Abstract

The transition from soft to hard law is reshaping global agri-food governance, particularly in relation to sustainability and corporate responsibility. This article analyzes this shift by examining two regulatory approaches: voluntary instruments such as the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains and binding EU directives like the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Using a qualitative and interpretive methodology, the study combines a literature review and two case studies (Nicoverde and Lavazza) to explore the evolution from soft law to hard law and the synergies and analyze how these tools are applied in the Italian agri-food sector and how they can contribute to improving corporate sustainability performance. Findings show that soft law has paved the way for more rigorous regulation, but the increasing compliance burden poses challenges, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These cases serve as virtuous examples to illustrate how soft and hard law interact in practice, offering concrete insights into the translation of general sustainability principles into corporate strategies. A hybrid governance framework—combining voluntary and binding tools—can foster sustainability if supported by coherent policies, stakeholder collaboration and adequate support mechanisms. The study offers practical insights for both companies and policymakers navigating the evolving legal scenario.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the agri-food sector has been subjected to growing public and institutional attention towards environmental, social, and economic sustainability. Rising consumer expectations, the activism of civil society organizations, the boost provided by sustainable finance and numerous scandals related to unfair practices along supply chains have made the adoption of tools that promote corporate responsibility increasingly urgent [1,2].

In this context, the growing complexity of global challenges—from climate change to the regulation of digital markets—has highlighted the need for more flexible and scalable regulatory instruments. Hence the growing role of soft law, alongside (and not in opposition to) hard law. In particular, we are witnessing a significant shift from the “moral rules” of soft law—voluntary instruments such as guidelines, recommendations and codes of conduct—to the binding regulations of hard law, which introduce rigorous legal obligations, liability systems and sanctions for violations [3].

The boundary between binding law and non-binding guidelines has become increasingly blurred, shaping a regulatory ecosystem in which soft law and hard law coexist, interact and mutually influence each other. This process reflects a broader evolution in global governance, in which rules are constructed through widespread practices and reputational pressure and not only through top-down obligations.

This paradigm shift is not only normative, but also cultural: we are moving from an idea of responsibility as a spontaneous adherence to ethical principles to a vision in which sustainability becomes an integral part of compliance with the law. The agri-food sector, characterized by complex, global and often opaque supply chains, is at the center of this transformation [4]. In this context, regulation also plays a role in providing ethical guidance and building trust among supply chain stakeholders.

The aim of this article is to analyze how—and with what tools—this transition is taking place, examining two distinct yet interconnected approaches:

- Soft law: non-binding instruments that influence behavior and complement hard law. In this work, this definition is represented by international guidelines and standards such as those of the OECD and OECD-FAO [2].

- Hard law: legally binding rules and regulations, enforceable through formal legal mechanisms. In this work, particular attention is paid to two European directives: the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [5,6].

The synergy between soft law and hard law emerges when non-binding instruments, such as guidelines or codes of conduct, anticipate or accompany the development of binding regulations, acting as both a testing ground and as an interpretative benchmark for legislators and courts. As Trubek observes, “soft law often functions as a precursor to binding norms, shaping the terrain on which formal regulation is later constructed” [7]. In this sense, soft law encourages new rules, building consensus and legitimacy that hard law later makes permanent.

At the same time, the interaction between the two levels generates a mutually reinforcing effect: hard law confers authority and stability to rules already sedimented in practice through soft law instruments, while the latter provide flexibility and adaptability. As Snyder points out, “the real strength of soft law lies in its capacity to complement hard law by ensuring adaptability within an evolving legal order” [8]. The result is a progressive evolution of the legal system that avoids the need for constant legislative revisions.

In short, the relationship between soft law and hard law should not be understood in terms of opposition but rather as functional complementarity. Soft law offers guidance and experimentation tools that facilitate the emergence of new rules, while hard law ensures binding force and legal certainty. Together, they shape a dynamic regulatory model capable of balancing innovation and stability. As Abbott and Snidal emphasize, “hard and soft law are best understood as complements rather than substitutes within a continuum of legalization” [3].

In this regard, this paper intends to explore how soft law instruments have anticipated, guided or strengthened the evolution of binding rules, questioning whether this coexistence represents an opportunity for effective governance or, conversely, a risk to legal certainty.

Specifically, the paper is structured to answer the following research questions:

- Can soft law and hard law truly coexist harmoniously without overlapping and generating tensions and ambiguities in their application?

- Can soft law instruments serve as a point of reference for guiding agri-food companies toward more sustainable, inclusive and human rights-respecting practices?

- Can the evolution from soft law to hard law in the agri-food sector help ensure greater accountability throughout the entire production chain?

- Are the applications of soft law and hard law instruments in the case studies examined, guiding the transition toward a more equitable, transparent and sustainable food system?

Case studies have proven to be a particularly effective methodology for analyzing complex issues such as those addressed in this paper [9].

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the research methodology adopted, illustrating the case selection criteria, the sources used and the analytical approach followed.

Section 3 explores the role of soft law in multilevel governance and its evolution, then analyzes an operational tool applied to the agri-food sector: the OECD-FAO Guidance on Responsible Business Conduct. Its concrete application is illustrated through a first case study, Nicoverde-Nicofrutta.

Section 4 focuses on hard law, with particular attention to the recently approved European directives (CSDD and CSRD) and their application through a second case study, Lavazza, that demonstrates their practical effects.

Finally, Section 5 presents some conclusions and future directions, focusing on the prospects for integrating hard and soft law and the potential role of shared responsibility as a lever for a deeper and more systemic transformation of agri-food supply chains.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative and interpretive research approach [9,10], which is particularly suited to investigating complex and evolving phenomena such as the interaction between soft and hard law in the agri-food sector. The methodology is based on a triangulation of sources: a structured literature review, normative and institutional document analysis, and two in-depth case studies.

The research aims to explore how companies interpret and implement soft and hard law instruments in real-world contexts. To do so, we selected two contrasting case studies that exemplify the voluntary application of soft law guidelines (Nicoverde-Nicofrutta) and the implementation of binding European legislation (Lavazza). The selection followed a purposive sampling strategy [11], based on criteria such as:

- relevance of the agri-food sector in terms of environmental, social and economic impacts;

- diversity of legal instruments adopted (soft vs. hard law);

- availability of documentary and secondary sources (company reports, sustainability disclosures, official documents, scientific literature);

- access to decision-making and implementation processes within companies;

- willingness of companies to participate in interviews;

- alignment with the new EU regulatory framework under study.

For the first case, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants (e.g., sustainability managers, supply chain officers), both cases were supported by a review of internal policies, sustainability reports and third-party evaluations. The interview data were analyzed descriptively, using a thematic content approach without formal coding, given the exploratory nature of the study.

This approach allows for an in-depth understanding of the practical implications of legal tools in two different regulatory contexts.

However, we acknowledge some methodological limitations:

- the number of case studies is limited, which restricts the generalizability of findings to the wider agri-food sector.

