Abstract

This study validates an empirical model of attitudinal indicators to assess the inclusion of students with physical motor disabilities in higher education. Grounded in the tripartite model of attitude and framed within the social model of disability, the research employed the SACIE-R scale to measure emotional, cognitive, and behavioral predispositions among 384 faculty members from private universities in El Salvador, selected through stratified sampling. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) identified three latent dimensions—concerns and general attitudes, inclusive feelings, and cognitive–affective tension—explaining 56.36% of the variance, with strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.876). Chi-square tests revealed significant attitudinal differences by age, sex, training, and institutional affiliation. The resulting model translates latent predispositions into observable indicators of inclusive teaching competencies, providing a diagnostic and evaluative tool for higher education institutions. Beyond the Salvadoran context, the framework demonstrates potential scalability across Latin American systems with comparable socio-educational conditions. Importantly, the model contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4, SDG 10, and SDG 16) by supporting inclusive and equitable quality education, reducing structural inequalities, and informing governance policies grounded in human rights. Findings highlight persistent attitudinal barriers and limited faculty preparedness, underscoring the need for sustainable institutional strategies. This research advances the debate on educational sustainability by linking faculty attitudes to long-term policy development, capacity-building, and institutional accountability.

1. Introduction

Higher education has emerged as a strategic platform for advancing inclusive societies, particularly in the Global South, where structural inequalities disproportionately affect people with disabilities [1,2,3,4]. Despite normative and discursive progress, attitudinal, pedagogical, and organizational barriers continue to restrict access, retention, and the full participation of students with physical motor disabilities (PMD) in Latin American universities [4,5,6,7,8].

This study deliberately focuses on PMD, as mobility-related barriers remain among the most visible and pressing challenges for inclusive higher education in El Salvador and across Latin America. Restricting the analysis to PMD ensures methodological rigor. The recognition of the right to inclusive education—enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [9] and reaffirmed by the Sustainable Development Goals (particularly SDG 4.5)—underscores the urgency of guaranteeing equitable conditions across all educational levels, including higher education [10,11]. Recent scholarship underscores that sustainable disability inclusion in higher education requires progress not only on SDG 4.5 (equal access to education) but also on SDG 10 (reducing inequalities) and SDG 16 (building inclusive and accountable institutions), as these goals collectively frame institutional policies and governance mechanisms essential for embedding long-term change in higher education systems [12,13].

Extensive research highlights that faculty attitudes are a decisive factor in either facilitating or hindering inclusive education processes [14,15]. However, in Latin America—and especially in El Salvador—empirical evidence on faculty attitudes toward students with disabilities remains scarce, fragmented, and often lacks psychometrically validated instruments [16]. This gap limits the capacity of higher education institutions (HEIs) to accurately assess faculty predispositions, design effective training programs, and evaluate the implementation of institutional inclusion policies [17,18,19]. Recent sustainability research emphasizes that addressing such gaps is fundamental for advancing SDG 10 by reducing inequalities through evidence-based policies [13].

From a critical perspective, it is necessary to move beyond normative declarations by incorporating tools that systematically assess faculty attitudes as measurable constructs [20,21]. Negative or ambivalent attitudes often act as symbolic barriers that reproduce exclusionary dynamics, even when physical infrastructure and accessible technologies are available [22,23]. Faculty beliefs, emotions, and behavioral predispositions remain decisive in determining the success of inclusive practices [24,25,26]. At the same time, strengthening institutional frameworks for inclusion is essential to advance SDG 16, which emphasizes accountable and participatory governance in higher education [10,12,27,28].

In this context, empirical models that disaggregate and quantify the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of attitudes are essential [29,30,31,32]. This study addresses this need by proposing and validating an empirical model of attitudinal indicators based on the SACIE-R scale (Faculty Attitudes toward Inclusive Education—Revised) [33], adapted to the Salvadoran higher education context. The scale was subjected to EFA, which revealed three latent dimensions: emotional disposition, inclusive commitment, and perception of barriers, together explaining a significant proportion of attitudinal variance [34]. A quantitative design was selected to provide robust statistical evidence that supports institutional diagnostics, cross-institutional comparisons, and the development of faculty improvement strategies [35,36].

These validated attitudinal indicators offer a reliable tool for developing faculty improvement strategies and monitoring inclusion policies [36]. By linking individual dispositions to institutional frameworks, the model contributes to SDG 4 by fostering inclusive education and to SDG 16 by strengthening higher education governance with evidence-based tools, thereby advancing educational sustainability in the region [28]. The study also aims to contribute a replicable tool for other Latin American countries with similar socio-educational characteristics [37,38], thus addressing both theoretical and practical gaps in the literature on the inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education.

Unlike broader international instruments such as the Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons with Disabilities (MAS) or the Attitudes Toward Students with Disabilities in Inclusive Settings (ATSI), the novelty of this study lies in validating a faculty-specific model that operationalizes attitudes into measurable indicators directly linked to teaching competencies. This contextual sensitivity represents a distinctive contribution to the literature on inclusive higher education. Its focus on faculty-specific scenarios and inclusion-related dilemmas allows for a more precise operationalization of attitudes within higher education contexts [39].

Moreover, the SACIE-R has demonstrated adaptability across Latin American cultural settings, making it especially suitable for the Salvadoran context, where standardized instruments remain scarce. By providing an evidence-based tool for regional adaptation, the study contributes to SDG 10 by reducing inequalities in access to higher education and to SDG 16 by strengthening institutional frameworks that support inclusive and sustainable educational policies [12].

Building on this rationale, the SACIE-R was selected as the most appropriate instrument to validate in the Salvadoran higher education context. This study represents the first formal validation of the SACIE-R in El Salvador and one of the few systematic validations in Central America. A comparative summary of these tools is provided in Supplementary Table S1 to underscore the model’s innovation and alignment with inclusive teaching standards.

Furthermore, the methodological approach aligns with international quality assurance standards, including those of the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) and the Index for Inclusion by Booth and Ainscow [20]. It also integrates frameworks on inclusive teaching competencies endorsed by multilateral organizations, ensuring both international comparability and contextual adaptation.

The validation of this model is particularly relevant in light of expanding access to higher education and the growing diversity of student populations, which call for differentiated, culturally responsive, and pedagogically grounded strategies [21,22,23]. By providing a reliable tool for inclusive policy and practice, this study advances SDG 4 by promoting equitable access to quality education and contributes to SDG 16 by strengthening institutional frameworks that sustain inclusive governance in higher education [13].

Ultimately, this article aims to provide a statistically validated model for assessing higher education faculty attitudes toward the inclusion of students with physical motor disabilities. By combining methodological rigor, contextual relevance, and practical utility, this model serves as a diagnostic, formative, and evaluative tool. It supports institutional improvement and faculty development while advancing the principles of inclusive education, human rights, and social justice. In doing so, the study also contributes to SDG 4 by promoting inclusive and equitable quality education, and to SDG 10 by reducing barriers that perpetuate inequalities in higher education.

Grounded in this rationale, the study is structured around two research questions that guide its empirical validation:

(RQ1) What are the underlying dimensions of university faculty attitudes toward the inclusion of students with PMD in Salvadoran higher education?

(RQ2) How valid and reliable is the culturally adapted SACIE-R scale for assessing these attitudes?

1.1. Definitions of Key Terms

This section defines the central concepts that underpin the proposed empirical model of attitudinal indicators, ensuring conceptual clarity and alignment with the theoretical framework, research objectives, and psychometric design of the study.

