Abstract

(1) Background: This study investigates whether older adult individuals support childcare policies not only out of altruism, but also due to extended self-interest arising from intergenerational co-residence. It challenges the conventional view that welfare attitudes are shaped solely by one’s own life-cycle needs. (2) Methods: Using the 2013 and 2016 waves of the Korean Welfare Panel Study waves of the Korean Welfare Panel Study, a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach compares attitudes toward government childcare spending between older adults living with children (Co-residing Older Adults) and those who do not (Non-co-residing Older Adults), before and after universal childcare policies were introduced in 2013. (3) Results: The Co-residing Older Adults consistently expressed stronger support for family policies than their counterparts. However, this support did not significantly increase after the 2013 reform, indicating that extended self-interest may not be sensitive to short-term policy changes. (4) Conclusions: Extended self-interest appears to be a stable orientation shaped by family context rather than a flexible, policy-reactive stance. These findings highlight the role of intergenerational household ties in shaping welfare attitudes and offer implications for fostering generational solidarity in aging societies.

1. Introduction

In democracies, the preferences of citizens play a critical role in legitimizing and shaping the scope of welfare states. However, the relationship between public opinion and policy is far from linear or deterministic. Numerous studies have shown that while public attitudes exert influence, this influence is conditional on political institutions, party systems, and interest group dynamics [1,2]. Nevertheless, understanding these attitudes is important not because they directly dictate policy, but because they reflect broader public values, inform electoral behavior, and delineate the boundaries within which policymakers operate.

One area where public preferences have drawn growing scholarly interest is intergenerational solidarity. As welfare states undergo demographic and institutional transformations, potential tensions between age groups over resource allocation have become more salient. Traditional research often frames these tensions in terms of self-interest tied to one’s life stage or socioeconomic class [3,4,5]. However, a more nuanced understanding must account for how intergenerational ties within families shape attitudes that transcend narrow self-interest.

This paper explores the hypothesis that older adult individuals may support policies targeted at younger generations—such as childcare—not merely out of altruism or ideology, but due to “extended self-interest” rooted in family relations. By co-residing with children or grandchildren, older adults may internalize the needs of other life stages, effectively broadening the scope of their self-interest. Such mechanisms may reduce perceived intergenerational conflict and enable greater consensus over pro-family policies. The present study draws from the author’s doctoral dissertation, The Relationship between the Expansion of Welfare Institution and Generational Conflict [6].

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Interaction Between Social Generational Relations and Intra-Family Generational Relations

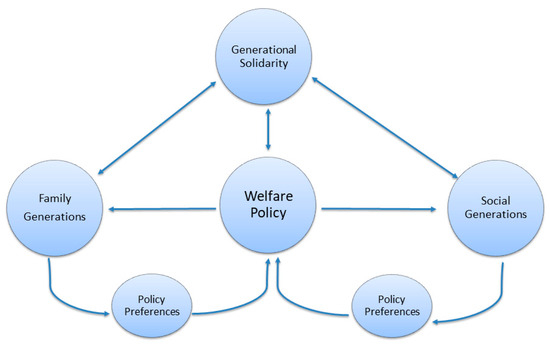

To understand how generational solidarity operates in shaping welfare attitudes, especially in aging societies, it is essential to distinguish between two analytically distinct but interrelated dimensions of generational relations: social generational relations and intra-family generational relations [5,7]. While the former refers to institutionalized policy cohorts—such as children, working-age adults, and the older adults—defined by their position within the welfare state architecture, the latter pertains to genealogical, lived relationships among family members who cohabit, care for, and support one another over the life course [8]. Social generational relations emerge from the way welfare states are structured to serve different age groups (see Figure 1). For instance, public pension systems are designed for older adults, childcare subsidies and education benefits are oriented toward younger cohorts, and unemployment insurance supports the working-age population. These cohort-specific allocations reflect not only administrative categorization but also social norms regarding entitlement and responsibility. Consequently, the way resources are distributed across these groups becomes a focal point for discussions of generational equity, often raising concerns about zero-sum trade-offs in an era of fiscal constraint and demographic change [9,10] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamics of family and social generations in shaping welfare policies.

In contrast, intra-family generational relations are governed less by institutional logics and more by kinship obligations, affective bonds, and everyday exchanges. These include intergenerational financial transfers, time investments such as childcare and eldercare [7], and normative commitments shaped by cultural values such as filial piety. These familial interactions are often invisible in public discourse but constitute the primary arena where generational dependencies are negotiated in practice. As Uhlenberg [5] notes, family networks are often the only space in which meaningful intergenerational dialogue and support occur—especially across large age gaps rarely bridged in other social contexts.