- the selection of companies was not random and may be biased toward more sustainability-oriented firms.

- the interviews provide self-reported perspectives that may reflect reputational concerns or internal narratives.

- the lack of longitudinal data limits the assessment of long-term impacts.

Despite these limitations, the case study offers valuable insights into how companies navigate evolving regulatory environments and how hybrid legal frameworks may influence business practices.

To enhance transparency, the sources of data for the case studies are presented in a tabular format following the “data attributes–sources–details” scheme (Table 1). This allows readers to understand the type of information used, its origin, and relevant methodological details.

Table 1.

Data Sources for Case Study Analysis.

3. The Evolution of Soft Law in Global Regulation: Between Flexibility and Responsibility

3.1. Soft Law in Multilevel Governance: Regulatory Flexibility in a Dynamic Regulatory Context

In the contemporary legal landscape, the concept of soft law has assumed an increasingly important role, especially in supranational contexts, where binding legislation often proves insufficient or fragmented [12,13]. The term soft law refers to those atypical and non-binding legal instruments—such as resolutions, recommendations, or codes of conduct—which, while not having binding force, significantly influence the behavior of the entities to which they refer [14].

They are therefore legal or almost-legal acts that, while not enforceable or subject to sanctions for violation, have regulatory efficacy and often anticipate the future evolution of binding law [12]. These tools include recommendations, codes of conduct and guidelines that, especially in the agri-food sector, guide businesses towards virtuous practices on crucial issues such as human rights, environmental protection, decent work, traceability and supply chain governance.

In international law, soft law is often preferred by a variety of actors—states, businesses, international organizations and civil society—to address complex issues that require rapid and shared responses and for which binding law is sometimes inadequate. As [3] observe, the adoption of non-binding rules, or those characterized by attenuated obligations and weaker enforcement mechanisms, brings significant advantages: it facilitates implementation, reduces the impact on state sovereignty, offers tools for managing uncertainty and facilitates compromise between actors with divergent interests.

Because of its flexibility, soft law allows for addressing rapidly evolving issues, promotes consensus on controversial issues and contributes, through practices and declarations, to the development of customary international law. In this context, it performs various functions: it can have a preparatory role, anticipating future binding obligations; a supplementary function, clarifying or specifying existing norms and a guiding role, guiding behavior in highly complex or volatile areas. Furthermore, it represents a flexible and adaptable normative instrument, particularly useful in those contexts where formal law fails to intervene promptly or adequately [15].

In his contribution to soft law in the Handbook of International Organizations, Bogdandy [12] proposes a functional classification of instruments in the multilateral context, distinguishing between:

- prescriptive soft law (e.g., regulatory guidelines);

- interpretative soft law (e.g., political or legal declarations);

- procedural soft law (e.g., technical standards and procedural rules).

The author emphasizes, however, the ambivalence inherent in these instruments: while on the one hand they foster consensus and flexibility in legislative development, on the other they can lead to a weakening of transparency and democratic control, especially in the dynamics of international governance [16], in his textbook of international law, devotes ample space to the topic, recognizing its growing importance in contemporary law and its relevance in the construction of an increasingly complex and multilevel legal system. Table 2 summarizes the main strengths and critical issues of soft law in this context.

Table 2.

Strengths and critical issues of soft law.

The study of soft law is therefore essential for understanding not only the transformations underway in international law, but also the role it can play as an effective regulatory tool in strategic sectors such as the agri-food sector.

In the context of the growing fragmentation of the global production process—now a physiological feature of the modern economy [17]—there is an emerging need for regulatory tools capable of coordinating a multiplicity of actors and responsibilities along value chains. In this scenario, soft law emerges as a key regulatory resource for promoting models of co-responsibility among businesses, worker, and institutional actors [18].

The adoption of non-binding instruments allows for the development of participatory approaches to regulation, based on a “proceduralization of the due diligence model” [19], which requires prior knowledge of the factual situation and organizational risks associated with the structure of production processes. In this sense, soft law helps guide corporate conduct and practices in contexts where mandatory legislation is ineffective or absent [7,20].

In international law, this function is particularly expressed through the promotion of preventive due diligence tools aimed at managing risks along production chains, in line with a vision of risk that is not limited to the technical sphere, but also includes the physical, psychological and relational well-being of workers, as well as the “organizational balance of the business system” [21]. The concept of organizational well-being, understood as “the state of health of an organization in relation to the quality of its system of relationships and the degree of physical, psychological and social well-being of the working community,” has also found recognition in decentralized collective bargaining, through company-level agreements aimed at improving the organizational climate and the working environment.

Risk assessment—including interference—is thus the primary tool for interpreting transformations in production models and assessing the effective level of implementation of the required safeguards. This also opens the possibility of introducing prequalification mechanisms in the selection of contractors, based on the effectiveness of the measures adopted [22].

Despite its functional effectiveness, soft law has structural limitations: the lack of binding force and legal sanctions makes it dependent on the will of companies and on reputational dynamics and market pressure [3]. Risks such as greenwashing or social-washing are real, especially in the absence of reliable controls or soft enforcement supported by credible actors [23].

Within the European Union legal system, soft law has assumed an increasingly important role as a flexible regulatory tool complementary to binding law.

The literature on soft law frequently praises these instruments for enhancing governance efficiency through flexible problem solving [14].

Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) clearly distinguishes between binding acts (regulations, directives, decisions) and non-binding acts (recommendations and opinions): “In order to exercise the Union’s competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions. […] Recommendations and opinions shall not have binding effect.” Recommendations, opinions, communications, and guidelines—including those of the European Commission—are therefore fully categorized as soft law instruments, often adopted in particularly dynamic and technical areas, such as competition, state aid, public procurement, and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) policies.

These instruments, while non-binding, significantly influence the interpretation and application of EU law, contributing to the development of shared practices among Member States and businesses. They serve as mechanisms for regulatory coordination and law case harmonization, capable of guiding the conduct of addressees and anticipating future legislative developments [20,24].

At the national level, soft law manifests itself through guidelines from independent authorities (such as AGCM or ANAC), sectoral self-regulatory codes, ministerial circulars, and best practices. While lacking formal binding force, these sources influence administrative and jurisprudential practice, helping to establish shared behavioral and operational standards. A prime example is the Consolidated Law on Health and Safety in the Workplace (Legislative Decree 81/2008), which, while operating within the scope of hard law, leverages typical soft law tools, such as union agreements, codes of ethics and organizational models, from the perspective of corporate social responsibility.

In this context, best practices also become important—organizational and procedural solutions consistent with current legislation, which, while not mandatory, are recognized by the legislator as an integral part of a preventive strategy. The adoption of organizational and management models pursuant to Legislative Decree 81/2008 is essential. The legislative Decree 231/2001, which exempts entities from administrative liability for criminal offenses, represents a further example of soft law rewarded by legislation [19]. Essentially, it is an approach that, by combining mandatory legislation with self-regulatory mechanisms, aims to hold companies, particularly the client, accountable for safety throughout the entire production chain [22,25].

