Abstract

Based on cross-sectional survey data from 574 grain farmers in Hebei Province, China, this study systematically analyzed, using an ordered Logit model and Bootstrap mediation effect tests, the mechanism by which information acquisition influences farmers’ adoption of green production technologies. The results showed that the diversity of information acquisition channels, content quality, and source credibility were all significantly and positively correlated with the degree of technology adoption, with content quality exhibiting the strongest correlation. Perceived usefulness played a partial mediating role between information acquisition and adoption behavior. Digital skills significantly and positively moderated the path through which information acquisition affects technology adoption—farmers with higher digital skills were more adept at converting information into technical knowledge and practices. Further heterogeneity analysis revealed that farmers with high digital skills in plain areas benefited more noticeably from information acquisition. Therefore, it is recommended that county-level agricultural technology extension centers take the lead in developing visualized technical materials to improve the quality of information content; conduct special digital skills training for elderly farmers to enhance their ability to acquire and identify information; and in regional practices, implement the supporting service of “targeted information & high-standard farmland” in plain areas while establishing a “technology demonstration household” dissemination network in mountainous areas. These measures will collectively form a differentiated and implementable technology promotion system, providing a feasible, practical path for advancing agricultural green transformation.

1. Introduction

Currently, global agriculture faces significant challenges in transitioning towards sustainability. Due to multiple pressures from climate change, resource constraints, and food security, the large-scale promotion and application of green production technologies have become a core pathway for achieving high-quality agricultural development [1]. However, despite continuous efforts by governments and international organizations to diffuse environmentally friendly technologies, the actual adoption rates of these technologies generally remain below expectations, especially in developing countries, where the adoption behaviour of smallholder farmers shows high heterogeneity [2]. In 2023, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) pointed out that the agricultural sector contributes approximately 23% to global greenhouse gas emissions, with Asia being the primary source of emission growth over the next thirty years [3]. In this context, China has proposed the “Dual Carbon Goals” (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals) and is deepening the green development of agriculture. Statistically, since the implementation of the Action Plan for Zero Growth in Chemical Fertilizer and Pesticide Use in 2015, the total usage of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in China has cumulatively decreased by 12.5% and 14.3%, respectively. However, the application amount per unit area still exceeds the world average by 2.5 times [4]. More notably, the adoption of green technologies shows significant disparities across regions and groups. In China, the coverage rate of integrated water and fertilizer technology in economically developed provinces like Jiangsu has exceeded 50%, while it remains below 15% in traditional western farming regions [5]. Furthermore, the technology adoption rate is generally higher among large-scale operators than among smallholder farmers. Smallholder farmers often face an adoption dilemma of “high intention but low behaviour” due to resource constraints, cognitive limitations, and risk aversion [6].

One key factor contributing to this adoption dilemma is the insufficient validity and reliability of farmers’ access to technical information. Currently, with the continuous development and popularization of digital technologies, the channels for disseminating agricultural technical information have expanded from traditional government extension and neighbour demonstrations to a multi-source heterogeneous system including internet platforms and social media [7]. However, information overload coexists with information fragmentation. Farmers often encounter practical obstacles such as difficulties in discernment, low trust, and slow conversion within this complex information environment [8]. The China Agricultural and Rural Informatization Development Report released in 2024 shows that although the rural internet penetration rate in China reached 68.7%, farmers relied on digital channels for only 31.5% of their agricultural production decisions. For information types like green production technologies, which involve complexity and long-term benefits, adoption decisions still heavily depend on traditional interpersonal networks and personal experience [9]. This low efficiency in information utilization does not stem from insufficient information supply but rather from structural differences in farmers’ ability to perceive and process information content [10]. Existing research indicates that farmers’ perceived usefulness of green technologies is a psychological mediating variable that facilitates their adoption decisions, and the formation of this perception heavily depends on the quality, source, and interpretation of the information they encounter [11,12].

However, digital skills play a crucial moderating role in this process. Digital skills are no longer limited to the ability to operate smart devices but encompass comprehensive literacy in information retrieval, screening, evaluation, and application [13]. As agricultural digital transformation accelerates, the intergenerational digital divide becomes increasingly prominent. A 2023 survey covering farmers in 17 provinces of China showed that only 28.9% of middle-aged and elderly farmers (over 50 years old) could independently use agricultural apps to obtain technical information, compared to 79.4% young farmers (under 35 years old) [14]. This intergenerational and regional disparity in skills directly affects farmers’ information processing efficiency and technological judgment ability. Those with high digital skills can more efficiently integrate multi-source information, forming a rational cognition of technology benefits and risks, thereby enhancing perceived usefulness. Conversely, those with low digital skills are prone to information anxiety or reliance on single sources, and may even develop technology aversion due to operational difficulties [15,16]. Therefore, revealing the moderating mechanism of digital skills in the relationship between information acquisition and perceived usefulness is significant for understanding the deep-seated reasons behind technology adoption disparities.

Although existing research has recognized the impact of information acquisition on technology adoption, obvious limitations persist. First, most literature treats information acquisition as a unidimensional variable, lacking a multidimensional deconstruction of its content quality, source credibility, and channel diversity, particularly neglecting the differences in information characteristics required by different technology types. Second, empirical evidence regarding perceived usefulness as a mediating variable remains relatively scattered and is often based on cross-sectional data, making it difficult to capture its dynamic formation process and feedback effects. More critically, the moderating role of digital skills has rarely been examined within a unified theoretical framework, especially how it interacts with farmers’ cognitive structures and social capital to influence technology perception and adoption behaviour. This gap hinders the revelation of the causal mechanism between “information-perception-behaviour”.

