Abstract

Heritage cities confront persistent tensions between safeguarding cultural authenticity and facilitating sustainable heritage tourism within rapidly modernizing urban contexts. This study examines these dynamics through Pingyao Ancient City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site exemplifying both conservation achievements and tourism challenges. Employing a mixed-methods framework, the research synthesizes GIS-based spatial analysis, multi-scalar policy assessment, media discourse analysis, and stakeholder interviews with residents, tourists, and heritage managers. Findings reveal substantial land use transformations characterized by internal functional restructuring with 212% and 300% expansion of service and commercial land use, respectively. While regulatory frameworks demonstrate efficacy in preserving architectural integrity, they simultaneously constrain adaptive reuse and experiential engagement. Media narratives and interviews illuminate pervasive authenticity concerns (86% among stakeholders) despite acknowledged infrastructural improvements. The analysis validates that static preservation paradigms, while achieving technical objectives, potentially undermine destination competitiveness by privileging physical conservation over cultural vitality and holistic visitor experiences. This study posits that sustainable heritage tourism necessitates integrated policy frameworks reconciling conservation imperatives with adaptive spatial strategies, dynamic community engagement, and authentic cultural interpretation. These findings contribute to heritage management theory while offering practical implications for policy formulation in comparable contexts.

1. Introduction

Heritage cities worldwide face mounting challenges in maintaining tourism development while preserving cultural authenticity, particularly in rapidly developing economies where market forces create substantial pressures on historical urban environments [1]. The fundamental paradox of heritage tourism development lies in its inherent contradiction: while successful preservation maintains cultural authenticity that attracts visitors, strict conservation approaches may limit development flexibility necessary for contemporary tourism functionality [2]. Conversely, excessive development aimed at enhancing tourism competitiveness may erode the very authenticity that constitutes the primary attraction [3]. Understanding this complex dynamic requires comprehensive analysis of how land use of spatial transformation, policy interventions, and stakeholder experiences interact to influence heritage destination competitiveness outcomes. Recent scholarship has increasingly recognized that heritage tourism success depends not merely on preservation quality but on achieving sophisticated integration between conservation and contemporary service delivery [4]. Research indicates that heritage destinations can benefit from balancing cultural authenticity with modern amenities, such as shade structures in hot climates, cell phone access for site-specific apps, and toilet facilities for those with disabilities, to align with contemporary tourist expectations [5,6].This requires innovative approaches to land use, service development, and community engagement that support rather than undermine cultural preservation objectives while enhancing destination attractiveness.

China’s heritage tourism sector exemplifies these challenges with particular clarity. Chinese cities of World Heritage experience dramatically varied trajectories of success and decline that reflect different approaches to balancing conservation imperatives with development pressures [7]. The rapid pace of China’s economic development creates intense market pressures on heritage destinations to modernize quickly while simultaneously maintaining cultural authenticity for tourism markets increasingly sophisticated in their authenticity expectations [8]. This creates acute tensions between preservation and development that require careful management to achieve sustainable tourism competitiveness. Research indicates that while China’s cultural tourism sector experienced remarkable growth, with domestic cultural tourism visits reaching 3.2 billion in 2019 before the pandemic disruption [9], heritage destinations demonstrate considerable variation in performance outcomes. Comparative analysis of Chinese heritage destinations reveals significant performance variations despite similar heritage assets and policy support levels. Cities like Lijiang and Zhouzhuang have achieved remarkable tourism growth through comprehensive modernization strategies that successfully integrate heritage preservation with contemporary service delivery systems [10]. These destinations prove that careful land transformation, strategic infrastructure development, and sophisticated service integration can enhance tourism attractiveness while maintaining cultural authenticity.

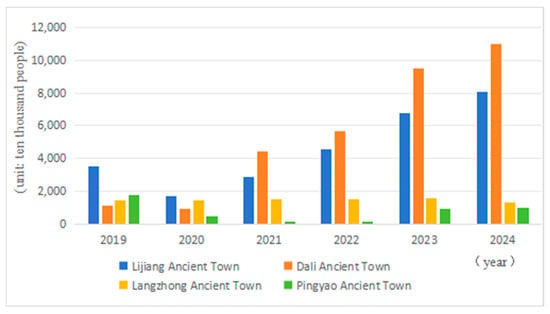

However, other heritage cities, including Pingyao, have experienced relative stagnation despite possessing exceptional heritage assets and receiving substantial government investment support [11]. Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1997, Pingyao Ancient City, an exceptionally well-preserved Ming and Qing dynasty urban settlement, has become a paradigmatic case for examining the relationship between heritage conservation investment and tourism development [12]. The city possesses exceptional heritage assets, including the most complete preserved ancient city walls in China, over 3800 traditional buildings, and rich cultural traditions dating back 600 years, yet fails to translate these advantages into sustained tourism competitiveness [13]. Despite substantial government investment in conservation and tourism infrastructure development as mandated by China’s newly revised Cultural Relics Protection Law (2024), which requires all levels of government to incorporate cultural heritage protection into economic and social development planning and ensure adequate budgetary allocation for heritage preservation [14], Pingyao faces significant competitive challenges within China’s heritage tourism landscape. Compared with that of its counterpart heritage cities in China, such as Lijiang, Dali, and Langzhong, the tourism appeal and influence of Pingyao have experienced a notable decline over the past five years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tourist numbers in the four ancient cities from 2019 to 2024.

The potential decline in Pingyao’s tourism attractiveness may be attributed to a complex interplay of structural and experiential factors that impede the destination’s capacity to maintain competitive parity with comparable heritage cities. Primarily, the tension between commercial development and authenticity perception represents a fundamental challenge, whereby intensive tourism-oriented commercialization potentially undermines visitors’ perceptions of genuine cultural experiences—a phenomenon wherein commercial activities and standardized tourist services may progressively overshadow the organic cultural characteristics that constitute living heritage environments. Concurrently, conservation-focused management approaches that prioritize physical preservation may inadvertently limit the destination’s capacity to accommodate evolving visitor expectations and contemporary tourism functionalities, potentially resulting in environments that emphasize static architectural preservation over dynamic cultural engagement and meaningful visitor experiences. Furthermore, tourism-induced demographic and socioeconomic changes, including shifts in residential patterns and community composition, may progressively affect the intangible cultural dimensions that animate heritage spaces, as alterations in local community structure potentially influence the authentic cultural practices and social interactions that traditionally characterized the destination. Furthermore, notwithstanding the significant infrastructure investment stipulated by heritage protection legislation, there may be potential deficiencies in experiential design. This includes interpretive services, visitor orientation systems, and the integration of modern amenities with heritage environments, which could limit the destination’s capacity to offer captivating tourism experiences that are in line with contemporary visitors’ preferences for immersive and meaningful cultural interactions. These diverse factors jointly indicate that Pingyao’s competitive challenges compared to destinations like Lijiang and Dali might originate from systematic difficulties in reconciling conservation requirements with adaptive tourism development strategies that effectively integrate authenticity, accessibility, and visitor satisfaction.

Current research on heritage tourism competitiveness emphasizes the importance of integrated approaches that coordinate policy-guided preservation with experiential service delivery, spatial accessibility with cultural authenticity, and community welfare with economic development [15]. However, most existing studies focus on successful destinations or employ single-method approaches that may miss the complex interactions between spatial, policy, and stakeholder factors that influence tourism outcomes [16]. This research addresses three critical dimensions of Pingyao’s tourism challenges through integrated multiple analytical approaches. First, how have land use changes within the ancient city core and surrounding peripheral areas influenced tourism functionality and destination attractiveness? Spatial transformation analysis can reveal how preservation and development patterns affect accessibility, service availability, and visitor experience quality that determine competitiveness outcomes [17]. Secondly, how do policies contribute to the current situation of the protection of Pingyao Ancient City? Policy analysis frameworks applied to relevant documents are crucial for comprehending the challenges in tourism development, especially considering the intricate characteristics of contemporary tourism governance and the pressures from the competitive market. Third, what do media, managers, resident and tourist perspectives reveal about factors contributing to Pingyao’s competitive decline relative to other heritage destinations? Stakeholders’ discourse can identify experiential factors that quantitative metrics may not capture but significantly influence destination success.

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

Authenticity has long been a foundational yet contested concept in heritage and tourism research. Recent scholarship highlights that authenticity in tourism is both theoretically fluid and contextually constructed rather than a fixed attribute of heritage objects [18]. Early theorization of staged authenticity remains influential, but contemporary perspectives increasingly view authenticity as an evolving relationship between heritage sites, local communities, and visitors [19]. Building on this view, scholars have identified three interrelated dimensions—objective authenticity (material genuineness), constructive authenticity (socially negotiated meaning), and existential authenticity (personal experiential feeling)—which together emphasize authenticity as a relational and performative process shaped by material integrity, cultural context, and visitor perception [18].

Recent research further argues that policies emphasizing only material conservation, such as facade restoration and architectural replication, may neglect the lived and experiential aspects of authenticity that sustain meaningful engagement. Overemphasis on physical restoration can preserve external form while diminishing the social and cultural vitality of heritage spaces. Conversely, excessive commercialization can erode perceived authenticity by replacing local practices with standardized tourist experiences [20]. Therefore, maintaining authenticity requires a balanced approach that integrates tangible conservation, living cultural practices, and innovative visitor experience design.