This dynamic is also strongly reflected in the agri-food sector, where soft law has gradually established itself as a fundamental tool for promoting sustainability, transparency and social responsibility. In this context, two key references are the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises [26] and the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains [2]. Although not binding, both documents constitute international standards of reference for companies–multinational and otherwise–operating along the agri-food value chains.

These tools are based on a voluntary due diligence approach, understood as a systematic process aimed at identifying, preventing, mitigating, and reporting environmental, social and governance risks associated with business activities. Adopting these guidelines allows companies not only to strengthen their reputation and social legitimacy (social license to operate), but also to reduce operational, legal and reputational risks, facilitate access to credit, build more resilient relationships with suppliers and anticipate adaptation to more stringent future regulations [18,23].

Taken together, these non-binding tools reflect a now-consolidated trend toward hybridization of agri-food governance, in which private standards, public regulation and soft law coexist and influence each other, within a fluid yet increasingly relevant regulatory framework for guiding corporate conduct and protecting collective interests, such as human rights, environmental protection and food safety. Table 3 summarize the main soft law standards and tools aimed at promoting responsible business conduct, both internationally and domestically. For each reference, the strategic objectives, scope of application and operational tools are highlighted.

Table 3.

Main soft law standards and tools for promoting responsible business conduct (RBC) internationally and domestically.

3.2. Soft Law and Agri-Food Regulation: From the General Concept to the OECD-FAO Guide

In recent years, growing attention to environmental sustainability, human rights protection and corporate social responsibility has fostered the development of soft law tools capable of significantly influencing the regulation of supply chains, particularly in the agri-food sector. This is the context in which the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains (2016) comes into play. It is considered one of the most significant international documents for promoting an ethical, sustainable and inclusive approach along the entire agri-food value chain.

The Guidance is the result of a joint initiative of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), developed between 2013 and 2015 with the contribution of a multistakeholder Advisory Group composed of representatives of governments, businesses, trade unions, NGOs, civil society and academia. This process ensured a balance between public and private interests and ensured a comprehensive, inclusive and shared approach. Following an international public consultation, the Guide was officially adopted in 2016, receiving the support of the G7 and G20 Agriculture Ministers [15].

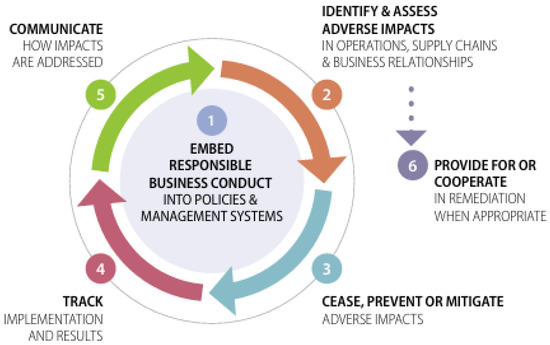

The document represents a sector-specific adaptation of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (updated in 2023) and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights [27], specifically applied to the agricultural sector. The Guide proposes a corporate policy model accompanied by a risk-based due diligence framework, divided into five phases: (1) establishing management systems; (2) identifying, assessing and prioritizing risks; (3) defining mitigation strategies; (4) verifying the measures adopted; (5) reporting and transparent communication as shown in Figure 1. This circular approach allows companies to integrate social responsibility in a structural and progressive manner within their operational activities.

Figure 1.

Due diligence framework. Source: [26] pg. 21.

One of the Guide’s most significant features is its cross-cutting applicability. It addresses a wide range of stakeholders—from large companies to SMEs, cooperatives, investors, governments and civil society organizations—encouraging the horizontal dissemination of best practices. The operational framework was designed to be accessible to small-scale agricultural producers as well, with the aim of guiding the entire supply chain toward more equitable, sustainable and resilient production models. The thematic areas addressed are numerous and relevant: from human rights to decent work, gender equality to food security, public health to environmental protection, animal welfare, land rights, technological innovation and ethical governance.

Of particular note is the Guide’s focus on responsible agricultural procurement, considered a strategic issue in a sector often characterized by long, complex and opaque supply chains [15]. The Guide emphasizes traceability, contractual transparency and collaboration between companies and suppliers, promoting the inclusion of binding contractual clauses, the application of ESG (environmental, social and governance) criteria and the development of training programs to strengthen supplier skills. This cooperative approach distances itself from sanctions-based approaches and focuses on building partnerships that can raise overall standards in the agri-food system.

The Guide also emphasizes the importance of engaging indigenous and vulnerable populations through the adoption of the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), in line with United Nations standards. This step is crucial for rebalancing power relations between companies and local communities, particularly in the Global South, where violations of land and environmental rights are still frequent and often systemic.

The effectiveness and relevance of the OECD-FAO Guide are even more evident in light of recent regulatory developments such as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) (see Par4.1). In this context, the OECD-FAO Guide takes on a strategic value, constituting a reference methodological framework for aligning companies with the new EU legal requirements [6].

In discussing the challenges faced by small and medium-sized enterprises, it is important to highlight how non-binding guidelines can be strategically integrated with binding legislation, enabling SMEs to optimize compliance and promote innovation and foster operational flexibility.

To support the practical implementation of the Guide, the OECD and FAO have developed complementary operational tools, such as the Handbook on Deforestation and Due Diligence in Agricultural Value Chains and the OECD Due Diligence Checker Tool. Furthermore, thanks to collaboration with national bodies—such as CREA in Italy—the Guide has been the subject of dissemination initiatives, training workshops and capacity-building activities, aimed at strengthening the awareness and skills of sector operators.

From a theoretical perspective, the Guide can be interpreted as a paradigmatic example of “informal public authority” (public authority without hard law), according to the conceptual framework proposed by [12]. It is a hybrid instrument, occupying a gray area between binding rules and voluntary instruments: it does not constitute a formal source of law, but it produces significant normative effects on the behavior of businesses and institutions. It is, in essence, a global governance mechanism that exerts regulatory, social and reputational pressure, capable of influencing political and strategic choices [16].

As stated in the preface to the Guide itself: “Although voluntary in nature, this Guidance sets out clear expectations for responsible business conduct across agricultural supply chains, helping enterprises implement risk-based due diligence in line with international standards” [2].

Its effectiveness therefore derives from a combination of institutional, reputational and economic factors: from the authority of the promoting organizations (OECD and FAO), to methodological clarity regarding due diligence, to the growing market focus on ESG criteria. Several companies in the international agri-food sector have publicly endorsed the Guide’s principles, sometimes as a prerequisite for accessing international financing or to protect their image and market competitiveness.

However, the lack of legal obligations and sanctioning mechanisms exposes the Guide to the risk of formal compliance or even greenwashing, particularly in less regulated contexts or where public pressure is weaker. In conclusion, the OECD-FAO Guide represents a virtuous example of soft law, capable of filling—at least in part—the gaps in binding law, provided it is embedded in a coherent, transparent and multilevel regulatory ecosystem.

