Abstract

This study proposes an analysis of the impact of farmers′ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of economic sustainability and barriers on organic farming implementation in Turkey’s Thrace region. Using a mixed-methods approach, data were collected from 400 farmers through surveys and analyzed using SPSS v27 The findings revealed that age, education level, land ownership, and organic farming training were significant predictors of adoption. Perceptions of economic sustainability positively influenced adoption, while perceptions of barriers had a negative effect. The qualitative findings identified certification costs, insufficient credit opportunities, and difficulties in accessing organic inputs as the most common challenges faced by farmers. The most requested forms of support included product purchase guarantees, financial aid during certification, and fertilizer–pesticide subsidies. This study provides a foundation for developing policies and programs to promote organic farming in Turkey, contributing to the country’s sustainable agriculture goals.

1. Introduction

Agriculture has played a fundamental role in meeting the basic needs of humanity and contributing to the economic development of societies since the dawn of civilization. However, modern agriculture now faces unprecedented challenges due to global issues such as rapid population growth, climate change, and the depletion of natural resources. These challenges necessitate a shift toward sustainable agricultural practices that balance food security with environmental protection [1,2].

Among sustainable practices, organic farming has emerged as a significant approach that minimizes the negative environmental impacts of agriculture while ensuring the production of healthy and safe food. Organic farming is defined as an agricultural system that avoids using synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Instead, it relies on techniques such as crop rotation, green manure, composting, and biological pest control. This approach not only preserves biodiversity and soil fertility but also meets the rising consumer demand for chemical-free and environmentally friendly products [3,4].

The global interest in organic farming has grown significantly in recent decades due to its potential to address environmental and health concerns while offering economic opportunities for farmers. For instance, organic farming systems have been shown to improve soil properties, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance ecosystem services [5]. Additionally, organic products often command premium prices on markets, providing an economic incentive for farmers to adopt this practice [6]. Despite these advantages, the adoption of organic farming remains limited in many countries, including Turkey, due to various barriers such as high certification costs, limited access to organic inputs, and insufficient financial support [2,3,7,8,9].

Turkey has significant potential for organic farming with its geographical location, climate diversity, and rich biological resources. Although organic farming practices have increased in the country in recent years, they remain at a limited level compared with conventional farming methods [7]. According to 2023 data, the total organic farming area in Turkey is approximately 225 thousand hectares [10]. This situation falls below the country′s potential and indicates a significant area for development in the widespread adoption of organic farming. The increasing global demand for organic products creates new market opportunities for farmers and potentially offers the chance to earn higher incomes [6]. Organic farming is important not only for environmental sustainability but also for economic sustainability [1].

However, farmers face various challenges in adopting and maintaining organic farming. Economic factors are at the forefront of these challenges [6]. The transition process to organic farming may involve economic uncertainties for farmers due to changes in production methods, certification costs, and potential yield decreases [11]. Especially during the transition period, farmers may face lower yields than conventional farming without being able to benefit from organic product price premiums. This situation can create a significant barrier to transitioning to organic farming [6]. The economic sustainability of organic farming is critical for farmers to adopt and maintain this method in the long term. Economic sustainability includes factors such as organic farming providing reasonable income for farmers, manageable production costs, and market acceptance of products [12]. A detailed understanding of the economic barriers to organic farming is of great importance for developing strategies to overcome these barriers. These barriers may include high production costs, marketing difficulties, lack of access to financial resources, and inadequate government support [6]. For example, the high cost of organic inputs can pose a significant challenge, especially for small-scale farmers. Additionally, difficulties in marketing and distributing organic products can prevent farmers from selling their products at appropriate prices.

In this framework, the present research examines the impact of the demographic characteristics of farmers in the Thrace region, as well as their perceptions of the economic sustainability and barriers of organic farming, on the implementation of organic farming. In addition, this research aims to reveal the economic challenges farmers face in starting and maintaining organic farming and to propose solutions to overcome these challenges. We sought answers to the following questions:

- i.

- How do demographic factors (age, gender, education level, farming experience, etc.) affect farmers′ organic farming implementation?

- ii.

- How do farmers′ perceptions of the economic sustainability of organic farming affect their organic farming implementation?

- iii.

- How do farmers′ perceptions of the economic barriers to organic farming affect their organic farming implementation?

- iv.

- What are the economic challenges farmers face in starting and maintaining organic farming, and what are the proposed solutions to overcome these challenges?

The Thrace region is one of Turkey′s important agricultural regions, with fertile lands where various agricultural products are grown. The geographical location, climate characteristics, and agricultural infrastructure of the region offer suitable conditions for organic farming. However, its widespread adoption in the region is still limited. This research aims to contribute to both the academic literature and practices by examining the economic dimensions of organic farming in Turkey from the farmer′s perspective. The findings are expected to form a basis for developing policies and programs that will support the widespread adoption of organic farming, contributing to Turkey′s sustainable agriculture goals.

