Does Quality of Life Influence Pro-Environmental Intention? An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour

Abstract

1. Introduction

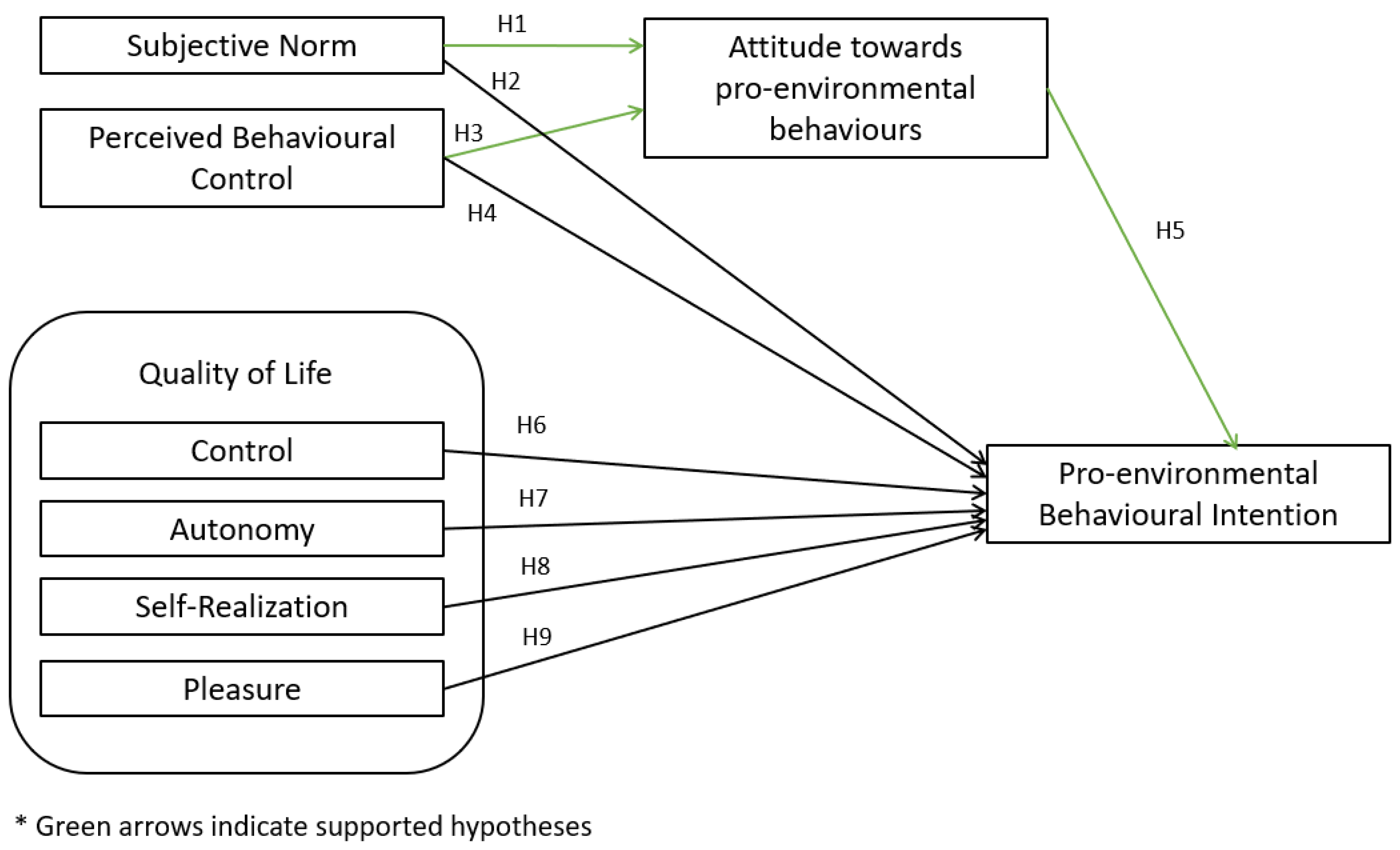

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour and Pro-Environmental Behaviour

