Abstract

This study focuses on biogas production within lab-scale semi-batch bioreactors using agro-industrial wastes and dry biomass of an invasive aquatic species. In particular, the primary objective is to increase the yield of anaerobic digestion processes, with a specific focus on reducing CO2 emissions associated with the degradation of biomass, by co-digesting different raw biomasses and agro-industrial wastes. In detail, the experiments concerned the pulp of Brewery’s Spent Grain (BSGp), consisting of the residual of Brewery’s Spent Grain after fiber deconstruction with ionic liquids–based treatment, and Lemna minor L. (LM). The two biomasses were studied separately and then co-digested. Co-digestion was carried out using a 1:1 (VS basis) mixture of Lemna minor and Brewery’s Spent Grain pulp. Due to the lack of organic nitrogen, BSGp showed low biogas production if compared with untreated BSG (1.14 × 10−3 vs. 1.71 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS). Differently, LM has a high nitrogen content and, when digested alone, produced 9.79 × 10−4 Nm3/gVS. The co-digestion tests allowed us to reach the highest performance: 2.94 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS. In terms of bioenergy production, the two biomasses showed high synergy when used in co-digestion. The amount of energy produced was calculated using a lower heating value (LHV) of CH4 equal to 52 MJ. The results showed that co-digestion yielded 64.9 ± 0.6 MJ/kgVS, followed by BSG (43.3 ± 5.3 MJ/kgVS), BSGp (25.6 ± 0.3 MJ/kgVS), and LM (19.3 ± 1.0 MJ/kgVS). In addition, in terms of CO2 avoided, the following results were achieved: 0.38–0.40 gCO2/gVS with BSGp, 0.73–0.8 gCO2/gVS with LM. Conversely, co-digestion tests allowed for the avoidance of 1.68–1.91 gCO2/gVS. In conclusion, co-digesting BSGp with Lemna minor yields more methane and less CO2 per unit processed, providing an effective way to convert readily available waste and biomass into bioenergy.

1. Introduction

Organic waste and biomass represent a significant environmental challenge due to their potential impact on the ecosystem and human health when not properly managed. The risks associated with improper disposal stem from the intrinsic characteristics of organic matter, which can rapidly decompose, leading to the release of greenhouse gases, the proliferation of pathogens, and leachate generation that may contaminate soil and water [1]. This type of waste primarily originates from household food residues, but also from food processing industries. While waste prevention strategies are essential, the complete elimination of organic waste is not feasible.

In this regard, anaerobic digestion (AD) represents a promising strategy for the sustainable management of organic biomass. AD can be more accurately described as a biochemical process driven by microorganisms that enables rapid biodegradation while producing renewable energy, supporting a circular economy model [2].

With the AD process, it is possible to recover CH4 and reduce the quantity of CO2 produced, compared to the CO2 emitted with an aerobic treatment [3,4,5,6]. Composting and landfilling result in the direct release of CO2 due to the aerobic biodegradation of organic matter [7]. By optimizing the initial feedstock composition and ensuring a balanced nutrient ratio, CO2 emissions can be minimized, and a portion of the CO2 can be recovered during the biogas upgrading processes [8].

To enhance the CH4 content in biogas production, Anaerobic Co-digestion (AcoD) represents an effective strategy to balance the nutrient composition of the initial feedstock [9]. Different matrices can lead to variable results in terms of biogas/biomethane production. However, it may occur that the AD process does not reach completion due to a lack of key nutrients, which can condition the activity of microbial communities. In particular, organic carbon and nitrogen are the most critical ingredients for AD: the former to ensure abundant energy for microorganisms and then to allow biogas production, while the latter is among the main nutrients for sustaining bacteria. To ensure high process efficiency, these two elements have to be properly balanced. If carbon is in excess, its conversion remains incomplete. Conversely, an excess of nitrogen would lead to low biogas production per mass unit of raw biomass The addition of co-substrates can enhance the overall AD process by improving nutrient balance, promoting the conversion of organic matter, and increasing process stability, ultimately leading to higher biogas yields and enhanced economic performance [10,11].

In a study by Akbay H. E. G. (2024) [12], AcoD was investigated to enhance biomethane production from okra waste, a medicinal plant belonging to the Malvaceae family, in combination with municipal sewage sludge. The results demonstrated that AcoD increased biogas yields by 66% and 112% compared to the mono-digestion of okra waste and municipal sewage sludge, respectively. In another study [13], researchers evaluated the AcoD of slaughterhouse wastewater and olive mill wastewater in a 50:50 ratio, obtaining the highest biogas and biomethane yields compared to the control. Other studies have evaluated the improvement in biomethane production achieved by co-digesting agricultural waste and animal manure, yielding positive results [14,15,16]. This approach is particularly relevant when dealing with residues from biorefinery processes, where biomass has already been utilized for the extraction of high-value-added compounds. In such cases, the biochemical characteristics of the residual biomass are altered, often resulting in depletion of key nutrients such as nitrogen and carbon [17]. For instance, pulp residues, cellulose-rich by-products of the agri-food industry, exhibit structural heterogeneity influenced by plant tissue type, age, and function [18]. Under anaerobic conditions, their degradation, mediated mainly by clostridial species, produces short-chain fatty acids such as acetate and propionate but proceeds slowly, typically requiring up to 50 days [19,20]. This slow conversion limits their suitability as sole substrates for AD. However, their co-digestion with nutrient-rich materials can enhance biogas yields and improve process efficiency.

