Abstract

The rapid rebound of global tourism post-pandemic has intensified pressure on destinations like Istanbul and Athens, bringing overtourism debates into sharp focus. This study examined how five sustainability dimensions (economic, environmental, sociocultural, political, technological) shape residents’ overtourism perceptions and tourism support. Using PLS-SEM analysis of 285 long-term residents’ responses, this study reveals contrasting patterns between cities. In Athens, heightened awareness of environmental, economic, and sociocultural sustainability directly increases overtourism perceptions, subsequently reducing tourism support. Istanbul presents a counterpoint: environmental sustainability concerns alleviate overtourism perceptions, though without significant impact on tourism backing. Notably, political and technological dimensions show no statistically significant effects in either context. These findings demonstrate how sustainability perceptions are locally mediated, with identical factors producing divergent outcomes across cultural contexts. The study advances sustainable tourism literature by: (1) empirically validating context-dependent variations in resident attitudes, and (2) proposing a community-centered evaluation framework for policymakers. Recent study emphasizes the necessity of destination-specific strategies that prioritize residents’ nuanced sustainability concerns over generic tourism management approaches.

1. Introduction

Global travel has nearly reached its pre-pandemic level. Over 300 million individuals traveled overseas in the first quarter of 2025 according to UN Tourism projections, which is roughly 5% more than in the same period in 2024 [1]. However, the numerical rebound has revived familiar urban strains: crowded streets, overburdened public services, housing shortages, cultural displacement, and harm to local ecosystems [2,3].

Europe illustrates both the scale and the uneven geography of recovery. Roughly 756 million international arrivals were recorded across the continent in 2024 [4], topping the previous record. France (100 million), Spain (85 million), and Italy (57 million) still receive the most visitors, yet the sharpest growth is in southern and southeastern Europe, Türkiye’s arrivals having risen 247% between 2020 and 2023 to reach 55 million, while Greece logged a 344% leap from 7.4 million to 32.7 million [4]. Headlines reflect the tension: Venice has made its EUR 5 day ticket permanent [5]; Barcelona residents have protested crowds with water pistols, and Athens now limits the Acropolis to 20,000 visitors a day.

Istanbul and Athens have become new focal points of overtourism in the eastern Mediterranean. Official statistics confirm pronounced seasonality: at Athens International Airport, only 5.2 million passengers were handled in the first quarter of 2024, yet 3.61 million arrived in July and 31.85 million over the full year [6,7]. Istanbul showed a similar pattern: 10.47 million foreign visitors in January–July 2024, of whom 1.9 million came in July [8]. On the other hand, pre-COVID-19 benchmarks underline the rebound: Istanbul received 14.9 million foreign visitors in 2019, and Athens International Airport handled 25.6 million passengers the same year. By 2024, these figures had climbed to 20.0 million and 31.9 million, respectively, surpassing their 2019 levels by roughly one-third [8,9]. Both cities are seeing crowded buses and metros, rents driven up by short-term lets, and faster wear on historic sites. Rapid growth risks outpacing the very systems that keep daily life running. Overtourism is therefore now viewed as a threat to economic stability, social cohesion, environmental quality, governance capacity, and technological infrastructure [10,11]. Resident pushbacks in Venice, Barcelona, and Amsterdam have already spurred calls for urgent action [12].

Since the Brundtland Report (1987), sustainability in tourism has usually been based on three pillars—economic, sociocultural, and environmental—popularly known as the 3P framework (profit, people, planet) [13,14]. Recent research argues that political and technological factors must be added to build a fuller picture [15,16]. Empirical studies that put residents at the center, especially on these two newer dimensions, remain scarce [15,17], and political and technological issues have yet to be fully incorporated into holistic models [11].

These discussions align with the broader framework of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [18,19]. Tourism already appears in SDG 8.9 (sustainable jobs and local culture) and SDG 12.b (impact tracking), yet the five-dimensional model used here connects with other goals as well: economic (SDG 8), environmental (SDGs 12 and 13), sociocultural (SDG 11), political (SDG 16), and technological (SDG 9). Looking at how people in Athens and Istanbul view these dimensions offers practical city-level insights to close local SDG gaps before 2030.

Among tourism’s four main stakeholder groups—tourists, businesses, public authorities, and residents—residents feel visitor pressure most directly. Earlier work has stressed tourist dissatisfaction with crowding, [20] firms’ trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability [16], and government regulation [12]. Although numerous studies have explored residents’ sustainability perceptions for individual pillars—economic, sociocultural, environmental, political, and technological—the simultaneous integration of all five dimensions into a single resident-focused framework remains limited [21,22].

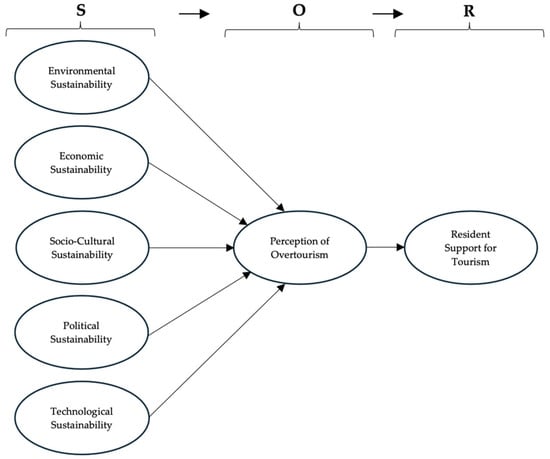

Therefore, this research set three goals: to examine how overtourism shapes resident perceptions in all five sustainability dimensions; to test how these perceptions relate to resident support for tourism (RST); and to compare Istanbul and Athens to explain how their differing cultural and governance contexts influence the perception–support link. We applied the well-known stimulus–organism–response (S–O–R) model: five external stimuli—environmental, economic, sociocultural, political, and technological—are expected to shape the organism, defined here as residents’ perception of overtourism, which in turn drives the response, namely RST.

By extending sustainability analysis beyond the classical 3P framework and placing residents at the center, this research sought to obtain a clearer, context-sensitive view of overtourism in two fast-changing [23,24] Mediterranean cities such that the findings may guide more balanced policies that safeguard urban life while preserving tourism’s economic benefits.

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Understanding Overtourism

Overtourism does not present itself in a uniform way [25]. Its effects often depend on where it occurs and under what conditions. In some cities, it appears in the form of overcrowded streets or environmental degradation. In others, it brings more subtle changes, such as shifts in local identity or disruptions to everyday routines. The term “overtourism” has only recently gained clearer academic definition. A bibliometric review indicates that the phenomenon is highly place-specific, influenced by factors such as infrastructure, governance, and social context [26].

Still, the term is not without problems. One study argues that using the term “overtourism” too loosely may obscure underlying structural issues such as gentrification, rising housing costs, and inadequate public services. Based on comparative research in thirteen European cities, the authors suggest using the term “visitor pressure” to more accurately describe the strain tourism places on shared urban resources. Their analysis also highlights how simplified narratives on overtourism can hinder the development of effective policy responses [15].

