Abstract

This study examines the role of internal auditing in urban development within the Egyptian public sector, emphasising its contribution to governance and accountability in state-led projects. The research introduces a state-centric participatory audit approach tailored for urban development governance, diverging from traditional corporate-focused models by integrating institutional alignment and public sector accountability mechanisms. Unlike existing participatory audit frameworks, this model emphasises cross-agency coordination and sustainability governance within the Egyptian public sector, addressing gaps in oversight and collaborative planning. Findings reveal that internal auditing serves as a critical mechanism for aligning institutional objectives, enhancing transparency, and fostering participatory governance in urban development initiatives. Furthermore, the study advances institutional alignment through enterprise resource planning (ERP)-enabled participatory auditing, offering a governance-oriented framework for sustainability oversight in the public sector. Practically, the findings provide actionable guidance for public sector managers on embedding sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) into audit processes and leveraging ERP systems for real-time monitoring and assurance reporting. From a policy perspective, the study informs regulatory reforms and governance strategies aimed at institutionalising accountability and participatory oversight in large-scale urban development projects. These insights offer practical implications for policymakers and practitioners seeking to strengthen accountability and sustainability in public sector development programs.

1. Introduction

Urban development in emerging economies presents unique governance challenges, particularly in the public sector. In Egypt, rapid urbanisation and ambitious national projects have exposed vulnerabilities in financial management and accountability []. These pressures necessitate robust internal auditing systems that align with sustainability goals. Recent evidence suggests that sustainability initiatives often entail cost implications that organisations strategically absorb rather than transferring to consumers, reflecting global trends in green business models []. Internal auditing plays a critical role in enhancing transparency, accountability, and governance within the public sector, particularly in the context of urban development. It enables systematic evaluations of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), focusing on operational efficiency, financial management, and regulatory compliance. By providing objective assessments of how public resources are managed to achieve sustainability goals [], internal auditing strengthens institutional integrity and fosters public trust.

This study adopts a state-centric perspective, focusing on public sector governance rather than corporate sustainability frameworks, to examine how internal auditing contributes to institutional alignment and participatory sustainability in urban development initiatives. By analysing the Egyptian public sector as a case study, the research explores the mechanisms through which internal auditing supports strategic objectives, mitigates risks, and enhances stakeholder confidence in large-scale development programs.

While sustainability auditing in the public sector and SOEs has received growing scholarly attention, limited research has examined how national urban development pressures influence the evolution of internal auditing systems, particularly within centralised governance contexts. Parker et al. [] highlight the challenges of aligning institutional logics in public sector sustainability audits, while Mattei et al. [] call for deeper inquiry into the integration of sustainability practices between central governments and their enterprises. Grossi et al. [] emphasise both the opportunities and complexities of digitalising sustainability auditing, advocating for more empirical case studies in this emerging field. The role of ERP technologies in enabling participatory auditing also remains underexplored. For example, Pande [] investigates community-based monitoring in India, Aziliya and Sampurna [] examine citizen engagement in Indonesia, and the World Bank [] documents participatory audit initiatives in the Philippines and South Korea, all underscoring the potential of civic involvement in enhancing public accountability. These gaps point to a clear need for theoretically grounded, empirical research that explores how internal auditing systems can be effectively designed and implemented in response to national urban development pressures.

This study investigates how Egypt’s public sector has responded to national urban development pressures by implementing a participatory sustainability-oriented internal auditing system. It focuses on the mechanisms through which such systems are adopted and operationalised, particularly in the context of digital transformation. The central research question guiding this inquiry is: How is an internal auditing system implemented in response to national urban development pressures? To address this, the study explores two interrelated subquestions: First, how do national urban development projects generate pressures that influence the adoption of participatory sustainability auditing systems? Second, how are these systems operationalised through advanced ERP technologies and participatory audit committees? As explained below, Egypt offers a compelling case due to its centralised governance structure, recent regulatory reforms mandating sustainability KPIs, and the integration of ERP systems across public sector entities []. These developments provide a unique opportunity to explore how institutional logics, economic and social, are reconciled through digital infrastructure and collaborative audit mechanisms. ERP systems have emerged as transformative tools in public sector governance, enhancing transparency, accountability, and operational efficiency through centralised data management and automated workflows. Recent studies [,] show that ERP implementations can reduce manual processing time by up to 37% and improve data accessibility by 42%, directly contributing to improved auditability and sustainability reporting.

Grounded in principles of social accountability and participatory governance, this study introduces a novel internal auditing model tailored to the context of urban development. Unlike traditional top-down approaches, this model promotes active involvement of SOEs in decision-making, aligning audit functions with sustainable development goals. While conceptually related to participatory models such as social audits, citizen audits, and community-based monitoring [,,], the approach developed here differs in its institutional focus and operational design. Existing models typically emphasise citizen engagement to promote transparency and equitable service delivery, examples include the Citizen Participatory Audit in the Philippines, South Korea’s participatory audit system, and Indonesia’s adaptations, often supported by organisations like the World Bank and ACIJ. In contrast, this study’s model centres on inter-organisational collaboration within the public sector, particularly between central government entities and SOEs. It is shaped by national urban development imperatives and institutional dynamics, and is operationalised through ERP technologies and participatory audit committees composed of experienced internal auditors. These committees foster collaborative governance, enable data-driven decision-making, and help overcome resistance to change. By embedding sustainability objectives into the audit process, this model advances a transformative approach, moving beyond citizen oversight toward institutional co-creation and strategic alignment.

This study extends Besharov and Smith’s [] institutional theory framework to the domain of internal auditing in urban development, addressing a notable gap in the literature. While institutional theory has been widely applied in public sector auditing, particularly in relation to legitimacy, conformity, and organisational change, its use in examining the pressures arising from national urban development remains limited. Egypt’s urban development initiatives present a compelling empirical context, introducing competing demands that divide public sector institutional logic into two interrelated rationalities: a social logic, driven by the government’s commitment to citizen welfare, and an economic logic, increasingly adopted by SOEs in response to fiscal constraints and the shift toward partial self-financing. Besharov and Smith’s [] framework is particularly relevant here, as it focuses on institutional alignment—the coexistence and interaction of multiple logics within a single organisational field. Unlike models such as Meyer and Rowan’s [] institutional isomorphism or DiMaggio and Powell’s [] theory of institutional change, which emphasise conformity and homogenisation, Besharov and Smith [] offer a dynamic lens for understanding how organisations manage tensions between divergent logics. The economic rationality observed in sustainability practices, where firms balance cost absorption with efficiency gains [], aligns with institutional logics theory’s emphasis on competing priorities within organisational fields. This study applies their framework to explore how participatory sustainability auditing systems, enabled by ERP technologies and collaborative audit committees, can align the social logic of public sector governance with the economic logic of SOEs. In doing so, it contributes to a deeper understanding of how internal auditing practices evolve to support both sustainability and governance objectives in urban development.

