Abstract

The rising demand for sustainability disclosure, the risks it entails, and the strategies firms employ to manage these risks represent a critical area of contemporary research. This research aims to investigate the impact of sustainability risk management (SRM) on a firm’s financial distress (FFD). In addition, it examines the influence of the firm’s financial performance as a moderator variable on this relationship. This research adapts a quantitative analysis to explore these relations based on a sample of 77 Saudi firms listed on the Tadawul stock exchange in 2023. It relies on the SRM score presented by Morningstar Sustainalytics, as it is considered one of the largest environmental, social, & governance (ESG) rating firms. While the direct relationship between SRM and FFD is statistically insignificant, the findings show a significant moderating effect of firm performance, especially for firms with medium SRM levels. This demonstrates the importance of organizational and contextual factors in the interplay between SRM and FFD. The research results have valuable insights for decision-makers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by providing more understanding about the importance of adopting a comprehensive risk management framework that includes sustainability risks. Adapting sustainability practices and risk management becomes essential for Saudi firms. Therefore, managers in Saudi firms should consider the firms’ profitability when implementing SRM strategies, as these may not consistently contribute to stability across all financial conditions.

1. Introduction

Investors, consumers, and other stakeholders have recently increased pressure on firms to improve their sustainability practices. In the stock market, many investors associate higher sustainability performance with higher returns and overall financial performance. Many scholars have supported this perspective by finding a positive relationship between sustainability practices and the firms’ financial performance [1,2].

Previously, firms disclosed their sustainability practices voluntarily. With the increased interest in sustainability practices, several regulatory bodies, such as the Stock Exchange Commission (SEC) and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), are requiring firms to mandatorily disclose their sustainability performance. The firms should specifically disclose how they identify, assess, and prioritize their risk strategies as well as how they manage and monitor those risks at the entire firm [3].

As firms strive to improve their sustainable development performance, they face numerous risks related to all dimensions of sustainability that require efficient risk management characterized by an integrated strategic orientation. The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) issued an internal control structure and subsequently made amendments to the previous framework. Accordingly, it developed the integrated risk management framework known as Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) [4,5]. Sustainability risks should be embedded within this framework and managed in an integrated manner, reflecting a cohesive approach to sustainability risk management (SRM) [6].

In today’s highly complex business environment, FFD is one of the most serious risks, with significant repercussions both inside and outside the firm. It threatens the realization of the objectives of all stakeholders, including creditors, investors, customers, and others [7,8]. Due to these effects and repercussions, stakeholders need early warning indicators that predict FFD before the firm goes bankrupt. Furthermore, they need indicators regarding the firm’s financial and non-financial performance, internal control structure, and risk management system. There is a shortage of studies regarding the effectiveness of SRM and its influence on FFD.

The relevance of this research stems from the growing challenges faced by Saudi firms amid rapid economic transformation. Recently, firms in Saudi Arabia have encountered increasing exposure to FFD due to shifting regulatory requirements and intensified global competition. In a response to global pressures regarding sustainability, Saudi Arabia has outlined its Vision 2030 with a focus on sustainable development and economic diversification. Consequently, it is positioned as a regional leader in the shift toward sustainability.

Despite national efforts related to Vision 2030 to diversify the economy and enhance corporate governance, many firms continue to lack robust risk management frameworks capable of ensuring long-term stability. Since 2018, the Saudi Exchange (Tadawul) has been a partner in the United Nations sustainable stock market and has effectively promoted ESG practices along with awareness for listed firms. It collaborated with stakeholders to enhance sustainability disclosure across the Saudi capital market. To achieve these goals, it issued ESG guidelines aimed at helping firms disclose their sustainable practices. These initiatives reflect a broader commitment to sustainable market growth [9].

Disclosure of sustainability risks and their management practices is relatively new in the Saudi market, particularly following the amendment to the corporate governance regulations issued by the Capital Market Authority (CMA), 2023 [10]. This regulation motivates firms listed on the Saudi market to enhance disclosure transparency and risk management as essential factors for building investor confidence, along with providing a stable operating environment to achieve strong financial performance. These practices support their business continuity and long-term growth, in line with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 [11].

On the other hand, despite the importance of SRM, there is a lack of studies testing its direct impact on minimizing FFD risk. Some studies focused on the effect of ESG scores on FFD [12,13,14,15,16], while others tested the effect of ESG risk scores on FFD [7,17,18,19]. Furthermore, previous studies investigated the direct effect of financial performance on FFD [20,21,22,23]. There is a shortage of studies that have examined the moderating impact of financial performance on the relationship between SRM and FFD.

Moreover, prior research has examined how Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) serves as a comprehensive framework for addressing strategic and operational risks within a company to enhance its overall performance [4,5]. Although ERM and ESG frameworks contribute to increase awareness of regulatory risks and sustainability goals, SRM represents a distinct and integrated approach that specifically focuses on identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks associated with ESG [6]. This distinct approach suggests that SRM may influence FFD in ways that ERM or ESG frameworks do not address individually, underscoring the necessity for targeted empirical research.

Regarding investors’ pressures and regulation requirements to enhance sustainability practices, it remains unclear what levels of SRM actually exist in Saudi firms and whether these practices have a significant effect on FFD. Moreover, the potential for financial performance to moderate this relationship has not been sufficiently examined. Additionally, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, no prior studies have examined the relationship between SRM and FFD in the Saudi context. For example, Syed et al. (2023) [24] explored the determinants of FFD in Saudi firms. Meanwhile, Almubarak et al. (2023) [25] investigated the impact of sustainability practices’ disclosure on earning management in Saudi firms. Thereby, there is a need for more research in this area, specifically in Saudi Arabia.

This gap constrains our perception of how financial performance shapes the effectiveness of SRM. Therefore, this research addresses the following questions: What is the actual level of SRM in Saudi non-financial firms? Does SRM influence FFD? How does FFD affect this relationship? As a response to these theoretical and practical concerns, we investigate the role of SRM in mitigating FFD and explore how firm-level profitability may influence this relationship as well. Accordingly, this research provides insights not only into theoretical development but also into improving corporate resilience and financial performance in the Saudi context.

This research is conducted on a sample of 77 non-financial firms listed on the Tadawul in Saudi Arabia in 2023. The results show a statistically insignificant impact of SRM on the FFD. However, there is a significant effect of financial performance on the relationship between SRM and FFD for Saudi Arabian firms with medium SRM levels.

This research contributes to the accounting literature in several ways. Firstly, it is among the earliest to specifically investigate the influence of SRM on FFD, in contrast to the majority of the literature that examines the ERM or ESG frameworks. Secondly, it focused on exploring the effect of SRM to minimize the risk of FFD. Most of the previous studies examined the influence of ESG scores on FFD. Thirdly, it tests the direct impact of SRM on FFD as well as the moderating effect of financial performance on this relationship. Fourthly, it targets an emerging economy, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as it is one of the countries interested in implementing the highest sustainability practices and striving to achieve sustainable financial stability for all firms according to Vision 2030. Lastly, it assists decision-makers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by providing more understanding about the importance of adopting a comprehensive risk management framework that includes sustainability risks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review and hypotheses’ development. Section 3 describes research design and methodology. The empirical results are presented in Section 4. Section 5 provides the discussion. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conceptual Background

The term “sustainable development” appeared in the 1987 report of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. It relates to the concept of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. In 2004, the United Nations released a report titled Who Cares Wins. To divide the themes of sustainable development into three basic pillars, which are ESG [26].

Many firms and initiatives have contributed to the assessment of sustainability practices. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) reporting standard was developed to help firms understand the impacts of their business practices on issues such as climate change, human rights, and corruption. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) has also developed specific standards to help firms provide sustainability information to investors [27,28]. As a continuation of its efforts, the United Nations released the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework, which includes 17 goals. Many studies have built on this framework by dividing the SDGs into the three dimensions of ESG [29,30,31]. Others have divided them into five parts (known as 5 Ps), which are People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership [32,33,34,35].

Recently, interest in risk management has grown considerably, driven by several factors. These factors include the transformation of the perception of risk from a negative image to a kind of knowledge management, conflicting interests of stakeholders, and the rapid development of information technology. The dynamic nature of the business environment, together with the expansion of legislation and the requirement for mandatory risk management publications, has further reinforced the importance of effective risk management practices [36].