Addressing these research gaps, this paper takes the adoption of green production technologies by Chinese farmers as the empirical context to systematically explore the impact mechanism of information acquisition on farmers’ adoption behaviour, focusing on analysing the mediating role of perceived usefulness and the moderating effect of digital skills. In response to this, the subsequent structure of this paper is organized as follows: the Section 2 proposes research hypotheses based on relevant theories; the Section 3 elaborates on the study area, data sources, variable selection, and empirical model specification; the Section 4 presents and discusses empirical results, including descriptive statistics, main effects, mediating effects, moderating effects, and heterogeneity analysis; the Section 5 conducts in-depth dialogue between the findings of this study and existing literature, and explores its theoretical implications and research limitations; finally, the Section 6 summarizes the research conclusions and puts forward specific policy implications accordingly. The research findings will help guide governments and extension agencies to optimize information supply strategies. This will promote the efficient diffusion and the equitable access to green technologies, providing valuable theoretical insights and empirical references for sustainable agricultural development in China and other relevant countries.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Direct Impact of Information Acquisition on Farmers’ Adoption of Green Production Technologies

Information acquisition, as the foundation for farmers’ cognitive formation and behavioural decision-making, has a direct impact on the adoption of green production technologies [17]. In the context of agricultural green transition, technological information encompasses not only specific operational guidelines but also multidimensional content such as environmental benefits, policy support, economic returns, and market prospects. Farmers can access this information through various channels, including government extension systems, neighbour demonstrations, and social media. This allows them to comprehensively assess technologies’ applicability, economic viability, and potential risks, ultimately forming adoption intentions and putting them into practice [18,19]. Existing research shows that both the breadth (diversity of channels) and depth (accuracy and completeness of content) of information acquisition jointly influence farmers’ cognitive construction and decision-making confidence regarding green technologies [20]. When farmers can easily and cost-effectively access authoritative, practical, and understandable technical information, their adoption intentions and ultimately adoption rates are often higher. Particularly within China’s agricultural operational structure dominated by smallholders, information acquisition has become a key pathway to overcome technological cognitive barriers and mitigate the “intention-behaviour” gap [21]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Information acquisition has a significant positive impact on farmers’ adoption of green production technologies.

2.2. Mediating Role of Perceived Usefulness

Perceived usefulness, defined as an individual’s subjective judgment about whether a specific technology can bring them practical benefits, is a core cognitive variable in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [22]. Information acquisition profoundly influences farmers’ cognition and evaluation process of a technology’s usefulness by providing content related to technical performance, use cases, benefit data, and support policies [23]. For instance, by participating in training activities organized by the government or enterprises, farmers can systematically understand the principles, operational procedures, and long-term benefits of green technologies, thereby enhancing their adoption confidence. Perceived usefulness acts as a crucial psychological bridge converting external information into internal cognition in this process. It is noteworthy that since agricultural green technologies often feature characteristics like strong benefit lag and significant positive externalities, mere information exposure is insufficient to directly drive adoption behavior. The mediating role of perceived usefulness is essential to effectively translate technological information into behavioural motivation [24]. Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Perceived usefulness plays a mediating role between information acquisition and the adoption of green production technologies.

2.3. Moderating Role of Digital Skills

Digital skills represent the farmers’ comprehensive ability to effectively process, critically evaluate, and practically apply technical information in the modern information environment [25]. With the accelerating digital transformation of agriculture, digital skills have become a key moderating variable affecting the effectiveness of information acquisition and its subsequent conversion process [26]. Farmers with high digital skills can more efficiently utilize digital tools to quickly locate needed content from vast amounts of information, thereby enhancing their ability to judge the technology’s value and the efficiency of forming perceived usefulness [27,28]. Furthermore, the moderating effect of digital skills can be amplified through social networks. Farmers with high digital skills often act as “opinion leaders” in digital communities; their information interpretation, technical evaluations, and usage experiences diffuse through weak ties, subsequently influencing the technological cognition and adoption intentions of a broader farmer population [29,30,31]. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

Digital skills positively moderate the relationship between information acquisition and perceived usefulness.

H4.

Digital skills positively moderate the impact of information acquisition on the adoption of green production technologies.

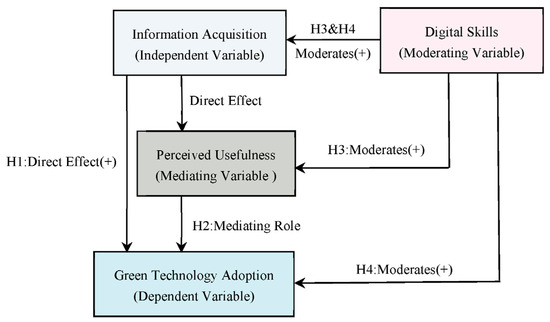

In summary, this paper integrates information acquisition, perceived usefulness, digital skills, and farmers’ adoption of green production technologies into a comprehensive analytical framework. The influence pathways among the variables are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Impact mechanism pathway.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

From July to August 2025, the research team organized 14 undergraduate and postgraduate students from the College of Economics and Management at Hebei Agricultural University to administer a questionnaire to 600 grain-growing farmers who grow millet and corn in Hebei Province. The specific implementation plan was as follows: First, based on the county-level digital village index from the “Hebei Province Digital Village Development Report (2024)”, all counties in the province were categorized into high, medium, and low tiers. Xinji City (representing high-yield farming areas with high-level digital infrastructure in the Piedmont Plain region), Quzhou County (representing key water-saving agricultural areas with medium digital infrastructure in the Low Plain region), and Zhangbei County (representing agro-pastoral areas with weak digital infrastructure but important ecological status in the Bashang Plateau region) were selected from each tier as primary sampling units. Second, five administrative villages were randomly selected from each sample county. Finally, 40 grain-growing households were selected from each village using a random number table sampling based on village household registration lists, ensuring the sample’s representativeness at the county and village levels. The questionnaire survey employed a combination of face-to-face interviews and electronic questionnaires. The research team prioritized electronic questionnaires with embedded technical operation videos for younger farmers with higher digital skills, while in-home interviews assisted by family members (e.g., children completing the form) were used for elderly farmers or those with difficulties in accessing digital resources to maximize both the response rate and data quality. After excluding questionnaires with missing key variables, logical contradictions, and invalid responses, 574 valid questionnaires were obtained, yielding an effective response rate of 95.7%. Furthermore, to effectively ensure data quality, the research team recruited Hebei Agricultural University students who passed a dialect test to conduct telephone verification on 15% of the sample for core items. The consistency between the verification results and the questionnaire data reached 95.2%. After questionnaire collection, this study conducted a systematic screening of missing values and found that the missing rate of key variables was less than 1.5%. Moreover, the missing pattern was confirmed to be missing completely at random (MCAR) through Little’s test (p > 0.05). Therefore, this study directly removed the samples with missing values, which did not cause systematic bias to the results. In addition, to ensure the rationality of the sample size, this study used GPower software (version 3.1.9.2) to conduct a priori power analysis. The minimum sample size calculated by GPower was 459, and the final valid sample size of 574 met this requirement and conformed to the sample size conventions of similar studies.

