Abstract

Understanding sediment transport under varying flow regimes and its associated scouring–silting responses is fundamental for analyzing the coupled dynamics of hydrology and river morphology. However, in large alluvial rivers strongly modified by human interventions such as dam operations, identifying critical thresholds of scouring–silting transitions remains a major challenge. This study examines sediment transport dynamics and flow frequency patterns through statistical analysis and the coefficient of determination method, using daily discharge and suspended sediment concentration records from eight hydrological stations along the middle and lower Yangtze River, China, covering 1990–2023. The results demonstrate that the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir substantially altered downstream hydrological and sediment regimes, leading to a more uniform flow frequency distribution, suppression of extreme flows, and increased prevalence of moderate discharges. These adjustments stabilized river flows and improved sediment transport efficiency. Distinct spatial variations were identified across seven river sections: upstream reaches shifted from bimodal scouring–silting patterns to scouring-dominated regimes, whereas downstream reaches exhibited weakened sediment deposition. Moreover, critical thresholds of both flow and sediment coefficients displayed systematic longitudinal shifts. Collectively, these findings provide new insights into water–sediment interactions under large-scale regulation and offer practical implications for sediment management in highly engineered river systems.

1. Introduction

Sediment transport dynamics play a pivotal role in fluvial morphodynamics, directly shaping channel stability, river evolution, and the balance between scouring and silting [1,2]. These processes arise from the complex interplay among river hydrodynamics, sediment supply, and bed material characteristics [3]. Variability in sediment transport can trigger profound morphological adjustments, particularly in alluvial river systems [4]. Accurately identifying the threshold conditions that govern scouring–silting transitions is therefore critical for predicting river evolution, optimizing channel management, and safeguarding riverine ecosystems [5]. However, due to the combined influences of discharge, flow velocity, sediment load, bed composition, vegetation cover, and climate variability, sediment transport exhibits strong nonlinearity and spatiotemporal heterogeneity, making precise determination of thresholds highly challenging [6,7].

Over recent decades, human interventions—especially the construction and operation of large-scale hydraulic infrastructure—have profoundly altered sediment regimes in many major rivers worldwide [8]. Dams not only intercept upstream sediment but also modify downstream hydrology, producing substantial shifts in scouring–silting patterns [9]. In China, the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest operational hydropower project, has exerted far-reaching impacts on sediment balance and channel morphology in the Yangtze River basin [10,11]. Since its impoundment, the reservoir has trapped much of the upstream sediment load, drastically reducing sediment transport to the middle and lower reaches. This reduction has triggered bed erosion, bank retreat, and channel contraction in multiple downstream sections [12]. Moreover, reservoir regulation strategies—such as flood-season storage and dry-season release—have restructured the downstream flow regime, further complicating the hydrological conditions under which scouring and silting occur [13,14].

The middle and lower Yangtze River thus represent one of the world’s most severely impacted alluvial river systems, providing a critical case study for understanding how anthropogenic interventions reorganize sediment transport thresholds across timescales [15]. Recent advances in remote sensing, data mining, and artificial intelligence have enabled more integrated analyses of sediment dynamics [16,17]. By combining hydrodynamic modeling, statistical approaches, machine learning predictions, and field monitoring, researchers are now able to better capture the multifactorial controls and evolving patterns of sediment transport [18]. These efforts form a vital foundation for sustainable water resources management and river protection.

This study seeks to quantify shifts in scouring–silting thresholds across different reaches of the middle and lower Yangtze River before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Dam. Unlike earlier studies that primarily described broad patterns of channel adjustment or sediment budgets at the basin scale, we explicitly identify and compare critical discharge and sediment coefficient thresholds across multiple river sections [19,20]. Our methodological framework integrates flow frequency analysis, threshold identification, and statistical classification to examine how the hydrodynamic conditions governing channel stability have evolved. Based on daily water and sediment data from eight mainstream hydrological stations spanning 1990–2023, this study reveals: (a) the magnitude and direction of threshold shifts under different flow regimes; (b) the longitudinal propagation of scouring effects downstream of the dam; (c) the transformation of sediment transport mechanisms in a highly regulated alluvial river.

2. Study Area and Data

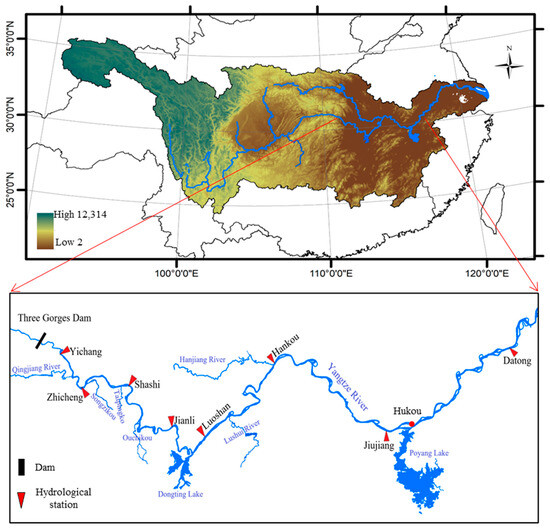

2.1. Study Area

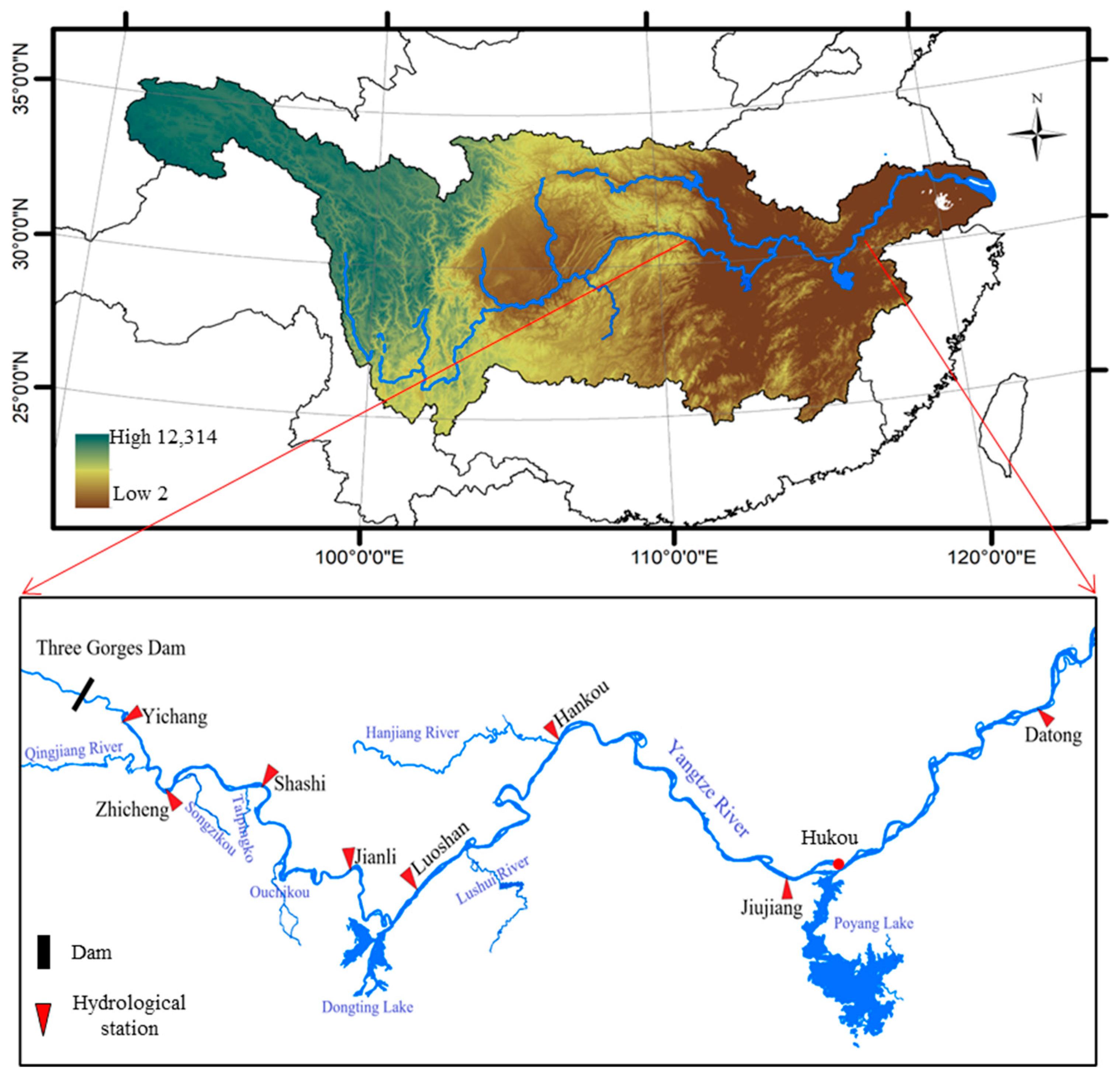

The study area for this paper lies downstream of the Three Gorges Reservoir, encompassing the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River from Yichang to Datong, approximately 1183 km long [21,22]. The Yichang to Hukou section, representing the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, is approximately 955 km long and comprises three main reaches. The Yizhi river section, approximately 60.8 km long, marks the transition from a mountainous river to a plain river. It is dominated by low hills, exhibits strong resistance to erosion, and has a predominantly coarse-grained riverbed. The Jingjiang river section, approximately 347.2 km long, is divided into the Upper Jingjiang (171.7 km) and Lower Jingjiang (175.5 km) at Ouchikou. The Upper Jingjiang section features numerous bends and well-developed mid-channels, making it a slightly meandering river [23,24]. The Lower Jingjiang section, on the other hand, is highly sinuous and exhibits dramatic riverbed evolution, making it a typical strongly meandering river. The Chenglingji to Hukou section, approximately 547 km long, is characterized by a lotus-shaped, bifurcated channel, alternating between wide and narrow sections. This section of the river is fed by the upper Jingjiang River and Dongting Lake, and its lower reach are influenced by Poyang Lake [25,26]. Overall water and sediment conditions are controlled by nodes of varying densities. The section from Hukou to Datong belongs to the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, with a total length of approximately 228 km. This section of the river is dominated by a lotus-shaped, bifurcated channel, alternating between wide and narrow, with numerous mid-channel shoals and a crisscrossing network of distributaries [27,28,29].

