Abstract

In almost all institutional discourses about universities, students are mentioned. Universities are defined as dynamic areas that pave the way for students to acquire and develop scientifically based professional skills. Students are also given importance in explanations about creating a sustainable university. However, their contributions have been neglected in the development of this idea. Based on this inspiration, this study aims to examine the kind of expansions the university reality constructed by university students with their cognitive patterns can provide to the idea of creating a sustainable university. To achieve this aim, firstly, the university reality constructed by students enrolled in an associate degree program at a university, with their cognitive patterns, is explained through metaphors. Accordingly, open-ended questions were asked to 200 university students who were in the process of experiencing university life and volunteered to participate in the study. The answers received were evaluated through descriptive analysis and content analysis. As a result of the research, it was seen that 119 metaphors were produced, and these metaphors could be divided into seven categories with the titles of university as a structure that expresses, develops, and enlightens university reality; university as a structure that reaches goals; university as a social life area that accommodates differences and offers diversity; university as a structure that limits; university as a structure that challenges; university as a structure that liberates; and university as a structure that provides security and peace. Then, it was discussed how university students’ explanations about university reality would benefit the establishment of a sustainable university. While this study provides insights into university students’ perspectives on the university, it also contributes to strengthening and expanding the existing idea of a sustainable university.

1. Introduction

In today’s world, sustainable development goals have become one of the leading issues that concern all countries globally. Sustainable development aims to ensure that existing human communities meet their own needs by considering the resource needs of future generations [1]. Sustainability, closely tied to culture, refers to the interplay between social systems and the biophysical, economic, and political worlds and how they influence and are influenced by each other [2]. Therefore, sustainability encompasses a broad range of content that extends far beyond environmental issues, encompassing economic and social conditions [1]. In terms of achieving sustainable development goals, higher education institutions are of critical importance and play a crucial role in guiding society towards sustainability [2,3,4]. To build a sustainable future in all areas, such as the environment, economy, politics, and technology, awareness must be created in the social sphere [5] Accordingly, universities are regarded as institutions equipped with the structural and intellectual resources needed to support such transformation. They serve as dynamic environments that contribute to the scientific, technological, economic, social, and cultural development of society, and help students acquire and refine scientifically grounded professional skills essential for advancement in these areas [6,7,8].

A sustainable university is defined as an institution that strives to minimize the economic, environmental, social, and health impacts resulting from resource use while conducting research, education, and training activities and to create social awareness about a sustainable lifestyle [9].

Although Transformative Learning Theory [10] is a powerful framework for understanding personal change in adult education, the present study does not aim to analyze individual transformation processes. Instead, it investigates how students cognitively construct the university through metaphors and how these constructions might contribute to the discourse of sustainable universities.

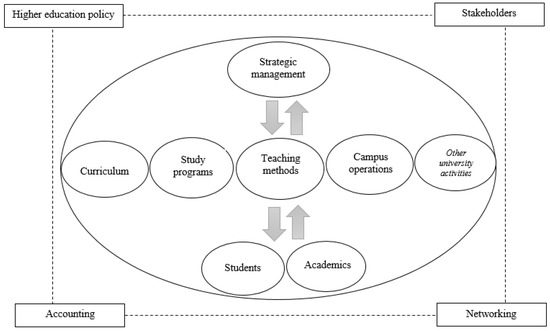

Upon examining the relevant literature, numerous studies on sustainable universities are encountered. For example, [3] stated in their study based on the Deming Cycle that sustainable universities have four basic components: policy (mission, vision, strategic goals), operations (sustainability of education, research, and practices), evaluation (measurement of sustainability practices), and optimization (improvements in problem areas). In their study, [11] identified 10 factors that enable sustainability in universities. These include sustainability curriculum, research and innovation, collaboration, media, pedagogy, sustainability leadership, instructor qualifications, government policies, sustainability auditing, and organizational commitment [12] investigated the place and importance of sustainability in the curricula of universities providing education and training in the field of hotel management. [13] examined the campus operational practices implemented worldwide for sustainability. [14] conducted a systematic review of sustainable universities based on the findings of 66 articles and obtained striking results regarding the characteristics and activities of sustainable universities. The researcher emphasized that the concept of sustainable universities should encompass all dimensions of sustainable development, requiring universities to go beyond preventing resource waste and developing their relational networks. This involves addressing all issues related to society and stakeholders, providing guidance, and implementing these strategies at a strategic level. As seen in Figure 1, the researcher noted that universities should adopt a two-way management approach, combining top-down and bottom-up approaches, and involve the student group in their practices.

