Abstract

Despite heightened sustainability agendas, green purchase behavior (GPB) remains uneven. This study develops a motive–mechanism account that distinguishes personal (self-regarding) and civic (other-regarding) motivation and specifies how these parallel motives operate through a dual-barrier/relational-enabler layer. Using survey data from urban consumers in China (n = 420) and structural equation modeling with bias-corrected bootstrapped indirect effects, we test a dual-path mediation model in which perceived cost and perceived risk function as inhibitory mechanisms, while social capital operates as a relational amplifier. Results indicate that both motivations positively predict GPB; cost and risk suppress GPB; and social capital facilitates GPB. Indirect effects via all three mediators are significant, yet direct paths from both motivations to GPB remain, indicating partial mediation. Two regularities are noteworthy: a pattern of motivational symmetry, whereby personal and civic motives exhibit comparable direct associations with behavior, and an attenuated risk pathway relative to cost, suggesting affordability—more than uncertainty—constrains adoption in the observed market context. Theoretically, the findings integrate TPB–VBN insights into a dual-motive, dual-barrier, relational-enabler framework that positions social capital as a conversion-efficiency multiplier and clarifies scope conditions under which each pathway dominates. Practically, the results prioritize interventions that lower out-of-pocket costs, reduce the salience of uncertainty, and leverage community trust and peer visibility.

1. Introduction

The urgency of mitigating environmental degradation has made green consumption a focal point of global sustainability agendas, yet actual green purchase behavior (GPB) remains uneven across societies. A substantial literature has examined cognitive, normative, and contextual antecedents of GPB [1,2], but much of it implicitly presumes that pro-environmental behavior flows primarily from altruistic values or ecological concern. This view overlooks a critical duality: the coexistence of self-interested motivations (e.g., health consciousness, financial efficiency, status signaling) and civic motivations (e.g., ethical commitment, environmental stewardship, moral identity) in shaping sustainable consumption. Consumers often buy “green” not only to help the planet but also to maintain self-image, enhance wellbeing, or gain reputational benefits [1,2,3]. We use civic motivation as the operational construct; references to civic duty are treated as conceptually equivalent.

Context: China’s green consumption snapshot. China offers a salient setting where policy signals and market adoption are both pronounced. New-energy vehicles (NEVs) reached 50.1% of passenger-car retail in H1 2025 and 54.7% in July; during 1–24 August, retail penetration stood at 56.6% [4,5]. The national trade-in program lifted 2024 retail sales of home appliances and audio-visual equipment to CNY 1.03 trillion and benefited over 37 million consumers [5]. Clean-energy industries contributed >10% of China’s 2024 GDP—about CNY 13.6 trillion (≈USD 1.9 trillion)—underscoring the structural weight of green supply chains [6].

Crucially, existing research has not sufficiently unpacked how dual motivations translate into behavioral outcomes. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [7] and Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory [8] offer robust explanatory power for green consumption, yet often operationalize “motivation” as unitary, blurring the strategic rationality embedded in egoistic choices and the moral intentionality underlying civic behavior [9,10]. We argue that motivation-to-behavior translation is neither direct nor uniform; rather, it is conditioned by psychological frictions and social resources that amplify or inhibit motive effects. In particular, perceived cost and perceived risk constitute proximal cognitive barriers that can stall behavior despite good intentions [11,12], whereas social capital—trust, network ties, peer support, and institutional linkage—functions as a relational enabler through which civic or reputational motives become actionable [13,14].

Building on these insights, we position personal (self-interested) and civic motivations as structurally distinct yet behaviorally intertwined antecedents within a dual-path mediation framework. Conceptually, we advance an instrumental–deontic view: self-interest primarily operates through instrumental suppression of cost and risk, whereas civic motivation primarily operates through deontic commitment converted into action by relational resources (social capital). We further theorize a motivational interplay whereby civic motivation amplifies the behavioral yield of self-interest by aligning private benefits with collective welfare in socially embedded markets [9,15]. This integrative lens moves beyond the reductive “altruism versus egoism” dichotomy and offers a more nuanced account of the motivational architecture underlying green consumption. Although prior work has emphasized individual-level values [16,17] few studies jointly consider the psychological constraints and social enablers that moderate motivation–GPB links in emerging economies such as China, where collectivist norms, risk considerations, and sustainability campaigns intersect [18,19]. We use civic motivation as the operational construct and treat the title term civic duty as its conceptual equivalent. Consistent with deontic accounts of pro-environmental behavior [7,8] civic motivation denotes an internalized obligation toward collective environmental outcomes (e.g., responsibility, stewardship, moral identity). All measurement and modeling therefore employ the label civic motivation.

Study aim and framework. Addressing these gaps, we develop and empirically test a model in which personal and civic motivations affect GPB via three mediators: perceived cost, perceived risk, and social capital. We also test motivational interplay (civic × personal) to capture potential reinforcement between private and collective orientations.

Contributions. This study (i) enriches the motivational taxonomy by conceptualizing GPB as a contested space between self-benefit and societal obligation; (ii) offers a mechanistic account by integrating barrier-based (cost, risk) and resource-based (social capital) mediators that transform—or disrupt—motivations into action; and (iii) provides culturally grounded insights from Chinese urban consumers, with implications for other fast-developing societies grappling with behavioral inertia in sustainable transitions. The remainder proceeds as follows: Section 2 develops hypotheses; Section 3 details methods; Section 4 reports results; Section 5 discusses implications and context; Section 6 presents limitations and future research; Section 7 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Research on green purchase behavior converges on three strands directly pertinent to this study. First, beyond general pro-environmental attitudes, two motive families co-exist in consumer decisions: an instrumental orientation centered on private utility (price–value, effort, performance) and a deontic orientation grounded in civic responsibility toward collective outcomes [7,8,16,17]. Second, at the point of purchase, proximal frictions—notably perceived cost and perceived risk—frequently attenuate intention–action links, whereas relational resources captured by social capital help convert motives into behavior through trusted information and peer endorsement [11,12]. Third, in urban China, policy signals and market infrastructures interact with community networks, shaping the salience of these mechanisms. This integrated background motivates our focus on how personal and civic motivations relate to GPB through perceived cost, perceived risk, and social capital within this context.