As the theoretical understanding of authenticity has evolved toward recognizing its relational and dynamic nature, methodological approaches in heritage tourism research have concurrently expanded to address the complexity of heritage phenomena. Subsequent studies have employed diverse analytical frameworks, including mixed methods designs, spatial analysis techniques, and qualitative interpretive approaches, to examine how heritage conservation, tourism development, and community participation interact within changing socio-cultural and spatial contexts.

2.1. Mixed-Methods Approaches in Heritage Tourism Research

Heritage tourism research has been characterized by increasing methodological complexity as scholars have recognized the multidimensional nature of heritage tourism phenomena [12]. Gregory and John document how heritage tourism operates through interconnected physical, social, and institutional dimensions that require different analytical approaches to understand broadly [21]. Bob and Hilary observe that single-method studies often fail to capture the full scope of heritage tourism impacts and processes [22]. Moeller et al. identify mixed-methods research as particularly suited to complex social phenomena where quantitative measurement and qualitative interpretation serve complementary analytical functions [23]. Their methodological framework has been applied in tourism contexts by researchers seeking to combine objective measurement with stakeholder perspectives [24]. Russell and Faulkner note that heritage tourism destinations exhibit characteristics of complex adaptive systems, suggesting the need for analytical approaches capable of addressing multiple variables and their interactions [25].

2.2. Spatial Analysis in Tourism Research

Technological advances have enabled systematic quantification of spatial changes in tourism destinations. Butler establishes land use patterns as fundamental indicators of tourism destination development, with different lifecycle stages exhibiting distinct spatial characteristics [26]. His tourism area lifecycle model has been widely applied in heritage tourism contexts to understand development trajectories and assess management effectiveness. Stefan demonstrates how land use change analysis provides quantifiable evidence of tourism development pressures and their spatial distribution [27]. G. Wall and A. Mathieson document the application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies in tourism research, showing how these tools enable systematic measurement of spatial change over time [28]. John provides technical validation for remote sensing methodologies, demonstrating their capacity to generate consistent, reproducible data across different temporal and spatial scales [29]. Eric and Helmut establish temporal land use analysis as a standard approach for identifying development phases and assessing policy impacts [30].

The evolution from basic land use mapping to sophisticated landscape pattern analysis has further enhanced analytical capabilities. Kevin, Samuel and Eduard develop standardized methodologies for calculating landscape metrics that quantify spatial patterns and changes in land cover configuration. Their FRAGSTATS software has been widely adopted in environmental and planning research for measuring patch density, connectivity, and fragmentation [31]. Huabin and Jianguo evaluate the application of these metrics in different research contexts, identifying their strengths and limitations for various analytical purposes [32].

The quantitative approaches also have been enriched through the integration of landscape ecology principles, providing deeper understanding of human-environment interactions in tourism contexts. Richard documents the application of landscape ecology principles to human-modified environments, including tourism destinations [33]. Monica provides theoretical foundations for using landscape metrics to assess environmental impacts and spatial integrity in developed landscapes [34]. Their work establishes methodological frameworks that have been adopted in subsequent heritage tourism research.

2.3. Qualitative Methods in Heritage Tourism Research

The qualitative research framework has been extensively applied in tourism research to address the limitations inherent in single-method approaches. Denzin establishes triangulation as a fundamental principle for enhancing research validity through multiple data sources, methods, and theoretical perspectives [35]. Alain specifically validates triangulation methods in tourism research contexts, demonstrating their effectiveness for understanding complex tourism phenomena [36]. Frank and Gerald establish policy analysis as a standard approach for understanding institutional frameworks and decision-making processes [37]. Paul and Hank develop the advocacy coalition framework for understanding policy change processes and stakeholder influences on policy outcomes [38]. Fairclough provides methodological foundations for critical discourse analysis of policy texts, demonstrating how linguistic analysis can reveal underlying assumptions and power relations [39]. His approach has been applied in tourism policy research to understand how policy discourse shapes development approaches and stakeholder relationships [40].

Qualitative media interpretation and interviews have been widely adopted in tourism research for accessing stakeholder perspectives and experiential knowledge. Maxwell and Lei document agenda-setting theory and its applications in media analysis, showing how media coverage influences public attention and policy priorities [41]. Entman develops framing analysis techniques for understanding how media presentations shape public perception of issues and events. Kvale and Brinkmann provide comprehensive methodological guidance for conducting interviews, including techniques for question design, interview conduct, and data analysis [42]. John demonstrates the application of resident interviews in tourism impact research, showing how qualitative methods can reveal community perceptions and responses to tourism development. His social exchange theory framework has been extensively cited in subsequent tourism research examining resident attitudes toward tourism development [43]. Shaw and Williams document the use of business interviews in tourism research, showing how tourism operators provide insights into market dynamics, operational challenges, and business strategies [44]. Timothy examines the application of government official interviews for understanding institutional perspectives and policy implementation challenges [45].

2.4. Existing Analytical Approaches to Pingyao’s Heritage Tourism

Research on Pingyao Ancient City has employed diverse methodological approaches, ranging from quantitative spatial analysis to qualitative assessment frameworks. Spatial analysis studies have examined the physical evolution of urban structures, focusing on buildings, street networks, and land use patterns to understand how spatial arrangements have developed over time while maintaining cultural characteristics [46]. Parallel to this, sustainability assessment research has utilized expert consultation methodologies, particularly the Delphi technique involving cultural heritage tourism specialists, to evaluate heritage tourism indicators through consensus-building processes that assess “importance”, “comprehensibility”, and “suitability” across multiple survey rounds [47]. More recent studies have begun to integrate multiple analytical dimensions within single research frameworks. Zhang, Xiao, and Liu applied the Tripartite Model of Attitudes to examine tourist behavior patterns in Pingyao Ancient City, combining cognitive analysis through Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI) for semantic examination and sentiment analysis using SNowNLP for Chinese text processing from travel platforms (Ctrip, Mafengwo, and Meituan). GIS in their study is applied to analyze photographic tourists’ extensive exploration in visually appealing areas, contrasting with the more centralized movements of general tourists, reflecting their varied heritage interests [48].

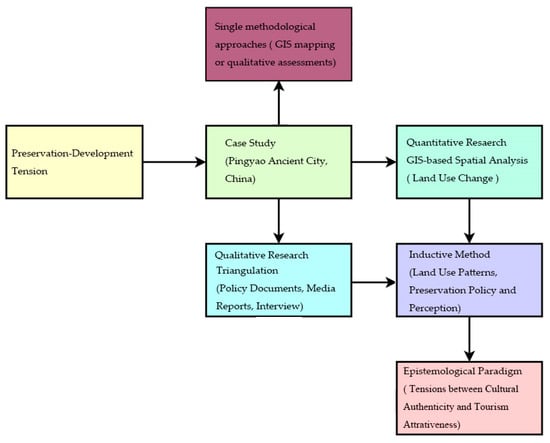

In contrast to previous studies that typically employ single methodological approaches such as GIS mapping or qualitative assessments, this research adopts a mixed-methods framework to examine the relationships between heritage preservation policies, spatial transformation patterns, and tourism performance in Pingyao Ancient City. The methodology combines quantitative GIS-based spatial analysis to document land use changes and morphological transformations within and around the heritage site with qualitative analysis conducted through triangulation of three data sources: policy document review of heritage protection regulations and tourism development measures, semi-structured interviews with tourists, heritage managers, and residents, and systematically collected media coverage and public discourse (Figure 2). This methodological approach examines factors influencing tourism dynamics in heritage destinations, including commercialization processes, authenticity considerations, and visitor experience variables.

Figure 2.

The research framework and methods (Source: drawn by Qiang Wang).

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

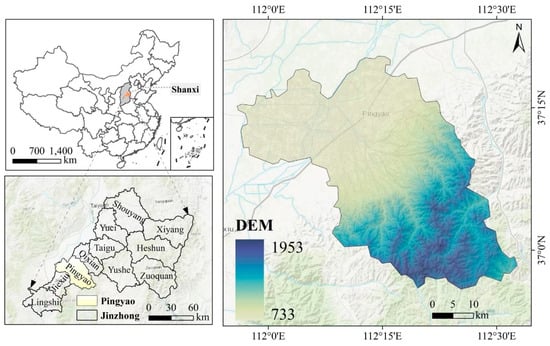

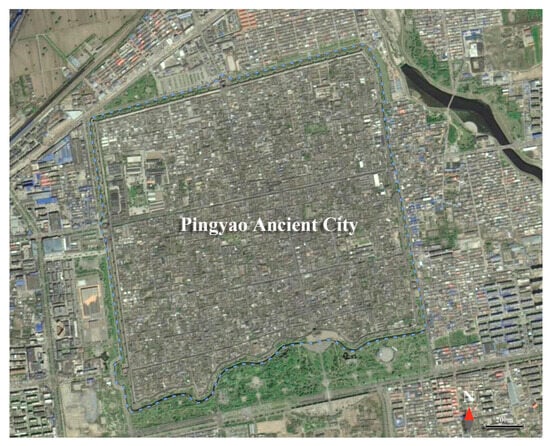

Pingyao Ancient City, located in Shanxi Province, China (37°11′ N, 112°10′ E) (Figure 3), serves as an exemplary case study for heritage city transformation analysis due to its exceptional historical significance, well-preserved urban morphology, and complex contemporary development pressures. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, Pingyao represents one of the best-preserved examples of traditional Han Chinese city planning and architecture, encompassing approximately 2.25 square kilometers within its intact Ming Dynasty city walls [49] (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Location Map of Pingyao County, DEM = Digital Elevation Model, Elevation 733–1953 (m) (Source: drawn by Qiang Wang).

