Abstract

Understanding the impact and mechanisms of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation is crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of wildlife protection in nature reserves. Based on survey data from 186 farmers around the Jiyuan Macaque Natural Reserve in Henan Province, this study employs an ordered probit model to examine how livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to engage in wildlife conservation. Additionally, mediating and moderating effect models are used to explore the mediating role of perceived living conditions and the moderating role of farmers’ policy cognition. The key findings are threefold: (1) Livelihood capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. (2) Perceived living conditions significantly mediate the relationship between capital and farmers’ willingness to participate. (3) Farmers’ awareness of ecotourism policies positively moderates the effect of livelihood capital on their willingness to participate, whereas awareness of wildlife damage compensation policies does not show a significant moderating effect. Therefore, it is recommended that the government should focus on enhancing farmers’ livelihood capital, improving their perceived living conditions, and strengthen policy publicity and awareness.

1. Introduction

China has proposed the establishment of a modern society where humans and nature coexist harmoniously. Biodiversity is the foundation of life for humans and nature, and the basis for human society’s survival and development [1,2,3]. As a vital component of biodiversity, wildlife is closely intertwined with human social development [4,5], and its conservation has garnered considerable attention from the Chinese government [6]. The establishment of nature reserves for in situ conservation is widely regarded as one of the most effective approaches to protecting biodiversity [7]. Notably, the willingness of farmers in communities surrounding nature reserves to participate in wildlife conservation plays a critical role in the success of these efforts [8,9]; however, nature reserves are also among the regions with the highest density of wildlife species [10]. As wildlife populations recover and expand, their activity areas increasingly overlap with the lives and production spaces of surrounding farmer communities. This overlap is associated with a rising frequency of wildlife-related incidents, which exacerbates conflicts between community development and wildlife conservation [11,12], ultimately diminishing farmers’ willingness to participate in conservation efforts. Therefore, enhancing farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation and improving the effectiveness of conservation efforts in nature reserves are crucial for strengthening the development and management of these areas, and achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

With China’s comprehensive success in poverty alleviation and the advancement of its rural revitalization strategy [13], farmers’ livelihood strategies are inevitably shifting toward diversification and increased nonagricultural activities. This transformation has strengthened their livelihood capital and improved their overall living conditions [14]. Livelihood capital encompasses tangible and intangible resources possessed by farm households, and is categorized into five core dimensions: natural capital (arable and forest land for agriculture), financial capital (income, savings, and loan conditions), human capital (education, skills, and labor capacity), social capital (social networks, trust, and cooperative memberships), and physical capital (livestock, housing, and production equipment). These assets constitute the foundation for developing livelihood strategies and directly influence farmers’ perceptions and decision making, thereby shaping their willingness and behavior toward ecological environment protection [15,16,17]. Does livelihood capital impact farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, and what are the underlying mechanisms? This study addresses these questions using survey data collected from 186 farmers in the Jiyuan section of the Taihangshan Macaque Natural Reserve in Henan Province. An ordered probit model is employed to analyze the effect of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Additionally, the study explores the mediating role of perceived living conditions and the moderating role of policy cognition. The findings aim to enrich and deepen the existing body of research, providing practical insights to enhance the effectiveness of wildlife conservation in nature reserves and promote harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

2. Literature Review

Farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation is a crucial aspect of biodiversity protection. It reflects both their intention to avoid harming wildlife and their active engagement in conservation efforts, such as opposing wildlife harm, participating in rescue activities, and advocating for wildlife protection [18]. In recent years, both domestic and international researchers have extensively examined the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, with a primary focus on three areas. First, personal and household characteristics, particularly livelihood capital, encompass financial, physical, natural, human, and social dimensions, each of which can affect farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. One study demonstrated that higher financial and physical capital that enhances household income and housing quality increases farmers’ conservation willingness, while restrictions on arable land due to conservation policies have a negative impact [19]. Among human capital factors, age negatively affects conservation willingness, whereas higher education has a positive effect [20]. In the realm of social capital, having experience as a village official or membership in social organizations can influence farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation [10,21]. Second, psychological cognition examines how risk perception, ecological awareness, traditional culture values, and subjective wellbeing affect farmers’ conservation willingness. Research indicates that farmers’ willingness to engage in wildlife conservation decreases when they perceive wildlife as a significant livelihood threat to their livelihoods [22]. Conversely, educating farmers about conservation can improve their ecological awareness and increase their willingness to protect wildlife [23,24]. Traditional culture also influences conservation willingness. Wellbeing significantly increases conservation willingness [1,25,26,27]. Third, policies and institutional factors, such as wildlife damage compensation and ecotourism initiatives also influence farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Wildlife damage compensation enhances farmers’ participation in wildlife conservation [10]. Encouraging farmers to engage in ecotourism can increase their income and enhance their recognition of ecological value, thereby further stimulating their willingness to engage in conservation efforts [28]. Notably, livelihood capital, which comprises essential resources for survival and development, forms the basis for farmers’ livelihood activities and is often used to investigate their economic and social decision-making processes [16]. Previous research has shown that livelihood capital directly influences farmers’ willingness to participate in ecological protection activities, including the adoption of clean energy [29], participation in village environmental governance [16], and involvement in green agricultural production [30].