This study aimed to evaluate the amount of CO2 emissions avoided through the anaerobic digestion of selected residues, compared to conventional aerobic treatment of agro-industrial biomass within a biorefinery context. Despite AD processes leading to the production of methane, the overall footprint is lower, since methane is used for energy valorization and allows for the reduction in the quantity of fossil fuel otherwise required [21]. Following the IPCC framework, CO2 quantifications can also be assessed through Life Cycle Assessment analyses [22,23]. In particular, the analysis focused on Brewery Spent Grain (BSG), a by-product of the brewing industry, BSG pulp (BSGp) obtained after lignin removal within a biorefinery process, and Lemna minor (LM), a common aquatic weed. LM was used as a co-substrate for enrichment due to its high nitrogen content [24], which helps compensate for the nitrogen deficiency typical of pulp-based biomass. Lemnaceae species have already been investigated for both biogas and bioethanol production [25]; however, the novelty introduced in this study lies in exploiting nitrogen-rich Lemna minor to optimize the C/N ratio of BSGp, thus improving the overall AD efficiency.

In this sense, the recent literature denotes a growing interest in testing aquatic species, such as Lemna minor, in anaerobic co-digestion processes [26,27,28,29]. In addition, this study aimed to assess the co-digestion of other biomass with Lemna minor, since previous research has shown that such co-digestion can enhance biogas yields [30,31].

2. Biorefinery Approach for Biomass Recovery

The biogas produced via AD processes mainly consists of 50–75% methane and 25–50% carbon dioxide [32,33,34]. The AD process depends on the activity of different typologies of microorganisms, working under oxygen-free conditions at different stages, which carry out hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis and methanogenesis processes [35]. Substrates rich in lignin require longer degradation times, while biomass rich in degradable compounds, as carbohydrates and proteins, allowing them to reach significant production in relatively short time periods [36]. Since the structure and morphology of the substrate are key parameters for AD, treatments aimed at preparing it for digestion are often necessary [37]. After treatments, substrates result in fiber deconstruction, lower particle size, and a higher tendency to be attacked by microorganisms [38,39].

Treatments used for improving the biogas/biomethane production yield are grouped into physical, chemical and biological ones. Physical treatments are carried out to decrease the particle size of biomass and also work on its crystallinity, thus lowering the polymerization degree and increasing the surface/area ratio [40,41,42,43]. Chemical treatments have the scope of disrupting the structure of biomass, increasing its biodegradability and reducing the hydraulic retention time [44,45,46,47]. Finally, biological treatments are based on the activity of microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. In combination with enzymes, these microorganisms are capable of breaking down the fiber components, without the additional use of chemical additives. Therefore, these elements represent the most viable option from an environmental point of view [48,49,50].

Following the biorefinery approach, agro-industrial residual and, more in general, biomass, are treated (before the AD process) also for different purposes, as extracting valuable components or producing high-value-added products.

For example, Ref. [51] investigated the extraction of sugars from cellulose using concentrated acid hydrolysis, aiming to avoid degradation of hemicellulose. They used pine wood, oak wood, and empty fruit bunches of palm oil as feedstocks, achieving sugar yields of 52.28%, 59.98%, and 61.36%, respectively. In the study by Tolisano and colleagues [52], nanostructured lignin was obtained from olive pomace through the ionic liquid method to treat the biomass and tested as a biostimulant on maize plants. The results demonstrated a positive effect on plant growth and various biochemical traits.

However, since those treatments are not finalized for improving the biogas/biomethane production yield, their effect on the AD process needs to be carefully checked in order to ensure their viability. Modifications to the biomass resulting from the extraction of certain components can also negatively impact its biogas potential. For instance, lignin removal from BSG using the ionic liquid method significantly reduced biogas production compared to the raw biomass. This reduction was attributed to a decrease in nitrogen content, leading to nutrient limitations for anaerobic digestion microorganisms [18].

If treatments reduce the AD efficiency, two options are available: (i) directly proceed with the AD process, without valorizing the compounds contained within biomass, or (ii) approach the residual biomass in co-digestion with other matrices, capable of adding the components removed with treatments, thus making the process efficiency equal or, if possible, higher, than the one corresponding to the untreated biomass. For instance, BSG has been investigated within a biorefinery approach. Nanostructured lignin was extracted using the ionic liquid method, while protein hydrolysates were obtained through alkaline hydrolysis. In both cases, the residual biomass after extraction showed a reduced biogas yield compared to untreated BSG [18].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Tested Biomass and Characterization

BSG used in this study was kindly provided by the local brewing company “La Gramigna” (Perugia, PG, Italy). The chemical composition of the raw BSG is reported in Table 1. The BSG was subsequently treated with an ionic liquid, [Et3NH][HSO4], to remove lignin and hemicellulose [53,54]. Following this treatment, the resulting solid residue, mainly composed of cellulose and referred to as BSG pulp (BSGp), was collected and characterized, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of the biomass used in the study.

Lemna minor was cultivated at the Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences of the University of Perugia. After harvesting, the biomass was dried at 50 °C in an oven (Nüve EN500, Nüve, Ankara, Turkey) for 48 h and ground into a fine powder. Its characterization is also presented in Table 1.

To characterize the biomass, the following analytical methods were applied. Sample humidity and volatile solids (VS) were determined based on a standard protocol with minor modifications [55,56]. Briefly, 2 g of each biomass sample were dried in an oven (TCN 50 Plus, Argolab, Modena, Italy) at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. Moisture content was then calculated as the difference between the initial wet weight and the dry weight and expressed as a percentage. Each analysis was performed in triplicate. For vs. determination, 2 g of the previously dried biomass were weighed in ceramic crucibles (in triplicate) and incinerated in a muffle furnace (FM13, Falc, Bergamo, Italy), gradually heated to 550 °C and maintained at that temperature for 24 h. Crucibles were then cooled in a desiccator containing silica gel before final weighing. VS content was calculated as the difference between the pre- and post-incineration weights.