The OECD-FAO Guidelines for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains provide a due diligence framework that companies can adopt to manage social and environmental risks along their supply chains. These guidelines have been integrated into several European regulations, serving as a benchmark for corporate sustainability. For example, the EU Directive 2024/0295 on corporate sustainability due diligence recognizes agriculture as a high-impact sector and explicitly references the OECD-FAO Guidelines as sectoral standards for due diligence [2]. Furthermore, Directive 2019/633/EU, aimed at protecting farmers and other suppliers in agricultural and food supply chains from unfair trading practices, aligns with the recommendations of the OECD-FAO Guidelines. This alignment underscores the importance of adopting responsible due diligence practices to ensure sustainability and fairness in agricultural supply chains [2,28].

3.3. Responsible Supply Chain and Voluntary Due Diligence: The Nicoverde-Nicofrutta Case

Among the most emblematic examples of voluntary due diligence in the agri-food sector is the case of the Italian company Nicofrutta and its Costa Rican subsidiary Nicoverde, active in the sustainable production and marketing of pineapples and other tropical fruits.

The case presented below is based on a face-to-face interview with the company’s sales manager, who also serves as the contact for the company’s social management system. This semi-structured interview provided the data and insights underlying the analysis reported in this article.

Since 2016, the company has been pursuing a voluntary alignment process with the international standards set by the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Agricultural Sector, implementing a management system inspired by the five pillars of due diligence: corporate policies, risk identification, mitigation measures, verification, and transparency.

The project, co-financed through the German “develoPPP program” in collaboration with GIZ (German Agency for Development Cooperation), was structured on multiple levels: empowerment of local producers, agronomic innovation, biodiversity protection, social inclusion and agricultural decarbonization. The partnership involved national and international institutions, including the German Ministry of the Environment, the FAO, the National Technical University of Costa Rica and United Nations agencies such as the BIOFIN–PNUD Program.

As shown in Table 4, which summarises the main results obtained by Nicofrutta, one of the most significant results was the creation of a network of over 120 certified small-scale producers, supported by trained technical assistance to facilitate the transition to sustainable agricultural models.The project included over 340 training activities, with 44% of participants being female, promoting the dissemination of practices such as the reuse of agricultural residues, the use of bioinputs, pesticide-free production and integrated biodiversity management.

Table 4.

Key results of the Nicoverde-Nicofrutta initiative.

On the environmental front, Nicoverde has distinguished itself through its adoption of agroecological and regenerative practices. The company has invested in a laboratory for breeding beneficial microorganisms, replacing chemical fertilizers, achieving “Zero Pesticide Residue” certification in 2020. The use of plant waste and decomposing microorganisms has enabled the reintegration of 240 tons of organic matter per hectare, helping to sequester over 15,000 tons of CO2 in agricultural soils and resulting in the first certified decarbonized pineapple. Table 5, for each phase outlined in the guidance, the main activities undertaken, the results achieved, and the challenges faced, including any lessons learned.

Table 5.

The 5 steps of OECD-FAO due diligence in the Nicoverde-Nicofrutta case.

The governance model has also been made effective thanks to multi-stakeholder dialogue, the development of a simplified Internal Control System (ICS) and the inclusion of producers in corporate decisions. This case study demonstrates how the voluntary adoption of OECD-FAO standards can strengthen corporate resilience, improve access to premium markets and attract certifications of excellence such as Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, and Global G.A.P. These tools have allowed Nicoverde to enhance its product in terms of transparency, ethics and sustainability, building stable relationships with European and North American markets.

More specifically, the following table summarizes the practices adopted by the company in relation to the five steps of due diligence according to the OECD-FAO Guide, highlighting concrete examples of application for each step, the results achieved, as well as the main challenges encountered and lessons learned during the implementation process.

The experience has received significant recognition: the Blue Flag eco-label (Biodiversity category), the role of pilot company in the Global G.A.P. BioDiversity module and the support of numerous academic and government institutions. According to Luciano Nicolis, president of Nicofrutta, “this alliance represented a paradigm shift: from reliance on agrochemicals to an agriculture integrated with biodiversity, respectful of people and the environment.”

The Nicoverde-Nicofrutta case demonstrates that voluntary due diligence, when implemented through participatory models and supported by public policies, can generate significant environmental, social and economic impacts, even in the absence of stringent legal obligations. However, the effective adoption of these practices requires significant upfront investments, strong corporate leadership, widespread training and stable public–private partnerships.

Looking ahead, the implementation of the European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) will mark a turning point, transforming these approaches from voluntary best practices into binding legal obligations for many European companies. The Nicoverde model can therefore represent a guiding case in the regulatory, ethical and environmental transition of global agri-food supply chains.

4. Hard Law and Responsibility in Agri-Food Supply Chains

In international law, the term hard law refers to binding legal norms that impose specific obligations on the parties to whom they are addressed. These norms may derive from international treaties, established customs or internationally recognized general principles of law (Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice) and their violation may result in legal liability [29].

In a broader sense, hard law represents the body of legislation adopted by competent authorities (states, the European Union, international organizations) that establishes clear, certain, and sanctionable obligations. Its main characteristics are:

- Mandatory: the provisions must be complied with no margin for discretion.

- Sanctions: violations entail legal consequences (fines, bans, operational restrictions).

- Legal responsibility: non-compliant actors can be prosecuted under civil, administrative or criminal law.

In the agri-food sector, hard law has assumed an increasingly central role, regulating aspects such as product safety, labeling, international trade, consumer protection and, more recently, environmental and social sustainability [30]. Although it guarantees legal certainty and effective oversight mechanisms, hard law also presents critical issues related to its rigidity, often lengthy decision-making times and excessive regulatory technicality [31,32]. Table 6 illustrates the key strengths and limitations of hard law, highlighting how its stability and authority can come at the cost of adaptability, especially for SMEs.

Table 6.

Advantages and Limitations of Hard Law.

Over time, European agri-food legislation has shifted from a technical focus on food safety (e.g., the 2004 Hygiene Package, regulations on labeling additives and GMOs) to a broader, more integrated approach that includes human rights, working conditions, environmental protection and transparency [34,35].

Since 2010, there has been a growing focus on production ethics, also thanks to international regulatory action (e.g., ILO standards, OECD guidelines) and to the first national laws on mandatory due diligence (Germany, France). At the European level, the Green Deal and the Farm to Fork strategy have promoted further measures aimed at building sustainable supply chains, reducing pesticide use, combating deforestation, and encouraging corporate social responsibility [36].

Today, the European regulatory framework (Table 7 and Table 8) is enriched with key instruments that strengthen the legal dimension of corporate sustainability:

Table 7.

Main standards and hard law instruments to promote responsible business conduct (RBC) within the European Union.

Table 8.

Main standards and hard law instruments to promote responsible business conduct (RBC) at the national level.