Figure 4.

The Boundary of Pingyao Ancient City (Source: reproduced by Qiang Wang from Baidu Map).

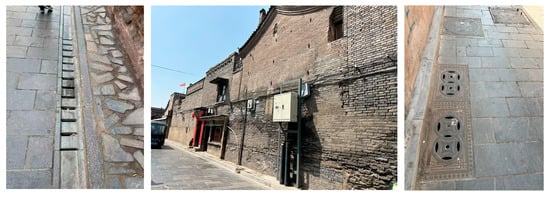

The ancient city is situated in the Taiyuan Basin at an elevation of approximately 750 m above sea level, characterized by semi-arid continental climate conditions with distinct seasonal variations. The urban layout follows traditional Chinese urban planning principles—commonly adopted from the Zhou through Ming dynasties (ca. 1046 BCE–1644 CE)—featuring a central administrative axis, grid-patterned residential quarters (hutongs), and defensive walls with six gates and 72 watchtowers [13]. The broader study area encompasses both the core heritage zone within the ancient walls and a 5 km buffer zone to capture spillover development effects and comparative analysis opportunities. With the current city wall configuration dating to the 14th century Ming Dynasty period, the city served as a major financial center during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), hosting China’s first banks and developing sophisticated commercial networks that extended across the empire [50]. This historical legacy is preserved through approximately 4000 traditional courtyard houses, 20 major temples, and numerous commercial buildings that maintain original architectural characteristics and spatial relationships. The broader study area encompasses both the core heritage zone within the ancient walls and a 5 km buffer zone to capture spillover development effects and comparative analysis opportunities.

The physical fabric and spatial morphology of Pingyao Ancient City establish essential baseline conditions for assessing visual integrity and tourism impacts. Traditional dwellings and commercial buildings predominantly employ brick-and-timber construction, with load-bearing brick walls (approximately 0.37–0.5 m thick) supporting gray-tiled gable roofs typical of late Ming–Qing vernacular architecture [51]. Building heights are generally restricted to one or two stories (approximately 4.5–9 m), producing a low-rise urban profile that defines the historical streetscape. The primary streets, including Ming-Qing Street and South Street, range between 6 and 8 m in width, while residential alleys (hutongs) narrow to 2–4 m, creating intimate pedestrian scales conducive to slow movement and social interaction [52]. Beyond the 6 km city wall (averaging 10–12 m in height), agricultural lands once functioned as a visual buffer, characterized by open fields, tree belts, and irrigation patterns that framed the walled city within its agrarian context [51]. In recent years, however, modern developments within 1–1.5 km of the city perimeter have altered this visual transition, with residential towers exceeding 20–30 stories introducing vertical contrasts that visually compete with the heritage skyline [53].

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. GIS and Remote Sensing Data

The methodological framework for land use analysis of Pingyao County integrates multi-source geospatial data with advanced remote sensing techniques to capture both regional-scale transformations and localized heritage landscape dynamics. For comprehensive land use mapping of Pingyao County beyond the ancient city boundaries, this study utilized Landsat 5 OLI/TIRS imagery with 30 m spatial resolution to enable multitemporal land use classification and change detection analysis across five observation periods (1985, 1997, 2010, 2020, 2024). These temporal intervals span China’s reform and opening-up period and encompass significant phases in Pingyao Ancient City’s development, including the period following its UNESCO World Heritage designation in 1997 and subsequent tourism-driven economic growth. Image selection protocols prioritized scenes with cloud coverage below 10% and maintained seasonal consistency during April-May periods to minimize atmospheric interference and phenological variations that could compromise land cover classification accuracy. The dual-scale spatial analysis framework was implemented through ArcGIS 10.8 to address different analytical scales for areas within and outside the ancient city walls. Complementing the regional satellite analysis, the data sources for Pingyao Ancient City encompass four primary datasets: POI data were systematically retrieved from open-source APIs including Baidu Maps and Gaode Maps through web scraping techniques in June 2024, comprising 15 major categorical classifications (commercial services, cultural tourism, residential structures, etc.) spanning Pingyao Ancient City and its 1 km buffer zone. Multi-temporal high-resolution satellite imagery was acquired from the Tianditu platform (China’s national map service platform) across four discrete periods (2014, 2018, 2022, 2024) with spatial resolution ranging from 0.5 to 2 m and atmospheric cloud coverage maintained below 5%. Vector cartographic datasets were obtained from the same geospatial platform, incorporating road network infrastructure, hydrographic systems, and administrative boundary delineations with cartographic precision conforming to 1:10,000 scale accuracy standards. Building footprint geometries were digitally extracted through vectorization of Tianditu base map layers, subsequently validated via field reconnaissance, and subjected to geometric accuracy correction protocols, maintaining spatial positioning tolerances within 2 m deviation thresholds.

3.2.2. Policy Documents and Interviewees

This study employs a multi-source qualitative data collection strategy grounded in triangulation methodology to capture the complex governance dynamics of heritage preservation in Pingyao Ancient City. The first data source encompasses a comprehensive policy document analysis spanning multiple administrative levels, including foundational national legislation such as the Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2017 revision) and the Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages (State Council Decree No. 524), complemented by provincial instruments including the Shanxi Province Pingyao Ancient City Protection Regulations (2009, subsequently amended) and the Shanxi Province Measures for the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages (2019 revision), alongside municipal and county-level implementation frameworks encompassing the Pingyao Ancient City Protection Master Plan (2021–2035) and associated administrative directives. This multi-tiered regulatory analysis provides the institutional context for understanding policy coherence, implementation gaps, and governance effectiveness across different administrative scales.

The second data source consists of primary empirical data collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews. with 50 key stakeholders, strategically selected to represent three critical constituency groups through purposive sampling methodology. Local residents (n = 18) were recruited through stratified sampling across different neighborhoods within the ancient city core to capture spatial variations in preservation experiences, while tourists (n = 20) were selected using systematic intercept sampling at major heritage sites and commercial districts to ensure demographic diversity and varied visit motivations. Heritage site management personnel (n = 7) are responsible for operational oversight of major heritage attractions within the ancient city boundaries, with merchants operating within the historic district (n = 5). These groups had different relationships with the heritage site, and this sampling method captured perspectives from various stakeholder groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of respondents.

The third data source involves systematic content analysis of media discourse examining evaluative coverage and public commentary regarding Pingyao’s preservation measures across multiple platforms, including national outlets (People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, China Daily), regional media (Shanxi Daily, Jinzhong Television), and digital platforms (Weibo, WeChat public accounts, specialized heritage tourism forums), enabling analysis of public perception dynamics, policy legitimacy, and stakeholder response patterns to current governance arrangements. This analysis can better reflect the reasons why those tourists chose not to visit Pingyao.

