1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most rapidly expIanding and strategically significant sectors in Türkiye. As a result, the number of international tourists is steadily increasing and this growth is linear until 2019. According to statistics provided by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the number of tourists reached 1.5 billion in 2019 in the world. International tourist arrivals (overnight visitors) also increased by 5% in the first quarter of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024, or 3% above pre-pandemic 2019 [

1]. By 2030, this figure is expected to continue to increase with an estimated 1.8 billion international tourists. This increase is sometimes interrupted by social incidents and other reasons. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath have led to some changes in forecasts [

2]. In addition, although cross-country tourism attracts the most attention, statistically, most of all tourism is domestic, and the ratio of domestic tourism to cross-country tourism is around 85% [

3]. The growth of tourism has brought with it growing concerns about the sustainability of the tourism sector and the limits to its growth [

4,

5].

The concept of sustainable tourism has significantly influenced the formulation of policies and initiatives aimed at preserving tourism resources and communities, establishing itself as a crucial principle for the future of the industry. With the increase in the number of national and international tourists, their length of stay, and their environmental impact, the importance of sustainable tourism has grown significantly [

6]. Although sustainable tourism remains a controversial topic in terms of subject matter and scope within the tourism sector, it is widely regarded as an equilibrium among financial, ecological, and cultural and social requirements [

7]. Sustainable tourism addresses the full range of environmental, cultural, and economic growth as specified by multi-criteria decision-making [

8]. There have been many studies on sustainable tourism using multi-criteria decision-making techniques and they have mainly addressed topics such as exploring potential destinations for ecotourism [

9], ecotourism and sustainable tourism trends [

10], management of sustainable tourist development [

11], and valuing low-carbon tourism scenic spot performance [

12].

Additionally, sustainable tourism plays a crucial role in mitigating the negative impacts caused by the growing influence of tourism on the number of tourists visiting a facility and the efficient operation of the facility. Sustainable tourism includes waste reduction from the facility, energy savings, greener alternative fuels, and green human resources [

13]. In addition, the energy consumption per unit time of a tourism facility and the associated high greenhouse gas, production of waste, pollution of air, and slow adoption of appropriate environmental practices by various industries that damage natural ecosystems, depending on the type of fuel used, continues to be one of the foremost problems to tourism sustainability. Therefore, one of the most critical issues facing the sustainable tourism sector is tourism intensity management, which entails distributing and regulating the number of visitors. Key elements in these challenges are directly related to the effective use of the tourism facility [

3]. Sustainable tourism takes into account not only environmental and ecological impacts but also the sustainability of tourism activities. Sustainability of activities can therefore be explained by two premises. These are multi-criteria decisions that need to be adapted to different personal situations and different attitudes towards tourism sustainability. In some cases, customers do not consider sustainability (traditional tourism), while in other cases, sustainability is a key element in decisions [

14].

With its diverse geographical features and types of facilities, Türkiye has the potential to rise to the top of the world economy by 2041 by increasing the quality of its young workforce in the tourism sector to ensure long-term sustainable economic growth [

15]. Türkiye, with its abundant natural and cultural resources, is in a significant position in tourism activities because of the peaks it will reach in the value chain over the course of the next thirty years [

16,

17]. In terms of the tourism sector, Türkiye is one nation that stands to gain from the demographics of emerging countries. Today, tourism is a significant industry rather than a sector [

18,

19]. By the 2050s, tourism is predicted by the World Travel and Tourism Council to overtake all other sectors as the largest in the world. It is projected that Türkiye’s economic future will undergo significant changes by 2041 [

20,

21]. The rapid increase in the number of tourists visiting Türkiye, particularly since the 2000s, has positioned the country among the top global destinations. While this growth contributes significantly to economic development and employment, it also raises questions about sustainable development. Previous studies emphasize that increasing arrivals can lead to greater energy and water consumption, waste generation, and pressures on local infrastructure and ecosystems [

6]. In the Turkish context, Tosun (2001) [

16] underlines the challenges of aligning tourism growth with sustainable development, while Yüzbaşıoğlu et al. (2014) [

17] stress the role of tourism enterprises in ensuring destination sustainability. Thus, analyzing the interplay between tourist numbers and sustainability dimensions is essential for understanding Türkiye’s long-term tourism trajectory. By integrating these concerns, the present study contributes to ongoing debates on whether quantitative growth in arrivals can be reconciled with sustainable development objectives.