- Directive (EU) 2022/2464–CSRD [5]: requires companies to publish detailed reports on environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance;

- Directive (EU) 2024/1760–CSDD [6]: imposes due diligence obligations along the entire value chain, with a focus on human rights and the environment;

- Directive (EU) 2024/825 [37]: Green Claims: prohibits vague or unverifiable environmental claims, fighting greenwashing.

These transformations are taking place in an increasingly complex and interconnected global context. Agri-food supply chains involve actors distributed globally, often operating in countries with differing regulatory standards. Regulatory and reputational pressures on governments and businesses are growing, also due to climate change, the exploitation of child labor and demands for transparency from informed consumers and ESG investors.

Finally, instruments such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights [27] and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises have helped to define a framework for shared responsibility along global supply chains.

4.1. Hard Law in Directive (EU) 2024/1760 on the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD)

Directive (EU) 2024/1760, known as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), represents a turning point in the evolution of European hard law on sustainability and corporate responsibility. Approved on 13 June 2024, and entering into force on 25 July of the same year, it establishes a binding legal framework requiring large companies, both European and non-EU, operating in the single market to adopt structured due diligence procedures to identify, prevent, mitigate and, if necessary, remediate actual or potential adverse impacts on human rights and the environment along the entire value chain.

The text of the directive highlights the European Union’s intention to strengthen the principle of extended corporate responsibility, overcoming the traditional distinction between internal and external activities. The CSDDD extend CSR obligations, transforming voluntary responsibility into binding legal obligations, thus strengthening corporate governance and environmental and social due diligence [38]. In this sense, companies are no longer required to ensure compliance only with their own direct operations, but also with those of their suppliers and business partners, including subcontractors and those further along the supply chain [39]. Due diligence becomes a cornerstone of modern CSR, with operational and governance implications across global value chains [40].

The directive is structured around five strategic objectives: integrating sustainability into corporate governance; preventing and mitigating environmental and social risks through a proactive and systemic approach; extending corporate responsibility throughout the value chain; ensuring effective access to justice for victims of violations and, finally, promote the transition to climate neutrality in line with the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement.

One of the most innovative and significant aspects of the CSDDD is the requirement for companies to monitor their entire supply chain, which includes not only direct suppliers with whom they have a contractual relationship, but also indirect suppliers, such as raw material producers or subcontractors. From this perspective, companies must be able to map the risks associated with their global supply chain, identify areas of greatest exposure to human rights or environmental violations and implement appropriate preventative or corrective measures.

The due diligence process, as outlined by the directive and inspired by the OECD Guidelines for Responsible Business Conduct, is divided into six phases: integrating due diligence into corporate governance policies and systems; identifying and assessing risks along the value chain; adopting measures to prevent or mitigate negative impacts; monitoring the effectiveness of the measures adopted; publicly communicating strategies and results and, finally, establishing accessible grievance and redress mechanisms for potentially affected parties. From this perspective, due diligence is believed to be a lever for sustainable corporate governance, highlighting its relevance in an evolving regulatory and operational environment [40]. In addition to the core procedural due diligence requirements, the directive introduces additional specific obligations that strengthen the legal framework. These include the requirement to draw up a climate transition plan, including intermediate and final decarbonization targets, in line with the EU international commitments. Particular attention is paid to the role of governance: the board of directors is required to ensure that due diligence is integrated into strategic decisions and is also taken into account in executive remuneration systems. Companies that fail to comply with these obligations may be subject to civil liability for damages caused, unless they demonstrate that they have taken all reasonable measures to prevent violations. Each Member State will also be required to establish a national supervisory authority, tasked with monitoring companies’ compliance with these obligations, applying sanctions and imposing corrective actions where necessary.

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) provides for a phased implementation approach, taking into account the size and turnover of companies, to ensure a sustainable and realistic transition to the new due diligence requirements. This means that not all companies will be subject to the directive’s obligations immediately: application will be staggered over time and differentiated by size threshold (Table 9).

Table 9.

Phases of gradual implementation based on size and turnover.

As shown in the table, large companies will be the first to be required to comply with the directive by implementing a structured due diligence system across the entire value chain. They will also be required to include the environmental impacts of climate change in their corporate strategy. Medium-sized and large companies will be affected starting in 2028; therefore, they will have time to adapt by gradually implementing the required policies and systems (e.g., sustainability governance, supplier mapping, audits, stakeholder engagement). For smaller companies, with more than 1000 employees or €450 million, a proportionate approach is envisaged, so that the obligations are not excessively burdensome for companies (while maintaining the responsibility standards, they will have to follow the same guidelines, but will have a more extended timeframe as they will be affected starting in 2029). Non-EU companies that generate significant revenue in the European Union are also included, according to equivalent thresholds. For businesses, this gradual approach allows them to prepare by following a process of adaptation without having immediate obligations, giving them the opportunity to better plan the resources, strategies, and tools needed to achieve the objective by the expected entry into force.

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) primarily concerns large companies, but it will also have significant repercussions on Italian SMEs, i.e., companies with fewer than 250 employees and a turnover of ≤50 million euros, even though they are not directly required to comply with the directive. However, it should be noted that even though they are exempt from the direct obligation, many Italian SMEs are part of the value chains (supply chains) of large companies that will be required to comply with the directive. Indeed, companies subject to due diligence obligations will also be required to assess the social and environmental risks of their suppliers and subcontractors, including SMEs. Therefore, SMEs may be involved in due diligence processes as suppliers of raw materials or services, subcontractors and contractors. This development could represent an opportunity for SMEs to enhance their reputation and sustainability focus. However, it will likely also entail additional costs for compliance with more stringent standards. In this scenario, for Italian SMEs, even if they are not required to implement the provisions of the CSDDD, it becomes strategic to take steps to move in this direction.

The agri-food sector is particularly impacted by this regulation, both due to the intrinsic characteristics of its supply chains—often long, complex and connected to third countries—and the presence of high risks associated with phenomena such as illegal deforestation, child labor, non-compliant pesticide use, or soil degradation. Supply chains such as cocoa, coffee, soy, meat and palm oil represent emblematic cases in which environmental and social due diligence will need to be strengthened. In this context, agri-food companies will be required to ensure the traceability of raw materials, more rigorously monitor their agricultural suppliers, and ensure compliance with sustainable practices, possibly integrating international standards such as Fair Trade or the Rainforest Alliance into their management systems [41].

Although the directive imposes rigorous obligations, it also offers significant opportunities in terms of enhancing corporate reputation, strengthening consumer trust and providing privileged access to sustainable investments. However, the operational challenges it entails cannot be overlooked, including increased compliance costs, the need to review contracts and internal processes and the risk of legal dispute in the event of non-compliance.

