Abstract

As climate change intensifies, reducing agricultural carbon emissions has become crucial for achieving sustainable development goals. Digital finance, with its potential to transform traditional farming practices, may play a key role in this transition. This study examines the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity (ACE) based on comprehensive provincial data from China (2011–2022). Through rigorous econometric analysis, we find that digital finance significantly reduces ACE, with particularly strong effects in western regions compared to eastern and central areas. The results demonstrate that agricultural total factor productivity serves as an important channel through which digital finance lowers emissions. Furthermore, environmental regulation enhances digital finance’s emission reduction potential, while spatial analysis reveals positive spillover effects to neighboring regions. These findings remain robust across various model specifications and testing methods. The study provides valuable insights into how digital financial tools can contribute to low-carbon agricultural development, highlighting the importance of region-specific policies and inter-regional coordination for maximizing environmental benefits.

1. Introduction

Climate change has become a common challenge facing the world. Global warming, in particular, is largely driven by the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, which not only threaten the stability of ecosystems but also pose serious risks to human health and economic development. As one of the most important sources of greenhouse gases, the agricultural sector has become a focus of global environmental governance due to its dual characteristics of carbon emission and carbon sink. According to statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in 2022, about 29.7% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions came from agricultural activities [1]. Against the background of China’s continuous advancement of agricultural modernization, agricultural carbon emissions are expected to rise overall, while the urgency to cut emissions grows stronger [2]. To achieve low-carbon transformation in agriculture, it is urgent to manage high-carbon production behaviors, promote green technologies, and improve agricultural energy efficiency. However, these measures often face practical obstacles such as difficulty in obtaining funds and weak risk control [3]. In recent years, digital finance has provided new solutions for the green transformation of agriculture. Digital finance improves the availability and efficiency of financial services, guides financial resources to the low-carbon agricultural sector through tools such as green credit, agricultural insurance, and digital payments, and promotes the adoption of green technologies and the renewal of energy-saving equipment [4,5]. At the same time, digital platforms can provide agricultural entities with real-time data support and intelligent decision-making recommendations, improve their resource allocation efficiency, and reduce their carbon footprint [6]. Especially in remote areas and areas where traditional financial coverage is insufficient, the inclusive nature of digital finance has significantly improved the ability and willingness of small farmers to participate in green agriculture [7]. Based on this, in-depth research on the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity can provide new evidence for the low-carbon transformation of agriculture, which has important practical significance and policy value.

As an important indicator for measuring the impact of agriculture on the environment, agricultural carbon emissions have great significance in reducing emissions and thus continue to receive widespread attention from the academic community. Related research has gradually formed a relatively systematic theoretical framework. (1) Measurement of carbon emissions: There are three main measurement methods: the first is the IPCC method based on carbon emission coefficients, which is suitable for macro-emission estimation; the second is the life cycle analysis method (LCA), which evaluates emissions and storage throughout the entire agricultural activity process by setting system boundaries [8,9]; and the third is the input–output method, which uses input–output tables and energy factors to calculate agricultural energy consumption and carbon emissions [10]. However, agricultural carbon emissions come from diverse sources, and as a key sector for improving carbon emission efficiency, its research perspectives are also increasingly diverse. Scholars mainly focus on perspectives such as crop carbon emissions [11], animal husbandry carbon emissions [12], agricultural energy carbon emissions, and agricultural carbon footprint based on full life cycle accounting [13]. (2) Studies on the determinants of agricultural carbon emissions: Focusing on soil and water resources, Zhao et al. (2018) [14] applied the logarithmic mean Divisia index (LMDI) model to examine how the development of these resources influences agricultural carbon output. Similarly, Wang et al. (2022) [15] employed the water–land resource coupling coordination (WLCD) model to investigate the interplay between agricultural carbon emissions and the coordination of water and land resources. Their findings suggest that enhancing the synergy between soil and water systems can significantly mitigate carbon emissions in arid inland regions. From the perspective of agricultural technology innovation, Zheng et al. (2024) [16] and Li and Wang (2023) [17] showed that progress in agricultural technology leads to a notable decrease in energy-related carbon emissions per unit of output. In addition, agricultural industrial structure upgrading [18], natural disasters and investment intensity [19], agricultural production efficiency [20], and agricultural development policies [21] are also considered by scholars to be key factors affecting agricultural carbon emissions.

With the deepening implementation of the “dual carbon” strategy, the role of digital finance in agricultural carbon emission reduction has received increasing attention. Existing studies have conducted preliminary explorations of its impact mechanisms from multiple pathways and perspectives. Li et al. (2025) [22] found that digital finance can significantly reduce agricultural carbon emissions, primarily by stimulating farmers’ entrepreneurial vitality, optimizing rural industrial structure, and promoting agricultural product trade, but large-scale farmland operations have somewhat weakened these effects. Zhang and Li (2025) [23] pointed out that digital finance significantly suppresses carbon emission intensity by promoting green agricultural entrepreneurship and innovation, with its effects being more pronounced in regions with strong smart city policy support and large populations. Tan et al. (2024) [24] showed that digital finance drives carbon emission reduction by improving agricultural mechanization, with its effects being more pronounced in southern China and non-grain-producing provinces. Liu et al. (2023) [25] emphasized its ability to reduce carbon emissions by improving the educational level of the workforce and promoting green and low-carbon agricultural development. Chang (2022) [4] believed that farmer entrepreneurship and technological innovation are the primary emission reduction pathways of digital finance, with urbanization levels having a positive moderating effect. Sun et al. (2022) [5] used the Super SBM model and found that digital finance significantly improves agricultural carbon emissions and exhibits spatial spillover effects. Liu and Ren (2023) [26] argued, based on a food system perspective, that the integration of digital finance facilitates the harmonious growth of production and decarbonization in agriculture in major grain-producing regions. Liao and Zhou (2023) [6] found that digital finance exerts emission reduction effects through green agricultural innovation, with more pronounced effects in high-income and high-education regions. Hong et al. (2024) [27] proposed that digital finance exerts a negative impact across different quantiles through the capital deepening mechanism and exhibits a spatial enhancement effect. Li et al. (2024) [28] proposed an inverted U-shaped relationship between digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions, emphasizing that excessive reliance on cooperatives may weaken its emission reduction effects, while human capital can enhance its positive effects. Zheng et al. (2025) [29] used a machine learning causal inference model, suggested that digital finance can reduce carbon intensity through technological innovation and urban–rural income balance, but is significantly constrained by resource endowments and regional structure. Bao et al. (2024) [30] used a spatial econometric perspective and confirmed that digital finance achieves carbon reduction through spatial spillovers and cross-regional coordination mechanisms. Li and Jiang (2024) [31] confirmed that rural inclusive finance directly accelerates carbon reduction in agricultural practices through technological progress, factor allocation optimization, and pollution suppression mechanisms.