COSO’s risk management framework is widely recognized as one of the most extensively adopted approaches to risk management across diverse sectors. COSO defines risk management as a process conducted at the strategy level by the board of directors. It is designed to identify and manage potential risks within the firm in alignment with its risk appetite, thereby providing reasonable assurance of the firm’s ability to achieve its strategic objectives. By adopting a comprehensive and integrated approach to risk management, sustainability risks are embedded within a unified framework that consolidates ERM and ESG [37,38,39]. Sustainability risks should be embedded within this framework as a reflection of SRM [6]. SRM is defined as a description of how well a firm is mitigating its ESG exposure through suitable policies and initiatives and how these efforts are reflected in the actual firm’s ESG performance [40].

SRM and ERM are both critical frameworks for managing organizational risks. ERM adopts a comprehensive, organization-wide approach to identify and mitigate risks, including strategic, financial, operational, and compliance risks. SRM is specifically concerned with risks that arise from ESG issues. SRM deals with sustainability-related risks such as climate change, resource scarcity, and regulatory changes related to ESG standards. These risks, if unmanaged, can lead to reputational damage, regulatory penalties, and ultimately financial distress. In contrast, ERM provides a high-level risk governance structure that facilitates risk identification, assessment, mitigation, and monitoring across all risk domains.

Firms may implement SRM as part of their ESG strategy, embedding it into sustainability reporting and responsible investment practices. ERM, on the other hand, tends to be embedded in internal audit, compliance, and financial risk reporting functions. Despite their differences, the two frameworks are often interrelated, and the integration of SRM within ERM frameworks is increasingly recognized as essential for aligning risk oversight with sustainable value creation [6,38]. Table 1 summarizes the differences between ERM, SRM, and ESG.

Table 1.

Differences between ERM, SRM, and ESG.

Concerning financial challenges and distresses, there is no specific definition of FFD in the accounting literature. Gentry et al. (1990) [41] defined it as a situation where cash inflows are less than cash outflows. Some authors have categorized the characteristics of pre-bankruptcy firms into four basic stages. The first stage is a low rate of return on assets. The second stage is characterized by a low level of cash needed to meet current liabilities despite the firm achieving acceptable rates of profitability. The third stage is related to FFD, in which the firm suffers from financial issues, and if these issues are not addressed, the firm will move to the fourth stage of bankruptcy [42,43].

Undoubtedly, bankruptcy has many negative repercussions for the bankrupt firm itself in terms of its stakeholders, the stock market, and potential investors. It affects the business environment and consequently the economy. In other words, a firm’s exposure to bankruptcy goes beyond financial losses and extends to include economic and environmental losses. Therefore, it creates the need for indicators that reflect the risks of sustainable performance in all its dimensions, including financial, social, and environmental risks [19].

On the other hand, the firm’s performance reflects the financial health of the firm and measures its capabilities to achieve the short- and long-term objectives. The firm’s performance includes accounting indicators related to ratios extracted from financial statements, such as return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE). Other studies imply indicators of marketing performance, such as Tobin’s Q [44]. However, Yazdanfar & Öhman (2020) [45] employed the DuPont model to evaluate the firm’s performance. ROA is the most commonly used to measure the financial performance, specifically the profitability, of a firm [46,47,48].

Shortly, the conceptual framework underscores the progression of risk management that integrates sustainability considerations. The increasing adoption of ESG practices, especially within the Saudi context, forces firms to apply proactive risk management approaches. In the same direction, FFD is still a critical aspect because of its huge effect on the firm’s financial health. Financial performance plays the main role not only in signaling financial health but also in enabling firms to invest in effective risk management systems. These insights provide a conceptual framework for examining the effect of SRM on FFD. Additionally, investigate the moderating role of financial performance in this relationship.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

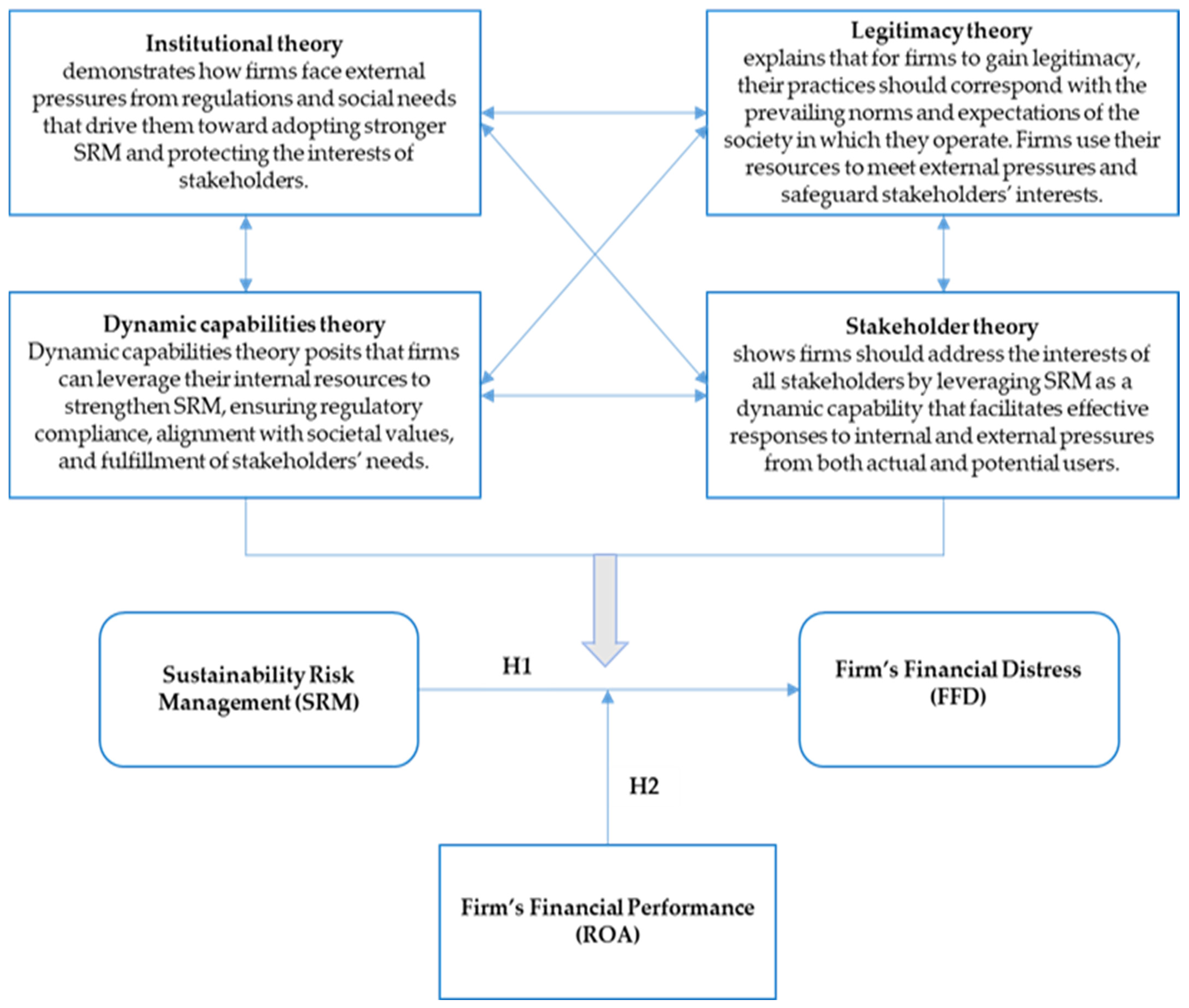

Designing the firm’s operations is not only based on efficiency, but there are also pressures from social institutions. The connection between SRM and FFD needs a multi-dimensional theoretical perspective that considers institutional-level perspectives, stakeholders’ interests, organizational legitimacy, and embedded capabilities. Four complementary theories—institutional, legitimacy, stakeholder, and dynamic capabilities theories—provide a strong basis for interpreting how SRM affects FFD. However, firm performance serves as a resource pool that supports the more effective implementation of SRM, which in turn helps to reduce FFD.

Institutional theory consists of three main dimensions. The first dimension is regulatory; it refers to regulations and laws forced by governments that firms must comply with. Normative is the second dimension; it includes values and norms, which form the firm’s behavior. Lastly, cognitive includes models and frameworks that the firm follows in its practices, such as ESG and professional standards [49]. In the same direction, the legitimacy theory focuses on the contractual relationship between firm and society. It addresses how society perceives and accepts the existence and activities of a firm, as well as the extent to which these activities align with various legitimate societal expectations. Accordingly, the disclosure of sustainability practices represents a critical component of the firm’s efforts to meet and comply with the legitimate demands of its surrounding community. Not meeting these requirements has a negative impact on the firm’s stability [49].

