Abstract

The first objective of the article is to develop a method for predicting the level of sustainability in family firms based on the dimensions of socioemotional wealth. To achieve this goal, the following machine learning algorithms were employed: Support Vector Regression (Linear Kernel), Support Vector Regression (Radial Basis Function Kernel), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR), Random Forest Regressor (RF), and Linear Regression (LR). The second objective was to determine the impact of individual socioemotional wealth dimensions on the sustainability index of family businesses. To this end, the Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) method, classified under Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), was used. The study’s results on Polish family firms revealed that the SEW dimension most strongly influencing the sustainability index is the active promotion of initiatives for the local community.

1. Introduction

Family firms, as a business governed and managed by family members intending to pursue the business’s vision and become sustainable across generations of the family [1], are the most prevalent of business organisations around the world [2,3,4,5,6]. It is translated into their significant impact on GDP creation and employment of the workforce in emerging and well-developed countries [7,8,9]. Due to the overlap of family, business, and ownership subsystems [10], family firms exhibit distinct behaviours and performance compared to non-family counterparts and can continue business even if they underperform [11,12,13].

The unique attributes of family firms, encompassing their objectives, governance, and resources, are believed to contribute significantly to these differences [14,15,16,17,18]. Scholars in family business research contend that socioemotional wealth (SEW) constitutes the principal differentiating characteristic of family-owned enterprises, and this phenomenon exists exclusively in family businesses and guides their strategic behaviours [19]. SEW encapsulates the non-financial goals [20] and affective considerations that are central to these firms, thereby offering a theoretical framework for understanding the divergent strategic behaviours and decision-making patterns observed in family firms relative to their non-family counterparts [21,22,23]. Moreover, with the prevalent scientific production, family firms often aim to preserve their socioemotional wealth [24,25,26,27]. SEW constitutes the affective capital accumulated progressively as familial involvement in the firm deepens, fostering the development of idiosyncratic learning processes and a knowledge management system [28]. The dominant focus of family firms drawn from SEW is to include achieving family unity and harmony, enhancing the family’s reputation and social status, building and maintaining a positive legacy, behaving altruistically toward family members, pursuing owners’ interests and passions, and, most importantly, maintaining control and achieving transgenerational continuity [21]. Such an approach is typical for family-owned enterprises and also exerts a positive influence on sustainable development issues [29,30]

Berrone et al. [31] found that family-controlled businesses typically engage in lower levels of environmental pollution to enhance their public image. Such environmentally conscious behaviours are commonly observed even without immediate economic benefits. Furthermore, family firms demonstrate a distinctive commitment to the well-being of their employees [32,33,34,35] and maintain strong relationships with customers, suppliers, and other external stakeholders due to their heightened sensitivity to external reputation [36]. This concern also contributes to their greater involvement in corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives [37,38,39]. Family businesses are often deeply embedded in their local communities and frequently act as sponsors for associations, charitable organisations, special events, and local sports teams [31].

The positive coincidence between family firms SEW and sustainable development was a subject of numerous research studies over the last decades (see, e.g., [23,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]). In this paper, we propose a fresh look at this relationship. Therefore, in this paper, we formulated two main objectives. The first was to develop a method for predicting the level of sustainability in family firms based on the dimensions of socioemotional wealth. Achieving this goal would also enable the verification of the following hypothesis:

H1.

Machine learning models can effectively predict the based on the socioemotional wealth of family businesses.

To achieve this objective and test the hypothesis, the following set of machine learning models was employed: Support Vector Regression (Linear Kernel), Support Vector Regression (Radial Basis Function Kernel), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR), Random Forest Regressor (RF), and Linear Regression (LR). It was assumed that a given algorithm would be considered effective in predicting the SD_score based on socioemotional wealth if it achieved an average RMSE value below 0.08, under the condition of using cross-validation during the training process. We selected this cutoff (0.08) by analogy to the commonly accepted fit indices in structural equation modelling (SEM), where an RMSEA < 0.08 is regarded as a “fair fit” (i.e., an acceptable fit) [50,51]. In the context of our task, predicting the on a [0, 1] scale, an 8% deviation represents a reasonable compromise between forecasting precision and interpretability.

The second objective was to determine the impact of individual socioemotional wealth dimensions on the sustainability index of family firms. The Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) method, classified under Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), was applied to achieve this goal. In this case, the objective is exploratory; therefore, no associated hypothesis was formulated.

Whereas prior research has predominantly employed econometric techniques—such as regression analyses (e.g., [52,53,54,55,56]), structural equation modelling (e.g., [57,58]), comparative analyses (e.g., [59,60]), or has treated SEW as a moderating construct (e.g., [61,62])—this study introduces a novel methodological approach by leveraging machine learning algorithms to disentangle and assess the predictive power of individual SEW dimensions in explaining variation in the sustainable development index. Accordingly, this study contributes to the theoretical discourse by offering insights into the applicability of machine learning techniques for conducting more nuanced and analytically robust investigations within family business research.

The literature review section outlines the theoretical foundations of socioemotional wealth dimensions and their impact on the sustainable development of family firms. The third section presents the machine learning algorithms for predicting the sustainability index (including experiments classified under XAI). The fourth section details the findings of the conducted study. The paper concludes with a summary and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socioemotional Values of Family Firms

An expanding body of literature has increasingly focused on examining the influence of non-economic factors in the strategic behaviour and performance of family firms [25,47]. In contrast to non-family enterprises, which predominantly prioritise financial outcomes in their decision-making processes, family-owned firms tend to assign substantial value to non-financial objectives, such as socioemotional considerations, legacy preservation, and family cohesion [11]. The non-financial aspects of a family firm were called socioemotional wealth and defined as non-financial goals of the family business that satisfy the family’s affective needs, such as the need for identity, influence, or dynastic succession within the firm [24].

Berrone et al. [21] proposed the multidimensional FIBER framework for the empirical operationalisation of SEW within the field of family business studies [63]. This model delineates five core dimensions of SEW: Family influence and control (F), Identification of family members with the firm (I), Binding social ties (B), Emotional attachment of family members (E), and Renewal of family bonds through intrafamily succession (R). These components collectively capture the socioemotional priorities that underpin strategic behaviour in family firms, distinguishing them from non-family enterprises in terms of governance, risk preferences, and decision-making logics [13]. FIBER dimensions were grouped into higher-order restricted SEW, including F, and extended SEW, including I, B, E, and R dimensions [64].

Debicki et al. [40] proposed three three-dimensional scale of socioemotional wealth importance that encompasses family prominence (the importance of how the community perceives the family), family continuity (the importance of preserving family influence and involvement), and family enrichment (the desire to exhibit altruism towards the family at large). Similarly, Dou et al. [65] developed three three-dimensional scales of SEW: family control of the firm, intra-family succession, and emotional attachment to the business. Authors stressed that family control is a lower-order goal that has to be achieved to meet higher-order goals, i.e., intra-family succession and emotional attachment to the business. However, propositions of Debicki et al. (2016) [40] and Dou et al. (2020) [65] did not gain wider acceptance, unlike FIBER.

It is indicated that the analysis of the SEW fosters the understanding of how non-economic objectives affect business decisions and outcomes [66,67,68].