3.3. Analytical Methods

3.3.1. Spatial Analysis of Land Use

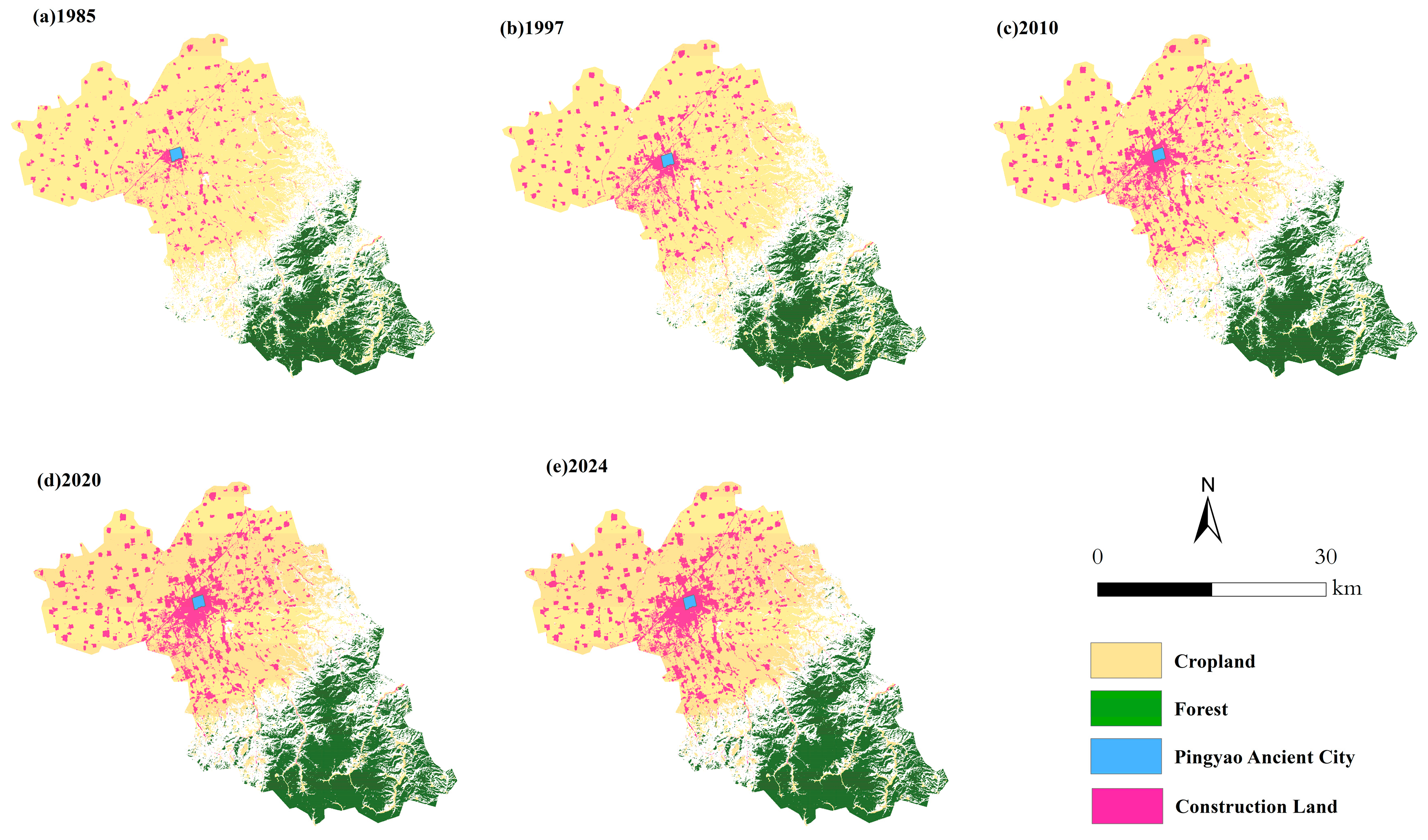

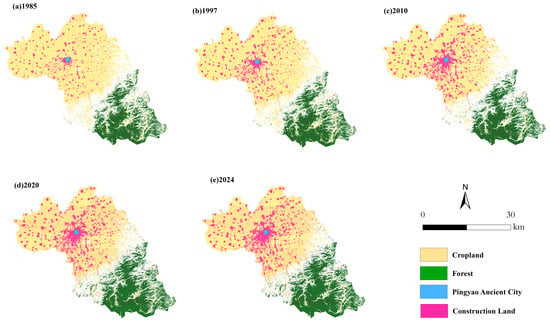

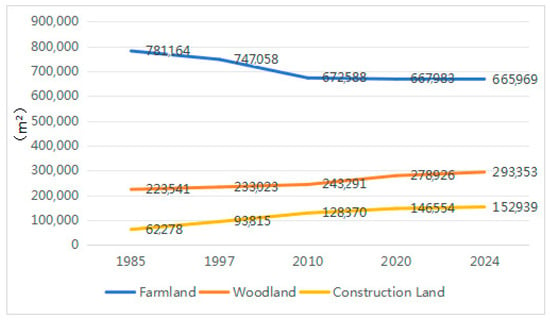

The land use analysis for areas beyond Pingyao Ancient City boundaries employed supervised classification algorithms implemented through ArcGIS 10.8 platform to process the Landsat 5 multispectral datasets. Classification scheme development initially generated five primary land use categories through supervised classification techniques applied to the Landsat multispectral bands. However, for analytical focus and methodological precision, the final classification was consolidated into three core land use types: forestland, cultivated land, and construction land. This simplified classification scheme was selected to capture the most significant land use transitions during China’s reform and opening-up period, particularly those related to urbanization processes, agricultural land conversion, and forest cover changes surrounding the heritage landscape. Temporal change detection analysis was conducted through post-classification comparison techniques to quantify land use transitions and transformation rates across the study periods, enabling comprehensive assessment of regional development patterns in relation to Pingyao Ancient City’s heritage conservation and tourism-driven economic growth (Figure 5, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Land use map of Pingyao County (Source: drawn by Qiang Wang).

Table 2.

Land use classification of Pingyao County.

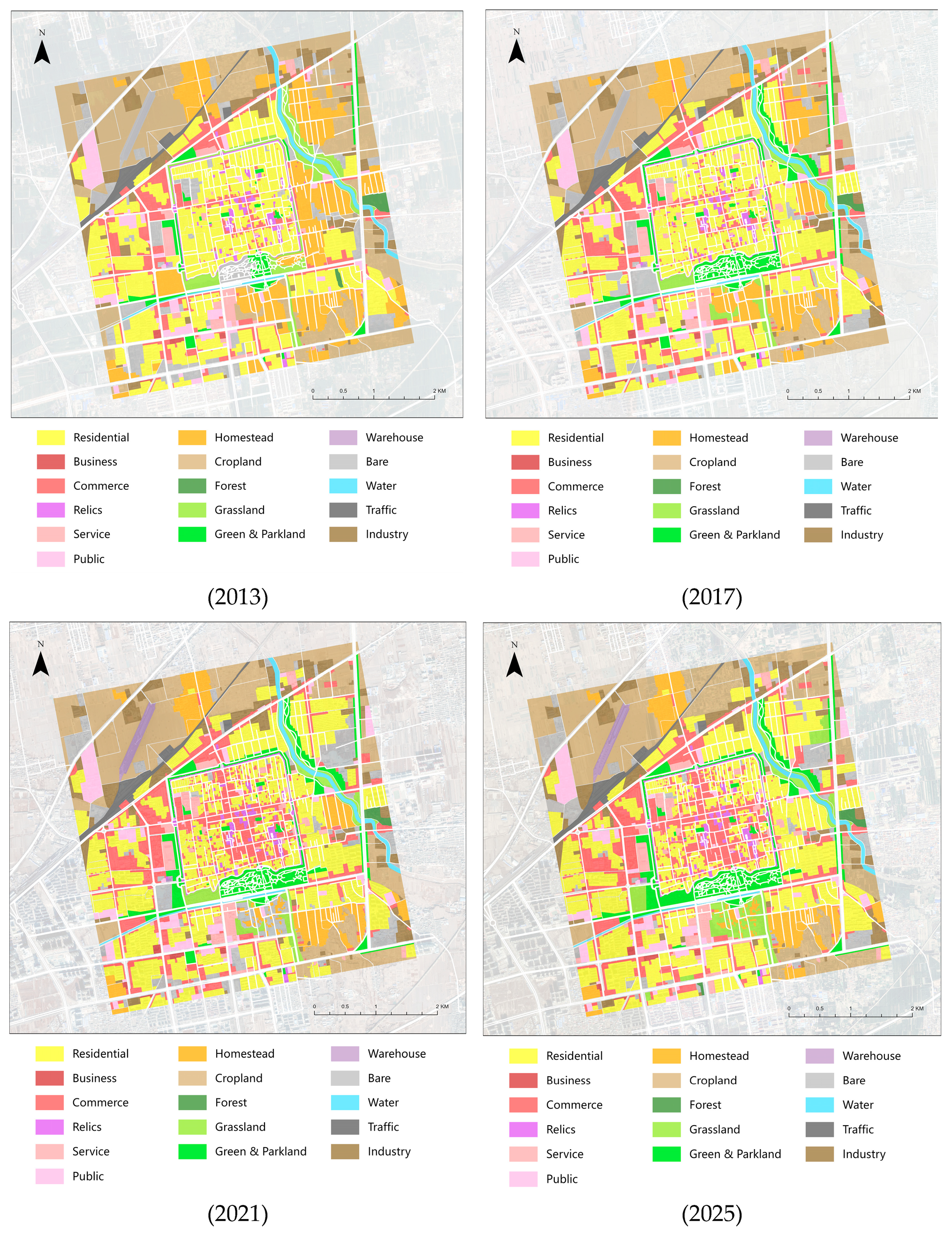

Taking 2013, 2017, 2021, and 2025 as reference years, a dataset of land use changes within Pingyao Ancient City was constructed. Python 3.12 scripts were used to access the Gaode (Amap) Open Platform API to collect Points of Interest (POI) data within the ancient city and a 1.5 km buffer zone, covering 24 major and 272 subcategories. The collected data were imported into ArcGIS and converted into standardized point sets. According to the Land Use Classification and Planning Construction Land Standards and the actual land use characteristics of the ancient city, POI categories were matched to corresponding land use types. Redundant and irrelevant records were removed, and valid samples representing different functional spaces were retained.

Simultaneously, remote sensing images, vector basemaps, and annotation data for the corresponding years were obtained from the Tianditu platform to ensure temporal consistency among multiple data sources. The imagery was preprocessed in ENVI 5.3.1 and ArcGIS pro 3.2, including radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, and geometric correction. Based on the Land Use Guideline, land use patches were interpreted and delineated to generate initial vector layers. The POI data, interpreted results, and annotation layers were then overlaid in ArcGIS to verify and adjust classification inconsistencies and to supplement missing features. The final output was a functional land use classification dataset suitable for area statistics and graphical representation of land use changes within Pingyao Ancient City (Figure 6, Table 3).