In addition to economic performance, the sustainability of tourism must also be evaluated through environmental and social dimensions. According to national reports, Türkiye’s tourism sector is among the largest consumers of energy and water resources, particularly in coastal destinations, and generates significant solid waste and greenhouse gas emissions during peak seasons. The Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) have emphasized the growing need to integrate sustainability indicators such as resource efficiency, waste management, and carbon footprint into sectoral monitoring. On the social side, tourism plays a crucial role in regional development, creating employment opportunities and cultural heritage preservation, yet rapid growth can also lead to congestion, rising costs of living, and reduced quality of life for residents. By referring to the UNWTO’s Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST) and Türkiye’s national SDG indicator set, this study aims to contribute to the expanding policy perspective that links tourism growth with environmental stewardship and social well-being.

The tourism sector has an essential place in the sustainability literature not only for its benefits, such as global economic development, job creation, and foreign exchange earnings, but also for its environmental and socio-cultural impacts. Therefore, long-term and systematic data are essential for analysing the sustainability performance of tourism activities and developing effective policies [

22,

23]. In general, keeping statistical indicators such as the number of tourist arrivals, the number of overnight stays, the average length of stay, and the occupancy rate is extremely important for the sustainability of tourism. This allows an assessment of the relationship between tourism activities in a country and sustainability components such as environmental resource use, infrastructure pressure, and demand intensity. In Türkiye, these indicators are kept by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) and data have been regularly recorded since 1976 [

24,

25]. In this context, understanding and managing problems such as overcrowding, seasonality, and seasonal instability in the tourism sector, and crisis impacts on the national economy, is impossible without long-term data tracking. At the same time, developing sustainable tourism indicators requires analysis over a period of years; international organizations such as the UNWTO recommend corporate indicator sets in this context [

26]. Moreover, the Tourism Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST) developed by the United Nations World Tourism Organization [

26] is a widely accepted reference point in the international literature. In this context, our study analysed the measures (arrivals, overnight stays, average length of stay, occupancy rate) that overlap with the indicators proposed by SF-MST using long-term (2000–2024) official statistics for Türkiye and applied the TOPSIS method as a decision support tool. Hence, the study aims to provide a long-term assessment for Türkiye, while presenting results that are consistent and comparable with the methodological approaches in the existing literature.