In conclusion, the CSDDD marks a significant transformation in the European understanding of corporate responsibility. For the agri-food sector, in particular, this is not just a regulatory adjustment, but a profound cultural evolution, requiring companies to take an active role in promoting more ethical, transparent and sustainable production models. Integrating due diligence into corporate strategy is no longer a voluntary choice, but rather a legal obligation and a strategic opportunity to address global challenges competitively and responsibly. Table 10 summarizes the main obligations and opportunities for agri-food companies. Indeed, companies can use due diligence as a lever to transform the governance of global supply chains, aiming to reduce negative social and environmental impacts [26].

Table 10.

Obligations and opportunities introduced by the CSDDD for agri-food companies.

4.2. Hard Law in the Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

Directive (EU) 2022/2464, known as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), is one of the main regulatory instruments adopted by the European Union to strengthen corporate transparency and responsibility in environmental social, and governance (ESG) matters. Approved in December 2022 and entering into force on 5 January 2023, the CSRD replaced Directive 2014/95/EU (Non-Financial Reporting Directive, NFRD), significantly expanding its scope and the level of detail required in non-financial reporting [42].

This directive is part of the policies outlined by the European Green Deal and the Sustainable Finance Action Plan, with the aim of mobilizing private capital for sustainable investments and promoting a fair and transparent transition of the European economy [43]. The CSRD was created to address some critical issues that emerged in the previous regulatory system, particularly the vagueness of reporting requirements, poor data comparability and the limited number of required companies. Indeed, the CSRD, consistent with the Green Deal and the Sustainable Finance Action Plan, introduces mandatory standards (ESRSs), improves data quality and comparability and integrates tools such as life cycle analysis [44].

The directive is based on four strategic objectives. First, it aims to mandate structured and standardized ESG transparency, in order to provide stakeholders—including investors, supervisory authorities, financial institutions and citizens—with reliable, comparable and verifiable information. Second, it aims to strengthen the role of companies in the sustainable transition, encouraging them to integrate sustainability into governance, business strategies and control systems. The third objective is to facilitate responsible investment choices through certified data that allows for a clearer identification of sustainability-related risks and opportunities. Finally, it promotes the evolution of corporate culture towards greater accountability, consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). Therefore, it can be argued that the directive represents a significant step towards greater transparency and standardization of non-financial information, aiming to improve the comparability and reliability of ESG data [45].

To ensure robust and harmonized reporting, the CSRD requires the adoption of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs), developed by EFRAG (European Financial Reporting Advisory Group) and approved by the European Commission. These standards cover the full spectrum of ESG factors and are subject to periodic updates. A central element of the new system is the principle of double materiality (“The double materiality principle considers both the impact materiality (how the undertaking affects the environment and people) and financial materiality (how sustainability matters affect the undertaking’s development, performance and position).”, European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), Document: ESRS 1—General Requirements, paragraph 40 et seq.), according to which companies must provide information on both the impact of ESG issues on their financial performance (financial materiality) and the impact of their activities on the environment and society (impact materiality) [46]. This reporting must be integrated into the annual report and verified by independent auditors. Initially, a limited level of assurance will be required, which may evolve to reasonable assurance as the regulation is gradually implemented. Reports must be prepared in a digital format readable by automated systems, using structured markup language, to facilitate data traceability and analysis by market operators and public authorities [45,47,48].

From a regulatory harmonization perspective, the CSRD is designed to integrate with other instruments of the European legislative framework, particularly the Taxonomy Regulation, the Corporate Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the SFDR, contributing to the construction of a coherent, interoperable reporting system based on the principle of extended responsibility across the entire value chain [49].

The scope of the directive is significantly broader than the NFRD. According to European Commission estimates, it will increase from approximately 11,000 companies involved to over 50,000. The extension will be gradual: from 2025, large companies already included in the NFRD (over 500 employees) will be subject to it, followed in 2026 by all other large companies that meet at least two of the following criteria: more than 250 employees, €40 million in annual turnover, or €20 million in total assets. SMEs listed on regulated markets will also be affected by 2027, with the possibility of opting out until 2028. From 2029, the regulation will also apply to non-European companies that generate more than €150 million in annual turnover in the EU and have a significant branch or subsidiary in the Union.

Although many unlisted SMEs are formally exempt from direct obligations, they will still be affected indirectly. Obliged companies will be required to collect ESG data from their suppliers and business partners along the entire supply chain, thus generating a “cascade” effect that will also encourage small and medium-sized enterprises to gradually adapt to sustainability standards.

In the agri-food sector, the impact of CSRD is expected to be particularly significant. Companies operating in this sector will be required to provide detailed and transparent reporting on the main ESG aspects affecting the production cycle, supply chains and agricultural practices. From an environmental perspective, the required information will include data on land use, biodiversity conservation, use of fertilizers and pesticides, direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption and climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies [50].

From a social perspective, companies will be required to document working conditions throughout the supply chain, with particular attention to the rights of seasonal and migrant workers and demonstrate the adoption of policies to combat child and forced labor. Furthermore, they will need to report on their commitment to local communities, particularly in rural areas, with actions focused on animal welfare, food safety, food waste prevention and the promotion of conscious consumption patterns.

To comply with the CSRD, companies will also need to integrate appropriate governance tools, develop internal systems for collecting and verifying ESG data and use recognized certification standards, such as Global G.A.P., Fairtrade, ISO 14001 [51], or organic farming certifications.

Although complying with the new regulation requires initial investments in human resources, skills and technological infrastructure, well-structured ESG reporting can translate into significant competitive advantages. It helps improve corporate reputation, increase consumer trust and attract green capital. Furthermore, regulatory compliance helps prevent fines and legal disputes, reducing operational and reputational risks in a market increasingly focused on transparency and accountability.

In the agri-food sector, the joint application of the CSRD and the CSDDD involves more than just a formal change in business processes; it also implies a substantial shift in organizational culture. While the CSDDD requires companies to adopt proactive behaviors in sustainability management throughout the value chain, the CSRD requires that these actions be measured, verified and communicated in a transparent and standardized manner. From this perspective, the two directives complement and reinforce each other, helping define a new regulatory and management paradigm for sustainability in European agri-food supply chains.

4.3. Implementation of the CSDDD and CSRD: The Lavazza Case

Lavazza is an Italian multinational leader in the production and distribution of coffee, with a global presence in over 140 countries. Its activities cover the entire production chain, from the selection of raw materials to marketing and after-sales services. Over time, Lavazza has consistently demonstrated its commitment to sustainability, which it pursues through an evolutionary and gradual process of integrating social, environmental and economic sustainability into its corporate strategy. This journey has been structured into several phases, combining voluntary practices with progressive regulatory adjustments. Since 2015, Lavazza has voluntarily published its annual Sustainability Report, in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards and subject to a limited review by an external auditor [52,53,54]. In effect, it has anticipated market expectations and binding regulations to demonstrate its social and environmental commitment. Since 2019, it has focused on strengthening ESG by establishing a Sustainability Department with cross-functional responsibility. It has also integrated sustainability into strategic planning, supply chain processes and risk management systems. This has been complemented by increased attention to data verification involving external auditors.

