Abstract

Early prediction of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) yield is essential for improving productivity in tropical agricultural systems. In this study, we integrated canopy structural metrics obtained with the Tracing Radiation and Architecture of Canopies (TRAC) system, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based multispectral measurements (normalized difference vegetation index—NDVI, projected canopy area), and phenological variables collected from stages R6 to R8 under non-limiting nitrogen conditions. Exploratory analyses (correlation, variance inflation factors—VIF), dimensionality reduction (principal component analysis—PCA), and regularized regression (Elastic Net/LASSO), combined with bootstrap stability selection, were applied to identify a parsimonious subset of robust predictors. The final model, composed of six variables, explained approximately 72% of the variability in plant-level grain yield, with acceptable errors (RMSE ≈ 10.67 g; MAE ≈ 7.91 g). The results demonstrate that combining early vigor, radiation interception, and canopy architecture provides complementary information beyond simple spectral indices. This non-destructive framework delivers an efficient model for early yield estimation and supports site-specific management decisions in common bean with high spatial resolution. By enhancing input-use efficiency and reducing waste, this approach contributes to sustainable development and aligns with the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for climate-resilient agriculture.

1. Introduction

Food security and the sustainable intensification of agriculture require tools capable of accurately anticipating crop yield. In this context, early yield prediction at the plant scale has become a central challenge in precision agriculture and high-throughput phenotyping [1,2]. Reliable predictive models enable the optimization of management decisions, the acceleration of breeding cycles, and the guidance of irrigation and fertilization strategies. However, their effectiveness largely depends on the quality and relevance of the metrics used to characterize canopy physiological and structural status [3,4].

Recent research confirms that early yield prediction has become an essential component of smart agriculture, driven by the expansion of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the application of machine learning algorithms. Reviews highlight the integration of multispectral remote sensing, statistical modeling, and big data analytics as key pillars for improving agricultural efficiency [5,6].

UAV-mounted remote sensors have transformed phenotyping by enabling spectral sampling with high spatial and temporal resolution. Although indices such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) are widely used for their sensitivity to vegetative vigor, they present notable limitations—particularly saturation in dense canopies—that reduce their ability to discriminate subtle differences at advanced stages [7]. To overcome this issue, complementary variables such as the Leaf Area Index (LAI) and the Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation (FAPAR) provide more robust information on photosynthetic efficiency and canopy architecture [8,9,10]. These variables, derived from radiative transfer models, capture variations that simple spectral indices fail to detect and have proven to enhance yield prediction accuracy across several crops.

In common bean, Saravia et al. [11] demonstrated that incorporating canopy structural metrics significantly improved the performance of spectral models, underscoring the need to integrate attributes beyond classical indices. According to recent reviews, yield prediction must advance “beyond NDVI” by combining structural and optical attributes derived from remote sensing that reflect canopy geometry and radiative behavior [12].

The combination of structural and optical metrics poses analytical challenges. Multicollinearity among indices can compromise the accuracy and interpretability of simple linear models [13]. To address this issue, regularization and machine learning techniques (LASSO, Elastic Net) have been proposed to handle redundancy and select relevant predictors, while dimensionality reduction (principal component analysis—PCA) synthesizes physiological gradients into interpretable axes [14]. These approaches have been successfully applied to both legumes and cereals, showing that coefficient penalization and dimensionality reduction enhance model stability and enable the identification of physiologically meaningful predictors [6,12,15,16,17]. Collectively, these studies indicate that integrating optical and structural metrics within multivariate frameworks represents a prevailing trend in high-throughput phenotyping.

In common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), most studies assessing the relationship between canopy traits and yield have been conducted at the plot scale and rely primarily on spectral indices such as NDVI [18]. Saravia et al. [11] reported moderate correlations between NDVI and yield, whereas Tavares et al. [19] demonstrated that incorporating spectral and nitrogen-related variables into machine learning models improved estimation accuracy. Similarly, Panigrahi et al. [20] integrated LiDAR and multispectral data for dry bean phenotyping, revealing that canopy height and volume metrics explained a substantial portion of yield variability. However, studies that simultaneously integrate detailed structural measurements—such as those derived from the TRAC system—with UAV observations at the individual plant level remain scarce. This gap justifies the present study, which aims to combine optical and structural canopy metrics within a parsimonious modeling framework.

Early and accurate yield prediction enhances agronomic efficiency and directly contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 2: Zero Hunger; SDG 13: Climate Action; and SDG 15: Life on Land) by promoting resource-efficient and climate-resilient agricultural practices.

Recent literature emphasizes that remote sensing and machine learning are not only key enablers of productivity but also fundamental drivers of agricultural sustainability.

Their integration enhances water and nutrient use efficiency, reduces environmental footprints, and supports climate-resilient farming practices [21,22]. Advances in smart sensors and data-driven decision systems further reinforce the role of precision agriculture in optimizing inputs and promoting resource-efficient management, aligning directly with global sustainability targets and evidence-based strategies for sustainable intensification. These technological frameworks provide a robust scientific foundation for resilient, high-efficiency crop management in emerging and resource-constrained agroecosystems. Collectively, these approaches underscore the role of data-driven phenotyping as a key enabler of climate-resilient and resource-efficient agriculture.

This study was conducted using a field-based experimental design with controlled agronomic management to minimize external variability. Nitrogen was applied at a non-limiting rate to isolate structural and physiological effects on yield and reduce the influence of nutrient-related factors. Although environmental conditions were not artificially regulated, uniform irrigation, pest control, and plant spacing ensured consistent growth across the plot. Canopy structural and radiative transmission measurements were obtained using the TRAC system (Tracing Radiation and Architecture of Canopies) [23] and UAV observations (NDVI and projected area) during phenological stages R6–R8. These stages correspond to critical phases of reproductive development: R6 (full pod formation), R7 (onset of physiological maturity), and R8 (full maturity). During this transition, canopy architecture, light interception, and leaf area dynamics directly influence grain filling and final productivity [24,25]. Consequently, monitoring structural and radiative traits at these stages provides the most reliable indicators of yield potential while minimizing the confounding effects of vegetative growth variability.

The analysis included exploratory assessments (correlations, VIF, PCA), regularization methods (Elastic Net/LASSO), and bootstrap-based stability selection, enabling the identification of physiologically interpretable and statistically consistent predictors.

This integrative approach combines physical measurements of radiative transmission and canopy architecture with multispectral aerial observations, establishing a unified framework that captures both the structural and functional dimensions of crop performance [26,27,28]. The combined use of TRAC and UAV data enables a non-destructive, plant-level assessment of potential productivity with high spatial and physiological fidelity. The main objective of this study was to develop and validate a parsimonious regression model to predict individual plant yield (YIELD_g) from biophysical and structural canopy metrics at phenological stages R6–R8. This modeling framework provides a reduced yet physiologically meaningful set of predictors applicable to phenotyping and precision agriculture, thereby linking data-driven modeling with the broader objectives of sustainable crop production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was conducted in the village of Cantores, municipality of Montenegro, Quindío, Colombia (4.5393° N, 75.7865° W; approximately 1300 m a.s.l.). The site corresponds to a tropical Andean ecosystem characterized by a humid temperate climate, an average annual temperature of 22 °C, and annual rainfall of 1800–2000 mm distributed in a bimodal regime. Volcanic soils with high fertility favor the cultivation of short-cycle crops such as common bean.

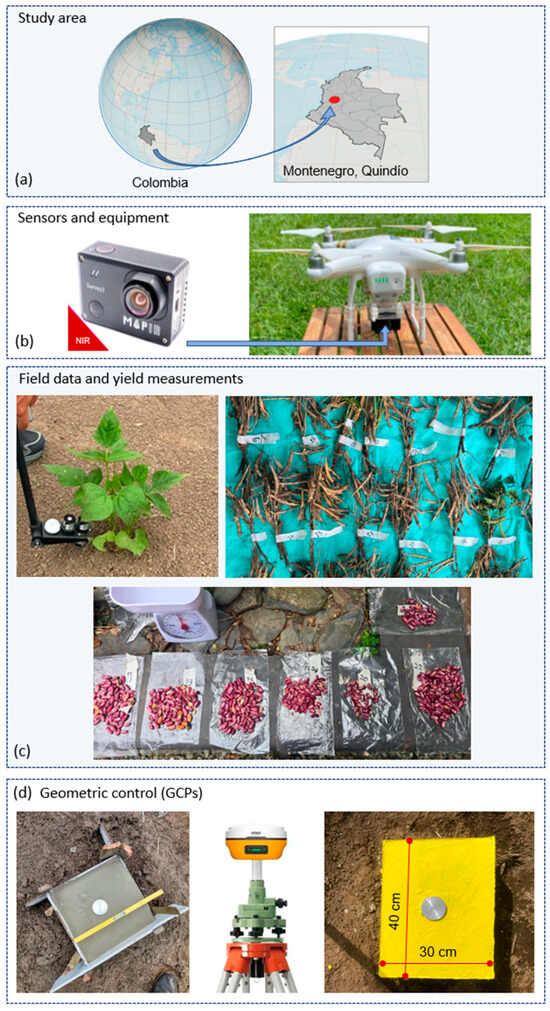

The geographical context of the study area, the sensors used for aerial and field data acquisition, the plant-level sampling procedures, and the geometric control network are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area and the methodological framework for data acquisition. (a) Geographical context (Map group): global and national maps showing the location of the study site in Montenegro, Quindío, Colombia. (b) Sensors and equipment: MAPIR Survey2 NIR camera and UAV platform used for aerial data acquisition. (c) Field data and yield measurements: TRAC optical canopy analyzer operating in the field, identification of individual plants before harvest, and dry grain samples corresponding to each plant. (d) Geometric control (GCPs): concrete geodetic benchmark during casting, static GNSS survey of the reference base, and completed benchmark (40 × 30 cm) with reflective target.

