Abstract

This article examines the relevance of Smart Specialisation Strategies (RIS3) in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions, using Poland’s Lubusz Voivodeship as a case study. Based on employment data from 2009 and 2021, this study uses Location Quotient (LQ) analysis to evaluate the alignment between the region’s economic structure and its RIS3 domains: Innovative Industry, Health and Quality of Life, and Green Economy. The findings show that while Innovative Industry and Health and Quality of Life strengthened their relative specialisation, the Green Economy domain made only limited progress. Notably, sectors such as metal fabrication and social care services emerged as new specialisations, while several traditional industries declined. These results support the hypothesis that RIS3 priorities only partially reflect endogenous economic strengths, and they highlight the challenges of implementing innovation strategies in territorially fragmented and capacity-constrained regions. This article calls for dynamic priority reviews, improved multi-level coordination, and targeted instruments to better align RIS3 frameworks with the structural realities of “in-between” regions in the EU.

1. Introduction

The European Union’s Smart Specialisation Strategy (RIS3) has become a cornerstone of cohesion policy, aiming to foster innovation-driven development by aligning regional potential with targeted investments. Central to this approach is the assumption that regions—regardless of their development level—possess unique strengths that can be unlocked through place-based, evidence-informed strategies. However, the effectiveness of RIS3 largely depends on how well the selected specialisations correspond to the socio-economic context and structural conditions of a given region.

This article focuses on the Lubusz Voivodeship (Lubuskie) in western Poland—a region that, despite its central location within the European Union and along major transport corridors, faces persistent challenges related to limited innovation capacity, institutional fragmentation, and a dispersed urban structure. Drawing on typological insights from ESPON and the recent cohesion literature, Lubuskie is conceptualised here as a structurally weak but non-peripheral region—a territory that is geographically central yet structurally marginalised in terms of economic dynamism and absorptive capacity.

Such regions are not unique. Across the EU, there is a broader category of structurally weak yet strategically located territories that are often overlooked in cohesion and innovation policy frameworks. Examples include Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Germany, Molise in Italy, Limousin in France, and the Świętokrzyskie and Opolskie Voivodeships in Poland. Despite their proximity to major economic centres, these regions lack strong metropolitan anchors and struggle to convert spatial advantage into development momentum.

This conceptual framing offers a critical lens for evaluating RIS3 choices. In structurally weak regions, innovation priorities may be shaped more by external expectations or aspirational policy goals than by genuine economic specialisation. As such, the risk of strategic misalignment between RIS3 documents and the actual structure of the regional economy is heightened.

To examine this hypothesis, this article applies a methodology adapted from Kudełko, Żmija, and Żmija [1], which analyses changes in regional employment structures using the Location Quotient (LQ) method. Employment data from two time points—2009 (pre-RIS3) and 2021—are used to assess whether the selected smart specialisations have a solid economic base and whether their relative position has improved or weakened over time.

By focusing on a region that does not neatly fit core–periphery models and is often excluded from mainstream cohesion debates, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of RIS3’s applicability in fragmented and structurally constrained contexts. The findings may also be of interest to policymakers and researchers working with similar structurally weak but non-peripheral regions across Europe, where the place-based logic of innovation policy must be balanced with limited regional capacity.

The central research question addressed in this article is as follows:

To what extent do the RIS3 priorities in the Lubusz Voivodeship reflect the actual structure and dynamics of its regional economy?

To explore this question, this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations of smart specialisation and regional typologies. Section 3 presents the research design, including this study’s aims, guiding questions, hypotheses, and methodological approach. Section 4 offers a regional profile of Lubuskie, with emphasis on its territorial fragmentation and institutional constraints. Section 5 presents the empirical findings based on dynamic Location Quotient (LQ) analysis. Section 6 discusses the implications for RIS3 implementation and policy design in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions. Section 7 concludes with key findings and recommendations for further research and regional policy.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Smart Specialisation Strategies (RIS3) and the Place-Based Approach

The Smart Specialisation Strategy (RIS3) emerged from the European Commission’s commitment to foster regional innovation through place-based and evidence-informed development. RIS3 encourages regions to identify priority areas where they hold a comparative advantage, and to direct public investments accordingly. Its conceptual foundation draws on the work of Foray et al. [2] and the Barca Report [3], emphasising endogenous development, stakeholder participation, and entrepreneurial discovery. While widely adopted in EU cohesion policy, RIS3 has also been critiqued for favouring more developed or institutionally mature regions that are better positioned to implement complex innovation strategies.

Critics argue that lagging or structurally weaker regions often lack the institutional capacity, entrepreneurial base, and innovation networks needed to effectively operationalise RIS3. As a result, the strategy may unintentionally reinforce existing territorial disparities rather than reduce them [4,5,6].

2.2. Typologies of European Regions: Core–Periphery and Beyond

Traditional regional typologies, such as the core–periphery model, distinguish between high-performing metropolitan centres and economically weaker peripheral areas. However, the recent literature [7,8,9,10] has identified a growing number of regions that do not neatly fit these binary categories. These territories often suffer from inadequate infrastructure, fragmented governance, and limited institutional capacity, despite being geographically close to major economic centres. They typically fall outside the scope of both metropolitan-focused policies and those targeting peripheral areas, resulting in systematic neglect within regional development strategies. Examples include border areas in northeastern Germany, parts of central Italy and eastern France, and—within Poland—the Lubusz Voivodeship.

Building on these insights, a growing body of peer-reviewed literature has advanced the theoretical understanding of regions that fall outside conventional core–periphery models. Tödtling and Trippl (2005) [10] proposed a differentiated model of regional innovation systems, emphasising that “one-size-fits-all” approaches overlook the needs of structurally weak regions that are neither innovation leaders nor typical laggards. Rodríguez-Pose (2018) [6] introduced the notion of “places that don’t matter,” arguing that even centrally located regions can become economically and politically marginalised if they lack an institutional voice and viable development paths. Grillitsch and Asheim (2018) [11], along with Barzotto et al. (2019) [5], stress the importance of regional context and institutional capacity in shaping innovation outcomes—particularly in regions situated between high-performing cores and disadvantaged peripheries.

