Resilience Assessment and Evolution Characteristics of Urban Earthquakes in the Sichuan–Yunnan Region Based on the DPSIR Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

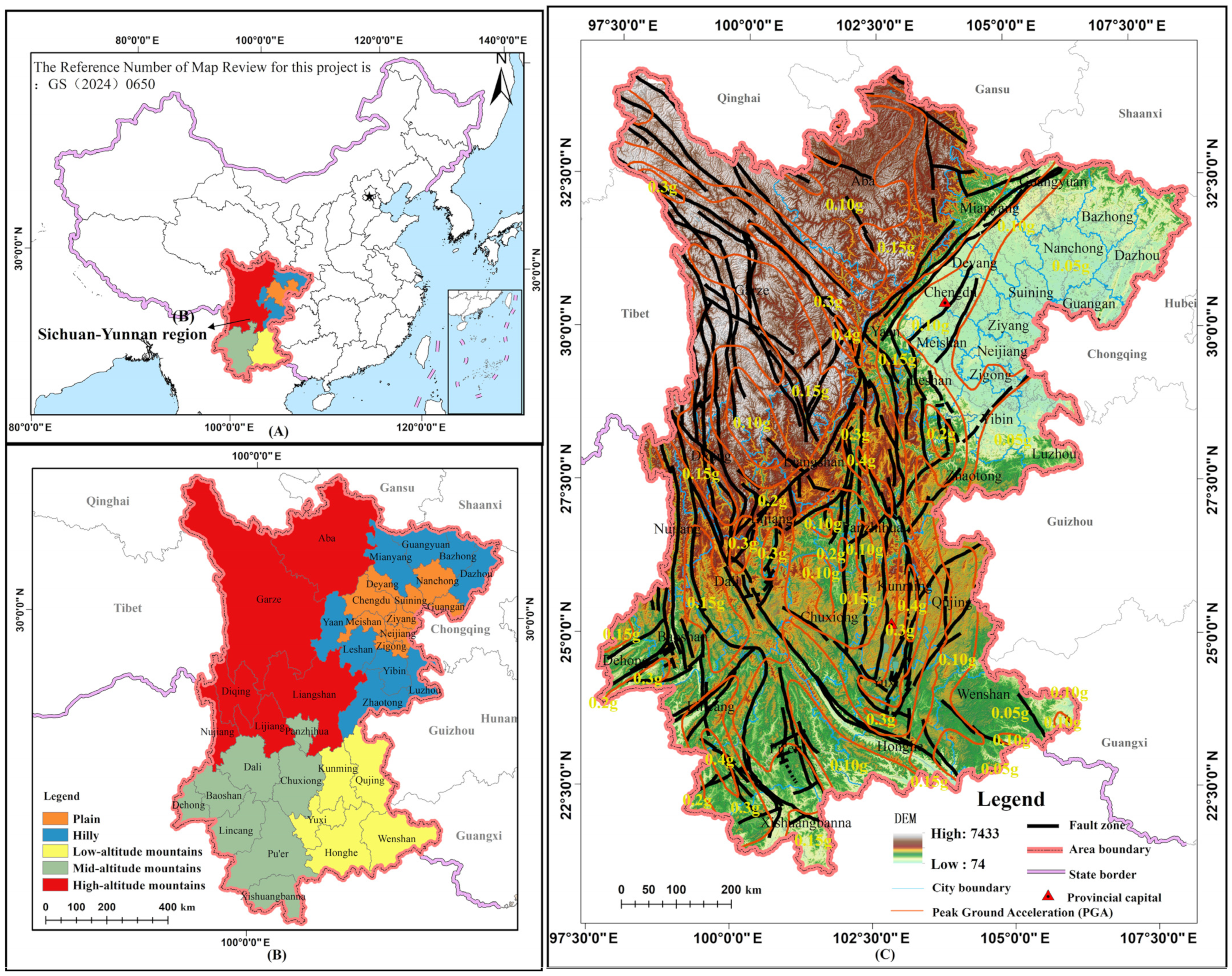

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Methodology

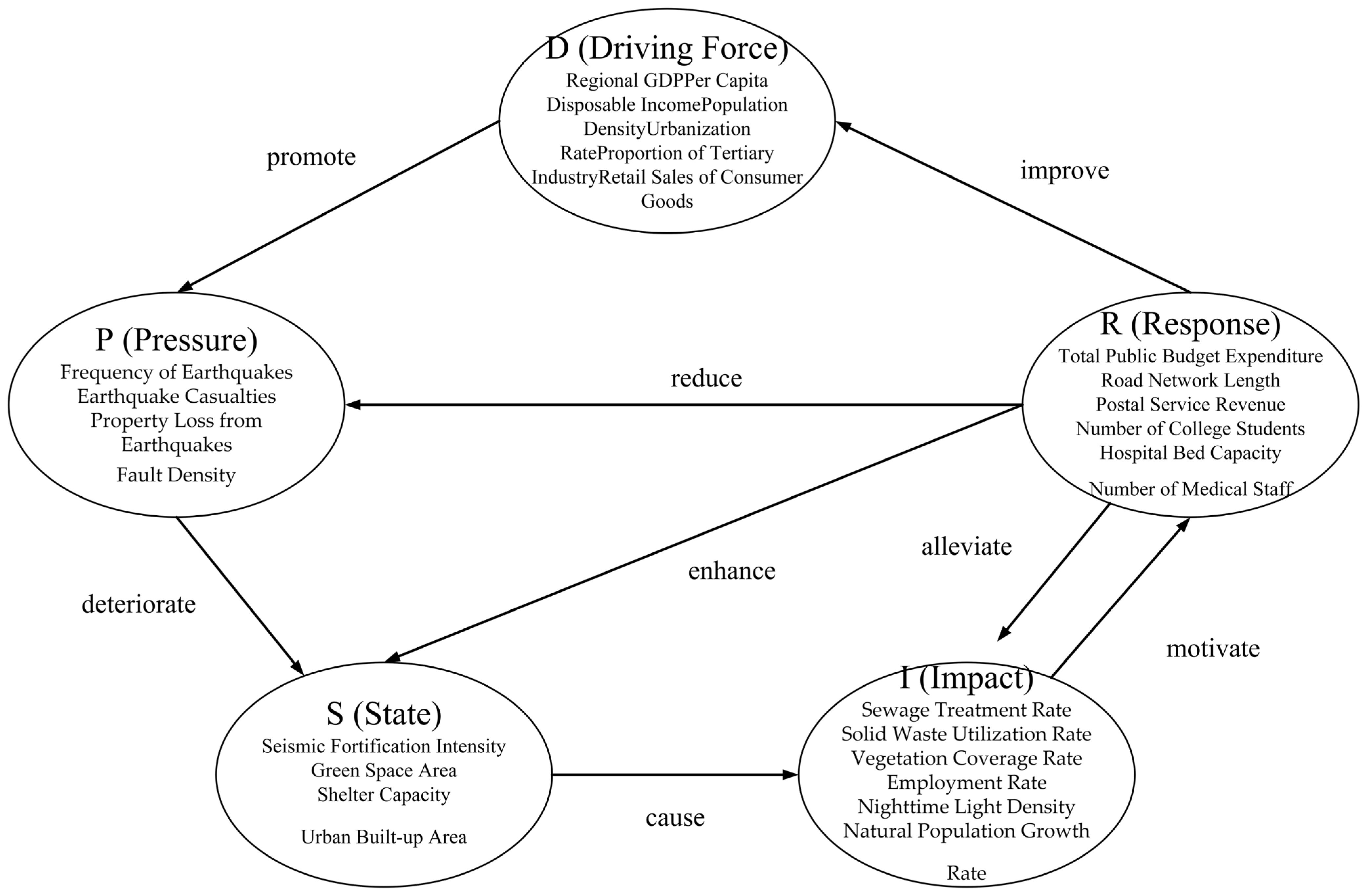

2.2.1. Theoretical Framework of the DPSIR Model

2.2.2. Indicator Selection and Theoretical Basis

2.2.3. Research Methods

- Calculation of Urban Seismic Resilience

- Indicator Variability

- Indicator Conflict

- Information Quantity

- Indicator Weight Value:

- Resilience Spatial Correlation Analysis

- (1)

- The purpose of global spatial autocorrelation analysis is to evaluate from an overall perspective whether the distribution of spatial data shows significant spatial dependence or randomness. Spatial Autocorrelation Tools are a category of statistical methods used to quantitatively describe the interrelationships among spatial objects in geographic space. Among them, Moran’s I is the most commonly used global spatial autocorrelation measure.