In summary, existing research provides a solid foundation for this study; however, several gaps remain: First, prior studies have mainly focused on the impact of individual or a few aspects of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, leading to a lack of comprehensive empirical analysis on how all dimensions of livelihood capital collectively influence this willingness. Second, although some studies have cited the impact of farmers’ psychological perception of living conditions on their willingness to engage in wildlife conservation, few have integrated livelihood capital and perceived living conditions within the same analytical framework. Generally, the effect of livelihood capital on farmers’ behavior is mediated through changed perceptions. Farmers’ living conditions are highly influenced by livelihood capital and affect their intentions [31,32,33]. Third, farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation is influenced by policies such as wildlife damage compensation and ecotourism; however, previous research has primarily focused on the direct impact of such policies on wildlife conservation, rarely considering the moderating role of farmers’ policy perceptions.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. The Impact of Livelihood Capital on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Wildlife Conservation

Nature reserve protection policies often increase costs to farmers in surrounding communities which can reduce their participation in wildlife conservation [10]. Livelihood capital encompasses financial resources (such as savings and loans), human resources (such as skills and education), social resources (including networks and support), and natural resources such as land and water. Collectively, these various resources, are fundamental to farmers’ livelihood choices and their ability to manage risks [34]. Therefore, the level of livelihood capital directly influences farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

This study adopts the Sustainable Livelihood Framework developed by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), which categorizes livelihood capital into five types: natural, financial, human, social, and physical capital [35]. Natural capital refers to the natural resources available for production and daily life, and is typically measured by the amount of arable land and forest land a household possesses. Farmers with abundant natural capital tend to be more dependent on these resources and are more likely to utilize them intensively. However, the implementation of nature reserve policies and the occurrence of wildlife-related incidents can negatively affect their ability to use these resources [36], generating resentment toward wildlife conservation, with a potential negative impact on farmers’ willingness to participate in such activities. Financial capital refers to the funds and financial assets available to farmers, which is measured by household income, savings, and loan conditions.

Farmers with higher financial capital have superior economic conditions and stronger capabilities to manage risks, enabling them to bear the costs associated with ecological conservation efforts [16]. Therefore, financial capital is likely to enhance farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Human capital encompasses farmers’ knowledge, skills, and labor capacity for daily production and living, which is often measured by the quantity and quality of household labor. Higher human capital allows farm households to engage in diverse livelihood activities, mitigating the negative impact of wildlife conservation on their livelihoods [19], which may result in a higher willingness to participate. Additionally, as human capital accumulates, farmers’ understanding of wildlife conservation deepens, which further promotes active participation [10]. The relationship between human capital accumulation and enhanced understanding of wildlife conservation among farmers is rooted in education and experience. As farmers gain more knowledge, skills, and labor capacity through education and training, they become better informed about the importance and methods of conservation. This deeper understanding fosters a stronger sense of responsibility and awareness towards wildlife, thus promoting their active participation in conservation efforts. Social capital includes the social resources farmers can access, which is often measured by kinship ties and cooperative membership. Higher social capital enables farmers to engage in mutual assistance and reduces information asymmetry [37], enhancing their risk management capabilities and understanding of wildlife conservation, increasing their willingness to participate. Information asymmetry refers to the unequal distribution of knowledge or information among individuals or groups. Higher social capital among farmers facilitates access to a broader network of information sources, enabling farmers to share knowledge and resources more effectively. This reduces information asymmetry as farmers are better informed about conservation policies, practices, and opportunities, thereby enhancing their capacity to engage in wildlife conservation activities. Physical capital comprises the tangible assets available for production and living, such as livestock, housing conditions, and production equipment. Physical capital is often fixed and difficult to mobilize or convert [38]. More physical capital enables farmers to be more attuned to natural environmental changes, thereby enhancing their motivation to safeguard local ecosystems [39]. This indicates a positive correlation between physical capital and farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation efforts. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

Livelihood capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

H1-1.

Natural capital has a significant negative effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

H1-2.

Financial capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

H1-3.

Human capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

H1-4.

Social capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

H1-5.

Physical capital has a significant positive effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

3.2. Mediating Effect of Perceived Living Conditions

According to behavioral economics theory, the transformation of farmers’ behavioral intentions essentially refers to a shift in their psychological state [40]. Livelihood capital is the bedrock of farmers’ survival and development within the DFID sustainable livelihoods framework. Farmers select appropriate livelihood strategies based on the amount of livelihood capital, leading to different livelihood outcomes [41]. Perceived living conditions, which are a crucial component of these outcomes [42], reflect farmers’ subjective assessment of their actual living status and are closely linked to livelihood capital [43]; therefore, differences in livelihood capital among farmers can result in variations in material living conditions, which subsequently affects perceived living conditions. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that only when farmers’ basic material needs are satisfied will they be motivated to pursue higher-level needs such as environmental protection [44]. Research has demonstrated that individuals’ perceptions of living conditions promote environmental protection [45]. In general, farmers with higher livelihood capital enjoy better living conditions and perceive them positively. This enhances their sense of wellbeing and security, motivating them to protect the natural environment that sustains these conditions. Thus, they are more willing to participate in wildlife conservation efforts. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

Perceived living conditions mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to conserve wildlife.

3.3. Moderating Effect of Policy Cognition

To reduce conflicts between farmers and wildlife and increase farmers’ proactive participation in wildlife conservation, policies advancing wildlife damage compensation and ecotourism have been extensively implemented in China’s nature reserves [4]. The influence of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation may differ based on policy cognition. Farmers’ policy cognition reflects the effectiveness of authorities’ policy dissemination. When policy dissemination is effective, farmers are more likely to feel recognized and respected, which increases their support for the policy and enhances the positive effect of livelihood capital on their willingness to participate in wildlife conservation [46]. Moreover, farmers with higher policy cognition tend to have a better understanding of the policy’s content and specifics [47,48]. This understanding enables them to leverage policy support to maximize their use of livelihood capital and choose livelihood strategies that align with conservation policies. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Policy cognition moderates the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to conserve wildlife.