2.1. Motivational Foundations in Green Consumption Research

The motivation to engage in green consumption has long been conceptualized as a tension between self-interest and moral concern. Early environmental psychology and sustainability research largely adopted a dualistic view, distinguishing between egoistic values, which prioritize personal gain, and altruistic values, which emphasize concern for others and the environment [8,20]. This distinction served as the foundation for widely cited frameworks such as the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory and the Value-Attitude-Behavior (VAB) model, both of which assume that values are relatively stable internal drivers of pro-environmental behavior. In this study, self-interest is construed as an instrumental utility orientation—sensitivity to monetary and non-monetary trade-offs in purchase decisions—whereas civic motivation denotes a deontic obligation orientation toward collective environmental outcomes. The two antecedents are conceptually distinct rather than mutually exclusive and are modeled as separate reflective constructs. The mediators capture proximal purchase-threshold processes: perceived cost (price and effort/switching frictions) and perceived risk (performance, durability, after-sales uncertainty) act as suppressors of intention–behavior translation, while social capital—trusted information and peer support—functions as a relational enabler. These delineations clarify construct roles and explain why the framework focuses on near-behavior filters rather than upstream norms/values already embedded in the motivational constructs.

However, this binary classification has increasingly been questioned. Contemporary studies point to a more hybridized and context-sensitive pattern of motivation, in which moral and material logics intersect rather than oppose one another. For instance, Hasni et al. [2] argue that virtue signaling—often seen as an altruistic behavior—frequently operates as a means of reputational self-enhancement, blending social approval with private benefit. Similarly, Chen et al. [1] show that symbolic and functional benefits jointly mediate the influence of egoistic motives on green purchasing decisions, highlighting the instrumental logic that underlies supposedly value-driven acts.

To move beyond these limitations, this study adopts a behaviorally grounded framework that distinguishes between personal motivations and civic motivations. Personal motivations refer to self-oriented incentives such as health protection, cost-efficiency, or social recognition. Civic motivations, in contrast, represent collective-oriented drivers like environmental concern, community welfare, or perceived civic duty [9,15]. This typology enables a more realistic mapping of how green behavior is rationalized and enacted in diverse cultural and market environments.

In the Chinese context, where moral traditions, state-led ecological campaigns, and pragmatic market forces converge, this distinction is particularly relevant. Consumers often navigate between collectivist ideals and individual utility, making personal and civic motivations co-present and at times overlapping [18,21]. This study adopts this dual motivational lens as the foundation for exploring how green consumption decisions emerge under competing pressures.

2.2. Cultural Context and the Ambiguity of Motivation

Much of the sustainability literature implicitly treats motivational constructs as universal. Yet, growing cross-cultural evidence suggests that the meaning, weight, and interaction of motivations vary considerably across societies. In collectivist cultures like China, personal choices are often embedded within relational responsibilities, face-saving concerns, and social expectations, all of which influence how and why individuals engage in green behaviors [16,18].

For instance, Gong et al. [21] show that Chinese adolescents’ environmental actions are significantly shaped by intergenerational modeling, indicating that motivations are not purely internal but socially transmitted. Similarly, Zhao and Furuoka [13] demonstrate that social capital heterogeneity—such as who is present and watching—can reframe the perceived meaning of green behavior in digital settings like livestream shopping.

In such contexts, the boundary between “self-interested” and “other-oriented” behavior becomes blurred. For example, purchasing green products to protect one’s family health may simultaneously fulfill a civic narrative of environmentalism. Therefore, instead of assuming motivational purity, this study recognizes green motivations as socially constructed, context-dependent, and sometimes strategic [22,23].

By embedding the personal–civic distinction within a culturally informed framework, this study challenges the Western-centric assumptions that often underlie motivation theories in sustainability research. It further argues that understanding motivation requires attention not only to individual traits, but to normative environments, institutional messaging, and relational cues that structure consumer decision-making.

2.3. Theoretical Integration: TPB and VBN Models in Sustainability Research

Theoretical explanations of green behavior have largely centered on two dominant models: the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [7] and the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory. TPB conceptualizes behavior as a function of behavioral intention, which is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. It is particularly useful in operationalizing behavior and predicting the influence of attitudes under constrained decision environments [24,25].

VBN, by contrast, emphasizes internalized values and moral norms as the antecedents of pro-environmental action. It is better suited to explain value-driven behavior, particularly where consumers act on biospheric concern or ethical principles [26,27]. However, each model has limitations: TPB has been critiqued for ignoring distal motivations and over-relying on rational choice assumptions, while VBN often downplays real-world constraints like affordability and trust [9,11].

Recognizing their complementarity, recent work has attempted to integrate TPB and VBN to model both proximal predictors and distal values [28]. Yet these integrations often overlook how different motivational types—such as personal vs. civic—operate through different mechanisms within these frameworks. This study contributes to the literature by mapping personal motivations onto TPB-related constructs (e.g., cost, risk), and civic motivations onto VBN constructs (e.g., moral commitment, social capital), thus capturing how multiple logics of action interact within a single behavioral system.

2.4. Perceived Barriers: Cost and Risk as Cognitive Constraints

Numerous studies point to a persistent gap between environmental attitudes and actual behavior. One reason for this discrepancy lies in perceived barriers, particularly cost and risk, which undermine the conversion of intention into action [11,29]. These barriers—conceptually related to TPB’s perceived behavioral control—serve as friction points in the decision process. Perceived cost includes both objective price premiums and subjective resource concerns such as time and effort. Perceived risk involves uncertainties about product reliability, credibility, and potential social disapproval. Both are particularly salient in developing contexts where consumers face information asymmetry, low brand trust, and weak institutional safeguards [30].

Interestingly, motivations modulate how these barriers are experienced. Evidence suggests that personally motivated consumers—who focus on individual utility—are more deterred by cost and risk, while civically motivated individuals may discount these barriers due to moral framing or social obligation [2,9]. Despite this, few studies explicitly test these differential effects. This research incorporates cost and risk as parallel mediators, capturing how internal motivation is filtered through individual-level cognitive constraints.

2.5. Social Capital as a Relational Enabler

In contrast to cost and risk, social capital has been shown to facilitate green behavior by embedding individuals in networks of trust, reciprocity, and shared norms [31]. These relational structures reduce risk perception, enable behavioral diffusion, and enhance environmental efficacy, especially in collectivist or low-institutional-trust settings [13,32].

Empirical findings affirm this. Sun et al. [14] found that participation in community-based green renovation was strongly predicted by neighborhood trust. Cheung et al. [33] show that influencer–follower dynamics in social media contexts can transform passive interest into actual green behavior, particularly when relational credibility is high.

Civic motivations are especially sensitive to social capital effects, as community belonging and public accountability reinforce moral intentions. Personal motivations may also be enhanced through social pathways, such as when green behavior is validated or rewarded by peers. Accordingly, this study theorizes social capital as a social-relational mediator, distinct from the internal cognitive barriers previously discussed.