The pH was measured according to the method described in [57] (Carter and Gregorich, 2007), using a 1:2.5 (w/v) water extraction and a glass electrode (60 VioLab, XS, Modena, Italy). Water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and water-extractable nitrogen (WEN) were analyzed using a total organic carbon/total nitrogen TOC/TN analyzer (multi N/C 2100, Analytik Jena GmbH, Überlingen, Germany) and C/N was computed as TOC/TN. Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin contents of the BSG, BSGp and Lemna minor were determined according to Van Soest (1963) [58].

3.2. Biomethane Production and Anaerobic Digestion Bioreactors

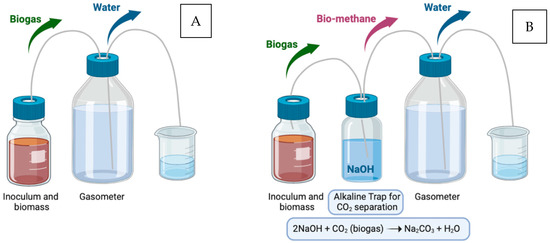

The potential for energetic recovery from BSG was investigated by measuring biogas production via the Anaerobic Digestion (AD) process. This process was carried out in batch laboratory-scale bioreactors (see Figure 1), operating under mesophilic conditions (37 °C) (Di Mario et al., 2025) [18]. The inoculum and biomass were mixed in a specific ratio of 3:1 based on VS weight. To quantify biomethane production, an alkaline trap containing 0.5 M NaOH and thymolphthalein (used as a pH indicator) was employed. The trap is capable of entirely absorbing carbon dioxide molecules, while leaving methane free to flow in the last vessel of the reactor. The complete separation of the two species is ensured in this way, and the two corresponding quantities can be easily measured.

Figure 1.

(A) Semi-batch bioreactor setup; (B) Bioreactor connected with alkaline CO2 trap (NaOH + thymolphthalein).

3.3. Definition of CO2 Avoided via Co-Digestion

The quantities of carbon dioxide, discussed in the experimental section, consider the amount measured within the biogas produced in each test and the quantity avoided, due to the conversion of organic carbon into biomethane instead of carbon dioxide.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All tests were performed in triplicate. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for each biomass type to compare the significance of differences between anaerobic and aerobic treatments. When significant differences were detected (p < 0.05), Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to determine pairwise differences. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R version 4.4.3 (2025-02-28 ucrt)). The results are shown in Supplementary Materials S1 and S2.

4. Results and Discussion

As organic carbon and nitrogen are the most important ingredients and the C/N ratio is a leading parameter for the AD process, the following C/N ratios were verified for the various biomasses considering the characterization of samples described in Table 1:

- -

- BSGp: 20.6;

- -

- LM: 6.9;

- -

- LM + BSGp: 10.6.

The ideal range for this parameter is commonly recognized to be equal to 10–20 [58,59]. The two separated biomasses fall outside this optimal range. In detail, the IL-based treatment significantly reduced the availability of nitrogen in the resulting pulp, thus making the C/N ratio slightly higher than the upper threshold. The opposite is true for LM, where the large availability of organic nitrogen significantly shifts the ratio far below the inferior limit. This explains why, as shown in the following paragraphs, biomethane production from LM alone was lower than that observed for BSGp. When used in combination, the nitrogen-rich LM helped achieve an optimal nutrient balance in the co-digested sample. As a result, the C/N ratio decreased from 20.57 in BSGp to 10.58 in the co-digested LM + BSGp sample. These numerical values explain why LM and BSGp were specifically selected for co-digestion tests and support the comprehension of the results described in the next paragraphs.

Furthermore, in the case of the treated biomass, BSGp, the IL caused significant delignification, as indicated by the increase in the cellulose/lignin ratio, which, as shown in Table 1, rose from 1.24 to 6.84. Furthermore, treatment with IL effectively removed hemicellulose from the biomass, reducing it from 59.28% of the raw material to 1.65% in the pulp. These results showed a BSGp strongly enriched in cellulose, but as already stated, depleted in nitrogen. In addition, a recent study by Li Q. et al. (2025) [60] also reported that a very low percentage of hemicellulose can inhibit the anaerobic digestion process. This finding also supports the use of co-digestion, as mixing BSGp with LM results in a fiber composition more suitable for the process.

In order to ensure the accuracy of results and the reliability of experiments, each biomass was tested in triplicate, following the procedure previously described in Section 2.

The cumulative biogas production, normalized per unit mass of volatile solids, for each residual tested, is attached to the present article as Supplementary Material. Data are reported in Nm3biogas/gVS to facilitate comparability with data and, more in general, studies already available in the literature. The values shown in the table allow for verifying the total amount of biogas extracted and, at the same time, quantifying the daily production.

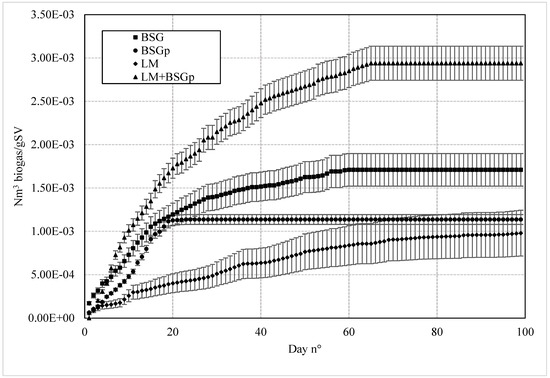

The cumulative biogas production is also plotted in Figure 2 where for each sample, the uncertainty range was defined.