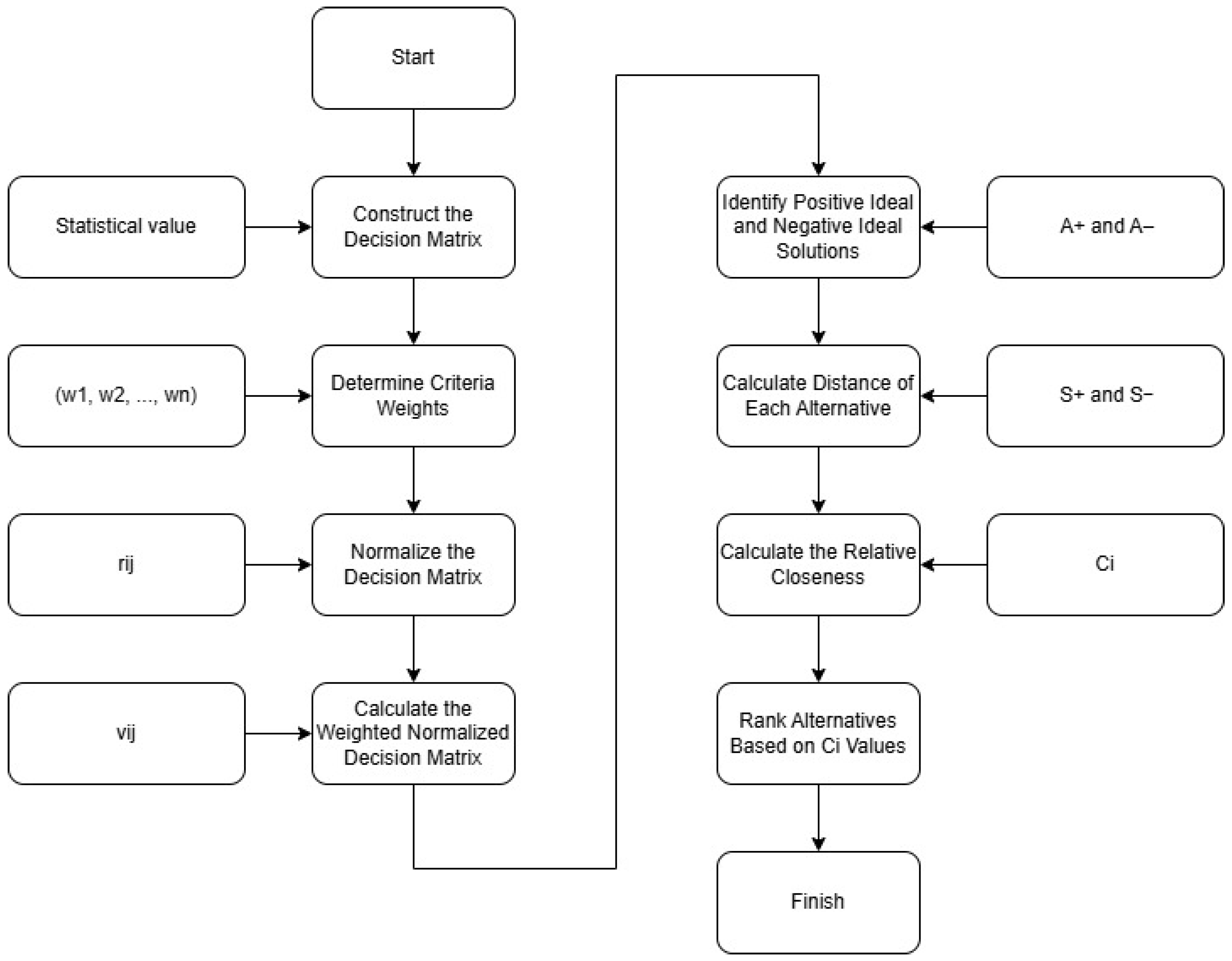

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the long-term sustainability performance of the Turkish tourism sector between 2000 and 2024 using official national statistics. The study pursues three main objectives: (i) to identify temporal trends in key tourism indicators such as arrivals, overnight stays, average length of stay, and occupancy rates; (ii) to assess the impact of exogenous shocks such as economic crises and the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism sustainability; and (iii) to rank annual tourism sustainability performance by integrating multiple indicators into a composite framework. Based on the literature, we hypothesize that (H1) despite short-term crises, the long-term trend in tourist arrivals and overnight stays in Türkiye is upward; (H2) the average length of stay shows a persistent declining trend, consistent with global tourism patterns; and (H3) years of crisis (e.g., 2016, 2020) exhibit significantly lower sustainability performance scores. To address these objectives, the methodology combines min–max normalization to standardize indicators, year-on-year percentage change analysis to capture temporal dynamics, and the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) to integrate indicators into a composite sustainability performance ranking. This quantitative design provides a transparent, replicable, and policy-relevant assessment framework.

This study makes an essential contribution to the literature in terms of assessing sustainability trends in Türkiye’s tourism with a holistic approach based on long-term (2000–2024) official accommodation statistics. While the existing literature generally focuses on short-term data or regional analyses, this study comparatively evaluates sustainability performance using time series data spanning 25 years at the national level using normalized indicators, annual percentage change analysis (YoY), and multi-criteria decision-making techniques such as Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS). The study also analyses the effects of exogenous shocks such as pandemics and economic crises on tourism performance in a holistic manner using quantitative methods. Sustainability performance in tourism is ranked on a yearly basis, and thus, it is aimed to develop a model that can serve as a decision support tool for policymakers. Moreover, the long-term integration of indicators such as overnight stays and occupancy rates, which have limited coverage in the literature, is one of the main features that distinguish this study from similar ones. The study analyses sustainable tourism trends in depth, not only in absolute values but also in normalized scores and relative performance rankings. In these respects, the study provides a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework for tourism sustainability in Türkiye and makes an innovative methodological contribution to both academic and applied research.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows normalized data for the years 2000 to 2024. The findings highlight crucial trends and turning moments in Türkiye’s tourist industry. Tourist arrivals and overnight stays have increased significantly, notably from 2022 to 2024, demonstrating a robust post-pandemic rebound and renewed impetus in the economy. However, one of the most important points to note is that there has been a significant decline in the average length of stay. This figure, which peaked in 2012, has fallen to its lowest level in 2024. This shows that, despite the increase in the number of tourists, trips are becoming shorter. If we examine the main reasons for this, we can see that, first of all, a large proportion of tourists may be opting for short trips such as weekend getaways. In addition, the proliferation of low-cost airlines has been widely associated with the rise of short-haul trips and weekend getaways, leading to shorter average lengths of stay [

40]. Moreover, the diversification of tourist motivations, including business travel and urban tourism, has been highlighted in recent studies as a factor influencing shorter stays [

41]. Finally, evolving tourist profiles and generational travel habits, particularly among younger travellers, have been shown to favor more frequent but shorter trips. These factors collectively help to explain the observed decline in average length of stay.