- (2)

- Local Spatial Autocorrelation: Local spatial autocorrelation aims to reveal the similarity between a spatial unit and its neighbouring units. The local Moran’s I is commonly used, and the formula is as follows.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Urban Seismic Resilience in S–Y Region

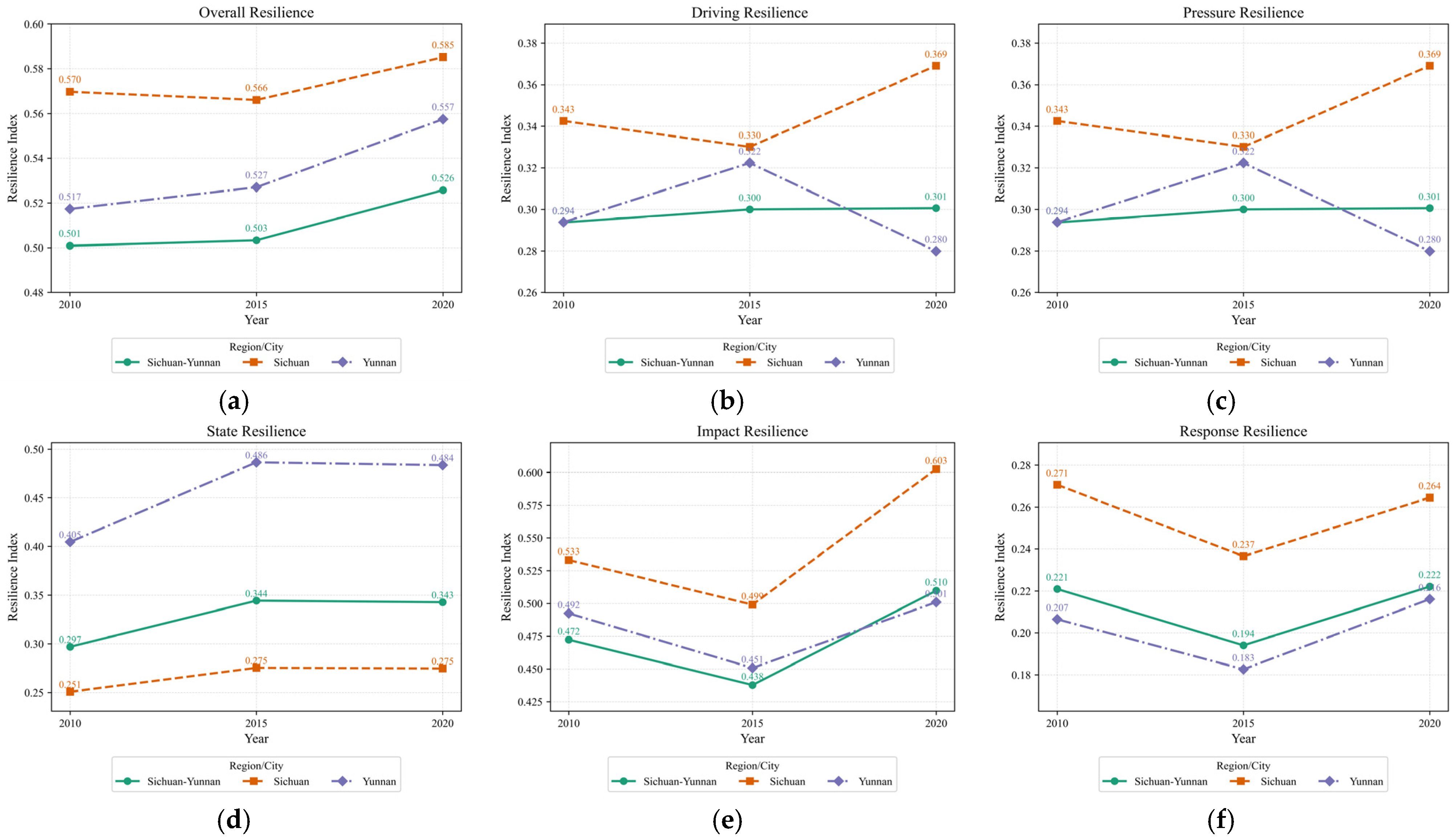

3.1.1. Analysis of the Time-Series Evolution Characteristics of Urban Seismic Resilience

3.1.2. Regional Evolution of Overall Urban Resilience

3.1.3. Regional Evolution of Seismic Resilience Subsystems

3.2. Spatial Correlation Analysis of Urban Seismic Resilience in S–Y Region

3.2.1. Global Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

3.2.2. Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance and Current Situation of Urban Seismic Resilience in the S–Y Region