Sustainability reports are the primary communication channel between the firm and its society. It strengthens the firm’s ability to achieve its objectives, minimizes information asymmetry, and undoubtedly enhances the firm’s social legitimacy. A higher level of sustainability practices and performance is associated with a higher level of risk management [50]. The institutional and legitimacy theories are often linked in accounting literature, especially in the disclosure of a firm’s ESG practices [51,52].

Freeman (2010) [53] was the founder of the stakeholder theory. He argued that firms are influenced by numerous relationships and objectives, which significantly impact a firm’s performance. Therefore, management must consider these diverse objectives rather than focusing solely on maximizing shareholder profits. Stakeholders include customers, employees, suppliers, and legislative authorities. In a business environment, there will be events and risks that hinder the realization of these objectives [54]. Stakeholder theory focuses on reconciling the goals of stakeholders with the firm’s goals in a coherent context. Governance mechanisms, as a pillar of ESG, are adopted to mitigate agency costs and reconcile the conflicting interests of all parties. Therefore, this theory is linked to sustainability research in many studies [55,56,57].

Furthermore, this research adopts the dynamic capabilities theory to examine the research hypotheses. The business environment has recently witnessed radical changes resulting from the information technology revolution. The business environment is characterized by four basic characteristics: Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA). To address these changes, firms must adopt strategic concepts that enable them to analyze their internal resources and external environment along with their ability to act. The theory of dynamic capabilities fulfills these requirements [58].

In our research, we employ dynamic capability theory, as it is more suitable for our research objectives compared to the resource-based view theory. The resource-based view theory focuses on how a firm uses its various resources to create a competitive advantage. While dynamic capability theory emphasizes how a firm leverages its capabilities and competitive advantages to address environmental challenges [59]. Thus, the dynamic capabilities theory is more consistent with risk management in general and sustainability risks in particular.

Teece & Pisano (1994) [60] used dynamic capabilities terminology to explain competitive advantage. Dynamism refers to the transformation required by a firm to respond to environmental changes with time as the main constraint. However, capability refers to the ability to adopt modern methods and integrate internal and external skills and resources to face the environmental changes. Adopting dynamic capabilities helps firms increase their ability to set appropriate levels of risk management for those changes. It enables firms to survive in the market with the ability to seize opportunities that give them long-term competitive advantage and enhance their flexibility in responding to the dynamic changes they face internally and externally [61]. Risk management is a strategically integrated concept. It is considered a dynamic capability that manages risk, uncertainty, and environmental change to increase the firm’s ability to achieve its strategy and enhance performance [62]. Many studies have also found a positive correlation between adopting this theory and increasing the sustainable performance of firms [58,63].

In the rapidly changing regulatory and economic landscape shaped by Vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia, the connection between SRM and FFD can be effectively understood by integrating institutional, legitimacy, stakeholder, and dynamic capabilities theories. Complying with these regulations helps firms avoid sanctions and reputational risk, thereby reducing FFD. Moreover, legitimacy theory supplements this by stressing that Saudi firms are widely expected to exhibit socially responsible behavior. The adoption of SRM promotes the firm’s legitimacy, thereby boosting investor confidence. Stakeholder theory strengthens the relevance of SRM, as Saudi firms face increasing demands from government authorities and global investors for transparent and responsible risk management. Meeting these challenges results in stronger stakeholder relationships and enhanced business stability. Finally, dynamic capabilities theory illustrates how Saudi firms can develop SRM as an integral capability that empowers them to react to emerging sustainability threats, regulatory changes, and market uncertainties.

In summary, the theoretical framework section integrates four complementary perspectives to explain the firm’s behavior in relation to SRM and FFD. Institutional theory gives an understanding of how external regulations like Vision 2030 force Saudi firms to adopt SRM. In the same context, legitimacy theory supports the previous idea that firms implement SRM to protect their reputation among stakeholders. While stakeholder theory underscores a firm’s duty to protect the interests of various stakeholders, it also highlights the importance of risk management and corporate governance. Lastly, dynamic capabilities theory highlights the internal capacities firms must manage to effectively mitigate risk to achieve a competitive advantage and increase their value. Together, these theories justify the research’s hypotheses and explain the effect of SRM on financial distress in Saudi firms.

2.3. Hypotheses’ Development

2.3.1. Sustainability Risk Management and Firm’s Financial Distress

Concerning the relationship between risk management, particularly when it is implemented through a holistic framework, and the rate of exposure to FFD, some researchers focused on the firm’s adoption of risk management in general with FFD [43,64]. While other researchers focused on analyzing the level of risk management in terms of being high or low and its relationship with reducing the firms’ exposure to FFD [65,66,67].

The business environments and industry sectors of interest to the researchers also varied. For example, Lundqvist & Vilhelmsson (2018) [66] focused on the financial sector for international banks from different countries. Al-Amri & Davydov (2016) [65] and Purnanandam (2008) [67] examined a large sample of non-financial firms listed on the COMPUSTAT & CRSP database. Luthfiyanti & Dahlia (2020) [43] tested the relationship through the retail sector for listed firms on the Indonesian stock market.

Some scholars found an inverse relationship between risk management and FFD [65,66]. Al-Amri & Davydov (2016) [65] indicated a negative association, whereas those firms with an average level of ERM implementation were able to reduce 63% of operational risk events and reduce operational losses by 35%. While González et al. (2020) [64] found a statistically insignificant relationship between ERM practices and FFD. Contrary to expectations, other researchers found a positive relationship [43,67]. Luthfiyanti & Dahlia (2020) [43] found a positive relationship between risk management and FFD. They argued that Indonesian firms are still in the early stage of ERM. Accordingly, ERM practices have not yet resulted in significant mitigation of FFD. In the same direction, Purnanandam (2008) [67] reached a positive (negative) relation between FFD and risk management for moderately (highly) distressed firms.

However, some researchers have adopted the opposite perspective of risk management by examining the impact of the presence of a specific risk (unmanaged risk) on FFD [68,69]. For example, Liu et al. (2023) [68] pointed out that high-risk Chinese firms are more prone to FFD. In the same context, Vuong et al. (2024) [69] examined the relationship between volatility risks of stock return and FFD based on a sample of Vietnamese firms. The results indicated that firms with more volatile stock returns are more likely to experience FFD. Similarly, other researchers used ESG risk scores [7,17,18,19]. Cohen (2023) [70] found that environmental and social risk scores increase the FFD. Antunes et al. (2023) [7] relied on samples from different countries to test the relationship between ESG risk score and FFD. American firms represented 85% of the total sample, while the remaining sample represented firms from different countries listed on NASDAQ. They found that firms that hold ESG risk scores were less exposed to FFD.

In this context, some studies examined the impact of risk management on FFD, while others examined the impact of the ESG score as an indicator of the effectiveness of SRM on FFD [71]. Thus, this relationship has been of interest to many researchers [12,14,72,73]. Most studies have found an inverse relationship, where the higher the ESG score, the lower the risk of FFD [13,15,71]. However, Bouattour et al. (2024) [12] and Lohmann et al. (2025) [72] identified a non-linear relationship between ESG score and FFD. On the contrary, Seefloth et al. (2025) [14] found a positive relationship, as the higher the firm’s sustainability performance, the greater the firm’s exposure to FFD. On the other hand, Singh et al. (2024) [73] pointed out that there is no significant relationship between them. Ding et al. (2024) [18] tested the impact of sustainable performance on credit and FFD using a sample of firms listed on the Taiwanese stock market. They used several indicators that reflect the three dimensions of sustainable performance. They found inconsistent results between indicators of each dimension and FFD.

The previous inconsistencies show the necessity to examine this relationship further in various economic contexts. For Saudi firms, economic diversification and governance regulation, such as Tadawul guidelines for sustainability practices, are implemented for all listed firms. Therefore, effective risk management, especially SRM, may play a vital role in protecting firms from financial crises. The negative relationship between SRM and FFD can be explained well by integrating institutional, legitimacy, stakeholder, and dynamic capabilities theories in the context of Saudi Arabia. From an institutional lens, Saudi firms are facing rising regulatory pressures to adopt sustainability practices in line with Vision 2030. Aligning with these institutional edicts through SRM reduces exposure to the likelihood of distress risk. Legitimacy theory further indicates that SRM promotes a firm’s social acceptance and alignment with national sustainability goals. This perceived legitimacy enhances trust among key stakeholders and supports financial stability.