Figure 1.

Key features of the sustainable university. Source: [14].

Universities do not have a monolithic texture, as they produce a living space woven with their understanding and values [15,16] They consist of actors and actor groups that have the potential to produce different meaning patterns within their organizational structure and are in a spiral of interactions and relationships. Unlike other institutions, universities have stakeholders rather than shareholders [17]. University students constitute an important group within these groups that are more passive than other groups [15]. When defining their reasons for existence, universities adopt an institutional discourse that prioritizes this group. Within this discourse, universities emphasize that they provide students with the skills of problem-solving, a critical approach to facts, and the ability to interpret, process, and apply acquired knowledge to new situations, thereby developing intellectual competencies [18]. Even at the center of the unique characteristics of university education, where learner characteristics and individual preferences such as undertaking research and learning on their own and making this process sustainable are dominant, there is a student group with a heterogeneous and dynamic structure [18,19]. In today’s world, many universities have demonstrated their support for the concept of a sustainable university through sustainability leadership [20]. They have transformed towards student-centered learning, which can challenge traditional mindsets and encourage creativity [21,22,23].

On the other hand, the teaching style has evolved from a traditional teacher-to-student approach to a student-to-student learning style [24]. This requires having the capacity to create sustainability competence, including students [25,26]. At this point, the following questions arise: What is the university reality that the student group, which is given importance within the sustainable university reality, has constructed through their cognitive patterns? Does the university reality from the students’ perspective contribute to the idea of building a sustainable university? If so, in what ways do these contributions expand and/or develop the idea of a sustainable university?

When the literature on sustainable universities is examined, no study has been found that evaluates universities through the lens of their students. Inspired by the gap mentioned and the information provided above, it is claimed that addressing the university through the perspectives of university students will provide strong openings for both academics and practitioners interested in building a sustainable university. Therefore, this study aims to examine the kind of openings that the university reality, constructed by university students through their cognitive patterns, can provide to the idea of building a sustainable university. In this context, the research question of the study is expressed as follows: What kind of expansions does the university reality constructed by university students with their own cognitive patterns provide to the idea of creating a sustainable university? Qualitative research methods and the power of metaphors are used to answer the research question.

The power of metaphors is frequently employed in interpretive analyses of organizations (for example [27,28,29,30,31,32]). Because metaphors can map how individuals transform organizational life into a subjective reality by passing it through the processes of perception, interpretation, and evaluation, the use of metaphors in interpretive and symbolic analyses of organizations is privileged compared to other symbols [15,27]. With the help of metaphors, abstract concepts can be restructured into more concrete concepts that are easier to understand and define [33,34]. Thus, abstract concepts that have an unknown feature can be given more known and definable features. Metaphors enable us to make meaning transfers by likening concepts that we have difficulty understanding to concepts that we understand better at the cognitive level [35]. By acting as evocative metaphors that condense and facilitate our understanding of the concept or phenomenon being explored, it is transformed into a cognitive image and defined, becoming a powerful communication tool [32]. In this way, it will be possible to go into the depths of a multi-layered phenomenon regarding how university students approach the university. The information obtained at that depth will inspire us to build sustainable universities.

2. Method

The problems sought to be addressed within the scope of the study are those that can be answered by illuminating the data obtained from the lived world. Efforts in this direction require that the research in question be grounded in an empirical discussion and that a realistic and descriptive picture be presented regarding the subject [27]. This requirement prompts the researcher to adopt a descriptive methodology (idiographic methodology) and qualitative research methods that aim to understand how actors make sense of situations [36,37]. Descriptive methodology (also known as idiographic methodology) argues that discovering and understanding the social world can be achieved through subjective experiences and that actors actively participate in the process of constructing meanings [36,38]. It is interested in discovering subjective situations that happen inside rather than an external objective reality. Qualitative research, a subjective research method, offers a more in-depth opportunity to explore all dimensions of the identified problems and provides strong clues for understanding why and how social events and phenomena are experienced [27,37,39]. Therefore, the qualitative research method was adopted in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

A general overview of the research method.

In this study, it is deemed appropriate to employ a discourse analysis design as the research approach. In this study, a query is conducted through metaphors [33] that concretize abstract concepts, making them more familiar and allowing us to define the concept in question more easily.