Importantly, these two types of generational relations—social and familial—do not exist in isolation. Rather, they interact dynamically through the mediation of public policy. Welfare states can either reinforce or relieve the burdens experienced within families. For example, expansion of childcare services may reduce grandparents’ caregiving load, while the introduction of public long-term care for older adults can ease the financial and emotional pressure on adult children. Conversely, welfare retrenchment or the introduction of “refamilializing” policies—those that shift caregiving responsibilities back onto households—can exacerbate intra-family tensions and reinforce inequalities, particularly along gender and class lines [11].

Esping-Andersen [12] succinctly captures this dynamic when he writes, “If the need for care within the family—whether economically or in terms of time—decreases, family members are likely to meet more frequently. A highly familialized welfare model, however, tends to have a negative impact on fostering family solidarity.” In this framing, defamilialization—through strong public provision of care—can foster voluntary and emotionally meaningful interactions across generations, while refamilialization risks instrumentalizing those same relationships under economic duress. Such refamilialization processes have been empirically observed in countries like Sweden. Ulmanen and Szebehely [13], in their study of eldercare, document a bifurcation trend wherein affluent older adult individuals increasingly purchase market-based care services, while economically disadvantaged elders rely more heavily on informal support—typically from daughters. This dualization not only reproduces class inequality but also imposes gendered expectations within families, deepening existing care asymmetries. These developments complicate any simplistic notion of solidarity: what may appear as voluntary intergenerational support might, in fact, be the result of constrained choices.

In East Asian societies, where institutional welfare is still developing and family remains a central organizing unit of social support, these dynamics take on additional significance [14]. Korea and Japan, for example, have implemented policies that actively encourage familial responsibility over state responsibility. Japan’s 2013 policy of exempting up to 15 million yen from taxes when grandparents transfer education funds to grandchildren is a prime illustration. While framed as incentivizing intergenerational investment, such measures effectively substitute private obligation for public provision, disproportionately benefiting wealthier households and further embedding inequality within familial structures [13,15]. Korea’s welfare system, still in a phase of institutional expansion, displays similar characteristics. Public spending on childcare and eldercare remains modest relative to OECD averages, and care responsibilities are often absorbed by families—particularly by women in the “sandwich generation” who are caring for both young children and aging parents [16]. In this context, the burden of supporting vulnerable generations is not just a policy issue but a deeply personal, lived experience that shapes individual attitudes toward welfare. These dynamics help explain why older adult individuals may support policies that do not directly benefit them—such as childcare subsidies or parental leave. If they reside with grandchildren, or have regular caregiving responsibilities, their perceptions of need are not abstract or ideological but grounded in daily interactions. Their support for child-oriented welfare, then, can be interpreted as an expression of what this study terms “extended self-interest”—a broadened understanding of welfare need that includes other generational members within the household or kin network.

Moreover, empirical studies show that intergenerational transfers are not unidirectional. Albertini et al. [7] and Goerres & Tepe [17] provide evidence that financial and emotional support often flows from older to younger generations, suggesting that older adults’ support for pro-child policies may not contradict self-interest but reflect a more complex, embedded form of it. As such, public attitudes toward redistribution may be shaped not only by perceived costs and benefits but also by relational proximities—by who lives with whom, who depends on whom, and who benefits from a policy indirectly. Recognizing the interaction between social and familial generational structures is thus crucial for understanding welfare preferences in contemporary societies. It challenges the view that intergenerational conflict is inevitable in aging societies, suggesting instead that interdependence within families can soften the boundaries of self-interest. However, the strength and direction of this effect are not uniform: they depend on policy design, household composition, cultural expectations, and broader social inequalities.

In sum, the intersection of social and intra-family generational relations provides a necessary conceptual foundation for analyzing how welfare attitudes are shaped. It moves beyond the binary of altruism versus selfishness, showing how support for redistributive policies can emerge from lived interdependence. This sets the stage for the next section, which elaborates on the notion of extended self-interest as both a theoretical refinement and an empirical strategy for capturing intergenerational solidarity within households.

2.2. Self-Interest and ‘Extended’ Self-Interest

The formation of welfare preferences has long been studied through the lens of self-interest. Class-based theories, drawing from Pierson’s [18] conception of “old politics,” posit that support for welfare expansion is largely shaped by individuals’ economic position. In this view, the working class tends to support redistributive policies due to the benefits of decommodification, while the upper class resists them owing to concerns over efficiency and fiscal burden [19]. According to this framework, the welfare state is a political project built on class cleavages, with the expansion of social protection viewed as the result of sustained working-class mobilization [20].

