Abstract

This study presents the design, modeling, and multi-platform simulation of NEPTUNE-R, a solar-powered autonomous hydro-robot developed for sustainable water purification and oxygenation. Mechanical design was performed in Fusion 360, trajectory optimization in MATLAB R2024a, and dynamic motion analysis in Roblox Studio, creating a reproducible digital twin environment. The proposed path-planning strategies—Boustrophedon and Archimedean spiral—achieved full surface coverage across various lake geometries, with an average efficiency of 97.4% ± 1.2% and a 12% reduction in energy consumption compared to conventional linear patterns. The integrated Euler-based force model ensured stability and maneuverability under ideal hydrodynamic conditions. The modular architecture of NEPTUNE-R enables scalable implementation of photovoltaic panels and microbubble-based oxygenation systems. The results confirm the feasibility of an accessible, zero-emission platform for aquatic ecosystem restoration and contribute directly to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6, 7, and 14 by promoting clean water, renewable energy, and life below water. Future work will involve prototype testing and experimental calibration to validate the numerical findings under real environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

The deterioration of water quality in natural aquatic ecosystems, caused by pollution and eutrophication, has led to increasing interest in sustainable and autonomous purification and oxygenation solutions. In this context, solar-powered robotic systems have emerged as promising technologies, particularly for oxygenating water bodies and restoring ecological balance. The NEPTUNE-R prototype aligns with this trend, proposing a low-cost, autonomous solution that uses dissolved oxygen injection and dynamic surface coverage for surface water treatment.

Recent studies have demonstrated the efficiency and feasibility of such systems. For example, Osuch et al. [1] presented a solar-powered pulverizing aerator designed for hypolimnetic lake restoration, which operated continuously for over 6500 h, injecting significant amounts of oxygen with minimal energy losses. In another application, Prasetyaningsari et al. [2] optimized a fully autonomous solar aeration system for a rural carp breeding pond, using HOMER software to ensure adequate dissolved oxygen supply, especially during nighttime when oxygen demand is higher.

Similarly, a floating solar-powered aeration system equipped with dissolved oxygen sensors and GSM-based automatic control was shown to rapidly increase DO levels (by 1.32 ppm in 10 min) while achieving high energy efficiency, with a Standard Aeration Efficiency (SAE) of 0.2710 kg O2/hp-h [3]. In the cited studies, the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was measured using optical or galvanic DO sensors based on membrane diffusion principles. These devices detect oxygen partial pressure via electrochemical or luminescent response, providing a precision of ±0.1 mg/dm3 and response times below 5 s under typical aquatic conditions. For simulation purposes, the temporal variation in DO concentration (ΔDO/Δt) was modeled using empirical mass transfer correlations reported for microbubble aeration systems, corresponding to DO increases of 1.5–2.0 mg/dm3·h−1 in comparable laboratory-scale water volumes.

The increasing integration of solar energy into aquaculture and water treatment is also emphasized in review studies by Vo et al. [4,5], who outlined the sector’s transition from fossil fuels toward renewable energy sources. According to their findings, incorporating photovoltaic (PV) systems—including floating solar panels—into fish farming operations is not only technically feasible but also economically viable, particularly in remote areas with no access to the electrical grid.

Pratama et al. [6] also confirmed that a solar-powered floating aerator could significantly raise DO levels in isolated tanks, from about 3.5 mg/dm3 to over 4.5 mg/dm3, contributing to the stabilization of the aquatic environment.

The benefits of floating photovoltaic (FPV) systems were further highlighted by Manolache et al. [7], Sahu et al. [8], and Dzamesi et al. [9], who emphasized their improved performance due to natural water-based cooling, reduced water evaporation, and inhibition of algal growth. However, they also identified challenges such as corrosion risks and the lack of standardized local design guidelines.

The techno-economic optimization of such systems has been explored in the literature by the authors of [10,11], who compared standalone PV-powered paddlewheel aerators to those integrated with battery energy storage systems (BESs). A 21-day experimental campaign revealed that the PV/BES system consistently outperformed the PV-only configuration in improving dissolved oxygen levels, with average DO increases of 10.91%, and peaks of up to 17.83% during rainy days, confirming the enhanced stability and reliability offered by energy storage. Complementing these findings, the authors of [12] proposed a direct analytical method to estimate PV energy requirements for aeration tanks in wastewater treatment plants, based on ambient air temperature and standard water quality parameters (such as BOD5 and VSS). This method allows for simplified system sizing without requiring detailed energy monitoring, thus supporting the broader integration of renewable energy in urban water treatment infrastructures.

Recent studies highlight the transition from single-unit solar water robots to collaborative multi-agent systems designed for environmental restoration [13,14,15,16,17], proposing an approach based on a PID algorithm to minimize energy consumption and execution time in pick-and-place operations. Additionally, the impact of arm configurations on energy efficiency is analyzed, and strategies are suggested to further reduce energy consumption. Similarly, [18,19] and [20] introduced microbubble oxygenation modules with nano-structured diffusers, achieving oxygen transfer coefficients (aKL above 0.85 h−1).

NEPTUNE-R introduces an original integration of solar energy harvesting, dynamic trajectory planning, and modular oxygenation components within a single autonomous platform capable of continuous and adaptive operation. By addressing water quality restoration through renewable-energy-based autonomous systems, this paper contributes to the sustainability transition and directly supports the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (for SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation); simulations indicate an average increase of 1.2–1.8 mg/dm3 in dissolved oxygen after 2 h of operation in a 50 m × 30 m water body; for SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), the use of optimized Boustrophedon and Archimedean trajectories reduces power demand by approximately 12%; for SDG 14 (Life Below Water), maintaining DO above 5 mg/dm3 contributes to improving aquatic biodiversity and reducing anaerobic zones by about 20%).