Figure 6.

Map of land types in Pingyao Ancient City and its surrounding 1.5 km area (Source: drawn by Qiang Wang).

Table 3.

Land types in Pingyao Ancient City.

3.3.2. Interpretation of Policy Documents

The regulatory framework governing Pingyao Ancient City’s preservation operates through a hierarchical system of interlocking legal instruments that establish protection mechanisms across multiple jurisdictional levels. At the national level, the Cultural Relics Protection Law (2017) provides the foundational legal authority by defining immovable cultural relics (Article 2) and establishing administrative licensing frameworks alongside enforcement mechanisms for violations such as unauthorized restoration or heritage damage [54]. This upper-tier legislation is operationalized through the Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages (State Council Decree No. 524), which institutionalizes the core principles of “scientific planning and strict protection” while mandating adherence to authenticity and integrity standards (Articles 3–4). These regulations explicitly require coordinated financial investment from central and local governments and encourage social participation. In addition, Article 5 delineates the supervisory responsibilities between the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and cultural heritage authorities alongside local governmental accountability structures [55].

There will be some related reports on the internet and in the media.

At the provincial level, the Shanxi Province Pingyao Ancient City Protection Regulations translate these broad principles into specific operational directives. Article 12 mandates that historical building restoration must follow the “no alteration of original condition” principle. The restoration supported by government financial subsidies and technical assistance is requested for maintaining original height, volume, appearance, and color through traditional craftsmanship and materials while requiring remediation or demolition of illegal or non-compliant structures. Article 13 establishes stringent construction limitations within the ancient city boundaries, generally prohibiting new construction and restricting modifications or expansions above the second floor. The underground space development was forbidden except under specific circumstances, including designated renovation zones, essential infrastructure and public service facility needs, or projects that can be archeologically justified for restoration without affecting neighboring relationships. Articles 14–15 further codify prohibited activities, including the demolition or damage of historical buildings and alterations to traditional courtyard structures, while establishing permitting requirements for any reconstruction, modification, or restoration activities, thereby creating enforceable standards for daily regulatory oversight [56]. This regulatory architecture is spatially anchored through the Shanxi Provincial Spatial Planning (2021–2035), which explicitly mandates the strengthening of Pingyao Ancient City’s World Heritage protection by strictly safeguarding traditional urban patterns, including city walls, streets and alleys, waterways, and sight corridors. The planning further promotes coordinated protection of tangible and intangible heritage through digitized archival systems, thus functioning as binding spatial governance constraints that integrate heritage conservation imperatives into broader territorial planning frameworks [57].

3.3.3. Interpretation of Media Reports

The media analysis interprets coverage across official media outlets (China Daily, Xinhua), commercial news platforms (Sohu, Tencent News), and cultural commentary to document public discourse on policy implementation. The interpretation of media reports and interviews examines the relationship between policy objectives and implementation outcomes, identifying operational challenges and achievements in heritage conservation efforts.

Media sources provided documentation of infrastructure and preservation initiatives implemented in Pingyao Ancient City between 2019 and 2025. Official media outlets reported extensively on the underground utility corridor project launched in 2019, which addressed infrastructure challenges including dust control and flood prevention while upgrading water, electricity, and heating systems. Sohu (2019) documented the initiative as a public–private partnership with RMB 1.39 billion investment, covering 121 streets and 30.22 km of underground infrastructure for electricity, telecommunications, water supply, drainage, gas, and fire safety systems [58]. Tencent News (2025) documented the three-year project timeline and integration of smart monitoring systems with subsidies for traditional dwelling maintenance [59]. China News Service reported the project’s adherence to the “three guarantees” principle—heritage protection, historical character preservation, and residential life continuity [60]. Additional media coverage identified implementation variations across different areas of the ancient city. Reports documented that major thoroughfares received comprehensive upgrades, while secondary alleys continued experiencing issues with construction debris, sanitation problems, and infrastructure damage [61]. Cultural commentary in various media outlets raised questions about specific restoration practices, including the replacement of doors, plaques, and stone lions, noting potential impacts on authentic materials and historical architectural integrity [62]. These media sources collectively provided documentation of both infrastructure achievements and ongoing preservation challenges, offering multiple perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of protection policies in Pingyao Ancient City.

4. Results

4.1. Land Use Patterns

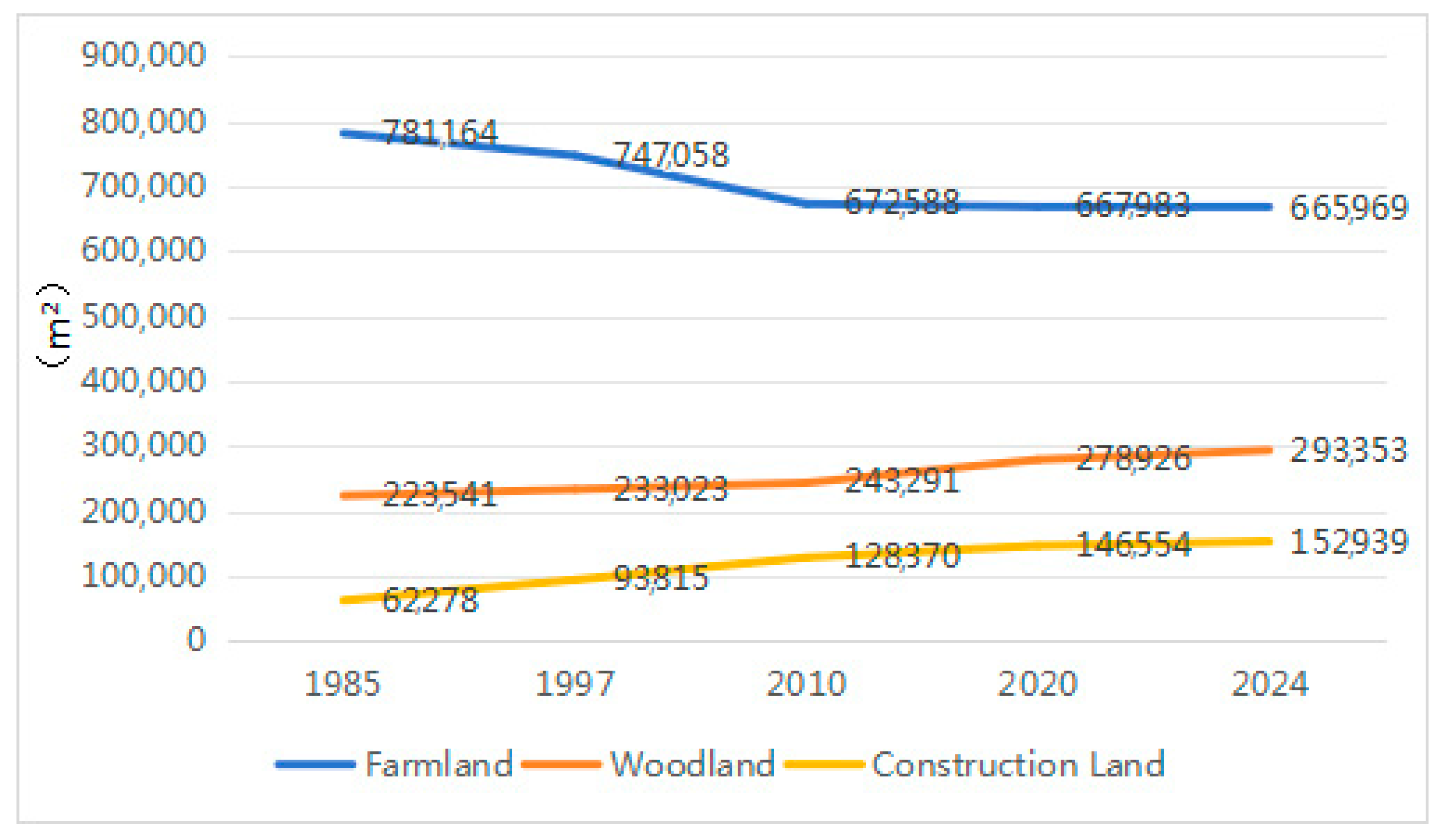

The land use structure outside Pingyao Ancient City underwent significant transformations from 1985 to 2010, characterized by the continuous decline of cultivated land, steady expansion of forest coverage, and rapid proliferation of construction land (Figure 7). Cultivated land demonstrated a persistent decreasing trend, with particularly pronounced reduction during 1997–2010, primarily attributable to large-scale conversion of agricultural land to construction purposes amid rapid urbanization. Construction land exhibited the most dramatic changes, displaying two distinct expansion phases: an initial rapid growth period from 1985 to 1997, followed by peak expansion during 1997–2010 when the maximum increment occurred. This pattern reflects the intensified land demand driven by China’s post-reform economic development and the infrastructure requirements associated with tourism industry growth. In contrast, forest land showed moderate but consistent expansion, likely correlating with government-implemented reforestation policies, enhanced environmental conservation awareness, and the promotion of sustainable development concepts. This land use transformation pattern typifies the process whereby China’s historic cultural cities strive to balance economic development with environmental protection imperatives.

Figure 7.

