Abstract

Against the accelerating of global climate change and carbon neutrality transitions, energy price volatility exerts complex effects on the employment dimension of economic sustainability through both industrial and agricultural channels as intermediaries. This study employed a mixed-frequency vector autoregression model to statistically analyze the weekly prices of four major industries and 24 sub-markets in China. The main outcome was the urban unemployment rate in China, and it was verified against the urban unemployment rates in 31 cities and the unemployment rates by age group (YUR/LUR). The study investigated the employment dimension of economic sustainability. Energy and energy metal prices represent the energy transition, while food and industrial goods prices characterize the intermediary linkages. Unemployment rates serve as the employment dimension of economic sustainability. The findings reveal bidirectional interactions and heterogeneous transmission mechanisms between prices and unemployment: energy prices exhibit weaker direct links to unemployment, partly influenced by demand inelasticity and policy adjustments; agricultural products face more persistent impacts, reflecting policy interventions and demand constraints; chemical products demonstrate the highest sensitivity and fastest response to unemployment shocks; metals show significant internal variations, with sub-market-level impacts being more pronounced yet shorter-lived. These insights advance climate and energy economics by guiding low-carbon transition policies, optimizing resource allocation, and managing energy market risks for resilient economic sustainability.

1. Introduction

Against the intensifying of global climate change and the ongoing advancement of the “carbon neutrality” strategy, price volatility in energy and energy metals—which underpin the energy transition—has drawn increasing attention. These fluctuations impact production capacity, investment, and employment through industrial energy consumption and key metal input costs, while affecting agricultural output and food prices via fuel and fertilizer expenses. Consequently, they influence labor market resilience and the overall economic performance. Since the millennium, China’s bulk commodity market has developed rapidly, forming a complete industrial chain and a huge industrial scale [1,2] and absorbing a large number of employed people. However, in recent years, under multiple shocks such as COVID-19 and geopolitical conflicts, the fluctuations of China’s bulk commodity prices, particularly those in energy-related markets, have significantly intensified [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This high volatility increases the production costs in the manufacturing industry, leading to delays or even postponement of production decisions [10], which in turn triggers the risk of job reduction. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate structure in China has also undergone complex changes. When the unemployment rate rises, residents’ income is impacted, and the demand for bulk commodities weakens, which in turn affects the market prices of bulk commodities. This cycle chain makes the unemployment rate not only a reflection of the prosperity of the labor market, but also a key outcome variable for measuring labor market sustainability. However, concrete evidence remains lacking regarding the specific transmission mechanisms linking energy and energy metal prices to unemployment rates—particularly how these mechanisms operate through industrial and agricultural intermediary pathways to impact the employment dimension of economic sustainability. The sudden and uncontrollable nature of commodity price fluctuations further underscores the urgent value of studying this relationship within the context of energy transition, providing policy foundations for achieving stable employment and sustainable growth during the low-carbon transformation process.

Against this backdrop, we use energy and energy–metal prices to proxy the intensity of the energy transition and measure the employment dimension of economic sustainability through the urban surveyed unemployment rate. Economic sustainability is a multidimensional concept, and in this study, we operationalize its employment dimension using the urban surveyed unemployment rate. Commodity markets are conventionally divided into four sectors—metals, agricultural products, chemicals, and energy. Owing to differences in technological structure, demand elasticity, and policy regimes, the transmission from prices to employment is expected to be heterogeneous across these sectors [11]. At present, given the significant position of the crude oil market in the economy [12,13,14,15,16], research on the relationship between unemployment rate and commodity prices mainly focuses on the energy market; [17,18,19,20,21,22], respectively, studied the impact of oil price fluctuations on domestic unemployment rates in the United States, China, Canada, and Russia. The comparison showed that the unemployment rates of countries with different international statuses and geopolitical situations responded differently to oil price fluctuations. In addition to oil price fluctuations, the research by Fæhn et al. [23] and Fernandez [24] indicates that price fluctuations in clean energy industries such as natural gas and the mining industry are all related to employment rates to a certain extent. However, most existing studies concentrate on single industries or isolated sub-markets, offering limited cross-sector comparisons and little identification of the mechanisms along the causal chain in which energy and energy–metal prices propagate through industrial and agricultural intermediaries to affect employment and, by extension, economic sustainability. Evidence that explicitly incorporates energy metals within the energy-transition context and evaluates them alongside other sectors is especially scarce. Accordingly, situated within the broader logic of the energy transition, this paper examines the bidirectional relationship and heterogeneity between price volatility and unemployment across four major sectors and their sub-markets, and, based on the resulting evidence, discusses the implications for employment stability and sustainable economic development in China [25].

While the Phillips curve is a widely recognized framework that illustrates the inverse relationship between inflation (price fluctuations) and unemployment, we focus on how energy price fluctuations specifically affect unemployment through two intermediary channels—industrial and agricultural. Unlike the general framework of the Phillips curve, which deals with the broader inflation–unemployment trade-off, our study disaggregates price shocks by sector and examines their heterogeneous pass-through to overall urban unemployment Nevertheless, we acknowledge the relevance of the Phillips curve in explaining short-term trade-offs between price and unemployment, and our findings provide additional insights into this relationship within the context of the energy transition. This is consistent with broader macroeconomic theories but focuses on sector-level implications. Standard search-and-matching and labor-demand frameworks imply that unemployment dynamics reflect the interplay between the separation rate and the job-finding rate. Energy and energy–metal price shocks affect these margins through three well-known channels concentrated in urban industrial and service sectors: (i) a cost channel—higher input and energy costs shift labor demand left, (ii) a demand channel—real-income and profitability compression lowers final demand and hiring, and (iii) an uncertainty channel—greater volatility increases the option value of waiting, depressing vacancies and matches. This theoretical mapping motivates the use of the urban surveyed unemployment rate as our baseline measure for the employment dimension of sustainability in the urban segment of the labor market.

Existing studies predominantly employ co-frequency modeling at monthly or quarterly intervals, typically aggregating daily or weekly commodity prices into lower frequencies. This approach results in the loss of high-frequency information and introduces time aggregation bias. To make full use of high-frequency price information and avoid data loss, we adopted the Hybrid Frequency Vector Autoregression (MF-VAR) model to reveal the connection between the two [26]. This model effectively captures the dynamic transmission mechanism of short-term price fluctuations on the unemployment rate by allowing high-frequency variables to have heterogeneous effects within low-frequency cycles, and is more explanatory than the traditional single-frequency VAR model.