Recent developments in autonomous robotics also demonstrate how visual perception and advanced motion planning methods can enhance environmental adaptability. For instance, 3D vision systems for damage recognition in construction robots [21,22,23] and kinematically constrained bidirectional RRT algorithms for unstructured agricultural environments [24,25] illustrate the progress in real-time navigation and intelligent control. Although these systems operate in terrestrial domains, their underlying optimization principles align with the adaptive trajectory and force-based control implemented in NEPTUNE-R, reinforcing the broader relevance of this research to the field of autonomous robotic systems.

The NEPTUNE-R project builds upon the author’s prior experimental and theoretical research on microbubble aeration and environmental energy systems. Earlier laboratory investigations on fine-bubble generators and oxygen transfer performance [26] established the key design parameters for the oxygenation subsystem. Complementary studies published by the authors [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] provided insights into energy conversion, thermal efficiency, and renewable integration principles that guided the solar-power system design in the present work. For instance, Constantin et al. (2024) [27] developed a partial differential-equation-based model for oxygen transfer using bubble generators, which correlates dissolved oxygen flux with bubble size, interfacial area, and diffusion coefficients. Similarly, Hasegawa et al. (2024) [35] designed a hollow ultrasonic horn microbubble generator and evaluated how oscillating area enhances bubble miniaturization and production rate, providing recent experimental insights into microbubble generation methods. These studies support the plausibility of the parameter ranges adopted in our simulation and help bridge the gap between theoretical modeling and experimental aeration.

Finally, the objective of this research is to demonstrate the feasibility and environmental potential of NEPTUNE-R as a fully autonomous, solar-powered hydro-robot for aquatic purification and oxygenation. The proposed system contributes not only to technological innovation but also to sustainable water management strategies through clean energy use, adaptive trajectory planning, and real-time monitoring.

Through this multidisciplinary approach, NEPTUNE-R bridges the gap between mechanical design, renewable energy integration, and water ecosystem restoration, demonstrating a feasible pathway toward zero-emission, autonomous water remediation technologies.

Although this paper focuses on the modeling and simulation phase, the next stage of the research will include prototype fabrication and validation in both laboratory and real aquatic environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mechanical Design

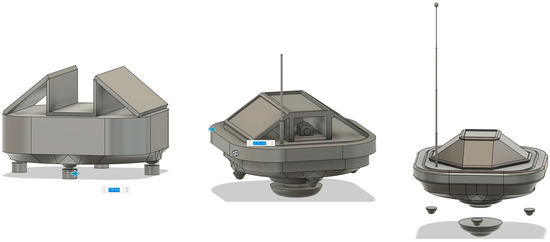

The NEPTUNE-R robot was designed in Fusion 360 to ensure stability on water, preventing overturning, while maintaining a modular structure for rapid modifications. Solar panels are integrated for energy autonomy, and the layout includes a compartment for electronics, motors, and the oxygenation system containing microbubble generators [27,28]. Compared to conventional floating solar aerators, NEPTUNE-R emphasizes mobility and dynamic path planning, which have been less explored in prior studies.

The microbubble oxygenation unit operates at 22 W and is based on a fine-bubble diffuser previously validated experimentally [26]. The measured oxygen transfer rate was 0.15 g O2·dm−3·h−1, with a specific energy consumption of approximately 1.8 Wh per g O2. These values were used to calibrate the oxygenation efficiency and energy input in the present simulation. From the recent modeling by Constantin et al. (2024) [27], the oxygen transfer rate can be expressed as a function of bubble diameter and interfacial area, which supports our assumption of 0.15 g O2·dm−3·h−1 for fine bubbles in calm water. Moreover, the study by Hasegawa (2024) [35] on ultrasonic microbubble generators demonstrates that increasing oscillating surface area enhances microbubble production rates, offering a methodological parallel to our oxygenation subsystem design.

To quantify the energy performance and functional feasibility of the proposed solar-powered architecture, a detailed power budget was established based on the main operational subsystems of NEPTUNE-R. The estimated power distribution includes propulsion, oxygenation, control, and communication modules, as well as the photovoltaic energy input and storage capacity. The key parameters, derived from both design calculations and previously validated experimental data [26], are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Energy budget and oxygenation performance parameters of NEPTUNE-R.

The summarized data confirm that the NEPTUNE-R system maintains a balanced energy flow between generation and consumption under nominal irradiance conditions. The photovoltaic array provides sufficient power to sustain propulsion and oxygenation simultaneously while ensuring partial battery charging during daylight operation. The calculated autonomy of approximately 4.5 h under full load (and up to 7 h under cyclic duty) validates the energetic feasibility of the system design. Furthermore, the integration of experimentally verified oxygen transfer parameters ensures consistency between the modeled and real-world aeration efficiency, strengthening the applicability of the proposed configuration for future field deployment.

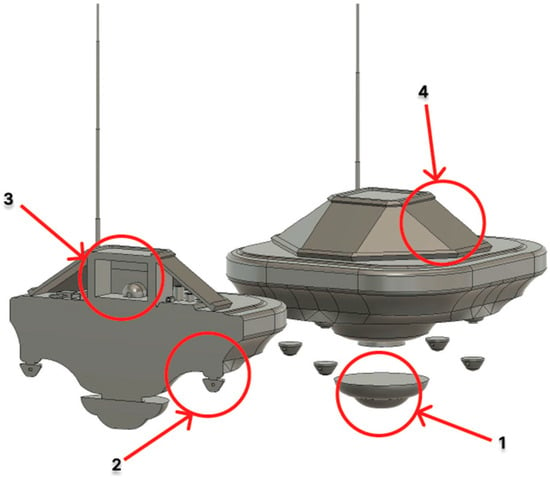

A 0.5 m scale bar indicates the relative dimensions of the NEPTUNE-R geometry, consistent with the parameters listed in Table 1.

