Abstract

This paper examines how sustainable leadership and strategic sustainability integration are framed and supported for SMEs in the EU. We apply comparative document analysis (CDA) to 35 policy, industry, and NGO reports published in 2020–2025 for Germany, Sweden, Poland, and Spain. Multi-level materials (EU, national, industry/NGO) were thematically coded, and the synthesis is presented in a multi-level conceptual framework linking policies, leadership, strategy, barriers, and transferable practices. The analysis indicates systematic differences in institutional maturity: Sweden and Germany display denser, more navigable support ecosystems and clearer leadership narratives, whereas Poland and Spain exhibit greater fragmentation and a more compliance-oriented framing. Instrument menus are broadly similar (grants/co-funding, concessional finance, advisory vouchers, training, standards/toolkits, green public procurement), yet accessibility and measurement strength diverge; outcome tracking (e.g., energy savings, CO2e avoided) is more consistent in Sweden/Germany than in Poland/Spain. Green–digital coupling is pivotal: sequencing “on-ramps” (advisory/vouchers) into innovation finance accelerates adoption; where such on-ramps are thin, uptake concentrates among already prepared firms. Implications follow for policy design and practice: prioritize simple entry points for micro- and small enterprises, strengthen monitoring with meaningful KPIs, and ensure regional parity in access to finance and advisory. For SME leaders, role-modeling, employee development, and experimentation help embed sustainability when formal structures are lean. Beyond mapping patterns, this study provides an auditable operationalization of sustainable leadership for document analysis and a transferable framework to compare policy mixes and ecosystem readiness across countries.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constitute 99% of all businesses in the European Union and employ two-thirds of the workforce, making them critical actors in the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainable development. With global challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and social inequality intensifying, the importance of integrating sustainability into SME strategies is becoming increasingly urgent. Recognizing this, the European Commission has launched dedicated frameworks, such as the SME Strategy for a Sustainable and Digital Europe, and embedded SMEs at the core of the Green Deal Industrial Plan [1,2,3,4,5].

Although large enterprises often receive attention for their sustainability performance, SMEs collectively account for a significant share of Europe’s environmental footprint and innovation potential. Their ability to adapt to and implement sustainable practices is therefore decisive in achieving EU climate and social goals. SMEs face constraints such as limited financial resources, lower levels of regulatory preparedness, and capacity gaps in leadership and strategic planning [6,7,8,9,10].

Previous studies have emphasized the role of leadership in shaping sustainability culture within organizations, particularly through transformational leadership and stakeholder orientation. Strategic management, in turn, is essential for embedding sustainability into core business models, aligning internal capabilities with external pressures. Yet, research into how these dimensions interact in the SME context remains fragmented, often lacking comparative, document-based insights across policy and institutional frameworks [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

This article addresses this gap by analyzing 35 official documents, including EU policies, national strategies (from Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden), industry reports, and NGO assessments. Through qualitative document analysis (QDA), this study seeks to identify how sustainable leadership and strategic management are framed, supported, and implemented in SMEs.

This study pursues three guiding questions:

- 1.

- How are sustainable leadership and strategic sustainability integration framed and supported for SMEs in European policy and industry documents?

- 2.

- What institutional factors and policy instruments enable or hinder SME sustainability transitions in different EU member states?

- 3.

- How do industry associations and NGOs complement public policies in shaping sustainability practices and leadership narratives in SMEs?

Comparing policy texts, this research offers a synthesized overview of the current institutional landscape and proposes a conceptual framework for enhancing sustainability-oriented leadership and strategic planning in SMEs. In doing so, this study contributes to both scholarly understanding and policymaking efforts aimed at enabling a just, green, and innovative transformation of Europe’s SME sector [18,19,20,21,22].

This study adopts a comparative document analysis (CDA) to capture what surveys and case studies often miss: the normative–institutional spine of the transition—policy language, instrument logics, and implementation mechanisms—visible simultaneously at EU, national, and industry/NGO levels. Unlike surveys, which are constrained by self-reported perceptions and heterogeneous definitions, CDA draws on programmatic and evaluative sources to reveal coherence (or its absence), prioritization, and implicit regulatory assumptions. Relative to case studies—deep yet idiosyncratic—CDA enables a systematic, cross-country synthesis of discourses and instruments, providing a basis for a generalizable conceptual framework and institutional-maturity mapping. The research gap we address is the lack of studies that combine a multi-level comparative reading of EU–country–industry/NGO documents with an explicit operationalization of sustainable leadership and strategic integration in SMEs; existing SME research remains firm-centric (surveys/cases) and rarely benchmarked against the consistency of policies and support ecosystems. Our CDA fills this gap by translating policy and sectoral texts into comparable analytical categories and actionable insights for theory and practice [23,24,25,26].

2. Literature Review

Sustainable leadership and strategic management in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have gained increasing scholarly attention as global sustainability imperatives deepen. SMEs face unique constraints compared to large corporations, yet they also possess inherent agility and innovation potential that make them strategic agents of change [10,16].

2.1. Sustainable Leadership in SMEs

The concept of sustainable leadership transcends traditional managerial concerns by embedding long-term ecological, economic, and social responsibility into the decision-making process. Avery and Bergsteiner’s “sustainable leadership pyramid” emphasizes values such as trust, ethical governance, stakeholder orientation, and systemic thinking. In the context of SMEs, leadership plays a central role in fostering a sustainability culture, especially where formal structures are limited. Transformational and values-based leadership approaches have been shown to influence pro-environmental behaviors and employee engagement in sustainability goals [11,13,14,15].

Nevertheless, empirical research suggests that SMEs often lack dedicated sustainability officers or structured CSR departments, making leadership influence more direct but also more vulnerable to capacity gaps. Studies by Jenkins and Revell emphasize the personalized nature of sustainability decisions in SMEs, where owner-managers are both the strategic and ethical compass of the organization [3,4].

2.2. Strategic Management and Business Models for Sustainability

Strategic management in SMEs has traditionally focused on survival, growth, and competitive positioning. Recent literature reflects a growing integration of sustainability into strategic processes through business model innovation (BMI) and strategic flexibility. Bocken et al. argue for the centrality of value creation and delivery for multiple stakeholders—including society and the environment—in sustainable business models [19].

In the SME context, strategic decisions are strongly shaped by external pressures such as regulation, market demand, and resource availability, but also by internal leadership vision. Studies show that SMEs that adopt sustainability strategically—rather than reactively—achieve better resilience and long-term positioning. Despite this, the literature notes significant implementation barriers, including short planning horizons, financial uncertainty, and lack of metrics for tracking sustainability performance [6,10,26].

2.3. Policy and Institutional Support

The role of institutions in enabling sustainable SME strategies is widely recognized. Policy instruments such as grants, tax incentives, capacity-building, and advisory services have been found to be effective in supporting transitions, particularly when they are stable, predictable, and targeted at SME realities. However, scholars note that policy fragmentation, administrative burdens, and lack of harmonized ESG standards often deter SME engagement [20,21,22].

In the European context, the SME Strategy (2020) and the Green Deal Industrial Plan (2023) offer a macro-level policy push for sustainability integration, but implementation remains uneven across member states. Comparative studies (e.g., Germany vs. Poland) reveal how institutional maturity, regional ecosystems, and digital infrastructure condition the effectiveness of policy instruments [1,2,6,9].

2.4. Recent Evidence (2019–2025)

To address calls for stronger theoretical grounding, we integrated recent peer-reviewed work (2019–2025) on sustainable leadership in SMEs, dynamic capabilities, green–digital coupling, and policy instrument effectiveness. These sources inform our coding scheme and the interpretation of cross-country patterns. Recent SME studies operationalize sustainable leadership as leadership that embeds long-term stakeholder value and triple-bottom-line priorities into strategy and day-to-day behaviors; evidence from Central/Eastern Europe shows this can be expressed through the “honeybee” logic of mutually reinforcing practices (people development, trust, innovation) in small firms Conceptual advances further connect leadership to sustainability-oriented innovation and stakeholder integration, proposing capability-based taxonomies that clarify how leadership intent is translated into organizational routines in SMEs [15,16,24].

A complementary stream emphasizes dynamic capabilities—the abilities to sense, seize, and reconfigure—as a mechanism linking leadership and superior sustainability performance in small firms. Empirical work shows that SMEs with stronger (especially external integrative) dynamic capabilities achieve better economic, environmental, and social outcomes, because they mobilize knowledge and resources from customers, suppliers, and partners to overcome constraints typical of smaller organizations. Recent typologies consolidate this view, arguing that leadership commitment generates results when firms build capabilities for co-innovation, stakeholder engagement, and continuous learning—thereby operationalizing sustainability strategies under resource scarcity [16,24,25].