Given the heterogeneity in the price–unemployment relationship, this paper first examines the relationship between price changes in four major industries—metals, agricultural products, energy, and chemicals—and China’s unemployment rate at the macro level: chemical products respond most rapidly and sensitively to unemployment shocks, energy market prices exhibit greater stability, while agricultural product prices show the strongest volatility. Further disaggregation of these four industries into 24 sub-markets reveals significant divergence in how different sub-markets within the metals and energy sectors respond to shocks. Finally, comparing sub-market responses with their corresponding sectors reveals that the relationship between sub-market prices and unemployment largely mirrors that of the broader sectors. However, sub-markets exhibit more pronounced responses, higher volatility, and shorter duration of fluctuations.

Our focus is strictly on the employment dimension of economic sustainability as it relates to urban labor-market stability. Energy and energy–metal price shocks are global in scope, yet their transmission primarily operates through urban industrial and service sectors (via cost, demand, and uncertainty channels). We therefore operationalize the employment dimension with the national urban surveyed unemployment rate and interpret our results as pertaining to the urban segment of the labor market, rather than the whole economy. The commodity price indices are national in scope; hence we discuss scale alignment explicitly and report robustness to CUR and age-specific URs.

The innovative contributions of this article lie in establishing an analytical framework centered on energy and energy metal prices within the context of energy transition. It elucidates how prices influence unemployment through industrial and agricultural channels, using urban survey unemployment rates as an employment dimension indicator for economic sustainability. The study systematically compares four major industries and twenty-four sub-markets while identifying bidirectional transmission between prices and unemployment. Methodologically, it employs a mixed-frequency vector autoregression (MF-VAR) model that integrates weekly prices and monthly unemployment rates without requiring weekly unemployment data, yielding results with greater explanatory power than traditional single-frequency VAR models. Theoretically, this study tightly links energy price volatility with economic sustainability, refines the identification of mechanisms through which price shocks affect employment via industrial channels, and expands the application of mixed-frequency modeling in labor market research. Practically, this study provides actionable policy guidance for employment stabilization and risk management during low-carbon transition [27].

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 constructs the theoretical framework and proposes research hypotheses; Section 3 introduces the MF-VAR model and data; Section 4 presents empirical results and conducts analytical discussions; Section 5 summarizes conclusions and offers policy recommendations.

2. Mechanism

From a theoretical perspective grounded in price volatility and uncertainty, and integrating industrial and agricultural channels, this study poses two guiding questions—what is the short-to-medium-term relationship between energy price fluctuations and unemployment, and through which industrial and agricultural pathways do energy price shocks transmit to employment—and formulates testable hypotheses accordingly. First, we expect rising commodity prices to reduce unemployment in the short run via margins, capacity utilization, and hiring, while higher unemployment compresses household income and demand and subsequently lifts most prices with a longer lag, implying asynchronous timing in which prices adjust faster than unemployment feeds back. Second, we expect clear sectoral heterogeneity: chemicals respond fastest and most strongly; energy remains comparatively stable owing to demand inelasticity and policy buffering; agricultural effects are more persistent due to food-demand rigidity and production cycles; metals occupy an intermediate position with pronounced within-sector variation. Third, at the sub-market level, response directions align with their parent sectors but display greater magnitudes, earlier onsets, and shorter durations. These research questions and hypotheses are operationalized as propositions and evaluated using impulse responses from a mixed-frequency vector autoregression.

Different industries of bulk commodities have distinct characteristics. For instance, the agricultural products and metal industries are labor-intensive, the chemical products industry is knowledge-intensive, and the energy industry leans more towards technology and capital. The price fluctuations in labor-intensive industries are closely related to workers and labor force. Knowledge-intensive industries have higher requirements for employees’ professional skills and learning abilities. Although technology-intensive industries have higher requirements for employees’ knowledge reserves, their employment is also more stable. Different characteristics lead to different transmission relationships between industries and unemployment rates.

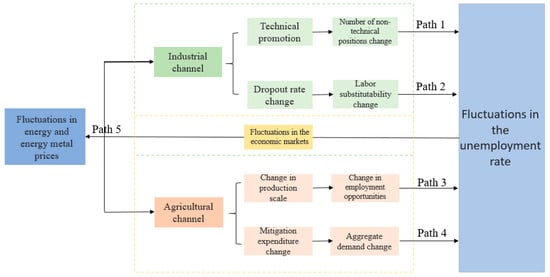

Figure 1 presents two industrial channels linking energy and energy metal price fluctuations to unemployment rates: the industrial channel and the agricultural channel [11]. In the industrial channel, Path 1 reveals that after scale expansion to a certain extent, automation replaces low-skilled workers through technological unemployment [28,29], Path 2 reveals that import fluctuations cause market instability and economic recession [30,31,32], an increase in the dropout rate of students [33], a decrease in the skill reserves of employees, and an increase in substitutability; in the agricultural channel, Path 3 reveals that the increase in import costs leads to a reduction in production scale under a fixed budget, increasing the risk of unemployment [34,35,36,37], while the decline in costs is conducive to expansion and job creation; Path 4 reveals that the intensification of uncertainty prompts enterprises to reduce economic activities, increases the economic vulnerability of households [38,39,40], causes GDP contraction, and raises the cyclical unemployment rate. On the contrary, Path 5 reveals that unemployment reduces household income and consumption willingness [25,41], suppresses commodity demand and prices, while informal employment exacerbates macroeconomic instability [42]. This provides a theoretical basis for analyzing the influence between commodity prices and the unemployment rate. When the price of a certain type of bulk commodity fluctuates, the related industry will become the primary response target and react to the price change. Due to the long-term connections among the commodity markets, other industries will be affected to some extent by the fluctuations of their own industries, and then be linked to the unemployment rate through the external environment. Moreover, the reactions of different industries vary.

Figure 1.

Mechanism and path of interaction between commodity market price and unemployment rate.

3. Data and Models

3.1. Data and Descriptive Statistics

This article defines economic sustainability as an economy’s capacity to maintain growth quality and social employment resilience in the face of exogenous shocks, encompassing at least the dimensions of employment and short-term macroeconomic stability. Given data availability and clarity of transmission channels, we measure the employment dimension using the urban surveyed unemployment rate. Considering that energy price shocks primarily affect short-term equilibrium through demand and cost channels, we dedicate subsequent discussion to the short-term stability dimension, interpreting results within the context of short-to-medium-term dynamics rather than long-term structural equilibrium. We focus on the employment dimension; short-run output and price stability are discussed qualitatively and left for future empirical extensions.