1.1.1. Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is a rights-based and equity-driven approach that ensures full participation, access, and learning opportunities for all students, regardless of disability, background, or personal characteristics. In the context of higher education, it entails the systematic removal of pedagogical, structural, and attitudinal barriers, and the promotion of institutional cultures that embrace diversity and social justice.

1.1.2. Physical Motor Disability

A physical motor disability refers to a condition that affects a person’s ability to move, coordinate, or perform physical tasks due to neuromuscular, skeletal, or central nervous system impairments. In higher education, students with PMD may require environmental adaptations, assistive technologies, and inclusive pedagogical practices to enable meaningful participation in academic life.

1.1.3. Faculty Attitudes

Faculty attitudes encompass the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral tendencies of university instructors toward the inclusion of students with disabilities. These attitudes influence teaching practices, perceptions of diversity, and the implementation of inclusive policies. Positive attitudes are essential to cultivating inclusive and accessible learning environments.

1.1.4. Attitudinal Indicators

Attitudinal indicators are empirically measurable variables that reflect faculty members’ predispositions toward inclusion. In this study, they are operationalized through three latent factors identified via EFA: emotional disposition, inclusive commitment, and perception of barriers. These indicators provide the basis for evaluating institutional progress in inclusive education.

1.1.5. Emotional Disposition

Emotional disposition refers to the affective responses of faculty toward students with physical motor disabilities. This includes attitudes of empathy, discomfort, fear, or emotional openness, which directly influence interpersonal interactions and willingness to support inclusive practices in the classroom.

1.1.6. Inclusive Commitment

Inclusive commitment denotes the degree of engagement and proactive involvement of faculty in adapting their teaching methods, curricula, and learning environments to meet the needs of students with disabilities. It reflects the ethical and pedagogical responsibility to uphold inclusive values.

1.1.7. Perception of Barriers

Perception of barriers involves faculty recognition of institutional, pedagogical, or personal challenges that may impede inclusion. This includes perceived limitations such as inadequate training, lack of resources, or rigid academic structures that hinder inclusive practices.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Inclusive Education and Physical Motor Disabilities in Higher Education

Inclusive education in higher education is increasingly recognized as a transformative approach that dismantles structural, epistemological, and attitudinal barriers that exclude students with disabilities [40,41,42]. Frameworks such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [9] and Sustainable Development Goal 4.5 [11] have created global momentum toward inclusive practices. Despite this progress, implementation across higher education institutions remains uneven, particularly in the Global South, where policies often fail to reach classroom practices [1,3,19,36,43,44,45,46]. At the same time, recent bibliometric analyses highlight that universities are increasingly integrating sustainability agendas, although the incorporation of equity and inclusion as part of these agendas remains limited and fragmented [13].

In Latin American universities, students with PMD continue to encounter barriers despite normative advances. PMD refers to limitations in movement, coordination, or physical functioning caused by neurological, muscular, or skeletal conditions. Many universities address accessibility mainly through infrastructure, neglecting deeper attitudinal and pedagogical transformations [4,47,48,49]. Recent scholarship highlights the importance of moving beyond accessibility to embrace Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, which proactively design for diversity [42,50]. Critical disability studies in Latin America also reveal how colonial legacies shape educational models that reproduce exclusion through epistemic and institutional norms [51].

In El Salvador, inclusive education policies have been adopted nationally, but their application in higher education institutions remains inconsistent and weakly monitored [11]. Faculty attitudes are central to this gap: negative or ambivalent perceptions often lead to low expectations, minimal accommodations, and limited opportunities for participation [14,34]. This study addresses these gaps by offering empirical evidence from El Salvador and proposing an attitudinal model grounded in local realities. It frames inclusion not only as access but also as transformation of pedagogies, mindsets, and institutional cultures, positioning it as a cornerstone of educational sustainability aligned with SDGs 4, 10, and 16.

1.2.2. Faculty Attitudes as Critical Determinants of Inclusion

Faculty perceptions are shaped by discipline, prior experience, and institutional support [52,53]. STEM faculty often show greater resistance than those in social sciences and education [54]. In Latin American universities, deficit and charity-based conceptions remain influential, shaping expectations and willingness to accommodate students [55].

Validated instruments are crucial for assessing faculty attitudes toward inclusion, particularly in Latin American contexts where psychometric tools remain scarce. Recent initiatives, such as the Questionnaire on Attitudes towards Disability in Higher Education (QAD-HE), provide evidence of the importance of culturally adapted scales [48]. Faculty attitudes—affective, cognitive, and behavioral predispositions toward inclusion—are central to implementing inclusive practices [29,30,31,32]. These dispositions directly affect teaching, classroom dynamics, and curriculum. Yet, even initiatives framed as inclusive curricula may inadvertently reproduce exclusion if underlying institutional norms and power dynamics are not critically addressed [56]. This highlights the complexity of fostering genuine attitudinal change in higher education.

Negative or ambivalent attitudes often stem from limited exposure to disability discourse and insufficient training [24,25,26]. Universities that embed inclusive pedagogical frameworks report improved perceptions [17,53]. Still, many professors demonstrate low levels of psychological readiness and self-perceived competence for inclusive teaching, underlining the importance of sustained professional development [57]. This underscores the close connection between teacher competence and educational sustainability.

Measuring dispositions requires validated scales. The SACIE-R, adapted to El Salvador, identifies three dimensions: emotional disposition, inclusive commitment, and perceived barriers [34]. Other culturally adapted tools also help detect resistance points and design interventions [1,43,44]. Over time, exposure to diverse students and structured reflection can improve attitudes [58]. This study contributes by validating SACIE-R in Central America, expanding the psychometric repertoire in inclusive education research. Tools such as ATSI and MAS have been valuable but insufficient to capture cultural and institutional nuances [14,39]. The SACIE-R provides a multidimensional framework better suited for policy, diagnosis, and faculty development, supporting inclusive and sustainable higher education.

1.2.3. The Role of Faculty Training and Institutional Policies

Faculty attitudes are widely recognized as critical determinants in the implementation of inclusive education in higher education. These attitudes—affective, cognitive, and behavioral—shape how instructors accommodate students with disabilities [29,30,31,32]. Positive attitudes foster inclusive strategies, while negative or ambivalent ones perpetuate systemic inequalities [24,25,26,59]. Several factors influence these attitudes: discipline, prior interactions with students with disabilities, institutional support, and training levels [52,53]. In STEM, predisposition is often lower compared to humanities or education, where social justice discourses are more prevalent [54]. This gap suggests the need for tailored faculty development programs across fields.

In Latin America, deficit-oriented or charity-based views of disability remain embedded in cultural and institutional narratives [55]. These perceptions limit faculty commitment to accommodations and inclusive practices. Overcoming them requires more than technical training; it calls for critical reflection on academic ableism, power relations, and normative teaching standards.

Validated instruments are crucial to monitor these dispositions. The SACIE-R scale, adapted in this study, offers a culturally sensitive tool capturing emotional disposition, inclusive commitment, and perceived barriers [34]. Disaggregating these dimensions provides a nuanced view of how inclusion is supported—or hindered—within universities. Evidence shows faculty attitudes are not immutable. Exposure to students with disabilities, reflective training, and institutionalized policies can enhance perceptions over time [58,60]. Measuring attitudes thus becomes both diagnostic and formative, guiding continuous improvement and fostering equity in higher education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study adopted a quantitative, non-experimental, cross-sectional design consistent with previous research on psychometric validation in inclusive education [22,33,35,61]. Such a design allows for the empirical examination of latent attitudinal structures and their relationship with institutional inclusion processes. The main objective was to construct and validate an empirical model of attitudinal indicators to assess university faculty perceptions regarding the inclusion of students with PMD in higher education institutions in El Salvador.