Changes in Land Use Outside Pingyao Ancient City (Source: drawn by Qiang Wang).

Between 2013 and 2025, the total land area of Pingyao Ancient City remained constant at 2.13 km2, but the internal structure of land use experienced notable adjustments. Residential land declined markedly from 1.459 km2 to 0.818 km2, reflecting the gradual reduction in living space within the heritage zone as stricter preservation regulations limited new construction and some dwellings were converted for non-residential uses. In contrast, commercial land expanded significantly from 0.205 km2 to 0.828 km2 (303%), driven by the adaptive reuse of traditional buildings and the steady growth of tourism-related activities. Service land also increased from 0.031 km2 to 0.097 km2 (213%), corresponding to improvements in infrastructure and visitor facilities. Meanwhile, bare land decreased from 0.085 km2 to 0.024 km2, indicating enhanced land utilization and the restoration of previously vacant plots. Public land and green and parkland grew slightly (0.011→0.016 km2 and 0.036→0.041 km2, respectively), consistent with municipal efforts to optimize public space and environmental quality. The areas of relics (0.131→0.132 km2) and roads (0.173 km2) remained almost unchanged, demonstrating the stability of the city’s historical spatial framework. Overall, these changes suggest a gradual transition from residential and idle land uses toward tourism- and service-oriented functions, shaped by policies emphasizing both heritage conservation and adaptive urban renewal.

The land use changes in Pingyao Ancient City demonstrate distinct spatial variation patterns that reflect the balance between cultural heritage protection and urban development demands. The areas outside the ancient city experienced significant land function transformations from 1985 to 2010, with substantial decreases in cultivated land and rapid increases in construction land, representing typical characteristics of China’s urbanization process. In contrast, while the areas within the ancient city underwent functional adjustments from 2014 to 2024, overall spatial changes remained relatively limited, primarily manifesting as internal functional rezoning. This pattern of intensive external changes alongside relatively modest internal changes indicates that cultural heritage protection policies have imposed significant constraints on spatial development within the ancient city. Strict conservation regulations have limited large-scale construction activities within the ancient city, resulting in urban development demands being primarily accommodated through peripheral area expansion.

4.2. Preservation Policy and Perception

The legal framework governing Pingyao’s heritage preservation demonstrates multi-level coordination mechanisms yet reveals critical implementation gaps between policy design and operational effectiveness. While the Cultural Relics Protection Law (2017) establishes robust foundational principles and the Shanxi Province Pingyao Ancient City Protection Regulations provide detailed operational directives, particularly Article 12’s “no alteration of original condition” mandate and Articles 14–15’s comprehensive prohibition frameworks, the regulatory architecture shows inherent tensions between preservation imperatives and adaptive management needs. The spatial governance constraints embedded within the Shanxi Provincial Spatial Planning (2021–2035) successfully integrates heritage conservation into territorial planning frameworks, but the regulatory emphasis on physical preservation standards inadvertently creates enforcement blind spots regarding intangible cultural continuity and community participation mechanisms. The intangible cultural continuity means sustained transmission, practice, and adaptation of the city’s living cultural expressions, such as traditional crafts, local dialects, festivals, customs, and social values, that preserve the community’s collective identity and historical consciousness within the evolving urban and economic environment. The active involvement of local residents, stakeholders, and cultural practitioners in the decision-making, management, and stewardship of heritage sites ensures that conservation efforts reflect the needs, values, and perspectives of the community while enhancing the sustainability and relevance of cultural preservation in the modern context.

The stakeholders’ perception of heritage protection and development was evident in their interview responses. Thematic analysis of interview responses identified three primary categories, with question design examining heritage tourism management from multiple stakeholder perspectives (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Classification of Question Topics.

Heritage Preservation Perceptions emerged as the most universally acknowledged concern across all stakeholder groups (Table 5). Regarding authenticity concerns, 43 out of 50 participants (86%) expressed concern when asked about the extent to which the historic city retains its original cultural authenticity, with managers showing unanimous concern (7/7, 100%) and residents demonstrating the highest awareness (18/20, 90%). A typical response stated: “The restoration follows traditional methods, but we worry about losing the original spirit of living culture” (Resident, R-12). When evaluating conservation effectiveness, 40 participants (80%) acknowledged current protection efforts, with managers and business operators showing complete satisfaction (7/7 and 5/5, respectively, 100% each), while tourists expressed more moderate approval (12/18, 67%): “Article 12 standards are strict and well-implemented, but enforcement varies in maintaining authentic practices” (Manager, M-03). However, responses to questions about cultural continuity revealed significant divergence, with only 31 participants (62%) expressing satisfaction with traditional practice preservation, notably lower among tourists (9/18, 50%) compared to managers (5/7, 71%): “Physical preservation is excellent, but cultural continuity needs more attention to community traditions” (Tourist, T-28).

Table 5.

Thematic Analysis of Concern or Satisfaction from Stakeholders (n = 50).

The Ancient City Experience Evaluation demonstrated polarized responses between stakeholder groups (Table 5). When asked about spatial navigation experiences, challenges were predominantly identified by tourists (16/18, 89%) and managers (5/7, 71%), while residents showed limited concern (8/20, 40%): “Beautiful architecture but the guidance system fails to provide clear directional support or cultural context” (Tourist, T-25) (Figure 8), Regarding service quality assessment, 38 out of 50 stakeholders (76%) identified deficiencies, with managers showing the highest dissatisfaction (6/7, 86%): “Management services have improved but cultural interpretation services remain inadequate” (Resident, R-08). When discussing commercial atmosphere perceptions, 40 participants (80%) expressed concerns, with residents showing particular dissatisfaction (17/20, 85%): “Too many souvenir shops selling mass-produced items, the commercial environment lacks authentic cultural experiences” (Tourist, T-31) (Figure 9). Questions about cultural interpretation adequacy revealed strong dissatisfaction among tourists (17/18, 94%) and universal concern from managers (7/7, 100%), while residents showed moderate concern (12/20, 60%).

Figure 8.

Century-old buildings with signs in Pingyao Ancient City (Photos were taken on-site by Qiang Wang).

Figure 9.

Commercial streets in Pingyao Ancient City (Photos were taken on-site by Qiang Wang).

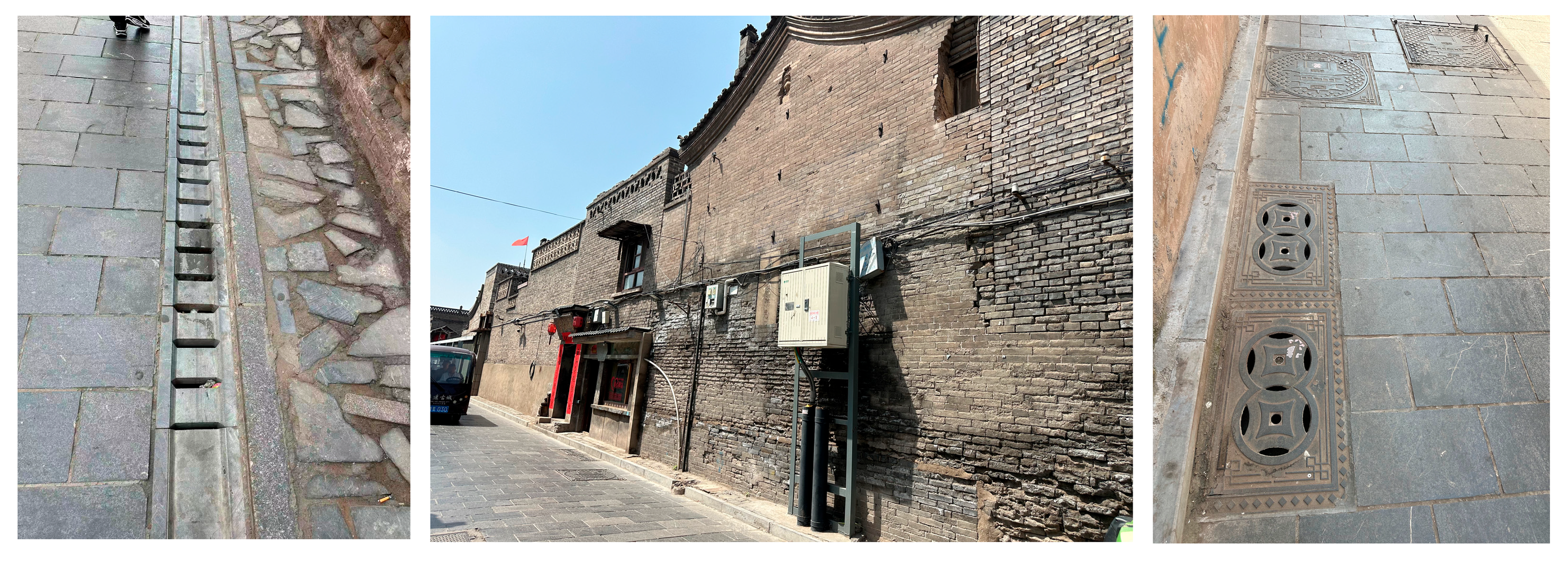

The Infrastructure Transformation Assessment revealed stakeholder-specific priorities (Table 5). When asked about utility improvements, residents showed strong appreciation (17/20, 85%) along with managers (6/7, 86%), while tourists demonstrated limited awareness (8/18, 44%): “Drainage and electrical systems significantly improved, but installation disrupted traditional architectural integrity” (Resident, R-01) (Figure 10). Regarding accessibility features evaluation, tourists expressed high satisfaction (16/18, 89%) with managers providing unanimous support (7/7, 100%), while residents remained moderately supportive (11/20, 55%): “Wheelchair access and pathway improvements are excellent, though protection policies have restricted facility renovations” (Manager, M-02) (Figure 11). When assessing visitor facility adequacy, 30 participants (60%) identified shortcomings, with business operators showing strong support (4/5, 80%) while residents demonstrated the lowest satisfaction (9/20, 45%): “Infrastructure esthetically improved, but basic amenities like drinking water and rest areas are insufficient for 5A scenic area standards” (Tourist, T-15).