However, the explanatory power of class alone began to decline as structural changes—such as population aging, economic deindustrialization, and the rise of new social risks—transformed the landscape of social policy. The shift from a manufacturing-based to a service-oriented economy, along with the increased heterogeneity of life trajectories, has complicated the traditional alignment of class and policy preference [12]. Instead of a unified working-class block supporting “the welfare state,” individuals now hold diverse preferences depending on their age, household structure, and exposure to specific risks. As Ponza et al. [21] note, preferences for public spending began to diverge across life-cycle stages, with different cohorts expressing varying levels of support for pensions, healthcare, and childcare.

This transition marked the emergence of a new political cleavage: generational conflict. Bonoli and Häusermann [11] describe age-based divisions as one of the new fault lines in contemporary welfare politics. Critics argue that modern welfare states, while initially designed to ensure cross-class equity, now risk exacerbating inequalities between age cohorts. A growing body of literature warns that the disproportionate expansion of older adult-focused programs (e.g., pensions, long-term care) relative to investments in children and youth (e.g., childcare, education) may reflect the political dominance of older voters rather than normative fairness. Preston [10] famously warned that the reduction in poverty for older adults in the United States was achieved, in part, at the expense of children, given limited fiscal resources and uneven political representation. Pampel and Williamson [4], in a comparative study of 48 countries, also found that as the older adult population grows, so does per capita pension spending. But does this necessarily imply narrow, self-serving behavior on the part of the older adults? The assumption that welfare preferences are always driven by material self-interest—especially age-based interest—has come under scrutiny. Empirical research increasingly shows that intergenerational relationships, especially within families, complicate this narrative. Studies on intra-family transfers [7,16] reveal that older adult individuals often support their children and grandchildren financially, indicating that their welfare-related concerns may include the well-being of younger kin.

Building on this insight, Goerres and Tepe [17] introduce the idea that political preferences, especially among the older adults, are not always reducible to personal gain. Their comparative analysis of welfare attitudes shows that older adults may support public spending on children even when they are no longer direct beneficiaries. Rather than viewing policies for children as a resource drain, these individuals see them as investments in the future stability and well-being of their families. This behavior reflects what this study terms “extended self-interest”—a conception of self-interest that expands beyond the individual to include the immediate kin network [6]. It is important to distinguish this notion of extended self-interest from related concepts such as linked lives, kin altruism, or indirect reciprocity. While “linked lives” emphasizes how individuals’ life courses are embedded in relational networks, and “indirect reciprocity” refers to generalized mutualism within social systems, extended self-interest is more narrowly focused on policy preferences shaped by concrete familial interdependence. It captures instances where material interests are indirectly aligned through household or kinship ties, leading individuals to support policies that benefit others within their social unit. However, extended self-interest is not purely instrumental. It is entangled with cultural norms, affective commitments, and moral expectations. In societies with strong family obligations—such as Korea—intergenerational care is often taken for granted, and attitudes toward welfare may reflect this embedded value system. This also means that older adult individuals may support pro-child policies not out of calculated reciprocity, but because these align with their sense of familial duty. In this regard, extended self-interest is situated at the intersection of instrumental rationality and normative solidarity.

Over the past two decades, South Korea has implemented a series of welfare reforms with age-based eligibility: the Basic Old-Age Pension (2008), Long-Term Care Insurance (2008), the Basic Pension (2014), and for younger generations, universal free childcare (2014). These programs, though broadly accepted, have raised concerns about generational balance and public consensus. Do these programs deepen generational divides, or are they mediated by intergenerational relationships within families?

This study seeks to examine this question by exploring how older adult individuals perceive child-focused welfare policies depending on their family context. Specifically, it investigates whether older adults living with grandchildren—or otherwise closely connected to younger kin—express greater support for childcare and education policies. By using a difference-in-differences design, the analysis tests whether these preferences vary systematically, thereby revealing how the “boundaries of the self” may shift under conditions of extended interdependence. The question at the heart of this analysis is not whether older adult individuals are selfish or altruistic, but how their welfare attitudes are socially constructed through their family relationships. Extended self-interest serves as a conceptual bridge between individual-level preferences and the relational contexts in which they are embedded. In doing so, it challenges the notion that generational conflict is inevitable, suggesting instead that solidarity can emerge through everyday familial experiences.

3. Analytical Strategy

3.1. Data

To examine the differences between the older adult and non-older adult generations, as well as the changes in support levels for policies assisting families with children among older adult individuals with and without children in their households, before and after policy changes, data that repeatedly observe and measure the welfare attitudes of these groups are required. To address the research questions mentioned above, this study utilizes data from the Korean Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS), which repeatedly measures individual-level support for welfare programs, focusing on the welfare perception module. By applying a difference-in-differences model, the study compares changes in welfare attitudes within the older adult generation towards policies supporting families with young children, distinguishing between older adult individuals with and without beneficiaries in their households, before and after the implementation of universal free childcare in 2014.