3.2. Variable Selection and Description

Based on the Technology Acceptance Model and the Digital Divide theory, this paper constructs an integrated analytical framework encompassing information acquisition, perceived usefulness, digital skills, and the adoption behaviour of green production technologies. To empirically test the causal relationships and mechanisms among these variables, this study selects five categories of variables—that is, the dependent variable, independent variables, mediating variable, moderating variable, and control variables. Their specific definitions and measurement methods are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Green Production Technology Adoption (GPTA) is the dependent variable of this study, referring to the extent to which farmers actually adopt green agricultural technologies in their production and management. Drawing on the research designs of Yang et al. [32] and Tong et al. [33], and considering the actual situation of agricultural green development in Hebei Province, this paper selects five representative green production technologies for measurement: water-saving irrigation technology, soil testing-based formulated fertilization technology, biopesticide technology, scientific straw returning technology, and green manure planting technology. In this study, the adoption status of the five technologies is summed and transformed into an ordinal categorical variable (as shown in Table 1). This operationalization not only reflects whether farmers adopt [the technologies] but also captures the depth and systematicity of adoption. Data acquisition is primarily conducted through a combination of field observations and structured interviews with farmers to ensure objectivity and accuracy.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Information Acquisition (IA) is the core independent variable of this study, referring to the breadth, quality, and credibility of information related to green production technologies acquired by farmers. Information acquisition is not a unidimensional concept but a multidimensional construct including channel diversity, content quality, and source credibility [34]. Therefore, this paper operationalizes it into three sub-variables: (1) Diversity of information acquisition channels (IA_Channel), measured by counting the number of different information channels used by farmers in the past year, including eight types: government agricultural technology extension stations, specialized cooperatives, neighbour demonstrations, internet search engines, agricultural apps, WeChat groups, short video platforms, and TV/radio broadcasts. (2) Quality of information content (IA_Quality), measured by a Likert 5-point scale asking farmers to evaluate the accuracy, practicality, and timeliness of the information they received, with the average score of these three dimensions used as the quality score. (3) Credibility of information sources (IA_Trust), also measured using a Likert 5-point scale to assess farmers’ trust levels in different information sources (government agencies, experts, relatives/friends, internet celebrities/self-media), with the average score calculated.

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

Perceived Usefulness (PU) is the mediating variable in this study, originating from the Technology Acceptance Model proposed by Davis (1989) [35]. It refers to farmers’ subjective perception and expectation of whether green production technologies can bring them practical benefits [36]. In the context of green production, perceived usefulness includes not only economic benefits but also environmental benefits and socio-psychological benefits [37]. Drawing on the scale design of Chen and Lu [38], this study asks farmers to evaluate each of the five green technologies across four dimensions: confidence in yield increase, cost-saving effect, environmental protection recognition, and policy benefits. We then calculate the average score across all items to form a continuous total perceived usefulness score. A higher score indicates stronger positive expectations towards green technologies and a greater likelihood of forming adoption intentions and converting them into actual behaviour.

3.2.4. Moderating Variable

With reference to the relevant research by Hao et al. [39], this study defines Digital Skills (DS) as a moderating variable. DS refers to farmers’ comprehensive ability to effectively acquire, evaluate, and apply technical information in the modern information environment. Moving beyond traditional simplistic measures like “whether using a smartphone”, this study employs a multidimensional digital literacy scale covering four dimensions: device operation ability, information retrieval ability, information evaluation ability, and technology application ability. This measurement method reflects not only the operational aspect of skills but also emphasizes higher-order literacy in cognitive and application aspects, effectively capturing the moderating role of the digital divide in the farmers’ technology adoption process.

3.2.5. Control Variables

To control for the potential influence of other factors on technology adoption behaviour, this study introduces the following control variables: (1) Age of the household head (Age), a continuous variable reflecting the influence of the life cycle on technology acceptance; (2) Education level (Edu), an ordinal categorical variable reflecting human capital stock; (3) Farmland operation scale (Land_Size), a continuous variable (ha) reflecting resource endowment and economies of scale; (4) Farming experience (Farm_Experience), a continuous variable reflecting agricultural experience and path dependency; (5) Annual household income (Income), a continuous variable reflecting economic constraints and risk-bearing capacity; (6) Ecological zone (Eco_zone), a categorical variable based on Hebei Province’s ecological functional zoning, controlling for natural and economic differences between regions. Data for these variables were primarily obtained through structured questionnaire surveys and village-level statistical records to ensure availability and reliability.

3.2.6. Reliability and Validity Tests of the Scale

To ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement results for the core scales (perceived usefulness and digital skills), this study conducted reliability and validity tests on these scales. For reliability, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was used for evaluation: the coefficient for the perceived usefulness scale was 0.79, and that for the digital skills scale was 0.84. Both exceeded the threshold of 0.7 (see Table 2), indicating good reliability of the scales. For validity, confirmatory factor analysis showed that the model had a good fit (χ2/df = 2.85, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.057). In addition, the factor loadings of all items were significantly greater than 0.6, the average variance extracted (AVE) of latent variables was greater than 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) of latent variables was greater than 0.8—these results indicate good convergent validity of the scales. Meanwhile, the square root of the AVE for each latent variable (bold values on the diagonal) was greater than the correlation coefficients between that variable and other variables (off-diagonal values), which indicates good discriminant validity of the scales (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity of the measurement scales.

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity: Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

3.3. Model Specification

3.3.1. Main Effect Model

Analysing the main effect of information acquisition on the adoption of green production technologies requires capturing the independent influence of the three types of independent variables: channel diversity, content quality, and source credibility [40]. Since the dependent variable GPTA is an ordinal variable with four categories, the ordered logistic regression model (ordered Logit model) can effectively handle the ordinal nature of the dependent variable and estimate the cumulative odds ratios for changes in the level of the adoption status. This model does not assume equal intervals for the dependent variable but requires the proportional odds assumption to be met, meaning the effect of the independent variables on the odds is the same across all categories [41]. Drawing on the modelling strategy for agricultural technology adoption behaviour from Liu et al. [42], the following ordered logistic regression model is constructed:

Let Y be the degree of farmers’ green technology adoption, taking values 0, 1, 2, 3. Its cumulative probability can be expressed as:

where = 0, 1, 2; is the intercept term; X is the vector of control variables, including Age, Edu, Land_Size, Farm_Experience, Income, and Eco_zone; are the regression coefficients for the three information acquisition variables, reflecting their marginal effects on the technology adoption level.