Analyses by ESPON [7,8] suggest that categories such as inner peripheries and sideways innovation-poor regions encompass a significant number of NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 territories in Central and Eastern Europe. These regions are characterised by limited infrastructure access, weak integration into national innovation systems, and dispersed settlement patterns. Similarly, the OECD [9] introduced the concept of non-core or near-core peripheral regions, highlighting the growing spatial inequality risks faced by these “in-between” territorial types. These typologies offer a valuable analytical lens for assessing the relevance and limitations of RIS3 strategies in regions such as Lubuskie.

2.3. The RIS3 Challenge in Structurally Constrained Regions

Empirical studies on RIS3’s implementation in less-developed regions [11,12] highlight the difficulties of aligning innovation strategies with actual economic structures and institutional capacity. Structurally weak regions face challenges such as limited stakeholder engagement, insufficient data, and aspirational policies that often lack empirical grounding. This raises the question of whether RIS3 can truly function as a place-based policy when the place in question lacks the necessary conditions for discovery and specialisation.

In many such regions, entrepreneurial discovery processes are hindered by fragmented governance, weak innovation cultures, and a lack of intermediary institutions capable of facilitating coordinated action. The resulting strategic documents often reflect national or global trends rather than local realities, leading to “copy–paste” specialisation domains with little endogenous foundation. Moreover, limited absorptive capacity can constrain the region’s ability to benefit from knowledge spillovers, further weakening RIS3’s transformative potential.

In this context, the challenge lies not only in designing Smart Specialisation Strategies but in making them feasible and effective within structurally constrained environments. As the recent literature suggests, RIS3 should be reconsidered for these regions—not as a standardised framework, but as a flexible, capacity-building instrument that acknowledges local limitations while enabling external support and cross-regional collaboration [5,13].

2.4. Theoretical Framework and Research Gap

Despite the strategic importance of RIS3, relatively little attention has been paid to how Smart Specialisation Strategies operate in structurally weak yet non-peripheral regions. The case of Lubuskie offers an opportunity to address this gap by combining a theoretical framing based on regional typologies with a quantitative analysis of sectoral employment dynamics. By adapting the LQ-based approach proposed by Kudełko et al. [1], this study seeks to evaluate whether the RIS3 priorities adopted in Lubuskie reflect its actual economic structure, as well as what this may imply for other similarly positioned regions in the EU.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Objective and Hypotheses

The aim of this study is to evaluate the extent to which the Smart Specialisation Strategies (RIS3) adopted in the Lubusz Voivodeship correspond to the actual structure and evolution of its regional economy. Using employment data from 2009 (pre-RIS3) and 2021 (the latest comparable year), the analysis investigates whether the designated specialisation domains are empirically anchored in the region’s economic base. The central research question is as follows:

This study aims to assess the extent to which the RIS3 priorities in the Lubusz Voivodeship reflect the actual structure and dynamics of its regional economy.

To address this question, this study considers three guiding sub-questions: How has the regional employment structure evolved between 2009 and 2021? Do the sectors associated with the adopted RIS3 domains show increased or decreased relative specialisation? What barriers and enabling mechanisms have influenced these dynamics?

This inquiry is guided by the hypothesis that the RIS3 domains in the Lubusz Voivodeship only partially align with the region’s actual economic specialisations. These priorities may have been influenced more by aspirational objectives or external policy frameworks than by endogenous strengths.

The hypotheses are formulated as follows:

H1.

The selected RIS3 priorities in the Lubusz Voivodeship do not fully reflect the region’s existing economic specialisations.

H1a.

At least one sector classified under an RIS3 domain will exhibit a declining or stagnant Location Quotient (LQ) between 2009 and 2021, indicating weak empirical support.

H1b.

At least one sector not explicitly included among the RIS3 priorities will show significant LQ growth, suggesting overlooked endogenous potential.

H1c.

The Green Economy domain will show the weakest alignment with structural employment trends, due to limited institutional and innovation capacity in the region.

These testable hypotheses are assessed using Location Quotient analysis to compare sectoral concentration levels before and after RIS3’s adoption. In doing so, this study contributes to the broader debate on how Smart Specialisation Strategies can be adapted to the complex realities of structurally constrained regions.

3.2. Data and Methods

This study applies a quantitative and comparative research design to assess the structural coherence between the Smart Specialisation Strategies (RIS3) of the Lubusz Voivodeship and its actual economic profile. The analysis draws on employment data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS), specifically the Z-06 statistical report on employment by sector. Data are aggregated at the 2-digit level of the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD 2007), which is harmonised with the NACE Rev.2 classification system, ensuring consistency and comparability across time and territorial units.

The year 2009 is used as the baseline, as it precedes the adoption of the RIS3 strategies and coincides with the introduction of PKD 2007. The year 2021 serves as the end point, as a methodological shift in employment reporting occurred in 2022, limiting comparability with subsequent data. This two-point time frame enables longitudinal comparison while preserving data coherence.

To identify regional economic specialisations, the Location Quotient (LQ) method is applied. LQ is a widely recognised tool in regional analysis, used to determine the relative concentration of sectoral employment in a given region compared to the national average. It is particularly suitable for structurally weak regions, where more complex innovation indicators—such as R&D expenditure, patent intensity, or firm-level innovation—are often unavailable or incomplete [1,9]. LQ is calculated using the following formula:

where

- —Number of employees in sector i in the Lubusz Voivodeship;

- —Total number of employees in the Lubusz Voivodeship;

- —Number of employees in sector i in Poland;

- —Total number of employees in Poland.

An LQ > 1 indicates an above-average regional concentration in a given sector. Following established research [1,9], this study applies an LQ threshold of 1.25 to denote strong or emerging specialisation.

The methodology builds on the approach developed by Kudełko, Żmija, and Żmija [1], who used LQ analysis to assess RIS3 alignment in Polish regions. It is also informed by previous studies that highlight LQ as a reliable proxy for identifying structural strengths in regions with limited access to high-resolution innovation data [9]. In the context of structurally weak but non-peripheral regions—such as Lubuskie—this analytical tool enables empirically grounded comparisons of sectoral performance over time.

To ensure methodological transparency, only sectors with available data for both 2009 and 2021 are included. While the LQ method does not capture the full complexity of innovation dynamics, it remains one of the few robust and longitudinal indicators available at the regional level, and it is widely used in both policy and academic research [1,9].

3.3. Limitations

While the Location Quotient (LQ) method offers a pragmatic and consistent approach to analysing regional specialisation, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged.