2.2. Subjective Norm

2.3. Perceived Behavioural Control

2.4. Attitude

2.5. Quality of Life

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sample and Procedures

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

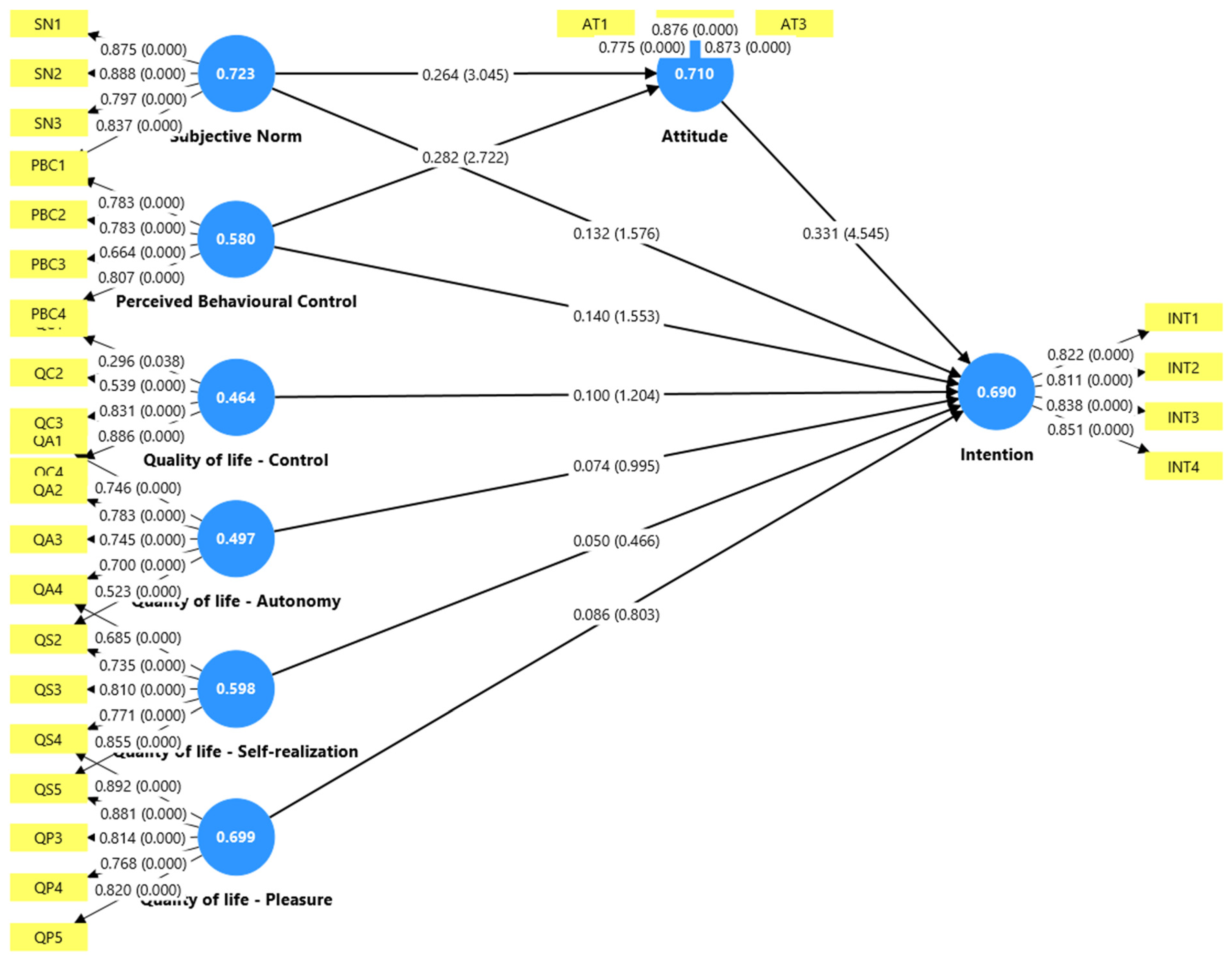

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

6. Implications and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michaelis, L.; Wilk, R.R. Consumption and the Environment. Soc. Cult. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2005, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.I.M.; de Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How Do I See Myself? A Systematic Review of Identities in Pro-environmental Behaviour Research. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 108–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGI. Insights Consumption: Patterns, Impacts, and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.graygroupintl.com/blog/author/ggi-insights (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- United Nations. Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Nguyen, H.V.; Le, M.T.T.; Pham, C.H.; Cox, S.S. Happiness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behaviors. J. Econ. Dev. 2024, 26, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; De Beer, L.T.; Saunders, S.G. Social and Personal Factors Influencing Green Customer Citizenship Behaviours: The Role of Subjective Norm, Internal Values and Attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-Environmental Behavior of University Students: Application of Protection Motivation Theory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Amirudin, A.; Rahadi, R.A.; Nik Sarah Athirah, N.A.; Ramayah, T.; Muhammad, Z.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Saputra, J.; Mokhlis, S. An Investigation of Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Sustainable Development in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastuti, K.P.; Arisanty, D.; Muhaimin, M.; Angriani, P.; Alviawati, E.; Aristin, N.F.; Rahman, A.M. Factors Affecting Pro-Environmental Behaviour of Indonesian University Students. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2024, 21, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Perales, I.; Valero-Gil, J.; Leyva-de la Hiz, D.I.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C. Educating for the Future: How Higher Education in Environmental Management Affects pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) and Environmental Concerns on pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). J. Clean Prod. 2023, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Khaleghi, B. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting the Behavioral Intentions of Iranian Local Communities toward Forest Conservation. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1121396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Hameed, I.; Akram, U. What Drives Attitude, Purchase Intention and Consumer Buying Behavior toward Organic Food? A Self-Determination Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2572–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chan, T.J.; Suki, N.M.; Kasim, M.A. Moderating Role of Perceived Trust and Perceived Service Quality on Consumers’ Use Behavior of Alipay e-Wallet System: The Perspectives of Technology Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 2023, 5276406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.H.; Zhongfu, T.; Irfan, M.; Işık, C. Do Environmental Knowledge and Green Trust Matter for Purchase Intention of Eco-Friendly Home Appliances? An Application of Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 37762–37774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Nakayama, S.; Yamaguchi, H. Using the Extensions of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) for Behavioral Intentions to Use Public Transport (PT) in Kanazawa, Japan. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 17, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Hou, X.; Feng, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, J. Subjective Norms, Attitudes, and Intentions of AR Technology Use in Tourism Experience: The Moderating Effect of Millennials. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkorful, V.E.; Hammond, A.; Lugu, B.K.; Basiru, I.; Sunguh, K.K.; Charmaine-Kwade, P. Investigating the Intention to Use Technology among Medical Students: An Application of an Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Public Aff. 2020, 22, e2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Badejo, A.; Carlini, J.; France, C.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Knox, K.; Pentecost, R.; Perkins, H.; Thaichon, P.; Sarker, T.; et al. Predicting Intention to Recycle on the Basis of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, e1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit Kumar, G. Framing a Model for Green Buying Behavior of Indian Consumers: From the Lenses of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.M.; Ha, N.T.; Ngo, T.V.N.; Pham, H.T.; Duong, C.D. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives and Green Purchase Intention: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, H. Merging Theory of Planned Behavior and Value Identity Personal Norm Model to Explain Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budovska, V.; Torres Delgado, A.; Øgaard, T. Pro-Environmental Behaviour of Hotel Guests: Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Social Norms to Towel Reuse. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived Social Impacts of Tourism and Quality-of-Life: A New Conceptual Model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Md Rami, A.A.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ahrari, S. Effects of Emotions and Ethics on Pro-Environmental Behavior of University Employees: A Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Programme on Mental Health: WHOQOL User Manual; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Britannica. Quality of Life. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/quality-of-life (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Bowling, A.; Stenner, P. Which Measure of Quality of Life Performs Best in Older Age? A Comparison of the OPQOL, CASP-19 and WHOQOL-OLD. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Trajectories of Influence across Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallinheimo, A.-S.; Evans, S.L. More Frequent Internet Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic Associates with Enhanced Quality of Life and Lower Depression Scores in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Healthcare 2021, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, P.; Iob, E.; Demakakos, P.; Steptoe, A. Immediate and Longer-Term Changes in the Mental Health and Well-Being of Older Adults in England During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beridze, G.; Ayala, A.; Ribeiro, O.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Forjaz, M.J.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A. Are Loneliness and Social Isolation Associated with Quality of Life in Older Adults? Insights from Northern and Southern Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorian, P.; Brijmohan, A. The Role of Quality of Life Indices in Patient-Centred Management of Arrhythmia. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Kang, S.-W. The Quality of Life, Psychological Health, and Occupational Calling of Korean Workers: Differences by the New Classes of Occupation Emerging Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Lima, M.D.; da Silva, T.P.R.; de Menezes, M.C.; Mendes, L.L.; Pessoa, M.C.; de Araújo, L.P.F.; Andrade, R.G.C.; D’Assunção, A.D.M.; Manzo, B.F.; dos Reis Corrêa, A.; et al. Environmental and Individual Factors Associated with Quality of Life of Adults Who Underwent Bariatric Surgery: A Cohort Study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, S.L.; Auchincloss, A.H.; Michael, Y.L. Impact of Policy and Built Environment Changes on Obesity-related Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Naturally Occurring Experiments. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M.; Wiggins, R.D.; Higgs, P.; Blane, D.B. A Measure of Quality of Life in Early Old Age: The Theory, Development and Properties of a Needs Satisfaction Model (CASP-19). Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, L.P.; Bastos, J.L.; d’Orsi, E. Reassessing the CASP-19 Adapted for Brazilian Portuguese: Insights from a Population-Based Study. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.L.; Tey, N.P. The Quality of Life of Older Adults in a Multiethnic Metropolitan: An Analysis of CASP-19. Sage Open 2021, 11, 215824402110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, S.S.; Sooryanarayana, R.; Ahmad, N.A.; Jamaluddin, R.; Abd Razak, M.A.; Tan, M.P.; Mohd Sidik, S.; Mohamad Zahir, S.; Sandanasamy, K.S.; Ibrahim, N. Prevalence of Dementia and Quality of Life of Caregivers of People Living with Dementia in Malaysia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Mutalip, M.H.; Abdul Rahim, F.A.; Mohamed Haris, H.; Yoep, N.; Mahmud, A.F.; Salleh, R.; Lodz, N.A.; Sooryanarayana, R.; Maw Pin, T.; Ahmad, N.A. Quality of Life and Its Associated Factors among Older Persons in Malaysia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, J.; Bartlam, B.; Bernard, M. The CASP-19 as a Measure of Quality of Life in Old Age: Evaluation of Its Use in a Retirement Community. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrat-Besson, C.; Ryser, V.-A.; Gonçalves, J. An Evaluation of the CASP-12 Scale Used in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) to Measure Quality of Life among People Aged 50+; FORS: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, K.; Ward, M.; Romero Ortuño, R.; Kenny, R.A. Syncope, Fear of Falling and Quality of Life Among Older Adults: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging (TILDA). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.; Hyde, M.; Wiggins, R.; Blane, D. Researching Quality of Life in Early Old Age: The Importance of the Sociological Dimension. Soc. Policy Adm. 2003, 37, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, N.; Păun, M. Autonomy and identity: The role of two developmental tasks on adolescent’s wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1309690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murod, M.; Taufiqurokhman, T.; Zaman, A.N.; Gunanto, D.; Mawar; Handayani, N. Empirical Analysis of the Influence of Perceived Behavioral Control, Environmental Concern and Attitude on pro-Environmental Behavior. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2023, 6, 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, L. A Survey on Public Acceptance of Automated Vehicles across COVID-19 Pandemic Periods in China. IATSS Res. 2023, 47, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. The psychology of participation and interest in smart energy systems: Comparing the value–belief–norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.-H.; Lung, S.-C.C. Impact of Physical and Social Living Environments on Pro-Environmental Intentions. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seol, J. Investigating Factors That Affect Individual Quality of Life by Participating in Pro-Environmental Behavior: Implications on Policies and Management. Master’s Thesis, KDI School of Public Policy and Management, Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Qin, X.; Zhou, Y. A Comparative Study of Relative Roles and Sequences of Cognitive and Affective Attitudes on Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 727–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, Z. Validating the Measurement Model: CFA. In A Handbook on SEM; Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015; pp. 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, A.M.; Knoch, D.; Berger, S. When and How Pro-Environmental Attitudes Turn into Behavior: The Role of Costs, Benefits, and Self-Control. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouahria, B. Predicting Citizens Municipal Solid Waste Recycling Intentions in Morocco: The Role of Community Engagement. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzalal, M.; Adnan, H.M. Attitude, Self-Control, and Prosocial Norm to Predict Intention to Use Social Media Responsibly: From Scale to Model Fit towards a Modified Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.P.; Cuskelly, M.; Pedersen, S.J.; Rayner, C.S. Attitudes and Self-Efficacy as Significant Predictors of Intention of Secondary School Teachers towards the Implementation of Inclusive Education in Ghana. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 82 | 45.1 |