Leadership agility is increasingly recognised as a prerequisite for navigating volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environments. Syamsir et al. (2025) [26], in their systematic review, emphasise that agile leaders demonstrate not only flexibility in decision-making but also the ability to balance short-term adaptation with long-term strategic orientation [26]. This resonates with our findings on SMEs in Sweden and Germany, where leadership discourse explicitly highlights adaptability and foresight. In contrast, in Poland and Spain, such agility is less visible, reflecting the more reactive stance of institutional frameworks [26].

The literature also underscores the twin transition: deliberate coupling of digitalization and sustainability to accelerate SME outcomes. EU-focused studies show that digital tools (analytics, IoT, data platforms) can enable greener operations and circular models, while sustainability goals guide responsible tech adoption and long-term competitiveness [8,26].

Digital transformation is not only a technological shift but a strategic lever for organisational resilience. Sagala and Őri (2025) demonstrate, through a systematic literature review, that SMEs engaging in digitalisation can achieve both resilience and antifragility—the ability to grow stronger when exposed to shocks [27,28]. Their insights provide a useful lens to interpret the EU’s emphasis on digital “on-ramps” as enabling SMEs to turn crises, such as COVID-19 or energy shocks, into opportunities for growth. Our comparative results confirm that this dimension is most advanced in Sweden and Germany, whereas in Poland digitalisation remains framed as a challenge rather than a driver of sustainable competitiveness [27,28].

At the policy level, evidence points to the effectiveness of targeted instrument mixes—innovation grants, advisory vouchers, and concessional finance—when combined with measurement using meaningful KPIs (e.g., energy savings, CO2e avoided). New SME-tailored carbon-accounting tools further lower the cost of monitoring and help firms identify abatement hotspots, improving the link between incentives and verifiable outcomes. Taken together, these insights support our operationalization and help explain cross-country differences in institutional maturity and adoption trajectories observed in our corpus [20,29].

While the existing literature provides valuable insights into leadership and strategic sustainability in SMEs, few studies comprehensively examine how public documents—such as policies, reports, and frameworks—shape and reflect these practices. Most prior work focuses on firm-level case studies or survey data. A document-based analysis across countries and actors (EU, national governments, industry associations, NGOs) can offer a broader and more systemic understanding of the institutional environment of SME sustainability. This study seeks to fill this gap by integrating document analysis with comparative institutional insights.

2.5. Defining Sustainable Leadership in the SME Context

Sustainable leadership refers to a leadership approach that integrates long-term organizational performance with broader sustainability goals, balancing economic success with social and environmental responsibility and creating enduring value for stakeholders [11,12,13].

The micro-foundations of sustainability in SMEs depend not only on institutional incentives but also on leadership practices. Piwowar-Sulej and Iqbal (2025), drawing on Conservation of Resources Theory, show that leaders who explicitly prioritise sustainability trigger pro-environmental behaviours among employees, thereby embedding sustainability into everyday practices [30]. This supports our interpretation of the Swedish and German cases, where policy discourse links leadership with employee engagement. Conversely, in Poland and Spain the absence of such framing may explain why pro-environmental behaviours are less institutionalized [30].

It is, in essence, the product of integrating sustainability and leadership—meeting stakeholder needs and developing the core business in ways that create long-term value for people, planet, and profit. This concept goes beyond related ideas like green or responsible leadership by explicitly emphasizing triple-bottom-line outcomes and stakeholder inclusion [11]. Classic frameworks reinforce this holistic view. Avery and Bergsteiner conceptualize sustainable leadership as a coherent system of mutually reinforcing practices (the “honeybee” logic) that nurture people, foster trust and innovation, and privilege long-term viability, in explicit contrast to short-sighted, exploitative “locust” approaches. These practices collectively cultivate resilient, high-performing organizations oriented toward lasting, shared stakeholder value [12,15]. Recent reviews converge on this point: while authors differ in emphasis (e.g., enduring stakeholder value, integrative influence, systems thinking), they share a long-term, stakeholder-centric core [11]. Earlier work by Hargreaves and Fink similarly underscored that truly sustainable leadership creates and preserves sustained learning, secures success over time, sustains the leadership of others, develops rather than depletes human and material resources, and actively engages with the environment [13].

Beyond traditional leadership models, humility has emerged as a powerful driver of innovation in SMEs. He et al. (2025) provide empirical evidence that humble leadership fosters employee creativity and contributes to achieving SDG 8 (decent work) and SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure) in the Industry 4.0 context [31]. Their findings extend current discussions by showing that sustainable leadership is not only about vision but also about openness, inclusivity, and empowering employees. This complements our observation that leadership in Sweden is explicitly connected to participatory governance, while in Poland, it is more implicitly embedded in managerial discourse [31].

In this paper, we therefore define sustainable leadership as leadership that simultaneously drives long-term organizational success and upholds the well-being of people and the planet through values, practices, and behaviors that ensure the enterprise’s longevity and responsibility. This definition will guide our analysis in the SME context.

Leadership vs. Management—Key Distinctions. A clear conceptual delineation between leadership and management is necessary before examining sustainable leadership in depth. While the two overlap, scholarship distinguishes them along several dimensions. Conceptually, leadership is associated with setting direction and orchestrating change, whereas management concerns coping with complexity and maintaining order in established processes. Functionally, managers plan, budget, organize, and control; leaders establish a vision, align people, and motivate and inspire them to overcome obstacles. Behaviorally, managerial work relies more on formal authority and systems, while leadership mobilizes through influence, shared purpose, and values. Effective organizations require both strong management and strong leadership, yet these capacities are analytically distinct—especially when assessing sustainability-related change [14].

Implications for SMEs. In small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), flat structures and scarce resources mean owner-managers often wear both “leader” and “manager” hats. With few layers of upper management, leadership influence pervades all levels of the firm, and formal systems (for strategy, HR, or sustainability) are minimal. In practice, the SME leader typically must go beyond administrative duties to provide vision, role-model values, and build culture. Evidence on SMEs indicates that leadership and management capabilities are tightly linked to performance and the adoption of improved practices; conversely, capability gaps constrain growth and change. For SMEs, sustainable leadership therefore means embedding sustainability in strategy and day-to-day behaviors—aligning employee development, stakeholder relationships, innovation, and environmental stewardship with long-term competitiveness—largely via leadership influence rather than bureaucracy. The stakes are also contextually salient: decisions by SME leaders often have immediate implications for employees and local communities, making long-term thinking and stakeholder well-being central to viable strategy. In short, the SME environment amplifies the need for leadership (vision, inspiration, ethical guidance) alongside management (organization and control), with the leader pivotal to driving sustainable strategic integration under conditions of constrained resources and informal structure [15,17].

Importance of Conceptual Clarity for This Study. Defining sustainable leadership clearly—and distinguishing it from management—is crucial for our comparative document analysis (CDA). We examine how sustainable-leadership principles and strategic sustainability integration manifest in SMEs across multiple EU countries by analyzing multi-level texts (EU, national, industry/NGO). A precise, SME-tailored definition ensures we consistently identify leadership behaviors and practices in policy documents, corporate reports, and sectoral materials, and it prevents conflating generic management routines with leadership indicators. This shared definition also strengthens cross-country comparability—important where terms like “leadership” or “sustainability” carry different connotations across languages and institutional contexts. Grounding our coding in a long-term, stakeholder-oriented notion of sustainable leadership enhances the coherence and validity of the CDA, allowing us to draw meaningful insights about leadership and strategic sustainability integration across cases [11,14].

Why This Matters for the Present Study. Articulating what sustainable leadership means—and how it differs from traditional management—sets the stage for identifying the leadership-driven practices we expect to observe (or not) in the SMEs under investigation. Without a solid definition, managerial actions could be misread as leadership, or leadership-driven changes in strategy could be overlooked. Conceptual clarity sharpens the focus of our analysis, improves attribution of outcomes to leadership, and enables apples-to-apples comparisons across EU countries. In a field where inconsistent terminology is frequently noted, definitional rigor responds to calls for stronger theoretical consistency and provides the conceptual baseline for our subsequent analysis of evidence and outcomes [11,14].