This study focuses on analyzing the impact of perceptions of economic sustainability and barriers on the implementation of organic farming. The structure of the study is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the materials and methods, including data collection tools and analysis techniques. Section 3 presents and discusses the quantitative and qualitative findings of the research. Finally, Section 4 concludes the study by discussing the implications of the findings for organic farming policies and practices, along with recommendations for future research.

2. Related Work

The adoption of organic farming has been extensively studied in various contexts, shedding light on the factors influencing its implementation and the challenges faced by farmers. This section reviews related studies to position the current research within the existing literature and highlight the unique contributions of the mixed-methods approach used in this study.

In a study conducted by Eryılmaz et al. [13], organic agriculture and good agricultural practices in Turkey were evaluated in terms of economic, social, and environmental sustainability. The study utilized data from relevant institutions and previous research to examine the development of these practices, focusing on yield, cost, and profitability in economic terms; rural employment, direct marketing, and ecological tourism opportunities in social terms; and the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in environmental terms. The results revealed that organic agriculture provides significant environmental and social benefits but faces certain economic challenges, whereas good agricultural practices are more advantageous economically, despite offering limited environmental contributions. This study provided valuable insights into the development and implementation of sustainable agricultural policies.

In a study conducted by Doğan and Tümer [14], the variables affecting the willingness of farmers in Kahramanmaraş to participate in good agricultural practices were determined. For this purpose, a survey was conducted with 236 farmers in the central districts of Kahramanmaraş, Turkey, and the data were analyzed using the binomial logit model. The analysis revealed a negative relationship between a willingness to participate in good agricultural practices and the number of household members, non-agricultural employment status, and whether the production area was clean or polluted; conversely, a positive relationship was found between land ownership and the frequency of communication with provincial/district directorates of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. This study emphasized the need to raise awareness, particularly among small-scale farmers and those engaged in non-agricultural work, to enhance participation in good agricultural practices and highlighted the importance of these practices for environmental sustainability.

In a study conducted by Adıgüzel and Kızılaslan [15], the opinions of conventional and organic olive producers in the Aegean region regarding organic agriculture and the factors affecting preferences for organic olive production were determined. Surveys were conducted with 304 producers practicing both production techniques, and the data were analyzed using the logit model. The results revealed that the most significant factors increasing organic olive production were owning olive oil varieties, production volume, leaf fertilization, irrigation, record-keeping, the distance of orchards from villages, awareness of organic agriculture, and knowledge of organic farming legislation. Additionally, both conventional and organic producers identified a lack of information and low support payments as the main constraints to organic farming. This study emphasized the importance of education and support policies in promoting the adoption and sustainability of organic farming.

In a study conducted by Uysal et al. [16], the socio-economic structures of producers applying and not applying good agricultural practices in Mersin province were compared, their approaches to good agricultural practices were evaluated, and the factors influencing the adoption of these practices were determined. Data were collected through surveys from 89 citrus producers (orange, lemon, and mandarin) applying good agricultural practices in 2014, as well as an equal number of conventional producers. The data were analyzed using t-tests, chi-square tests, and logistic regression analysis. It was found that producers′ ages, tractor numbers, total incomes, attitudes toward innovations, and use of greenhouse farming positively influenced the adoption of good agricultural practices, while their agricultural experience and land size had a negative impact. This study emphasized the need to increase technical training and raise subsidy amounts to promote the adoption of good agricultural practices.

In a study conducted by Karaturhan et al. [8], the factors affecting the probability of rural women adopting organic farming on family farms in Turkey were investigated. The study utilized data collected from rural women in Aydın province, which were analyzed using the logit model. The research revealed that factors such as the women′s age, education level, family income, participation in agricultural activities, professional training, and awareness of organic farming significantly influenced their likelihood of adopting organic farming. Specifically, women who received professional training were found to be 9.2 times more likely to adopt organic farming, and those with knowledge of organic farming had a 4.2 times higher probability. This study highlights the importance of education and awareness-raising programs for rural women.

In a study conducted by Kaya and Atsan [9], factors affecting rural women′s adoption of organic farming in the TRA1 region (Erzurum, Erzincan, and Bayburt) were identified. A total of 158 surveys were conducted with rural women living in 60 villages across 15 districts, and the data were analyzed using logistic regression. The study revealed that younger women, women with higher education and income levels, women with larger land ownership, women who engaged in agricultural activities for commercial purposes, women with higher television watching frequency, women who participated in training programs, and women residing in Erzurum were more likely to adopt organic farming. This research emphasized the importance of education and awareness programs in promoting the adoption of organic farming among rural women.

In a study conducted by Möhring et al. [17], a systematic review of global literature on the adoption of organic farming was conducted to identify research gaps and evaluate policy recommendations. The study aimed to compile scientific recommendations for scaling organic farming, identify gaps in geographical and production system coverage, and provide guidance to policymakers and food value chain actors. This research analyzed 120 studies published between 2000 and 2021, synthesizing 183 policy recommendations. It emphasized the importance of raising awareness, improving infrastructure, adjusting supply chain regulations, and implementing public policies to increase the adoption of organic farming. Additionally, it highlighted the influence of production context on adoption strategies, particularly organic market maturity and agricultural productivity.

