content reflects the level of organic matter and the soil’s resistance to erosion and fertility loss. Rising temperatures and declining moisture in arid environments accelerate organic matter mineralisation, leading to humus depletion and declining agricultural productivity [,,].

- Total soluble salts indicate secondary salinisation, particularly pronounced under reduced surface runoff and high evaporation typical of arid climates [,].

- pH characterises the acid-alkaline regime, which in arid conditions tends to shift towards alkalinity due to carbonate and salt accumulation, thereby reducing nutrient availability and altering microbial communities [,].

- CO2 reflects soil respiration and organic matter mineralisation; under aridification, it often declines because of moisture limitation, which suppresses of microbial activity and slows the carbon cycle [,].

Together, these variables represent the key manifestations of aridification—humus loss, salinisation, alkalisation, and reduced soil carbon function—allowing assessment of soil system vulnerability and supporting adaptive land management strategies in arid regions.

2.2. Data Processing

To ensure comparability, climatic and soil indicators were combined into a single harmonised database comprising 1428 original observations. Each observation corresponded to a soil sample spatially and temporally correlated with the nearest meteorological station by geographical coordinates and sampling year, which allowed for both special and temporal variability in climate–soil interactions to be taken into account [].

Of these, 98 observations (6.9%) contained missing values for at least one variable. After applying the listwise deletion method, the final sample consisted of 1330 complete records. This approach was chosen to preserve data integrity and prevent bias caused by imputation in multidimensional analyses sensitive to artificial data structures (e.g., PCA and Random Forest) [,]. To verify the validity of this decision, a sensitivity analysis was performed: an alternative database was formed with missing values restored using the nearest neighbour method (k-NN, k = 5) using the scikit-learn library. Re-running PCA and Random Forest on the imputed sample (n = 1428) showed high consistency of results: the four principal components explained 73.1% of the variance (compared to 73.6% in the original data), and the ranking of factors by SHAP importance values remained unchanged in order and magnitude (Spearman’s coefficient p > 0.98 for all soil indicators). The results confirm that the use of listwise deletion did not introduce systematic biases.

The final sample size (n = 1330) ensured a reliable ratio of observations to variables (>30:1), which exceeds the recommended values for multivariate analysis methods such as PCA and Random Forest and guarantees statistical stability and generalisability of the results. Prior to statistical analysis, all variables were standardised using z-transformation, which eliminated scale differences and ensured comparable interpretation in subsequent analysis [,].

2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to identify latent factors governing the relationships between climatic and soil indicators. PCA is widely used in ecological and climatic research owing to its ability to reduce data dimensionality and detect integral gradients of variability that are not discernible through single-variable analysis [,]. In arid regions, where degradation results from the interaction of climate aridification, humus loss, salinisation, and pH alteration, PCA effectively separates climate-driven signals from local soil effects, thereby identifying dominant degradation trajectories []. The input matrix included standardised climatic indicators (mean temperature, precipitation, aridity index, trends and extreme events) and soil indicators (humus, salts, pH, CO2).

The number of retained components was determined using Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue > 1), the scree-plot test [], and the requirement of a cumulative variance explanation ≥ 70%. No orthogonal (e.g., Varimax) or oblique rotation was applied, as the goal was to preserve the original geometric structure of the data and facilitate direct interpretation of loadings in the context of climate–soil interactions. Visualisation was achieved using scree plots and biplots [], enabling joint interpretation of observation clustering and variable loadings. This procedure identified integral axes of climate–soil interaction, representing both climatic and geochemical degradation gradients, which provided a basis for subsequent scenario modelling.

2.4. Random Forest and SHAP Analysis

The Random Forest ensemble algorithm [] was employed to model non-linear relationships between climatic factors and soil properties. The models were implemented in Python 3.11 using the scikit-learn library (RandomForestRegressor) with the following hyperparameters: n_estimators = 500, max_depth = None (full tree growth), min_samples_split = 2, min_samples_leaf = 1, max_features = “sqrt”, and random_state = 42 (for reproducibility of results).

Hyperparameter tuning was performed using 5-fold cross-validation and grid search over the ranges: n_estimators ∈ {100, 300, 500}, max_depth ∈ {10, 20, None} and max_features ∈ {“sqrt”, “log2”}. The final configuration (shown above) was selected based on the lowest mean cross-validation error (MSE).

The initial dataset (n = 1330) was divided in an 80/20 ratio into training and test samples using stratified sampling by region to maintain a balance between areas. The quality of the models was evaluated on a delayed test sample using the following metrics: coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE). The values obtained (R2 = 0.68–0.74 for different soil indicators) confirmed the high predictive accuracy of the models and the absence of overfitting.