Daily discharge and sediment concentration data from eight hydrological stations along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (Figure 1) were used in this study [30,31,32]:

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the river channel downstream of the Three Gorges Dam.

- Yichang Station was established in April 1887. It serves as a control station for the Three Gorges Reservoir’s outflow and directly reflects changes in water and sediment conditions after reservoir regulation.

- Zhicheng Station was established in June 1925. It is located at the beginning of the Jingjiang river section and serves as a water and sediment control station after the upstream Qingjiang River joins the Yangtze River.

- Shashi Station was established in January 1933. It is located on the upper Jingjiang River and reflects water and sediment conditions after the diversions at Songzikou and Taipingkou.

- Jianli Station was established in August 1950. It is located on the lower Jingjiang River and serves as a water and sediment control station after the diversion at Ouchikou.

- Luoshan Station was established in August 1950. It is located downstream of Dongting Lake and serves as a water and sediment control station after the confluence of Dongting Lake.

- Hankou Station was established in January 1865. It serves as a water and sediment control station after the confluence of the Hanjiang River.

- Jiujiang Station was established in January 1904. It is located upstream of Poyang Lake and monitors water and sediment conditions before the confluence with Poyang Lake.

- Datong Station was established in October 1922. It serves as a water and sediment control station after the confluence of Poyang Lake.

The following descriptions refer to the cross-sectional composition of the riverbed at each hydrological station. At Yichang Station, the riverbed is composed of concrete, sand, pebbles, and rubble, with pebbles predominating, demonstrating strong resistance to erosion and a relatively coarse riverbed. At Zhicheng Station, the riverbed is sandy from the left bank to 1100 m from the starting point, while from 1100 m to the right bank, it becomes a reef-slab riverbed, with pebbles predominating overall. At Shashi Station, the riverbed is composed of sand and clay, with sand being the predominant material and a finer texture. At Jianli Station, the riverbed is composed of fine sand from 180 to 1200 m from the starting point, with soil on the left bank and rock slabs on the right bank, resulting in a sandy overall riverbed. At Luoshan Station, the riverbed is predominantly sandy, with reef-slab soil forming about 135 m from the starting point. At Hankou Station, the left bank is composed of fine sand and silt, while the right bank is composed of coarse sand, with sand predominating overall. At Jiujiang Station, the left bank is composed of silt, while the right bank has a reef-slab riverbed, also predominantly sandy. At Datong Station downstream, the riverbed on the left bank is composed of fine sand and silt, the middle section is coarse sand, and the right bank is rocky, resulting in a predominantly sandy riverbed. The upper reaches of the Yangtze River are dominated by a coarse-grained riverbed with strong erosion resistance, while the middle and lower reaches are predominantly sandy, demonstrating a greater susceptibility to erosion and sedimentation. This contrast in riverbed texture not only influences the transport capacity of water and sediment but also plays a key role in channel morphological evolution and ecological responses [33,34].

2.2. Data Sources

This study collected daily discharge and suspended sediment concentration (SSC) data from eight mainstream hydrological stations along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River—namely Yichang, Zhicheng, Shashi, Jianli, Luoshan, Hankou, Jiujiang, and Datong (Figure 1)—covering the period from 1990 to 2023. These data were obtained from the Hydrology Bureau of the Changjiang Water Resources Commission (CWRC). Based on these eight stations, the mainstem of the Yangtze River was divided into seven river section, each named according to the combination of its upstream and downstream control stations (Table 1) [35,36].

Table 1.

Basic information of the hydrological stations.

The time series of water and sediment data was divided into three periods: (1) 1990–2002, representing the natural condition period, which corresponds to the construction phase of the Three Gorges Project, prior to reservoir impoundment; (2) 2003–2008, classified as a non-natural condition period, representing the early stage of reservoir impoundment; and (3) 2009–2023, also under non-natural conditions, during which the Three Gorges Dam was fully operational and the water level was raised to the designed elevation of 175 m. Due to variations in monitoring periods among the stations, detailed information for each hydrological station is provided in Table 1.

3. Methods

3.1. Flow Frequency Analysis Method

When dealing with long-term streamflow records, the interval-based frequency statistical method is commonly used to accurately determine the occurrence frequency of various flow levels [37]. This method involves grouping and analyzing discharge data to effectively reveal the probability distribution and temporal variability of different flow magnitudes. However, special considerations are required in practical applications to ensure both the accuracy and continuity of the statistical results. To compute the frequency distribution of flow levels, this study carefully evaluated the number of intervals to be used, with the aim of achieving a smooth and continuous empirical frequency curve. In this study, the flow intervals were divided into 50 classes. This choice reflects a balance between computational efficiency and result resolution. The flow ranges across the eight hydrological stations are relatively large ([2000, 60,000] to [10,000, 84,000] m3/s), making the selection of an appropriate discretization particularly important. Using too few intervals (e.g., 10–20) would over-smooth the data and mask important nonlinear transitions, whereas too many intervals (e.g., 100–200) would significantly increase computational cost and introduce random noise, potentially leading to overfitting. Preliminary tests confirmed that 50 intervals provide sufficient resolution to capture the scouring–silting variability while maintaining stable performance. Moreover, this discretization is consistent with the interval division adopted for the sediment coefficient calculation, ensuring methodological coherence across the analysis. Daily streamflow data from eight hydrological stations located downstream of the Three Gorges Dam were analyzed for the period 1990–2023 [38].

The detailed steps for the statistical analysis are as follows:

- (1)

- Determine the minimum and maximum daily flow values within each time series at each station, denoted as and , respectively.

- (2)

- Divide the flow range into 50 equal-width intervals using the following expression for the interval:For i = 1, 2, …, 50.

- (3)

- Count the number of days the flow falls within each interval during each period, and calculate the probability density for each flow class using:where is the probability density for the i-th flow interval; is the number of days that flow occurred within the i-th interval; and is the total number of days in the respective time series.

3.2. Discrimination Coefficient Calculation

In previous studies, the sediment coefficient has been commonly defined as the ratio of suspended sediment concentration (SSC) to water discharge, serving as an indicator to quantify the relative sediment content in incoming water and to reflect sediment concentration per unit of flow [39]. This parameter provides insight into sediment transport efficiency under varying hydrological conditions. For example, Wu defined the sediment coefficient as the ratio of SSC to discharge to analyze sediment yield dynamics in the middle reaches of the Yellow River, and found that it effectively captured seasonal sediment transport responses under varying runoff regimes [40].

In this study, the sediment coefficient () is calculated based on the average sediment concentration (S) and average discharge (Q) for each distinct flow regime. The first two formulas calculates the average discharge () and the average sediment concentration () for a specific flow regime i. The third formula calculates the sediment coefficient () for a specific flow regime i [41].

The statistical analysis are as follows:

Here, represents the individual discharge measurements within that flow regime, and n is the total number of measurements. The sum of all discharge measurements () is divided by the number of measurements (n) to obtain the average discharge. represents the individual sediment concentration measurements corresponding to each discharge measurement within that flow regime. The sum of the products of each discharge and its corresponding sediment concentration () is divided by the sum of all discharge measurements () to obtain the average sediment concentration. is the ratio of the average sediment concentration () to the average discharge (). The sediment coefficient , with a dimensional unit of kg·s/m6, provides a measure of the sediment load per unit discharge and is introduced to characterize the relationship between water discharge and sediment load, serving as a key parameter in assessing the sediment transport characteristics and intensity of the flow regime.

3.3. Sediment Scouring and Deposition Quantification

The sediment transport amount, denoted as , represents the net scouring or deposition under each flow interval. It is calculated as the difference between the inflow and outflow sediment loads at the corresponding flow level. A positive indicates net deposition, while a negative indicates net scouring. The net sediment transport for each flow interval i is calculated as:

where and are the average discharge and sediment concentration at the upstream boundary of the river section for flow interval i. and are the corresponding values at the downstream boundary. represents the net sediment transport (scouring or deposition) for flow interval i positive values indicate net deposition, and negative values indicate net scouring.

