Abstract

The paper focuses on exploring ways to achieve sustainability in the manufacturing process through targeted optimization and ergonomic improvements of the work environment. The introductory section emphasizes the importance of sustainability from the perspectives of worker well-being, occupational safety, and efficient resource utilization. The paper presents a digital approach to workstation design with an emphasis on sustainability, which includes the creation of a 3D model of the assembly station using SolidWorks (v.2017) and Jack software (v.8.3), where the work movements of a virtual mannequin with realistic parameters are simulated. The analytical section is dedicated to evaluating workstation ergonomics using the RULA (Rapid Upper Limb Assessment), SSP (Static Strength Prediction), OWAS (Ovako Working Posture Analysis), and Lower Back Analysis methods, with the aim of identifying operations that reduce the sustainability of the work process due to excessive physical strain. Badly designed operations have a negative impact on sustainability in the meaning of physical workload strain (social dimension), low effectivity and quality (economic dimension), and higher resource (material, energy, transport, etc.) usage (environmental dimension). All these dimensions can be measured and expressed by number, but this paper focuses on workload only. Based on the results, specific measures were proposed with a focus on sustainability—raising the working height of pallets, optimizing the positioning of tools, and adjusting work movements. Repeated analyses after the implementation of these changes confirmed not only a reduction in physical strain and increased safety but also the enhancement of the sustainability of the working environment and processes. The results of the article clearly demonstrate that digital simulation and ergonomic design, oriented toward sustainability, are of crucial importance for the long-term efficiency and sustainable development of manufacturing organizations. The novelty of the work is in contribution to empirical validation on the role of digital twins, virtual ergonomics, and human factors in Industry 5.0 contexts, where the synergy between technological efficiency and human-centric sustainability is increasingly emphasized. The proposed approach represents a practical model for further initiatives aimed at improving the sustainability of assembly workstations.

1. Introduction

Sustainable efficiency in manufacturing is today a key requirement of industry, and its achievement is closely linked to the optimization of working conditions for employees [1,2]. An ergonomically designed workplace not only increases productivity and work quality but also contributes to the long-term sustainability of the work process [3,4]. The article focuses on the use of digital tools for the modeling and analysis of assembly workstations to achieve maximum efficiency without negative impacts on worker health and well-being.

Digital modeling of the workstation in Tecnomatix Jack software enabled detailed simulation of work movements and assembly operations. In this way, it was possible, already in the design phase, to identify areas where the musculoskeletal system of the worker is excessively loaded or where inefficient movements occur. Such digital simulation brings a direct benefit to sustainability by minimizing the need for time- and material-intensive physical prototypes and repeated workstation adjustments.

A significant component of sustainable efficiency is the identification of ergonomic risks that could lead to health complications or reduced productivity. The article employs four ergonomic analyses (RULA, SSP, OWAS, and Lower Back Analysis), which enabled an objective assessment of worker load during various operations. The results of these analyses showed that certain movements, such as lifting parts from low-positioned pallets or handling hard-to-reach tools, represented a significant risk to the worker’s musculoskeletal system.

The adopted workstation optimization measures were directly aimed at strengthening sustainability—by increasing the pallet working height, repositioning tools to ergonomic locations, modifying handling of clamps, and using an industrial mat to reduce foot fatigue. These adjustments yielded tangible results not only in the form of reduced physical strain, but also in enhancing the long-term sustainability of the work process by reducing the risk of worker injuries and health problems.

Sustainability in this context is also reflected in increased workstation longevity and reduced need for frequent reconfigurations. An optimized workstation is more flexible, allows quicker adaptation to process changes, and its setup is easier to adjust to different worker body types, which increases overall efficiency even with employee turnover.

From the perspective of production management, investment in ergonomic measures is an investment in sustainability—it reduces the number of occupational injuries, absenteeism, and turnover, which ultimately saves costs and stabilizes production capacities. Furthermore, employees working in favorable ergonomic conditions achieve higher satisfaction, lower fatigue, and consistently high performance, thereby ensuring the organization’s long-term competitiveness.

The significance of digital simulation and ergonomic improvements thus far exceeds the scope of a single workstation. It is a tool that supports continuous improvement, the dissemination of best practices, and the implementation of sustainability principles throughout the entire organization. This philosophy aligns with modern industry trends, which emphasize the integration of technological innovation, the human factor, and environmental responsibility.

In summary, ergonomic optimization of assembly workstations is an integral part of the strategy for sustainable efficiency in manufacturing. The case study presented in the article confirms that digital modeling, objective workload analysis, and targeted workplace modifications lead to measurable benefits for both employees and employers and become a significant tool for the sustainable development of industrial production.

Factors influencing the production and assembly process are derived from overall changes in the product development and manufacturing process up to its market launch. Successful product development includes creating a product of the highest possible quality at the lowest possible cost and in the shortest possible time. Changed technical, economic, and social conditions require radical changes in product development strategies. One of the key factors influencing product success is the so-called “time to market,” which is the period between the decision to start producing a product and its market launch. The need to meet product development requirements motivate the creation and application of new product development strategies. At the same time, the need for innovative changes and the acceleration of new product development processes are today’s leading trends.

The recent literature clearly highlights the synergistic interconnection of sustainability, digital technologies, and ergonomics in modern manufacturing systems [5,6]. According to Industry 4.0 and digital transformation are opening new opportunities for enhancing the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of manufacturing enterprises, with workplace optimization being key to reducing employee strain and overall resource consumption [7,8]. As demonstrated by Adiga [9] digital simulations of workplaces fundamentally accelerate the testing and improvement of manufacturing processes, with an emphasis on efficiency, quality, and sustainability

Systematic reviews (e.g., Gualtieri et al. [10]) analyze the sustainability of Industry 4.0 and emphasize the importance of a comprehensive approach, in which digitalization, automation, and ergonomics form an inseparable whole. Gajšek et al. [11] present the integration of digitalization and environmental life cycle assessment (LCA), enabling the design of manufacturing workplaces with a lower ecological footprint from the early stages of a project. The significance of the human factor and ergonomics for the sustainability of Industry 4.0 is systematically examined by Gualtieri [12], who stresses the importance of digital modeling and simulation of work operations.

Research from Wróbel and Hoffmann [13] demonstrates that digital technologies not only increase production flexibility but also support the introduction of environmental innovations and workplace optimization. From the perspective of social sustainability, important research by Hasanain [14] analyses the impact of digitalization on employee well-being and job satisfaction in industry. Current trends in social sustainability are further developed by [14], who investigates digital innovations in the processes of collaboration, engagement, and inclusion within manufacturing teams.

Gruchmann et al. [15] shows that environmental innovations combined with digital strategies directly lead to improved corporate performance and long-term environmental sustainability, while de Wilde [16] highlights the importance of digital simulations for workflow planning, which reduces physical strain on workers and optimizes both material and energy consumption.

Studies by Farooq et al. [17] make a significant contribution to the adaptation of workplaces for workforce diversity and an aging population, demonstrating the use of digital ergonomics in the planning of personalized working environments.

In the area of standardization and management systems for sustainability and ergonomics, the key works by Montoya-Reyes et al. [4] examine the linkage of ISO 14001 and ISO 45001 standards with digital workplace assessment, addressing the practical implementation of these standards.

A broader perspective on digital innovation and ergonomics in the context of corporate social and environmental responsibility is offered by additional publications—for example Roy [18] and Palomba et al. [19], who analyze modern methods of digital ergonomics and their impact on sustainable manufacturing, or Wrobel [20] who examines the direct impact of digitalization on environmental efficiency in industrial enterprises.

It is important to mention significant publications such as Li and Wang [21], who studied the linkage between digital production optimization and environmental assessment in real-world conditions, and the work Piras et al. [22], which documents the use of digitalization for optimization and reduction in environmental burden in the automotive sector.

From an ergonomics perspective, it is possible to observe the growing importance of ergonomics in manufacturing contexts. For example, Vigoroso et al. [23] show in their work that research focused on Design for Safety (DfS) in manufacturing contexts, focusing on the integration of human factors and ergonomics (HFE), appears 360 times among published works indexed in WoS and Scopus between 2006 and 2023.

Zare et al. [24] in their work investigate how integration of an ergonomic approach in the manufacturing production system can reduce defects and improve quality in the production process.

Berlin and Adams [25] in their book offer a comprehensive guideline for designing work systems to support optimal human performance.

Other authors propose a methodology for taking physical ergonomics into account addressing ergonomics in manufacturing contexts, e.g., Abdous et al. [26] and Sarbat and Ozmehmet [27].

The current trend towards humanization and sustainability of production systems brings with it the need to analyze and improve work processes. In summary, the latest studies in this field recommend a comprehensive integration of digitalization, ergonomics, and all three pillars of sustainability—environmental, social, and economic—emphasizing systematic evaluation and continuous improvement of manufacturing systems.

The paper’s focus is to answer following questions:

- What is the worker’s load while carrying out specific tasks?

- When using different methods (but with similar attitude to load assessment), will they show similar, or the same result, e.g., if one method will asset position as a bad will other method shows it is bad too?

- Can of the application of simple measures bring improvement in results of load assessment?

2. Materials and Methods

For worker load analysis, we selected a workstation where the hemming process of the front grille of the Mercedes Sprinter van is performed. The workstation is equipped with a HAP Daimler NCV3 assembly machine from Honsel Automation (Fröndenberg/Ruhr, Germany), which is used for assembly operations. Only experienced specialists are authorized to operate this machine. They must be capable of commissioning the machine, performing maintenance and repairs, disassembling and assembling individual components, ensuring the functionality of the components, reading schematics, assessing tasks, identifying potential hazards, and possess knowledge of electrical diagrams.

Additionally, the workstation contains two standard-size Euro pallets (1200 mm × 800 mm), from which the worker takes parts and subsequently returns them after processing. Technical Parameters of the HAP Daimler NCV3 machine are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Technical parameters of the HAP Daimler NCV3 machine.

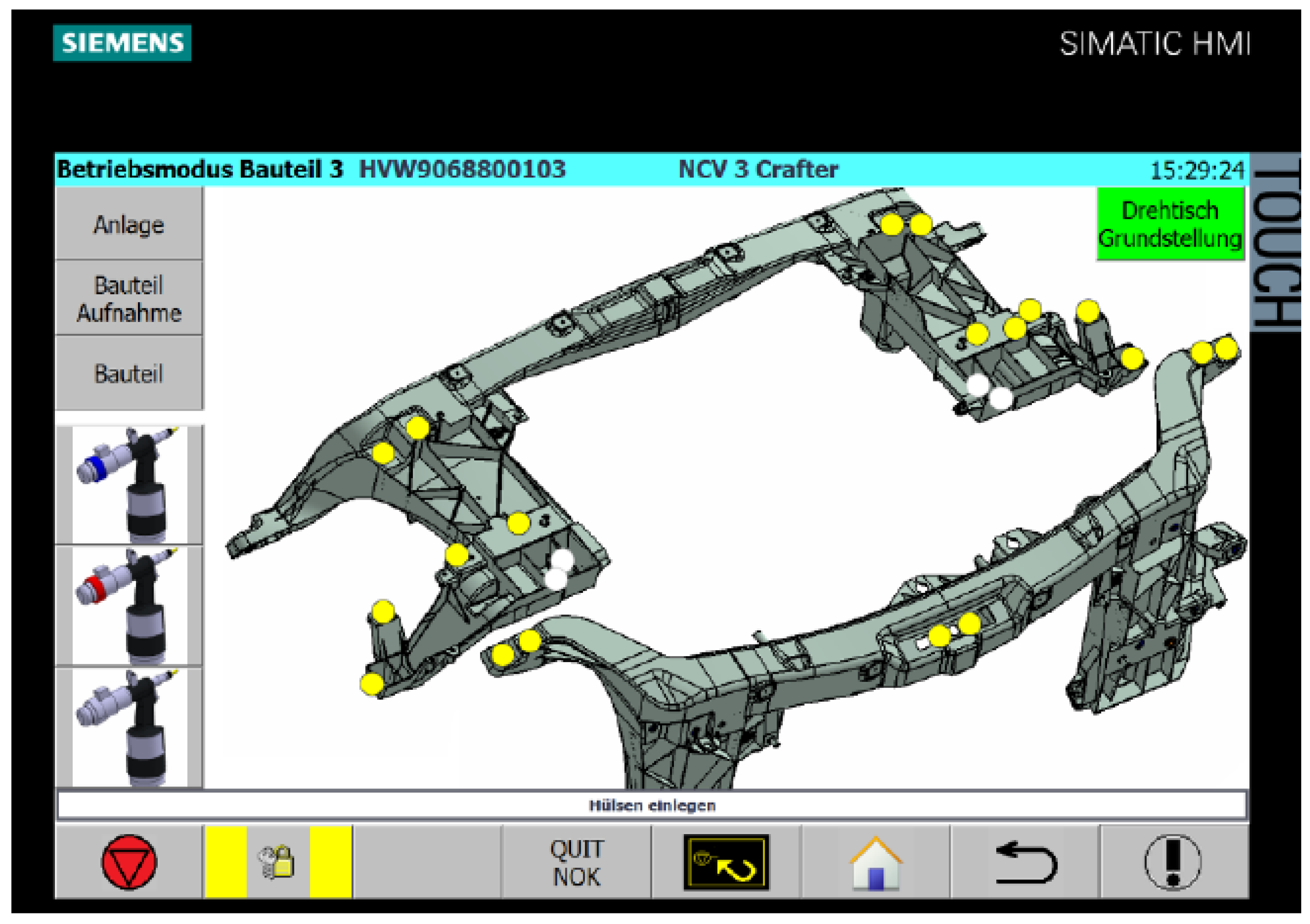

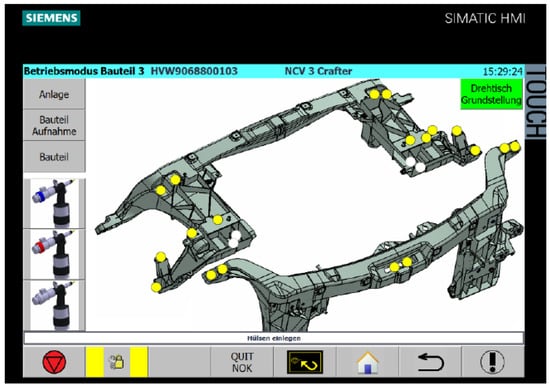

The machine is equipped with a screen (Figure 1) that serves as an aid to the operator during the processing of structural components. The content displayed on this screen is dynamic and depends on the installed fixture for the structural component and its status.