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative document analysis (QDA) approach, in line with desk research traditions used in policy and institutional studies [18]. Document analysis was chosen for its capacity to uncover latent structures, discursive framings, and inter-institutional alignments that shape sustainable leadership and strategic management in SMEs [13,18]. Unlike firm-level surveys or interviews, QDA allows researchers to systematically investigate the normative frameworks and support ecosystems communicated through public and semi-public documents [18,23].

Country Selection (Germany, Sweden, Poland, Spain)

We purposefully selected Germany, Sweden, Poland, and Spain to span contrasting institutional configurations within the EU while holding constant the single-market policy frame. Germany represents a coordinated market economy with strong social partnership and codetermination; Sweden exemplifies the Nordic model with high policy capacity and dense innovation–sustainability support; Poland reflects a post-transition, catching-up economy with evolving SME policy instruments; and Spain illustrates a Southern EU context with a different sectoral mix and multi-level governance arrangements. This designed heterogeneity allows us to examine how sustainable-leadership ideas and instruments travel across varied institutional settings (industrial relations, administrative capacity, financing channels) under a common EU regulatory umbrella. Importantly, in all four countries SMEs overwhelmingly dominate the business demography (>99% of enterprises), so cross-country differences in our analysis are driven by institutions and policy mixes, not by SME prevalence itself (see Table 1).

Table 1.

SMEs as a share of all enterprises (latest available; non-financial business economy).

The corpus includes 35 selected documents grouped into four categories:

- (1)

- European Union reports (12 documents): Including the SME Strategy for a Sustainable and Digital Europe [1], the Green Deal Industrial Plan [2], Eurostat performance reports [36], and evaluations by EASME [37].

- (2)

- National-level documents (8 documents): Sourced from agencies in Germany (BAFA, INQA) [38,39], Poland (PARP, InFiN) [9,40], and Spain (ADEME) [41], these documents focus on sustainability programs, innovation strategies, and recovery plans.

- (3)

- Industry reports (10 documents): Produced by organizations such as SMEunited [42], CSR Europe [43], Vinnova [44], and the GreenTech Alliance [45], presenting sectoral perspectives on sustainability and leadership.

- (4)

- Think tank and NGO publications (5 documents): Reports from OECD [20], WBCSD [21], Bruegel [5], and BSR [46] offer comparative insight into enabling environments and global frameworks.

All documents were selected based on their (1) policy relevance, (2) sectoral focus on SMEs, (3) explicit framing of sustainability or leadership, and (4) date of publication (2020–2024) to ensure contemporaneity.

Documents were thematically coded using MAXQDA 24.11 software, applying the principles of applied qualitative content analysis as outlined by Mayring and Schreier [18,47]. The coding process began with an inductive exploration of a pilot sample of five documents, which allowed for the identification of core emerging themes based on the language, structure, and strategic framing of sustainability within the SME context. These preliminary insights informed the development of a structured, deductive codebook that was subsequently applied to the full corpus of 35 documents [18,47].

Building on the definition provided in Section 2.1, a hybrid (deductive–inductive) codebook was developed and applied to the multi-level corpus. Table 2 presents the thematic dimensions, code labels, and illustrative quotations used to operationalize sustainable leadership, thereby linking conceptual criteria to concrete textual indicators and supporting cross-country comparability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operationalization of “sustainable leadership” through document coding.

Developing the codebook for this study was a combined inductive and deductive process. An initial set of themes was derived from sustainability leadership theory and refined through pilot coding of a subset of documents. This inductive exploration (coding five sample texts) allowed emerging patterns to be captured and informed adjustments to the code definitions. The resulting structured codebook centered on key dimensions of sustainable leadership (e.g., long-term orientation, stakeholder inclusion, trust-building; see Table 2 for examples). To ensure reliability, two researchers independently double-coded a selection of documents (approximately 20% of the corpus) using the draft codebook. Coding discrepancies were reviewed and resolved through discussion, leading to clarifications in code definitions and a high level of intercoder agreement.

The documents analyzed were selected purposively based on clear criteria: relevance to SME sustainability and leadership, credible source type, language, and publication period. In total, 35 policy and industry reports (in English or translated) from 2020–2025 were included, encompassing European Union strategy papers, national SME sustainability initiatives (e.g., from Germany, Poland, Spain), industry association reports, and NGO/think-tank publications. All documents explicitly addressed aspects of SME strategy or leadership in the context of sustainable development. Coding and analysis were facilitated by MAXQDA software, which enabled systematic organization of codes and efficient retrieval of coded segments and quotations. Adopting this transparent coding scheme within a critical discourse analysis (CDA) approach strengthens this study’s validity: it creates an audit trail from text to themes, helps mitigate researcher bias, and demonstrates how interpretations of “sustainable leadership” in discourse are grounded in consistent, reproducible coding decisions [18,47].

The corpus consists of 35 official reports and policy documents published between 2020 and 2025, selected using a purposive sampling approach based on relevance, authorship credibility, and policy impact. The documents were categorized into four types (Table 3).

Table 3.

Corpus of Documents.

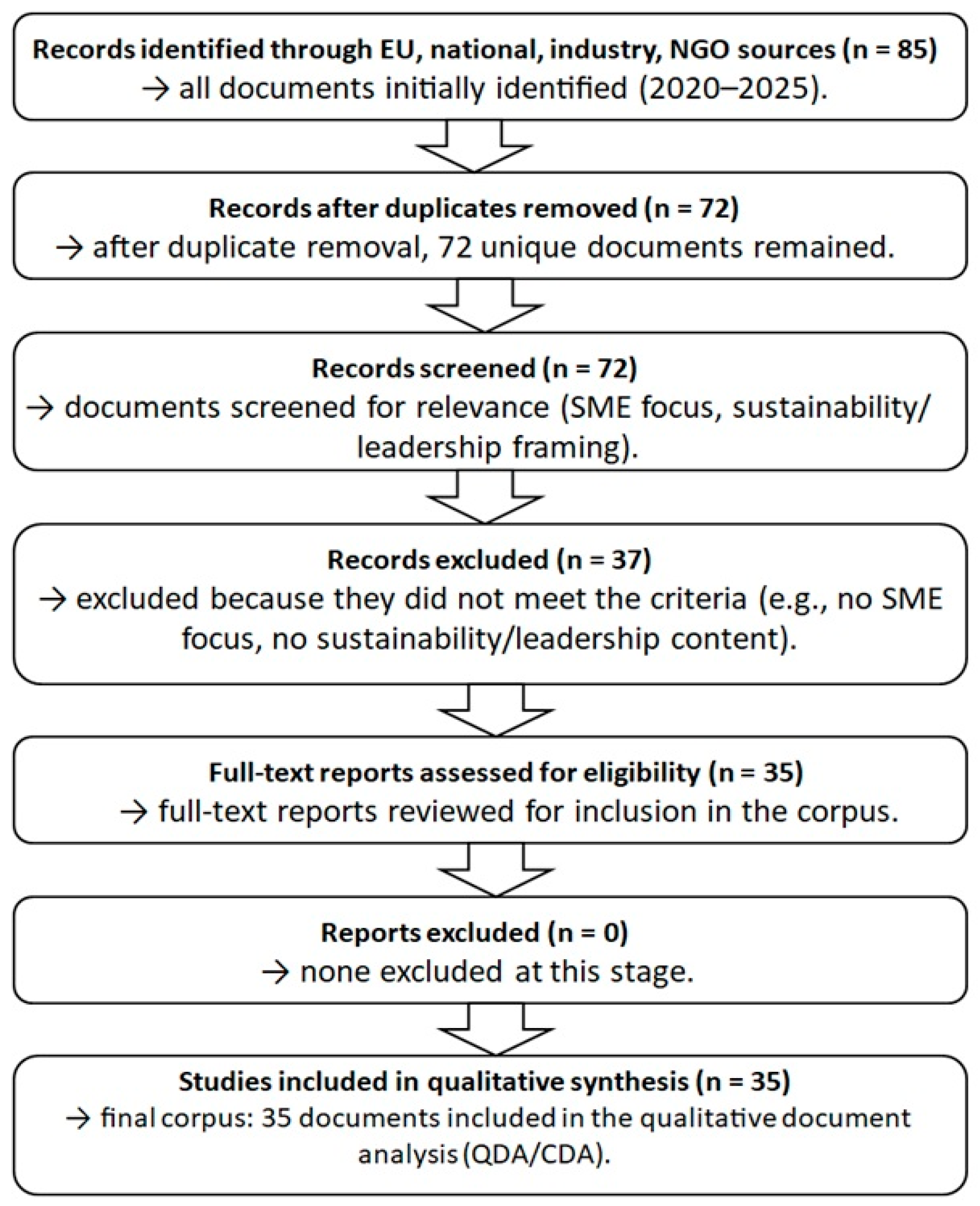

The document selection process is summarized in a PRISMA-style flow diagram (Figure 1). Out of 85 documents initially identified, 72 remained after removing duplicates. After screening for relevance (SME focus, sustainability/leadership framing, 2020–2025), 37 documents were excluded. The final corpus comprised 35 documents, all of which were included in the qualitative document analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for document selection (2020–2025), showing identification, screening, exclusions, and the final corpus (n = 35).