The Random Forest method is resistant to noise and multicollinearity, which makes it particularly suitable for environmental datasets where variables are often interdependent and irregularly distributed []. In contrast to classical regression techniques, Random Forest allows for threshold and interactive effects characteristic of degradation processes under aridification. For each soil parameter (humus, salts, pH, CO2), a separate model was constructed in which climatic parameters were used as independent inputs.

The models were interpreted using the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method [], which quantitatively assesses the marginal contribution of each feature to the model output.

SHAP values were calculated using the Python package SHAP (version 0.42.1; TreeExplainer) on the full training dataset. Unlike traditional measures of variable importance, the SHAP method allows us to determine not only the strength but also the direction of influence of each factor, as well as to identify nonlinear dependencies. Its application is particularly valuable in arid regions, where individual climatic factors can have multidirectional effects on various soil properties []. Thus, the combined Random Forest—SHAP approach provides an optimal balance between prediction accuracy and model interpretability, offering substantial value for applied climate-ecological assessments and adaptive land-management planning.

2.5. Justification of the Hybrid Approach

The integration of PCA with Random Forest and SHAP interpretation was motivated by need for a comprehensive analytical framework to examine soil degradation under aridification. PCA identifies underlying gradients and structural patterns of variability [], but it is limited in accounting for non-linear dynamics and does not quantify the magnitude of variable influence. Conversely, Random Forest provides high predictive performance and resilience to collinearity, while SHAP ensures interpretability through quantitative attribution of each factor’s contribution [,].

Combining these methods thus capitalises on their complementary strengths: PCA elucidates the integral climate–soil axes and categorises degradation scenarios, whereas Random Forest/SHAP quantifies the influence of temperature, precipitation, aridity, and extreme climatic events on key soil properties. This hybrid framework overcomes the limitations of each method in isolation, offering a more reliable and transparent understanding of degradation mechanisms under climate change.

Implemented for the first time in the arid ecosystems of Central Asia, this hybrid approach demonstrates high interpretative potential and practical applicability for both scientific investigation and adaptive land-management design.

2.6. Software

All analyses were conducted using Python 3.11.

- (i)

- scikit-learn library []—implementation of PCA and Random Forest;

- (ii)

- shap package []—SHAP interpretation;

- (iii)

- matplotlib and seaborn—visualisation;

- (iv)

- pandas—data processing and management.

3. Results

The integration of climatic and soil datasets enabled a comprehensive characterisation of degradation processes in the arid regions of western Kazakhstan. To distinguish the respective roles of long-term climatic trends, interannual extremes, and regional geochemical features, a combined analytical framework was applied, incorporating Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and machine learning techniques (Random Forest with SHAP interpretation). This design ensured both the identification of latent structural axes within the climate–soil system and the quantitative attribution of the climatic and environmental factors underlying the observed and modelled transformations in soil properties.

The results presented below summarise (1) the dynamics of key soil indicators, (2) the dominant climatic gradients driving degradation processes, and (3) the relative explanatory power of individual predictors. Together, these findings provide an empirical basis for assessing the vulnerability of arid soils under conditions of progressive aridification and for evaluating the potential effectiveness of adaptive land-management strategies.

3.1. Climatic and Geochemical Gradients Identified by PCA

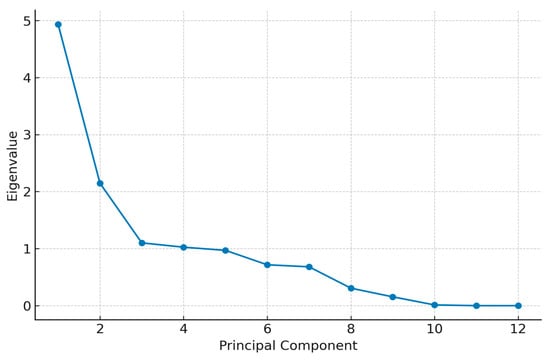

PCA performed on the combined climatic-soil dataset from the Atyrau and Mangystau regions revealed that four components were the most informative (Figure 3). According to Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue > 1) and the scree-plot test, only these components were retained for interpretation. Together, PC1–PC4 explain 73.6% of the total data variance, distributed as follows:

Figure 3.

Scree plot of eigenvalues for the principal component analysis (PCA). The first four components exceed Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue > 1) and together explain more than 70% of the total variance, confirming their significance for interpretation.

- PC1: 40.9% of the variance;

- PC2: 17.8% of the variance;

- PC3: 8.6% of the variance;

- PC4: 6.3% of the variance.