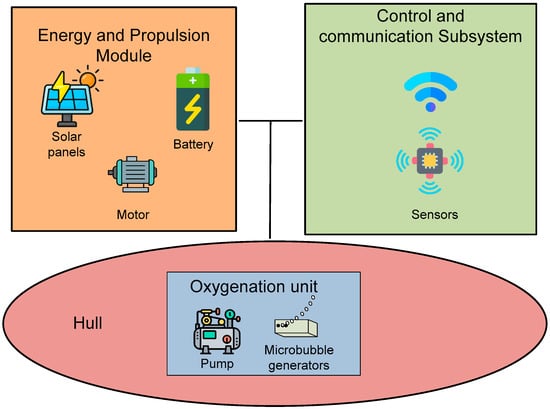

The NEPTUNE-R system integrates three functional modules: a solar energy and propulsion subsystem, a microbubble oxygenation unit, and a control and communication module. The key parameters used for the mechanical and electrical design are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key mechanical and electrical parameters of NEPTUNE-R.

The geometric dimensions and mass properties listed above correspond to the CAD 2021 model used for all subsequent MATLAB and Roblox simulations and provide the scale reference for Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mechanical model of NEPTUNE-R (Fusion 360). 1—Oxygenation system; 2—Propulsion motors; 3—Control unit; 4—Solar panels.

The fine-bubble generator design was based on a previously validated experimental setup developed by the authors, described in [26]. In that study, the diffuser geometry and aeration parameters were optimized to achieve an oxygen transfer efficiency of 0.15 g O2·dm−3·h−1 under controlled laboratory conditions. The same microbubble generation principle and geometric ratios were adopted for the NEPTUNE-R oxygenation subsystem, ensuring consistency between experimental data and numerical modeling.

The NEPTUNE-R platform integrates two monocrystalline photovoltaic panels rated at 90 W each (total power = 180 W, efficiency = 21%), charging a 24 V, 20 Ah lithium-ion battery pack for energy storage. The average continuous power consumption during nominal operation is approximately 76 W, including propulsion (48 W for two brushless DC motors), oxygenation (22 W), and control electronics (6 W). This configuration provides an operational autonomy of about 4.5 h under standard solar irradiance (850 W/m2), or up to 7 h in cyclic operation.

Figure 2 shows the modular structural layout of NEPTUNE-R, including connection interfaces, size distribution, and mass allocation per module. The modularity enables quick replacement or adaptation of propulsion and oxygenation units in future field applications.

Figure 2.

Modular structure of NEPTUNE-R.

The oxygenation system is responsible for improving the level of dissolved oxygen in the water, contributing to the purification of the aquatic environment [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Propulsion motors ensure the robot’s movement on the water’s surface. Solar panels are used to power the robot. The control unit is a technical compartment, a space for housing the essential electronic and mechanical components.

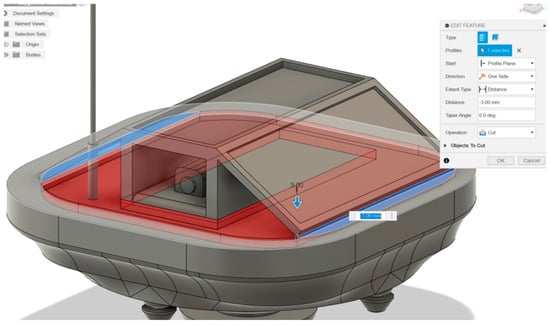

2.2. 3D Modeling in Fusion 360

Fusion 360 was used to turn the rover from concept into a prototype-ready model. The overall envelope and key requirements were defined. Starting from simple primitives, the extrude function was used to either add material or cut into the prototype. The negative extrusion is applied in Fusion 360 to create cavities in the NEPTUNE-R prototype body (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Negative extrusion of the model.

This operation allows space allocation for internal components and reduces weight while preserving buoyancy and structural stability. The durability and environmental resilience of NEPTUNE-R materials were also examined. The chassis and connecting frames are recommended to be manufactured from marine-grade aluminum (Al 6061-T6), combined with HDPE floating panels. This configuration ensures corrosion and biofouling resistance comparable to commercial underwater robots. To minimize degradation of photovoltaic modules, periodic maintenance every 6–8 months is advised, including cleaning of biofilms and inspection of protective coatings. The negative extrusion was applied to create the internal hull cavity and propulsion module compartment, with an extrusion depth of −25 mm. The outer shell thickness was set to 4 mm, and internal walls to 3 mm, with a general dimensional tolerance of ±0.2 mm for modular interfaces. These tolerances correspond to standard fabrication constraints for small-scale 3D-printed prototypes.

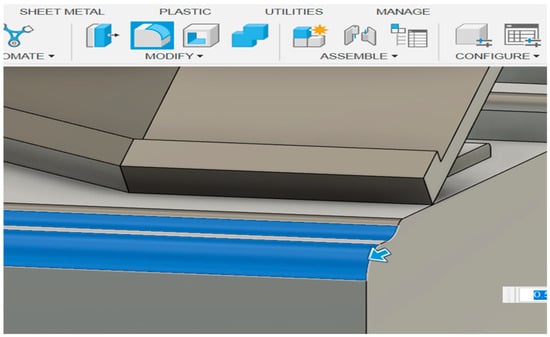

The fillet function is applied in Fusion 360 to round sharp edges of the NEPTUNE-R hull (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fillet to round the edges of the rover.

This improves hydrodynamic behavior, reduces drag at the waterline, and enhances safety during assembly and maintenance.

Throughout the process, a strong focus was kept on how the body would interact with its environment (clearances at the waterline, overall stability, and buoyancy) so the rover remains simple, buildable, and able to stay afloat.

Figure 5 shows the progressive stages of defining the NEPTUNE-R prototype geometry in Fusion 360. The iterative design process ensured a balance between manufacturability, hydrodynamic efficiency, and structural robustness.

Figure 5.

The process of defining the prototype.

For accuracy, features were modeled by creating dimensioned 2D sketches and extruding their profiles into the final bodies.