Quindío combines permanent crops such as coffee and plantain with short-cycle species, with common bean representing a strategic alternative for agricultural diversification and income generation in smallholder systems. Despite its importance, studies integrating airborne remote sensing for bean monitoring in the region remain scarce. This context justifies the present research, which seeks to leverage canopy spectral and structural metrics for phenotyping and early yield prediction, in alignment with precision agriculture approaches.

2.2. Methods

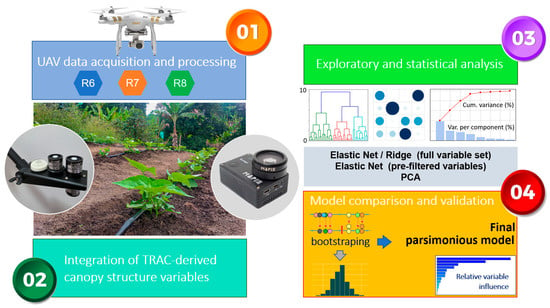

The methodological design was structured into four complementary stages to integrate spectral, structural, and yield-related information at the plant level. Figure 2 presents the conceptual workflow summarizing the complete methodological pipeline—from data acquisition to model validation—and corresponds to the organization of the following subsections. The process began with UAV-based multispectral data collection (Stage 1) and the integration of TRAC-derived canopy structural variables (Stage 2), followed by exploratory and statistical analyses (Stage 3) and the comparison and validation of predictive models (Stage 4).

Figure 2.

Conceptual workflow illustrating the four stages of the methodological design: (1) UAV data acquisition and processing at phenological stages R6–R8, (2) integration of TRAC-derived canopy structure variables, (3) exploratory and statistical analysis of biophysical and structural attributes, and (4) model comparison and validation leading to the final parsimonious model. This schematic summarizes the logical flow from data collection to model development and validation.

The field trial was conducted under non-limiting nitrogen fertilization to isolate the predictive capacity of canopy attributes. Multispectral images were acquired using UAVs, and in situ measurements were collected with the TRAC system during three phenological stages (R6, R7, and R8). These data were subsequently linked to final yield (dry grain weight per plant). Statistical analyses and predictive modeling—based on correlation analysis, regularization, and cross-validation—were then applied to identify the most explanatory attributes and phenological stages for yield prediction.

2.2.1. Experimental Design and Management Practices

The experiment was conducted in a 200 m2 plot cultivated with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L., Calima variety), sown on 16 February 2025 with a spacing of 1.0 m between plants and 1.5 m between rows, which facilitated canopy ventilation and monitoring activities. This wide spacing was intentionally implemented to allow individual-level structural and radiative measurements using the TRAC system and UAV-based imaging without canopy overlap. As a result, the canopy did not reach full closure, which minimized interplant shading effects and ensured that structural and spectral measurements accurately represented individual plant conditions.

Agronomic management included bed preparation, nitrogen fertilization, and phytosanitary applications following local recommendations. The nitrogen rate of 300 kg N ha−1 was determined from a previous study using a linear–plateau adjustment (R2 = 0.916), ensuring non-limiting nitrogen conditions and enabling the evaluation of the predictive capacity of canopy structural and biophysical attributes.

Nitrogen was applied as urea (46–0–0) and incorporated into the soil once during the pre-flowering stage (R5), coinciding with ridge formation and hilling. The fertilizer was distributed around the base of each plant and incorporated into the soil during this operation. Prior to sowing, the plot was manually tilled to a depth of approximately 30 cm to improve soil aeration and structure, followed by the application of agricultural lime to correct acidity and optimize soil sanitary conditions. After land preparation, planting lines were marked, and sowing was carried out. A drip irrigation system was installed before sowing to ensure uniform soil moisture throughout the crop cycle.

Irrigation was applied through drip systems and adjusted to the crop’s phenological demands (440–540 mm per cycle, International Center for Tropical Agriculture, CIAT) [29], ensuring homogeneous water conditions across the plot. Harvest took place on 11 May 2025, and the dry grain weight of each individual plant was recorded as the response variable for predictive modeling.

2.2.2. UAV Data Acquisition and Processing

Three UAV campaigns were conducted during the phenological stages of flowering (R6), pod formation (R7), and pod filling (R8), following the CIAT scale [30]. Each campaign consisted of a single flight carried out under optimal illumination conditions, resulting in a total of three flights during the experiment. All flights were performed between 10:00 and 14:00 under clear-sky conditions using a Phantom 3 Professional (DJI, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a fixed-mounted MAPIR Survey2 multispectral camera (red and NIR bands). The flight plan included 75% frontal and 80% lateral overlap at an altitude of 25 m, generating calibrated orthomosaics with an approximate spatial resolution of 2 cm/pixel.

To ensure high geometric accuracy, two permanent geometric control points (GCPs) were established using static GNSS surveys with long observation sessions and differential post-processing against nearby CORS stations (MAGNA-SIRGAS reference frame). The adjusted coordinates achieved mean positional uncertainties of ±0.0033 m in latitude, ±0.0078 m in longitude, and ±0.0024 m in ellipsoidal height for the first point, and ±0.0028 m, ±0.0069 m, and ±0.0050 m, respectively, for the second. These results correspond to third-order geodetic control accuracy, ensuring sub-centimeter precision for orthomosaic georeferencing. From these base points, four additional terrestrial GCPs were established using total-station surveying, completing the control network for UAV orthomosaic adjustment in Agisoft Metashape (version 1.8.4, Agisoft LLC, St Petersburg, Russia).

Radiometric consistency was maintained using a four-level reference panel (white, light gray, dark gray, and black) managed through MAPIR Camera Control (MCC) software (v1.0, released November 2017, MAPIR Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Correction coefficients were applied in Agisoft Metashape to ensure spectral consistency across flights, minimizing illumination-related variability and ensuring stability across dates and flight conditions. Despite minor geometric misalignments introduced by the fixed camera mount, the spatial resolution and planting design enabled the reliable delineation of individual plants, ensuring consistent and robust spectral metrics (NDVI and projected canopy area) throughout the phenological cycle.

The MAPIR Survey2 (NDVI Red + NIR) multispectral camera integrates a 16 MP Sony Exmor IMX206 CMOS sensor (4608 × 3456 px) with dual narrowband filters centered at 660 ± 5 nm (red) and 850 ± 10 nm (NIR), optimized for vegetation index estimation. The 4.35 mm lens and 82° field of view provided a ground sampling distance of approximately 2 cm pixel−1 at a flight altitude of 25 m.

The MAPIR Survey2 camera used in this study captures reflectance in the red and near-infrared regions with band peaks near 660 nm (red) and 850 nm (NIR). Consequently, NDVI was the primary vegetation index derived, and indices relying on a red-edge band (e.g., NDRE, MTCI) could not be computed. This spectral limitation is acknowledged and discussed in Section 4.5; however, the integration of NDVI with TRAC-derived structural variables (e.g., PAIe, FAPAR, Ωe) provided complementary spectral–structural information sufficient to characterize canopy function and support plant-scale yield prediction.

The resulting orthomosaics were processed to delineate individual plants based on the sowing pattern (1.0 × 1.5 m), from which per-plant NDVI and canopy area metrics were extracted.

2.2.3. Integration of Spectral, Morphometric, and Field Data

Each plant was individually identified and delineated in the orthomosaics using the planting framework (1.0 × 1.5 m) as a spatial reference. The ~2 cm/pixel resolution enabled precise canopy segmentation and the extraction of spectral values (NDVI) and projected canopy area for each plant.

Complementary canopy structure measurements were conducted using the TRAC system. To obtain plant-level structural metrics, individual assessments were performed by moving the TRAC sensor around each plant, maintaining a consistent trajectory at ground level below the canopy and ensuring continuous exposure to direct solar illumination. This circular sampling procedure captured the full angular variability of gap-fraction profiles, providing representative estimates of the extinction coefficient (Kmean), clumping index (Ωe), effective plant area index (PAIe), leaf area index (LAI), and fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR) for each isolated canopy.

These structural variables were recorded at stages R6, R7, and R8, allowing temporal characterization of canopy development. At harvest, the dry grain of each plant was collected and weighed individually (standardized to 14% moisture), constituting the dependent variable of the study.