Importantly, overtourism is not just about the number of tourists. The issue is often identified when there is a mismatch between tourist flows and a destination’s ecological, social, or perceptual capacity [27,28]. Disruptions occur when tourism begins to interfere with daily life or weakens local attachment to place. A range of case studies support this interpretation. In Bali, it has been reported that perceived crowding often occurs before actual physical saturation is reached [29]. That research showed that psychological thresholds may serve as early indicators of overtourism. Together, these findings point to the need for metrics that incorporate perception and lived experience alongside physical data.

Wider systemic factors have amplified these trends [30,31]. The proliferation of budget airlines, short-term rental platforms, and algorithmic promotion systems has intensified the flow of visitors. In one study, it is argued that urban landscapes have been transformed by such mechanisms—blurring distinctions between resident and tourist, public and commercial, and domestic and commodified [32] Even smaller towns with heritage protections are not exempt from these pressures. Visitor-to-resident ratios exceeding 1:700 have been documented in Èze et al. [33]. In such cases, preserving visual authenticity does not necessarily ensure the sustainability of community life, as infrastructure strain, demographic shifts, and spatial fragmentation often follow.

Policy responses have been limited in scope and effectiveness. This has been attributed to fragmented governance, dependence on tourism-based revenue, and political inertia [34]. For example, in cities like Venice and Dubrovnik, cruise ship saturation and housing commodification have displaced residents and degraded urban environments [35].

This pattern is not confined to Europe. In Sri Lanka, projections suggest that popular sites such as Yala National Park and Sigiriya may face ecological collapse by 2027 if no regulatory action is taken [36]. Similarly, a 70% increase in post-pandemic tourism—largely driven by social media—has been observed in Banyumas Regency, Indonesia, leading to infrastructural and ecological strain within a short period [37].

Quantitative research supports the persistence of overtourism. A longitudinal study of 28 European cities between 2014 and 2023 identified recurring stress markers such as high rates of overnight stays and increased inbound air traffic [38]. The findings confirmed that overtourism dynamics quickly reemerged following the COVID-19 disruption, highlighting the structural and self-reinforcing nature of the phenomenon.

2.2. Sustainability in Tourism

The conventional sustainability framework in tourism research is built upon three dimensions: economic, sociocultural, and environmental. While this 3D model has been widely adopted as a baseline, recent studies increasingly argue that it no longer captures the complexity of modern tourism systems. In particular, technological and political factors have emerged as critical influences on tourism dynamics, prompting calls to expand the framework to a five-dimensional (5D) model.

Recent contributions emphasize the role of technological tools in enhancing tourism governance. For instance, Wijayawardhana [36] demonstrated that machine learning techniques can anticipate high-pressure zones in tourist destinations, providing an opportunity for proactive intervention. Similarly, Antonio and Alamsyah [29] integrated sentiment analysis with spatial modeling to support decentralized, real-time responses to tourism congestion. These approaches highlight how digital systems can inform more responsive planning processes. Changes in institutional practices reflect the broader shift in sustainability thinking. Destination management organizations (DMOs) in Europe are no longer limited to promotional functions: their roles increasingly include managing tourist flows, safeguarding resident interests, and supporting long-term, data-informed strategies [39]. Affordable wireless monitoring technologies have been identified as tools that can assist these efforts by enabling local authorities to monitor crowding in real time without compromising privacy [40]. Additional methods have also been proposed. An overtourism index has been developed that integrates governance indicators with digital infrastructure data [28], while other work has explored how sensory marketing—via spatial design or multisensory cues—may help redirect tourist movement [41]. These approaches suggest that behavioral nudges, rather than enforcement alone, could play an effective role in managing visitor density.

Despite advancements, technology alone does not address all underlying issues. Some studies caution that without addressing the deeper policy structures driving overtourism—particularly those centered on growth and economic dependence—technological solutions may remain superficial [42]. From this perspective, sustainability requires not only improved tools but also a fundamental rethinking of tourism’s role and purpose. Others advocate for approaches that integrate digital tools with local participation, emphasizing spatial dispersion, adaptive governance, continuous monitoring, and a strong commitment to community priorities and long-term stability [35].

Examples at the local level offer further clarity. In Darjeeling, homestay tourism has been described as following four guiding principles: reduce, reuse, recycle, and regulate [43]. This approach helps alleviate pressure on formal infrastructure while generating local income, illustrating how grassroots solutions can complement broader policy frameworks.

That said, consistency across sustainability areas remains uneven. Analyses based on coupling–coordination models show that while some environmental and social goals align, links to infrastructure or economic planning are often weak. This suggests that even as the 5D model expands sustainability thinking, its real-world impact will depend on governance capacity and the ability to integrate across sectors.

2.3. Residents’ Perception and Support

Residents’ perceptions play a central role in determining the long-term sustainability of tourism, yet many analytical models tend to present these perceptions as straightforward reflections of economic gain or loss. However, one study challenges this view, suggesting that local attitudes are shaped by emotional responses, sociotechnical changes, and broader structural forces, and that perceptions reflect how tourism is interpreted and experienced over time [44].

This complexity is evident in several high-traffic destinations. For example, a gap has been identified between what tourists value—such as ease of transport and access to iconic landmarks—and what residents prioritize, including affordable housing and support for small businesses [45]. The disconnect suggests that tourism policy often favors visitor convenience over community needs. Moreover, emotional well-being also shapes how tourism is received [46]. In Germany’s Allgäu region, Steber and Mayer [47] note that proximity tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted local routines and had a negative effect on residents’ overall life satisfaction. Residents responded with behavioral adjustments such as spatial avoidance, but also expressed dissatisfaction with governance structures that failed to regulate influxes. In some cases, cultural boundaries become central to resident–tourist dynamics. In Mexico, it has been reported that while local communities express pride in their cultural traditions during the Day of the Dead, discomfort emerges when sacred spaces are disrespected by visitors [48]. The decision to hold a second, more private celebration reflects a form of symbolic defense and emotional resilience.

However, not all responses are negative. In the Cameron Highlands in Malaysia, tourism has been associated with perceived benefits, such as increased employment and improved services, although concerns about ecological degradation remain [49]. Similarly, sentiment analysis conducted in high-density tourism zones has identified overlapping emotional responses, including appreciation of economic opportunities alongside frustration over cultural displacement [28].

These findings suggest that perception-based metrics offer important insights for planning and policy. When local sentiments are treated not as secondary to economic or environmental indicators, but as equally vital, tourism governance becomes more adaptive. Therefore, resident responses—whether supportive, ambivalent, or resistant—must be understood not only as reactions to visitor presence but also as reflections of broader questions of inclusion, identity, and control over space.

2.4. Theoretical Framework: Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR)

The stimulus–organism–response (S–O–R) framework, originally developed in environmental psychology, offers a useful framework for examining how tourism-related stressors influence human behavior. Specifically, it suggests that external pressures—like crowding or environmental degradation—are filtered through individual or collective psychological responses, which then lead to specific actions or attitudes.