Grounded in institutional theory, specifically Besharov and Smith’s [] framework on competing logics, this study employs an extended case study approach to examine how economic and social logics are reconciled through digital infrastructure and collaborative audit mechanisms. Unlike conventional case studies that offer static, single-organisation snapshots, Burawoy’s [] extended case method enables a dynamic, longitudinal analysis across interconnected entities. This approach is particularly suited to capturing the evolving institutional dynamics within Egypt’s public sector, where governance reforms and urban development pressures intersect. The empirical focus is on the relationship between Egypt’s central government, represented by the public sector ministry, and an SOE (anonymised as EYD for confidentiality), within the context of a participatory sustainability auditing system. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, focus groups, direct observations, and extensive document analysis involving both entities. This multi-source, multi-actor methodology allowed for a nuanced exploration of how ERP technologies and audit committees have facilitated a shift toward participatory governance and institutional alignment over time.

This study contributes to the growing literature on internal auditing in the public sector by offering both theoretical and empirical insights within the underexplored context of Egypt’s national urban development. Drawing on institutional theory, specifically Besharov and Smith’s framework [], the findings reveal how a participatory sustainability auditing system has transformed internal audit practices. Unlike traditional models centered on central government oversight, this emerging system integrates SOEs into a collaborative framework, expanding the scope of auditing to include sustainability performance, disclosure, and assurance. The Egyptian case presents a distinctive institutional configuration. While the public sector ministry emphasises social sustainability goals, such as equity, justice, and service delivery, SOEs like EYD increasingly adopt an economic logic, driven by fiscal constraints and partial self-financing policies for urban development projects. Although such divergence could lead to institutional conflict, the study identifies a novel form of operational alignment, facilitated by two key mechanisms: the deployment of ERP technologies and the establishment of participatory audit committees. ERP systems have played a central role in institutionalising the new auditing model, enabling real-time data sharing, remote collaboration, and integrated monitoring of sustainability KPIs across entities. In this context, ERP functions not only as a technological tool but as a governance enabler. Equally important are participatory audit committees, composed of senior auditors from both the ministry and SOEs, which have been instrumental in implementing the system and managing resistance during its early stages. Their collaborative efforts mark a shift from hierarchical oversight to inter-organisational partnership. Theoretically, the study extends Besharov and Smith’s concept of institutional alignment [] by introducing two novel dimensions: the enabling role of ERP technologies in sustaining cross-boundary alignment, and the strategic function of participatory audit committees in navigating institutional tensions. These insights offer a dynamic, practice-oriented understanding of how multiple institutional logics can coexist and be aligned in complex public sector environments. In contrast to prior studies that focus on single logics or conventional audit mechanisms [,,,,], this research demonstrates how participatory, ERP-enabled auditing systems can integrate diverse logics to enhance governance and sustainability in urban development. Ultimately, the study offers a replicable model for other countries facing similar governance challenges, highlighting the potential of collaborative, digitally enabled auditing systems to drive institutional alignment and sustainable outcomes.

This paper is structured into seven sections. Following the introduction, Section 2 critically reviews the literature on public sector internal auditing and presents the rationale for adopting Besharov and Smith’s [] framework on competing institutional logics. Section 3 contextualises the study within Egypt’s national urban development landscape. Section 4 outlines the research methodology, detailing the extended case study design and data collection methods. Section 5 presents the empirical findings, organised around the two subquestions derived from the central research question and interpreted through the lens of institutional alignment. Section 6 discusses these findings in relation to the theoretical framework and existing literature. Finally, Section 7 concludes by summarising key insights, identifying implications for policy and practice, and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Internal Auditing in the Public Sector

The evolution of public sector internal auditing has been shaped by successive waves of reform, transitioning from traditional public administration to New Public Management (NPM), and more recently, New Public Governance (NPG). Each paradigm introduced distinct institutional logics, ranging from compliance and performance to transparency and stakeholder engagement, that have significantly influenced audit design and practice. For instance, Guthrie and Parker [] show how performance auditing in Australia has shifted from rigid compliance models to more consultative, stakeholder-oriented approaches, reflecting NPG’s influence. Auditors increasingly engage with parliamentarians, the media, and auditees, using collaborative strategies to navigate conflicting logics and enhance audit effectiveness. Similarly, Mattei et al. [] trace the evolution of public sector auditing over four decades, highlighting a clear progression from bureaucratic control under traditional administration, to performance-driven auditing under NPM, and finally to participatory, value-oriented models under NPG. Their review underscores how changing public administration paradigms have reshaped both the purpose and practice of auditing. dos Santos and Gonçalves [] further illustrate this transformation at the European Court of Auditors, where audit methodologies have shifted from financial and compliance audits—aligned with bureaucratic logic—to performance and non-financial audits reflecting managerial and public value logics. These studies collectively demonstrate how evolving paradigms have introduced new institutional logics that continue to shape internal auditing systems, moving them beyond compliance toward more integrated, participatory, and sustainability-focused practices.

Institutional theory has long served as a key framework for interpreting the evolution of public sector auditing, particularly in understanding how audit practices are embedded within broader governance structures. It offers insight into how external pressures, such as regulatory mandates, professional norms, and societal expectations, shape internal audit functions. Studies have emphasised the role of institutional mechanisms, including audit committees, internal control systems, and performance frameworks, in promoting transparency and accountability. For example, Hay and Cordery [] argue that institutional arrangements such as audit committees and reporting structures are vital for democratic accountability, stressing the need to align audit practices with public expectations and institutional norms to enhance legitimacy and trust. Cordery and Hay [] further show that while audit institutions often adopt similar structures, their effectiveness is contingent on contextual factors such as political support, legal frameworks, and cultural norms, highlighting the importance of context-sensitive approaches beyond technical compliance. Despite its widespread use, institutional theory remains underdeveloped in parts of the literature. Nerantzidis et al. [], in a systematic review of 78 peer-reviewed articles, found that many studies lacked robust theoretical grounding and overlooked contextual influences such as institutional diversity, socio-political dynamics, and organisational culture. They call for more theoretically informed research that integrates institutional theory with empirical insights to better understand the evolution and operation of internal auditing systems. Collectively, these studies underscore both the strengths and limitations of current scholarship. While institutional theory provides a valuable foundation, there is a pressing need for more nuanced, contextually rich frameworks to explain the complex interplay of institutional logics, organisational structures, and governance outcomes, particularly in relation to sustainability and urban development.

Empirical research on public sector internal auditing has predominantly focused on performance audits shaped by NPM principles, with limited attention to how these systems address broader sustainability goals, particularly in urban development. Karim et al. [] demonstrate that firms engaging in green revenue generation typically absorb sustainability costs through operational efficiencies rather than passing them to consumers, reinforcing the economic logic shaping sustainability strategies. Performance audits, centred on efficiency, effectiveness, and economy, have become the dominant model under NPM, yet they often neglect the multidimensional nature of sustainability, which demands integrated frameworks encompassing environmental, social, and economic impacts, alongside participatory governance. Dittenhofer [] was among the first to advocate for expanding internal auditing beyond financial and compliance functions, proposing a strategic role for auditors in evaluating organisational performance. However, sustainability concerns remained peripheral in this approach. Similarly, Rana et al. [] examined the evolution of performance auditing and highlighted the influence of institutional pressures, such as regulatory mandates and professional norms, on audit practices. While acknowledging the rise of non-financial indicators, their study continued to frame auditing primarily in terms of operational efficiency, reinforcing critiques that current models are ill-equipped to address sustainability complexities. Moreover, existing literature often treats public sector entities and SOEs as isolated units, overlooking the inter-organisational coordination essential for large-scale urban development. These initiatives typically involve collaboration across ministries, municipalities, and SOEs, each governed by distinct institutional logics and accountability structures. Yet, few studies explore how internal auditing systems can facilitate alignment across these entities, an omission that is particularly problematic in contexts where SOEs must balance public value delivery with financial viability. In sum, while performance auditing has advanced operational oversight, it falls short in addressing systemic sustainability challenges. There is a clear need for more holistic, participatory, and inter-organisational auditing approaches that support sustainable urban development objectives.