Figure 1.

HAP Daimler NCV3 machine screen.

This screen can display various types of information, such as assembly instructions, visual indicators, safety warnings, or machine status updates. Through this interface, the operator can monitor the current progress of the assembly process, verify the correct positioning of parts, check assembly procedures, and obtain necessary instructions in the event of problems. This feature contributes to operational efficiency and enhances the accuracy of assembly operations.

Given the dynamic nature of the screen’s content, it is important that operators are properly trained in the use of this technology and can interpret the displayed information correctly. This ensures the safe and efficient operation of the machine and minimizes the risk of errors during assembly processes.

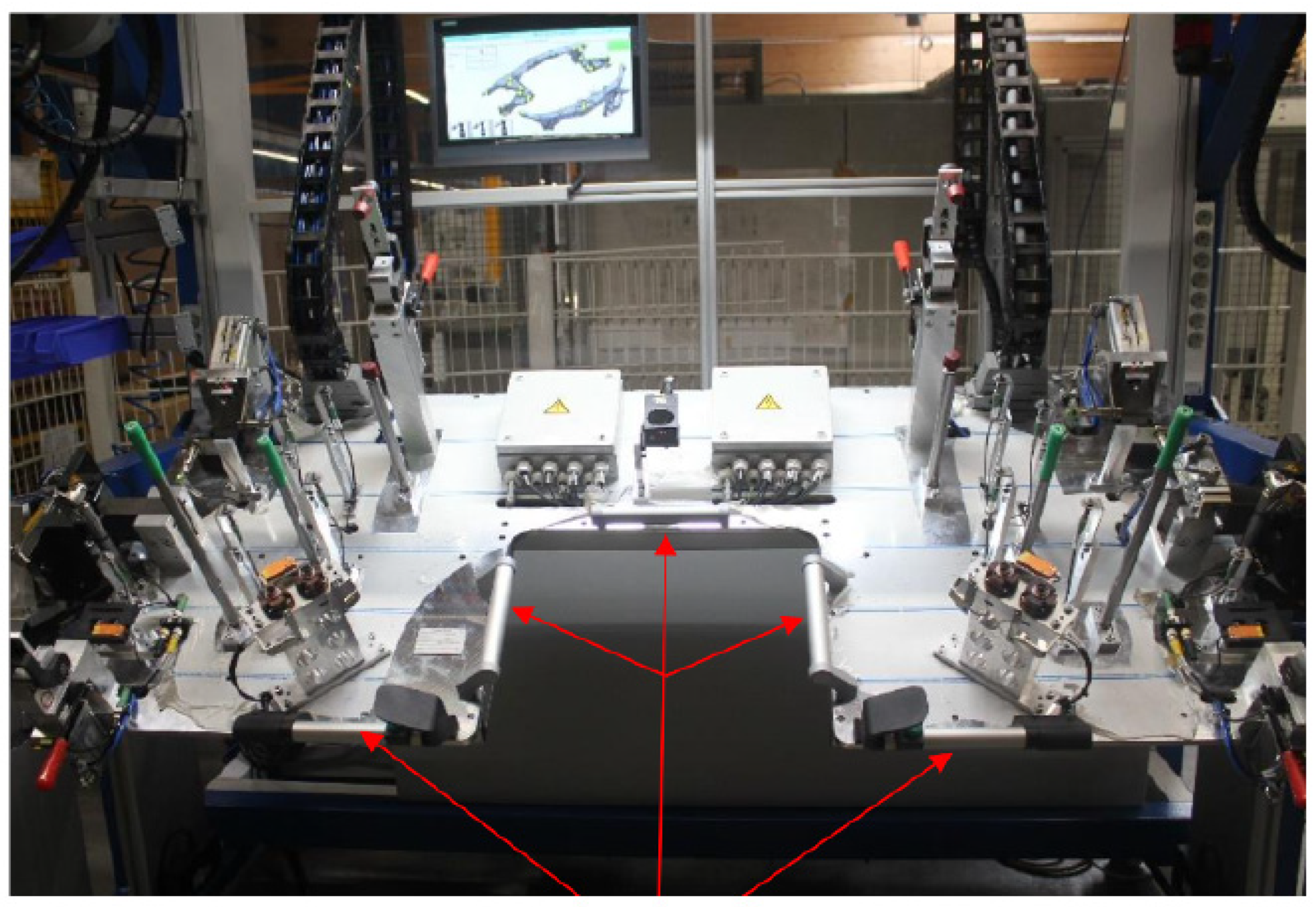

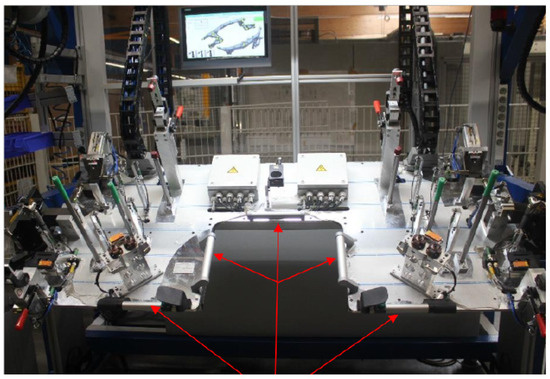

The device is equipped with a swing unit (Figure 2), which can be used at any time except during the initiation of the process, when the basic position (35°) is expected. During the swinging motion, it is essential that all insertion devices are secured in their holders and that both hands are placed on the appropriate handles. The foot switch can then be used to release the brakes. When rotating the unit, it is always important to ensure that no other person is present in the vicinity of the device, as there is a risk of injury during repositioning. The basic position is indicated in green on the display.

Figure 2.

Swing unit handles for position changing.

When the basic position is reached, the display shows “Insert structural component.” The structural component is aligned against the guideposts and, when it is flush with both the device and the posts, it can be lowered onto the posts until it fits completely. The display then prompts “Clamp structural component”. If this message does not appear, it is necessary to check the placement of the component on the bushings and supports. Once properly inserted, all tensioners must be manually tightened completely. When tightened, the device automatically locks the tensioners.

The device then prompts the initiation of the hemming process. The control system determines the required insertion tool for this purpose and displays it on the screen. The other tools are locked. The order of hemming is determined by the device and displayed on the screen in gray.

The manual tool is fitted onto the indicated bushing, and after pressing the trigger, the insertion stroke is performed. When the preset force and stroke distance are achieved, the retraction is initiated. If the process is successful, the display indicates this with a green dot; otherwise, a red dot is shown. This procedure is repeated three times, and then the insertion tool is placed back in its holder.

The device is also equipped with three emergency stop switches to disconnect power in the event of an emergency. To activate the emergency stop, all emergency switches must be disengaged. An authorized person can return the device to the basic position using an additional switch in the control cabinet, ensuring that the machine is in a safe mode and ready for further operation.

For assessment of worker load chosen four methods were selected: RULA, SSP, OWAS, and Lower Back Analysis.

The Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) evaluates the exposure of workers to the risk of upper limb disorders. By this method, it is possible to assess the risk of upper limb disorders based on posture, muscle use, the weight of loads, task duration and frequency. RULA assigns the evaluated task a final score that indicates the degree of intervention required to reduce the risk of an upper limb injury [28].

This final score consists of intermediate score assigned to individual body parts (upper arm, forearm, wrist, wrist twist, neck, and trunk). Final score ranges from 1 to 7 and it is represented by specific color.

- Final score 1 and 2: (Green color)—Indicates that the posture is acceptable if it is not maintained or repeated for long periods of time.

- Final score 3 and 4: (Yellow color)—Indicates that further investigation is needed and changes may be required.

- Final score 5 and 6: (Orange color)—Indicates that investigation and changes are required soon.

- Final score 7: (Red color)—Indicates that investigation and changes are required immediately [29].

RULA helps to identify and prioritize the manual tasks that need the most urgent attention for ergonomic modifications [28].

The Static Strength Prediction (SSP) method helps evaluate the percentage of a working population that has the strength to perform a task based on posture, exertion requirements, and anthropometry. Method analyzing physical tasks involving lifts, lowers, pushes, and pulls requiring complex hand forces, torso twists, and bends. It also calculates joint torques and angles using the workers posture, anthropometry, and hand loads. It helps to identify the tasks of a job where the strength requirements exceed the capabilities of a working population. It can be used to demonstrate to workers the proper postures for tasks carrying out [28].

The Ovako Working Posture Analysis (OWAS) provides a simple method for quickly checking the comfort of working postures and determining the urgency of taking corrective measures. It evaluates the relative discomfort of a working posture based on positioning of the back, arms, and legs, as well as load requirements. Method assigns the evaluated posture a score that indicates the urgency of taking corrective measures to reduce the posture’s potential to expose workers to injury [28].

Methods use scores in range from 0 to 4.

- Score 0, 1: Posture is normal; no corrective action required.

- Score 2: Posture may have some harmful effect; no immediate action is required but may be necessary soon.

- Score 3: Posture has a harmful effect; corrective measures must be taken as soon as possible.

- Score 4: Posture has a very harmful effect; corrective measures must be taken immediately [28].

The Lower Back Analysis method evaluates the spinal forces acting on a human’s lower back, under any posture and loading condition. It allows to determine whether workplace tasks exceed NIOSH threshold limit values or expose workers to an increased risk of low back injury. “The Low Back Analysis method uses a complex biomechanical low back model based on anatomical and physiological data from scientific literature. The tool calculates compression and shear forces at the L4/L5 vertebral joint and compares the compressive forces to the NIOSH recommended threshold limit values [28].”

These four methods were selected because they allow for a quick assessment of working position and they are commonly used to evaluate workers’ manual tasks in praxis.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation of the Work Procedure in Tecnomatix Jack Software for Optimization Implementation