The validation procedure was carried out in three stages. First, content validity was established through expert review, as recommended in prior Latin American validation studies [14,48]. Four experts were selected—two specialists in inclusive education and two in psychometrics—based on their academic credentials and experience. Selection followed the principles of participatory evaluation in inclusive education frameworks [20,60], ensuring both disciplinary and methodological expertise.

Second, a pilot test with 64 university faculty members was implemented to verify item clarity and cultural relevance [34]. Third, the refined version of the SACIE-R [33], was administered to the main sample for exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency testing [22,35,36,62,63]. This sequential process ensured methodological rigor and contextual validity of the adapted instrument. The validated SACIE-R scale was culturally and contextually adapted to the Salvadoran setting and administered online through institutional email networks and Google Forms. Psychometric analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26 to confirm the instrument’s reliability and construct validity.

2.2. Ethical Considerations and Approval

This study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [64] and international guidelines for research with human participants [65]. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the coordinating university (Resolution No. CEI-USAM-2024-030, issued on 25 January 2024), confirming compliance with institutional and international standards of academic integrity and professional ethics. Prior to beginning the questionnaire, participants received detailed information about the study objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, data confidentiality, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. The study involved minimal risk; no personally identifiable information was collected. All responses were anonymized, coded, and stored on secure, access-restricted servers to safeguard privacy and minimize foreseeable physical, psychological, or legal risks.

Electronic informed consent was obtained before survey access. To support comprehension in a digital environment, the consent page first presented a plain-language summary (purpose, voluntary participation, anonymity/confidentiality, data use, and withdrawal options) followed by the full text. Participants were required to scroll through the entire consent and actively check an affirmative box (“I have read and understood the information and agree to participate”) before proceeding. The page provided a downloadable PDF of the consent and contact information (email and phone) for questions or clarifications. Timestamps were stored for auditability, and no personally identifying information was collected beyond what was specified in the consent.

2.3. Research Instrument

The SACIE-R scale served as the main data collection instrument. It includes 12 items grouped into three theoretically grounded and empirically validated components: (a) Emotional Disposition (items reflecting empathy, discomfort, or anxiety toward students with PMD), (b) Inclusive Commitment (items assessing beliefs about students’ right to inclusive education, pedagogical flexibility, and institutional responsibility), and (c) Perception of Barriers (items related to perceived constraints such as lack of resources, insufficient training, or concerns about academic quality).

For clarity, these labels represent the theoretical constructs guiding the initial design. Following the EFA, the empirical results suggested slightly different labels—Concerns and General Attitudes, Inclusive Feelings, and Cognitive–Affective Tension—that better captured the attitudinal structure observed in the Salvadoran faculty sample. Each item was measured on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 4 = Strongly Agree).

The instrument was adapted from Spanish-language versions validated in Latin America and reviewed by four experts in inclusive education and psychometrics. In addition, a demographic section collected information on sex, age, teaching experience, disciplinary area, and prior inclusive education training. A pilot test with 20 faculty members demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.80), a threshold commonly accepted for psychometric reliability [48,62]. This step confirmed the reliability of the scale as a diagnostic and evaluative tool in higher education settings.

2.4. Sampling Technique

A stratified random sampling strategy was implemented to ensure representativeness across institutions and disciplines. The target population comprised university faculty from private higher education institutions in El Salvador who were actively teaching undergraduate programs. Faculty members from all areas of knowledge were included without disciplinary exclusion, provided they held active teaching responsibilities.

A total of 384 respondents participated, exceeding the minimum required sample size for factor analysis based on a subject-to-item ratio above 10:1 [66] (To justify the adequacy of the sample, we combined on a priori fit-index approach and a rule-of-thumb ratio. First, following RMSEA-based power reasoning for CFA (H0: RMSEA = 0.05 vs. H1: 0.08; α = 0.05; 1 − β = 0.90) and considering the degrees of freedom of the hypothesized three-factor model with twelve indicators (df ≈ 51), we targeted a minimum N ≥ 300 to achieve adequate power for close-fit testing. Second, we adopted a respondents-to-parameters ratio of at least 10:1, which—given approximately thirty free parameters (primary loadings, indicator residuals, and factor covariances with factor variances fixed)—also implied N ≥ 300. Our final sample (N = 384) exceeds both criteria and aligns with common recommendations for CFA with ordinal indicators and three correlated factors [67,68,69,70].). The dataset met key statistical assumptions for factor analysis, with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.85 and a significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.001). These results supported the appropriateness of factor extraction and dimensional reduction techniques.

Given the categorical nature of the SACIE-R responses and sociodemographic variables, Chi-square tests were employed to explore associations. While alternative models such as ANOVA or regression could be applied, the exploratory aim of this study justified the use of Chi-square, with future research encouraged to expand the analysis through more complex multivariate approaches. These indicators confirmed the suitability of the dataset for subsequent exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, described in the following sections.

2.5. Statistical Validation of the Model

To validate the proposed attitudinal model, the statistical analyses were organized hierarchically in four consecutive stages. First, a set of descriptive statistics was calculated to characterize the sample and establish the initial context of the study. Second, the reliability of the instrument was assessed to ensure internal consistency of the adapted SACIE-R scale. Third, an EFA was conducted to identify the latent structure underlying the items and to examine construct validity.

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to test the robustness of the three-factor solution and to verify the goodness-of-fit of the measurement model. This sequential design ensured a comprehensive psychometric validation, moving from descriptive and exploratory approaches toward confirmatory analyses that strengthen the empirical and theoretical contributions of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

The final sample consisted of 384 university faculty members from private higher education institutions in El Salvador. A slight majority of participants were male (56.3%), while 43.8% identified as female. The most represented age group was 30–34 years (21.1%), and the majority of respondents (65.9%) fell within the 25 to 44-year range, indicating a relatively young teaching population.

Only 5.5% of respondents reported having received specialized training in inclusive education, highlighting significant gaps in professional development for inclusion. Moreover, 21.6% of faculty indicated having contact with individuals with PMD within the university context. Among them, the most common frequency of interaction was once per week (62.7%), and 57.8% reported this contact occurred in their role as instructors of students with PMD.

These findings point to limited experiential exposure and training, underscoring the need for capacity-building strategies to strengthen inclusive practices in higher education. Comparable results have been reported in other Latin American settings, where faculty often lack structured preparation for disability inclusion [71,72]. Such patterns emphasize the urgency of sustainable faculty development policies to bridge the persistent gap between inclusion discourse and classroom practice.

3.2. Instrument Reliability

The psychometric reliability of the adapted SACIE-R scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. The instrument, composed of 12 items grouped into three dimensions, showed high internal consistency. Emotional Disposition (5 items) obtained α = 0.862, Concerns (4 items) α = 0.819, and Inclusive Commitment (3 items) α = 0.842. The overall scale reliability reached α = 0.876.

All coefficients exceeded the conventional acceptability threshold of 0.70, confirming the robustness of the instrument for assessing faculty attitudes toward the inclusion of students with PMD in higher education [66]. These results provide strong evidence of internal consistency and support the instrument’s application in institutional diagnostic and formative processes.