The total net sediment transport across all flow intervals is obtained by summing over all n (n = 2~50) intervals:

Here, represents the total net sediment transport for the river section under study, providing a comprehensive measure of scouring and deposition under all flow conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis of Hydrological Data

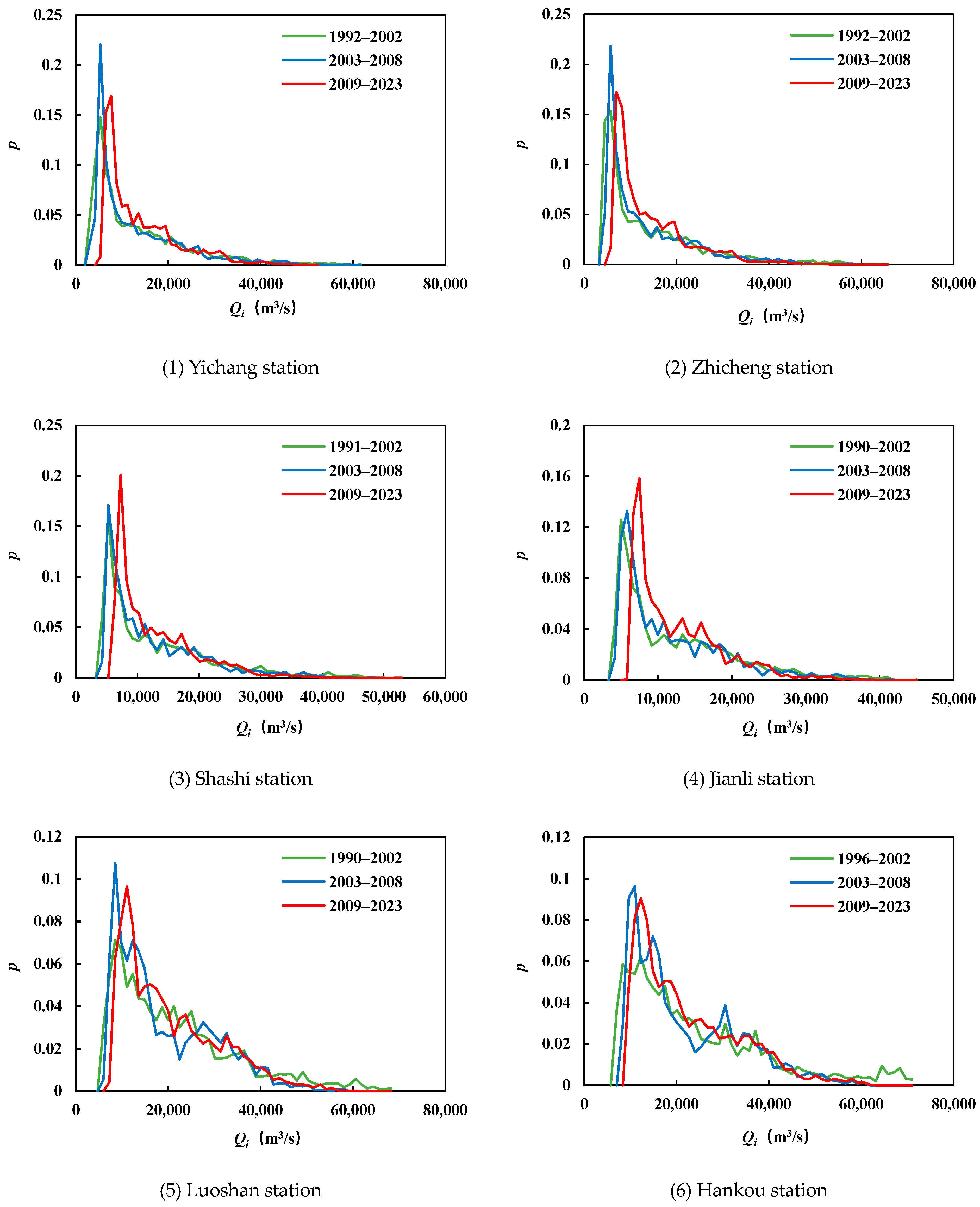

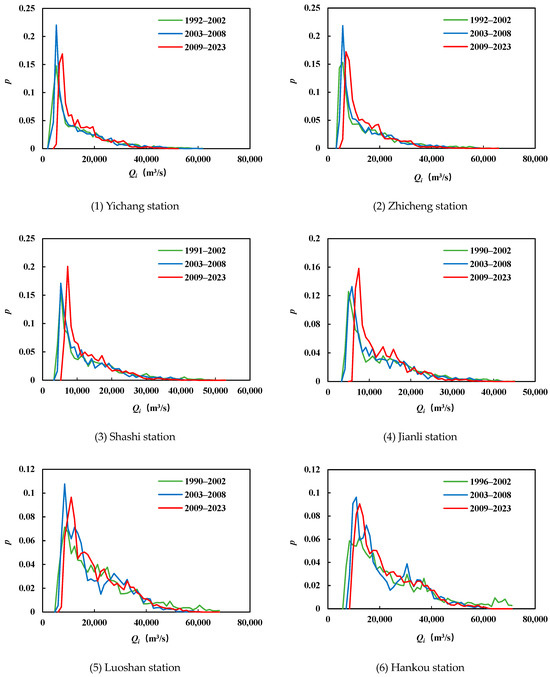

Through the above steps, the empirical frequency distribution of flow at each level was calculated. The empirical frequencies of flow at the eight stations over three different periods, calculated using 50 intervals, are shown in Figure 2. As illustrated in the figure, the flow ranges at the eight hydrological stations varied noticeably across time periods. Yichang and Zhicheng stations exhibited similar changes. From 1992 to 2002, the maximum flow frequency ranges were [5300, 6475) and [5723, 6975), respectively. From 2003 to 2008, the flow ranges remained the same as those before impoundment: [5300, 6475) and [5723, 6975), respectively. However, the frequencies increased by 7.3% at Yichang and 6.5% at Zhicheng. From 2009 to 2023, the maximum flow frequency ranges were [7650, 8825) and [6975, 8826), respectively, and the frequencies decreased 3.2% at Yichang and 4.7% at Zhicheng compared to the initial impoundment period (2003–2008). The changes at Shashi and Jianli stations are similar. From 1992 to 2002, the maximum flow frequency ranges were [5256, 6249) and [4968, 5802), respectively. From 2003 to 2008, the flow ranges were [5256, 6249) and [5802, 6636), respectively, compared with those before impoundment. However, the frequencies increased by 1.9% at Shashi and 0.8% at Jianli. From 2009 to 2023, the maximum flow frequency ranges were [7242, 8235) and [7470, 8304), respectively, and the frequencies increased 0.9% at Shashi and 2.9% at Jianli compared with the initial impoundment period (2003–2008). The maximum flow frequency intervals of Luoshan, Hankou, Jiujiang and Datong stations from 1990 to 2002 (1996 to 2002) were [8501, 9771), [12,275, 13,580), [9949, 11,312) and [10,754, 12,287), respectively. From 2003 to 2008, the maximum flow frequency intervals were [8501, 9771), [10,970, 12,275), [9949, 11,312) and [11,753, 12,637), respectively. The frequencies of these intervals increased 4.1% at Luoshan, 3.3% at Hankou, 3.9% at Jiujiang and 0.8% at Datong. From 2009 to 2023, the maximum flow frequency intervals were [11,040, 12,310), [12,275, 13,580), [12,675, 14,038) and [13,680, 15,164], and the frequencies decreased by 1.0% at Luoshan, 0.4% at Hankou, and 1.4% at Jiujiang compared with the initial impoundment period (2003–2008). The frequency distributions of Luoshan, Hankou, Jiujiang, and Datong stations during 2003–2008 exhibited two distinct peaks: one at low flow and another at high flow. By 2009–2023, the frequency distributions at these four stations had only the low-flow extreme points, and the high-flow extremes were more uniform.

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of flow at eight hydrological stations in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River at different periods.