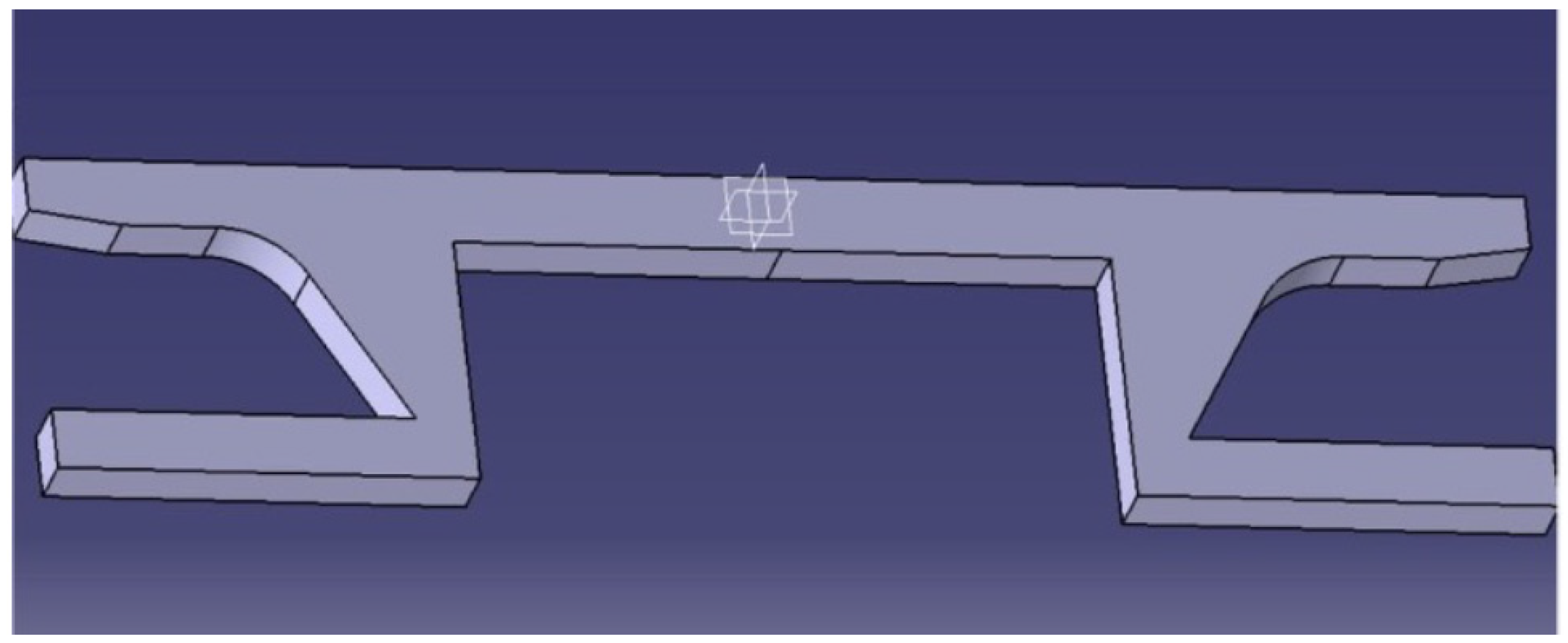

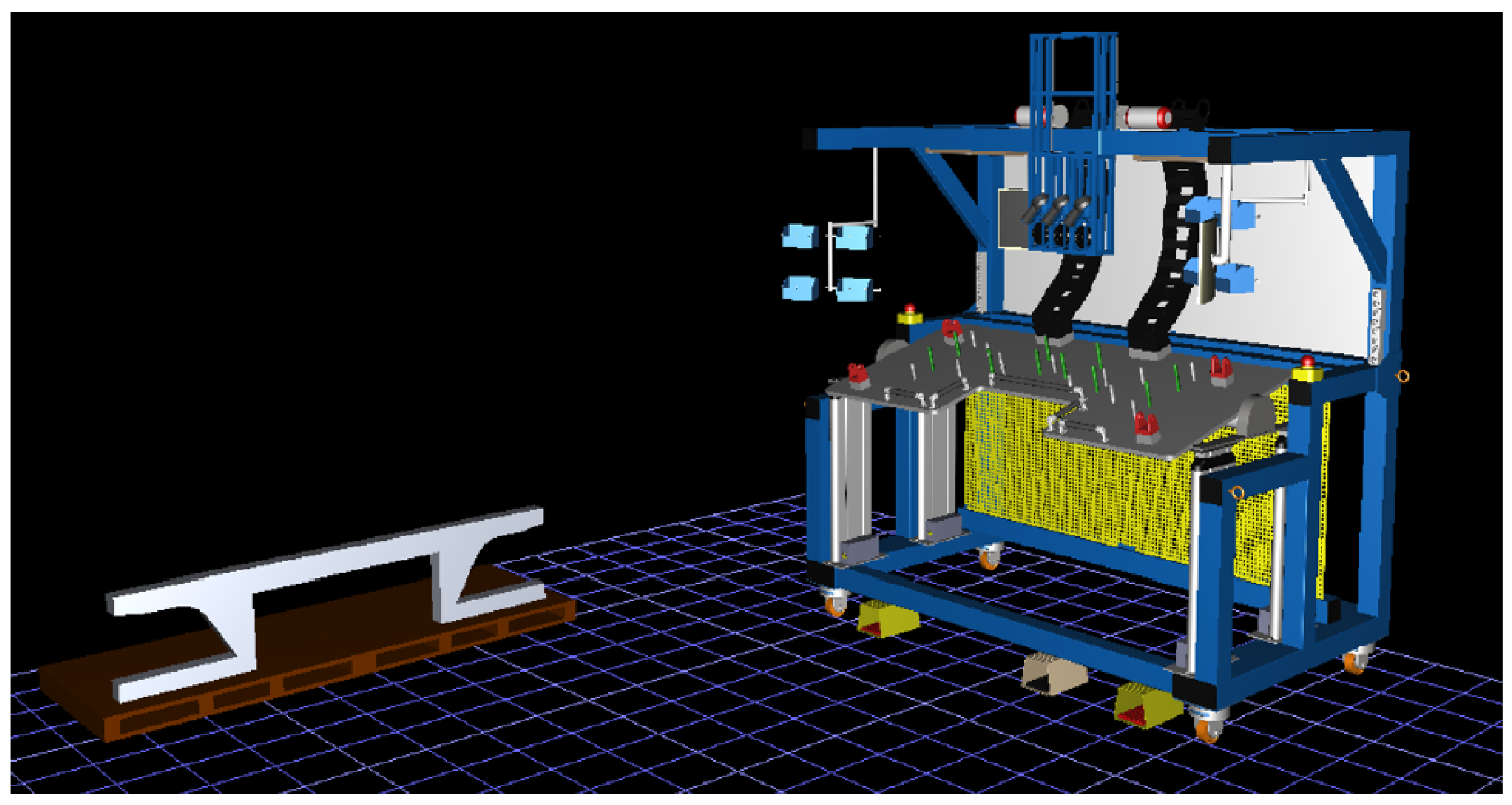

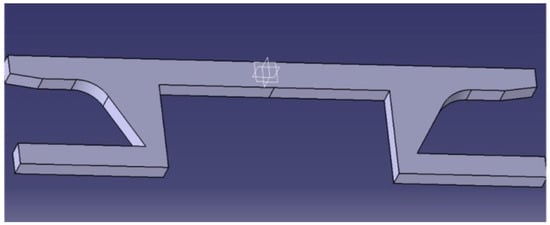

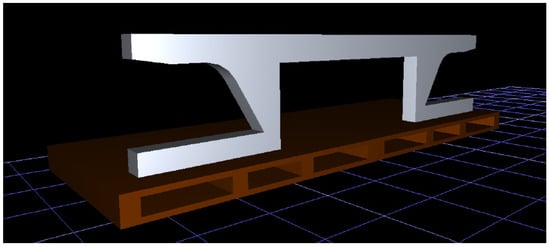

Based on the available information about the workstation, a digital model of the workstation was created in Tecnomatix Jack software at a 1:1 real scale. The elements of the workstation were either used from the program’s library or created in Catia V5 software. Models created in Catia were converted into a format compatible for import into the Tecnomatix environment. The structural component used by the worker for assembly operations was modeled in Catia V5 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural component (simplified) modeled in Catia V5 software.

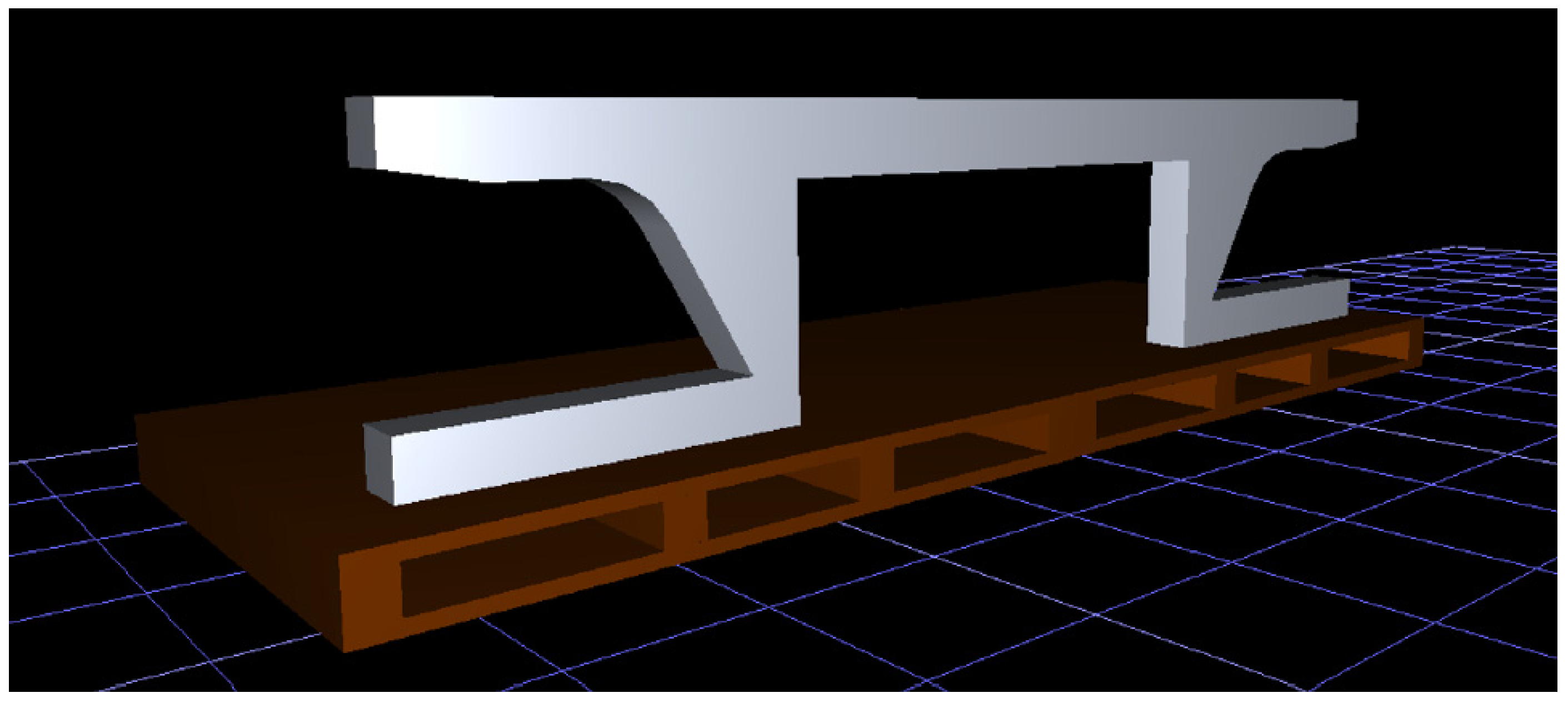

The project began by modeling the work environment in which the worker would perform the assembly operation. First, two standard-size Euro pallets (1200 mm × 800 mm) from the Tecnomatix Jack software library were inserted into the workspace and the created component was placed onto them. This component was converted into the .jt format to enable its insertion into the software environment. The individual parts were positioned using the “Move” command and by dragging them with the mouse. Their precise positions were subsequently defined using the “Snap” command, selecting the appropriate options as needed, such as face position, face orientation, face center, and face plane. The modeled component inserted into Tecnomatix Jack software is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Modeled component inserted into Tecnomatix Jack software.

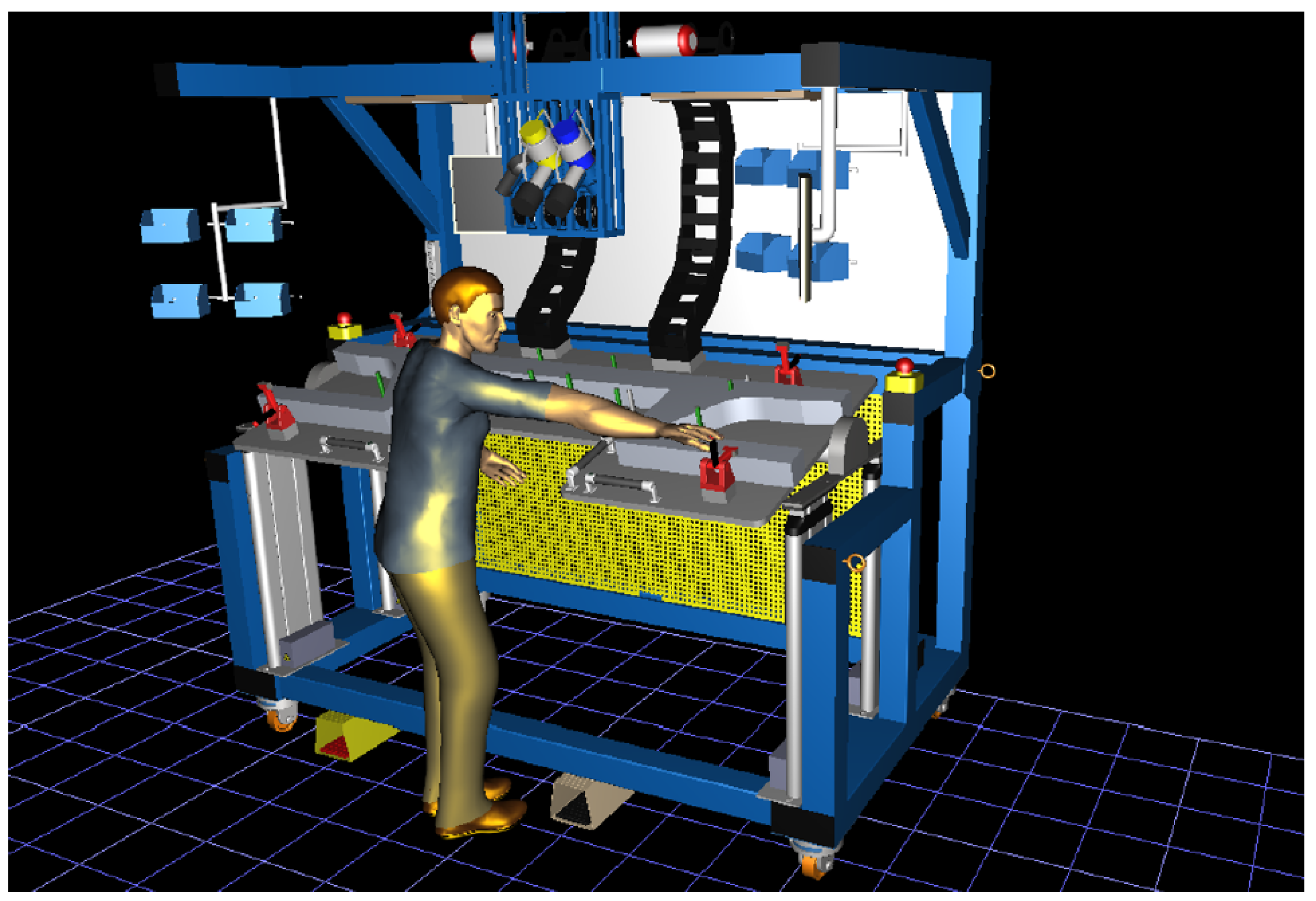

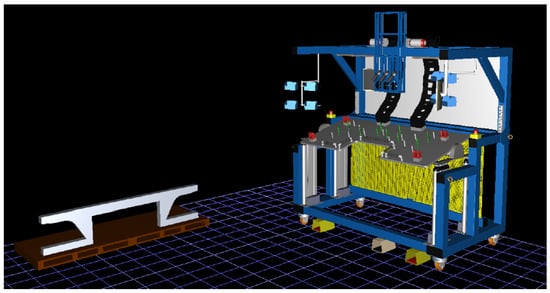

Subsequently, we inserted the workstation where the worker would perform the assembly (Figure 5). However, it was necessary to individually integrate and adapt within the machine the components that would need to be manipulated during the simulations, specifically the insertion tool and four clamps.