The universe of the study was selected by considering the principles of feasibility, suitability, accessibility, and voluntariness [40]. It was preferred to conduct interviews with active students enrolled in the first and second years of an associate degree program of a higher education institution. Therefore, students studying within this higher education structure constituted the data sources of the study. The study universe consists of a total of 278 students. A total of 78 students were excluded from the scope because 6 students out of the 278 students who comprised the universe refused to participate in the study, 25 students were determined to have withdrawn their registration, and 47 students could not be reached. The remaining 200 students constituted the sample of the study. The 200 participants who were interviewed within the scope of the research constitute 71.94% of the universe. The achieved representativeness rate shows that the data obtained within the scope of the study have the power to describe the current situation. In this study, criterion sampling was employed, where the main criterion was being an active first- or second-year student in an associate degree program. The unit of analysis was not the participants themselves, but rather the metaphorical expressions they produced to conceptualize their university experience. The role of the researcher is of great importance in metaphor analysis [27,41]. The researcher can either pre-determine the metaphors and present them to the participant as options or leave the task of determining the metaphors to the participant and act in a way that detects, evaluates, and interprets the images. In both ways, the role that the researcher assigns to himself during the data collection process directly affects the data acquisition method. In this study, the researchers embarked on a metaphor hunt, adopting an identity that enabled them to detect and evaluate the images and subsequently allowed the participants to produce the metaphors. Since the metaphors in the study were requested to be produced by the participants, interviews were conducted through a semi-structured interview form.

Before planning the study, the top management team of the relevant university was informed about the study’s content and course, and the necessary permissions were obtained. After the universe of the study was determined, lists were prepared for each researcher to interview. Participants on the lists were called one by one and informed about the study. It was explained that their participation would be voluntary. It was clearly stated that their names would not be used in the study under any circumstances and that they would be assigned a pseudonym during the analysis process. Participants were reassured about the security and confidentiality of the study, and an appointment was requested.

In this study, the interviews were conducted via a webinar (online) platform that allows face-to-face interaction via the internet. Thus, the features of the internet, such as eliminating geographical boundaries, providing researchers with flexibility in terms of time and space, expanding the research area, facilitating continuous communication, and reducing data loss, were utilized [27,42]. In addition, the necessary sensitivity was demonstrated to establish trust between the researcher and the participant before each interview. The interview began with a chat-style, unstructured conversation to eliminate social barriers between the researcher and the participant [43]. During the data collection process, qualitative research ethics were adhered to, and the ethical contingency stance, defined as minimizing the threat of personalization arising from the researchers’ experiences, was employed [44].

The interviews conducted during the data collection phase of the research lasted approximately 30 min. All interviews were recorded, along with detailed interview notes. The records obtained were analyzed and written in a manner that ensured textual integrity, thus creating a raw data text [40]. The interviews made it possible to obtain a rich qualitative data set. Based on the obtained data set, firstly, the responses of the participants constituting the sample to the question, “If I asked you to compare the university to an object, a plant, an animal, a living being, a shape, a historical figure or a fairy tale hero, what would you compare it to?” were evaluated. The metaphors used by the participants were determined. After identifying the metaphors, the following question arose: What do the participants mean by the metaphors they use when describing the university? As a result of the stated curiosity, the participants were asked whether they had a reason or not. Moreover, by evaluating the responses received, a descriptive text table was created by remaining faithful to the participants’ expressions. Then, metaphors with the same meaning were grouped based on the descriptive expressions. Thus, a table of categories and metaphors regarding university students’ cognition towards the university was created (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories and metaphors regarding university students’ cognitions about university.

The coding process followed the steps of identifying recurring metaphorical expressions, grouping them under semantically similar categories, and validating these categories through expert review. Each metaphor used by the participants was first documented in raw form, then interpreted contextually based on the participants’ own explanations. These steps formed the basis of the analytical framework presented in Table 2.

To ensure the appropriateness of the research, the criteria of credibility (internal validity), consistency (internal reliability), transferability (external validity), and confirmability (external reliability) were employed [34]. In this context, the entire research process was explained in detail, and the obtained data were grouped by consulting expert opinion. Finally, a table was prepared that included all metaphors and descriptive expressions (Table 2). Content analysis and descriptive analysis were conducted at the data analysis point of the relevant study. The content analysis aimed to determine the relationships between the data and the concepts that would explain the data. The descriptive analysis aimed to reflect the opinions of the participants and to include their direct statements in this direction [34]. Thus, the data obtained within the framework of the categories that emerged from descriptive analysis and content analysis were classified, presented, and interpreted within the scope of the research purpose.