In a study conducted by Rizzo et al. [18], the factors influencing the adoption of sustainable agricultural innovations were examined through a systematic literature review. The study aimed to understand the psychological, socio-demographic, and contextual factors affecting farmers′ innovation adoption behavior in developed countries and to identify research gaps in this field. A total of 44 studies published since 2010 were analyzed to determine the drivers and barriers to adopting sustainable innovations. The findings revealed that factors such as environmental values, education level, economic incentives, and technical support positively influence farmers′ adoption of innovations, while complexity, high costs, and low perceived control were significant barriers. This study provided recommendations for policymakers and researchers to enhance the adoption of sustainable innovations.

In a study conducted by Serebrennikov et al. [19], the factors influencing the adoption of sustainable farming practices in Europe were systematically examined. The study aimed to understand the conditions and factors affecting the adoption of widely used sustainable farming practices, such as organic farming, manure treatment technologies, and soil and water conservation methods. A total of 23 peer-reviewed studies published between 2003 and 2019 were analyzed. The findings indicated that farmers′ environmental and economic attitudes play a significant role in adopting organic farming but have less impact on manure treatment and conservation measures. Additionally, farmers′ age and education level were found to influence the adoption of organic farming, while their effects on other technologies remain unclear. The study emphasized the need for further research using standardized surveys and methods to provide better guidance for policymakers.

In a study conducted by Sapbamrer and Thammachai [20], the factors influencing the adoption of organic farming were systematically reviewed. The study aimed to identify the key factors affecting farmers′ transition to organic farming and to support the promotion of organic farming based on these factors. The study covered 50 articles published between 1999 and 2021, focusing on the adoption of organic farming. Factors were categorized into four main groups: farmer and household factors (e.g., age, gender, and education level), psychosocial and behavioral factors (e.g., positive attitude, norms, and moral obligations), farming factors (e.g., organic farming experience and production costs), and supportive factors (e.g., training, technology support, and farmer associations). The results indicated that younger farmers, women, those with higher education levels, and those with additional income sources were more likely to adopt organic farming. Additionally, government support, training programs, and farmer associations were highlighted as key drivers for the sustainable adoption of organic farming.

The current study builds on the findings of previous research by employing a mixed-methods approach to explore the factors influencing organic farming adoption in Turkey’s Thrace region. Unlike many earlier studies that relied solely on quantitative or qualitative methods, this research integrates both to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issue. It specifically focuses on farmers′ perceptions of economic sustainability and barriers, examining how these perceptions impact their decisions to adopt organic farming. By concentrating on the Thrace region, we offer valuable insights into a specific geographical area with unique agricultural characteristics, complementing broader studies conducted in Turkey and globally. Additionally, the mixed-method design enables a deeper exploration of the challenges faced by farmers, such as financial difficulties during the certification process and marketing constraints, alongside their proposed solutions. This approach not only enhances the understanding of farmers’ experiences but also contributes to the literature by offering actionable recommendations for policymakers, including targeted financial support, marketing guarantees, and expanded training programs to facilitate the widespread adoption of organic farming.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Model

This study adopted a mixed-method research design, combining the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem [21]. A mixed-method design can integrate numerical data from quantitative research with detailed insights from qualitative data, offering a holistic perspective on the factors influencing organic farming adoption.

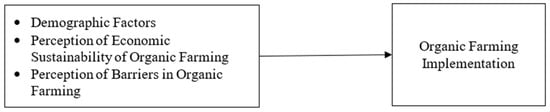

In the quantitative part of this study, a relational screening model was employed. This model is widely used to explore the relationships between two or more variables and to determine the strength and direction of these relationships [22]. Specifically, the quantitative analysis examined the relationships between farmers′ demographic characteristics, their perceptions of economic sustainability and barriers, and the implementation of organic farming practices. The effects of demographic factors, such as age, education level, gender, farming experience, and land ownership, were also analyzed. The research model is visually presented in Scheme 1, which outlines the independent and dependent variables included in the analysis.

Scheme 1.

Research model.

The selection of independent variables for the hierarchical logistic regression analysis was guided by both theoretical insights and empirical evidence from the literature. The research model was designed to comprehensively examine the factors influencing the adoption of organic farming practices, incorporating both demographic and economic dimensions. Demographic variables such as age, gender, education level, agricultural experience, and land ownership were included based on their established significance in the literature. For instance, age has been shown to influence openness to innovation [23], while education level facilitates access to agricultural information and resources [9]. Similarly, land ownership has been identified as a critical factor affecting production decisions [14]. Other individual factors, including marital status, income, land size, farming experience, and cooperative membership, have also been highlighted as influential in the adoption of organic farming practices [8,15,16,19,20]. In addition to demographic factors, the model incorporates economic perceptions as key predictors. Variables such as the perception of economic sustainability [12] and the perception of economic barriers [11] were included to capture farmers’ views on the long-term viability and challenges of organic farming. These variables are particularly relevant for understanding how economic considerations shape farmers′ decisions to adopt organic farming practices. By integrating these elements, the model aims to holistically evaluate the contributions of both individual and economic factors to the adoption of organic farming.