2.6. Synthesis and Research Contribution

Collectively, the literature reviewed highlights the complex interplay between motivational types, psychological barriers, and social enablers in shaping green consumption. Yet several theoretical gaps remain. First, most models treat motivation as unidimensional and culturally neutral, neglecting context-sensitive distinctions such as the personal–civic divide. Second, perceived cost and risk are typically treated as covariates rather than integrated mediating mechanisms. Third, social capital is often relegated to a background variable, rather than theorized as a dynamic force in behavioral formation.

This study advances an instrumental–deontic dual-process account of green consumption that extends TPB/VBN rather than restating them. Conceptually, we (i) differentiate motivational pathways by mapping self-interest to an instrumental channel operating through cost/risk suppression, and civic motivation (=civic duty) to a deontic channel converted into behavior via social capital; (ii) reposition social capital from a background correlate to a conversion-efficiency amplifier that turns moralized concern into executable action; and (iii) specify a cross-motive interplay whereby civic motivation moderates (amplifies) the self-interest → GPB path. This framework explicitly links behavioral-economics rationality (cost–risk calculus) with socio-political morality (collective obligation), explaining why and how the two drivers operate together rather than in parallel. Empirically, we estimate both dual mediations and the moderation within a single SEM, enabling comparative effect sizing of the instrumental and deontic channels and establishing a distinctive theoretical contribution beyond descriptive or confirmatory applications of TPB/VBN.

To engage more fully with broader sustainability and behavioral theories, we treat policy and market infrastructures as boundary conditions that shape motivation–behavior links. Price incentives, eco-labels and warranty/assurance schemes, and community-level implementation arrangements can lower perceived cost, compress perceived risk, and enable relational support, conditioning both the instrumental path (cost/risk) and the deontic path (social embeddedness). In parallel, we differentiate social capital into bonding, bridging, and linking facets and align them with our mechanisms: bonding is associated with peer endorsement and normative support, bridging with cross-group information that tempers uncertainty, and linking with access to programs and institutional assurances that attenuate cost [13,31,32]. Framed this way, personal and civic motivations operate within institutional opportunity structures rather than in isolation, consistent with behavioral foundations in TPB/VBN while attentive to contextual contingencies [7,8,34,35].

3. Theoretical Framework of the Study

3.1. Personal and Civic Motivations as Dual Drivers of Green Purchasing

Green purchasing behavior is not monolithically driven by altruistic or ecological concern. Rather, individuals are influenced by both egoistic (personal) and normative (civic) motivations, which operate through distinct psychological mechanisms. Personal motivation stems from self-regarding considerations, such as health protection and economic benefit. According to Cognitive Appraisal Theory, individuals evaluate potential actions based on their personal relevance and expected outcomes [36]. In the context of green consumption, when a product is seen as safer (e.g., organic food, non-toxic cleaning agents) or more economical (e.g., energy-efficient appliances), it elicits a favorable appraisal, thereby enhancing purchase intention.

Empirical studies support this link. For example, Tan et al. [30] found that consumers in polluted urban environments were significantly more likely to purchase green products when they perceived tangible health advantages. Likewise, Chwialkowska & Flicinska—Turkiewicz [29] demonstrated that cost-savings expectations mediated the relationship between economic concern and green purchasing.

Civic motivation, on the other hand, reflects internalized social norms and a sense of duty toward environmental and social welfare. Drawing on Schwartz’s Norm Activation Model (NAM), such motivation arises when individuals are aware of environmental consequences and feel a moral obligation to act [23]. Civic-oriented consumers tend to evaluate green purchases not by personal gain, but by the congruence with internalized values and identity. In this light, civic motivation is often more resilient to market fluctuations, though it may still be undermined by structural barriers such as high cost or low availability [33].

Therefore, we propose:

H1a:

Personal motivation positively influences green purchasing behavior.

H1b:

Civic motivation positively influences green purchasing behavior.

3.2. The Inhibiting Role of Perceived Cost and Perceived Risk

Even strong motivations do not always translate into behavior due to the presence of psychological or structural barriers, notably perceived cost and perceived risk. According to Prospect Theory [37] individuals are loss-averse and tend to overweight potential losses relative to gains. When consumers perceive green products as expensive or financially uncertain, the psychological cost may outweigh the perceived benefit, even if the long-term utility is favorable.

For personally motivated consumers, high cost contradicts the expectation of utility maximization, leading to dissonance and behavioral inhibition. For civic-motivated consumers, the cost may be psychologically reframed as a social investment; however, if perceived as unreasonably high, it still creates friction in actual behavior. Perceived risk in green consumption can be functional (e.g., doubts about product performance), psychological (e.g., brand unfamiliarity), or social (e.g., fear of judgment if outcomes are poor). From a TPB extension perspective, perceived behavioral control is reduced when risk perception is high, thus weakening intention strength. Research by Hasni et al. [2] confirms that risk aversion is a key inhibitor in green purchase decisions, especially among first-time buyers or low-involvement consumers.

Thus, we propose:

H2a:

Personal motivation negatively influences perceived cost.

H2b:

Personal motivation negatively influences perceived risk.

H2c:

Civic motivation negatively influences perceived cost.

H2d:

Civic motivation negatively influences perceived risk.

3.3. Barrier-to-Behavior Pathways: Cost and Risk as Negative Predictors

Although motivations spark interest, perceived cost and risk serve as gatekeepers. From the Means-End Chain Theory, we understand that consumers assess not just the end goals (health, social good) but also the means to achieve them. When the “means”—represented here by cost and risk—appear unattractive, the pathway from motivation to action is blocked.

Perceived cost reduces behavior by amplifying the perception of sacrifice, regardless of long-term gain. Perceived risk introduces uncertainty, which can dominate decision-making through the ambiguity aversion heuristic [38], especially when product claims are unverifiable or overpromised.

Accordingly:

H3a:

Perceived cost negatively influences green purchasing behavior.

H3b:

Perceived risk negatively influences green purchasing behavior.

3.4. Mediation Mechanisms: Psychological Filters Between Motives and Action

Motivation-behavior relationships are rarely direct. They are filtered through psychological appraisals of the environment. In this study, we conceptualize perceived cost and perceived risk as two key mediators that determine whether motivation leads to green action.

Health-and finance-conscious consumers are particularly sensitive to pricing and performance credibility. If their evaluations indicate that a green product is overpriced or uncertain in benefit, even strong personal motivation may not lead to behavior.

Although civic-oriented consumers are more tolerant of cost and risk, their behavior is not immune to these concerns. When they perceive green consumption as ineffective or merely symbolic (“token actions”), their willingness to act is compromised, revealing the limits of value alignment in real-world settings [24].