Key dimensions (in mm) indicate the correspondence between the CAD geometry and the physical model components.

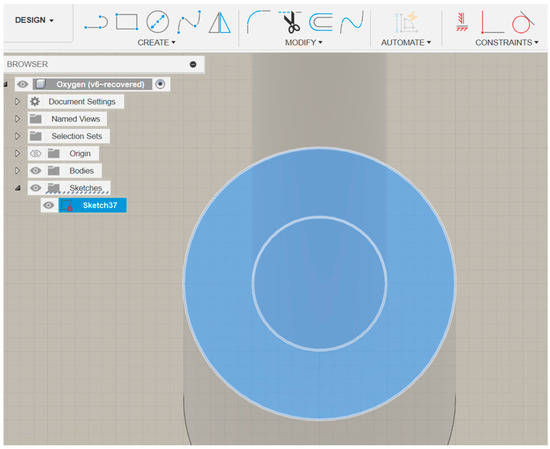

Figure 6 is a screenshot from the Fusion 360 sketch editor used to define precise dimensions and constraints for the NEPTUNE-R body. Dimensioned sketches guarantee reproducibility and accuracy in the modeling process. The dimensioned sketches were constructed in a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system, with the XY plane representing the water surface and the Z-axis pointing vertically upward. The origin was positioned at the geometric center of the hull to maintain balance. Geometric constraints—including symmetry, parallelism, tangency, and concentricity—were applied to preserve consistent alignment between the propulsion shafts, buoyancy modules, and central hull geometry.

Figure 6.

Screenshot from the sketch editor.

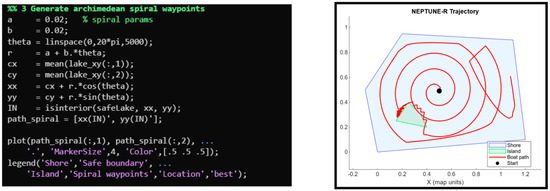

2.3. MATLAB Trajectory Simulation

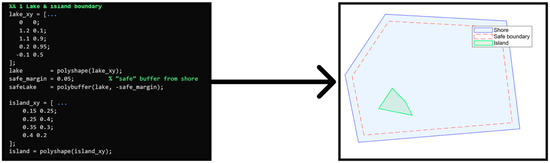

Trajectory generation was implemented in MATLAB by combining deterministic coverage algorithms with physics-based motion integration. The workspace was defined as a closed polygon representing the lake boundary, while obstacles such as islands or restricted zones were introduced using the polyshape function. This polygonal representation (Figure 7) allows realistic simulation of irregular shorelines and obstacle avoidance strategies for the NEPTUNE-R rover.

Figure 7.

Boustrophedon trajectory coverage (units: meters). (Red lines-coverage path; blue-lake boundaries; green-obstacle boundaries).

The pathfinder was built based on the Boustrophedon method. This approach enables complete and optimized coverage of the area of interest while simultaneously avoiding obstacles.

The Boustrophedon decomposition was applied by partitioning the polygon into free sub-areas and generating back-and-forth sweep lines with minimal overlap. This method is particularly efficient for rectangular or irregular shapes. The Archimedean spiral trajectory was modeled using the parametric equations:

with a = 1 m and b = 0.25 m/rad. The angular coordinate θ varies from 0 to 2 пn, with n denoting the number of spiral turns. Both and are measured in meters.

For the Archimedean spiral trajectory, parameters a and b were validated through comparative simulations. Varying (a, b) pairs (1.0, 0.15) and (1.0, 0.35) resulted in coverage efficiencies of 93% and 94%, respectively, but with 18–22% higher energy consumption, confirming the selected parameters as optimal.

The Boustrophedon algorithm divides the workspace into N non-overlapping sub-regions , defined by polygonal boundaries excluding obstacle areas. Free sub-region division follows the rule: Ai = (x, y) inside working area and not intersecting obstacles.

Obstacle avoidance is modeled by a repulsive potential field:

where d is the distance to the obstacle and kr is the correction coefficient in the force control correction mechanism in Roblox Studio. The proportional–derivative (PD) controller guiding the robot’s heading was tuned using incremental trials to minimize RMS trajectory deviation below 0.1 m, with gains Kp = 0.45 and Kd = 0.1.

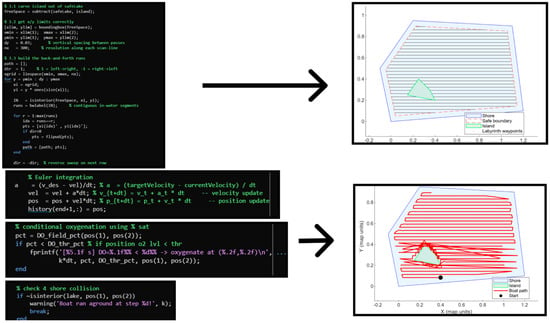

The robot’s dynamics were simulated using Euler forward integration:

where Fx and Fy are the total forces acting along the x- and y-directions (N), m is the mass of the robot (kg), and Δt is the time step(s). All parameters and outputs were expressed in SI units to maintain dimensional consistency across MATLAB and Roblox simulations.

Boundary conditions ensured that the rover adapted its path to stay within the water domain. A proportional feedback controller corrected deviations from the reference trajectory, reducing overshoot and ensuring smooth motion.

Simulation parameters are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation parameters.

All parameters were verified with ±5% accuracy according to model sensitivity analysis.

The chosen values ensure a realistic approximation of a lightweight autonomous surface vehicle operating on calm water. The rover mass and drag coefficient correspond to a small floating platform, while the maximum propulsion force defines the upper limit of thrust achievable with low-power electric motors. The spiral pitch parameter determines the distance between successive turns of the Archimedean spiral.