When examining occupancy rate statistics, it can be seen that the occupancy rate follows a parallel trend with arrival and overnight stay data. After reaching its peak in 2019, the occupancy rate experienced a significant decline in 2020 due to the pandemic; however, it has shown signs of recovery as of 2021. The year 2020 in particular saw a sharp decline in all statistical indicators. This year clearly reflects the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector. However, the recovery that followed in 2021 also demonstrates the resilience of the tourism sector. Overall, Turkish tourism has shown a successful trend in terms of visitor numbers during the post-pandemic recovery process. However, the decrease in length of stay is an important warning sign in terms of the sector’s revenue sustainability. Therefore, it is considered that future tourism policies should not only focus on increasing the number of tourists but also on encouraging them to stay longer. The development of regional tourism, diversified tourism products, and infrastructure investments is of critical importance in this regard.

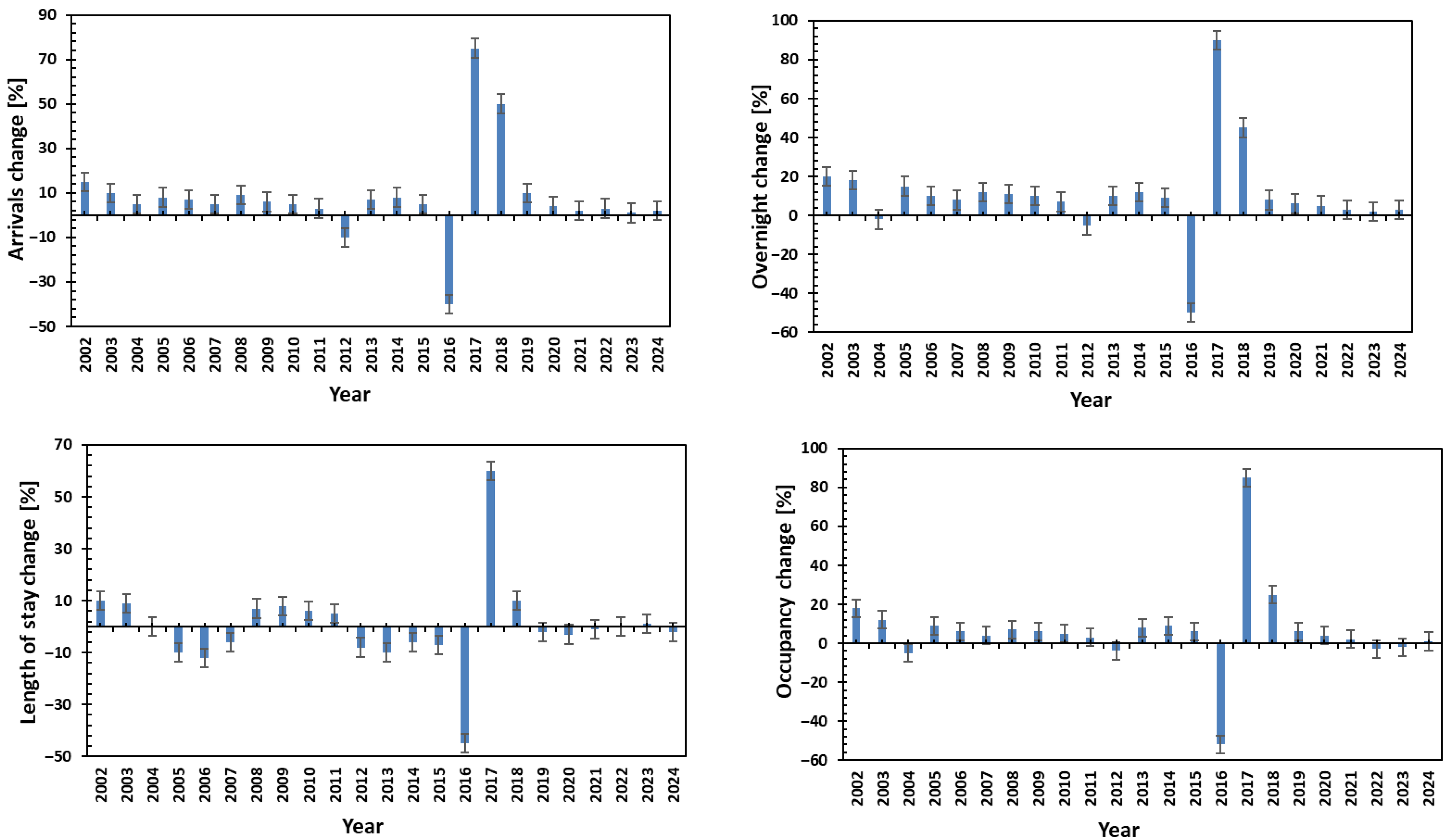

Table 2 represents the annual percentage changes in four key indicators for the tourism sector between 2001 and 2024: number of tourists, number of overnight stays, average length of stay, and occupancy rate. The analysis evaluates findings such as developments in the sector, periods of crisis, and recovery processes. Since 2001, there has been a positive trend in Türkiye, with tourism indicators steadily increasing. There has been a noticeable long-term upward trend in the number of tourists and overnight stays. In particular, the years 2004, 2011, 2018, and 2021 stand out as years of positive developments for the sector, with high rates of increase. However, there has been a general downward trend in the average length of stay over time. This indicates that, despite the increase in the number of tourists, the individual length of stay has decreased. Findings from 2003 and 2006 show a decline in tourism indicators. This situation was observed mainly in the significant decline in the length of stay and occupancy rates during these periods. In addition, 2016 was a crisis year in which negative values were seen in all indicators. This decline in 2016 is believed to be related to political developments and foreign policy issues in Türkiye. In addition, 2020 stands out as the period in which the tourism sector experienced its most severe contraction due to the impact of the pandemic. All indicators showed significant declines. These declines were approximately −59.6%, −59.3%, −15.9% and −61.2% for the number of incoming tourists, the number of overnight stays, the average length of stay, and the occupancy rate, respectively. These results clearly demonstrate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global tourism.