Additionally, canopy height was measured manually in the field using a graduated ruler by recording the vertical distance from the soil surface to the uppermost leaf tip of each plant. Measurements were performed on all 101 plants during phenological stages R6, R7, and R8 to characterize canopy structural dynamics throughout the reproductive cycle. Although canopy height can also be estimated from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-derived digital surface models (DSM) when spatial resolution is sufficient and crops exhibit larger or more continuous canopies, the manual approach was adopted in this study to ensure accurate measurements given the relatively low stature and heterogeneous canopy of common bean.

After field acquisition, raw TRAC data were processed using TRACWin v3.9.1 (3rd Wave Engineering, Winnipeg, MB, Canada), the official software for data reduction and canopy structural analysis. The program performs data quality control, filters the gap-fraction profiles, and computes key structural parameters, including Kmean, Ωe, PAIe, LAI, and FAPAR. All computations followed the manufacturer’s algorithms, which apply geometric and solar-angle corrections to ensure the physical consistency of the estimates and their comparability with UAV-derived reflectance metrics.

To account for illumination conditions during data acquisition, the solar zenith angle (SZA) recorded by the TRAC system was included for each measurement. During the UAV and TRAC campaigns (10:00–14:00 local time), SZA values ranged approximately between 5–50° for R6, 10–25° for R7, and 17–40° for R8. These ranges are consistent with stable mid-day illumination, ensuring comparable radiometric and canopy structural measurements across stages. Although no on-site meteorological station was available, the combination of clear-sky acquisition, controlled timing, and SZA verification ensured that radiometric and canopy transmission data were not influenced by short-term fluctuations in solar radiation, temperature, or vapor pressure deficit.

The TRAC system is an optical ground-based instrument designed to quantify canopy structural properties by measuring the spatial distribution of sunlight transmitted through vegetation. It records the sequence of vegetation gaps along a transect, from which the gap fraction is computed to estimate structural parameters such as Kmean, LAI, PAIe, and Ωe. FAPAR is subsequently derived by combining the gap fraction with the solar zenith angle, reflecting canopy radiation capture efficiency [31].

The integration of UAV data and TRAC measurements produced a plant-level matrix combining spectral metrics, structural attributes, and final yield, ensuring comparability and forming the basis for predictive modeling.

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis and Predictive Modeling

The analysis matrix comprised 30 predictors derived from 10 biophysical and structural variables (Wp, Kmean, gap fraction, Ωe, PAIe, LAI, FAPAR, NDVI, projected area, and canopy height), each recorded at three phenological stages (R6, R7, and R8). The response variable was dry grain weight per plant.

All predictor variables were standardized (mean = 0; variance = 1) to ensure comparability and avoid bias in coefficient estimation. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF < 2).

Exploratory analyses included descriptive statistics, distribution assessments, and Pearson correlations with yield. To characterize variability gradients and redundancies, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied, and the first components were physiologically interpreted to complement the regularization analysis.

Regularization techniques such as the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and Elastic Net were employed to improve model interpretability and reduce multicollinearity. LASSO applies an L1 penalty that promotes sparsity by shrinking less informative coefficients to zero, thereby performing variable selection. Elastic Net combines both L1 and L2 penalties, balancing sparsity and coefficient stability, which is advantageous when predictors are highly correlated [32].

Predictor selection based on these regularization frameworks was used to identify parsimonious subsets with higher explanatory power. A parsimony criterion limited the number of predictors to six to balance model complexity and predictive capacity [33]. Selection stability was evaluated through bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations, retaining only variables consistently selected in most simulations.

Three modeling approaches were compared: (i) multiple linear regression, (ii) LASSO, and (iii) Elastic Net. To ensure reproducibility and avoid dependence on a single random partition, model performance was evaluated using repeated k-fold cross-validation (k = 10, 100 iterations), where each iteration involved a random 70/30 split between training and validation subsets. This design minimizes potential coincidences associated with a particular random division and provides stable estimates of R2, RMSE, and MAE.

In addition, predictor stability was quantified through bootstrap resampling (B = 100), computing the frequency of variable inclusion across resampled subsets (70% of the data per iteration). Model coefficients were further validated through an independent bootstrap procedure (B = 1000) to estimate 95% confidence intervals for the final model parameters.

This two-level bootstrap approach ensured both variable selection stability and coefficient reliability. These combined procedures guarantee that the reported results are statistically consistent, robust, and not influenced by random data partitioning.

The performance of each model was quantified using the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE), defined as follows:

where and represent the observed and predicted yield values, respectively, and is the mean of the observed values. These metrics were selected for their complementary ability to describe both the accuracy and dispersion of model predictions.

Finally, the selected predictors were interpreted in physiological and structural terms to identify the critical phenological stages and canopy attributes relevant to yield prediction, integrating statistical rigor, parsimony, and biological relevance while ensuring reproducibility.

3. Results

UAV flights equipped with a multispectral camera produced calibrated orthomosaics for each phenological stage, from which NDVI and projected canopy area were derived. In parallel, the TRAC optical sensor provided direct measurements of canopy structure and leaf area index, complementing the UAV-based metrics. This integration ensured consistent and comparable inputs for evaluating the explanatory capacity of canopy attributes in relation to yield.

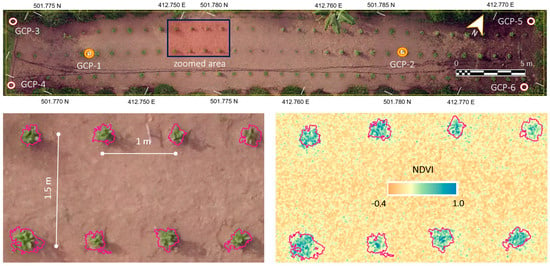

Figure 3 presents the orthomosaic generated at stage R6, together with plant-level segmentation and the corresponding NDVI map used to extract spectral metrics.

Figure 3.

UAV-derived orthomosaic of the study plot at phenological stage R6. The upper panel shows the experimental area with six geometric control points (GCP1–GCP6) used for geometric adjustment and georeferencing (mean positional uncertainty: ±0.01 m in latitude, ±0.01 m in longitude, and ±0.01 m in elevation). The blue rectangle indicates the subsection displayed below. The lower-left panel illustrates individual plant segmentation based on the 1.0 × 1.5 m planting framework, while the lower-right panel presents the corresponding NDVI map with segmented canopies used to extract spectral metrics at the plant level. Segmented canopies are shown in a single magenta color for visual delineation only.

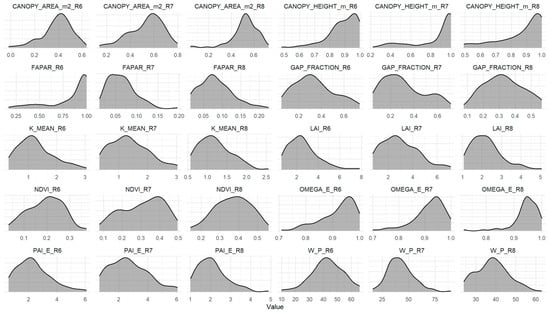

3.1. Data Characterization

The dataset comprised 101 individual plants, with 30 predictor variables and grain yield (YIELD_g) as the response variable. The 30 predictors originated from 10 biophysical and structural metrics—Wp, Kmean, gap fraction, Ωe, PAIe, LAI, FAPAR, NDVI, canopy projected area, and canopy height—each measured at three phenological stages (R6, R7, and R8), resulting in a 30-column matrix at the individual plant level. A complete description of all variables, including abbreviations, units, stages, and data sources, is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Grain yield exhibited substantial variability, ranging from 3.6 to 57.9 g, providing sufficient dispersion to discriminate among different productivity levels.

Structural predictors also showed broad ranges: canopy projected area (CANOPY_AREA_m2) varied from 0.02 to 0.79 m2, and canopy height (CANOPY_HEIGHT_m) from 0.22 to 1.0 m. Both variables tended to reach higher values at R6 and R8, as shown in the univariate distributions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Density distribution of explanatory variables.

NDVI exhibited unimodal distributions between 0.2 and 0.5, with no evidence of saturation. The leaf area index (LAI) and the fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR) reached their highest values at R6 (LAI up to 7.8; FAPAR ≈ 1) and then progressively declined through R7 and R8. Among the TRAC-derived parameters, GAP_FRACTION displayed extended tails associated with open canopies, while Ωe clustered near 1 during R7–R8, indicating lower foliage aggregation. W_P showed broad, symmetrical distributions.

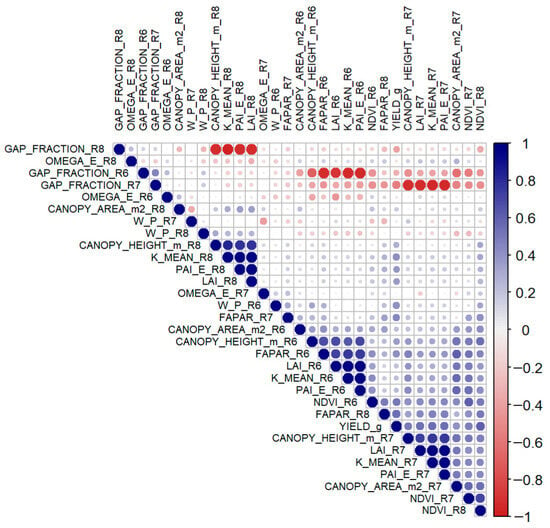

3.2. Correlations and Multicollinearity Diagnosis

The correlation analysis (Figure 5) revealed strong interdependence among leaf density metrics. Specifically, LAI, FAPAR, and PAI_E exhibited high collinearity, whereas NDVI was closely associated with CANOPY_AREA_m2. These redundancies justified explicitly assessing multicollinearity prior to modeling.