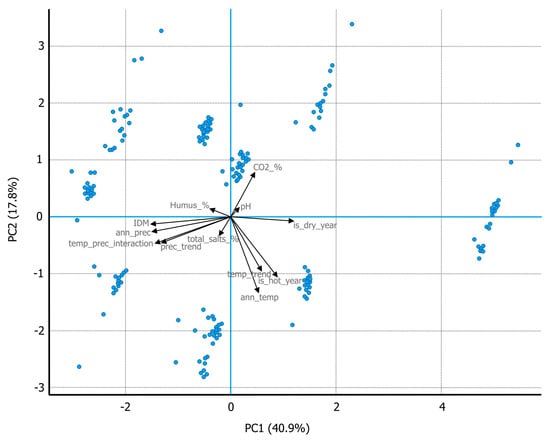

The biplot (Figure 4) shows compact clustering of climatic and soil variables, with vectors representing their relative loadings on the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2).

Figure 4.

Biplot of the first two principal components (PC1 vs. PC2). Arrows represent variable loadings, while points correspond to individual climate–soil observations.

The plot highlights the separation of climatic and soil variables into distinct clusters, indicating the combined influence of climatic and geochemical gradients.

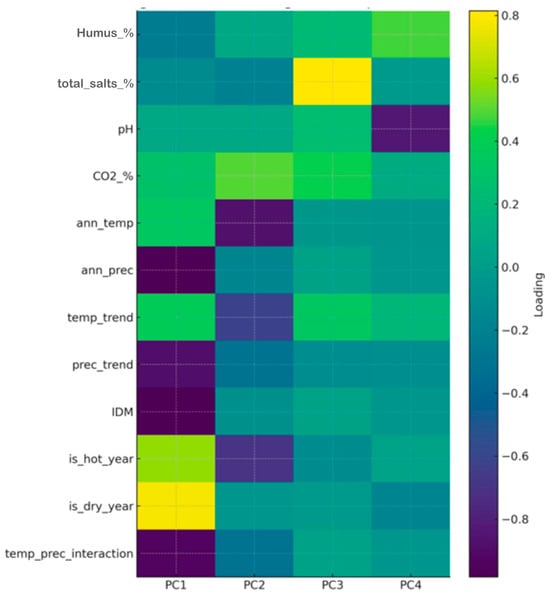

The distribution of variable loadings across the first four components is illustrated in Figure 5. The strongest loadings are associated with climate-trend indicators and extreme-year variables, alongside soil-composition parameters.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of variable loadings for the first four principal components (PC1-PC4) derived from standardized climatic and soil variables. Each cell represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between a variable and a principal component (range: −1 to +1). Yellow shades indicate strong positive loadings (>+0.5), dark purple shades indicate strong negative loadings (<−0.5), and green-blue tones correspond to weak or moderate associations near zero. Variables with |loading| > 0.5 were considered significant contributors to the respective component. The heatmap reveals distinct clusters: PC1 is dominated by aridity and extreme-year indicators (e.g., is_dry_year, is_hot_year), PC2 by soil salinity and geochemical properties, PC3 by precipitation-related variables, and PC4 captures secondary interactions involving the temperature-precipitation coupling.

Overall, PCA enabled the identification of key axes of variability within the climate–soil system and the determination of individual variable contributions to their formation.

3.2. Quantitative Attribution of Climatic Drivers (Random Forest–SHAP Results)

While PCA revealed the latent structure of soil degradation drivers, its linear framework limits the capture of complex non-linear interactions typical of arid ecosystems. To address this, the subsequent stage of analysis employed machine-learning algorithms, particularly the Random Forest ensemble for modelling and SHAP for interpretation. This approach translates the latent PCA structures into specific quantitative estimates of the influence of individual climatic drivers on soil degradation processes.

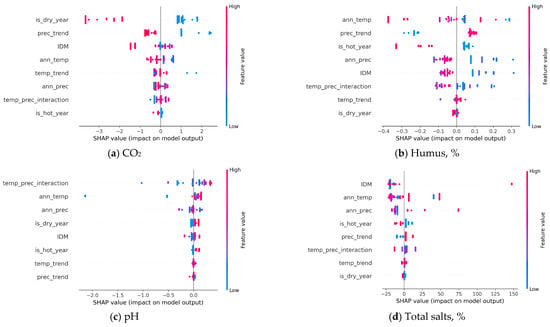

Figure 6 presents the contribution of climatic variables—including the de Martonne aridity index and extreme events—as well as regional factors, to the formation of soil properties (CO2, humus (%), pH, and total salts (%)) in the Atyrau and Mangystau regions, based on SHAP interpolation of the Random Forest model.

Figure 6.