The coding framework focused on five overarching thematic domains: (1) sustainable leadership styles and discourses, including transformational, ethical, and participatory leadership narratives; (2) strategic integration of sustainability, such as ESG planning mechanisms and the redesign of SME business models to align with sustainability goals; (3) policy instruments and institutional support structures, including financial incentives, regulatory tools, and advisory schemes; (4) structural barriers and enabling conditions that affect the implementation of sustainability initiatives in SMEs; and (5) patterns of cross-national policy divergence and the identification of transferable best practices across member states [6,11,19,20,23].

To enhance the reliability of results, the coding process included intercoder validation, with selected documents analyzed independently by two coders and discrepancies resolved through iterative discussion. The use of MAXQDA’s visual tools, including frequency distributions, code co-occurrence matrices, and document group comparisons, supported the analytic synthesis and enabled the identification of institutional patterns and strategic logics relevant to SME sustainability across the European policy landscape [18,47].

4. Results

4.1. Cross-Country Comparison: Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden

The comparative analysis of policy documents and sectoral reports from Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden reveals both converging and diverging approaches to promoting sustainable leadership and strategic management in SMEs. While all four countries formally align with the overarching principles of the European Green Deal and the EU SME Strategy, national implementation varies significantly in terms of scope, structure, and emphasis [9,33,38,41,48].

Germany demonstrates a strongly institutionalized approach, characterized by structured funding mechanisms and regulatory enforcement. Documents issued by BAFA, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), and regional innovation agencies emphasize compliance with the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (Lieferkettengesetz), combined with tailored SME support programs such as the “Mittelstand-Digital” initiative and the BAFA Energy Audit program. These frameworks actively promote energy efficiency, digital transformation, and sustainable innovation among SMEs. Moreover, Germany’s regional cluster systems—especially in the manufacturing and engineering sectors—serve as platforms for cross-firm collaboration and capacity building. The leadership discourse in German documents frequently references responsibility, transparency, and long-term competitiveness as key elements of sustainability [38,39,48].

In Poland, the dominant narrative is still shaped by post-crisis economic recovery and EU structural funding priorities. Reports from the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) and national innovation strategies place growing emphasis on sustainability, yet tend to frame it as a compliance issue rather than an entrepreneurial opportunity. Programs under the European Funds for Smart Economy (FENG) include green investment components, but access to support is often hindered by bureaucratic complexity and weak advisory structures. Leadership discourse in Polish policy texts is less developed and generally focuses on financial incentives rather than cultural or strategic transformation. Nonetheless, recent PARP reports indicate a positive trend in SME engagement with environmental certification schemes and digital tools for energy monitoring [9,40,66].

Spain presents a mixed picture, balancing strong regional diversity with a growing national focus on green entrepreneurship. Policy documents from the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Ministry of Industry emphasize low-carbon innovation and decarbonisation pathways for SMEs, particularly in the transport, construction, and tourism sectors. Spain’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan (PRTR) includes a dedicated pillar on the green transition of SMEs, funded through the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility. Regional development agencies in Catalonia, Andalusia, and the Basque Country have also launched targeted programs encouraging sustainability audits, eco-labeling, and cross-sectoral collaboration. Leadership in Spanish SMEs is often associated with social value, community orientation, and innovation through necessity—especially in rural and island economies [55,56,57,67].

Sweden, by contrast, exemplifies a high-maturity sustainability ecosystem in which SMEs operate within a well-integrated network of public agencies, academic institutions, and private-sector actors. Reports from agencies such as Vinnova and Tillväxtverket highlight national initiatives like the “Sustainable Business” and “Climate Leap” programs, which offer co-financing and coaching for climate-smart solutions in SMEs. Swedish policy emphasizes co-creation, ethical governance, and gender-inclusive innovation as pillars of sustainable leadership. SMEs are also more likely to engage in voluntary ESG reporting and circular economy practices, as these are culturally embedded within Swedish business norms. Leadership styles tend to be participatory and team-based, reflecting the broader societal orientation toward flat hierarchies and consensus building [33,44,68,69].

Across all four countries, common barriers to sustainability adoption include limited internal capacity, regulatory uncertainty, and financing constraints. Nevertheless, the extent to which these are addressed through national policies and support systems differs markedly. Germany and Sweden offer more comprehensive, integrated, and proactive approaches, while Poland and Spain display evolving, but still fragmented, institutional responses. The level of strategic leadership discourse also varies: it is highly articulated in German and Swedish contexts, moderately present in Spain, and relatively underdeveloped in Polish documents [6,9,33,38,44,48,56,67,69].

To improve readability of the cross-country comparison, Table 4 summarizes the main barriers and enablers identified across Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden.

Table 4.

Barriers vs. Enablers for SME Sustainability (synthetic comparison).

As shown in Table 4, barriers are remarkably similar across countries, but the density and accessibility of enablers differ, shaping the speed of adoption.

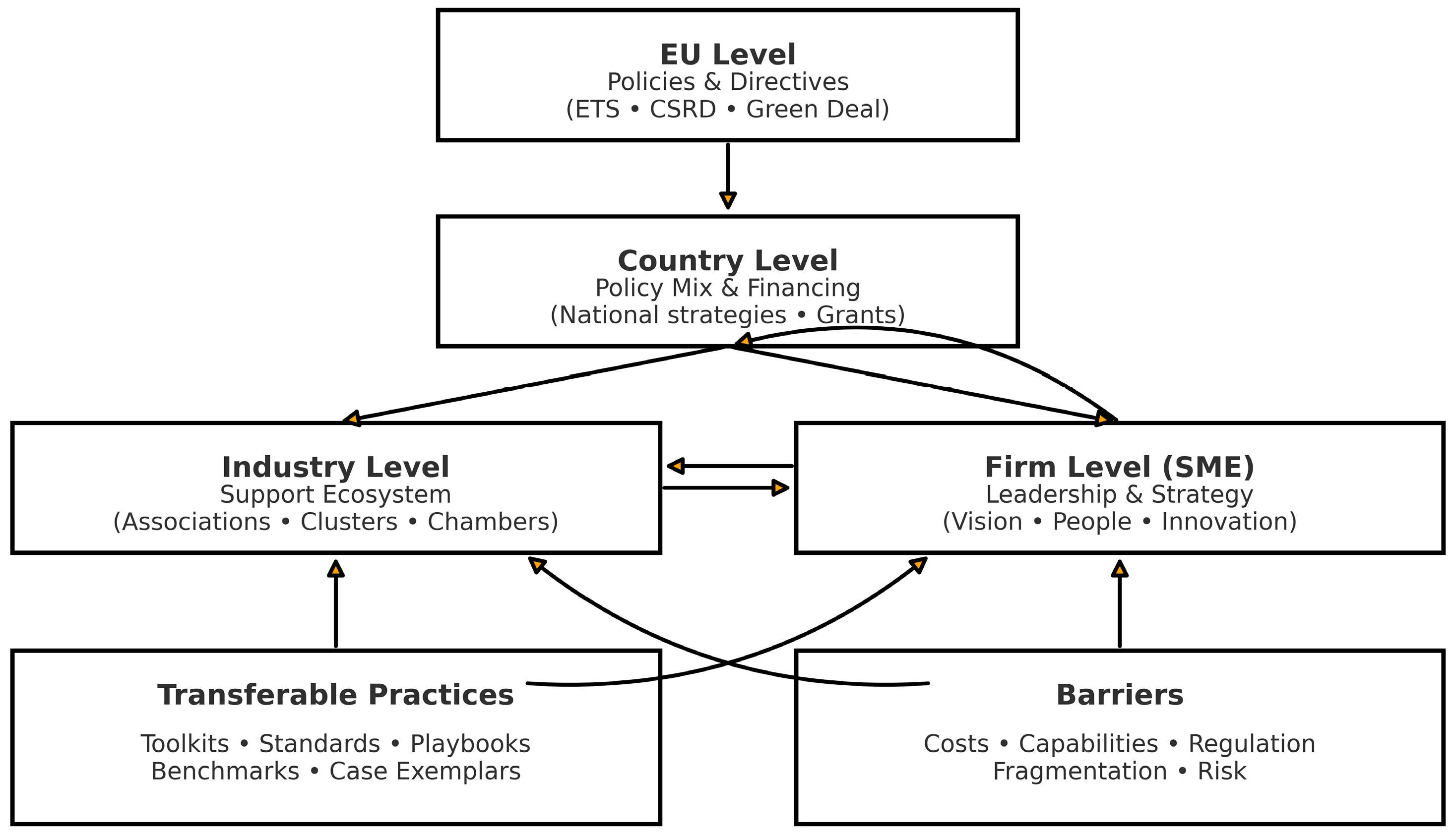

To synthesize these patterns, Figure 2 integrates the five analytical dimensions across the multi-level system—EU policies, national policy mixes, industry support ecosystems, SME-level leadership and strategy—together with barriers and transferable practices.