4.2. Temporal Evolution Characteristics of Urban Seismic Resilience in the S–Y Region

4.3. Analysis of Urban Seismic Resilience Subsystems in the S–Y Region

4.4. Applicability of the Proposed Methodological Framework to Global Earthquake-Prone Regions

4.4.1. Universality of the Core Methodological Framework

4.4.2. Targeted Methodological Adaptations for Regional Specificity

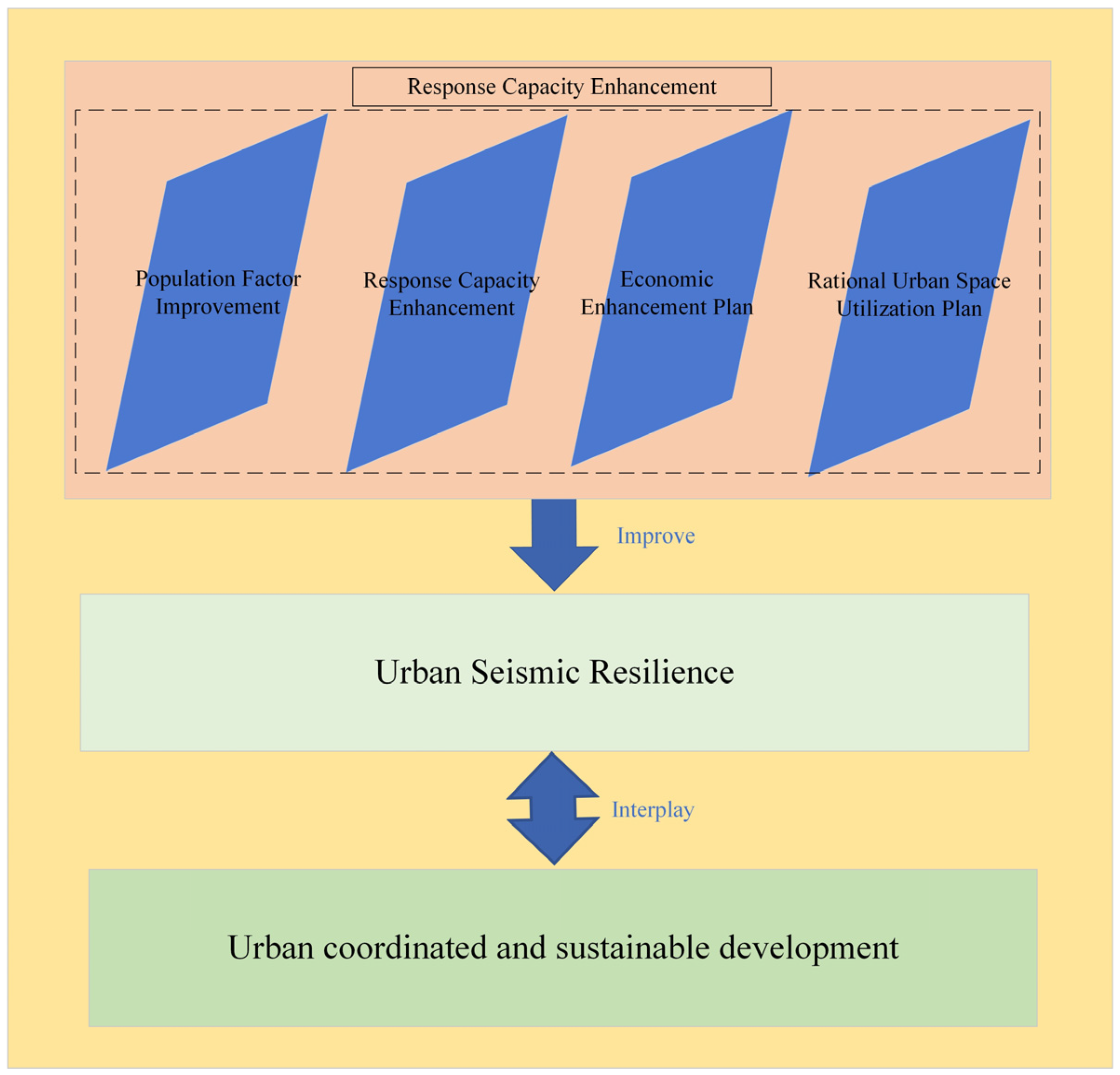

4.5. Strategies for Enhancing Urban Seismic Resilience in the S–Y Region

- (1)

- The enhancement of population factors is a key priority. It is imperative to optimise the internal structure of urban agglomerations and the industrial structure. It is imperative that big cities develop modern service industries in order to facilitate the transfer of the employed population. Similarly, medium and small cities should concentrate on the development of the manufacturing industry with a view to attracting the floating population to find employment in the immediate vicinity. Meanwhile, small towns should encourage the establishment of characteristic industries and increase policy support. It is imperative to establish a rational industrial distribution strategy to mitigate the escalating urban pressures precipitated by unregulated population mobility.