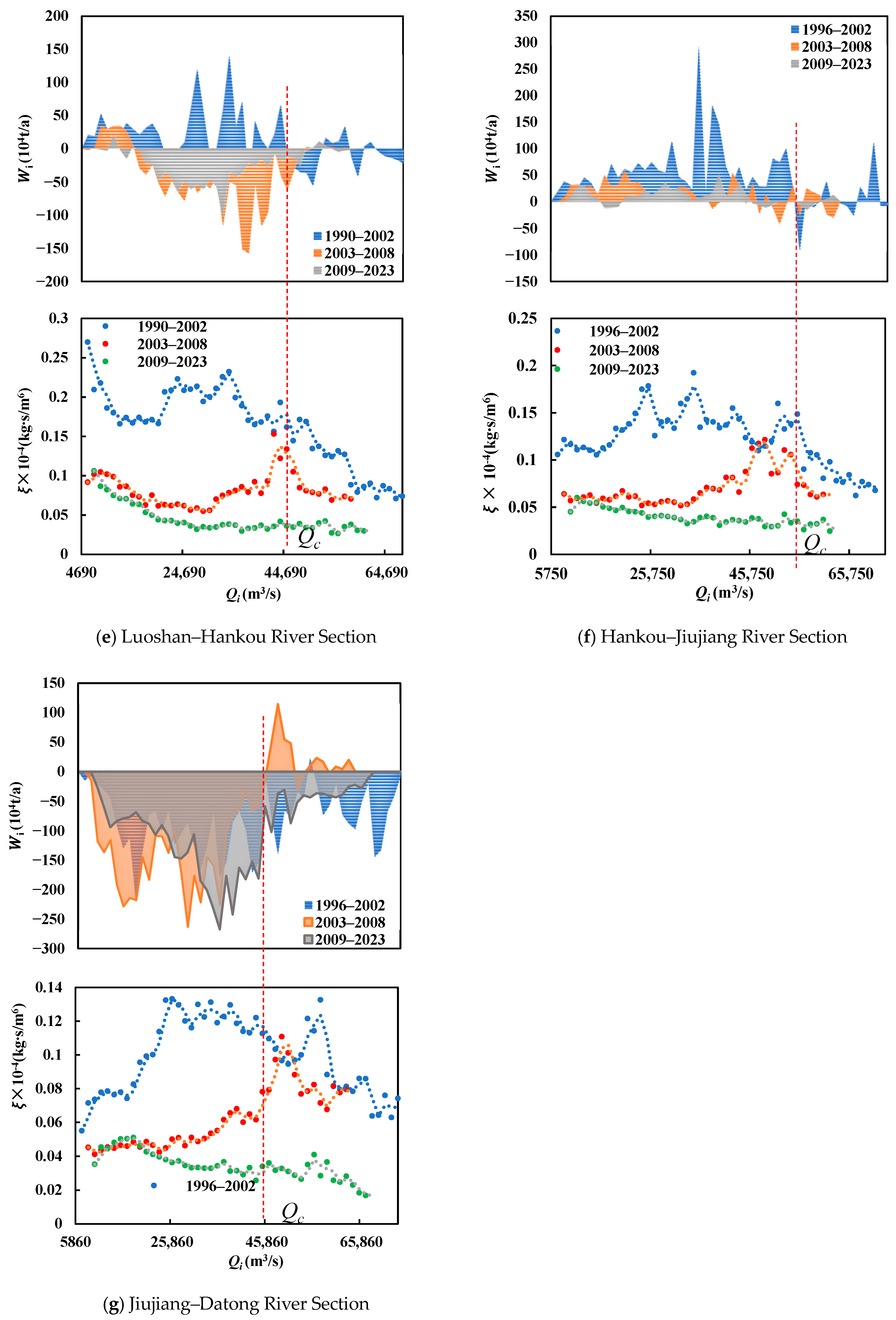

4.2. Coefficient of Determination Method

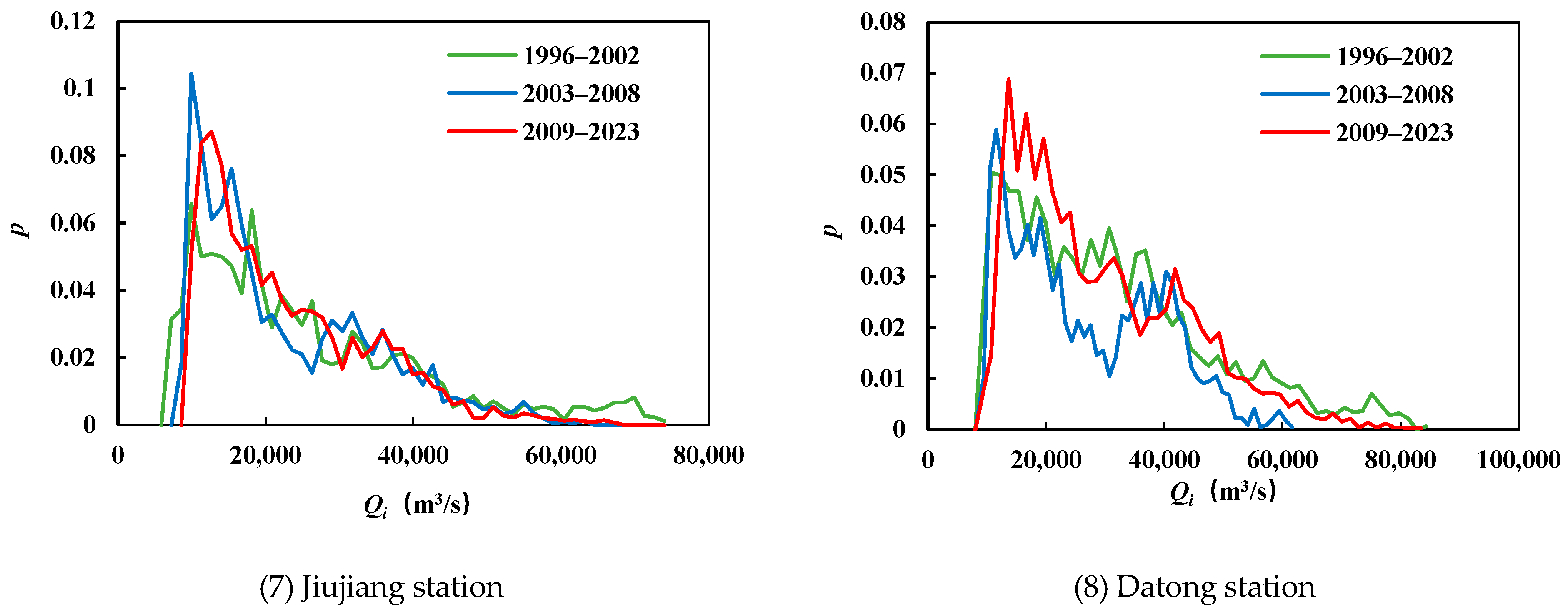

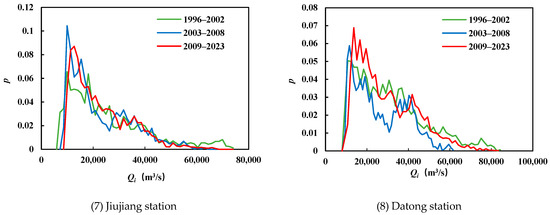

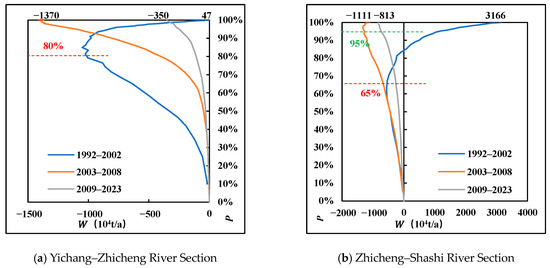

Rivers exhibit distinct sediment transport and channel evolution characteristics under varying flow regimes. Based on the above results, Figure 3 presents the relationship between the cumulative annual average scouring–silting volume in seven river sections of the middle and lower reaches and the sediment inflow coefficient at different flow levels. To further explore the thresholds of erosion–deposition and sediment transport, two key indicators were identified: the “critical scouring–silting threshold flow” and the “critical sediment transport index.” These thresholds were determined using a combined approach of numerical calculations and graphical analysis. Specifically, cumulative sediment transport was first calculated for different flow intervals, and the thresholds were then identified at inflection points of the erosion–deposition curves. Integrating these two approaches provided more robust and reproducible results.

Figure 3.

Annual average scouring and sedimentation () and sediment inflow coefficients () at three different periods and different flow rates in seven river sections downstream of the Three Gorges Dam. (The red dashed line represents the transition point between net scouring and net deposition).

The figure shows that scouring intensified in the Yichang–Zhicheng river section after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the scouring and silting threshold flow rate was approximately 20,000 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient increased with flow below the scouring and silting threshold flow rate, but remained stable at 0.42 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above it. After impoundment, except for several floods between 2003 and 2008, scouring occurred across nearly all flow levels, and no clear scouring–silting threshold could be identified. The sediment inflow coefficient generally increased with flow, and during several floods where siltation was the primary cause, the sediment inflow coefficient exceeded 0.20 × 10−4 kg·s/m6. Compared to pre-impoundment levels, the scouring flow rate has expanded to its fullest extent. The pre-impoundment critical scouring–silting threshold was 0.42 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

Scouring in the Zhicheng–Shashi river section intensified before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the scouring and silting threshold flow rate was approximately 15,000 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient increased with flow below the scouring and silting threshold flow rate, but remained stable at 0.35 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above it. After impoundment, scouring generally occurred from 2009 to 2023. The scouring and silting threshold flow rate was approximately 37,000 m3/s between 2003 and 2008. The sediment inflow coefficient showed an overall increasing trend with flow, and remained stable at 0.15 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above the scouring and silting threshold flow rate between 2003 and 2008. Relative to pre-impoundment, the critical scouring–silting indicator remained 0.35 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

Scouring in the Shashi–Jianli river section intensified before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the scour and siltation threshold flow rate was approximately 18,000 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient increased with flow below the scour and siltation threshold flow rate, but remained stable at 0.50 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above the scour and siltation threshold flow rate. After impoundment, the siltation threshold flow rate was approximately 37,000 m3/s from 2003 to 2008. The sediment inflow coefficient showed an overall increasing trend with flow, and remained stable at 0.15 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above the scour and siltation threshold flow rate from 2003 to 2008. Compared to before impoundment, the critical criterion for scouring and siltation before impoundment was 0.50 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

Scouring and siltation in the Jianli–Luoshan river section decreased both before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the flow rate separating scouring and siltation was approximately 17,500 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient increased with flow below the flow rate, but remained stable at 0.50 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 above the flow rate. After impoundment, the flow rate separating scouring and siltation ranged from approximately 22,000 to 28,000 m3/s from 2003 to 2008. The sediment inflow coefficient remained relatively stable below the flow rate from 2002 to 2008, but remained stable at 0.20 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 when sedimentation accumulated above the flow rate. Compared to before impoundment, the critical indicator for scouring and silting before impoundment was 0.50 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

The Luoshan–Hankou river section shifted from silting to scouring before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the scouring–silting threshold flow rate was approximately 45,000 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient remained stable at 0.16 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 below the scouring–silting threshold flow rate. Above this threshold flow rate, the sediment inflow coefficient decreased, leading to scouring. After impoundment, the overall pattern from 2009 to 2023 was scouring, with the scouring–silting threshold flow rate dropping to 15,000 m3/s. The sediment inflow coefficient remained relatively stable below the scouring–silting threshold flow rate from 2003 to 2008, and remained stable at 0.10 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 when silting occurred above this threshold flow rate. Compared to before impoundment, the critical indicator for siltation-to-scour transition was 0.16 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

Sedimentation in the Hankou–Jiujiang river section decreased before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, the scouring–silting flow rate was approximately 54,000 m3/s, and the sediment inflow coefficient remained stable at 0.11 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 below the scouring–silting flow rate. Above the scouring–silting flow rate, the sediment inflow coefficient decreased, leading to scouring. After impoundment, from 2009 to 2023, sedimentation generally occurred, with no significant scouring–silting flow rate and no clear pattern in the sediment inflow coefficient. Compared to before impoundment, the silting flow rate decreased, and the critical indicator for siltation-to-scour transition was 0.11 × 10−4 kg·s/m6 before impoundment.