Figure 2.

Multi-level framework for SME sustainability leadership and policy integration. Source: Own study.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework linking five dimensions—Policies, Leadership, Strategy, Barriers, and Transferable Practices—across multi-level governance (EU → Country → Industry → Firm/SME). EU-level directives and standards shape national policy mixes and financing; these enable industry support ecosystems, which in turn inform SME-level leadership and strategy. Barriers (e.g., costs, capability gaps, regulatory complexity) constrain diffusion at multiple stages, while transferable practices (toolkits, standards, playbooks, exemplars) flow laterally and feedback upward as policy learning.

These cross-country divergences are consistent with evidence that SMEs with stronger dynamic capabilities—particularly the ability to integrate external knowledge and resources—achieve superior sustainability performance under varying policy contexts [16]. Dynamic capabilities enable firms to sense, seize, and reconfigure resources in ways that transform leadership intent into operational practices, thus mitigating structural barriers and institutional fragmentation. This helps explain why similar policy instrument menus yield different outcomes across countries: SMEs embedded in ecosystems that foster collaboration, learning, and stakeholder integration are better positioned to leverage public support effectively. Recent studies emphasize capability-building as the bridge between leadership commitment and strategic integration in SMEs, showing that only when leaders actively develop co-innovation, stakeholder engagement, and continuous learning routines does sustainability become embedded in long-term competitiveness [24].

To capture these cross-country differences systematically, Table 5 presents a comparative assessment of institutional maturity across the five dimensions for Germany, Sweden, Poland, and Spain.

Table 5.

Institutional maturity across five dimensions for Germany (DE), Sweden (SE), Poland (PL), and Spain (ES). Scores (1–4) are derived from coded evidence; anchors are provided in Appendix A.

In Germany, sustainable leadership is conceptualized primarily through the lens of responsibility, regulatory compliance, and strategic foresight. Official BAFA and BMWK documents frequently refer to the importance of “future-oriented governance,” “risk-based due diligence,” and “leadership accountability” in the implementation of sustainable practices. The role of SME owners and managing directors is emphasized, especially in facilitating certification processes, environmental audits, and digitalization for sustainability. Leadership is expected to embody transparency and legal awareness, often supported through structured mentoring and advisory programs (e.g., Mittelstand-Digital Zentrum) [38,39,48].

In Poland, leadership is presented more implicitly and tends to focus on financial decision-making and grant utilization rather than cultural transformation. PARP reports and national strategies rarely refer to leadership as a behavioral or ethical construct; rather, they emphasize management competencies in navigating EU funding mechanisms. On the other hand, some progress is noted in industry-specific programs encouraging eco-certifications and CSR declarations. Leadership in Polish SMEs is still emerging as a strategic lever for sustainability, rather than a deeply embedded organizational value [9,40,66].

Spain exhibits a more socially embedded understanding of leadership, with strong emphasis on community-oriented values and innovation under resource constraints. Documents from regional development agencies often refer to “resilient leadership” and “territorial cohesion,” highlighting the role of SME leaders in local economic regeneration and environmental stewardship. Leadership is frequently discussed in connection with rural and women-led enterprises, positioning sustainability as both a market opportunity and a social imperative [33,44,68,69].

In Sweden, sustainable leadership is described in comprehensive and normative terms. Policy frameworks supported by Tillväxtverket and Vinnova promote participatory leadership, stakeholder co-creation, and ethical governance. Leadership is explicitly linked to long-term value creation, equity, and ecological consciousness. Moreover, there is an institutional emphasis on training leaders not only in technical solutions, but also in reflective and systemic thinking. Swedish SMEs appear more inclined to internalize sustainability as a cultural norm rather than an external obligation [33,44,68,69].

The analysis of the collected documents indicates that the cultural depth of sustainable leadership is strongly correlated with the level of institutional maturity in a given country and the extent of policy support. Documents related to Germany and Sweden reveal coherent, structured, and strategic leadership narratives. In contrast, Spain’s approach is characterized by a socially embedded model, emphasizing participatory mechanisms and community-based initiatives. The documents concerning Poland, by contrast, reflect a more functional and reactive leadership discourse—largely shaped by external drivers (such as EU funding or regulatory compliance) rather than by internally anchored strategies or cultural values [9,33,38,39,40,44,48,55,56,57,66,67,68,69].

The assessment of sustainability culture maturity was guided by a scoring rubric with four levels: low, moderate, high, and very high. Each level was defined by observable indicators derived from policy, industry, and NGO documents. Two coders independently assigned scores, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. The rubric is presented in Table 6a.

Table 6.

(a) Rubric for Measuring Sustainability Culture Maturity. (b) Comparative Overview of Leadership Models and Sustainability Culture in Selected EU Countries.

These patterns are synthesized in Table 6b, which presents a comparative overview of leadership models and sustainability culture in selected EU countries. The table is based on a qualitative content analysis of the documents, focusing on dominant political discourse, institutional frameworks, and the strategic language employed in the context of ecological and digital transition.

Table 6b illustrates the diversity of leadership models and levels of sustainability culture maturity across selected EU countries. The comparison highlights how different national contexts shape strategic approaches to sustainable leadership in SMEs. Germany and Sweden exemplify mature and institutionally embedded models, with strong policy alignment and systemic thinking. Spain offers a socially rooted approach, emphasizing local resilience and inclusive entrepreneurship. In contrast, Poland’s model remains primarily instrumental, focused on external funding mechanisms, with less emphasis on cultural or systemic integration. The table underscores the importance of institutional coherence and cultural orientation in shaping effective sustainability leadership.

4.2. Strategic Integration of Sustainability in SME Business Models

Across the analyzed policy and industry documents, there is broad consensus that the integration of sustainability into SME business models is not only desirable but increasingly necessary in light of climate goals, stakeholder expectations, and evolving regulatory frameworks. However, the degree to which SMEs are strategically embedding sustainability into their operations, value propositions, and revenue logic varies considerably across national contexts.

In Germany, strategic sustainability integration is often supported through structured programs that incentivize business model innovation (BMI). Documents from BAFA and BMWK describe financial support and coaching services aimed at transforming core operations in SMEs toward digital efficiency and climate neutrality. Examples include green product redesign, integration of life cycle assessment tools, and adoption of circular economy practices. The “Mittelstand-Digital” initiative, for example, offers sector-specific guidance on embedding environmental performance indicators into operational processes. Sustainability in this context is framed as a pathway to long-term competitiveness, not merely compliance [38,39,48].

Poland, in contrast, shows more limited progress in strategic integration, although recent reports from PARP indicate an upward trend. Many Polish SMEs still perceive sustainability as an external requirement rather than a value-creating opportunity. Business model transformation is often reactive and grant-dependent. Nevertheless, selected programs under FENG (European Funds for a Smart Economy) include modules on green innovation and digital sustainability, such as energy monitoring systems and green supply chain management. Case studies highlight a small but growing number of SMEs integrating sustainability as part of their market differentiation strategies (e.g., eco-packaging, ESG reporting) [9,40,66].

In Spain, the strategic dimension of sustainability is gaining visibility, especially within regional development strategies and sector-specific plans (e.g., tourism, agriculture, energy). Reports from the Ministry for Ecological Transition emphasize the need for systemic change in business models through innovation, digital tools, and community-based entrepreneurship. Regional agencies promote programs such as “Catalonia Circular” or “Andalusia Emprende Verde”, which support SMEs in redesigning products, adopting eco-design principles, and engaging in local green value chains. However, the scaling of such models remains uneven, and often depends on region-specific political priorities and funding availability [55,56,57,67].