KOWEPS develops special issues each year, conducting surveys on three main themes—children, the disabled, and welfare perceptions—on a three-year cycle. The welfare perception survey was conducted in the second (2007), fifth (2010), eighth (2013), and eleventh (2016) waves. The welfare perception module includes questions on general social and political attitudes, perceptions of growth and redistribution, views on income redistribution, opinions on funding welfare programs, and perceptions of government responsibility in different sectors, as well as attitudes towards welfare beneficiaries. This dataset can be combined with demographic and socio-economic information of respondents, their experience with various welfare programs, and information on whether there are beneficiaries within the household, all of which are part of the main KOWEPS survey [22].

The treatment effect in this study, defined as the “rapid change in child and family support policies,” refers to the introduction of universal free childcare in March 2013. Therefore, this study utilizes the eighth wave data collected between 1 January and 8 June 2013, and the eleventh wave data collected between 2 March and 8 June 2016, as the primary datasets for analysis. The eighth wave of the Korean Welfare Panel Study, which serves as the baseline for this analysis, was conducted between January and June 2013. Although the childcare reform was officially announced in March 2013, its legal enactment through the amendment of the Infant Care Act occurred in August 2013, with full implementation commencing in March 2014. As such, while respondents surveyed after March 2013 may have been exposed to media coverage or public discourse surrounding the forthcoming reform, the data used in this study were collected prior to the actual policy implementation. Therefore, the attitudinal measures can reasonably be interpreted as reflecting pre-treatment preferences. Using the fifth wave from 2010 as an alternative baseline would have ensured a clearer temporal separation between pre- and post-treatment periods. However, doing so would also increase the likelihood of confounding effects from unrelated exogenous factors and reduce the analytical focus on life-cycle-based generational dynamics, which is central to this study. For these reasons, the eighth wave was retained as the baseline, with due recognition of the associated limitations regarding potential anticipatory bias.

In the second and fifth waves of the welfare perception survey, the sample was composed of the household head and/or their spouse, rather than all household members, which raised issues regarding representativeness. To address this issue, in the eighth wave, a survey was conducted on all household members aged 19 and older from 2399 households (6248 individuals), which were selected using a stratified probability-proportional-to-size sampling method based on region and class from the entire seventh wave sample. In the eleventh wave welfare perception supplementary survey, 3634 household members from 2121 households (out of the 2399 households that participated in the eighth wave) were included in the sample [22]. In this study model, data from 1452 individuals aged 65 and older as of 2012 were analyzed.

The International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and the welfare perception survey of the Korean Welfare Panel, which is similarly structured, ask respondents about government responsibility, while explicitly stating that their responses may result in increased tax burdens. This is designed to mitigate the issue of respondent inconsistency by structuring survey questions to make respondents aware that their choices may lead to additional personal costs, thus providing practical implications. By premising the potential for personal financial burden, the welfare perception survey asks about the necessity of expanding the government’s active role in specific policy areas, such as child and family support. This approach reduces the likelihood of inconsistent responses and is an effective method for measuring welfare attitudes. Therefore, this study utilizes the relevant questions from the survey as welfare perception measurement items.

※

Please indicate whether you would like government spending in each of the following areas to increase or decrease. Please keep in mind that if spending increases significantly, it may require higher taxes. [Area: Support for families with children]

|

3.2. Analytical Model

Over the past decade, South Korea’s welfare state has experienced unprecedented expansion, particularly in policies designed to support both older and younger generations. Programs such as the Basic Old-Age Pension (2008), Long-Term Care Insurance (2008), and the Basic Pension (2014) have significantly broadened coverage for older adult citizens. Simultaneously, family policy has grown through initiatives like the universal childcare system (2014). This rapid and bifurcated policy evolution has created what Woo [23] refers to as a quasi-experimental environment—a context in which policy changes occur suddenly and exogenously, allowing researchers to compare outcomes across affected and unaffected groups in a manner akin to experimental design [23].

To empirically evaluate the influence of extended self-interest on welfare preferences among the older adults in a quasi-experimental environment, this study adopts a difference-in-differences (DiD) analytical framework. The core strategy involves comparing changes in attitudes toward child and family policy between 2013, a period of rapid policy change in the child and family support sector, and 2016 across two distinct subgroups within the older adult population: those who co-reside with children aged 0–17 (hereafter, the Co-residing Older Adults) and those who do not (the Non-co-residing Older Adults).

The decision to use co-residence status as the grouping variable is rooted in the theoretical argument that physical and relational proximity to younger generations can activate extended self-interest. In many cases, when older adult individuals in Korea co-reside with children aged 0 to 17, it is more likely that the children are their grandchildren rather than their own children. This suggests that such households are either grandparent–grandchild households or extended families. Older adults living with children are more likely to observe or participate in caregiving routines and directly experience the benefits or shortcomings of family policy. Thus, their policy preferences may reflect not only their own material self-interest but also the perceived needs of their co-residing family members While co-residence does not guarantee emotional intimacy or reciprocal support, it often reflects closer physical proximity, shared responsibilities, and embedded family roles that may activate relational dimensions of self-interest. As such, it is used here as a proxy for extended self-interest within the constraints of the KOWEPS dataset.