In summary, existing research primarily concentrates on two dimensions: (1) methodological approaches to quantifying agricultural carbon emissions and (2) identification of their key determinants. Emerging research has begun examining digital finance’s mediated impacts through four critical pathways: farmer entrepreneurial activities, rural industrial restructuring, eco-innovation in agriculture, and workforce educational attainment. Few studies have explored the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity. Based on this, we select China’s provincial panel data from 2011 to 2022 for empirical analysis. The marginal innovations of this paper are as follows: (1) From the perspective of digital finance, it explores its specific impact on agricultural carbon emission intensity. (2) Based on the new perspective of total factor productivity, it explores whether agricultural total factor productivity plays a significant mediating role. (3) Based on the perspective of environmental regulation, it analyzes whether it can effectively regulate the role of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity. This study is organized into five main sections. Section 1 outlines the research context, focusing on digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions, and highlights the existing research gap along with the significance of the investigation. Section 2 presents a theoretical framework, analyzing the relationship between digital finance and the intensity of agricultural carbon emissions, and introduces three hypotheses to be tested. Section 3 details the research methodology, including model construction, variable definition, and data acquisition. Section 4 discusses the empirical findings derived from the model introduced earlier. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the conclusions and explores the broader implications of the study.

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. The Impact of Digital Finance on Agricultural Carbon Emission Intensity

Agriculture has its long production cycles, significant environmental impacts, slow investment returns, and low returns. It needs to be supported by fiscal subsidies and financial policy support [32]. However, traditional financial institutions are highly profit-driven and inherently exclude vulnerable groups such as farmers. Prevalent financing constraints in rural areas have become a significant constraint on the green development of agriculture [33]. Through advanced technologies including big data analytics and AI algorithms, digital finance enables more accurate credit risk assessment for agricultural borrowers, expands financial service coverage, and alleviates financing difficulties and high costs [34]. This approach strengthens farmers’ capacity to adopt environmentally friendly technologies—such as efficient irrigation systems, organic fertilizers, and sustainable agricultural machinery—leading to a decrease in carbon emissions per unit of agricultural output. Moreover, digital finance facilitates the expansion and specialization of farming practices by offering tailored, intelligent financial solutions. It supports the strategic allocation of agricultural resources [35], and it encourages the consolidation of production inputs toward more efficient and eco-conscious farming models, ultimately contributing to lower carbon emissions. Furthermore, digital finance can incorporate functions such as carbon footprint tracking and green ratings, offering incentives such as preferential interest rates and increased financing to agricultural operators with low carbon emissions. This will create a positive feedback mechanism of “green production–financial support” and boost farmers’ motivation to implement environmentally friendly practices [36]. Based on this, Hypothesis 1 is proposed.

H1:

Digital finance can effectively curb agricultural carbon emission intensity.

2.2. The Mechanism of Digital Finance’s Impact on Agricultural Carbon Emission Intensity

In the mechanism of digital finance’s impact on agricultural carbon emission intensity, agricultural total factor productivity plays a crucial transmission role. First, by developing tools such as mobile payments, digital credit, and agricultural insurance, digital finance has overcome the exclusion of vulnerable rural groups from traditional finance, effectively alleviating the difficulties and high costs of agricultural financing, and significantly improving the availability and coverage of financial services [37]. Farmers can more easily invest in energy-efficient agricultural technologies and equipment, such as efficient water-saving irrigation, intelligent agricultural machinery, and green agricultural inputs. This optimizes resource allocation, improves production methods, and promotes increases in agricultural total factor productivity. Second, increases in agricultural total factor productivity mean higher output per unit of resource input, enabling agricultural production to improve output efficiency while reducing resource waste and energy consumption [38], thereby effectively reducing carbon emission intensity. Therefore, agricultural total factor productivity (TFP) establishes a transmission path between digital finance and carbon emission intensity: “resource optimization, efficiency improvement, and carbon emission reduction,” becoming a crucial mechanism for digital finance to achieve its green emission reduction effects. Based on this, Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

H2:

Digital finance can curb agricultural carbon emission intensity by improving agricultural TFP.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Environmental Regulation