Therefore:

H4a:

Perceived cost mediates the relationship between personal motivation and green purchasing behavior.

H4b:

Perceived cost mediates the relationship between civic motivation and green purchasing behavior.

H4c:

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between personal motivation and green purchasing behavior.

H4d:

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between civic motivation and green purchasing behavior.

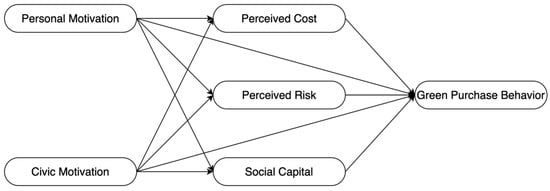

The research hypotheses are summarized in the research conceptual framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The research conceptual framework.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design, Population, and Sample

This study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design to empirically examine the relationships among Personal Motivation, Civic Motivation, Perceived Cost, Perceived Risk, Social Capital, and Green Purchase Behavior (GPB). The cross-sectional approach is particularly suitable for capturing attitudinal and behavioral patterns at a single point in time and is consistent with recent SSCI-indexed green consumption studies employing structural equation modeling [10,33,39]. The target population comprised Chinese consumers residing in urban areas, as they are more frequently exposed to sustainability campaigns, marketized green products, and public discourse surrounding environmental responsibility. Data were collected through Questionnaire Star (Wenjuanxing), a widely used online platform in China for academic research in sustainable consumption and service management.

We adopted a stratified quota sampling design using a national online consumer panel to recruit urban residents in mainland China (n = 420). Quotas were specified a priori for city tier, age, and gender to secure heterogeneity across key strata, and fieldwork was monitored to align achieved shares with planned targets. This design is appropriate for our aim of testing structural relations among constructs rather than producing population estimates. Because the sample is non-probability, we treat external generalizability as limited to comparable urban consumers and benchmark major marginals against standard urban demographic profiles to contextualize representativeness.

4.2. Measures and Instrument Development

All constructs in this study were measured using established multi-item scales on a five-point Likert format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). These scales were directly adopted from widely validated instruments in the extant literature to ensure theoretical soundness, measurement reliability, and cross-study comparability. Specifically, Personal Motivation was measured using items from Schlegelmilch et al. [40], capturing self-oriented drivers such as health, resource saving, and practical utility; Civic Motivation was assessed through items developed by Gupta and Ogden [41], reflecting moral obligation, environmental responsibility, and commitment to social responsibility; Perceived Cost was measured using Dodds et al.’s [42] price perception scale, emphasizing affordability and cost-related barriers; Perceived Risk was captured using Featherman and Pavlou’s [43] instrument, covering concerns regarding authenticity, performance uncertainty, and expectation mismatch; Social Capital was measured with Dinnie et al.’s [44] items, reflecting social trust, recognition, and the influence of peer norms; and Green Purchase Behavior was operationalized using the consumer eco-behavior scale developed by Haws et al. [45], which focuses on actual purchase prioritization and eco-friendly product choices. The complete questionnaire instrument is provided in Appendix A.

To ensure semantic equivalence in the Chinese context, the questionnaire underwent translation and back-translation following cross-cultural adaptation guidelines in sustainable consumption research [46,47]. Prior to large-scale administration, the instrument was pretested with two pilot samples (n = 30; n = 38) to refine wording, confirm factor structure, and assess reliability. Descriptive statistics, normality assessment, and reliability indicators for all constructs are reported in Table 1. Mean values and standard deviations fell within acceptable ranges; skewness and kurtosis met conventional thresholds (|skew| < 2, |kurtosis| < 7 [48,49]. Cronbach’s α exceeded 0.80 for all constructs (range = 0.811–0.844), indicating strong internal consistency [49,50]. Composite reliability (CR) values were ≥0.70 and average variance extracted (AVE) values were ≥0.50, supporting convergent validity [51,52]. These results establish the psychometric soundness of the measures and their suitability for subsequent confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Normality Assessment, and Reliability Analysis of Constructs.

4.3. Data Analysis Strategy

The data analysis was conducted in three sequential stages using SPSS 27 and AMOS 26, in line with recent SEM-based studies on sustainable consumer behavior. First, preliminary diagnostics included assessments of missing data, outlier detection, and common method bias using Harman’s single-factor test and an unmeasured latent method factor approach. Second, the measurement model was evaluated via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to establish construct reliability and validity. Reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR), with values above 0.70 considered acceptable. Convergent validity was examined through average variance extracted (AVE > 0.50) and the significance of standardized loadings (p < 0.001), while discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratios (HTMT < 0.85), consistent with best practices in SEM research on green consumption.

Finally, the structural model was estimated to test the hypothesized relationships among the constructs, with model fit evaluated using multiple indices (χ2/df, RMSEA, CFI, TLI) against established benchmarks (e.g., RMSEA ≤ 0.08, CFI/TLI ≥ 0.90). Mediation effects of Perceived Cost and Perceived Risk were tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples, with mediation supported when the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. Social Capital was included as an exogenous correlate of GPB and as a covariate in robustness checks to account for potential network and trust effects influencing green purchasing patterns.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. The Profile of Respondents

In this study, “urban areas” are operationalized using the commonly employed city-tier taxonomy in mainland China. The sampling frame covers Tier-1 core metropolitan cities, Tier-2 provincial capitals and major sub-provincial cities, and Tier-3 prefecture-level cities; county-level towns and rural townships are excluded. This definition targets consumer markets with relatively dense infrastructure, established retail channels, and active policy communication, which aligns with the study’s focus on green purchase decisions in urban settings. Geographic coverage spans the eastern, central, and western macro-regions to reflect heterogeneity in market conditions within the urban context.

The demographic profile of the 420 valid respondents highlights the diversity and representativeness of the sample. The gender distribution was balanced, with 51.7% male and 48.3% female participants. Most respondents were aged 21–30 (33.5%) and 31–40 (28.8%), while the rest spanned younger and older age groups. Educational backgrounds were evenly distributed, with 34.5% having high school education or below, 31% holding associate or bachelor’s degrees, and 34.5% possessing master’s degrees or higher. Occupations included employees (22.9%), civil servants (21%), students (16%), freelancers (16.4%), and retirees (17.1%). Monthly income levels ranged widely, with 26.6% earning $700–1100, followed by 19.6% earning $420–700, and others distributed across higher and lower brackets. Table 2: Demographic Profile of Respondents provides a detailed summary of these characteristics, ensuring the study’s findings are grounded in a diverse and representative sample.