Following the pandemic, the sector entered a strong recovery process in 2021. All indicators recorded historic increases. This situation can be explained by both a base effect and the emergence of deferred demand. Growth continued in 2022, but the rate of increase began to slow down. Data for 2023 and 2024 indicate a renewed slowdown or stagnation in the sector. In particular, the average length of stay indicator recorded negative values again in 2023 and 2024. Although the average length of stay has fluctuated over the years, it has generally shown a negative trend. In 2017, this indicator experienced a significant decline of −11.3%. The occupancy rate has generally been one of the most sensitive variables to sectoral crises. Significant declines were observed in 2016 and 2020, but a historic increase of 85.3% was recorded in 2021.

Figure 2 has been normalized using Min-Max based on annual percentage changes and is expressed using both line and scatter charts. This method has made it possible to evaluate the relative performance of each indicator over time. According to the normalisation results, significant fluctuations have been observed over time among tourism indicators. The year 2020 has the lowest normalized values in all four indicators (close to 0) due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This situation indicates that tourism activities have almost completely stopped. In 2021 and 2022, the post-pandemic recovery process began, and the indicators rose to a range of 0.75% to 1.0% of normalized values. This increase was most noticeable in the overnight stay rate (1.0 normalized value in 2021). The year 2024 has values close to the normalized peak for many indicators. In particular, the total arrivals and occupancy rate indicators are very close to the highest normalized value of 1.0 in this year. This indicates that the recovery after the pandemic is largely complete. During the period under review, the average length of stay has been lower and more volatile than other indicators. In 2017, this indicator experienced a significant decline of −11.37%, causing it to fall to approximately 0.2 of the normalized value this year. This trend indicates that tourists are preferring shorter visits and that long-term stays are decreasing. The occupancy rate stands out as the most sensitive indicator of crisis periods. Significant declines (−18.7% and −61.2%) were observed in 2016 and 2020, respectively, while a rapid recovery was experienced in 2017 and 2021. The year 2021 marked the period with the highest historical increase in occupancy rate, with an 85.3% rise. The distribution graph clearly shows the relative performance of each year. The years 2004, 2011, 2018, 2021, and 2024 stand out as positive years in terms of many indicators. In particular, 2024 stands out as a highly successful year, with a high concentration of points in both the line and distribution graphs. These findings highlight the importance of strategic planning and flexible policies to be developed in response to external shocks in the tourism sector.