Similar levels of reliability have been reported in international studies validating the SACIE-R scale in higher education contexts [33,61]. This convergence reinforces the instrument’s utility not only for El Salvador but also for broader regional and international comparability, contributing to sustainable strategies in faculty development and inclusion monitoring.

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To examine construct validity and identify the latent structure of the SACIE-R scale, an EFA was conducted using the Maximum Likelihood extraction method with Varimax rotation. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded statistically significant results (χ2(66) = 1242.35, p < 0.001), and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.788, exceeding the minimum criterion of 0.70 [66]. These indices confirmed the suitability of the data for factor analysis.

Factor extraction followed the eigenvalue-greater-than-one rule, resulting in three latent factors that jointly explained 56.36% of the total variance, surpassing the 40% threshold typically considered acceptable in the social sciences [62,63]. Specifically, Factor 1 explained 26.45% of the variance (Emotional Disposition), Factor 2 accounted for 19.83% (Inclusive Commitment) and Factor 3 contributed 10.07% (Perception of Barriers). This factorial solution is consistent with previous SACIE-R validations in international higher education settings [33,61], strengthening the comparability of the Salvadoran results. These findings confirm the theoretical structure of the SACIE-R scale and its utility in operationalizing faculty attitudes as multidimensional constructs aligned with affective, cognitive, and behavioral components (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total Variance Explained.

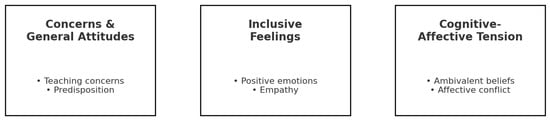

The rotated component matrix clarified the contribution of individual items, with only loadings ≥ 0.40 retained (see Table 2). The three-factor solution aligns with the tripartite theoretical model of attitudes, encompassing affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Factor 1 (Concerns and General Attitudes) grouped items related to stress, discomfort, or avoidance toward students with PMD. Factor 2 (Inclusive Feelings) included items expressing empathy, openness, and readiness for inclusion. Factor 3 (Cognitive–Affective Tension) comprised items reflecting insecurity, lack of preparation, or internal conflict regarding inclusion.

Table 2.

Rotated Factor Matrix.

This factorial structure reinforces the multidimensional nature of faculty attitudes toward inclusion, consistent with the tripartite model of affective, cognitive, and behavioral components [33,73]. These results also provide a foundation for subsequent CFA, which tested the stability of this three-factor solution.

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The CFA was conducted in R (lavaan 0.6–19), treating the 4-point Likert items as ordered categorical indicators. We used the robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV), with latent variances fixed to 1 (std.lv = TRUE), pairwise handling of missing data, and freely estimated factor covariances and thresholds. Reverse-worded items were recoded so that higher scores indicated more inclusive attitudes (P6 and P10) (Note on Item Labeling. For clarity in the presentation of the factorial analyses, each questionnaire item was assigned an abbreviated code: P1, P2, P3, …, Pn, corresponding to the numbering of the instrument. For example, P1 = Question 1, P2 = Question 2, and so forth. This labeling system was applied consistently across tables and figures, including the confirmatory factor analysis models (see Supplementary Table S2)).

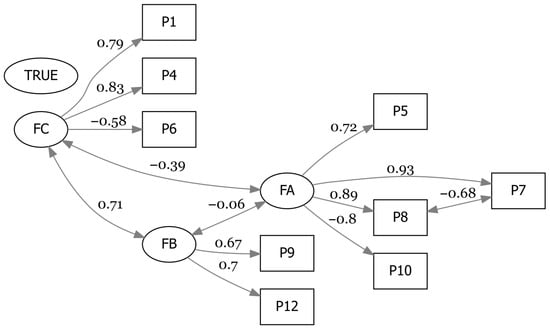

Guided by the EFA and the theoretical rationale of the instrument, we specified a three-factor structure: (a) Inclusive Feelings (P5, P7, P8, P10 reversed), capturing favorable beliefs and emotions toward inclusion; (b) Concerns and General Attitudes (P9, P12), reflecting support for integration practices; and (c) Cognitive–Affective Tension (P1, P4, P6 reversed), indexing ambivalence between willingness and perceived self-efficacy. Based on modification indices, a residual correlation between P7 and P8 was included within Inclusive Sentiments. This specification is referred to as the main model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis main model specification. Note. Estimates shown are standardized loadings; P6 and P10 are modeled as reversed indicators. Estimation used WLSMV with ordered-categorical indicators and latent variances fixed to 1. Three correlated latent factors with ordinal indicators (4-point Likert). Standardized loadings (λ) are displayed on paths; double-headed arrows denote latent covariances. Residual correlation specified between P7 and P8.

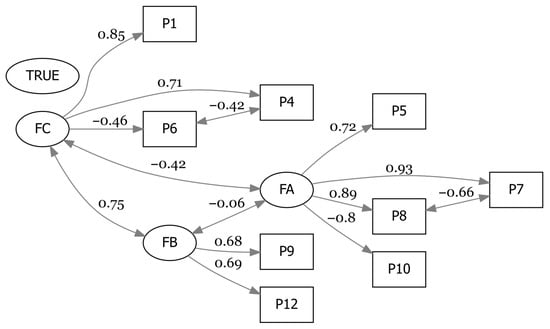

To test robustness, a sensitivity model was also estimated. This specification added a residual correlation (P4–P6) within Cognitive–Affective Tension, reflecting expected local dependence between performance expectations and perceived preparedness. The sensitivity model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis sensitivity model specification. Note. Estimates are standardized loadings; P6 and P10 were modeled as reversed indicators. Estimation used WLSMV with ordered-categorical indicators and latent variances fixed to 1. The model retains the same three-factor structure as the main specification, with residual correlations specified between P7 and P8 and additionally between P4 and P6. Standardized loadings (λ) are displayed on paths, and double-headed arrows represent latent covariances (see Supplementary Table S3).

Model evaluation relied on several fit indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, 90% CI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Table 3 reports the global fit indices for the main and sensitivity models. Table 4 summarizes the standardized factor loadings, while Table 5 presents composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing AVE values with squared latent correlations, reported in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis global fit indices for the main and sensitivity models (WLSMV).

Table 4.

Standardized factor loadings (λ) by factor and item for the main and sensitivity CFA models.

Table 5.

Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) by factor for the main and sensitivity models.

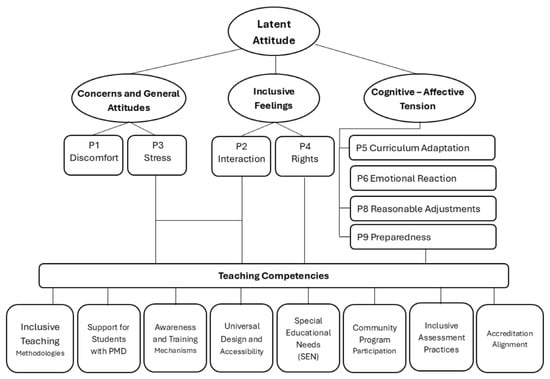

3.5. Empirical Model of Attitudinal Indicators

Drawing on the EFA results, an empirical model of attitudinal indicators was developed to explain how faculty attitudes influence the participation of students with PMD in higher education. The model comprises three latent dimensions: Concerns and General Attitudes, Inclusive Feelings, and Cognitive–Affective Tension regarding Reasonable Adjustments.