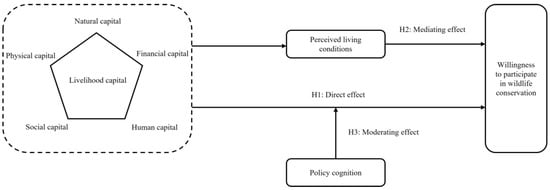

In summary, to examine the theoretical relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation and analyze the mediating effect of perceived living conditions and the moderating effect of policy cognition, we establish the theoretical framework of this study as shown in Figure 1. The effect of livelihood capital and its various dimensions on farmers’ willingness to conserve wildlife is influenced by perceived living conditions. The effect of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to conserve wildlife depends on their level of policy cognition.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

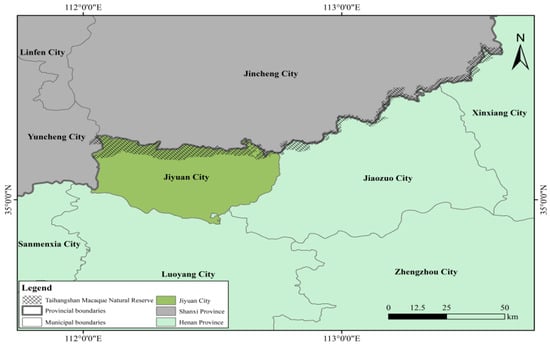

The Taihangshan Macaque Natural Reserve in Henan is a wildlife-oriented nature reserve located in northern Henan Province that spans the cities of Jiyuan, Jiaozuo, and Xinxiang in Henan and borders Yuncheng and Jincheng in Shanxi Province. The geographic coordinates range from 34°54′ to 35°40′ N latitude and 112°02′ to 113°45′ E longitude, covering a total area of 566 km2. This study focuses on a section within Jiyuan City in the northwest of Henan Province, with an area of 302 km2, which is 53% of the total reserve area. A regional map of the research area was drawn with the help of ArcGIS 10.8, a professional geographic information system software (Figure 2). The region boasts abundant wildlife resources such as the northernmost macaque population in the Northern Hemisphere and 60 nationally protected species including leopards, golden eagles, and peregrine falcons. Recently, wildlife protection policies have increased wild animal populations, which has harmed local farmers’ production and livelihoods [49]. Additionally, as one of the first national all-area tourism demonstration zones, Jiyuan City is rich in tourism resources, featuring attractions such as Wangwu Mountain and Wulongkou Scenic Area. The local government is actively promoting the development of rural ecotourism [50].

Figure 2.

Map of the study area.

4.2. Data Sources

The data for this study were collected from a field survey conducted by the research team in the Jiyuan section of the Taihangshan Macaque Natural Reserve in August 2023. To ensure representativeness and scientific validity, the study employed a random sampling method. We employed a stratified random sampling method to ensure representativeness. First, we categorized all villages within the Jiyuan section of the Taihangshan Macaque Natural Reserve into four strata based on their proximity to the reserve: core zone, buffer zone, experimental zone, and areas within 20 km outside the reserve. This stratification accounted for ecological and administrative boundaries. Within each stratum, villages were assigned unique identifiers, and a computer-generated random number table was used to select 19 villages from 6 townships. This method eliminated selection bias and ensured each village had an equal probability of inclusion. The final sample covered diverse geographic and socio-economic conditions, enhancing the generalizability of findings. Responses were deemed valid after verification, A total of 219 questionnaires were distributed, with 186 valid responses after verification, resulting in an effective rate of 85%, ensuring the reliability of the data. The questionnaire covered aspects such as farmers’ personal basic information, household livelihood capital status, willingness to participate in nature reserve construction, wildlife incidents, and tourism participation. Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of the sampled farmers.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of sample farmers (N = 186).

4.3. Variable Selection

4.3.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study is farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Considering existing research [10,17,18,27] and conditions of the surveyed area, this study measures farmers’ willingness to conserve wildlife by examining their participation in rescuing wildlife, advocating wildlife conservation, and in field patrols. For quantitative analysis, we follow the methodology of Ren et al. [51]. First, we constructed a comprehensive evaluation index to assess farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation using the entropy method. Subsequently, this index was standardized and converted into a five-point Likert scale for further analysis: 1 for an index greater than 0 and less than or equal to 0.2, 2 for an index greater than 0.2 and less than or equal to 0.4, 3 for an index greater than 0.4 and less than or equal to 0.6, 4 for an index greater than 0.6 and less than or equal to 0.8, and 5 for an index greater than 0.8.

4.3.2. Independent Variable

The independent variable in this study is farmers’ livelihood capital. Based on the DFID livelihood analysis framework, we measure livelihood in terms of farmers’ natural, financial, human, social, and physical capital. Drawing on previous research [18,51,52], natural capital is measured using per capita arable land and per capita forest land; financial capital by per capita household income, savings, and loan status; human capital by the number of laborers in a household, farmers’ education, and the number of household members receiving skills training; social capital by the degree of trust between relatives and friends, neighborly relations, participation in cooperatives, and social expenditure; and physical capital by livestock holdings, amount of production and living equipment, and housing conditions. We use the entropy method to calculate the weights of each indicator for the core independent variable, resulting in comprehensive scores for each type of livelihood capital and the total livelihood capital.

4.3.3. Mediating Variable

The mediating variable in this study is farmers’ perceived living conditions. Farmers’ perceived living conditions refer to their evaluations of current living status and expectations for future living conditions, which is based on respondents’ satisfaction with income, livelihood methods, basic goods and services, and evaluation of expected changes in living conditions over the next 5 years [26,42,53]. Following Wan et al. [43], we average these indicators to obtain a comprehensive index of farmers’ perceived living conditions.

4.3.4. Moderating Variable

The moderating variable in this study is farmers’ policy cognition, including their understanding of policy and participation in policy implementation [54]. Considering the conditions of the surveyed area, we measured farmers’ cognition of wildlife damage compensation, and ecotourism policies following Zhang et al. [47].