3. Findings

Within the scope of the research, it was determined that 200 participants who formed the research group produced a total of 119 metaphors. The 119 metaphors were grouped based on their meanings. Thus, seven categories were obtained, namely university as a developing and enlightening structure; university as a structure that achieves goals; university as a social living space that accommodates differences and offers diversity; university as a limiting structure; university as a challenging structure; university as a liberating structure; and university as a structure that provides security and peace (Table 2).

When Table 2 is examined, it is evident that most metaphors (51) are found in the university category, which is characterized as a developing and enlightening structure, and that this category has the highest number of participants (91 people). The dominant metaphor in this category is the book, which consists of metaphors such as a tree, a prompter, an owl, a rollercoaster, life, and a time capsule. Some descriptive expressions belonging to these metaphors are as follows:

… Pushing the boundaries of life gives you the chance to discover them and have new experiences. It also makes you feel free, but the adrenaline you experience in that freedom teaches you to stand on your own two feet, and it is similar to having anxiety about the future, that is, the anxiety of whether you will be able to reach a conclusion. The different speed of the ups and downs on the rollercoaster may be similar to the opportunities and different experiences that come before us at university. At the same time, it is quite similar in terms of the fast passage of time with the good and bad of university life. (P66)

… But university life is a more personal place. A place where you are more yourself. A place where you are responsible. … (P45)

… Actually, when we think about the time we started university, I assume that our character was not fully established and I really think that university contributed a lot to this. In other words, I believe that the further we are from university, the harder it will be to see our self in our development. In other words, the closer we are, the better we will know ourselves. (P17)

… We can develop ourselves and get rid of our fears. It is a place where we can have fun and be happy, and also face our fears. I am afraid of amusement parks, I am afraid of heights, I am afraid of speed. I also protect myself from exams, I am afraid when I do not attend classes, I am afraid of not being able to do it. I am afraid of amusement parks but I love them very much. University also scares me, but I loved it as I got into it. (P23)

… When I first started university, I was just like water, going on a determined path and in a flow where I did not know the outcome, but when I finished university, all my accumulations and the information I acquired produced a new me. Like water turning into energy in a power plant. University was what brought out the power that existed inside me. (P195)

… Because it allows us to see things we cannot see more easily. (P108)

… There are unlimited resources that I can access, including our teachers, they all help us, I can access any source or information I want from many places, including my teachers. (P133)

The category consisting of 17 metaphors, obtained from 29 participants, is the university category as a structure that achieves goals. It is observed that this category comprises metaphors such as compass, ladder, freedom, an ant, and money. Some descriptive expressions belonging to these metaphors are as follows:

… It guides us students like a compass to reach our goals in our careers. (P72)

… Because it takes us to our career goals faster. … university is a means of transportation for this. (P161)

… Because when we look at the current conditions of the country, they are hiring a high school graduate–not to judge–a cleaner. When you go to university, when you have a university diploma, your ranking increases a bit. (P41)

…University is like a way of salvation for me to be able to stand on my own in the future, to be able to hold on to a life on my own (P119)

… I need something like this to give direction to my future and I want to achieve good things for my future. …University is the future for me. I think I need to progress in this in order to establish a new life, to achieve something, to be able to move forward. (P155)

… Since I have to study because of my job… University is more of a tool for me to reach the profession I want rather than the goal. I am studying for the job I dream of. Since the most important reason for having a profession is to earn money. (P54)

… The standards of this country are certain. University is a mandatory place for me to attend for graduation. (P71)

… A situation that can give direction to my life may be useful for me in the future. I am currently doing business, I would have done without studying, but I am thinking of settling abroad, maybe it could be useful. (P139)

Another category created within the scope of the study is the university category, which serves as a social living space that incorporates differences and offers diversity. The 24 metaphors obtained from 41 participants in this category consist of terms such as ‘Unicorn,’ ‘Hogwarts Academy,’ ‘rainbow,’ and ‘chameleon.’ Some descriptive expressions related to these metaphors are as follows:

… Because it has the ability to bring people from every race, ethnicity, and geographical origin together in a single area, I think this is truly incredible. Contrary to the norms of society, I think it proves that you can get along with people you think you won’t get along with, and even become a family with them. … (P67)

… Because the people I have shared the same desks with throughout my life, some of whom are the sons of a CEO, some of whom come from a poor family, some from the far east, some from the west, some from different countries, we study together without discriminating based on religion, language, or race, and we have the opportunity to meet people. (P34)