3.3.2. Mediating Effect Model

The mediating pathway of Perceived Usefulness (PU) between information acquisition and the adoption of green production technologies requires testing a causal chain. The Bootstrap method constructs confidence intervals for the mediation effect through repeated sampling. It is suitable for non-normal distributions and can handle mixed types of categorical dependent variables and continuous mediating variables, offering higher statistical power than the traditional Sobel test [43]. Following the mediation analysis framework of Xiong et al. [44], the following three-stage structural equation model is established:

First, the Perceived Usefulness equation:

Second, the direct effect equation for technology adoption (before including the mediator):

Finally, the joint path equation after adding Perceived Usefulness:

where the set of control variables is:

Conditions for establishing mediation: and are significant; simultaneously, after including PU, the coefficient for the independent variable should be less than the original coefficient , indicating a reduction in the direct effect. Bootstrap sampling is set to 1000 repetitions, and if the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval does not include zero, the mediation effect is considered significant.

3.3.3. Moderation Effect Model

The moderating effect of Digital Skills (DS) on the relationships between information acquisition and perceived usefulness, and between information acquisition and technology adoption, needs to be tested by introducing interaction terms [45]. A moderating variable changes the strength or direction of the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable, reflecting the dependency on the decision context [46]. For example, farmers with high digital skills might more effectively translate multi-channel information into technological cognition. This paper introduces interaction terms between the information acquisition variables and digital skills within the ordered logistic regression framework. The models are specified as follows:

Moderation on Perceived Usefulness (continuous dependent variable, using OLS regression):

Moderation on Technology Adoption behavior (ordinal dependent variable):

Here, IA represents any dimension of information acquisition (IA_Channel, IA_Quality, or IA_Trust), and DS is the digital skills score. If the interaction term coefficient or is significantly positive, it indicates that digital skills enhance the promoting effect of information acquisition on perceived usefulness or technology adoption; conversely, if it is negative, it means digital skills weaken this relationship.

3.3.4. Heterogeneity Analysis Model

To examine the heterogeneity of the moderating effect of digital skills across different groups, this study further employs a grouped regression model, complemented by the Chow test to identify the significance of coefficient differences between groups. This method avoids the strong assumption of parameter homogeneity inherent in full-sample interaction term models and is more suitable for revealing structural changes in moderating mechanisms [47,48,49]. This paper divides the sample into a high-skills group and a low-skills group based on the median digital skills score, estimates the model parameters for each group separately, and performs the Chow test:

High Digital Skills Group:

Low Digital Skills Group:

Chow Test Statistic:

where is the residual sum of squares from the pooled (full-sample) model, and are the residual sums of squares from the sub-samples, and k is the number of parameters. If the p-value associated with the F-test is less than 0.05, it indicates that the moderating effect of digital skills exhibits significant between-group differences.

4. Estimation Results and Analysis

The empirical results of this study are presented in the following seven sections. It should be noted that given the cross-sectional nature of our data, all reported effects represent associations rather than causal relationships.

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

After excluding samples with outliers, descriptive statistics were performed based on 574 valid sample data. Detailed statistical analysis results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4.2. Model Diagnostics and Basic Robustness Tests

Before reporting the core regression results, this study conducted a series of diagnostic tests on the model specification to ensure the validity of the estimation results.

First, we performed a multicollinearity test. This study uses the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess multicollinearity among independent variables. As shown in Table 5, the VIF values of all independent variables are far below the critical threshold of 10, and the maximum is only 2.47. This indicates that there is no severe multicollinearity in the model, and all variables can be included in the analysis simultaneously.

Table 5.

Variance inflation factor (VIF) test results.

Second, we conducted a diagnosis of outliers and influential observations. Influential cases were identified by calculating Cook’s distance and leverage values. The diagnostic results show that the Cook’s distance of all observations is less than 0.1, and no data point has a leverage value exceeding three times the average leverage value. This indicates that there are no influential observations in the data that would unduly affect the estimation of model parameters.

Finally, we evaluated the model’s goodness of fit. As shown in Table 6, in addition to the pseudo-R2, this study further provides more comprehensive model-fitting information. The likelihood ratio chi-square test of the model is highly significant at the 1% significance level. Furthermore, for the ordered Logit model, the Brant test fails to reject the model’s parallel lines assumption (PLA) (p-value = 0.124), which satisfies the prerequisite for the model’s application. The overall prediction accuracy of the model reaches 72.5%, which is a significant improvement compared to the overall prediction accuracy of the baseline model, indicating that the model has good explanatory power and goodness of fit.

Table 6.

Model goodness-of-fit and assumption test results.

4.3. Main Effect Analysis

The model met the proportional odds assumption assessed by the Brant test (p > 0.05). The regression results are shown in Table 7. The empirical results indicate that all three dimensions of information acquisition have significant positive effects on technology adoption behaviour, thus Hypothesis H1 is supported.

Table 7.

Main effect regression results (n = 574).

First, there is a significant positive correlation between the diversity of information acquisition channels and the degree of technology adoption (Coefficient = 0.317, OR = 1.373, p < 0.01). This indicates that for each additional information channel that a farmer uses, the probability of fully adopting green technologies increases by 37.3%. This result supports the view from Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory that “multiple channel exposure can reduce technological uncertainty” [50]. Particularly in the digital context, channel diversity helps farmers integrate online and offline information, forming a more comprehensive understanding of the technology.

Second, the positive association between the quality of information content and the probability of technology adoption is the strongest (Coefficient = 0.502, OR = 1.652, p < 0.01). For every one-level increase in information quality, the probability of full adoption increases by 65.2%. High-quality information, such as accurate technical parameters and timely policy interpretations, can effectively reduce farmers’ learning costs and cognitive biases, enhancing their expectations regarding the benefits of the technology. This finding indicates that content quality is the most fundamental dimension of information acquisition, thus directly determining the transformability of information into practical knowledge.

Third, there is a significant positive correlation between the credibility of information sources and technology adoption (Coefficient = 0.416, OR = 1.516, p < 0.01). For every one-level increase in farmers’ trust in information sources such as government agencies, agricultural experts, neighbours, and relatives, their adoption probability increases by 51.6%. Highly credible information sources not only provide authoritative content but also reduce farmers’ risk perception through the mechanism of social identity, which is particularly significant in long-term investment decisions such as green technology adoption.