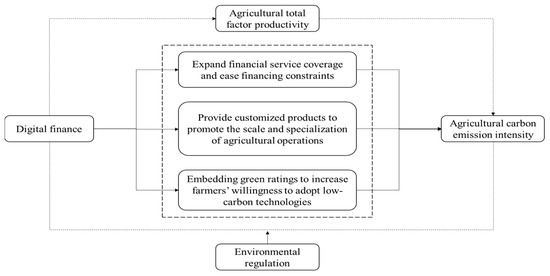

Government-led environmental regulation serves as a crucial instrument for promoting sustainable development and significantly influences how digital finance impacts the intensity of agricultural carbon emissions. According to the Porter Hypothesis, appropriate environmental regulation can incentivize agricultural entities to adopt more efficient and low-carbon production technologies, thereby achieving the goal of “using regulation to promote green development” [39]. Within the context of environmental regulation, the development of digital finance not only broadens financing channels and provides information platforms and risk management tools, but it also fosters a positive interaction with environmental regulation. On the one hand, through setting emission standards, imposing environmental taxes and fees, and strengthening law enforcement and inspections, environmental regulation increases the cost of agricultural pollution and strengthens agricultural entities’ demand for green technologies and low-carbon transformation [40]. Through green credit, agricultural insurance, and digital payments, digital finance provides the necessary financial and service support. On the other hand, environmental regulations strengthen green awareness among agricultural entities and accelerate the adoption of green technologies. Digital finance’s advantages in information transparency and targeted credit allocation improve the efficiency of environmental regulation enforcement and policy effectiveness, strengthening green incentives. Based on this, Hypothesis 3 is proposed. See Figure 1 for details.

Figure 1.

Effect mechanism of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity.

H3:

Environmental regulations enhance the inhibitory effect of digital finance on agricultural carbon emissions.

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Description

3.1.1. Agricultural Carbon Emission Intensity (ACE)

In this research, we calculated provincial agricultural carbon emissions based on agricultural production objects, referring to the studies of Huang et al. [41]. Agricultural carbon emissions were quantified across six key sources: diesel combustion, synthetic fertilizer application, pesticide use, agricultural plastic films, irrigation systems, and soil tillage operations. The carbon emission coefficient is shown in Table 1. Based on this, we used the following formula for calculation:

Table 1.

Carbon sources and coefficients of agricultural carbon emissions.

In Model (1), C indicates aggregate agricultural carbon emissions; Ck represents the agricultural carbon emissions generated by the kth agricultural carbon source; Tk represents the total data of the kth carbon source; δk represents the emission conversion coefficient corresponding to the kth carbon source. In this study, agricultural carbon emission intensity is defined as the ratio of agricultural carbon emissions to agricultural output, based on the following formula:

In Model (2), ACEit represents the agricultural carbon emission intensity in the t-th year of the i-th province; Cit represents the total agricultural carbon emissions in the t-th year of the i-th province; AGDPit represents the total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery in the t-th year of the i-th province. In order to make the agricultural carbon emission intensity comparable, in this research, we used 2011 as the base period, deflated the total output value of AGDP, and eliminated the interference of factors such as price.

3.1.2. Explanation of Other Variables

(1) Digital Finance Index (DFI). Digital finance refers to digital technology and Internet platforms which provide inclusive financial services to people who cannot access traditional financial services. The data is measured using 33 indicators across three dimensions: breadth of coverage, depth of use, and degree of digitization. The digital finance data used in this research is from Peking University Digital Finance Research Center [23].

(2) The following control variables are selected in this research. (a) Fiscal Support for Agriculture (FSA). Government fiscal subsidies and support for agriculture can increase farmers’ use of fertilizers, pesticides, and other agricultural materials, thereby increasing agricultural carbon emission intensity [42]. (b) Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, which denotes economic development level. The higher the level of economic development, the higher the agricultural technology and the green agricultural development level. In this research, we used the logarithm of GDP per capita [43]. (c) Industrial Structure (IS). It reflects the dynamic change process of industrial structure from low to high. The upgrading of industrial structure means a decrease in the proportion of agricultural development in the industry. Therefore, the agricultural carbon emission intensity can be decreased. This research uses the proportion of primary industry value added to GDP to represent industrial structure [44]. (d) Urbanization Rate (UR). The development of urbanization has resulted in a greater number of older and female workers in the agricultural labor force. In order to ensure that the output is not affected, production factors such as fertilizers and pesticides are widely used in agricultural production activities, which generates a large amount of carbon emissions. Increasing the urbanization rate will also change the living concept and consumption mode of rural labor, optimize the energy consumption structure, and reduce agricultural carbon emissions [45]. Therefore, the impact of urbanization rate on agricultural carbon emission efficiency is uncertain, and it is mainly characterized by the ratio of urban population to regional total population. (e) Crop Disaster Level (CDL). Disasters destroy the farmland ecosystem, reduce photosynthetic efficiency, and force farmers to take emergency measures such as increasing nitrogen fertilizer and burning stubble, which directly increase nitrous oxide and methane emissions. Post-disaster reconstruction requires increased energy input such as irrigation and agricultural machinery operations, further pushing up the carbon footprint. In addition, the damage to cultivated land may lead to a surge in carbon emissions in land reclamation, which is expressed as the ratio of crop disaster area to total crop planting area [46]. (f) Rural Electricity Consumption (REC). The improvement in rural electricity consumption levels means that agricultural production becomes mechanized, intelligent, and electricity-driven, reducing dependence on fossil energy and thereby reducing carbon emissions. REC is expressed in per capita electricity consumption of the rural population [47].

(3) Mechanism variables. Agricultural total factor productivity (ATFP). The improvement in total factor productivity is an effective measure of scientific and technological progress. The higher the agricultural total factor productivity, the higher the scientific and technological content of agricultural economic development and the stronger its sustainability. Here, we draw on the research of Fu and Zhang [48] and Baležentis [49] and use the stochastic frontier analysis model (SFA) proposed by Battese & Coelli [50] on the basis of the C-D production function to calculate the agricultural total factor productivity. We employ total agricultural output value as the response variable, with explanatory variables comprising primary sector employment (labor input), total crop-sown area (land input), aggregate agricultural machinery power (capital input), and fertilizer application rates (material input). The calculation formula is as follows:

where i is the i-th production unit, t is the time, yi,t is the actual output of the i-th production unit in period t, Xi,t represents the factor input vector of the i-th unit in period t, f(Xi,t,β,t) is the production function, and β is the parameter to be estimated. vi,t is a random error term that follows the normal distribution . ui,t is a non-negative management error term that follows the non-negative truncated normal distribution .