… Everyone has different troubles, different life concerns, and different thoughts. It reminds me of heavy traffic. Some are extremely rich, some hitchhike to school. Everyone is extremely different from each other, but everyone is in the same place. It doesn’t matter whose child you are or the brand of the car. You will sit in those rows and take the same lesson. Just like you can move forward in a luxury car or a junk car in a traffic jam as much as the space in front of you. (P189)

… There are many blessings in it, there are fish, there are different species. It is exactly the same in university… there are many people, there are many people with completely different mindsets, and establishing relationships with those people with different mindsets will be a great advantage for us in the future because different mentalities, different perspectives, different interpretations, different thoughts, etc. All of these have an advantage. Frankly, I didn’t come to my department very willingly, but I came anyway based on this explanation I made so as not to waste time. (P162)

… University, like the sea, is an endless source of knowledge. Like different waves in the sea, university offers endless diversity between different disciplines and fields of knowledge. Each wave has its own power and knowledge. Likewise, each branch of knowledge offers a different perspective and depth. (P176)

… We encounter a lot of people here. We encounter and meet many people without looking at who they are, without knowing what they are for. Perhaps most of us come to hang out, make new friends, and have fun rather than study. That’s why I prefer to call it a social environment. (P165)

… I see university as a social activity area rather than education. The advantages of being a student are very good. All kinds of social activities at university are more suitable, more fun, and better. It is a place that allows you to experience all kinds of social activities and also provides education, and on top of that, it allows you to enjoy life. (P188)

As indicated by the 11 metaphors obtained from 11 participants, the metaphors grouped in the study with the university category as a limiting structure consist of metaphors such as prison, remote control, waste of time, trailer, and Changuu Island. Some descriptive expressions belonging to these metaphors are as follows:

… Because it is not a place I come to with great pleasure. I feel trapped when I am in it. I can’t say and speak what I want, where I want. It’s like I can’t get the information I want, in other words, it’s far behind my dreams. (P27)

… It’s a place you put up with for a diploma. It’s like you pay the fee and join a course. There are very few people who come to learn information. (P129)

… I describe it as loneliness because starting a university outside the city means spending time away from your family and friends. (P60)

… I compare universities to Changuu Island in today’s world, they raise slaves to continue the system we are in. I think universities have moved away from their main purpose of producing science, I think millions or even billions of people have been imprisoned within walls for years just to spend time, and I hope they return to their main purpose. (P197)

… Because except for some departments, it seems like a waste of time, but the biggest advantage is general culture for me, and I think there are so many unnecessary universities. I don’t think it’s right to have so many universities. Many people go to university because they have studied there, but I think they could learn better things in those four or two years or develop better if they find a job. (P33)

… Because there are many different unnecessary departments, you study while thinking they are unnecessary, but there are no job opportunities, you don’t know what the contribution to your life will be. I would like university to be a place where people who want more knowledge know that they can definitely have a profession after studying, now in my eyes it is a school where I only study for a diploma. (P185)

… Because after university education, you have a low chance of getting a job, you need to go to a good university department, otherwise it is a waste of time, money and years. You can have fun, that’s another thing, or you will start a business, that’s why you needed a diploma, it will be useful, otherwise it is a waste of a good department. (P81)

It is observed that eight participants produced eight metaphors, and the category university as a challenging structure’ consists of metaphors such as ‘Russian novel’, ‘business house’, ‘wall’, and ‘koala’. Some descriptive expressions related to these metaphors are as follows:

…Because you learn to stand on your own feet at university. Most of us come from different cities and usually rent a house as part of this plot. This is usually what happens. That’s why it seems to me as a school of difficulties. Again, most of us live happily ever after in the family home. But here, with the hassle of making our own meals, laundry and dishes, I see it as a place where we leave the home hearth and transition to real life. That’s why I see it as a school of difficulties. (P187)

…Student life is mostly coming from outside the city. It is difficult… Especially financially… University is something that impoverishes. Since Russian novels usually talk about poverty and destitution, students also face such difficulties. (P1)

…It is a bit difficult for me to get used to it, it is difficult to make friends and get used to our teachers. University is like moving to a new city, moving to a new house has such difficulties, I think, like making new neighbors, meeting new people, getting used to new places, learning new places. (P116)

…I love cars a lot. I can even say that I am a car enthusiast. I love university a lot, but they have a common problem with cars. They are both extremely expensive. Although it is nice to be in it, live in it, and continue your life with it, it also causes back pain due to its expenses. Since the books that the school wants, the dormitory or house to live in, life, shopping, socializing, etc. are all financial, as I said, I compare it to a car. The same goes for expenses, fuel, maintenance, etc. (P95)