SEW has gained much popularity [23], given that approximately 1000 published articles have now used this theoretical framework [13] and it is estimated that the term ‘SEW’ produces circa 75,000 citations in Google Schoolar [22]; there is also scholarly discourse questioning the empirical distinctiveness and measurement validity of these five dimensions [63,69]. Apart from that, there is debate related to the negative impact of SEW preservation, which includes amoral familism, distrust of outsiders [47], and the “dark side” of SEW [70], making family members more concerned with their interests than those of others, thus negatively affecting social actions [71]. Empirical evidence indicates that socioemotional wealth (SEW) operates as a dual-edged construct, functioning both as a strategic asset and a potential liability, contingent upon contextual and environmental variables [70,72]. It implies that specific dimensions of SEW may constrain firm performance—such as risk aversion or preservation of family control—while others may serve as performance enhancers by fostering trust, long-term orientation, and stakeholder loyalty [73,74].

The SEW concept was employed as theoretical foundation of various areas of family business activities, e.g., financial performance [72,75], financial wealth [54,76], risk-taking [24,77], firm valuation [78], innovativeness [58,77], internationalisation [79,80,81], R&D [53,82], leadership succession [83], business exit [11], and family firm reputation [84].

It could be assumed that socioemotional wealth (SEW) constitutes the primary reference framework guiding decision-making in family firms; its safeguarding and perpetuation must be recognised as a central determinant in shaping both the strategic logic and operational practices of these enterprises. The prioritisation of SEW influences how family firms conceptualise organisational goals, allocate resources, and navigate trade-offs between financial and non-financial objectives. From this point, family firms focus on accumulating and converting socioemotional wealth that should be passed on to the next generation [85,86].

2.2. Sustainable Development Concept

An increasingly recognised strategy for fostering intergenerational sustainability involves adopting and operationalising the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) paradigm, as articulated by Elkington [87]. This framework posits that the long-term sustainability of firms can only be realised through the balanced integration of economic performance, social responsibility, and environmental stewardship [88,89]. By aligning corporate objectives across these three dimensions, organisations can drive systemic transformations in resource management and production processes, thereby preserving the planet’s viability and equity for future generations and diverse global communities [90]. As highlighted by Kraus [91], sustainable entrepreneurship necessitates a strategic reconfiguration of entrepreneurial orientation toward achieving a balanced integration of environmental, social, and economic dimensions. It contrasts traditional entrepreneurship theories, which predominantly emphasise identifying and exploiting market-based economic opportunities. Within the sustainable entrepreneurship paradigm, key drivers of value creation—such as investment capital, innovation processes, business angel engagement, and family enterprise participation—are mobilised and exchanged among actors committed to fostering long-term, positive socio-environmental and economic outcomes [85,92,93]. Sustainable development concerns gained the interest of the European Union and the UN Member States, which was translated into the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [94,95], which assumes joint actions to “combine economic prosperity, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability” divided into 17 detailed goals.

In this context, family firms appear to be “natural” allies of sustainable development, as many of them are guided by the principle of the “intergenerational relay,” which reflects a strategic intent to transfer ownership and leadership of the business to subsequent generations of the family. This long-term orientation fosters a commitment to continuity, responsible stewardship of resources, and the pursuit of enduring value creation across generational cycles [43,96,97].

It is recognised that family firms’ maintenance of their legacy and family reputation, key components of their SEW, is tied to sustainability [30]. Antheaume et al. [92] argue that family businesses prefer longevity, which is reflected in the prioritisation of long-term rather than short-term financial goals, corresponding to the concept of sustainable development. Socioemotional wealth considerations can generate advantageous outcomes in family firms, such as enhanced employee commitment, stronger emotional bonds among stakeholders, and improved environmental performance [70]. Also, Campopiano and De Massis [98] empirically demonstrate that family-owned enterprises exhibit heightened sensitivity to business performance’s social, environmental, and economic dimensions. This responsiveness is attributed mainly to their long-term, intergenerational orientation and embeddedness within local socioeconomic contexts. In pursuit of recognition, reputational capital, and long-term continuity, family firms demonstrate a greater propensity to allocate resources toward economically viable and socially responsible initiatives that yield sustainable profitability [52]. As a result, these firms exhibit a pronounced commitment to generating positive socio-environmental and economic externalities. Such efforts are strategically aligned with preserving the reputational capital of both the enterprise and the owning family and are instrumental in ensuring the successful intergenerational transmission of a resilient and sustainable business model [99,100].

In recent years, several key studies illustrating the development of advanced ML and XAI methods in the context of sustainability metrics analysis have been published. Ong et al. proposed an Explainable NLP approach for automatically extracting and interpreting information from non-financial reports, enhancing the credibility and transparency of ESG assessments [101]. Schimanski introduced novel NLP models for evaluating corporate disclosures in ESG subdomains, highlighting improved accuracy in classifying environmental and social aspects [102]. Meanwhile, the ESGSenticNet project created a neurosymbolic knowledge base enabling precise mapping of relationships between environmental goals and actions, thus facilitating the immediate extraction of structured data from reports [103]. Additionally, the A3CG framework (Aspect–Action Analysis with Cross-Category Generalisation) was designed to resist greenwashing by linking specific actions to declared sustainability aspects [104]. Finally, Ni et al. [105] demonstrated that the hybrid tool CHATREPORT, which combines large language models with expert knowledge, enables automatic benchmarking of reports according to TCFD guidelines, significantly accelerating and standardising the assessment of climate risks [105]. These studies constitute valuable additions to the literature review, demonstrating modern predictive algorithms and advanced interpretability techniques.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Determination of the Sustainability Index

The first step of the developed method involves calculating the value of the sustainability index for each observation according to Equation (1).

where

- —sustainability index;

- —economic factors;

- —social factors;

- —environmental factors.

The partial indicators , , and are calculated using Equation (2).

where

- —the number of indicators in each group—economic, social, and environmental factors;

- —the value of individual indicators within each group of factors.

As stressed previously, the sustainable development of economic entities necessitates the balanced integration of three interdependent dimensions—environmental, economic, and social—in alignment with the Triple Bottom Line framework [87]. These dimensions should not be treated as discrete or hierarchically ordered components but must be conceptualised as a cohesive and mutually reinforcing construct [106]. Accordingly, sustainable development requires the concurrent and integrated consideration of economic viability, environmental stewardship, and social responsibility [107]. In line with this holistic perspective, we adopt an equal weighting approach for each dimension of sustainable development in our analysis.

3.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

The label in the machine learning model is the SD_score, expressed as a continuous value. This necessitates the use of machine learning models suitable for continuous targets. A selection of popular machine learning algorithms was made, including the following: Support Vector Regression (Linear Kernel), Support Vector Regression (Radial Basis Function Kernel), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR), Random Forest Regressor (RF), and Linear Regression (LR) [108].

The first regression model discussed is Support Vector Regression with a Linear Kernel (SVR-LIN). SVR-LIN is a supervised learning algorithm derived from Support Vector Machines, adapted for regression tasks. It seeks to find a linear function approximating the target variable within a margin of tolerance ε, while minimising the model’s complexity [109]. Given a training dataset , where and , the SVR problem with a Linear Kernel is formulated as (3):

subject to (4):

Here is a regularisation parameter controlling the trade-off between the flatness of the function and tolerance to deviations larger than .