Figure 2.

Cumulative biogas production for BSG (square dots), BSGp (circles), LM (rhombuses) and LM + BSG (triangles), with the corresponding level of confidence. BSG: Brewery’s Spent Grain; BSGp: Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp; LM: Lemna minor; LM + BSGp: Lemna minor + Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp.

The various samples showed different production periods. In detail, the AD process lasted 19 days for BSGp, while the process continued until day 59 for untreated BSG. Conversely, 99 days passed before the process completion for LM, while the co-digestion of LM + BSGp required 65 days.

If tested separately, the two matrices tested in co-digestion showed the shortest (BSGp) and the longest (LM) production periods, respectively. Based on the biomass characterization previously discussed and at the base of the proposed co-digestion, the reason can be attributed to the lack of nitrogen observed for BSGp and the opposite abundance of this nutrient in LM (1.76 vs. 4.78%). The cumulative biogas production with BSGp followed the same trend observed for BSG until day 19; then the process prematurely stopped due to the exhaustion of the nutrients required for bacterial proliferation and conversion activity.

The use of LM in co-digestion with BSGp allowed for overcoming that hindrance, providing sufficient nutrients (particularly nitrogen) to the entire sample, enabling it to reach process completion and convert as much carbon as possible into biogas.

It should be noted that the shorter the production period, the lower the energy consumption will be, especially when considering a field-scale AD apparatus. However, achieving the maximum conversion possible is a crucial and mandatory target, both in terms of energy production and consequent optimization of costs, and in terms of minimization of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere (the unexhausted residuals would inevitably go through aerobic digestion, with consequent CO2 emissions).

Except for tests carried out with only BSGp, the AD process was always completed, and the cumulative production curves showed the typical asymptotic trend, associated with the gradual extinction of organic carbon available for biogas production [61,62,63,64]. Furthermore, the final pH values at the end of the AD process were analyzed and found to be 7.7 for BSG digestate, 7.5 for BSGp digestate, 7.8 for LM digestate, and 7.7 for LM + BSG digestate.

Table 2 provides, for each sample, the total amount of biogas produced (corresponding to the last line of the table showing the cumulative biogas production and included as Supplementary Material), the percentage of biomethane it contained, and the consequent total quantity of biomethane achieved. The level of confidence of these latter values is obviously associated with the uncertainty described in Figure 2 and is numerically indicated in the present table.

Table 2.

For each sample and from left to right: total biogas produced (Nm3/gVS), percentage of biomethane contained in it (%) and total biomethane achieved (Nm3/gVS). Biomethane quantities are indicated with their corresponding confidence interval, expressed both as percentage and numerically.

The values shown in Table 2 confirm the yield drop between BSG and BSGp. The quantity of biogas produced per mass unit of the two samples dropped from 1.71 × 10−3 to 1.14 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS. The difference was still more pronounced when considering the amount of biomethane achieved with the different samples. As previously stated, the difference mainly depended on the low availability of nitrogen for BSGp, which acted as a limiting nutrient and stopped the microbial activity in advance. Tests carried out with LM registered results only slightly lower than BSGp: 0.79 × 10−4 Nm3/gVS for biogas and a still lower difference for biomethane (0.62 against 0.68 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS). For this latter biomass, the process yield primarily depended on the quantity of carbon available for transformation into biogas. Conversely, the abundance of nitrogen allowed for the optimization of the digestion process, which lasted 99 days, whereas it prematurely stopped after 19 days in tests made exclusively with BSGp. In terms of biomethane yield, BSG proved to be an excellent producer, while the other matrices reached similar concentration values, which is also consistent with the literature.

Finally, Table 2 highlights the synergy between BSGp and LM: the co-digestion of these two raw materials allowed us not only to balance the drop in production observed between BSG and BSGp, but also led to the highest production reached during the experimental phase, both in terms of biogas (2.94 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS) and for biomethane (1.81 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS).

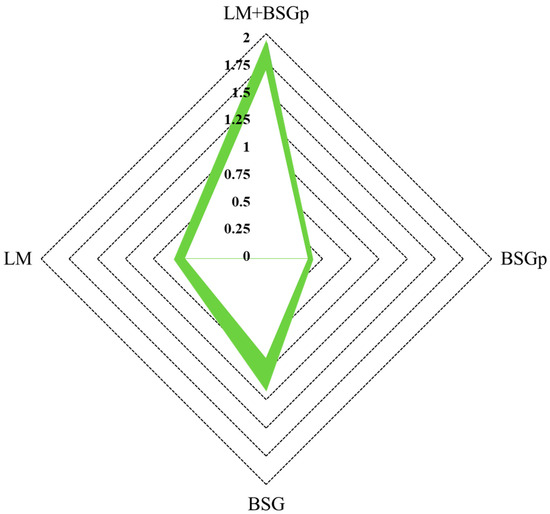

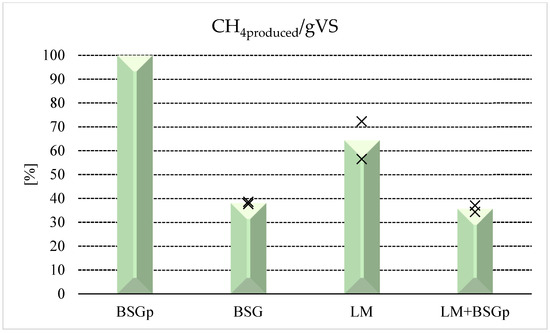

The following radar diagram (Figure 3) points out the quantity of carbon dioxide avoided by processing the different biomass via anaerobic digestion instead of using the aerobic process.