The observed dynamics in Türkiye are broadly consistent with global tourism trends. According to UNWTO, worldwide international tourist arrivals reached around 1.4 billion in 2024, recovering to 99% of pre-pandemic 2019 levels and recording an 11% annual growth [

1]. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) reported that the global tourism sector contributed a record 11.1 trillion USD to world GDP in 2024, representing 10% of global output and exceeding the 2019 peak by 7.5% [

42]. From a longer-term perspective, international arrivals more than doubled since 2000, and UNWTO projections estimate an average annual growth rate of 3.3% between 2010 and 2030, reaching 1.8 billion by 2030 [

43]. The declining trend in the average length of stay observed in Türkiye is also consistent with global patterns, particularly in Europe, where the proliferation of low-cost airlines and changing travel behaviors have contributed to more frequent but shorter trips [

40]. These parallels highlight that the Turkish case reflects not only domestic conditions but also structural transformations in global tourism demand.

Figure 3 shows the annual rates of change in four key tourism indicators between 2002 and 2024. When the findings are examined, the total growth rates, which have fluctuated over the years, showed a dramatic decline (around −45%) in 2020 in particular. Following this decline, significant increases of approximately 75% and 50% were observed in 2021 and 2022, respectively. This situation demonstrates the rapid recovery of the sector following the impact of the pandemic. When examining the total overnight stay (%) ratio, overnight stay data also shows a parallel trend with arrival data, with a sharp decline (−55%) in 2020. In 2021, an increase of over 90% was observed in this indicator. This increase can be explained by the realisation of postponed trips. Changes in the average length of stay should be less volatile, but there was a significant decrease of −15% in 2020. Although there was a positive recovery in the following year, overall instability was observed in the indicator. Finally, the occupancy rate experienced a dramatic decline of over 50% in 2020, but there was a remarkable recovery in 2021 with an increase of nearly 80%. However, stability in occupancy rates has not been fully achieved in subsequent years.

Annual fluctuations in the tourism sector are highly sensitive to global economic, political, and health developments. The sharp declines in 2020 in particular clearly demonstrate the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sector. This year saw declines of 40–60% across all indicators, followed by high-rate increases in subsequent years due to the “base effect.” These recoveries were made possible by the resumption of postponed travel in 2021 and 2022. However, imbalances in average length of stay and occupancy rates indicate that quantitative recovery alone is insufficient; factors such as service quality, pricing policies, and destination competitiveness also play a significant role. Fluctuations in indicators highlight the tourism sector’s vulnerability in terms of sustainability and the need to enhance its resilience to external shocks. In this regard, strengthening sectoral planning and crisis management strategies is recommended.