Finally, regarding control variables, education level (Edu) and land size (Land_Size) are significantly associated with technology adoption, which also highlights the fundamental role of human capital and resource endowment in technology adoption. Farming experience (Farm_Experience) and age (Age) show slight negative effects, reflecting that older farmers or those with more experience may exhibit path dependency or hold more conservative technical views.

4.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

To test the mediating role of perceived usefulness between information acquisition and the adoption of green production technologies, this paper followed the mediation effect testing procedure proposed by Mkupete et al. [51], using the Bootstrap method with 1000 repeated samples to construct 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for verification. The mediation path analysis included the three core independent variables (IA_Channel, IA_Quality, IA_Trust), the mediator variable perceived usefulness (PU), and the dependent variable green production technology adoption (GPTA). All models controlled for the age of the household head, education level, land size, farming experience, household income, and ecological zone. The analysis results are shown in Table 8 and Table 9. The Bootstrap test results indicate that the confidence intervals for all three mediation paths do not include zero, and perceived usefulness plays a significant partial mediating role in each case, thus Hypothesis H2 is supported.

Table 8.

Test of the mediating effect of perceived usefulness (Bootstrap = 1000 times).

Table 9.

Decomposition of the mediating effect by dimensions of perceived usefulness.

First, the mediating path effect of information content quality through perceived usefulness is the largest (indirect effect = 0.152, proportion mediated = 35.4%). This suggests that high-quality information is most strongly associated with farmers’ positive perceptions of the technology’s usefulness, which in turn is correlated with adoption behavior. The underlying mechanism is that precise, practical, and timely information directly reduces the complexity and uncertainty of the technology, enabling farmers to more clearly anticipate the economic and environmental benefits post-adoption. This finding highly aligns with the core view of Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model, which posits that “perceived usefulness is the most direct antecedent of individual technology adoption”, and high-quality information is a key external stimulus shaping this perception.

Second, the mediating effect of information acquisition channel diversity (indirect effect = 0.138, proportion mediated = 32.1%) highlights the integrative advantage of multi-channel information exposure. Farmers obtaining information through multiple channels, such as government extension and social networks, can cross-verify and complement their learning, thereby forming a more comprehensive and stable judgment of the technology’s benefits. Notably, the path coefficient for the “yield confidence” dimension is the highest (β = 0.53), indicating that multi-channel information is more helpful in enhancing farmers’ confidence in the yield-increasing capacity of the technology, which is closely related to the long-standing “yield-oriented” decision-making tradition of smallholder farmers in China [52].

Third, the mediation path for information source credibility (indirect effect = 0.126, proportion mediated = 30.3%) reveals the socio-psychological mechanism of trust in knowledge transformation. Information from authoritative institutions like the government and research units, or from trusted acquaintances like relatives and friends, not only provides knowledge content but also conveys a signal of social endorsement, alleviating farmers’ psychological risk perceptions. Table 7 shows that the path coefficient from credibility to “cost saving” (β = 0.42) is relatively higher, indicating that farmers particularly believe information about cost reduction and efficiency improvement conveyed by reliable sources, as this directly relates to their operational profits and livelihood security.

4.5. Moderating Effect Analysis

To test the moderating role of digital skills (DS) in the relationship between information acquisition and the adoption of green production technologies, this study draws on the relevant research by Hao et al. [39], introduces interaction terms between the three dimensions of information acquisition and digital skills (IA_Channel × DS, IA_Quality × DS, IA_Trust × DS) into the baseline model, and employs a hierarchical regression approach for analysis. Model 1 uses perceived usefulness (PU) as the dependent variable (linear regression), and Model 2 uses technology adoption (GPTA) as the dependent variable (ordered logistic regression). All models controlled for the age of the household head, education level, land size, farming experience, annual household income, and ecological zone. The regression results are shown in Table 10. The coefficients of all three interaction terms are significantly positive, indicating that digital skills are significantly associated with a stronger relationship between information acquisition and both perceived usefulness and technology adoption. Thus, both Hypotheses H3 and H4 are supported.

Table 10.

Regression results for the moderating effect of digital skills.

First, digital skills significantly and positively moderate the relationship between information acquisition and perceived usefulness. The coefficients of the three interaction terms are 0.138, 0.173, and 0.126, respectively, all significant at the 1% level. This indicates that for farmers with high digital skills, their information acquisition capability can be more effectively translated into a positive perception of the usefulness of green technologies. It is particularly noteworthy that the interaction effect between information quality and digital skills is the strongest (β = 0.173), suggesting that farmers with high digital skills are better at discerning, understanding, and applying high-quality technical information. Thus, digital skills are not merely a tool-using ability but a higher-order capability for information processing and cognitive construction, effectively reducing learning costs and the comprehension threshold of technical information.

Second, digital skills also positively moderate the relationship between information acquisition and technology adoption behavior. The coefficients of all three interaction terms in Model 2 are significantly positive, indicating that farmers with high digital skills exhibit a higher propensity for technology adoption at the same level of information exposure. Simple slope analysis revealed that in the high digital skills group (DS ≥ median), the marginal effect of information quality on adoption behavior was 0.685 (p < 0.001), while that in the low skills group (DS < median), this effect decreased to 0.327 (p < 0.05). This difference highlights the crucial role of digital skills in bridging the “information-behavior” transformation channel [53]. Highly skilled individuals can overcome the “last mile” obstacle, translating cognitive advantages into practical actions, thereby significantly reducing the transaction costs and operational uncertainties of the adoption process.

Third, the moderating effect exhibits dimensional heterogeneity, with the synergistic effect between information quality and digital skills being the most prominent. The coefficient for IA_Quality × DS is higher than those of the other two interaction terms, both in enhancing perceived usefulness and directly affecting adoption behavior. This suggests that the role of digital skills is particularly dependent on the quality of the information itself. Given that the information is accurate, practical, and timely, farmers with high digital skills can maximize their information processing advantages. The policy implication of this finding is that in promoting the digital transformation of agriculture, the principle of “quality first” must be adhered to, and it is essential to both enhance farmers’ digital skills and strengthen the source governance and content construction of technical information, achieving a dual drive of “skill empowerment” and “information quality improvement”.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

First, the total sample was divided into a high-skills group (DS ≥ 3) and a low-skills group (DS < 3) based on the median digital skills score. Grouped regression analysis and Chow test (a test for structural differences in regression coefficients) were used to examine the robustness and structural differences in the moderating effects. Second, based on Hebei Province’s ecological functional zoning, the sample was divided into plain areas (including piedmont plains and low plains) and mountainous areas (including the Bashang plateau) to analyse the heterogeneity of the role of information acquisition under different resource and environmental constraints. The analysis results are shown in Table 11 and Table 12.