First, the analysis relies exclusively on employment data aggregated at the 2-digit PKD level, which—while reliable—does not capture intra-sectoral dynamics, value added, productivity, or innovation intensity. As a result, this study may underrepresent the complexity of economic activity within broader sectoral categories.

Second, the use of only two temporal reference points (2009 and 2021) limits the ability to identify short-term fluctuations, cyclical effects, or delayed policy responses. Although these years were selected for reasons of data comparability, they offer a static snapshot of structural change rather than a continuous trend. This reflects the nature of LQ as a relative indicator of regional concentration, not a dynamic time-series tool.

Third, although the LQ method is widely used in regional development research [1,9], it remains a proxy that does not fully account for institutional capacity, entrepreneurial activity, or innovation networks—all of which are critical to successful RIS3 implementation. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as indicators of structural alignment, not as comprehensive measures of innovation performance.

Finally, this study does not include firm-level or qualitative data on stakeholder engagement, entrepreneurial discovery processes (EDPs), or governance mechanisms. While these dimensions are discussed in the final section, further research is needed to integrate such factors into a more holistic assessment of smart specialisation in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions.

4. Contextualising Lubuskie as a Structurally Weak but Central Region

4.1. Geographical and Institutional Fragmentation

Lubuskie is one of the few Polish regions with a dual-capital structure, split between Zielona Góra and Gorzów Wielkopolski. This arrangement, introduced during the 1999 administrative reform, has led to fragmented governance and weakened strategic cohesion [14]. The two cities operate largely independently, hindering integrated planning and reducing the effectiveness of region-wide innovation initiatives.

This dual-capital configuration, combined with limited regional coordination and weak innovation linkages, positions Lubuskie within the broader category of structurally weak but non-peripheral regions. Similar patterns of institutional fragmentation and low absorptive capacity have been documented in other EU territories, including Sachsen-Anhalt (Germany), Friuli Venezia Giulia (Italy), and Lorraine (France), which likewise struggle to align smart specialisation priorities with regional capabilities and governance frameworks [5,11].

4.2. Lubuskie in the National and Macro-Regional Landscape

Geographically, Lubuskie lies along key trans-European transport corridors and borders Germany, but institutionally it is overshadowed by neighbouring regions such as Lower Silesia and Greater Poland [15,16]. The absence of a strong urban growth centre limits competitiveness, investment retention, and visibility within national policy frameworks [17]. As a result, Lubuskie occupies a liminal position: neither core nor peripheral in spatial terms, yet functionally marginal—a pattern also observed in other “intermediate” regions across the EU [9].

4.3. ESPON Classifications and Territorial Typologies

ESPON classifications reflect this hybrid status. The northern part of the region (Gorzów) is classified as a “Sideways Innovation-Poor Region,” while the southern subregion (Zielona Góra) is labelled as “Not an IP Region” [18,19]. These designations indicate minimal participation in innovation networks and weak institutional anchoring—challenges characteristic of structurally weak but non-peripheral regions [20].

4.4. Initial Conditions for RIS3 Implementation

At the outset of RIS3 programming, Lubuskie faced persistent challenges: among the lowest levels of R&D expenditure in Poland, weak inter-institutional coordination, and fragmented stakeholder engagement [14,21]. Entrepreneurial discovery mechanisms struggled to take hold, and the dual-governance model made it difficult to consolidate regional innovation agendas. According to the ex ante evaluation of the Lubuskie ROP for 2021–2027, green innovation was particularly underfunded, with most support directed toward technical assistance rather than transformative R&D [14].

5. Results

Table 1 presents the computed Location Quotients (LQs) for each two-digit PKD sector in Lubuskie for 2009 and 2021, along with the change (ΔLQ = LQ(2021)–LQ(2009)). An LQ > 1 indicates that a sector is relatively more concentrated in Lubuskie than in Poland as a whole, while a ΔLQ > 0 signals an increase in relative specialisation over the 12-year period. The objective of this section is to identify sectors that have undergone significant shifts—either positive or negative—in their relative specialisation during the analysed period.

Table 1.

LQ 2009, LQ 2021, and ΔLQ for Lubuskie by PKD (selected sectors) 1.

Rather than interpreting the LQ results in isolation, the findings are examined in the context of broader socio-economic and institutional dynamics. The analysis is structured around the three priority domains identified in the region’s Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation (RIS3), adopted in 2019: (1) Innovative Industry, (2) Health and Quality of Life, and (3) Green Economy. Each sub-section highlights key trends, evaluates the coherence between observed developments and policy priorities, and considers potential explanatory factors such as political support, regional demand structures, and institutional constraints.

The LQ analysis reveals that sectoral specialisation in Lubuskie between 2009 and 2021 was characterised by selective and uneven dynamics. Among the sectors that increased their regional concentration were metal fabrication (C25) and social care services (Q87), both of which recorded notable LQ gains exceeding the national average. The former reflects continuity with the region’s traditional industrial capacities, while the latter suggests growing demand for care-related services and expanding employment in this domain.

A modest but consistent upward trend was also observed in sectors such as information and communication (J63) and professional, scientific, and technical services (M72, M74), indicating early signs of emerging knowledge-based activities. However, their LQ values remained below the 1.0 threshold, suggesting a limited but gradually increasing presence in the regional economy.

In contrast, several manufacturing sectors experienced a decline in relative specialisation. Notably, machinery and equipment (C28), automotive (C29), and chemicals (C20) showed decreasing LQ values, which may reflect structural adjustments, global value chain shifts, or insufficient regional support mechanisms.

Finally, the Green Economy domain showed only marginal improvement, with renewable-energy-related sectors failing to surpass the specialisation threshold. This indicates persistent barriers—such as infrastructural bottlenecks or regulatory inertia—that continue to hinder the transition to a low-carbon economy, despite strategic prioritisation in the RIS3 framework.

5.1. Sectoral Dynamics in the RIS3 Priority Domains

The following sub-sections provide a more detailed examination of sectoral dynamics within the three smart specialisation domains identified in the Lubuskie RIS3. For each domain, the evolution of selected sectors is analysed in relation to their LQ performance, as well as broader policy and market conditions.

5.1.1. Innovative Industry

Within the Innovative Industry domain, the sectoral specialisation trends in Lubuskie between 2009 and 2021 revealed significant variation. Current data show that the manufacturing of fabricated metal products (C25) is the most dynamically growing industrial sector in the region, with its LQ rising sharply from 0.14 to 1.52 (ΔLQ = +1.38). This expansion can be partially attributed to the relocation of simpler manufacturing processes from more technologically advanced and higher-cost western Polish regions, as suggested by the literature on global value chains and cost-based industrial relocation.