The framework is grounded in the social model of disability, which reframes disability as the outcome of systemic barriers embedded in institutional cultures. Using structuration theory, faculty attitudes—both explicit and implicit—are conceptualized as structuring agents that can reproduce or challenge inequality. From a cultural capital perspective, the model highlights “inclusive capital,” defined as the knowledge, values, and pedagogical dispositions required to support diverse student populations.

Furthermore, the model aligns with the sensitization phase of the attitude-change process, a critical stage that precedes the acquisition of inclusive competencies. This connection is supported by recent research on inclusive education [41,74,75,76,77,78].

Ten empirical indicators were derived from the SACIE-R scale and mapped to professional practices. These include inclusive teaching methodologies and tutoring support; awareness-raising initiatives, universal design, and technological accessibility; capacity to address special educational needs and implement reasonable adjustments; inclusive assessment and curriculum design; and alignment with accreditation and quality assurance frameworks.

In applied contexts, the model contributes both theoretically and practically by translating attitudinal inclusion into measurable dimensions relevant to institutional quality frameworks. Validated through descriptive, inferential, and confirmatory analyses, it can support institutional diagnostics, identify training needs, inform professional development, guide evaluation systems, and underpin the development of policies based on human rights and equity. Consistency with the ESG [79] and national policy guidelines reinforces its relevance, while its validation advances educational sustainability and aligns with international applications of the SACIE-R [33,61].

3.6. Differences by Sociodemographic Variables

Building on the validated three-factor structure of the SACIE-R scale confirmed through CFA, inferential analyses were conducted using Chi-square tests to examine potential attitudinal differences across faculty subgroups. The variables considered included age, sex, type of institution, and prior training in inclusive education. This procedure allowed us to test whether sociodemographic attributes influence faculty perceptions of inclusion within the Salvadoran higher education context.

Comparable subgroup analyses have been widely reported in international validations of the SACIE-R scale [33,61]. These studies highlight how personal and institutional characteristics shape readiness for inclusive teaching, reinforcing the need for sustained training policies that promote equitable and sustainable professional development opportunities for faculty.

3.6.1. Significant Associations by Variable

Statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) emerged across several sociodemographic groups, confirming the robustness of the validated three-factor model derived from the CFA. Age-related differences appeared in attitudes toward adapting the teaching–learning process (P6, p = 0.029) and in reported emotional discomfort (P8, p = 0.017), suggesting that pedagogical flexibility and emotional readiness vary across generations of faculty.

Sex differences were also evident. Faculty diverged in their responses regarding avoidance of contact with students with PMD (P3, p = 0.053), perceptions of infrastructure and technological adaptations (P4, p = 0.026), emotional discomfort (P8, p = 0.043), and difficulty overcoming first impressions (P10, p = 0.052). These results indicate that male and female faculty may experience disability inclusion through distinct emotional and cognitive pathways.

Institutional context and prior training further shaped attitudes. Faculty from different institutional types reported significant differences in perceptions of adaptations (P4, p = 0.023), workload concerns (P5, p = 0.039), integration of underperforming students (P9, p = 0.009), and teaching competence (P11, p = 0.011). Moreover, structured training in inclusive education was associated with more favorable attitudes toward integrating students with low performance (P9, p = 0.023).

These findings are consistent with international evidence showing that professional development enhances faculty preparedness for inclusion [33,71]. They reinforce the need for sustainable, long-term training policies in higher education that align with validated attitudinal models and contribute to internationally comparable benchmarks for inclusive practices.

3.6.2. Persistent Negative Attitudes

Although most subgroup differences reflected variations in the intensity rather than the direction of positive attitudes, some persistent negative patterns were evident within the CFA-validated model. Resistance to individualized academic programs (P12) appeared more frequently among faculty aged 25–29 and 55–59 (p = 0.009). Likewise, low teaching confidence (P11) was reported primarily by professors in public institutions (p = 0.011) and those without prior training (p = 0.509), with 63.6% expressing concerns about their competence. These findings suggest that limitations are linked more to gaps in professional preparedness than to outright rejection of inclusion.

To complement the Chi-square tests, effect sizes were calculated using Cramer’s V. Although several associations reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), most effect sizes were small to moderate (0.10–0.24). This indicates that contextual and demographic variables shape faculty attitudes in meaningful ways, but their influence remains modest.

Similar patterns have been reported in other Latin American contexts, where lack of training and institutional support—rather than negative predispositions—explain attitudinal barriers [71,72]. These convergent findings emphasize that sustainable improvements depend on systematic faculty development and institutional strategies aligned with inclusive policies.

3.6.3. Comparison by Contact with Students with Disabilities

Further analysis examined whether faculty attitudes differed according to prior contact with students with physical motor disabilities. Within the CFA-validated structure of the SACIE-R, no statistically significant differences emerged across the three factors. Positive responses in General Attitudes were nearly identical among faculty with (72.5%) and without contact (71.8%). Similarly, Inclusive Feelings exceeded 93% in both groups, while approximately 30% of responses in Concerns reflected anxiety or stress-related attitudes regardless of contact experience.

Item-level analysis, however, highlighted persistent challenges. Low teaching preparedness (P11) was reported by 68.9% of faculty with contact and 61.1% without. Other items—such as curriculum adaptation (P2), infrastructure and technological adjustments (P4), and individualized programs (P12)—also generated high concern in both groups. These patterns suggest that while inclusive discourse is widespread, its translation into confident and competent teaching practices remains limited.

Comparable findings have been reported internationally, where contact alone does not guarantee preparedness, and sustained professional development together with structural support are required to achieve genuine inclusion [33,80]. This underscores the importance of moving beyond exposure toward long-term training policies and institutional strategies that reinforce educational sustainability.

3.6.4. Implications

The persistence of attitudinal barriers—particularly regarding instructional adaptation, professional competence, and emotional readiness—reveals systemic gaps that hinder the translation of inclusive intentions into practice. These challenges are not unique to El Salvador, as similar patterns are observed across Latin America, where faculty training for inclusion remains limited or fragmented [71,72,81]. By validating these indicators through both EFA and CFA, this study provides a robust basis for understanding how such barriers are structured within higher education.

International research also confirms that positive attitudes alone are insufficient without structured professional development and institutional support. Faculty confidence and preparedness require ongoing training and organizational frameworks that normalize inclusive practices [33,80]. These findings underscore the need for interventions that address attitudes not only as individual traits but as outcomes shaped by systemic and institutional contexts.

Moving beyond awareness campaigns, policies must prioritize comprehensive and sustained faculty development [60]. Embedding inclusion-related criteria into quality assurance frameworks can enhance the participation of students with physical motor disabilities. Such actions are essential for strengthening governance and promoting educational sustainability across higher education in Latin America [12,28,61,82].

3.7. Representation of the Model

The empirically validated model of attitudinal indicators—originally identified through EFA and subsequently confirmed by CFA—is presented in Figure 3. This model captures the complexity of faculty attitudes toward the inclusion of students with PMD by grouping them into three latent dimensions.

Figure 3.

Validated Empirical Model of Faculty Attitudes Toward Inclusion of Students with PMD. Note. The model integrates three latent factors confirmed through CFA: Concerns and General Attitudes, Inclusive Feelings, and Cognitive–Affective Tension. Each factor clusters observable indicators from the SACIE-R scale, providing a framework for institutional diagnosis and pedagogical planning.