- (2)

- Enhancement of responsibility. It is imperative that measures are taken in the following areas: education, medical care, transportation, and budget expenditure. In the field of education, it is recommended that universities in Sichuan and Yunnan incorporate relevant courses into their curriculum, organise practical activities, and establish internship bases. In the field of medical care, the following measures are recommended: firstly, an increase in the number of doctors and hospital beds is to be effected; secondly, hospitals are to be built or expanded; thirdly, emergency plans are to be formulated; and fourthly, resource integration is to be strengthened. In the domain of transportation, it is imperative to optimise the planning process, augment investment, reinforce and renovate existing road infrastructure, and establish emergency channels as a contingency. In the context of budget expenditure, the establishment of special funds is imperative. These funds must be allocated and supervised with a reasonable degree of oversight, and the involvement of social capital is to be encouraged.

- (3)

- Economic improvement plan: It is recommended that the government consider ways in which it can increase its financial investment, establish special funds, and raise funds through multiple channels. The development of characteristic industries, the strengthening of regional cooperation, the encouragement of enterprises to participate, the optimisation of financial services, the improvement of the quality of the labour force, and the increase in investment in scientific and technological research and development are all recommended.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The present study is based on the DPSIR model. An urban seismic resilience evaluation system for the Sichuan–Yunnan (S–Y) region was constructed, and indicator weights were determined using the combined weighting method of CRITIC and AHP (e.g., the weight of the Pressure criterion layer is 0.36, and that of the Response criterion layer is 0.24). The findings indicate that between 2010 and 2020, the overall regional seismic resilience index increased from 0.501 to 0.526. Sichuan’s overall resilience exhibited a “decline first, then rise” trend (0.570 → 0.566 → 0.585), while Yunnan’s demonstrated continuous growth (0.517 → 0.557), which is consistent with the direction of national relevant strategies.

- (2)

- The spatial distribution of resilience exhibits dynamic heterogeneity: in 2010, the pattern was “low in the west and high in the central and eastern regions”, and it shifted to “high in the south and low in the north” by 2020, with cities with relatively high resilience accounting for over 51%. Chengdu and Kunming have traditionally exhibited dual core characteristics, demonstrating high levels of resilience that extend to surrounding regions. However, high-altitude mountainous areas in western Sichuan and mid-altitude mountainous areas in western Yunnan exhibited low resilience, a phenomenon attributable to the presence of concentrated fault zones and pervasive economic backwardness. The satellite cities around Chengdu (e.g., Suining) exhibited medium resilience, attributable to the superposition of limited urban space and seismic pressure.

- (3)

- The five subsystems demonstrate distinct evolutionary characteristics. With regard to Driving Force resilience, Sichuan exhibited a “decline first, then rise” trend (0.343 → 0.369), while Yunnan exhibited a “rise first, then decline” trend (0.294 → 0.280). Pressure resilience followed a consistent trend with Driving Force resilience. With regard to State resilience, Yunnan exhibited a “rapid rise then stability” trend (0.405 → 0.484), and Sichuan exhibited “steady growth” (0.251 → 0.275). Impact resilience exhibited a “V-shaped” recovery (0.472 → 0.438 → 0.510), and Response resilience rebounded significantly after 2015.