In this study, the S–O–R framework [50] was adopted to explore how residents’ perceptions of sustainability in its five dimensions, prompted by tourism development, influence support for tourism in the context of overtourism. This framework argues that external stimuli activate internal processes—conscious and unconscious—such that individuals experience and perceive stimuli and thus are moved to act. It has been widely used in disciplines such as consumer behavior, organizational culture, and leadership studies [51].

This sequential mechanism of stimuli (S) provoking internal emotional and cognitive responses in an organism (O), resulting in internal states that lead to behavioral responses (Rs), has been instrumental in tourism research. For instance, in the Cameron Highlands, rising tourist numbers have been linked to ecological strain and changes in social cohesion. Residents have been observed adjusting their behaviors to maintain a sense of balance in daily life—an example corresponding to the organism stage of the S–O–R framework [49].

Furthermore, perceptions and emotions mediate how external stimuli are interpreted. Resident responses are shaped not only by physical changes in the environment but also by how those changes are perceived and experienced emotionally [27]. While that study did not explicitly reference the S–O–R model, its findings are consistent with the model’s core assumptions.

Beyond the individual level, the S–O–R framework has also been applied to community and institutional responses. In rural Germany, local communities have exhibited both avoidance behaviors and civic engagement in response to pandemic-related tourism [47]. Similarly, urban gardens in Tokyo introduced interventions such as visitor flow adjustments as adaptive responses to tourism pressure [52]. These actions can be understood as organismic responses. A predictive perspective has been demonstrated through the use of graph-based forecasting to detect early stress signals [53]. Although computational in nature, this model reflects the logic of the S–O–R framework by identifying inputs, processing them through dynamic systems, and anticipating the resulting responses.

This study advances the S–O–R model by treating the five domains of sustainability (environmental, economic, sociocultural, political, and technological) as distinct stimuli that influence how residents perceive overtourism (organism). These perceptions then shape resident support for tourism (response). Thus, “stimulus” refers to the sustainability dimensions, “organism” refers to residents’ psychological responses—cognitive (e.g., perceived risk, loss of control) and emotional (e.g., exhaustion, discomfort)—and “response” reflects behavioral intentions regarding tourism. The model is supported by studies such as Erul and Woosnam [54], which found that emotional support and perceived control explained a substantial portion of support for tourism.

This framework captures the complexity of how overtourism is experienced and acted upon and offers a valuable basis for understanding resident behavior in rapidly changing urban tourism contexts.

2.5. Comparative Urban Contexts: Relevance of Istanbul and Athens as Contrasting Case Studies

Although overtourism has been extensively studied in Western European cities like Venice and Barcelona [27], comparative research across less centralized or non-Western urban contexts remains limited. In this regard, Athens and Istanbul offer compelling bases for analysis. Although Athens and Istanbul are geographically close, they differ markedly in how their urban spaces are structured and governed. As Bouchon and Rauscher [32] note, overtourism is not simply a function of visitor numbers. The way cities are designed, managed, and represented in tourism discourse all influence how they absorb or resist tourism-related pressures.

Emotional strain can also emerge at the neighborhood level, as shown through sentiment-based analysis that indicates that sociocultural tensions may persist even when visitor numbers remain stable [28]. Similarly, a comparative study of eleven historic cities highlights that densely built heritage areas are subject to particularly high levels of stress due to their physical limitations and symbolic prominence within tourism narratives, making them especially vulnerable [55].

Athens and Istanbul reflect these dynamics in distinct ways. Both cities are under significant tourism pressure, but their governance models differ. Athens relies on a centralized heritage management approach, while Istanbul operates within a more fragmented, multilayered system. These differences shape how each city handles tourist flows and formulates responses to overtourism.

Predictive tools may offer support where administrative structures vary. Wijayawardhana [36] introduced a forecasting method based on political and economic indicators that can anticipate spikes in tourism demand. Though the model was not developed for a specific city, it could be adapted to suit the contexts of both Athens and Istanbul, allowing local decision-makers to respond more proactively. Crete, on the other hand, presents a different scenario. According to Vourdoubas [56] the island has extremely high tourism density, particularly along its northern coast. Unlike Athens and Istanbul, which benefit from spatial and institutional diversity, Crete depends heavily on a narrow tourism economy. This combination of concentrated pressure and limited flexibility increases its exposure to environmental and infrastructural strain.

In parallel, governance responses to overtourism are increasingly shaped at the supranational level. Peloponnisios [57] notes that the European Commission has begun to act as a policy entrepreneur: framing overtourism within broader sustainability goals and promoting coordination through digital and environmental regulatory instruments.

2.6. Hypothesis Development

2.6.1. Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability refers to the extent to which tourism activities are perceived to align with environmental protection efforts, such as conserving natural resources and managing waste. Residents’ perceptions of overtourism are influenced by how well tourism is seen to align with these efforts. When tourism is viewed as environmentally responsible, it is more likely that overtourism will be perceived less negatively. Residents have been found to primarily attribute overtourism to environmental degradation caused by excessive tourist presence [58]. Environmental stress has likewise been highlighted as a primary concern in the overtourism literature [4]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1.

Perceived environmental sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.2. Economic Sustainability

Economic sustainability in tourism refers to the extent to which tourism activities foster the local economy by creating jobs, enhancing infrastructure, and maintaining price stability. Residents are essential in promoting sustainable tourism, serving as cultural ambassadors and the primary community through which tourism is experienced [59]. They play a critical role in the tourism sector, as their perceptions shape tourism’s sustainability outlook. Their support is essential for the success and long-term sustainability of any tourism development [60,61]. When tourism contributes directly to the local economy, creates jobs, and enhances infrastructure without causing inflation, residents generally perceive tourism more favorably, considering economic benefits closely associated with favorable views on tourism, according to empirical research [62]. A plethora of studies verify the favorable attitudes towards additional tourism development being interlinked to personal and perceived benefits of tourism [62,63,64,65,66,67]. It has been evident there is a negative correlation of residents’ perceptions of overtourism in Brazilian coastal destinations with the economic benefits and quality of public services [68]. This stands as a testament to the evident positive benefits of employment by investment and consumption in the tourism sector [69]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2.

Perceived economic sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.3. Sociocultural Sustainability

Mitigation of overtourism resentment can be achieved through tourism that promotes local culture preservation, mutual understanding, and the avoidance of cultural commodification. It has been evident that a community’s contentment with tourism growth is determined by the way in which residents view the economic, environmental, and sociocultural advantages [70]. Residents exhibit a more favorable response to tourism when it is in harmony with and bolsters local cultural identity [71]. Caro-Carretero and Monroy-Rodríguez [72] discovered that residents appreciated the contribution of tourism to cultural preservation, yet emphasized the necessity of balancing development with the needs of the community. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3.