SHAP summary plots for the Random Forest models predicting soil properties: (a) CO2, (b) humus (%), (c) pH, and (d) total salts (%). Each subplot shows the distribution of SHAP values for climatic predictors across 1330 observations; features are ordered by mean absolute SHAP value (global importance). The x-axis displays individual SHAP values, indicating the direction and magnitude of each predictor’s effect on the model output (positive = increases prediction, negative = decreases). The colour scale encodes the feature value (red = high, blue = low), revealing non-linear relationships. Predictors include mean annual temperature (ann_temp), precipitation (ann_prec), their trends (temp_trend, prec_trend), the moisture/aridity index (IDM), extreme-year indicators (is_hot_year, is_dry_year), and the temperature–precipitation interaction (temp_prec_interaction). The plots reveal that aridity-related indicators (is_dry_year, IDM) and long-term temperature trends exert the strongest influence on soil composition, highlighting their role as key drivers of regional degradation processes.

3.2.1. CO2 Content (%)

SHAP analysis (Figure 6a) showed that the main predictor of soil CO2 content is the frequency of abnormally dry years (is_dry_year, 19.3%), which has a pronounced negative contribution (SHAP ≈ −2.24), indicating suppression of soil respiration and weaking of the carbon cycle under conditions of moisture deficit. The interaction between temperature and precipitation (temp_prec_interaction, 15–17%) showed a secondary negative effect, confirming that combined hydrothermal stress further limits CO2 release. The average annual temperature (ann_temp, ≈ 12%) made a positive contribution (SHAP ≈ +1.0), reflecting increased mineralisation and microbial activity under warmer conditions., while the de Martonne aridity index (IDM, 8%) had a moderate negative effect, consistent with reduced moisture availability.

Regional differences are quite pronounced: the influence of the Atyrau and Mangystau regions was approximately equal (17–18%), reflecting the specific local microclimatic and edaphic conditions affecting CO2 dynamics.

Overall, the SHAP results confirm that extreme droughts are the main factor suppressing soil CO2 emissions, while rising temperatures act as a compensatory mechanism that enhances mineralisation. This interaction determines the response of the carbon cycle to climatic aridisation in the western regions of Kazakhstan.

3.2.2. Humus Content (%)

Humus dynamics were primarily determined by mean annual temperature (ann_temp, 28.6%), with a positive contribution (up to +0.14), and by the aridity index (IDM, 17.7%), where higher IDM values (up to +0.30) favoured organic matter accumulation. The temperature–precipitation interaction term (temp_prec_interaction, 11.5%) further enhances this effect, whereas abnormally hot years (is_hot_year, 9.3%) reduced humus content (−0.21), consistent with accelerated decomposition.

3.2.3. pH

The dominant predictor of pH was the temperature–precipitation interaction (temp_prec_interaction, 40.6%), with a positive contribution (up to +0.34) associated with salt leaching and carbonate dynamics. Mean annual temperature (25.2%) and precipitation (16.2%) also influenced pH (+0.14 and −0.03, respectively), while aridity index (9.5%) exerted a minor amplifying effect (+0.01). Extreme events had limited influence (is_hot_year 2.3%, is_dry_year 2.0%).

3.2.4. Total Soluble Salts (%)

Salt accumulation was most strongly driven by the aridity index (IDM, 38.8%), exhibiting a negative contribution (−19.1) at low values, indicating that severe aridity promotes salt build-up. Mean annual temperature (25.9%) and precipitation (18.9%) further modulated salinity (+0.26 and −7.7, respectively), while abnormally hot years (is_hot_year, 5.1%) contributed positively (+1.79). The influence of regional factors was negligible (<0.01%).

3.2.5. Interpretation of SHAP Variability

A general analysis of the SHAP value distributions demonstrated pronounced non-linearity in the relationships between climatic predictors and soil responses. The broadest SHAP range was recorded for salt content (−21.6…+22.5), indicating high climatic sensitivity, whereas humus exhibited the narrowest range (−0.25…+0.35), reflecting relative stability.

4. Discussion

The findings underscore the central role of climate in driving soil-degradation processes in the arid ecosystems of the Atyrau and Mangystau regions. By triangulating long-term field observations with climatic time series and scenario-based modelling, the study provides new evidence that gradual warming and the increasing frequency of extremes accelerate humus depletion, salinisation, and shifts in the acid-alkaline balance. The combined use of PCA and SHAP enabled the interpretation of both structural gradients of variability and non-linear, context-dependent soil responses to climatic stressors. Below, we situate these results within regional and global studies, examine the interplay of climatic, lithological, and anthropogenic factors, and outline implications for Land Degradation Neutralisation (LDN) strategies, thereby offering an integrative perspective on how climate processes may transform Central Asian soil systems in the coming decades.