Based on commodity classifications, this study focuses on non-ferrous metals, agricultural products, energy, and industrial price indicators sourced from the CSMAR Economic and Financial Research Database. Specifically, the non-ferrous metals futures price index, agricultural products price index, energy price index, and chemical price index are selected. Raw prices are daily–frequency data. Weekly prices are first calculated using trading-day weighting, then transformed into weekly price change indices via logarithmic first-order differencing. To align with monthly unemployment rates within a mixed-frequency framework, unemployment data undergoes no interpolation; frequency differences are addressed solely through model estimation. Commodity prices are national-level indices, whereas unemployment is the national urban rate; we therefore interpret our results as pertaining to urban labor-market stability, and we show robustness to alternative unemployment measures.

At the sub-market level, this study retrieved daily closing prices for active contracts across 24 Chinese sub-markets from the Wind Financial Information Database: metal industry segment data originated from the Shanghai Futures Exchange; agricultural and chemical industry segment data primarily came from the Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange and Dalian Commodity Exchange; energy industry segment price data were sourced from the Dalian Commodity Exchange and Shanghai Futures Exchange. Daily prices are aggregated weekly to form weekly series. If only some trading days are missing within a week, calculations are based on available trading days; observations with no transactions for the entire week are not interpolated. Outliers are limited to mechanical errors. Economic extreme fluctuations caused by policy events, market price limits, or liquidity contraction are retained as valid information. For frequency mixing purposes, the last four trading weeks of each month are retained; cross-month weeks are categorized under the month of the final trading day. Active contract prices are directly used to construct weekly series without price splicing adjustments. All prices are denominated in Renminbi. The exchange calendar follows China’s statutory holiday schedule. The unemployment rate utilizes monthly national urban survey unemployment data from the National Bureau of Statistics for February 2018 to September 2022. The correspondence between the four major industries and sub-markets is detailed in Table 1. These are consolidated under a unified time index for subsequent empirical analysis.

Table 1.

Classification of Industries and Corresponding Markets.

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of all variables. The data used have undergone logarithmic difference processing of the original data. The ADF test and PP test results of each data are roughly the same, showing significant stationarity. The Jarque–Bera test (JB) strongly rejects the normal distribution of each index. Panel A shows that the unemployment rate of the urban group is higher than that of the total group, and the unemployment rate of the young group is much higher than that of the middle-aged group, indicating that unemployment is mainly concentrated among young people in urban areas. Panel B and Panel C show that both industries and sub-markets exhibit a pattern of excessive skewness. Panel B indicates that the mean of the energy price change index is relatively large, at 0.43%. The standard deviation of the agricultural product price change index is the smallest among the four industry price change indices, indicating that its price is the most stable. Represented by the standard deviation, the changes in the four industry indices show a certain degree of positive skewness. Panel C shows that the JB test of the price change indices of all major sub-markets strongly rejects the hypothesis of normal distribution of uncertainty fluctuations, presenting a more volatile pattern compared to the overall sub-market. The means of the four chemical market price change indices are generally negative, indicating that their prices are mostly in a downward trend.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

3.2. Econometric Framework

In order to match low-frequency (monthly) urban population unemployment rate data in China with high-frequency (weekly) commodity price index data, and to preserve the integrity and effectiveness of low-frequency data as much as possible, we chose the Mixed Frequency Vector Autoregressive (MF-VAR) model to analyze the data to explore the relationship between commodity prices and unemployment rate.

We utilized the Motegi and Sadahiro [26] MF-VAR model, which consisted of monthly unemployment rates and weekly price indices. Let t ∈ {1, …, 12} represent the month, y ∈ {2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022} represent the year, j ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4} represent the number of weeks in that month. The week count in this paper is presented in the form of reciprocal, such as when j = 1, indicating the penultimate week of the month, which is the last week of the month. Ut,y represent the monthly urban unemployment rate in China, Pj,t,y represent the weekly commodity price index, for example, P1,2,2018 represents the first week commodity price index in February 2018, and P2,11,2019 represents the second week commodity price index in November 2019.

Pj,t,y is converted from daily data PDd,j,t,y, where d ∈ {1, …, 7} represents the number of days per week, for example, PD5,3,7,2019 represents the Friday of the third week in July 2019. From this, it can be seen that the conversion relationship between weekly data and daily data is:

We pay more attention to the changes in prices and use price differences as our variables:

Therefore, the MF-VAR model, which includes monthly unemployment rate data and weekly price index data, is constructed as follows:

Or expressed as:

In this paper, the results are presented in the form of impulse response functions. When a unit shock is input, a response output will be obtained to test whether the influence between commodity prices and unemployment rates is positive or negative, and the magnitude of the interaction between the two variables in the MF-VAR system in this paper is examined through its fluctuation amplitude. In this paper, the impulse response function with a 95% confidence interval is constructed through the above model. The confidence intervals are based on the use of least squares estimators Ãk,h constructs each horizon h = 0, 1, …, 6 through parameter bootstrapping.

4. Empirical Results

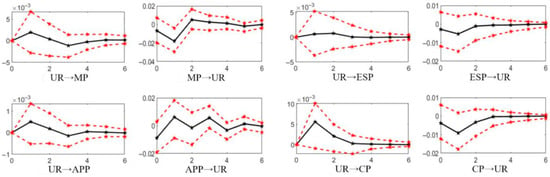

This section analyzes the dynamic interaction mechanism between the commodity price change index XP and the unemployment rate UR based on the impulse response function (IRF). Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the IRF results of the four major industries and 24 sub-markets under the MF-VAR model. Each panel represents the response of one variable to the shock of another variable over a 6-period horizon. The black line represents the impulse response, and the red dashed line likely indicates the confidence interval. The x-axis represents the time horizon (in periods) over which the impulse response is evaluated. The range is from 0 to 6, where the values indicate the time periods after the shock has occurred. The y-axis represents the magnitude of the response in terms of change in the unemployment rate (UR) or other economic variables. This value is likely shown in units of percentage change or another relevant scale. The exact units depend on the specific commodity or variable being analyzed. Among those figures, UR→XP represents the price change brought about by the unemployment rate shock, and XP→UR represents the response relationship of the unemployment rate in the face of the price change shock. The two jointly confirm the significance of the bidirectional transmission relationship. To systematically reveal the heterogeneity of industries and sub-markets, the analysis follows a logical thread from macro to micro: firstly, make a horizontal comparison of the response differences among the four major industries of metals, agricultural products, energy, and chemicals; next, conduct a longitudinal analysis of the response relationships among different markets in each industry; finally, analyze whether the changes in different sub-markets within the industry are consistent with the overall changes in the corresponding industry, and explore the homogeneity and heterogeneity of the influence relationship between different commodity markets and the unemployment rate.