Perceived sociocultural sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.4. Political Sustainability

The implementation of effective governance with tools such as inclusive policies, regulations, and mitigation strategies seems to mitigate the perceived harms of overtourism. Overtourism’s perceived harms may be reduced when effective governance—such as inclusive policies, regulations, and mitigation strategies—is implemented. In contrast, more negative perceptions tend to be shaped when political mechanisms are viewed as weak or ineffective by residents. The behavior of tourists is the primary driver of how overtourism is perceived by residents, but not the sole parameter. It is important to notice, however, that the performance of local government management in destinations also affects how overtourism is perceived. When the governance of tourism is taken as inclusive, responsive, and well coordinated, the negative feelings against overtourism will tend to diminish. In particular, positive government management practice evaluations have been viewed as foiling the adverse impact of overtourism on the perception of the residents [16]. This illustrates that the issue of political sustainability, which is promoted through transparent decision-based processes, policy responsiveness, and local participation can be beneficial in moderating the concerns of communities facing excessive tourism pressure. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4.

Perceived political sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.5. Technological Sustainability

Technology and ICT, with smart tourism tools, can ease overtourism pressure. Technologically progressive destinations may be perceived as more resilient [11]. The use of smart tourism technologies has been examined for their potential to enhance visitor experiences and improve operational efficiency [73]. It has also been suggested that such technologies play a pivotal role in promoting sustainable practices by helping to mitigate environmental and cultural heritage impacts [74]. Smart tourism utilizes information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve the effectiveness, sustainability, and overall experience of tourism for both tourists and locals [75]. As Shafiee [76] outlines, smart destinations incorporate IoT for monitoring and managing tourist flows, as well as mobile apps for delivering real-time information and personalized recommendations. By leveraging data from sensors, social media, and mobile devices, smart destinations can gain insights into tourist behavior and preferences. This data-driven approach enables destinations to optimize their offerings, manage crowds effectively, and improve visitor satisfaction. The adoption of smart tourism technologies seems to be able to improve the tourist experience as well as the performance of destination management systems. Accessibility and interactivity have been identified as key factors influencing smart technology–enhanced tourist experiences, both of which are significantly associated with visitor satisfaction. In addition, smart technologies have been shown to positively influence word of mouth, revisiting intention, and willingness to pay a premium [77]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5.

Perceived technological sustainability has an effect on residents’ perceptions of overtourism.

2.6.6. Residents’ Perception and Support for Tourism

Residents’ responses to tourism depend on how they view the effects of overtourism in their daily lives. According to the S–O–R framework, negative internal evaluations influence how external conditions impact behavioral intentions, such as support for tourism development. When residents see tourism as overwhelming, damaging to their quality of life, or poorly managed, they are less willing to support tourism initiatives. Negative perceptions of overtourism have been associated with a decline in how residents view their town’s livability, leading to stronger support for tourism restrictions, particularly during peak seasons [16]. Additionally, high levels of tourist seasonality have been linked to lasting lifestyle changes, affecting residents’ access to services and overall well-being [78]. Such disruptions may impair psychological coping mechanisms and reduce local support for ongoing tourism development. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H6.

Residents’ perceptions of overtourism have an effect on their support for tourism.

Figure 1 shows a conceptual model of this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The study focused on permanent residents of Istanbul and Athens who were at least 18 years old and had lived continuously in their city for a minimum of one year as of May 2025. An a priori power analysis conducted with G*Power 3.1.9.7 indicated that—assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), α = 0.05, and statistical power of 90%—a minimum of 123 valid surveys per city was required [79,80,81]. Therefore, the sample size was 136 in Istanbul and 149 in Athens.

Data were collected via an online questionnaire hosted on Google Forms. All survey items were set as “required” in Google Forms, so respondents could not continue or submit the questionnaire unless every question had been answered. Therefore, the final dataset contained no missing values. The survey link was shared only with individuals who met the screening criteria: continuous residence in the focal city for at least the previous 12 months, consistent with the United Nations Statistics Division’s “usual resident” standard [82], and no employment in or ownership of a business that earns direct income from tourism. Dissemination channels included local neighborhood forums, social media groups, and university email lists, resulting in a convenience sample of adult residents from both cities.

3.2. Measurement Tools

The scale items used in this study were adapted from instruments with established validity in the literature. Items measuring the five sustainability dimensions—environmental, economic, sociocultural, political, and technological—were sourced from previous work [11]. Perceptions of overtourism were measured using items based on existing scales [16], and residents’ support for tourism was assessed using established items from earlier studies [83]. The measurement tools are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement tools.

All items were administered to participants in both Istanbul and Athens using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The scale was translated into Turkish and Greek through a forward–backward translation procedure, and conceptual equivalence was confirmed by subject-matter experts during the translation process.

3.3. Data Analysis

The structural equation model was estimated using SmartPLS 4.1.1.4. The reliability and validity of the measurement model were verified with composite reliability, AVE, and the Fornell–Larcker discriminant matrix [84]. Then, structural path coefficients were obtained using the bootstrap method with 5000 replications [80,85]. For intercity comparisons, measurement equivalence was tested with the MICOM procedure, and path coefficients in the Istanbul and Athens groups were compared with the help of permutation/PLS-MGA [86].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 285 people participated in the study, 136 from Istanbul and 149 from Athens. In the case of Istanbul, 60% of participants identified as male, 39% as female, and 1% chose not to disclose their gender. The average age of participants in Istanbul was 29.3 years, ranging from 18 to 69 years. The average length of residence in the city was approximately 18.9 years. By comparison, the Athens sample consisted of 56% male and 42% female respondents, with 2% choosing not to state their gender. The average age of participants in Athens was slightly higher at 32.3 years, ranging from 18 to 65 years. On average, participants had lived in Athens for 14.3 years. These demographic distributions suggest that both samples were predominantly composed of long-term residents and included a balanced mix of age and gender, thus ensuring sufficient diversity for comparative analysis across contexts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of demographics.

4.2. Model Refinements

To improve the psychometric adequacy of the measurement model, several indicators were removed based on their consistently low outer loadings in both the Istanbul and Athens samples. Specifically, the items ECS5, ENS4, ENS6, ENS7, ENS8, RST1, SCS5, TES1, and TES5 demonstrated insufficient factor loadings (below the recommended threshold of 0.50) across both groups. The decision to exclude these indicators was guided by empirical recommendations [85] alongside theoretical considerations with the aim of ensuring a more reliable and valid representation of the underlying constructs.

4.3. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

In line with the PLS-SEM procedure, evaluation of the reflective measurement model was carried out through tests of indicator reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Internal consistency and convergent validity.

As seen in Table 3, all constructs in both samples exceeded the thresholds for internal consistency and convergent validity. In particular, all composite reliability (CR) scores were well above the recommended minimum of 0.70, while average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the threshold of 0.50, indicating that the constructs explained a sufficient proportion of the variance of their indicators. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha values were consistently high, further confirming the internal consistency of the constructs, as was the case with common-method variance (CMV). Following Kock [87], full-collinearity VIFs were inspected in SmartPLS. At the construct level, VIF values ranged from 1.27 to 2.72 for Athens and 1.57 to 2.89 for Istanbul, all comfortably below the conservative 3.3 threshold, indicating that CMV was unlikely to bias the results [88].