Figure 5.

Workstation created in Tecnomatix Jack software.

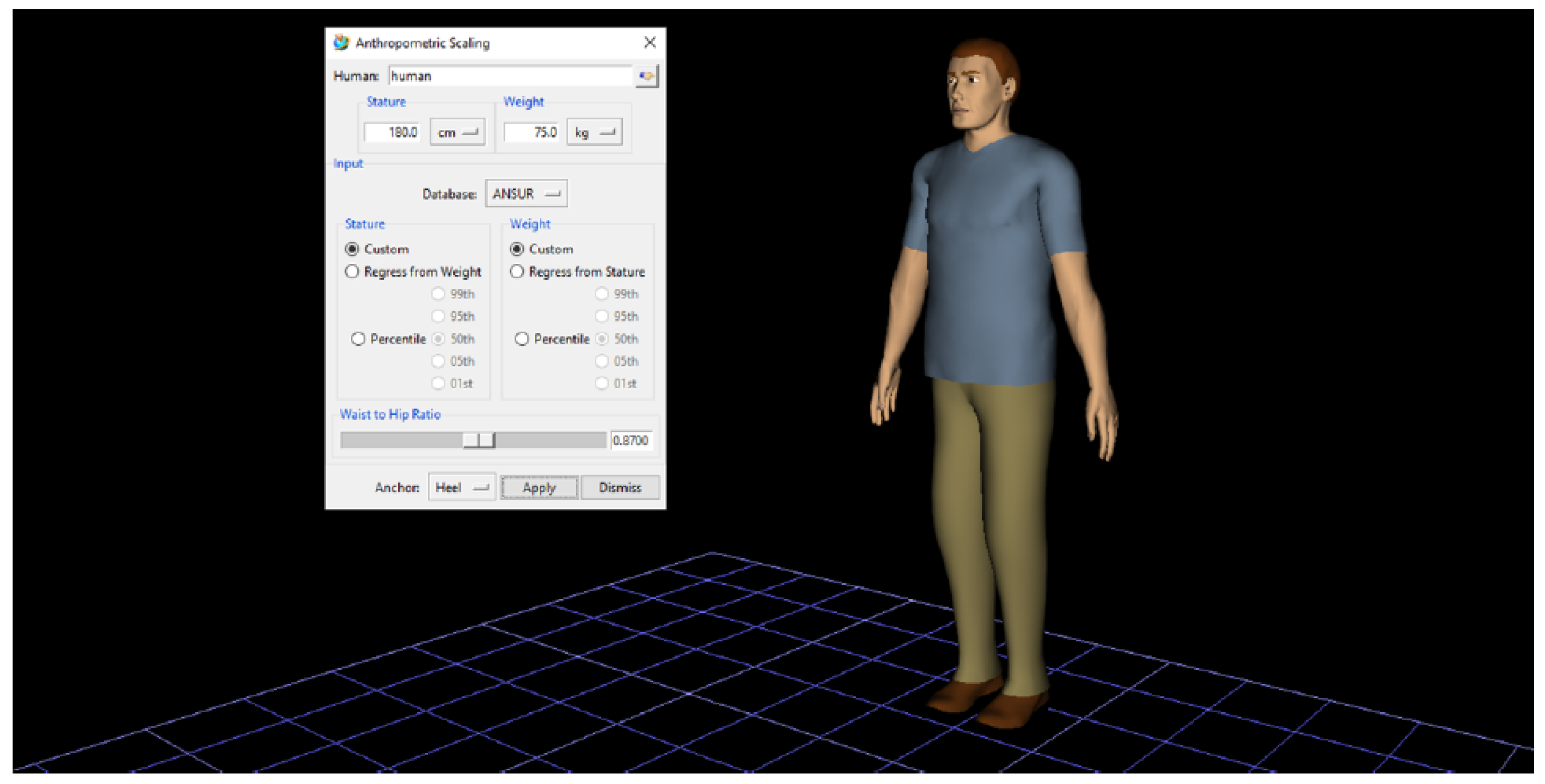

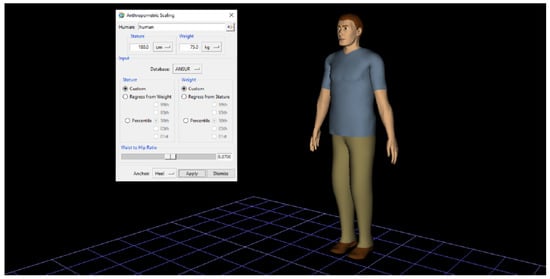

After creating the digital model of the workstation, a mannequin was placed at the workstation. Its purpose is to simulate the worker’s movements at the workstation and to perform work tasks. The software offers various mannequin options. The standard male represents a virtual model of an average male figure with a height of 174.2 cm and a weight of 77.7 kg. The software allows direct adjustment of height, weight, body type, and even ethnicity during the simulation. The standard female represents a virtual model of an average female figure with a height of 163 cm and a weight of 61.3 kg. The human model from the library enables loading a ready-made virtual human model directly from the software library. The custom model option allows the creation of a virtual human with user-defined parameters. For the purposes of this paper, the first option was selected. In the project, the worker’s parameters were adjusted to a height of 180 cm and a weight of 75 kg. Before starting the simulation, the position of the worker can be specified. The mannequin model was placed (Figure 6) in front of the machine.

Figure 6.

Worker mannequin and its parameters.

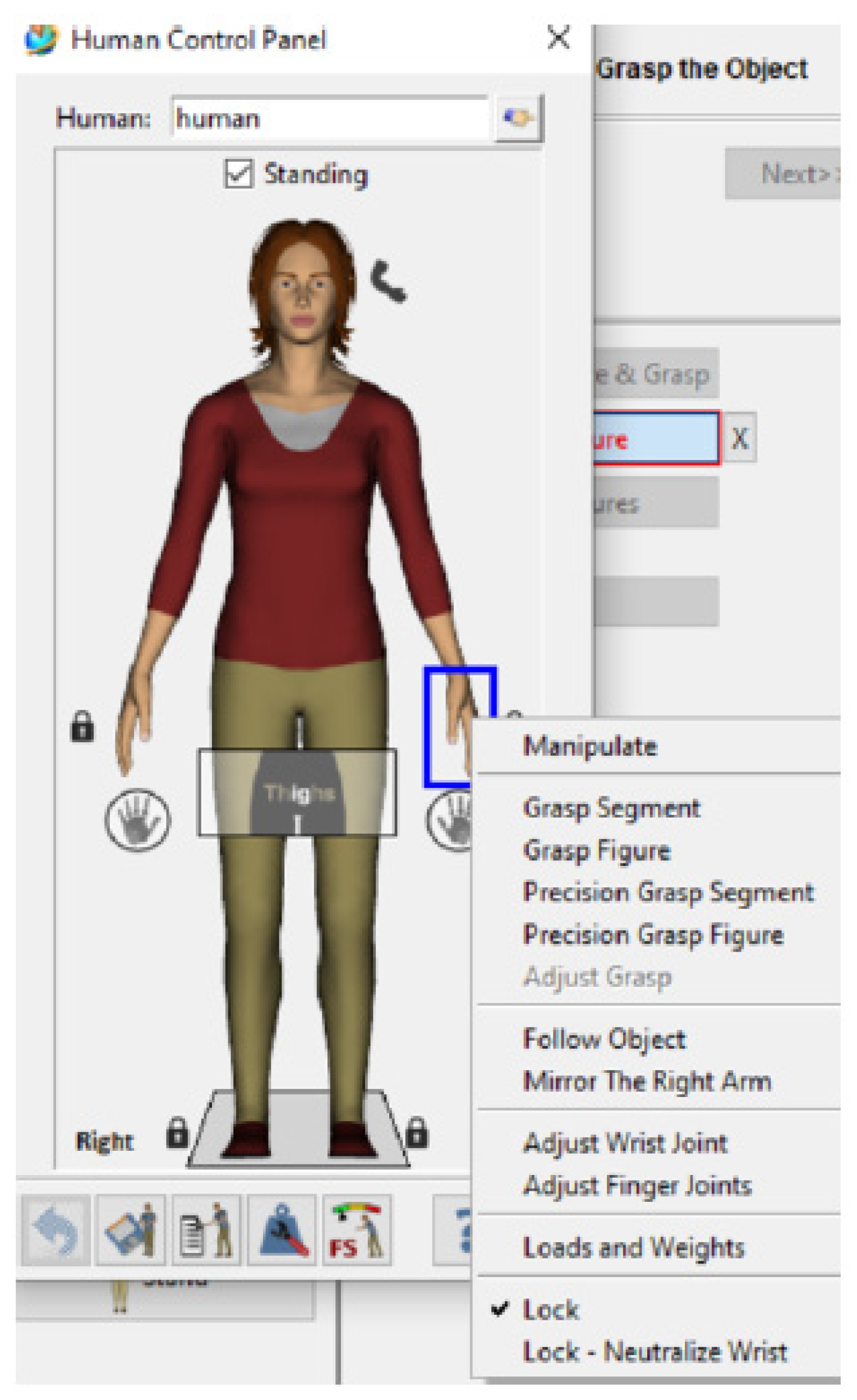

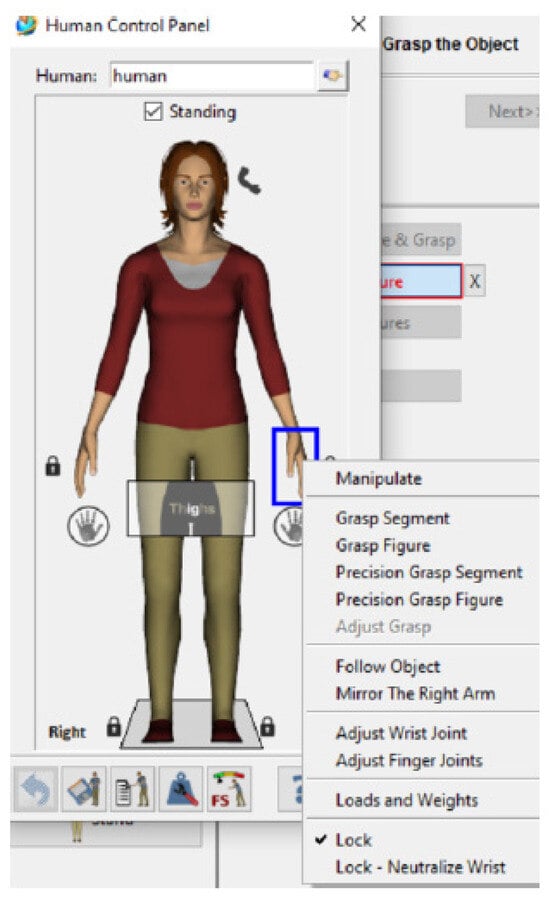

The main panel offers manipulation options for each body part via the context menu (Figure 7). The regional context menu in Tecnomatix Jack provides options for manipulating individual parts of the figure (arms, legs, head, etc.), enabling precise adjustment of the figure’s position and orientation within the environment. It provides tools for creating animations for the figure, displays various tools for manipulating the figure and objects in the environment, serves to set character properties (such as colors, clothing, etc.), and offers auxiliary information and instructions for using Tecnomatix Jack.

Figure 7.

Context menu in Tecnomatix Jack.