Figure 10.

Infrastructure Renovation Project of Pingyao Ancient City (Photos were taken on-site by Qiang Wang).

Figure 11.

Road renovation in Pingyao Ancient City (Photos were taken on-site by Qiang Wang).

The stakeholder response analysis revealed distinct orientations toward heritage preservation and tourism development. Tourists demonstrated experience-centered perspectives, emphasizing spatial navigation and cultural interpretation as essential elements of their visits. They maintained relatively open attitudes toward technological integration but expressed concern that excessive commercialization could compromise the authenticity of cultural experiences. Local stakeholders, including residents, business operators, and heritage site managers, shared generally community-oriented perspectives that prioritize both heritage preservation and local well-being. Residents emphasized infrastructure improvements to enhance daily living conditions and maintain heritage authenticity, often showing resistance to extensive commercial development and limited engagement with technological innovation. Heritage site managers adopted balanced approaches, supporting conservation and accessibility improvements while upholding service and interpretation standards. Business operators displayed pragmatic adaptation strategies, aligning commercial objectives with conservation goals through moderate development initiatives. Collectively, these local stakeholders tend to hold an overly optimistic view of tourism development outcomes, which diverges from visitors’ actual experiential concerns. This divergence reflects differing expectations between those who live and work within the heritage site and those who experience it primarily as tourists, highlighting the need to reconcile local development optimism with visitors’ perceptions of authenticity and experience quality.

Media coverage analysis reveals a structured discourse that amplifies official policy achievements that peripheralizes critical assessment of preservation authenticity and community impact. Authoritative outlets such as China Daily, Xinhua, and China News Service consistently frame the RMB 1.39 billion infrastructure investment as exemplifying successful heritage-development integration, emphasizing technical specifications (121 streets, 30.22 km of utilities) and policy compliance (“three guarantees” principle), which also minimizes discussion of cultural preservation challenges or community displacement concerns. However, specialized cultural commentary surfaces more nuanced critiques, particularly regarding restoration practices that prioritize visual improvement over material authenticity, as stakeholders are concerned about “repairing the old as old” principal violations. The media narrative’s emphasis on quantifiable infrastructure improvements parallels regulatory frameworks’ focus on measurable preservation standards, but both largely overlook qualitative dimensions of cultural continuity and authentic heritage experience. This pattern suggests that media discourse reinforces institutional priorities for technical modernization while inadvertently marginalizing community voices and cultural authenticity concerns that emerge prominently in direct stakeholder engagement.

The convergence of findings across regulatory analysis, stakeholder interviews, and media discourse reveals a systematic pattern of heritage preservation approaches that prioritize static physical conservation and infrastructure modernization but inadequately address cultural authenticity and community integration dimensions. Legal frameworks establish effective protection mechanisms for tangible heritage elements but lack robust provisions for intangible cultural continuity. Stakeholder experiences confirm technical preservation success alongside cultural concerns, while media narratives reinforce policy achievement frames. This triangulation demonstrates that current heritage preservation paradigms in Pingyao operate within a “conservation-development” framework that successfully maintains physical heritage integrity and improves visitor infrastructure, yet systematically underemphasizes the social, cultural, and experiential dimensions essential for authentic “living heritage” sustainability.

5. Discussion

The tourism decline experienced by Pingyao Ancient City results from complex spatial and policy dynamics that prioritize heritage conservation over the functional integration of modern tourism infrastructure. Our analysis reveals a critical disconnect between the heritage preservation efforts and the evolving expectations of contemporary tourists. The land use transformation within Pingyao’s ancient city boundaries showcases the tension between conserving historical urban fabric and meeting the demands for modern tourist amenities. Despite substantial investments in infrastructure and preservation, the spatial design remains predominantly rigid, dividing heritage areas from newly developed tourist zones. This segmentation disrupts the fluidity needed for creating a seamless visitor experience, which ultimately diminishes the city’s competitiveness in the heritage tourism market.

Spatial analysis of land use changes illustrates this challenge. While the city’s preservation policies effectively safeguard its architectural integrity, they also limit spatial flexibility. This restriction hinders the expansion of public spaces that are crucial for facilitating improved visitor experiences. The data points to an overall reduction in residential space, with a corresponding rise in commercial land use. However, the lack of sufficient space allocated for services and public amenities has created gaps in the delivery of an integrated tourist experience. This reinforces the dilemma where efforts to conserve the past—through strict land use regulations and architectural controls—have unintentionally obstructed the city’s ability to cater to contemporary tourism needs. Although the area maintains a strong cultural and historical character, the limited availability of modern amenities restricts the quality of tourism services, resulting in an imbalance between preservation goals and tourism functionality.

The paradox of heritage tourism in Pingyao is underscored by policy frameworks that, while achieving conservation success, inadvertently impede the dynamic engagement necessary for authentic cultural exchange. Our findings highlight the conflict between preservation efforts focused on physical integrity and the demand for adaptive, experiential tourism that allows for interaction with living culture. This disconnect stems from a conservative preservation model that treats heritage sites as static artifacts rather than evolving cultural landscapes. While policy documents such as the Cultural Relics Protection Law (2017) emphasize physical preservation, they lack provisions for maintaining the intangible aspects of heritage, such as local traditions, community practices, and the intangible qualities of cultural identity. These aspects are vital to ensuring that the city remains a living heritage site, rather than a museum piece, which can keep pace with the evolving needs of both residents and tourists.

Moreover, the relocation of residents and the transformation of their spaces into commercial tourism venues have led to a significant alteration of the city’s social fabric. The systematic displacing of the local population, though intended to protect the heritage site, has disrupted the continuity of traditional cultural practices. The local community, which once served as the custodians of Pingyao’s living heritage, has been gradually replaced by a transient population, diluting the authenticity of the cultural experiences offered to tourists. These changes reflect a deeper tension within heritage tourism management, where the goal of economic revitalization through tourism development often comes at the expense of preserving the social and cultural integrity of the community.

Interviews with stakeholders reveal that this issue is keenly felt by both local residents and tourists. While local managers and business operators express general satisfaction with the preservation efforts, there is considerable concern regarding the commercialization of cultural practices, which increasingly focus on tourist demand rather than the preservation of authentic local traditions. Local residents, in particular, emphasize the loss of their traditional way of life and the growing disparity between their lived experiences and the commercialized, curated tourist experiences. These sentiments are echoed by tourists, who express dissatisfaction with the growing focus on souvenir shops and the lack of meaningful cultural encounters during their visits. The media’s coverage of Pingyao’s preservation and development projects further amplifies these tensions. Official media outlets highlight infrastructure improvements and policy achievements, presenting a narrative of success in heritage conservation and tourism development. However, these reports often downplay critical issues related to the authenticity of cultural experiences and the displacement of local communities. Cultural commentators and alternative media sources offer more critical perspectives, questioning the extent to which Pingyao’s heritage is truly preserved in its living form and calling attention to the risks of commodification and cultural erosion.

Ultimately, the findings suggest that the decline in Pingyao’s tourism competitiveness is not solely due to external factors, such as market competition or infrastructure challenges, but rather the result of an internal misalignment between preservation goals and tourism strategies. The overemphasis on physical conservation and infrastructure development, while essential for safeguarding the city’s historical identity, has created barriers to the dynamic engagement required for sustainable tourism growth. To address these challenges, future policies must adopt a more holistic approach that balances physical conservation with the preservation of intangible cultural heritage, facilitates community participation in the decision-making process, and integrates modern tourism infrastructure in ways that enhance, rather than detract from, the authenticity of the visitor experience.

6. Conclusions

Through an examination of land use changes, policy frameworks, stakeholder perspectives, and media narratives, this research reveals the complex tensions between heritage preservation and contemporary tourism development pressures in Pingyao Ancient City. The findings highlight how tourism growth, urban expansion, and economic modernization have shaped both opportunities and challenges for Pingyao’s conservation trajectory. Heritage conservation in Pingyao cannot be understood in isolation from broader socio-economic forces but rather emerges from the dynamic interplay between formal policy interventions, stakeholder negotiations, and evolving tourism demands. While Pingyao has achieved notable success in maintaining its architectural integrity and securing UNESCO World Heritage status, the static protection of heritage still has a certain negative impact on local tourism. The ongoing pressures related to commercialization, resident displacement, and the balance between authenticity and accessibility pose significant challenges to the development of Pingyao Ancient City. The systematic challenges identified in Pingyao’s tourism decline require transformative strategies that prioritize cultural value preservation as the foundation for sustainable competitive advantage. More specific measures have been suggested for implementation. Implement a divisional and tiered conservation plan prioritizing the integrity of numbered historic structures and urban fabric, while using digital storytelling and immersive exhibitions to enhance visitor engagement, such as VR and AR technology. Encourage adaptive reuse of traditional buildings for cultural industries, ensuring interventions remain reversible and historically respectful. Develop training programs for local artisans to sustain and pass on traditional craftsmanship.