Consistent with stakeholder theory, Saudi firms must respond to rising concerns among regulators, investors, and society at large about environmental and social risks. SRM serves as a key mechanism through which firms can uphold this responsibility by safeguarding diverse stakeholder interests while maintaining financial stability. Conversely, inadequate risk management increases firms’ exposure to financial distress, thereby threatening stakeholder interests. Accordingly, SRM can be viewed as a mitigating mechanism against the likelihood of financial failure and FFD [67]. Lastly, dynamic capabilities theory considers SRM as an organizational capability that empowers firms to anticipate and recover from ESG-related risks. Firms that invest in SRM develop higher flexibility in facing external shocks, minimizing their exposure to financial instability. This ex-ante risk management enhances the firm’s ability to deal with downtime and uncertain circumstances. Thus, it reduces FFD and enhances the firm’s stability.

Collectively, these four theoretical lenses provide a holistic interpretation of why SRM is expected to reduce FFD in the Saudi context. We argue that effective SRM helps firms anticipate and address the environmental and social challenges, thereby reducing the likelihood of FFD. While empirical outcomes vary, possibly due to contextual factors such as implementation level of SRM, country, firm size, and regulatory environment, the literature provides mixed results. Although some studies indicate a positive relationship or no relationship, the majority support a negative relationship between risk management and FFD. Based on this rationale, the first hypothesis is formulated to predict a negative relationship between SRM and FFD. Therefore, it is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

The SRM has a significant negative effect on FFD.

2.3.2. Firm Performance, Sustainability Risk Management, and Firm’s Financial Distress

The impact of firm performance on FFD has been the focus of many researchers. Some have been interested in studying this relationship in financial institutions [20,21,22,23]. Other studies have focused on non-financial firms [48,74,75]. Yazdanfar & Öhman (2020) [45] focused on several sectors. Most researchers have found a negative impact of firm performance on FFD [47,76,77,78]. On the contrary, some authors have found a positive relationship between firm performance and exposure to FFD [46,79]. However, Sehgal et al. (2021) [75] and Cao et al. (2024) [80] found a statistically insignificant relationship between these two variables. Additionally, the relationship between firm performance and exposure to FFD has been examined in many business environments, like Southeast Asian countries [23,77,78], European Union countries [20,79], American [22], and British [48] environments. Emerging economies have also contributed to the exploration of this relationship. For example, Sehgal et al. (2021) [75] tested this relationship in India. In contrast, Isayas (2021) [76] and Kebede (2024) [47] applied their studies in Ethiopia.

In the context of this research, Wu et al. (2024) [81] conducted a comparative study between American and Chinese firms. They examined the impact of financial flexibility on FFD as well as the moderating impact of financial performance on this relationship. In fact, the concept of financial flexibility implies the efficiency of risk management, as it relates to a firm’s ability to provide external sources of financing and its ability to deal with uncertainty and unexpected events [82,83]. The results indicated that financial flexibility reduced FFD, and there is a significant effect of financial performance on this relationship in US firms compared to Chinese firms.

Regarding the Saudi business environment, there is a rarity of studies that investigate this relationship. Neither the direct investigation of the effect of SRM on FFD nor the moderating role of financial performance has been examined in prior research. However, some researchers examined the influence of other variables on FFD; Syed et al. (2023) [24] analyzed some financial ratios as determinants of FFD in Saudi firms. The results indicated that leverage, liquidity, and efficiency ratios are the most important determinants of FFD. In the same context, Almubarak et al. (2023) [25] investigated the impact of ESG score on earnings management in Saudi firms and the moderating effect of FFD on this relationship. The results showed a positive relationship between sustainability performance and earnings management. Additionally, FFD positively in fluences this relationship. Moreover, Al-Shaer et al. (2025) [84] analyzed the relationship between firm risk and ESG performance, highlighting the moderating effect of female representation on the board. They used a sample of 5898 firms across 61 countries, including 20 Saudi firms. The results showed an inverse influence between firm risk and ESG performance, as well as an inverse effect of female representation on this relationship.

A review of the previous studies reveals a significant impact of financial performance on FFD [85,86,87]. Although integrated risk management is recognized as an effective tool to mitigate FFD and prevent bankruptcy, its influence may be contingent on other firms’ characteristics, particularly their profitability. Dynamic capabilities theory focuses on how a firm can achieve competitive advantages by combining the firm’s internal and external resources. Undoubtedly, having financial resources and achieving high profitability enables the company to seize opportunities that are more attractive. In other words, the most profitable firms are increasingly able to apply strategies and tools that help them achieve their various objectives.

Moreover, institutional theory indicates that the highest-performing firms are more highly visible and hence face greater institutional pressure to respond to emerging ESG regulations and sustainability standards under Saudi Vision 2030. Consequently, profitability strengthens a firm’s ability and motivation to fulfill these obligations via strong SRM practices. As per legitimacy theory, a financially successful firm is under greater stakeholders’ scrutiny. In this sense, profitability enhances the legitimacy-building potential of SRM, thereby reducing reputational and distress risks. At the same time, stakeholder theory confirms that profitable firms are more likely to maintain stakeholder trust, particularly when they are considered to be effectively managing their sustainability risks. Taken together, these theories support the assumption that company profitability enhances the effectiveness of SRM, making it a stronger barrier against FFD in the Saudi context. Consequently, we expected that the negative relationship between SRM and FFD could be stronger for firms with higher profitability [62,63].

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model; institutional theory describes how external environments push firms to compliance with regulations by implementing SRM strategies. According to legitimacy theory, firms operate within a social system and align with their norms and values. Adopting SRM strategies is considered a response to these requirements. On the other hand, stakeholder theory is balancing interests and reconciling conflicting objectives between parties inside and outside the firm by implementing an effective risk management system and external institutional oversight to preserve all these interests. The dynamic capabilities theory emphasizes a firm’s ability to reconfigure resources in response to sustainability-related risks. In the context of the research framework, a firm’s financial performance is assumed to play a moderating role in the relationship between SRM and FFD. Therefore, a firm’s performance addresses financial challenges and crises through effective SRM, with dynamic capabilities proving most impactful when supported by adequate financial resources generated from positive outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

For Saudi Arabia, sustainability reporting and governance mechanisms are gaining societal and regulatory importance. SRM is generally anticipated to decline FFD; the extent of its influence is contingent upon the firm’s financial performance. Firms with high financial performance typically have access to superior resources and greater operational capacity to implement a robust SRM. Moreover, they often respond more effectively to institutional pressures by allocating adequate resources to implement SRM. Their positive financial standing also enhances perceptions of legitimacy in ESG practices, thereby strengthening the benefits of SRM. Conversely, firms with lower financial performance face stakeholder-imposed resource constraints, which limit the effectiveness of SRM in mitigating FFD. Therefore, Saudi firms seek to effectively implement SRM to reduce their exposure to FFD. This evidence supports the moderating effect of financial performance on the relationship between SRM and FFD [49,50]. Accordingly, the second research hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

The financial performance has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between SRM and FFD.

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

This research employs empirical study to investigate how SRM affects FFD and the moderating role of financial performance in the significance and direction of this relationship. The population of this research consists of joint stock firms listed on the Saudi Tadawul market in 2023. We obtain financial data for the dependent and control variables from the published financial statements of firms listed on the Saudi Stock Exchange. However, information on the SRM levels of Saudi firms is sourced from Morningstar Sustainalytics (accessed on 5 January 2025), a widely recognized provider of ESG ratings and sustainability research. We rely solely on 2023, as SRM information was only available for that year. Similarly, Truant et al. (2017) [88] presented their study on sustainability based on 30 Italian firms in 2014.

Table 2 depicts the research sample details. The following criteria are considered in selecting the study sample: Firstly, the availability of data required to measure the study variables during 2023 through the Saudi Tadawul website. Secondly, firms with missing SRM information were excluded. Lastly, financial firms were excluded due to their distinct regulations and operational processes [89,90,91]. After applying the previous criteria, the final sample is 77 Saudi firms. Table 2 reflects the research sample. We used SPSS version 26 to conduct the necessary statistical analysis of the actual data collected from the financial statements and the Morningstar Sustainalytics website of the sample firms to test the research hypotheses.

Table 2.

Research sample.

Regarding the sample size, we have performed three analyses to examine the statistical power of research models. (a) A priori power analysis to assess statistical power using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software (b) the post hoc power analysis using the observed power data in the empirical results section. (c) a post hoc analysis to assess the statistical power of the research results using bootstrap methods in the empirical results section.