Support Vector Regression with a Radial Basis Function Kernel (SVR-RBF) extends SVR-LIN by applying a nonlinear transformation via the kernel trick [110]. The RBF Kernel enables the model to capture complex, nonlinear dependencies (5):

The dual problem becomes (6):

subject to (7):

This kernelised formulation is suitable for modelling nonlinear relationships in data. The Decision Tree Regressor (DTR) predicts continuous outcomes by recursively splitting the input space using features and thresholds that minimise the loss, commonly the Mean Squared Error (MSE) [111] (8):

where is the mean value in the subset . The split is chosen to minimise the weighted average MSE across resulting partitions.

The K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR) is a nonparametric model that predicts the target value of a point based on the average of its nearest neighbours in the training set, using a distance metric, often Euclidean [112] (9):

The prediction is then given by (10):

where denotes the set of nearest neighbours of .

The Random Forest Regressor (RF) is an ensemble method that constructs a multitude of decision trees during training and outputs the average of their predictions [113] (11):

where is the number of trees in the forest and is the prediction from the -th tree. RF mitigates overfitting and increases robustness by averaging multiple uncorrelated trees.

Lastly, Linear Regression (LR) assumes a linear relationship between the features and the response variable [114]. The prediction for an input is (12):

The parameters and are estimated by minimising the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) (13):

Linear regression is widely used due to its simplicity, interpretability, and strong theoretical foundation.

The selection of regression algorithms (SVR-LIN, SVR-RBF, DTR, KNR, RF, LR) was based on the following theoretical premises:

- Linear Regression (LR)—a classical linear model with a strong statistical foundation and high interpretability, which assumes a linear relationship between features and the target and is sensitive to the influence of outliers.

- Support Vector Regression (SVR)—by employing an ε-insensitive margin and the regularisation parameter C, it allows control over the trade-off between accuracy and model complexity; the RBF-Kernel variant (SVR-RBF) enables modelling of nonlinear dependencies at the expense of greater computational cost and a higher risk of overfitting.

- Decision Tree Regressor (DTR) is a flexible model capable of capturing complex, nonlinear relationships and feature interactions, but is prone to overfitting and being unstable under small perturbations in the data.

- K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR)—a nonparametric method that is simple to implement, yet sensitive to the choice of distance metric and feature scaling; it may perform poorly in high-dimensional settings.

- Random Forest Regressor (RF)—aggregates multiple unstable decision trees, which increases resistance to overfitting and improves prediction stability, but at the cost of interpretability and longer training times.

This ensemble of algorithms enables a comparison of models with differing assumptions (linearity vs. nonlinearity, parametric vs. nonparametric, single-tree vs. ensemble) and an evaluation of the trade-offs between predictive precision and result interpretability.

3.3. XAI Experiment—Permutation Feature Importance

In recent years, the development of advanced machine learning algorithms has significantly improved prediction capabilities across domains ranging from medicine to management. Unfortunately, increased accuracy often comes at the expense of transparency, resulting in so-called “black boxes” whose internal mechanisms are difficult to comprehend. This challenge has been addressed by the field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), which aims to make the decision-making process of models more intelligible to users and decision-makers. One of the key XAI techniques for assessing the impact of input features is Permutation Feature Importance (PFI).

This method, introduced by Breiman within the framework of Random Forest [115], is based on a simple observation: if a variable is important to a model, randomly shuffling its values in the test set will degrade prediction quality. Formally, given a trained model and a feature , the following steps are taken:

- Measure the baseline value of a metric (e.g., RMSE, R2).

- Permute the values of in the test set, leaving the remaining features unchanged.

- Recalculate the performance metric.

- The difference between the metric before and after the permutation serves as a measure of the importance of .

If the permutation significantly worsens the result, it indicates that the feature was important. Values close to zero suggest little impact, while negative values indicate that the variable introduced noise. The main advantages of the PFI method typically include the following:

- Model-agnostic nature—it does not require access to the internal structure of the model, making it applicable to random forests, SVMs, neural networks, and boosting models [116];

- Transparency—it is easy to interpret the drop in prediction quality as a measure of importance;

- Stability—by repeating permutations multiple times (bootstrap or repeated permutations), one can estimate the average effect and its standard deviation.

PFI thus enables global feature ranking, which is useful for feature selection, model optimisation, and risk analysis. However, key limitations of the method include the following:

- Feature correlations—if variables are highly correlated, permuting one of them may not change the result (the information is still retained in its relevant “copies”), potentially leading to an underestimated importance score [117];

- Computational cost—for large datasets and complex models, repeated permutations are time-consuming;

- Lack of directionality—PFI indicates how important a feature is, but does not indicate whether an increase in the feature causes an increase or decrease in prediction, nor whether the relationship is linear or nonlinear. To understand the shape of the effect, it is advisable to use tools such as Partial Dependence Plots or SHAP.

Although Permutation Feature Importance evaluates each feature’s contribution independently of the others, meaning that signals arising from interactions or complex nonlinearities may be underestimated, the global importance ranking obtained via PFI on our sample with a moderate number of predictors provides a sufficiently clear depiction of the influence of individual variables on prediction quality. The results enable the unambiguous identification of those features exerting the most tremendous impact on model error, while remaining readily interpretable and reproducible in research practice. It should be noted, however, that the literature also offers more advanced methods for local interpretability, such as SHAP or Partial Dependence Plots, that could, in future studies, deepen the understanding of nonlinear dependencies and interrelationships among variables.

4. Results

4.1. Database Development and Calculation of Indicators

Primary data were gathered between May 4 and August 18 through structured data acquisition methodologies: Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) and Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI). The research sample comprised Polish privately held family enterprises, selected based on self-identification as family firms, following established methodological practices in family business research [118]. This self-categorisation approach is widely accepted for capturing the idiosyncratic nature of family-owned entities [78,119,120,121,122]. It is underpinned by the sociological principle known as Thomas’s Theorem, which posits that subjective perceptions can produce real-world consequences when treated as real [123]. Consequently, if owners perceive their enterprise as a family firm, the business is assumed to follow the behavioural norms and strategic orientations typical of such entities.

From a rigorous statistical perspective, findings derived from non-probability sampling procedures lack the epistemological foundation required for generalisation to the entire population of family enterprises [124]. Nevertheless, in the Polish context, the absence of a comprehensive sampling frame that accurately captures entities meeting various definitional criteria of a family firm renders the application of probabilistic sampling techniques unfeasible. Under such methodological constraints, using non-probability sampling, supplemented with inferential statistical analysis, remains acceptable, provided potential sampling biases are explicitly acknowledged and critically addressed [125]. This methodological stance aligns with established empirical practices in the field of family business studies and is endorsed by leading academic journals. For instance, due to analogous limitations, Madison et al. [126] employed non-probabilistic sampling techniques—relying on student-generated lists, media content analysis, and community forums. Similarly, Carr and Sequeira [127] adopted a purposive sampling strategy. The persistent challenges in the operational definition and empirical sampling of family businesses have been extensively documented in the literature [128,129]. Accordingly, this study integrates inferential statistical methods while providing comprehensive information on sample characteristics and clearly articulating the methodological limitations stemming from the non-probability sampling design.