Several limitations should be acknowledged regarding the scope and approach of this research. The analysis centers on a single case—Pingyao Ancient City, meaning the findings are closely tied to its specific historical, political, and cultural context and may not be directly generalized to other heritage cities. The research mainly addresses land use change, policy frameworks, stakeholder perspectives, and media narratives, while paying less attention to broader regional economic dynamics, demographic change, real estate pressures, or climate-related factors that may also shape heritage-city development. Moreover, the study does not fully engage with intangible heritage practices, community rituals, or intergenerational cultural transmission, which are important for the long-term vitality of historic cities. Future research could incorporate more systematic comparative perspectives and examine the interplay of regional economies, demographic transitions, and lived cultural practices to provide a more holistic understanding of heritage conservation dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W.; methodology P.M.; software, Q.W.; formal analysis, Q.W. and Y.W.; investigation, P.M.; resources, Q.W. and Y.W.; data curation, Q.W. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W.; writing—review and editing, P.M. and Y.W.; supervision, P.M.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by 2025 Zhejiang Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (grant number 25NDJCO13YB) and 2025 Zhejiang Provincial Department of Science and Technology “Pioneer Leading Eagle + X” Science and Technology Program (grant number 2025C02042).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Zhejiang University of Technology Research Institute for the Southern Song Ancient Capital (protocol code ZJGYDXSR2025004 and 08 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the research on sustainable development of cultural tourism in Pingyao Ancient City, led by Assistant Researcher Ma Pengfei at our institute, employed semi-structured interviews with participants including tourists, local residents, vendors, and heritage managers involved in cultural tourism and heritage conservation. The study adopted a low-risk approach for participants, and under normal circumstances, no written informed consent would be required for similar situations outside the research context. Therefore, there is little risk to the subjects in this study, and they may not be required to sign an informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dai, R.; Zhang, Z. Cultural heritage and tourism development: Exploring strategies for the win-win scenario of heritage conservation and tourism industry. Geogr. Res. Bull. 2024, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zang, T.; Zhou, T.; Ikebe, K. Historic Conservation and Tourism Economy: Challenges Facing Adaptive Reuse of Historic Conservation Areas in Chengdu, China. Conservation 2022, 2, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, T.; Zhang, Y.; An, S. A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.-W. Approaches to sustaining people–place bonds in conservation planning: From value-based, living heritage, to the glocal community. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart hospitality—Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; McKercher, B.; Schweinsberg, S. From tourism and disability to accessible tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, B.; Cai, L. Tourism development of World Heritage Sites in China: A geographic perspective. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ryan, C. Place attachment, identity and community impacts of tourism—The case of a Beijing hutong. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Communique on the Development of Culture and Tourism in 2019 by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/tjxx/202012/t20201204_906491.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Su, X.; Teo, P. The Politics of Heritage Tourism in China: A View from Lijiang; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y. In search of authenticity in historic cities in transformation: The case of Pingyao, China. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2011, 9, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G. Community Participation in Tourism at a World Heritage Site: Mutianyu Great Wall, Beijing, China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. Cities 2020, 97, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National People’s Congress of China. Law of the People’s Republic of China on Cultural Relics Protection. Available online: http://en.npc.gov.cn.cdurl.cn/2024-11/08/c_1115996.htm (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Sofield, T.; Li, S. Tourism governance and sustainable national development in China: A macro-level synthesis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 501–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ouyang, X.; Du, K.; Zhao, Y. Does government transparency contribute to improved eco-efficiency performance? An empirical study of 262 cities in China. Energy Policy 2017, 110, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. Authenticity & aura. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Lee, S.H.; Olson, E.D. Authenticity in Tourism in Small Island Destinations: A Local Perspective. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2013, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabian, P.; Arai, S.M. Tourist perceptions of souvenir authenticity: An exploration of selective tourist blogs. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. The Tourist-Historic City; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, A.K.; Creswell, J.W.; Saville, N. (Eds.) Second Language Assessment and Mixed Methods Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781316505038. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.; Faulkner, B. Entrepreneurship, Chaos and the Tourism Area Lifecycle. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Re-sources. Can. Geogr./Géogr. Can. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Human–environmental relations with tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts and Opportunities; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.R. Introductory Digital Image Processing: A Remote Sensing Perspective; Pearson: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, E.F.; Geist, H.J. Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: Local Processes and Global Impacts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McGarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A.; Ene, E. FRAGSTATS v4: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical and Continuous Maps. Comput. Softw. Program Prod. By Authors Univ. Mass. 2012, 15, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wu, J. Use and misuse of landscape indices. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. Foundations: Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions (1995); Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0521479806. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.G.; Gardner, R.H.; O’Neill, R.V. Landscape Ecology in Theory And practice: Pattern and Process; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; ISBN 0387951229. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Decrop, A. Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Miller, G.J. Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson: London, UK, 1993; Available online: https://scholar.aigrogu.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0,5&q=Sabatier,+P.+A.,+%26+Jenkins-Smith,+H.+C.+(Eds.).+(1993).+Policy+change+and+learning:+An+advocacy+coalition+approach.+Westview+Press.&btnG= (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Meyer, D. Power and tourism policy relations in transition. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E.; Guo, L. Agenda—Setting Influence of the Media in the Public Sphere. In The Handbook of Media and Mass Communication Theory; Fortner, R.S., Fackler, P.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 249–268. ISBN 9780470675052. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Tourism Spaces; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Managing Heritage and Cultural Tourism Resources; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781315249933. [Google Scholar]

- Kaixin, X.; Hiromu, I.; Changze, L. Exploring factors influencing the characteristics of historic cities: The case of the Ancient City of Pingyao, China. Plan. Perspect. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Lu, S. Enhancing emotional responses of tourists in cultural heritage tourism: The case of Pingyao, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2024, 19, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Q. Comparative analysis of photographic and general tourists’ experiences in heritage sites: A tripartite model study in Pingyao Ancient City. J. Herit. Tour. 2025, 20, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fyall, A.; Zheng, Y. Heritage and tourism conflict within world heritage sites in China: A longitudinal study. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 110–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Ancient City of Ping Yao. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/812/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Li, X.; Hou, W.; Liu, M.; Yu, Z. Traditional Thoughts and Modern Development of the Historical Urban Landscape in China: Lessons Learned from the Example of Pingyao Historical City. Land 2022, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Office Beijing. Practical Conservation Guidelines for Traditional Courtyard Houses and Environment in the Ancient City of Pingyao; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France; Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X. Reconstructing Tradition: Heritage Authentication and Tourism-Related Commodification of the Ancient City of Pingyao. Sustainability 2018, 10, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2017 Amendment). Available online: http://www.csrcare.com/Law/LawShowEn?id=233722 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages (Decree No. 524). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/flfg/2008-04/29/content_957342.htm (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Shanxi Provincial People’s Congress Standing Committee. Shanxi Province Pingyao Ancient City Protection Regulations (2018 Amendment). Available online: http://www.ce.cn/culture/gd/201811/05/t20181105_30703827.shtml (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Shanxi Provincial Government. Shanxi Provincial Spatial Planning (2021–2035). Available online: https://www.shanxi.gov.cn/zfxxgk/zfxxgkzl/fdzdgknr/lzyj/szfwj/202404/t20240403_9531920.shtml (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Sohu.com. Total Investment of 1.39 Billion Yuan! The Infrastructure Upgrade and Reconstruction Project of Pingyao Ancient City is Progressing Steadily! Available online: https://m.sohu.com/a/352339432_230731/?pvid=000115_3w_a&push_animated=1&f_link_type=f_linkinlinenote&webview_progress_bar=1&show_loading=0&flow_extra=eyJpbmxpbmVfZGlzcGxheV9wb3NpdGlvbiI6MCwiZG9jX3Bvc2l0aW9uIjoxLCJkb2NfaWQiOiI3NzViNTViOTkzNjZkNWUwLTk0ODcwNDFiNmQwMTZmMzYifQ%3D%3D&theme=light (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Tencent News. Underground City Project in Pingyao Ancient City. Tencent News (Originally from Guangming Daily). Available online: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7502265576799126025/?&source=m_redirect&wid=1756366696823 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- China News Service. Pingyao, Shanxi Accelerates Infrastructure Renovation and Quality Improvement of the Millennium-Old Ancient City. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/sh/2021/06-26/9507805.shtml (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Sohu.com. Thoughts on the Development and Protection of Pingyao Ancient City. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/602799427_121188364 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Wenkub. Current Situation and Development of Residential Buildings in Pingyao Ancient City. Available online: https://www.wenkub.com/doc-118421873.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).