The Lavazza Group has initiated a structured process to comply with both Directive (EU) 2024/1760 on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD) and Directive 2022/2464/EU on Corporate Sustainability Reporting (CSRD). Although not yet formally required, Lavazza has anticipated many of the required requirements, demonstrating a high level of commitment to ESG.

The Directive (CSDDD) requires large European companies to adopt due diligence systems aimed at identifying, preventing, mitigating and eliminating adverse impacts on human rights and the environment along their global value chains, integrate sustainability into corporate strategies, establish complaints procedures, conduct ESG risk analysis, and ensure transparent and responsible governance.

Lavazza, like many other companies operating in the EU, is working to integrate the requirements of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) into its business model. Although the directive is not yet fully implemented, the company has already adopted measures and policies that align with the core principles of the CSDDD. Among these, particular attention has been paid to due diligence, risk management related to environmental, social and governance impacts and transparency.

One of the core obligations of the CSDDD is the need to identify risks associated with business operations and the supply chain that may have negative impacts on human rights, the environment or other social issues. Lavazza has mapped its supply chain to identify risks related to human rights and environmental impacts. Its main raw material, coffee, comes from countries with complex human rights and environmental sustainability situations. Therefore, Lavazza has implemented audit programs to monitor compliance with ethical standards throughout the supply chain. The CSDDD requires companies to not only identify risks but also proactively prevent and mitigate them, taking timely action to avoid harm. With this in mind, Lavazza has collaborated with international organizations to develop social development projects in the regions where its coffee is grown. For example, it has promoted the adoption of agricultural practices that not only protect the environment but also improve farmers’ living and working conditions. This perspective also includes its commitment to using certifications such as Fair Trade and Rainforest Alliance, which help prevent human rights and environmental violations in its supply chains. Of particular importance for the Lavazza Group has been the integration of risk analysis into its business model through the adoption of the Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) framework, which, since 2022, has also integrated ESG risks. Specifically, ESG risk analysis allows for the study and categorization of risks within macro-areas, each of which entails specific risks. In 2024, risks were identified in six macro-areas: sustainable supply chain; human development, well-being and retention; health and safety; climate change; land use, deforestation and biodiversity; and emerging regulations. The final macro-area was added in 2024 to encompass all risks related to compliance with new European regulations, taking into account the growing complexity of the environmental and social regulations the company is required to comply with. These include the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR), which requires supply chain controls to prevent commodities from coming from deforested areas, and the Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR), which imposes stringent targets for reducing packaging waste and adopting sustainable materials. A key aspect of the CSDDD concerns product traceability and sourcing transparency. To this end, Lavazza publishes an annual Sustainability Report detailing its initiatives and achievements in social and environmental sustainability. These reports provide information on risks associated with corporate practices, supply chain management, and future commitments. Furthermore, Lavazza is integrating advanced technologies to ensure the traceability of coffee from the plantation to the end consumer, ensuring that all production stages comply with sustainability standards. Overall, Lavazza has made significant progress in meeting the requirements of the CSDDD, with a strong commitment to social, economic and environmental sustainability, although further adjustments to the specific guidelines will be necessary once the directive is fully adopted.

The company also conducted a gap analysis, with the support of external consultants, to identify areas for improvement with respect to the new directive in order to prepare for the transition in the most efficient way. This analysis confirmed that the company was already starting from a solid structure in terms of data collection and ESG, highlighting the need to strengthen certain functions. ESG management is centralized and supported by a global data collection and validation system, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities [55]. Although there is currently no formal internal audit, the process already complies with the traceability and accountability criteria required by the CSDDD [56,57].

Another key element of the Directive is stakeholder engagement and the provision of accessible complaint mechanisms. In this regard, Lavazza is in the process of integrating more structured procedures to align them with new regulatory requirements, which require traceability, continuous feedback and documentation of outcomes [58,59,60,61]. A final aspect worth noting is that the CSDDD requires the integration of sustainability into corporate governance, with directors directly responsible for overseeing due diligence. In this context Lavazza, through its ESG department, divided into four units (environment, supply chain, social sustainability, reporting), has already begun formalizing roles and processes to build a compliant governance structure.

Regarding Directive (EU) 2022/2464 (CSRD), it requires large European companies, such as Lavazza, to prepare a certified sustainability report compliant with the ESRSs, based on the principle of dual materiality and subject to independent external verification. This led to an update of the double materiality analysis:

- Impact materiality (how the company impacts society and the environment).

- Financial materiality (how ESG factors impact company performance).

Furthermore, the system for collecting and managing quantitative ESG data has been strengthened with digital tools and new metrics and internal protocols have been developed to engage the global supply chain in the collection of environmental and social information (e.g., audits of coffee suppliers, traceability of deforestation). To comply with CSRD obligations by the deadlines set in the 2023 Sustainability Report (published in 2024), Lavazza has already integrated several elements required by the CSRD, specifically:

- ESG indicators aligned with the European ESRSs;

- structured reporting by thematic areas (E, S, G) with measurable objectives;

- launch of climate transition plans consistent with the Paris Agreement.

The company has undertaken a structured process to adapt to the new European directives, particularly the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which imposes more stringent and standardized requirements for ESG (environmental, social, and governance) reporting.

Building on many years of experience with voluntary reporting based on the GRI Standards, Lavazza has strengthened its data collection and internal governance systems to ensure compliance with the new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs) introduced by the CSRD. The indicators included in the integrated report that adopts the ESRS principles provide detailed coverage of the three areas of sustainability: environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G). These indicators are standardized and will become mandatory for large European companies starting in 2024–2025 (Table 11).

Table 11.

Lavazza indicators already aligned with the ESRSs 2023.

Many performance indicators stated in the report, especially those related to the environment and governance, are consistent with the ESG metrics required by the ESRSs. Therefore, the path undertaken is certainly substantially aligned.

Within the broader framework of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs), which require companies to transparently report their environmental and social impacts, including those along the value chain, Lavazza has launched numerous projects in coffee-producing countries such as Ethiopia, Colombia and Honduras, with the aim of strengthening the resilience of local communities, promoting economic justice, and improving working conditions along the supply chain (Table 12).

Table 12.

Lavazza projects with cooperatives for fair prices and safe working conditions.

All projects aim to ensure fair prices and economic stability, improve working conditions, implement infrastructure, and promote ESG certifications (Rainforest Alliance) to enhance coffee quality and foster production diversification and climate resilience.

The analysis of the Lavazza case highlights how the company initiated a structured process of integrating sustainability into its business processes well in advance, anticipating many of the requirements introduced by the CSRD and the ESRSs.

In summary, Lavazza represents a virtuous example of a company that has successfully transformed the regulatory challenge into a strategic lever that reinforces its commitment to a sustainable business model—a lever for strengthening ESG, stakeholder dialogue and transparency along the value chain. This approach offers several opportunities: strengthening its reputation on the global market; a competitive advantage in international agri-food supply chains, thanks to the ability to promptly respond to transparency and traceability requirements; access to sustainable markets and financing; improved integration between governance and sustainability and strengthening the trust of all stakeholders.