Table 3 shows the priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software for the three regression models estimated in the empirical results section. Table 3 presents a systematic analysis of statistical power, focusing on the necessary sample size to achieve adequate statistical power for detecting the expected effects. The table also includes information on the type of statistical test used in the analysis, input parameters, and output parameters. The analysis indicates substantial variation in the required sample sizes across the three models. The first model, characterized by the smallest effect size (f2 = 0.03), necessitates a larger sample of approximately 325–425 observations, depending on the targeted statistical power (1–β). The second model with a small effect size (f2 = 0.27) requires a medium-sized sample (61–76 observations), while the third model with a very large effect size (f2 = 0.71) requires a relatively small sample (34–40 observations).

Table 3.

A priori power analysis to assess statistical power using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software.

This variance reflects the inverse relationship between effect size and required sample size. Thus, the results show that a sample size of 77 observations significantly exceeds the minimum requirements for estimating second- and third-order regression models. Sample size is considered adequate for models with small to medium effect sizes, while it may not be sufficient to detect light effects, especially when the number of explanatory variables in the statistical model increases. These findings indicate that the research design of the second and third models contributed to exceeding the actual power level of 90% for small and medium effects, confirming the adequacy of the statistical methodology adopted. The practical significance of this analysis is that it provides a robust methodological justification for the sample size used in the current study and a reference framework for planning future studies. In addition to confirming the adequacy of the current sample, the analysis provides clear guidance on the sample sizes required for many potential research scenarios, making it a valuable tool for long-term research planning.

3.2. Variables’ Measurements

3.2.1. The Independent Variable

The independent variable is measured using data from Sustainalytics. It is one of the most respected organizations for ranking firms according to their sustainability performance and is relied upon by many scholars [7,95,96,97]. Morningstar Sustainalytics is interested in companies’ sustainability practices in terms of directly and positively achieving sustainable development goals. On the other hand, it provides information about ESG risk scores by highlighting the threats that hinder firms’ sustainability goals.

ESG risk score is divided into two main parts: exposure to sustainability risks and SRM. We focus specifically on the SRM component, as it represents a distinctive contribution, unlike many studies that have relied on the overall risk index. The SRM score for a firm is derived from a set of management indicators (e.g., policies, management systems, certifications) and outcome-focused indicators (e.g., CO2 emissions or CO2 intensity). The risk management score is categorized into five ordinal levels: 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100 [40]. In other words, this score provides one value for each level; therefore, it is considered a categorical variable rather than a continuous variable. For example, a score of 100 (level 5—very strong) reveals that the firm has adopted a very strong policy. A score of 75 (level 4—strong) reflects that the firm has implemented a strong policy. A score of 50 (level 3—adequate) indicates that the firm has implemented an adequate policy, while a score of 25 (level 2—weak) reflects a weak policy. Finally, a score of 0 (Level 1—No Policy) shows that the firm has no SRM policy in place.

Our sample does not indicate Saudi firms belonging to the first or last levels of SRM. Specifically, the second (strong), third (adequate), and fourth (weak) levels were obtained. For the purposes of simplification, we refer to these levels as high, medium, and low, respectively. Accordingly, SRM is measured as an ordinal categorical, since ordinal variables are considered a subset of categorical variables or are inherently categorical by nature. SRM takes the distinct values 3, 2, and 1 for high, medium, and low levels, respectively.

The independent variable with its levels is treated as a factor variable in general linear models. For the purposes of estimating regression models based on general linear models, univariate analysis automatically converts the independent categorical variable into a set of dummy variables coded as 0 or 1. The number of dummy variables equals the number of levels of the categorical variable minus one, with one level serving as the reference group. Specifically, the lowest group of SRM is treated as the reference group because it is the group that contains the largest number of firms. When the number of observations across each level of the categorical variable is unequal, it is advisable to select the reference group from the level that has the largest number of firms.

3.2.2. The Dependent Variable

The dependent variable FFD is a continuous variable. It is measured by Z score according to the model of Altman (1968) [98] to predict financial distress. It is the most common and widely used by researchers [13,72,99]. It depends on five main financial ratios: working capital, profitability, leverage, retained earnings, and sales ratio. It reflects the discrepancies between a firm’s financial position and its income statement to predict the risk of financial distress. The following equation presents the measurement of this variable:

Z-Score = [0.012 (working capital/total assets) + 0.014 (retained earnings/total assets) + 0.033 (EBIT/total assets) + 0.006 (market value of equity/total debt) + 0.999 (sales/total assets)].

According to this metric, a company with a Z-score exceeding 2.67 is classified as healthy, whereas a Z-score below 1.81 implies a heightened probability of bankruptcy. Z-scores between 1.81 and 2.67 indicate potential bankruptcy. As the Altman Z-score measures financial stability, the results will be multiplied by −1 to directly reflect the financial distress. This conversion allows for a more intuitive interpretation of the coefficient (higher score = greater distress). In brief, the transformation does not change the statistical attributes of the variable, but it ensures that the coefficient sign aligns with the common interpretation of ‘financial distress,’ thus avoiding potential misinterpretation by readers.

3.2.3. The Moderator Variable

Financial performance is the moderator variable. We use ROA as an indicator for profitability. It is calculated as the ratio of net income scaled by total assets [46,75,76]. This variable will be included in the regression equation as an explanatory variable. Additionally, it will be incorporated as a moderator variable by multiplying it with the values of the SRM. As we treat low-level firms as a reference group, the firms with high and medium levels will be treated as dummy variables taking the values one and zero when testing the moderating effect. The moderating role of financial performance ROA × High. SRM indicates the interactive effect of SRM and ROA variables for firms with high levels of SRM. While ROA × Med. SRM indicates the interactive effect of SRM and ROA variables for firms with medium levels of SRM.

3.2.4. The Control Variables

We employ five variables as control variables. It is generally recommended, particularly in studies with relatively small sample sizes, to limit the number of explanatory variables included in the statistical model. Maxwell (2000) [100] recommended, as a general guideline, that one explanatory variable be included for every ten firms or observations. Accordingly, the first variable is firm size, which is calculated by Ln total assets [13,16,45]. The second variable is the current ratio, which equals current assets divided by current liabilities [46,76,77]. The quick liquidity ratio, the third control variable, is measured by the sum of cash and accounts receivable divided by current liabilities [75]. The fourth variable relates to the company’s investments in fixed assets through the ratio of fixed assets to total assets [76]. Finally, the financial leverage ratio, which reflects the company’s debt structure, is measured by dividing total debt by total assets [45,46]. Table 4 depicts the measurement of all variables as follows:

Table 4.

Measurement of Variables.

3.3. General Linear Models

General linear models were applied because the independent variable is an ordinal categorical variable. These models allow for testing between-subjects effects using univariate analysis, which examines how the multilevel independent variable and other explanatory variables affect a dependent variable. For the purposes of estimating regression models based on general linear models, univariate analysis automatically converts the independent categorical variable into a set of dummy variables coded as 0 or 1. The number of dummy variables equals the number of levels of the categorical variable minus one, with one level serving as the reference group. Thus, we investigate the impact of SRM on FFD independently without the presence of control or moderator variables, as illustrated by the first regression model. The second regression model is concerned with analyzing the relationship between SRM and FFD in the presence of control variables. Lastly, the third regression model is concerned with testing the moderating effect of financial performance on the main relationship in the presence of control variables. However, SRM has three levels (high, medium, and low); the regression models do not include firms with a low level of SRM, as they are treated as a reference group.

whereas β0 represents the intercept, while β1, β2, β3, … β10 are the regression coefficients. FFD is firms’ financial distress. SRM denotes sustainability risk management. Firm size, current ratio, quick ratio, and leverage are the control variables. ROA refers to the return on assets as a separate effect of the moderating variable. ROA × High. SRM represents the interactive effect of ROA and SRM variables for companies with high levels of SRM. ROA × Med. SRM denotes the interactive effect of ROA and SRM variables for companies with medium levels of SRM. Finally, ε is the random error term that captures residual variation not explained by the model.