4.3.5. Control Variables

Based on existing research [1,10], this study introduces six control variables across three dimensions: farmers’ individual characteristics, household characteristics, and external environmental characteristics. Specifically, personal characteristics include respondents’ gender and age; family characteristics include family size and the proportion of agricultural income; and external environment characteristics include transportation infrastructure and incidents involving wildlife. Table 2 presents the settings, specific meanings, and basic descriptive statistics of these variables.

Table 2.

Variables, definitions, and descriptive statistics.

4.4. Livelihood Capital Index Measurement

This study employs the entropy method to calculate the weights of different dimensions of farmers’ livelihood capital. The entropy method objectively assigns weights based on the amount of information provided by the observed values of the indicators, which mitigates the bias of subjective weighting and increases the accuracy of the results [55]. The entropy method has been widely used in the comprehensive evaluation of farmers’ livelihood capital [56,57]. The specific calculation steps are detailed below.

First, to avoid the impact of inconsistencies in dimensions and directions among various indicators and to ensure comparability, the original indicators were standardized using the range normalization method. Additionally, to prevent the influence of zero values, the dimensionless values were adjusted by shifting them by 0.0001 units. The formula is as follows:

where X′ij is the standardized value of the j-th indicator for the i-th sample, Xij is the original value, and minXij and maxXij are the minimum and maximum values of the j-th indicator for the i-th sample, respectively. Notably, since all livelihood capital indicators in this study are positive, we employ the positive standardization method.

Second, calculate the proportion of the j-th indicator for the i-th sample across all samples, where m is the number of sample households, as follows:

Third, calculate the information entropy ej of the j-th indicator as follows:

Fourth, calculate the difference coefficient (gj) of the j-th indicator as follows:

Five, calculate the weight (Wj) of each indicator, where n is the number of evaluation indicators as follows:

Six, calculate the comprehensive value (Zi) of each dimension of livelihood capital for each household as follows:

When X′ij is used as the measurement indicator for natural capital, Wj represents the weight of each corresponding indicator, and Zi is the comprehensive index of natural capital, where a higher Zi indicates a higher level of natural capital for the household. This procedure is repeated to obtain comprehensive indices for the other four dimensions of livelihood capital. The total livelihood capital index is the sum of the comprehensive indices for all five dimensions. Therefore, the comprehensive index for total livelihood capital and the indices for different dimensions are the average values of the sample households.

4.5. Model Selection

4.5.1. Baseline Regression Model

As noted previously, the dependent variable in this study is the farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, which is a multivariate ordered variable. Therefore, the following ordered probit model is employed for estimation:

where Ni represents farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation; Ci represents livelihood capital; Ti represents control variables, detailing individual farmers’ characteristics, household characteristics, and external environment characteristics; α0, α1, and α2 are coefficients to be estimated; and ε1i is the error term.

4.5.2. Mediating Effect Model

To examine whether perceived living conditions mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, we reference previous research [58,59], constructing the following models:

where Mi is the mediating variable representing farmers’ perceived living conditions; β0, β1, β2, σ0, σ1, σ2, and σ3 are coefficients to be estimated; and ε2i and ε3i are error terms.

4.5.3. Moderating Effect Model

To test whether policy cognition moderates the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, we reference previous research [60] and introduce an interaction term between livelihood capital and policy cognition, constructing the following model:

where PCi represents policy cognition, including wildlife damage compensation policy and ecotourism policy; Ci × PCi is the interaction term between livelihood capital and policy cognition; γ0, γ1, γ2, γ3, and γ4 are coefficients to be estimated; and ε4i is the error term. If the coefficient of Ci × PCi is significant, this indicates a significant moderating effect.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The Impact of Livelihood Capital on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Wild Life Conservation

This study employs Stata 17.0 to analyze the impact of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation using an ordered probit model. To ensure the validity of the regression results, variance inflation factor (VIF) tests were first conducted to diagnose multicollinearity among variables. The results indicate a maximum VIF of 1.49 and a mean VIF of 1.17, with all VIF values substantially below 10. This confirms the absence of severe multicollinearity issues in the model. According to the regression results of Model 1 in Table 3, livelihood capital has a positive and significant effect on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation at the 1% level. This indicates that higher livelihood capital corresponds to farmers’ stronger willingness to engage in wildlife conservation, which supports H1. One possible reason is that richer livelihood capital means greater risk resistance, which effectively reduces the negative impacts of wildlife conservation and subsequently increases the likelihood of participation. Additionally, as livelihood capital accumulates, farmers’ awareness of ecological protection improves, generating higher conservation enthusiasm. The statement regarding farmers’ enhanced ecological protection awareness with accumulating livelihood capital is supported by Table 3. Specifically, the positive and significant coefficients of natural, financial, human, and social capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation (Models 1 and 2) indicate that higher livelihood capital fosters greater conservation enthusiasm. This suggests that increased livelihood capital contributes to improved ecological awareness and willingness to conserve wildlife.

Table 3.

Baseline regression.