4.1. Interpreting PCA-Derived Degradation Scenarios

PCA identified the leading axes of variability in the climate–soil system of the two western Kazakh regions. PC1 (40.9% of the variance) captured an integral climate–soil gradient dominated by temperature metrics and extreme-year indicators (is_hot_year, is_dry_year). High loadings for mean annual temperatures, temperature trend, and extreme-year variables indicate the primacy of thermal controls, while the contribution of soil pH suggests climate-linked transformation of soil reactions. These patterns align with prior PCA-based assessments that integrate climatic and soil data [,]. This leading component reflects the integral aridisation gradient affecting western Kazakhstan, where sustained temperature increases and more frequent hot and dry years jointly intensify evaporation, moisture deficiency and mineralisation of organic matter. The relationship between pH and the same axis indicates progressive alkalisation associated with the accumulation of carbonates during prolonged drying. Taken together, these relationships show that PC1 describes a complex climatic-edaphic trajectory characterising the transition from subarid to hyper arid soil regimes.

PC2 (17.8%) was associated mainly with soil characteristics (humus, CO2, total salts) and, to a lesser extent, precipitation, representing a ‘geochemical axis’ of variability typical of arid pedogenesis. Comparable structures have been reported in soil quality assessments using multivariate methods [].

PC3 (8.6%) and PC4 (6.3%), though explaining smaller proportions of variance, captured interactions between climatic and soil factor: PC3 related chiefly to precipitation trends and the aridity index (IDM), whereas PC4 reflected composite effects involving the temperature-precipitation interaction term. Retention criteria were satisfied (Kaiser’s criterion; scree-plot test) [].

Comparative evidence [] supports the view that climatic trends coupled with soil properties generate stable degradation trajectories in arid ecosystems—with the temperature-driven axes consistent with the leading role of aridity.

On this basis, three scenarios emerge:

- Climatic scenario—dominated by temperature trends and climatic extremes, indicating heightened vulnerability of soils to anomalies and sustained warming.

- Geochemical scenario—governed by intrinsic soil properties (humus, carbonate status, salts), integrating internal degradation processes (salinisation, organic-matter loss) that can persist independently of interannual variability.

- Combined scenario—arising from interactions among precipitation trends, IDM, and temperature-precipitation coupling, whereby climatic extremes compound geochemical vulnerabilities.

Thus, PCA moves the analysis beyond single indicators to integrated scenarios in which anomalies and long-term climatic trends act as principal drivers of degradation [].

4.2. Interpreting Climatic Drivers via Random Forest–SHAP

Random Forest and SHAP complemented the PCA factor structure by quantifying feature-level effects. Humus content was chiefly influenced by mean annual temperature and aridity (IDM), confirming the sensitivity of soil organic matter to aridification. For pH, the temperature–precipitation interaction was the key predictor, linking acidity-alkalinity shifts to the hydrothermal balance. Salinity was primarily controlled by aridity (IDM), while CO2 was most responsive to dry-year extremes. Collectively, these results show that rising temperatures and precipitation deficits drive humus depletion, salinisation, and carbon-cycle modification, consistent with a multi-factor, non-linear degradation regime.

In combination, PCA and Random Forest/SHAP demonstrate that climate both structures general degradation scenarios and exerts specific, parameter-dependent impacts. This supports the hypothesis that aridification is the dominant driver of soil-system transformation and highlights the value of pairing multivariate statistics with interpretable machine learning.

To explicitly link SHAP-based feature contributions with the PCA-derived degradation scenarios, Table 1 maps the dominant drivers identified by each method.

Table 1.

Correspondence between PCA degradation axes and SHAP-identified climatic drivers.

This cross-method validation confirms that the latent structural gradients detected by PCA are mechanistically driven by the same climatic stressors quantified via SHAP.

Our patterns are congruent with global and regional evidence. Huang et al. [] reported rapid expansion of arid lands and temperature-precipitation controls on degradation; our PC1 (>40%) reflects this climatic gradient. Derakhshan et al. [] found temperature and aridity to be principal determinants of soil-carbon loss, matching our humus models; similar relationships were noted by Lal []. PC2-based salinisation and alkalisation accord with Qadir et al. [] and regionally []. PC3’s precipitation signature is consistent with SPEI-based drought diagnostics [], linking moisture variability with pH and leaching dynamics. The influence of extreme dry years (PC4; CO2 SHAP) echoes Maestre et al. [] on respiration and microbial fluctuations in global drylands. Finally, the multi-dimensional nature of our scenarios is in line with [], underscoring the need to account for interacting processes.

4.3. Study Limitations

Despite the comprehensive nature of the analysis, several limitations should be noted. First, the database focused on four soil indicators (humus, total soluble salts, pH, CO2). While diagnostic of key degradation mechanisms, these do not capture aggregate stability, biodiversity, or macro-/micro-nutrient status; including such metrics would enrich process attribution.

Second, the spatial scope was restricted to two western regions (Atyrau and Mangystau). These are representative of arid conditions, but findings should not be over-generalised to all Kazakhstan or Central Asian drylands without further validation.

Third, although climate (1941–2023) and soil (1967–2023) records offer a long-term perspective, full temporal synchronicity is not always achievable, potentially attenuating climate–soil signal detection; denser temporal coupling would enhance statistical power.