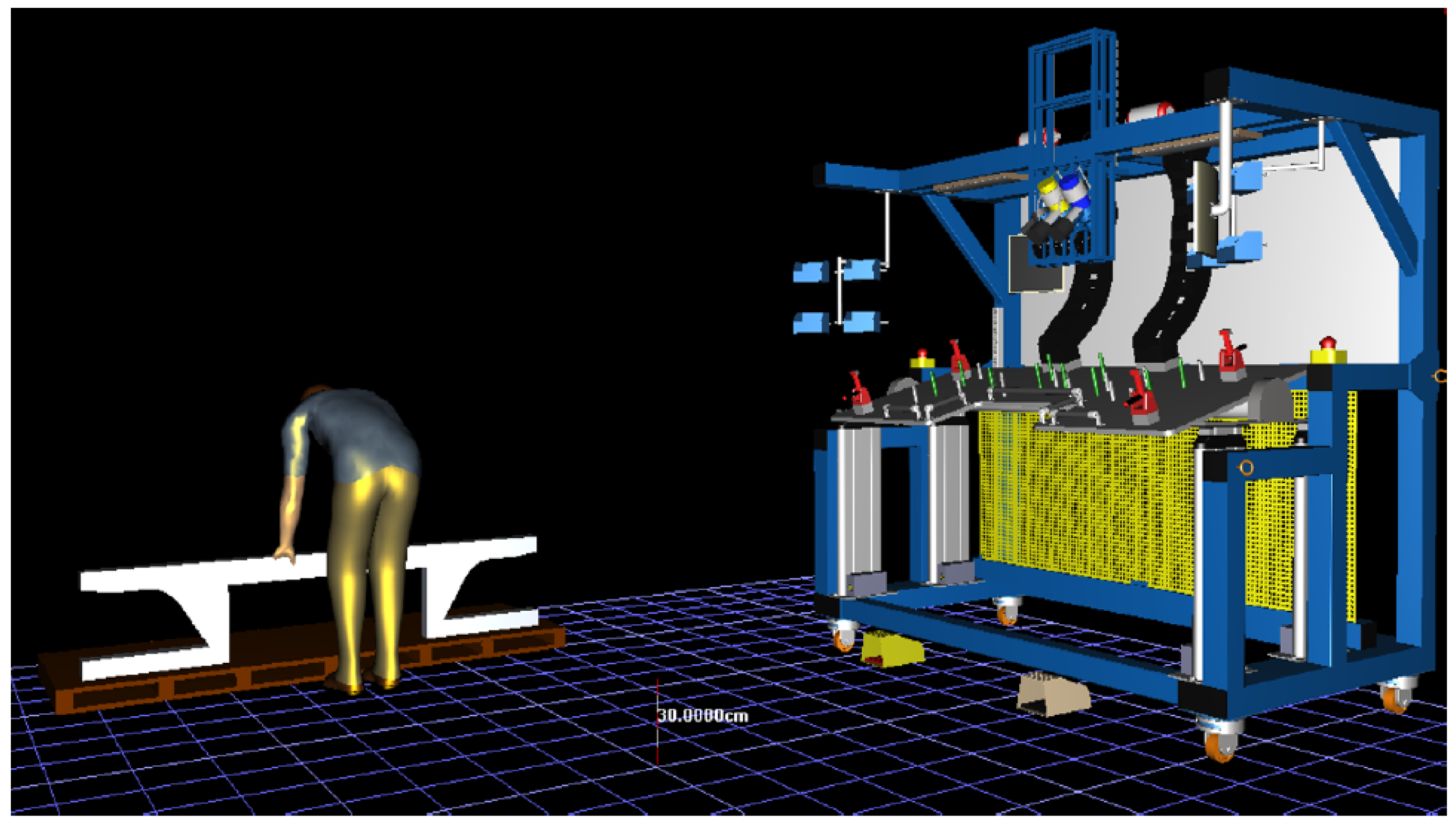

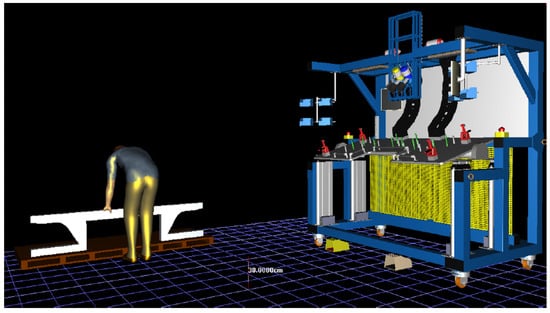

Description of simulated working activities: the worker, who was initially standing by the machine at the start of the simulation, approached the pallets where the component was placed. He bent down, picked up the component, and then returned to the machine to begin the assembly operation. Removing the component from the pallets is in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Removing the component from the pallets.

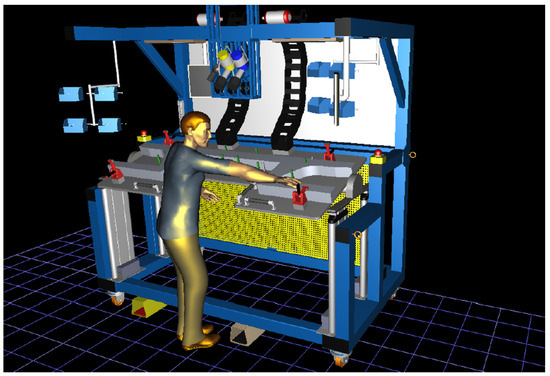

After placing the component, the worker clamps it using four clamps, employing his right hand throughout the entire procedure. He begins with the lower right clamp, continues with the upper right, then moves to the left side, proceeding from top to bottom. It was necessary to insert the clamps into the environment individually, to enable selection of each clamp and to simulate the worker’s actions during the simulation (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Clamping the component.

When the component is clamped, the worker takes the insertion tool, which is stored above him, and performs four assembly operations in the same sequence as for clamping the component, moving from right to left. The insertion tool was also inserted into the software environment separately, so that the worker could operate it independently during the simulation.

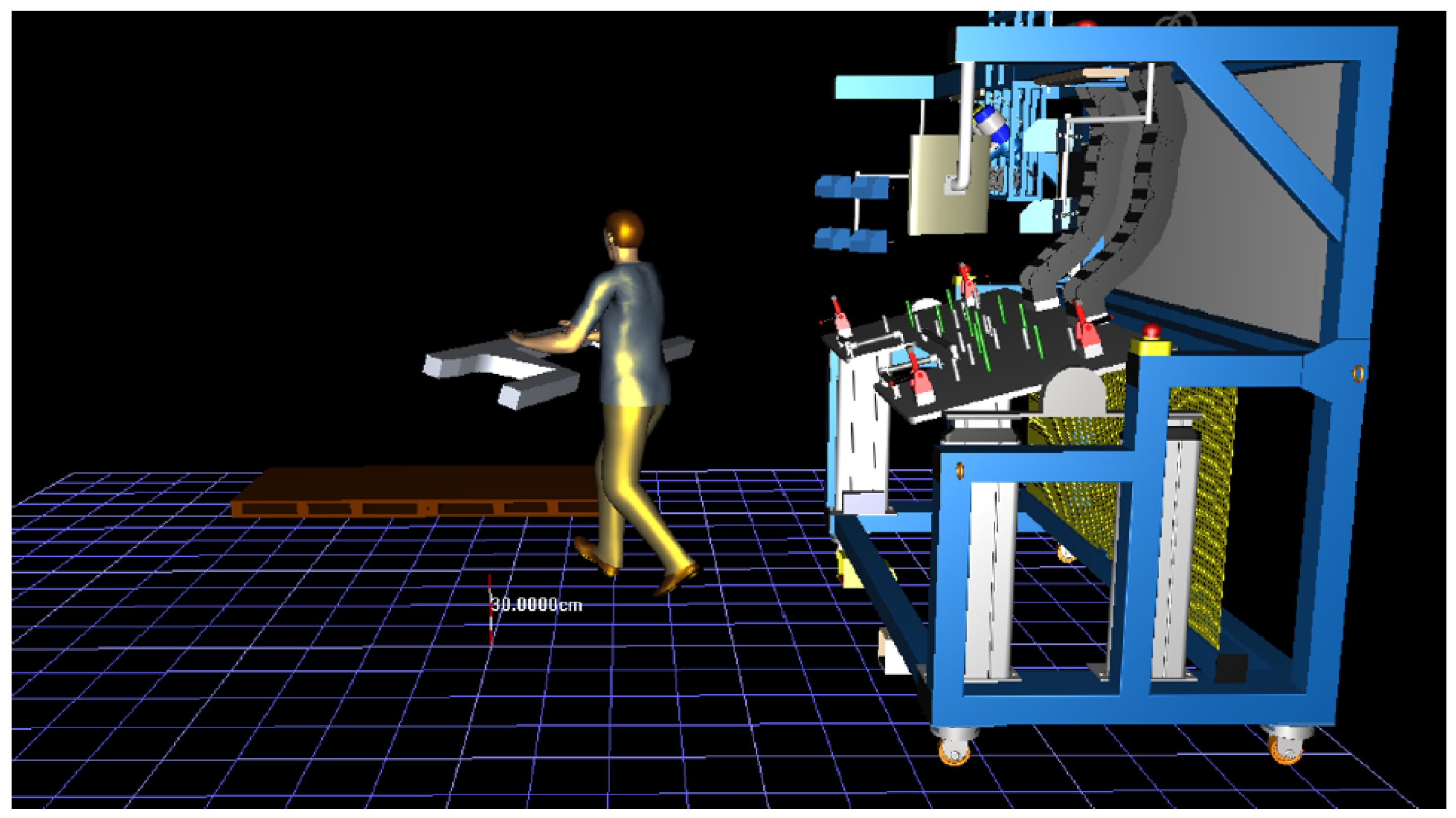

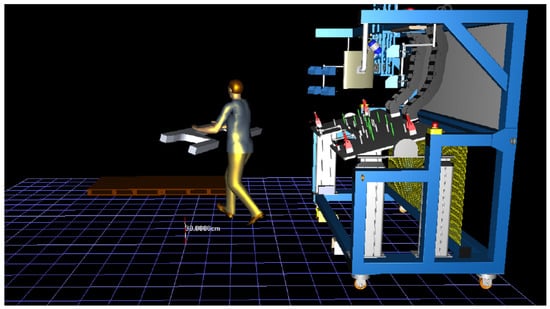

After completing this operation, the worker returns the insertion tool to its original position and unclamps the component. However, the clamps are released in the reverse order to how they were fastened: first the lower left, then the upper left, followed by the upper right and lower right clamps. After unclamping, the worker takes the component and carries it to the pallets, where it is then placed (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Transferring the component.

3.2. Worker Load Analysis

The analysis of the entire work process using four ergonomic assessment methods—RULA, SSP, OWAS, and Lower Back Analysis—enabled the identification of the most problematic operations, with primary attention focused on removing the component from the pallet, opening and closing the upper left clamp, handling and returning the tool, and placing the component back onto the pallet.

These analyses provided valuable insight into worker load and identified points where excessive stress may occur on muscles and joints. Their results served as the basis for proposing measures to improve workstation ergonomics and mitigate the risk of worker injury and fatigue.

All mentioned methods were used to observe whole working procedure, but because of paper range limitations only chosen examples are shown.

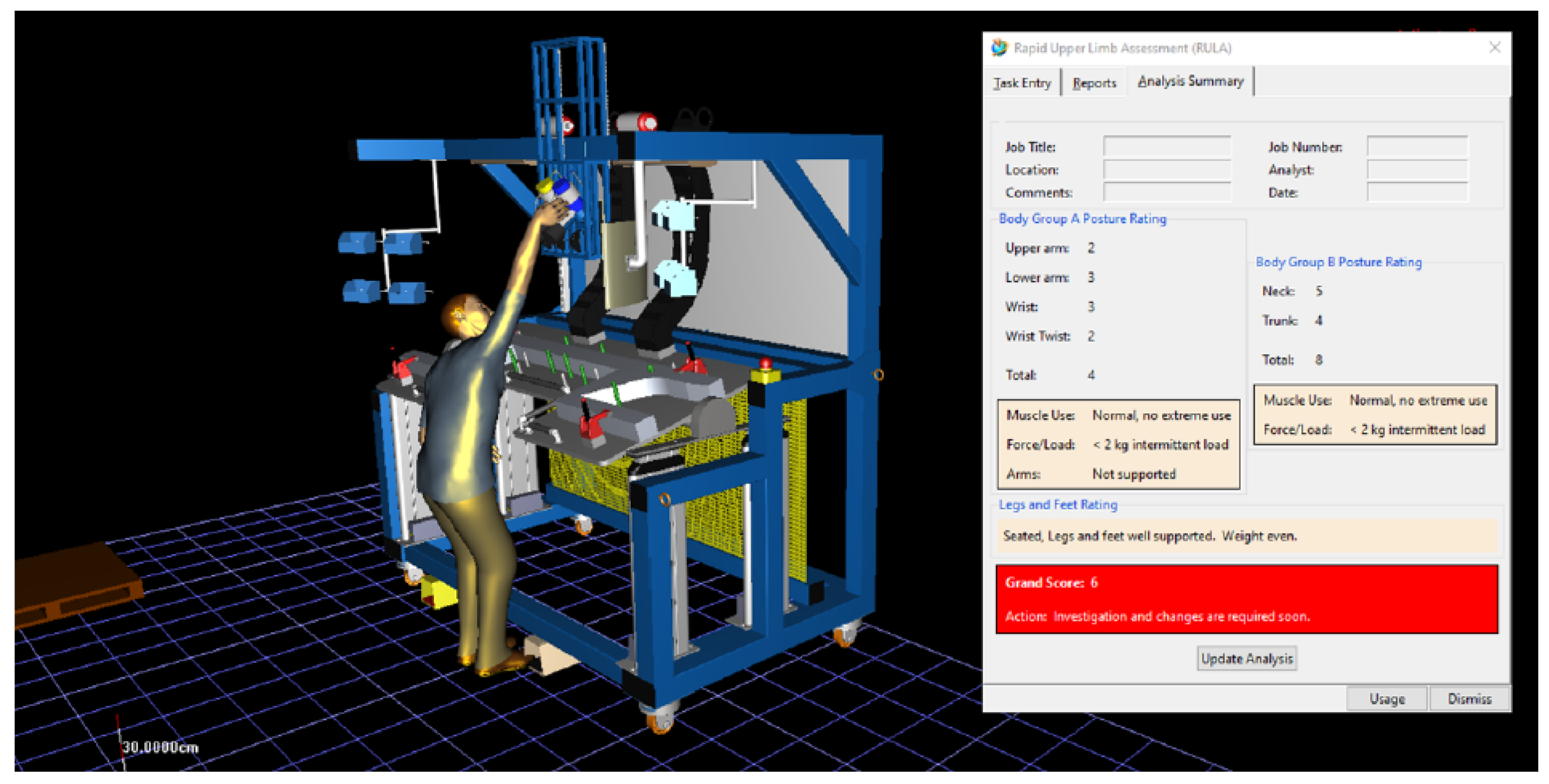

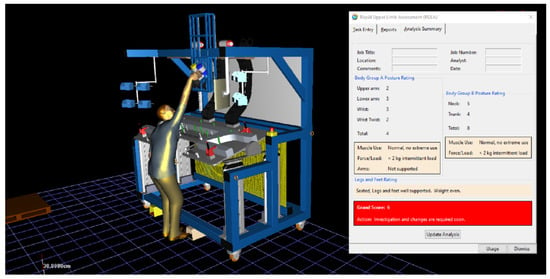

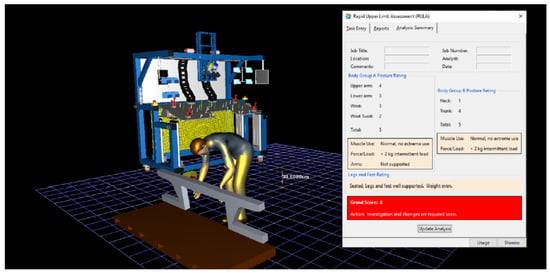

Figure 11 presents the results of the RULA analysis during the phase in which the worker retrieves the insertion tool. The overall score of the analysis reached a value of 6, which is considered very high and indicates a significant ergonomic risk. Such a high score suggests that the worker is in an inappropriate working position, which may lead to excessive strain on muscles and joints, thereby increasing the risk of injury. These results clearly signal the need for immediate measures to improve workstation ergonomics. The proposed changes should focus on optimizing the worker’s posture and reducing musculoskeletal strain.