Model 2 in Table 3 reveals that different dimensions of livelihood capital positively influence farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, although the impact varies significantly. Specifically, natural capital is found to positively affect farmers’ willingness at the 5% level, indicating that richer natural capital corresponds to stronger willingness, which refutes H1-1. This finding contradicts that presented by Ochieng et al. [61]. This could be due to the small size of arable and forest land in the survey area, which results in low natural capital among farmers, which does not significantly influence conservation willingness. Furthermore, we observed that farmers with higher natural capital usually have larger agricultural operations and higher annual agricultural income, while the wildlife that causes damage in the area are predominantly small animals like monkeys and wild boars. Financial capital positively influences farmers’ willingness at the 10% level, supporting H1-2. According to Ma et al. [8], farmers incur specific economic costs when engaging in wildlife conservation efforts. Farmers with abundant financial capital can bear the economic costs of wildlife conservation, increasing their acceptance of wildlife and its conservation. Human capital positively affects farmers’ willingness at the 5% statistical level, supporting H1-3. This may be because richer human capital indicates a higher quantity and quality of family labor, which facilitates diverse livelihood strategies that reduce reliance on natural resources while enhancing risk resistance, which increases conservation willingness [62]. Additionally, human capital development enhances farmers’ knowledge and understanding of ecological protection, making them more willing to engage in wildlife conservation [63]. Social capital positively influences farmers’ willingness at the 10% level, supporting H1-4. This aligns with findings from Wang et al. [64] regarding how social capital can stimulate farmers’ participation in ecological conservation efforts. Rich social capital facilitates farmers’ access to effective information resources [65], improving their risk response [66] and understanding of conservation policies [67], which increases conservation willingness. Physical capital did not indicate a positive influence on farmers’ willingness, which refutes H1-5.

Model 1 and Model 2 represent distinct regression models in our study. Specifically, Model 1 focuses solely on livelihood capital as an independent variable, revealing a positive and significant impact on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation at the 1% level. Model 2 incorporates additional variables for a more comprehensive analysis. Among the control variables, gender negatively impacts farmers’ willingness at the 5% level, which might be because males have a lower fear of wildlife attacks compared with females [10]. Wildlife incidents negatively impact farmers’ willingness at the 1% level. As the extent of crop damage caused by wildlife increases, farmers’ incomes reduce and protection costs rise [62], which lowers their inclination to participate in conservation activities.

5.2. Robustness Test

To ensure the reliability of the regression results regarding the impact of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, we conduct a robustness test substituting the baseline regression model with an ordered logit model to examine the effect of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. As shown in Table 4, the results demonstrate significance and impact directions that are similar to those of the baseline regression results in Table 3, thereby confirming the reliability of the baseline regression results.

Table 4.

Robustness test.

5.3. Endogeneity Test

Despite controlling for relevant variables, the relationship between farmers’ livelihood capital and willingness to participate in wildlife conservation may still be influenced by unobserved omitted variables, potentially leading to biased regression results. To address possible endogeneity issues, this study references [48], selecting the distance from the village to the town government as an instrumental variable (IV). The distance from the village to the town government directly affects farmers’ livelihood capital but is not directly related to their willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, which meets the homogeneity criterion for an IV. Table 5 presents the results of the endogeneity test. The p-value for the endogeneity parameter test is 0.004, rejecting the null hypothesis that considers livelihood capital as an exogenous variable. This confirms the need for an endogeneity test. The first-stage regression results show that the regression coefficient for the distance from the village to the town government is −0.018, which is significant at the 1% level, and the F-statistic is 11.023, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 10, indicating that the IV is not a weak instrument. In the second-stage regression results, livelihood capital remains positively significant at the 1% level concerning farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, which is consistent with the baseline regression results (Table 3). Therefore, after addressing the endogeneity issue, livelihood capital still significantly enhances farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, further confirming the reliability of the baseline regression results.

Table 5.

Endogeneity test.

5.4. Analysis of Mediating Effect of Perceived Living Conditions

We employ stepwise regression to test whether perceived living conditions mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Table 6 presents the relevant results. Model 7 in Table 6 shows that livelihood capital significantly enhances farmers’ perceived living conditions at the 1% level. Model 8 demonstrates that when livelihood capital and perceived living conditions are included in the regression equation, livelihood capital significantly increases farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation at the 1% level, while perceived living conditions also significantly increase willingness at the 5% level. This suggests that perceived living conditions have a mediating effect, and livelihood capital can better stimulate farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation by enhancing their perceived living conditions.

Table 6.

Mediating effect of perceived living conditions.

Following the approach of Preacher et al. [68], we employed the bootstrap method with 1000 resampling iterations to determine confidence intervals for the indirect and direct effects of perceived living conditions. The results demonstrate significant indirect and direct effects of 0.127 and 0.555, respectively (both significant at the 1% level). The 95% confidence intervals [0.005, 0.249] for the indirect effect and [0.233, 0.878] for the direct effect exclude 0. This verifies the mediating effect of perceived living conditions in strengthening farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. Therefore, livelihood capital can enhance farmers’ perceived living conditions, which stimulates their willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, supporting H2.

5.5. Analysis of Moderating Effect of Policy Cognition

To examine whether policy cognition moderates the impact of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, this study introduces interaction terms between livelihood capital and wildlife damage compensation and ecotourism policies. Table 7 presents the relevant results. According to Model 9 in Table 7, the coefficient for the interaction term between livelihood capital and wildlife damage compensation policy is negative and insignificant, indicating that farmers’ cognition of wildlife damage compensation policy does not moderate the impact of livelihood capital on their willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. This could be attributable to insufficient policy promotion in nature reserves, resulting in most farmers being unaware of the wildlife damage compensation policy, and the low compensation standards of the policy further inhibiting the moderating effect of policy cognition on the influence of livelihood capital. This is consistent with the current state of wildlife conservation in China’s nature reserves [65].

Table 7.

Moderating effect test results of policy cognition.

Regarding wildlife damage compensation policy, this study’s conclusion that it fails to moderate farmers’ willingness is consistent with Ma et al.’s findings, which highlighted that ineffective policy dissemination and low compensation standards undermine conservation incentives [69]. Similarly, Yang et al. observed that farmers’ limited awareness of compensation policies in protected areas reduces their engagement in conservation efforts, corroborating this study’s results [70]. Conversely, the positive moderating effect of ecotourism policy cognition aligns with the broader literature. For instance, He et al. found that ecotourism policies enhance livelihood diversification and ecological awareness, increasing conservation willingness among rural communities [71]. This supports the current study’s argument that ecotourism fosters income growth and environmental stewardship. Additionally, Duan and Wen confirmed that tourism-based policies are more effective than compensation-based ones in promoting long-term conservation behavior, reinforcing this study’s distinction between policy types [5].