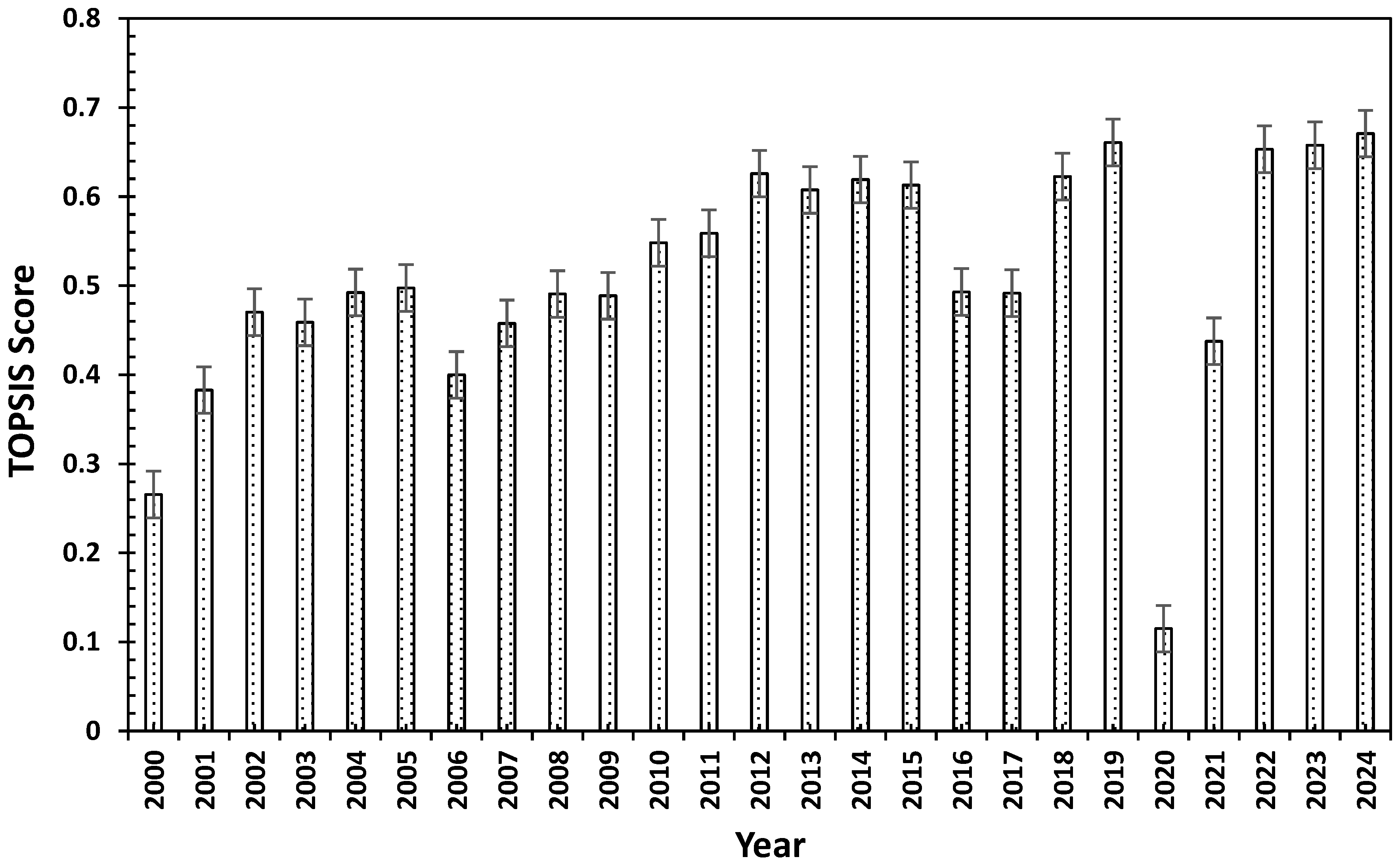

Sustainability performance in tourism by year has been calculated using the TOPSIS method and ranked in

Figure 4. The year with the highest sustainability performance was determined to be 2024, followed by 2019, 2023, and 2022. These results indicate the years in which tourism was most balanced and robust in terms of development, overnight stays, length of stay, and occupancy rates.

Despite providing valuable insights into long-term tourism sustainability trends, this study has several methodological limitations. First, no advanced time-series models (e.g., ARIMA or VAR) were employed to forecast future dynamics, nor were statistical tests applied to assess the significance of year-to-year changes. Second, the analysis did not explicitly examine interrelationships among indicators, such as whether declines in average length of stay are associated with fluctuations in arrivals or occupancy. Third, as the study is based on annual national-level data, seasonal variation and volatility in tourism dynamics were not captured. Future research could overcome these limitations by applying econometric time-series models, correlation or causality analyses among indicators, and incorporating higher-frequency (monthly or quarterly) data to capture seasonality. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the application of TOPSIS in this context mainly functions as a ranking exercise. Given the steadily increasing trend in arrivals and overnight stays, the method predictably identifies the most recent years as top performers. This limitation reduces the explanatory depth of the approach. Future studies could complement TOPSIS with alternative methods such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), or econometric models that may better capture causal relationships and structural dynamics. Although this study focuses on performance indicators such as arrivals, overnight stays, average length of stay, and occupancy rates, these indicators are directly linked to environmental and energy-related issues. For example, increased tourist arrivals and longer stays lead to increased water and energy consumption, more waste generation, and carbon emissions from transportation/hospitality activities. Similarly, high occupancy rates can put pressure on local infrastructure and natural resources, especially during peak seasons. In this context, the quantitative indicators used in the study provide an indirect representation of the environmental burden and energy consumption dimensions of sustainability, even if they do not contain direct environmental data [

44,

45]. Increased arrivals and overnight stays result in higher energy and water consumption, increased waste production, and elevated greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in peak seasons. Thus, these metrics indirectly reflect environmental pressure levels. Shorter average stays may limit tourists’ engagement with local culture and traditions, potentially weakening socio-cultural exchange. High occupancy rates, especially in urban or coastal destinations, can lead to crowding, higher living costs, and socio-spatial displacement of local communities.