FFD = β0 + β1 High. SRM + β2 Med. SRM + ε

FFD = β0 + β1 High. SRM + β2 Med. SRM + β3 Firm Size + β4 Current Ratio + β5 Quick Ratio + β6 Asset Ratio + β7 Leverage + ε

FFD = β0 + β1 High. SRM + β2 Med. SRM + β3 Firm Size + β4 Current Ratio + β5 Quick Ratio + β6 Asset Ratio + β7 Leverage + β8 ROA + β9 ROA × High. SRM + β10 ROA × Med. SRM + ε

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for the research variables. The data includes the mean, standard deviation, the direction, and the level of significance of the correlation between those variables. It is found that the standard deviation value exceeded the mean value of some of the research variables, indicating the disparity in the values of these variables among the sample firms, which is a natural situation for a sample of firms belonging to different sectors and operational characteristics.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics & Correlation matrix.

For example, the mean and the standard deviation of FFD are −0.66 and 0.51, respectively. Additionally, the mean and the standard deviation are 0.05 and 0.22 for the high SRM level, while they are 0.38 and 0.49, respectively, for the medium SRM level. In terms of the interaction between FFD and SRM levels, the mean and standard deviation are −0.00 and 0.01, respectively, for ROA × High.SRM. Pertaining to ROA × Med.SRM, they are 0.03 and 0.06, and for the ROA × Low.SRM, they are 0.03 and 0.51, respectively.

Conversely, the standard deviation is lower than the means of some variables. For instance, for the low SRM levels, the mean and the standard deviation are 0.57 and 0.50; for the firm size, they are 22.36 and 1.59; for the current ratio, they are 1.97 and 1.57; for the leverage ratio, they are 0.44 and 0.21; and for the asset ratio, they are 0.37 and 0.25, respectively. These results reflect a high level of homogeneity in those variables. Table 3 shows a statistically insignificant correlation between the three levels of SRM and FFD. However, there is a significant negative correlation between ROA × Med. SRM and FFD. Similarly, ROA and leverage have a negative and significant impact on FFD. Furthermore, there is a significant positive connection between asset ratio and FFD.

On the other hand, the correlation analysis shows a strong negative correlation (−0.90) between Low SRM and Med SRM, which reflects the expected multicollinearity between these mutually exclusive dummy variables. Multicollinearity is not an issue in the regression models, since the two variables are not included together in a way that creates perfect multicollinearity; the reference group has been excluded from the models.

Table 6 presents the means, standard deviations, minimums, and maximums of the research’s variables according to the three levels of SRM. The results show that the mean of firm size is higher in firms with high levels of SRM compared to those with medium and low levels. The means of FFD, ROA, ROA × SRM, and leverage for firms with a medium level of SRM are higher than those of low and high levels of SRM. Furthermore, the means of the current, quick, and asset ratios are higher in firms with low levels of SRM compared to those with medium and high levels of SRM.

Table 6.

Descriptive analysis of research variables according to SRM levels.

The previous results indicate that a group of firms with a medium level of SRM have a high level of financial stability and financial performance. These results may justify their lack of keenness to improve their SRM level, at least in the short term. Thus, firms with medium levels of SRM may influence both the strength and direction of the relationship between SRM and FFD, as the mean value of ROA × Med. SRM is higher than those observed for firms with low and high SRM levels.

4.2. ANOVA Analysis

Table 7 depicts the results of the robust test of equality of means using Welch’s ANOVA. This test is used to determine the extent of significant differences in the mean values of the research variables across the three levels of SRM, at a 5% significance level. Welch’s ANOVA provides reliable results even if the assumption of homogeneity of variances is not met among the three subgroups of firms in the sample (firms with low levels of SRM, firms with medium levels of SRM, and firms with high levels of SRM).

Table 7.

Robust Tests of Equality of Means.

The results show that FFD, ROA, firm size, leverage, and ROA × SRM variables differed significantly between at least two of the three subgroups. Additionally, there are no significant differences in the mean values of other research variables across the three levels of SRM.

Table 8 presents the results of the ANOVA analysis using the Games–Howell test as one of the post hoc multiple comparisons tests. Particularly, it is designed to determine the extent of the significant differences, if any, in the means of the research variables across each pair of SRM levels, under the assumption of heterogeneity of variance among the three subgroups. The findings demonstrate significant variation in the means of certain variables across the different SRM levels at the 5% significance level.

Table 8.

Games–Howell test.

For example, FFD with medium levels of SRM is significantly lower than those with high levels, with a significant negative difference (0.36). The average FFD of firms with low levels of SRM compared to firms with high levels decreases by 0.23. Finally, the average FFD of firms with medium levels of SRM compared to the group of firms with low levels decreases by 0.13. In addition, the ROA of the firms with medium levels of SRM significantly increases by 0.07 compared to those with high levels of SRM. Moreover, the ROA of firms with low levels of SRM increases by 0.05 compared to those with high levels of SRM. Finally, the ROA of firms with medium levels of SRM decreases by 0.02 compared to the group of firms with low levels of SRM.

Continuing down the same path, the ROA × SRM of firms with medium levels of SRM increases by 0.15 compared to those with high levels of SRM. ROA × SRM of the firms with low levels of SRM increases by 0.06 compared to those with high levels of SRM. The ROA × SRM of the firms with medium levels of SRM significantly increases by 0.09 compared to those with low levels of SRM. These findings indicate that the influence of SRM on FFD is contingent upon enhanced financial performance in firms exhibiting medium levels of SRM. Thus, firms with a medium level of SRM and strong financial performance have more financial stability and have a greater ability to absorb financial shocks compared to firms with low levels.

Regarding the firm size, firms with medium levels of SRM are significantly larger than low–level firms, with a significant positive difference (1.40). As for the leverage ratio, it is significantly higher for firms with medium levels of SRM (0.14) than the same ratio for firms with low levels. Finally, the results regarding companies with high levels of SRM should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. Therefore, future research could address this issue by expanding the sample size once sufficient data on the level of SRM for Saudi firms becomes available.

As shown in Table 9, firms with low levels of SRM make up 57.10% of the total sample size, followed by firms with medium levels at 37.70%, and firms with high levels make up 5.20%.

Table 9.

Between–Subject Factors.

As presented in Table 10, Model (1) is statistically insignificant, since the p-value (0.32) exceeds 0.05 and the F-value (1.17) is below the critical threshold at the 5% significance level. Thus, SRM levels have an insignificant influence on FFD. These results are consistent with Aguinis & Glavas’s (2012) [101] and Eccles et al.’s (2014) [102] findings. They explained the statistically insignificant influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable because of the decrease in the explanatory power of the model.

Table 10.

Tests Between Subjects Effects.

In line with Aguinis & Glavas (2012) [101] and Eccles et al. (2014) [102], we believe that the statistical insignificance of that model and its low explanatory level may be due to the lack of inclusion of the control variables and the moderating variable in this model. This shortage is addressed in the second and third models. Additionally, early implementation of sustainability practices is noted in the research sample, while the returns of this implementation are achieved in the medium or long term.