The DiD model estimates the average treatment effect of policy reform (i.e., the introduction of universal free childcare in March 2014) by interacting a time dummy (post-treatment: 2016 = 1, 2013 = 0) with a group dummy (Co-residing Older Adults = 1, Non-co-residing Older Adults = 0). The dependent variable is measured as support for increased government spending on families with children, recorded on a 5-point Likert scale and reverse-coded to ensure higher values reflect stronger support.

The analytical equation is formally represented as:

where:

: policy support score for individual i at time t

: 1 if individual i is Co-residing Older Adults, 0 otherwise

Postt: 1 if year is 2016, 0 if 2013

: vector of control variables (income, education, gender, ideology)

: error term

The coefficient on the interaction term captures the DiD estimate: the differential change in support for family policy attributable to both co-residence and exposure to the reform.

Control variables are included to account for potential confounders that influence welfare attitudes. Prior studies have shown that income and education are associated with redistributive preferences, while gender and ideology shape normative views about the state’s role. Including these variables helps isolate the specific influence of intergenerational co-residence.

While group assignment is not random, the panel structure of the KOWEPS dataset and the exogenous policy shift in 2014 enhance the plausibility of causal interpretation. Robustness checks using subsample regressions and alternative specifications are addressed in the empirical section that follows.

4. Results

This section empirically explores whether the presence of intergenerational solidarity within families—particularly through co-residence—may attenuate potential sources of generational conflict. Specifically, the analysis investigates whether life-cycle-based self-interest among older adults expands to include the welfare of younger family members [8,10]. If differences in welfare attitudes are observed based on co-residence status, even in the absence of significant policy effects, such findings may suggest that familial ties mediate how individuals perceive welfare needs across generations, offering a nuanced perspective on the “conflict intensification theory which argues that the expansion of welfare policies exacerbates intergenerational conflict. This is because welfare perceptions are shaped not solely by individual generational interests but by considering the interests of household members from other generations.

If each generation develops welfare perceptions solely based on their self-interest, the development of welfare systems could provoke intergenerational conflict. However, if welfare preferences are shaped by considering the interests of other family members, and policy preferences influence these perceptions, the expansion of welfare systems might narrow intergenerational perception gaps. This study utilizes data from the Welfare Perception Supplementary Survey of the Korean Welfare Panel Study to validate whether the mechanism of “conflict mitigation theory” holds in this context.

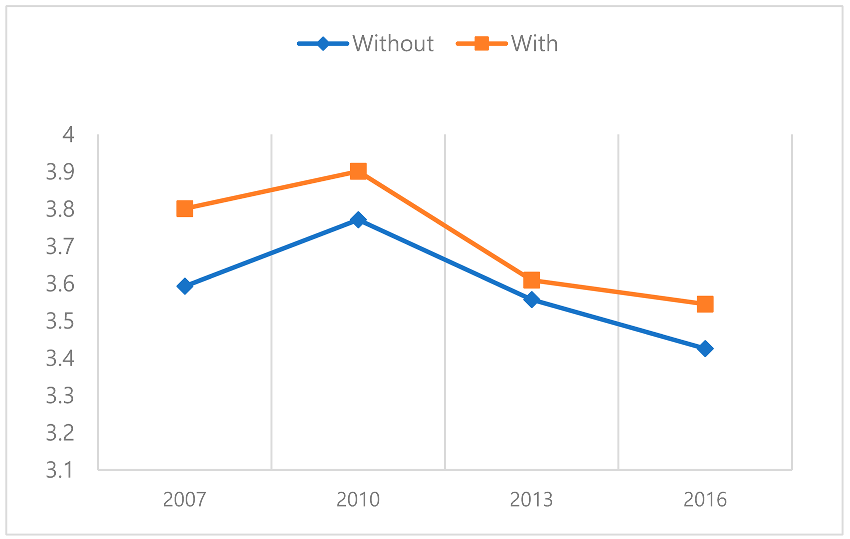

The Table 1 below presents the mean and standard deviation of perceptions of “government responsibility” in supporting families with children among the older adult generation, categorized by the presence of “extended self-interest,” for the years 2007, 2010, 2013, and 2016. The original survey scale ranged from 1 (“spending should increase significantly”) to 5 (“spending should decrease significantly”). For analytical convenience, the values were reverse-coded, so higher mean values indicate stronger support for increased government financial responsibility in the respective area.

Table 1.