Recent scholarship has increasingly explored participatory auditing as a means to enhance stakeholder engagement and promote transparency in public sector governance. Mattei et al. [], for example, examine mechanisms such as community scorecards and citizen oversight panels, showing how they empower local communities to hold institutions accountable, particularly in service delivery. Similarly, Aziliya and Sampurna [] highlight the role of digital platforms in enabling real-time citizen feedback, demonstrating how ICT tools can improve audit responsiveness and inclusivity. These approaches, ranging from citizen audits and public hearings to technology-driven feedback systems, align closely with NPG principles, which emphasise collaboration, transparency, and stakeholder involvement. The World Bank [] supports this view, documenting cases where citizen participation in audit processes has strengthened public trust and oversight, especially at the local government level. However, while promising, these models are largely citizen-centric and decentralised, often rooted in Western democratic or local governance frameworks. As such, they tend to overlook the institutional coordination required in more complex governance arrangements—particularly those involving central governments and SOEs in national urban development initiatives. These contexts demand a more integrated approach to participatory auditing, one that supports cross-sectoral collaboration and aligns with strategic national objectives, rather than relying solely on grassroots mechanisms.

While citizen-centric models have demonstrated success in decentralised governance systems, particularly in enhancing local accountability and civic participation, they may be less feasible in contexts like Egypt, where centralised authority, limited civil society engagement, and strong state oversight shape institutional dynamics. The country’s political structure prioritises strategic coordination and hierarchical control, making bottom-up audit mechanisms difficult to implement at scale [,]. Moreover, the absence of robust civic platforms and the limited institutional autonomy of local governments constrain the effectiveness of citizen-led audits [,]. In this environment, the state-centric, inter-organisational collaborative model observed in Egypt should not be viewed merely as an alternative, but as a contextually necessary and adaptive institutional innovation. It responds to structural constraints by leveraging existing state capacity and digital infrastructure to embed participatory principles within formal governance systems []. This reframing highlights the model’s strategic relevance and underscores its contribution to the broader debate on participatory auditing in complex governance settings.

A growing body of literature has begun to examine the institutional tensions inherent in participatory audit environments, particularly between auditors and stakeholders operating under competing logics. Parker et al. [] critically analyse how traditional audit institutions prioritise compliance and control, rooted in bureaucratic and regulatory frameworks, while stakeholders, especially citizens and civil society actors, advocate for participation, dialogue, and responsiveness. This divergence often generates friction, as auditors may resist participatory mechanisms that challenge their professional autonomy or introduce ambiguity into standardised procedures. Similarly, Kim [] explores these tensions in the context of public sector reforms, arguing that the logic of participation, centred on inclusivity and deliberation, frequently clashes with the compliance logic, which values efficiency, risk aversion, and hierarchical accountability. Kim’s [] findings highlight how these conflicting rationalities are rarely reconciled in practice, resulting in fragmented governance and limited effectiveness of participatory audit models. Despite their potential, existing frameworks often lack institutional mechanisms to align these divergent logics within complex governance structures involving multiple layers of government, SOEs, and private sector actors. This gap undermines the strategic value of participatory auditing in national development contexts. Moreover, the literature tends to overlook the transformative potential of digital technologies in bridging these divides. ERP systems and other integrated platforms can support data-driven decision-making, enhance transparency, and facilitate institutional integration across departments and agencies. These technologies offer a means to harmonise compliance and participation by enabling shared data environments, real-time monitoring, and collaborative interfaces that uphold audit rigour while fostering stakeholder engagement.

ERP systems are increasingly recognised as transformative in public sector governance, offering integrated platforms for financial management, performance monitoring, and compliance reporting []. Their ability to centralise data, automate workflows, and enhance transparency has made them pivotal in modernising internal audit functions. However, their role in enabling participatory sustainability auditing remains underexplored. Recent studies have begun linking ERP implementation to broader governance reforms, including civic engagement and collaborative oversight [,], suggesting that ERP systems can facilitate participatory governance through real-time data access, cross-organisational collaboration, and citizen-facing reporting tools. Building on this foundation, the present study examines how ERP infrastructure contributes to institutional alignment between central government entities and SOEs in Egypt. Specifically, it explores how ERP systems operationalise participatory sustainability auditing by mediating tensions between economic and social logics and supporting the integration of sustainability KPIs across organisational boundaries. This analysis responds to calls in the literature for more integrated and digitally enabled audit frameworks [,], and addresses critiques that traditional audit models remain narrowly focused on compliance and performance [,]. By embedding governance principles into daily operations, ERP systems in Egypt function not merely as technical tools but as institutional mechanisms that enable reflexive, inclusive, and data-driven auditing. This digital governance dimension offers a novel contribution to sustainability auditing literature, demonstrating how ERP technologies can support institutional change in complex public sector environments.

While prior studies have explored sustainability auditing within public sector organisations and SOEs, limited attention has been paid to how national urban development pressures shape the design and evolution of internal audit systems, particularly in centralised governance contexts. Much of the above literature focuses on general reform or isolated audit mechanisms, often overlooking the institutional complexity introduced by large-scale development agendas and fiscal constraints. This study addresses that gap by examining Egypt’s public sector response to urban development imperatives, offering a novel perspective on institutional alignment through ERP-enabled participatory auditing. By analysing how digital infrastructure and collaborative audit mechanisms reconcile competing institutional logics—economic and social—this research contributes new empirical insights and extends the theoretical application of institutional theory. In doing so, it builds on existing scholarship while offering a distinct contribution through its focus on a dynamic, multi-actor public sector setting shaped by national development priorities.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

To address the limitations identified in existing literature, particularly the absence of mechanisms for reconciling divergent institutional logics and the underestimation of structural complexity, this study adopts a conceptual framework grounded in institutional theory, focusing on the typology developed by Besharov and Smith []. Institutional theory provides a robust lens for examining how organisations respond to external pressures, normative expectations, and regulatory demands. It is especially relevant for analysing environments shaped by multiple institutional logics, defined by Thornton et al. [] as socially constructed sets of practices, values, and beliefs that guide organisational behaviour. In public sector auditing and governance, these logics often coexist, such as compliance and participation, originating from diverse stakeholders, regulatory bodies, or professional norms. Their interaction can generate tension, ambiguity, or, in some cases, foster innovation depending on how they are managed.