It is observed that the category of university as a liberating structure comprises six metaphors generated by nine participants. Within the scope of the category in question, metaphors such as ’pigeon,’ ’freedom,’ ’road,’ and ’canvas’ were explored. Some descriptive expressions belonging to these metaphors are as follows:

… Young people live a slightly more restricted life in their own family homes, but when they go to university, they become a bit more comfortable. They become a bit more free in this regard. … pigeons immediately came to my mind, when freedom is restricted in prisons and so on, pigeons fly, etc. (P101)

… Because I can feel like myself at university. I can express my ideas as I wish. That’s why I feel free there. (P15)

… I used the university not to learn something on a subject, but as a tool to go somewhere else from the environment I was in, to be alone and to socialize from time to time. I left the place I was in thinking that the single and free life that the university provided me would make me free. … the university atmosphere taught me something about myself, and that is, university is a path to self-awareness and freedom for me. (P184)

… When we go to university, we can make our own decisions since we are far away from our environment. Also, due to our age, we can do many activities, programs, entertainment and similar things on our own without asking permission from someone else. … (P94)

… After we finish university, that is, after we finish, a bird flies and becomes free, just like people, they have a profession, become free, find a little more financial work opportunity, can direct their life, go wherever they want, achieve what they want by gaining financial freedom, like a bird, they can go wherever they want. (P112)

The last category, university as a structure that provides security and peace, consists of beach and house metaphors produced by 11 participants. Some descriptive expressions related to these metaphors are as follows:

…University is like my home. I spend all my time at school, do my homework, do my studies. (P9)

…Since we are away from our families here, we try to create a family environment for ourselves. The teachers are our parents, the others are our siblings. We carry out different responsibilities under the same roof. (P191)

…We learn to walk and talk at home and continue this when we reach school age. (P19)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Upon examining the relevant literature, it becomes apparent that various models have been developed regarding the concept of a sustainable university (e.g., [3,9,11,45,46]). When these models are examined holistically, it reveals how addressing the idea of a sustainable university only in specific dimensions, such as green campus and/or sustainable management, limits this idea. Therefore, these models indicate that the concept of a sustainable university encompasses all components related to the university, from campus life to campus infrastructure, from collaborations to sustainable leadership, from technology transfer to sustainability research, and that these components should be addressed holistically. In this context, how students, who are one of the most important stakeholders and the reason for the existence of universities, evaluate the university’s structure and how their perspectives will be reflected in the idea of a sustainable university is an important issue. The university period is a complex period in which young people leave childhood and move towards adulthood; their individual preferences are shaped, they become more active variable and sensitive, and their characteristics such as self-learning, research, and meeting their needs develop [19,47,48]. Therefore, it was not surprising to encounter expressions that described being faced with economic, socio-cultural, and emotional difficulties in the metaphors accessed.

On the other hand, students stated that despite these difficulties, university life offered them opportunities such as pushing the boundaries of their lives, revealing their potential, discovering themselves and the world, gaining new experiences, expanding their areas of interest, confronting their fears, acquiring knowledge, and achieving personal growth. Additionally, it is evident that university students, being a highly mobile group, significantly shape university life. The participants expressed their satisfaction with the fact that university life offers students with different thought structures, from different geographies and different social structures, an opportunity to meet, get to know, integrate, and socialize regardless of their religion, language, race, and ethnicity, and that it also provides them with access to exhaustive and comprehensive sources of information within the fields they are interested in. Descriptive statements were encountered indicating that, although they did not come to the department willingly, they chose to be university students by prioritizing the university’s features, including its inclusive structure that accommodates differences and offers opportunities for diversity and socialization. The descriptive statements in question represent the heterogeneous, lively, energetic, colorful, and dynamic dimensions of university life.

All these explanations demonstrate the crucial role universities play in creating a sustainable environment for future generations in socio-cultural terms. This result supports the studies of researchers such as [3,49,50].

Some of the students interviewed within the scope of the study stated that university life gave them confidence and peace, that they felt comfortable just like at home, that they tried to fill the void of being away from their families by building a family environment for themselves, and that the university experience was a continuation of the learning process at home. The United Nations University defines education for sustainable development as an impartial, fair, safe, and comprehensive educational process that provides access to human development [3]. Students often believe that university life offers them an experience that allows them to transition from a restricted life to a freer one, where ideas can be expressed more easily, where they can act without needing permission, and where their individual preferences are at the forefront.