Comparison of support for families with children between older adult households with and without children (2007–2016).

Let us examine the subgroup comparisons within the older adult generation. The category “with children in the household” refers to households where the respondent lives with children or adolescents aged 0–17. Among older adult respondents, those with children in the household accounted for 107 cases (7.4%) in 2013 and 56 cases (4.7%) in 2016. The subgroup of older adult individuals with children in the household showed a stronger preference for an active government role in the childcare sector compared to those without children in both 2013 and 2016. However, as not all differences shown in the table are statistically significant, it is necessary to examine how the “extended self-interest” mechanism operates using a difference-in-differences model.

The perception changes among older adult individuals considered to have a lower preference for “support for families with children” are analyzed. Table 1 presents the perceptions of “support for families with children” among older adult individuals with and without children in their households, across three pre-policy-change periods (2007, 2010, and 2013) and one post-policy-change period (2016). The older adult generation is defined as individuals aged 65 and older, a group whose self-interest typically aligns with policies for income security in retirement, such as pensions. Within this generation, respondents were divided into those with children aged 17 or younger in their households and those without. The study compares group differences and policy effects within the older adult generation.

Although older adult respondents are not directly affected by childcare or child-rearing policies, if significant differences in perceptions or policy effects are observed between those with and without children in their households, and if those with children demonstrate a stronger preference for an active government role in childcare, this would indicate the influence of “extended self-interest” in shaping welfare perceptions. For this analysis, the older adult generation with children in their households serves as the program group, while those without children serve as the control group. Given that the policy change occurred in 2014, the parallel trend assumption was tested by examining changes in perception averages across three pre-policy periods: 2007, 2010, and 2013.

The comparison of the two groups revealed that at all three time points—2007, 2010, and 2013—the level of agreement among the program group (“older adult households with children”) was higher than that of the control group. Although the trajectories of change between the two groups were not entirely parallel, the differences in directional trends were minimal. Thus, common trends were addressed by incorporating control variables. Additionally, to verify the exogeneity of the treatment, control variables were sequentially included to examine whether policy effects and period effects varied. While overall support decreased modestly over time, the relative difference between the two groups persisted, suggesting that intergenerational co-residence is associated with stronger endorsement of child-oriented policy.

The difference-in-differences regression model evaluated whether this relative gap widened or narrowed following the 2014 policy expansion. The key interaction term (Group × Post) captured the differential change between the Co-residing and Non-co-residing groups. However, the coefficient on the interaction term was statistically insignificant across all model specifications (see Table 2). This indicates that while the Co-residing Older Adults consistently showed more favorable attitudes, the policy reforms did not significantly alter this pattern. In other words, co-residence appears to influence the level—but not the responsiveness—of policy support. While the interaction term capturing the policy effect was statistically insignificant, this does not necessarily imply that the 2013 reform had no impact. Rather, the consistently higher levels of support for childcare among co-residing older adults may reflect a deeply rooted value orientation shaped by enduring familial norms and intergenerational obligations. These attitudinal predispositions appear to be relatively stable and less susceptible to short-term policy stimuli, suggesting that extended self-interest functions more as a structural orientation than a dynamic reaction. Indeed, recent Korean studies highlight the central role of co-residence and filial piety in reinforcing pro-childcare attitudes among older populations [24,25].

Table 2.

DID results: ‘childcare support’ among older adults with/without children.

To evaluate the comparability of the treatment and control groups prior to the policy reform, we conducted a balance test using 2012 data. Statistically significant differences were found between Co-residing and Non-co-residing Older Adults in terms of income status (p < 0.001), gender (p = 0.020), and years of education (p = 0.023). No significant difference was observed in political ideology (p = 0.112). These results suggest that co-residence status is not randomly distributed and may be associated with certain background characteristics, highlighting the potential for selection bias. To account for these differences, all relevant covariates were included in the DiD regression model. I also conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis using 2013 data. Older adults who co-resided with younger kin were matched to similar individuals who did not, based on income level, political ideology, gender, and education. The matched sample (n = 83 pairs) revealed that co-residing older adults expressed significantly higher support for childcare policies (t = 2.68, p = 0.008). A regression analysis on the matched sample confirmed this association (β = 0.288, p = 0.006), even after adjusting for covariate differences. These results provide additional support for the extended self-interest hypothesis and further strengthen the internal validity of the identification strategy. A more detailed application of causal inference methods, including PSM, will be explored in a separate study.

Models 1 through 5 compare the perception changes within the older adult generation, specifically between “older adult households with children” and “older adult households without children”. In all five models, where control variables were progressively added, both the period effects and the baseline preferences of the treatment group were statistically significant. The control variables were introduced to account for potential heterogeneity between the two groups. The stability of period effects and baseline preferences, as well as their statistical significance after the inclusion of control variables, suggests that the assumption of treatment exogeneity—a key requirement of the difference-in-differences analysis—was upheld.