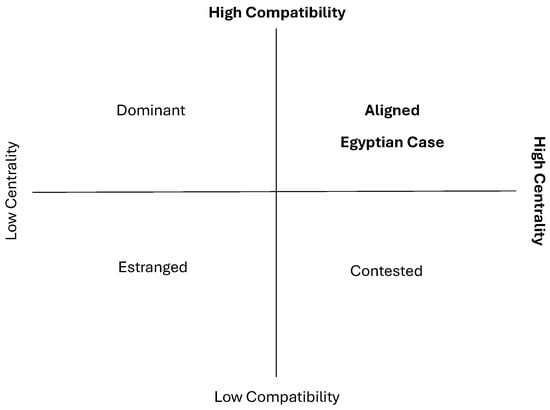

Besharov and Smith’s [] framework offers a structured approach to analysing this complexity by categorising organisations along two dimensions: centrality (the extent to which multiple logics are integral to core functions) and compatibility (the degree to which these logics can coexist without conflict). Based on these dimensions, organisations fall into four types:

- Contested: High centrality but low compatibility, where deeply embedded logics clash, creating persistent conflict and resistance to change.

- Estranged: Low centrality and low compatibility, where multiple logics are acknowledged but remain peripheral, resulting in superficial engagement and unresolved tensions.

- Dominant: Low centrality and high compatibility, where a single logic prevails and others pose minimal disruption, ensuring stability but limiting adaptability.

- Aligned: High centrality and high compatibility, where multiple logics are central and harmoniously integrated, enabling organisations to balance diverse expectations and navigate complex governance environments with minimal resistance.

Figure 1 illustrates Besharov and Smith’s [] framework, depicting the dimensions of centrality and compatibility and positioning the Egyptian case within the Aligned quadrant to highlight its relevance to this study.

Figure 1.

Institutional Logics Typology (Adapted from Besharov and Smith []).

As shown in Figure 1, Egypt’s public sector ministry and SOE configuration lies within the Aligned quadrant, reflecting high centrality and compatibility of institutional logics. This positioning demonstrates how social and economic priorities are harmonised through ERP-enabled participatory auditing and collaborative committees. These mechanisms embed governance principles into digital infrastructure, enabling real-time KPIs monitoring, cross-organisational coordination, and reflexive decision-making. As detailed in Section 5, empirical evidence confirms that these innovations sustain alignment and mitigate tensions between competing logics. This contrasts with contested configurations reported in prior studies [,], underscoring this study’s contribution in showing how ERP technologies and participatory structures institutionalise compatibility in complex, centralised governance contexts.

By applying Besharov and Smith’s [] framework, this study examines how public sector organisations, particularly those involved in national urban development and sustainability auditing, manage institutional complexity and foster collaborative governance. The framework offers a dynamic, context-sensitive lens for analysing multiple institutional logics, which is critical in environments where diverse actors, such as central governments, SOEs, civil society, and regulators, interact under competing expectations. Unlike earlier models, Besharov and Smith [] provide a more nuanced and operationalisable approach. For example, Meyer and Rowan’s [] emphasis on structural conformity explains legitimacy pressures but overlooks internal conflict and integration between logics. Similarly, Selznick’s [] focus on organisational responsiveness and value infusion offers insight into institutional evolution but lacks a systematic method for analysing the coexistence of multiple logics. These traditional models often assume stable or singular institutional environments, limiting their applicability in complex governance contexts characterised by plurality and contestation.

Besharov and Smith’s [] framework explicitly incorporates the dimensions of centrality and compatibility, enabling a typological classification of organisations based on how deeply multiple logics are embedded and how well they coexist. This approach aligns with the study’s research question, which examines how participatory sustainability auditing systems can reconcile competing logics, such as compliance, transparency, stakeholder engagement, and performance accountability, within public sector governance structures. The four organisational types (contested, estranged, dominant, and aligned) provide a practical tool for diagnosing institutional tensions and identifying pathways to integration. In participatory auditing, where collaboration among diverse actors is critical, alignment becomes particularly significant. It allows the study to explore how digital technologies (e.g., ERP systems) and participatory mechanisms (e.g., citizen audits, public hearings) can harmonise logics, reduce resistance, and strengthen institutional legitimacy.

Public sector auditing, particularly in sustainability and urban development, requires navigating multiple, often conflicting institutional logics. These include compliance and control (e.g., financial regulations, performance standards), transparency and accountability (e.g., public reporting, citizen engagement), participatory governance (e.g., stakeholder involvement, co-production), and strategic development (e.g., long-term planning, innovation). Traditional institutional theory models, such as Meyer and Rowan [] and DiMaggio and Powell [], emphasise legitimacy through conformity or institutional isomorphism, explaining why organisations adopt similar structures. However, they fail to address how organisations actively manage tensions between competing logics when these are central to operations. In contrast, Besharov and Smith’s [] framework is particularly suited to public sector auditing because it:

- Recognises the coexistence of multiple logics, enabling nuanced analysis of interactions among mandates, citizen expectations, and global sustainability pressures.

- Provides a typology—contested, estranged, dominant, aligned—for diagnosing organisational dynamics and identifying integration pathways, especially for SOEs balancing commercial and public service logics.

- Supports evaluation of participatory auditing systems, where alignment among diverse actors is critical for sustainability.

- Facilitates strategic audit design by linking centrality and compatibility to institutional coherence, allowing technologies like ERP systems to be assessed for their role in mediating logics.

- Aligns directly with this study’s research question, offering a conceptual tool to understand and manage institutional complexity in designing sustainability auditing systems.

Although institutional logics theory is increasingly applied in public sector research, the explicit use of Besharov and Smith’s [] framework in internal auditing, particularly within SOEs or participatory audit systems, remains rare, making this study a novel contribution. For instance, Grossi et al. [] examined the evolution of audit practices in the European Court of Auditors, identifying a shift from compliance-based logic to performance and public value logics. While not employing Besharov and Smith’s [] typology, their work underscores the relevance of multiple logics in public sector auditing and highlights institutional complexity as a key concern. Similarly, Parker et al. [] explored tensions between auditors and auditees operating under different logics, conceptually aligning with Besharov and Smith’s [] focus on compatibility and centrality, reinforcing the need for frameworks that address internal conflict and alignment. Maran and Lowe [] directly applied the centrality-compatibility typology to a hybrid public organisation delivering ICT services, demonstrating how alignment or contestation of logics shapes organisational outcomes. Although not focused on auditing, this provides methodological precedent for applying the framework in public sector governance contexts.

Based on the reviewed literature, there is limited evidence of the explicit application of Besharov and Smith’s [] framework within internal auditing in the public sector or SOEs. Existing applications predominantly focus on broader organisational contexts, such as hybrid organisations navigating competing logics (e.g., ICT service provision, social enterprises), institutional complexity in sectors like healthcare, education, and cultural industries, and corporate sustainability in developing economies. However, these studies rarely address internal auditing or public sector audit systems directly. One exception is a study that employed the framework to examine institutional pressures on performance management in a privatised Egyptian SOE [], suggesting some relevance to public sector reform and audit governance. Nonetheless, this remains an emerging area, with scant research applying the framework specifically to participatory sustainability auditing in public sector organisations.

This study represents one of the first applications of Besharov and Smith’s [] framework within the specific context of internal auditing in the public sector. Its use is both innovative and timely, offering a novel lens to examine how multiple institutional logics, such as compliance, participation, and strategic development, can be reconciled in complex governance settings. Unlike traditional institutional theory models that emphasise stability or conformity, Besharov and Smith’s [] framework provides a dynamic, context-sensitive approach well-suited to the multifaceted realities of sustainability-focused public sector auditing involving diverse stakeholders. As such, the framework offers a strategically appropriate and theoretically robust foundation for analysing how sustainability auditing systems can be designed to foster accountability, inclusivity, and long-term urban development.