The sample included enterprises with legal structures in the form of limited liability companies and various forms of partnerships. These legal forms ensure the segregation of family wealth from business assets, thereby delineating the financial and operational influence of the family on firm equity [122]. To construct the final research dataset, 13,696 contact attempts were initiated. Of these, 13,055 firms declined participation, and 41 withdrew during the survey completion phase. Ultimately, 600 fully completed questionnaires were initially collected, resulting in a gross response rate of 4.38%. Following data validation in the context of this research and the exclusion of incomplete or inconsistent responses, the final analytical sample comprised 204 valid cases, yielding a final response rate of 1.49%. While such a response rate raises concerns regarding potential non-response bias [130], statistical validation via t-tests comparing early and late respondents revealed no significant differences. Thus, non-response bias was deemed negligible [131].

A descriptive statistical analysis of the sample reveals considerable heterogeneity in firm age, with the most recently established enterprise being operational for 2 years, and the longest-standing entity demonstrating a firm age of 128 years. The mean firm age was calculated at 22.1 years (SD = 14.5; n = 204), indicating a moderately mature sample population.

Average employment levels per enterprise amounted to 52.6 individuals, with female employment averaging 19.2 persons per firm. Family involvement in business operations was also notable, with an average of 3.3 family members participating in firm activities, of whom 1.3, on average, were women.

From a sectoral perspective, the most significant proportion of firms operated within the service sector (n = 66; 32.4%), followed by manufacturing and industrial enterprises (n = 42; 20.6%) and commercial trade firms (n = 33; 16.2%). A subset of firms (n = 30; 14.7%) engaged in dual-sector activities encompassing trade and services. Additionally, 33 firms (16.2%) reported diversified operations across multiple sectors, including services, trade, and industry.

Regarding legal and organisational structure, most enterprises were registered as limited liability companies (LLCs), comprising 64.2% of the sample (n = 131). Partnership forms—encompassing civil, registered, and professional partnerships—accounted for 26% (n = 53). A smaller proportion were structured as joint-stock or publicly listed companies (n = 7; 3.4%). An additional 13 firms (6.4%) operated under alternative legal forms permitted by Polish commercial legislation.

4.2. Measurement Scales

The socioemotional wealth (SEW) scale employed in this study was developed by Berrone et al. [21], drawing upon foundational contributions from earlier scholarly works [78,132,133,134,135]. The scale comprises 27 indicators (see Appendix A), systematically categorised according to the distinct dimensions of the SEW construct, thereby enabling a multidimensional assessment of non-economic priorities in family firms. The scale was used directly in the studies [58,62,64,136,137,138] while some authors extracted given components to analyse, e.g., family commitment [74], innovativeness context [139], succession intention [140] or managerial capabilities [66]. It was also the subject of evaluation in several studies [22,66,69,141,142]. To validate the relevance of the scale in our study, the Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each subconstruct of FIBER. We receive results as follows: F—CR = 0.698; I—CR = 0.902; B—CR = 0.789; E—CR = 0.83; R—CR = 0.682, and all of them meet the minimum requirements recommended by Taber [143].

To assess the level of sustainable development in family enterprises, a scale measuring corporate social responsibility (CSR) was employed, based on the assumption that every organisation inherently aligns, to some extent, with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations. Following the approach of [144], it is posited that CSR and sustainable development, despite originating from distinct theoretical traditions, exhibit conceptual convergence and synergistic potential, functioning as complementary frameworks. Drawing on CSR measurement instruments previously proposed by Quazi and O’Brien [145], Maignan and Ferrell [146], Turker [147], and Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez [144], Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez [144] developed a proprietary measurement scale using structural equation modelling (SEM). This scale, which captures the implementation of the UN SDGs within corporate practice, comprises 35 indicators and was adopted for the present study. In line with its structure, the SDGs are operationalised across three key dimensions: social, economic, and environmental.

A sample of the final dataset for a selected enterprise is presented in Table 1, and detailed item descriptions are presented in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Excerpt from the database for predicting the for a sample enterprise.

4.3. Calculation of Indicators

After the database was developed, the first step was to calculate the individual indicators and, based on these, the overall sustainability index , using Equations (1) and (2). The values for each enterprise serve as the labels for the machine learning model. The goal of the developed machine learning model is to predict the of family firms based on SEW indicators. Sample calculations of the for selected records from the database are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Calculation of indicators for selected records from the database.

4.4. Implementation of Selected Machine Learning Algorithms

Given that the label () in the machine learning model is expressed as a continuous value, the following machine learning models were selected for use: Support Vector Regression (Linear Kernel), Support Vector Regression (Radial Basis Function Kernel), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), K-Neighbours Regressor (KNR), Random Forest Regressor (RF), and Linear Regression (LR).

The Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation method applied each of the indicated machine learning algorithms to the dataset. This method is used to evaluate the quality of machine learning models. It involves repeatedly splitting the dataset into training and test subsets (in this study, 10-fold cross-validation repeated five times was applied), which provides more stable and reliable performance estimates than a single data split. This procedure aims to minimise the influence of the random selection of training and test sets on the evaluation results.

For each of the analysed machine learning models, the mean values and standard deviations of three metrics were calculated: coefficient of determination (R2), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE). The obtained results for each machine learning model are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the training process of machine learning models for predicting the based on SEW indicators.

The analysis of the results indicates that the applied machine learning models are well-suited for forecasting the , thus supporting the positive verification of the first research hypothesis in the article. Support Vector Regression with a Linear Kernel (SVR-LIN) achieved the highest coefficient of determination R2 = 0.888 (± 0.061), meaning that the model explains nearly 89% of the variance in the based on the input features, and the lowest prediction errors were recorded: MAE = 0.064 (±0.008) and RMSE = 0.075 (±0.009). Both the low MAE and RMSE values, combined with the minor standard deviations of these metrics, indicate the stability and consistency of SVR-LIN predictions across different data subsets.

Linear Regression achieved the second-best RMSE result (0.076 ± 0.010), although its slightly greater variability suggests that SVR-LIN handles potential nonstationarities or minor nonlinearities in the data more effectively. Models such as Random Forest yielded a satisfactory R2, but a higher RMSE (0.088 ± 0.014), while nonlinear methods—SVR with RBF Kernel and KNN—performed slightly worse. The Decision Tree was the least stable model (RMSE = 0.132 ± 0.028).

These findings demonstrate that even a simple linear variant of SVR can capture key relationships between features and the with the highest precision. To evaluate whether this marginal improvement justifies the added complexity, we measured training times for SVR-LIN and ordinary linear regression (LR) over 1000 runs on an eight-core, 16 GB RAM workstation: LR averaged ~0.0020 s per fit, while SVR-LIN required ~0.0059 s. Although SVR-LIN trains roughly three times longer, the absolute delay of a few milliseconds is negligible in practice, especially given its enhanced tolerance to outliers (via the ε-insensitive margin) and more stable predictions under noisy conditions. Therefore, SVR-LIN was selected as the baseline model for interpretability analysis using Permutation Feature Importance (PFI), allowing us to maximise prediction accuracy while still providing precise and reliable indicators of each feature’s influence on the predicted .