The research model was analyzed using a two-stage approach. In the first stage, the effects of demographic factors on organic farming practices were evaluated; in the second stage, the effects of perceptions of economic sustainability and economic barriers were incorporated into the model. This approach provides an important framework for understanding that decisions regarding organic farming practices are shaped by both individual and economic motivations.

On the other hand, the qualitative part of the study complemented the quantitative findings by providing deeper insights into farmers′ experiences, challenges, and proposed solutions related to organic farming. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with farmers, and thematic analysis identified recurring patterns and themes in their responses [24]. This qualitative approach enriched the study by capturing the nuanced perspectives of farmers, which are often difficult to quantify.

Overall, the mixed-method design enabled a robust examination of the factors influencing organic farming adoption in Turkey’s Thrace region. By integrating quantitative and qualitative data, the study not only identified statistically significant predictors but also provided actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners aiming to promote sustainable agricultural practices.

3.2. Sample

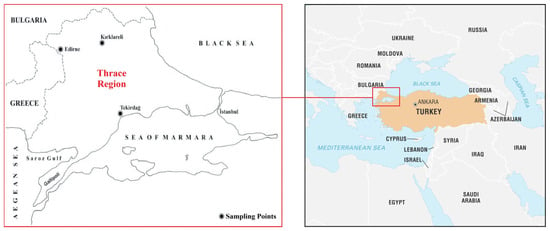

The population of this research consisted of farmers in the Thrace region in northwestern Turkey. The region comprises three provinces—Tekirdağ, Edirne, and Kırklareli—and is one of Turkey′s most important agricultural areas due to its fertile soil and favorable climate conditions. The sampling points across the region are shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Sampling points.

According to the most recent accessible data, there are 76,560 farmers in the Thrace region [25]. It has been calculated that 383 participants can represent a population of this size with a 95% confidence level and 5% sampling error [26]. A total of 400 farmers participated in the research, and it was concluded that the required sample size was achieved. The convenience sampling technique, a non-probability sampling method, was used. This method allows the researcher to include individuals who are accessible and willing to participate in the research [22]. Convenience sampling was preferred due to its advantages in terms of time and cost. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research and the confidentiality of the data, and their voluntary participation consent was obtained. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic statistics of participants.

The majority of participants were male (n = 295, 73.8%). In terms of education level, most were middle school (30.0%, n = 120) and primary school (27.3%, n = 109) graduates. High school graduates constituted 21.5% (n = 86), literate participants 11.5% (n = 46), and university graduates 9.8% (n = 39). Examining agricultural land ownership, more than half of the farmers (54.5%, n = 218) owned their land, 29.3% (n = 117) had partially rented/owned land, and 16.3% (n = 65) farmed on rented land.

Perceived agricultural income categories were determined based on the farmers’ self-assessment of their agricultural income levels. During the survey, farmers were asked to evaluate their agricultural income level as “poor”, ”moderate”, or “good” according to their own perception, rather than using predetermined income thresholds. This subjective assessment approach was preferred since it captures the farmers′ own evaluation of their economic situation, as they may be reluctant to share exact income figures. Additionally, considering that agricultural income can vary significantly from year to year, using self-assessment better aligns with the study′s focus on perceptions rather than absolute economic measures. Regarding perceived agricultural income level, 37.5% (n = 150) of participants evaluated it as normal, 34.5% (n = 138) as poor, and 28.0% (n = 112) as good. In total, 61.0% (n = 244) of participants indicated that they had no income outside of agriculture, while 59.5% (n = 238) reported using agricultural credits. The proportion of those who received organic farming training was 56.5% (n = 226), while 48.5% (n = 194) were members of a cooperative.

The participants had a mean age of 44.69 (SD = 9.33, range = 25–69) and an average farming experience of 24.37 years (SD = 7.42, range = 5–49). The average duration of organic farming practice was 4.48 years (SD = 5.05, range = 0–15). While the average total agricultural land was 72.98 decares (SD = 62.91, range = 5–300), the average organic farming land was 17.22 decares (SD = 30.66, range = 0–250). The average number of family members was 3.41 (SD = 1.73, range = 1–6).

3.3. Measures

In this research, data were collected using the survey technique. The first part of the survey included a demographic information form prepared by the researcher, containing 15 questions. The last question in the demographic information form asked participants about the economic challenges of starting and maintaining organic farming and their suggestions for solutions to overcome these challenges. The responses to this question formed the qualitative data of the research.

The second part of the survey included scales for the economic sustainability of organic farming, containing seven questions [12], and the economic barriers of organic farming, containing six questions [11]. The scales are a five-point Likert type (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). The validity and reliability analysis results for these scales, which were adapted into Turkish by the researcher, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Validity and reliability analysis results.