These factors are: (1) Concerns and General Attitudes, (2) Inclusive Feelings, and (3) Cognitive–Affective Tension. Together, they reflect the tripartite structure of attitudes—affective, cognitive, and behavioral—using observable indicators derived from the SACIE-R scale. The model provides a clear bridge between abstract constructs and measurable faculty competencies. By doing so, it enables more precise institutional diagnoses of attitudinal barriers and opportunities. This framework offers strategic value for higher education institutions. It supports planning, training, and pedagogical transformation, embedding inclusion into quality assurance processes and contributing to sustainable educational governance.

3.7.1. Factor-Level Structure

Factor 1: Concerns and General Attitudes. This factor comprises five indicators reflecting anxiety, stress, and general perceptions regarding inclusive practices. These include discomfort when teaching students with disabilities, concerns about workload, and skepticism about the feasibility of academic integration. Comparable findings have been reported in Latin America and internationally, where ambivalent predispositions persist as symbolic barriers to inclusion [33,61,71,72]. Confirmed in the CFA, this dimension underscores how attitudinal barriers remain a critical challenge for sustainable and equitable higher education.

Factor 2: Inclusive Feelings. The second factor comprises four indicators linked to empathy and openness toward inclusion. These reflect positive predispositions such as willingness to interact with students with physical motor disabilities and readiness to embrace diversity in teaching. Evidence from Chile shows that inclusive attitudes are closely connected to teachers’ self-efficacy and intentions to apply inclusive practices [25], while studies with pre-service teachers highlight affective dispositions as strong predictors of engagement [83]. This factor illustrates how emotional foundations can sustain institutional commitments to equity and diversity.

Factor 3: Cognitive-Affective Tension. The third factor consists of three indicators capturing perceived barriers, such as limited preparation, difficulties in accommodations, and doubts about teaching competence. This tension between inclusive ideals and practical readiness was also confirmed by the CFA and has been observed internationally, where contact alone does not ensure teacher confidence [80].

By mapping SACIE-R items to these professional indicators and validating them through both EFA and CFA, the model contributes to international discussions on inclusive attitudes. It reinforces its empirical robustness and offers a framework to inform sustainable faculty development policies in higher education.

3.7.2. Strategic Utility

The representation of the model has significant practical value for higher education institutions. Confirmed through both EFA and CFA, it provides a robust framework to assess faculty attitudes toward inclusion. First, it enables diagnostic assessments of attitudinal barriers, offering institutions a reliable tool to identify strengths and weaknesses in inclusive practices. Second, it informs the design of professional development programs that move beyond awareness campaigns toward sustainable and continuous faculty training.

Third, the model aligns with institutional quality assurance processes, including faculty evaluation, curriculum review, and accreditation mechanisms. By embedding inclusive education into these core strategies, universities can normalize inclusive practices and foster long-term cultural change. Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S6 reinforce this conceptual linkage between attitudes and professional performance, consistent with international standards promoted by the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) and the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) (A detailed mapping of questionnaire items, latent factors, inclusive teaching competencies, and institutional quality criteria is provided in Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 4.

Validated attitudinal indicators and teaching competencies for PMD inclusion. Note. Latent attitudes were modeled through three correlated factors: Concerns and General Attitudes, Inclusive Feelings, and Cognitive–Affective Tension. Indicators are derived from the SACIE-R items (P1–P12); for detailed item loadings, see Table 4 and Supplementary Table S6.

Drawing on attitude change models [84,85], the framework positions inclusive attitudes as both measurable and modifiable. This strategic perspective offers a practical roadmap for institutional transformation by enabling longitudinal monitoring of faculty development efforts. It also strengthens international comparability and supports evidence-based strategies that contribute to educational equity and sustainability for students with disabilities.

4. Discussion

This study provides robust evidence for a three-dimensional structure of university faculty attitudes in El Salvador regarding the inclusion of students with PMD. The identified dimensions—(1) Concerns and General Attitudes, (2) Inclusive Feelings, and (3) Cognitive–Affective Tension. Substantively, this structure clarifies where inclusive discourse translates into practice and where it stalls—pinpointing emotional discomfort, perceived workload, and self-efficacy gaps as the main leverage points for institutional change. This contribution extends prior international validations by specifying how attitudinal components operate in a Latin American context, adding policy-relevant nuance for faculty development and governance aligned with SDG 4.

The first dimension, Concerns and General Attitudes, reflects the persistence of latent resistance and symbolic barriers to inclusion. Faculty members reported discomfort, stress, and a perceived increase in workload when interacting with students with PMD. Consistent with previous research highlighting emotional discomfort and avoidance behaviors as covert forms of exclusion [24,25,26], these internalized tensions indicate that discursive normalization of inclusion does not necessarily lead to pedagogical transformation. Addressing these barriers requires sustainable professional development strategies that transform attitudes into concrete inclusive practices.

In contrast, the second dimension, Inclusive Feelings, captures positive emotional predispositions—such as empathy, recognition of rights, and support for integration. These attitudes align with international frameworks, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Sustainable Development Goal 4.5 on equitable access to education [11]. However, this normative alignment does not automatically translate into effective implementation of inclusive practices. A persistent gap between belief and action has been widely documented in Latin American universities, where policies exist but remain unevenly applied in classroom settings [1,3,19,36,43,44,45]. This gap underscores the need for institutional strategies that ensure inclusive feelings are transformed into sustainable pedagogical action.

The third dimension, Cognitive–Affective Tension, reveals a critical challenge: faculty insecurity about their ability to adequately support students with PMD. With 94.5% of respondents lacking formal training in inclusive education, these insecurities reflect not only personal limitations but also systemic deficits in professional development. Such findings resonate with broader regional evidence showing that insufficient pedagogical training perpetuates attitudinal inertia and constrains instructional innovation [86].

Beyond its practical implications, the identification of cognitive–affective tension represents a theoretical contribution that distinguishes this study from prior international validations of attitudinal instruments such as MAS or ATSI. While existing scales typically capture affective and cognitive predispositions separately, the emergence of this factor highlights the intertwined nature of emotions and perceived competence in teaching students with disabilities. This construct broadens the explanatory capacity of the tripartite attitude model by introducing a dimension especially relevant in contexts with limited training and institutional support, such as those found in many Latin American higher education systems. Its empirical confirmation through CFA strengthens its international comparability and underscores its value for advancing inclusive and sustainable educational policies.

The inferential analyses deepen these insights by identifying significant, although nuanced, relationships between sociodemographic variables and attitudinal responses. Differences in age, gender, institutional affiliation, and training background influenced perceptions and attitudes toward inclusion. Yet, most variations were associated with intensity rather than direction, confirming a generally favorable attitudinal climate tempered by contextual differences [54].

A particularly salient finding is the absence of significant differences between faculty members who reported contact with students with PMD and those who did not. This challenges the prevailing assumption that direct interaction functions as a protective factor against negative attitudes [58]. It suggests that contact, in isolation, may be insufficient to generate attitudinal change unless it is coupled with intentional reflection and structured professional development, reinforcing the need for sustainable faculty training strategies.

This finding underscores the need to reinterpret the role of “contact” within inclusive education frameworks. In the Salvadoran higher education context, interaction with students with PMD appears to normalize coexistence but does not translate into greater self-efficacy or pedagogical readiness. Attitudinal change seems contingent on reflective training opportunities, institutional mentoring, and sustained exposure linked to professional development programs. Without these complementary strategies, contact alone may reduce overt prejudice but fail to transform teaching practices into inclusive actions.