In contrast, Model 10 in Table 7 shows that the coefficient for the interaction term between livelihood capital and ecotourism policy is positive and significant at the 10% level. This suggests that farmers’ cognition of ecotourism policy positively moderates the impact of livelihood capital on their willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. The reason might be that ecotourism policy awareness encourages farmers to intentionally enhance livelihood capital associated with tourism, aiding their transition from traditional livelihoods to tourism-based sources, which increases their income, enhances ecological awareness [27], and boosts their willingness to protect wildlife. In summary, among different dimensions of policy cognition, only ecotourism policy is found to positively moderate the impact of livelihood capital on farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, whereas wildlife damage compensation policy is not, partially confirming H3.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Based on the empirical analysis using survey data from 186 farmers around the Jiyuan section of Taihangshan Macaque Natural Reserve, this study concludes that livelihood capital significantly enhances farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation. However, the impact varies across different dimensions of livelihood capital. Specifically, natural, financial, human, and social capital show positive effects, but physical capital has no effect. Furthermore, perceived living conditions mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and farmers’ willingness to participate, indicating that improving living conditions can enhance conservation willingness. Policy cognition, particularly regarding ecotourism policy, enhances this relationship, but wildlife damage compensation policy cognition is not significant. These findings suggest that to enhance farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation, policies should focus on continuously improving farmers’ livelihood capital. These recommendations (e.g., promoting land transfer, adjusting compensation standards, etc.) are proposed based on the study’s findings, which highlight the need to enhance livelihood capital and perceived living conditions to foster conservation participation. Additionally, improving farmers’ living conditions through ecotourism and other nonagricultural activities, and strengthening policy advocacy to increase farmers’ understanding and support of conservation policies, are crucial strategies.

This research has two academic contribution points. The first contribution is the study’s comprehensive livelihood capital framework. This study uniquely combines all five livelihood capital dimensions (natural, financial, human, social, physical) to analyze their joint influence on farmers’ wildlife conservation willingness. It highlights natural capital’s positive role (contrary to expectations due to small landholdings) and reveals how perceived living conditions mediate this relationship, linking assets to behavior through psychological pathways. Secondly, policy cognition is used as a moderator. The research distinguishes ecotourism and wildlife damage compensation policies, showing that ecotourism awareness amplifies livelihood capital’s positive effects, while compensation policies fail due to low awareness and poor standards. This dual-policy insight underscores ecotourism’s potential to harmonize economic and ecological goals.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, constrained by time and financial resources, the sample size is relatively small. This limited scale may restrict the representativeness of the findings and hinder comprehensive generalization. Future research should expand the sampling scope to obtain more robust results. Second, the analysis adheres to the conventional livelihood capital framework. Future studies could supplement and refine this framework—for instance, by incorporating health capital or psychological capital—to achieve a more nuanced assessment of farmers’ livelihood levels. Third, the study did not fully account for heterogeneity in farmers’ attitudes and willingness to participate in wildlife conservation across diverse cultural and social contexts, nor did it explore variations among farmer subgroups. Subsequent research should integrate individual differences, regional disparities, and other relevant factors to enhance the comprehensiveness of the analysis.

6.2. Policy Implications

Based on the study’s conclusions, we propose targeted policy recommendations to enhance farmers’ willingness to participate in wildlife conservation.

First, continuously increase the capital of farmers in the communities around nature reserves. The government should optimize resource allocation, expand the scale of agriculture, and consolidate the foundation of natural capital through land transfer. Adjust the compensation standards for wildlife damage and provide preferential credit to accumulate financial capital. Increasing financial subsidies for production equipment can alleviate the shortage of physical capital and enhance efficiency. Conducting non-agricultural skills training (combining online and offline) can enhance human capital, while encouraging participation in rural governance activities can cultivate social capital. In addition, by leveraging digital platforms to broaden information channels, accelerate the dissemination of knowledge, promote the accumulation of social capital, and inject impetus into the all-round development of rural areas.

Second, enhance the perception of living conditions among community residents in nature reserves through multiple channels. Traditional media such as radio, television, and outdoor billboards can be used to promote information about the protected area and ecological protection knowledge to ensure wide coverage and enable community residents to access this information at any time. Integrate new media such as social media and mobile applications to create an online interactive community to share experiences in ecological protection and foster a positive atmosphere. Regularly hold lectures, exhibitions, and practical activities, invite experts and volunteers for face-to-face exchanges, and enhance residents’ environmental awareness and participation. Plus, establish an ecological protection reward mechanism to honor and reward community residents who actively protect the natural environment, thereby further stimulating their enthusiasm and creativity. Strengthen cooperation with schools, enterprises, and other sectors of society to jointly promote the in-depth development of ecological protection publicity and education, and form a favorable situation where the whole of society participates together.

Thirdly, the government should also encourage farmers in the surrounding communities to actively participate in the construction and management of nature reserves, enhancing their sense of ownership and belonging. The government should organize farmers to participate in community planning and decision making (such as environmental improvement projects), improve their living environment, and enhance their sense of belonging through practice. Encourage farmers to supervise the maintenance of public facilities to ensure the efficient use of resources. Make use of festivals to organize cultural activities (such as handicraft exhibitions and health lectures) to enrich spiritual life, enhance cultural confidence, and promote community cohesion. This participatory governance not only enhances farmers’ positive perception of living conditions, but also injects a lasting impetus into the development of communities around nature reserves.