4.1. Industry Conclusion Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the corresponding relationship between the commodity price change index and unemployment rate. Observing the UR→XP results, the overall response trend of prices across the four major industries under unemployment shocks is largely consistent: an initial upward surge, a decline at h = 1, mid-term fluctuations, and eventual stabilization. However, the magnitude of these changes diverges significantly: chemical products are most sensitive to unemployment shocks, while energy remains the most stable. This divergence stems from sector-specific characteristics—the chemical industry features long supply chains with numerous intermediate stages, making it highly sensitive to labor cost fluctuations. Rising unemployment transmits downward wage pressure to production costs, triggering sharp price adjustments. In contrast, the energy sector effectively buffers the transmission intensity of unemployment shocks due to its inelastic demand and robust policy regulation.

Observing the results from XP→UR, changes in agricultural product prices have the longest-lasting impact on unemployment rates, while fluctuations in metal industry prices exert the strongest influence on unemployment rates. Specifically, upward movements in metal, energy, and chemical prices all correspond to short-term declines in unemployment rates, reaching their maximum negative effect at h = 1 before stabilizing. This indicates that rising industrial prices can temporarily stimulate labor demand by boosting corporate profits and capacity utilization, thereby reducing unemployment. However, for the agricultural sector, although unemployment initially drops briefly, it rebounds sharply at h = 2 and continues to fluctuate positively through h = 5. This stems from the price rigidity of agricultural products as essential goods for people’s livelihoods—price increases squeeze household real income, forcing families to reduce consumption of industrial goods, indirectly triggering manufacturing job cuts and forming employment suppression. This aligns with evidence from the oil-agriculture linkage and real income channels [12,15]. Furthermore, fluctuations in metal industry prices exerted the most significant impact on unemployment rates, nearly doubling the average effect of other industries. Although metal prices return to stable values in the medium term, they exhibit slight fluctuations in the mid-to-late stages. This reflects how price volatility in metals—as foundational industrial raw materials—rapidly propagates through supply chains to affect employment. Energy prices exhibit lower direct elasticity with unemployment but share a consistent directional relationship, aligning with findings on transnational energy shocks and employment [19,20].

Figure 2.

Based on the impulse response function of mixed frequency VAR, the weekly price change index MP of metals, the weekly price change index APP of agricultural products, the weekly price change index ESP of energy, the weekly price change index CP of chemical products and the unemployment rate UR are plotted in the weekly range h = 0, 1, … The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times. The black solid line is the point estimate; red dashed lines are 95% bootstrap confidence bands; asterisks (if shown) mark horizons where the null of zero response is rejected (p < 0.10, p < 0.05, p < 0.01). The definitions of MP/ESP/APP/CP follow the text.

4.2. Sub-Market Conclusions Analysis

4.2.1. Different Sub-Markets in the Metal Industry

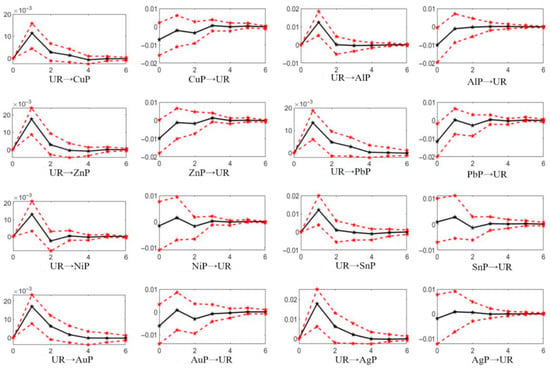

Figure 3 shows the response relationship between the price change index of the eight sub-markets in the metal industry and the unemployment rate. According to UR→XP, it can be found that when the social unemployment rate increases, the price responses of the eight metal sub-markets remain basically consistent. Before the unemployment rate changes, there will be a surge in price increases, which basically subside at the same rate. In the middle of the fluctuation, the fading of the craze will not cause the commodity prices to directly return to their initial positions, but will continue to fluctuate downward to a certain extent, with the prices falling below the original values. Ultimately, it gradually returned to the original state in the later stage of the fluctuation. This mechanism is in line with the sensitivity analysis of metal prices in the relevant research on industrial chain transmission [34,35].

According to XP→UR, it can be concluded that when facing the impact of price fluctuations in these eight sub-markets, the unemployment rate shows different responses in terms of the amplitude and duration of fluctuations under the impact of different metal sub-markets. Firstly, in terms of the fluctuation range, the upward movement of copper, zinc, lead and gold prices corresponds to an immediate decline in the unemployment rate, indicating that the improvement in the prices of basic intermediate goods and highly liquid assets accelerates recruitment and employment through profits and capacity utilization. In the period when the fluctuation occurs, it will increase employment of the labor force, and the short-term employment pull will be stronger. In the face of price fluctuations in metals such as nickel, tin and silver, there will be a slow increase in the early stage, and the number of unemployed people will increase to a certain extent, but the impact will be relatively small, the reason lies in its high demand concentration, being greatly influenced by external demand and technological substitution, and the fact that the supply side is more susceptible to the influence of the mining side, making it difficult for price fluctuations to be simultaneously reflected in domestic employment. The negative effect between aluminum and silver lasts for a relatively short period of time, reflecting the phased nature of the demand for lightweighting and the hedging effect of the financial attributes of precious metals. Secondly, in terms of the duration of fluctuations, the impact on the prices of most metal sub-markets will keep the unemployment rate in a volatile state during the middle stage of the fluctuations, and it will not stabilize until the middle and later stages. The economic significance of this finding lies in the fact that policy tools for stabilizing employment should be differentiated across various commodities: for base intermediates like copper, zinc, and lead, the focus should be on ensuring order stability; for supply-constrained commodities such as nickel and tin, emphasis should be placed on enhancing capacity and import flexibility management; and for precious metals and silver, efforts should be made to strengthen financial stability and the supply of hedging instruments to mitigate the impact of sharp price fluctuations on the labor market.

Figure 3.