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Respondents.

5.2. Pearson Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the linear relationships among the six core constructs of this study: Personal Motivation, Civic Motivation, Perceived Cost, Perceived Risk, Social Capital, and Green Purchase Behavior (GPB). The results, presented in Table 3, indicate that all correlations were significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), demonstrating statistically robust associations that align with the hypothesized conceptual framework. Both Personal Motivation (r = 0.436) and Civic Motivation (r = 0.426) exhibited moderate positive correlations with GPB, implying that higher levels of self-oriented and civic-oriented drives are associated with stronger pro-environmental purchasing intentions. Social Capital showed a slightly stronger correlation with GPB (r = 0.460), highlighting its role as a key enabler in sustainable consumption behaviors. Conversely, Perceived Cost (r = −0.495) and Perceived Risk (r = −0.416) were moderately and negatively correlated with GPB, suggesting that heightened perceptions of cost and uncertainty act as notable deterrents to green purchasing. Additionally, Perceived Cost and Perceived Risk were positively correlated (r = 0.449), reflecting their interconnected nature as barriers in consumer decision-making. Social Capital was positively associated with both Personal Motivation (r = 0.447) and Civic Motivation (r = 0.383), indicating that strong social networks and community norms amplify motivational drivers. In contrast, Perceived Cost correlated negatively with Personal Motivation (r = −0.412) and Civic Motivation (r = −0.422), while Perceived Risk demonstrated a negative correlation with Civic Motivation (r = −0.366), further confirming the inhibitory influence of perceived barriers. According to Cohen’s (1988) [53] criteria, correlations between 0.10 and 0.29 are small, 0.30–0.49 are moderate, and ≥0.50 are strong; the observed coefficients predominantly fall within the moderate range, supporting the theoretical validity of the proposed relationships.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation.

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs within the measurement model. The results indicated a strong model fit, as supported by the goodness-of-fit indices. These indices, summarized in Table 4, met the recommended thresholds, demonstrating a well-specified and robust model. Specifically, the CMIN/DF value of 1.083 falls well within the acceptable range of 1–3 [49], the CFI (0.967) exceeds the widely accepted cut-off value of 0.90 [54] (Byrne, 2012) [55], and the IFI (0.997) and NFI (0.965) both surpass the 0.90 threshold (Bollen, 1989. Additionally, the TLI (0.996) exceeds the recommended minimum of 0.90 [54], while the RMSEA (0.014) is well below the acceptable maximum of 0.08 [54,56]. These findings validate the robustness of the measurement model and support its suitability for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Table 4.

Model Fit Indices for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

The results of the CFA provided strong evidence for both convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. Convergent validity was assessed using Composite Reliability (CR > 0.70) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50) criteria [51,52]. All constructs demonstrated CR values above 0.70 and AVE values exceeding 0.50, confirming that the observed indicators reliably measured their respective constructs and had sufficient shared variance. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing each construct’s square root of AVE with its correlations with other constructs. As shown in Table 5, the diagonal values, representing the square root of AVE, exceeded all inter-construct correlations, providing evidence that the constructs were distinct and captured unique dimensions of the theoretical framework [51]. These results establish the robustness of the measurement model, ensuring its reliability for subsequent structural analysis and hypothesis testing.

Table 5.

Discriminant Validity Analysis.

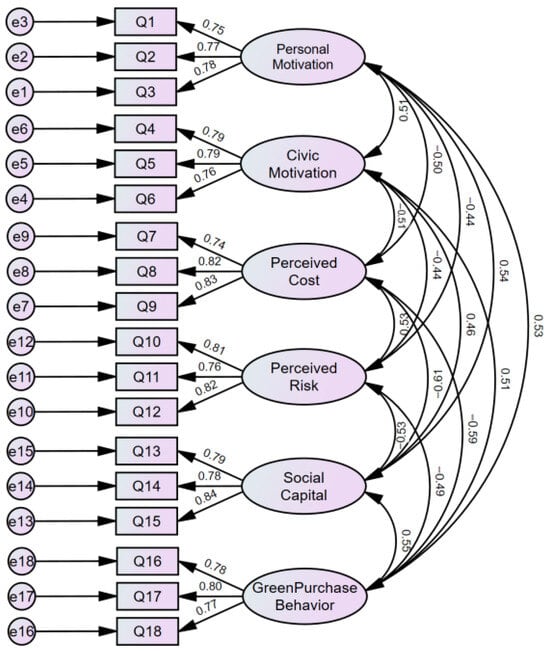

Figure 2: Measurement Model of Constructs demonstrates the relationships among the latent constructs, standardized factor loadings, and inter-construct correlations. The standardized factor loadings for all observed variables exceeded the threshold of 0.70, which confirms the reliability and construct validity of the measurement model. This threshold, widely accepted in the literature, ensures that the observed variables provide a strong representation of their respective latent constructs [50,52].

Figure 2.

Measurement Model of Constructs (CFA). e1–e18 are SEM residual terms (typically not reported), and Q1–Q18 are questionnaire items defined in the meas-urement section (typically not reported).

5.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted to evaluate the hypothesized relationships among Personal Motivation, Civic Motivation, Perceived Cost, Perceived Risk, Social Capital, and Green Purchase Behavior (GPB). As presented in Figure 3, the SEM model outlines the standardized path coefficients and the interrelationships among the constructs.

Figure 3.

Structural Model with Standardized Path Coefficients. e1–e18 are SEM residuals and Q1–Q18 are observed items.

The model fit indices, detailed in Table 6, confirmed the adequacy of the structural model. Specifically, the values for CMIN/DF (1.786), CFI (0.940), IFI (0.973), NFI (0.940), TLI (0.966), and RMSEA (0.043) all satisfied the recommended thresholds, indicating that the data align well with the proposed model [54,57].

Table 6.

Fit Indices for Structural Model.

The standardized path coefficients reveal that Personal Motivation had a significant positive effect on GPB (β = 0.43, p < 0.01), as did Civic Motivation (β = 0.45, p < 0.01). Perceived Cost exhibited a significant negative relationship with GPB (β = −0.37, p < 0.01), while Perceived Risk also negatively affected GPB (β = −0.20, p < 0.05). Additionally, Social Capital demonstrated a significant positive association with GPB (β = 0.43, p < 0.01).