At the same time, however, several critical issues emerge: the need to structure effective complaint mechanisms; adapting governance to new responsibilities and the complexity of monitoring the entire value chain globally. Furthermore, there is the technical and administrative complexity of fully aligning with the ESRSs, which requires high measurement and traceability standards, including social data and across the entire supply chain. This also requires consolidating internal and external information flows, especially with local suppliers in low-digital environments or in socially risky areas. Finally, there is the increased costs and resources required to ensure compliant, complete and auditable reporting. In short, Lavazza confirms its position as a virtuous example of sustainable transition, but full alignment will require ongoing investments in organizational capabilities, digitalization, and corporate culture.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

A complex and fragmented reality like the current one does not seem manageable solely through the necessary regulatory provisions. It therefore seems appropriate to emphasize the trend toward a system increasingly based on the synergy between hard law and soft law instruments, finding a point of convergence in the now essential obligation to assess all risks along the supply chain.

The analysis demonstrates that soft law and hard law are not mutually exclusive, but can constitute complementary elements of a more dynamic regulatory system, capable of balancing flexibility and mandatory nature. The coexistence among moral suasion and legal obligation paves the way for a hybrid regulatory model, in which the social legitimacy of rules is also built through non-binding yet culturally impactful instruments.

Although soft law poses the risk of weakening legal certainty, it can serve as a regulatory laboratory, capable of anticipating the evolution of positive law, stimulating innovation and adaptation in rapidly changing contexts.

In particular, integrating human rights into corporate strategies, especially in the agri-food sector, represents a complex challenge that requires vision, ongoing commitment and profound cultural change. The FAO-OECD Guidance remains a fundamental point of reference for guiding businesses toward more sustainable, inclusive and human rights-respecting practices, while promoting shared responsibility along the entire value chain.

Despite progress made, significant challenges remain, including:

- Regulatory fragmentation, which hinders the uniform adoption of sustainable practices globally.

- Internal resistance, related to the required investments and the necessary change in organizational and cultural models.

- Transparency, traceability, and compliance challenges, especially in managing complex and multifaceted supply chains, where compliance with new regulatory provisions requires significant efforts for companies in terms of adapting control and reporting systems.

At the same time, the agricultural sector is attracting a growing number of investments, particularly in regions such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where agricultural social capital is still limited. Responsible investments in these contexts not only meet the growing global demand for food, but also contribute to poverty reduction and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. In this context, the Guide emphasizes the key role of business in promoting a more just and inclusive economy.

The evolution from soft law (guidelines, voluntary standards) to hard law (legally binding rules) in the agri-food sector is therefore essential to ensure transparency, accountability, and effective sustainability throughout the entire production chain. For agri-food supply chains, hard law represents a tool for ensuring that sustainability is verifiable and accountable, creating greater fairness in competition between companies with a greater focus on quality and transparency. This strengthens consumer trust and protects the environment and human rights. This transition, however, requires significant investments in technology, internal training, governance structures, audit processes and technical consultancy.

Specifically, the joint implementation of the CSRD and the CSDDD in the agri-food sector represents a significant cultural and operational evolution for companies, where sustainability becomes a key component of corporate strategy and the ability to compete in the long term. The Lavazza case has highlighted how virtuous behaviors can transform the evolution of the regulatory landscape into a strategic lever for enhancing a sustainable business model and achieving significant benefits, such as strengthening its competitive position with both consumers and investors. This approach also helps enhance the brand’s image, facilitate access to capital and attract ESG-oriented investors. Furthermore, establishing more transparent and stable relationships along the supply chain, particularly in coffee-producing countries, represents a competitive advantage over other companies in the sector. Despite these positive aspects, there are some critical issues to highlight. These include:

- Technical and management complexity of the compliance process.

- High measurement and traceability standards, including for social data and along the supply chain.

- Difficulties in information flows, especially with suppliers in contexts with limited digitalization or at social risk.

- Increased costs and the need for greater resources to ensure complete, compliant, and verifiable reporting.

However, the future of sustainability in the agri-food sector will not depend solely on businesses. An active role from public policies will be essential, providing consistent incentives, operational tools and effective verification mechanisms. Consumers, with their increasingly informed choices and large-scale retail trade (GDO), with its power to select and pressure responsible practices, are other key players in this transformation.

Looking to the future, some promising perspectives emerge:

- Strengthen international collaboration, promoting shared standards through cooperation networks between countries, institutions and businesses.

- Promote technological innovation, leveraging digital tools and monitoring platforms to improve traceability and the effectiveness of controls.

- Foster a cultural shift, raising awareness among producers and consumers of more ethical, responsible and environmentally responsible economic models.

In this context, shared responsibility along the supply chain—understood as a collective commitment between companies, governments, consumers, and civil society—can represent a crucial lever for a profound transformation of the agri-food system, capable of combining competitiveness, fairness and sustainability.

Through the adoption of international standards, greater operational transparency and ongoing dialogue with stakeholders, companies can not only mitigate the risks associated with human rights violations, but also actively contribute to building a more equitable, resilient and sustainable agri-food system.

It is essential to recognize that these challenges and opportunities do not only concern large multinationals: small and medium-sized enterprises also play a crucial role, especially when operating as part of global supply chains or aiming to enter markets where sustainability and human rights issues are increasingly central. Our findings suggest that hybrid governance frameworks, which integrate soft and hard law, can serve as effective policy tools to advance sustainability when supported by coherent regulation, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and adequate implementation mechanisms. In conclusion, this study can offer useful insights to SMEs interested in deepening their due diligence and evaluating potential implementation along their supply chains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.; methodology, L.B.; software, L.B. and D.S.; formal analysis, L.B. and D.S.; investigation, L.B. and D.S.; resources, L.B. and D.S.; data curation, L.B. and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation L.B. And D.S.; writing—review and editing, L.B. and D.S.; visualization, L.B. and D.S.; supervision, L.B. And D.S.; project administration, L.B. and D.S.; Validation L.B. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- European Commission Sustaining Our Quality of Life: Food Security, Water and Nature|Legislative Framework for Sustainable Food Systems. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- OECD-FAO. Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-92-64-25095-6. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W.; Snidal, D. Hard and Soft Law in International Governance. Int. Organ. 2000, 54, 421–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, F.; Fanzo, J.; Frison, E. The Role of Food and Nutrition System Approaches in Tackling Hidden Hunger. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj/eng (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- European Parliament. Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Regulation (EU) 2023/2859 (Text with EEA Relevance). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj/eng (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Trubek, L.G. New Governance and Soft Law in Health Care Reform. Indiana Health Law Rev. 2006, 3, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, F. Soft Law and Institutional Practice in the European Community. In The Construction of Europe: Essays in Honour of Emile Noel; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M.; Westhaus, M.; Morana, R. Conducting a Literature Review—The Example of Sustainability in Supply Chains. In Research Methodologies in Supply Chain Management; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]