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to test the construct validity of the scales used in this research. For the Economic Sustainability of Organic Farming Scale, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy value was found to be 0.922. Bartlett′s sphericity test results (χ2 = 5358.616, df = 21, p < 0.001) indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis. The single-factor structure of the scale explains 70.487% of the total variance. The factor loadings of the seven-item scale range between 0.906 and 0.971. The Cronbach′s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.920.

For the Economic Barriers in Organic Farming Scale, the KMO value was found to be 0.851. Bartlett′s sphericity test results (χ2 = 2377.101, df = 15, p < 0.001) indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis. The single-factor structure of the six-item scale explains 73.040% of the total variance. The factor loadings of the scale items range between 0.639 and 0.944. The Cronbach′s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.900.

The values obtained for both scales indicate that they are valid and reliable measurement tools.

3.4. Procedure

The quantitative data collected in the research were analyzed using SPSS v27. In the quantitative part of the research, logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the effects of farmers′ demographic characteristics, as well as their perceptions of economic sustainability and barriers, on the implementation of organic farming. In the qualitative part of the research, the thematic analysis method was used. The thematic analysis method can identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) in qualitative data [24]. In this study, the economic challenges faced by farmers in starting and maintaining organic farming and their proposed solutions to overcome these challenges were thematically analyzed.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Findings

A hierarchical logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the factors affecting farmers′ organic farming implementation. As the dependent variable, farmers′ organic farming implementation status was coded as 0 = Does not practice organic farming or 1 = Practices organic farming. Demographic variables were included as independent variables in the first model. In the second model, in addition to demographic variables, perceptions of the economic sustainability of organic farming and perceptions of economic barriers to organic farming were included. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis results.

Model-1 examined only demographic variables and was found to be statistically significant (χ2 (12) = 181.447, p < 0.01). Model-1 explains 36.5% of the variance according to the Cox and Snell R2 value and 48.9% according to the Nagelkerke R2 value. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed that the model fits the data well (χ2 (8) = 5.210, p = 0.735). Model-1 correctly classified 78.3% of cases. According to the analysis results, age (B = −0.070, SE = 0.028, p = 0.011, OR = 0.932), education level (B = 0.348, SE = 0.122, p = 0.004, OR = 1.416), agricultural land ownership (B = 0.541, SE = 0.180, p = 0.003, OR = 1.718), credit use (B = 0.640, SE = 0.268, p = 0.017, OR = 1.896), and organic farming training (B = 2.786, SE = 0.282, p < 0.001, OR = 16.219) were significant predictors in the adoption of organic farming. Other variables (gender, farming experience, agricultural land size, number of family members, perceived agricultural income, non-agricultural income, and cooperative membership) were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). When odds ratios are examined, having organic farming training increases the likelihood of adopting organic farming practices by 16.2 times. Similarly, credit use increases it by 1.9 times, agricultural land ownership by 1.7 times, and education level by 1.4 times. A one-unit increase in age decreases the likelihood of adoption by 0.932 times.

Model-2 was created by adding economic sustainability and economic barrier perception variables and was found to be statistically significant (χ2 (14) = 273.731, p < 0.01). Model-2 explains 49.6% of the variance according to the Cox and Snell R2 value and 66.5% according to the Nagelkerke R2 value. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed that the model fits the data well (χ2 (8) = 9.878, p = 0.274). Model-2 correctly classified 85.0% of the cases. In Model-2, the age (B = −0.067, SE = 0.033, p = 0.039, OR = 0.935), education level (B = 0.302, SE = 0.141, p = 0.032, OR = 1.353), agricultural land ownership (B = 0.557, SE = 0.214, p = 0.009, OR = 1.745), organic farming training (B = 2.909, SE = 0.351, p < 0.001, OR = 18.341), economic sustainability (B = 1.493, SE = 0.246, p < 0.001, OR = 4.451), and economic barrier perception (B = −1.141, SE = 0.219, p < 0.001, OR = 0.320) variables were found to be significant predictors in the adoption of organic farming. Other variables were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). When examining the odds ratios, having received organic farming training increases the likelihood of implementing organic farming by 18.3 times. While a one-unit increase in economic sustainability perception increases the likelihood of adoption by 4.5 times, agricultural land ownership increases it by 1.7 times, and education level by 1.4 times. By contrast, a one-unit increase in economic barrier perception decreases the likelihood of adoption by 0.32 times (approximately 68%). Similarly, a one-unit increase in age decreases the likelihood of adoption by 0.935 times.

When comparing the two models developed to explain the adoption of organic farming practices, the second model, which included economic variables (sustainability and barrier perception), shows higher explanatory power. The correct classification rate also increased from 78.3% to 85.0%. Age, education level, agricultural land ownership, and organic farming training were significant predictors in both models. However, credit use, which was significant in the first model, lost its significance in the second. The economic sustainability and economic barrier perception variables added to the second model emerged as strong determinants in the adoption of organic farming practices. Consequently, the second model has higher explanatory power and demonstrates that economic factors play an important role in the adoption of organic farming practices. Specifically, while a high perception of economic sustainability positively affects adoption, a high perception of economic barriers negatively affects adoption.