Pulse response Function of the Metal Industry Based on mixing VAR. The weekly copper price change index (CuP), aluminum price change index (AlP), zinc price change index (ZnP), lead price change index (PbP), nickel price change index (NiP), tin price change index (SnP), gold price change index (AuP), and silver price change index (AgP) are plotted weekly with the unemployment rate (UR) using Mc-var; the range h = 0, 1, …. The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

4.2.2. Different Sub-Markets in the Agricultural Products Industry

Figure 4 illustrates the interrelationship between price change indices and unemployment rates across seven major agricultural sub-markets. It reveals that the common pattern for UR→XP is a short-term price surge following rising unemployment, followed by a regression at h = 2. However, during the mid-cycle fluctuations, slight variations emerge among different agricultural products. For wheat, cotton, Yellow Soybean 1, and Yellow Soybean 2, prices exhibit greater sensitivity to unemployment shocks and experience prolonged impacts. This stems from the influence of policies such as minimum purchase prices and import quotas on staple grains, key fiber crops, and oilseeds, where inventory management and planting cycles cause shocks to be more delayed and persistent. In contrast, japonica rice, corn, and soybean meal are primarily driven by feed and deep-processing demand, featuring faster inventory turnover and quicker recovery.

According to XP→UR, the unemployment rate’s response to price shocks in different agricultural product sub-markets is basically the same. The unemployment rate first shows a negative feedback at h = 0, rebounds to the origin at h = 1, and has a small negative fluctuation at h = 2, 3. This indicates that as soon as there is an increase in agricultural product prices, employment will increase immediately, the unemployment rate will drop rapidly, and there will be more or less fluctuations in the medium term. Eventually, it will stabilize in the later period. The economic implications of this change lie in the fact that employment stability policies need to be coordinated with tools for stabilizing supply and prices. On the one hand, measures such as orderly purchase and storage and credit support should be adopted to alleviate the fluctuations in labor demand during the purchase season. On the other hand, targeted subsidies should be provided to alleviate the secondary impact of food price hikes on the employment of low-income groups.

Figure 4.

Impulse response Function of Agricultural Product Industry Based on Frequency Mixing VAR. Mc-var plot of the weekly price change index WP of wheat, the weekly price change index JRP of japonica rice, the weekly price change index COTP of cotton, the weekly price change index YS1P of soybean No. 1, the weekly price change index YS2P of soybean No. 2, the weekly price change index CORP of corn and the weekly price change index SMP of soybean meal with the unemployment rate UR. Set the circumference range h = 0, 1, …. The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

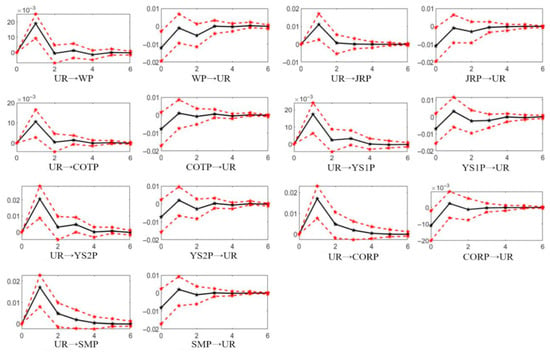

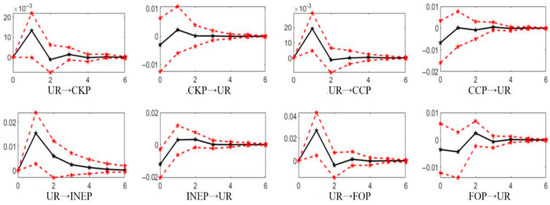

4.2.3. Different Sub-Markets in the Energy Market

Figure 5 shows the interrelationship between the price change index and the unemployment rate of the four major sub-markets in the energy market. According to UR→XP, the fluctuation of the unemployment rate causes relatively high price fluctuations. After the price rises, it will face a rapid decline. When h = 2, a negative shock will occur, falling below the original level, and then it will tend to stabilize in the fluctuation. The previous price increase was mainly due to enterprises replenishing inventories, avoiding risks and rising costs. Later, the price dropped or even fell below the previous level, indicating that the rigidity of energy consumption was strong and the policy adjustment and reserve mechanism offset the impact. However, for the INE crude oil sub-market, when h = 2, the price change is still in a positive reaction. This phenomenon will continue until h = 3, and the price increase brought about by the unemployment rate will have a relatively sustained and stable impact.

According to XP→UR, when the prices of energy sub-markets fluctuate, unemployment rates usually decline in the short term because profits and productivity in sectors such as refining, transportation and infrastructure have improved, leading to a slight increase in employment. However, compared with other sub-markets, the unemployment rate of fuel oil did not immediately return to positive after showing a negative reaction. It remained on a downward trend during the h = 1 stage and did not recover until h = 2. The reason is that it is closely linked to shipping, logistics and industrial fuel, and price changes will support employment for a longer period of time through freight rates and inventory cycles. The economic implications of this change lie in the fact that we not only need to stabilize the pace of reserves and imports to weaken the transmission of large price fluctuations to employment, but also need to provide supporting transportation capacity and financing for varieties with strong transmission, such as fuel oil, to reduce the unnecessary impact of short-term price fluctuations on the labor market.

Figure 5.

The pulse response function of the energy market based on mixed frequency VAR, the weekly price change index CKP of coke, the weekly price change index CCP of coking coal, the weekly price change index INEP of INE crude oil, the weekly price change index FOP of fuel oil and the unemployment rate UR are plotted with the weekly range h = 0, 1, … The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

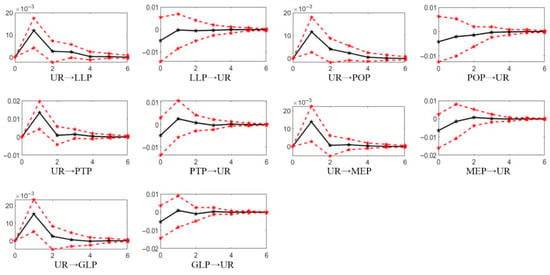

4.2.4. Different Sub-Markets in the Chemical Products Industry

Figure 6 shows the interrelationship between the price change index and the unemployment rate of the five major sub-markets in the chemical products industry. According to UR→XP, when facing fluctuations in the unemployment rate, the prices of each sub-market also showed positive reactions in the early stage, but in the middle and later stages, the prices have all stabilized. The reason for this change lies in the fact that the chemical industry chain is long and energy is the main raw material and power source. Cost changes will be rapidly magnified to the prices of intermediate products. At the same time, inventory and order cycles are short, and the contraction and recovery of enterprises’ employment and production capacity will be quickly reflected in prices. This is consistent with the existing research findings that energy chemical products are highly sensitive to macro shocks According to XP→UR, when the prices of each sub-market fluctuate, the unemployment rate gradually stabilizes after a decrease. However, compared with other sub-markets that quickly recover to the far point when h = 2, the unemployment rate recovers more slowly and smoothly when the price of the polypropylene sub-market fluctuates, and basically stabilizes only when h = 3. Therefore, to stabilize employment and expectations within the chemical industry chain, it is essential to leverage its characteristics of rapid responsiveness and short cycles: during the shock phase, mitigate the excessive transmission of cost and demand fluctuations to labor by ensuring inventory and transportation capacity coordination; during the recovery phase, avoid excessive expansion.