Fourth, listwise deletion for missing data reduces the effective sample size and may affect model stability, even though it mitigates systematic bias.

Finally, explicit socio-economic and anthropogenic drivers (e.g., land-use intensity, irrigation practices, grazing pressure) were not modelled, yet they can significantly modulate climate–soil linkages and merit inclusion.

4.4. Future Research Directions

- (i)

- Broaden soil indicators to include microbial diversity, aggregate structure, hydraulic traits (infiltration, water-holding capacity), and nutrient pools, enabling finer-grained diagnosis of degradation pathways.

- (ii)

- Expand spatial coverage beyond Atyrau and Mangystau to additional Kazakhstan and Central Asian drylands, facilitating inter-regional comparison and tests of pattern generality.

- (iii)

- Integrate Earth Observation and climate scenarios (e.g., Sentinel/Landsat/MODIS, CMIP6 under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5) to enable spatio-temporal monitoring and forward projections.

- (iv)

- Advance analytical methodology through gradient boosting, deep learning, and causal-inference frameworks, and couple climatic with socio-economic models for interdisciplinary attribution.

- (v)

- Operationalise results via decision-support tools for regional authorities, translating risk maps and vulnerability indices into targeted, costed adaptation portfolios.

4.5. Implications for Adaptive Management and Policy

The results are directly actionable for adaptive land management under intensifying aridification. Where humus loss is dominant (temperature- and aridity-driven), priorities include organic-matter retention, regenerative practices, and vegetation cover restoration. Where salinisation/alkalisation prevails, focus on irrigation efficiency, groundwater-level control, and reclamation measures.

Because degradation reflects interacting drivers rather than single causes, integrated monitoring systems that combine climatic, soil, and socio-economic data are warranted. Hyper-local vulnerability indices derived from the presented framework could inform public planning and target adaptation investments. In western Kazakhstan, where t aridification pressures are acute, deploying the identified degradation scenarios can underpin targeted programmes to preserve soil fertility, buffer extreme events, and stabilise agricultural systems. Embedding these models in routine planning can improve recourse-use efficiency and reduce losses associated with land degradation, thereby supporting LDN objectives and regional food security.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrated that soil degradation in western Kazakhstan is a complex, multidimensional process governed by the combined influence of climatic and geochemical factors. Climate change and the acceleration of aridification represent one of the most serious threats to the sustainability of soil systems in arid regions. The results strongly support the hypothesis that long-term climatic trends and extreme events are primary drivers of soil degradation in western Kazakhstan’s drylands.

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed four integral axes of variability explaining 73.6% of total variance.

PC1 (40.9%) reflected a climate-driven degradation scenario associated with rising temperatures, increasing aridity, and a higher frequency of abnormally hot years.

PC2 (17.8%) described geochemical processes such as salinisation and alkalisation, particularly noticeable in the Atyrau region.

PC3 (9.1%) and PC4 (5.8%) were linked to precipitation dynamics and extreme dry years, influencing the acid-alkaline balance and CO2 content.

This component structure demonstrates that soil degradation under aridification is inherently multidimensional, combining climatic stressors and intrinsic soil chemistry.

Random Forest coupled with SHAP analysis complemented the PCA results, providing quantitative estimates of individual climatic contributions to soil indicators.

- -

- For humus, temperature was the dominant driver, with aridity and extreme heat events as secondary influences.

- -

- For pH, the temperature–precipitation interaction was most significant, underscoring the dependence of the acid-alkaline regime on hydrothermal balance.

- -

- For salts, aridity and precipitation jointly determined accumulation, whereas CO2 levels were most sensitive to extreme drought years.

The consistency between PCA and Random Forest/SHAP outcomes constitutes the study’s most significant result. PCA identified latent degradation scenarios and regional contrasts, while Random Forest/SHAP quantified the relative influence of climatic variables. The convergence of key drivers—temperature, aridity, precipitation, and extreme events—across both approaches enhances methodological reliability, while their different emphases (structural gradients vs. quantitative attribution) yield a complementary, multidimensional understanding of soil degradation.

From a practical standpoint, the findings enable a differentiated approach to adaptive land management.

- -

- In zones dominated by humus depletion linked to warming and aridity, priorities include maintaining soil organic matter through regenerative farming, green manure, mulching, and reduced tillage.

- -

- In regions affected by salinisation and alkalisation, emphasis should be placed on improving irrigation practices, controlling groundwater levels, and implementing reclamation measures.

- -

- In areas most vulnerable to extreme droughts, the focus should shift towards early-warning systems and water-saving technologies.