4.4. Discriminant Validity

HTMT (heterotrait–monotrait ratio) was used to assess discriminant validity. Table 4 and Table 5 present the HTMT values in pairs for the Istanbul and Athens samples, respectively.

Table 4.

HTMT matrix (Istanbul).

Table 5.

HTMT matrix (Athens).

All HTMT values in both city samples were below the conservative threshold of 0.85. This confirmed that the constructs showed sufficient discriminant validity and made sure that each latent variable was empirically distinct from the others in the model.

4.5. Structural Model Assessment

To assess whether the latent constructs were measured equivalently between the two groups, the following tests were applied.

Model Fit

The overall measurement models for both cities displayed satisfactory absolute fit. In Istanbul, the saturated solution yielded an SRMR of 0.092—below the pragmatic 0.10 ceiling that is often accepted for complex PLS-SEM models—whereas constraining the structural paths raised the SRMR to 0.252. Complementary indices (d_ULS = 3.700, d_G = 1.405, χ2 = 1 073.120, NFI = 0.676) confirmed an adequate, if modest, correspondence between model and data. The Athens sample showed a similar pattern: the saturated model again satisfied the SRMR rule of thumb (0.067), but imposition of the theoretical structure increased the index to 0.211 and slightly lowered the NFI (0.746 → 0.703), suggesting that while the measurement model was sound, the structural paths explained only part of the observed covariation.

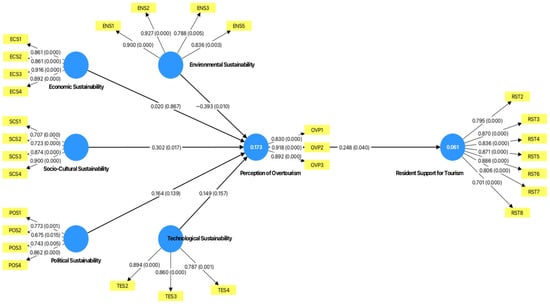

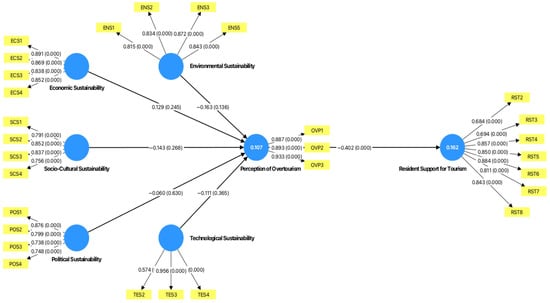

Predictive power was moderate overall. In Istanbul, the model accounted for 17% of the variance in the perception of overtourism construct (R2 = 0.173) and 6% in resident support for tourism (R2 = 0.061). In Athens, the proportions were reversed: only 11% of overtourism perceptions were explained (R2 = 0.107), but 16% of resident support (R2 = 0.162) was captured by the model. These figures indicate that additional antecedents of overtourism perceptions are likely at play in Athens, whereas the determinants of support are more fully represented there than in Istanbul.

Effect-size analysis underscored this difference. In Athens, the path from overtourism perceptions to resident support produced a medium effect (f2 = 0.193), highlighting the pivotal role of perceived crowding and congestion in shaping endorsement of tourism. All sustainability evaluations exerted only small effects on overtourism perceptions (0.002 ≤ f2 ≤ 0.018). In Istanbul, by contrast, the same overtourism-to-support link was small (f2 = 0.065), and the most influential driver of overtourism perceptions was environmental sustainability (ENS; f2 = 0.110), followed by sociocultural sustainability (SCS; 0.049), perceived positive outcomes (POS; 0.022) and tourism economic sustainability (TES; 0.014). Economic cost sustainability (ECS) was virtually irrelevant (f2 ≈ 0).

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the structural path diagrams for the Istanbul and Athens samples, respectively.

Figure 2.

Structural path model (Istanbul).

Figure 3.

Structural path model (Athens).

4.6. Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM)

To assess whether the latent constructs were measured equivalently between the two groups (Istanbul and Athens), the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) procedure was applied, following the structured three-step approach that evaluates (1) configural invariance, (2) compositional invariance, and (3) equality of means and variances [86].

Step 1—Configural invariance

The Istanbul and Athens datasets were estimated with identical indicators, weighting schemes, and algorithm settings. Therefore, configural invariance was satisfied, establishing a common conceptual foundation for cross-group comparison.

Step 2—Compositional invariance

Permutation testing (5000 resamples) confirmed that for every construct, the original correlation between the two groups’ composite scores exceeded the 5% permutation quantile and the associated p-value was above 0.05 (Table 6). Thus, all seven latent variables exhibit full compositional invariance.

Table 6.

Compositional invariance results (Istanbul vs. Athens).

Step 3—Equality of means and variances (scalar invariance)

Mean-equality tests (Table 7a) showed significant group differences for ENS, POS, TES, OVP and RST, whereas ECS and SCS means were statistically indistinguishable. Variance-equality tests (Table 7b) revealed a significant difference only for ENS. Because some—but not all—constructs achieve scalar invariance, the study attained partial measurement invariance (configural + compositional fully met, scalar partially met), which is sufficient to proceed with multiple-group analysis provided interpretations remained cautious.

Table 7.

Equality of latent means. (a) Mean-equality tests; (b) Variance-equality tests.

4.7. Multigroup Analysis (MGA)

Following the MICOM procedure, although full measurement invariance cannot be achieved, the establishment of configural and partial compositional invariance allows the application of multiple-group analysis (MGA). MGA was used to examine whether structural relationships differed significantly between the Istanbul and Athens samples. The PLS–MGA approach [85] was used, which compares path coefficients between groups based on nonparametric resampling. Table 8 shows multigroup comparison of structural path coefficients.

Table 8.

Multigroup comparison of structural path coefficients.

The multigroup analysis revealed that only two structural paths differed significantly between the cities. First, the link between sociocultural sustainability and overtourism perceptions (SCS → OVP) was positive and moderate in Istanbul (β = 0.302), but negative in Athens (β = −0.143), and the between-group difference was significant (p = 0.013). Thus, stronger sociocultural sustainability evaluations heighten crowding concerns in Istanbul, yet alleviate them in Athens, suggesting that residents of the two cities interpret the sociocultural footprint of tourism in opposite ways. Second, the link between overtourism perceptions and resident support (OVP → RST) was likewise city-specific: perceptions of crowding modestly increased support in Istanbul (β = 0.248), but eroded it markedly in Athens (β = −0.402), with the difference again significant (p = 0.005). This indicates that Istanbul residents tolerate overtourism when they still perceive net benefits, whereas Athenians withdraw their backing as soon as crowding becomes salient. All remaining relationships—those from environmental, economic cost, positive outcomes, and tourism economic sustainability (ENS, ECS, POS, TES) with overtourism perceptions—showed no statistically reliable group differences (p > 0.10), implying that these sustainability dimensions shape crowding perceptions in broadly similar ways across the two urban contexts.