- (4)

- Spatial correlation demonstrated fluctuating characteristics: the global Moran’s I index indicated a weak negative correlation in 2010 (−0.051) and 2020 (−0.020), and shifted to a weak positive correlation in 2015 (0.028). The process of local agglomeration was implemented in a phased manner. The H-H clusters emerged in southeastern Yunnan in 2015, the H-L clusters persisted around Chengdu, and the L-L clusters were newly added in Ya’an in 2020. These findings reflect the impact of economic gaps and terrain on the spatial distribution of resilience.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Yue, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Zou, B.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, K. Statistical Seismo-Ionospheric Precursors of M7.0+ Earthquakes in Circum-Pacific Seismic Belt by GPS TEC Measurements. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 61, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zang, Y.; Meng, L.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Ma, Y.; Xie, M. A Summary of Seismic Activities in and around China in 2021. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2022, 2, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, M. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Continental Dynamics: A Review on Terrain Tectonics, Collisional Orogenesis, and Processes and Mechanisms for the Rise of the Plateau. Geol. China 2006, 33, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Li, Z.; Yuan, D.; Wang, X.; Su, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, A.; Su, P. Characteristics of Co-Seismic Surface Rupture of the 2021 Maduo Mw 7.4 Earthquake and Its Tectonic Implications for Northern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, P.; Tapponnier, P. Cenozoic Tectonics of Asia: Effects of a Continental Collision. Science 1975, 189, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Gu, J.P.; Xiong, X.Y. A preliminary investigation of the limits and certain features of the North-South seismic zone of China. Chin. Geophys. 1976, 19, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.H.; An, M.J.; Long, C.X. Activity Characteristics of Primary Active Faults in Yunnan–Sichuan Area and Their Seismic Activity in the Past. China Earthq. Eng. J. 2014, 36, 320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Du, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, L.; Sun, D. Recent Movement Changes of Main Fault Zones in the S–Y Region and Their Relevance to Seismic Activity. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.Y.; Li, Y.; Hou, J.; Mi, H. Review on Earthquake Disaster Loss in Chinese Mainland in 2008. J. Catastrophology 2010, 25, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T.Y.; Zheng, Y. Review of Earthquake Damage Losses in Chinese Mainland in 2013. J. Nat. Hazards. 2015, 24, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.H.; Yue, Q.R.; Xie, L.L. Progress of Research on Urban Seismic Resilience Evaluation. J. Build. Struct. 2024, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, K.; Kilar, V.; Koren, D. Resilience Assessment of Complex Urban Systems to Natural Disasters: A New Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, B.; Machingura, F.; O’Keefe, P. Disaster Resilience Integrated Framework for Transformation (DRIFT): A New Approach to Theorizing and Operationalizing Resilience. World Dev. 2019, 123, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.F.; Tian, J.F.; Zhang, J. Urban Resilience Evaluation System and Optimization Strategy from the Perspective of Disaster Prevention. China Saf. Sci. J. 2019, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P. Resilient Cities and Urban Resilience Development Mechanisms. Renming Luntan·Xueshu Qianyan 2022, Z1, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B. Evaluating the Evolution Patterns of Provincial Economic Resilience in China. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 44, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, X.R.; Guan, M.S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.S. New Progress in Seismic Resilience Assessment of Urban Structures. World Earthq. Eng. 2024, 40, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, D.P.; Zhai, C.H.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, X.Z.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Zhao, M.; Wen, W.P. Key Scientific Issues in Urban Earthquake Resilience. Sci. Found. China 2019, 33, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, X.G. Seismic Resilience Evaluation of Northwest Cities Based on DSR-Gray Cloud Model. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2022, 42, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.G. Comprehensive Evaluation of Urban Seismic Toughness in Northwest China Based on DSR-Grey Cloud Model. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gong, H.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y. Seismic Resilience Assessment of Urban Interdependent Lifeline Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 218, 108164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, M.D.; Kurth, M.H.; Pumo, I.; Linkov, I. Recovery-Based Design of Buildings for Seismic Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 65, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Herseth, A.; Johnson, K.; Hortacsu, A. Functional Recovery of Lifeline Infrastructure System Services. In Proceedings of the 18th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Milan, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Ghasemi, M.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Ahmadi, M. Integrating Flood and Earthquake Resilience: A Framework for Assessing Urban Community Resilience Against Multiple Hazards. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2024, 5, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, F.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Ghodousi, M.; Choi, S.M. Spatial-Temporal Modeling of Urban Resilience and Risk to Earthquakes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, L.; Honiden, T.; Schumann, A. Indicators for Resilient Cities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parizi, S.M.; Taleai, M.; Sharifi, A. A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Analysis Framework to Evaluate Urban Physical Resilience Against Earthquakes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, W.W.C.; Gabbianelli, G.; Monteiro, R. Assessment of Multi-Criteria Evaluation Procedures for Identification of Optimal Seismic Retrofitting Strategies for Existing RC Buildings. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 5539–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, S.M.; Taleai, M.; Sharifi, A. A Spatial Evaluation Framework of Urban Physical Resilience Considering Different Phases of Disaster Risk Management. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 13041–13076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civera, M.; Aloschi, F.; Di Maio, G.M.; Fierro Carrasco, J.P.; Miano, A.; Chiaia, B.; Prota, A. Seismic Resilience of Urban Networks: Dataset for Infrastructure Visualization and Vulnerability Assessment. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.P. Predicting Economic Resilience: A Machine Learning Approach to Rural Development. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 121, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, E.; Weterings, R. Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview; Technical Report No. 25; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eldos, H.I.; Tahir, F.; Athira, U.N.; Mohamed, H.O.; Samuel, B.; Skariah, S.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Al-Ansari, T.; Sultan, A.A. Mapping Climate Change Interaction with Human Health through DPSIR Framework: Qatar Perspective. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afedor, D.; Amankwah, E.; Takase, M. Application of DPSIR Model to Ascertain Driving Forces and Their Impacts on the Volta Basin. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obubu, J.P.; Odong, R.; Alamerew, T.; Fetahi, T.; Mengistou, S. Application of DPSIR Model to Identify the Drivers and Impacts of Land Use and Land Cover Changes and Climate Change on Land, Water, and Livelihoods in the L. Kyoga Basin: Implications for Sustainable Management. Environ. Syst. Res. 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Mavrotas, G.; Papayannakis, L. Determining Objective Weights in Multiple Criteria Problems: The CRITIC Method. Comput. Oper. Res. 1995, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Malakar, S.; Goswami, S. Evaluating Seismic Risk by MCDM and Machine Learning for the Eastern Coast of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, W.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Soil Degassing from the Xianshuihe–Xiaojiang Fault System at the Eastern Boundary of the Chuan–Dian Rhombic Block, Southwest China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 635178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, F.; Weng, H.; Ampuero, J.P.; Shao, Z.; Wang, R.; Long, F.; Xiong, X. Physics-Based Assessment of Earthquake Potential on the Anninghe-Zemuhe Fault System in Southwestern China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.G.; Ji, L.Y.; Gong, Y.; Du, F.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z. Present-Day Activity of the Anninghe Fault and Zemuhe Fault, Southeastern Tibetan Plateau, Derived from Soil Gas CO2 Emissions and Locking Degree. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, H.; Jiang, D.; Lou, X. Electrical Structure of Southwestern Longmenshan Fault Zone: Insights into Seismogenic Structure of 2013 and 2022 Lushan Earthquakes. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.K. Earthquake Potential of the Sichuan-Yunnan Region, Western China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 107, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Huang, K. Vulnerability Assessment and Differentiated Regulation of Rural Settlement Systems in the Alpine Canyon Area of Western Sichuan Under Geological Hazard Coercion: Taking Maoxian County of Sichuan as an Example. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, L.; Xu, C.; Huang, Y. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Earthquake Distribution and Associated Losses in Chinese Mainland from 1949 to 2021. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.H.; Zheng, T.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, K.F.; Chen, Y.H.; He, R.L. Review of Earthquake Disaster Losses in Chinese Mainland in 2021 and 2022. Earthq. Res. China 2023, 39, 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 44060-2024; Rules for Classification and Coding of Geomorphological Types. State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China (SAMR) & Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2024.