The OECD analysis highlights that Polish industry—including the metal sector—benefits from lower labour and energy costs compared to Western Europe, making it attractive to firms relocating parts of their production processes [22]. The westward concentration of metal production in Poland, supported by economic zones such as the Kostrzyn–Słubice SEZ, offers proximity to the German market while maintaining lower operating costs.

Moreover, analyses of Poland’s position in global value chains (GVCs) indicate that the “basic metals and fabricated metal products” domain (D24T25) has demonstrated strong regional competitiveness, suggesting that Lubuskie has been reinforcing its position in this sector—a trend clearly reflected in the rising LQ value [23]. Due to the relatively simple production processes and low technological sophistication, the region has likely attracted substantial investment by offering a competitive mix of low labour costs and geographical proximity—both domestic and cross-border. Support from economic zone institutions (e.g., the Kostrzyn–Słubice SEZ) and fiscal incentives has further strengthened this trajectory.

A notable LQ increase was also recorded in the furniture manufacturing sector (C31), where the index rose from 1.63 to 1.91 (ΔLQ = +0.28). This sector has long been a core part of Lubuskie’s industrial profile, benefiting from a relatively large pool of medium-skilled labour and strong integration with the German market. Its enduring role may reflect both industrial traditions and the persistence of cultural–occupational specialisations across Polish regions [24].

In contrast, the motor vehicle manufacturing sector (C29) experienced a clear decline in specialisation, despite maintaining a relatively high LQ (down from 3.16 to 2.30; ΔLQ = −0.85). Research by Domański et al. [25] links such changes to regional restructuring and shifts within value chains, especially where peripheral regions face shortages of skilled engineering staff and lack industrial infrastructure. Further studies suggest that automotive relocations to Poland were driven by logistics and cost advantages, but the absence of high-tech industrial hubs has limited the complexity of the transferred operations [26].

The wood products sector (C16), while showing a slight LQ decrease from 3.15 to 2.93 (ΔLQ = −0.22), remains highly specialised in Lubuskie. The region hosts many wood-processing SMEs, often located in rural or peri-urban areas with favourable access to raw materials and skilled labour. Sectoral resilience may also stem from continued domestic and export demand, particularly in relation to furniture supply chains.

A similar pattern is visible in leather and related products (C15), where the LQ increased modestly from 3.22 to 3.34 (ΔLQ = +0.12). Although modest, this growth indicates sustained niche production, possibly including contract manufacturing for foreign brands or regional specialities—consistent with broader decentralised textile and leather production trends across Central Europe.

Textile manufacturing (C13) experienced a minor decline in specialisation, with the LQ falling from 1.78 to 1.66 (ΔLQ = −0.12). Nevertheless, the sector maintains a relatively strong position, supported by local labour markets and inter-regional logistics. Its persistence is driven by small and medium-sized firms engaged in traditional textile production.

In computer, electronic, and optical products manufacturing (C26), the LQ declined from 2.57 to 2.23 (ΔLQ = −0.34), indicating a weakening of specialisation without a complete loss of regional relevance. According to a PAIH report [27], despite high labour productivity (146% of the industrial average) and stable employment (~63,700 persons), the sector faces growing technological demands—particularly in automation and Industry 4.0. Research by Gliń and Stasiak-Betlejewska [28] also shows that Polish firms—especially in electronics—are constrained by financial barriers and shortages of IT and automation specialists, limiting the scope of advanced technological adoption. The Emerging Europe Report [29] confirms that while firms in CEE continue to invest, digital transformation progresses mainly in large facilities, while SMEs lag behind due to limited access to IIoT specialists.

Finally, the LQ for computer programming, consultancy, and related services (J62) declined from 0.46 to 0.26 (ΔLQ = −0.20), indicating a gradual loss of regional relevance. Despite broader digitalisation trends in Poland and the EU, this sector has not (yet) emerged as a strength in Lubuskie. This may reflect the limited size of the local ICT workforce and the concentration of high-value digital services in larger urban centres, which undermines the competitiveness of smaller regions. Some of the challenges described for C26 may also indirectly affect J62, although further investigation is needed.

5.1.2. Health and Quality of Life

Within the domain of Health and Quality of Life, the data indicate a growing role for social and care services, accompanied by a relative decline in the healthcare sector’s share in regional employment. The most dynamic increase was observed in social work activities without accommodation (Q88), where the LQ rose from 0.13 to 1.41 (ΔLQ = +1.28). This shift likely reflects the rising importance of community-based services and demographic changes, including population ageing [30,31]. These developments align with both national and international recommendations to strengthen local long-term care systems, particularly in peripheral regions such as Lubuskie [32].

In residential care activities (Q87), a moderate increase in specialisation was recorded (ΔLQ = +0.14), likely supported by a well-established network of public and private care institutions, especially in smaller district towns. According to Statistics Poland, the number of places in social welfare homes and residential facilities has been steadily growing, particularly in less urbanised voivodeships [33].

In contrast, human health activities (Q86)—a domain prioritised in Lubuskie’s RIS3—recorded a decline in LQ from 0.93 to 0.83 (ΔLQ = −0.10), remaining below the national average. According to the OECD [34], Poland continues to face a shortage of medical personnel, driven by low graduation rates in the medical and nursing fields, workforce ageing, and emigration. In Lubuskie, only around 40% of medical graduates choose to complete their residency in local institutions, underscoring the region’s limited capacity to attract and retain healthcare professionals [35].

According to the Ministry of Health [36], 15 entities provided inpatient services in Lubuskie, offering a total of 3890 hospital beds—equivalent to 38.09 beds per 10,000 inhabitants, one of the lowest rates in the country (national average approx. 44.6). Despite these structural limitations, some notable local progress has been made—for instance, the transformation of the Multispecialist Regional Hospital in Gorzów Wielkopolski, which has implemented several innovative infrastructural and medical upgrades [37].

At the national level, numerous health infrastructure projects have been financed through European Union programmes, notably the Infrastructure and Environment Programme (2014–2020). Between 2004 and 2020, the total value of health projects co-financed by EU and national sources reached approximately PLN 33.2 billion, of which PLN 19.7 billion was allocated to hospital infrastructure—including facility modernisation, ward expansion, and the acquisition of modern medical equipment [38]. While these investments have had a tangible impact, the pace of healthcare workforce development and infrastructure expansion in Lubuskie remains insufficient to enhance the region’s relative specialisation in the healthcare sector.