η is the parameter to be estimated, which represents the impact of time factors on the technical inefficiency term uit. η > 0, η = 0, and η < 0, respectively, indicate that uit increases, remains unchanged, and decreases with time.

Technical efficiency (TE) is calculated as actual output expectation divided by frontier output expectation, that is,

In the formula, when uit = 0, TEit = 1, which means that the technology is efficient; when uit > 0, TEit < 1, which means that it is inefficient.

According to the expression of uit in model (4), the change in technical efficiency can be further expressed as

Taking the logarithm of both sides of Equation (3) and the first-order partial derivative with respect to t, we can obtain the following:

In the formula, the first term on the right side of the equation represents the change in the frontier caused by the change in factor input under a given technological level; the second term represents the change in frontier output under the condition of constant factor input, that is, technological progress (TP); the third term represents the change in technical efficiency (TECH); x represents the input factor. Combining the above, we can obtain the following:

It can be seen that ATFP growth can be expressed as the sum of technological progress (TP) and technological efficiency change (TECH).

(4) Moderating effect. Environmental regulation (ER): the proportion of pollution control project investment in each region to regional GDP. Environmental regulation reflects the degree of attention paid by local governments to the environment. The higher the investment, the better the environmental governance effect, and the more conducive it is to reducing the local agricultural carbon emission intensity. Therefore, in this research, we expect its coefficient sign to be negative [51,52].

3.2. Model Construction

3.2.1. Panel Model Setting

To examine the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity, this research sets the following model:

In Model (9), ACE means the agricultural carbon emission intensity of each region, DFI represents the Digital Finance Index; X represents the control variables; δi and τt represent the regional and time fixed effects, respectively; ε represents the random error term.

3.2.2. Mediation-Effect Model

To verify the internal mechanism of digital finance affecting agricultural carbon emission intensity, agricultural total factor productivity (ATFP) is introduced as a mediating variable. In this study, we employ the research method of Li and Liu [53] to construct a mediation-effect model.

In Models (10) and (11), ATFP represents agricultural total factor productivity, α1 measures the total effect of DFI (Digital Finance Index) on ACE (agricultural carbon emission intensity), π1 reflects the direct effect, w1π2 measures the mediating effect, w1π2/(w1π2 + α1) represents the proportion of the mediating effect, and the other variables are in line with Model (9).

3.2.3. Moderating-Effect Model

The moderating-effect framework, initially introduced by Aiken et al. [54], has since become a widely utilized analytical approach in social science research. Following the methodology of Wu et al. [19], this study incorporates an interaction term between environmental regulation (ER) and digital finance (DFI) to empirically examine ER’s moderating role. The moderating model is set as follows:

In Model (12), ACEit refers to agricultural carbon emission intensity and ERit stands for environmental regulation. DFIit * ERit represents the moderating effect of environmental regulation and digital finance.

3.2.4. Spatial Econometric Model

To verify whether digital finance has a negative spatial spillover effect on agricultural carbon emission intensity, a spatial econometric model is also set as follows:

In model (13), γ1 is the spatial autoregression coefficient, W is the weight coefficient, and γ0 is the constant term. In the empirical regression part, we will demonstrate related results of the spatial econometric regression.

3.3. Data Collection

In this research, we selected provincial data for China from 2011 to 2022 for empirical analysis. The Digital Finance Index data are from the Digital Research Center of Peking University. Agricultural carbon emission data comes from the China Rural Statistical Yearbook and the statistical yearbooks of each province.

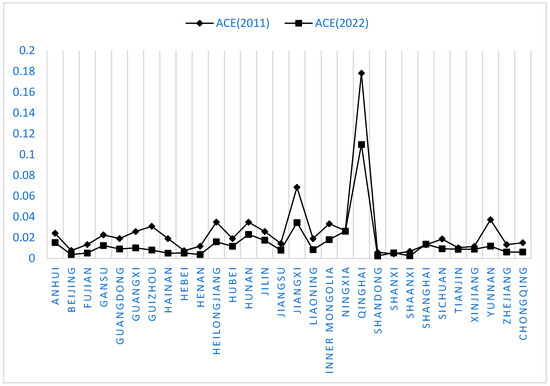

Figure 2 illustrates the agricultural carbon emission intensity levels in 2011 and 2022. According to the ACE results in 2011, Heilongjiang, Qinghai, Yunnan, Jiangxi, and Hunan provinces have the five highest agricultural carbon emission intensities, with Qinghai province having the highest value at 0.1782. Based on the ACE results in 2022, Anhui, Hunan, Jiangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Qinghai provinces have the six highest agricultural carbon emission intensities, with Qinghai province still having the highest value at 0.1096. Shanghai and Shanxi provinces show a small margin of change between 2011 and 2022; Qinghai province shows the highest at 0.1096; overall, most provinces demonstrated progressively diminishing agricultural carbon intensities during the study period. This shows that the rural agricultural environment in China has improved to a certain extent.

Figure 2.