The statistical findings of this study can be directly linked to sustainability challenges. For instance, the persistent decline in the average length of stay suggests a trend toward short-term visits, which may limit deeper engagement with local culture and reduce the socio-cultural benefits of tourism. Similarly, high occupancy rates, while positive for revenue, may intensify pressure on local infrastructure, increase energy and water consumption, and amplify waste generation in destinations, particularly in coastal areas. These patterns highlight the environmental risks of over-concentration and the social risks of reduced community satisfaction. Integrating national environmental indicators—such as per capita water consumption, energy use, and tourism-related CO2 emissions—into future analyses would provide a more direct link between tourism performance and environmental sustainability. At the same time, socio-cultural indicators such as tourism employment, income distribution, and local resident perceptions should be systematically monitored to ensure that growth is inclusive and equitable.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a 25-year longitudinal assessment of the sustainability performance of the Turkish tourism sector between 2000 and 2024 by evaluating arrivals, overnight stays, average length of stay, and occupancy rates through normalization, YoY change analysis, and the TOPSIS method. The results reveal a robust upward trend in arrivals and overnight stays, alongside persistent vulnerabilities, including the long-term decline in the average length of stay and the volatility of occupancy rates during crisis years such as 2016 and 2020. These findings highlight that sustainable tourism development requires not only quantitative growth but also stability, resilience, and qualitative improvements.

From a theoretical perspective, this research advances the scholarly debate on sustainable tourism by linking long-term monitoring of official statistics with decision-support models. It supports prior claims that emerging destinations face a paradox of growth: while quantitative indicators improve, qualitative sustainability dimensions erode. By aligning with UNWTO’s Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST) and applying a multi-criteria ranking model, this study offers a replicable and transparent framework that extends previous applications in Spain and China while situating the Turkish case in the wider global discourse on reconciling growth and sustainability.

In practical terms, the findings provide actionable guidance for policymakers and destination managers. To strengthen sustainability, strategies should focus on encouraging longer tourist stays through product diversification and regional development, reducing seasonality with off-peak demand stimulation, and building resilience through crisis management and sustainability-oriented infrastructure. Embedding these strategies within international indicator frameworks such as the SF-MST will enable systematic benchmarking and policy alignment with global best practices.

The prospects for applying this approach are promising. The framework can serve as a decision-support tool for institutions, tourism authorities, and international organizations, allowing them to monitor long-term trends, benchmark annual performance, and anticipate vulnerabilities. Furthermore, it can be adapted to other destinations or comparative cross-country studies, thereby enhancing its relevance beyond the Turkish context. At the same time, its application is limited by the reliance on annual, national-level data, the use of only four quantitative indicators that indirectly approximate environmental and socio-cultural dimensions, and the methodological constraints of TOPSIS, which ranks performance but does not capture causal relationships or predict future dynamics.

Future studies should address these limitations by incorporating higher-frequency and regional data, expanding the scope of indicators to include environmental and cultural dimensions, and applying econometric or forecasting methods to strengthen explanatory depth and predictive capability. Such extensions would enhance the framework’s academic contribution and policy utility.

Strengthening the sustainability of Türkiye’s tourism sector requires embedding environmental and social dimensions into long-term monitoring frameworks. Beyond tracking arrivals, overnights, and occupancy, policymakers should adopt composite indicators that also reflect environmental pressures (energy and water use, waste generation, greenhouse gas emissions) and socio-cultural outcomes (employment, regional equity, and community well-being). Incorporating these dimensions into national tourism statistics, in line with the UNWTO SF-MST and SDG frameworks, would allow more comprehensive benchmarking and enhance policy relevance. The findings of this study underline that sustainable growth is not merely about quantitative expansion but also about ensuring ecological resilience and social inclusiveness. By integrating these dimensions into tourism strategies, Türkiye can achieve a balanced pathway toward sustainable development in the decades to come.

In conclusion, while the Turkish tourism sector has demonstrated a strong recovery in terms of visitor volume, its sustainability remains fragile due to qualitative declines and external shocks. Achieving long-term sustainability will require moving beyond the pursuit of growth alone toward a model that balances economic gains with environmental stewardship, cultural vitality, and social well-being. By providing a transparent and adaptable evaluation framework, this study equips scholars and policymakers with a practical tool to monitor progress, inform strategic choices, and reinforce tourism’s resilience in the decades to come.