Additional regression results offer further insight. The baseline preference (Group_i) coefficient was positive, reaffirming that Co-residing Older Adults were more supportive even prior to the reform. Meanwhile, the time effect (Post_t) was negative and statistically significant, suggesting an overall decline in support for childcare policy across the older adult population between 2013 and 2016. Among control variables, income level showed a significant negative relationship with support for child and family spending. This conservative trend has been noted in recent studies on Korean attitudes toward welfare [26,27], and it appears to have emerged in the context of ideological debates between universal and means-tested welfare that have taken place in the political sphere since the 2010s. It should also be considered alongside the finding that low-income older adults show lower levels of support for child welfare, which seems to be due to the perception that as selectivity increases, their own likelihood of receiving benefits may rise—despite the fact that the poverty rate for older adults in Korea reaches 40% [27,28]. Older adult individuals with lower income expressed lower support, possibly due to competing resource demands or a stronger focus on old-age benefits. Political ideology, education, and gender were not significant predictors in most models, indicating that household composition had a stronger explanatory power for the attitudes in question.

To assess the validity of the main findings, a placebo test was conducted using data from 2010 and 2013, prior to the full implementation of universal childcare in 2014. No statistically significant differences were found between the treatment and control groups in 2010, and the interaction term representing the policy effect was also not significant. This confirms that there was no spurious treatment effect in the pre-reform period, thereby supporting the parallel trends assumption and enhancing the internal validity of the identification strategy. These results further support the credibility of the DiD design.

Taken together, these findings provide partial support for the extended self-interest hypothesis. Co-residing Older Adults demonstrate higher average support for family-oriented welfare programs, consistent with the idea that proximity to younger generations broadens the perceived scope of relevant policy beneficiaries. However, this orientation does not appear to change in response to short-term reforms, suggesting that extended self-interest functions more as a stable predisposition than a flexible reaction to policy shifts.

These findings offer both empirical and theoretical implications. Empirically, they highlight the relevance of household structure as a determinant of welfare attitudes among older adults. Theoretically, they offer tentative support for the idea that extended self-interest may foster intergenerational solidarity—not through immediate responsiveness to policy change, but as a relatively stable orientation shaped by family composition and cultural norms.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined whether and how intergenerational co-residence influences older adult attitudes toward family and childcare policy through the conceptual lens of extended self-interest. Drawing on longitudinal panel data from KOWEPS and employing a difference-in-differences design, the analysis found that older adult individuals living with children consistently expressed higher support for government spending on families relative to those who did not co-reside. However, the 2014 childcare reforms did not produce a statistically significant shift in attitudes among the co-residing group, suggesting that extended self-interest may reflect a relatively stable predisposition shaped by family structure rather than a dynamic or policy-sensitive orientation.

These findings contribute to ongoing debates about the sources of welfare state preferences in aging societies. While much of the existing literature highlights the growing cleavage between age cohorts, often interpreted as a zero-sum conflict between old and young [29], this study offers preliminary evidence that intergenerational solidarity may persist in certain family contexts. The higher average support for childcare policy among co-residing older adults suggests that under certain conditions, self-interest may extend beyond one’s own age cohort, particularly when close kinship ties are present.

More importantly, the findings of this study suggest a conceptual expansion of how self-interest is defined in the context of welfare attitudes. Contrary to the dominant assumption in the literature that self-interest is structured by one’s own life-cycle position or generational identity [30], this study finds that older adult individuals in Korea do not confine their welfare preferences to the needs of their own age group. Instead, those who co-reside with younger kin appear to take into account the needs and interests of other generations within the family. In this sense, the boundaries of “self” are extended to encompass relational others, including grandchildren or younger dependents. This relational reframing of self-interest challenges the assumption that policy preferences are narrowly egoistic and age-bound [30,31], opening new directions for theorizing welfare attitudes in multigenerational households.

Nevertheless, the null policy effect observed in the DiD analysis warrants attention. One possible explanation is that family-based attitudes are more deeply rooted in cultural and relational norms than in policy feedback mechanisms. In the Korean context, where filial piety and multi-generational caregiving are culturally embedded, co-residence may signal a durable value orientation rather than a flexible attitudinal response. This distinction is important for understanding both the potential and the limits of family-based solidarity as a basis for welfare state consensus.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size for the Co-residing Older Adults group—particularly in 2016—may have reduced statistical power. Second, the use of co-residence as a proxy for extended self-interest does not capture the full range of intergenerational support mechanisms, such as financial transfers or emotional caregiving among non-cohabiting kin. While this study uses co-residence as a structural indicator of extended self-interest, it does not assume that cohabitation alone is sufficient to capture the full complexity of intergenerational motivation. Rather, it serves as a proxy for potential interdependence, acknowledging the conceptual distinction between physical proximity and relational intent. Third, while this study introduces the concept of extended self-interest, it does not fully distinguish it from related notions such as ‘kin altruism’ or ‘indirect reciprocity’. These biologically grounded theories remain underexplored in welfare policy research and merit further investigation in future work.