The Jiujiang–Datong river section was dominated by scouring both before and after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Before impoundment, this river section exhibited scouring at all flow levels, with no discernible trend in scouring intensity across flow levels. The sediment inflow coefficient ranged from 0.06 to 0.14 × 10−4 kg·s/m6, and there was no clear scouring–silting threshold. After impoundment, scouring intensity increased at flows below 35,000 m3/s between 2003 and 2008. From 2009 to 2023, flows with significant scouring were concentrated between 30,000 and 42,000 m3/s, with the scouring–silting threshold at approximately 45,000 m3/s. Furthermore, scouring was observed from 2003 to 2008 when the sediment inflow coefficient fell below 0.08 × 10−4 kg·s/m6. Compared to before impoundment, the critical criterion for scouring–silting in 2003–2008 was 0.08 × 10−4 kg·s/m6. These changes indicate that the operation of the Three Gorges Reservoir has significantly altered the scouring and silting characteristics of the Jiujiang–Datong river section, intensifying scouring under low-flow conditions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Flow Changes Affected by the Three Gorges Reservoir

Before the impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir (1990–2002), extreme high and low flow events occurred frequently, resulting in pronounced river flow fluctuations and a distinct seasonal pattern [22,25]. However, following the commissioning of the reservoir, the flow distribution has undergone a significant transformation. The frequency of extreme flow events has markedly declined: extreme high flows decreased substantially, attenuating flood peaks and lowering flood risk, while extreme low flows also diminished, improving dry-season water availability and easing supply stress. These changes have led to a substantial reduction in flow variability, contributing to more stable hydrological conditions. At the same time, the frequency of small to medium flow events has increased noticeably. Reservoir regulation has moderated the river’s discharge regime, making moderate and normal flows more prevalent. Such stabilized flow conditions are favorable for sediment transport, improving both efficiency and predictability.

Overall, the flow frequency distribution has become more uniform and smoother. The reduction in extreme events combined with the increase in medium flows has resulted in more gradual hydrological fluctuations, reducing abrupt shifts and promoting a more stable fluvial environment.