Figure 5.

Correlation map between predictor variables and grain yield.

Correlations with grain yield (YIELD_g) revealed distinct phenological patterns:

- R6: NDVI (r = 0.50), FAPAR (r = 0.41), W_P (r = 0.40), and CANOPY_HEIGHT_m (r = 0.36) showed positive correlations, while GAP_FRACTION exhibited a negative association (r = −0.32).

- R7: associations intensified, with K_MEAN (r = 0.55), PAI_E (r = 0.54), LAI (r = 0.53), NDVI (r = 0.48), and CANOPY_HEIGHT_m (r = 0.50) all displaying positive correlations, whereas GAP_FRACTION showed a strong negative relationship (r = −0.56).

- R8: NDVI (r = 0.60) and FAPAR (r = 0.55) emerged as the strongest positive predictors, while GAP_FRACTION remained negatively associated (r = −0.39).

Overall, stage R7 exhibited the highest explanatory power, with R6 and R8 providing complementary signals.

Redundancy was confirmed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), whose extreme values (Table 1) indicated severe collinearity among structural and density metrics. PAI_E_R7 (1950.76) and K_MEAN_R7 (1781.53) represented the most critical cases, reinforcing the necessity of dimensionality reduction before fitting linear models.

Table 1.

Variance inflation factors (VIF) for key predictor variables.

These extreme VIF values demonstrate that ordinary least-squares (OLS) coefficients would be unreliable; therefore, penalized and nested modeling strategies were prioritized over unregularized inference. Dimensionality reduction was implemented through VIF-based prefiltering, Elastic Net regularization, and principal component analysis (PCA), each minimizing collinearity and ensuring coefficient stability. Consequently, interpretations of variable importance are derived exclusively from penalized or stability-verified models rather than from raw OLS estimates.

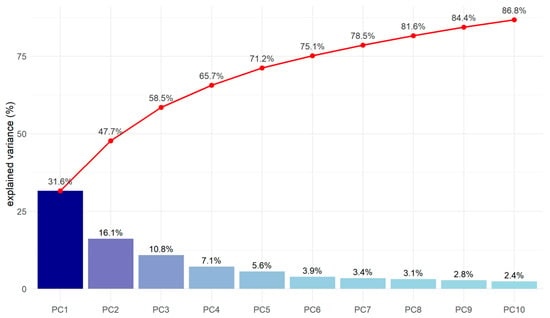

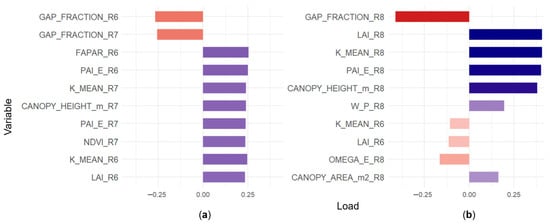

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction Using PCA

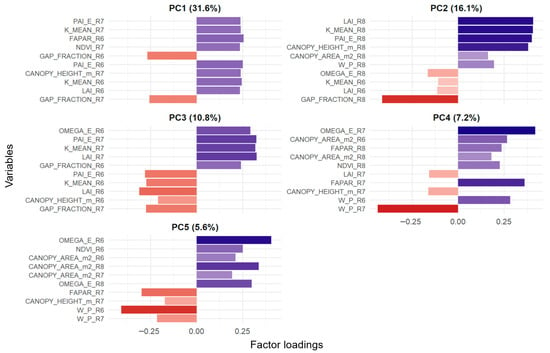

The PCA applied to the standardized predictors explained 48% of the total variance in the first two components (PC1 ≈ 31.6%; PC2 ≈ 16.1%). From PC3 onward, the cumulative contribution increased only marginally; therefore, interpretation focused on the first two axes (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Explained and cumulative variance of the first ten principal components.

PC1 (31.6%) represented a gradient associated with canopy vigor and closure during R6–R7. The highest positive loadings corresponded to FAPAR_R6, PAI_E_R6, and K_MEAN_R6 (≈+0.25), whereas GAP_FRACTION_R6 (≈−0.27) and GAP_FRACTION_R7 (≈−0.26) loaded negatively. Accordingly, high PC1 scores characterized dense canopies with greater radiation interception, while low scores reflected more open structures.

PC2 (16.1%) captured variability related to canopy architecture in R8. The strongest positive loadings were observed for LAI_R8 (≈+0.28), K_MEAN_R8 (≈+0.27), PAI_E_R8 (≈+0.27), and CANOPY_HEIGHT_m_R8 (≈+0.25), in contrast to the negative loading of GAP_FRACTION_R8 (≈−0.27). This axis differentiated individuals according to their final canopy structure, defined by height, leaf area, and stratification.

The individual contributions (Figure 7) confirmed that PC1 encapsulated indicators of canopy vigor and radiation interception efficiency during R6–R7, whereas PC2 represented mature canopy architecture at R8.

Figure 7.

Principal component loadings. (a) Loadings for PC1, representing canopy vigor and radiation interception in R6–R7. (b) Loadings for PC2, associated with mature canopy architecture in R8.

In summary, the PCA captured the redundancy observed in the distributions, correlations, and VIF values, enabling the identification of two dominant physiological gradients: early vigor (PC1) and structural architecture during maturation (PC2). These results provided a robust foundation for developing parsimonious predictive models.

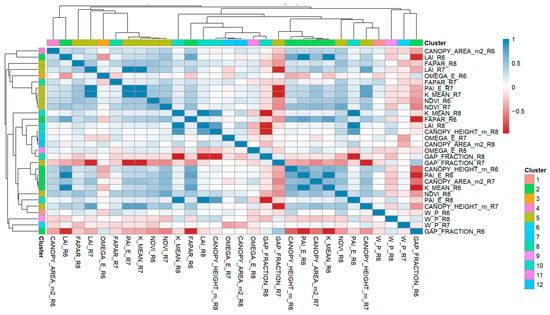

3.4. Predictor Selection and Filtering

The strong collinearity observed among several predictors justified the use of regularization and dimensionality reduction strategies to obtain parsimonious subsets of variables for modeling. Three approaches were compared: (i) multiple linear regression (OLS), used as a reference to assess performance without penalization; (ii) LASSO, which applies an absolute penalty to the coefficients, forcing some to zero and thereby performing automatic predictor selection; and (iii) Elastic Net, which combines LASSO and Ridge penalties, allowing the retention of groups of highly correlated variables and providing a balance between parsimony and information retention.

Together, these approaches enabled the comparison of models under different assumptions regarding complexity and redundancy, establishing a robust framework for identifying relevant predictors and constructing more stable models.

3.4.1. Pre-Filtering and Redundancy Assessment

The correlation analysis and VIF values confirmed pronounced redundancies among the physiological and structural predictors. Vigor indices (NDVI, LAI, FAPAR, PAI_E) formed a highly correlated block, as did canopy openness variables (GAP_FRACTION) and radiative attributes (W_P, ΩE). The hierarchical clustering heatmap (Figure 8) reflected these patterns, showing that much of the variability was concentrated within a few functional groups.

Figure 8.

Correlation heatmap with clustering.

The VIF diagnostics (Table 1) reinforced this finding, with extreme values for predictors such as PAI_E_R7 (≈1950), K_MEAN_R7 (≈1781), and GAP_FRACTION_R8 (≈440), far exceeding acceptable multicollinearity thresholds.

To mitigate this effect, an iterative pre-filtering process was applied, sequentially removing variables with extreme VIF values. As a result, the predictor set was reduced from 30 to 21, retaining three main groups:

- Physiological: NDVI, LAI, and FAPAR in R7–R8.

- Structural: CANOPY_HEIGHT_m and CANOPY_AREA_m2 in R6–R8.

- Radiative/optical: W_P and ΩE across the three stages.

This filtering reduced multicollinearity and produced a more parsimonious set for linear modeling. However, because regularization techniques such as LASSO and Elastic Net can internally manage collinearity, both the full and reduced sets were considered in subsequent analyses.

Given the extreme multicollinearity observed (VIF ≫ 10), the coefficients derived from ordinary least-squares (OLS) regressions were not interpreted as direct physiological effects. Instead, they were used solely for diagnostic and comparative purposes. Consequently, penalized regression methods (LASSO and Elastic Net) were adopted as the primary tools for reliable variable selection and inference.

Overall, the pre-filtering process refined a highly redundant initial set and established a robust foundation for comparing predictive models. The next step was to evaluate the performance of contrasting methods—from multiple linear regression to penalized approaches (LASSO, Elastic Net) and dimensionality reduction (PCA)—to identify stable and parsimonious configurations capable of explaining variability in grain yield.