The relationships among motivations, perceived barriers, and social capital were also assessed. Personal Motivation negatively influenced Perceived Cost (β = −0.36, p < 0.01) and Perceived Risk (β = −0.31, p < 0.05), while Civic Motivation similarly exhibited negative effects on Perceived Cost (β = −0.34, p < 0.01) and Perceived Risk (β = −0.31, p < 0.05). Both Personal Motivation (β = 0.56, p < 0.01) and Civic Motivation (β = 0.61, p < 0.01) had positive relationships with Social Capital. These results are supported by high standardized factor loadings across all measurement items, as shown in Figure 3, with all loadings exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 [52]. These findings indicate the robustness of the model and its components, with significant relationships among the constructs.

5.5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 7 summarizes the hypothesis testing results, presenting the standardized regression weights, standard errors, critical ratios, and significance levels for each proposed relationship. All proposed hypotheses were supported, demonstrating the robustness of the theoretical framework.

Table 7.

Hypothesis Testing Results.

The results indicate that Personal Motivation significantly reduces Perceived Cost (Estimate = −0.373, p < 0.001) and Perceived Risk (Estimate = −0.341, p < 0.001). Similarly, Civic Motivation has a significant negative impact on both Perceived Cost (Estimate = −0.362, p < 0.001) and Perceived Risk (Estimate = −0.308, p < 0.001). These findings support the hypothesized relationships that motivations mitigate perceived barriers to green purchasing behavior.

Social Capital was significantly influenced by both Personal Motivation (Estimate = 0.453, p < 0.001) and Civic Motivation (Estimate = 0.273, p < 0.001), highlighting the role of motivations in fostering trust, shared norms, and community networks. Additionally, Perceived Cost (Estimate = −0.372, p < 0.001) and Perceived Risk (Estimate = −0.203, p < 0.001) negatively impacted Green Purchase Behavior, while Social Capital positively influenced Green Purchase Behavior (Estimate = 0.274, p < 0.001).

5.6. Mediation Effect Analysis

Mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS 3.5 with 5000 bootstrap samples to evaluate the indirect effects of Perceived Cost, Perceived Risk, and Social Capital on the relationships between Personal Motivation, Civic Motivation, and Green Purchase Behavior (GPB). This approach follows established mediation testing procedures, ensuring robust and reliable results [58,59]. The findings in Table 8 present the direct, indirect, and total effects, together with confidence intervals and significance levels.

Table 8.

Mediation Effect.

The analysis confirmed full mediation for all examined pathways. For Personal Motivation → Perceived Cost → GPB, the indirect effect was significant (β = 0.163, 95% CI [0.1161, 0.2133], SE = 0.0248), indicating that Perceived Cost fully mediates the influence of Personal Motivation on GPB. Similarly, for Civic Motivation → Perceived Cost → GPB, the indirect effect was significant (β = 0.1648, 95% CI [0.116, 0.2191], SE = 0.0263), supporting the role of perceived cost as a barrier in civic-oriented motivations.

For pathways involving Perceived Risk, mediation effects were also significant. The indirect effect for Personal Motivation → Perceived Risk → GPB was β = 0.1121 (95% CI [0.0725, 0.1592], SE = 0.022), while for Civic Motivation → Perceived Risk → GPB it was β = 0.1117 (95% CI [0.073, 0.1553], SE = 0.0209), confirming that perceived uncertainty reduces the translation of motivations into behavior.

Social Capital further acted as a significant mediator. For Personal Motivation → Social Capital → GPB, the indirect effect was β = 0.1537 (95% CI [0.1067, 0.2047], SE = 0.025), and for Civic Motivation → Social Capital → GPB, β = 0.1352 (95% CI [0.0913, 0.1844], SE = 0.0234), highlighting the facilitative role of trust, shared norms, and social networks in promoting GPB.

Across all pathways, total effects remained significant, while direct effects became non-significant or substantially reduced, underscoring the essential mediating roles of Perceived Cost, Perceived Risk, and Social Capital. These findings align with theoretical perspectives such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [7] and the Value–Attitude–Behavior model [60], which emphasize the joint influence of motivational and contextual factors in shaping pro-environmental behavior.

6. Discussion

Several features of the evidence run against common priors and collectively reshape how the motivational architecture of green purchasing should be understood. Most striking is the motivational symmetry: personal and civic motivations retain comparably strong direct associations with behavior instead of the anticipated dominance of self-interest. The pattern reads less like substitution and more like complementarity, where private utility (health, thrift) and public meaning (responsibility, stewardship) co-produce a dual justification that stabilizes choice under heterogeneous evaluative standards. Identity-based accounts make this intelligible: actions that are simultaneously self-congruent and norm-congruent minimize reputational ambiguity and post-purchase dissonance, thereby lowering the latent “cost” of commitment. Measurement caveats—shared evaluative tone or survey-context priming—cannot be entirely excluded, yet the persistence of parallel direct paths after accounting for cost, risk, and social capital argues against a purely artifactual explanation. Substantively, interventions predicated on a single dominant motive are likely underpowered; bundled framing that fuses private benefits with public goods should travel farther.

Equally consequential is the presence of residual direct effects from both motives to behavior even after introducing the proposed mediators. This points to channels that either bypass or operate alongside contemporaneous appraisals and relational resources—most plausibly green identity, habit strength, and self-expressive utility. If motivations are relatively stable while perceived cost, perceived risk, and social capital are episodic or context-triggered, cross-sectional models will understate mediated influence over longer horizons and overstate direct influence at a single time slice. A dynamic reading follows: barrier–enabler mechanisms may be decisive at adoption, whereas identity and habit consolidate persistence, gradually reducing the explanatory share of cost–risk and elevating routine and self-congruent expression as purchase becomes the default.

A further departure from expectations concerns the attenuated risk pathway relative to cost. In this setting, affordability appears to be the binding constraint, with informational uncertainty playing a secondary role. Market maturation can account for the shift: third-party certifications, platform reviews, and visible peer usage compress the variance of perceived risk, while green attributes often still carry price premia, leaving budget constraints as the salient friction. Category structure matters as well—where goods are primarily search or experience rather than credence, modest effort suffices to evaluate quality, again muting risk. Social capital may also provide normative insurance by making underperformance socially sanctionable and remediation more credible. The boundary condition is clear: as prices converge or subsidies diffuse, risk can re-emerge as the marginal impediment, particularly in credence-heavy domains (offsets, complex retrofits) where verification remains costly.