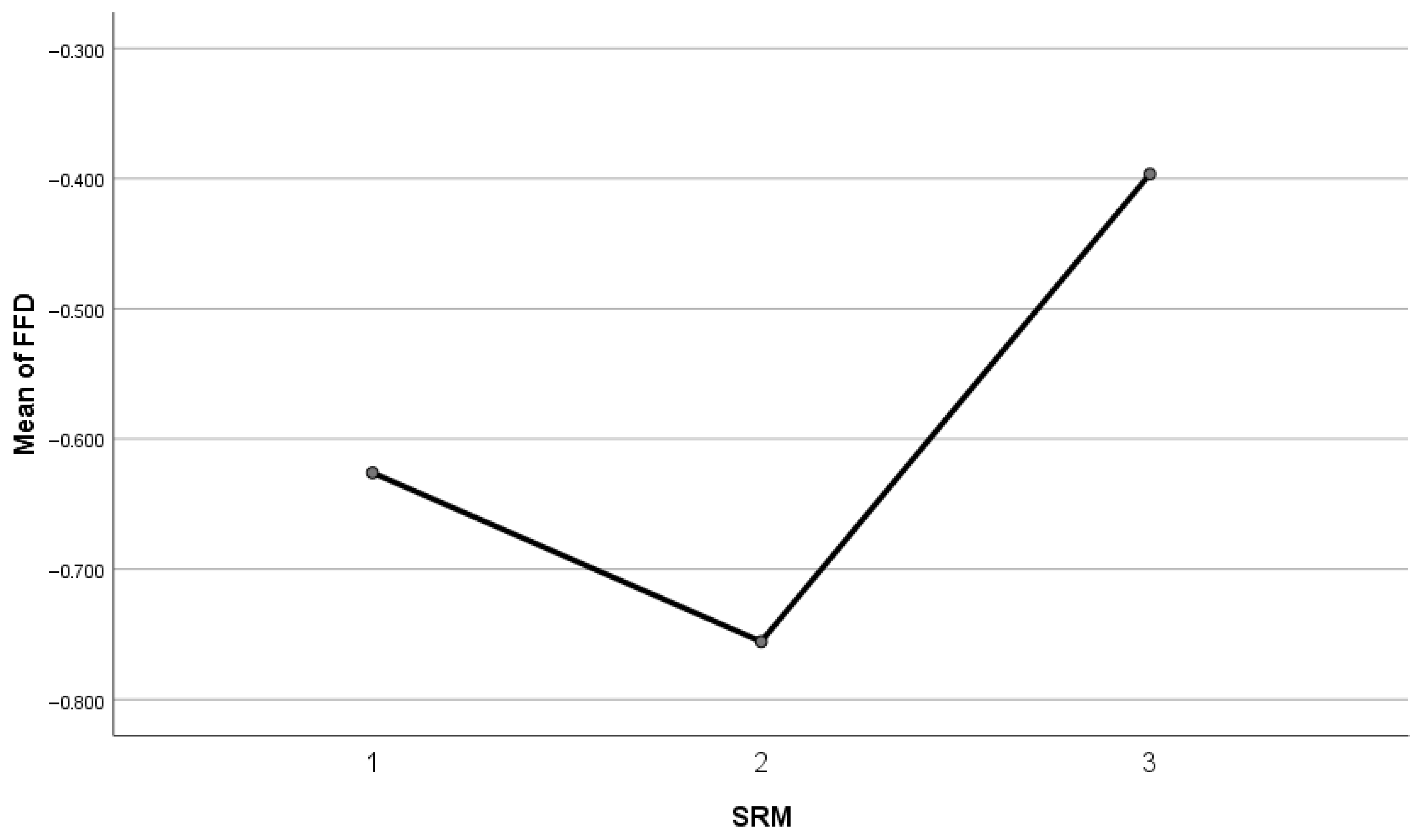

Similarly, the low adjusted R2 in Model (1) may be attributed to the model’s insignificance, the low F-value, the non-linear relationship between SRM levels and FFD (as depicted in Figure 2), and the exclusion of control and moderator variables. For example, Wang et al. (2008; 2016) [103,104] and Barnett & Salomon (2006; 2012) [105,106] concluded that in a similar context, the relationship between environmental–social performance and financial performance was non-linear but U-shaped.

Figure 2.

The relationship between the level of FFD and SRM for all firms.

Figure 2 presents the results derived from ANOVA analysis. It depicts a non-linear relationship between the level of SRM and the level of FFD. The level of FFD decreases for the firms with low levels of SRM. The level of FFD reaches its lowest point among firms with medium levels of SRM, after which it starts to rise for firms with high levels of SRM. Moreover, the figure shows companies with low levels of SRM direct their efforts toward managing their available resources to maximize profits and reduce their expenditure on sustainability activities, which in turn decreases their FFD.

Additionally, firms with medium levels of SRM exhibit the lowest level of FFD, suggesting their ability to strike an optimal balance between generating returns and SRM. On the one hand, these firms benefit from attracting sustainability-oriented investors and customers who value responsible brands. Furthermore, they reduce long-term costs by maintaining sustainability risks at a manageable level, thereby avoiding regulatory penalties, potential shutdowns, and unnecessary operational disruptions. Conversely, firms with high levels of SRM demonstrate the highest degree of FFD, which may be attributed to the fact that the financial benefits of extensive SRM often materialize over the medium to long term rather than immediately [107]. Such firms may deliberately accept weaker short-term outcomes in anticipation of superior long-term financial performance.

These results are consistent with some studies’ findings [103,104]. For example, Wang et al. (2016) [104] found that firms with low levels of corporate social report (CSR) performance are unable to exploit their CSR activities to achieve tangible financial benefits, but once these levels exceed a certain point, CSR performance will gradually turn into financial benefits that can offset the costs involved and improve their financial performance. Wang et al. (2008) [103] found that CSR practices positively influence a firm’s financial performance up to a certain threshold. However, beyond this threshold level, the benefits of additional CSR efforts diminish, leading to a plateau in financial performance, which may eventually decline as excessive CSR investments impose greater costs than returns. Thus, the results of Wang et al. (2008; 2016) [103,104] indicate that there is a non-linear U-shaped relationship between CSR practices and financial performance.

Continuing with Table 10, the F value is high (2.63), and the p-value is lower than 5% (Sig = 0.02) in Model (2). Similarly, the F value is high (4.66), and the p-value is lower than 5% (Sig = 0.00) in Model (3). A high F value indicates that the two models explain a significant portion of the variance in FFD compared to the amount of random error. Furthermore, it indicates that one or more of the variables included in the two models have a real effect on the level of FFD. The results for the two models also show the significant impact of firm size and leverage as control variables on the level of FFD. Finally, the results in model (3) also show the significant impact of ROA as a moderator variable on the SRM–FFD relationship for firms with medium levels of SRM.

In short, the results of model (2) imply that 13% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.13) in FFD is explained by the levels of SRM in the presence of the control variables. The results of model (3) show that 33% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.33) in FFD is explained by the level of SRM and the moderating variable in the presence of the control variables. Therefore, the two previous models have strong explanatory power for all variables. The stark improvement in model fit, evidenced by the adjusted R2 increase from 0.13 to 0.33, reveals that the moderating effect provides a vital explanatory tier that the basic model alone cannot capture. This stark support for our hypothesis highlights the theoretical and practical significance of the moderating variable in understanding the latent mechanism.

The previous findings suggest that the impact of SRM on the level of FFD is conditional on the improved financial performance of firms with medium levels of SRM. In other words, firms with an effective level of SRM and strong financial performance have more financial stability. This result means that SRM does not directly affect FFD. Therefore, firms with medium levels of SRM and higher profits have a greater ability to absorb financial shocks. Moreover, the findings indicate that financial leverage and firm size have a significant impact on the level of FFD. Consequently, firms should adopt an integrated strategy that combines SRM, robust financial performance, and a strong financial structure.

On the other hand, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 depict the results of the parameter estimates for general linear models (1), (2), and (3). For model (1), there is a statistically insignificant decrease in the level of FFD in firms with high levels of SRM by 0.23 compared to those with low levels of SRM (β1 = −0.23, t = −0.87, p > 0.05). Additionally, there is a statistically insignificant decline in the level of FFD in firms with medium levels of SRM by 0.36 compared to those with low levels (β2 = −0.36, t = −1.34, p > 0.05). However, β3 for firms with low levels of SRM is zero, because they are taken as the reference group.

Table 11.

Parameter Estimates for Model (1).

Table 12.

Parameter Estimates for Model (2).

Table 13.

Parameter Estimates for Model (3).

Additionally, as shown in Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13, the VIF values for all independent variables are below 10, indicating no issue of multicollinearity among them [108,109,110]. Using the observed power data, the post-hoc power analysis assesses the model’s ability to identify the real effect of the explanatory variables on FFD at the sample level, if this effect exists at the level of the overall population. Partial eta squared data determines the strength of the explanatory variables’ effect on the FFD. The higher the partial eta squared and observed power values (closer to 1), the stronger the explanatory variables’ effect at the population level. The observed power for High SRM and Med SRM in the three models and the ROA × High SRM in model (3) suggests limited capacity to identify their real effect on FFD. These are likely due to the small sample size, heterogeneity in firms’ operating characteristics, or the relatively low influence of these variables.

Caution should be exercised when interpreting our insignificant results, particularly for the High. SRM variable. The low statistical power associated with these analyses means that there is a non-negligible chance of a type II error (failure to detect a real effect). Hence, even though these variables did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in our study, we cannot firmly conclude that no meaningful relationship exists. Future research using larger samples is needed to draw more concrete conclusions about these effects.

In model (3), the observed power of the interactive effect of the ROA and SRM variables for firms with medium levels of SRM indicates the reasonableness of this model’s ability to identify the real effect of the moderator variable on the level of FFD for these firms, if such an effect exists at the level of overall population (observed power = 0.67; partial eta squared = 0.08; p-value < 0.05). As shown in Table 10, the observed power value for the leverage variable in model 2 is 0.55, with a partial eta squared of 0.06 and a p-value less than 0.05. Similarly, for the firm size variable in model 3, the observed power is 0.60 with a partial eta squared of 0.06 and a p-value less than 0.05. These values illustrate how well each model captures the true impact of leverage and firm size on the level of FFD within the research sample.