3.4.2. Elastic Net/Ridge with the Full Set

The performance of the Elastic Net model was evaluated using all 30 original predictors without pre-filtering. The model was fitted using repeated cross-validation (10 folds × 3 repetitions) combined with a grid search for α and λ. Optimization yielded α = 0 and λ ≈ 7.91, corresponding to a pure Ridge regression. Although the analysis was conducted within the Elastic Net framework, the Ridge configuration produced the best performance and is therefore reported.

The model explained approximately 61% of the variability in yield (RMSE ≈ 8.82 g; R2 ≈ 0.61; MAE ≈ 7.03 g). As characteristic of Ridge regression, all variables retained non-zero coefficients. Positive effects were observed for NDVI_R6 (1.71), NDVI_R8 (1.35), FAPAR_R7 (1.71), FAPAR_R8 (1.64), LAI_R7 (0.83), CANOPY_AREA_m2_R7 (1.15), and K_MEAN_R8 (0.85). In contrast, indicators of canopy openness and angular dispersion exhibited consistent negative effects, particularly ΩE (−0.73 to −0.85 in R6–R8) and GAP_FRACTION (−0.71 in R7 and −0.69 in R8). Moderate negative contributions were also observed for K_MEAN_R6 (−0.58), PAI_E_R6 (−0.55), and CANOPY_AREA_m2_R6 (−0.44).

From a physiological standpoint, the model confirms that the predictors provided complementary information: none were discarded, but their magnitudes were penalized to prevent overfitting. The emerging pattern indicates that dense canopies with efficient radiation interception are associated with higher yields, whereas open structures or those exhibiting greater angular dispersion tend to reduce productivity.

3.4.3. Elastic Net with VIF-Prefiltered Variables

An Elastic Net model was trained using the 21 variables retained after VIF-based pre-filtering. Repeated cross-validation (10 folds × 3 repetitions) identified a Ridge configuration (α = 0, λ ≈ 6.25) as the optimal solution. This outcome confirms that the selected variables provide complementary information and, although penalized, none were excluded.

Model performance was virtually identical to that of the model using all variables (RMSE ≈ 8.8 g, R2 ≈ 0.61, MAE ≈ 7.1 g), indicating that reducing the predictor set did not compromise explanatory power.

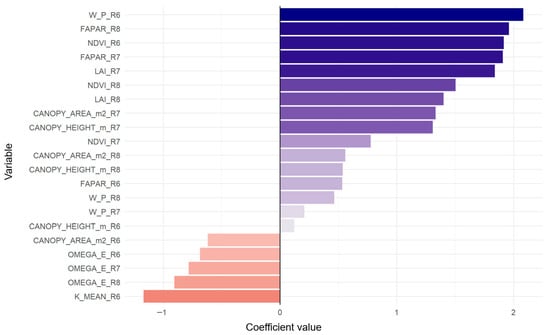

The analysis of the coefficients (Figure 9) revealed a small group of predictors with a strong positive influence on yield: W_P_R6 (2.09) was the most influential variable, followed by FAPAR_R8 (1.96), NDVI_R6 (1.92), FAPAR_R7 (1.91), and LAI_R7 (1.84). This pattern indicates that both early canopy characterization (W_P_R6, NDVI_R6) and sustained photosynthetic efficiency during intermediate and late stages (FAPAR and LAI in R7–R8) were decisive for productivity.

Figure 9.

Estimated coefficients from the Elastic Net model using the 21 variables retained after VIF prefiltering.

From a physiological perspective, the model indicates that plants exhibiting greater initial canopy cover, early vigor, and sustained radiation interception throughout the growth cycle tend to produce higher grain weight. The consistent prominence of FAPAR, LAI, and NDVI as key predictors reinforces their biological relevance, while the strong influence of W_P_R6 underscores the potential of TRAC-derived structural parameters as early indicators of productivity.

3.4.4. PCA as a Dimensionality Reduction Alternative

Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied as a dimensionality reduction strategy, followed by multiple linear regression using the first five components as predictors. The model was trained using repeated cross-validation (10 folds × 3 repetitions) and showed slightly lower performance than the penalized models, with RMSE ≈ 9.17 g, R2 ≈ 0.59, and MAE ≈ 7.43 g.

The first five components jointly explained 71.2% of the total variability (PC1 ≈ 31.6%; PC2 ≈ 16.1%; PC3 ≈ 10.8%; PC4 ≈ 7.2%; PC5 ≈ 5.6%). The analysis of factor loadings (Figure 10) revealed well-defined physiological and structural gradients:

Figure 10.

Major loadings in the first five principal components (PCA).

- PC1 (31.6%): canopy coverage and structural axis, integrating interception and density variables such as GAP_FRACTION (negative loadings) and LAI, FAPAR, and NDVI (positive loadings).

- PC2 (16.1%): final canopy density and architecture at R8, with LAI, PAI, and canopy height as the most influential variables.

- PC3 (10.8%): angular dispersion and efficiency attributes, dominated by ΩE and contrasts in LAI across stages.

- PC4 (7.2%): radiation absorption and optical properties, with FAPAR and ΩE as the main modulators.

- PC5 (5.6%): a combination of weighted optical path (W_P), plant area (CANOPY_AREA_m2), and vigor indicators (NDVI).

From a physiological perspective, the principal components summarize key processes throughout the crop cycle: PC1 integrates early vigor and canopy closure; PC2 represents structural consolidation during maturation; PC3 and PC4 capture radiation-use efficiency and canopy architecture; and PC5 combines coverage, occupied area, and radiation path. Although accounting for a smaller proportion of variance, components 3–5 complement the dominant gradients by representing secondary variability associated with photosynthetic efficiency and structural traits.

These results confirm that PCA effectively reduces redundancy among predictors while preserving the dominant physiological gradients. The slight reduction in model fit indicates that, although the approach is more parsimonious, it partially reduces predictive capacity compared with penalized models. The metrics reported here (RMSE ≈ 9.17 g, R2 ≈ 0.59, MAE ≈ 7.43 g) derive from internal cross-validation. In the final model comparison (Table 2), under a 70/30 split with internal validation, the PCA_lm_k5 model reached RMSE ≈ 11.46 g, a difference attributable to the change in the validation scheme.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of predictive models.

Specifically, the PCA_lm_k5 model achieved R2 ≈ 0.59 (RMSE ≈ 9.17 g) under repeated cross-validation (10 × 3) using the entire dataset. For consistency across all models, a final evaluation based on a fixed 70/30 train–test split yielded RMSE ≈ 11.46 g, reflecting the expected decline in performance when transitioning from internal to external validation. All models reported in Table 2 were therefore compared under this unified 70/30 framework.

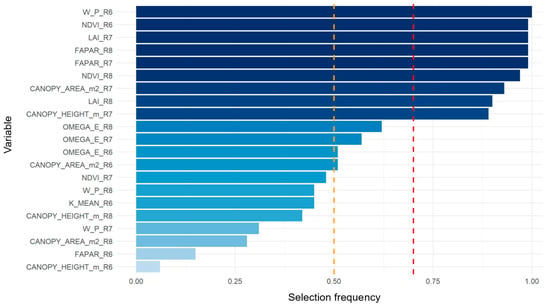

3.5. Selection Stability and Model Comparison

Selection stability was evaluated using 100 bootstrap replicates of the glmnet model. Figure 11 shows the retention frequency of each predictor, using 70% as the threshold for high stability and 50% for moderate stability.

Figure 11.

Variable selection frequency (Bootstrap glmnet).

A highly consistent core (freq ≥ 0.9)—comprising W_P_R6, NDVI_R6, LAI_R7, FAPAR_R7, FAPAR_R8, NDVI_R8, CANOPY_AREA_m2_R7, and LAI_R8—was retained in more than 90% of iterations, reflecting early vigor, intermediate leaf density, and radiation absorption during maturation. Variables such as CANOPY_HEIGHT_m_R7, ΩE_R8, and ΩE_R7 exhibited high stability (0.70–0.89), indicating their association with canopy architecture. In contrast, predictors with stability below 0.50 were considered unreliable for inclusion in parsimonious models.

Based on this analysis, three models were compared: Elastic Net with all variables, Elastic Net using the VIF-prefiltered set, and multiple linear regression using the first five principal components (PCA_lm_k5). The results are summarized in Figure 11 and Table 2. The PCA_lm_k5 model achieved the highest explanatory power (R2 ≈ 0.63), confirming the value of dimensionality reduction. However, a parsimonious model (lm_top6) was constructed from the most stable predictors, combining interpretability with predictive performance. This model achieved superior fit (R2 ≈ 0.72; RMSE ≈ 10.67 g; MAE ≈ 7.91 g) and emerged as the most balanced alternative in terms of parsimony and interpretability.