4.5. Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) Analysis

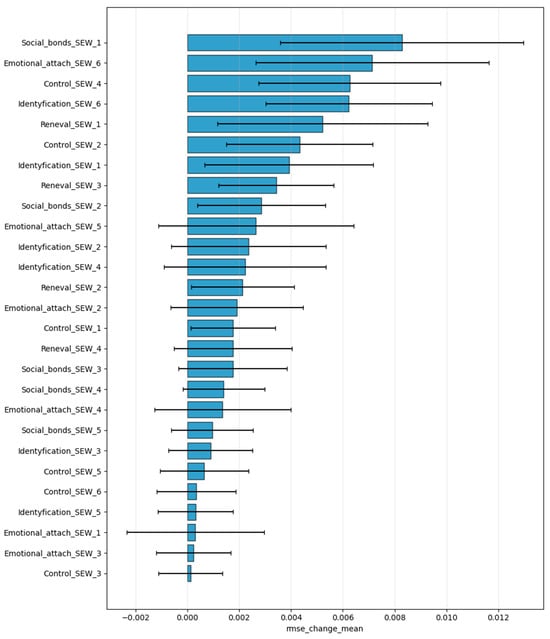

The PFI experiment was conducted using the SVR-LIN machine learning algorithm, as it achieved the lowest RMSE during the model training phase for predicting the sustainability index based on SEW dimensions. To avoid the problem of “lucky sampling,” the experiment was repeated 100 times, using 100 independent random splits of the training and test sets. For each of these 100 splits, the PFI experiment was performed 100 times for each of the 27 variables. In other words, a total of 27 × 100 × 100 = 270,000 PFI experiments were conducted. The results of the PFI experiment for all features in the sustainability index prediction model are presented in Figure 1 and Table 4.

Figure 1.

Graphical interpretation of PFI experiment results on the impact of SEW variables on the prediction of the . Source: authors’ own study.

Table 4.

PFI experiment results on the impact of SEW variables on the prediction of the SD_score (prediction error).

The Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) method proved to be an invaluable tool in our study for identifying those dimensions of socioemotional wealth (SEW) that most strongly influence the prediction of the sustainability index () of family firms. By repeating the permutations 100 times for each of the 27 SEW dimensions, we obtained stable estimates of the change in RMSE resulting from shuffling a single feature.

As a model-agnostic approach, PFI enabled us to transparently and quantitatively establish the hierarchy of feature importance using SVR with a Linear Kernel. At the same time, it is important to note that high correlations between variables may lead to underestimating individual contributions, and the computational cost of repeated permutations increases with data size. Nonetheless, applying PFI in combination with cross-validation provided reliable results that family business managers can directly use to prioritise actions to improve the .

The highest increase in prediction error was observed after permuting the indicator related to the firm’s activity in promoting social initiatives at the community level (average RMSE increase: +0.00789), confirming that social responsibility and regional engagement are the strongest drivers of sustainable development.

This is not surprising because family-controlled family firms (FCFFs) may exhibit a greater propensity to engage in socially responsible practices than non-family firms, e.g., [31,38,46,47]. Due to their deep local and familial embeddedness, family firms are uniquely positioned to enhance social inclusion [148] and mitigate socioeconomic inequalities [149]. Moreover, numerous family-owned enterprises have institutionalised corporate social responsibility within their strategic and operational models. This integration reflects an understanding that sustainable practices generate positive externalities for society and the environment and reinforce firm-level competitive advantage [150], thereby aligning business performance with broader global sustainability objectives [151].

This behaviour is partially attributable to the reputational interdependence between the business and the owning family, wherein adverse public perceptions of the firm can negatively affect the family’s socioemotional wealth [31,46,47]. Reputation assumes a pivotal role when the family name is embedded within the brand identity of a family enterprise [152]. The firm’s name serves as a concise representation of its organisational identity to internal and external stakeholders, functioning as a signalling mechanism conveying perceived quality and legitimacy. Consequently, it offers social validation and enhances the firm’s associative value in the eyes of relevant audiences [84].

Furthermore, pursuing corporate social responsibility enables FCFFs to sustain favourable stakeholder relationships [38] and enhance their organisational legitimacy by aligning with societal expectations of responsible corporate citizenship [98].

Slightly lower but still notable impacts were recorded for emotional bonds among family members (average +0.00684 RMSE). This connection can be explained based on social identity theory, originally developed within the domain of social psychology by Tajfel [153,154] and Turner [155,156], and it has been increasingly applied to organisational research to explain individual behaviour within firms [157]. The core premise of the theory posits that individuals construct their self-concept based on their membership in salient social groups [158,159]. This group-based identification leads individuals to align their attitudes and behaviours with the group’s perceived norms and prototypical attributes, a cognitive process referred to as depersonalisation [157], wherein personal identity is partially subsumed by collective identity. It suggests that the key factor for cultivating a company’s sustainable development profile is the company and its individuals pursuing the same goals [160].

However, social relationships go beyond the boundaries of a business entity due to individuals (e.g., family members) classifying themselves and others into social categories and defining themselves in relation to others [161], which situates them within that environment [162].

Ultimately, this implies that family members’ pronounced sense of identification and psychological ownership with the firm significantly influences the selection and prioritisation of strategic objectives in relation to the business and its stakeholder network [22]. Based on this background and employing elements of social identity theory, we claim that family engagement in an enterprise stimulates greater implementation of sustainable practices.

Also, a visible impact was isolated for practices related to appointing non-family managers by family representatives (+0.00621 RMSE), highlighting the importance of strong relational density and a balance between tradition and openness in management. Family firms tend to put family control and influence first. Control and influence within family firms are exerted through a combination of formal authority—such as ownership stakes and managerial roles—and informal governance mechanisms, including familial norms, values, and interpersonal relationships [163]. This is reflected by these firms directly or indirectly affecting firm management and strategic decisions by appointing board chairs, CEOs, or other senior managers based on ownership, social status, or personal charm of family members [164].

Empirical evidence suggests that family firms often limit the presence of independent directors on their boards as a strategic mechanism to preserve decision-making discretion and exert greater control over firm resources [165]. In contrast, affiliated directors are perceived as less likely to challenge family dominance, posing a reduced threat to familial control [166]. To avoid external influence—particularly from non-family shareholders—family firms tend to engage in lower levels of voluntary disclosure regarding corporate governance practices in their regulatory filings [167]. These findings support the conclusion by Cruz et al. [47] that socioemotional wealth (SEW) operates as a “double-edged sword”: while it can incentivise socially responsible behaviour, it may also foster practices that undermine widely accepted standards of corporate responsibility. Specifically, initiatives promoting equitable treatment and inclusion of family and non-family employees, or governance mechanisms designed to enhance transparency and accountability, may be perceived as threats to family control or the privileged position of family members within the organisation. Moreover, to maintain intra-family authority and strategic autonomy, family firms may exhibit lower compliance with formalised CSR standards. Adherence to such institutionalised norms could be seen as constraining the family’s ability to exercise discretion over managerial decisions and pursue long-term goals that align with their idiosyncratic priorities and values [98].

More generally, the socioemotional wealth perspective suggests that family-controlled enterprises exhibit a pronounced willingness to engage in non-economic initiatives, such as philanthropic contributions, community engagement, and corporate social responsibility, as a strategic means to safeguard their SEW endowment [55,168].