Levels of agricultural carbon emission intensity in each province, 2011–2022.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 2. The dataset has 360 observations. Agricultural carbon emission intensity (ACE) averages 0.0188 (SD = 0.0239), indicating significant variability in environmental impact. The Digital Finance Index (DFI) shows a wide range (18.330–486.013), reflecting uneven regional adoption. Agricultural total factor productivity (ATFP) averages 1.5994 (SD = 0.7687), suggesting moderate efficiency with notable disparities. Environmental regulation (ER) varies drastically (0.0756–110.338), highlighting divergent policy rigor. Fiscal support for agriculture (SFA) averages 0.2581 but spans 0.0705–2.0753, revealing unequal government investment. Economic development (GDP) is relatively stable (SD = 0.4530), while industrial structure (IS) and urbanization (UR) exhibit moderate variation.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4.2. Regression Results

Based on Hausman test results, the fixed effect regression is selected for analysis. The regression results are reported in Table 3 from column (1) to (7); that is, the control variables are added one by one. The results show that the Digital Finance Index (DFI) consistently reduces agricultural carbon emission intensity (ACE) across all models, with coefficients ranging from −0.0146 to −0.0132 (significant at the 1% level). For example, the regression coefficient of digital finance in column (7) of Table 3 is −0.0144, which is significantly negative. Its economic meaning is that every 1 unit increase in the level of digital finance development will significantly reduce agricultural carbon emission intensity by about 1.44%. This suggests that digital finance plays a vital role in reducing emissions, which is consistent with the findings of Zheng et al. (2025) [29], which may be achieved by enabling precision agriculture, improving access to green technologies, or optimizing resource use.

Table 3.

Regression results.

The regression results of the control variables are shown in column (7) of Table 3. Fiscal support for agriculture (SFA) is positively correlated with the agricultural carbon emission intensity. This shows that agricultural subsidies promote large-scale operations to a certain extent. Large-scale production is often accompanied by the use of more fertilizers, pesticides, and fossil energy, which leads to an increase in the agricultural carbon emission intensity per unit output. Economic development (lnGDP) is negatively correlated with agricultural carbon emission intensity, indicating that economic development often makes the R&D funds accumulated by economic growth flow more to low-carbon agricultural technology, reducing the agricultural carbon emission intensity per unit output. Moreover, industrial structure (IS) is negatively correlated with agricultural carbon emission intensity, indicating that industrial structure upgrading can significantly reduce agricultural carbon emission intensity through technology diffusion, policy constraints, and energy structure optimization. Urbanization rate (UR) is found to be positively correlated with agricultural carbon emission intensity, indicating that urbanization promotes intensive agricultural production, expands the use of fertilizers and pesticides, and increases energy consumption in processing and transportation, aggravating agricultural carbon emission intensity. In addition, crop disaster level (CDL) is positively correlated with agricultural carbon emission intensity, indicating that post-disaster recovery depends on the increase in fertilizers and pesticides, rising irrigation energy consumption and land degradation, which aggravates short-term emission pressure. Lastly, the rural electricity consumption level (REC) is negatively correlated with agricultural carbon emission intensity, but the effect is not significant. This may be due to the low proportion of clean energy, the insufficient penetration rate of electrified equipment, and high electricity costs inhibiting technology substitution.

4.3. Robustness Test and Endogeneity Test

In this research, we mainly used four methods to conduct robustness tests (see Table 4). The first method is to replace the dependent variable, agricultural carbon emission intensity, with agricultural carbon emissions; column (1) is the regression result after replacing the dependent variable. The second method is to replace the fixed effect regression model with the Tobit model to further test the relationship between digital finance and agricultural carbon emission intensity; column (2) shows the regression result of the Tobit model. The third method is to eliminate special samples by eliminating the data of the four municipalities and re-estimating the sample; column (3) is the regression result after further eliminating special samples. The fourth method is to perform 1% tail shrinkage on all variables to identify outliers; column (4) shows the regression result after tail shrinkage.

Table 4.

Robustness and endogeneity tests.

A potential causal link may exist between digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions. However, the model may face endogeneity issues due to omitted variables. To address this concern, in this study, we employed the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. Specifically, the first-order lag of the Digital Finance Index (DFI) is used as an instrumental variable to test for endogeneity. Additionally, the Internet penetration rate serves as another instrumental variable, given its significant influence on regional digital finance development and its lack of indirect impact on agricultural carbon emission intensity via digital inclusion, thus satisfying both relevance and exogeneity criteria. The results presented in columns (5) and (6) confirm the validity of the instrumental variable approach. Overall, the consistently negative and statistically significant regression coefficients for digital finance reinforce the robustness and credibility of the findings discussed in Section 4.2.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

To investigate regional variations, we categorized the full dataset into three geographic divisions—eastern, central, and western regions—and performed separate regression analyses for each (see Table 5). The regression analysis reveals clear regional disparities in how digital finance affects agricultural carbon emission intensity. While the influence in the eastern and central regions is negative, it lacks statistical significance. In contrast, the western region exhibits a significantly negative relationship. Moreover, the magnitude of the regression coefficient indicates that digital finance has a considerably stronger impact on reducing agricultural carbon emissions in the western region compared to the eastern and central areas. This result stems from relatively extensive agricultural development in western China, where traditional, high-carbon production methods predominate. The introduction of digital finance facilitates green technology substitution and resource optimization, offering greater potential for emission reductions and a more pronounced marginal impact. Furthermore, traditional financial coverage in western China is insufficient. As an alternative form of financial supply, digital finance can more effectively alleviate financing constraints for green agriculture and play a more significant role. Furthermore, the country’s recent increased support for ecological protection and digital infrastructure development in western China has also created a favorable environment for digital finance to empower green agriculture. In contrast, eastern and parts of central China boast a higher level of agricultural modernization and a higher penetration rate of green technologies, resulting in a limited marginal emission reduction effect from digital finance. Furthermore, agriculture plays a relatively low role in the regional economy, and digital finance focuses more on consumer finance and urban businesses. Agricultural services are under-penetrated, making it difficult to significantly impact agricultural carbon emissions.

Table 5.

Regional heterogeneity test.