Sweden exhibits the most advanced integration of sustainability into SME strategies, as documented in reports from Tillväxtverket and Vinnova. Sustainability is widely internalized as a business imperative, and support systems explicitly guide SMEs in transforming their core models—not only their peripheral practices. Initiatives like “Klimatklivet” and “Circular Business Lab” provide coaching, access to innovation clusters, and funding to reconfigure products, services, and partnerships around circularity and carbon neutrality. Swedish SMEs are also early adopters of ESG metrics and often participate in co-innovation projects with universities and municipalities [33,44,68,69].

Despite differing levels of maturity, a common trend across all countries is the increasing coupling of digital and green transformation. Sustainability is no longer treated as a stand-alone objective but as a cross-cutting dimension of competitiveness, particularly when integrated with Industry 4.0 technologies, data analytics, and platform-based business models. Barriers identified in the documents include resource constraints, lack of internal expertise, and regulatory complexity—especially for micro-enterprises. Facilitators include access to regional innovation hubs, long-term funding programs, and ecosystem-based partnerships [8,25,27].

This analysis underscores that strategic integration of sustainability requires not only policy incentives, but also a cultural shift in how SMEs perceive value creation, innovation, and leadership responsibility. Countries with coherent multi-level strategies and institutional coordination—such as Germany and Sweden—demonstrate more systemic progress, while Poland and Spain are still navigating fragmented landscapes of support and regulation.

4.3. Role of Public Policies and Financial Instruments

Public policies and financial instruments play a critical role in shaping the conditions under which SMEs can engage in sustainable transformation. The analysis of documents from European institutions, national development agencies, and industry associations reveals that while all studied countries have introduced policy frameworks to promote sustainability in SMEs, their effectiveness and coherence differ markedly [1,2,20,21,22].

At the European level, the EU SME Strategy for a Sustainable and Digital Europe (European Commission, 2020) and the Green Deal Industrial Plan (2023) form the overarching policy architecture. These documents emphasize simplification of access to finance, better alignment of funding instruments with sustainability goals, and SME-specific support mechanisms such as the Single Market Programme, InvestEU, and Horizon Europe. Despite these ambitious frameworks, implementation gaps persist, especially in translating EU-level instruments into tailored, accessible solutions for smaller firms [1,2,20,22].

To organize the instrument landscape across levels and countries, Table 7 summarizes the main policy instruments—what they are, who implements them, for whom they are intended, and how outcomes are measured.

Table 7.

Policy instruments relevant to SME sustainable transformation (what/who/for whom/how measured).

Table 7 shows broad convergence in instrument menus, yet accessibility, measurement strength, and sequencing differ; where on-ramps (advisory/vouchers) are strong and KPIs are used, uptake is broader and outcomes are more trackable.

First, coverage and ease-of-access vary: Sweden and Germany offer denser, more navigable portfolios, while Spain and Poland exhibit greater regional variation and administrative frictions. Second, the strength of measurement differs: outcome tracking linked to energy savings or CO2e avoided is more systematic in Sweden/Germany than in Poland/Spain, where monitoring is improving but remains heterogeneous. Third, targeting and sequencing vary: where vouchers and advisory services act as on-ramps, they reduce information and capability gaps and crowd in subsequent investment finance; where such on-ramps are thin, uptake skews toward better-prepared firms. Taken together, these differences help explain cross-country variation in SME adoption despite otherwise similar instrument menus. The next subsections examine how these portfolios operate in each national context [38,39,48].

In Germany, public support is highly structured and multi-layered. The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), along with BAFA, offers a wide range of instruments, including subsidies for energy audits, co-financing for digitalisation, and green innovation vouchers. Programs such as “go-inno”, “Mittelstand Innovativ & Digital”, and “Energieeffizienz KMU” are frequently cited in national policy documents as successful examples of integrated financial and advisory mechanisms. These are often delivered in partnership with regional innovation centers and chambers of commerce, facilitating both accessibility and uptake. Germany stands out for aligning financial tools with clearly defined sustainability criteria and performance indicators [9,40,66,67].

Poland, while aligning formally with EU sustainability frameworks, shows a more fragmented approach to public support. Reports from PARP and national recovery plans indicate that SMEs often struggle with navigating complex application procedures, inconsistent eligibility criteria, and administrative burden. Although financial tools such as Green Loans, EcoInnovation Vouchers, and subsidies for energy modernization are available, their use is limited by low awareness, insufficient technical support, and a reactive rather than strategic funding culture. Recent improvements under FENG and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (KPO) have begun to address these shortcomings, particularly in the areas of green technology adoption and energy transition [55,56,57,67].

In Spain, public instruments reflect the country’s regionalized governance model. National plans such as the PRTR (Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan) provide substantial resources to green and digital SMEs, but delivery is largely coordinated by autonomous regions. As a result, program implementation and accessibility vary considerably. Some regions—such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Andalusia—have developed sophisticated ecosystems for supporting green entrepreneurship, including green accelerators, local tax incentives, and sectoral funds. By contrast, regions with less administrative capacity face difficulties in program rollout and SME outreach. Spanish policy documents emphasize the importance of reducing territorial asymmetries and embedding sustainability in mainstream SME policy [33,44,68,69].

Sweden offers one of the most coherent and ecosystem-based models of public support for SME sustainability. Agencies such as Tillväxtverket, Vinnova, and the Swedish Energy Agency provide not only financial instruments, but also long-term strategic guidance, coaching, and access to innovation clusters. Programs like “Klimatklivet”, “Green Transition Leap”, and “Sustainable Business Development” target both technological innovation and organizational change. Swedish policy frameworks emphasize co-creation and participatory governance, allowing SMEs to actively shape funding priorities. Moreover, sustainability criteria are integrated into procurement, tax incentives, and business development services, fostering systemic alignment [33,44,68,69].

Across all four countries, key success factors identified in the documents include: clarity of eligibility criteria, integration of funding with advisory services, decentralization to regional actors, and simplification of administrative processes. Conversely, common challenges include limited awareness among SMEs, lack of coordination between different policy levels, and insufficient support for microenterprises and low-tech firms [6,20,23].

The findings suggest that while financial incentives are necessary to lower the barriers to sustainability adoption, they must be embedded within broader policy narratives that promote innovation, inclusiveness, and long-term value creation. Without such integration, funding risks being perceived as transactional rather than transformational [21,65].

4.4. Technology and Innovation for Sustainability in SMEs

Technology and innovation are widely recognized as essential enablers of sustainable transformation in SMEs. Across the reviewed documents, digitalisation, green technologies, and eco-innovation are consistently emphasized as mechanisms for increasing resource efficiency, reducing emissions, and improving long-term competitiveness. Still, the degree to which these technologies are adopted—and the institutional support provided—varies substantially across the studied countries [8,25,27].

In Germany, the integration of technology and sustainability is a central policy priority. Documents from BMWK and BAFA highlight the strategic role of Industrie 4.0, artificial intelligence (AI), and energy-efficient machinery in supporting the green transition of SMEs. Programs such as “Mittelstand-Digital”, “go-digital”, and “Innovationsgutscheine” offer funding and advisory support for digital transformation projects with environmental goals. German SMEs are also increasingly involved in green tech clusters and pilot projects co-financed by public–private partnerships. Innovation is framed not only as a technological upgrade, but as a system-wide process involving collaboration, upskilling, and process redesign [38,39,48].

Poland has made significant investments in digital infrastructure and green technology funding—especially through FENG and the National Recovery Plan—but uptake among SMEs remains relatively low. PARP and Eurostat reports suggest that barriers such as lack of internal capacity, risk aversion, and limited R&D cooperation hinder broader adoption. However, targeted programs such as “GreenEvo” and regional “Living Labs” (e.g., in Kraków and Gdańsk) aim to bridge this gap by providing testbeds for sustainable innovations. While Polish policy increasingly references circular economy principles and low-carbon technologies, practical implementation among SMEs is still nascent and often dependent on external consultants or EU projects [9,36,40,66].

Spain demonstrates a growing emphasis on the intersection of technological and ecological innovation, particularly in response to climate resilience and energy transition goals. National and regional plans—such as the PRTR, “España Nación Emprendedora”, and “Pact for Science and Innovation”—promote digital solutions for smart agriculture, energy efficiency, and sustainable urban development. Innovation vouchers and sustainability labs have been established in regions like Valencia, Andalusia, and the Basque Country. Spanish SMEs are increasingly experimenting with blockchain for traceability, IoT for environmental monitoring, and renewable energy integration, but the ecosystem remains fragmented and largely sector-dependent [33,44,68,69].