Finally, a post hoc analysis for statistical power is performed using the bootstrap method, as it is one of the best options for verifying statistical power in studies with limited samples. It also relies on repeated calibration of data to estimate the distribution of statistical parameters with greater accuracy. It provides more stable and reliable estimates, from which the actual statistical power of the study results can be inferred. Finally, the results of this analysis may provide a logical justification for the adequacy of the current study sample size and the generalizability of its results.

Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 present the bootstrap analysis, which contributed to improving the results related to the parameter estimates of the first model. Table 11 shows a notable improvement in the significance levels of all parameters in the first model, despite the stability of their estimated values as reported in the initial analysis. The results indicate a significant decrease in the level of FFD of 0.23 and 0.36 for firms with high and medium levels of sustainable risk management (SRM), respectively, compared to firms with low SRM levels. This finding contrasts with the results reported in the same table for the parameter estimates of the first model under the basic analysis, where these coefficients were not statistically significant (Model 1: β0 = −0.40, p = 0.00; β1 = −0.23, p = 0.03; β2 = −0.36, p = 0.02). Thus, the above results indicate that bootstrap analysis contributes to improving the efficiency of statistical estimates in small samples.

Furthermore, the bootstrap analysis presented in Table 12 and Table 13 largely confirms the parameter estimates for SRM variable [SRM, ROA, and ROA × SRM] in model (2) [model (3)]. While most coefficients are not statistically significant (e.g., Model 2: β0 = −1.73, p = 0.14; β1 = −0.09, p = 0.68; β2 = −0.22, p = 0.25; Model 3: β0 = −2.04, p = 0.09; β1 = 0.01, p = 0.97; β8 = −1.53, p = 0.08; β9 = 4.53, p = 0.62), the interaction term for medium SRM levels in Model 3 (β10 = −3.30, p = 0.04) remains significant, supporting the moderating role of ROA. It is also observed that the bootstrap analysis contributed to significantly narrowing the confidence intervals for the parameters of the model (1), as it is free of zero values, reflecting the ability of this method to provide more efficient and reliable estimates for small samples. These results were achieved at the 95% confidence level and were not affected by outliers or values that deviated from the assumptions of normal distribution in the data.

As shown in Table 12, for model (2), FFD is lower in firms with high SRM than in those with low SRM (β1 = −0.87, t = −0.31, p > 0.05). Firms with medium SRM levels exhibit a statistically non−significant decrease in FFD (−0.22) compared to firms with low SRM levels (β2 = −0.22, t = −0.83, p > 0.05). These findings reveal that the SRM levels have no statistically significant effect on FFD. Although the direction of the coefficients varies across SRM levels, all effects remain insignificant (p > 0.05), indicating that variations in SRM practices do not meaningfully influence FFD. On the other hand, model (3) findings demonstrate a statistically insignificant increase in the level of FFD in firms with high levels of SRM (β1 = 0.01, t = 0.04, p > 0.05) compared to those with low levels of SRM. Moreover, there is a statistically insignificant increase in FFD in firms with medium levels of SRM by 0.14 compared to those with low levels (β2 = 0.14, t = 0.55, p > 0.05). These findings do not support the first hypothesis, “The SRM has a significant negative effect on FFD”. These results may be explained by firms with a lower level of FFD implementing more rigorous and effective SRM procedures in response to financial crises. Meanwhile, financially stable firms rely on more effective measures to manage sustainability risk. Additionally, effective implementation of SRM requires specific characteristics of firms that enhance the firm’s financial stability. These results are consistent with some studies’ findings [107], while they differ from others [103,104].

Furthermore, these results could be theoretically interpreted based on institutional theory, indicating that firms may implement SRM in response to mimetic, normative, and regulatory constraints, resulting in compliance instead of genuine risk mitigation. Dynamic capabilities theory might indicate that SRM could enhance a firm’s ability to reconfigure, seize, and sense resources in response to financial risk exposure; however, the insignificant findings reveal that, in reality, SRM has not translated into a noticeable decrease in FFD. According to legitimacy theory, firms may adopt SRM practices to signal responsible governance and maintain legitimacy, without necessarily enhancing financial stability. On the other hand, stakeholder theory argues firms’ SRM initiatives, with more focus on mitigating ESG risks, may not adequately address stakeholders’ expectations for financial performance concerns. Overall, while SRM contributes to broader risk governance and strategic positioning, it does not appear to significantly influence firms’ susceptibility to financial distress.

Regarding the moderating role of ROA on the SRM–FDD relationship, model (3), as presented in Table 13, shows a statistically insignificant positive effect of ROA on the SRM–FFD relationship for firms with high levels of SRM, with a value of 4.53 compared to low-SRM firms (β9 = 4.53, t = 0.57, p > 0.05). Conversely, for firms with medium SRM levels, ROA exhibits a significant negative effect (−3.30) on the SRM–FFD relationship compared to low SRM firms (β10 = −3.30, t = −2.43, p < 0.05). These findings align with the patterns observed in Figure 2 and may reflect that Med.SRM firms with stronger financial performance tend to implement more robust SRM procedures to maintain financial stability compared to firms with low or high SRM levels. These results are consistent with some studies’ findings [102,104]. Eccles et al. (2014) [102] found that high-sustainability firms have better long-term performance compared with low-sustainability counterparts when using the accounting rate of return to measure firm performance. Wang et al. (2016) [104] found that exceeding a certain level of CSR performance is associated with improved financial performance when using the accounting rate of return to measure firm performance. According to the results of model (3), we suggest that the level of FFD may be affected by the firm’s short-term financial performance more than the level of SRM. As noted, SRM still has statistically insignificant effects, possibly because SRM may act as a protective factor to reduce the level of risk rather than a reinforcing factor directly increasing the level of financial stability. In particular, the results obtained under the estimation of model (3) indicate that financial performance plays a key role in strengthening the relationship between SRM and the FFD level. Consequently, firms should prioritize their SRM practices and financial performance to achieve sustainable growth.

Accordingly, the second hypothesis, “the financial performance has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between SRM and FFD,” is supported. As the significant interaction of ROA in the SRM–FFD relationship is observed for firms with medium SRM levels, indicating that financial performance shapes the extent to which SRM influences financial vulnerability. Theoretically, these findings may be interpreted from an institutional theory perspective: financially sound firms are more capable of complying with normative and regulatory expectations related to sustainability and risk governance. In line with dynamic capabilities theory, firms may better integrate SRM into strategic decision-making, improving their adaptive capacity to manage financial challenges. Legitimacy theory further argues profitable firms may leverage SRM to reinforce organizational legitimacy during periods of financial distress. Finally, a stakeholder theory indicates that firms with stronger financial performance are better positioned to allocate resources toward effective SRM practices that support stakeholder interests and enhance stability. Overall, these findings indicate that the effectiveness of SRM in mitigating FFD is contingent on firms’ financial performance.

5. Discussion

This research investigates the impact of SRM on FFD and the moderating role of financial performance on this relationship in Saudi Arabia. The results imply that the SRM has a statistically insignificant impact on the FFD. Thus, the first hypothesis is rejected. These findings are consistent with those of González et al. (2020) [64] and Singh et al. (2024) [73]. On the other side, they contradict the work of Al-Amri & Davydov (2016) [65] and Lundqvist & Vilhelmsson (2018) [66]. This result may also be explained by the non-linear relationship observed in Figure 2, suggesting that the effect of SRM on FFD is not uniform but varies with the level of implementation. In firms with low SRM, the process of risk management may be insufficient to affect financial results. Conversely, firms with high SRM may begin to realize financial benefits from its implementation. These contradictory effects may eliminate each other overall, resulting in a statistically insignificant net effect. This highlights the crucial nature of interpreting the influences of SRM in a segmented framework, rather than a linear relationship.

Conversely, the results indicated a significant influence of financial performance on the relationship between SRM and FFD for firms with medium SRM levels. Therefore, the second hypothesis is supported. Accordingly, these results confirm that firms with stronger profitability obtain more benefits in enhancing financial stability by implementing SRM. These results assist Saudi Arabian firms in sharing the realization of achieving the kingdom’s vision for 2030.

The statistically insignificant SRM–FFD relationship may be explained by the level of SRM practices within the sample. Since this level is still in its early stage, its impact on FFD is more likely to emerge in the medium to long term rather than in the short term. In addition, firms may apply SRM practices nominally, rather than with the aim of appeasing stakeholders or meeting minimum regulatory and mandatory requirements.