It has been stated that a lonely and free life leads the individual to self-knowledge, and self-knowledge, in turn, leads the individual to freedom. Ensuring individual awareness should be a dimension supported by the idea of a sustainable university. This dimension will expand the definition of a sustainable university.

The students perceive university life as a structure that brings about gains, such as acquiring a profession, obtaining a diploma, reaching a certain status, gaining social prestige, earning money, building a career, and guiding all these pursuits. However, as we delve deeper into the descriptive expressions in this direction, they are future-oriented, viewing the university as a means of salvation and becoming a university student with the thought that it may be beneficial in the future. Descriptions stating that university is a necessity in order to achieve the stated gains were encountered. In addition, some students stated that university life liberated them because it offered them the opportunity to have a profession and gain economic independence. These expressions indicate that students view the university as a tool for addressing real-world problems. Therefore, this situation presents an opportunity that needs to be considered. It can be considered normal up to a certain point that the gains mentioned by the students are evaluated as a small output of university education and life. However, considering the reality of university as consisting only of this output in the eyes of university students will reduce the idea of a sustainable university. In this context, it is essential to convey to students what the concept of a sustainable university entails and how it should be implemented.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that students state that university life limits them and make some criticisms. From the descriptions, it is evident that the university is a structure that makes students feel like they are imprisoned, restricts their freedom of expression, pacifies them, requires a diploma, isolates individuals from their families, and has a high number of universities and departments. Even though some departments are unnecessary, universities are raising “modern slaves” by moving away from producing science, and the possibility of finding a profession is low if they do not study in a valid department. Therefore, resources such as money and time are wasted. It is essential to take these explanations seriously. For this, the question “why” should be asked to students who have these thoughts about the reality of universities. While this can be considered a limitation of this study, it also presents an opportunity for future research because the answers that can be obtained from the question “why” can expand the idea of a sustainable university.

When the data obtained within the scope of the study are evaluated holistically, it is seen that sustainable development principles should be integrated into university life and activities.

This study provides insights into university students’ perspectives on the university, making contributions that strengthen and expand the existing concept of a sustainable university. While the United Nations initially focused on “what” the concept of a sustainable university entails, it has shifted its emphasis to “how” the idea of a sustainable university should be implemented in recent years [51]. Therefore, addressing the concept of a sustainable university from the students’ perspective will shape how this understanding should be constructed.