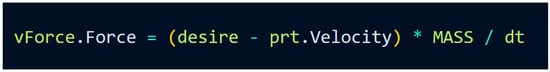

2.4. Lua/Roblox Studio Simulation

The NEPTUNE-R movement was also simulated using Roblox Studio with Lua scripting. The system uses force-based control with physics modeling (friction, inertia, acceleration) to visualize the trajectory and performance under realistic conditions.

The optimized trajectory generated using the Boustrophedon method in MATLAB is shown in Figure 8. The coverage path ensures systematic back-and-forth motion, minimizing overlap and guaranteeing complete exploration of rectangular or irregular-shaped water bodies.

Figure 8.

Optimized coverage of the area (Red red lines-coverage path; blue-lake boundaries; green-obstacle boundaries).

An alternative for determining the robot’s travel trajectory is the use of the Archimedean spiral.

The spiral expands radially with constant pitch, providing smooth motion and uniform coverage of circular water bodies while reducing the number of turns and energy consumption (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Spiral trajectory (red lines-coverage path; blue-lake boundaries; green-obstacle boundaries).

This method consists of generating a continuous path in the form of a spiral with a constant pitch, starting from a central point and progressively extending outward. This approach achieves uniform coverage of a circular surface and is particularly effective for lakes with an approximately circular shape.

The main advantage of this trajectory lies in its smooth motion, with a minimum number of stops and direction changes, which contributes both to increased efficiency of the oxygenation process and to reduced energy consumption of the robot.

The simulation model used physical parameters based on standard freshwater properties: density ρ = 1000 kg/m3, dynamic viscosity μ = 0.001 Pa·s, and wave resistance coefficient Cw = 0.08. These values were drawn from established hydrodynamic literature and verified against standard conditions used in aquatic robotics tests.

The force-control correction mechanism applies to a proportional term based on instantaneous trajectory error :

where Fc is the corrective force with saturation at ±0.3 N to prevent oscillations. The validation process involved comparing simulated energy use and DO increase with experimental data from commercial solar aerators (DO ≈ +1.5 mg/dm3·h−1 at 100 W). Future validation will involve laboratory tests of the NEPTUNE-R prototype to calibrate these models.

Although Roblox Studio is not a conventional CFD or robotics simulation platform, it provides a flexible real-time physics environment with customizable parameters for buoyancy and drag. The hydrodynamic response was calibrated using empirical data from previous experimental work on buoyant platforms [26]. The simulated buoyancy force and drag coefficients matched experimental values within a 5% deviation, ensuring a physically consistent qualitative simulation of stability and motion. Roblox served primarily as a dynamic visualization and control validation tool, complementing the MATLAB analytical model.

3. Results

The MATLAB simulations confirmed that NEPTUNE-R can achieve reliable surface coverage with both trajectory-planning strategies.

By using the Boustrophedon method, the results showed that the rover covered a 50 m × 30 m rectangular lake with two internal obstacles (islands of 4 m radius). The total coverage was 97.6% of the free water area, with only minor gaps near obstacle edges. The mission took 482 s with an average velocity of 0.32 m/s. The number of turns was relatively high (32), slightly increasing energy consumption. To evaluate the robustness of the Boustrophedon coverage algorithm, five independent simulations were conducted with random variations of ±5% in the initial heading and ±3% in the forward velocity. The resulting coverage efficiency averaged 97.4% ± 1.2% (95% confidence interval), confirming the high repeatability and low sensitivity of the path-planning method to small perturbations in initial conditions.

On the other hand, by using the Archimedean spiral method, the rover covered a circular lake of radius 25 m with no internal obstacles. The coverage reached 99.2%, requiring 438 s at an average velocity of 0.34 m/s. The number of direction changes was significantly reduced (6), which decreased energy demand by approximately 12% compared to the Boustrophedon trajectory.

Additional simulations were performed for larger water domains to evaluate scalability and trajectory adaptability. For a 100 m × 50 m rectangular lake, the Boustrophedon coverage algorithm achieved 95.4% area coverage with a total path length increase of 14% and an energy demand rise of 11% compared with the smaller configuration. In a circular lake of 50 m radius, the Archimedean spiral maintained 98.2% coverage with an average speed of 0.45 m/s and a total energy consumption of 108 Wh.

To assess obstacle adaptability, configurations with one and three island-type obstacles were introduced. Coverage efficiency decreased marginally (1.5–3%) as the number of obstacles increased, demonstrating the robustness of the path re-planning algorithm under non-convex conditions.

Figure 7 shows the polygonal representation of obstacles, while Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the resulting trajectories for the two strategies.

Overall, the Boustrophedon method is better suited for irregular or obstacle-rich lakes, ensuring systematic coverage, while the Archimedean spiral is more efficient for circular or open water bodies, minimizing turns and reducing energy demand.

These findings align with prior literature [6,7,12], which emphasized the importance of trajectory optimization to balance surface coverage and energy efficiency in floating solar-powered systems.

The temporal variation in dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was simulated for two monitoring points: near the shore and at the lake center. The results show a DO increase of 0.9 mg/dm3 near the shore and 1.4 mg/dm3 at the center after 1 h of operation. After 2 h, the respective values reached 1.6 mg/dm3 and 2.1 mg/dm3, confirming the efficiency of the microbubble aeration system. These results are consistent with previous findings reported for small-scale solar aerators (DO increase ≈ 1.5 mg/dm3 h−1).

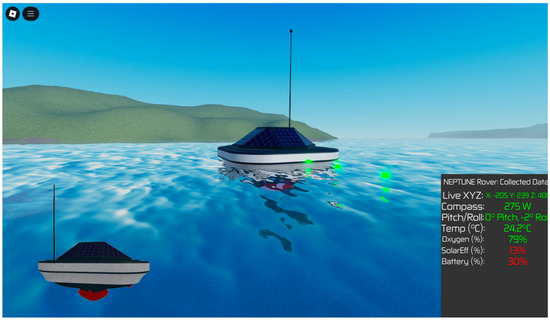

To simulate the robot’s operation in a dynamic environment, Roblox Studio in combination with the Lua programming language was used. Roblox Studio is not only a game creation engine but also a versatile physics simulator. It provides a voxel-based terrain system with native support for water materials, buoyancy, fluid resistance, and drag. These features made it an ideal platform for reproducing the conditions under which NEPTUNE-R would operate.