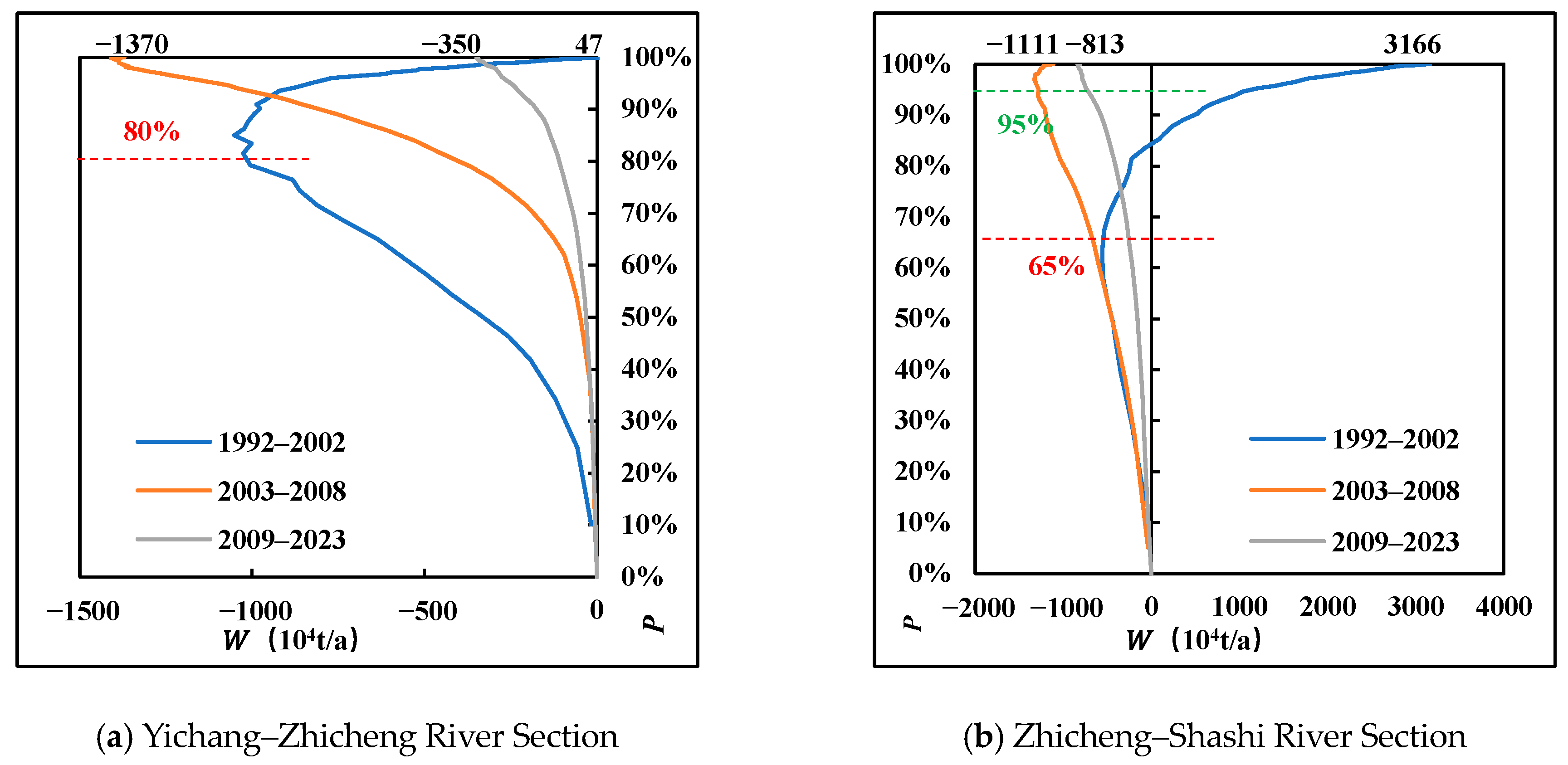

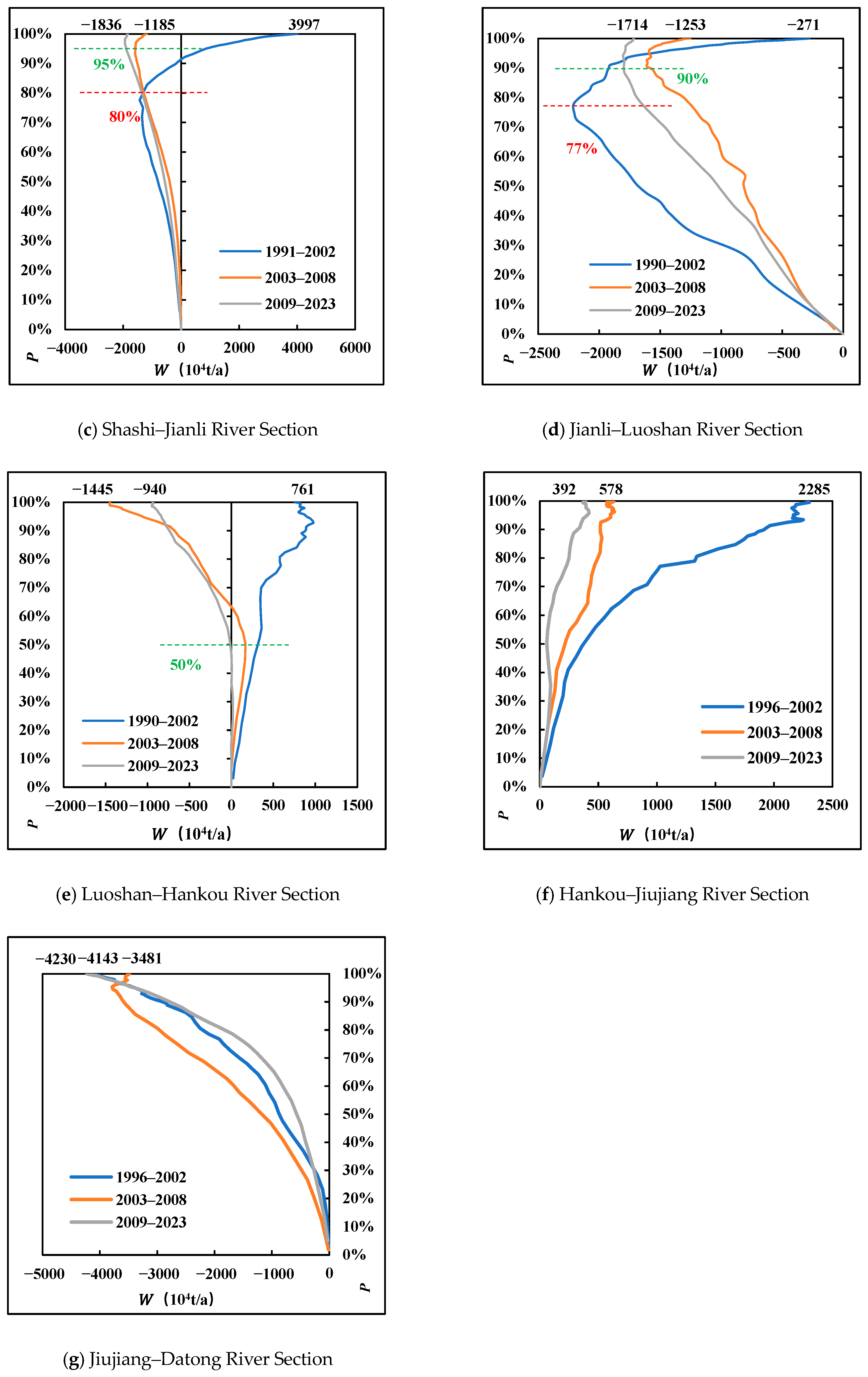

5.2. Relationship Between Cumulative Flow Frequency and Annual Net Scouring/Silting

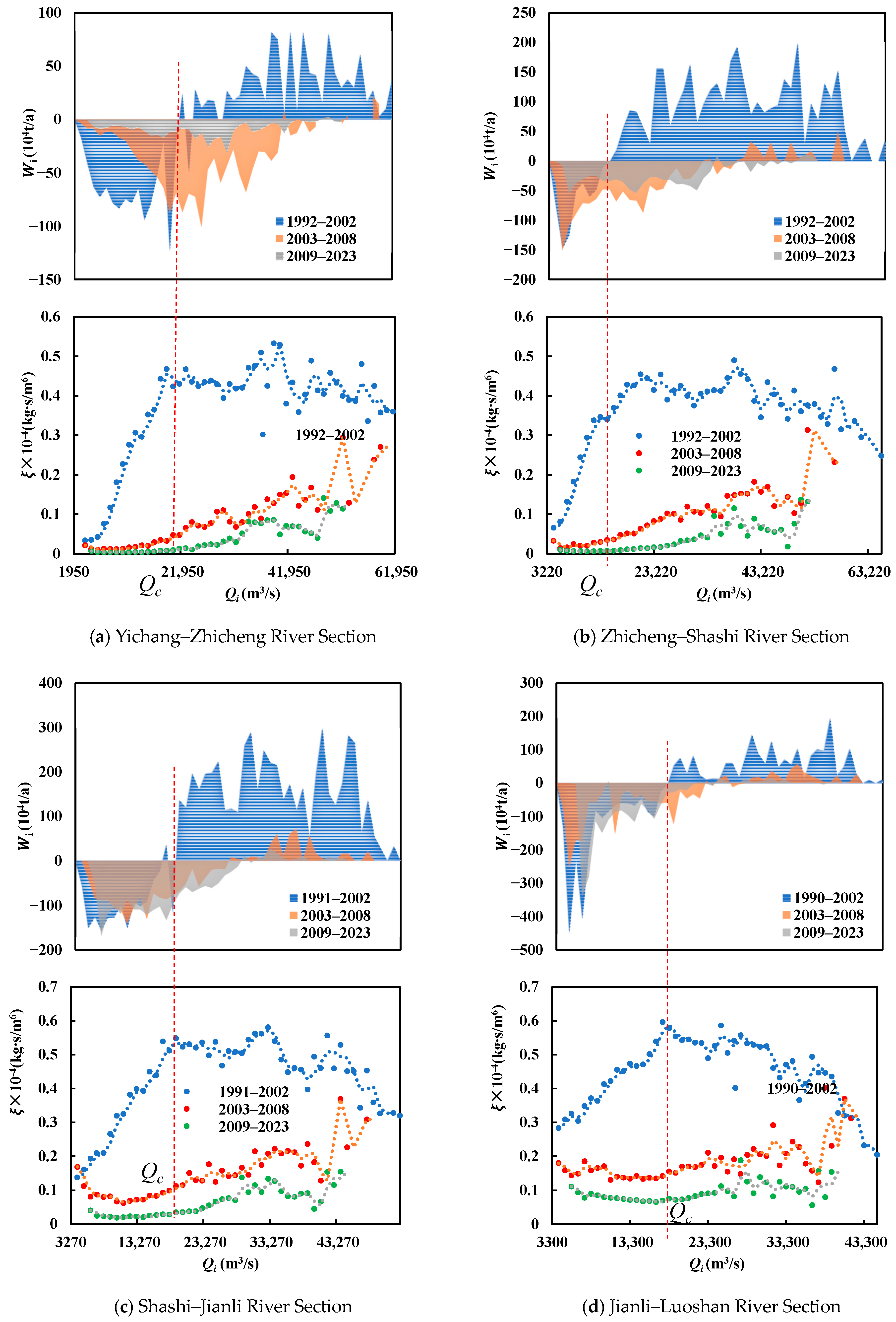

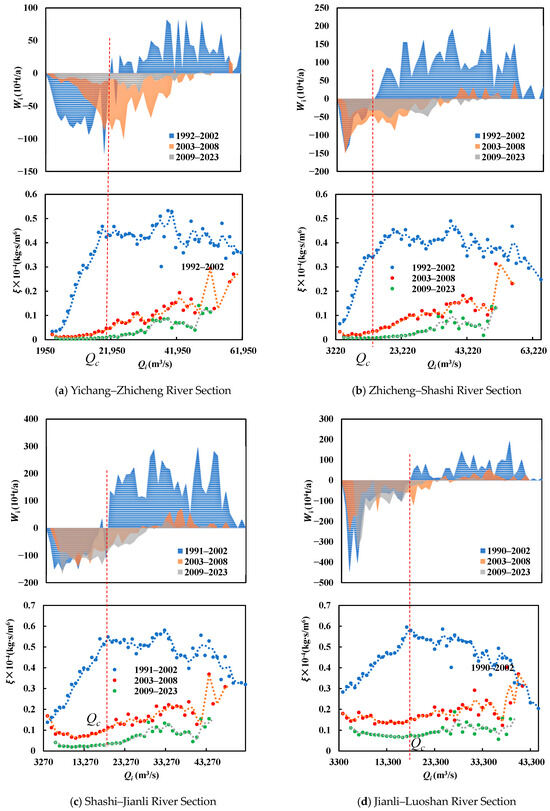

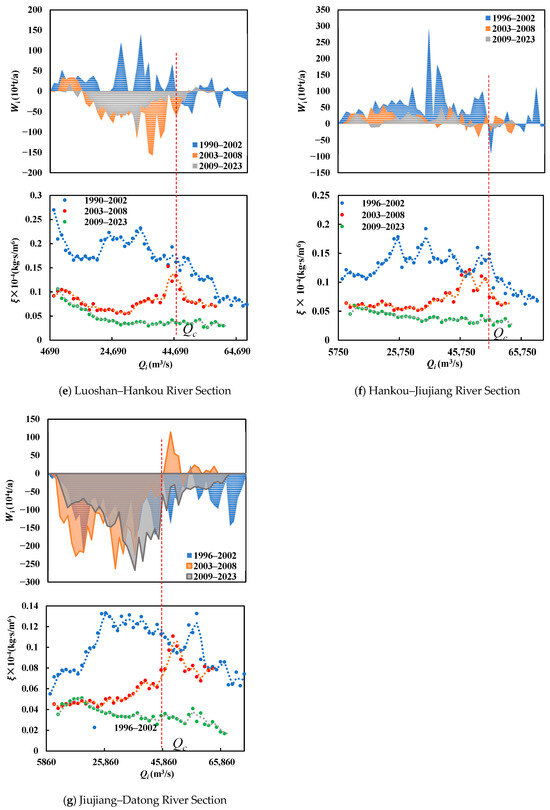

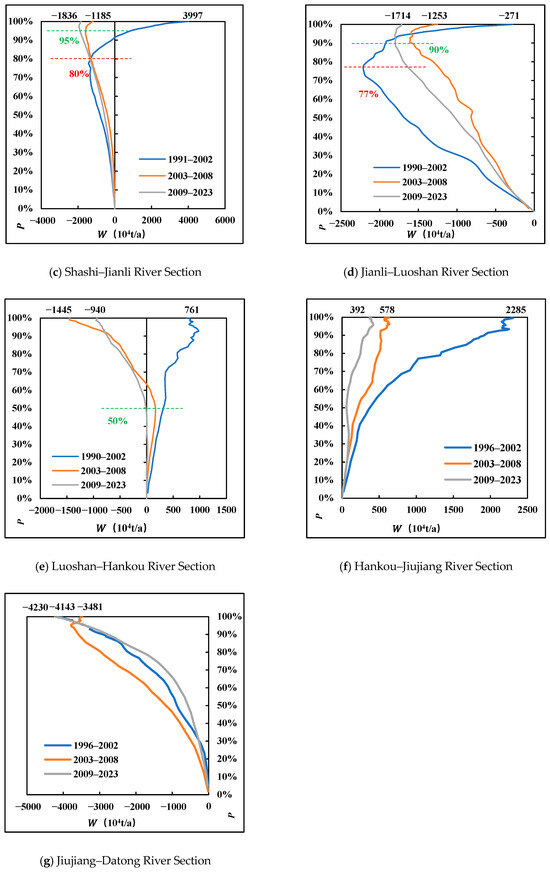

Based on the above calculations, a quantitative relationship was established between cumulative flow frequency—from minimum to maximum discharge—and the annual average net scouring or silting for each of the seven river sections downstream of the Three Gorges Dam (Figure 4). The results indicate that each section exhibits distinct sediment response patterns across different regulation periods.

Figure 4.

Relationship between cumulative frequency and annual average scouring and silting volume. (The red dashed lines indicate the transition from net scouring to net deposition, and the green dashed lines indicate the transition from net deposition to net scouring).