Figure 6.

Impulse Response Function of Chemical Products Industry Based on Mixing VAR. The weekly price change index of LLDPE (LLP), the weekly price change index of polypropylene (POP), the weekly price change index of PTA (PTP), the weekly price change index of methanol (MEP), and the weekly price change index of glass (GLP) and the unemployment rate (UR) were plotted in the Mc-var weekly range h = 0, 1, …. The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

4.2.5. Similarities and Differences Between Sub-Markets and Industrial Responses

By making an overall comparison between Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, it can be seen that, on the whole, the responses of each sub-market to the shock are the same as those of the entire industry. However, the shock response of sub-markets is more volatile than that of the entire industry. That is, when the unemployment rate or prices change, the corresponding response will have a greater upward fluctuation compared to the overall situation, but the duration of the fluctuation is relatively short. Since an industry is composed of various markets and there is mutual influence and interaction among these markets, the overall indicators of an industry are not simply the sum of the indicators of each sub-market, but rather their organic combination. Therefore, industrial indicators have a stronger overall nature than sub-market indicators.

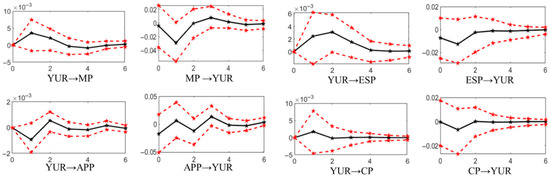

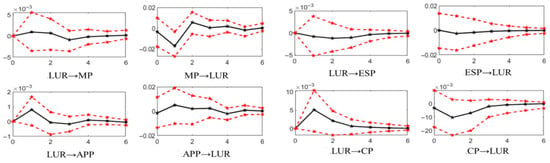

4.3. Heterogeneity of Unemployment Rate

This paper takes the surveyed unemployment rate in Chinese urban areas as an indicator of China’s unemployment rate, discusses the relationship with the index of changes in commodity prices, and finds that there is an interaction between China’s unemployment rate and commodity prices. We continue to use two indices, the Urban Surveyed Unemployment Rate (YUR) for the 16–24 age group and the Urban surveyed unemployment Rate (LUR) for the 25–59 age group in China, to explore whether there is heterogeneity in the relationship between commodity prices and the unemployment rates of different age groups in China.

Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively, show the impulse response functions between the prices of bulk commodities in the industrial dimension and YUR and LUR. By comparing the two graphs, it can be observed that when facing price shocks, the unemployment impact faced by the labor force of the two age groups is roughly the same, indicating that the impact of prices on the unemployment rate does not vary with age. However, when the unemployment rates of the two age groups change, the responses of prices are slightly different. For instance, the responses of agricultural product prices to the two shocks are exactly opposite. When the unemployment rate of young people rises, agricultural product prices show a negative feedback, while the unemployment rate of middle-aged people has a positive impact on agricultural product prices. Overall, however, the reactions of the two were also relatively consistent.

Figure 7.

Based on the impulse response function of mixed frequency VAR, the weekly price change index MP of metals, the weekly price change index APP of agricultural products, the weekly price change index ESP of energy, the weekly price change index CP of chemical products and the surveyed urban unemployment rate YUR of the population aged 16–24 are plotted in the weekly range h = 0, 1, … The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

Figure 8.

Based on the impulse response function of mixed frequency VAR, the weekly price change index MP of metals, the weekly price change index APP of agricultural products, the weekly price change index ESP of energy, the weekly price change index CP of chemical products and the surveyed urban unemployment rate LUR of the population aged 25–59 are plotted in the weekly range h = 0, 1, …. The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

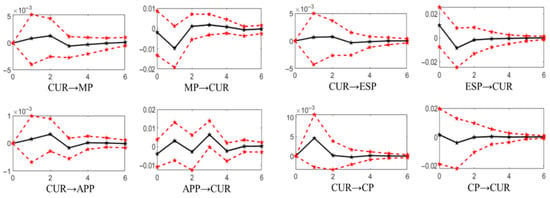

In addition to the three indicators used to describe the unemployment rate in the heterogeneity test, there are other indices for measuring China’s unemployment rate, such as the surveyed urban unemployment rate (CUR) in 31 major cities. This index was newly set up by the Chinese government in 2009 to more accurately and effectively grasp the national unemployment rate. It calculates the unemployment rates of 31 major cities in China. The intensified statistical law enforcement and inspection efforts by the National Bureau of Statistics have ensured the authenticity and reliability of the surveyed unemployment rate data. Therefore, we chose CUR as the indicator of China’s unemployment rate and conducted a MF-VAR model analysis of it with the industrial indicators in the commodity price change index to verify the robustness of our empirical results. The impulse response function is shown in Figure 9. We can observe that there is a relatively obvious interaction between CUR and the prices of various industries in Figure 9, and the mode of interaction is basically consistent with the result when the surveyed unemployment rate of Chinese urban areas is used as the unemployment rate index, which confirms the robustness of our empirical results.

Figure 9.

Based on the impulse response function of the mixed frequency VAR, the weekly price change index MP of metals, the weekly price change index APP of agricultural products, the weekly price change index ESP of energy, the weekly price change index CP of chemical products and the surveyed urban unemployment rate CUR of 31 major cities are plotted in the weekly range h = 0, 1, … The impulse response function (IRF) of 6. The 95% confidence interval was constructed by the parametric bootloader method and repeated 500 times.

5. Discussion

This study shows that fluctuations in energy and energy–metal prices affect employment—and thus the employment dimension of economic sustainability—through two transmission channels. Along the industrial channel, energy and critical metals operate as cost and input factors that alter firms’ margins, capacity utilization, and labor demand. Along the agricultural channel, fuel and fertilizer costs and food prices shape household real income and consumption, which in turn influence employment in agriculture-related and downstream sectors.

Empirically, we document a bidirectional relationship between prices and unemployment with pronounced short-to-medium-term dynamics: chemical prices adjust fastest and most strongly; energy prices are comparatively stable, consistent with demand inelasticity and policy buffering; agricultural prices exert more persistent effects; metals lie between these cases with marked sub-market heterogeneity. These findings align with the Phillips curve framework, which suggests a short-term inverse relationship between inflation (or price fluctuations) and unemployment. In line with existing literature on energy price fluctuations and employment [18,19], our study provides additional insight into how energy prices specifically influence employment through sectoral channels

Methodologically, a mixed-frequency VAR identifies the asynchronous transmission from weekly price changes to monthly unemployment without altering the frequency of the labor-market data, yielding comparable evidence across sectors and sub-markets. This approach addresses an important gap in the literature, where existing models have often struggled to capture short-term dynamics of price fluctuations on employment.