Figure 11.

RULA analysis at the original workstation—retrieving the tool.

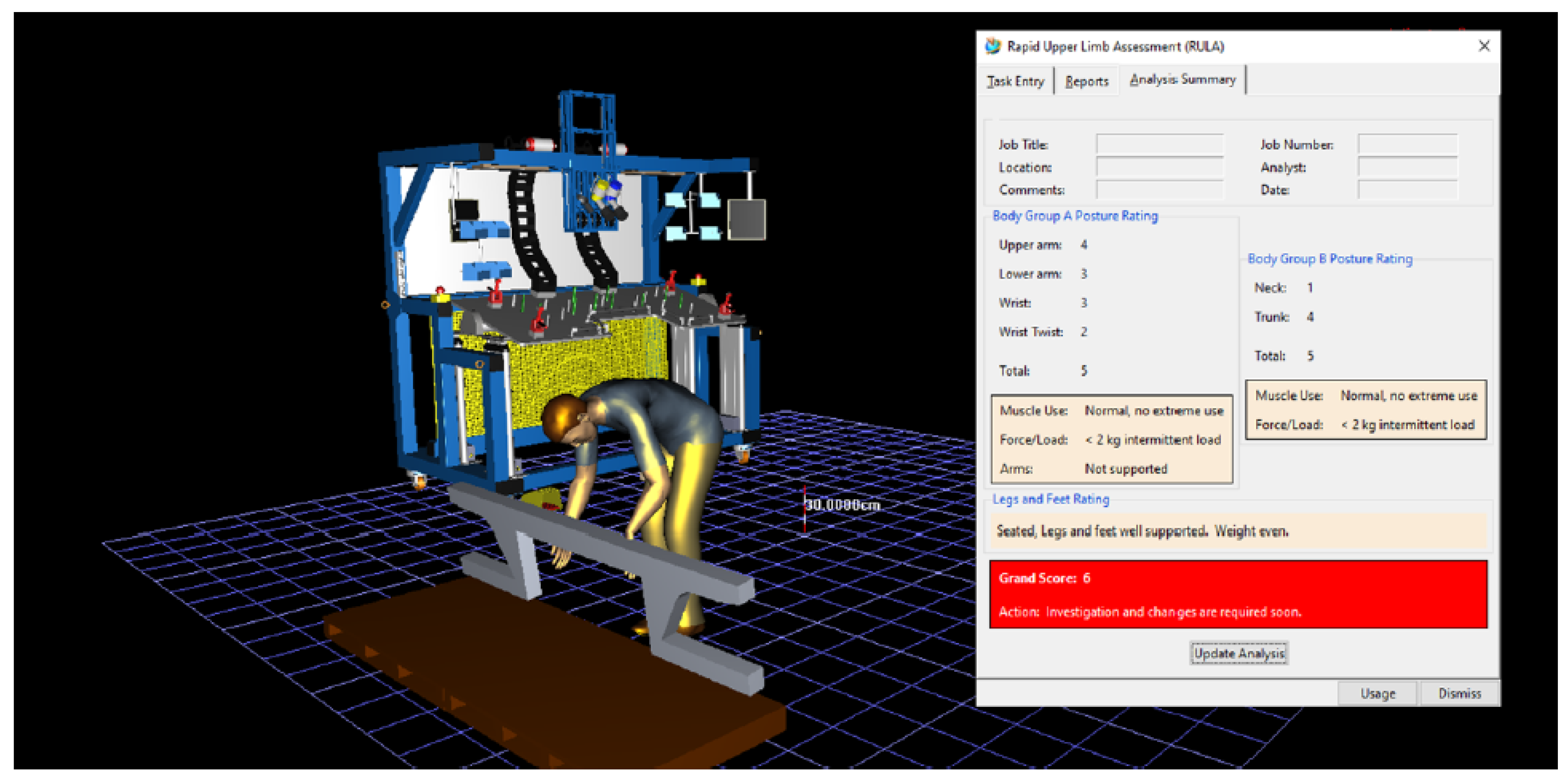

Observed situation is depicted in Figure 12, where the worker is placing the finished component onto the pallet. This operation is clearly an integral part of the work process and requires appropriate attention in terms of ergonomics and safety. The result of the RULA analysis, which considers the worker’s movements and body positions during task execution, was unsatisfactory—the overall score reached a value of 6. This result indicates that the worker’s posture and movements during the operation may be stressful or inappropriate for their health and comfort.

Figure 12.

RULA analysis at the original workstation—placing the component.

It is evident that measures must be taken to improve the ergonomics of this operation. Possible actions may include adjusting the working height, utilizing ergonomic aids for handling components, or modifying work procedures. These measures should be aimed at minimizing the risk of injury and protecting worker health in the workplace. It is important that managers and employees work together to identify and implement these changes to achieve a safe and efficient working environment.

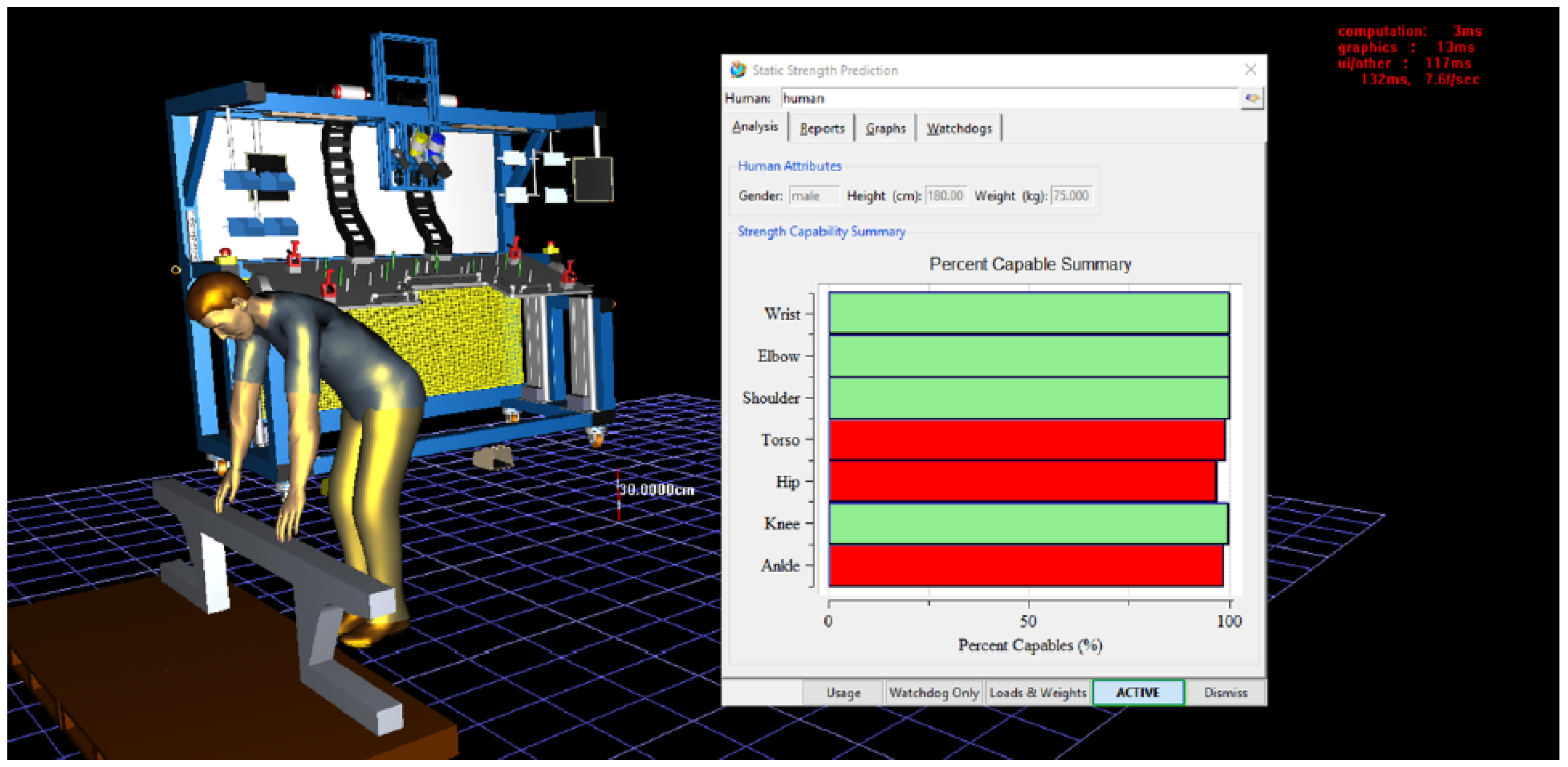

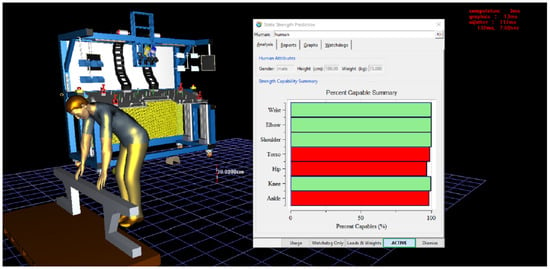

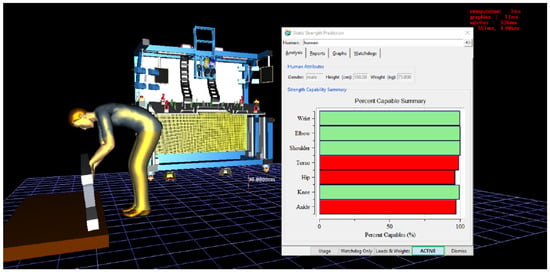

3.3. Static Strength Prediction (SSP)—Analysis at the Original Workstation

Figure 13 presents the results of the SSP analysis, in which the mannequin is depicted taking the component and carrying it to the workstation. The analytical perspective indicates that during this task, the torso, hip, and ankle are subjected to significant loading, which poses a risk to human health and necessitates urgent changes. This result provides a serious impetus to reassess working conditions and ergonomics in the workplace. It underscores the need to identify specific factors contributing to the load on these body parts and to propose measures to alleviate this strain.

Figure 13.

SSP analysis at the original workstation—retrieving the component.

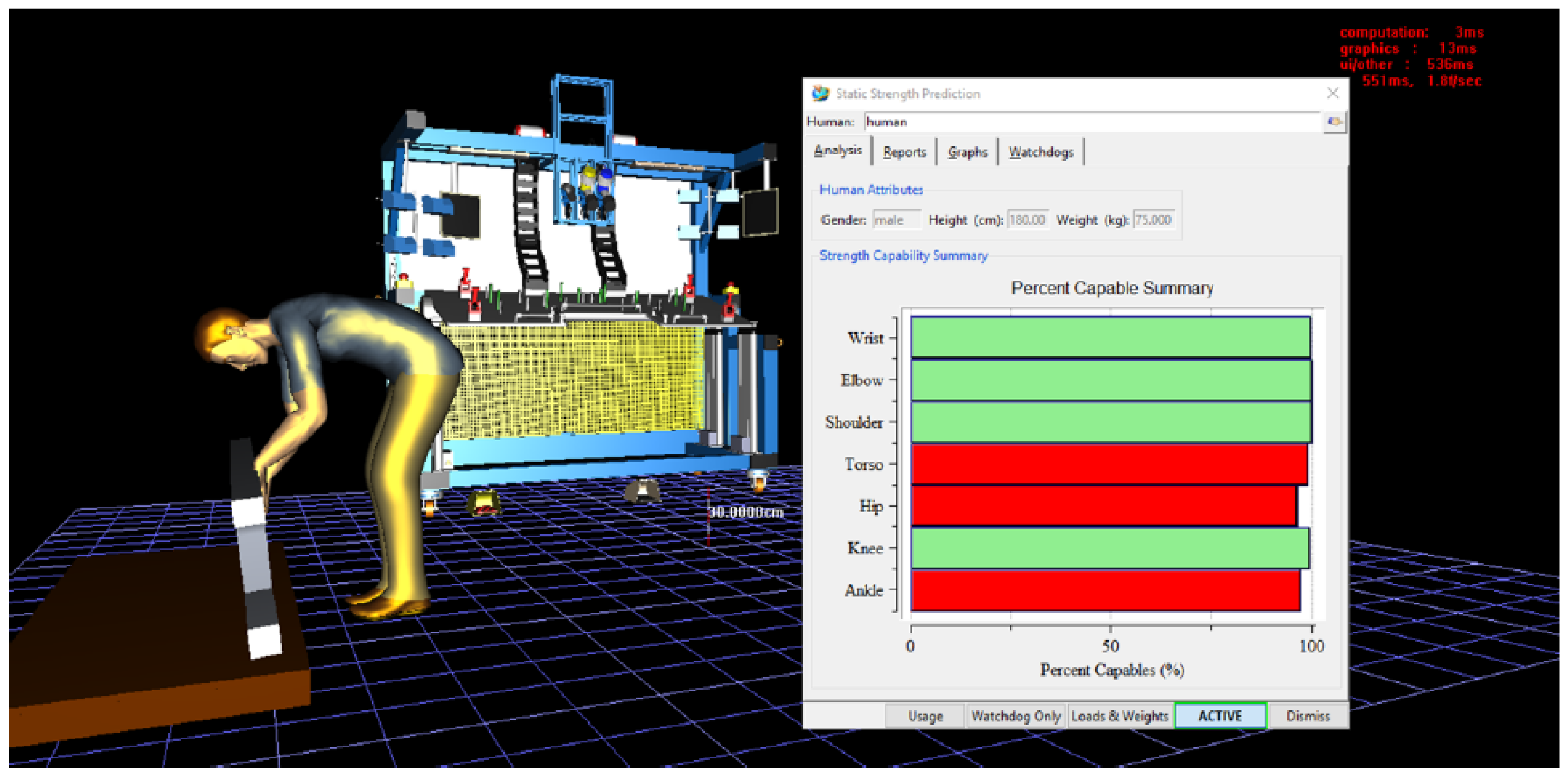

The results of the analysis during the placement of the component showed that the same body parts were subjected to load as when retrieving the component from the pallets. This conclusion is evident from the results of the analysis illustrated in Figure 14. Such a pattern of loading suggests that the worker is exposed to similar strain and risk of injury during both activities, which may lead to long-term health problems.