Recent research in Education Sciences highlights the complex interaction between attitudes, institutional cultures, and inclusive practices. For example, Lister et al. [87] show that accessibility and inclusion require a systemic approach across higher education institutions, not only individual faculty commitment. Similarly, Woodcock et al. [88] emphasize that teachers’ beliefs in inclusive education are strongly associated with their levels of self-efficacy, which directly influence classroom management and instructional strategies. Our findings reinforce this international evidence by demonstrating that attitudinal indicators among faculty are central predictors of disability inclusion in the Salvadoran higher education context. This alignment suggests that cultural and contextual differences notwithstanding, attitudinal constructs retain explanatory power across diverse educational systems.

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The empirical model proposed in this study transforms abstract constructs into measurable indicators aligned with inclusive teaching competencies and institutional quality frameworks. This operationalization represents a valuable contribution to the field by enabling HEIs to monitor inclusion practices, identify training gaps, and design targeted interventions grounded in human rights-based educational principles [35,36,89]. Beyond its psychometric value, the model functions as a strategic mechanism for institutional transformation embedding inclusion into actionable governance structures. By offering an empirically grounded framework, it facilitates international comparability and supports sustainable governance in higher education, positioning attitudinal indicators as core levers for advancing disability inclusion in line with global standards.

The validated empirical model offers higher education institutions in El Salvador—and potentially throughout Latin America—a strategic, evidence-based tool to identify and address attitudinal barriers to inclusion. By translating abstract dispositions into measurable and observable indicators, universities can move beyond declarative commitments toward actionable transformation of structures and teaching practices. In practical terms, the CFA-validated indicators equip educational leaders with a framework to:

- −

- Design and implement targeted faculty development programs on inclusive pedagogies.

- −

- Integrate inclusive competencies into teaching evaluation and promotion criteria.

- −

- Align accreditation processes with national and international standards such as ENQA and SDG 4.5.

- −

- Develop student support services tailored to the barriers identified through the model.

- −

- Support organizational change through data-driven policies that promote accountability and a culture of inclusion.

Table 6 summarizes these strategic implications, aligning attitudinal indicators with institutional policies to translating inclusive frameworks into sustainable institutional practice (A comprehensive overview of the strategic implications of attitudinal indicators—linking questionnaire items, latent factors, inclusive teaching competencies, and institutional quality criteria—is presented in Supplementary Table S7).

Table 6.

Strategic Implications of Attitudinal Indicators for Institutional Policy Implementation.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the advancement of inclusive education research by operationalizing faculty attitudes as a multidimensional construct. This integration of theory and empirical validation strengthens conceptual clarity and provides a replicable model for further inquiry. A central innovation is the identification of “cognitive–affective tension” as a distinct latent dimension, which expands the traditional tripartite model of attitudes. Unlike existing international instruments such as MAS and ATSI, this construct captures the interplay between emotions and self-perceived pedagogical competence. The inclusion of CFA validation further reinforces the theoretical robustness of this contribution. Overall, the model enhances the explanatory power of attitudinal research, particularly in Global South contexts where institutional resources and cultural understandings of disability diverge from those of the Global North.

4.1.1. Practical Implications and Contrast with General Attitudinal Scales

General measures such as MAS or ATSI provide robust estimates of global dispositions toward disability and inclusion, yet their interpretation is typically decoupled from faculty teaching competencies. This disconnect constrains their direct use in professional development planning and institutional policy cycles. Our faculty-specific model addresses this gap by operationalizing attitudes into indicators explicitly mapped to core higher-education teaching competencies, thereby turning attitudinal diagnostics into actionable levers for training and governance.

In practical terms, the Concerns & General Attitudes dimension aligns with ethical and legal compliance as well as institutional commitment; it is best addressed through concise, rights-based refreshers and policy onboarding, with quality assurance tracked via completion rates and pre–post knowledge checks. Inclusive Feelings maps onto inclusive pedagogy, communication, and classroom climate; it is strengthened through UDL-aligned micro-teaching and peer coaching, monitored by the uptake of accessible formats and student feedback on inclusion. Cognitive–Affective Tension relates to assessment practices and reasonable adjustments; it is targeted through assessment-redesign clinics and case-based mentoring, with progress evidenced by the adoption of alternative rubrics and documented accommodations.

By anchoring attitudinal scores to competency domains, program directors can prioritize modules for units with specific profiles, define competency-referenced KPIs (e.g., uptake of accessible materials, implementation of reasonable adjustments), and integrate results into policy instruments such as promotion criteria, PD requirements, and continuous improvement cycles. Thus, rather than functioning solely as a climate barometer, the instrument becomes a decision tool that directly informs training design and policy implementation in higher education.

4.1.2. Interpreting Generational Patterns and the Limits of “Mere Contact”

The age-related differences we observe in attitudes toward adapting the teaching process and in reported emotional discomfort are consistent with cohort effects rather than age per se. Faculty who completed their initial teacher training prior to the main-streaming of disability-inclusive frameworks may have had fewer opportunities to acquire inclusive pedagogy (e.g., UDL-aligned course design, assessment with reasonable adjustments) during foundational preparation. Over time, career-long exposure to inclusion discourse and targeted professional development tends to build self-efficacy for inclusive practices; where such exposure is uneven, cognitive–affective tension can persist, particularly in domains—like assessment redesign—perceived as high-stakes or technically demanding. These mechanisms help explain why generational contrasts emerge in our attitudinal indicators, and they suggest that differences are malleable through structured training and supportive organizational climates rather than fixed traits of age.

Equally important is our finding that no significant attitudinal differences were detected between faculty who reported contact with students with PMD and those who did not. This result challenges a common assumption that “contact” is uniformly beneficial. In higher education, contact often occurs under unstructured, time-pressured, or asymmetrical conditions (e.g., ad hoc accommodation requests late in the term, limited guidance on legal/ethical obligations, or unclear channels for support). Under such circumstances, contact can be superficial or even experienced as a demand without resources, which is unlikely to reduce discomfort or to strengthen inclusive orientations. What appears to matter is how contact is established and scaffolded: collaborative interactions around shared learning goals, equal-status roles (e.g., co-design of adjustments), and explicit institutional endorsement and support tend to transform contact from a stressor into a source of pedagogical growth.

Building on these insights, we advance a testable conceptual model in which: (a) contact quality—operationalized by the presence of collaborative tasks, equal-status engagement, and clear goals—mediates the link between contact frequency and attitudinal change; (b) the institutional support framework—policies, specialized services, training pathways, and accessible resources—both facilitates high-quality contact and moderates its effects on attitudes; and (c) inclusive teaching self-efficacy acts as a proximal mediator connecting contact quality and support to lower cognitive–affective tension and greater willingness to adapt teaching. Future studies could operationalize these constructs with dedicated scales and examine moderated mediation (e.g., WLSMV-based SEM), including invariance by cohorts to distinguish period effects (policy maturation) from cohort effects (training era).