4.2. Qualitative Findings

The participants were first asked about the economic challenges they face in starting and maintaining organic farming. As shown in Table 4, the content analysis of the responses revealed that the challenges farmers face during the transition to organic farming could be grouped under six main themes.

Table 4.

Content analysis results regarding challenges in organic farming.

- Financial issues appear to be the most significant challenge area. Particularly, certification costs (f = 28), insufficient credit opportunities (f = 22), and lack of capital (f = 21) are among the most frequently mentioned problems. One participant′s statement clearly demonstrates this situation: “Currently, our biggest problem is finding financing. When we go to banks, adequate credit opportunities are not provided, which makes it difficult for us” (P30).

- In production challenges, difficulties and costs in obtaining organic inputs are particularly prominent. The supply and cost of organic fertilizer (f = 25), organic pesticide supply and cost (f = 22), and organic seed cost (f = 20) are among the main issues. A farmer′s statement clearly reflects this challenge: “Organic seed and fertilizer costs are very high. The costs of these inputs are almost double compared to conventional farming, which makes production difficult” (P322).

- Under the theme of knowledge and training deficiency, a lack of technical knowledge (f = 19) and insufficient training (f = 17) stand out. A producer′s statement emphasizes the need in this area: “Technical knowledge is very important in organic farming, but unfortunately, we cannot receive adequate training in this area. We need more technical support and training” (P334).

- Under the labor and cost theme, labor costs (f = 16) and workforce expenses (f = 15) are notable. Challenges in marketing and sales are particularly concentrated around insufficient marketing channels (f = 15) and product sales difficulties (f = 14). One participant′s statement summarizes this situation: “The inadequacy of marketing channels is a major problem. We struggle to find regular and reliable channels to sell our products” (P317).

- Finally, under the theme of transition process challenges, income loss during transition (f = 13) and transition period adaptation problems (f = 12) are prominent. One farmer′s statement clearly demonstrates this challenge: “Income loss during the transition period is a serious problem for us. During this period, both yield decreases and our expenses increase” (P169).

These findings show that farmers face multidimensional challenges in the transition to organic farming. Economic challenges particularly stand out as the most frequently mentioned problems.

Additionally, the participants were asked about their suggested solutions for overcoming the economic challenges of starting and maintaining organic farming. As shown in Table 5, content analysis of the responses revealed that farmers′ suggestions were grouped under five main themes.

Table 5.

Content analysis results regarding solution suggestions.

- Financial support appears to be the most prominent theme. Under the financial support theme, providing financial support during the certification process (f = 32), offering low-interest agricultural loans (f = 28), and increasing financial support (f = 20) particularly stand out. One participant′s suggestion clearly demonstrates this need: “The government should provide financial support during the certification process, especially standing by the farmer in the initial period” (P42).

- Under the production support theme, the main suggestions include providing fertilizer and pesticide support (f = 30), organic input support (f = 25), and support for production inputs (f = 18). A producer′s statement emphasizes this need: “Government support for organic fertilizers and pesticides is essential; otherwise, production with these costs is very difficult” (P177).

- Under the marketing support theme, suggestions include providing product purchase guarantees (f = 35), market guarantees (f = 25), and development of sales channels (f = 20). One participant′s suggestion clearly demonstrates this need: “Our products should have purchase guarantees; farmers shouldn′t worry about being unable to sell their products” (P258).

- Under the labor support theme, suggestions that stand out include providing labor support (f = 22), support for workforce expenses (f = 20), and government support for employee costs (f = 15). A farmer′s statement reflects this need: “Labor costs are very high; government support in this area is essential” (P332).

- Under the education and technical support theme, prominent suggestions include providing technical knowledge support (f = 20), expanding training programs (f = 18), and organizing free training sessions (f = 15). A producer′s suggestion emphasizes this need: “There should be regular technical support and training programs; farmers should know what to do and how to do it” (P339).

These findings show that farmers need multi-faceted support mechanisms during the transition to organic farming. Financial support and marketing guarantees particularly stand out as the most requested solutions.

5. Discussions and Limitations

The research findings show that certain demographic variables (age, education, agricultural land ownership, credit use, organic farming training) significantly affect the adoption of organic farming.

Although gender was included in the analysis, it did not emerge as a significant predictor of organic farming adoption. This finding differs from some previous studies that found gender to be a significant factor in agricultural innovation adoption [20]. This unexpected result might be explained by several factors specific to the Thrace region, including the relatively balanced distribution of decision-making power between male and female farmers in family farms, equal access to agricultural training and resources regardless of gender, and the cooperative farming culture in the region, where decisions are often made collectively rather than individually. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as the sample had an uneven gender distribution (73.8% male, 26.3% female), possibly affecting the statistical power to detect gender-based differences. Future research with a more balanced representation might provide additional insights into the role of gender in organic farming adoption in the region.