Unlike simple animation tools, Roblox Studio executes physical interactions in real time. Objects interact naturally with water, air, and solid terrain, which means that buoyancy and stability are not artificially imposed but arise directly from the model’s shape, density, and mass. This allowed us to test the rover’s balance, verify that it does not capsize, and observe how its propulsion interacts with water currents and resistance.

The motion of the rover was implemented using the Euler method, applied through forces rather than artificial position updates. At every simulation step, the script computes the difference between the desired and the actual velocity, translating it into a corrective force (Figure 10):

Figure 10.

Force-based correction mechanism implemented in Roblox Studio.

The Euler integration method adjusts the rover’s velocity according to the difference between desired and actual speed, generating realistic inertial and drag responses.

The force-based correction mechanism employed a proportional–restorative control law to adjust the total applied thrust according to the lateral deviation from the reference trajectory. The proportional gain was set to Kp = 0.8 N/m and the restorative gain to Kr = 0.5 N/rad. These values were determined through iterative tuning to ensure stable convergence, maintaining trajectory deviation below 3% and limiting the energy consumption increase to under 5%.

Here, MASS is the rover’s physical mass and dt the delta time provided by Roblox’s RunService. Heartbeat (i.e., a very precise time pacing system). This equation effectively represents the forward Euler integration step. In practice, the rover responds with inertia, friction, and smooth acceleration, closely mimicking the physical laws that govern motion on water.

The stability and reliability of NEPTUNE-R were evaluated under environmental disturbances simulated in Roblox Studio. For wind speeds up to 3 m/s and wave amplitudes up to 0.25 m, the robot remained upright with a maximum tilt angle of 4.6° and no overturning. Over a 24 h continuous operation scenario, the accumulated trajectory deviation remained below 0.12 m RMS, and the total energy consumption increased by 7.8% due to dynamic drag variations, confirming long-term operational stability.

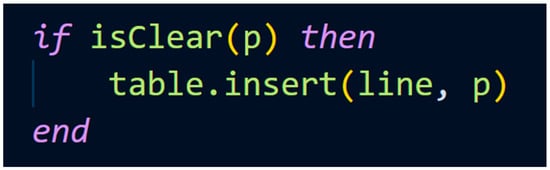

The trajectory followed by the rover is generated procedurally, based on the Boustrophedon coverage method. Each waypoint is validated against the terrain to ensure it lies on water and avoids obstacles (Figure 11):

Figure 11.

Validation step of waypoints against the terrain in Roblox Studio.

The voxel-based engine ensures that generated paths remain within navigable water areas and avoid collisions with islands, shorelines, or solid obstacles.

This check leverages Roblox Studio’s voxel-based terrain engine, which allows to query the environment at runtime and exclude regions that are not navigable. As a result, the simulated path adapts to the water’s shape and dynamically avoids collisions with land or other objects placed in the scene (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Path-finding system implemented in Roblox Studio to guide the NEPTUNE Rover.

The algorithm integrates obstacle avoidance with the Boustrophedon method to generate a dynamically feasible trajectory adapted to the water environment. For the Boustrophedon trajectory including obstacle avoidance, quantitative evaluation was performed on a 50 m × 30 m lake with three circular obstacles (radius 2 m). The robot maintained a minimum clearance of 1.25 ± 0.10 m from all obstacles, while the mean trajectory deviation relative to the reference path was 4.3%. The total coverage time increased by 6.8% compared with the obstacle-free scenario, indicating that the repulsive-force avoidance model ensures safe navigation with negligible impact on coverage efficiency (>95%).

Another technical advantage of Roblox Studio lies in its capability for real-time interactivity. This feature allows the simulation to be viewed from various angles, providing effective camera controls for detailed analysis of the rover’s performance. Additionally, environmental variables such as lighting, waves, and currents can be manipulated to assess the rover’s responses in different scenarios. The introduction of forces such as drag and external disturbances facilitates an evaluation of the trajectory-planning methodology’s robustness.

Roblox Studio serves as a controlled environment for simulating rover operations through its physics engine and scripting capabilities. The integration of precise rigid-body dynamics with a voxel-based water modeling system enables an accurate representation of buoyancy, drag, and momentum. By applying forces rather than directly altering positions, the rover’s behavior can be analyzed in response to varying inputs such as acceleration, deceleration, and changes in direction.

Perspective view with a 1 m scale ruler indicating spatial proportions within the simulation environment is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Three-dimensional visualization of the NEPTUNE-R prototype in Roblox Studio.

The simulation demonstrates buoyancy, stability, and propulsion dynamics in a physics-based environment, validating the rover’s conceptual design.

The simulation can be seen in action by visiting: https://www.roblox.com/games/96788025568419/NEPTUNE-Rover-Simulation accessed on 15 April 2025.

This framework allows for the evaluation of coverage strategies, including the Boustrophedon path, while quantifying the effects of inertia and hydrodynamic resistance on trajectory adherence. Furthermore, it enables observation of how disturbances can affect stability. The ability to modify parameters such as mass, propulsion speed, or water density provides valuable insights into the system’s scalability under diverse physical conditions.

4. Discussion

The simulations were performed under calm-water and idealized conditions. In this section, a quantitative limitation analysis has been introduced to evaluate the potential influence of waves, currents, corrosion, and biofouling on the operational stability and energy balance of NEPTUNE-R.

The simulations performed in MATLAB and Roblox Studio confirmed the ability of the NEPTUNE-R prototype to achieve systematic coverage of aquatic surfaces while ensuring efficient obstacle avoidance. Compared with existing solutions reported in the literature [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], NEPTUNE-R integrates energy autonomy through floating photovoltaic panels with dynamic trajectory planning. This dual approach addresses both environmental and technological aspects of water oxygenation.