Practically, these interpretations point to cohort-sensitive faculty development (onboarding refreshers for ethical/legal alignment; UDL micro-teaching and peer coaching to consolidate inclusive pedagogy; assessment redesign clinics for high-discomfort areas) and to policy-linked KPIs (e.g., uptake of accessible materials, documented accommodations) that ensure contact is embedded in a resourced framework rather than left to individual improvisation. Generational patterns are plausibly explained by differential opportunities for building competence and confidence, and the absence of a raw “contact effect” underscores that contact must be structured and institutionally supported to meaningfully shift attitudes.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although the model demonstrated good overall fit indices and acceptable levels of composite reliability for two of the factors, the discriminant validity analysis using the Fornell–Larcker criterion revealed a limitation. Specifically, the squared correlation between the “Concerns and General Attitudes” and “Cognitive–Affective Tension” factors exceeded the average variance extracted (AVE) of the former, indicating a high degree of overlap. This result suggests that, in practice, faculty members’ general attitudes toward disability and their perceived cognitive–affective tensions are closely intertwined. Rather than undermining the model, this overlap reflects the reality that beliefs, concerns, and self-efficacy perceptions often co-occur in shaping inclusive teaching practices. Nevertheless, future studies could test a second-order or bifactor structure to capture this shared variance while retaining the theoretical distinctions among the three dimensions.

The SACIE-R scale presents theoretical limitations that merit critical reflection. Originally developed in Spain and later adapted in Latin America, it carries assumptions rooted in Western epistemologies that may not fully capture local understandings of disability, pedagogy, or institutional dynamics in Central America. In contexts marked by religious, collectivist, or charity-based traditions, the construct of “inclusion” may be interpreted differently, affecting how respondents perceive and react to survey items.

Another limitation concerns the absence of intersectional perspectives. The SACIE-R does not explicitly incorporate variables such as ethnicity, rural–urban divides, or linguistic diversity, all of which can significantly shape attitudinal dispositions. Future iterations of the model should consider localized validation studies and include contextually grounded constructs to strengthen regional applicability and cultural sensitivity. Beyond these constraints, the validated model represents a strategic advancement in inclusive education research. Its adaptation to the Salvadoran context bridges theoretical constructs with institutional realities, offering an operationalizable framework for faculty self-assessment and professional development.

Unlike other instruments that may overlook the multidimensional nature of attitudes in Global South settings, this model combines psychometric rigor with contextual relevance. It thus holds promise not only for academic research but also for accreditation processes, sustainable institutional governance, and the design of equity-driven training programs. Future applications may include longitudinal tracking, mixed-methods triangulation, and cross-national comparisons to further consolidate its international and sustainable impact. One limitation that deserves deeper discussion is the potential influence of cultural and regional biases. While instruments such as SACIE-R and related scales have demonstrated validity in Europe and Australia, their transferability to Latin America may involve cultural nuances [15,30].

In Central America, attitudes toward disability are shaped by socio-political conditions, limited institutional resources, and persistent stigmatization. These factors may not be fully captured by tools originally developed in the Global North. Addressing this gap in future validation studies would enhance cross-cultural comparability and theoretical robustness. Our findings, supported by both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, contribute to this debate by showing that validated attitudinal indicators can be recalibrated to reflect local realities. As summarized in Table S7, the model not only advances theoretical understanding but also provides a roadmap for institutional action consistent with international frameworks on inclusive education. This dual contribution strengthens its relevance for both research and practice.

Beyond statistical validation, the results carry strategic implications for higher education policy. As Gámez-Calvo et al. [59] argue, attitudes toward disability among future professionals are strongly shaped by curricular experiences and institutional environments. In this sense, universities in El Salvador should not only measure inclusion attitudes but also embed them into faculty development programs, accreditation standards, and institutional quality indicators. Such initiatives align with international recommendations for integrating inclusion into higher education governance, ensuring that attitudinal change is sustained through concrete institutional policies.

While the study presents robust statistical and conceptual findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to private universities in El Salvador, which may restrict generalizability to public institutions or other national contexts. Second, the study focused exclusively on physical motor disabilities, thereby excluding variations in attitudes toward other impairment categories such as sensory, intellectual, or psychosocial disabilities. Third, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential social desirability bias.

Future research should therefore:

- −

- Apply the model across public and diverse institutional settings, both within and beyond El Salvador.

- −

- Extend the scope to include multiple disability types to capture the full spectrum of faculty attitudes.

- −

- Conduct longitudinal studies to track attitudinal changes following professional development and institutional reforms.

Although the model was developed for PMD, its theoretical underpinnings—the tripartite attitude model and the social model of disability—are not exclusive to this group. With contextual revalidation, the framework can be adapted to sensory, intellectual, or psychosocial disabilities. This delimitation reinforces methodological rigor while opening a pathway for comprehensive, comparative analyses that promote sustainable inclusive transformation in higher education.

5. Conclusions

This study offers a validated empirical model of attitudinal indicators for assessing university faculty predispositions toward the inclusion of students with PMD in Salvadoran higher education. Grounded in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA), the model identifies three latent dimensions—Concerns and General Attitudes, Inclusive Feelings, and Cognitive–Affective Tension—that together explain 56.36% of the total variance.

This tripartite structure provides a nuanced, multidimensional framework to understand faculty attitudes beyond declarative statements, enabling more precise institutional diagnosis and targeted interventions. Findings reveal that while affective endorsement of inclusive education is relatively widespread, critical challenges persist. Faculty members express concerns about preparedness, workload, and the feasibility of reasonable accommodations. The fact that over 94% of respondents lacked formal training in inclusive education underscores a significant professional development gap and highlights the symbolic and practical barriers that continue to hinder implementation of inclusive practices.

The proposed model contributes to the operationalization of “inclusive attitudes” by transforming them into measurable and actionable indicators aligned with professional teaching competencies. These indicators hold practical utility for multiple stakeholders: they can guide faculty development programs, inform curriculum redesign processes, support accreditation and quality assurance frameworks, and track alignment with global standards such as SDG 4.5 and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Importantly, the CFA validation reinforces the robustness of the model, increasing its credibility for institutional and cross-national applications.

Although sociodemographic differences were not pronounced, the study points to the need for context-sensitive strategies that consider institutional affiliations, training opportunities, and disciplinary cultures. The minimal attitudinal impact of direct contact with students with disabilities further suggests that exposure alone is insufficient to foster change. Instead, sustainable transformation requires structured reflection, institutional commitment, and pedagogical reorientation rooted in inclusive values.

By bridging abstract constructs and teaching realities, this research advances inclusive higher education not only in El Salvador but also across the Global South. The model offers a replicable framework for assessing and strengthening inclusion policies, contributing directly to SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), and SDG 16 (inclusive institutions).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210379/s1, Tables S1–S7: Table S1. Comparative table of attitudinal measurement instruments used in inclusive education research; Table S2. Items of the adapted SACIE-R scale for faculty attitudes toward the inclusion of students with physical motor disabilities; Table S3. Model specification decisions and rationale applied in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA); Table S4. Latent factor correlations for the main and sensitivity CFA models; Table S5. Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity indices across models; Table S6. Relationship between latent factors, questionnaire items, inclusive teaching competencies, and higher education quality criteria and Table S7. Strategic implications of attitudinal indicators for disability inclusion in higher education.

Author Contributions

C.A.E.M.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision; M.I.F.P.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the coordinating university (CEI-USAM-2024-030, 2024-01-25).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional data protection policies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data have been anonymized to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Filippou, K.; Acquah, E.O.; Bengs, A. Inclusive policies and practices in higher education: A systematic literature review. Rev. Educ. 2025, 13, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, E.L.; Swartz, L. Integration into higher education: Experiences of disabled students in South Africa. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawire, A.W.; Musungu, S.; Kioupi, V.; Nzuve, F.; Giannopoulos, G. Student and staff views on inclusion and inclusive education in a Global South and a Global North higher education institution. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Juárez, A.; González-Castellano, N. Understanding professors’ and students with disabilities’ perceptions of inclusive higher education: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2024, 39, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]