Customers’ association of the family name with the family business’s products and services sold (+0.005057 RMSE) was a subsequent sound predictor of sustainable development. It is common for family firms to incorporate the family name into the corporate brand [169,170,171], symbolically positioning the firm as an extension of the family entity and enhancing integration between the corporate reputation and the family’s reputation [152,172,173]. This brand strategy reflects a high degree of identity overlap between the family and the firm, wherein the firm’s reputation becomes inextricably linked to the family’s social standing.

Given this high degree of identity fusion and the integration of organisational and familial reputation, family members are particularly incentivised to engage in favourable social responsibility performance as a means to protect and enhance both the firm’s and the family’s public image and legitimacy [164]. Family firms that incorporate the family name into their corporate identity tend to exhibit elevated levels of corporate citizenship, more substantial alignment with customer interests, and a heightened focus on strategic priorities. This naming strategy signals a more profound commitment to stakeholder engagement and reflects a long-term orientation to sustain reputational capital and competitive advantage [174]. To some extent, the association of family name with products and services goes in line with promoting social initiatives at the community level due to the fact that family firms aim to prevent any negative perceptions or reputational damage that could harm their business operations [168]. Therefore, adopting certifications, environmental innovation efforts, integrating environmental considerations, and collaborating with stakeholders are key drivers of performance outcomes [85,175,176].

The pursuit of continuing the family legacy and tradition as a vital goal of family business also serves as a sound predictor of family firms’ sustainability development (+0.004953 RMSE). From the perspective of family owners, the firm represents more than a financial asset; it also serves as a vehicle for intergenerational continuity and the preservation of the family legacy. Consequently, family members tend to view the firm as a long-term, transgenerational investment intended to be sustained and transferred to future generations [1,21,177,178,179], reinforcing their commitment to strategic decisions that support longevity, stability, and socioemotional wealth preservation [164]. Family reputation enhances family members’ personal pride and satisfaction in being intimately tied to the business, and their emotional needs and family values can be satisfied or transferred to subsequent generations by controlling the business [169].

Hence, succession is strongly related to the sustainability issue [180,181]. For example, Stübner and Jarchow [182] confirmed that the intention to transfer the business to the next family generation is positively associated with an increased overall engagement in corporate social responsibility activities. Succession planning is crucial in supporting sustainable corporate development and enhancing organisational performance [183]. Pan et al. [184] identified a notable uptick in social outreach initiatives following succession events, attributing this trend to the successor’s strategic effort to increase their organisational legitimacy and visibility within and outside the firm.

Therefore, succession and sustainable development constitute two distinct yet interrelated domains within family business research. These issues lie at the intersection of social science—which examines the family as a fundamental societal institution—and economic science—which conceptualises the firm as a foundational unit of economic activity [185]. Together, they form a critical nexus for developing an integrated theoretical framework that informs both current inquiry and future scholarly exploration in the field.

5. Conclusions

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature connecting the concept of socioemotional wealth (SEW) with the issue of sustainability in family firms. First, the proposed method for predicting the sustainability index () based on SEW dimensions represents an innovative approach to measuring the qualitative impact of family businesses on social, economic, and environmental balance. The use of machine learning algorithms, particularly Support Vector Regression with a Linear Kernel, confirmed that simple linear models can compete with more complex techniques while maintaining interpretability and result stability. Second, applying Permutation Feature Importance as an XAI tool made it possible to complement SEW theory with an objective measure of the importance of individual dimensions, clearly indicating the crucial role of social engagement, emotional family ties, and managerial practices in generating lasting ESG benefits.

The results have direct implications for managers and owners of family firms, enabling them to allocate resources more precisely where the most significant social and environmental returns are achieved. Demonstrating that support for local initiatives and the development of strong emotional bonds within the firm significantly influence the level of sustainability provides valuable input into debates concerning CSR strategies and human resource policies. Additionally, the confirmation of the SVR-LIN model’s effectiveness in forecasting signals to practitioners that implementing machine learning tools does not necessarily require investment in advanced architectures, but can rely on more accessible and transparent solutions.

Nevertheless, the limitations of the analyses that were conducted must be acknowledged. First, the study was based on a sample of 204 Polish family businesses, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other markets or organisational cultures. Second, while the PFI method is model-agnostic and intuitive, it is susceptible to underestimating the importance of highly correlated features, which can undervalue their true significance. Furthermore, the analysis focused only on the global importance of features, without providing insights into the direction and nature of the relationships between individual SEW dimensions and , thereby limiting causal interpretation.

Future research should expand the analysis to include data from various countries to verify the universality of the model and the specific influence of SEW dimensions in different cultural contexts. It is also recommended that XAI methods aimed at local interpretability, such as SHAP or Partial Dependence Plots, be applied to explore the shape and direction of the impact of individual features. A further step could be the integration of temporal data, allowing the assessment of the dynamics of changes in response to modifications in SEW strategies, which would enable a more comprehensive understanding of adaptive processes in family firms. Moreover, future studies could evaluate machine learning techniques designed explicitly for small-sample scenarios, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. [186], to enhance model performance further when data are scarce.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.Z., M.N. and M.P.-N.; methodology, M.N. and R.Z.; software, M.N.; validation, R.Z. and M.N.; formal analysis, M.N.; investigation, R.Z. and M.N.; resources, R.Z. and M.N.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N., R.Z. and M.P.-N.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and M.N.; visualisation, M.N. and M.P.-N.; supervision, R.Z., M.N. and M.P.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data gathering was covered by the Ministry of Education and Science (Poland) within the following project: Social responsibility of science—Popularisation of science and promotion of sport, No. SONP/SN/548457/2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as The Council of the National Science Centre (not involve human subjects in the strict sense. Research focuses on legal entities—namely, family-owned businesses. The individuals who participated in the survey did so solely as representatives of their respective firms and were not themselves the direct subjects of the investigation.) by Institution Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Prof Robert Zajkowski, the Project Leader (in question), has unlimited and free-of-charge access to the dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Scales and Variables

Table A1.

Scale of socioemotional wealth.

Table A1.

Scale of socioemotional wealth.

| No. | Indicator | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control_SEW_1 | The majority of the shares in my family business are owned by family members |

| 2 | Control_SEW_2 | In my family business, family members exert control over the company’s strategic decisions |

| 3 | Control_SEW_3 | In my family business, most executive positions are occupied by family members |

| 4 | Control_SEW_4 | In my family business, nonfamily managers and directors are named by family members |

| 5 | Control_SEW_5 | The board of directors is mainly composed of family members |

| 6 | Control_SEW_6 | Preservation of family control and independence are important goals for my family business |

| 7 | Identyfication_SEW_1 | Family members have a strong sense of belonging to my family business |

| 8 | Identyfication_SEW_2 | Family members feel that the family business’s success is their own success |

| 9 | Identyfication_SEW_3 | My family business has a great deal of personal meaning for family members |

| 10 | Identyfication_SEW_4 | Being a member of the family business helps define who we are |

| 11 | Identyfication_SEW_5 | Family members are proud to tell others that we are part of the family business |

| 12 | Identyfication_SEW_6 | Customers often associate the family name with the family business’s products and services |