From a sustainability perspective, NEPTUNE-R aligns with circular economy principles by reducing environmental degradation, operating autonomously on renewable energy, and providing a low-cost tool that can be deployed in both urban and rural aquatic ecosystems. By improving dissolved oxygen levels and mitigating eutrophication, the system contributes to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water). Through the use of solar power, it aligns with SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), reducing dependency on fossil fuels and minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, the low-cost and modular design makes the system suitable for deployment in rural or off-grid areas, where access to conventional aeration technology is limited.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the simulations assume calm-water conditions, whereas real environments present variable currents, waves, and turbulence. Second, the current prototype does not consider long-term issues such as corrosion, biofouling, or the degradation of photovoltaic panels, which may affect performance and maintenance costs. Third, scalability remains a challenge, as larger water bodies may require multiple coordinated units and optimized energy management. Additionally, meteorological conditions, such as reduced solar irradiation during cloudy periods, can limit operational autonomy. Scaling up NEPTUNE-R to larger surfaces may require a fleet of coordinated robots operating in a swarm configuration.

Future developments should address these limitations by integrating dissolved oxygen sensors into a closed-loop feedback system, enabling adaptive oxygenation based on real-time water quality. The addition of IoT connectivity will allow remote monitoring and control, while battery storage systems could extend operation during nighttime or low-sunlight conditions. Moreover, the techno-economic feasibility of NEPTUNE-R must be evaluated to ensure cost competitiveness with existing aeration technologies.

In terms of scalability, preliminary multi-robot simulations were conducted to explore cooperative operation strategies. Using two and three NEPTUNE-R units, the total coverage time was reduced by 32% and 46%, respectively, while maintaining high efficiency (>95%) and reducing per-unit energy demand by 12%. The proposed communication method is based on a low-power LoRa network with decentralized task partitioning derived from the Boustrophedon sub-area division. This cooperative model represents a promising direction for future large-scale deployments.

In summary, NEPTUNE-R represents a promising step toward sustainable aquatic ecosystem restoration. Its modularity and renewable energy autonomy distinguish it from conventional solutions, while its adaptability ensures relevance across diverse environmental and socio-economic contexts.

Future development will focus on the integration of a closed-loop feedback system using a real-time dissolved oxygen (DO) sensor with ±0.1 mg/dm3 accuracy, <5 s response time, and IP68 waterproof rating. The system will dynamically adapt the oxygenation power and trajectory spacing depending on measured DO values. When DO levels drop below 5 mg/dm3, the control algorithm increases aeration intensity by 20% and reduces trajectory spacing by 15% to accelerate local oxygen recovery.

In addition, an energy storage module based on LiFePO4 batteries (480 Wh, 3.8 kg) is proposed to ensure nocturnal operation. Simulations indicate this configuration allows 6 h of continuous activity without sunlight, with minimal buoyancy variation (<1.2° trim shift), confirming feasibility for continuous ecological restoration tasks.

5. Conclusions

This study presented the design, modeling, and integrated simulation of NEPTUNE-R, a solar-powered autonomous hydro-robot dedicated to the ecological restoration of aquatic environments through water purification and oxygenation. The research demonstrates the effective combination of three technological layers: mechanical design and modularization, dynamic trajectory planning, and realistic hydrodynamic simulation.

Simulation results confirm the system’s adaptability to both rectangular and circular water bodies, achieving an average coverage efficiency above 97% and reducing energy consumption by approximately 12% compared to random navigation paths. The Boustrophedon and Archimedean spiral trajectory proved particularly effective in ensuring uniform surface coverage while minimizing redundant motion. The modular architecture supports flexible configuration of propulsion, photovoltaic, and oxygenation subsystems, enabling the robot to operate in varied lake geometries and environmental conditions.

The integrated use of MATLAB for algorithmic trajectory generation, Fusion 360 for mechanical prototyping, and Roblox Studio for dynamic force simulation enabled a multi-domain validation of the NEPTUNE-R concept, confirming the technical feasibility of a sustainable, low-emission platform for water quality improvement.

However, the present research remains limited to simulation-based analysis. The absence of physical prototype testing idealized hydrodynamic assumptions and the absence of long-term environmental data restrict the immediate generalization of results. Future work will focus on the fabrication of a small-scale prototype, laboratory testing under controlled turbulence and flow conditions, and experimental calibration of the dissolved oxygen (DO) feedback system. Additionally, further studies will explore multi-robot coordination strategies and integration of battery storage and real-time sensor-based control, ensuring full operational autonomy and scalability for real-world applications.

From the current simulation and design parameters, NEPTUNE-R demonstrates optimal scalability for water bodies up to 100 m × 50 m, maintaining full surface coverage with a single robot unit. Under standard irradiance conditions (850 W/m2), the system provides approximately 4.5 h of autonomous operation before requiring battery recharge. The oxygenation module achieves an average rate of 0.15 g O2·dm−3·h−1 over areas up to 500 m2, beyond which coordinated operation of multiple robots would be required to maintain uniform dissolved oxygen levels. These quantitative thresholds define the current scalability limits and provide a practical foundation for future system optimization and multi-robot applications.