The three operative mechanisms—cost, demand, and uncertainty—are generalizable, making the direction of employment effects via industrial and agricultural sectors transferable across countries. Consistent with international evidence, energy-price shocks typically influence labor demand and unemployment over the short to medium horizon, while the magnitude and duration depend on institutional and structural conditions. The paper offers a reusable analytical framework: elasticities can be re-estimated using country-specific price-formation regimes, labor-market institutions, and trade positions. We note that urban unemployment is used here as the outcome for the employment dimension of economic sustainability; short-run output and price-stability dimensions are not jointly estimated. Hence, external applications should be benchmarked against local indicators such as industrial production or PMI and energy- and food-related CPI or PPI.

While much of the existing literature on price fluctuations analyzes their impact across entire economies or broader sectors, this study focuses specifically on the energy sector and its interactions with agriculture and industry, offering a more granular view of how price shocks propagate through these channels. By using a mixed-frequency VAR model, we are able to capture short-to-medium-term dynamics of these relationships, an area not fully explored in existing research.

This study has limitations. First, the analysis centers on the core price–unemployment nexus; future work could incorporate additional macro controls—interest rates, exchange rates, global economic-policy uncertainty—to better account for confounding influences. Second, although the MF-VAR accommodates mixed frequencies, the monthly cadence of unemployment may miss higher-frequency labor-market adjustments; future research could draw on higher-frequency proxies (e.g., weekly unemployment insurance claims, where available). Despite these caveats, the evidence provides an initial, policy-relevant characterization of how energy and energy–metal price fluctuations propagate to unemployment through sectoral channels, linking price volatility to economic sustainability. Extensions that add multidimensional outcome indicators and higher-frequency labor data, coupled with structural identification and cross-country comparisons, would further test the mechanisms and enhance external validity. Our evidence pertains to urban labor-market dynamics. Extending the analysis to rural labor outcomes or matched regional price exposures is a promising avenue for future work.

6. Conclusions

This paper uses the MF-VAR model to analyze the weekly commodity prices and the monthly urban unemployment rate in China. It explores the interaction between the changes in commodity prices and the unemployment rate from the two dimensions of industry and sub-market. The model indicates that there is a mutual influence relationship between the changes in commodity prices and the unemployment rate. Moreover, there is heterogeneity in the responses between prices and unemployment rates in different industries and sub-markets. The empirical results of this paper are summarized as follows:

Firstly, at the overall level, we have confirmed the bidirectional reinforcing effect between prices and unemployment and clearly outlined its temporal structure. On one hand, the rise in most commodity prices will stimulate the expansion of industrial product production capacity, which in turn drives an increase in short-term labor demand. Along with a significant decline in the unemployment rate, this effect peaks within one month after the shock. On the other hand, when the unemployment rate rises, it will also suppress the demand for bulk commodities through the contraction of residents’ income, causing the prices of most commodities to rise. This transmission has a lag of about two months. This finding aligns with previous research on how oil price shocks affect employment and how weakening employment suppresses demand. However, by extending the traditional “oil price-employment” evidence to a broader set of commodities, we not only reinforce the dual-channel mechanism of costs and demand on the labor market but also identify an actionable time window. This provides a basis for policy interventions to stabilize employment in the short term following a shock.

Secondly, there is also heterogeneity among different industries and sub-markets. Chemical products are most sensitive to the impact of unemployment rate, which is due to their labor-intensive production characteristics. This result is consistent with the conclusion that energy and chemical products have an amplifying response to changes in demand and cost. However, in this paper, the reaction amplitude and timing were quantified within a unified mixed frequency framework. When the energy market is confronted with the impact of unemployment, due to its rigid demand and policy regulation, its prices have greater stability. When facing the shock of unemployment rate, the INE crude oil market is more stable compared to other energy markets due to the adjustment of national strategic reserves. The decline in fuel prices has a lasting effect on the reduction in unemployment rate. When the agricultural product industry is hit by the unemployment rate, the impact on prices is greater and lasts longer, reflecting the dual constraints of people’s livelihood consumption and production cycles. The metal industry is highly differentiated. Changes in the market prices of different metals have varying impacts on the unemployment rate. Nickel, tin, and silver, due to their marginalized positions in the industrial chain, have little effect on the unemployment rate from their price fluctuations. In contrast, the price fluctuations of copper, aluminum, zinc, lead, and gold have a significant inhibitory effect on the unemployment rate. Compared with research that focuses on a single industry or individual varieties, this paper provides comparable heterogeneity evidence in four major industries and twenty-four sub-markets, clarifying which varieties have a stronger employment pull and a longer duration. Thus, it offers more operational basis for employment stability and risk management by industry and variety.

Finally, the IRF fluctuations presented in the sub-market are roughly the same as those in this industry, but they are more significant and last for a shorter period of time, reflecting the immediate response characteristics of the segmented market. Existing research often relies on industry-level indices or focuses on individual products, making it difficult to systematically compare dynamic differences across sub-markets. Our findings, covering twenty-four sub-markets simultaneously within a unified mixed-frequency framework, clearly demonstrate that price shocks propagate more rapidly to employment and unemployment in sub-markets characterized by higher liquidity and shorter inventory and order cycles. This conclusion complements average effects at the industry level, revealing that policy and corporate risk management require execution units to be refined to the product level to stabilize employment more effectively during the initial stages of shocks.

In conclusion, there is a mutual influence between commodity prices and the unemployment rate in China, and both play an irreplaceable role in maintaining the stability of the country’s macroeconomy. Based on the empirical results and the current situation, this article offers the following suggestions for the subsequent decision-making of the government and enterprises: Firstly, when the prices of bulk commodities rise, market managers can increase the market supply of bulk commodities by means such as boosting the import volume of bulk commodities and appropriately utilizing the state’s strategic reserves for bulk commodities. They can also increase the market demand for bulk commodities by providing consumption subsidies for related products in the bulk commodity market and offering lenient policies to industries related to bulk commodities. This will further maintain the supply and demand in the bulk commodity market at a stable level, achieving the goal of stabilizing the prices of bulk commodities. Secondly, when the prices of bulk commodities fluctuate sharply, the government should promptly introduce corresponding labor-related regulations or policies to ensure stable employment. When formulating strategies, decision-makers also need to take into account the heterogeneous characteristics and related uncertainties among different industries and enterprises. Thirdly, when confronted with the impact of unemployment rates, the government should pay attention to the price responses of various industries while implementing labor force programs, and appropriately adjust safeguard measures based on the nature of different enterprises. Enterprises need to accelerate technological progress and innovation to enhance their own stability. Finally, given the influence of China’s bulk commodity market on the world, the state should formulate proactive foreign trade policies to promote the stable operation of the world economy.