Table 11.

Grouped regression results by digital skills (Chow test: F = 6.84, p = 0.009).

Table 12.

Regional heterogeneity analysis results (Chow test: F = 5.27, p = 0.022).

On one hand, the heterogeneity analysis of digital skills reveals a significant “capability divergence” effect. In the high digital skills group, the promoting effects of all three dimensions of information acquisition are substantially higher than in the low skills group. Taking information quality as an example, the regression coefficient in the high-skills group is 0.785 (OR = 2.193), which is 1.95 times that of the low-skills group (coefficient = 0.402, OR = 1.494). This means that the greater adoption probability associated with an improvement in information quality is nearly twice as high in the group with higher digital skills. This significant gap highlights the key role of the digital divide in technology diffusion, and the information advantages of farmers with high digital skills are significantly associated with their cognitive and behavioral advantages.

On the other hand, the heterogeneity analysis based on ecological regions indicates that the impact mechanism of information acquisition is profoundly moderated by regional resource environments and characteristics of technological demand. In plain areas, the promoting effect of information quality is most prominent (coefficient = 0.587, OR = 1.799). This stems mainly from the scaled and intensive production characteristics of plain farming areas, where farmers have higher requirements for the accuracy and practicality of information regarding complex technologies like water-saving irrigation and precision fertilization. High-quality information can directly meet their technological needs and verification processes. Conversely, in mountainous areas, the role of information channel diversity is stronger (coefficient = 0.401, OR = 1.494), reflecting the reality of relatively weak information infrastructure and insufficient coverage of formal technology extension systems in these regions. Farmers consequently rely on multiple channels to piece together fragmented information, where the complementarity and accessibility of channels become key constraints on their technical cognition.

In addition, to test the statistical significance of the grouped regression coefficients, given the nonlinear nature of the ordered Logit model, we mainly use the likelihood ratio test, which is more applicable than the Chow test. The results show that the coefficient differences between the groups divided by digital skills (χ2 = 15.32, p = 0.004) and between the groups divided by ecological regions (χ2 = 12.75, p = 0.012) are both statistically significant. The results of the Chow test—used as a reference for linear models—are consistent with these likelihood ratio test results, and the two sets of findings collectively confirm the existence of heterogeneity.

4.7. Robustness Check

To ensure the reliability of the above research conclusions, this study conducted robustness tests. The analysis results are shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

Comparison of robustness check results.

The Results in Table 11 show the following: First, in the MLRM estimation, the coefficient direction, significance level, and magnitude of OR values of the core independent variables are highly consistent with those of the baseline OLRM. This indicates that the promoting effect of information acquisition on technology adoption is robust, regardless of whether the variables are assumed to have interval properties. Second, the coefficients and significance levels of the newly constructed variables are highly consistent with those of the original variables. This suggests that the mechanism of information acquisition is not sensitive to its measurement method, which further supports the reliability of the conclusions regarding the main effect and moderating effect. Third, after winsorizing the continuous variables at the 1% upper and lower tails and re-estimating, there is no substantial change in the significance or direction of the key variables; consistent conclusions are also obtained using OLS as an alternative estimation method. Fourth, although this study has controlled for the main confounding factors that may affect technology adoption through theoretical analysis, we must acknowledge the possibility of residual endogeneity. Therefore, addressing endogeneity should be a key direction for future research to pursue through panel data tracking or rigorous field experimental design.

5. Discussion

This study develops an integrated framework of “information acquisition–perceived usefulness–technology adoption” and incorporates the moderating role of digital skills. The research findings effectively responded to the key research gaps identified in the Introduction and provide a more comprehensive and realistic analytical framework for understanding and promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

First, by deconstructing information acquisition as a multi-dimensional construct, this study transcends traditional approaches that solely measure channel diversity. While Miriam et al. [54] correctly emphasized the primacy of information quality, our results demonstrate that channel diversity and source credibility exert significant and independent effects on technology adoption. This reveals that smallholder farmers in China rely on a composite decision-making logic driven by quality, channel complementarity, and trust assurance—rather than singular information exposure. This finding significantly deepens our understanding of the role of information in agricultural innovation diffusion. Second, the verified mediating role of perceived usefulness provides robust empirical support for the applicability of technology acceptance models (TAM) in complex green agricultural technology contexts. More importantly, our findings extend Davis’ seminal work by identifying differentiated pathways through which distinct information dimensions shape perceived usefulness [55]. Information quality remains the strongest predictor of perceived usefulness, whereas credible sources are particularly effective in enhancing farmers’ confidence in cost savings. This indicates that perceived usefulness is not a unidimensional construct; instead, it is cultivated through the differentiated processing of specific information types. This provides a more nuanced understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking external information to adoption willingness. Finally, the digital divide extends beyond mere access to digital tools; its critical dimension lies in the effective utilization of these digital tools to process and evaluate information. The information advantages of farmers with high digital skills are significantly and positively correlated with stronger perceived usefulness and a higher probability of technology adoption—consistent with the cross-sectional associations observed in our analysis—which suggests that digital literacy is not a peripheral factor, but a key boundary condition associated with the efficiency of the “information-perception-behavior” conversion path, thereby integrating a key dimension of social inequality into the technology adoption model.