In the Yichang–Zhicheng river section, under natural conditions prior to impoundment (1992–2002), scouring occurred when cumulative flow frequency was below 80%, whereas silting dominated beyond this threshold, yielding an overall near-equilibrium sediment regime with a net annual deposition of approximately 4.7 × 105 t/a. During the early impoundment period (2003–2008) and the post-175 m period (2009–2023), however, the river section exhibited a clear trend of increasing scouring, with net annual scouring reaching 13.70 × 106 t/a in the early stage. In the Zhicheng–Shashi river section, under natural conditions (1992–2002), scouring occurred when flow frequency was below 65%, transitioning to silting above this threshold, with a final net silting of 31.66 × 106 t/a. In 2003–2008, the critical flow frequency for scouring shifted to 95%, and net scouring reached 11.11 × 106 t/a. In the 2009–2023 period, scouring continued to increase, reaching 8.13 × 106 t/a. For the Shashi–Jianli river section, from 1991 to 2002, scouring occurred below the 80% cumulative frequency, followed by silting beyond that point, with a final net silting of 39.97 × 106 t/a. During 2003–2008, the critical flow frequency for scouring increased to 95%, with scouring reaching 18.36 × 106 t/a. From 2009 to 2023, scouring further intensified, reaching 11.85 × 106 t/a. In the Jianli–Luoshan river section, during 1990–2002, scouring occurred below a cumulative flow frequency of 77%, transitioning to silting beyond that threshold. The river section ultimately showed net silting of 39.97 × 106 t/a. In the early impoundment period, the critical scouring frequency increased to 90%, with annual scouring reaching 17.14 × 106 t/a, while the 2009–2023 period showed further scouring, reaching 12.53 × 106 t/a.

The Luoshan–Hankou river section exhibited consistent silting throughout the entire flow frequency spectrum during the natural condition period (1990–2002), with a net annual silting of 7.61 × 106 t/a. In 2003–2008, scouring became dominant when flow frequency exceeded 50%, with net scouring reaching 14.45 × 106 t/a. During 2009–2023, scouring continued, though at a reduced rate, with net scouring of 9.40 × 106 t/a. In the Hankou–Jiujiang river section, silting was observed across all periods—natural condition (1990–2002), early impoundment (2003–2008), and post-175 m impoundment (2009–2023). However, the magnitude of silting continuously decreased, while scouring gradually increased. The annual net silting decreased from 22.85 × 106 t/a to 3.92 × 106 t/a over time. Finally, the Jiujiang–Datong river section exhibited a consistent increase in scouring across all three periods. From the pre-impoundment phase through to the post-175 m period, the riverbed continued to experience intensified scouring, indicating a persistent sediment-deficient regime.

Overall, the changes in sediment dynamics across the seven river sections can be grouped into two categories (Figure 4). In near-dam river sections (Yichang–Zhicheng, Zhicheng–Shashi, Shashi–Jianli, and Jianli–Luoshan), sediment dynamics prior to impoundment were strongly flow-dependent: moderate floods (65–80% frequency) induced scouring by providing sufficient transport capacity, whereas extreme floods produced net deposition due to excess sediment supply. Following impoundment, however, scouring became prevalent across virtually all flow levels, with only minor deposition during rare floods exceeding 90% frequency—suggesting that catastrophic floods can temporarily overwhelm transport capacity and induce localized silting.

In contrast, the far-dam river sections downstream of Chenglingji (Luoshan–Hankou, Hankou–Jiujiang, and Jiujiang–Datong) displayed a different response. Before impoundment, the Luoshan–Hankou and Hankou–Jiujiang sections were dominated by deposition, whereas scouring prevailed in the Jiujiang–Datong section. After impoundment, however, Luoshan–Hankou shifted from deposition to scouring, and the intensity of silting in the Hankou–Jiujiang section was markedly reduced. Although some deposition still occurs, the overall level has been substantially weakened. Together, these shifts highlight the critical role of reservoir operation in redistributing sediment regimes and restructuring longitudinal scouring–silting dynamics along the middle and lower Yangtze River.

5.3. Sediment Scouring and Silting Reconstruction and Threshold Drift Caused by Three Gorges Reservoir Operation

The operation of the Three Gorges Reservoir has markedly reshaped downstream scouring–silting dynamics, exhibiting a distinct longitudinal gradient (Table 2). The critical discharge () defines the hydraulic threshold for regime transition: when the actual discharge , the sediment transport capacity exceeds sediment supply, resulting in channel scouring; conversely, when , sediment input surpasses transport capacity, leading to channel silting. Similarly, the critical sediment coefficient (where , and is the suspended sediment concentration) characterizes the sediment transport equilibrium. When the actual sediment coefficient , sediment supply is insufficient and scouring occurs; when , sediment surplus results in silting [42,43,44].

Table 2.

Summary of sediment transport characteristics at different flow levels in each river section.

Scouring effects propagate progressively downstream, restructuring the longitudinal pattern of sediment dynamics. In the Yichang–Zhicheng reach, the pre-impoundment period displayed a bimodal scouring–silting regime with a threshold of ~20,000 m3/s, which shifted to scouring dominance at all flows post-impoundment. The Zhicheng–Shashi river section underwent a similar transition from a bimodal regime at 15,000 m3/s to pervasive scouring. In Shashi–Jianli, the threshold increased from 18,000 m3/s (pre-impoundment) to 22,000–32,000 m3/s after regulation. In Jianli–Luoshan river section, a threshold of 17,500 m3/s shifted to 22,000–28,000 m3/s, evolving into scouring dominance across all flows in the post-175 m period (2009–2023). By contrast, in Luoshan–Hankou river section, the threshold dropped from 45,000 m3/s to 15,000 m3/s, indicating that scouring now occurs under lower flows. The Hankou–Jiujiang river section remained silting-dominated, though silting intensity declined markedly after impoundment. In the Jiujiang–Datong river section, scouring persisted throughout all stages, reflecting a consistently sediment-deficient regime. This progressive expansion of scour zones illustrates the downstream transmission of the “clear-water effect,” with scouring intensity negatively correlated with distance from the dam [45,46].

Reservoir regulation has also induced systematic reorganization of critical thresholds. In Zhicheng–Shashi river section, increased sharply from 15,000 to 37,000 m3/s (a 146% rise), whereas in Luoshan–Hankou river section it decreased from 45,000 to 15,000 m3/s (a 67% reduction). At the same time, declined across all river sections by 52–70%. For instance, in Shashi–Jianli, dropped from 0.50 × 10−4 to 0.15 × 10−4 kg·s/m6, while in Jianli–Luoshan river section it decreased from 0.50 × 10−4 to 0.20 × 10−4 kg·s/m6. In Hankou–Jiujiang river section, the scouring–silting threshold became indistinct after impoundment, indicating a collapse of the silting maintenance mechanism when falls below 0.11 × 10−4 kg·s/m6.

Overall, reservoir operation has driven a fundamental shift in scouring–silting dynamics. Before impoundment, thresholds of discharge and sediment coefficient clearly defined sediment regimes in near-dam river sections (Yichang–Zhicheng river section to Jianli–Luoshan river section). After impoundment, however, the clear-water effect introduced strong positive feedback between flow and scouring, rendering single-parameter thresholds inadequate. In this context, bed resistance emerged as an additional feedback factor influencing channel adjustment. In far-dam river sections (Luoshan–Hankou river section to Jiujiang–Datong river section), although critical discharge still shifted, changes in were less pronounced than upstream, suggesting attenuation of scouring propagation due to buffering from major tributaries and large lakes, such as Dongting and Poyang, which moderate sediment delivery and dissipate flow energy [47,48].

5.4. Applicability and Limitations of Threshold Analysis

The present findings are consistent with earlier studies on the Yellow River, where scouring–silting thresholds were identified using sediment inflow coefficients and related indicators. These studies demonstrated that critical values can effectively differentiate depositional from erosional regimes under varying flow conditions [39,42]. Building on this foundation, the present work extends threshold analysis to multiple river sections of the Yangtze River, revealing a systematic spatial and temporal reorganization of thresholds under regulation by the Three Gorges Reservoir. This broader perspective emphasizes marked contrasts between near-dam and far-dam river sections, which were not captured in previous single-station investigations.

The applicability of this threshold-based framework is strongly influenced by the degree of river regulation [41]. In relatively unregulated alluvial rivers, threshold transitions are typically well defined and primarily governed by natural variations in flow and sediment supply. As demonstrated in the Yellow River and the Amur River, the use of flow thresholds and sediment inflow coefficients can effectively characterize sediment transport dynamics under different hydrological regimes [40,41,49]. In contrast, in heavily engineered systems such as the Yangtze River, threshold identification is more complex, as external interventions—including dam operations, water diversion projects, and channelization—often exert dominant control over sediment transport processes [6,7]. In such contexts, critical thresholds should be interpreted with caution, as they may only partially reflect the underlying mechanisms of channel adjustment.

Several limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. Reliance on a single indicator, such as critical discharge or sediment coefficient, cannot fully capture the complexity of scouring–silting transitions, particularly in human-regulated systems where multiple drivers interact [41]. Future research should therefore integrate threshold analysis with complementary approaches that account for sediment supply reduction, tributary inputs, and localized engineering modifications, thereby providing a more holistic representation of the multifactorial processes governing riverbed adjustment.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the operation of the Three Gorges Reservoir has fundamentally restructured the hydrological and sediment regimes of the middle and lower Yangtze River. The most prominent transformation is the stabilization of the flow regime, characterized by a sharp decline in the frequency of extreme high- and low-flow events and an increased dominance of moderate flows. This shift has reduced seasonal variability and enhanced overall flow stability. At the same time, reservoir impoundment has driven the progressive downstream expansion of scouring zones, with several river sections—particularly those proximal to the dam—transitioning from balanced or silting-dominated states to scouring-dominated conditions.