| 13 | Social_bonds_SEW_1 | My family business is very active in promoting social activities at the community level |

| 14 | Social_bonds_SEW_2 | In my family business, nonfamily employees are treated as part of the family |

| 15 | Social_bonds_SEW_3 | In my family business, contractual relationships are mainly based on trust and norms of reciprocity |

| 16 | Social_bonds_SEW_4 | Building strong relationships with other institutions (i.e., other companies, professional associations, government agents, etc.) is important for my family business |

| 17 | Social_bonds_SEW_5 | Contracts with suppliers are based on enduring long-term relationships in my family business |

| 18 | Emotional_attach_SEW_1 | Emotions and sentiments often affect decision-making processes in my family business |

| 19 | Emotional_attach_SEW_2 | Protecting the welfare of family members is critical to us, apart from personal contributions to the business |

| 20 | Emotional_attach_SEW_3 | In my family business, the emotional bonds between family members are very strong |

| 21 | Emotional_attach_SEW_4 | In my family business, affective considerations are often as important as economic considerations |

| 22 | Emotional_attach_SEW_5 | Strong emotional ties among family members help us maintain a positive self-concept |

| 23 | Emotional_attach_SEW_6 | In my family business, family members feel warmth for each other |

| 24 | Reneval_SEW_1 | Continuing the family legacy and tradition is an important goal for my family business |

| 25 | Reneval_SEW_2 | Family owners are less likely to evaluate their investment on a short-term basis |

| 26 | Reneval_SEW_3 | Family members would be unlikely to consider selling the family business |

| 27 | Reneval_SEW_4 | Successful business transfer to the next generation is an important goal for family members |

Source: Based on [21].

Table A2.

Scale of sustainable development.

Table A2.

Scale of sustainable development.

| No. | Indicator | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soc_SD_1 | We support the employment of people at risk of social exclusion |

| 2 | Soc_SD_2 | We value the contribution of disabled people to the business world |

| 3 | Soc_SD_3 | We are aware of the employees’ quality of life |

| 4 | Soc_SD_4 | We pay wages above the industry average |

| 5 | Soc_SD_5 | Employee compensation is related to their skills and their results |

| 6 | Soc_SD_6 | We have standards of health and safety beyond the legal minimum |

| 7 | Soc_SD_7 | We are committed to job creation (fellowships, creation of job opportunities in the firm, etc.) |

| 8 | Soc_SD_8 | We foster our employees ’ training and development |

| 9 | Soc_SD_9 | We have human resource policies aimed at facilitating the conciliation of employees’ professional and personal lives |

| 10 | Soc_SD_10 | Employees’ initiatives are taken seriously into account in management decisions |

| 11 | Soc_SD_11 | Equal opportunities exist for all employees |

| 12 | Soc_SD_12 | We participate in social projects to the community |

| 13 | Soc_SD_13 | We encourage employees to participate in volunteer activities or in collaboration with NGOs |

| 14 | Soc_SD_14 | We have dynamic mechanisms of dialogue with employees |

| 15 | Soc_SD_15 | We are aware of the importance of pension plans for employees |

| 16 | Econ_SD_1 | We take particular care to offer high-quality products and/or services to our customers |

| 17 | Econ_SD_2 | Our products and/or services satisfy national and international quality standards |

| 18 | Econ_SD_3 | We are characterized as having the best quality-to-price ratio |

| 19 | Econ_SD_4 | The guarantee of our products and/or services is broader than the market average |

| 20 | Econ_SD_5 | We provide our customers with accurate and complete information about our products and/or services |

| 21 | Econ_SD_6 | Respect for consumer rights is a management priority |

| 22 | Econ_SD_7 | We strive to enhance stable relationships of collaboration and mutual benefit with our suppliers |

| 23 | Econ_SD_8 | We understand the importance of incorporating responsible purchasing (i.e., we prefer responsible suppliers) |

| 24 | Econ_SD_9 | We foster business relationships with companies in this region |

| 25 | Econ_SD_10 | We have effective procedures for handling complaints |

| 26 | Econ_SD_11 | Our economic management is worthy of regional or national public support |

| 27 | Env_SD_1 | We are able to minimize our environmental impact |

| 28 | Env_SD_2 | We use consumables, goods to process, and/or processed goods of low environmental impact |

| 29 | Env_SD_3 | We take energy savings into account in order to improve our levels of efficiency |

| 30 | Env_SD_4 | We attach high value to the introduction of alternative sources of energy |

| 31 | Env_SD_5 | We participate in activities related to the protection and enhancement of our natural environment |

| 32 | Env_SD_6 | We are aware of the relevance of firms planning their investments to reduce the environmental impact that they generate |

| 33 | Env_SD_7 | We are in favour of reductions in gas emissions and in the production of wastes and in favour of recycling materials |

| 34 | Env_SD_8 | We have a positive predisposition to the use, purchase, or production of environmentally friendly goods |

| 35 | Env_SD_9 | We value the use of recyclable containers and packaging |

Source: Based on [144].