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. 2024 Statistical Communique on National Economic and Social Development of Sichuan Province; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. 2024 Statistical Communique on National Economic and Social Development of Yunnan Province; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Ma, C.; Huang, P.; Guo, X. Ecological Vulnerability Assessment Based on AHP-PSR Method and Analysis of Its Single Parameter Sensitivity and Spatial Autocorrelation for Ecological Protection—A Case of Weifang City, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, C.; Ge, C.; Yang, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, X. Ecosystem Health Assessment Using PSR Model and Obstacle Factor Diagnosis for Haizhou Bay, China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 250, 107024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Dong, Y. Regional Seismic Risk and Resilience Assessment: Methodological Development, Applicability, and Future Research Needs—An Earthquake Engineering Perspective. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 233, 109104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, M.; Ghasemi, S.; Sediek, O.; Jeon, H.; van de Lindt, J.W.; Shields, M.; Hamideh, S.; Cutler, H. Multi-Disciplinary Seismic Resilience Modeling for Developing Mitigation Policies and Recovery Planning. Resilient Cities Struct. 2024, 3, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Urban Resilience Enabled with Asset and Disaster Risk Management Approaches and GIS-Based Decision Support Tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, W.; Qin, H.; Xie, L. A Novel Urban Seismic Resilience Assessment Method Considering the Weighting of Post-Earthquake Loss and Recovery Time. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 84, 103453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi, Z.; Dehkordi, M.R.; Amiri, G.G.; Seilany, A.; Eghbali, M. Investigating Resilience Indicators of Urban Areas Against Earthquakes (Case Study: Qom City). Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Juneghani, A.; Nooraie, H. Evaluation of the Physical-Functional Resilience of Isfahan City Center Using Spatial Statistics Methods and ELECTRE. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, D.; Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R. A Systematic Literary Review on Community Resilience Indicators: Adaptation and Application of the BRIC Method for Measuring Disasters Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Sichuan Statistical Yearbook 2011; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Sichuan Statistical Yearbook 2016; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Sichuan Statistical Yearbook 2021; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Yunnan Statistical Yearbook 2011; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Yunnan Statistical Yearbook 2016; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Yunnan Statistical Yearbook 2021; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, W.; Zhai, C. From Earthquake Resistance Structure to Earthquake Resilient City—Urban Seismic Resilience Assessment. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2025, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, H.; Kang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Gong, Y.; Ke, Y. Research on the Fire Resilience Assessment of Ancient Architectural Complexes Based on the AHP-CRITIC Method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, G.; Luo, K.; Zong, H. Measurement and Spatio–Temporal Pattern Evolution of Urban–Rural Integration Development in the Chengdu–Chongqing Economic Circle. Land 2024, 13, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Syabri, I.; Kho, Y. GeoDa: An Introduction to Spatial Data Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarenko, V.F.; Rodkin, M.V. Statistical Analysis of Natural Disasters and Related Losses; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin, M.V. Dependence of Losses from Natural Hazards on the Prosperity of Societies: A Brief Review. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 1, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Interpretations |