5.1.3. Green Economy

Within the Green Economy domain, moderate changes in specialisation were observed across sectors related to water management, waste management, and energy production. Although the data do not indicate major structural shifts, some trends suggest a growing relevance of selected environmental sectors in the region.

In water management (E36), despite a marginal LQ increase from 1.65 to 1.68 (ΔLQ = +0.03), the 2021 data confirm a well-developed water and sewage infrastructure in the Lubuskie Voivodeship. According to Płuciennik-Koropczuk and Myszograj [39], 94.8% of the population was connected to the water supply network, which extended over 7100 km—with access reaching 90.1% in rural areas. This high level of accessibility reflects the impact of EU co-financed infrastructure investments, supported by national modernisation programmes, and suggests that Lubuskie’s specialisation in E36 is grounded in tangible improvements in environmental infrastructure.

The paper and paper products sector (C17) showed a clear increase in specialisation, with the LQ rising from 2.11 to 2.29 (ΔLQ = +0.18), confirming its growing economic significance. As this industry is closely linked to circular economy principles—such as recycling, secondary raw materials, and eco-friendly packaging—it aligns strongly with the Green Economy RIS3 domain. The observed growth may reflect rising demand for sustainable packaging and low-impact production processes.

In waste management (E38), a slight increase in LQ was recorded (from 0.87 to 0.89; ΔLQ = +0.02). While modest, this may signal the initial effects of circular economy implementation. According to Dziekański et al. [40], Lubuskie reported one of the lowest investment levels in waste management, including limited expenditure on fixed assets for recycling—hindering the development of advanced recovery infrastructure. However, Vambol et al. [41] documented a national upward trend in municipal investments, including the construction of mechanical–biological treatment plants and composting facilities. Some of these projects likely reached Lubuskie, albeit on a limited scale. As such, the growth observed in E38 likely reflects early steps toward circular transition, constrained by underinvestment and slow implementation at the regional level.

Conversely, the electricity, gas, and steam supply sector (D35) experienced a decline in specialisation, with the LQ decreasing from 0.42 to 0.16 (ΔLQ = −0.27). This trend may reflect the limited presence of large-scale energy producers in Lubuskie and its marginal role in national conventional energy production. Despite the region’s high potential in renewable energy—particularly solar and wind—this has not yet translated into significant employment growth. One contributing factor may be the decentralised nature of such investments, often undertaken by individual prosumers who are not included in official employment statistics.

Although the Green Economy is formally designated as one of Lubuskie’s smart specialisations, data from the analysed period do not show a clear reflection of this priority in the region’s employment structure. This may result from the nature of green transition processes, which do not always generate direct employment gains, especially within the SME sector. Simultaneously, the gap between investment momentum and job creation may highlight the need for better alignment between regional development policies and labour market dynamics.

6. Discussion and Implications for RIS3 Design and Implementation

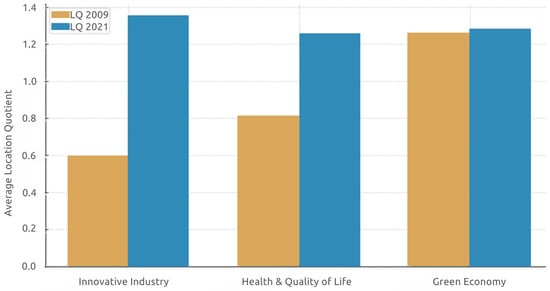

The full complexity of Lubuskie’s evolving economic structure was assessed through Location Quotient (LQ) calculations for each two-digit PKD sector (Table 1), enabling the identification of both established and transitional industrial niches. For analytical clarity, the relevant sectors were subsequently grouped into three smart specialisation domains, as defined in Annex 2 of the RIS3 Lubuskie strategy (2019) [14] (based on initial selections from the 2015 smart specialisation report [42]): Innovative Industry (C25, C28), Health and Quality of Life (Q86–Q88), and Green Economy (E36, E38). Figure 1 presents the average LQ values for each domain in 2009 and 2021, revealing strong increases in Innovative Industry and Health and Quality of Life, alongside only modest gains in the Green Economy.

Figure 1.

Average Location Quotient (LQ) by smart specialisation domain in Lubuskie, 2009 and 2021. Source: Author’s own elaboration based on GUS Z-06 data.

This visual summary not only confirms the alignment between emerging regional strengths and strategic RIS3 priorities, it also highlights areas where additional policy support—such as targeted instruments for green innovation—may be needed.

6.1. Adequacy of RIS3 Priorities Relative to the Region’s Structure

The LQ analysis demonstrates that the priorities defined in the Lubuskie RIS3 strategy generally align with the region’s economic structure and potential. The Innovative Industry domain—represented, for example, by sectors C25 and C28—increased in relative importance between 2009 and 2021, confirming the relevance of this specialisation area. At the same time, the continued high concentration in sectors C15, C17, and C29 suggests that traditional manufacturing remains a core component of the regional economy.

The Health and Quality of Life domain has been primarily strengthened by social work services (Q88), which—although not recognised as a specialisation in 2009—have since emerged as one of the fastest-growing sectors. In contrast, the Green Economy domain (E36, E38) showed only modest gains, indicating a need to strengthen instruments that support green innovation and ecological transformation.

6.2. Mechanisms Strengthening New and Traditional Specialisations

The transformation observed in the metal fabrication sector (C25) can be attributed primarily to targeted SME support under the Lubuskie Regional Operational Programme, which enabled investments in precision metalworking technologies. Rising demand for industrial components further strengthened the sector’s market position, resulting in a significant LQ increase—from 0.14 in 2009 to 1.52 in 2021.

However, the most dramatic growth occurred in social work activities without accommodation (Q88), where LQ rose from 0.13 to 1.41. In addition to the expansion of NGO networks and municipal support programmes for socially excluded groups, a key driver was the explicit inclusion of this field in both the Lubuskie 2030 Development Strategy and the ex ante evaluation of the RPO WL 2021–2027. By prioritising social inclusion, the region launched dedicated grant schemes and simplified access to funding for day-service centres, counselling, and reintegration programmes, greatly accelerating development in this sector.