3.6. Final Parsimonious Model

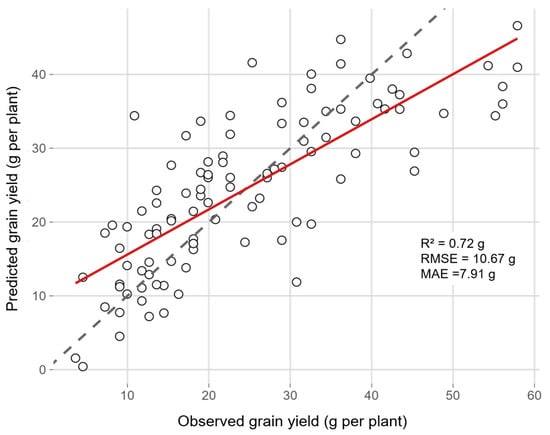

Based on the stability analysis, a parsimonious model (lm_top6) was defined using six predictors: W_P_R6, FAPAR_R7, NDVI_R6, FAPAR_R8, K_MEAN_R8, and CANOPY_AREA_m2_R7. This set captures signals of early vigor, photosynthetic efficiency during development, and structural attributes at maturity.

The model was retrained using the full dataset (n = 101), showing strong overall performance (R2 ≈ 0.72; RMSE ≈ 10.67 g; MAE ≈ 7.91 g; F ≈ 24.6; p < 0.001). The residual standard error was 8.76 g, with no indication of overfitting. Although this retraining on the full dataset (n = 101) reflects the apparent fit (R2 ≈ 0.72), the out-of-sample evaluation of the same six-feature configuration under the unified 70/30 framework yielded R2 ≈ 0.63 and RMSE ≈ 11.46 g. This distinction demonstrates that the final model maintains consistent predictive performance when tested on unseen data, confirming its generalization ability rather than overfitting.

All predictors were significant (p between <0.001 and 0.026) and had positive coefficients, confirming their consistent contribution to grain yield:

- W_P_R6 (β ≈ 0.30, p < 0.001): Early optical path length associated with higher yield.

- FAPAR_R7 (β ≈ 96.7, p = 0.002): Radiation interception during canopy development; the most influential predictor.

- NDVI_R6 (β ≈ 37.6, p = 0.012): Early photosynthetic vigor with a significant contribution.

- FAPAR_R8 (β ≈ 54.3, p = 0.026): Radiation absorption during maturation reinforces grain yield.

- K_MEAN_R8 (β ≈ 8.1, p < 0.001): Canopy angular structure with a consistent positive effect.

- CANOPY_AREA_m2_R7 (β ≈ 24.0, p = 0.001): Intermediate canopy cover complements photosynthetic vigor.

Variance inflation factors (VIF < 2) ruled out collinearity issues, confirming the stability of the model. The standardized coefficients (β) and their p-values, presented in Table 3, highlight the relative contribution of each predictor.

Table 3.

Coefficients and significance of the final parsimonious model (lm_top6).

The bootstrap analysis (1000 replications) confirmed statistical robustness: the 95% confidence intervals of all coefficients remained strictly positive, establishing lm_top6 as the most parsimonious and predictively reliable model among the evaluated strategies.

These quantitative results are graphically summarized in Figure 12, which illustrates the relationship between observed and predicted grain yield per plant for the final parsimonious model. The close alignment between the 1:1 reference line and the regression fit demonstrates the model’s ability to capture within-field yield variability and confirms its predictive robustness.

Figure 12.

Observed vs. predicted grain yield per plant using the final parsimonious model (lm_top6). Each point represents an individual plant (n = 101). The dashed gray line indicates the 1:1 relationship, while the solid red line represents the fitted regression.

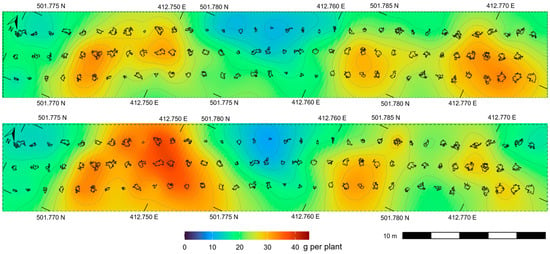

In addition to the overall model fit, the spatial comparison shown in Figure 13 provides a complementary evaluation of predictive performance. The upper panel illustrates the spatial distribution of predicted yield derived from UAV- and TRAC-based predictors using Ordinary Kriging of the lm_top6 model, whereas the lower panel presents the measured yield interpolated from field observations. The strong spatial correspondence between both surfaces demonstrates the model’s ability to capture within-field variability and delineate localized productivity gradients. These patterns highlight the potential of the integrated UAV–TRAC framework to support site-specific management and precision agronomic interventions.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of grain yield (g plant−1) at stage R8 obtained through Ordinary Kriging interpolation. The upper panel shows the predicted yield derived from UAV- and TRAC-based predictors using the lm_top6 model, whereas the lower panel depicts the measured yield interpolated from field observations. Contour lines (light gray) illustrate productivity gradients, and plant-level canopy boundaries are shown in dark gray for spatial reference. Warm tones indicate areas of higher yield, while cool tones correspond to lower-yield zones.

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenological and Structural Drivers of Yield

Individual yield variability was primarily explained by differences in early vigor, photosynthetic efficiency, and canopy architecture under non-limiting nitrogen conditions (300 kg N ha−1, a previously documented saturation level). This experimental design effectively isolated the effects of structural and physiological traits, providing a robust framework for evaluating nondestructive phenotyping metrics.

Comparable relationships between canopy traits and yield have been reported in other studies using UAV-based phenotyping in Phaseolus vulgaris and other legumes, where early vigor and light-use efficiency were strong determinants of productivity [34] [35]. Specifically, Parker et al. [36] demonstrated that early growth vigor and canopy development stages captured by UAV imagery explained most of the genotypic variation in common bean. Likewise, studies integrating UAV-based LiDAR and multispectral imaging in dry bean have shown that NDVI at stage R6 and structural proxies such as canopy height significantly improve yield prediction accuracy [20]. Similarly, multi-sensor remote sensing approaches combining spectral and structural parameters (e.g., LAI and FAPAR) have demonstrated robust yield estimations under diverse crop conditions [37].

The parsimonious model with six predictors explained approximately 72% of the variation in yield, confirming that a limited number of canopy attributes is sufficient to capture the main physiological gradients. The consistency of this result—both in statistical parsimony and physiological coherence—supports the applicability of the model for identifying key yield determinants in common bean.

4.2. Relative Importance of Spectral and Structural Metrics

Multiple studies concur that early vigor indices (e.g., NDVI) and radiation interception metrics (FAPAR, LAI) are strong predictors of yield in bean and other crops, although their effectiveness depends on phenological stage and canopy density. In high-cover scenarios, where spectral indices tend to saturate, structural derivatives—such as LAI or canopy cover—have been shown to enhance predictive capacity, particularly when integrated into machine learning models applied to UAV data [38,39,40].

FAPAR, in particular, stands out as a metric capable of overcoming the limitations of saturated spectral indices, as it directly reflects the fraction of radiation that is effectively absorbed. Studies combining UAV photogrammetry with physical models or machine learning approaches have reported highly accurate FAPAR estimates with strong predictive value [41]. Our results (~72% explained variance) contrast with those reported by Vemulakonda et al. [42], where yield increases were observed under different fertilization levels but without the integration of UAV-derived structural metrics. This contrast underscores the advantage of incorporating canopy variables to improve predictive accuracy.

In legumes, including common bean, the literature consistently reports significant correlations between spectral and structural metrics and yield, influenced by spatial resolution, phenological stage, and canopy architecture. Analyses based on Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) confirm that combining multispectral indices with structural metrics substantially increases predictive capacity compared with using spectral indices alone [43]. Similarly, structural metrics such as optical path length, extinction coefficient, PAIe, and canopy height capture subtle variations at advanced stages that spectral indices alone cannot detect. Zhou et al. [44] demonstrated that fusing multitemporal spectral features with UAV-derived structural parameters (height, canopy cover, and volume) markedly improves yield prediction.

Although our bean model explained approximately 72% of the variability, studies such as Zhang et al. [45] in maize using optimized spectral indices have shown that these can outperform traditional approaches, highlighting the importance of exploring crop-specific metrics.

Finally, the higher explanatory power observed at stage R7 aligns with previous reports emphasizing the relevance of intermediate to late reproductive phases for predicting final yield, as these integrate both growth trajectory and sustained radiation interception [46].

4.3. Physiological Interpretation of the Predictors

The predictors retained in the parsimonious model represent three key physiological mechanisms. Early vigor (W_P_R6, NDVI_R6) determined the rate of canopy closure and cumulative radiation interception, confirming its value as an early indicator of productivity [47]. Effective interception, captured by FAPAR at R7–R8, explained yield differences among plants with comparable canopy cover, consistent with studies demonstrating its advantage over spectral indices prone to saturation [48]. In turn, canopy architecture (K_MEAN_R8, CANOPY_AREA_m2_R7) modulated the vertical and angular distribution of radiation, reinforcing the relevance of structural metrics in high-density scenarios [44].

Additionally, the secondary PCA components (PC3–PC5) provided functional insights into radiation-use efficiency and angular heterogeneity, despite explaining less variance—findings that align with previous observations in legumes [49].

Taken together, these predictors represent the three fundamental pillars of yield: early vigor, photosynthetic efficiency during critical phases, and canopy architecture. This combination explains both their statistical stability and the model’s capacity to capture yield variability at the plant scale [47].