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Implications

5.1. Key Findings

The empirical results underscore that residents’ perceptions of overtourism are intricately shaped by how they evaluate sustainability across five dimensions. In line with the S–O–R framework, the five sustainability dimensions act as external stimuli (S) that influence cognitive evaluations (O), which then affect behavioral intentions, specifically resident support for tourism (R).

Unlike earlier resident-attitude studies that consistently identified environmental sustainability as the dominant driver across destinations [10,21,58], our side-by-side analysis shows a different hierarchy: sociocultural sustainability weighs heaviest in Athens, whereas environmental cues remain paramount in Istanbul, underscoring the contextual nature of resident responses.

In Athens, only sociocultural sustainability showed a notable (albeit negative) association with overtourism perception, while environmental and economic sustainability connections were weak and statistically non-significant. This finding supports the H1 notion that positive sustainability appraisals do not necessarily mitigate overtourism stress. Rather, they can amplify or dampen it depending on local interpretations and expectations. For instance, the negative association between environmental sustainability and overtourism perception in Athens suggests that well-maintained green or heritage amenities may reassure residents that crowding is under control rather than signaling added pressure. Conversely, in Istanbul, environmental sustainability exhibited a stronger negative relationship with overtourism perception, implying that green infrastructure and environmental management may effectively buffer resident concerns.

Economic sustainability (H2) did not emerge as a significant predictor of overtourism perception in either city, possibly reflecting differences in how the tourism economy is distributed and perceived.

Sociocultural sustainability (H3) followed a similar pattern. Its path was significant and positive in Istanbul, suggesting that perceived sociocultural strain can amplify resident dissatisfaction, as also reported by Caro-Carretero and Monroy-Rodríguez [72]. In Athens, however, the relationship was negative and not statistically significant, which may indicate that community-based cultural initiatives help to offset crowding concerns.

Political sustainability (H4) and technological (H5) sustainability dimensions were not statistically significant predictors of overtourism perception in either city. While these domains are prominently featured in sustainability and smart tourism literature [28,42], their limited perceptual salience suggests they may lack visibility or resonance with residents lived experiences, an important consideration for destination planners and policymakers.

Finally, overtourism perception had a significant and negative impact on residents’ support for tourism development in Athens (H6; β = −0.402), consistent with prior applications of the S–O–R model, which posited that negative affective evaluations reduced behavioral support [54]. In Istanbul, this relationship was positive, but not statistically significant, possibly indicating a higher threshold of tolerance, greater economic dependence, or differing expectations of tourism’s role in the urban fabric [49].

Collectively, these findings validate the explanatory capacity of the S–O–R framework while emphasizing its contextual sensitivity. The varying strength and directionality of relationships across cities highlight how residents’ responses are filtered through localized perceptions of governance, infrastructure, and cultural resilience. While environmental factors emerge as salient in both cases, albeit with consistently negative interpretations, political and technological sustainability remain under-activated constructs, pointing to gaps in public communication or engagement. These divergences underscore the need for perception-sensitive tourism planning, tailored not only to objective sustainability indicators but also to how these indicators are interpreted and internalized by local communities.

The null results for political and technological sustainability warrant closer scrutiny. Both dimensions are often “back office” domains: governance processes and digital infrastructure tend to be invisible to residents unless they fail conspicuously. This muted salience echoes findings by Koens et al. [15] that institutional capacity is perceived only indirectly through service breakdowns. In Athens and Istanbul, therefore, POS and TES may lack the perceptual “hooks” that trigger overtourism concern, suggesting that planners must actively publicize governance measures and technology tools if they hope to shape resident attitudes.

5.2. Contribution to Theory

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by extending the S–O–R framework into the domain of overtourism and urban sustainability. While S–O–R has been widely applied in tourism and consumer-behavior research to explain how external stimuli shape internal states and behavioral outcomes [50,54], its application to overtourism has largely centered on tourist experiences. The present study shifts the analytical focus toward residents, offering a multidimensional, context-sensitive perspective.

By conceptualizing five sustainability dimensions as distinct external stimuli, this research advances a more granular understanding of how residents process tourism-related pressures. It moves beyond linear cause-and-effect reasoning and responds to recent scholarly calls for models that account for place-based variability and perceptual complexity [44,89].

The findings also refine the conceptualization of the organism component in S–O–R theory. Rather than treating it as a static affective response, this study demonstrates that resident perception is shaped by collective urban experience, local governance structures, and cultural expectations. The contrast in the strength—rather than the sign—of environmental sustainability’s influence in Athens and Istanbul reinforces the notion that perception is not a passive intermediary, but a dynamic, city-specific construct that is responsive to governance visibility, urban form, and symbolic interpretations of place.

Additionally, this study is among the first to formally incorporate political and technological sustainability within the S–O–R stimulus layer in overtourism modeling. Although these two dimensions did not yield statistically significant relationships, their inclusion reflects a necessary evolution in sustainability scholarship. As highlighted in recent frameworks [27,55], governance capacity and digital infrastructure are increasingly central to the long-term resilience of tourism systems. The limited perceptual salience found here may stem from their low public visibility or developmental immaturity—issues that future research should investigate more closely.

Empirical support for the S–O–R framework was further reinforced through the observed negative link between overtourism perception and residents’ support for tourism in Athens. This confirms that internal evaluations, shaped by multidimensional sustainability perceptions, meaningfully influence behavioral intentions. The variation in model strength between cities also illustrates that such processes are deeply embedded in urban morphology, sociopolitical histories and resident expectations, underscoring the flexibility and transferability of the S–O–R model when integrated with contextual sustainability thinking.

5.3. Contextual Insights: Reflections on the City-Specific Dynamics of Athens vs. Istanbul

The comparative analysis of Athens and Istanbul reveals that overtourism arises not solely from tourist volume but through spatial, governance, and sociohistorical dynamics. In Athens, perceptions are shaped mainly by sociocultural concerns within a centralized planning regime and dense urban form, concentrating tourism pressure in residential zones—paralleling cases like Venice and Dubrovnik [34,55]. Istanbul, by contrast, exhibits stronger associations between sustainability and overtourism, likely due to its polycentric layout and dispersed tourism infrastructure. In Istanbul, the lack of a statistically significant RST effect suggests either muted discontent or a distinct sociopolitical framing. Environmental sustainability diverges notably: in Athens, it modestly alleviates crowding perception; in Istanbul, it signals institutional responsiveness [28,48]. Both cities show weak links to political and technological sustainability, reflecting an institutional visibility gap. Tools like predictive analytics or emotional mapping [36,40] remain under-leveraged. Effective governance must integrate perceptual and spatial dimensions within local contexts.

5.4. Practical Implications

The findings highlight that overtourism perceptions are shaped differently across urban contexts, necessitating destination-specific strategies. In Athens, the influence of sociocultural sustainability perceptions—together with residents’ sensitivity to crowding—suggests an urgent need for interventions tailored to dense heritage areas. Policymakers may prioritize:

- Community-based heritage conservation, ensuring that preservation efforts do not displace residents or commodify local identity.