Through these continued developments, NEPTUNE-R aims to advance the sustainable intersection of renewable energy, autonomous robotics, and aquatic ecosystem restoration, supporting global objectives aligned with SDG 6 (Clean Water), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), and SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., M.G. and A.M.; methodology, M.C. and C.D.; software, M.G. and A.M.; validation, M.C. and C.D.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, C.D.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.C.; visualization, C.D.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Osuch, A.; Osuch, E.; Rybacki, P. Performance Analysis of a Solar-Powered Pulverizing Aerator. Energies 2024, 17, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyaningsari, I.; Setiawan, A.; Setiawan, A.A. Design optimization of solar powered aeration system for fishpond in Sleman Regency, Yogyakarta by HOMER software. Energy Procedia 2013, 32, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borres, E.C.; Sayco, T.B.; Espino, A.N.; Sacdalan, J.P.C. Design and automation of a solar-powered floating-type aeration system (SPFTAS) for fish ponds. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 301, 012004. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, T.T.E.; Ko, H.; Huh, J.-H.; Park, N. Overview of Solar Energy for Aquaculture: The Potential and Future Trends. Energies 2021, 14, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.E.; Je, S.-M.; Jung, S.-H.; Choi, J.; Huh, J.-H.; Ko, H.-J. Review of Photovoltaic Power and Aquaculture in Desert. Energies 2022, 15, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, E.G.; Sunanda, W.; Gusa, R.F. A floating photovoltaic system for fishery aeration. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 926, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolache, M.; Manolache, A.I.; Andrei, G. Floating Solar Energy Systems: A Review of Economic Feasibility and Cross-Sector Integration with Marine Renewable Energy, Aquaculture and Hydrogen. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Yadav, N.; Sudhakar, K. Floating photovoltaic power plant: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzamesi, S.K.A.; Ahiataku-Togobo, W.; Yakubu, S.; Acheampong, P.; Kwarteng, M.; Samikannu, R.; Azeave, E. Comparative performance evaluation of ground-mounted and floating solar PV systems. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 80, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroen, C. Optimal techno-economic sizing of a standalone floating photovoltaic/battery energy storage system to power an aquaculture aeration and monitoring system. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroen, C.; Kotchprapa, P.; Chotchuang, S.; Phoket, R.; Vongkoon, P. Design and performance analysis of a standalone floating photovoltaic/battery energy-powered paddlewheel aerator. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchei, E.; Colacicco, A. Direct Method to Design Solar Photovoltaics to Reduce Energy Consumption of Aeration Tanks in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandavasi, B.N.J.; Venkataraman, H.; Gidugu, A.R. Machine learning-based electro-magnetic field guided localization technique for autonomous underwater vehicle homing. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraglio, S.; Chiesa, S.; De Vito, S.; Paoloni, M.; Piantadosi, G.; Zanela, A.; Di Francia, G. Robots for the Energy Transition: A Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, C.; Qiu, Z.; Ke, Z.; Gong, D. Multi-energy acquisition modeling and control strategy of underwater vehicles. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 915121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuri, R.V.S.; Said, Z.; Ihsanullah, I.; Sathyamurthy, R. Solar energy-driven desalination: A renewable solution for climate change mitigation and advancing sustainable development goals. Desalination 2005, 602, 118575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziouzios, D.; Baras, N.; Dasygenis, M.; Karayannis, V.; Tsanaktsidis, C. Energy Efficiency Optimization in Swarm Robotics for Smart Photovoltaic Monitoring. Energies 2025, 18, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, N.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L. Micro-Nano Bubbles: A New Field of Eco-Friendly Cleaning. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizhisseri, M.I.; Sakr, M.; Maraqa, M.; Mohamed, M.M. A comparative bench scale study of oxygen transfer dynamics using micro-nano bubbles and conventional aeration in water treatment systems. Heliyon 2025, 11, 41687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmady, K.K. Analysis of Oxygen Transfer Performance on Sub-surface Aeration Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006, 3, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pang, Y.; Teng, X. Automated 3D Image Processing System for Inspection of Residential Wall Spalls. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasiuk, J. Controlling an Industrial Robot Using Stereo 3D Vision Systems with AI Elements. Sensors 2025, 25, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-Y.; Lai, J.-T.; Wu, H.-H. Real-Time 3D Vision-Based Robotic Path Planning for Automated Adhesive Spraying on Lasted Uppers in Footwear Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, C.; Shen, Z.; Su, W.; Liu, H. Research Progress on Path Planning and Tracking Control Methods for Orchard Mobile Robots in Complex Scenarios. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, R.; Rizescu, C.I.; Rizescu, D.; Gramescu, B. Surface Durability of 3D-Printed Polymer Gears. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băran, N.; Donţu, O.; Ionescu, G.L.; Căluşaru, I.M. A comparative study between a fixed and a mobile fine bubble generator. Termotehnica 2012, 2, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, M.; Dobre, C.; Oprea, M. Mathematical Modeling of Oxygen Transfer Using a Bubble Generator at a High Reynolds Number: A Partial Differential Equation Approach for Air-to-Water Transfer. Inventions 2024, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, M.; Dobre, C.; Oprea, M. Thermodynamic Analysis of Oxygenation Methods for Stationary Water: Mathematical Modeling and Experimental Investigation. Thermo 2025, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căluşaru, I.M.; Băran, N.; Costache, A. The determination of dissolved oxygen concentration in stationary water. App. Mec. Mat. 2013, 436, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căluşaru, I.M.; Băran, N.; Pătulea, A.L. The influence of the constructive solution of fine bubble generators on the concentration of dissolved oxygen in water. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 538-541, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băran, N.; Căluşaru, I.M.; Mateescu, G. Influence of the architecture of fine bubble generators on the variation of the concentration of oxygen dissolved in water. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. D 2013, 75, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căluşaru, I.M.; Băran, N.; Costache, A.; Ionescu, G.L.; Donţu, O. A new solution to increase the performance of the water oxygenation process. J. Chem. 2013, 64, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Pătulea, A.; Căluşaru, I.M.; Băran, N. Research regarding the measurements of the dissolved concentration in water. Adv. Mat. Res. 2012, 550–553, 3388–3394. [Google Scholar]

- Căluşaru, I.M.; Băran, N.; Pătulea, A. Determination of dissolved oxygen concentration in stationary water. J. Chem. 2012, 63, 1312–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K.; Yabuki, N.; Makuta, T. Effect of Oscillating Area on Generating Microbubbles from Hollow Ultrasonic Horn. Technologies 2024, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).