Future research could build on these findings in several directions. Mixed-methods approaches incorporating qualitative interviews could explore how older adult individuals narrate their sense of responsibility toward younger generations. Cross-national comparative studies could examine how institutional context moderates the relationship between family structure and welfare preferences. Longitudinal designs with more granular data could help clarify whether extended self-interest is stable over time or sensitive to cumulative policy exposure.

In sum, this study advances the understanding of how intergenerational relationships shape welfare attitudes. While extended self-interest may not respond strongly to short-term reforms, it nonetheless plays a meaningful role in fostering solidarity across generations. Recognizing and leveraging these relational foundations—especially the expanded conception of self-interest—may be crucial for building sustainable welfare coalitions in an aging society.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023S1A5A8079810).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study can be downloaded from the Korea Welfare Panel (https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/eng/main.do). (accessed on 1 January 2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brooks, C.; Manza, J. Social policy responsiveness in developed democracies. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häusermann, S. The Politics of Welfare State Reform in Continental Europe: Modernization in Hard Times; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busemeyer, M.; Goerres, A.; Weschle, S. Attitudes towards redistributive spending in an era of demographic ageing: The rival pressures from age and income in 14 OECD countries. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C.; Williamson, J.B. Age structure, politics, and cross-national patterns of public pension expenditures. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1985, 50, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenberg, P. Children in an aging society. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eun, S. The Relationship between the Expansion of Welfare Institution and Generational Conflict. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Social Welfare, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Albertini, M.; Kohli, M.; Vogel, C. Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: Common patterns–different regimes? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2007, 17, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Incomplete Revolution: Adapting Welfare States to Women’s New Roles; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlikoff, L.J.; Burns, S. The Coming Generational Storm; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S.H. Children and the older adults: Divergent paths for America’s dependents. Demography 1984, 21, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonoli, G.; Häusermann, S. Who wants what from the welfare state? Socio-structural cleavages in distributional politics: Evidence from Swiss referendum votes. Eur. Soc. 2009, 11, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmanen, P.; Szebehely, M. From the state to the family or to the market? Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2015, 24, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Lee, J.M. Childhood poverty in Korea: The characteristics and effect on youth. Health Welf. Policy Forum 2017, 12, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.S. Developmental state, welfare state, risk family: Developmental liberalism and social reproduction crisis in South Korea. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2011, 18, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, N.H.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, C.M. Study on Demographic Change and Public-Private Transfer Division Status; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goerres, A.; Tepe, M. Age-based self-interest, intergenerational solidarity and the welfare state: A comparative analysis of older people’s attitudes towards public childcare in 12 OECD countries. Eur. J. Political Res. 2010, 49, 818–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. Post-industrial pressures on the mature welfare states. In The New Politics of the Welfare State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 80–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kersbergen, K.; Vis, B. Comparative Welfare State Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev, M. The social democratic model and beyond. Comp. Soc. Res. 1983, 6, 315–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ponza, M.; Duncan, G.J.; Corcoran, M.; Groskind, F. The guns of autumn? Public Opin. Q. 1988, 52, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Kim, T.W.; Oh, M.A.; Park, H.J.; Shin, J.D.; Jung, H.S.; Ham, S.Y. The 2016 Korea Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS): Descriptive Report; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.-J. STATA for Policy Evaluation; Jiphil Media Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Jung, K.H. Welfare service policies in 2010: Its issues and prospects. Health Welf. Policy Forum 2010, 1, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. Welfare attitudes in Korean society: Effects of cohort and social exclusion. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2024, 32, 236–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C. Does the Welfare Perception Make Difference in Political Party Support?: Differences in Welfare Perceptions by Party Support Class and the Effects of Welfare Perceptions on Party Support. J. Crit. Soc. Welf. 2022, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Kim, J. The effects of intergenerational program on solidarity and perception to other generations in Korea. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2021, 47, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Yeo, E.G. How are Koreans’ welfare attitudes changing? Korean Soc. Secur. Assoc. Conf. Proc. 2015, 2, 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlikoff, L.J.; Rosenthal, R.W. Some inefficiency implications of generational politics and exchange. Econ. Politics 1993, 5, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.T. An exploration of actions of filial piety. J. Aging Stud. 1998, 12, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, A.; Keck, W.; Alber, J. Family and the Welfare State in Europe: Intergenerational Relations in Ageing Societies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).