|---|---|

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values of the above scales |

| 1 | Factors and are equally important |

| 3 | Factor is slightly more important than |

| 5 | Factor is significantly more important than |

| 7 | Factor is strongly more important than |

| 9 | Factor is extremely more important than |

| Criterion Layer | Criterion Weight | Indicator Layer | CRITIC Weight | AHP Weight | Comprehensive Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | 0.14 | Regional GDP | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Per Capita Disposable Income | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | ||

| Population Density | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.30 | ||

| Urbanisation Rate | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.28 | ||

| Proportion of Tertiary Industry | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||

| Retail Sales of Consumer Goods | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.07 | ||

| Pressure | 0.36 | Frequency of Earthquakes (Past 5 Years) | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.33 |

| Earthquake Casualties (Past 5 Years) | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.33 | ||

| Property Loss from Earthquakes (Past 5 Years) | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.25 | ||

| Fault length per unit area | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.10 | ||

| State | 0.20 | Seismic Fortification Intensity | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.31 |

| Green Space Area | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.26 | ||

| Shelter Capacity | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.39 | ||

| Urban Built-up Area | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.00 | ||

| Impact | 0.06 | Sewage Treatment Rate | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Solid Waste Utilisation Rate | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||

| Vegetation Coverage Rate | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.20 | ||

| Employment Rate | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.13 | ||

| Nighttime Light Density | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.18 | ||

| Natural Population Growth Rate | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.33 | ||

| Response | 0.24 | Total Public Budget Expenditure | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| Road Network Length | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.26 | ||

| Postal Service Revenue | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| Number of College Students | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ||

| Hospital Bed Capacity | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.15 | ||

| Number of Medical Staff | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Pang, Y. Resilience Assessment and Evolution Characteristics of Urban Earthquakes in the Sichuan–Yunnan Region Based on the DPSIR Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310618

Li H, Liu H, Zhang Y, Dong J, Pang Y. Resilience Assessment and Evolution Characteristics of Urban Earthquakes in the Sichuan–Yunnan Region Based on the DPSIR Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310618

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Haijun, Hongtao Liu, Yaowen Zhang, Jiubo Dong, and Yixin Pang. 2025. "Resilience Assessment and Evolution Characteristics of Urban Earthquakes in the Sichuan–Yunnan Region Based on the DPSIR Model" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310618

APA StyleLi, H., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Dong, J., & Pang, Y. (2025). Resilience Assessment and Evolution Characteristics of Urban Earthquakes in the Sichuan–Yunnan Region Based on the DPSIR Model. Sustainability, 17(23), 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310618