However, this study also has certain limitations: First, although we have controlled for a wide array of observable confounders and have been cautious in interpreting the results as associations, the possibility of residual endogeneity due to unobserved factors (e.g., innate farmer ability or motivation) or reverse causality persists. This is a common challenge in cross-sectional studies. While we considered empirical methods such as instrumental variables, the difficulty in identifying a variable satisfying the exclusion restriction prevented its application. Therefore, addressing endogeneity remains a key direction for future research, which should prioritize the collection of panel data or the design of randomized controlled trials to more robustly establish causality. Second, common method bias may affect the estimation of variable relationships. Although the questionnaire design incorporated multi-time-point assessments and reverse-coded items, self-reported data may still be influenced by social desirability bias. Third, while the sample is representative within Hebei Province, its external validity still needs to be tested in broader geographical and economic contexts; Fourth, differences across technology types have not been fully explored. Although combining five technologies into a composite index can reflect the breadth of adoption, it may obscure the differential impacts of distinct technological attributes (e.g., complexity, compatibility) on adoption decisions. Additionally, the formation of perceived usefulness warrants further in-depth exploration. Information acquisition may influence farmers’ attitudes by altering their risk assessments of technology benefits or through subjective norms, while digital skills may accelerate this process by enhancing perceptions of technology compatibility.

To address the limitations of this study and provide a clear roadmap for future research, it is suggested that future work should aim to address the following directions: First, panel data or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) should be used to more robustly identify the causal relationships between variables. Second, future studies should further explore how social network structures interact with digital skills to influence the flow of technological information and trust building. Third, future studies need to separate and compare different types of green technologies to reveal the heterogeneous impacts of technological attributes on adoption decisions.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of the study show that all three dimensions of information acquisition, namely channel diversity, content quality, and source credibility, are significantly and positively correlated with the degree of technology adoption, supporting Hypothesis H1; Perceived usefulness plays a partial mediating role between information acquisition and technology adoption—with the mediation effect accounting for 32.1–35.4%—thus supporting Hypothesis H2; Digital skills significantly and positively moderate the impact of information acquisition on technology adoption, supporting Hypotheses H3 and H4; Heterogeneity analysis results indicate the following: the promoting effect of information acquisition is stronger among farmers with high digital skills; Plain areas rely more on high-quality information, while mountainous areas rely more on multi-channel complementarity, reflecting significant group and regional differences.