Author Contributions

T.L. and Z.C. conceived the study and designed the conceptual framework. Z.C. and L.S. developed the methodology and implemented the analytical software. T.L., L.S. and T.Z. conducted formal analysis and performed data curation. Y.Z. (Yanfei Zhang) and T.Z. contributed to investigation, validation, and data visualization. J.X. and Y.Z. (Yumin Zhang) provided resources, supervised aspects of the project, and contributed to writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration—National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD1002005, 2024ZD1002002) and the China Geological Survey Program (DD20230308).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wellenreuther, C.; Voelzke, J. Speculation and volatility—A time-varying approach applied on Chinese commodity futures markets. J. Futures Mark. 2019, 39, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuguo, S.; Wenwen, K.; Hua, Z. The evolution of the global cobalt and lithium trade pattern and the impacts of the low-cobalt technology of lithium batteries based on multiplex network. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, H. The impact of COVID-19 on commodity options market: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2022, 116, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, M.C.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Q. COVID-19 and China commodity price jump behavior: An information spillover and wavelet coherency analysis. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattich, T.; Freeman, D.; Scholten, D.; Yan, S. Renewable energy in EU-China relations: Policy interdependence and its geopolitical implications. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Q.; Hordofa, T.T.; Kaur, P.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Maneengam, A. Does COVID-19 pandemic cause natural resources commodity prices volatility? Empirical evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Liu, T.; Tang, K.; Zeng, J. Online prices and inflation during the nationwide COVID-19 quarantine period: Evidence from 107 Chinese websites. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.-H.; Yong, K.-S. The impact of US-Sino trade war on commodity-currency nexus. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2025, 30, 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Du, T.; Li, J. The impact of China’s macroeconomic determinants on commodity prices. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 36, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.; Serletis, A. Volatility in oil prices and manufacturing activity: An investigation of real options. Macroecon. Dyn. 2011, 15, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, N.P.; Ma, X. Oil price uncertainty and US employment growth. Energy Econ. 2020, 91, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.E.; Oglend, A.; Yahya, M. Dynamics of volatility spillover in commodity markets: Linking crude oil to agriculture. J. Commod. Mark. 2020, 20, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Ren, X.; Wen, F.; Chen, J. Evolution of the information transmission between Chinese and international oil markets: A quantile-based framework. J. Commod. Mark. 2023, 29, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, F.; Zhang, D.; Ji, Q. Energy market reforms in China and the time-varying connectedness of domestic and international markets. Energy Econ. 2023, 117, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Shao, L. Dynamic spillovers between energy and stock markets and their implications in the context of COVID-19. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 77, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, F.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Geopolitical risk and oil volatility: A new insight. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaaslan, O.K. Oil price uncertainty and unemployment. Energy Econ. 2019, 81, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, L. The time-varying causal relationship between oil price and unemployment: Evidence from the US and China (EGY 118745). Energy 2020, 212, 118745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaarslan, B.; Soytas, M.A.; Soytas, U. The asymmetric impact of oil prices, interest rates and oil price uncertainty on unemployment in the US. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Mei, Y.; Wu, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X. Energy revolution and security guarantee of China’s energy economy. Strateg. Study Chin. Acad. Eng. 2021, 23, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-H.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Oana-Ramona, L. Do oil price shocks drive unemployment? Evidence from Russia and Canada. Energy 2022, 253, 124107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Fu, C.; Gong, X.; Fan, C. The oil price plummeted in 2014–2015: Is there an effect on Chinese firms’ labour investment? Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fæhn, T.; Gómez-Plana, A.G.; Kverndokk, S. Can a carbon permit system reduce Spanish unemployment? Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, V. Copper mining in Chile and its regional employment linkages. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Unemployment, consumption smoothing and precautionary saving in urban China. In Unemployment, Inequality and Poverty in Urban China; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006; pp. 106–128. [Google Scholar]

- Motegi, K.; Sadahiro, A. Sluggish private investment in Japan’s Lost Decade: Mixed frequency vector autoregression approach. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 43, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-H.; Su, C.-W.; Umar, M. Geopolitical risk and crude oil security: A Chinese perspective. Energy 2021, 219, 119555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, H. Technological unemployment in industrial countries. J. Evol. Econ. 2013, 23, 1099–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damelang, A.; Otto, M. Who is replaced by robots? Robotization and the risk of unemployment for different types of workers. Work Occup. 2024, 51, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, M.; Normandin, M. The price of imported capital and consumption fluctuations in emerging economies. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 108, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bown, C.P.; Crowley, M.A. Emerging economies, trade policy, and macroeconomic shocks. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 111, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wei, H. The impact of RMB exchange rate changes on the prices of imported products by Chinese firms. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Puello, G.; Chávez, A.; Trujillo, M.P. Youth unemployment during economic shocks: Evidence from the metal-mining prices super cycle in Chile. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhou, R. Shirking and capital accumulation under oligopolistic competition. J. Econ. Stud. 2024, 51, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, M. The welfare consequences of a quantitative search and matching approach to the labor market. Bull. Econ. Res. 2018, 70, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lyu, P.; Sun, J. Environmental regulation and equilibrium unemployment in China: Evidence from a multiple-sector search and matching model. China Econ. Rev. 2025, 89, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beladi, H.; Cheng, C.; Hu, M.; Yuan, Y. Unemployment governance, labour cost and earnings management: Evidence from China. World Econ. 2020, 43, 2526–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.; Rao, K.; Sufi, A. Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump. Q. J. Econ. 2013, 128, 1687–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noerhidajati, S.; Purwoko, A.B.; Werdaningtyas, H.; Kamil, A.I.; Dartanto, T. Household financial vulnerability in Indonesia: Measurement and determinants. Econ. Model. 2021, 96, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaillat, P.; Saez, E. Aggregate demand, idle time, and unemployment. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 507–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagereng, A.; Onshuus, H.; Torstensen, K.N. The consumption expenditure response to unemployment: Evidence from Norwegian households. J. Monet. Econ. 2024, 146, 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, G.; Urrutia, C. Informality, labor regulation, and the business cycle. J. Int. Econ. 2020, 126, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).