Sweden presents the most mature and systemic approach to integrating technology and sustainability in SMEs. Reports from Vinnova, Tillväxtverket, and the Swedish Energy Agency describe a well-coordinated innovation system that includes co-financing, public R&D consortia, and sustainability incubators. Programs such as “Klimatklivet”, “Digital Leap”, and “Smart and Sustainable Cities” support SMEs in developing clean-tech solutions, applying circular design principles, and scaling impact-driven technologies. Swedish SMEs also benefit from proactive policies that link public procurement to environmental performance and reward innovation outcomes, not just activities. The cultural orientation toward experimentation, transparency, and ethical innovation further facilitates rapid diffusion of green technologies [33,44,68,69].

Across all four countries, documents emphasize the need for capacity building, access to test environments, and intermediary institutions that can translate complex technologies into SME-relevant applications. Barriers to adoption include not only cost and complexity, but also uncertainty about returns on investment and limited integration of sustainability into core innovation strategies. Facilitators include matchmaking platforms, cross-sectoral collaboration, and digital–green synergies supported by long-term policy frameworks [8,23,25,27].

Overall, the role of technology and innovation in SME sustainability is contingent not just on funding, but on ecosystem alignment, learning mechanisms, and leadership readiness to embed sustainability as a central innovation driver. Countries that combine technological capability with policy coherence—such as Sweden and Germany—achieve greater integration and scalability than those with more fragmented or reactive approaches [8,19,25].

This The thematic analysis of 35 policy and sectoral documents revealed significant variation in how sustainable leadership and strategic management are conceptualized and supported in the context of SMEs across the European Union. Despite the shared commitment to green and digital transitions, differences emerged in institutional capacity, strategic emphasis, and implementation depth among member states [20,22,23].

The comparison between national documents from Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden indicates divergent approaches to SME sustainability. German reports, particularly those by BAFA and INQA, emphasize structured support schemes, including mandatory energy audits and tailored funding for innovation ecosystems. Sweden, represented by Vinnova and government white papers, frames sustainability as a systemic innovation opportunity, embedding climate goals into regional development strategies [38,39,44,48,68].

In contrast, Polish reports (e.g., from PARP and InFiN) prioritize financial stabilization and digitalization but lack detailed mechanisms for leadership development or long-term ESG integration [9,40,66]. Spain policy, notably through ADEME, reflects a pragmatic blend of regulatory pressure and advisory support, encouraging SMEs to adopt low-carbon strategies through sector-specific roadmaps [55,56,57,67]. These differences highlight that while the overarching EU policy goals are harmonized, national implementation reflects distinct institutional logics, administrative cultures, and levels of ecosystem maturity [20,22,23].

Sustainable leadership was explicitly referenced in only 14 of the 35 documents, yet thematic analysis revealed implicit expectations across most sources. Documents issued by CSR Europe, SMEunited, and the European Commission promote transformational leadership as a catalyst for sustainability culture within SMEs [1,14,15,16]. Emphasis is placed on leadership that fosters employee engagement, ethical governance, and future-oriented thinking, particularly in transition sectors such as energy, construction, and manufacturing [1,42,43].

On the other hand, several national and industry-level reports acknowledge that most SMEs lack structured leadership development pathways. The responsibility for sustainability initiatives is often concentrated in owner-managers, whose personal values and capacities determine the firm’s direction [3,4,15]. This personalization of leadership is a double-edged sword: it allows for agility and authenticity but also creates inconsistency and vulnerability to economic shocks.

Strategic sustainability was more commonly and explicitly referenced across the corpus. Over two-thirds of the analyzed documents mentioned ESG reporting, carbon footprint tracking, or integration of circular economy principles into business models [10,19,29]. Industry associations and the OECD report a growing interest in rethinking value chains, with SMEs increasingly exploring digital tools, green design, and product lifecycle responsibility as components of strategy [20,42,43].

Nevertheless, several reports warn that many SMEs engage in sustainability reactively—often in response to regulatory requirements or client demands—rather than as part of a coherent strategic vision [6,23]. Document co-occurrence analysis revealed that strategic foresight and long-term planning are often missing from SME-related sustainability policies, especially in Eastern European contexts.

All countries examined provide some form of policy support for SME sustainability. Germany and Sweden stand out with mature instruments such as energy efficiency consulting, green vouchers, and innovation grants [38,44,48,68]. Spain provides sector-specific toolkits and carbon audits via ADEME [55,56,57], while Poland offers digital transition incentives through PARP [9,66].

At the EU level, horizontal strategies such as the Green Deal Industrial Plan and the SME Strategy set ambitious goals but leave implementation to member states [1,2]. The lack of harmonized standards and fragmented access to finance remain recurring concerns. Reports from the European Investment Fund and Eurochambres highlight the financing gap and recommend simplifying application procedures and creating ESG support hubs for SMEs [58,59].

A consistent theme across all documents was the central role of technology in enabling sustainable transformation. GreenTech Alliance, WBCSD, and Bruegel stress the importance of digitalization, automation, and clean energy solutions as levers for scaling SME sustainability [5,21,45]. Innovation funding, however, is often misaligned with SME capacity. Barriers include low awareness, administrative complexity, and the perception that sustainability innovation is costly or risky [6,23].

Evidence from several corpus documents (e.g., D15–D19, D22) and case examples—such as regional innovation platforms in Sweden or supply chain transformation pilots in Germany—indicates that SMEs play an important role in advancing green innovation when supported by targeted policies, ecosystem integration, and leadership training. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that these practices are not yet widely diffused across the EU landscape [33,38,69].

5. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight a clear tension between the ambition of sustainability policy frameworks and the reality of SME capabilities and leadership structures. While the European Union has laid a normative foundation for green and digital transformation through initiatives like the SME Strategy and the Green Deal Industrial Plan, the implementation of sustainable leadership and strategic management in SMEs remains uneven and heavily context-dependent [1,2,20,22].

Our findings refine the concept of sustainable leadership in SMEs in a multi-level governance perspective. First, whether leadership practices (vision, role modeling, employee development, innovation) translate into strategic sustainability integration depends on the density and “transitivity” of the institutional environment—that is, how accessible and navigable the portfolio of support instruments is (as shown in Table 4). Second, on-ramps—audits, advisory vouchers, simple reporting templates—act as a mediator that reduces informational and capability barriers; where present, leadership is more likely to yield durable strategic change (see Table 3, rows “Advisory & Networks”, “Standards & Toolkits”). Third, green–digital coupling strengthens SME dynamic capabilities: pairing environmental upgrades with digital measurement/control shortens implementation cycles and stabilizes outcomes (credible KPIs), a pattern more evident in systems with stronger measurement and easier access to instruments (see Table 4).

From these observations follow testable propositions for future research:

Proposition 1.

Instrument coverage and ease-of-access at country/region level moderate the relationship between leadership practices and strategic sustainability integration in SMEs.

Proposition 2.

The presence of on-ramps mediates the effect of institutional maturity on adoption speed (via reduced capability gaps).

Proposition 3.

Green–digital integration enhances dynamic capabilities, increasing the durability of strategic change in SMEs.

Three design principles stand out. First, simple entry points: widely available advisory vouchers, audits, and standards/toolkits lower transaction costs and initial uncertainty (as in Table 4), directly addressing barriers synthesized in Table 3. Second, sequencing: an effective mix stages advisory → small grants → investment finance, which broadens uptake among micro/small firms rather than only the most prepared. Third, outcomes measurement: embed effect metrics (e.g., energy savings, CO2e avoided, adoption rates) into programs and report them consistently; cross-country differences in measurement strength help explain performance gaps (Table 4).

Operationally, policymakers should match Table 3 barriers with targeted instruments from Table 4 (e.g., guarantees/tax relief for Costs & CAPEX; in-firm coaching and reporting training for Capabilities; one-stop shops and application “wizards” for Regulatory complexity; and green public procurement/sector standards to de-risk demand uncertainty). For SME leaders—especially in lean structures—role modeling, people development, and controlled experimentation help embed sustainability when coupled with accessible on-ramps and measurable goals. System-level actions include strengthening intermediaries (chambers, clusters, regional centers) as diffusion channels for transferable practices, setting minimum regional access standards, and bundling green investments with digital monitoring (IoT/EMS) to lock in performance gains.