The negative effect of age indicates that younger farmers are more inclined toward organic farming. This finding can be explained by younger farmers being more open to innovations and more conscious of sustainable agriculture [23]. Regarding the age factor, different findings exist in the literature. While some studies show that young farmers adopt organic farming more easily [9,14,23], others show that older farmers are more willing [16,27]. This difference may stem from the balance between younger farmers being more open to innovations and older farmers having more experience and financial resources.

The positive effect of education level indicates that farmers with higher education levels are more likely to adopt organic farming. This result supports the view that education increases the capacity to understand and implement innovative farming practices [28]. The literature presents more consistent results regarding education level. Many studies have confirmed that higher education levels positively affect the adoption of organic farming [8,14,29,30]. Farmers with higher education levels are seen to have a greater capacity to understand and implement new technologies and sustainable practices.

The positive effect of agricultural land ownership indicates that farmers who own their land are more likely to transition to organic farming. This finding, also reached by Kaya and Atsan [9], can be explained by property owners being more willing to make long-term investments and adopt sustainable practices [31].

The positive effect of credit use indicates that access to financial resources facilitates the transition to organic farming. This finding can be explained by the fact that transitioning to organic farming requires certain financial investments and credit opportunities to support this process [32].

The very strong positive effect of organic farming training indicates that education plays a critical role in the adoption of organic farming. This result is consistent with studies emphasizing the importance of knowledge and skill acquisition in adopting innovative farming practices [8,9,33]. The very strong effect of organic farming training on adoption can be explained by the fact that organic farming requires specific technical knowledge and skills that are fundamentally different from conventional farming methods. Training provides farmers with technical knowledge and increases their confidence in implementing organic practices, helping them better understand potential economic benefits and risk management strategies.

On the other hand, research findings have shown that while a high perception of economic sustainability positively affects the adoption of organic farming, a high perception of economic barriers negatively affects adoption.

The positive effect of economic sustainability perception on adoption can be explained by farmers′ expectations of long-term economic benefits. Economic advantages such as premium prices, market guarantees, and subsidies provided by organic farming are seen as important sources of motivation for producers to adopt this production system [34]. Additionally, increasing demand for organic products and consumers′ willingness to pay higher prices for these products strengthen producers′ perception of economic sustainability [34].

On the other hand, the negative effect of economic barrier perception on adoption can be associated with the costs and risks during the transition to organic farming. Certification costs, possible yield decreases during the transition period, and investments required for new production techniques can create significant economic barriers, especially for small-scale enterprises. Furthermore, potential income losses during the transition from conventional to organic farming increase producers′ economic concerns [35].

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the data were collected from farmers in the Thrace region of Turkey, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions with different agricultural, socio-economic, and cultural characteristics. Second, the study employed a convenience sampling method, which might introduce selection bias and limit the representativeness of the sample. Third, while the mixed-methods approach provided a comprehensive understanding of the research problem, the qualitative part of the study relied on self-reported data, which could be influenced by social desirability bias. Fourth, the study primarily focused on economic sustainability and barriers, potentially overlooking other critical factors such as environmental and social sustainability, which could also influence the adoption of organic farming. Additionally, the research did not extensively examine the role of policy frameworks and institutional support mechanisms, which might be crucial for organic farming implementation. Finally, as this research was cross-sectional, it does not capture the dynamic nature of farmers′ perceptions and behaviors over time, nor does it track the long-term outcomes of organic farming adoption decisions.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study explored the impact of farmers′ demographic characteristics, perceptions of economic sustainability, and barriers on the adoption of organic farming practices in Turkey′s Thrace region. Based on a mixed-method research design, the findings provide valuable insights into the factors influencing organic farming adoption.

The results demonstrate that age, education level, agricultural land ownership, and organic farming training are significant predictors of adoption. Younger farmers, those with higher levels of education, and those who have received training in organic farming are more inclined to adopt organic practices. Additionally, positive perceptions of economic sustainability encourage adoption, while economic barriers discourage farmers from transitioning to organic farming.

The qualitative findings highlight several challenges faced by farmers during the transition to organic farming. Financial constraints, such as high certification costs and limited access to credit, are among the most significant barriers. Production-related challenges, including the high cost and limited availability of organic inputs, also create obstacles. Furthermore, a lack of technical knowledge and insufficient training opportunities hinder farmers′ ability to implement organic farming effectively. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions to address these challenges.

To support the widespread adoption of organic farming, several policy recommendations emerge. Financial support mechanisms, such as subsidies for certification costs and low-interest agricultural loans, should be prioritized. Programs to improve access to organic inputs and provide technical training are essential. Additionally, marketing support, including product purchase guarantees and the development of reliable sales channels, can ensure that farmers receive fair prices for their products. These measures would alleviate the economic burdens on farmers and create a more supportive environment for organic farming.