3. The Egyptian Context

Egypt’s public sector has experienced substantial transformation over recent decades, driven by shifting governance paradigms and evolving national priorities. Historically, the country operated under a traditional public administration (TPA) model, marked by centralised control, rigid bureaucratic structures, and a strong emphasis on procedural compliance. Internal auditing during this period focused primarily on financial oversight and legal conformity, with institutions such as the Central Auditing Organization (CAO) playing a dominant role in monitoring public expenditure and enforcing regulatory adherence []. Auditing practices were largely reactive and hierarchical, with limited stakeholder engagement and minimal consideration of broader developmental outcomes. Despite modernisation efforts, Egypt’s internal audit systems have long suffered from constrained independence and a narrow compliance orientation, lacking integration with performance-based or participatory approaches []. These limitations have prompted calls for a fundamental shift in administrative methodology to support more effective and accountable governance.

The transition to NPM in the late 1990s and early 2000s marked a shift toward efficiency, performance, and managerial accountability. Driven by economic liberalisation, SOE privatisation, and pressure from international financial institutions, Egypt’s public sector began modernising its operations. Internal auditing practices evolved to include performance metrics, risk assessments, and strategic evaluations, particularly within SOEs engaged in infrastructure and service delivery. Auditors were increasingly expected to assess not only compliance but also programme effectiveness and value-for-money. However, despite introducing tools to enhance operational efficiency, NPM reforms often remained technocratic and top-down, with limited emphasis on public engagement or sustainability [,]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) governance reviews have acknowledged Egypt’s efforts to align with international standards, while also highlighting persistent challenges in coordination, transparency, and citizen-centred policy outcomes.

Over the past decade, Egypt’s governance landscape has evolved under the influence of NPG, which emphasises collaboration, transparency, and stakeholder participation. This shift has been driven by large-scale urban development initiatives, including the New Administrative Capital (NAC), the Urban Development Plan 2052, and the Western North Coast project. These efforts aim to address rapid urbanisation, economic growth, and spatial inequality, but also introduce complex governance arrangements involving central government agencies, private developers, and military institutions. In response, internal auditing practices have increasingly engaged with corporate sustainability frameworks, incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) indicators into audit processes []. Examples include metrics on energy efficiency, emissions reduction, social equity in service delivery, and governance transparency. To align with global standards, the Egyptian Financial Regulatory Authority (FRA) has mandated ESG reporting for SOEs and listed companies, requiring disclosure of sustainability metrics and climate-related financial data []. These developments reflect a growing institutional commitment to embedding sustainability within governance and audit systems.

A key development in Egypt’s governance reform is the gradual implementation of participatory sustainability auditing systems, particularly within SOEs engaged in urban development. These systems respond to growing national and international demands for transparency, accountability, and inclusive governance. Participatory auditing introduces mechanisms such as citizen feedback platforms, public hearings, and community-based monitoring, enabling stakeholders to engage with audit processes and influence decision-making. In Egypt, such approaches are increasingly relevant in projects where public resources, environmental impacts, and social outcomes intersect, such as housing, transportation, and land reclamation. The OECD has underscored the importance of participatory governance in achieving Egypt’s Vision 2030 goals [], recommending enhanced public consultation and results-based budgeting frameworks []. Additionally, Egypt’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) implementation strategy highlights integrated governance and stakeholder engagement as critical to advancing sustainable development and public sector accountability [].

Egypt’s public sector auditing presents a distinct institutional configuration, markedly different from both developed and other developing countries, making it a compelling case for investigation. Unlike decentralised systems in many Western democracies, where local governments appoint auditors and foster community-level oversight, Egypt’s model is centralised, with strong involvement from state institutions and the military in urban development governance. This centralisation shapes the design and implementation of internal auditing, particularly within SOEs, where the intersection of public service and commercial logics creates complex accountability challenges. In contrast, countries such as Australia, Germany, and Switzerland operate decentralised audit systems that promote diverse interpretations of financial accountability []. Similarly, Brazil and China exhibit varying degrees of independence and standardisation in local audit institutions, reflecting different political and administrative traditions. In other developing contexts, decentralisation has enabled more inclusive audit practices. For example, Ghana’s supreme audit institutions face political pressures that lead to strategic compromises in sustainability audits [], while Kenya’s citizen accountability framework formalises civil society engagement with the auditor-general []. Brazil’s regional audit bodies, though nationally mandated, lack standardised practices, resulting in fragmented oversight []. These comparative insights highlight how Egypt’s centralised and politically embedded audit structures, combined with its expansive urban development agenda, create a unique environment in which participatory sustainability auditing must navigate tensions between compliance, performance, and stakeholder engagement. This divergence from global norms underscores the need for context-specific frameworks, such as the one adopted in this study, to understand how institutional logics interact and to identify pathways for more inclusive and effective governance.

4. Research Methodology

This study employs Burawoy’s [] extended case study approach to examine ERP-enabled processes within a participatory internal auditing committee formed between a public sector ministry and its affiliated SOE (EYD). Over a three-year period, the research involved 20 semi-structured interviews and 22 focus groups with committee members from both entities, selected for their direct involvement in the newly implemented auditing system. Operating under the supervision of the minister and deputy minister, the committee maintains independence in line with the Institute of Internal Auditors’ [] definition, which emphasises the absence of conditions compromising objectivity. Monthly meetings with ministerial leadership and dual-reporting structures, comprising ERP-generated sustainability performance reports, reinforce transparency, accountability, and institutional integrity. The committee’s diverse composition fosters collaborative governance and participatory decision-making, enabling members to jointly define audit protocols and manage daily ERP operations.

The ERP system plays a central role in promoting transparency and accountability, thereby reducing opportunities for corruption. As a centralised platform, it records and monitors all auditing activities and sustainability KPIs, ensuring traceability and minimising data manipulation risks. Operated jointly by the ministry and EYD, the participatory internal auditing system fosters collaboration and inclusivity, enabling the identification and resolution of discrepancies and reducing biased reporting. Monthly sustainability performance reports are submitted to the ministry and published online, enhancing public scrutiny and serving as a deterrent to unethical practices. The involvement of external stakeholders, including military institutions, further strengthens the legitimacy and oversight of the audit process. Collectively, the ERP infrastructure, collaborative audit structure, regular reporting, and public disclosure form an integrated framework that reinforces institutional integrity and supports transparent, accountable auditing practices.

Interviews and focus groups were conducted across three distinct phases: June-August 2020, September-October 2021, and August-September 2022. This multi-phase design was both strategic and responsive to constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing on Burawoy’s [] extended case study methodology, the timing of data collection was structured to capture the evolution of the participatory internal auditing system—particularly during its formative stages and periods of disruption. In 2020, the system was in its initial implementation via an advanced ERP platform; by 2021 and 2022, it had become fully embedded in the daily operations of the joint auditing committee between the ministry and EYD. The interviews and focus groups explored the collaborative development of this system within the broader context of sustainability KPIs assurance in Egypt’s public sector. This longitudinal approach aligns with Alawattage and Alsaid’s [] application of Burawoy’s [] ontological and epistemological principles to document historical accounting reforms and structural transformation, specifically within Egypt’s electricity sector. While the original research plan included multiple data collection phases to track staged implementation, adjustments were made to accommodate pandemic-related disruptions to auditing and sustainability reporting.