Finally, the data reveal a pronounced coupling of civic motivation with social capital, suggesting that public-spirited intent converts to action more efficiently in dense, trusting networks with credible norm enforcement. This aligns with models of reputational returns and collective-action thresholds, but it also raises identification challenges because social capital can be both a precursor and a consequence of adoption. Untangling these dynamics will require time-ordered and network-sensitive designs capable of separating endogenous peer effects from contextual confounds. Practically, the coupling implies that civic appeals scale only when embedded in relational scaffolding that renders green choices socially legible, reciprocated, and collectively rewarded.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions: A Dual-Motive, Dual-Barrier, Relational-Enabler Synthesis

This study contributes a consolidated account of green purchasing in which parallel motivational streams traverse a shared layer of frictions and a relational amplifier. Evidence of motivational symmetry—personal and civic motives exhibiting comparably strong direct associations with behavior—supports a complementarity rather than a substitution logic, wherein private utility (e.g., thrift, health) and public meaning (e.g., responsibility, stewardship) jointly underwrite choice. The persistence of significant direct effects after conditioning on perceived cost, perceived risk, and social capital indicates that barrier–enabler mechanisms are necessary but insufficient, and that identity-based and habit-formation conduits likely transmit motivational influence with limited contemporaneous deliberation. The resulting architecture—dual motives engaging dual barriers and a relational enabler, with identity and habit consolidating adoption—offers a parsimonious explanation for the recurrent observation of partial mediation while preserving the analytical distinction between egoistic and civic logics.

The synthesis sharpens theoretical mapping and specifies scope conditions for TPB–VBN hybrids. Within TPB, perceived cost and risk operate as constraints on perceived behavioral control and outcome valuation, whereas social capital enhances injunctive/descriptive norms and alleviates information frictions, thereby increasing intention–action conversion efficiency; within VBN, civic motivation aligns with moral obligation and personal motivation with utility-based valuation, yet both must traverse the barrier layer to manifest behaviorally. The attenuated role of risk relative to cost in the present context implies contingency: where price premia are salient and total cost of ownership remains opaque, affordability constitutes the binding friction; risk re-emerges as the marginal impediment in credence-heavy categories with weak verification infrastructure. Conceptualizing social capital as a relational multiplier elevates it from contextual covariate to a parameter conditioning the elasticity of motives, clarifying why peer visibility and community scaffolding routinely outperform message-only interventions. Together, these claims yield a context-sensitive template for modeling green consumption that is motivationally plural, mechanistically explicit, and temporally dynamic.

Our inferences should be read within contextual and cultural bounds. The salience of civic motivation and the mobilization of social capital are likely contingent on governance arrangements and sectoral conditions (e.g., pricing regimes, labeling/assurance systems, after-sales infrastructures), which we do not model explicitly. Moreover, civic motivation vs. self-interest are culturally embedded; their relative weight may differ across more collectivist or individualist settings and across domains of action. Given the study’s single-context, urban-consumer sample, conclusions are not intended to generalize to other populations or to organizational decision making. We therefore interpret effect sizes as context-specific and encourage cross-cultural and sector-comparative replications (e.g., household durables vs. mobility vs. food) and designs that vary governance features to test whether the instrumental (cost/risk) and relational (social-capital) channels strengthen or attenuate under alternative institutional environments.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

As with most studies of consumer behavior in rapidly evolving markets, this work adopts a cross-sectional design and employs parsimonious measures of social capital, perceived cost, and perceived risk. These choices provide a clear baseline test of the proposed framework but inevitably capture these constructs in a relatively static manner. In addition, the evidence is drawn from urban respondents within a single country and from product categories at similar stages of market development. While this focused setting strengthens internal coherence, it naturally narrows external generalizability and leaves heterogeneity across contexts for subsequent inquiry.

Looking ahead, a practical next step is to track respondents over time or to leverage quasi-experimental variations in price signals, certifications, or community initiatives to illuminate the sequencing from motivation to mediators and behavior. Comparative studies across economies with different consumption levels would further clarify scope conditions. Model enrichment could explicitly incorporate green identity and habit formation as complementary pathways, and operationalize network features of social capital (e.g., density, tie strength, visibility) as mediating or moderating channels. Where feasible, augmenting surveys with transactional or platform data would add robustness, helping translate the present baseline into a more causally informative and readily transferable mechanism framework.

7. Conclusions

This study explored the effects of personal motivation and civic motivation on green purchase behavior (GPB), with perceived cost, perceived risk, and social capital as mediators. The SEM results demonstrated that both personal and civic motivations positively influenced GPB. Perceived cost and perceived risk acted as significant barriers, while social capital played a facilitative role. Mediation analysis revealed that the effects of motivations on GPB were fully mediated through these three variables.

These findings are consistent with prior studies emphasizing the role of economic considerations and risk perceptions in sustainable consumption decisions. The negative mediating effects of perceived cost and perceived risk confirm that even strong pro-environmental motivations can be hindered by financial and uncertainty-related concerns, aligning with earlier evidence that perceived barriers are critical determinants of green behavior adoption. At the same time, the positive role of social capital corroborates research suggesting that trust, shared norms, and social networks foster pro-environmental actions, while extending these insights by demonstrating its mediating function between civic motivation and GPB.

By integrating motivational drivers, perceived barriers, and social resources into a single framework, this research extends the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value–Attitude–Behavior model by empirically validating the sequential influence of motivation, contextual constraints, and social context on GPB. This integration not only reaffirms established findings but also provides a more nuanced understanding of how intrinsic and collective motivations are translated into sustainable purchasing actions through specific psychological and social mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C.; Methodology, K.C.; Software, J.M.; Validation, J.M.; Formal analysis, J.M.; Investigation, K.C.; Resources, K.C.; Data curation, J.M.; Writing—original draft, K.C.; Writing–review and editing, K.C.; Visualization, K.C.; Supervision, J.-N.L.; Project administration, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Humanities and Social Science (Protocol code HREC-HSS-2500502D and date of 10 March 2025 approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy reasons, the data are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Dimensions and Corresponding Scale Items.

Table A1.