4.5. Mediating Effect and Moderating Effect

Based on previous studies, it can be concluded that digital finance can reduce agricultural carbon emission intensity by improving agricultural total factor productivity, and environmental regulation can effectively regulate the inhibitory effect of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity. For this reason, in this research, we introduce agricultural total factor productivity (ATFP) as a mediating variable and environmental regulation (ER) as the moderating variable to further reveal the internal mechanism of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Mediating and moderating effects.

To begin with, the regression coefficient for agricultural total factor productivity in column (1) is 0.418, which meets the 10% significance threshold, suggesting that digital finance has a positive effect on enhancing agricultural productivity. Specifically, a 1-unit rise in the Digital Finance Index corresponds to an approximate 0.418-unit increase in total factor productivity. In column (2), the coefficients for digital finance and agricultural total factor productivity are −0.0139 and −0.00104, respectively (both statistically significant), indicating that digital finance contributes to lowering agricultural carbon emission intensity by boosting productivity. Furthermore, column (3) shows that the coefficients for digital finance and its interaction with environmental regulation are significantly negative, implying that regulatory measures strengthen the suppressive impact of digital finance on carbon emissions in agriculture. That is, environmental regulation forms policy synergy with digital tools through mandatory emission reduction targets, significantly enhancing the inhibitory effect of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission reduction. For example, environmental taxes increase the cost of high energy consumption, and digital finance realizes emission reduction through carbon inclusiveness and carbon sink trading, forming a “punishment–incentive” closed loop.

4.6. Spatial Effect Test

Digital finance and agricultural carbon emission intensity can have a significant spatial correlation, so the construction of a spatial econometric model can more accurately measure the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emissions. Since the spatial Durbin model (SDM) considers both spatial lag and spatial error autocorrelation effects, in this research, we preliminarily tested that the SDM is more appropriate. In addition, in order to further determine the applicability of the SDM, we used the economic distance weight matrix to perform a Wald test and an LR test on SAR, SEM, and SDM. The Wald test and LR test index values are 14.930, 13.810 and 67.490, 1319.69, respectively, at the 1% significance level. The results confirm that the spatial Durbin model maintains its distinct specification without degenerating into either a spatial lag or spatial error model. Furthermore, the Hausman test results justify the adoption of a two-way fixed-effects spatial Durbin model specification to rigorously examine the relationship between digital finance development and agricultural carbon emission intensity.

To improve the estimation performance and robustness of spatial econometric models, we conducted empirical analysis using an economic geography weight matrix (W1) and an economic distance weight matrix (W2). W1, based on regional geographic proximity, reflects the impact of geographic proximity on policy diffusion and economic linkages; W2, incorporating indicators such as per capita GDP, emphasizes the spatial spillover effects of similar economic development levels. These two weight matrices reveal spatial linkage mechanisms between regions from different perspectives, facilitating a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emissions (see Table 7). The regression results based on the economic geography weight matrix reveal that the primary effect coefficient of digital finance is −0.0189, which is statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that digital finance contributes to lowering agricultural carbon emission intensity. Additionally, the spatial lag coefficient of digital finance stands at −0.0500, which is also significant at the 1% level, indicating that digital finance in one region exerts a suppressive influence on carbon emissions in adjacent areas. Analyzing the spatial decomposition of effects, the direct impact coefficient is −0.0170, implying that a 1% rise in digital finance leads to a 0.017% reduction in local agricultural carbon emissions. Meanwhile, the indirect effect is −0.0193, meaning that a 1% increase in digital finance results in a 0.0193% decline in emissions in neighboring regions—demonstrating that the spillover effect of digital finance is more pronounced than its local impact.

Table 7.

Economic geography weight matrix regression results.

Secondly, from the regression results of the economic distance weight matrix (see Table 8), it can be seen that the main effect regression coefficient of digital finance is −0.0181, The regression results demonstrate statistically significant negative effects at the 1% level: a spatial lag coefficient of −0.0286 for digital finance, along with direct (−0.0164) and indirect (−0.0141) impact coefficients on agricultural carbon emission intensity. These findings confirm that digital finance not only effectively reduces local agricultural carbon emissions but also generates positive spillover effects that lower emission intensity in neighboring regions, thereby validating the robustness of the model outcomes.

Table 8.

Economic distance weight matrix regression results.

5. Discussion and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Discussion on Research Results

Based on the above empirical analysis, the research results of this paper expound on several key issues. First, compared with the strong profit-seeking nature of traditional financial institutions, digital finance, relying on digital technology, effectively alleviates the problems of financing difficulties and high financing costs, thereby increasing farmers’ investment in green technologies and reducing the carbon emission intensity per unit output, confirming hypothesis H1. This result is consistent with the research results of Li et al. (2025) [22]. Second, it is confirmed that the improvement of agricultural total factor productivity can effectively suppress agricultural carbon emission intensity. This result is basically consistent with the ideas of Tong et al. (2024) [38], but it fails to analyze its mediating effect from the perspective of digital finance. This paper empirically analyzes the mediating effect of agricultural total factor productivity on agricultural carbon emission intensity from the perspective of digital finance, that is, confirming hypothesis H2. Then, previous studies have focused on the impact of environmental regulation on agricultural carbon emission intensity. This view is the same as Xia et al. (2024) [55]. Based on previous research, this paper focuses on the moderating effect of environmental regulation on the relationship between digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions, that is, confirming hypothesis H3. Based on the above discussion, this study broadens the research perspective of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity from two new perspectives: agricultural total factor productivity and environmental regulation.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This paper has the following limitations. First, although the impact between digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions is analyzed, because of data shortage, in this paper, we only employed provincial data. More local differences might be ignored. Second, we further analyzed the spatial effects of digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions but failed to analyze the spatial transmission mechanism of the two. Finally, this paper is based on China’s actual data for analysis, and its practicality for other countries is limited. However, this research provides a new perspective for reducing agricultural carbon emissions and helping various regions promote sustainable development according to their actual conditions.