To enhance transparency and traceability of the longitudinal research design, Table 1 presents a stage-based summary of the participatory sustainability auditing system’s implementation. It outlines the time periods, key contextual events, data collection methods, and emergent themes across each phase. This table aligns with Burawoy’s [] extended case study methodology and supports the study’s reflexive and process-oriented approach. By linking empirical insights with institutional theory, particularly Besharov and Smith’s [] alignment typology, Table 1 enables readers to trace how institutional logics evolved and were reconciled through ERP-enabled participatory auditing.

Table 1.

Research phase summary.

To ensure methodological rigour, the study employed a purposive sampling strategy. It selected 16 committee members, eight from the ministry and eight from EYD, based on their direct involvement in the participatory auditing system and their roles in sustainability governance. The total of 20 interviews and 22 focus groups reflects a longitudinal design across three implementation phases, allowing for follow-up with key informants and iterative exploration of emerging themes. Triangulation was achieved through the integration of interviews, focus groups, participant observations, and documentary analysis, enabling cross-validation and enhancing the credibility of findings. Data coding was conducted manually in three iterative stages: open coding to identify institutional logics and governance mechanisms; axial coding to refine thematic categories; and selective coding to align empirical insights with the theoretical framework. This process was guided by Burawoy’s [] extended case method and supported by field notes, transcripts, and document reviews, ensuring a robust and context-sensitive analytical approach.

As detailed in Table 2a,b, the study focused on a participatory internal auditing committee comprising 16 members, eight from the ministry and eight from EYD, selected in consultation with the deputy minister and EYD’s board director. Selection criteria included professional experience, roles in sustainability auditing, involvement in urban development decision-making, and prior leadership positions. This ensured that participants possessed the expertise necessary to address the study’s objectives. During the initial data collection phase, all 16 members were interviewed. Ministry participants were coded M1-M8, including a deputy minister (M1), a military delegate (M2), an internal audit manager (M3), and five senior auditors (M4-M8). EYD participants were coded E1–E8, including a board director (E1), financial manager (E2), ERP manager (E3), internal audit manager (E4), and four senior auditors (E5–E8). Each participant was interviewed once, with two senior auditors from each organisation interviewed twice to capture additional insights. Interviews were recorded when permitted; otherwise, detailed notes were taken. While transcripts provide verbatim accounts, note-taking, endorsed by Burawoy [] and Alvesson [], remains a valid method for capturing key themes, particularly under confidentiality or feasibility constraints.

Table 2.

(a) Central government participants. (b) State-owned enterprise participants.

The committee included four auditors, two from the ministry and two from EYD, who also held senior leadership roles within their respective organisations. In addition to their auditing responsibilities, they served as the ministry’s sustainability reporting and risk managers, and EYD’s regulatory compliance and corporate governance managers. These dual roles raised concerns regarding objectivity and independence, as managerial duties could influence audit decisions. To mitigate these risks, several safeguards were implemented: clear separation of auditing and managerial responsibilities through defined job descriptions; segregation of duties to prevent individual control over entire audit processes; regular training on ethical standards and conflict-of-interest policies; oversight by an independent monitoring body; periodic auditor rotation to reduce familiarity bias; and transparent reporting with public disclosure to enable external scrutiny. Collectively, these measures ensured the integrity and effectiveness of the participatory internal auditing system despite the dual roles held by some committee members.

While the dual roles of auditors as both internal reviewers and senior managers raised valid concerns about independence and objectivity, fieldwork revealed that this overlap also facilitated several operational advantages. Interviewees noted that these individuals were able to bridge communication gaps between departments, accelerate ERP system integration, and align audit priorities with strategic planning. Their managerial authority enabled faster decision-making and improved coordination across entities. However, some participants expressed reservations about the concentration of power and the potential for bias in KPIs validation and reporting. A few auditors voiced discomfort with the perceived lack of separation between oversight and execution, suggesting that this arrangement could compromise audit neutrality in politically sensitive contexts. These mixed perceptions underscore the importance of reflexivity in evaluating governance innovations. While the dual-role structure enhanced collaboration and responsiveness, it also introduced risks that required careful mitigation through transparency, role segregation, and inclusive committee practices.

Individual interviews were conducted with highly qualified committee members, most of whom hold PhDs and have over a decade of experience in public sector internal auditing and sustainability. Participants included politicians, military officials, and senior public managers. Interviews, ranging from 30 min to two hours, were primarily conducted in Arabic, with English-translated transcripts shared for participant verification in accordance with Yin’s [] accuracy guidelines. Although a unified interview protocol was used (see Table 3), questions were tailored to each participant’s role and experience, consistent with Burawoy’s [] extended case study approach. To deepen insights into the effectiveness of the participatory auditing system and inter-organisational collaboration, focus groups were conducted during the second and third data collection phases. The second round included four focus groups with six ministry participants (M1–M6) and six with seven EYD participants (E1–E7); the third round comprised five focus groups with eight ministry participants (M1–M8) and seven with seven EYD participants (E2–E8).

Table 3.

Linking empirical insights with Besharov and Smith’s [] alignment typology.

To validate data from interviews and focus groups, the study incorporated participant observations and documentary analysis, following Alvesson’s [] recommendations for methodological triangulation. Eight structured observations were conducted, offering insights into the daily operations of the participatory sustainability auditing system (see Section 5). With formal consent from the deputy minister, two auditing and assurance meetings and daily ERP practices were observed. The meetings were formal and focused, while ERP sessions were dynamic and collaborative. Committee members from the ministry and EYD demonstrated efficiency, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to data integrity and sustainability goals. The presence of senior auditors and executives reinforced adherence to best practices. Observations revealed a well-coordinated, professional environment that supported continuous learning and improvement. These findings strengthened the reliability of interview and focus group data and underscored the effectiveness of the participatory auditing system in promoting transparency and accountability in urban development projects.

Several challenges emerged during the observation phase. Maintaining confidentiality while ensuring comprehensive data collection was a key concern, as recording was not permitted. Detailed note-taking became essential, though it occasionally limited the capture of nuanced interactions. The technical complexity of the ERP system also posed difficulties, requiring a strong understanding of its integrated functions across departments. Additionally, balancing the dual roles of auditors and senior managers raised concerns about maintaining audit objectivity. Despite these challenges, the committee demonstrated professionalism and collaboration in resolving conflicts. One notable instance involved a disagreement over resource allocation for a public healthcare sustainability project: a ministry auditor advocated prioritising underserved regions, while an EYD manager preferred a balanced distribution. The issue was resolved through open dialogue, data sharing, and collaborative analysis, resulting in a decision to allocate additional resources to underserved areas while maintaining support elsewhere. This outcome was documented and integrated into the ERP system to ensure transparency and accountability. Overall, the observations revealed a culture of respectful communication, shared responsibility, and strong commitment to sustainable urban development.