- Green infrastructure projects that not only manage environmental impacts but also improve quality of life for residents.

- Affordable housing policies and anti-displacement mechanisms that mitigate economic externalities of tourism [33,55].

In contrast, Istanbul’s more fragmented and polycentric urban structure calls for a different approach. Although overtourism perception is lower, this may mask latent tensions. Proactive strategies should include improved infrastructure planning, visitor dispersal, and public-communication mechanisms that elevate resident awareness and engagement before pressures intensify. Furthermore, across both cities, the findings indicate that overtourism perception can erode resident support in Athens, even when sustainability metrics are moderately positive. As such, building resident trust and fostering a sense of ownership and co-management are critical components of long-term destination resilience.

The study’s non-significant findings regarding technological and political sustainability dimensions reveal both a challenge and an opportunity. While academic models emphasize their relevance [28,42], these tools often remain invisible or under-communicated to the general public. To address this, tourism planners and destination management organizations (DMOs) should:

- Enhance the visibility of smart tools, such as geospatial crowd monitoring, predictive analytics, and mobile-based feedback systems.

- Publicly communicate their role, impact, and limitations in shaping tourism governance.

- Integrate citizen participation in the design and evaluation of digital governance systems [39,40].

In sum, this study validates the theoretical utility of both the S–O–R paradigm and a five-dimensional sustainability framework in overtourism research. It demonstrates how resident responses are mediated through layered perceptual mechanisms and confirms that sustainability is not monolithic, but hierarchically and situationally interpreted. These insights offer a replicable, yet adaptable theoretical model for future studies investigating overtourism dynamics in diverse urban contexts.

5.5. Theoretical and Managerial Contributions

From the managerial implications perspective, the results suggest that DMOs and policymakers should consider residents not as passive recipients of tourism impacts, but active actors whose perceptions are able to shape the success or failure of tourism strategies. In particular, investing in smart tourism technologies, inclusive governance, and tangible socioeconomic benefits can assist in diminishing overtourism tension while promoting local support. The comparative design reveals the context-dependent nature of overtourism perception, challenging universal or one-dimensional narratives and emphasizing the need for place-sensitive modeling.

5.6. Limitations

Despite the considerable contributions received, the present study has several limitations. First, we need to consider that the sampling methodology relied on convenience sampling and online questionnaire distribution, which may limit the representativeness of the participant pool and introduce potential selection bias. Furthermore, the research employed a cross-sectional design, with data being collected at one point in time. This limits the opportunity for making causal inferences and captures the development of resident perceptions. Finally, the contextual scope of the study was limited to Athens and Istanbul, two eastern Mediterranean cities. Therefore, the results cannot be directly attributed to other countries, especially those with differing cultural, political, or socioeconomic settings.