Figure 3.

Grams of CO2 avoided per mass unit (gVS) of each sample tested by applying anaerobic instead of aerobic digestion. BSG: Brewery’s Spent Grain; BSGp: Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp; LM: Lemna minor; LM + BSGp: Lemna minor + Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp. Being that each test was carried out in triplicate, the external border of the green region indicates the maximum values obtained, while the internal border shows the lowest values.

The degradation of biomass via anaerobic digestion clearly reduces the quantity of carbon dioxide emitted, if compared with the aerobic process, since part of the carbon is converted into methane. This effect of anaerobic digestion on waste management was also reported by Chicaiza-Ortiz, C.D et al. (2020) [22], where municipal solid waste showed reduced greenhouse gas emissions through anaerobic digestion, as confirmed by Life Cycle Assessment analysis. Before being converted into carbon dioxide, the produced methane would be used for conversion or energy production processes, thus providing a further cycle to carbon before being released into the atmosphere. Therefore, the diagram does not indicate the whole amount of CO2 related to the process, but exclusively the portion avoided due to the anaerobic digestion process. The quantities of carbon dioxide described in this study were calculated by considering the quantity of available carbon in the organic matrix, measuring the biogas produced and the corresponding content in biomethane.

For each sample tested, the diagram shows the range of CO2 avoided, provided with the green area included between the maximum and minimum values achieved during experiments.

In detail, this quantity ranged from 0.88 to 1.13 gCO2/gVS for BSG, from 0.38 to 0.4 for BSGp, from 0.73 to 0.8 for LM and from 1.68 to 1.91 gCO2/gVS for LM + BSGp.

The link between carbon dioxide avoided and methane produced is obviously proportional but absolutely not linear. Both the species are functions of the availability of carbon in the organic matrix; conversely, being that the process is carried out at anaerobic conditions, the quantity of carbon dioxide also depends on the abundance of organic oxygen. The availability of both these elements may also vary significantly among the various samples considered for this study.

The extraction of lignin via ionic liquids reduced the AD productivity, when carried out with the residual pulps (BSGp): 1.14 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS was produced, instead of 1.71 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS achieved with untreated BSG. Even if marked, that difference was widely lower than the one observed for carbon dioxide (the average quantity avoided for BSGp was 0.39 gCO2/gVS, more than two times lower than the same for BSG, equal to 1.01 gCO2/gVS).

Based on this latter assumption, the results obtained in the co-digestion tests can be only partially associated with the synergistic effect previously observed for biogas. The contemporary availability of carbon to convert and nutrients for bacteria enhanced the digestion process and drastically reduced the quantity of carbon which, in case of aerobic processes, would have been converted into carbon dioxide.

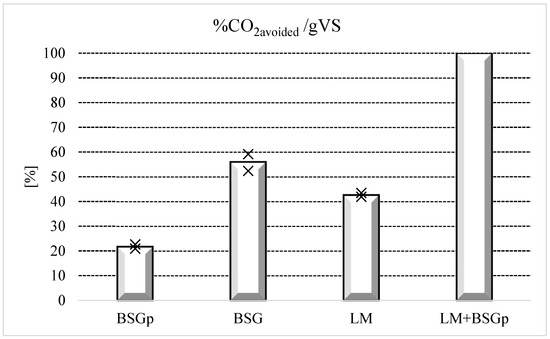

To better visualize this concept, Figure 4 and Figure 5 compare the different samples among each other, respectively, in terms of the quantity of carbon dioxide avoided and the quantity of biomethane produced. The results are shown as percentages and 100% was attributed to the sample having the highest performance, in order to normalize the remaining values as a function of it.

Figure 4.

Reduction in CO2 production for the various samples, expressed as percentage and normalized as a function of LM + BSG, the matrix which produced the highest absolute value for this parameter (mean value: 1.79 gCO2/gVS). BSG: Brewery’s Spent Grain; BSGp: Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp; LM: Lemna minor; LM + BSGp: Lemna minor + Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp. Cross symbols denote the range in which each measure falls within.

Figure 5.

Biomethane production achieved with the various samples, expressed as a percentage and normalized as a function of LM + BSG, the matrix which produced the highest absolute value for this parameter (mean value: 2.94 × 10−3 Nm3/gVS). BSG: Brewery’s Spent Grain; BSGp: Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp; LM: Lemna minor; LM + BSGp: Lemna minor + Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp. Cross symbols denote the range in which each measure falls within.

The histograms clearly show the reduction in biomethane production achieved with BSGp in comparison with untreated BSG. However, the difference in CO2 avoided is still more pronounced: 55.99% for BSG and 21.72% for BSGp. As stated in the previous tables, tests carried out with only LM reached the lowest results in terms of biogas/biomethane production; however, the AD process allowed us to obtain higher reduction in CO2 emissions, compared to tests made with BSGp.

The highest performances were achieved during co-digestion tests, especially in terms of carbon dioxide avoided, as the difference (expressed as a percentage) between each sample tested is wider than the difference detected for biomethane.