Author Contributions

Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, C.W.; methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing, J.H.; methodology, formal analysis, T.S.; investigation, writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; conceptualization, writing—review and editing, D.L.; funding acquisition, writing—review and editing, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Forestry and Grassland Administration under the project “Research on Major Forestry Issues: Compilation of the 15th Five-Year Plan for Forestry and Grassland Development—Development Situation and Major Target Indicators” (Project No. 500102-1788); the Key Project of the Research and Interpretation Project of Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Project No.: 2025XYZD02); The China–Africa Cooperation Research Project of China–Africa Institute (Project No. CAI-J2023-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to Article 32 of the “Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans”, jointly issued by the National Health Commission, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, life science and medical research involving human beings that uses human information data or biological samples in the following situations—without causing harm to the human body, and without involving sensitive personal information or commercial interests—can be exempt from ethical review. National Legislation Information Source: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm, accessed on 12 March 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data related to this research are not deposited in publicly available repositories but are included in this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, C.; Xie, M. Governance of nature reserves with national parks as the main body: History, challenges, and systemic optimization. Chin. Rural Econ. 2023, 5, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tian, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, T.; Cheng, J.; Su, C.; Qi, L. Scale effects of supplementary nature reserves on biodiversity conservation in China’s southern hilly region. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Rasambo, N.; Durand-Bessart, C.; Randriamalala, J.R.; Queste, J.; Becker, N.; Sarron, J.; Razafimandimby, H.; Zafitody, C.; Carrière, S.M.; et al. Strategies to engage local communities in forest biodiversity conservation had limited effectiveness in Madagascar: Lessons from the literature. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 309, 111332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tang, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, C. Planning conservation priority areas for marine mammals accounting for human impact, climate change and multidimensionality of biodiversity. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 381, 125193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Wen, Y. Impacts of protected areas on local livelihoods: Evidence of giant panda biosphere reserves in Sichuan Province, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Ping, X.; Hu, Y.; Nie, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, G. Main achievements, challenges, and recommendations of biodiversity conservation in China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2021, 36, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.E.; Evans, K.L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Shen, J.; Ding, H.; Wen, Y. Farmer protection attitudes and behavior based on protection perception perspective for protected areas. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 2137–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, Y. Wildlife accident, compensation for damage caused by wildlife and farmers’ willingness to Protect wildlife. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2023, 59, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wen, Y. Research status on conflict between human and wildlife and its experience. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 3082–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Hacker, C.E.; Cao, Y.; Cao, H.; Xue, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, H.; Zahoor, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D. Implementing a comprehensive approach to study the causes of human-bear (Ursus arctos pruinosus) conflicts in the Sanjiangyuan region, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, R. Comparison of compensation mechanism and public liability insurance system against wildlife caused injuries and losses in China. World For. Res. 2022, 35, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Shen, Y.; Tian, L. Does targeted poverty alleviation policy lead to happy life? Evidence from rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 81, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Min, Q.; He, S.; Jiao, W. Review of eco-environmental effect of farmers’ livelihood strategy transformation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 8172–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, G. How dose livelihood capital affect farmers’ pro-environment behavior? Mediating effect based on value perception. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2021, 20, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, J. The impact of livelihood capital on peasant’s willingness to participatein rural environment governance: From the dual perspectives of capital level and structure. J. Nanjing Tech Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xie, Y. Environmental income, households’ well-being and protection behavior. Shanghai J. Econ. 2022, 3, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Xie, Y. Chinese public willingness of international wildlife conservation: A case study of African elephant. Biodivers. Sci. 2021, 29, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qin, Q.; Duan, Z.; Tan, H.; Sun, Y.; Xie, L.; Feng, J.; Ma, Y. The mechanism of environmental benefits and protection costs on community farmers’ willingness to protect: Taking the Sichuan Giant Panda Nature Reserve as an example. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2023, 39, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, F.; Xue, F. Conservation attitudes, willingness, and influencing factors of community herders and residents towards Przewalski’s gazelle (Procapra przewalskii). Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S.; Cornicelli, L.; Fulton, D.C.; Landon, A.C.; McInenly, L.; Cordts, S.D. Explaining support for mandatory versus voluntary conservation actions among waterfowlers. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2021, 26, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiantiono; Sugiyo; Johnson, P.J.; Muhammad, I.L.; Fahrul, A.; Sukatmoko; William, M.; Alexandra, Z. Towards coexistence: Can people’s attitudes explain their willingness to live with Sumatran elephants in Indonesia? Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Human-elephant conflict in Xishuangbanna Prefecture, China: Distribution, diffusion, and mitigation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, 00462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L. The research of human-wildlife conflict’s current situation and the cognition of herdsmen’s attitudes in the Qinghai area of Qilian Mountain National Park. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Ren, J.; Yang, J.; Hou, Y.; Wen, Y. Human-Elephant Conflicts and Villagers’ Attitudes and Knowledge in the Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wang, Z.; He, D. From well-being to conservation: Understanding the mechanisms of community pro-environmental actions in Wuyishan national park. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 81, 126680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Song, Z.J.; Duan, W. The role of eco-tourism in ecological conservation in giant panda nature reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannelli, K.; Hampton, M.P.; Namgail, T.; Black, S.A. Community participation in ecotourism and its effect on local perceptions of snow leopard (Panthera uncia) conservation. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2019, 24, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Xing, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y. Rural residents’ acceptance of clean heating: An extended technology acceptance model considering rural residents’ livelihood capital and perception of clean heating. Energy Build. 2022, 267, 112154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Lei, H.; Ren, H. Livelihood capital, ecological cognition, and farmers’ green production behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jin, J.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, X.; Liu, D. How do livelihood capital affect farmers’ energy-saving behaviors: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ding, Y.; Ding, W.; Hou, X. Subjective life satisfaction of herdsmen from the perspective of livelihood capital: A case of Inner Mongolia. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Ouyang, C.; Xu, X.; Jia, Y. Study on farmers’ willingness to change livelihood strategies under the background of rural tourism. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, P. How do climate change perception and value cognition affect farmers’ sustainable livelihood capacity? An analysis based on an improved DFID sustainable livelihood framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2000.