5.7. Future Directions

There are various possible directions that future research could explore and that are likely to enhance the current results. Longitudinal research with monitoring on how resident’s perceptions and attitudes evolve over time would allow further assessment of the dynamic relationships outlined in the S–O–R framework and may assist in the identification of potential tipping points. In addition, contextual expansion would be a future direction recommendation, with model testing in a more diversified set of urban and rural destinations (e.g., with varying levels of tourism intensity, infrastructure, and governance complexity) for increased generalizability. From the qualitative augmentation perspective, the use of methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observation, or emotional mapping may reveal more subtle dynamics underpinning residents’ perceptions of overtourism. Finally, future research could address the mediational role of variables such as media consumption, digital literacy, or political interest in the formation of residents’ perceptions towards tourism in relation to the residential population, especially in increasingly digitized tourism environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V., Ş.O. and B.Y.; methodology, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, E.V., Ş.O. and B.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.V., Ş.O. and B.Y.; project administration, B.Y.; funding acquisition, E.V., Ş.O. and B.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Türkiye and approved by the Institutional Review Board of BETADER Science and Advisory Board (reference 250625-001, date of approval 10 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Tourism. International Tourist Arrivals Grew 5% in Q1 2025 (World Tourism Barometer); UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 21 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, H.; Barboza, M.; Nogueira, C. Perceptions and Behaviors Concerning Tourism Degrowth and Sustainable Tourism: Latent Dimensions and Types of Tourists. Sustainability 2025, 17, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. International Tourist Arrivals in Europe 2006–2024; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 10 June 2025; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/273598/international-tourist-arrivals-in-europe/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Ndrevataj, M. (Ed.) Cultural sustainability for sustainable cities development: Notes from UNESCO and Venice City. In The Sustainable Organization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Athens International Airport S.A. (5 August 2024). Monthly Traffic Development. July 2024. Available online: https://investors.aia.gr/userfiles/LPFiles/RegulatoryAnnoucements/MonthlyTrafficDevelopment_August_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Athens International Airport S.A. (15 January 2055). Passenger Traffic 2024—Annual Summary. Available online: https://investors.aia.gr/userfiles/LPFiles/financial-results/2024/FINAL_ENG_AIA_2024ANNUALFINANCIALREPORT.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Istanbul Directorate of Culture & Tourism. (1 September 2024). 10.5 Million Tourists in Istanbul in Seven Months 2024. [Press Release]. Available online: https://money-tourism.gr/en/turkey-10-5-million-tourists-in-istanbul-in-7-months-2024/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Athens International Airport S.A. (10 February 2020). Traffic Figures 2019—Annual Summary. Available online: https://investors.aia.gr/userfiles/0954d64f-148d-4743-a207-b10e00cab4be/CorporatePresentation_Q125updated_1.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Chee, S.Y.; Salee, A. Scale development for measuring sustainability of urban destinations from the perspectives of residents, tourists, businesses and government. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 33, 290–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Overtourism: Lessons for a Better Future; Responsible Tourism Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Placet, M.; Anderson, R.; Fowler, K.M. Strategies for sustainability. Res. Technol. Manag. 2005, 48, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Buades, M.E.; García-Sastre, M.A.; Alemany-Hormaeche, M. Effects of overtourism on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia, Spain. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Markag. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, N.; Abrantes, J.L.; Costa, S. Mapping the sustainable development in health tourism: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, J.; Yñiguez, R. Measuring overtourism: A systematic review of quantitative indicators. Tourism Manag. 2021, 88, 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UN Tourism Data Dashboard: International Tourist Arrivals 2019–2024 [Dataset]. World Tourism Organization. 2025. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/un-tourism-tourism-dashboard (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Building Permits—Annual Data [Dataset]. European Commission. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sts_cobp_a/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Mihalič, T.; Žabkar, V.; Cvelbar, L.K. A hotel sustainability business model: Evidence from Slovenia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 824–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rojo, C.; Llopis-Amorós, M.; García-García, J.M. Overtourism and sustainability: A bibliometric study (2018–2021). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Mohd Isa, S.; Md Salleh, N.Z.; Abd Aziz, N.; Abdul Murad, S.M. Exploring the nexus of over-tourism: Causes, consequences, and mitigation strategies. J. Tour. Serv. 2025, 16, 99–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K.; Liao, M.; Liu, X. Exploring the convergence of cyber–physical space: Multidimensional modeling of overtourism interactions. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 2425–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, R.S.; Alamsyah, A. Analyzing overtourism dynamics in Bali: A data-driven approach using geospatial analysis and text classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 Beyond Technology Summit on Informatics International Conference (BTS-I2C), Jember, Indonesia, 19 December 2024; pp. 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Reis, P.; Abrantes, J.L. The influence of terrorism in tourism arrivals: A longitudinal approach in a Mediterranean country. Ann Tour Res. 2020, 80, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drápela, E. Creating strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of overtourism in rural destinations: Experience from the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchon, F.; Rauscher, M. Cities and tourism, a love and hate story; towards a conceptual framework for urban overtourism management. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilović Hristić, N.; Pantić, M.; Stefanović, N. Tourism as an opportunity or the danger of saturation for the historical coastal towns. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W.; Dodds, R. Overcoming overtourism: A review of failure. Tourism Rev. 2022, 77, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V.; Séraphin, H. What smart and sustainable strategies could be used to reduce the impact of overtourism? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardhana, A.J. Forecasting future tourism demand to popular tourist attractions to assess overtourism: A machine learning modeling approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 27–28 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin, M.; Mahayasa, D.P.S.; Satyawan, D.S.; Nurudin, A. Revenge tourism in Banyumas Regency: Examining the interrelationship among social media, overtourism, and post-COVID-19 impacts. Smart Tour. 2024, 4, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nădăși, L.; Kovács, S.; Szőllős-Tóth, A. The extent of overtourism in some European locations using multi-criteria decision-making methods between 2014 and 2023. Int. J. Tour Cities 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Zacher, D.; Pechlaner, H.; Namberger, P.; Schmude, J. Strategies and measures directed towards overtourism: A perspective of European DMOs. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre dos Santos, T.; Neto Marinheiro, R.; Brito e Abreu, F. Wireless crowd detection for smart overtourism mitigation. In Smart Life and Smart Life Engineering; Kornyshova, E., Deneckere, R., Brinkkemper, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, I.; Leung, R. Can sensory marketing be used to address overtourism? Evidence from religious attractions in Kyoto, Japan. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2024, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tour. Geogr. 2024, 26, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Homestay-tourism—A viable alternative to the perils of overtourism in the Darjeeling hills of West Bengal, India. Environ. Conserv. J. 2024, 25, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S. Residents’ perceptions and attitudes toward tourism development: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venice, E.; Unesco, R.; Municipality, V. Managing Cultural Destinations: The Case of Venice; UNWTO Reports; UNWTO: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, C.; Dolnicar, S.; Abrantes, J.L.; Kastenholz, E. Heterogeneity in risk and safety perceptions of international tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steber, F.; Mayer, M. Overtourism perception among residents in a rural proximity destination during the COVID-19 pandemic—The writing on the wall for a sustainability transition of tourism? Z. Für Tourwiss. 2024, 16, 228–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aguirre, D.P.; Alvarado-Sizzo, I.; Moury-Fernandes, B.G. Intangible cultural heritage versus tourism: Residents’ reactions to temporal overtourism during the Day of the Dead in Mixquic, Mexico. J. Herit. Tour. 2025, 20, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, S.A.M.; Azinuddin, M.; Mat Som, A.P.; Hanafiah, M.H. Overtourism impacts on Cameron Highlands community’s quality of life: The intervening effect of community resilience. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 22, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, V.; Benedetto, C.; Loesch, M. The Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) paradigm as a guiding principle in environmental psychology: Comparison of its usage in consumer behavior and organizational culture and leadership theory. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2023, 3, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyamada, S. Horticultural overtourism in Tokyo: Coopetition for successful enticement of visitors from over- to less crowded gardens. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Huang, Z.; Shen, G.; Lin, H.; Lv, M. Urban overtourism detection based on graph temporal convolutional networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M. Explaining residents’ behavioral support for tourism through two theoretical frameworks. J. Travel. Res. 2021, 61, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M. European historic cities and overtourism—Conflicts and development paths in the light of systematic literature review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourdoubas, J. Evaluation of overtourism in the island of Crete, Greece. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peloponnisios, M. The European Commission as a policy entrepreneur in addressing overtourism. HAPSc Policy Briefs Ser. 2024, 5, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The perception of overtourism from the perspective of different generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.P.; Mundet, L. Tourism-phobia in Barcelona: Dismantling discursive strategies and power games in the construction of a sustainable tourist city. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2021, 19, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagena, A. Overtourism: Definition and impact. Acad. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, S.V.; Howard, D.R. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.R.; Long, P.T.; Allen, L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Tourism impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J. Travel. Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Montgomery, D. The attitudes of Bakewell residents to tourism and issues in community responsive tourism. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Porras-Bueno, N.; Plaza-Mejía, M.Á. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muler González, V.; Coromina Soler, L.; Galí Espelt, N. Overtourism: Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity—A case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.B.; de Andrade, M.M. Overtourism: Residents’ perceived impacts of tourism saturation. Tour. Anal. 2024, 27, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.C.; Schinckus, C.; Chong, F.H.L.; Nguyen, B.Q.; Tran, D.L.T. Tourism and contribution to employment: Global evidence. J. Econ. Dev. 2024, 27, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsud, N.; Promsaard, S. The effects of residents’ image and perceived tourism impact to residence satisfaction and support: A case study of Hua-Hin Prachubkirikhan. In Proceedings of the 2015 Vienna Presentations, The West East Institute International Academic Conference Proceedings, Vienna, Austria, 12–15 April 2015; pp. 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J. Travel. Res. 2000, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Carretero, R.; Monroy-Rodríguez, S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism and sustainable tourism management: Planning to prevent future problems in destination management—The case of Cáceres, Spain. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2447398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, W.Y.; Leong, Y.Z.; Leong, W.S. Smart tourism in ASEAN: Leveraging technology for sustainable development and enhanced visitor experiences. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Art. Innov. 2024, 4, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkad, S.B. Leveraging smart tourism: Enhancing visitor experiences through technological integration. Int. J. Tour. Technol. 2024, 10, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, M.M. Navigating overtourism destinations: Leveraging smart tourism solutions for sustainable travel experience. Smart Tour. 2024, 5, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. Investigating the impact of smart tourism technologies on tourists’ experiences. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Dembińska, M. Deconstructing the overtourism-related social conflicts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yaprak, B.; Cengiz, E. Do consumers really care about social media marketing activities? Evidence from Netflix’s Turkish and German followers in social media. Ege Acad. Rev. 2023, 23, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses (Rev. 3; ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/67/Rev.3); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Munanura, I.E.; Kline, J.D. Residents’ support for tourism: The role of tourism impact attitudes, forest value orientations, and quality of life in Oregon, United States. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Appolloni, A.; Chirico, A. The adoption of key performance indicators for sustainability: A five-dimensional framework. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 31, 3216–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).