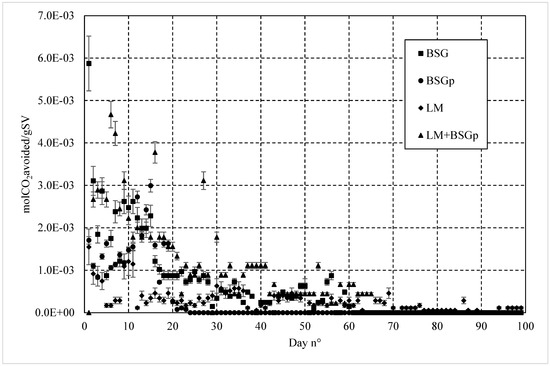

While the histograms describe the amount of carbon dioxide avoided and the quantity of biomethane produced as a percentage (to make the comparison between the various samples prompts), the following diagram (Figure 6) provides quantitative information about the amount of carbon dioxide daily avoided by treating the samples with anaerobic instead of aerobic digestion.

Figure 6.

Moles of carbon dioxide avoided (expressed per gram of VS), by processing the samples with anaerobic instead of aerobic digestion, during each day of experimentation. In the diagram, BSG is indicated with square dots, BSGp with circles, LM with rhombuses and LM + BSGp with triangles. BSG: Brewery’s Spent Grain; BSGp: Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp; LM: Lemna minor; LM + BSGp: Lemna minor + Brewery’s Spent Grain Pulp.

Finally, the total quantities of biomethane produced and indicated in Table 2 allows us to calculate the energy produced per mass unit (gVS) of each sample.

Considering the corresponding quantities of biomethane produced and assuming LHV = 52 MJ/kg [59], the energy produced with the samples tested in this work is equal to:

- -

- BSG: 43.3 ± 5.3 MJ/kgVS;

- -

- BSGp: 25.6 ± 0.3 MJ/kgVS;

- -

- LM: 19.3 ± 1.0 MJ/kgVS;

- -

- LM + BSGp: 64.9 ± 0.6 MJ/kgVS.

5. Conclusions

While the AD process has been widely investigated, and results are available elsewhere in the literature, defining promising options for co-digestion processes can be considered a key strategy for process intensification. The present study tested the AD process with a mixture containing BSG pulp (BSGp) and Lemna minor (LM). BSGp was selected since untreated BSG is a good biogas producer. While BSG showed a good performance in terms of biomethane production, BSGp revealed a marked reduction. In contrast, the BSGp co-digestion with LM evidenced a pronounced increase in biogas production. In fact, mixing these two raw biomasses allowed for equilibration of both the concentration of organic carbon and the availability of nitrogen within the optimal range required for the AD process. Co-digestion tests yielded relevant results in terms of CO2 mitigation, significantly lowering its production during the digestion process, thus enhancing the whole supply chain towards a fully developed circular economy scenario. Co-digestion strategies can improve waste management in breweries and aquatic biomass systems, enhancing net GHG avoidance verified by LCA or carbon footprint approaches.

When co-digested, LM + BSGp achieved the highest performance for both biomethane production and CO2 avoided, producing 64.9 ± 0.6 MJ/kgVS, the highest energetic value, and preventing 1.68–1.91 gCO2/gVS.

Although this study reports laboratory-scale results, it is important to highlight the broader implications of such waste management strategies, which remain a pressing challenge, particularly in certain regions of the world. In fact, the development of sustainable alternatives for biomass reuse can both enhance resource valorization and reduce disposal costs. Furthermore, biogas production represents a valuable source of renewable energy. At the community level, it can complement other renewable sources such as wind and solar power, thereby contributing to local energy self-sufficiency and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Future studies will consist of scaling up the system and also exploring the process kinetics, in order to make the result achieved in this research more suitable for industrial scopes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17229985/s1. S1: Cumulative biogas production, expressed as Nm3biogas/gVS, for the samples tested (from left to right: BSG, BSGp, LM and LM+BSGp). For each measure, the maximum deviation from the reported values, measured during the experimentation, was indicated with “σ”; S2: Tukey Test and std deviation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.G. and J.D.M.; methodology, A.M.G.; validation, D.D.B. and G.G.; formal analysis, J.D.M. and D.P.; investigation, A.M.G.; resources, G.G.; data curation, A.M.G., D.P. and J.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.G., J.D.M. and D.D.B.; supervision, G.G.; project administration, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—as part of the Na tional Innovation Ecosystem (grant ECS00000041—VITALITY) promoted by Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR). We thank University of Perugia and MUR for their support within the VITALITY project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Experimental data are already included in the text. More details are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSG | Brewery’s Spent Grain |

| BSGp | Pulp of Brewery’s Spent Grain |

| LM | Lemna minor |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| VS | Volatile Solids |

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| WEOC | Water-Extractable Organic Carbon |

| WEN | Water-Extractable Nitrogen |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