Figure 14.

SSP analysis at the original workstation—placing the component.

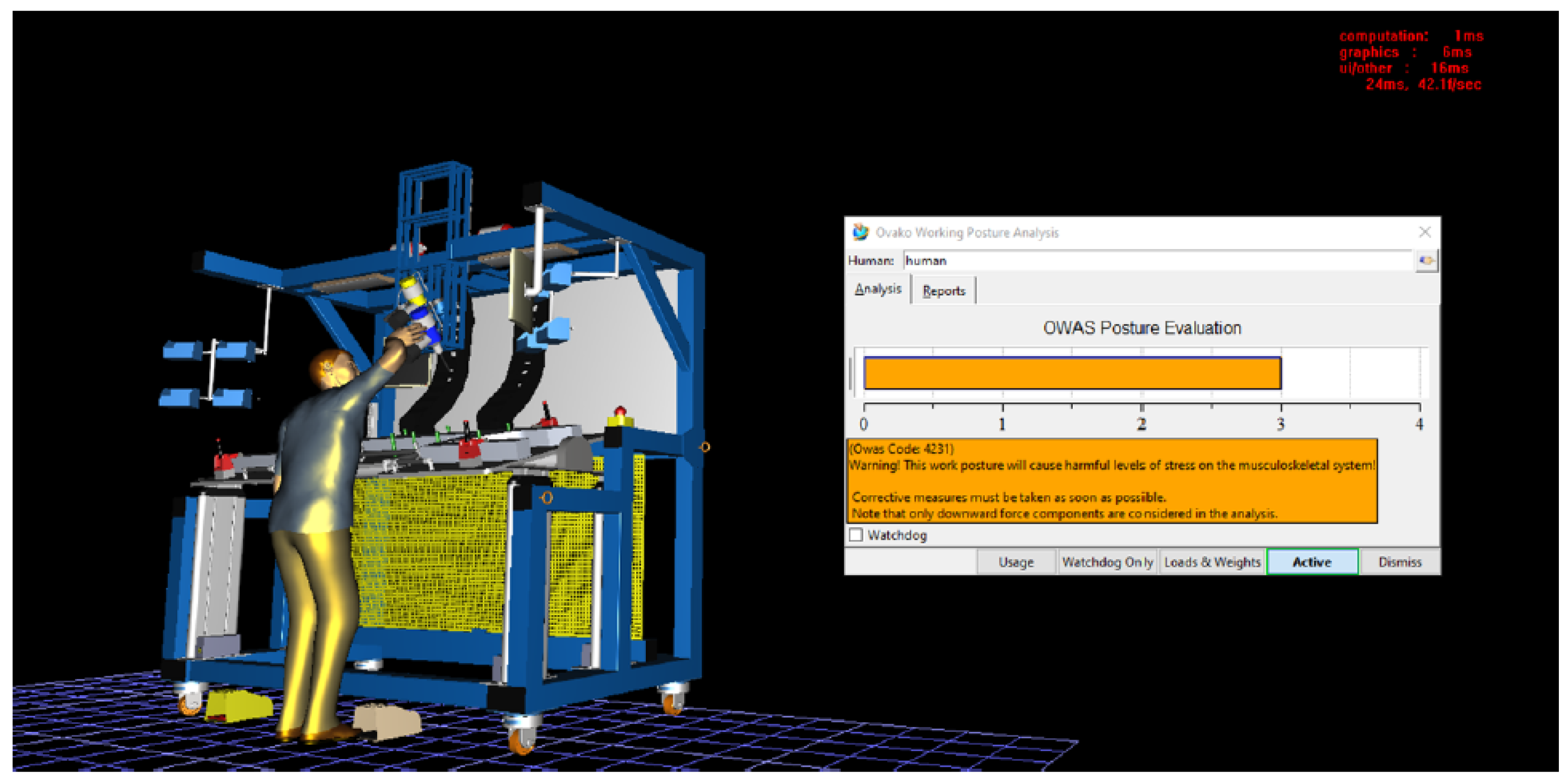

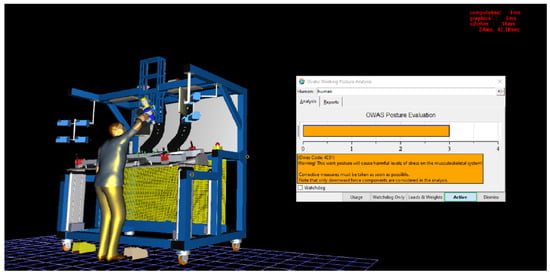

3.4. Ovako Working Posture Analysis (OWAS)—Analysis at the Original Workstation

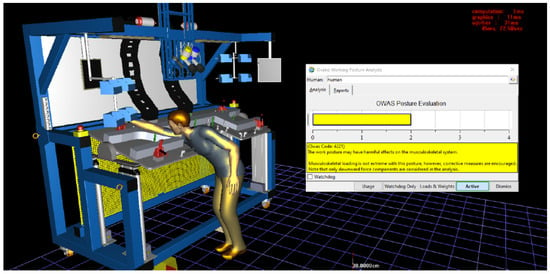

When retrieving the tool from the holder, the OWAS analysis also yielded unsatisfactory results. As shown in Figure 15, this position already causes harmful levels of stress on the musculoskeletal system. This finding necessitates prompt and effective corrective action. Changes in work procedures or modifications to work aids are essential to minimize the strain on the worker’s musculoskeletal system.

Figure 15.

OWAS analysis at the original workstation—retrieving the insertion tool.

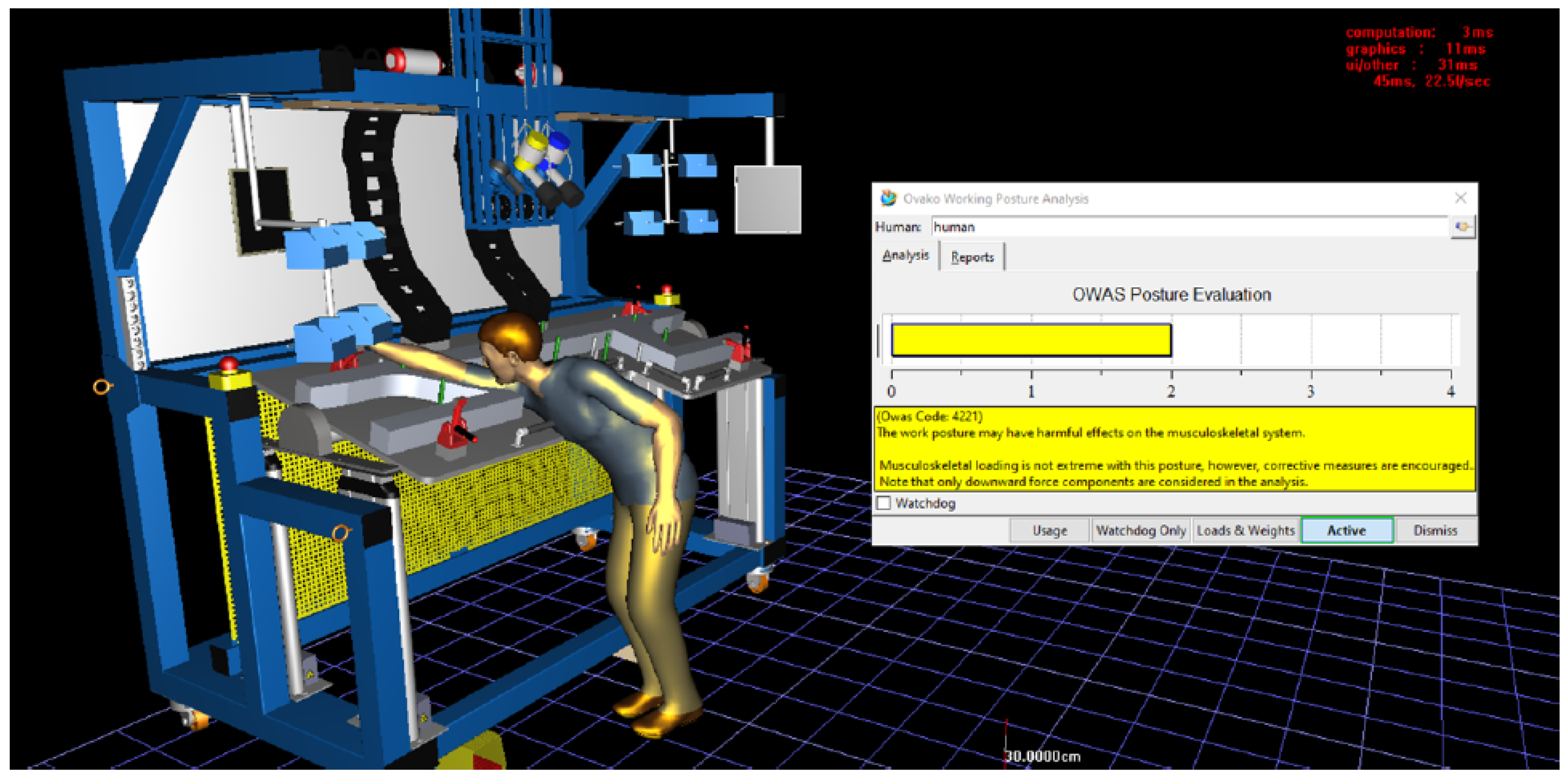

Figure 16 presents the results of the OWAS analysis when the worker opens the upper left clamp. The analysis determined that the working position may have harmful effects on the musculoskeletal system. It was found that the musculoskeletal load in this position is not extreme; however, compensatory measures were recommended. It should be noted that the analysis typically only considers force components directed downward. This analysis provides valuable information regarding working positions that may lead to excessive strain on the worker’s musculoskeletal system.

Figure 16.

OWAS analysis at the original workstation—opening the upper left clamp.

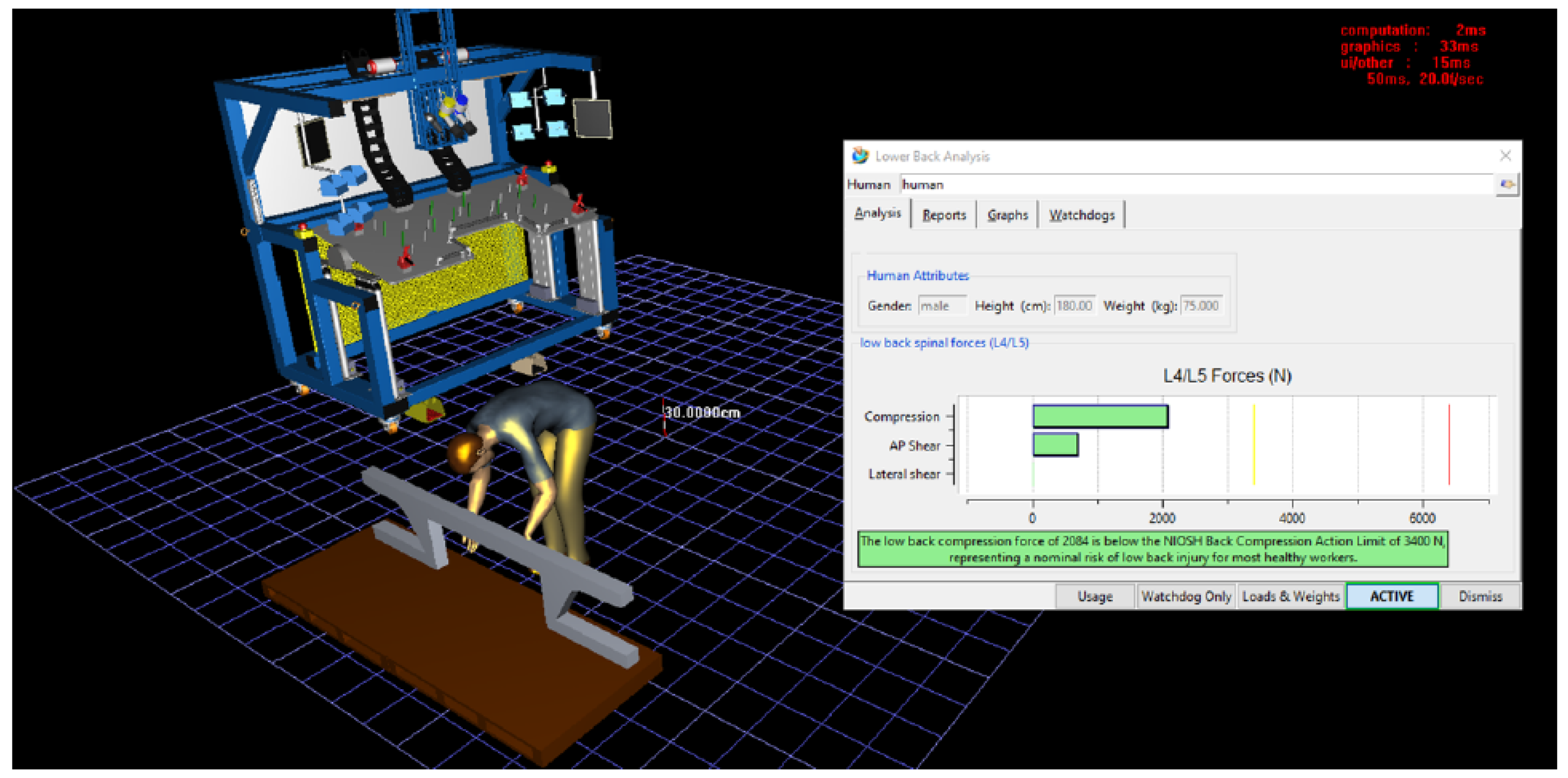

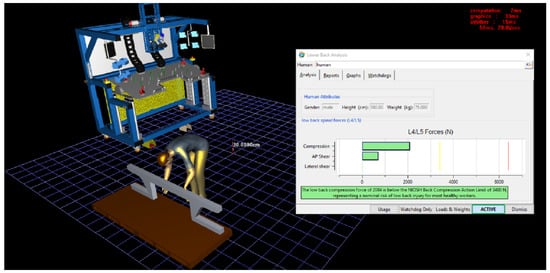

3.5. Lower Back Analysis at the Original Workstation

The final analysis we conducted was the lower back analysis (Figure 17). The values obtained throughout the entire simulation are acceptable. The maximum permissible lower back load should not exceed 3400 N. If the value is higher than 6000 N, there is a high risk of workplace injury. These results are encouraging and indicate that the worker’s posture and movements do not create excessive strain on the lower back. It is important to maintain this load at a safe level to minimize the risk of occupational injuries and to protect worker health.