4.4. Methodological Contribution and Robustness of the Approach

This study presents a methodological framework integrating Elastic Net, PCA, and bootstrap-based stability selection, specifically designed to address the high multicollinearity typical of spectral indices. This strategy ensured (i) statistical robustness by controlling overfitting through regularization and cross-validation; (ii) parsimony by retaining only stable predictors with physiological relevance; and (iii) flexibility by comparing complementary analytical pathways.

The convergence of Elastic Net toward a Ridge solution (α = 0) confirms the suitability of penalization methods that preserve groups of correlated variables in phenotyping contexts. The proposed framework therefore provides a replicable and statistically sound approach for modeling crops characterized by strong spectral redundancy.

4.5. Limitations, Practical Implications, and Future Perspectives

Although this study was conducted under non-limiting nitrogen conditions to control nutrient-related variability and ensure internal validity, it is well established that nutrient stress alters canopy optical and structural responses [50]. Several studies have demonstrated that vegetation indices (including NDVI and narrowband derivatives) and structural proxies respond differently under nitrogen deficiency [51,52], which may enhance the sensitivity of certain spectral indices and potentially modify the relative importance of predictors in yield models.

While the experiment was carried out under controlled nitrogen conditions to isolate the structural and physiological determinants of yield, the proposed methodological framework is inherently adaptable to variable nutrient scenarios. Targeted field campaigns along nitrogen gradients—combining UAV-derived spectral data with ground-based structural measurements, such as those from the TRAC system—would enable the retraining and validation of predictive models under nutrient stress. Under such conditions, shifts in the relative importance of spectral and structural variables—particularly indices sensitive to chlorophyll concentration (e.g., NDVI, FAPAR)—could be evaluated to identify the most responsive predictors. This adaptability underscores the framework’s potential to extend beyond idealized conditions, supporting genotype assessment and precision management across diverse agro-environmental contexts.

The model demonstrated consistent performance but remains subject to several constraints. The sample size (n = 101) and the model’s dependence on local climatic, management, and phenological conditions limit its direct extrapolation to other contexts. Furthermore, the analysis focused exclusively on spectral and structural canopy attributes, without incorporating physiological or biochemical variables that also influence yield. Therefore, extending the approach to other regions, seasons, or management practices will require additional validation across diverse agro-environmental settings.

Additionally, the experimental spacing (1.0 × 1.5 m) was intentionally designed to facilitate individual-level canopy measurements using the TRAC system and UAV sensors, minimizing canopy overlap and shading among adjacent plants. This configuration enabled precise structural and radiative characterization of each plant but prevented full canopy closure, resulting in lower vegetation density than in typical production fields. While this design enhanced internal validity and measurement precision, it may limit the direct extrapolation of absolute canopy metrics (e.g., NDVI, FAPAR) to commercial planting densities. Nonetheless, the physiological relationships identified remain valid, and the methodological framework can be readily adapted to conventional field configurations for validation under dense canopy conditions.

Furthermore, the spectral configuration of the MAPIR Survey2 camera represents an additional methodological limitation. Because this sensor captures reflectance only in the red (660 ± 5 nm) and near-infrared (850 ± 10 nm) regions, the analysis was restricted to NDVI as the primary vegetation index. The absence of a red-edge band precluded the computation of indices sensitive to chlorophyll dynamics or canopy nitrogen status (e.g., NDRE, MTCI). Nevertheless, this limitation did not compromise the analytical objectives of the study, as the integration of NDVI with TRAC-derived canopy attributes (PAIe, FAPAR, and Ωe) provided complementary information sufficient to characterize canopy function and explain yield variability at the plant scale. Future applications could benefit from multispectral or hyperspectral sensors incorporating the red-edge region to enhance physiological sensitivity and improve generalizability across environmental and management conditions.

To further evaluate the contribution of each sensing source, an ablation analysis was performed comparing TRAC-only, UAV-only, and combined predictor sets under the same modeling pipeline. Results showed that the TRAC-derived structural metrics alone explained approximately 60% of the variability in grain yield (R2 ≈ 0.60; RMSE ≈ 11.9 g), whereas UAV-derived spectral traits accounted for about 53% (R2 ≈ 0.53; RMSE ≈ 13.7 g). The combined model achieved a similar overall fit (R2 ≈ 0.55) but exhibited the lowest prediction error (MAE ≈ 9.35 g), indicating improved stability and reduced residual variance. These results suggest that structural and spectral information are partially redundant yet complementary, with TRAC providing greater explanatory power and UAV imagery enhancing spatial scalability. Together, they support the robustness and operational applicability of the proposed framework for early yield estimation in tropical bean systems. Overall, this complementary evaluation reinforces that integrating canopy structure and reflectance signals enhances model robustness beyond what either source achieves independently.

Although the experiment was conducted at a single site and on one variety, the controlled nitrogen conditions allowed the isolation of structural and physiological effects with high internal validity. This provides a reproducible baseline for scaling the approach to multi-site trials, additional genotypes, and diverse agro-climatic contexts.

While the TRAC system provided high-precision structural measurements at the individual plant scale, its manual operation represents a major limitation to the scalability of the workflow. This ground-based instrument requires controlled movement around each plant, restricting its applicability in high-throughput phenotyping or large-scale precision agriculture studies. In the present work, TRAC measurements were used as ground-truth references to validate UAV-derived spectral and structural metrics, ensuring the physiological coherence and reliability of the predictors used for modeling. Nevertheless, the manual nature of the system constitutes a scalability constraint that should be addressed in future implementations aimed at achieving higher levels of automation and throughput.

Future advances in canopy phenotyping are likely to benefit from the integration of multispectral imagery with three-dimensional structural information obtained via UAV-mounted LiDAR or Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetry. These technologies enable the generation of canopy height models, volume estimates, and structural proxies comparable to those derived from ground-based instruments (e.g., LAI, FAPAR, and Ωe), but with markedly greater scalability and automation [53,54]. Importantly, this approach retains the principal strength demonstrated in this study—namely, the integration of spectral and structural attributes to overcome the saturation of traditional vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) in dense canopies—while expanding operational efficiency toward a truly high-throughput workflow. The combination of these datasets within a unified modeling framework would facilitate a fully UAV-based, high-resolution phenotyping platform applicable to larger plots and breeding programs. In this context, the present study establishes a calibrated reference framework that can guide the future transfer of structural metrics from ground-based to aerial sensing systems.

The findings have direct implications for both research and agronomic management, as they enable the early identification of genotypes with greater physiological and structural efficiency during critical growth stages. Within the framework of precision agriculture, the incorporation of non-destructive metrics provides a pathway for rapid and non-invasive yield prediction at the plant scale, supporting more timely and informed management decisions. The proposed methodological strategy is also transferable to other short-cycle crops, creating opportunities for application in high-throughput phenotyping programs and diversified production systems. These advances contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), by promoting more efficient production, and SDG 13 (Climate Action), by optimizing resource use in tropical agricultural systems.

By enabling earlier and non-destructive yield assessment, this framework reduces the need for destructive sampling and improves nitrogen and water-use efficiency in smallholder systems. This has direct implications for minimizing input waste and enhancing decision making under resource constraints.

In summary, the parsimonious model developed here stands out as a statistically robust and physiologically consistent tool for yield prediction. Its capacity to integrate a limited number of predictors while maintaining high accuracy positions it as a methodological alternative to more complex and less interpretable approaches. The combination of stability selection, Elastic Net, and PCA also represents a significant methodological contribution to addressing multicollinearity in phenotyping studies. Overall, the results demonstrate the utility of this approach in common bean and provide a strong foundation for its adaptation to other agricultural systems. In this sense, the framework extends beyond the bean case and emerges as a tool to support agricultural sustainability in broader international contexts.

While this study focused on integrating representative spectral and structural variables to preserve model interpretability and physiological coherence, future work could benefit from incorporating additional vegetation indices and more advanced algorithms. Complementary indices sensitive to canopy chlorophyll content, photochemical reflectance, and structural heterogeneity (e.g., NDRE, GNDVI, MCARI, or PRI) could capture aspects of canopy function not fully represented by NDVI and FAPAR. Likewise, the application of nonlinear and ensemble learning methods—such as Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, or Gradient Boosting—may further enhance predictive performance as larger and more heterogeneous datasets become available. The present framework therefore provides a consistent and physiologically grounded baseline upon which future methodological developments can be built.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a parsimonious model composed of six spectral and structural predictors explained approximately 72% of the variation in common bean yield under optimal fertilization conditions. This result reflects a balance between statistical simplicity, selection stability, and physiological interpretability, reinforcing the robustness and relevance of the proposed approach.

The selected predictors capture key physiological mechanisms associated with early vigor, radiation-use efficiency, and canopy structure, which collectively determine yield potential at the plant scale.

Methodologically, the combination of Elastic Net regularization, PCA, and bootstrap-based stability analysis provided a robust framework for minimizing multicollinearity and enhancing model reproducibility.

In practical terms, the findings enable early and non-destructive estimation of bean yield, supporting decision making in precision agriculture. The implemented methodology—integrating multispectral UAV data with structural canopy metrics—constitutes a phenotyping strategy capable of quantifying crop traits at the individual-plant scale and is transferable to other agricultural systems with comparable phenology. Beyond its predictive performance, the framework facilitates more efficient resource allocation and supports climate-resilient agriculture, particularly in small- and medium-scale production contexts.