From a scientific perspective, this research confirmed the high efficacy of integrating PCA and Random Forest/SHAP as a hybrid methodological framework. Multivariate statistics alone cannot adequately capture non-linear relationships, whereas machine-learning models without interpretive structure lack explanatory depth. Combining the two approaches harnesses the systematic dimension-reduction power of PCA and the interpretability of SHAP-based ensemble modelling.

The study also identifies several priorities for future research:

- Expanding the suite of soil indicators to include biological diversity, profile morphology, and micronutrient content.

- Broadening the spatial scope to encompass other arid areas of Central Asia, enabling the identification of interregional degradation patterns.

- Incorporating remote-sensing and CMIP6-based climate scenarios to model long-term dynamics and forecast degradation trajectories.

- Integrating socio-economic variables—such as land-use intensity, irrigation regimes, and grazing pressure—to develop interdisciplinary degradation models.

Overall, the research confirmed the leading role of climatic factors in soil degradation across arid landscapes. Degradation results from the combined influence of temperature rise, increased aridity, reduced precipitation, and climatic extremes, manifesting through humus depletion, salinisation, alkalisation, and carbon-cycle disruption. The integration of PCA and Random Forest/SHAP produced a coherent, multi-layered representation of these processes. Accordingly, the study holds both scientific and practical significance, providing a foundation for adaptive strategies aimed at sustainable land-use and climate-resilient management in arid regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and A.U.; methodology, R.R., A.U. and V.S.; software, V.S., K.P. and Z.R.; validation, K.P., A.Y. and Y.S.; formal analysis, A.U.; investigation, V.S.; resources, K.P.; data curation, A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R., A.U., V.S., K.P. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, R.R., A.U. and Z.R.; visualization, V.S., K.P. and Z.R.; supervision, R.R. and A.U.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, R.R. and Z.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882122, Sustainable development of natural-industrial and socio-economic systems of the West Kazakhstan region in the context of green growth: a comprehensive analysis, concept, forecast estimates and scenarios).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. Overview of Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) in Europe and Central Asia; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, A.L.; Evans, J.P.; De Kauwe, M.G. Anthropogenic climate change has driven over 5 million km2 of drylands towards desertification. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzabaev, A.; Goedecke, J.; Dubovyk, O.; Djanibekov, U.; Le, Q.B.; Aw-Hassan, A. Economics of land degradation in Central Asia. In The Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement; Nkonya, E., Mirzabaev, A., von Braun, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolidated Analytical Report on the State and Use of Land in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023 (Committee for Land Resources Management of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan). Available online: https://cawater-info.net/bk/land_law/files/kz-land2023.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Fu, C.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q.; Dai, A.; Shinoda, M.; Ma, Z.; Guo, W.; Li, Z.; et al. Dryland climate change: Recent progress and challenges: Dryland climate change. Rev. Geophys. 2017, 55, 719–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issanova, G.; Saduakhas, A.; Abuduwaili, J.; Tynybayeva, K.; Tanirbergenov, S. Desertification and Land degradation in Kazakhstan. Sci. J. Pedagog. Econ. 2020, 5, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bao, A.; Jiapaer, G.; Guo, H.; Zheng, G.; Gafforov, K.; Kurban, A.; De Maeyer, P. Monitoring land sensitivity to desertification in Central Asia: Convergence or divergence? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, N. Impacts of dust storms on agriculture: A synthesis. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 575, 05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Quillérou, E.; Nangia, V.; Murtaza, G.; Singh, M.; Thomas, R.; Drechsel, P.; Noble, A. Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Nat. Resour. Forum 2014, 38, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallah, B.; Didovets, I.; Rostami, M.; Hamidi, M. Climate change impacts on Central Asia: Trends, extremes and future projections. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 3191–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Shi, X.R.; Han, F.P.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Increasing aridity, temperature and soil pH induce soil C-N-P imbalance in grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poozesh Shirazi, M.; Enjavinezhad, S.M.; Moosavi, A.A. Chemical fractions of potassium in arid region calcareous soils: The impact of microclimates and physiographic variability. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaeinasab, A.; Bashari, H.; Esfahani, M.T.; Pourmanafi, S.; Toomanian, N.; Aghasi, B.; Jalalian, A. Predicting soil chemical characteristics in the arid region of central Iran using remote sensing and machine learning models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, F.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, H.; Li, M. Variations of soil moisture and its influencing factors in arid and semi-arid areas, China. J. Arid Land 2025, 17, 624–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, R.; Pohl, W. Eine neue Wandkarte der Klimagebiete der Erde nach W. Köppens Klassifikation. Erdkunde 1954, 8, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022; ISBN 979-8-9862451-1-9. Available online: https://www.isric.org/sites/default/files/WRB_fourth_edition_2022-12-18.