Documentary analysis was a key component of the research, complementing interviews, focus groups, and observations in line with Burawoy’s [] extended case study methodology. Reviewed documents included Egypt’s 2030 urban development strategy [], project-level sustainability KPIs, internal auditing protocols, ERP-enabled audit features, and the 2022/2023 urban development budget. These were sourced from official channels such as the ministry’s website, committee records, EYD’s on-site library, and quarterly sustainability bulletins. Analysis of KPIs assurance reports and inter-organisational decisions demonstrated the transparency and effectiveness of the participatory auditing system. Publicly issued reports covered governance frameworks, sustainability pricing, and cost-risk management, particularly during the COVID-19 crisis. As detailed in Section 5, these documents revealed the system’s influence on policy-making, including the prioritisation of underserved regions in healthcare, the introduction of cross-subsidisation pricing strategies, and the creation of financial reserves, public–private partnerships (PPPs), and smart bonds to mitigate economic risks. These examples underscore the critical role of participatory sustainability audits in shaping equitable and resilient urban development policies.

Data analysis was conducted manually in three iterative phases to ensure a nuanced understanding of insights from interviews, focus groups, observations, and documentary sources. Each phase aligned with the corresponding data collection period and the ongoing analytical writing process. In the first phase, transcripts and audio recordings were reviewed to extract empirical insights, revealing the coexistence of two institutional logics: the ministry’s social logic, focused on public welfare and equitable urban development, and EYD’s economic logic, centred on financial sustainability and operational efficiency. Their collaboration through the participatory auditing committee illustrated how these logics were integrated to support sustainable urban development, evident in joint decisions on resource allocation, real-time KPIs monitoring via ERP, and policy shifts prioritising underserved regions, adjusting service pricing, and implementing financial safeguards during the COVID-19 crisis. In the second phase, data were categorised and coded to develop a coherent analytical framework, focusing on the interaction between social and economic logics and their influence on audit system design and effectiveness. Patterns and themes were identified using Burawoy’s [] extended case study approach. The third phase involved synthesising empirical findings with the theoretical framework and situating them within broader literature on public sector auditing and sustainability. As detailed in Section 5, the analysis highlighted how the participatory auditing system enhanced transparency, accountability, and collaborative governance, and demonstrated the ERP platform’s role in enabling informed decision-making and integrating diverse institutional priorities. Overall, the analysis provided a holistic view of how participatory sustainability auditing, grounded in both social and economic logics, contributes to equitable and resilient urban development in Egypt.

5. Empirical Findings

Section 5 presents the empirical findings in two stages: first, descriptive results drawn from interviews, focus groups, observations, and documentary analysis; second, analytical interpretation informed by institutional theory. To operationalise the theoretical framework, this section explicitly distinguishes between external institutional pressures, such as regulatory mandates, financial constraints, and political-military directives, and the strategic responses enacted by organisational actors, including ERP system design, audit committee formation, and participatory governance mechanisms. This structure enables a clear mapping of empirical findings to the core concepts of institutional alignment, as defined by Besharov and Smith’s [] framework. The findings are interpreted through this lens to examine how competing institutional logics (social and economic) are reconciled within Egypt’s public sector auditing system.

5.1. Exogenous Institutional Drivers: National Urban Development Pressures Shaping Participatory Sustainability Auditing

National-level urban development pressures in Egypt have significantly shaped institutional responses, leading to the implementation of participatory sustainability auditing systems. These systems were designed to foster collaboration between public sector ministries and affiliated SOEs, such as EYD, to meet the demands of large-scale development initiatives. A key driver was the financial structure of these projects, with an estimated cost of EGP 294.2 billion, 50% funded by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 30% by the European Union (EU), and the remaining 20% requiring self-financing by the ministry and SOEs. This financial burden necessitated transparent auditing mechanisms to validate fund allocation and ensure compliance with sustainability KPIs. The ministry, operating under a social logic focused on public service delivery, faced pressure to maintain quality despite limited resources. In contrast, SOEs like EYD adopted an economic logic, prioritising financial returns to meet their funding obligations. As the deputy minister M1 explained,

EYD’s operational philosophy closely resembles that of private sector organisations, with strategic priorities oriented toward financial performance. EYD’s participation in national projects and its adoption of the participatory auditing framework were contingent on the inclusion of financial and economic dimensions within sustainability indicators.

These findings illustrate the coexistence of divergent institutional logics, social and economic, within Egypt’s public sector auditing landscape. From an institutional theory perspective, this tension reflects the challenge of aligning public welfare objectives with market-oriented imperatives. The negotiated inclusion of financial metrics within sustainability KPIs suggests a strategic compromise that enabled institutional alignment. Applying Besharov and Smith’s [] framework, this case exemplifies an “aligned” configuration, where both logics are central and sufficiently compatible to support collaborative governance. The participatory auditing system, supported by ERP infrastructure, functioned as a mediating mechanism that reconciled these logics, enabling SOEs to fulfil financial mandates while contributing to national sustainability goals. This alignment underscores the transformative potential of participatory audit structures in navigating complex governance environments.

The divergence in institutional logics, socially oriented compliance for the central government ministry and economically driven priorities for SOEs, initially generated resistance during the negotiation phase of implementing a participatory auditing framework. These tensions persisted for nearly a year and were resolved only after high-level interventions from political leadership and the military. A negotiated compromise granted SOEs, such as EYD, the autonomy to commercialise sustainability-related products and services at premium rates in affluent urban markets. This adjustment aligned their operational model with financial viability while preserving their role in national development. As noted by senior auditor M4,

This arrangement enabled a cross-subsidisation model, allowing identical sustainability services to be delivered at reduced costs in underserved regions. The model was strategically designed to promote social equity while maintaining operational efficiency.

These findings illustrate how institutional tensions arising from incompatible logics can be resolved through strategic negotiation and structural adaptation. From an institutional theory perspective, the compromise reflects a shift toward alignment, where divergent logics are made compatible through policy innovation and governance flexibility. Applying Besharov and Smith’s [] framework, this case demonstrates how high centrality and increasing compatibility between social and economic logics enabled the participatory auditing system to function as a bridging mechanism. The cross-subsidisation model exemplifies how financial imperatives can be reconciled with equity goals, reinforcing the system’s role in fostering inclusive urban development within a centralised governance context. These arrangements delivered tangible social benefits by ensuring affordable access to sustainability services in underserved regions, while PPPs accelerated infrastructure delivery and improved service quality. Public assurance reports generated through participatory auditing strengthened governance transparency and enhanced stakeholder trust.

Financial pressures also catalysed broader institutional collaboration. As noted by senior auditor E7, the need to meet self-financing requirements led to the formation of PPPs involving the ministry, SOEs, the military, and private sector actors. These partnerships marked a significant shift in Egypt’s urban development governance, representing the first formal integration of cooperative frameworks into national infrastructure planning. The participatory sustainability auditing system became central to this transformation, functioning as an inter-organisational mechanism for collecting, monitoring, and assuring project-level sustainability KPIs. Embedded within Egypt’s Urban Development Strategy 2030 [], the system enhanced transparency, accountability, and stakeholder engagement, while producing publicly accessible assurance reports that supported funding acquisition and project legitimacy. Senior auditor E8 further highlighted:

Participatory auditing facilitated financing partnerships that enabled landmark projects such as the New Cairo Wastewater Treatment Plant, the Suez Canal Container Terminal, and the Benban Solar Park. These initiatives demonstrated the capacity of participatory auditing and PPPs to leverage public and private sector strengths in delivering sustainable urban development outcomes.