Figure 17.

Lower back analysis at the original workstation—retrieving the component.

Managers and workers should regularly monitor and assess lower back load in the workplace and take measures to prevent and mitigate the risk of injury if necessary. Such measures should include ergonomic adjustments to work procedures, appropriate worker training, and the implementation of safety protocols.

Based on data from the ergonomic analyses of mannequin movements, there were identified shortcomings at the workstation that caused excessive worker strain. The main issues were associated with retrieving components from the Euro pallet, opening and closing the upper left clamp, handling the tool, and returning components to the Euro pallet. When the Euro pallets are in the lower positions, the worker must bend deeply, which negatively impacts the spine. Conversely, the insertion tool is positioned very high, which also results in excessive strain. Such conditions can lead to rapid fatigue and a decrease in both productivity and work quality. To address these problems, it is necessary to implement measures to improve the ergonomics of work procedures and the work environment. The goal is to eliminate these issues and create a safe and healthy workplace that supports worker well-being and productivity.

The fundamental principles of ergonomics are crucial for improving the work environment and preventing excessive worker strain. After identifying the shortcomings, there were proposed four measures to improve the workstation and subsequently created a simulation of worker movements and activities at the modified workstation, performing ergonomic analyses to verify whether improvements were achieved.

The first measure involved placing a platform under the pallets, so that the worker would not have to bend when retrieving or placing components. The platform, with the same dimensions as the pallets and a height of 50 cm, was designed so that the point where the worker picks up the component would be at hand level. The next measure involved placing the insertion tool lower, on the right side of the workstation, so it would be easily accessible and comfortable to manipulate. The third measure involved changing the handling of the upper left clamp so that the worker would perform this operation with the left hand, thus minimizing the load on the right shoulder and spine. Finally, to further improve worker comfort and safety, we proposed the placement of an industrial mat in front of the machine. This mat has a bubble surface, which reduces fatigue and promotes blood circulation in the worker’s legs.

The simulation of applied improvement suggestions with the new ergonomic assessments with the same methods was performed, but because of paper range limitation only results without pictures and detailed description are presented (see Table 2). The result of the Static Strength Prediction (SSP) analysis cannot be expressed in a single number because it is a complex biomechanical analysis that evaluates multiple aspects of physical exertion. Thus, in the table are data for Hip as a percentage of a working population that has the capability to perform a task.

Table 2.

Results of assessment before and after the application of measures.

As it is possible to see, alongside the improvement in RULA and OWAS, by using the same measures improvement in SSP was achieved too.

4. Discussion

The study introduces a systematic, stepwise digital procedure—combining 3D modeling, virtual human simulation, and four complementary ergonomic assessment tools (RULA, SSP, OWAS, and Lower Back Analysis)—which can be integrated into the early design stages of industrial workstations. This methodological contribution provides a replicable workflow that merges human-centered design with data-driven sustainability assessment.

The results of this study demonstrate that the use of digital simulation and a systematic ergonomic approach can bring substantial improvements to the design and daily functioning of industrial workstations. By working with digital human models and simulation software, it was possible to gain a detailed overview of the physical demands placed on workers. This level of analysis made it possible not only to pinpoint the tasks and areas with the greatest ergonomic risk, but also to design and test practical adjustments that had a real and measurable impact on the well-being of employees.

A major benefit of these interventions was the noticeable decrease in physical strain on the musculoskeletal system, as was evident from the comparative analysis of ergonomic indicators before and after the changes. Simple modifications, such as raising the height of pallets, rearranging tools, and placing industrial mats at key locations, proved highly effective in reducing overall fatigue and discomfort. These improvements help foster a healthier work environment and are likely to lead to fewer injuries and higher levels of satisfaction among workers.

From an economic standpoint, these changes are beneficial not only for employees but also for organizations. Lower rates of workplace injuries result in direct savings on medical costs and compensation, as well as indirect savings from fewer lost working days and lower turnover. In the long run, companies benefit from having a healthier, more stable, and more productive workforce.

Moreover, the use of digital simulation tools during the planning and design stages led to significant resource and cost savings. Because potential problems could be detected and solved virtually, it was possible to avoid multiple rounds of physical prototyping and expensive trial-and-error modifications. This made the entire process of improving the workplace faster and more efficient, with minimal material waste.

The results of this project also illustrate how ergonomics and sustainability are closely linked. Workplaces that are designed with employee health in mind are not only safer, but more sustainable in terms of maintaining the employability and productivity of the workforce. Preventing injuries reduces the need for healthcare resources and helps build a more resilient and sustainable company. The use of digital tools also contributes by reducing material and energy consumption in the development process.

Social sustainability was another important aspect of the changes introduced. The redesigned workplace is more accessible for a broad range of employees, including older workers and people with different physical abilities. Creating a more inclusive environment helps organizations attract and retain a wider talent pool and supports a culture of equality and support.

An additional strength of the digital approach is the flexibility it offers. Companies can quickly adapt workstations to new production demands, changes in workforce demographics, or evolving regulations without major disruptions or costs. In the fast-changing industrial sector, this kind of adaptability is crucial for maintaining competitiveness.

To sum up, the application of digital simulation and ergonomic principles in this study has shown to be a practical way to improve not only working conditions and operational outcomes, but also the economic and social sustainability of manufacturing organizations. These findings suggest that similar methods can be successfully implemented in a wide variety of industrial settings with positive results for both employees and employers. Despite these benefits, there are some limitations and ideas for future research, which are described below.

Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of the practical application of such analyses are the availability of software and experts capable of working with this software, especially in the SME sector, which cannot afford for financial and capacity reasons.

A further limitation stems from the limitations of the methods themselves and their areas of application, e.g., OWAS does not take into consideration the rhythm of the occurrence of different work postures, nor the impact of maintaining work postures over time etc.

Future research can be focused on longitudinal studies comparing digital predictions with observed ergonomic improvements and integration of AI-driven posture recognition for real-time feedback.

5. Conclusions

In contemporary manufacturing processes, workplace ergonomics plays a crucial role, particularly in increasing productivity and improving working conditions for employees. The fundamental objective is to create an optimal workstation that is not only productive and safe but also minimizes fatigue and the risk of workplace injuries. The aim of this study was to propose improvements to a specific workstation through its thorough analysis.

The first step involved a detailed examination of the selected work area, including its individual components and work tasks. Subsequently, a digital model was created in the Tecnomatix Jack ergonomic software and the individual work procedures were analyzed using ergonomic assessment methods. Based on the results of these analyses, we proposed specific measures to improve working conditions.

The goal of the study was to design measures that could positively impact and enhance the working conditions at the given workstation. By comparing the analyses of the original and modified workstations, we were able to evaluate the success of the proposed changes. It is essential that employees have good working conditions and a safe work environment that minimizes excessive strain, stress, and fatigue. For employers, investment in such conditions pays off not only through increased productivity and quality, but also through reduced workplace injuries and improved overall employee satisfaction. Simulation can be a significant tool not only in designing new workstations but also in improving existing working environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and P.M.; methodology, A.M. and O.Y.; software, A.M. and O.Y.; validation, P.M. and N.D.; formal analysis, N.D.; investigation, P.M.; resources, N.D.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, P.M.; visualization, P.M.; supervision, N.D.; project administration, P.M. and N.D.; funding acquisition, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic (Project KEGA 003EU-4/2025, VEGA 1/0064/23, VEGA 1/0238/23, KEGA 003TUKE-4/2024 and VEGA 1/0383/25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ojstersek, R.; Javernik, A.; Buchmeister, B. Importance of sustainable collaborative workplaces–simulation modelling approach. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2022, 21, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, I.; Khabibullin, R.; Belyaev, E.; Mavrin, V.; Verkin, E. Creating a safe working environment via analyzing the ergonomic parameters of workplaces on an assembly conveyor. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Systems Management (IESM), Seville, Spain, 21–23 October 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 947–954. [Google Scholar]

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Blanco-Fernandez, J.; Sandoval-Quintanilla, J.D.; Jiménez-Macías, E.; García-Alcaraz, J.L. Work standardization and anthropometric workstation design as an integrated approach to sustainable workplaces in the manufacturing industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Reyes, M.; Gil-Samaniego-Ramos, M.; González-Angeles, A.; Mendoza-Muñoz, I.; Navarro-González, C.R. Novel ergonomic triad model to calculate a sustainable work index for the manufacturing industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Legg, S.; Brown, C. Designing for sustainability: Ergonomics–carpe diem. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Šimic, M.; Pipan, M.; Herakovič, N. Multi-criterial algorithm for the efficient and ergonomic manual assembly process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płaza, G.; Kabiesz, P.; Thatcher, A.; Jamil, T. Ergonomics/Human Factors in the Era of Smart and Sustainable Industry: Industry 4.0/5.0. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2025, 33, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohezar, S.; Jaafar, N.I.; Akbar, W. Ergonomics, safety and physical work environment in sustainable-oriented workplace design. In Achieving Quality of Life at Work: Transforming Spaces to Improve Well-Being; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Adiga, U. Enhancing occupational health and ergonomics for optimal workplace well-being: A review. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2023, 24, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, L.; Palomba, I.; Merati, F.A.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R. Design of human-centered collaborative assembly workstations for the improvement of operators’ physical ergonomics and production efficiency: A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajšek, B.; Draghici, A.; Boatca, M.E.; Gaureanu, A.; Robescu, D. Linking the use of ergonomics methods to workplace social sustainability: The Ovako working posture assessment system and rapid entire body assessment method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, L.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R.; Matt, D.T. Safety, ergonomics and efficiency in human-robot collaborative assembly: Design guidelines and requirements. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K.; Hoffmann, T. Ergonomic Interventions in Shaping the Sustainable Development of Organizations; Scientific Papers of the Silesian University of Technology, Organization and Management; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanain, B. The role of ergonomic and human factors in sustainable manufacturing: A review. Machines 2024, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchmann, T.; Mies, A.; Neukirchen, T.; Gold, S. Tensions in sustainable warehousing: Including the blue-collar perspective on automation and ergonomic workplace design. J. Bus. Econ. 2021, 91, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wilde, P. Building performance simulation in the brave new world of artificial intelligence and digital twins: A systematic review. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Abbey, A.B.N.; Onukwulu, E.C. A conceptual framework for ergonomic innovations in logistics: Enhancing workplace safety through data-driven design. Gulf J. Adv. Bus. Res. 2024, 2, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. Optimizing Workplace Performance and Reducing Ergonomic Risks Through Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). Master’s Thesis, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, Edwardsville, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Palomba, I.; Gualtieri, L.; Rojas, R.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R.; Ghedin, A. Mechatronic re-design of a manual assembly workstation into a collaborative one for wire harness assemblies. Robotics 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, K. Modelling Sustainable Organizational Development and the Scope of Ergonomic Interventions. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, S. Digital optimization, green R&D collaboration, and green technological innovation in manufacturing enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, G.; Muzi, F.; Tiburcio, V.A. Digital management methodology for building production optimization through digital twin and artificial intelligence integration. Buildings 2024, 14, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoroso, L.; Caffaro, F.; Tronci, M.; Fargnoli, M. Ergonomics and design for safety: A scoping review and bibliometric analysis in the industrial engineering literature. Saf. Sci. 2025, 185, 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Croq, M.; Hossein-Arabi, F.; Brunet, R.; Roquelaure, Y. Does Ergonomics Improve Product Quality and Reduce Costs? A Review Article. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, C.; Adams, C. Production Ergonomics: Designing Work Systems to Support Optimal Human Performance; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdous, M.A.; Delorme, X.; Battini, D.; Sgarbossa, F.; Berger-Douce, S. Assembly line balancing problem with ergonomics: A new fatigue and recovery model. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbat, I.; Ozmehmet Tasan, S. Ergonomics indicators: A proposal for sustainable process performance measurement in ergonomics. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemens PLM Software Inc. Jack Task Analysis Toolkit (TAT); Training Manual V9.0; Siemens PLM Software Inc.: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dassault Systèmes. Human Activity Analysis. User’s Guide; Version 5 Release 16; Dassault Systèmes: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).