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Pachikin, K.; Erohina, O.; Adamin, G.; Yershibulov, A.; Songulov, Y. Mapping the Caspian Sea’s North Coast Soils: Transformation and Degradation. In Advances in Understanding Soil Degradation; Innovations in Landscape Research; Saljnikov, E., Mueller, L., Lavrishchev, A., Eulenstein, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saparov, A. Soil Resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Current Status, Problems and Solutions. In Novel Measurement and Assessment Tools for Monitoring and Management of Land and Water Resources in Agricultural Landscapes of Central Asia; Environmental Science and Engineering; Mueller, L., Saparov, A., Lischeid, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonn, I.S.; Kostianoy, A.G.; Kosarev, A.N.; Glantz, M.H. The Caspian Sea Encyclopedia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; p. 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Tank, A.M.G.; Wijngaard, J.B.; Können, G.P.; Böhm, R.; Demarée, G.; Gocheva, A.; Mileta, M.; Pashiardis, S.; Hejkrlik, L.; Kern-Hansen, C.; et al. Daily dataset of 20th-century surface air temperature and precipitation series for the European Climate Assessment. Int. J. Climatol. 2002, 22, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikov, V.; Talanov, Y.; Polyakova, S.; Assylbekova, A.; Kauazov, A.; Bultekov, N.; Musralinova, G.; Kissebayev, D.; Beldeubayev, Y. An Assessment of the Present Trends in Temperature and Precipitation Extremes in Kazakhstan. Climate 2023, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, S.R.; Santos, R.S.; Oliveira, D.M.S.; Souza, I.F.; Verburg, E.E.J.; Pimentel, L.G.; Cruz, R.S.; Silva, I.R. Practices for rehabilitating bauxite-mined areas and an integrative approach to monitor soil quality. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Xia, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Dynamic evolution of recent droughts in Central Asia based on microwave remote sensing satellite products. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issanova, G.; Kaldybayev, A.; Ge, Y.; Abuduwaili, J.; Ma, L. Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Dust Storms and Aeolian Processes in the Southern Balkash Deserts in Kazakhstan, Central Asia. Land 2023, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirkhanov, M.; Zhakypbek, Y.; Tursbekov, S.; Nurpeissova, T. Comparative analysis of the state of desertification of the lands of West and East Kazakhstan. Eng. J. Satbayev Univ. 2025, 147, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issanova, G.; Abuduwaili, J. Aeolian Processes as Dust Storms in the Deserts of Central Asia and Kazakhstan; Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2017; p. 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarch, M.A.A.; Sivakumar, B.; Sharma, A. Droughts in a warming climate: A global assessment of Standardized precipitation index (SPI) and Reconnaissance drought index (RDI). J. Hydrol. 2015, 526, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherlet, M.; Hill, J.; Hutchinson, C.; Reynolds, J.; Sommer, S.; Von Maltitz, G. World Atlas of Desertification: Rethinking Land Degradation and Sustainable Land Management. 2018. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/06292 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Nicholls, N.; Easterling, D.; Goodess, C.M.; Kanae, S.; Kossin, J.; Luo, Y.; Marengo, J.; McInnes, K.; Rahimi, M.; et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 109–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Frew, A.; Yu, H.; Hou, E.; Wen, D. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stabilization and its response to conversion of primary natural broadleaf forests to secondary forests and plantation forests. CATENA 2024, 240, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, F.; Abdi, N.; Toranjzar, H.; Ahmadi, A. Simulating Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics under Climate Change Scenarios in an Arid Ecosystem. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankova, E.I.; Konyushkova, M.V. Climate and soil salinity in the deserts of Central Asia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L. Environmental Soil Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yi, D.; Ye, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, S. Response of spatiotemporal variability in soil pH and associated influencing factors to land use change in a red soil hilly region in southern China. CATENA 2022, 212, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.; Janssens, I. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.T.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Jeffries, T.C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Ochoa, V.; Gozalo, B.; Quero, J.L.; García-Gómez, M.; Gallardo, A.; Ulrich, W.; et al. Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15684–15689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very High Resolution Interpolated Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.E.; Alexander, L.V. On the measurement of heat waves. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 4500–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.A. Missing Data: Five Practical Guidelines. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 372–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal Component Analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, X.; Jiang, M.; He, S.; He, Y. Mechanisms Behind the Soil Organic Carbon Response to Temperature Elevations. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scree Test for the Number of Factors. Multivar. Behav Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, K.R. The biplot graphic display of matrices with application to principal component analysis. Biometrika 1971, 58, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C., Jr.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.K. Book review: Christoph Molnar. 2020. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. Metamorphosis 2024, 23, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Selmy, S.A.H.; Abd Al-Aziz, S.H.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R.; Jesús García-Navarro, F.; Fadl, M.E. Soil Quality Assessment Using Multivariate Approaches: A Case Study of the Dakhla Oasis Arid Lands. Land 2021, 10, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).