| Female | 100 | 54.9 | |

| Age group | 18–25 | 153 | 84.1 |

| 26–35 | 19 | 10.4 | |

| 36–45 | 4 | 2.2 | |

| 46–55 | 6 | 3.3 | |

| 56 and above | 0 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | Malay | 111 | 61.0 |

| Chinese | 40 | 22.0 | |

| Indian | 19 | 10.4 | |

| Others | 12 | 6.6 | |

| Education level | Primary school | 0 | 0 |

| High school | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Certificate/Diploma | 62 | 34.1 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 113 | 62.1 | |

| Postgraduate Degree | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 170 | 93.4 |

| Married | 11 | 6.0 | |

| Others | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Occupation | Government | 0 | 0 |

| Private companies | 35 | 19.2 | |

| Self-employed | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Retired | 0 | 0 | |

| Not working/Unemployed | 140 | 76.9 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | |

| Monthly household income (MYR) | Less than MYR 2500 | 89 | 48.9 |

| MYR 2500–MYR 4849 | 35 | 19.2 | |

| MYR 4850–MYR 10,959 | 34 | 18.7 | |

| MYR 10,960 and above | 24 | 13.2 | |

| Correlations | SN | PBC | AT | INT | QC | QA | QS | QP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN | P.C | 1 | 0.566 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.309 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.282 ** |

| PBC | P.C | 0.566 ** | 1 | 0.415 ** | 0.447 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.268 ** |

| AT | P.C | 0.423 ** | 0.415 ** | 1 | 0.558 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.394 ** |

| INT | P.C | 0.430 ** | 0.447 ** | 0.558 ** | 1 | 0.322 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.434 ** |

| QC | P.C | 0.252 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.322 ** | 1 | 0.514 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.541 ** |

| QA | P.C | 0.309 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.514 ** | 1 | 0.644 ** | 0.587 ** |

| QS | P.C | 0.302 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.644 ** | 1 | 0.776 ** |

| QP | P.C | 0.282 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.776 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-environmental behavioural intention | Subjective norm | 0.629 | 1.589 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.581 | 1.721 | |

| QoL control | 0.614 | 1.628 | |

| QoL autonomy | 0.505 | 1.979 | |

| QoL self-realisation | 0.325 | 3.079 | |

| QoL pleasure | 0.366 | 2.732 | |

| Attitude | 0.680 | 1.470 |

| Variables | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective norm | 4 | 0.871 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 4 | 0.759 |

| QoL control | 4 | 0.601 |

| QoL autonomy | 5 | 0.744 |

| QoL self-realisation | 5 | 0.832 |

| QoL pleasure | 5 | 0.892 |

| Attitude | 3 | 0.796 |

| Pro-environmental behavioural intention | 4 | 0.850 |

| HTMT | AT | INT | PBC | QA | QC | QP | QS | SN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | ||||||||

| INT | 0.681 | |||||||

| PBC | 0.530 | 0.558 | ||||||

| QA | 0.433 | 0.505 | 0.492 | |||||

| QC | 0.454 | 0.469 | 0.526 | 0.780 | ||||

| QP | 0.467 | 0.498 | 0.327 | 0.705 | 0.751 | |||

| QS | 0.540 | 0.527 | 0.349 | 0.784 | 0.749 | 0.896 | ||

| SN | 0.506 | 0.501 | 0.689 | 0.363 | 0.341 | 0.322 | 0.356 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SN → AT | 0.264 | 0.270 | 0.087 | 3.045 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H2 | SN → INT | 0.132 | 0.135 | 0.084 | 1.576 | 0.115 | Not supported |

| H3 | PBC → AT | 0.282 | 0.291 | 0.104 | 2.722 | 0.007 | Supported |

| H4 | PBC → INT | 0.140 | 0.138 | 0.090 | 1.553 | 0.120 | Not supported |

| H5 | AT → INT | 0.331 | 0.331 | 0.073 | 4.545 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | QC → INT | 0.100 | 0.114 | 0.083 | 1.204 | 0.229 | Not supported |

| H7 | QA → INT | 0.074 | 0.080 | 0.074 | 0.995 | 0.320 | Not supported |

| H8 | QS → INT | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.108 | 0.466 | 0.641 | Not supported |

| H9 | QP → INT | 0.086 | 0.076 | 0.108 | 0.803 | 0.422 | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, S.M.; Mohd Hanafi, H.; Chong, C.Y.; Tan, B.C. Does Quality of Life Influence Pro-Environmental Intention? An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198953

Pang SM, Mohd Hanafi H, Chong CY, Tan BC. Does Quality of Life Influence Pro-Environmental Intention? An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198953

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Suk Min, Hasni Mohd Hanafi, Choy Yoke Chong, and Booi Chen Tan. 2025. "Does Quality of Life Influence Pro-Environmental Intention? An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198953

APA StylePang, S. M., Mohd Hanafi, H., Chong, C. Y., & Tan, B. C. (2025). Does Quality of Life Influence Pro-Environmental Intention? An Extension of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability, 17(19), 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198953