One of the key insights from the document analysis is that leadership remains a critical yet underdeveloped driver of sustainability in SMEs. Although transformational and ethical leadership discourses are increasingly promoted in policy and industry reports [11,12,43], the operationalization of these leadership models is rarely supported through dedicated training, mentorship, or structured guidance—especially in Central and Eastern Europe [9,40,66]. As previous literature has noted, owner-managers in SMEs often serve as both the ethical and strategic center of the firm [3,4,15], and their personal orientation towards sustainability can determine whether any transformation occurs at all. This suggests that policy instruments should more directly target leadership development alongside financial and technological support [21,65,70].

Based on interviews with representatives of SMEs in the United Arab Emirates, they found that after the COVID-19 pandemic, sustainable leadership styles became dominant, replacing transactional approaches. This aligns with our observation that in Germany and Sweden leadership is increasingly framed in future-oriented, sustainability terms, while in Poland and Spain the framing remains pragmatic and short-term. The parallel suggests that crises, whether global pandemics or energy shocks, act as catalysts for embedding sustainability into SME leadership [25,30].

Moreover, the results confirm that strategic integration of sustainability into SME business models remains partial and reactive. While ESG frameworks and green innovation are mentioned across a majority of documents, implementation is frequently driven by regulatory pressure or supply chain requirements rather than internal strategic planning [6,23]. This aligns with studies arguing that SMEs often approach sustainability as a compliance burden rather than a source of value creation. Encouragingly, the Swedish and German cases demonstrate that when institutional ecosystems provide consistent and coordinated support—through green vouchers, advisory services, and innovation networks—SMEs are more likely to integrate sustainability proactively [38,44,48,68].

Policy fragmentation and asymmetry across EU member states also emerged as a structural challenge. Although the EU provides a general policy direction, national institutions vary significantly in their interpretation and delivery of sustainability programs. This disparity limits the scalability and comparability of SME sustainability performance across Europe and reinforces regional inequalities. Greater coordination and harmonization of SME-focused sustainability standards, metrics, and incentives could enhance the overall coherence of the EU’s sustainability agenda [20,33].

Finally, the role of technology and innovation as enablers of sustainability is well recognized, but documents caution that access remains uneven. Despite growing digitalization trends, many SMEs lack the absorptive capacity to take advantage of available green technologies and innovation funding schemes [8,25,27]. The literature suggests that innovation support must go beyond financing and include capacity-building, network facilitation, and experimentation spaces [21,65].

Taken together, these findings suggest that sustainability in SMEs cannot be fully achieved through policy mandates or financial incentives alone. Instead, a holistic approach is needed—one that combines institutional coherence, leadership development, strategic planning capacity, and embedded innovation ecosystems. Future research should investigate how these factors interact in different regional contexts and how SMEs themselves interpret and reshape sustainability narratives in practice [11,12,19].

Ndlovu et al. (2025) [25], in a bibliometric analysis of over 300 studies, show that SME performance research increasingly converges on three themes: digitalisation, sustainability, and innovation in business models. This confirms that our comparative framework, which integrates leadership, strategy, policies, barriers, and transferable practices, reflects the current state of SME research. Their analysis also underscores a research gap in cross-country comparisons, which our study begins to address by examining institutional discourse in four EU member states [28].

Overall, a simple mechanism emerges: when on-ramps (audits, advisory vouchers, templates) reduce information and capability gaps, leadership practices are more likely to translate into strategic integration (cf. Table 3); strong measurement further accelerates learning and scale-up [20,29]. Coupling green and digital agendas supports this process by enabling monitoring and circular models in SMEs [8,25,27].

6. Conclusions

The conducted analysis confirms that sustainable leadership and strategic management in SMEs are essential for achieving the goals of the green and digital transformation in the European Union. The findings indicate that although overarching EU strategies—such as the SME Strategy for a Sustainable and Digital Europe and the Green Deal Industrial Plan—provide a common framework, national implementation remains uneven. Germany and Sweden represent the most mature ecosystems, where sustainability is integrated into innovation policies, leadership narratives, and support mechanisms. In contrast, Poland and Spain still demonstrate a fragmented and reactive approach, where leadership is mainly focused on regulatory compliance and the use of funds rather than on long-term cultural or strategic transformation.

Leadership thus emerges as both a driver and a bottleneck of sustainable transformation. In most cases, responsibility rests with owner–managers, whose personal orientations shape the trajectories of pro-environmental action. This personalization enables flexibility but at the same time increases firms’ vulnerability to crises. The lack of structured leadership development pathways—particularly in Central and Eastern Europe—limits the potential for system-wide dissemination of sustainable practices. Strengthening leadership capacities, alongside financial and technological instruments, should therefore become one of the main priorities of public policy.

Technology and innovation are consistently recognized as key enablers of SME sustainability, especially when the green and digital transformations are pursued in parallel. However, their implementation is constrained by resource barriers, skill shortages, and administrative burdens, particularly for micro-enterprises. Examples from Sweden and Germany show that combining financial instruments with advisory services, standardized toolkits, and innovation networks fosters a more proactive integration of sustainability into business models.

The policy implications are clear: sustainable transformation in SMEs cannot be achieved through funding alone. It requires institutional coherence, clear measurement frameworks, and the presence of intermediary institutions that translate complex technologies and regulatory requirements into practices adapted to the realities of SMEs. Harmonizing standards and reducing fragmentation among member states would further enhance comparability and scalability of actions.

This study also underscores the necessity for future analyses to go beyond policy documents and examine how SMEs themselves interpret and reshape sustainability narratives in practice. Understanding these micro-foundations makes it possible to better capture how leadership, strategic management, and institutional ecosystems interact, and how SMEs can evolve from policy recipients into active participants in Europe’s green and digital transformation. Against this background, the multidimensional contribution of this work to the scientific literature becomes evident. This article integrates theoretical and policy approaches by linking the perspective of sustainable leadership with the analysis of strategic management and public policies toward SMEs, thereby making an important contribution to interdisciplinary scholarship by showing the mutual interactions of these three domains in practice. This study also offers a new perspective on the role of leadership in SMEs, confirming that owner–managers are central actors of transformation, while at the same time revealing insufficient institutional support for the development of their competencies. In this way, the focus shifts from large enterprises to SMEs, which play a crucial role in the European economy. The empirical contribution of this study lies in its comparative analysis of four EU countries—Germany, Sweden, Poland, and Spain—through qualitative document analysis (QDA/CDA), which made it possible to identify different institutional logics and levels of ecosystem maturity. This approach provides new data for the literature, which has so far rarely engaged in cross-country comparisons in this field. This work also makes a methodological contribution through the operationalization of the concept of “institutional maturity” and the introduction of tabular diagnostic tools that enable assessment of policy coherence, the depth of leadership narratives, the degree of strategy integration, and mechanisms for reducing barriers. Another contribution is the new perspective on the so-called twin transition—this article demonstrates how digitalization and ecological transformation reinforce each other in SMEs, while also identifying barriers that limit the absorptive capacity of these processes in different institutional contexts. Finally, this study presents important implications for the theory of dynamic capabilities, indicating that the crucial mechanism linking leadership intentions with the strategic integration of sustainability is the ability of firms to integrate external resources and engage in inter-organizational learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and I.M.; methodology, H.W. and I.M.; software, H.W. and I.M.; validation, H.W. and I.M.; formal analysis, H.W. and I.M.; investigation, H.W. and I.M.; resources, R.S. and A.K.; data curation, H.W. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., I.M., A.K. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and I.M.; visualization, H.W. and R.S.; supervision, H.W. and A.K.; project administration, H.W. and I.M.; funding acquisition, H.W. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Anchors for Table 5 (1–4 Scale)

4 = strong, system-wide; 3 = solid with minor gaps; 2 = emerging/fragmented; 1 = nascent.

Policies: presence of layered grants/loans, one-stop access, and KPI rules.

Leadership: explicit SME leadership framing in national/industry guidance and role-modeling.

Strategy: sustainability embedded in SME objectives and routines (beyond compliance).

Barrier-mitigation: instruments mapped to costs/skills/regulation with easy access.

Transferable practices: sector toolkits/templates and active diffusion via intermediaries.

Appendix B. Acronyms

| ADEME | French Agency for Ecological Transition |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BAFA | Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (Germany) |

| BIS | UK Department for Business, Innovation and Skills |

| BMI | Business Model Innovation |

| BMWK | Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (Germany) |

| BSR | Business for Social Responsibility |

| CA | Competent Authority (depending on context) |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditures |

| CDA | Comparative Document Analysis |

| COM | Communication (European Commission documents) |

| COSME | EU Programme for the Competitiveness of Enterprises and SMEs |