Undoubtedly, this study has some limitations. Firstly, it is essential to note that the interpretation of data obtained through metaphor analysis involves the researchers’ subjective meaning-making efforts; therefore, generalizations should not be made. In any case, the qualitative research reflexive framework does not promise the generalizability of the research results [34]. Therefore, it is worth noting that the study can provide important insights into the university reality that university students construct with their cognitive patterns, independent of generalization. On the other hand, the fact that each country and university has its dynamics limits the generalizability of the results obtained in the study. However, the contributions of these insights, which strengthen and expand the idea of a sustainable university, should not be ignored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and G.Ş.; methodology, F.A. and Y.Ö.; software, B.Y.; validation, F.A., Y.Ö. and B.Y.; formal analysis, A.Y.; investigation, F.A., Y.Ö., B.Y. and G.Ş.; resources, A.Y.; data curation, F.A., A.Y. and B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A. and G.Ş.; writing—review and editing, F.A., G.Ş., F.S.Y. and Y.Ö.; visualization, A.Y.; supervision, F.A.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is an extended version of the research project supported by the TÜBİTAK 2209. A University Students Research Support Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Akdeniz University, Permission Code: E-78976156-903.07.01-500197, Permission Date: 15 November 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This is a qualitative study. All data collected are classified and presented in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moore, J. Policy, priorities and action: A case study of the university of British Columbia’s engagement with sustainability. High. Educ. Policy 2005, 18, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C.; Churchman, D. Sustaining Academic Life: A Case for Applying Principles of Social Sustainability to the Academic Profession. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.; Glavič, P. What are the Key Elements of a Sustainable University? Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2007, 9, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. The Nature of Design: Ecology, Culture and Human Intention; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, A.D. Education for an Environmentally Sustainable Future: A Priority for Environmental Protection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1992, 8, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasset, J.O.Y. Üniversitenin Misyonu (çev. Neyyire Gül Işık); Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık: İstanbul, Türkiye, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan, A.; Rosan, R.M. The Role of Universities Today: Critical Partners in Economic Development and Global Competitiveness; ICF Consulting: Reston, VG, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P. Küreselleşme ve Üniversite: 21. Yüzyılın Önündeki Meydan Okumalar. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilim. 2002, 2, 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez, L.; Munguia, N.; Platt, A.; Taddei, J. Sustainable University: What can be the Matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 14, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M. Modelling the Enablers of Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 17, 405–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G. Sustainability in Hospitality Education: A Content Analysis of the Curriculum of British Universities. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, Valletta, Malta, 11–12 June 2015; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Razman, R.; Abdullah, A.H.; Wahid, A.Z.A.; Muslim, R. Web content analysis on sustainable campus operation (SCO) initiatives. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 87, 01020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskis, R. Key Features of Sustainable Universities: A Literature Review. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 13, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, F. Örgüt Kültürünün Kök Metaforlarla Kesfi: Üniversite Gerçekliği Üzerine Nitel Bir Araştırma. Yönetim Araştırmaları Derg. 2010, 10, 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, R.M. New Directions in the Study of Culture. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K.; Newport, D.; White, J.; Townsend, A.R. Higher Education’s Sustainability Imperative: How to Practically Respond? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2012, 13, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapper, C.; Cropley, A.J. Lifelong Learning in Higher Education; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, Y.D.; Demirel, M. Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Yaşam Boyu Öğrenme Eğilimleri. Hacet. Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2012, 42, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Caldana, A.C.F.; Will, M.; Lange Salvia, A.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Platje, J.; Kovaleva, M. Sustainability Leadership in Higher Education Institutions: An Overview of Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing Key Competencies for Sustainable Development in Higher Education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumber, A. Transforming Sustainability Education Through Transdisciplinary Practice. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 7622–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Incorporation and Institutionalization of SD into Universities: Breaking Through Barriers to Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A.; Boström, G.O. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on sustainability in Higher Education: A Sustainability Competence Support Model. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1416498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 785163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaz, F. Metaphoric Images of the Strategic Management Concept: A Research on upper and Middle-Level Managers, Review of Contemporary Business. Entrep. Econ. Issues 2022, 35, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, F.; Satır, Ç. Features of Organizational Culture in Manufacturing Organizations: A Metaphorical Analysis. Work. Study 2003, 52, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inns, D. Metaphor in the Literature of Organizational Analysis: A Preliminary Taxonomy and A Glimpse at a Humanities-Based Perspective. Organization 2000, 9, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J.E.; Kendall, K.E. Metaphors and Methodologies: Living Beyond the System Machine. MIS Quarterly 1993, 17, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. Images of Organization; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sackmann, S. The Role of Metaphors in Organization Transformation. Hum. Relat. 1989, 42, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri (10. basım); Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, A.; Fırat, M. Açık ve Uzaktan Öğrenmede Metafor Analizi Araştırmaları. Açıköğretim Uygulamaları Ve Araştırmaları Derg. 2016, 2, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell, G.; Morgan, G. Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, England, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientist; Routledge Publications: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, S.; Richardson, J.; Manroop, L. Alternative Paradigms and the Study and Practice of Performance Management and Evaluation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri Beş Yaklaşıma Göre Nitel Araştırma Deseni (çev. M. Bütün ve S. B. Demir), (3. Baskı); Siyasal Kitabevi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koro-Ljungberg, M. Metaphors as a Way to Explore Qualitative Data. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2001, 14, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, A. The Internet as Research Context. In Qualitative Research Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 358–374. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. The Qualitative Research Interview. Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage Publication: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography Principles in Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, L.P.; Martins, N.; Gouveia, J.B. Quest for a Sustainable University: A Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weenen, H. Towards a Vision of a Sustainable University. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2000, 1, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaner, N. Yüksek Öğrenim Gençliğinin Psiko-Sosyal Sorunları. In Milli Kültür, Gençlik Özel Sayısı; KÜLTÜR VE TURİZM BAKANLIĞI: Ankara, Türkiye, 1986; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Çevik, A. Üniversite Gençliği ve Ruh Sağlığı: Psikopolitik Bir Değerlendirme. 2010. Available online: http://www.ppd.org.tr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=165:universitegencligiveruhsagligi&catid=2:prof4dr4abdulkadir4cevik&Itemid=3 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Djordjevic, A.; Cotton, D.R.E. Communicating the Sustainability Message in Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, F.A.; Shahbuddin, A.S.; Amran, A.; Rahman, S. Challenges of Sustainability Education: The Case of Private Universities in Bangladesh. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2010, 2, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.P.; Mani, V.; Yadav, M.; Joshi, Y. Authentic leadership towards sustainability in higher education—An integrated green model. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 901–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).