The thresholds controlling scouring and silting have also undergone systematic spatial reorganization. In near-dam river sections, critical discharge values increased substantially (e.g., from 15,000 m3/s to 37,000 m3/s in the Zhicheng–Shashi river section), whereas in far-dam river sections they decreased (e.g., from 45,000 m3/s to 15,000 m3/s in the Luoshan–Hankou river section). Across all sections, critical sediment coefficients declined, reflecting a weakened balance between sediment supply and transport. Furthermore, the dominant adjustment mechanism has shifted from a threshold-based sediment balance model to a feedback-driven clearwater model, in which sediment supply reduction promotes scouring while increased bed resistance suppresses it.

The analysis also reveals systematic threshold shifts in both critical flow () and critical sediment coefficient (), displaying pronounced spatial gradients. These dynamics highlight strong spatial heterogeneity as geomorphic responses attenuate downstream owing to the buffering effects of major tributaries and lake inflows, resulting in less distinct thresholds in far-dam river sections. Overall, the Three Gorges Dam has triggered a cascading sequence of geomorphic adjustments with profound implications for channel morphology, flood regulation, navigation safety, and ecological sustainability. These findings emphasize the necessity of river section-specific and adaptive sediment management strategies in large, human-regulated alluvial rivers.

Author Contributions

M.S.: Writing—original draft, and Methodology; C.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Administration; S.G.: Formal Analysis, and Conceptualization; H.S.: Writing—review and editing; Y.L.: Formal Analysis, and Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Project of China Three Gorges Corporation (Grant No. 0704217).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Shuai Guo is employed by China Three Gorges Corporation and Yuchen Li is employed by China Yangtze Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Church, M. Bed Material Transport and the Morphology of Alluvial River Channels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2006, 34, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E. Rivers in the Anthropocene: The Influence of Human Activities on River Morphology and Processes. Geomorphology 2020, 366, 107569. [Google Scholar]

- Engelund, F.; Anker, H. Monograph on Sediment Transport in Alluvial Streams; Teknisk Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, L.C. Unified View of Sediment Transport by Currents and Waves. I: Initiation of Motion, Bed Roughness, and Bed-Load Transport. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Milliman, J.D. Geology, Geography, and Humans Battle for Dominance over the Delivery of Fluvial Sediment to the Coastal Ocean. J. Geol. 2007, 115, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, H.; Li, Y. Temporal and Spatial Variability of Sediment Transport in the Yangtze River: Influence of Climate Change and Human Activities. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Spatiotemporal Variability of Sediment Transport in the Yangtze River under Human Interventions. Water 2021, 13, 805. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J. Anthropogenic Stresses on the World’s Big Rivers. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; Meybeck, M.; Fekete, B.; Sharma, K.; Green, P.; Syvitski, J.P.M. Anthropogenic Sediment Retention: Major Global Impact from Registered River Impoundments. Glob. Planet. Change 2003, 39, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Z.; Dai, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, H. Sediment Transport and Budget Change of the Yangtze River During the Last 50 Years in Response to Human Activities. Geomorphology 2006, 108, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Milliman, J.D. Seasonal Variations of Sediment Discharge from the Yangtze River Before and After Impoundment of the Three Gorges Dam. Geomorphology 2009, 104, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Lu, X.X.; Yang, S.; Liu, C. Sediment Load Change in the Yangtze River (Changjiang): A Review. Geomorphology 2014, 215, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, C.; Xu, J. Effects of Three Gorges Dam Operation on Sediment Transport and Channel Morphology in the Middle Yangtze River. Catena 2018, 165, 470–482. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Tang, Q. Impact of Reservoir Regulation on Downstream Sediment Load and Channel Evolution in the Middle Yangtze River. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1109. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Dai, S.; Yang, S. Impact of the Three Gorges Dam on Sediment Regime and Fluvial Processes in the Middle and Lower Yangtze River. Geomorphology 2021, 375, 107552. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Feng, X.; Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Wan, K.; Yin, B. Application of Deep Learning in Predicting Suspended Sediment Concentration: A Case Study in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanicolaou, A.T.N.; Elhakeem, M.; Krallis, G.; Prakash, S.; Edinger, J. Sediment Transport Modeling Review—Current and Future Developments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 134, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roushangar, K.; Shahnazi, S.; Azamathulla, H.M. Sediment Transport Modeling through Machine Learning Methods: Review of Current Challenges and Strategies. In River Dynamics and Flood Hazards; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Xia, J. Water problems and hydrological research in the Yellow River and the Huai and Hai River basins of China. Hydrol. Process. 2004, 18, 2197–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, D.E.; Fang, D. Recent trends in the suspended sediment loads of the world’s rivers. Glob. Planet. Change 2003, 39, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tan, G.; Lyu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Shu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G. Operating Effects of the Three Gorges Reservoir on the Riverbed Stability in the Wuhan Reach of the Yangtze River. Water 2021, 13, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Han, J.; Yang, Y. Influence of Large Reservoir Operation on Water-Levels and Flows in Reaches below Dam: Case Study of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Effectiveness of River Training Projects in Controlling Shoal Erosion: A Case Study of the Middle Yangtze River. Hydrology 2025, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Wei, W.; Ge, Z.; Lou, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, Z. Immediately Downstream Effects of the Three Gorges Dam on Channel Sandbars Morphodynamics Between Yichang–Chenglingji Reach of the Changjiang River, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 629–646. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, J.; Fan, Y. Channel Evolution under Changing Hydrological Regimes in Anabranching Reaches Downstream of the Three Gorges Dam. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 12, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.F.; Liu, G.R.; Pi, J.G.; Chen, G.J.; Li, C.A. On the River–Lake Relationship of the Middle Yangtze Reaches. Geomorphology 2007, 85, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Zhang, M.J.; Sun, Z.H.; Han, J.Q.; Wang, J.J. The Relationship between Water Level Change and River Channel Geometry Adjustment Downstream of the Three Gorges Dam. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 1975–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Relationship between Waterway Depth and Low-Flow Water Levels in Reaches Below the Three Gorges Dam. J. Waterw. Port. Coast. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 145, 04018032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Impact of the Operation of a Large-Scale Reservoir on Downstream River Channel Geomorphic Adjustments: A Case Study of the Three Gorges. River Res. Appl. 2018, 34, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.J.; Jiang, J.H.; Yang, G.S.; Lu, X.X. Should the Three Gorges Dam Be Blamed for the Extremely Low Water Levels in the Middle–Lower Yangtze River? Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.B.; Yang, T.; Du, M.Y.; Sun, F.B.; Liu, C.M. Impact of the Three Gorges Dam on the Hydrology Mechanism of Typical Hydrologic Stations in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. Ecol. Environ. Monit. TG 2018, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced Lakebed Sediment Erosion in Dongting Lake Induced by the Operation of the Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Changes in Hydrological Interactions of the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake in China during 1957–2008. J. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 66, 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Impact of Upstream Reservoirs on Geomorphic Evolution in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 2022, 48, 582–595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.T.; Deng, J.Y.; Yang, Y.P. Preliminary Analysis of Changes in Hydraulic Elements of Dongting Lake in the Storage Period of the Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2014, 33, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Jiao, X.; Guo, W.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, B. Synergistic Evolution and Attribution Analysis of Water–Sediment in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101626. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.L.; Xu, C.Y.; Xu, Y.P.; Jiang, T. Observed Trends of Annual Maximum Water Level and Streamflow during the Past 130 Years in the Yangtze River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2006, 324, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Chang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, T. Influence of Three Gorges Dam on Downstream Low Flow. Water 2019, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Influence of the Three Gorges Dam on the Transport and Sorting of Coarse and Fine Sediments Downstream of the Dam. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Pan, S.; Chen, S. Impact of River Discharge on Hydrodynamics and Sedimentary Processes at Yellow River Delta. Mar. Geol. 2020, 425, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xia, J.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. Effect of Altered Flow Regime on Bankfull Area of the Lower Yellow River, China. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 1585–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.J. Influence of the Three Gorges Dam on Downstream Delivery of Sediment and Its Environmental Implications, Yangtze River. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Fagherazzi, S.; Zheng, S.; Tan, G.; Shu, C. Enhanced Hysteresis of Suspended Sediment Transport in Response to Upstream Damming: An Example of the Middle Yangtze River Downstream of the Three Gorges Dam. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 2020, 45, 1846–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, M.; Chen, J.; Ge, X. Variation in Sediment Delivery Ratios of Grouped Sediment in a Braided Reach Owing to Channel Adjustments. Environ. Fluid. Mech. 2024, 24, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, Z.; Yu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Sediment Rating Parameters and Their Implications: Yangtze River, China. Geomorphology 2007, 85, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Yang, S.L.; Xu, K.H.; Milliman, J.D.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.Y. Human Impacts on Sediment in the Yangtze River: A Review and New Perspectives. Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 162, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.Y.; Fan, S.Y.; Pang, C.N.; Liu, C.C. Adjustment of Regulation and Storage Capacity of Lakes in the Middle Yangtze River Basin during Impoundment of the Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2018, 35, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.Y.; Hong, Y.; Hardy, J.; Sun, Z.H. Examining the Influence of River–Lake Interaction on the Drought and Water Resources in the Poyang Lake Basin. J. Hydrol. 2015, 522, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonov, E.A.; Dahmer, T.D. (Eds.) Amur-Heilong River Basin Reader; Ecosystems Ltd.: Hong Kong, China, 2008; 426p. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).