Future research should expand the geographical scope by conducting similar studies in various regions with differing agricultural, socio-economic, and cultural contexts to enhance the generalizability of findings. Employing probability sampling methods in future studies could also address potential selection bias and improve the representativeness of the sample. Additionally, longitudinal studies that capture the dynamic nature of farmers’ perceptions and behaviors over time would provide deeper insights into the long-term economic, environmental, and social sustainability of organic farming. Future research could also benefit from incorporating a broader range of sustainability dimensions, such as environmental and social factors, to provide a more holistic understanding of the barriers and opportunities in organic farming adoption. Finally, mixed-methods approaches could be further strengthened by triangulating self-reported data with objective measures to mitigate potential biases.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University (protocol code T2024-2170 and 7 October 2024 date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the author.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the respondents who voluntarily participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reganold, J.P.; Wachter, J.M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalbeyler, D.; Işın, F. Organic agriculture in Turkey and its future. Turk. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 23, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turhan, Ş. Sustainability in agriculture and organic farming. Turk. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 11, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Schlatter, B.; Trávníček, J. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2023; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL: Vienna, Austria; IFOAM Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: Conventional vs. organic agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Narwal, K.P.; Kumar, S. Economic sustainability of organic farming: An empirical study on farmer’s prospective. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2024, 10, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiryürek, K. The concept of organic agriculture and current status of in the world and Turkey. GOU J. Fac. Agric. 2011, 28, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karaturhan, B.; Uzmay, A.; Koç, G. Factors affecting the probability of rural women’s adopting organic farming on family farms in Turkey. J. Ege Univ. Fac. Agric. 2018, 55, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, T.E.; Atsan, T. Factors affecting rural women’s adoption of organic agriculture (TRA1 of sample). Atatürk Univ. J. Agric. Fac. 2013, 44, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 2023 Organic Agriculture Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/Konular/Bitkisel-Uretim/Organik-Tarim/Istatistikler (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Altarawneh, M. Determine the barriers of organic agriculture implementation in Jordan. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Raghuprasad, K.P.; Shivamurthy, M. Ecological, economical and social sustainability of organic farming. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2019, 55, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Eryılmaz, G.A.; Kılıç, O.; Boz, İ. Evaluation of Organic Agriculture and Good Agricultural Practices in Terms of Economic, Social and Environmental Sustainability in Turkey. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 29, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Tümer, E.İ. Variables that affect the willingness of farmers to participate good agricultural practices: Sample of Kahramanmaraş. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 29, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adıgüzel, F.; Kızılaslan, N. Factors affecting organic olive production preference in Aegean Region of Turkey. Gaziosmanpasa J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, O.; Aydın, B.; Subaşı, O.S.; Aktaş, E. Farmers’ approaches to good agricultural practices and the factors effecting the adoption of the practices: Case of Mersin Province. Turk. J. Agric. Nat. Sci. 2021, 8, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhring, N.; Muller, A.; Schaub, S. Farmers’ adoption of organic agriculture—A systematic global literature review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2024, jbae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Vecchio, R. Key factors influencing farmers’ adoption of sustainable innovations: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrennikov, D.; Thorne, F.; Kallas, Z.; McCarthy, S.N. Factors influencing adoption of sustainable farming practices in Europe: A systemic review of empirical literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapbamrer, R.; Thammachai, A. A systematic review of factors influencing farmers’ adoption of organic farming. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karasar, N. Scientific Research Methods, 37th ed.; Nobel Academic Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, M.C.; Bava, L.; Sandrucci, A.; Tangorra, F.M.; Tamburini, A.; Gislon, G.; Zucali, M. Diffusion of precision livestock farming technologies in dairy cattle farms. Animal 2022, 16, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurma, H. Current Status of the Agricultural Structure of the Thrace Region. 2019. Available online: https://www.iklimin.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Bo%CC%88lu%CC%88m3_Harun_Hurma.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Yazıcıoğlu, Y.; Erdoğan, S. SPSS Applied Scientific Research Methods; Detay Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cortijo, M.C.; Castillo-Valero, J.S.; Carrasco, I. Innovation in rural Spain. What drives innovation in the rural-peripheral areas of southern Europe? J. Rural Stud. 2019, 71, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genius, M.; Pantzios, C.J.; Tzouvelekas, V. Information acquisition and adoption of organic farming practices. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 31, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D.; et al. A scoping review on incentives for adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and their outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollni, M.; Andersson, C. Spatial patterns of organic agriculture adoption: Evidence from Honduras. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 97, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S. Conversion to organic farming: A typical example of the diffusion of an innovation? Sociol. Rural. 2001, 41, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Li, E.; Bruwer, J.; Abdullah, A.M.; Brindal, M.; Radam, A.; Ismail, M.M.; Darham, S. The relative importance of factors influencing the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: A factor approach for Malaysian vegetable farmers. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Barrera, A.; Pennings, J.M.; Hofenk, D. Understanding producers’ motives for adopting sustainable practices: The role of expected rewards, risk perception and risk tolerance. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2016, 43, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; López-Felices, B.; del Moral-Torres, F. Barriers and facilitators for adopting sustainable soil management practices in Mediterranean olive groves. Agronomy 2020, 10, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).