Future research directions: Based on the above-mentioned deficiencies, subsequent research can be expanded in two aspects: first, combining county data to deeply explore the spatial transmission mechanism of digital finance on agricultural carbon emissions; second, conducting comparative studies with the help of cross-national data to further identify the general laws and situational differences between digital finance and agricultural carbon emissions, and provide policy references for different countries in promoting the green and low-carbon transformation of agriculture.

5.3. Policy Suggestions

In order to further promote green development and achieve the long-term goal of sustainable development. The following policy recommendations are proposed:

Firstly, to better leverage the emission reduction role of digital finance, the government should accelerate the development of digital financial infrastructure in rural areas, particularly in western and remote areas, and increase the coverage and accessibility of financial services such as mobile payments, internet-based lending, and agricultural insurance. Furthermore, financial resources should be directed toward agricultural projects related to energy conservation and emission reduction, through green credit interest subsidies and special fund support. Farmers should be encouraged to leverage digital financial tools to transform their production methods, improve resource utilization efficiency, and achieve the goal of green and low-carbon agricultural development.

Secondly, improving agricultural total factor productivity is a key path to reducing carbon emissions. The government should use green credit interest subsidies and special funds for digital inclusive finance to direct funding toward agricultural technology applications with green attributes, such as precision fertilization, drone-based crop protection, and smart greenhouses. Local governments can also establish “digital finance + green agricultural technology” demonstration bases. Through financial support and platform development, they can improve the efficiency of agricultural technology promotion, encourage farmers to transform traditional production methods, and fundamentally improve resource utilization efficiency and carbon efficiency per unit of output.

Thirdly, environmental regulation can effectively enhance the emission reduction effects of digital finance. We should accelerate the development of agricultural carbon emission accounting standards and statistical systems, as well as promote the establishment of a farmland carbon emission monitoring platform based on big data and remote sensing technology. Furthermore, we should promote the integration of environmental information with financial systems, establish an agricultural carbon emission credit evaluation model, and use it as a key basis for green loan approvals. Lending institutions should be encouraged to offer preferential interest rates or preferential credit to low-carbon farmers, thereby achieving differentiated financial incentives for green agriculture. Finally, we should promote cross-regional digital financial collaboration and promote the systematic development of agricultural carbon emission reduction. We should strengthen cross-regional digital financial collaboration and promote the establishment of a green finance alliance to enable the sharing of data, technology, and financial instruments for carbon emission reduction projects, thereby enhancing the systematic and coordinated development of agricultural green finance.

6. Conclusions

Based on panel data of Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2022, in this study, we empirically tested the mechanism by which digital finance impacts agricultural carbon emission intensity through two-way fixed-effect, mediation-effect, moderating-effect, and spatial econometric models, and drew the following conclusions:

First, the empirical results of this study demonstrate that digital financial development exerts a statistically significant negative effect on agricultural carbon emission intensity. The regional heterogeneity analysis reveals significant spatial variation in digital finance’s impact, with statistically insignificant emission reduction effects observed in eastern and central regions, contrasted by significant inhibitory effects in western regions; at the same time, after changing the explained variables, explanatory variables, and models and following other robustness tests, the above conclusions still hold. Second, agricultural total factor productivity has a significant mediating effect on the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity, which is manifested in the fact that digital finance can reduce agricultural carbon emission intensity by improving agricultural total factor productivity. Third, environmental regulation has a significant moderating effect on the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity, which is manifested in the fact that the enhancement of environmental regulation can effectively improve the inhibitory effect of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity. Fourth, the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emission intensity has a positive spatial spillover effect. In addition, the impact of digital finance development on agricultural carbon emission intensity in neighboring regions is greater than that on agricultural carbon emission intensity in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F. and Y.L.; methodology, S.F.; software, S.F.; validation, Y.L., H.Y. and R.Y.; formal analysis, S.F.; investigation, S.F.; resources, Y.L. and R.Y.; data curation, S.F. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., R.Y. and H.Y.; visualization, S.F.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received fundings from Sichuan Key Laboratory for Innovation and Decision Science in Strategic Vanadium and Titanium Resources (FTZDS-ZD-2403), Panzhihua Municipal Deci-sion-Making Advisory Committee (202314); Research Center for the Economic Development of Ethnic Minorities in Sichuan Mountainous Areas (SDJJ202104); Sichuan Provincial Social Science Foundation (SC24E031).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data can be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2024. Available online: http://www.fao.org (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Li, S.; Xing, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, F. Transportation and the environment in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Can financial agglomeration curb carbon emissions reduction from agricultural sector in China? Analyzing the role of industrial structure and digital finance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. The role of digital finance in reducing agricultural carbon emissions: Evidence from China’s provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 87730–87745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, C.; Yuan, S.; Yang, L.; He, S.; Li, W. Exploring the impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural carbon emission performance in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhou, X. Can Digital Finance Contribute to Agricultural Carbon Reduction? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataza, R.R.; Doole, G.J.; Kragt, M.E.; Hailu, A. Information acquisition, learning and the adoption of conservation agriculture in Malawi: A discrete-time duration analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turconi, R.; Tonini, D.; Nielsen, C.F.; Simonsen, C.G.; Astrup, T. Environmental impacts of future low-carbon electricity systems: Detailed life cycle assessment of a Danish case study. Appl. Energy 2014, 132, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, G. Carbon footprint analysis for mechanization of maize production based on life cycle assessment: A case study in Jilin Province, China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15772–15784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Liu, J.; Niu, K.; Feng, Y. Comparative Analysis of Trade’s Impact on Agricultural Carbon Emissions in China and the United States. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Pan, X. Efficiency and Driving Factors of Agricultural Carbon Emissions: A Study in Chinese State Farms. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, X.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y. Assessing carbon emissions from animal husbandry in China: Trends, regional variations and mitigation strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Sun, T. Accounting for greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural system of China based on the life cycle assessment method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, Y.; Tian, M.; Ding, M.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chuai, X.; Xiao, L.; Yao, L. Impacts of water and land resources exploitation on agricultural carbon emissions: The water-land-energy-carbon nexus. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, R.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lu, R.; Fang, C. Quantifying the spatial–temporal patterns and influencing factors of agricultural carbon emissions based on the coupling effect of water–land resources in arid inland regions. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 908987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Tan, H.; Liao, W. Spatiotemporal evolution of factors affecting agricultural carbon emissions: Empirical evidence from 31 Chinese provinces. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 10909–10943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z. The effects of agricultural technology progress on agricultural carbon emission and carbon sink in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Chang, M. How does agricultural industrial structure upgrading affect agricultural carbon emissions? Threshold effects analysis for China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 52943–52957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, H.; He, Y.; Chen, W. Measurement, spatial spillover and influencing factors of agricultural carbon emissions efficiency in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Huo, C. The impact of agricultural production efficiency on agricultural carbon emissions in China. Energies 2022, 15, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakwa, P.A.; Acheampong, V.; Aboagye, S. Does agricultural development affect environmental quality? The case of carbon dioxide emission in Ghana. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, W.; Yu, X.; He, B. The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Agricultural Carbon Emissions: Evidence from China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W. The impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural carbon emissions at the city level in China: The role of rural entrepreneurship and agricultural innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 505, 145469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Tian, N.; Li, X.; Chen, H. Can digital financial inclusion converge the regional agricultural carbon emissions intensity gap? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Peng, B. The Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Green and Low-Carbon Agricultural Development. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ren, Y. Can digital inclusive finance ensure food security while achieving low-carbon transformation in agricultural development? Evidence from Chia. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Sun, L.; Zhao, L. Exploring the Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Agricultural Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the Mediation Effect of Capital Deepening. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, X.; You, J. Transitioning to low-carbon agriculture: The non-linear role of digital inclusive finance in China’s agricultural carbon emissions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, X. How the impact and mechanisms of digital financial inclusion on agricultural carbon emission intensity: New evidence from a double machine learning model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1549623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.; Fei, B.; Ren, G.; Jin, S. Study on the impact of digital finance on agricultural carbon emissions from a spatial perspective: An analysis based on provincial panel data. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Q. Rural Inclusive Finance and Agricultural Carbon Reduction: Evidence from China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 9806–9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginn, W. Agricultural fluctuations and global economic conditions. Rev. World Econ. 2024, 160, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.; Rahmi, R.; Maksalmina, M.; Hamdiah, C.; Sunaya, C. The role of inclusive finance in reducing poverty: A comparison of traditional and Sharia loan models. In Proceedings of the 2nd Medan International Conference on Economic and Business, Medan, Indonesia, 4 July 2024; Volume 2, pp. 1093–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Mritunjay, M. AI-Driven Credit Risk Assessment in Agriculture: A Case Study of Indian Commercial Banks. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2024, 3, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y. The impact of the digital economy on high-quality agricultural development—Based on the regulatory effects of financial development. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, L.; She, Z.; Chen, S. Influence of Digital Literacy on Farmers’ Adoption Behavior of Low-Carbon Agricultural Technology: Chain Intermediary Role Based on Capital Endowment and Adoption Willingness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, G. Digital inclusive finance, spatial spillover effects and relative rural poverty alleviation: Evidence from China. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2024, 17, 1129–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Ye, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, W.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, G. The impact of labor force aging on agricultural total factor productivity of farmers in China: Implications for food sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1434604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Huang, S.Z. The effect of environmental regulation and green subsidies on agricultural low-carbon production behavior: A survey of new agricultural management entities in Guangdong Province. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Kouzez, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Msolli, B.; Rjiba, H. Does increasing environmental policy stringency enhance renewable energy consumption in OECD countries? Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Chen, L. Assessment of agricultural carbon emissions and their spatiotemporal changes in China, 1997–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hu, P.; Diao, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Environmental performance evaluation of policies in main grain producing areas: From the perspective of agricultural carbon emissions. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liang, C.; Feng, Y.; Hu, F. Impact of the digital economy on high-quality urban economic development: Evidence from Chinese cities. Econ. Model. 2023, 120, 106194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.L.; Zhang, J.B.; He, K. The direct influence and indirect spillover effect of urbanization on agricultural carbon productivity based on the spatial Durbin model. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2019, 40, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Bae, J. Urbanization and industrialization impact of CO2 emissions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, B.; Li, J.L. Internet, urbanization and total factor productivity of agricultural production. Rural Econ. 2019, 10, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhong, L.; Li, Q. Urban–rural disparities in household energy and electricity consumption under the influence of electricity price reform policies. Energy Policy 2024, 184, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, R. Can digitalization levels affect agricultural total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 860780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baležentis, T. Frontier Methods for Analysis of the Productive Efficiency and Total Factor Productivity: Lithuanian Agriculture After Accession to the European Union. Ph.D. Dissertation, Vilniaus Universitetas, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Battese, G.E.; Coelli, T.J. A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Econ. 1995, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Zhang, J.; He, Y. Research on spatial-temporal characteristics and driving factor of agricultural carbon emissions in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M. The influence of environmental regulation on industrial structure upgrading: Based on the strategic interaction behavior of environmental regulation among local governments. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 170, 120930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, B. The effect of industrial agglomeration on China’s carbon intensity: Evidence from a dynamic panel model and a mediation effect model. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Guo, H.; Xu, S.; Pan, C. Environmental regulations and agricultural carbon emissions efficiency: Evidence from rural China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).