Based on the above conclusions, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations: First, a set of standardized local dialect video tutorials for core technologies (e.g., water-saving irrigation, soil testing-based formulated fertilization) should be developed, led by county-level agricultural technology extension centers and in collaboration with research institutions. These tutorials should intuitively demonstrate operational procedures and quantitative benefits to effectively improve the quality and comprehensibility of information content. Second, for groups with weak digital skills, agricultural and rural affairs departments should take the lead in designing a 3-month pilot training program titled “Digital Assistance for Farmers”. The curriculum should cover practical skills such as information retrieval and credibility assessment, and the proportion of farmers who are able to independently use agricultural technology-related APPs to obtain technical information after completing the program should be set as a key assessment indicator. Third, policy design should reflect regional and group heterogeneity. A “two-way targeted” intervention strategy can be implemented. In intensive farming areas such as plains, the focus should be on providing high-precision, professional technical information and matching support services. In mountainous regions and areas with an underdeveloped information infrastructure, priority should be given to broadening information dissemination channels. This can be achieved by leveraging the complementary advantages of traditional channels—such as agricultural cooperatives and neighbor-led demonstrations—alongside new media platforms to enhance information accessibility. Fourth, the reinforcing effects of social networks and the policy environment should be fully utilized. The efficiency of green production technology information dissemination can be enhanced by establishing a “digital community for agricultural technology extension” based on social media, leveraging the role of highly skilled farmers as opinion leaders to drive farmers with low digital skills to improve their own digital skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y.; Methodology, W.Y.; Software, W.Y.; Validation, J.Z.; Formal analysis, W.Y.; Investigation, W.Y. and J.Z.; Data curation, M.H., Y.F. and S.X.; Writing—original draft, W.Y.; Writing—review & editing, M.H., Y.F. and S.X.; Supervision, J.Z.; Funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 21BSH088), the Industrial Economics Position of the Grape Innovation Team in the Modern Agricultural Industrial Technology System of Hebei Province, China (Grant No.: HBCT2021230301), and the Special Research Program for Independent Talent Development of Hebei Agricultural University (Grant No.: 3005028). And the APC was funded by the Special Research Program for Independent Talent Development of Hebei Agricultural University (Grant No.: 3005028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nguyen, L.L.H.; Khuu, D.T.; Halibas, A.; Nguyen, T.Q. Factors that influence the intention of smallholder rice farmers to adopt cleaner production practices: An empirical study of precision agriculture adoption. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 692–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, D.; Börner, J. Innovation context and technology traits explain heterogeneity across studies of agricultural technology adoption: A meta-analysis. J. Agric. Econ. 2023, 74, 570–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos, C.; Charoula, D. Factors shaping innovative behavior: A meta-analysis of technology adoption studies in agriculture. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2025, 71, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Xue, W.; Huo, X.X. Fertilizer application training programs, the adoption of formula fertilization techniques and agricultural productivity: Evidence from 691 apple growers in China. Nat. Resour. Forum. 2025, 47, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.; Khan, A.; Ke, S.F. Organizational support, market access, and farmers’ adoption of agricultural green production technology: Evidence from the main kiwifruit production areas in Shaanxi Province. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 11912–11932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.J.; Shi, R.; Yao, L.Y.; Zhao, M.J. Perceived value, government regulations, and garmers’ agricultural freen production technology adoption: Evidence from China’s Yellow River basin. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; De Rosa, M.; Vecchio, Y.; Adinolfi, F. The long way to innovation adoption: Insights from precision agriculture. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Ganjkhanloo, M. Understanding farmers’ ecological conservation behavior regarding the use of integrated pest management: An application of the technology acceptance mode. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.L.; Xu, M. The role of social interaction in farmers’ water-saving irrigation technology adoption: Testing farmers’ interaction mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, C.A.; Kazeem, A.A.; Enitan, O.F.; Olawunmi, F.A.A.; Tsugiyuki, M.; Toshiyuki, W. Effect of information sources on farmers’ adoption of Sawah eco-technology in Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2020, 24, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Luo, G.Q. Ecological cognition, digital agricultural technology adoption and the sustainable development of family grain farms—An empirical study from China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 178201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.X.; Zhu, Y.R.; Ma, Y.Q.; Chen, S.J. Willingness of tea farmers to adopt ecological agriculture techniques based on the UTAUT extended model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLay, N.D.; Thompson, N.M.; Mintert, J.R. Precision agriculture technology adoption and technical efficiency. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 73, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Drabik, D.; Zhang, J.B. How channels of knowledge acquisition affect farmers’ adoption of green agricultural technologies: Evidence from Hubei province, China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2270254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, J.; Madureira, L.; Marques, C.; Silva, R. Understanding Farmers’ Adoption of Sustainable Agriculture Innovations: A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavi, S.; Anandaraja, N.; Murugan, P.P.; Latha, M.R.; Selvi, R.P. Challenges and strategies of resource poor farmers in adoption of innovative farming technologies: A comprehensive review. Agric. Syst. 2025, 227, 137734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Feng, Y.N.; Li, Y.F.; Zheng, K. Can different information channels promote farmers’ adoption of Agricultural Green Production Technologies? Empirical insights from Sichuan Province. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, N.; Hayati, D. A systematic review on selection and comparison of holistic agricultural sustainability assessment approaches. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1559503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Zhu, M.D.; Zuo, Q.L. Social network, production purpose, and biological pesticide application behavior of rice farmers. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 834760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Fan, Q.Q.; Jia, W. How much did internet use promote grain production?-evidence from a survey of 1242 farmers in 13 provinces in China. Foods 2022, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Lyu, K.Y.; Li, J.C.; Shiu, H. Bridging the digital divide for rural older adults by family intergenerational learning: A classroom case in a rural primary school in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Long, F. The impact of value cognition and institutional environment on the quality and safety control behavior of major producers of grain and its intergenerational differences. J. Hunan. Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 24, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Sheng, G.J.; Sun, D.S.; He, R. Effect of digital multimedia on the adoption of agricultural green production technology among farmers in Liaoning Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 6, 13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Z.Y.; Liu, H. Farmers’ adoption of agriculture green production technologies: Perceived value or policy-driven? Heliyon 2024, 10, e23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, J. Need for Cognitive Closure, Information acquisition and adoption of green prevention and control technology. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2021, 28, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.Y.; Jiang, L.D.; Yu, Z.G. Can Digital human capital promote farmers’ willingness to engage in green production? Exploring the role of online learning and social networks. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratana, S.; Ajchamon, T. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Farmers’ Adoption of Organic Farming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.K.; Luo, L.; Chen, C.Y.; Qiu, L. How does social learning influence Chinese farmers’ safe pesticide use behavior? An analysis based on a moderated mediation effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.F.; Li, J. Realising the potential of information acquisition in promoting sustainable agriculture: A systematic review. J. Inf. Sci. 2024, 11, 93772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.H.; Zheng, S.F.; Lu, Q. Social network, internet use and farmers’ green production technology adopting behavior. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.H.; Zheng, S.F. The impact of information on acquisition channels on farmers’ green control technology behavior. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.F.; Zheng, S.F.; Yang, N. The impact of information literacy and green prevention and control technology adoption behavior on farmers’ income. J. Ecol. Agric. China 2020, 28, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; He, L.J.; Wang, Y.Q. Subsidy policy, effect cognition of environment-friendly pest control and adoption of environment-friendly pest control: Based on investigation of main apple growing areas in Shaanxi Province. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2020, 40, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.; Boden, B.; Gunter, K.; Paul, B. Analyze the relationship among information technology, precision agriculture, and sustainability. J. Commerc. Biotechnol. 2022, 27, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, S.; Kaur, M.; Singh, K.Y. Constraints in Adoption of Improved Kinnow Production Technology in Rajasthan, India: The Farmers Perspective. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2024, 46, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kaida, N. Parent-child intergenerational associations of environmental attitudes, psychological barriers, and pro-environmental behaviors in Japan and China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lu, Y.H. Factors influencing the information needs and information access channels of farmers: An empirical study in Guangdong, China. J. Inf. Sci. 2020, 46, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. The impact of digital capability on farmers’ adoption of green production technologies: Evidence from the middle-upper Yellow River basin. Res. Agric. Mod. 2025, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, B.L. Three Generations under one roof: The impact of intergenerational knowledge transfer on the pro-environmental behaviors of rural households. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2024, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Chai, Y.J.; Chen, S.J. Land tenure and green production behavior: Empirical analysis based on fertilizer use by cotton farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Luo, X.F.; Yu, W.Z.; Huang, Y.H. Analysis of the Influence of Intergenerational Effect and Neighborhood Effect on Farmers’ Adoption of Green Production Technology. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzanku, F.M.; Osei, R.D.; Nkegbe, P.K.; Osei-Akoto, I. Information delivery channels and agricultural technology uptake: Experimental evidence from Ghana. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2022, 49, 82–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.X.; You, C.X.; Zhu, S.B. Effect of digital technology application on grain grower’s behavior of green production technology adoption. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plann. 2025, 46, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, K.; Ward, P.S.; Lybbert, T.J.; Spielman, D.J. Intrahousehold preferences heterogeneity and demand for labor-saving agricultural technology. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 2024, 106, 684–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaumi, F.K.; Nyambane, C.O.; Karega, L.N.; Rasugu, H.M. Effect of on-farm testing on adoption of banana production technologies among smallholder farmers in Meru region, Kenya. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 13, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martey, E.; Etwire, P.M.; Mockshell, J. Climate-smart cowpea adoption and welfare effects of comprehensive agricultural training programs. Technol. Soc. 2024, 64, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambio, Y.; Deb, A.; Kazianga, H. Exposure to agricultural technologies and adoption: The West Africa agricultural productivity program in Ghana, Senegal and Mali. Food Policy 2022, 113, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissillour, R.; Essiz, O.; Boninsegni, M.F.; Song, Z.P. Intergenerational transmission of sustainable consumption practices: Dyadic dynamics of green receptivity, subjective knowledge, peer conformity, and intra-family communication. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 378, 124754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkupete, M.J.; Davalos, J. Implications of climate-smart agriculture technology adoption on women’s productivity and food security in Tanzania. Agric. Econ. 2025, 56, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.L.; Lyu, J.; Ge, C.D. Knowledge and farmers’ adoption of green production technologies: An empirical study on IPM adoption intention in major India-Rice-Producing areas in the Anhui province of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.B. The impact of government subsidies and quality certification on farmers’ adoption of green pest control technologies. Agriculture 2025, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriam, V.; Belia, S.; Jolanda, L. How young adults view older people: Exploring the pathways of constructing a group image after participation in an intergenerational programme. J. Aging Stud. 2021, 56, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.P.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhang, K.; Xu, D.D.; Qi, Y.B. The impacts of farmer ageing on farmland ecological restoration technology adoption: Empirical evidence from rural China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).