Dimensions and Corresponding Scale Items.

| Dimension | Item | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Motivation | Q1 | Buying green products benefits my health and wellbeing. | Schlegelmilch et al. [40] |

| Q2 | Green products help me save resources and money in the long run. | ||

| Q3 | I choose green products because they offer practical benefits for me. | ||

| Civic Motivation | Q4 | I feel a moral obligation to support environmentally friendly products. | Gupta & Ogden [41] |

| Q5 | I buy green products because it is my responsibility to protect nature. | ||

| Q6 | Purchasing green products reflects my commitment to social responsibility. | ||

| Perceived Cost | Q7 | Green products are often too expensive for me to afford. | Dodds et al. [42] |

| Q8 | The high cost of green products discourages me from buying them. | ||

| Q9 | The price of green products often outweighs their perceived benefits. | ||

| Perceived Risk | Q10 | I am not confident about the authenticity of green product certifications. | Featherman & Pavlou [43] |

| Q11 | I worry that green products may not perform as advertised. | ||

| Q12 | There is a risk that green products might not meet my expectations. | ||

| Social Capital | Q13 | Using green products in daily life builds a positive social image. | Dinnie et al. [44] |

| Q14 | My family and friends believe that buying green products is the right thing to do. | ||

| Q15 | Owning and using green products can earn more respect or recognition from friends or colleagues. | ||

| Green Purchase Behavior | Q16 | I actively seek eco-friendly products when shopping. | Haws et al. [45] |

| Q17 | I prioritize green products over conventional ones whenever possible. | ||

| Q18 | I frequently buy products that are labeled as environmentally friendly. | ||

References

- Chen, K.; Mei, J.; Sun, W. The Impact of Egoistic Motivations on Green Purchasing Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Symbolic and Functional Benefits in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, M.J.S.; Konuk, F.A.; Otterbring, T. Anxious Altruism: Virtue Signaling Mediates the Impact of Attachment Style on Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior and Prosocial Responses. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 196, 603–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, V.; Scopelliti, M.; Angelini, G.; Boezeman, E.J.; van Doesum, N.J.; Staats, H.; Fiorilli, C. Understanding Proenvironmental Behavior: A Model Based on Moral Identity and Connection to Nature. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 55, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L. China NEV retail up 5% year-on-year to 1.08 million in Aug, preliminary CPCA data show. CnEVPost, 3 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua. China’s home appliance sales surge in 2024 under trade-in scheme. Xinhua, 20 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Myllyvirta, L.; Qin, Q.; Qiu, C. Clean-energy technologies made up more than 10% of China’s economy in 2024 for the first time ever, with sales and investments worth 13.6tn yuan ($1.9tn). Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, 19 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stren, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Esteve, M.; Kempen, R. Public service motivation and pro-environmental behaviors: A survey experiment. Int. Public Manag. J. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Sivapalan, A.; Das, M.; Maseeh, H.I.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Strong, C.; Sangroya, D. A meta-analytic integration of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm model to predict green consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 1141–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, V.; Agrawal, R. Barriers to consumer adoption of sustainable products—An empirical analysis. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 19, 858–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, M.; Kumar, D. Benchmarking the barriers of sustainable consumer behaviour. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 18, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Furuoka, F. Linking social capital to green purchasing intentions in livestreaming sessions: The moderating role of perceived visible heterogeneity. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, H.; Feng, J. Factors Driving Social Capital Participation in Urban Green Development: A Case Study on Green Renovation of Old Residential Communities Under Urban Renewal in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska-Mieruszewska, J.; Zientara, P.; Mrzygłód, U.; Fornalska, A. Motivations for participation in green crowdfunding: Evidence from the UK. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 6139–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L. Intention and behavior toward bringing your own shopping bags in Vietnam: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Soc. Mark. 2022, 12, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Rhee, T.-h. How Does Corporate ESG Management Affect Consumers’ Brand Choice? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, J.; Lei, Q. Exploring the influence of environmental values on green consumption behavior of apparel: A chain multiple mediation model among Chinese Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Gursoy, D.; Dang-Van, T.; Nguyen, N. Effects of hotels’ green practices on consumer citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 118, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value orientations and environmental beliefs in five countries: Validity of an instrument to measure egoistic, altruistic and biospheric value orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Lou, Q. Will “Green” Parents Have “Green” Children? The Relationship Between Parents’ and Early Adolescents’ Green Consumption Values. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. Research on the impact of green advertising information on green purchase behavior in social media: SEM-ANN approach. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L. Understanding the Psychological Pathways from Ocean Literacy to Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Marine Responsibility and Values. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1623231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kumar, J.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Pro-environmental behavioural intention towards ecotourism: Integration of the theory of planned behaviour and theory of interpersonal behaviour. J. Ecotourism 2025, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.C.; Quynh, V.T. Vietnamese Gen Z consumers’ intentions toward carbon offsetting in transportation: An extended Theory of Planned Behavior approach. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2025, 62, 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Jam, F.; Khan, T. Fostering eco-friendly behaviors in hospitality: Engaging customers through green practices, social influence, and personal dynamics. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, N.; Fan, W.; Ren, M.; Li, M.; Zhong, Y. The Role of Social Norms and Personal Costs on Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuy, T.T.T.; Thao, N.T.T.; Thuy, V.T.T.; Hoa, S.T.O.; Nga, T.T.D. Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Flicinska-Turkiewicz, J. Overcoming perceived sacrifice as a barrier to the adoption of green non-purchase behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Fauzi, M.; Harun, S. From perceived green product quality to purchase intention: The roles of price sensitivity and environmental concern. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025, 43, 1329–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Shan, J. Social capital and environmentally friendly behaviors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 151, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Lit, K.K.; Cheung, C.T.Y.; Lau, M.M.; Wan, C.; Choy, E.T.K. The impact of social media exposure and online peer networks on green purchase behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 165, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yao, X.; Sinha, P.N.; Su, H.; Lee, Y.-K. Why do government policy and environmental awareness matter in predicting NEVs purchase intention? Moderating role of education level. Cities 2022, 131, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Lin, H.; Han, W.; Wu, H. ESG in China: A review of practice and research, and future research avenues. China J. Account. Res. 2023, 16, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, R. Decisions under risk are decisions under complexity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2024, 114, 3789–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.P.; Sargent, T.J. Risk, ambiguity, and misspecification: Decision theory, robust control, and statistics. J. Appl. Econom. 2024, 39, 969–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Aswal, C.; Paul, J. Factors affecting green purchase behavior: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnie, K.; Melewar, T.; Seidenfuss, K.U.; Musa, G. Nation branding and integrated marketing communications: An ASEAN perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Long, R. How does green communication promote the green consumption intention of social media users? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Furr, R.M. Psychometrics: An Introduction; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Streimikis, J.; Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. A comparative analysis of multivariate approaches for data analysis in management sciences. E+ M Ekon. A Manag. 2024, 27, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ximénez, C.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Shi, D.; Revuelta, J. Assessing cutoff values of SEM fit indices: Advantages of the unbiased SRMR index and its cutoff criterion based on communality. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2022, 29, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R.; Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Test. Struct. Equ. Models 1993, 154, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitema, B. The Analysis of Covariance and Alternatives: Statistical Methods for Experiments, Quasi-Experiments, and Single-Case Studies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. An alternative interpretation of attitude and extension of the value–attitude–behavior hierarchy: The destination attributes of Chiang Mai, Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).