At the same time, a decline was observed in traditional industries, notably wood products (C16) and motor vehicles (C29), which lost 0.22 and 0.85 LQ points, respectively. These reductions reflect barriers to modernising machinery, limited access to advanced technologies, and intensified global competition. A misalignment between support instruments and the specific needs of these sectors has hindered their ability to maintain previously strong regional concentrations.

Taken together—the successes of C25 and Q88, alongside the challenges faced by C16 and C29—these trends provide insight into the mechanisms that are reinforcing emerging specialisations while constraining legacy sectors.

6.3. Implementation Barriers and Policy Gaps

While regional structures such as the Western Poland Horizon Europe Contact Point and individual grant schemes suggest some level of coordination, no systematic evaluation has been conducted in Lubuskie on the effectiveness of cooperation among RPO managing bodies, Horizon Europe actors, and national innovation programmes. A 2025 study by the European Parliament highlights that, despite formal procedures for combining ROP and Horizon funds, inter-institutional coordination often remains weak. Similarly, the European Commission’s 2022 guidance on synergies between Horizon Europe and ERDF programmes warns that, without close cooperation between cohesion fund managers and research programme bodies, priorities may become misaligned and activities duplicated.

Assuming that these broader findings also apply to Lubuskie, it would be prudent to strengthen coordination mechanisms—for example, by establishing joint planning platforms between Marshal’s Office departments and regional research institutions, or by introducing enhanced tools for monitoring project synergies. Such measures could reduce fragmentation in support provision and improve the effectiveness of fund allocation for targeted smart specialisations.

At the same time, the ex ante evaluation of Lubuskie’s RPO 2021–2027 notes that only a small share of ERDF-funded projects involve substantial R&D in the Green Economy, with most support directed toward technical assistance (e.g., energy audits, project documentation) (RPO WL Ex Ante Evaluation 2021–2027). This suggests that local universities and research centres are not sufficiently engaged in green innovation efforts, limiting the region’s capacity to generate breakthrough ecological solutions. Their involvement could be strengthened through dedicated calls for green R&D projects and formalised partnerships, accelerating progress in renewable energy, water management, and circular economy technologies.

6.4. Recommendations for Structurally Weak but Non-Peripheral Regions

The challenges identified in the Lubuskie region reflect a broader pattern observed across structurally weak but non-peripheral regions in the European Union. These territories often combine low innovation capacity with limited institutional coherence, despite their geographic proximity to major growth centres. The comparative literature supports the view that these conditions hinder the effective implementation of Smart Specialisation Strategies.

Barzotto et al. [5] demonstrated that while extra-regional collaboration can improve innovation outcomes in lagging regions, its effectiveness depends on the presence of shared technological trajectories and coordinated strategic planning. Similarly, Wibisono [43], in a systematic review of RIS3’s implementation in less-developed EU regions, identified three major obstacles: limited RIS capacity, fragmented governance, and weak local and extra-regional cooperation. These systemic barriers are likely relevant to the Lubuskie case as well—especially given its dual-institutional structure and limited evidence of inter-regional collaboration. However, further research is needed to better understand the scope and mechanisms of these constraints.

Comparable institutional and structural obstacles have been documented in other structurally weak but non-peripheral regions—such as Sachsen-Anhalt (Germany), Friuli Venezia Giulia (Italy), and Lorraine (France)—where RIS3 strategies have faced limited absorption capacity, coordination failures, and a lack of clear sectoral anchors [5]. These cases reinforce the need for place-sensitive policy design tailored to the hybrid characteristics of such territories.

Insights from the Lubuskie case suggest several policy recommendations. First, targeted support for metal fabrication (C25) through SME development grants at the national and regional levels may have contributed to the sector’s rising specialisation, indicating that aligning RIS3 with existing instruments can enhance its impact. Second, the growing importance of social services (Q87) appears to be driven by demographic trends and EU-funded investments in care infrastructure, highlighting the need for better integration of such services into regional innovation ecosystems. Third, the Green Economy, although declared a priority, lacks concrete operationalisation through investment incentives, incubators, or cluster initiatives, pointing to a gap between the RIS3 goals and actual spending priorities.

Based on these findings, it is advisable to introduce regular RIS3 priority reviews every three to four years, allowing for more flexible responses to emerging high-potential sectors such as social services [44]. Additionally, expanding support for the Green Economy—through dedicated clusters, targeted grants, and incubator programmes in areas such as renewable energy, water management, and the bioeconomy—is essential [45]. Finally, strengthening public–private partnerships and deepening cooperation among regional authorities, industry, and academia can facilitate more effective knowledge and technology transfer, consistent with the central role of clusters in building innovative ecosystems [46].

6.5. Research Limitations and Further Development Directions

The cross-sectional analysis of LQ changes presented in this study is based on only two reference years and data aggregated at the 2-digit PKD level, which may obscure short-term fluctuations and the characteristics of highly specialised niches. While additional time points could theoretically be included, the Location Quotient is a structural indicator that captures relative positioning rather than dynamic evolution. Therefore, the decision to limit the analysis to 2009 and 2021 was made to ensure interpretive clarity and avoid misleading assumptions about temporal trends.

Future research would benefit from expanding the analysis to include firm-level microdata, value-added indicators, and additional years, in order to provide a more nuanced view of specialisation trajectories. In addition, case studies of key industrial and service clusters could offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of regional growth and the barriers to effective RIS3 implementation.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Research Findings

This study has demonstrated that the RIS3 priorities adopted in Lubuskie broadly align with the region’s underlying economic structure, while also revealing notable mismatches. The Location Quotient (LQ) analysis shows that two of the three selected domains—Innovative Industry, and Health and Quality of Life—strengthened their relative positions between 2009 and 2021.

Based on the empirical results, this study’s main hypotheses can be assessed as follows:

H1.

(Partial overlap between RIS3 priorities and actual specialisations): Confirmed. While some RIS3 domains align well with regional employment structures, others—particularly the Green Economy—remain weakly embedded in the local economy.

H1a.

(At least one RIS3 sector shows a stagnant or declining LQ): Confirmed. The healthcare sector (Q86) recorded a decline in LQ from 0.93 to 0.83, and the electricity and gas sector (D35) fell sharply from 0.42 to 0.16.

H1b.

(At least one non-RIS3 sector shows significant LQ growth): Not applicable. All sectors analysed fall within Lubuskie’s RIS3 domains. Future research could extend the scope to include non-prioritised sectors.