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Yu, H. Conflict and coordination between protected natural areas and human activities from an institutional space perspective: A case study of the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon Nature Reserve. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, R.; He, Y. Impact of grassland compensation policy on herders’ livelihood strategy choice: A case study of Qilian and Menyuan County in Qinghai Province. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2021, 20, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Yao, J.; Hu, J.; Guo, X. Capital endowments, policy perceptions and herdsmen’s willingness to reduce livestock: A case study from the World Natural Heritage Site of Bayinbuluke. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2021, 29, 780–787. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Maddock, J.; Lu, Y. Analysis of residents’ willingness to pay to reduce air pollution to improve children’s health in community and hospital settings in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 533, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Wu, M.; Gan, C.; Chen, Y. Decision-making mechanism simulation of farmers’ land investment behavior in suburbs based on structural equation modeling-system dynamics. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Xu, Z.; Shang, H. An overview of sustainable livelihoods approach. Adv. Earth Sci. 2009, 24, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liao, N.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Su, H.; Chen, M.; Yang, C. Analysis of farmers’ sustainable livelihood in the communities of nature reserves in ethnic minority areas: A case study of Guangxi Fangcheng Golden Camellias National Nature Reserve. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, A.; Zhuang, T.; Yang, H. The impact of farmers’ livelihood capital on sense of fulfillment, happiness and security in the perspective of common wealth. World Agric. 2024, 1, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Deng, X.; Wang, X. Socioeconomic status, environmental sanitation facilities and health of rural residents. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 7, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.; Jacobs, M. Avoiding negativity bias: Towards a positive psychology of human–wildlife relationships. Ambio 2021, 50, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Zhang, B.; Cai, X.; Wang, X.; Morrison, A.M. Does the livelihood capital of rural households in national parks affect intentions to participate in conservation? A model based on an expanded theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, M.; Chen, D. Policy cognition, form of land right confirmation and peasants’ satisfaction degree with the implementation effect of land right confirmation. West Forum 2017, 27, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Agricultural Productivity: From the Perspective of Digital Transformation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiyuan Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning Bureau. The Forestry Bureau of Jiyuan Has Been Actively Working on Compensating for the Damage Caused by Wild Animals to Crops. 2024. Available online: https://zrzyghj.jiyuan.gov.cn/zwyw/sjdt/t954240.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Culture and Tourism Department of Henan Province. Jiyuan: Accelerate the Construction of a New Pattern of Cultural Tourism Development Featuring “One Core, Two Belts and Multiple Points”. 2024. Available online: https://hct.henan.gov.cn/2024/01-20/2889898.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ren, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y. The relationship between livelihood capital, multi-functional value perception of cultivated land and farmers’ willingness to land transfer: A regional observations in the period of poverty alleviation and rural revitalization. Chin. Land Sci. 2022, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Du, Y.; Zhao, M.; Xie, Y. Input Behavior of Farmer Production Factors in the Range of Asian Elephant Distribution: Survey Data from 1264 Households in Yunnan Province, China. Diversity 2023, 15, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Su, W. The impace of digital technologies on farmers’ livelihood strategy choices: Based on the regulatory effect of farmers’ psychological state. World Agric. 2022, 11, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Hu, H.; Qian, W.; Cao, M. Desire and behavior of relevant actors on the process of urbanization: A study of farmers’ migration desire in Haining, Zhejiang Province. Soc. Sci. China 2003, 5, 39–48+206. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Hu, J. A comparative analysis of the coupling and coordination between the ecological civilization construction and tourism development in different types of resource-based cities. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 79, 126563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Li, Z.; Yin, C. Response mechanism of farmers’ livelihood capital to the compensation for rural homestead withdrawal-Empirical evidence from Xuzhou City, China. Land 2022, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y. The impacts of the Asian Elephants damage on farmer’s livelihood strategies in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Psychol. Adv. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L. A comparison of moderator and mediatorand their applications. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 2, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, C.N.; Thenya, T.; Shah, P.; Odwe, G. Awareness of traditional knowledge and attitudes towards wildlife conservation among Maasai communities: The case of Enkusero Sampu Conservancy, Kajiado County in Kenya. Afr. J. Ecol. 2021, 59, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Cai, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wen, Y. Estimating the household costs of human–wildlife conflict in China’s giant panda national park. J. Nat. Conserv. 2023, 73, 126400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Chen, C.; Li, X. Village identity, relationship network, and willingness to improve rural living environment: Taking 501 farmers in Jiangxi Province as an example. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, W.; Zheng, L.; Yao, M. Multi-dimensional social capital and farmer’s willingness to participate in environmental governance. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 15, 19400829221084562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijper, T.; Urquhart, J.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Soriano, B.; Meuwissen, M.P. Exploring how social capital and learning are related to the resilience of Dutch arable farmers. Agric. Syst. 2022, 198, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Bi, Y.; Huang, B. Co-management enhances social capital and recognition of protected area: Perspectives from indigenous rangers on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savari, M.; Damaneh, H.E.; Damaneh, H.E. The effect of social capital in mitigating drought impacts and improving livability of Iranian rural households. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 89, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, W. Study on the effect of wildlife damage compensation on farmers’ willingness to sustain cultivation under the dual objective constraint of conservation and development. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 86, 126938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Su, K.; Wen, Y. The impact of tourist cognition on willing to pay for rare species conservation: Base on the questionnaire survey in protected areas of the Qinling region in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiao, W. Conservation-compatible livelihoods: An approach to rural development in protected areas of developing countries. Environ. Dev. 2024, 45, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).