References

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Pramodita Sharma Trends and Directions in the Development of a Strategic Management Theory of the Family Firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.; Yeung, B. Agency Problems in Large Family Business Groups. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Memili, E.; Chrisman, J.J.; Welsh, D.H.B. Family Firms’ Professionalization: Institutional Theory and Resource-Based View Perspectives. Small Bus. Inst. J. 2012, 8, 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H.; Chrisman, J.J.; De Massis, A. The impact of small- and medium-sized family firms on economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R.; Trujillo, M.-A.; Guzmán, A. Governance of Family Firms. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 7, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R. Family Control of Firms and Industries. Financ. Manag. 2010, 39, 863–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. European Family Business Trends. Eur. Fam. Bus. Trends 2015, 1, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gersick, K.E.; McCollom, H.M.; Lansberg, I. Generation to Generation Life Cycles of the Family Business; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F.; Gómez-Mejia, L.R.; Hellerstedt, K.; Withers, M.; Nordqvist, M. To merge, sell or liquidate? Socioemotional wealth, family control, and the choice of business exit. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1342–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.R.; Meglio, O.; Gomez-Mejia, L.; Bauer, F.; De Massis, A. Family Business Restructuring: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 59, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Mendoza-Lopez, A.; Cruz, C.; Duran, P.; Aguinis, H. Socioemotional wealth in volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous contexts: The case of family firms in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2024, 15, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Chrisman, J.J.; Kano, L. Family-owned multinational enterprises in the post-pandemic global economy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2022, 53, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Duran, P.; Gómez-Mejía, L.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J. Socioemotional wealth and family firm performance: A meta-analytic integration. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2023, 14, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Perlines, F.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Millan-Toledo, C.; Ibarra Cisneros, M.A. Socioemotional wealth: A systematic literature review from a family business perspective. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 29, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerlander, N. Family business and business family questions in the 21 st century: Who develops SEW, how do family members create value, and who belongs to the family ? J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2022, 13, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiecek-Janka, E.; Nowak, M.; Borowiec, A. Application of the GDM model in the diagnosis of crises in family businesses. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2019, 9, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Mubarik, M.S. Where socioemotional wealth (SEW) stands today? Review Into The Past, Present and the Future. J. Tianjin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 54, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, R.V.; Alexander, B.N.; Debicki, B.J.; Zajkowski, R. Untangling non-economic objectives in family & non-family SMEs: A goal systems approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, L.; Nordqvist, M.; Chirico, F.; Gómez-mejia, L.; Ashforth, E.; Swartz, R.; Melin, L. From “FIBER” to “FIRE”: Construct validation and refinement of the socioemotional wealth scale in family firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2024, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaji, H.; Ahmad, N. Future perspective of socioemotional wealth (SEW) in family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2023, 13, 923–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; de Castro, J. The Bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 653–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Holt, D.T. Beyond socioemotional wealth: Taking another step toward a theory of the family firm. Manag. Res. 2016, 14, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.T.; Pearson, A.W.; Payne, G.T.; Sharma, P. Family Business Research as a Boundary-Spanning Platform. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Covin, J.G.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E. Entrepreneurial orientation, concern for socioemotional wealth preservation, and family firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuelli, A.; Carungu, J.; Lattanzi, N. Drivers and nuances of sustainable development goals: Transcending corporate social responsibility in family firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimer, K.; Abughazaleh, N.; Tahat, Y.; Hossain, M. Family Business, ESG, and Firm Age in the GCC Corporations: Building on the Socioemotional Wealth (SEW) Model. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Buckley, J. ‘What’s so special about family business?’ An exploratory study of UK and Irish consumer experiences of family businesses. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, E.J.; Upton, N.; Seaman, S.L. A comparative analysis of strategic marketing practices of high-growth US family and non-family firms. J. Dev. Entrep. 2003, 8, 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Salem, A.; Mesquita, L.F.; Hashimoto, M.; Hom, P.W.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Family firms are indeed better places to work than non-family firms! Socioemotional wealth and employees’ perceived organizational caring. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2021, 12, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Gomez, L.; Geoff, M.; Martin, G. Family Firms and Employee Pension Underfunding: Good Corporate Citizens or Unethical Opportunists? J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 192, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micelotta, E.R.; Raynard, M. Concealing or revealing the family?: Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2011, 24, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Dibrell, C. The Natural Environment, Innovation, and Firm Performance: A Comparative Study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.W.; Whetten, D.A. Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S & P 500. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.G.; Jaskiewicz, P.; Ravi, R.; Walls, J.L. More Bang for Their Buck: Why (and When) Family Firms Better Leverage Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 575–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debicki, B.J.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Chrisman, J.J.; Pearson, A.W.; Spencer, B.A. Development of a socioemotional wealth importance (SEWi) scale for family firm research. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondi, E.; De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. Unlocking innovation potential: A typology of family business innovation postures and the critical role of the family system. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firfiray, S.; Cruz, C.; Neacsu, I.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Is nepotism so bad for family firms? A socioemotional wealth approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 28, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Why do some family businesses out-compete? Governance, long-term orientations, and sustainable capability. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A. Goal Setting in Family Firms: Goal Diversity, Social Interactions, and Collective Commitment to Family-Centered Goals. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1263–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, E.H.O.; Rutherford, M.W.; Pollack, J.M. Examining the Relation Between Ethical Focus and Financial Performance in Family Firms: An Exploratory Study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2010, 23, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Μejia, L.R. Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family–controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are Family Firms Really More Socially Responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Neacsu, I.; Martin, G. CEO Risk-Taking and Socioemotional Wealth: The Behavioral Agency Model, Family Control, and CEO Option Wealth. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J.; Miroshnychenko, I.; Wiseman, R.M.; Muñoz-Bullón, F.; Massis, A. De Family Control, Political Risk and Employment Security: A Cross National Study. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 61, 2338–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Curran, P.J.; Bollen, K.A.; Kirby, J.; Paxton, P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 2008, 36, 462–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Amankwah-amoah, J.; Danso, A.; Konadu, R.; Owusu-agyei, S. Environmental sustainability orientation and performance of family and nonfamily firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Chrisman, J.J. Risk abatement as a strategy for R&D investments in family firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, J.; Signori, A.; De Massis, A.; Vismara, S. Financial Wealth, Socioemotional Wealth and IPO Underpricing in Family Firms: A Two-Stage Gamble Model. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1073–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. How Does Family Involvement Affect Environmental Innovation ? A Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, C.; Calabrò, A.; Valentino, A.; Torchia, M. Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of CEO Tenure and Millennial CEO. Br. J. Manag. 2024, 35, 2103–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J.; Voordeckers, W.; Steijvers, T.; Laveren, E. The entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship in private family firms: The moderating role of socioemotional wealth. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filser, M.; De Massis, A.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S. Tracing the Roots of Innovativeness in Family SMEs: The Effect of Family Functionality and Socioemotional Wealth. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukalska, E.; Zinecker, M.; Pietrzak, M.B. Socioemotional Wealth (SEW) of Family Firms and CEO Behavioral Biases in the Implementation of Sustainable. Energies 2021, 14, 7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.; Quinn, M.; Moreno, A. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: A longitudinal content analysis of corporate disclosures. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; Kellermanns, F.W.; López-Fernández, M.C.; Sarkar, S. The effect of socioemotional wealth on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and family business performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2019; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasio, V.; Rosso, J.; Alejandro, S. Entrepreneurial orientation and socioemotional wealth as enablers of the impact of digital transformation in family firms. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2024, 14, 1268–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Herrero, I. Back to square one: The measurement of Socioemotional Wealth (SEW). J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2022, 14, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffranchini, G.; Hadjimarcou, J.S.; Kim, S.H. The Impact of Socioemotional Wealth on Decline-Stemming Strategies of Family Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Wang, N.; Su, E.; Fang, H.; Memili, E. Goal complexity in family firm diversification: Evidence from China. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2020, 11, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.Y.; Dayan, M.; Di Benedetto, A. Performance in family firm: Influences of socioemotional wealth and managerial capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firfiray, S.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Gomez-Mejia, L. The Labor Productivity of Family Firms: A Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Productivity Analysis; Grifell-Tatjé, E., Knox Lovell, C.A., Sickles, R.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 387–410. [Google Scholar]

- Palalić, R.; Smajić, H. Socioemotional wealth (SEW) as the driver of business performance in family businesses in Bosnia and Herzegovina: The mediating role of transformational leadership. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2022, 12, 1043–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, M.; Hülsbeck, M.; Ostermann, T.; Hack, A. Validating the FIBER scale to measure family firm heterogeneity—A replication study with extensions. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2022, 13, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Zellweger, T.M. Extending the Socioemotional Wealth Perspective: A Look at the Dark Side. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.; Yeung, B. Family Control and the Rent-Seeking Society. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, L.; Cennamo, C.; Guido, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L. Preserving Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Asset or Liability? The Moderating Role of Business Context. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1341–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Deconstructing socioemotional wealth. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzak, M.R.; Jassem, S. Socioemotional wealth and performance in private family firms. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2019, 9, 468–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Justo, R.; De Castro, J.O. Does family employment enhance MSEs performance?: Integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Patel, P.C.; Zellweger, T.M. In the horns of the dilemma: Socioemotional wealth, financial wealth, and acquisitions in family firms. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1369–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiczy, N.D.; Hack, A.; Kellermanns, F.W. What makes a family firm innovative? CEO risk-taking propensity and the organizational context of family firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]