H1c.

(Green Economy domain shows the weakest alignment): Confirmed. Only marginal LQ increases were observed in sectors such as E36 (ΔLQ = +0.03) and E38 (ΔLQ = +0.02), while D35 experienced a significant decline, underscoring the weak institutional and economic base for green specialisation.

Overall, the number of strong specialisations (LQ ≥ 1.25) remained relatively constant between 2009 and 2021, but their composition shifted. Traditional manufacturing sectors (e.g., leather, paper, motor vehicles) continue to play a central role, while new specialisations—particularly metal fabrication (C25) and social care services (Q88)—have emerged, supported by structural demand and targeted policy instruments.

7.2. Limitations and Further Research Needs

Several methodological and data constraints limit the generalisability of this study’s conclusions. First, the analysis relies on employment data from only two points in time and is aggregated at the 2-digit PKD level, which may obscure short-term fluctuations, intra-sectoral dynamics, and the performance of narrowly defined niches.

Second, employment shares alone do not fully capture regional innovation capacity. Complementary indicators—such as R&D intensity, patent activity, or value added per worker—could offer deeper insights into structural specialisation and innovation potential.

Third, this study did not directly assess the entrepreneurial discovery process or stakeholder engagement mechanisms, which are essential to RIS3’s implementation. These dimensions could be better explored through qualitative methods, including case studies and interviews.

Future research should therefore extend the time frame (e.g., include 2025–2030 data), integrate firm-level microdata and innovation metrics, and undertake in-depth analyses of regional clusters or policy processes. Such approaches would help unpack the drivers of successful specialisation and identify persistent implementation barriers in structurally weak but non-peripheral regions.

7.3. Recommendations for Regional Policy and RIS3 in “In-Between” Regions

For regions that are centrally located yet structurally constrained, our findings suggest three key policy adjustments to enhance the effectiveness of RIS3’s implementation:

- Dynamic Priority Reviews: Introduce formal RIS3 update cycles every three to four years to incorporate emerging high-potential domains—such as social services—and to retire or recalibrate underperforming sectors. These reviews should go beyond quantitative indicators such as LQ values and include structured entrepreneurial discovery processes (EDPs) and participatory foresight exercises. In structurally weak but non-peripheral regions, where institutional fragmentation and data scarcity pose challenges, such hybrid approaches could strengthen both the empirical foundations and the stakeholder legitimacy of RIS3 revisions.

- Strengthened Green Innovation Instruments: Scale up dedicated support for the Green Economy through thematic clusters, R&D co-funding schemes, and incubator programmes targeting renewable energy, water management, and circular economy ventures. This should be complemented by calls that explicitly require academic–industry partnerships to activate local research capacities.

- Enhanced Multi-Level Coordination and Capacity-Building: Establish joint planning platforms linking RPO managing authorities, Horizon Europe intermediaries, and national innovation agencies. In parallel, invest in intermediary organisations (e.g., technology transfer offices, cluster managers) to facilitate knowledge exchange. Tailored capacity-building for SMEs and public institutions—covering grant writing, project management, and networking—will help “in-between” regions overcome institutional fragmentation and better access cohesion and innovation funds.

By adopting these measures, structurally weak but non-peripheral regions like Lubuskie can more effectively leverage their latent assets and transition toward sustainable, innovation-driven growth—bridging the gap between geographic centrality and economic dynamism.

This study offers an original contribution by applying Location Quotient (LQ) analysis to a structurally weak but non-peripheral region—an “in-between” territorial type often overlooked in smart specialisation research. Building on the methodology developed by Kudełko, Żmija, and Żmija [1], this article enhances their approach by integrating regional typologies (ESPON, OECD) and institutional dimensions into the assessment of RIS3 alignment.

The findings reveal both emerging endogenous strengths (e.g., metal fabrication, social care) and a significant misalignment between Green Economy priorities and the region’s structural conditions. This framework supports a more place-sensitive and context-aware adaptation of innovation strategies in fragmented territorial settings.

Funding

This research did not receive external research funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was covered by the University of Zielona Góra.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The employment data used in this study were obtained from the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS), based on the Z-06 report. Processed data and LQ calculations are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Location Quotients (LQs) by PKD sector in Lubusz Voivodeship: 2009 vs. 2021.

Table A1.

Location Quotients (LQs) by PKD sector in Lubusz Voivodeship: 2009 vs. 2021.

| PKD (2-Digit) | Sector Description | LQ 2009 | LQ 2021 | ΔLQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (05–09) | Mining and quarrying | 0.1958 | 0.0962 | −0.0996 |

| C13 | Textile manufacturing | 1.7776 | 1.6551 | −0.1226 |

| C15 | Leather and related products | 3.225 | 3.3417 | 0.1167 |

| C16 | Wood products | 3.1484 | 2.931 | −0.2174 |

| C17 | Paper and paper products | 2.1103 | 2.2888 | 0.1785 |

| C23 | Manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products | 1.7328 | 1.4931 | −0.2396 |

| C25 | Fabricated metal products (excl. machinery and equipment) | 0.1366 | 1.5203 | 1.3837 |

| C26 | Computer, Electronic, and optical products | 2.5692 | 2.2328 | −0.3364 |

| C28 | Machinery and equipment n.e.c. | 1.0418 | 1.1805 | 0.1387 |

| C29 | Motor vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers | 3.1582 | 2.3045 | −0.8537 |

| C30 | Other transport equipment | 0.2781 | 0 | −0.2781 |

| C31 | Furniture | 1.6319 | 1.9108 | 0.2789 |

| C32 | Other manufacturing | 0.6951 | 0.9172 | 0.2222 |

| C33 | Repair and installation of machinery and equipment | 0.6446 | 0.4607 | −0.1839 |

| D35 | Electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply | 0.4207 | 0.1552 | −0.2654 |

| E36 | Water collection, treatment, and supply | 1.6458 | 1.6768 | 0.0311 |

| E37 | Sewerage; waste treatment and disposal | 1.5379 | 0 | −1.5379 |

| E38 | Waste collection, treatment, and disposal; materials recovery | 0.8719 | 0.8922 | 0.0203 |

| E39 | Remediation and other waste management services | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| J62 | Computer programming, consultancy, and related activities | 0.4603 | 0.2628 | −0.1975 |

| Q86 | Human health activities | 0.931 | 0.8346 | −0.0964 |

| Q87 | Residential care activities | 1.3714 | 1.5156 | 0.1442 |

| Q88 | Social work activities without accommodation | 0.1309 | 1.4127 | 1.2818 |