In conclusion, the parsimonious model not only maintains a competitive level of accuracy and stability but also stands out as a robust and transparent alternative to more complex approaches. This methodological framework represents a significant contribution to non-destructive phenotyping and offers a replicable pathway for anticipating yield and optimizing site-specific management in common bean and other short-cycle crops. Ultimately, this work advances the principles of sustainable development by promoting efficient resource use, data-driven decision making, and climate-resilient agricultural practices aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210066/s1, Table S1: Data dictionary describing all predictor and response variables used in the modeling framework. Each entry includes the variable abbreviation, full description, measurement unit, phenological stage (R6, R7, R8), and data source (UAV-derived, TRAC-measured, or field-observed). This table provides essential metadata for reproducing the analysis and ensuring transparent variable interpretation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.E.S.; methodology, N.E.S. and J.G.; software, J.G.; validation, N.E.S., J.G. and D.F.L.; formal analysis, N.E.S. and J.G.; investigation, N.E.S. and J.G.; resources, D.F.L.; data curation, J.G. and N.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.S.; writing—review and editing, J.G. and D.F.L.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, N.E.S.; project administration, N.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Universidad del Quindío (100016837).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable participation of the students from the Seminario courses (2024-II and 2025-I), whose contributions supported the development of this work. The authors also thank Jonnathan Castillo for his technical assistance. No generative AI tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| W_P | Weighted path length |

| K_MEAN | Mean extinction coefficient |

| GAP_FRACTION | Gap fraction |

| OMEGA_E | Clumping index (Ωe) |

| PAI_E | Plant Area Index |

| LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| FAPAR | Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation |

| CANOPY_AREA_m2 | Projected canopy area (m2) |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| CANOPY_HEIGHT_m | Maximum canopy height (m) |

| YIELD_g | Grain yield (g) |

References

- Chawade, A.; Van Ham, J.; Blomquist, H.; Bagge, O.; Alexandersson, E.; Ortiz, R. High-throughput field-phenotyping tools for plant breeding and precision agriculture. Agronomy 2019, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Abouelghar, M.; Belal, A.A.; Saleh, N.; Yones, M.; Selim, A.I.; Amin, M.E.S.; Elwesemy, A.; Kucher, D.E.; Maginan, S.; et al. Crop Yield Prediction Using Multi Sensors Remote Sensing (Review Article). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Sp. Sci. 2022, 25, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Fei, S.; Li, L.; Jin, Y.; Liu, P.; Rasheed, A.; Shawai, R.S.; Zhang, L.; Ma, A.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Stacking of Canopy Spectral Reflectance from Multiple Growth Stages Improves Grain Yield Prediction under Full and Limited Irrigation in Wheat. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, H.J.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, J.H.; Chang, S.; Kwon, D.; Im, W.J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, I.H.; Lee, M.J.; Hwang, W.H.; et al. Canopy-Level Rice Yield and Yield Component Estimation Using NIR-Based Vegetation Indices. Agriculture 2025, 15, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, S.A.; Madolli, M.J.; García-Caparrós, P.; Ullah, H.; Cha-um, S.; Datta, A.; Himanshu, S.K. Advancements in UAV remote sensing for agricultural yield estimation: A systematic comprehensive review of platforms, sensors, and data analytics. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 37, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabed, M.A.; Azmi Murad, M.A. Crop yield prediction in agriculture: A comprehensive review of machine learning and deep learning approaches, with insights for future research and sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D.; Duan, F.; Wu, Q.; Lai, Y.; Qi, J.; Xiong, S.; Qiao, H.; Ma, X.; et al. Plant Phenomics Exploring the depth of the maize canopy LAI detected by spectroscopy based on simulations and in situ measurements. Plant Phenomics 2025, 7, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, B.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Improvement of FAPAR Estimation under the Presence of Non-Green Vegetation Considering Fractional Vegetation Coverage. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, R.A.F.; Zhou, G.; Tian, C.; Tan, Y.; Jing, G.; Jiang, H.; Obaid-ur-Rehman. A Systematic Review of Radiative Transfer Models for Crop Yield Prediction and Crop Traits Retrieval. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Crusiol, L.G.T.; Chen, R.; Wuyun, D. Estimating Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation of Winter Wheat Based on Simulated Sentinel-2 Data under Different Varieties and Water Stress. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravia, D.; Valqui-Valqui, L.; Salazar, W.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Barboza, E.; Porras-Jorge, R.; Injante, P.; Arbizu, C.I. Yield Prediction of Four Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Cultivars Using Vegetation Indices Based on Multispectral Images from UAV in an Arid Zone of Peru. Drones 2023, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu, A.; Florea, C.; Ivanovici, M.; Racoviteanu, A. NDVI and Beyond: Vegetation Indices as Features for Crop Recognition and Segmentation in Hyperspectral Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Daloye, A.M.; Erkbol, H.; Fritschi, F.B. Crop monitoring using satellite/UAV data fusion and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kaur, S.; Joshi, D.R.; Iboyi, J.; Dar, E.; Sharma, L.K.; Singh, H. Estimating cotton biomass and nitrogen content using high-resolution satellite and UAV data fusion with machine learning. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J. UAV Remote Sensing Prediction Method of Winter Wheat Yield Based on the Fused Features of Crop and Soil. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Zhai, W.; Mao, B.; Chen, Z. Precision estimation of winter wheat crop height and above-ground biomass using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery and oblique photoghraphy point cloud data. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1437350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, S.; Ruiz, H.; Jung, J.; Adams, T. UAV-Based Phenotyping: A Non-Destructive Approach to Studying Wheat Growth Patterns for Crop Improvement and Breeding Programs. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovac, A.; Bezdan, A.; Moravcevic, A.; Djurovic, N.; Cosic, M.; Benka, P. Correlation between Ground Measurements and UAV Sensed Vegetation Indices for Yield Prediction of Common Bean Grown. Water 2022, 14, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.S.; Silva, C.A.A.C.; Regazzo, J.R.; Sardinha, E.J.d.S.; da Silva, T.L.; Fiorio, P.R.; Baesso, M.M. Performance of Machine Learning Models in Predicting Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Crop Nitrogen Using NIR Spectroscopy. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.S.; Singh, K.D.; Balasubramanian, P.; Wang, H.; Natarajan, M.; Ravichandran, P. UAV-Based LiDAR and Multispectral Imaging for Estimating Dry Bean Plant Height, Lodging and Seed Yield. Sensors 2025, 25, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi, A.; Zero, E.; Sacile, R.; Trinchero, D.; Fossa, M. Smart Sensors and Smart Data for Precision Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, X. Precision Agriculture and Water Conservation Strategies for Sustainable Crop Production in Arid Regions. Plants 2024, 13, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, T.; Chen, J.; Li, A. Continuous Leaf Area Index (LAI) Observation in Forests: Validation, Application, and Improvement of LAI-NOS. Forests 2024, 15, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Burgess, A.J. Casting light on the architecture of crop yield. Crop Environ. 2022, 1, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanta, S.; Haaning, A.; Dobbels, A.; O’Neill, R.; Hofstad, A.; Virdi, K.; Katagiri, F.; Stupar, R.M.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Lorenz, A.J. Variation in shoot architecture traits and their relationship to canopy coverage and light interception in soybean (Glycine max). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Cihlar, J. Plant canopy gap-size analysis theory for improving optical measurements of leaf-area index. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarez, V.; Duthoit, S.; Baret, F.; Weiss, M.; Dedieu, G. Estimation of leaf area and clumping indexes of crops with hemispherical photographs. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammi, S.A.; Huang, Y.; Feng, G.; Tewolde, H.; Zhang, X.; Jenkins, J.; Shankle, M. Application of UAV Multispectral Imaging to Monitor Soybean Growth with Yield Prediction through Machine Learning. Agronomy 2024, 14, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAT. Sistema Estándar Para la Evaluación de Germoplasma de Frijol; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, F.; Gepts, P.; Lopez, M. Etapas de Desarrollo de la Planta de Fríjol. In Frijol: Investigación y Producción; López Genes, M., Fernández, O.F., van Schoonhoven, A., Eds.; Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD) & Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT): Cali, Colombia, 1985; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Qian, X.; Xu, Y.; Xie, D. Retrieval of the fraction of radiation absorbed by photosynthetic components (FAPARgreen) for forest using a triple-source leaf-wood-soil layer approach. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Beasley, G.; Jung, S.H. LASSO and Elastic Net Tend to Over-Select Features. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.A.; Richards, S.A.; Brook, B.W. Parsimonious model selection using information theory: A modified selection rule. Ecology 2021, 102, 34272730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Khot, L.R.; Espinoza, C.Z.; Jarolmasjed, S.; Sathuvalli, V.R.; Vandemark, G.J.; Miklas, P.N.; Carter, A.H.; Pumphrey, M.O.; Knowles, R.R.N.; et al. Low-altitude, high-resolution aerial imaging systems for row and field crop phenotyping: A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 70, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]