These findings illustrate how financial constraints and governance reforms prompted a reconfiguration of institutional relationships. From an institutional theory perspective, the integration of PPPs and participatory auditing mechanisms reflects a strategic response to reconcile divergent logics, public accountability and financial sustainability, within a centralised governance context. Applying Besharov and Smith’s [] framework, this shift suggests movement toward an “aligned” organisational configuration, where multiple logics are both central and compatible. The participatory auditing system, supported by ERP infrastructure, served as a mediating mechanism that enabled coordination across institutional boundaries. The production of publicly accessible assurance reports further institutionalised transparency and legitimacy, reinforcing the system’s role in sustaining alignment between state-led development goals and market-based financing strategies.

Urban development in Egypt has not evolved through financial pragmatism alone; it has been strategically recalibrated under the assertive influence of political and military institutions, fundamentally reshaping governance structures and institutional practices. The political leadership, described by internal auditing manager M3 as having a “military spirit and mentality that prioritises discipline, centralised control, and strategic execution,” has actively directed collaborations with military bodies in the planning and execution of urban initiatives. These partnerships have extended beyond logistical coordination into governance reform, particularly through the mandated adoption of participatory sustainability auditing systems. Embedded within Egypt’s Urban Development Strategy 2030 [], these systems function as inter-organisational mechanisms for monitoring and assuring project-level sustainability KPIs. They enhance transparency, accountability, and stakeholder engagement, producing publicly accessible assurance reports that support project legitimacy and financing. During participatory auditing meetings, senior officials such as the deputy minister M1 and the EYD board director E1 acted as intermediaries, translating strategic directives from political-military leadership into operational frameworks. As senior auditor E7 observed:

The military’s involvement is not symbolic—it is operational. They provide equipment, mobilise public support through social campaigns, and engage directly with communities to ensure that urban development projects are not only executed efficiently but also reflect national sustainability priorities.

Military involvement has also enabled SOEs to reconcile economic objectives with social equity goals through strategic pricing and resource allocation. Military support facilitated the marketing of sustainable products and services in affluent areas at premium prices, allowing profits to be reinvested in subsidising services in disadvantaged regions. This model proved particularly effective in large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Benban Solar Park and the Suez Canal Container Terminal, where military-provided security, logistics, and infrastructure enhanced operational efficiency and reduced implementation risks. These partnerships not only improved service delivery but also legitimised the role of SOEs in advancing inclusive urban development. As military delegate M2 explained:

The participatory auditing system, supported by military coordination and political engagement, operates through an advanced ERP platform that enables decision-makers at all levels, local councils, regional authorities, and national ministries, to verify sustainability KPIs in real time. This system ensures that urban development is not only technically sound but also socially responsive and strategically aligned with Egypt’s long-term goals.

These findings underscore how financial constraints, political authority, and military involvement have jointly driven a strategic reconfiguration of institutional relationships in Egypt’s urban development governance. This transformation reflects a deliberate effort to reconcile competing institutional logics, namely, public accountability, financial sustainability, and centralised state control, within a hybrid governance framework. From an institutional theory perspective, the integration of participatory sustainability auditing and military collaboration represents a form of pragmatic hybridisation, wherein SOEs navigate multiple, potentially conflicting demands. The participatory auditing system, supported by ERP infrastructure and military coordination, operates as a boundary-spanning mechanism that facilitates inter-organisational alignment. It enables real-time verification of sustainability KPIs across local, regional, and national levels, thereby institutionalising transparency and responsiveness. Applying Besharov and Smith’s [] alignment typology, these developments suggest a shift toward an “aligned” configuration, where multiple logics, discipline-driven execution, market-based financing, and inclusive governance, are both central and compatible. The strategic use of military resources to subsidise services in disadvantaged areas through cross-subsidisation models further exemplifies this alignment, allowing SOEs to pursue economic viability while advancing social equity. The production of publicly accessible assurance reports and the active role of intermediaries such as the deputy minister M1 and the EYD board director E1 reinforce the legitimacy of these hybrid arrangements, embedding sustainability and inclusivity within the operational logic of urban development.

Regulatory reform has emerged not simply as a procedural necessity but as a strategic instrument for institutional transformation in Egypt’s public sector. The 2018 amendment to the public sector law, aligned with Egypt’s Urban Development Strategy 2030 [], introduced a legal mandate for SOEs to adopt participatory internal auditing systems, signalling a departure from traditional compliance models toward a performance-oriented, KPIs-driven approach to sustainability governance. In response, the public sector ministry and affiliated SOEs established a participatory auditing committee supported by integrated ERP systems, enabling real-time monitoring and reporting of sustainability performance. As noted by senior auditor and sustainability reporting manager M5:

The 2018 amendment was a turning point. It gave legal weight to sustainability KPIs and required SOEs to embed them into their operational and reporting structures… enabling informed decision-making and effective compliance monitoring aligned with national sustainability goals.

The regulatory framework codified a comprehensive set of sustainability KPIs, including emissions reduction, energy efficiency, renewable energy adoption, water management, waste diversion, and occupational health and safety, that now shape both operational and strategic priorities. These indicators function not as passive compliance metrics but as active levers of institutional accountability, influencing funding eligibility, project approval, and public legitimacy. As senior auditor and sustainable corporate governance manager E8, explained:

These KPIs have transformed how we operate… The participatory auditing system ensures that our reports are transparent and credible, which is essential for regulatory compliance and for building trust with stakeholders.

The regulatory embedding of participatory sustainability auditing reflects a deliberate effort to recalibrate institutional logics within Egypt’s public sector. Rather than merely enforcing compliance, the 2018 legal amendment redefined the role of regulation as a mechanism for strategic alignment, compelling SOEs to internalise sustainability as a core operational imperative. The integration of ERP-enabled auditing systems facilitated not only data transparency but also cross-sectoral coordination, reinforcing the state’s capacity to monitor and steer urban development outcomes. From an institutional theory perspective, this shift exemplifies how regulatory instruments can be mobilised to mediate tensions between competing logics, legal compliance, financial accountability, and sustainability performance, within a centralised governance structure. Applying Besharov and Smith’s [] alignment typology, the Egyptian case illustrates a movement toward an “aligned” configuration, where multiple logics are simultaneously central and mutually reinforcing. The participatory auditing committee operates as a boundary-spanning mechanism, enabling SOEs to reconcile strategic execution with normative expectations of transparency and equity. In doing so, it institutionalises sustainability not as an external demand but as an embedded organisational logic, legitimising SOEs’ role in delivering inclusive and accountable urban development.

In summary, national urban development in Egypt has been shaped by intersecting financial, political-military, and regulatory pressures that have collectively redefined the institutional context for participatory sustainability auditing. These forces have compelled the public sector ministry and affiliated SOEs to adopt collaborative auditing systems that not only comply with evolving governance standards but also strategically align with national sustainability objectives. The participatory auditing system has thus emerged as more than a reactive compliance tool—it functions as a mechanism for institutional reform, enhancing transparency, accountability, and strategic coherence. Building on these national-level drivers, the next subsection examines how such pressures are operationalised within organisations, focusing on the internal implementation of participatory sustainability auditing and its alignment with Egypt’s urban development priorities.

5.2. Endogenous Organisational Responses: Aligning Participatory Sustainability Auditing with National Urban Development Priorities