References

- Kudełko, J.; Żmija, K.; Żmija, D. Regional smart specialisations in the light of dynamic changes in the employment structure: The case of a region in Poland. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2022, 17, 133–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D.; David, P.A.; Hall, B.H. Smart Specialisation: From Academic Idea to Political Instrument, the Surprising Career of a Concept and the Difficulties Involved in its Implementation. MTEI Working Paper, EPFL Lausanne 2011. Available online: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/170252 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations. European Commission 2009. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/regi/dv/barca_report_/barca_report_en.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialisation, Regional Growth and Applications to EU Cohesion Policy. IEB Working Paper 2011, 2011/14. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ieb/wpaper/doc2011-14.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Barzotto, M.; Corradini, C.; Fai, F.M.; Labory, S.; Tomlinson, P.R. Enhancing Innovative Capabilities in Lagging Regions: An Extra-Regional Collaboration Approach to Smart Specialisation. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2019, 12, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. Shrinking Rural Regions in Europe—Towards Smart and Innovative Approaches to Regional Development Challenges in Depopulating Rural Regions; ESPON Policy Brief; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Territorial Evidence and Policy Advice for Regions with Geographical Specificities; Final Report; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://archive.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20Policy%20paper%2C%20Rural%20areas_long%20version.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- OECD. A New Rural Development Paradigm for the 21st Century: A Toolkit for Developing Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F.; Trippl, M. One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Asheim, B.T. Place-based innovation policy for industrial diversification in regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1638–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. The early experience of smart specialisation implementation in EU cohesion policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1407–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialisation, Entrepreneurship and SMEs: Issues and Challenges for a Results-Oriented EU Regional Policy. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Lubuskiego 2030; Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2019; Available online: https://bip.lubuskie.pl/strategia_rozwoju_wojewodztwa_lubuskiego_2030/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Commission. Annex to the Proposal for a Council Recommendation on the 2023 National Reform Programme of Poland and Delivering a Council Opinion on the 2023 Convergence Programme of Poland—Country Report Poland 2023; SWD(2023) 621 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-05/PL_SWD_2023_621_1_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- OECD. Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Poland; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuratowicz, A. Growing Wage Inequalities in Poland: Could Foreign Investment Be Part of the Explanation? ECFIN Ctry. Focus 2005, 2, 1–5. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication1461_en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- ESPON. Regional Innovation Readiness: Typologies and Policy Implications; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Territorial Patterns and Relations in Poland; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Territorial Evidence and Policy Advice: ESPON 2020 Programme Overview; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Country Report: Poland—Economy and Finance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/ip245_en.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Kapela, M. Poland in International Supply Chains in 1995–2020: Global Value Chains and Shift-Share Analysis. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, XXVII, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niziałek, I. The Importance of Furniture Clusters in Poland. Ann. WULS–SGGW For. Wood Technol. 2013, 83, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, B.; Guzik, R.; Gwosdz, K.; Dej, M. The crisis and beyond: The dynamics and restructuring of automotive industry in Poland. Int. J. Automot. Technol. Manag. 2013, 13, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Give Consulting. Relocation of Production by Suppliers to the Automotive Industry: Focus on Central and Eastern Europe (CEE); Give Consulting Blog; Give Consulting: Munich, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.give-consulting.com/index.php/en/referenzen/give-blog/relocation-of-production-by-suppliers-to-the-automotive-industry-focus-on-central-and-eastern-europe-cee (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- PAIH. The Professional Electronics Sector, 2023; Poland Investment and Trade Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gliń, W.; Stasiak-Betlejewska, R. Analysis of the Production Processes Automation Level in Poland. Qual. Prod. Improv. 2017, 1, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerging-Europe. Mind the Automation Gap: R&D in Central and Eastern Europe. 2024. Available online: https://emerging-europe.com/analysis/mind-the-automation-gap-rd-in-central-and-eastern-europe (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Institute for Public Affairs Research (IPC). Diagnosis of the State and Development Directions of Social Services in the Lubuskie Voivodeship; Marshal’s Office of the Lubuskie Voivodeship: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lubuskie Rural Network (KSOW). Analysis of Development Needs of Municipalities in the Lubuskie Voivodeship; Lubuskie KSOW: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Long-Term Care in Ageing Poland; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/381071468189835102/long-term-care-in-ageing-poland (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Social Assistance and Care for Children and Families in 2021; Statistics Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny): Warsaw, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5487/10/13/1/pomoc_spoleczna_i_opieka_nad_dzieckiem_i_rodzina_w_2021.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2025; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Council of Lubuskie Voivodeship. Report on the Implementation of Lubuskie Health Strategy 2020–2021; Sejmik Województwa Lubuskiego: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (Poland). Summary of the Health Needs Map—2022 Status; Ministry of Health: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/mapa-potrzeb-zdrowotnych (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Toczek, M. Lubuskie Hospitals Among the Best in the World. Lubuskie.pl. 5 March 2021. Available online: https://lubuskie.pl/wiadomosci/16293 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K.; Kozieł, A. European Union Structural Funds as the Source of Financing Health Care Infrastructure Investments in Poland—A Longitudinal Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płuciennik-Koropczuk, E.; Myszograj, S. Water and Sewage Management in the Districts of Lubuskie Voivodeship, Poland. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2022, 32, 345–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziekański, P.; Dziekańska, J.; Kiełbasa, A. Still Trade-Off or Already Synergy between Waste Management and the Environment? In the Light of Experience at the Level of the Voivodeship in Poland. Kwart. Organ. Zarządzanie 2023, 4, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Vambol, V.; Kowalczyk-Juśko, A.; Vambol, S.; Mazur, A.; Goroneskul, M.; Khan, N.A. Multi-criteria Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste Management and Resource Recovery in Poland Compared to Other EU Countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship. Smart Specialisations of the Lubusz Region [Inteligentne Specjalizacje Województwa Lubuskiego]; Marshal Office of the Lubusz Voivodeship: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wibisono, E. Smart Specialisation in Less-Developed Regions of the European Union: A Systematic Literature Review. Region 2022, 9, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3); Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Policies to Support Green Entrepreneurship; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Clusters, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).