References

- Brown, K.W.; Donnelly, K.C. An Estimation of the Risk Associated with the Organic Constituents of Hazardous and Municipal Waste Landfill Leachates. Hazard. Waste Hazard. Mater. 1988, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, K.; Zong, J.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Lu, X. Anaerobic co-digestion process for biogas production: Progress, challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Parakh, S.K.; Tsui, T.H.; Bano, A.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, V.P.; Lam, S.S.; Nadda, A.K.; Tong, Y.W. Synergetic anaerobic digestion of food waste for enhanced production of biogas and value-added products: Strategies, challenges, and techno-economic analysis. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 1040–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Shi, Z.; Marinello, F.; Pezzuolo, A. From biogas to biomethane: Comparison of sustainable scenarios for upgrading plant location based on greenhouse gas emissions and cost assessments. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtoranta, S.; Tampio, E.; Rasi, S.; Laakso, J.; Vikki, K.; Luostarinen, S. The implications of management practices on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in biogas production. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, H. Comparative life-cycle assessment of various harvesting strategies for biogas production from microalgae: Energy conversion characteristics and greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 289, 117188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, S.E.; Silver, W.L. Greenhouse gas emissions from windrow composting of organic wastes: Patterns and emissions factors. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 124027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, Y. In situ Biogas Upgrading by CO2-to-CH4 Bioconversion. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Dai, L. Simultaneous enhancement of methane production and methane content in biogas from waste activated sludge and perennial ryegrass anaerobic co-digestion: The effects of pH and C/N ratio. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Verde, I.; Regueiro, L.; Carballa, M.; Hospido, A.; Lema, J.M. Assessing anaerobic co-digestion of pig manure with agroindustrial wastes: The link between environmental impacts and operational parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 497–498, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei-Moghadam, A.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H.; Aghel, H.; Aghkhani, M.H.; Abedini-Torghabeh, J. Enhancement of biogas production by co-digestion of potato pulp with cow manure in a CSTR system. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 1858–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbay, H.E.G. Anaerobic mono and co-digestion of agro-industrial waste and municipal sewage sludge: Biogas production potential, kinetic modelling, and digestate characteristics. Fuel 2024, 355, 129468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounni, F.; Elgnaoui, Y.; El Bari, H.; Merzouki, M.; Benlemlih, M. Effect of mixture ratio and organic loading rate during anaerobic co-digestion of olive mill wastewater and agro-industrial wastes. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravani, V.P.; Tsigkou, K.; Papadakis, V.G.; Wang, W.; Kornaros, M. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Agricultural Residues Produced in Southern and Northern Greece. Fermentation 2023, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabbai, V.; Ballico, M.; Aneggi, E.; Goi, D. BMP tests of source selected OFMSW to evaluate anaerobic codigestion with sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Boe, K.; Angelidaki, I. Anaerobic co-digestion of by-products from sugar production with cow manure. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yao, W.; Zhu, J.; Miller, C. Biogas and CH4 productivity by co-digesting swine manure with three crop residues as an external carbon source. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4042–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mario, J.; Bertoldi, A.; Priolo, D.; Calzoni, E.; Gambelli, A.M.; Dominici, F.; Rallini, M.; Del Buono, D.; Puglia, D.; Emiliani, C.; et al. Characterization of Processes Aimed at Maximizing the Reuse of Brewery’s Spent Grain: Novel Biocomposite Materials, High-Added-Value Molecule Extraction, Codigestion and Composting. Recycling 2025, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monties, B. Plant cell walls as fibrous lignocellulosic composites: Relations with lignin structure and function. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1991, 32, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Khalid, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, G.; Chen, C.; Thorin, E. Methane production through anaerobic digestion: Participation and digestion characteristics of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicaiza-Ortiz, C.D.; Villa, V.P.N.; Lòpez, C.O.C.; Chicaiza-Ortiz, Á.F. Evaluation of municipal solid waste management system of Quito-Ecuador through life cycle assessment approach. LALCA Rev. Lat. Am. Aval. Ciclo Vida 2020, 4, e45206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicaiza-Ortiz, C.; PenafielArcos, P.; Herrera-Feijoo, R.J.; Ma, W.; Logrono, W.; Tian, H.; Yuan, W. Waste-to-energy technologies for municipal solid waste management: Bibliometric review, life cycle assessment, and energy potential case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 480, 143993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazawa, A.; Iikura, T.; Morioka, Y.; Shino, A.; Ogata, Y.; Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Cellulose Digestion and Metabolism Induced Biocatalytic Transitions in Anaerobic Microbial Ecosystems. Metabolites 2013, 4, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhang, N.; Philips, G.C.; Xu, J. Growing Lemna minor in agricultural wastewater and converting the duckweed biomass to ethanol. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 124, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Gujral, G.S.; Jha, N.K.; Vasudevan, P. Production of biogas from Azolla pinnata R.Br and Lemna minor L.: Effect of heavy metal contamination. Bioresour. Technol. 1992, 41, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; Han, Z.; Zeng, G.; Lu, L.; He, S. Effect of zinc ions on nutrient removal and growth of Lemna aequinoctialis from anaerobically digested swine wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.P.; Bhatt, N. Aquatic weed Spirodela polyrhiza, a potential source for energy generation and other commodity chemicals production. Renew. Energy 2021, 173, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G. The application and treatment of freshwater macrophytes as potential biogas base materials: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedergreen, N.; Madsen, T.V. Nitrogen uptake by the floating macrophyte Lemna minor. New Phytol. 2002, 155, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chusov, A.; Maslikov, V.; Badenko, V.; Zhazhkov, V.; Molodtsov, D.; Pavlushkina, Y. Biogas Potential Assessment of the Composite Mixture from Duckweed Biomass. Sustainability 2022, 14, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souvannasouk, V.; Unpaprom, Y.; Ramaraj, R. Bioconverters for biogas production from bloomed water fern and duckweed biomass with swine manure co-digestion. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2021, 3, 972–981. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, M.; Lagerkvist, A.; Morgan-Sagastume, F. The Effects of Substrate Pre-Treatment on Anaerobic Digestion Systems: A Review. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1634–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, P. Biogas Production: Current State and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mario, J.; Montegiove, N.; Gambelli, A.M.; Brienza, M.; Zadra, C.; Gigliotti, G. Waste biomass treatments for biogas yield optimization and for the extraction of valuable high-added-value products: Possible combinations of the two processes toward a biorefinery purpose. Biomass 2024, 4, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, E.; Benincasa, P.; Balestra, G.M.; Luzi, F.; Mazzaglia, A.; Del Buono, D.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L. Revalorization of Barley Straw and Husk as Precursors for Cellulose Nanocrystals Extraction and Their Effect on PVA_CH Nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 92, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahring, B.K.; Biswas, R.; Ahamed, A.; Teller, P.J.; Uellendahl, H. Making Lignin Accessible for Anaerobic Digestion by Wet Explosion Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 175, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankar, A.R.; Pandey, A.; Modak, A.; Pant, K.K. Treatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review on Recent Advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Rasid, N.S.; Shamjuddin, A.; Abdul Rahman, A.Z.; Amin, N.A.S. Recent Advances in Green Pre-Treatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Enhanced Biofuel Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 129038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-García, M.; Moreno, A.D.; Manzanares, P.; Negro, M.J.; Duque, A. Recent Advances on Physical Technologies for the Treatment of Food Waste and Lignocellulosic Residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, W.; Wong, J.W.C.; Yong, X.; Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Jia, H. Ultrasonic and Thermal Treatments on Anaerobic Digestion of Petrochemical Sludge: Dewaterability and Degradation of PAHs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136162. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, B.; Barua, V.B.; Khwairakpam, M.; Haq, I.; Kalamdhad, A.S.; Varjani, S. Thermal Treatment of Lantana Camara for Improved Biogas Production: Process Parameter Studies for Energy Evaluation. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yoon, Y.-M.; Han, S.K.; Kim, D.; Kim, H. Effect of Hydrothermal Pre-Treatment (HTP) on Poultry Slaughterhouse Waste (PSW) Sludge for the Enhancement of the Solubilization, Physical Properties, and Biogas Production through Anaerobic Digestion. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.; Starrenburg, D.; Tait, S.; Barr, K.; Batstone, D.J.; Lant, P. Decreasing Activated Sludge Thermal Hydrolysis Temperature Reduces Product Colour, without Decreasing Degradability. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4699–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. Treatment for Biogas Production by Anaerobic Fermentation of Mixed Corn Stover and Cow Dung. Energy 2012, 46, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, T.H. A Review on Alkaline Treatment Technology for Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.; Johansen, K.S.; Meyer, A.S. Low Temperature Lignocellulose Treatment: Effects and Interactions of Treatment PH Are Critical for Maximizing Enzymatic Monosaccharide Yields from Wheat Straw. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.C.; Iten, L.B.; Cotta, M.A.; Wu, Y.V. Dilute Acid Treatment, Enzymatic Saccharification, and Fermentation of Rice Hulls to Ethanol. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008, 21, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.K.; Xu, C.; Qin, W. Biological Treatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuels and Bioproducts: An Overview. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjpe, A.; Saxena, S.; Jain, P. Biogas Yield Using Single and Two Stage Anaerobic Digestion: An Experimental Approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiliñir, C.; Pinto-Villegas, P.; Castillo, A.; Montalvo, S.; Guerrero, L. Biochemical Methane Potential from Sewage Sludge: Effect of an Aerobic Treatment and Fly Ash Addition as Source of Trace Elements. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, Y.P.; Putra, R.D.D.; Widyaya, V.T.; Ha, J.M.; Suh, D.J.; Kim, C.S. Comparative study on two-step concentrated acid hydrolysis for the extraction of sugars from lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 164, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolisano, C.; Luzi, F.; Regni, L.; Proietti, P.; Puglia, D.; Gigliotti, G.; Di Michele, A.; Priolo, D.; Del Buono, D. A way to valorize pomace from olive oil production: Lignin nanoparticles to biostimulate maize plants. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 31, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cequier, E.; Aguilera, J.; Balcells, M.; Canela-Garayoa, R. Extraction and characterization of lignin from olive pomace: A comparison study among ionic liquid, sulfuric acid, and alkaline treatments. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2019, 9, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessie, W.; Luo, X.; Wang, M.; Feng, L.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yong, Z.; Qin, Z. Current advances on waste biomass transformation into value-added products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 4757–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montegiove, N.; Gambelli, A.M.; Calzoni, E.; Bertoldi, A.; Puglia, D.; Zadra, C.; Emiliani, C.; Gigliotti, G. Biogas production with residuals deriving from olive mill wastewater and olive pomace wastes: Quantification of produced energy, spent energy, and process efficiency. Agronomy 2024, 14, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Gregorich, E. Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J. Use of detergents in the analysis fibrous feeds. I. Preparation offiber resi-dues of low nitrogen content. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1963, 46, 825–835. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zoubi, A.I.; Alkhamis, T.M.; Alzoubi, H.A. Optimized biogas production from poultry manure with respect to pH, C/N, and temperature. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liang, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, B.; Yin, F.; Zhang, W. Lignocellulose Binary Component Ratios for Optimizing Methane Production in Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 345, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Effects of C/N ratio variation in swine biogas slurry on soil dissolved organic matter: Content and fluorescence characteristics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, S.K.; Ancha, V.R.; Habtu, N.G.; Binchebo, T.L. Enhancing biogas production from tannery wastewater via the incorporation of different quantities of spent coffee grounds. Desalin. Water Treat. 2025, 323, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantedeschi, S.; Valenti, F.; Maraldi, M.; Martinez, G.A.; Tura, M.; Valli, E.; Toschi, T.G. Effect of blending olive leaves and olive mill wastewater on the potential biogas production. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarysta, V.; Rodriguez, S.B.; Torre, R.M. Trisynergy of photosynthetic biogas upgrading, anaerobic digestate bioremediation, and pigment biosynthesis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).